Abstract

Recently, AI software has been rapidly growing and is widely used in various industrial domains, such as finance, medicine, robotics, and autonomous driving. Unlike traditional software, in which developers need to define and implement specific functions and rules according to requirements, AI software learns these requirements by collecting and training relevant data. For this reason, if unintended biases exist in the training data, AI software can create fairness and safety issues. To address this challenge, we propose a maturity model for ensuring trustworthy and reliable AI software, known as AI-MM, by considering common AI processes and fairness-specific processes within a traditional maturity model, SPICE (ISO/IEC 15504). To verify the effectiveness of AI-MM, we applied this model to 13 real-world AI projects and provide a statistical assessment on them. The results show that AI-MM not only effectively measures the maturity levels of AI projects but also provides practical guidelines for enhancing maturity levels.

1. Introduction

Along with big data and the Internet-of-Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI) has become a key technology of the fourth industrial revolution and is widely used in various industry areas, including finance, medical/healthcare, robotics, autonomous driving, smart factories, shopping, delivery, and so on. AI100, an ongoing study conducted by a group of AI experts in various fields, focuses on the influence of AI. It has been predicted that AI will totally change human life by 2030 [1]. In addition, according to a report by McKinsey, about 50% of companies use AI in their products or services, and 22% of companies increased their profits by using AI in 2020 [2]. Furthermore, IDC, a U.S. market research and consulting company, predicts that the global AI market will grow rapidly by 17% annually from $327 billion in 2021 to $554 billion in 2024 [3].

Unlike traditional software that operates according to rules defined and implemented by humans, the operation of AI software is determined by data used for training. In other words, AI software can make different decisions in the same situation when the data is changed, even though the core architecture of the AI software is the same. Due to the fact that AI software relies on training data, various problems that developers did not expect are occurring. For example, unintended bias in the training data can exacerbate existing ethical issues, such as gender, race, age, and/or regional discrimination. Insufficient training data can cause safety problems, such as autonomous driving accidents. Additionally, the Harvard Business Review warned that these kinds of problems could devalue companies’ brands [4]. The following provides some examples of actual AI-software-related problems that have drawn global attention.

- Tay, a chatbot developed by Microsoft, was trained using abusive language by far-right users. As a result, Tay generated messages filled with racial and gender discrimination; it was shut down after only 16 h [5].

- Amazon developed an AI-based resume evaluation system, but it was stopped due to a bias problem that excluded resumes including the word “women’s”. This issue occurred because the AI software was trained using recruitment data collected over the past 10 years where most of the applicants were men [6].

- The AI software in Apple cards suggested lower credit limits for women as compared to their husbands, even though they share all assets, because it was trained by male-oriented data [7].

- Google’s image recognition algorithm misrecognized a thermometer as a gun when a white hand holding a thermometer was changed to a black hand [8].

- Tesla’s auto pilot could not distinguish between a bright sky and a white truck, causing driving accidents [9].

To address social issues exacerbated by AI software, several governments, companies, and international organizations have begun to publicly share principles for developing and using trustworthy AI software over the past few years. For example, Google proposed seven principles for AI ethics, including preventing unfair bias [10]. Microsoft also proposed six principles of responsible AI, including fairness and reliability [11]. Recently, Gartner reported the top 10 strategic technology trends for 2023, and one of the trends is AI Trust, Risk, and Security Management (AI TRISM) [12].

In addition, the need for international standards about trustworthy AI is being discussed. Specifically, the EU announced an AI regulation proposal for trustworthy AI [13]. The EU also classified AI risk into different categories, including unacceptable risk, high risk, and low or minimal risk, and argued that risk management is required in proportion to the risk level [14].

In this paper, we propose the AI Maturity Model (AI-MM), a maturity model for trustworthy AI software to prevent AI-related social issues. AI-MM is defined by analyzing the latest related research of global IT companies and conducting surveys and interviews with 70 AI experts, including development team executives, technology leaders, and quality leaders in various AI domain fields, such as language, voice, vision, and recommendation. AI-MM covers common AI processes and quality-specific processes in order to extensively accommodate new quality-specific processes, such as fairness. To evaluate the effectiveness and applicability of the proposed AI-MM, we provide statistical analyses of assessment results by applying AI-MM to 13 real-world AI projects with a detailed case study. In summary, the contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We propose a new maturity model for trustworthy AI software, i.e., AI-MM. It consists of common AI processes and quality-specific processes that can be extended to other quality attributes (e.g., fairness and safety).

- To show the effectiveness and applicability of our AI-MM, we apply AI-MM to 13 real-world AI projects and show a detailed case study with fairness assessments.

- Based on the 13 assessment results, we provide statistical analyses of correlations among AI-MM’s elements (e.g., processes and base practices) and among characteristics of assessments and projects, such as different assessors (including self-assessments by developers and external assessors), development periods, and number of developers.

2. Related Works

To address issues of AI software, we first specify the differences between traditional software development and AI software development (Section 2.1). Then, we introduce some research related to trustworthy AI (Section 2.2) and also overview existing traditional software maturity models and maturity model development methodologies (Section 2.3). Finally, we introduce several research works covering AI process assessment (Section 2.4).

2.1. Characteristics of AI Software Development

The goal of software is to develop functions satisfying requirements determined by stakeholders [15]. In the case of traditional software, developers directly analyze the requirements, define behaviors for both normal and abnormal cases, and implement algorithms to achieve the requirements. On the other hand, in the case of AI software, developers prepare large amounts of data based on requirements and design the AI model architecture. The algorithms are then automatically formulated through the process of training with large amounts of collected data. Thus, AI software can work differently when training data are different, even though the model architecture is the same. Due to these characteristics, data are the most critical part of implementing AI software, and the quality of algorithms in AI software depends on the amount and quality of data. Zhang et al. [16] explain that, unlike traditional software tests, AI software tests have different aspects, including test components (e.g., data and learning programs), test properties (e.g., fairness), and test workflows. They also argue that research about qualities considering AI characteristics, such as fairness and safety, is relatively insufficient.

2.2. Trustworthy AI

To prevent AI issues, such as ethical discrimination (e.g., discrimination based on gender, race, and/or age) and safety problems (e.g., autonomous driving accidents), a quality assurance process related to several aspects, such as fairness and safety, is required. Research coming out of the EU [13,17] presents several dimensions of trustworthy AI software, including Safety & Robustness, Non-discrimination & Fairness, Transparency (Explainability, Traceability), Privacy, and Accountability.

Specifically, bias (unfairness) refers to a property that is not neutral towards a certain stimulus. There are various types of biases, such as cognitive bias and statistical bias. The types of bias can also be classified depending on the characteristics of the data. Mehrabi et al. [18] classify 23 types of bias, including “historical bias” caused by the influence of historical data and “representative bias” resulting from how we sample from a population during data collection. They also introduce 10 widely used definitions of fairness, including “equalized odds” and “equal opportunity,” to try and prevent various biases. In addition, they explain bias-reduction techniques in specific AI domains, such as translation, classification, and prediction. For example, a bias in translation can be alleviated by learning additional sentences that exchange words for men and women to solve gender-specific bias that translates programmers into men and housemakers into women. In addition, Zhuo et al. [19] benchmark ChatGPT using several datasets such as BBQ and BOLD to find AI ethical risks.

On the topic of enhancing transparency in AI software development, there have been a few research works. For example, Mitchell et al. [20] propose an “AI model card” for describing detailed characteristics (e.g., purpose, model architecture, training and evaluation dataset, evaluation metric) of AI models, and Mora-Cantallops et al. [21] review existing tools, practices, and data models for traceability of code, data, AI models, people, and environment.

Liang et al. [22] explain the importance of data for trustworthy AI. Specifically, they introduce some critical questions about data collection, data preprocessing, and evaluation data that developers should consider. However, these techniques are still in the early stages of research, and there is a lack of research to test and prevent fairness issues, especially at organizational process maturity levels. Our work focuses on AI software development processes in the form of a maturity model to develop trustworthy AI software, rather than developing testing and evaluation methods of AI products.

2.3. Traditional Software Maturity Models

SPICE (ISO/IEC 15504) and CMMI are representative maturity models for evaluating and improving the development capabilities of traditional software [23]. To propose a maturity model for AI software, we analyze those maturity models.

2.3.1. SPICE (ISO/IEC 15504)

SPICE is an international standard for measuring and improving traditional software development processes, and it consists of “Process” and “Capability” dimensions. A process is composed of interacting activities that convert inputs into outputs, and the process dimension consists of a set of processes necessary to achieve the goal of software development. The capability of a process refers to the ability to perform the process, and the capability dimension measures the level of capability.

Specifically, the process dimension of SPICE consists of 48 processes. These are classified into three lifecycles (primary, support, and organization) and nine process areas (acquisition, supply, operation, engineering, support, management, process improvement, resource and infrastructure, and reuse) [24]. In addition, the capability dimension consists of six levels (incomplete, performed, managed, established, predictable, and optimizing), which assess the performance ability of each process. The level of each process is determined by measuring process attributes for each level. The process attributes indicate specific characteristics of a process for evaluating levels and can be commonly applied to all processes.

SPICE can be extended to other domains. For example, the Automotive Special Interest Group (AUTOSIG), a European automaker organization, developed Automotive-SPICE (A-SPICE) based on SPICE to assess suppliers via a standardized approach [24]. Major European carmakers demand the application of A-SPICE to assess the software development processes of suppliers.

2.3.2. Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI)

CMMI is a maturity model developed by the Software Engineering Institute (SEI) to assess the work capabilities and organization maturity of software development. It is an extended version of SW-CMM that incorporates system engineering-CMM, and it is widely used in various domains, such as IT, finance, military, and aviation [25].

Specifically, CMMI provides 22 process areas, including project planning and requirements engineering. CMMI also provides five maturity levels (initial, managed, defined, quantitatively managed, and optimizing) for evaluating organization maturity and six capability levels (incomplete, performed, managed, defined, quantitatively managed, and optimizing) for evaluating the work capability of each process [26].

2.3.3. Maturity Model Development Methodology

Becker et al. [27] point out that new IT maturity models have been proposed to cope with rapid requirement changes in IT domains, but there are many cases where no significant difference from existing maturity models is specified (or only insufficient information is provided). To address these problems and develop a maturity model systematically, they propose a development procedure that must be followed. They analyze several maturity models, such as CMMI, and extract the common requirements necessary to develop a new maturity model. They also define detailed procedures for developing maturity models, including problem definition, determination of development strategy, iterative maturity model development, and evaluation. They also emphasize that analyzing existing research and collecting expert opinions should be iteratively processed.

2.4. Assessment of AI Software Development Processes

Recently, research assessing AI development processes has been actively conducted [28,29,30]. To evaluate the ability to develop trustworthy AI software, Google [28] distinguishes four AI test areas (data, model, ML infrastructure, and monitoring) and derives 28 test items (each test area has seven test items). Based on the derived test items, Google defines the method of calculating the “ML Test Score” as follows:

- Test item score: 0 for non-execution, 0.5 for manual execution, 1 for automation

- Test area score: Sum of test item scores (maximum of 7 points)

- Total score: Minimum score among four test area scores

While the test items in “ML Test Score” can be used as inputs for checklists and quantitative indicators to determine the level of trustworthy AI software, those rarely provide specific improvement guides.

Amershi et al. [29] introduce nine steps of AI software development processes at Microsoft and show survey results collected from AI developers and managers, which indicate that the data management system is important for AI software development.

IBM [30] also proposes an AI maturity framework with process and capability dimensions. The process dimension includes learning, verification, deployment, fairness, and transparency, and the capability dimension has five different levels: initial, repeatable, defined, managed, and optimizing. While this framework specifies AI development processes and best practices based on IBM’s experiences with AI project development, it does not include detailed procedures related to trustworthy issues.

3. A Maturity Model for Trustworthy AI Software

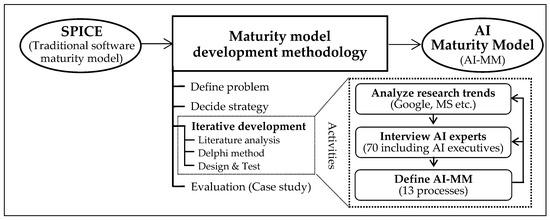

In this section, we propose a new maturity model for trustworthy AI software. As illustrated in Figure 1, we first define AI-MM for AI development processes based on Becker’s model [27]. We then provide the guidelines for AI-MM processes.

Figure 1.

Development process of AI-MM (Becker et al. [27]).

3.1. Selection of Base Maturity Model

As a base maturity model, we selected SPICE since it is an international standard for software maturity assessment and has been successfully extended into A-SPICE, which is widely used in the automotive industry.

3.2. Process Dimension Design

We designed the architecture of AI-MM to be extensible for various quality areas, such as fairness and safety. As shown in Figure 1, we also perform the following activities iteratively to define processes of AI-MM: (1) analyze recent research trends, (2) survey and interview AI domain experts, (3) define and revise AI-MM.

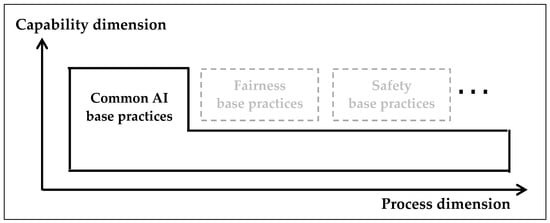

3.2.1. Extensible Architecture Design of AI-MM

As shown in Figure 2, AI-MM covers common AI processes and quality-specific processes separately, and users can select the specific set of processes that suit the development purposes and characteristics of their AI projects. For example, an AI chatbot project must be sensitive to dealing with fair words, while stability may be less important. In that case, an intensive evaluation of fairness can be conducted by selecting fairness-specific processes in our proposed AI-MM.

Figure 2.

Architecture design of extensible AI-MM.

3.2.2. Common AI Process Areas and Processes

We separately defined common, fairness-specific, and safety-specific processes for the extensibility of AI-MM. Based on analyzing related research shared by Google, Microsoft, and IBM [28,29,30], we defined an initial version of AI-MM consisting of 38 base practices, which are activities or checklists to decide capability levels. We then surveyed 70 AI experts consisting of eight executives, 23 technology leaders, 29 developers, and 10 quality leaders by using the initial AI-MM. To clarify ambiguous answers, we performed additional interviews. These survey results are reflected in our AI-MM revisions. Table 1 shows the representative opinions of the AI experts.

Table 1.

Representative opinions collected and reflected through a survey.

Based on the survey results, we define four process areas: (1) Plan and design, (2) Data collection and processing, (3) Model development & evaluation, and (4) Operation and monitoring. Table 2 shows the definition of 10 processes for the process areas. After that, we extract and revise 24 common base practices from the 38 base practices.

Table 2.

Processes in common process areas.

3.2.3. AI Fairness Processes

Similar to the common base practices, we also extracted 13 fairness base practices from the 38 base practices based on the survey and interviews with AI experts [31]. The final 13 fairness base practices in four process areas are shown as follows:

- Plan and design (4): Fairness risk factor analysis, Fairness evaluation metric, Stakeholder review—fairness, Design considering fairness maintenance.

- Data collection and processing (4): Data bias assessment, Data bias periodic check, Data bias and sensitive information preprocessing, Data distribution verification.

- Model development and evaluation (3): Bias review during model learning, Fairness maintenance check, Model’s fairness evaluation result record.

- Operation and monitoring (2): Fairness management infrastructure, Monitoring model quality.

3.2.4. AI Safety Processes

To show the extensibility of AI-MM, we also define safety-specific processes. For safety processes and safety base practices, we analyze international standards, such as ISO/IEC 24,028 (the AI safety framework part) [32], adding one process area and three processes as follows:

- Process Area: “System evaluation” for assessing the system that AI software runs on.

- Process: Two processes (System safety evaluation and System safety preparedness) are added in the “System evaluation” process area and one process (Safety evaluation of AI model) is added in the “Model development and evaluation” process area.

We also define 16 safety base practices for the processes. Example processes and practices are shown as follows:

- Safety evaluation of AI model process (3): Safety check of the model source code, Model safety check from external attacks, Provide model reliability.

- System safety evaluation process (2): Safety evaluation according to system configuration, System safety evaluation from external attacks.

- System safety preparedness process (3): User error notice in advance, Provide exception handling policy, Consider human intervention.

3.2.5. Integration of the AI Processes

Based on the work explained in Section 3.2.2, Section 3.2.3, Section 3.2.4, AI-MM is structured with five process areas, 13 processes, and 53 base practices for common, fairness, and safety maturity assessments, as summarized in Table 3. We omit detailed descriptions for base practices.

Table 3.

Process dimensions of AI-MM.

3.3. Capability Dimension Design

Regarding capability dimension, we use the existing definition from SPICE and A-SPICE—consisting of six levels, as described in Section 2.3.1—to be consistent in terms of the framework extension with other AI software quality attributes, such as explainability, privacy, fairness, and safety.

In SPICE, the capability of each process is determined by the process attribute (PA) for each level. There are nine PAs, including one PA corresponding to capability level 1 (PA 1.1) and eight other PAs where there are two for each level from level 2 to level 5 (PA 2.1 to PA 5.2). PA 1.1 and the other PAs have different evaluation methods [33].

For evaluating level 1 of a process, the base practices are used. Thus, to determine whether the process satisfies level 1, we check whether the base practices in the process have been performed or not; this is done by analyzing the related outputs. This process achieves level 1 when it gets “largely achieved” or “fully achieved”.

- N (Not achieved): There is little evidence of achieving the process (0–15%).

- P (Partially achieved): There is a good systematic approach to the process and evidence of achievement, but achieving in some respects can be unpredictable (15–50%).

- L (Largely achieved): There is a good systematic approach to the process and clear evidence of achievement (50–85%).

- F (Fully achieved): There is a complete and systematic approach to the process and complete evidence of achievement (85–100%).

3.4. AI Development Guidelines

For developers to quickly and effectively improve their capability for trustworthy AI development, we also provide AI development guidelines with practical best practices. Specifically, we provide 13 guidelines for the “Data collection and processing” process area, 11 guidelines for the “Model development and evaluation” process area, and 17 guidelines for the “Operation and monitoring” process area. The guidelines consist of a title, a description, and examples. Table 4 shows some of these guidelines.

Table 4.

Example AI development guidelines.

4. Case Study

To evaluate the effectiveness of AI-MM, we apply AI-MM to 13 different AI projects which might be vulnerable to social issues (e.g., gender discrimination) or safety accidents. Table 5 describes these AI projects.

Table 5.

Abstracted descriptions of 13 AI projects.

The assessment results of applying AI-MM to 13 AI projects are shown in Table 6. Pr6 has the highest maturity level (3.0), while Pr13 has the lowest maturity level (0.6). Here, the maturity level of a project is the average of the capability levels of 13 processes.

Table 6.

Assessment results (capability levels) of applying AI-MM to 13 AI projects.

In order to find how AI-MM can be used effectively and efficiently, we analyze the 13 assessment results statistically for various aspects, such as different assessors (e.g., self-assessments by developers and external assessors), development periods, and a number of developers, as well as correlations among AI-MM’s elements (e.g., processes and base practices) in Section 4.1.

In Section 4.2, we provide a detailed case study of AI-MM adoption for real-world AI projects and demonstrate its practicality and effectiveness through capability evaluation. We also provide practical guidelines for AI fairness.

4.1. Analysis of Assessment Results

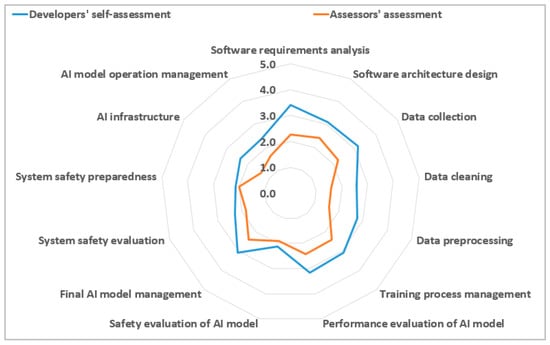

4.1.1. Developers’ Self-Assessments vs. External Assessors’ Assessments

We compare the self-assessment results with those made by external assessors (Table 7). We asked developers to self-assess the capability levels of AI development processes while we, as external assessors, assessed the project at the same time.

Table 7.

Developers’ self-assessments vs. assessors’ assessments.

To measure the correlation between the assessment results of the two groups, Pearson correlation analysis [34] is used. This approach can find the relationship between two continuous variables, such as development periods (years) and income. The measured value is R = 0.713, indicating a high correlation. As shown in Figure 3, the assessment results of each process by the two groups are very similar, implying that developers reasonably assessed whether AI development processes for their projects were fully or insufficiently performed, similarly to third-party assessors. However, developers tend to award higher capability levels than the assessors during their assessment. Thus, it is possible to consider a new method of approximately inferring AI maturity by calibrating a developer’s self-assessment results with an appropriate compensation formula to assess projects quickly and with lower costs.

Figure 3.

Developers’ self-assessments vs. assessors’ assessments.

4.1.2. Correlation of Project Characteristics and Maturity Levels

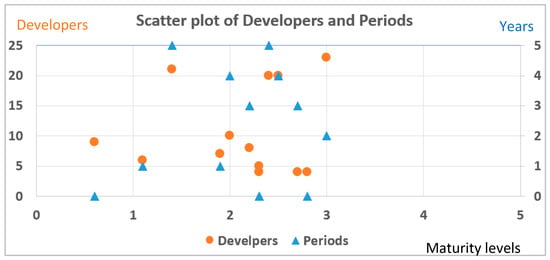

The relation between the overall maturity levels and project development periods is measured by Pearson correlation analysis. The relation between the overall maturity levels and the number of developers is also measured. Both measured coefficient values are under 0.2 (R = 0.107 for periods, 0.125 for developers), indicating that the development periods and the number of developers are not much related to the maturity levels (Table 8, Figure 4).

Table 8.

Maturity levels, development periods, and number of developers of 13 AI projects.

Figure 4.

Maturity levels, development periods, and number of developers of 13 AI projects (Graph). Pearson coefficient R = 0.125 (Developers), R = 0.107 (Periods).

We also check the correlations of the development periods and the number of developers with the maturity levels with respect to each process. As shown in Table 9, all processes have a Pearson coefficient of 0.444 or less, which means there is no special correlation.

Table 9.

Correlation of development periods and the number of developers w. r. t. each process.

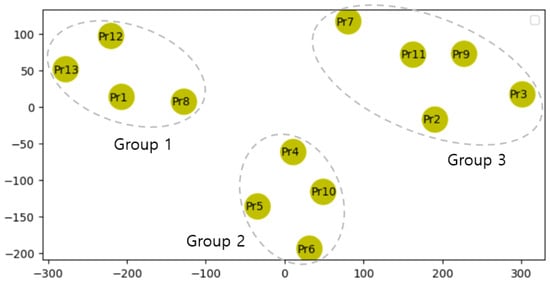

To evaluate the correlation among 13 AI projects, t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) [35] is used. This compresses and visualizes the assessment results of 13 processes on the projects into two dimensions, as shown in Figure 5. The 13 AI projects can be divided into three groups:

Figure 5.

Correlations among AI projects (t-SNE with perplexity 5.0).

- Group 1 (Pr1, Pr8, Pr12, Pr13): These projects are research (pilot) projects for system modules rather than entire systems.

- Group 2 (Pr4, Pr5, Pr6, Pr10): These projects are all vision domain projects developed by overseas teams.

- Group 3 (Pr2, Pr3, Pr7, Pr9, Pr11): These projects have all been in commercial service for more than two years.

- We also confirm that commercial projects (Group 3, average maturity level 2.34) tend to have higher maturity levels than research projects (Group 1, average maturity level 1.35).

4.1.3. Correlations among AI-MM Processes

In order to find relationships among the 13 processes of AI-MM based on 13 AI projects, we also used Pearson correlation analysis. The results are shown in Table 10. Based on this analysis, the processes with Pearson coefficients above 0.7 are analyzed as follows:

Table 10.

Pearson coefficients among processes of AI-MM based on 13 AI projects (bold font is used for coefficients with an R value above 0.7).

- “Software requirements analysis” is highly correlated with three processes (i.e., Software architecture design (R = 0.710), Performance evaluation of the AI model (R = 0.736), and Final AI model management (R = 0.803)), indicating that it serves as the most basic process for AI development.

- There is a high correlation (R = 0.760) between “Data cleaning” and “Data preprocessing”, so they could be integrated into one in the future.

- The relationship between “Performance evaluation of AI model (PEA)” and “Data preprocessing (DPR)” is high (R = 0.741), suggesting that the DPR activity must be performed well in advance in order to perform PEA well.

- “Final AI model management” is highly related to “Software architecture design” (R = 0.763); in order to increase the “Final AI model management” capacity, it is necessary to comply with “Software architecture design” and “Software requirements analysis” since they are the basic processes of AI development.

4.1.4. Correlations among AI-MM Base Practices

In order to find correlations among 53 base practices of AI-MM, the assessment results of 13 projects were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test [36], which can be used to find interrelations between categorical variables. The results show that most base practices are independent, except for the following pair of base practices:

- The two base practices of “User-conscious design” (design by considering characteristics and constraints of AI system users) and “Data preprocessing result record” (record a data preprocessing process and provide a reason if not necessary) show a strong relationship, with a p-value of 0.016. Since they provide opposite results, as shown in Table 11, they could be integrated into one in the future.

Table 11. Part of Fisher’s exact test results among base practices (p-value is below 0.05).

Table 11. Part of Fisher’s exact test results among base practices (p-value is below 0.05).

4.2. “Pr9” Case Study: Evaluating the Effectiveness of AI-MM

4.2.1. Project Description

This project (Pr9) is a language translation service that provides translation, reverse translation, and translation modification functions for eight different languages (e.g., Korean and English). To apply AI-MM, we conducted assessments with project leaders, project managers, and technical leaders. At first, various documents including design documents and test reports were checked in advance, and AI checklists (i.e., base practices) were delivered to conduct surveys. After that, we analyzed the responses and carried out additional interviews to clarify ambiguous or insufficient answers. We finally assessed the maturity of this project and checked the effectiveness of AI-MM.

4.2.2. Assessment Results

As described in Section 3, AI-MM consists of 5 process areas, 13 processes, and 53 base practices. In addition, the base practices can be divided into common AI practices, fairness-specific practices, and safety-specific practices. In order to confirm the effectiveness of AI-MM in various aspects, we analyzed the assessment results of 13 AI projects with subsets of AI-MM, as follows:

- AI-CMM: A maturity model with 24 Common AI practices

- AI-FMM: A maturity model with 13 Fairness practices

- AI-CFMM: A maturity model with 37 Common and Fairness practices

- AI-MM: A total maturity model with 53 Common, Fairness, and Safety practices

The language translation service is assessed to have high capability levels with respect to AI fairness processes; accordingly, it shows a high level of fairness as a language translation service for a global IT company. Some results of applying AI-MM (Table 12) are explained as follows:

Table 12.

Assessment results of language translation by AI-MM.

- AI-CMM (Common): Processes and base practices commonly applied to AI software development are well established at the organizational level, and the development team of this project also executes and respects the processes and practices well.

- AI-FMM (Fairness): This project is assessed to have level 2 or 3 capabilities in most processes. However, organizational preparation and efforts to ensure the fairness of AI are partially insufficient compared to the common maturity model (AI-CMM). Table 13 shows the AI-FMM maturity level in detail.

Table 13. Assessment results of language translation by AI-FMM (Fairness).

Table 13. Assessment results of language translation by AI-FMM (Fairness).

Specifically, to check the practicality of the fairness maturity assessment results, we looked into what fairness issues were detected during the actual language translation service and compared this service with a state-of-the-art commercial language translation service provided by a global IT company. Table 14 shows the comparison results for fairness issues identified in the two services. Both services have similar gender-bias issues, showing that our service has a fairly high and commercial-level quality of fairness, as compared to the global IT company service. Gender issues appear more frequently in Korean-to-English translations; unlike Korean, which uses more words that are not gendered, English often uses words that reveal specific genders.

Table 14.

Comparison of fairness issues in two language translation services.

To provide the characteristics of the AI model transparently, an AI model card (Table 15) of this AI project was documented and used intensively to assess capabilities. For example, it was checked by an AI model card that shows fairness policies and design information, such as “It is equipped with the function of filtering abusive language that can offend users when outputting machine translation results.”

Table 15.

Part of the AI model card of the language translation project.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposed a new maturity model for trustworthy AI software (AI-MM) to provide risk inspection results and countermeasures to ensure fairness systematically. AI-MM is extensible in that it can support various quality-specific processes, such as fairness, safety, and privacy processes, as well as common AI processes, and it is based on SPICE, a standard framework to access software development processes. To verify AI-MM’s practicality and applicability, we used AI-MM for 13 different real-world AI projects and demonstrated the consistent statistical assessment results on the project evaluation.

To fully support trustworthy AI development, it is required to adapt and extend AI-MM with additional quality-specific processes of trustworthy AI, regarding explainability, privacy, and others. Furthermore, AI-MM needs to be verified with more AI development projects with diverse qualities and scenarios, such as safety-critical autonomous robots and generative chatbots. It is also interesting to discuss how to enforce that AI-MM is used for projects at all stages of AI development, including strict organizational policies or sponsorships from top level managers that incorporate AI process maturity levels into service release requirements. To reduce the time and resources required for AI maturity assessments of AI projects, we need to identify assessment activities in continuous learning AI systems, which could be automated to quickly and intelligently assess various AI projects by learning previous AI project assessment results. These research directions will help improve the reliability of AI products, such as AI robots, which must guarantee various qualities (e.g., fairness, safety, and privacy), provide a foundation for enhancing companies’ brand values, and prepare for AI standard trustworthy certification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C.; methodology, S.C. and H.W.; formal analysis, I.K. and H.W.; investigation, I.K.; resources, S.C.; data curation, I.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K. and I.K.; writing—review and editing, S.C., H.W. and W.S.; visualization, J.K. and I.K.; supervision, W.S.; project administration, I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Institute for Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) under grant No. 2022-0-01045 and 2022-0-00043, and in part by the ICT Creative Consilience program supervised by the IITP under grant No. IITP-2020-0-01821.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and our Samsung colleagues Dongwook Kang, Jinhee Sung, and Kangtae Kim for their work and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stone, P.; Brooks, R.; Brynjolfsson, E.; Calo, R.; Etzioni, O.; Hager, G.; Hirschberg, J.; Kalyanakrishnan, S.; Kamar, E.; Kraus, S.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Life in 2030. In One Hundred Year Study on Artificial Intelligence: Report of the 2015–2016 Study Panel; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA; Available online: http://ai100.stanford.edu/2016-report (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Balakrishnan, T.; Chui, M.; Hall, B.; Henke, N. The state of AI in 2020. Mckinsey Global Institute. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/mckinsey-analytics/our-insights/global-survey-the-state-of-ai-in-2020 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Needhan, M. IDC Forecasts Improved Growth for Global AI Market in 2021. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210223005277/en/IDC-Forecasts-Improved-Growth-for-Global-AI-Market-in-2021 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Babic, B.; Cohen, I.G.; Evgeniou, T.; Gerke, S. When Machine Learning Goes off the Rails. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2021. Available online: https://hbr.org/2021/01/when-machine-learning-goes-off-the-rails (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Schwartz, O. 2016 Microsoft’s Racist Chatbot Revealed the Dangers of Online Conversation. IEEE Spectrum. Available online: https://spectrum.ieee.org/in-2016-microsofts-racist-chatbot-revealed-the-dangers-of-online-conversation (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Dastin, J. Amazon Scraps Secret AI Recruiting Tool That Showed Bias against Women. MIT Technology Review. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight-idUSKCN1MK08G (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Telford, T. Apple Card Algorithm Sparks Gender Bias Allegations against Goldman Sachs. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2019/11/11/apple-card-algorithm-sparks-gender-bias-allegations-against-goldman-sachs/ (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Kayser-Bril, N. Google Apologizes after Its Vision AI Produced Racist Results. AlgorithmWatch. Available online: https://algorithmwatch.org/en/google-vision-racism/ (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Yadron, D.; Tynan, D. Tesla Driver Dies in First Fatal Crash while Using Autopilot Mode. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/jun/30/tesla-autopilot-death-self-driving-car-elon-musk (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Google. Artificial Intelligence at Google: Our Principles. Available online: https://ai.google/principles/ (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Microsoft. Microsoft Responsible AI Principles. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/ai/our-approach?activetab=pivot1%3aprimaryr5 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Gartner. Gartner Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends for 2023. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/articles/gartner-top-10-strategic-technology-trends-for-2023 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- European Commission. Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2759/346720 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Laying Down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and Amending Certain Union Legislative Acts. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021PC0206 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Dilhara, M.; Ketkar, A.; Dig, D. Understanding Software-2.0: A Study of Machine Learning Library Usage and Evolution. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2021, 30, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.M.; Harman, M.; Ma, L.; Liu, Y. Machine Learning Testing: Survey, Landscapes and Horizons. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2022, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Uslu, S.; Rittichier, K.; Durresi, A. Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence: A Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, N.; Morstatter, F.; Saxena, N.; Lerman, K.; Galstyan, A. A Survey on Bias and Fairness in Machine Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chen, C.; Xing, Z. Exploring AI Ethics of ChatGPT: A Diagnostic Analysis. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.12867v3. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M.; Wu, S.; Zaldivar, A.; Barnes, P.; Vasserman, L.; Hutchinson, B.; Spitzer, E.; Raji, I.D.; Gebru, T. Model cards for model reporting. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Atlanta, GA, USA, 29–31 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Cantallops, M.; Sánchez-Alonso, S.; García-Barriocanal, E.; Sicilia, M.A. Traceability for Trustworthy AI: A Review of Models and Tools. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2021, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Tadesse, G.A.; Ho, D.; Fei-Fei, L.; Zaharia, M.; Zhang, C.; Zou, J. Advances, challenges and opportunities in creating data for trustworthy AI. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2022, 4, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, N.; Perwaiz, A.; Arif, J.; Mirza, E.; Ishaque, A. CMMI/SPICE based process improvement. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Management of Innovation & Technology, Singapore, 2–5 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Automotive SIG. Automotive SPICE Process Assessment/Reference Model. Available online: http://www.automotivespice.com/fileadmin/software-download/AutomotiveSPICE_PAM_31.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Goldenson, D.R.; Gibson, D.L. Demonstrating the Impact and Benefits of CMMI: An Update and Preliminary Results; Software Engineering Institute: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- CMMI Product Team. CMMI for Development, Version 1.2. 2006. Software Engineering Institute. Available online: https://resources.sei.cmu.edu/library/asset-view.cfm?assetid=8091 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Becker, J.; Knackstedt, R.; Poeppelbuss, J. Developing Maturity Models for IT Management—A Procedure Model and its Application. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2009, 1, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breck, E.; Cai, S.; Nielsen, E.; Salib, M.; Sculley, D. The ML Test Score: A Rubric for ML Production Readiness and Technical Debt Reduction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Boston, MA, USA, 11–14 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Amershi, S.; Begel, A.; Bird, C.; DeLine, R.; Gall, H.; Kamar, E.; Nagappan, N.; Nushi, B.; Zimmermann, T. Software Engineering for Machine Learning: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering in Practice, Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–31 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Akkiraju, R.; Sinha, V.; Xu, A.; Mahmud, J.; Gundecha, P.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Schumacher, J. Characterizing Machine Learning Processes: A Maturity Framework. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Process Management, Sevilla, Spain, 13–18 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.; Kim, I.; Kim, J.; Kim, K.; Woo, H.; Shin, W. A Study on a Maturity Model for AI Fairness. KIISE Trans. Comput. Pract. 2023, 29, 25–37. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. ISO/IEC TR 24028:2020 Information Technology—Artificial Intelligence—Overview of Trustworthiness in Artificial Intelligence. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/77608.html (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Emam, K.; Jung, H. An empirical evaluation of the ISO/IEC 15504 assessment model. J. Syst. Softw. 2001, 59, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benesty, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Cohen, I. Pearson correlation coefficient. In Noise Reduction in Speech Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Maaten, L.; Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Upton, G.J. Fisher’s exact test. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 1992, 155, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).