Abstract

Law enforcement officers (LEOs) must maintain a certain level of physical fitness to perform occupational tasks successfully. Because of the wide variation among operators, there does not appear to be a standard fitness test battery that is appropriate to assess occupational fitness for different groups of law enforcement officers. Therefore, multi-faceted fitness assessments are important to evaluate tactical personnel’s various essential fitness components, which are often unique to each environment. Fitness standards and training protocols must be developed for each law enforcement agency and customised to the specific audience. This article aims to systematically review the relevant literature to identify biomotor abilities associated with occupational physical ability. This study examined the results of 17 international studies to ultimately synthesise information that (i) aids in the selection of the most used biomotor abilities and occupational physical abilities for LEOs and (ii) serves as a starting point for the development of occupational physical abilities assessment protocols. In conclusion, this study underscores the complex and diverse physical demands on LEOs, advocating for tailored fitness programs and policy reforms to enhance their operational readiness and long-term health.

1. Introduction

Researchers have reported that most of the on-duty time of law enforcement officers (LEOs) is spent in sedentary activities that are integrated with the performance of brief, infrequent, high-intensity, essential job tasks [1]. The sedentary nature of law enforcement work is typically due to spending extended shift time seated in a patrol car while performing various tasks (e.g., using the mobile data terminal). Despite the sedentary nature of the occupation, a high level of physical fitness remains necessary to effectively perform essential occupational tasks (e.g., civil defence, first responder duties, and rescue situations). Therefore, developing occupationally relevant biomechanical abilities and enhancing technical and tactical skills [2,3] is important to optimise LEO readiness and safety.

The diverse nature of LEO work ranges from patrolling, which involves extended periods of vehicular mobility, to investigative duties requiring prolonged desk work to tactical units with physically demanding tasks. LEOs are required to perform a variety of movement patterns to accomplish job tasks. Specifically, these movement patterns include balancing, running, jumping, crawling, wrestling, dodging (i.e., agility), climbing stairs and fences, lifting objects, and pushing/pulling objects [1,4,5,6,7,8]. These tasks are typically performed without warning and while wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), which has been shown to adversely affect occupational physical performance [3,4,9,10]. PPE, such as body armour, helmets, and heavy equipment, is necessary for many LEO roles. Prolonged use of such equipment can cause heat stress, reduced mobility, and other physical stressors, emphasising the need for fitness programs that prepare officers for the rigours of prolonged PPE use.

Furthermore, as the physical demands of the job approach an individual’s maximum capacity, there is an increased risk of injury leading to disability and increased absenteeism [11,12]. Therefore, maintaining physical fitness to mitigate the health risks associated with their diverse roles’ sedentary and active aspects is imperative for LEOs, not only for operational effectiveness. These physically demanding occupational tasks require multiple biomotor skills. However, it is difficult to determine the most relevant biomotor skills from the literature due to differences in the task composition of physical ability assessments, variability in fitness tests, and the type of sample used (i.e., cadet vs. incumbent). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the relevant literature to identify relevant biomotor skills associated with officers’ occupational physical performance. Identifying relevant biomotor skills among the recruit and incumbent law enforcement populations will allow for the development of appropriate fitness assessments to screen law enforcement applicants, assess the readiness of the recruit and incumbent populations, and provide critical information regarding training goals so that appropriate periodisation training strategies can be implemented. Collectively, this information will guide programmatic strategies within law enforcement agencies to enhance officer readiness and safety. Our selection of databases was guided by their prevalence of high-quality, peer-reviewed articles pertinent to law enforcement, physical fitness, and occupational performance. The databases include PubMed, ScienceDirect, and the ISCPSI (Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security, Portugal) common repository. Each platform was chosen based on extensive coverage of physiological and occupational health literature, ensuring a comprehensive retrieval of relevant studies.

This systematic review is underpinned by a straightforward research question to identify the specific biomotor abilities most predictive of a successful occupational performance among law enforcement officers. It seeks to illuminate how the physical fitness components of LEOs, including those necessitated by the use of personal protective equipment, correlate with their ability to perform essential job tasks effectively. The overarching aim of this study is to synthesise existing literature to establish a comprehensive understanding of the physical fitness requirements for law enforcement officers. This endeavour aims to bridge existing knowledge gaps and provide a solid evidence base for developing targeted fitness assessment tools and training protocols. Such tools are intended to enhance officers’ operational readiness, safety, and long-term health outcomes by catering to the unique demands of their roles, whether in routine patrol settings or high-stakes tactical situations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Procedures

Key literature databases were systematically searched using specific keywords relevant to the topic to identify and obtain relevant original research for a literature review. The databases searched included PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Police+AND+Physical+tasks&sort=date (accessed on 6 February 2024), ScienceDirect (https://www.sciencedirect.com/search?qs=Police%20AND%20occupational%20physical%20ability&years=2016%2C2017%2C2018%2C2019%2C2020%2C2021&lastSelectedFacet=years (accessed on 6 February 2024), and the ISCPSI (Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security, Portugal) common repository (https://comum.rcaap.pt/handle/10400.26/6300 (accessed on 6 February 2024). These databases were selected based on the presence of a large number of high-quality peer-reviewed articles and the representation of journals relevant to the subject of the review. The final search terms and filters applied to the databases are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Databases and relevant search terms.

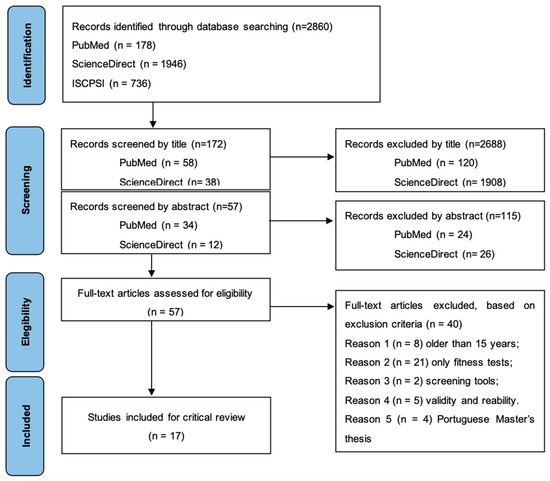

Filters reflecting study eligibility criteria were applied in each database, when available, to improve the relevance of the search results. Study eligibility criteria were applied manually by screening study titles and abstracts in the ISCPSI database where these filters were not available or only partially available. The eligibility criteria were used for the full text of identified articles included during title and abstract screening to select a final set of eligible articles for inclusion in this review. The searching, screening, and selecting of results were documented in a PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1) [13]. The inclusion criteria used were a law enforcement population, measures of physical fitness, and measures of occupational physical performance. Exclusion criteria were studies that were older than 15 years, studies that used only body composition as a measure of fitness, studies that involved the development of an instrument, studies that assessed only the effects of carrying a load, studies that used only screening instruments, and validity and reliability studies. Duplicates were removed after the collection of all studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram detailing the search procedures.

2.2. Critical Appraisal

The CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills and Programs, 2018) is a checklist of ten questions to assess the study’s methodological quality. The following responses are given for each question: “yes”, “can’t say”, or “no”. Questions 6 and 7 are short-answer questions, which were left blank due to the subjective nature of these questions [14]. Two authors assessed the methodological quality to avoid bias (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality assessment tools for studies are included in the critical review.

2.3. Data Extraction

Following a critical analysis of all articles, the following information was obtained: authors and year of publication; study population; measures (physical fitness testing); measures (occupational, physical skills); main findings; general findings. The results of the most internationally used biomotor skills are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Data extraction table including the studies that were included in the critical review.

3. Results

A total of 2420 studies were identified through the initial search of three databases. After the removal of duplicates and review by title and abstract, full-text versions of 57 studies were collated for review. These studies were then evaluated against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, after which 17 studies remained for critical review (Table 2). A summary of screening, selection processes, and literature search results can be found in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) [13].

All studies included LEOs. Twelve studies examined male and female participants [15,19,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], whereas the remaining five included only male participants [16,17,18,20,21]. Table 4 displays the frequency of significant biomotor ability correlates to occupational tasks among these studies. The frequency calculations are based on the percentage of studies demonstrating significant correlations, providing a quantitative overview of how biomotor abilities impact occupational tasks across diverse LEO populations. The following classifications were used to assess the strength of the correlations: trivial (r = 0–0.1), weak (r = 0.10–0.39), moderate (r = 0.40–0.69), strong (r = 0.70–0.89), and very strong (r = 0.90–1.0) [32].

Table 4.

Frequency of significant correlations between each biomotor ability and occupational tasks identified in the selected literature.

Fitness and Occupational Abilities Measures

Regarding the frequency of evaluation, muscular strength was assessed in 9 articles [16,17,18,19,22,23,28,29,31], muscular endurance was measured in 17 articles [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], and muscular power was measured in 13 articles [15,16,17,18,22,23,24,25,27,28,29,30,31]. Other fitness measurements included aerobic capacity, assessed in 7 articles [16,18,19,20,28,30,31] and anaerobic capacity in 4 articles [16,18,19,30]. Agility was assessed in 9 [15,16,18,19,22,28,29,30,31] articles, and the least commonly reported fitness measure was flexibility, which was assessed in 6 articles [15,16,19,22,29,31].

The most common biomotor abilities associated with occupational task performance included relative aerobic capacity, muscular strength, and agility (Table 3). Secondarily, muscular endurance, absolute aerobic capacity, and power were found to be related to occupational task performance. Those studies evaluated anaerobic capacity and flexibility less frequently and unrelated to occupational task performance.

There was considerable variability in the task composition and application of the occupational physical ability assessments. For instance, some studies utilised exercises that simulate occupational tasks like running and pushing objects to simulate foot chases and suspect engagement. Most studies included the victim rescue/body drag [19,22,23,26,29,31] and foot pursuit [19,22,24,25,31]. The 99-yard obstacle course [23,26,27], chain link fence [19,23,26,29,31], solid wall climb [21,22,23,27,28,29,31], and 500-yard run [23,26,27] were used less frequently. The application of the test battery also varied between studies, with most studies requiring completion of the occupational physical ability assessment on a separate day from fitness assessments. Ten of the studies completed occupational physical ability and fitness assessments on the same day [17,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,29,31], whereas the remaining seven studies completed each testing battery on different days [15,16,18,20,27,28,30]. In addition, some physical ability assessments required multiple occupational tasks to be completed continuously, whereas others allowed for recovery between tasks. This could be important for further studies as performing various tasks in succession (especially high-intensity, short-duration tasks) generally correlates with aerobic endurance.

To encapsulate the critical findings of our systematic review and to directly address the aim of identifying key biomotor abilities essential for law enforcement officers’ occupational performance, Table 5 below provides a concise summary of these abilities, along with their evaluation frequency, correlation strength, and relevance to specific occupational tasks.

Table 5.

Summary of biomotor abilities associated with occupational performance in law enforcement officers.

4. Discussion

This manuscript aimed to systematically review the literature to identify relevant biomotor abilities associated with the occupational physical ability of law enforcement officers (LEOs). The findings indicated that a multitude of biomotor abilities were found to be associated with occupational performance. This finding is intuitive given that no federal or internationally standardised fitness assessments or occupational physical ability tests exist for LEOs. As such, each study included in the review utilised a different fitness assessment battery and physical ability test. Indeed, it is understandable that different law enforcement agencies may use diverse occupational physical ability tests as the physical demands for a given LEO type (e.g., recruit, incumbent officer, SWAT officer, campus officer) and municipality (rural vs. urban) may vary. Despite this caveat, several themes emerged that provide useful information for practitioners, researchers, and law enforcement agencies. A description of these outcomes is provided below.

Although numerous biomotor abilities were found to have statistically significant correlations to occupational performance, the strengths of the correlations varied greatly. Lockie et al. [23] observed a significant but weak correlation between the PT500 and performance in select occupational tasks, with the strongest correlation found between the 2.4 km run and the 500-yard run (r = −0.57). Similarly, Locke et al. [27] experienced similar weak to moderate correlations between most fitness evaluations and occupational tasks (r = 0.11–0.35) except moderate to strong correlations between MSFT, the 201 m run, 2.4 km run, and 500-yard run. Becket al. found that agility, aerobic endurance, and muscular endurance were associated with the occupational demands of campus police [16]. The authors in each study concluded that muscular and aerobic endurance are critical biomotor abilities related to law enforcement occupational tasks.

Regarding the importance of anaerobic biomotor abilities in occupational performance, Teixeira et al. [17] found moderate to strong correlations between several fitness tests, particularly strength and power assessments and Portuguese on-duty task evaluation completion times [17]. Overall, the correlations found within these studies support using a broad range of physical fitness assessments to evaluate occupational performance while highlighting the diversity in the physical demands of LEOs. This is logical considering the essential job tasks of LEOs include foot pursuit with potential obstacles, suspect altercation, defensive tactics, and victim rescue scenarios [16,17,19,22,23,27,28,29,31].

The relationship of these biomotor abilities with PPE demands is crucial for optimising the performance and safety of LEOs in the field. Agility refers to the ability to change direction quickly. This characteristic is critical when chasing a suspect, taking cover when taking gunfire, or closing a distance quickly to neutralise a threat. Research indicates that the ability to accelerate is important, especially under the load carriage conditions imposed by tactical gear [10,19,30].

It is also important to note that biomotor abilities are likely not mutually exclusive and, thus, not independent. For instance, cardiorespiratory fitness is closely linked to muscular endurance, as the muscles require oxygen to perform work over a prolonged period [32]. Indeed, muscular endurance and aerobic capacity have typically been correlated with similar running tasks, such as the 99-yard obstacle course and the 500-yard run [23,27]. Likewise, upper-body strength, such as pulling or abdominal strength, may influence climbing tasks, such as a solid wall and chain-link fence [19,21,22,23,27,28,29,31]. Agility, sit-up, upper-body strength, and aerobic capacity were collectively related to overall occupational physical performance tasks [16,19,27,28,29,30,31].

Strength measures have also been associated with task performance and injury risk, and studies suggest that using personal protective equipment decreases LEOs’ physical performance on cardiorespiratory fitness tests, strength, power, and speed during changes in direction [18,29,30]. Tests of these physical abilities should be included in conditioning batteries to determine the relationships between physical fitness and occupational performance when using personal protective equipment [18,20,30,32].

Law enforcement agencies should ensure that their recruits have the muscular endurance, anaerobic capacity, and aerobic capacity necessary to complete the work trial test battery [19,23,30].

Fewer studies examined the relationship between flexibility and anaerobic capacity versus occupational physical performance. Despite the lack of evaluation of these biomotor abilities, they may still be relevant to optimising LEO performance and health. For instance, flexibility, unless significantly limited, likely does not impact performance. However, lack of flexibility in some joints may increase lower back pain incidence [33]. This can be especially problematic for officers spending extensive time seated in a patrol car while wearing a duty belt. Indeed, muscular tightness associated with the lower cross syndrome (i.e., tightness of hip flexors and hamstring muscles) may increase lower back pain and symptomology [33]. Although anaerobic capacity was not related to occupational performance, Thomas et al. [9] reported that anaerobic fatigue tolerance was associated with decreased occupational task efficiency due to load carriage in special weapons and tactics officers (SWAT).

Also, age and function are important in differentiating older recruits’ assessments, time commitments outside the academy, or differences in fitness levels compared with younger recruits that could influence outcomes and recovery. As individuals age, they tend to lose muscle mass, strength, and cardiovascular fitness [24]. This can make it more difficult for older LEOs to perform tasks that require a high level of physical fitness. Differences in fitness levels compared to their younger counterparts could also affect recovery. Maintaining a moderate to high running intensity, characterised by a specific pace or VO2max levels indicative of aerobic capacity and good aerobic fitness, significantly enhanced the likelihood of successful completion [24]. Age was significantly positively correlated with the overall duration of physical skills and tasks on the job [16,29,33].

Significant phase-specific changes in overall physical performance were observed during the individualised training course, including decreases in body fat percentage, anaerobic capacity, and maximal oxygen uptake. Current performance training during the course improves critical strength and power aspects [34].

Fitness standards and training protocols need to be developed for each law enforcement agency and adapted to each target population. Differences in fitness testing procedures have also been noted, highlighting the need to standardise fitness testing procedures to ensure consistency and enhance the ability to compare results. Developing occupational and health-related fitness standards and associated health and conditioning strategies will help to improve the health and fitness of officers. Health status has an impact on biomotor abilities. Officers who have chronic health conditions such as obesity or diabetes may find it more difficult to perform tasks that require a high level of physical fitness [35].

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study conducted a rigorous analysis of the physical demands and fitness requirements of LEOs across various roles. By synthesising data from 17 worldwide studies, we identified critical areas for improvement in current fitness programs and policy guidelines. Our findings highlight the necessity of tailored fitness strategies to address the unique challenges officers face, ranging from the sedentary aspects of surveillance and administrative duties to the physically demanding nature of tactical operations. The study underscores the importance of maintaining operational readiness and promoting long-term health and well-being among law enforcement personnel. The practical implications of our research advocate for policy reforms and the implementation of diversified training regimens that are scientifically grounded and role-specific. Future research should continue to explore the evolving physical demands of law enforcement work and the most effective training methodologies to meet these challenges. Ultimately, this study contributes to the ongoing dialogue on enhancing the safety, effectiveness, and health of those who serve in law enforcement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and resources, L.M., V.S. and L.M.M.; methodology, formal analysis, investigation, and writing (original draft preparation), L.M., V.S. and L.M.M.; writing (review and editing), L.M., V.S., M.G.A., E.L.L., G.J.M. and L.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Portuguese National Funding Agency for Science, Research and Technology—FCT, grant number UIDP/04915/2020 and UIDB/04915/2020 (ICPOL Research Center—Higher Institute of Police Sciences and Internal Security (ISCPSI)—R&D Unit).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anderson, G.S.; Plecas, D.; Segger, T. Police officer physical ability testing—Re-validating a selection criterion. Policing Int. J. 2001, 24, 8–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scofield, D.E.; Kardouni, J.R. The Tactical Athlete. Strength Cond. J. 2015, 37, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomes, C.; Orr, R.M.; Pope, R. The impact of body armor on physical performance of law enforcement personnel: A systematic review. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 29, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, Z.G.; Plecas, A. Police officer back health. J. Crim. Justice Res. 2011, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Birzer, M.L.; Craig, D.E. Gender differences in police physical ability test performance. Am. J. Police 1996, 15, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissett, D.; Bissett, J.; Snell, C. Physical agility tests and fitness standards: Perceptions of law enforcement officers. Police Pr. Res. 2012, 13, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, C.D.; Callaghan, J.P.; Dickerson, C.R. Field Quantification of Physical Exposures of Police Officers in Vehicle Operation. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2011, 17, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Violanti, J.M.; Fekedulegn, D.; Andrew, M.E.; Charles, L.E.; Hartley, T.A.; Vila, B.; Burchfiel, C.M. Shift work and the incidence of injury among police officers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2012, 55, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Pohl, M.B.; Shapiro, R.; Keeler, J.; Abel, M.G. Effect of Load Carriage on Tactical Performance in Special Weapons and Tactics Operators. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinski, W.J.; Dysterheft, J.L.; Dicks, N.D.; Pettitt, R.W. The influence of officer equipment and protection on short sprinting performance. Appl. Ergon. 2015, 47, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydren, J.R.; Borges, A.S.; Sharp, M.A. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Predictors of Military Task Performance: Maximal Lift Capacity. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1142–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, T.C.; Knapik, J.J.; Ritland, B.M.; Murphy, N.; Sharp, M.A. Risk factors for musculoskeletal injuries for soldiers deployed to Afghanistan. Aviat. Space, Environ. Med. 2012, 83, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critical Appraisal Skills and Programme. CASP Systematic Review Checklist. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Systematic-Review-Checklist-2018_fillable-form.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Adams, J.; Cheng, D.; Lee, J.; Shock, T.; Kennedy, K.; Pate, S. Use of the Bootstrap Method to Develop a Physical Fitness Test for Public Safety Officers Who Serve as Both Police Officers and Firefighters. Bayl. Univ. Med Cent. Proc. 2014, 27, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.Q.; Clasey, J.L.; Yates, J.W.; Koebke, N.C.; Palmer, T.G.; Abel, M.G. Relationship of Physical Fitness Measures vs. Occupational Physical Ability in Campus Law Enforcement Officers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2340–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, J.; Monteiro, L.F.; Silvestre, R.; Beckert, J.; Massuça, L.M. Age-related influence on physical fitness and individual on-duty task performance of Portuguese male non-elite police officers. Biol. Sport 2019, 36, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frio Marins, E.; Cabistany, L.; Bartel, C.; Dawes, J.J.; Boscolo Del Vecchio, F. Aerobic fitness, upper-body strength and agility predict performance on an occupational physical ability test among police officers while wearing personal protective equipment. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2019, 59, 1835–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canetti, E.F.D.; Dawes, J.J.; Drysdale, P.H.; Lockie, R.; Kornhauser, C.; Holmes, R.; Schram, B.; Orr, R.M. Relationship Between Metabolic Fitness and Performance in Police Occupational Tasks. J. Sci. Sport Exerc. 2020, 3, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Weyden, M.S.; Black, C.D.; Larson, D.; Rollberg, B.; Campbell, J.A. Development of a Fitness Test Battery for Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) Operators—A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Micovic, M.; Schram, B.; Leroux, A.; Orr, R. Physiological demands of active shooter response in specialist police: A case study. Tactical Perform. Decis. Mak. 2023, 1, 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dicks, N.D.; Shoemaker, M.E.; DeShaw, K.J.; Carper, M.J.; Hackney, K.J.; Barry, A.M. Contributions from incumbent police officer’s physical activity and body composition to occupational assessment performance. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1217187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockie, R.G.; Dawes, J.J.; Balfany, K.; Gonzales, C.E.; Beitzel, M.M.; Dulla, J.M.; Orr, R.M. Physical Fitness Characteristics That Relate to Work Sample Test Battery Performance in Law Enforcement Recruits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockie, R.G.; Balfany, K.; Bloodgood, A.M.; Moreno, M.R.; Cesario, K.A.; Dulla, J.M.; Dawes, J.J.; Orr, R.M. The Influence of Physical Fitness on Reasons for Academy Separation in Law Enforcement Recruits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockie, R.G.; Dawes, J.J.; Moreno, M.R.; McGuire, M.B.; Ruvalcaba, T.J.; Bloodgood, A.M.; Dulla, J.M.; Orr, R.M. We Need You: Influence of Hiring Demand and Modified Applicant Testing on the Physical Fitness of Law Enforcement Recruits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockie, R.G.; Pope, R.P.; Saaroni, O.; Dulla, J.M.; Dawes, J.J.; Orr, R.M. Job-Specific Physical Fitness Changes Measured by the Work Sample Test Battery within Deputy Sheriffs between Training Academy and their First Patrol Assignment. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2020, 13, 1262–1274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lockie, R.G.; Moreno, M.R.; Rodas, K.A.; Dulla, J.M.; Orr, R.M.; Dawes, J.J. With great power comes great ability: Extending research on fitness characteristics that influence work sample test battery performance in law enforcement recruits. Work 2021, 68, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, G.J.; Ma, X.; Best, S.; Johnson, B.F.; Abel, M.G. Implementation of High Intensity Interval Training and Autoregulatory Progressive Resistance Exercise in a Law Enforcement Training Academy. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2022, 15, 1246–1261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dawes, J.J.; Scott, J.; Canetti, E.F.D.; Lockie, R.G.; Schram, B.; Orr, R.M. Profiling the New Zealand Police Trainee Physical Competency Test. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 821451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukić, F.; Janković, R.; Dawes, J.J.; Orr, R.; Koropanovski, N. Effects of Occupational Load on the Acceleration, Change of Direction Speed, and Anaerobic Power of Police Officers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 37, 1237–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockie, R.; Dawes, J.J.; Sakura, T.; Schram, B.; Orr, R.M. Relationships Between Physical Fitness Assessment Measures and a Workplace Task-Specific Physical Assessment Among Police Officers: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2023, 37, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, C. The impact of age, physical activity and physical fitness on shooting performance. In Ciências Policiais; Instituto Superior de Ciências Policiais e Segurança Interna: Lisbon, Portugal, 2016; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- Winters, J.D.; Heebner, N.R.; Johnson, A.K.; Poploski, K.M.; Royer, S.D.; Nagai, T.; Randall, C.A.; Abt, J.P.; Lephart, S.M. Altered Physical Performance Following Advanced Special Operations Tactical Training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 1809–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, C.J.; Orr, R.M.; Goad, K.S.; Schram, B.L.; Lockie, R.; Kornhauser, C.; Holmes, R.; Dawes, J.J. Comparing levels of fitness of police Officers between two United States law enforcement agencies. Work 2019, 63, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).