Abstract

Intergenerational integration has given rise to a novel aging paradigm known as all-age communities, which is garnering international attention. In China, the aging population and the implementation of the three-child policy have resulted in increased demand for retirement and childcare services among residents in older neighborhoods. Consequently, there is a pressing need to retrofit these older neighborhoods to accommodate all-age living arrangements given the high demand they generate. Therefore, this study undertakes research interviews with residents and constructs an exploratory theoretical model rooted in established theory. To assess the significance of our model, we employ Smart PLS 3.0 based on 297 empirical data points. Our findings indicate that anxiety has a significant negative effect on payment behavior; objective perception, willingness to pay, and government assistance exert significant positive effects on payment behavior. By comprehensively analyzing the mechanisms underlying residents’ payment behavior, this study provides valuable insights for the government for promoting the aging process within communities and formulating effective transformation policies.

1. Introduction

The all-age community concept, originally coined as “lifetime homes” by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and Habinteg Housing Association in the 1990s [1], has gained prominence in addressing the evolving needs of older localities in China. It means that the community should provide residents of all ages with living space, service facilities, and comfortable public spaces, and create a healthy residential area where residents have equal opportunities to participate in daily decision-making. In August 2021, the Chinese Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD) issued a document to strictly regulate large-scale demolition and construction activities during the urban renewal process. Consequently, there is a growing requirement for all-age retrofitting to meet the practical and policy requirements of older localities. At present, China’s aging population situation is grim. According to the forecast of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China will become the country with the highest degree of population aging in the world by 2030 [2]. The recent implementation of the three-child birth policy has led to an increase in the number of children, while the dilapidated infrastructure and single-purpose facilities in older communities pose challenges in meeting the material and psychological needs of the older adults and children under these new circumstances [3]. Given the aging population and the three-child policy, an all-age retrofitting approach focused on intergenerational integration aligns more closely with public demand. Previous studies on all-age community transformation have focused on constructing child- and age-friendly cities, emphasizing developmental goals and facilities [4]. At the mesoscopic scale, this study proposes recommendations for land-use structure, area index, and facility configuration based on the daily activities of the older population and their satisfaction with the environment, adopting the perspectives of living circles and communities [5]. This project aimed to provide essential facilities and services [6], well-organized transportation systems [7], and functional layouts [8] to the older population. The design principles and recommendations are rooted in the life circle and community perspectives. At the micro level, specific design considerations, such as pedestrian space [9], housing planning and design [10], and accessibility [11], received particular attention. The ultimate goal is to construct an all-age community that fosters positive intergenerational interaction, providing residents of all ages with improved living, working, and growing opportunities that enhance their social interactions [12].

A comprehensive literature review of the current research indicated a predominant focus on retrofitting programs, policy recommendations, and visionary goals. However, there is a noticeable dearth of studies examining on residents’ willingness to participate in retrofitting initiatives. Previous studies on willingness to retrofit have identified influential factors by synthesizing the available literature [13]. Nevertheless, these studies have not fully addressed all the influencing factors that may exist beyond the scope of prior research. To address this gap, the present study employs a resident-oriented approach by conducting interviews and drawing on relevant theoretical frameworks to identify influencing factors. These factors serve as the foundation for constructing a theoretical model that analyzes the mechanisms underlying residents’ payment behavior. Presently, the Chinese government assumes the financial burden associated with renovating old communities; however, given the considerable scale of these renovations, solely relying on government financing poses limitations and hampers the progress of these endeavors. The analysis of its internal mechanism has practical significance and can provide a reference for the government to guide the residents of old communities to actively cooperate with the transformation work, promote the process of community aging, and formulate community transformation policies.

2. Methodology and Data Sources

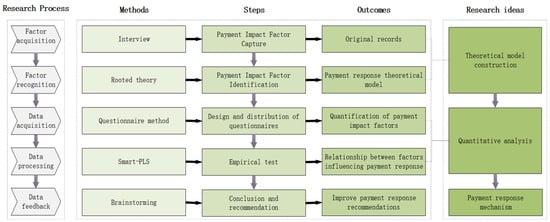

The existing literature indicates the absence of established measurement scales, variable categories, and theoretical hypotheses for studying payment response mechanisms in the context of all-age retrofitting [14]. Empirical research conducted in the field has revealed that residents in older neighborhoods hold diverse understandings of all-age retrofitting, and quantitative research results obtained from large-scale resident surveys based on undifferentiated structured questionnaires may lack validity in capturing their perspectives effectively [15]. To address these limitations, this study designed an unstructured (open-ended) questionnaire to conduct interviews with a representative sample of residents from older neighborhoods, thereby collecting primary information [16]. A qualitative approach was employed to explore the payment response mechanism more effectively [17]. Figure 1 shows the research framework of payment response mechanisms.

Figure 1.

Research framework of payment response mechanisms.

The selection of specific interviewees was guided by a theoretical sampling approach aligned with the theoretical development of the research design [18]. To capture the genuine perspectives from residents, a random selection process was used to identify 24 participants aged 20–60, with financial capability, as interviewees from five representative old neighborhoods in Xi’an and Chengdu, China. Following the concept of information saturation, no new coded content emerged after the inclusion of 24 interviewees, and 2 additional interviewees were recruited to ensure data saturation. Therefore, the final sample size was 24, ensuring a reasonable level of reliability in the obtained results [19]. Detailed information regarding the interviewed participants is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of basic information about the interviewees.

In-depth personal interviews, each lasting approximately 30 min, were conducted as part of the study. The purpose of these interviews was to gain a comprehensive understanding of the interviewees’ attitudes, emotions, and underlying motivations regarding the funding of all-age transformation. During the individualized interviews, the interviewer carefully observed the interviewee’s external expressions and internal psychological states, aiming to create an environment that allowed ample space for reflection and expression [20]. Prior consent was obtained from the interviewees for audio recording. Following the completion of the interviews, the recorded material was meticulously collated, transcribed, and thoroughly reviewed, resulting in a substantial collection of interview transcripts exceeding 10,000 words. Two-thirds of the interview transcripts (16) were randomly selected for coding analysis and model construction, while the remaining transcripts (8) were reserved for testing theoretical saturation.

The present study employed a qualitative research design and adopted an exploratory approach rooted in theory to examine the response mechanism of residents in old neighborhoods towards all-age retrofitting payments. The construction of a theoretical model involved three distinct stages: open, spindle, and selective coding [21], which were facilitated by the use of NVivo 11 software. A continuous comparative analysis was adopted to analyze the data, following the guidelines outlined by the authors of reference [22]. Furthermore, NVivo 11 was used to manage and analyze the qualitative data obtained from the in-depth interviews, aiming to identify the primary factors influencing residents’ payment behavior.

2.1. Category Refinement

2.1.1. Release Codes

Open coding, also known as level 1 coding, involves systematically tagging, coding, and meticulously documenting the initial interview transcripts verbatim, aiming to generate the initial concept from the raw material [23]. Throughout the coding process, careful consideration was given to mitigate personal biases and prejudices by extracting initial concepts as labels directly from the interviewees’ original statements. A comprehensive collection of over 103 original statements and their corresponding initial concepts were obtained through primary extraction. Given the large number of initial concepts and their repetitive nature, a recategorization and regrouping exercise was undertaken [24]. Only the initial concepts that recurred three or more times were retained, while inconsistent or less frequently occurring initial concepts were excluded. For brevity, Table 2 provides a summary of the retained initial concepts and their corresponding categories. To conserve space, three representative information statements and their corresponding initial concepts were selected for each category.

Table 2.

Open coding scoping.

2.1.2. Spindle Coding

Main axis coding, also referred to as associative registration, was employed to explore the inherent logical connections between the initial categories, thereby expanding the main categories and their respective subcategories [25]. By systematically examining the interrelationships and logical sequence of the categories at the conceptual level [26], we organized them into distinct groups. As a result of this coding process, four main categories were identified, each encompassing a range of open coding categories. The comprehensive details of this classification, including the main categories and their associated open coding categories, are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Master categories formed using spindle coding.

2.1.3. Selective Coding

Selective coding, referred to as core logging, was employed to identify and elucidate the core categories derived from the main categories. The core categories were analyzed in relation to the main categories as well as other relevant categories. The purpose was to depict the underlying phenomena and behavioral conditions in a coherent and narrative manner, resulting in the development of a novel substantive theoretical framework [27,28].

This study identified the core category of “payment response mechanisms for all-age adaptations,” which served as the central focus for the subsequent narrative. The resulting “storyline” can be summarized as follows: the three main categories, namely anxiety, objective perception, and external situation, all of which exert a significant influence on the payment response mechanisms. Anxiety emerged as an internal driving force that inversely impacts residents’ willingness to pay for all-age adaptations, whereas objective perceptions and external situation act as moderating factors, shaping individuals’ willingness to pay. Drawing upon this “storyline”, we constructed and developed a model of payment response mechanism known as the “All-age Payment Response Mechanism Model” or the “Situation-Willingness-Response Integration Model” (SWRM). This model captures the interplay and integration of various factors within the payment response mechanism. The intricate relationship structures of the main categories in this study are presented in detail in Table 4.

Table 4.

Typical relational structure of the main categories.

2.1.4. Mediating Variables

Ajzen [29] suggests that individual behavioral intentions are not always seamlessly translated into behavioral responses, indicating that external factors, such as facilitative conditions, also play a significant role in this process [30].

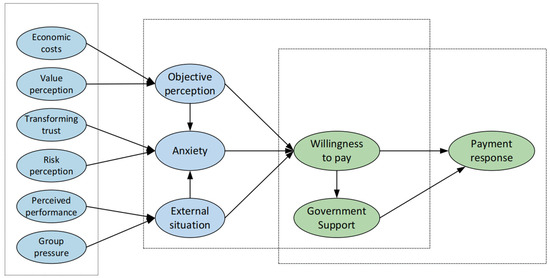

Drawing upon the theory of interpersonal behavior, the present study introduces the mediating variable “government assistance” within the theoretical model, aiming to account for the mediating effect it exerts between willingness to pay and the actual payment response. Figure 2 illustrates the proposed theoretical model.

Figure 2.

Situation-willingness-response integration model.

2.2. Willingness to Pay Influencing Factors Analysis

Table 5 presents detailed descriptions of the ten primary influencing factors, which were extracted using the previous category extraction process.

Table 5.

Explanatory table of influencing factors.

2.3. Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

2.3.1. Research Hypothesis

To analyze the structure of the constructed payment response mechanism, a structural equation model was selected as the analytical framework to assess the direct and indirect effects of relevant factors [41]. This selection was motivated by the capability of structural equations to integrate several similar potential variables into a unified “block variable” and then analyze their causal relationships. Consequently, this method aligns with the analytical rationale of this study and offers an ideal approach to analyze multiple influencing factors.

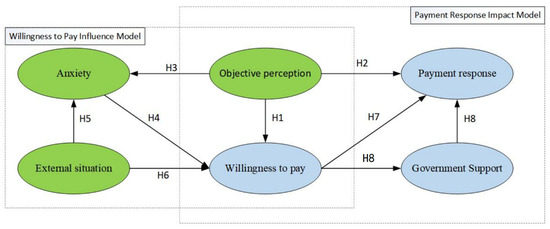

Through a thorough theoretical analysis, this study determined that the factors influencing residents’ all-age modification payment response could be summarized into three main categories: anxiety, objective perception, and external situation. To ensure the scientific validity and rationality of the theoretical model, an empirical research method utilizing structural equation modeling was employed. This involved formulating research hypotheses, designing questionnaires, and collecting and analyzing data to validate the model. Building upon the previously constructed all-age payment response mechanism model, five variables were identified—objective perception (OP), anxiety (AN), external situation (EC), willingness to pay (WTP), and government support (GS)—and eight research hypotheses were proposed. (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Hypothetical model of all-age payment response mechanism.

H1.

The objective perceptions of residents regarding community all-age transformation have a significant positive effect on their willingness to pay.

H2.

The objective perceptions of residents regarding community all-age transformation have a significant positive effect on their payment response.

H3.

The objective perceptions of residents regarding community all-age transformation have a significant inverse effect on their anxiety.

H4.

The anxiety experienced by residents in community all-age transformation has a significant inverse effect on their willingness to pay.

H5.

The external situation in which residents are placed during community all-age transformation has a significant inverse effect on their anxiety.

H6.

The external situation in which residents are placed during community all-age transformation has a significant positive effect on their willingness to pay.

H7.

The willingness of residents to pay in community all-age transformation has a significant positive effect on their behavioral response.

H8.

Government support plays a positive mediating role in the relationship between residents’ government intentions to payment response.

2.3.2. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

The questionnaire was designed using 10 latent variables, employing a scale based on theoretical categories. To ensure optimal reliability and validity, all indicators were carefully selected from established scales, with reactive and formative indicators revised for the two cost study components. Reactive indicators, such as group pressure, transformational trust, and government assistance, were utilized, while formative indicators, including perceived value, performance, economic cost, and risk, were incorporated. The Likert 7 subscale [42] was adopted, with response ratings ranging from 1 to 7, corresponding to “completely disagree” to “completely agree”. Higher scores indicated a greater level of agreement (Table 6).

Table 6.

Questionnaire on payment response mechanisms for residents in older neighborhoods.

To enhance data collection efficiency and the validity of the collected data, control measures were implemented in three key aspects: district sampling, targeted population selection for questionnaire distribution, and careful monitoring of the filling process. The MOHURD has initiated pilot urban regeneration projects in 21 cities (districts) that are highly representative and exemplify these pilot areas. Stratified sampling was employed [50], with the country divided into four regions: East, Central, West, and Northeast. A random sample of approximately 10% was drawn from each region, encompassing 21 cities, including Beijing, Nanjing, Xi’an, and Chengdu. This regional-based sampling approach helps overcome the issue of geographical concentration in sampling, resulting in improved sample representativeness, statistical data reliability, and enhanced external validity.

The questionnaires were distributed among middle-aged and older individuals residing in the neighborhood who required both aging care and childcare and possessed the financial capacity to pay. Prior to conducting the survey, participants were provided with a comprehensive briefing on the research objectives, questionnaire content, and instructions on how to effectively complete the questionnaire. Emphasis was placed on the individualized completion of the questionnaire to ensure authentic responses and minimize potential biases, such as social approval and expectancy effects, which could influence the questionnaire data.

A total of 340 questionnaires were distributed, resulting in the collection of 329 completed questionnaires through the employment of the instant return method, yielding a commendable return rate of 96.75%. Subsequently, after excluding 18 questionnaires containing incomplete responses resulting from objective factors, such as insufficient information pertaining to renovation, as well as 14 invalid questionnaires with noticeable patterns or errors, a final sample of 297 valid questionnaires remained, accounting for 90.27% of the initial distribution. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Demographic data of respondents (N = 297).

2.3.3. Measurement Model Testing

Reliability and validity were initially assessed in this study using different methods to test formative and reactive indicators. Reactive indicators involved a causal relationship between the measured items, with each item expected to exhibit internal consistency, interchangeability, and moderate to high correlation [51]. Conversely, formative indicators establish a causal relationship between item and indicator, meaning that removing any item can alter the potential index, and item correlations may become negative [52]. The reliability of reactivity indicators was empirically assessed through combined reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s coefficient (Cronbach’s alpha). Generally, values above 0.7 for Cronbach’s alpha and CR indicate high reliability and convergence effects. These criteria are accompanied by a standardized factor loading estimate (Std.) greater than 0.7 and an average variance extracted (AVE) above 0.5. Discriminant validity measurement requires that the AVE for each potential indicator surpass the square of the correlation (e) (Table 8). Similarly, differential validity measurement requires that the AVE for each potential indicator exceed the square of the correlation of each potential indicator (Table 9). To establish the validity of formative indicators, their reliability indicators are typically examined. Specifically, item weights should exceed 0.2, demonstrate significance, and exhibit t-values greater than 1.96. Additionally, because formative indicators exhibit negative regression, covariance should be assessed, ensuring a VIF below 5.

Table 8.

Index factor loading and average extraction variance.

Table 9.

Differential validity of measurement models.

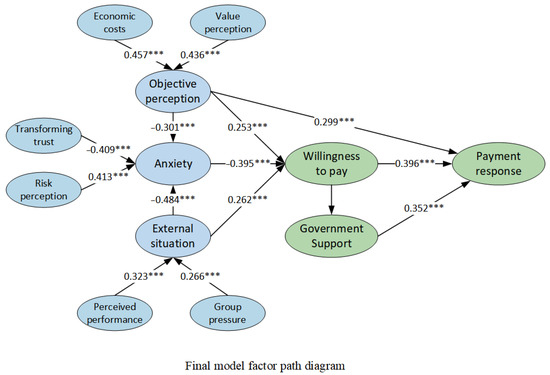

2.3.4. Structural Model Testing

The parameters were estimated using partial least squares, and the structural model was tested using Smart PLS 3.0 to perform path analysis [53]. The final model’s factor path diagram is depicted in Figure 4. The results of hypothesis testing are presented in Table 10. The model successfully passed the significance test at or below the 5% level, indicating the reliability of the theoretical model (Figure 4). In the context of all-age retrofitting in old neighborhoods, which encompasses anxiety, objective perceptions, and external situation, the payment response is influenced by the mediating variable of willingness to pay. Notably, anxiety exhibits the most substantial effect on willingness to pay. On the one hand, willingness to pay directly translates into payment response, while on the other hand, it indirectly affects payment response through government assistance. Moreover, residents’ objective perceptions significantly and positively impact behavioral responses. Therefore, residents’ payment behavior in the all-age transformation of old neighborhoods can be characterized as “spontaneous” (willingness to pay → payment response), “induced” (willingness to pay → government support → payment response), and “constrained” (objective perception → payment response), with the dominant behavioral logic being “spontaneous”.

Figure 4.

Final model factor path diagram. Note: “***” indicate significance at the 0.1% levels, respectively.

Table 10.

Hypothesis test results.

3. Conclusions

The interview text of 24 residents of old communities was deeply coded, and the influencing factors of residents’ payment response were refined, and a theoretical model was constructed based on this basis. The variables of willingness to pay were anxiety, objective perception, and external situation, and the variables of payment response were willingness to pay, objective perception, and government.

The empirical testing of the “Situation-Willingness-Response” model was conducted to explore its applicability to the payment response mechanisms of community residents. The findings demonstrated that objective perception, anxiety, and external situation exert a significant influence on residents’ willingness to pay. Notably, anxiety exhibited the most substantial effect, indicating that higher levels of anxiety are associated with decreased willingness to pay. Furthermore, objective perceptions, willingness to pay, and government assistance were found to have a significant positive impact on payment response. The dominant factor shaping residents’ payment behavior was their willingness to pay, while government support and objective perceptions displayed a similar effect.

The factor path diagram of the model demonstrates the significant positive correlation between objective perception and willingness to pay, indicating that an increase in perceived value and economic cost corresponds to a higher willingness to pay among individuals. Moreover, the inclusion of government assistance significantly improves payment behavior, suggesting that, in Chinese societies characterized by high levels of public trust, citizens’ behavioral decisions are primarily influenced by their organization-oriented perceptions of trust in government assistance rather than issue-oriented perceptions of event risk. The reliability of government assistance plays a crucial role in strengthening residents’ willingness to pay.

4. Discussion

4.1. Payment Behavioral Study

A comprehensive literature review of the current research shows that current research on the renovation of old residential areas focuses on renovation projects, policy recommendations, and visionary goals. However, there is a significant lack of research on residents’ willingness to participate in renovation programs and their payment behavior. The paper makes a substantial contribution to academic discourse by revealing the multifaceted determinants that influence the payment behavior of residents within the field of all-age renovation. By classifying key variables and building a robust theoretical model, the manuscript improves our understanding of how residents respond to the needs of community transformation. This knowledge has the potential to inform decision-making processes related to urban renewal and inspire further academic exploration in this area.

4.2. Recommendations

To elucidate the intricate relationship among multiple factors influencing residents and their payment response, this study develops a comprehensive model of the factors that shape payment response, drawing upon foundational theoretical frameworks. Specifically, the model incorporates anxiety as a psychological response indicator and government support as a component of interpersonal behavior theory, thereby enriching our understanding of residents’ payment response mechanisms in the context of all-age transformation. Additionally, it highlights the imperative of providing support during the all-age retrofitting process in older neighborhoods, aiming to improve residents’ payment response in the following aspects:

(1) Strengthen residents’ perception of the renovation value, alleviate their anxiety surrounding the renovation process, and foster a more spontaneous payment response. Residents should be effectively informed regarding the direct benefits they can derive from the renovations and emphasize the close link between renovation funding and the effectiveness of the renovation efforts. Simultaneously, the government should proactively employ methods such as household surveys, community visits, and internet opinion analysis to meticulously scrutinize residents’ discontent and grievances. Moreover, residents should be made aware of the pressing need to address the challenges posed by an aging population and the implementation of policies, such as the three-child policy, for family retirement and childcare. Specifically, it is essential to convey to residents that the deteriorating conditions and impractical layout planning of old neighborhoods are unsuitable for fulfilling the needs of aging care and childcare. Furthermore, the positive impact of all-age retrofitting on neighborhoods’ suitability for such purposes, along with highlighting how the implementation of renovations can alleviate anxiety, will be vital in garnering residents’ support and cooperation.

(2) Strengthen government support to improve the “inducibility” of payment response in all-age retrofitting. Given the positive effect of government assistance on payment response, it is recommended that the government streamline the ownership adjustment procedures, actively engage residents in the retrofitting process, facilitate knowledge sharing regarding neighborhood retrofitting accomplishments, and disseminate information about the retrofitting program. By prioritizing such measures, the government can effectively reduce the perceived difficulty in payment response, diminish anticipated risks, and provide residents with the necessary support and convenience to actively participate in the retrofitting process.

(3) Improving residents’ capacity for action in retrofitting endeavors and alleviating the “constraint” on their payment response. In the early stages of all-age retrofitting in older neighborhoods, the government can actively engage residents by mobilizing their enthusiasm and motivation to participate in the retrofitting process. A participatory approach can be adopted, whereby residents are invited to contribute their preferences and choices regarding the desired improvements. Moreover, collaboration between the government and neighborhood committees can establish a monitoring group responsible for overseeing renovation proposals. This inclusive approach empowers residents to deeply involve themselves in formulating renovation plans in the early stages, exercising control over the progress of the retrofitting process, and managing and maintaining renovated areas in the later stages. By fostering such resident involvement, the government facilitates greater ownership and agency among residents, thereby facilitating a more effective and less constrained payment response.

(4) Clearly delineate the distinctions between different age groups. Aging care focuses on the process of providing care and support for elderly individuals, aiming to promote their well-being and recovery. On the other hand, childcare is centered around nurturing and raising children with the objective of ensuring their successful development. Understanding and acknowledging the divergences between the two groups in terms of required efforts, service orientations, and willingness for development is crucial. By recognizing these differences and proposing appropriate solutions, it becomes possible to improve residents’ payment behavior.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the valuable insights gained from this study, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations that should be considered for future research. The study’s findings may be subject to biases because the interviewees and questionnaire respondents were mainly from older neighborhoods in China, which introduces the possibility of biased findings due to the specific national context. To address this limitation, future research should include residents from older neighborhoods in different countries to analyze the payment response mechanisms within their respective national contexts. Second, the analysis of the effects of demographic variables on the hypotheses presented in the paper did not discuss the impact of how demographic factors such as education level, age, and gender intersect with residents’ payment behavior and influence payment behavior in the context of full age modification. Additionally, collecting longitudinal data at multiple time points would allow for the exploration of the dynamic interaction between emotions and cognition as well as its impact on residents’ behavior. Lastly, it is important to note that this study focused on residents’ intentions rather than their actual payment behavior. As intentions and behaviors may differ [54], further research could examine the relationship between residents’ payment intentions and their actual payment behavior.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/bs13110925/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and L.D.; methodology, Y.Z. and L.D.; software, L.D.; validation, Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z. and L.D.; investigation, L.D.; resources, Y.Z.; data curation, L.D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and L.D.; supervision, Y.Z. and L.D.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the NSFC (51808424, 51677879, 51478384), The Ministry of education of Humanities and Social Science project (23YJCZH309); Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Provincial Department of Education (22JK0441).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research has low risk. And, the risk of the study subjects is not higher than those who did not participate in the study. After the evaluation by the ethical review from committee members, the exemption from review and verification is issued.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cobbold, C. A Cost Benefit Analysis of Lifetime Homes; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Trends and Countermeasures of Population Aging in China; Research Center on Aging: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L. Research on Design Strategy of Cultural Activity Center in Old Community under the Background of Urban Renewal. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Hou, J.; Xiao, P.; Che, N. Whole-age community planning based on the perspective of population aging. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2022, 22, 5381–5387. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P. Research on the reconstruction of China’s all-age community planning under the background of active aging. Mod. Urban Stud. 2018, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dian, Z.; Xu, Y. Planning and index control of residential space in urban community in aging society. Archit. J. 2014, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, Z.; Ouyang, X.; Tweed, C. Optimization of open space in old residential streets from the perspective of activity demand of the elderly. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9020–9028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, X.; Wei, W.; Jie, Z. Evaluation of residential space environment and planning strategies for elderly care in urban aging communities. Planner 2015, 31, 5–11+33. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Hu, X.; Shen, B. Abnormal analysis method of spatial behavior trajectory of the elderly in the community. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2021, 21, 3676–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Gu, Z. Planning and design of retirement communities under the background of aging. Planner 2015, 31, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Wei, G. Problems and countermeasures of aging-adapted renovation of outdoor environment in existing communities. Planner 2015, 31, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- To, K.; Chong, K.H. The traditional shopping street in Tokyo as a culturally sustainable and ageing-friendly community. J. Urban Des. 2017, 22, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D. Influencing Factors of Willingness to Pay for Age-Appropriate Renovation of Public Space in Old Residential Areas. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidert, C. Estimation of Willingness-to-Pay: Theory, Measurement, Application; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, C. Questionnaires, individual interviews and focus groups. In Research Methods: Information, Systems, and Contexts; Williamson, K., Johanson, G., Eds.; Tilde University Press: Prahran, Australia, 2013; pp. 379–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kazi, A.M.; Khalid, W. Questionnaire designing and validation. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2012, 62, 514. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Mary, L. Structured Questionnaire Limitations: A Systematic Review and Recommendations for Improvement. J. Surv. Res. 2020, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. Theoretical sampling. In Sociological Methods; Denzin, N.K., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, G. Research on influencing factors of reading promotion development in colleges and universities based on grounded theory. Libr. Inf. Work 2017, 61, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Johnson, L. In-Depth Interviews: A Methodological Review and Best Practice Recommendations. Qual. Res. J. 2023, 20, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Miller, S. A Grounded Theory Approach to Qualitative Data Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 20, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Rhemtulla, M.; Brosseau-Liard, P.É.; Savalei, V. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. The First Step in Grounded Theory: Open Coding. J. Qual. Health Res. 2021, 21, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam, A. Coding issues in grounded theory. Issues Educ. Res. 2006, 16, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Johnson, L. Thematic Content Analysis: Using Grounded Theory for Thematic Analysis. Qual. Res. J. 2022, 23, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, J. Axial coding and the grounded theory controversy. West. J. Nurs. Res. 1999, 21, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, M.; Mills, J.; Francis, K.; Chapman, Y. A thousand words paint a picture: The use of storyline in grounded theory research. J. Res. Nurs. 2009, 14, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.; Myrick, F. Grounded theory: An exploration of process and procedure. Qual. Health Res. 2006, 16, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triandis, H.C. Theoretical framework for evaluation of cross-cultural training effectiveness. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1977, 1, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, L. Trust: A Mechanism for Simplifying Social Complexity; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Johnson, L. Measuring Costs in Healthcare: A Critical Analysis of Current Practices. Healthc. Manag. Rev. 2021, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.; Kumar, R. The Impact of Customer Perceptions on Service Performance: A Study of Banking Industry. J. Serv. Res. 2021, 24, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.; Davis, K. The Nature and Impact of Group Pressure: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Organ. Behav. 2021, 42, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D. State-trait anxiety inventory for adults (STAI-AD). PsycTESTS Dataset 1983, 1, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugeland, J. Objective perception. In Perception; Akins, E., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 268–298. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.; Hancock, P.A. Situation awareness is adaptive, externally directed consciousness. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 1995, 37, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Johnson, L. The Role of Government Support in Promoting Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2021, 36, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Wang, J. Assessing the Direct Impact of Structural Equation Modeling on Organizational Performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 43, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, K.; Johnson, B. Using the Liket 7-Point Scale to Measure Job Satisfaction: An Examination of Its Validity and Reliability. J. Organ. Behav. 2021, 42, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Shim, J.P. Examining multi-dimensional trust and multi-faceted risk in initial acceptance of emerging technologies: An empirical study of mobile banking services. Decis. Support Syst. 2010, 49, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E.; Enis, B.M. Classifying products strategically. J. Mark. 1986, 50, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Courneya, K.S. Investigating multiple components of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived control: An examination of the theory of planned behaviour in the exercise domain. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 42, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultom, S.; Dalle, J.; Restu; Baharuddin; Hairudinoar; Gultom, S. The influence of attitude and subjective norm on citizen’s intention to use e-government services. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2020, 9, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, I.G. The test anxiety scale: Concept and research. In Stress and Anxiety; Spielberger, C.D., Sarason, I.G., Eds.; Hemisphere Publishing Corp: Washington, DC, USA, 1977; Volume 5, pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, K.M.W.; Manzo, W.R. The purpose and perception of learning objectives. J. Polit. Sci. Educ. 2018, 14, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of consumers’ green purchase behavior in a developing nation: Applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, J. Stratified Sampling: An Efficient Method for Data Collection. J. Surv. Stat. Methodol. 2021, 58, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z. Testing Reactivity and Formative Indicators in Structural Equation Modeling. J. Struct. Equ. Model. 2023, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, S. Smart PLS 3.0: Path Analysis of Structural Models. J. Struct. Equ. Model. 2023, 29, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predictiing Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).