Abstract

The rate of type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) is dramatically increasing worldwide. Continuing diabetes mellitus (DM) care needs effective self-management education and support for both patients and family members. This study aimed to review and describe the impacts of diabetes mellitus self-management education (DSME) that involve family members on patient outcomes related to patient health behaviors and perceived self-efficacy on self-management such as medication adherence, blood glucose monitoring, diet and exercise changes, health outcomes including psychological well-being and self-efficacy, and physiological markers including body mass index, level of blood pressure, cholesterol level and glycemic control. Three databases, PubMed, CINAHL, and Scopus were reviewed for relevant articles. The search terms were “type 2 diabetes,” “self-management,” “diabetes self-management education (DSME),” “family support,” “social support,” and “uncontrolled glycaemia.” Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines were used to determine which studies to include in the review. Details of the family support components of DSME intervention and the impacts of these interventions had on improving the health outcomes patients with uncontrolled glycaemia patients. A total of 22 intervention studies were identified. These studies involved different DSME strategies, different components of family support provided, and different health outcomes to be measured among T2D patients. Overall, family support had a positive impact on healthy diet, increased perceived support, higher self-efficacy, improved psychological well-being and better glycemic control. This systematic review found evidence that DSME with family support improved self-management behaviors and health outcomes among uncontrolled glycaemia T2D patients. The findings suggest DSME models that include family engagement can be a useful direction for improving diabetes care.

1. Introduction

Worldwide prevalence of type II diabetes mellitus (T2D) is steadily increasing. In 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) (2014) estimated that 422 million people have been diagnosed with DM globally [1]. In the Asian region, the estimated percentage of T2D could be more than 60% of people by 2030 [2]. Only 14.3% of the total diabetes patients meet the target goals for good glycemic control while a staggering 85.7% fail to meet target goals of glycemic control as measured by Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level [3].

The HbA1c level is a commonly used for glycemic control among T2D patients. It is an endocrine test averaging blood sugar concentrations over the previous three months [4]. HbA1c levels greater than 7% are considered uncontrolled glycaemia [5].

Uncontrolled glycaemia T2D patients are associated with serious multiple long-term complications, including constriction of blood vessels, nephropathy and retinopathy, peripheral neuropathy, and problems of the cardiovascular system [6]. Factors linked with uncontrolled glycaemia in T2D patients include unhealthy eating habits, physical inactivity, nonadherence to medication, and lack of regular blood glucose monitoring [7].

Managing DM is the cornerstone of preventing long-term complications and improving the quality of life among people with T2D [8]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) has presented Diabetes self-management education (DSME) as a foundation for good diabetes care. One reason is that DSME is so important because managing T2D is complex. Patients are given multiple tasks: they have to attend medical appointments regularly, adhere to verifying medication regimens and engage in self-care behaviors including at-home blood glucose monitoring, healthy dietary changes, and increased physical activity [3]. However, it is often difficult for people to consistently engage in various health behaviors necessary for good glycemic control. Common barriers include competing for daily demands, frustration, other emotional distress, and low self-commitment [9]. In addition, lack of knowledge, low levels of self-efficacy to successfully complete an activity, and insufficient social support from family members has been associated with poor diabetes self-management [10]. Some studies reported that family support has a positive effect on patients’ self-management behaviors [10,11].

Because people with DM2 are nested within their families and larger social environment, these factors can also influence a patient’s diabetes care. Family members are key sources of both instrumental and emotional support. Instrument support includes helping patients’ complete specific tasks, such as making an appointment with health care providers or helping with insulin injections while, emotional support can include providing comfort and encouragement when patients face distress or frustration over the long course of their diabetes care [12,13]. Recognizing the influence family can have diabetes care guidelines include the provision of diabetes education to family members or incorporate family support as part of the patient’s diabetes care plan. In this way, educations programs that focus only on the individual could be limited.

Though the benefit of family support is commonly discussed, few comprehensive reviews have explicitly explored this issue in the DSME literature. Therefore, this study aims to review DSME interventions that emphasize family support as a fundamental concept to enhance patients’ self-management, describe their components, and examine the relationship between DSME with family support interventions and diabetes-related outcomes among patients with T2D.

2. Objective

The study aimed to review and describe the impact of DSME that involves family members on patient outcomes related to patient health behaviors such as medication adherence, blood glucose monitoring, diet and exercise changes, psychological well-being and self-efficacy, and physiological markers including body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol level and glycemic control.

3. Methods

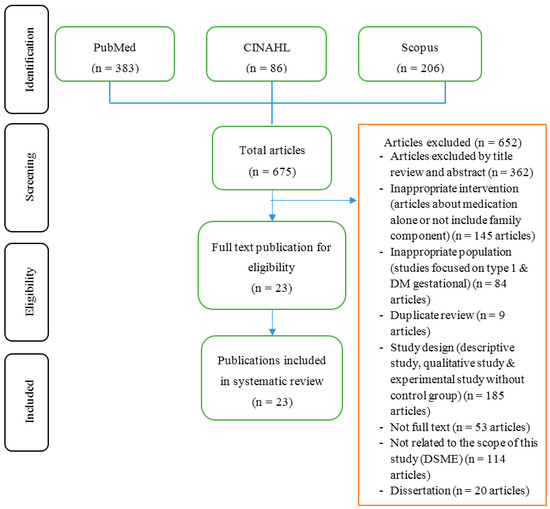

This review described the impact of family involvement in DSME among patients with uncontrolled glycaemia. We used the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) statement of all stages of the review. Three searches were conducted, yielding 675 articles after duplication removed. For all initial strategies, family support, social support, and uncontrolled glycaemia were the main search terms and were entered as the medical subject heading (MeSH) in the abstract and title field. Titles were eliminated if the research involved type 1 diabetes or gestational diabetes, or were not written in English. This produced 102 abstracts to examine for full article review. This initial review includes 23 articles that almost have relevance to the systematic review.

3.1. Eligibility Criteria

The PICO (Participant-Intervention-Comparison-Outcomes) format, based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (2014) [14], was used to create the criteria inclusion for reviewing the articles. Utilizing any treatment strategies (e.g., usual care, didactic method, participatory learning, internet-based methods) were included in this review. Description of what an inappropriate subject (e.g., articles about diabetes medication alone or intervention that did not include a family component) should include a representative list of reason articles were excluded based on this review. Types of design studies such as single design, descriptive design, qualitative research, no control group, not published in an academic journal (e.g., unpublished dissertation) and studies focused on diabetes prevention or targeting gestational diabetes population were also excluded.

The primary outcome measure was glycaemic control in the past 3 months indicated by patient HbA1c levels. Secondary outcome measures included self-reported on self-care behaviors (e.g., diet, physical activity, blood glucose monitoring, foot care and inspection, and medication adherence), physiological outcomes (e.g., HbA1c, blood glucose level BGL, BP, BMI, lipid profile), and self- reported on levels of self-efficacy and social support from family.

3.2. Search Strategy

The search strategy used to find the relevant articles included “type 2 diabetes (T2D),” “self-management,” “diabetes self-management education,” “family support,” “social support” and “uncontrolled glycemic.” Available titles and abstracts of articles were systematically reviewed for their relevance to the topic of DSME involving family support.

3.3. Study Selection

This study searched Pubmed, CINAHL, and Scopus databases for articles published between 2008 and 2016. Relevance abstracts were reviewed and duplicate articles were removed.

3.4. Synthesis of Results

The results of this review are explained narratively. The description of the results explain: (1) diabetes self-management education (DSME) programs; (2) how to integrate family support in DSME programs; and (3) assess the impact of these programs on health behaviors, physiological outcomes, and clinical health outcomes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of evidence search and selection.

4. Results

Twenty-three studies examine the impact of DSME with a family support program on outcomes among uncontrolled glycaemia T2D. Nineteen studies were randomized controlled trials (RCT) [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35], three studies were conducted in the quasi-experimental design [16,36,37], and two studies used a mixed-method design, of which 23 studies were conducted in Western countries [15,16,17,19,20,21,22,25,26,27,28,29,30,32,33,34,35,36,37], whereas only one study was undertaken in Asian countries [24].

4.1. DM Self-Management Education (DSME)

We found that 40.9% of the studies [15,16,19,23,26,28,32,33,35] used an individual format and 59.1% used a combination of individuals and group format [15,17,18,20,23,24,30,34,35,37]. In general, both types of program included personalized counseling, goal-setting, problem solving, and explanation of ways in which family members can support self-care practice and follow-up sessions.

4.1.1. Teaching Strategy

In general, DSME was either primarily didactic, such as an educational class offering learning material followed by discussion or they involved more participatory learning (encouraging patients’ active involvement in the learning process, with group discussion sessions, goal setting, negotiation, and problem solving), or they adopted a mixed approach combining both didactic and participatory learning.

16 of the 23 studies combined both didactic and participatory learning with strategies including goal setting, action planning, problem solving and follow-up strategies [17,18,19,21,22,24,25,26,27,30,32,34,35,36,37]. To improve the T2D self-management knowledge and communication skills, one study offered a DVD-based training program [20]. Another study incorporated Bluetooth technology to deliver health information via a supplied modem to the remote secure server. Patients were also given advice on lifestyle modification and how to contact their medical providers [15]. Aikens’ study expanded a DVD-based training program to enhance communication skills [38]. Another study presented a cooking class to demonstrate healthful foods [23]. One study offered diabetes Tele-monitoring calls using the mHealth + CarePartner (CP) to improve diabetes self-management and support blood glucose monitoring [29].

4.1.2. Educational Materials

The education materials in this review varied across different studies. One study used Bluetooth technology to deliver the diabetes information [15]. Four studies used food models, food bingo and food pictures to illustrate healthy diet and food portion size [17,21,23,27]. Diabetes handouts/booklets (diet, exercise, medication, eye and foot self-care) were used to disseminate knowledge [18,19,22,24,33,35,39]. In addition, four studies [16,17,23,37] used video and DVD to demonstrate successful self-care behaviors and practices among patients with diabetes and two studies provided the simple padometer for blood glucose self-monitoring at home [25,28].

4.1.3. Follow-Up

Follow-up strategies are essential components in diabetes care to sustain self-management behaviors. This review verified that 10 studies followed up on their programs in a face-to-face context [15,18,20,25,26,27,30,33,36,37]. Five studies followed up on their programs by telephone [16,17,28,29,35], seven studies mixed face-to-face follow-up and telephone or computer-based follow-up strategies [16,21,22,23,32,35,40].

4.2. Integration of Family Support in the DSME Program

Recently, DSME programs have been incorporated into primary care units and the community. Regardless of the setting, the effectiveness of communication and supporting skills are also important in influencing diabetes management behaviors and promoting effective day to day coping [41]. 13 of 23 studies involved patients and family members as a unit intervention and required family members to attend the education classes or meetings [17,18,22,23,24,25,27,29,30,32,34,35,36,37], and 8 studies asked family members to provide support in relieving stress, denial, and maximizing environmental conditions [15,16,19,20,21,26,33,35].

In the study of Keogh et al., family members were needed to assist and support patients in self-management practices by helping patient with strategic planning, goal setting, and problem-solving. Effective feedback concerning negative perceptions of diabetes was used for exchanging health information, reducing care resistance and building self-efficacy emphasized by family members [22].

In other studies, patients received interactive voice response (IVR) calls to monitor the barriers of self-management, medical check-up seeking and connecting with family members. Patients’ improvement record, emotional support as well as problem-solving were also handled by family members [16,38].

A study was conducted using the social cognitive theory, focusing on how environmental change enhances self-efficacy, diabetes self-management and overcoming barriers. Family members emphasized cultural beliefs and values to support dietary change, physical activity, and blood glucose monitoring [17].

One study suggested augmenting communication skills using a speakerphone among couples to support and solve problems of behavior change This program focused on discussion tasks, goal setting and problem-solving to improve the communication skill, achieve goals tailor interventions among uncontrolled glycemia DM2 [42].

In Ananda’s study participants received a mHealth + CarePartner (CP) program to monitor self-management behavior while family members were instructed to provide guidance and support for self-management and help assess barriers to effective self-management behavior [29]. During the program, the summary of result achievements was sent to the patient and their family members to facilitate supportive relationships in order to reinforce the importance of achieving good glucose control.

Regarding emotional supportive behaviors, 7 studies addressed psycho social problems such as feelings of denial, the presence of discordant conditions (e.g., negative response to diabetes self-management, seasonality of mood disorder and the presence of depression in medical illness) and retirement that might occur among patients with diabetes [17,22,25,26,38].

The impact of family support integrated with DSME has been shown to be cost-effective and reduced risks of DM2 complications [13], improved HbA1c levels by as much as 1% [15,18,21,22,24,25,27,35,36] and has a positive effect on psychosocial [38], self-efficacy [17,27], dietary and exercise behavior aspects [22], perceived support [18], knowledge [35], medication adherence and quality of life [35]. It clearly confirmed that DSME with family support is an important factor in controlling blood glucose DM2.

A study comparing diabetes management both with and without family involvement found that patients enrolling with an informal caregiver had a higher rate of engagement and more likely to decrease blood glucose level and to regularly check the blood glucose as well [38]. The practical and emotional support received by family members had a positive influence on global measures of disease management in diabetic patients [10].

Another study reported that elderly patients whose spouses involved with them found greater improvements in knowledge, metabolic control, and stress level compared those who participated alone. Involving family members in the program for elderly patients is important to provide instrumental and emotional support related to diabetes management [13]. The DSME with family support program helped the diabetic patients who had difficulty adhering to diabetes management including educating patients about how to manage living with diabetes; to allow patients to discuss the feeling and accompanying behavior changes associated with diabetes; to facilitate self-esteem and help patients overcome barriers; to develop solutions and techniques to maintain a proper diet; and to help patients develop supportive relationships among family members to maintain diabetes management over time [10,41].

4.3. Effectiveness of Family Support Integration on Diabetes Outcomes

DSME with family support has a significant effect on health outcomes according to existing studies in this review. The outcomes have been classified into five categories, including self-management behaviors (diet, physical activity, blood glucose monitoring, foot infection and medication adherence), physiological outcomes, self-efficacy and social support and clinical outcomes (HbA1c/blood glucose level, blood pressure, BMI status, and lipid profile), as described below.

4.3.1. Self-Management Behavior Outcomes

23 articles examined the impact of DSME with family support on self-care behaviors. Strong evidence was given that following good self-management behaviors, including diet, physical activity, blood glucose monitoring, foot inspections and medication adherence significantly improved the clinical outcomes and could prevent long-term complications [5]. 2 studies reported a positive impact on healthy dietary intake [30,34] after receiving the program. One other study showed appropriateness in selecting healthful food and food exchange [20], while 5 studies improved the level of exercise behavior [16,24,30,34,37]. All of those studies showed a high level of family support integration with DSME program.

In addition, when the correlation between perceived support with blood glucose monitoring was examined, 4 studies confirmed that a higher level of support significantly influence blood glucose monitoring at home [16,17,20,23,27,37]. Regarding medication taking behavior, seven studies demonstrated that regular medication adherence was performed under family support [17,18,21,22,23,24]. Furthermore, this review confirmed that increased self-awareness on foot inspections correlated to foot ulcer prevention [16,37].

In contrast to related studies, 4 studies showed medication adherence did not improve significantly in relation to family support [15,23,25,26]. It could be correlated with low family participation [23], understanding of patient and family member roles and patients’ adoption of medication adherence in the long term period [25]. Those opposing results indicated that study limitation had minimized the results.

4.3.2. Psychological Outcomes

As an approach to explore the psychological problems in managing self-care behaviors, barriers related to the psychosocial dimension were reviewed. Emotional responses were associated with poor diabetes self-management and glycemic control, including feeling discouraged by diabetes treatment, worry about long-term complications and incorrectly defining the concrete goals for diabetes care [7]. Twelve of 23 studies reported that higher levels of family support had a positive impact on reducing depressive symptoms [16,18,25,29] and positive emotional control [19], psychosocial well-being [22,34,37], quality of life [29,35] and diabetes related to distress [20]. As a result, less depression had a positive impact on self-management behavior and certain clinical outcomes.

4.3.3. Self-Efficacy

5 review studies explained that patients who have higher perceived support demonstrate significantly better self-efficacy [15,17,19,23,27]. One study received a one-on-one tailored education session and bi-weekly follow-up to influence self-efficacy when performing self-management [35]. This self-efficacy enhancing program could improve self-confidence on diabetes self-management behaviors and glycaemia control.

4.3.4. Social Support Perceived

Social support is a fundamental approach to sustaining self-management behaviors and overcoming barriers among patients with diabetes. 6 experimental studies described the impact of family support interventions to increase perceived social support on self-management among T2D patients [15,16,18,25,26,39]. Individual who receives support is capable of getting advice when coping with difficulties and improving positive communication for diabetes care. It could be a positive impact on a positive relationship between patients and family members on diabetes self-management behaviors. For this reason, social support from family was effective in improving the diabetes self-management behaviors.

4.3.5. Clinical Outcomes

23 articles examined the effect of DSME with family support on clinical outcomes. Ten studies showed the improvement on HbA1c [15,18,21,23,24,25,27,33,34,35] after succeeding in diabetes self-management. 5 studies focused on dietary modification support to improve blood pressure level [15,23,24,29,32], body mass index [15,36], and lipid profile [24,32,35]. The higher level of support has remained a strong factor for the success of self-care behaviors.

In contrast, 2 studies confirmed that there was no significant change in the level of triglycerides and BMI [28]. This could be linked to the low level of peer support over a long-term period. Other studies also showed no significant of changes in HbA1c levels [32,35,37].

5. Discussion

We conducted a systematic review of 23 existing studies related to the impact of DSME involving the family as a fundamental source of social support on self-management among T2D patients between 2008 and 2016. The results confirmed the impact of family integration on several health outcomes of T2D. Various studies employed strong study designs such as randomized controlled trials [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

DSME is often generated by individual and group education. This strategy offers a combination of didactic teaching and interactive or participatory learning approaches. A collaborative approach to DSME mixed methods of teaching and family support involvement [15,17,18,20,23,24]. The combination of didactic with other methods such as participatory learning, goal setting, action planning and problem-solving had a positive impact on health outcomes and improved health behaviors [16,20,21,22,23,24,26].

This literature review also found that family involvement using a collaborative approach was widely involved across studies. Many studies incorporated the details of family members in program activities such as providing emotional support regarding problem-solving and helping patients to solve their emotional distress or provide information and roles to facilitate, accommodate, remind, motivate and partner with behavior change and perform tasks. Some studies in this literature review found that family members were included in an intervention program. However, they lacked information about how family members provided support of diabetes self-management behaviors, interacted in the program or what family outcomes should be addressed in the intervention. Only a few studies described the role of family members using a participatory learning approach. To effectively engage family members in the intervention, a clear understanding of the theoretical basis of involving family members is needed to serve the T2D patients when performing self-management behaviors.

The duration of the intervention and follow-up was measured using the length of the intervening period from the pretest until completing the program. In the short term, interventions conducted using several strategies, including weekly telephone follow-ups, face-to-face follow-ups, negotiating, and discussing to design the goals and action plan and modify the goals and action plan were more effective in improving health outcomes [15,16,18,20,21,22,23,26].

The follow-up method is an essential component in diabetes self-management among patients with chronic conditions. Generally, follow-up methods are categorized into four strategies, including computer-based, phone call, short message service (mail) and home visits. Different follow-up methods are used to assess the patient’s experience of the program, identify barriers and problem-solving approach to address barriers, to revise the goals and action plan and reinforce any successful performance dietary and exercise self-management. The combination of telephone and face-to-face follow-up is very effective for monitoring the patients’ achievement and its significantly improves the health outcomes by increasing knowledge and self-efficacy to carry out self-management behaviors [16,21,22,23,32,35].

A study that assessed the outcomes found a significant improvement in clinical outcomes such as HbA1c, blood pressure, lipid profile and BMI status after implementing the program. 3 studies mentioned that not significant change of HbA1c level was observed in the short intervening period [20,23,26]. Other issues involving self-care that is often faced by patients with diabetes are to maintain the improved behaviors after the end of the intervention period. However, engaging family members could help patients strengthen self-management interventions and lengthen the effectiveness gained from the intervention [40,41,42,43].

6. Strength & Limitations

In this review, we examined many studies involving family members in diabetes self-management with randomized control trial (RCT) designs and some of the studies conducted using a quasi-experimental design. However, some limitations were still encountered. Heterogeneous methods, strategies, populations, settings, and outcomes made it difficult to compare the effect size of each study. Even though we created this systematic review by hand-tracking, there may have been some studies related to family support for diabetes self-management that remain unidentified and excluded because they did not describe family involvement or did not report specific outcomes of diabetes. This review study was limited by publication bias because positive findings tend to be published more frequently than null findings. In addition, the decision to describe the result in a narrative form rather than as a meta-analysis because we did not have access to primary data and the variability in study design did not allow us to pool data. Therefore, we could not describe the effect size of each study outcome.

7. Conclusions

Developing diabetes interventions with family support is an integral part of sustaining self-management behaviors and improving the health outcomes of T2D patients. In conclusion, this systematic review found that DSME with family support improves health outcomes for patients with uncontrolled glycaemia. Further study needs to provide details of DSME in the intervention and compare the health outcomes with and without family involvement in DSME programs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Family support integrated with diabetes self-management and health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mahidol University for facilitating the database search for conducting this review. The authors would like to give special thanks also to Thomas McManamon from the Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University, for improving the writing style of this manuscript. Our special thanks to the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP Scholarship) for study grant support. Finally, the authors would like to thank the China Medical Board for supporting the publication costs of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Rian Adi Pamungkas and Kanittha Chamroonsawasdi designed the research. Rian Adi Pamungkas analyzed and wrote the review paper. Kanittha Chamroonsawasdi edited the paper and Paranee Vatanasomboon advised on this study.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare no conflict of interest in this manuscript. The funding sponsors also had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to publish this manuscript.

References

- American Diabetes Association. Foundations of care: Education, nutrition, physical activity, smoking cessation, psychosocial care, and immunization. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, S20–S30. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, N.; Attia, J.; Oldmeadow, C.; Scott, R.J.; Holliday, E.G. The architecture of risk for type 2 diabetes: Understanding Asia in the context of global findings. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care 2014, 37 (Suppl. 1), S14–S80. [Google Scholar]

- Radin, M.S. Pitfalls in hemoglobin A1c measurement: When results may be misleading. J. Gen. Int. Med. 2014, 29, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013, 40 (Suppl. 1), S11–S66. [Google Scholar]

- Long, A.N.; Dagogo-Jack, S. Comorbidities of diabetes and hypertension: Mechanisms and approach to target organ protection. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2011, 13, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulman, D.M.; Rosland, A.M.; Choi, H.; Langa, K.M.; Heisler, M. The influence of diabetes psychosocial attributes and self-management practices on change in diabetes status. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 87, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastava, S.R.; Shrivastava, P.S.; Ramasamy, J. Role of self-care in management of diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2013, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, W.T.; Vethakkan, S.R.; Ng, C.J. Why do some people with type 2 diabetes who are using insulin have poor glycaemic control? A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, T.A.; Dimatteo, M.R. Importance of family/social support and impact on adherence to diabetic therapy. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2013, 6, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong-Rieger, D.; Rieger, F.P. Health coaching in diabetes: Empowering patients to self-manage. Can. J. Diabetes 2013, 37, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, E.H.; Austin, B.T.; Davis, C.; Hindmarsh, M.; Schaefer, J.; Bonomi, A. Improving Chronic Illness Care: Translating Evidence into Action. Health Aff. 2001, 20, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, A.A.; Benitez, A.; Quinn, M.T.; Burnet, D.L. Family interventions to improve diabetes outcomes for adults. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1353, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute Joanna Briggs. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2014 Edition; The Joanna Briggs Institute Publisher: Adelaide, Austrialia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, S.H.; Hanley, J.; Lewis, S.C.; McKnight, J.A.; McCloughan, L.B.; Padfield, P.L.; Parker, R.A.; Paterson, M.; Pinnock, H.; Sheikh, A.; et al. Supported Telemonitoring and Glycemic Control in People with Type 2 Diabetes: The Telescot Diabetes Pragmatic Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002098. [Google Scholar]

- Aikens, J.E.; Rosland, A.M.; Piette, J.D. Improvements in illness self-management and psychological distress associated with telemonitoring support for adults with diabetes. Prim. Care Diabetes 2015, 9, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Wallace, D.C.; McCoy, T.P.; Amirehsani, K.A. A family-based diabetes intervention for Hispanic adults and their family members. Diabetes Educ. 2014, 40, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamidreza, K.T.; Farah, M.; Mohsen, K.N.; Mohsen, H.; Gholamhossein, M. Impact of family support improvement behaviors on anti diabetic medication adherence and cognition in type 2 diabetic patients. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2014, 13, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Fall, E.; Roche, B.; Izaute, M.; Batisse, M.; Tauveron, I.; Chakroun, N. A brief psychological intervention to improve adherence in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2013, 39, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robling, M.; McNamara, R.; Bennert, K.; Butler, C.C.; Channon, S.; Cohen, D.; Crowne, E.; Hambly, H.; Hawthorne, K.; Hood, K.; et al. The effect of the Talking Diabetes consulting skills intervention on glycaemic control and quality of life in children with type 1 diabetes: Cluster randomised controlled trial (DEPICTED study). BMJ 2012, 344, e2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, K.A.; Makahi, E.K.; Shea-Solatorio, C.; Yoshimura, S.R.; Townsend, C.K.; Kaholokula, J.K. Outcomes from a diabetes self-management intervention for Native Hawaiians and Pacific People: Partners in Care. Ann. Behav. Med. Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2013, 45, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keogh, K.M.; Smith, S.M.; White, P.; McGilloway, S.; Kelly, A.; Gibney, J.; O’Dowd, T. Psychological Family Intervention for Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes. Am. J. Manag. Care 2011, 17, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.M.; Chang, S.C.; Chen, P.L.; Liu, P.F.; Liu, W.C.; Chang, C.C.; Chang, W. Comparison of family partnership intervention care vs. conventional care in adult patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes in a community hospital: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluding, P.M.; Singh, R.; Goetz, J.; Rucker, J.; Bracciano, S.; Curry, N. Feasibility and effectiveness of a pilot health promotion program for adults with type 2 diabetes: Lessons learned. Diabetes Educ. 2010, 36, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Huidobro, D.; Bittner, M.; Brahm, P.; Puschel, K. Family intervention to control type 2 diabetes: A controlled clinical trial. Fam. Pract. 2011, 28, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, D. Culturally tailored education to promote lifestyle change in Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2009, 21, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosal, M.C.; Ockene, I.S.; Restrepo, A.; White, M.J.; Borg, A.; Olendzki, B.; Scavron, J.; Candib, L.; Welch, G.; Reed, G. Randomized trial of a literacy-sensitive, culturally tailored diabetes self-management intervention for low-income latinos: Latinos en control. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, A.A.; Brown, S.A.; Horner, S.D.; Zuniga, J.; Arheart, K.L. Home-based diabetes symptom self-management education for Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Health Educ. Res. 2015, 30, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, D.P.; Ananda, S.; James, E.A. Randomized Controlled Trial of mHealth Telemonitoring with Enhanced Caregiver Support for Diabetes Self-management. J. Clin. Trials 2014, 4, 194. [Google Scholar]

- Toobert, D.J.; Strycker, L.A.; Barrera, M., Jr.; Osuna, D.; King, D.K.; Glasgow, R.E. Outcomes from a multiple risk factor diabetes self-management trial for Latinas: Inverted exclamation markViva Bien! Ann. Behav. Med. 2011, 41, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toobert, D.J.; Strycker, L.A.; Glasgow, R.E.; Osuna, D.; Doty, A.T.; Barrera, M.; Geno, C.R.; Ritzwoller, D.P. ¡Viva Bien!: Overcoming Recruitment Challenges in a Multiple-Risk-Factor Diabetes Trial. Am. J. Health Behav. 2010, 34, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gary, T.L.; Batts-Turner, M.; Yeh, H.-C.; Hill-Briggs, F.; Bone, L.R.; Wang, N.-Y.; Levine, D.M.; Powe, N.R.; Saudek, C.D.; Hill, M.N.; et al. The Effects of a Nurse Case Manager and a Community Health Worker Team on Diabetic Control, Emergency Department Visits, and Hospitalizations Among Urban African Americans With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 1788–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utz, S.W.; Williams, I.C.; Jones, R.; Hinton, I.; Alexander, G.; Yan, G.; Moore, C.; Blankenship, J.; Steeves, R.; Oliver, M.N. Culturally tailored intervention for rural African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008, 34, 854–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toobert, D.J.; Strycker, L.A.; King, D.; Barrera, M., Jr.; Osuna, D.; Glasgow, R. Long-term outcomes from a multiple-Risk-Factor Diabetes Trial for Latinas: ¡Viva Bien! Behav. Med. Pract Policy Res. 2011, 1, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, T.S.; Funnell, M.M.; Sinco, B.; Spencer, M.S.; Heisler, M. Peer-Led, Empowerment-Based Approach to Self-Management Efforts in Diabetes (PLEASED): A Randomized Controlled Trial in an African American Community. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 1, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, J.M.; Jerica, M.B.; Peter, H.; Betty, G.; Nan, L.-W.; Sheila, W.; Steve, B. The Family Education Diabetes Series (FEDS): Community-based participatory research with a midwestern American Indian community. Nurs. Inq. 2010, 17, 359–372. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, I.C.; Utz, S.W.; Hinton, I.; Yan, G.; Jones, R.; Reid, K. Enhancing diabetes self-care among rural African Americans with diabetes: Results of a two-year culturally tailored intervention. Diabetes Educ. 2014, 40, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aikens, J.E.; Zivin, K.; Trivedi, R.; Piette, J.D. Diabetes self-management support using mHealth and enhanced informal caregiving. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2014, 28, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassmann, H.; de Hair, M.; Danne, T.; Lange, K. Reducing stress and supporting positive relations in families of young children with type 1 diabetes: A randomized controlled study for evaluating the effects of the DELFIN parenting program. BMC Pediatr. 2012, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosland, A.M.; Piette, J.D. Emerging models for mobilizing family support for chronic disease management: A structured review. Chronic Illn. 2010, 6, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, N.S.; Tandon, D.; Mukherji, R.; Tanner, M.; Ghosh, K.; Alam, G.; Haq, M.; Rey, M.J.; Trinh-Shevrin, C. Understanding barriers to and facilitators of diabetes control and prevention in the New York City Bangladeshi community: A mixed-methods approach. Am. J. Public Health. 2012, 102, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trief, P.; Sandberg, J.G.; Ploutz-Snyder, R.; Brittain, R.; Cibula, D.; Scales, K.; Weinstock, R.S. Promoting couples collaboration in type 2 diabetes: The diabetes support project pilot data. Fam. Syst. Health 2011, 29, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomsky, N. What is Special About Language? University of Arizona: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).