Abstract

Given the significance of gut microbiota in autism spectrum disorder (ASD), we aimed to assess the quality of systematic reviews (SRs) of studies assessing gut microbiota and effects of probiotic supplementation in children with ASD. PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Medline, and Cochrane databases were searched from inception to November 2024. We included SRs of randomised or non-randomized studies reporting on gut microbiota or effects of probiotics in children with ASD. A total of 48 SRs (probiotics: 21, gut microbiota: 27) were included. The median (IQR) number of studies and participants was 7 (5) and 328 (362), respectively, for SRs of probiotic intervention studies and 18 (18) and 1083 (1201), respectively, for SRs of gut microbiota studies in children with ASD. The quality of included SRs was low (probiotics: 12, gut microbiota: 14) to critically low (probiotics: 9, gut microbiota: 13) due to lack of reporting of critical items including prior registration, deviation from protocol, and risk of bias assessment of included studies. Assuring robust methodology and reporting of future studies is important for generating robust evidence in this field.

1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by difficulties in social communication and interaction as well as the presence of restricted and repetitive behavior [1]. The global prevalence of ASD has increased markedly over the past four decades, with the most recent estimate reporting a global median prevalence of 100/10,000 (range: 1.09/10,000 to 436.0/10,000) [2]. In children born preterm, the risk of ASD is much higher and inversely proportional to their gestational age at birth [3]. Frontline therapies for ASD focus on behavioral and developmental approaches, which seek to support children to acquire key cognitive, language, and daily care skills. However, while these therapies are known to be effective to varying degrees in different children, the high co-occurrence of comorbid conditions, such as gut complaints, leads families to frequently try complementary and alternative approaches, such as dietary interventions, which have been found to have limited efficacy in clinical trials [4,5,6].

In recent years, there has been an increasing focus on the gut microbiome in the pathogenesis of autism considering its interactions and effects via the gut–brain axis. Probiotics, with their potential to correct dysbiosis and influence the gut–brain axis, offer a promising strategy to improve behavioral and social symptoms [7]. Given the plethora of randomized and non-randomized studies assessing gut microbiota and effects of probiotic supplementation in children with ASD, it is not surprising that many SRs have been reported in this field. SRs are at the apex of the pyramid of the hierarchy of evidence-based medicine and are considered important for guiding research and clinical practice and making important health policy decisions [8]. ASD is associated with significant health and socioeconomic burden [9,10]. Given the differences in the findings of systematic reviews of studies assessing gut microbiota and effects of probiotics in ASD, a critical assessment of the quality of the systematic reviews in this field is important. We hence aimed to conduct a critical review of systematic reviews of randomized and non-randomized studies assessing gut microbiota and effects of probiotics in children with ASD.

The aim of the current study was to assess the quality of SRs of studies assessing gut microbiome and effects of probiotic supplementation in children with ASD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods and Participants

A systematic review was conducted to assess the quality of SRs of studies assessing gut microbiota and effects of probiotic supplementation in children with ASD. The assessment of the quality of multiple SRs was conducted using an appropriate tool (AMSTAR-2) [11].

The protocol for this SR was registered on 21 November 2024 in the Open Science registry (No: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RB7VW).

2.2. Strategy for Literature Search

We conducted a literature search in July 2024 using PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Medline, and Cochrane databases from inception to July 2024. We used the following search strategy in PubMed, and similar search strategies were used in other databases: (probiotics) OR (lactobacillus)) OR (Bifidobacterium)) OR (Saccharomyces)) OR (gut microbiota)) OR (gut dysbiosis)) OR (gut microbiome)) OR (gut flora)) AND (((autism) OR (ASD)) OR (autistic)) Filters: Meta-Analysis, Systematic Review. Two reviewers (S.A. and CR) independently screened titles and abstracts from retrieved studies and subsequently full-text articles using predesigned criteria for eligibility. We screened the reference list of potentially relevant articles. Any disagreement between the investigators was resolved by consensus. There was no deviation in the protocol.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria: The Criteria for Including SRs in This Review

(1) SR (with or without meta-analysis) of studies (randomized controlled trials (RCT) or non-randomized (e.g., cohort, case–control) studies of intervention (NRSI) reporting on gut microbiota in children with ASD.

(2) SRs (with or without meta-analysis) of studies (RCTs or NRSIs) reporting the effects of probiotic supplementation (e.g., gut microbiota, behavior symptoms) in children with ASD.

(3) Full articles available.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Studies in animal models of ASD. (2) Studies involving intervention other than probiotics. (3) Studies where data could not be extracted.

2.4. Data Extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted data from each study in a prespecified data collection sheet. The following information was extracted: author name, year of publication, country of origin, type of review with meta-analysis or without, probiotic strain, dosage and schedule of probiotics, number of studies included, total number of participants, age range of participants, aims/objectives, and conclusions. If any study assessed various interventions or outcomes for multiple conditions, data relevant to probiotics or autism were entered where these data was unavailable, and then the combined data were recorded. Data were also added for the studies that used other interventions combined with probiotics.

2.5. Assessment of Risk of Bias (RoB)

Two independent authors assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the AMSTAR-2 tool. Discrepancies were resolved by group discussion with the third author. We recorded the answers to all 16 (critical: 9, non-critical: 7) domains. All answers were categorized as “yes” or “no” or “partial yes” or “no meta-analyses”. The studies were graded according to the AMSTAR-2 tool rules [11]. AMSTAR-2 is a critical appraisal tool for SRs of randomized or non-randomized studies of healthcare interventions. It is not intended to generate an overall score and includes a total of 16 items [11].

2.6. Domains and Rating

The AMSTAR-2 tool has seven critical domains (items Number 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15). The overall rating of the review is provided as high, moderate, low, or critical, depending upon the presence of critical or non-critical weaknesses. 1. High: No or one non-critical weakness: the SR provides an accurate and comprehensive summary of the results of available studies that address the question of interest. 2. Moderate: More than one non-critical weakness: the SR has more than one weakness but no critical flaws. It may provide an accurate summary of the results of the available studies included in the review. 3. Low: One critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses: the review has a critical flaw. It may not provide an accurate and comprehensive summary of the available studies that address the question of interest. 4. Critically low: More than one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses: the review has more than one critical flaw and should not be relied on to provide an accurate and comprehensive summary of the available studies.

2.7. Interrater Reliability of AMSTAR-2

Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ scores) is used to measure how well two or more people agree when rating something. Values range from −1 to 1, where 1 indicates complete agreement and 0 signifies no agreement. The inter-rater reliability (κ scores) in the AMSTAR tool was a mean of 0.70 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.57, 0.83) (range: 0.38–1.0) across all the domains. Three pairs of raters provided values between 46 and 50 κ scores.

3. Results

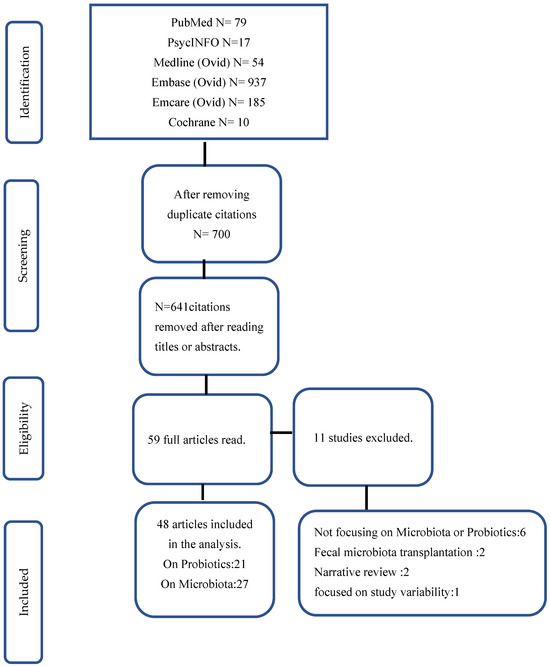

The PRISMA flow chart for study selection is shown in Figure 1. A total of 1285 SRs were identified on search from databases. Duplicate records (n = 585) were removed using endnote. From the remaining 700 citations, 641 were removed after reading the titles and abstract. Forty-eight articles were included in the analyses after reading the full articles. A total of 21 of the included reviews reported outcomes associated with probiotics intervention, and 27 reported outcomes based on microbiota composition. The following articles were excluded [4,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

3.1. Systematic Reviews: Studies Assessing the Effects of Probiotic Supplementation in Children with ASD

A total of 6 of the included 21 systematic reviews (SRs) focused on RCTs [21,22,23,24,25,26], while 15 included both RCTs and NRSIs [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Eleven SRs examined studies assessed probiotics alongside other interventions for ASD [21,22,23,27,28,29,30,33,36,37,39]. Two SR included studies that reported on psychological conditions in conjunction with ASD [23,40].

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies on probiotic interventions. The median (IQR) number of studies included in each SR was 7 (5), with a median (IQR) of 328.5 (362) participants per review. The age of participants across the SRs ranged from 0 to 60 years. Some of the SRs included participants beyond the age of 18 years [26,27,29,40,41].

Table 1.

Characteristics of included systematic reviews of studies assessing effects of probiotics in children with autism.

Out of the 21 included SRs, 15 concluded that there was either no improvement in ASD symptoms or noted a lack of high-quality evidence to draw any definitive conclusions [21,22,23,24,26,28,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,41]. A total of 7 of the included 21 SRs conducted a meta-analysis. Six reported no significant improvement in behavioral symptoms associated with ASD [21,22,24,26,34,39]. One of these reviewed a significant improvement in gastrointestinal but not behavioral symptoms associated with ASD [24]. One meta-analysis showed improvement in behavioral symptoms [25]. The methodological quality of all included SRs was rated as low to critically low (Table 2). Individual domain outcomes are reported in Table 3.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment in studies assessing effects of probiotic supplementation.

Table 3.

AMSTAR-2 domains in studies of probiotic supplementation.

3.2. Systematic Reviews: Studies Assessing Fecal Microbiota in Children with ASD

Of the 27 SRs (Table 4), 15 that included only NRSIs reported an association of ASD outcomes with fecal microbiota (surrogate of gut microbiota) composition [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. A total of 12 SRs included NRSIs as well as RCTs [57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. The quality of the included SRs assessed by the AMSTAR-2 tool is shown in Table 5. Individual domain outcomes are shown in Table 6. The median (IQR) number of studies included in the SRs was 18 (18), with a median (IQR) of 1083 (1201.75) participants per review. The age of participants in the included reviews ranged from 0 to 60 years. Some of the studies included participants beyond 18 years of age [54,56,69]. A total of 7 out of the 27 studies conducted meta-analysis [43,44,45,51,52,56,58]. Studies assessing fecal microbiota in children with ASD that were included in the SRs reported variable results. Out of 27 SRs, findings of 12 were inconclusive on the role of gut microbiota [42,43,44,55,57,59,60,61,62,64,67,68]. Only three SRs, including one with meta-analysis, suggested that fecal microbiota improved ASD symptoms [47,58,63].

Table 4.

Characteristics of included systematic reviews of studies assessing gut microbiota in children with autism.

Table 5.

Risk of bias assessment in studies assessing gut microbiota.

Table 6.

AMSTAR-2 domain outcomes in studies of gut microbiota.

Overall, the quality of SRs of studies reporting on gut microbiota in children with ASD and those assessing the effect of probiotics in this population was downgraded mainly due to the lack of reporting of critical items including prior registration, deviation from protocol, RoB assessment of included studies, and details of excluded studies.

4. Discussion

Our review identified 21 SRs (total participants: 5418) reporting on the effect of probiotic supplementation in children with ASD and a further 27 SRs (total participants: 21445) reporting on studies assessing gut microbiota in this population. Overall, the methodological quality of all included SRs, assessed using the AMSTAR-2 tool, was rated as low to critically low. The main reasons for downgrading the quality of included SRs included the lack of reporting of critical items (e.g., prior registration, details of excluded studies, RoB assessment of included studies) and deviation from protocol.

Further key findings emerged from the review of SRs reporting on fecal microbiota of children with ASD. Recent literature suggests that children with ASD have dysbiosis compared to healthy children [69]. The fecal microbiota profile in these children is known to vary from region to region. The common findings include an increase in clostridium species (e.g., Clostridium bolteae and botulinum), Bacillus spp. and Enterobacteria, reduction in genera Prevotella and Roseburia, and increase in fungal species (e.g., Candida, Saccharomyces). With dysbiosis, there are also changes in amino acids, lipids, and carbohydrate metabolism in gut microbiota. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota related to an overgrowth of pathogenic microbes leads to increased gut permeability, which impairs the integrity of the blood–brain barrier. This allows peripheral neurotoxic proteins or microbial metabolites to enter the brain, leading to neuronal damage or neuroinflammation [69]. A recent SR that included 18 studies (participants: 493 ASD and 404 controls) showed an increase in genera Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, Clostridium, Fecalibacterium and Phascolarctobacterium and a lower percentage of Coprococcus and Bifidobacterium in children with ASD. It is postulated that such dysbiosis may explain the behavioral and gastrointestinal symptoms in ASD, mediated via the immune and inflammatory pathways through the gut–brain axis [58]. Levkova et al. reported significantly different bacterial species in children with ASD compared with controls. These included Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Clostridium, Coprococcus, Fecalibacterium, Lachnospira, Prevotella, Ruminococcus, Streptococcus, and Blautia. The variation in fecal microbiota composition in children with ASD may relate to dietary variations, eating habits, lifestyles, and genetic and environmental influences in this cohort [49,70]. Others report that these variations can also relate to the small sample sizes in such studies apart from the variations in dietary practices, and a high prevalence of functional gastrointestinal symptoms in this population [46].

Similar to the variation in findings observed in the SRs of fecal microbiota, the effects of probiotic supplementation on children with ASD show significant heterogeneity across SRs. The effects of probiotics have been studied in various psychiatric disorders, primarily due to their potential for exerting both local and systemic effects. Locally, probiotics can correct dysbiosis, enhance the gut barrier to prevent or minimize intestinal permeability, reduce inflammation, and modulate neuroendocrine functions. Systemically, they may ameliorate symptoms of ASD by influencing signalling pathways via the gut–brain axis [71]. However, the findings regarding the efficacy of probiotics in children with ASD have been inconsistent. The study by Barba-Vila et al. suggested that probiotics might improve behavioral outcomes and gut microbiota profiles in this population. However, they suggested a note of caution in interpreting their results given the significant methodological limitations across studies. Similarly, a meta-analysis reported by Xiao et al. that included seven clinical trials reported limited efficacy of probiotics in enhancing behavioral symptoms in children with ASD. The authors cautioned against overinterpreting these findings considering the heterogeneity in probiotic strains, duration of supplementation, and other methodological issues in the included studies [34].

A recent meta-analysis by Soleimanpour et al. (eight RCTs, 318 patients with ASD, age: 1.5 to 20 years) showed that the probiotic group had significantly better behavioral symptoms compared to the control group [pooled standardized mean difference (SMD): −0.38 (95% CI: 0.58 to −0.18), p < 0.01]. Subgroup analyses involving studies conducted in the European region, those with an intervention period > 3 months, and those focusing on participants under and >10 years of age showed significant benefits. Furthermore, multi-strain [SMD: −0.53 (95%CI: 0.85 to −0.22)] as well as single-strain [SMD: −0.28 (95%CI: 0.54 to −0.02)] probiotics showed significant improvement in behavioral symptoms. The low probability of publication bias supported the validity of the core findings [25].

Understanding the development and evolution of the AMSTAR tool is important before discussing its limitations. First developed by Shea and colleagues in 2007 [72], the AMSTAART tool was created for comprehensive assessment of the methodological quality of SRs of RCTs. The tool, which included 11 items in a questionnaire with options to answer “yes”, “no”, “can’t answer”, or “not applicable”, was not meant for quantitative scoring [72]. Despite the evidence supporting its reliability and validity [73], AMSTAR was criticized for various reasons. These included whether it truly assesses the methodological quality of a SR, its relative lack of adequate guidance and detailed description of publication bias, and difficulty in interpreting some items [74,75]. Introduced in 2010, the revised AMSTAR (R-AMSTAR) used a scoring approach based on domain weight to quantify the quality of a SR [76]. Popovich et al. compared AMSTAR and R-AMSTAR tools for assessment of randomly selected 60 SRs (Cochrane: 30, non-Cochrane: 30) in the field of assisted reproduction. The reviews were graded and ranked based on results converted into percentage scores. The percentage scores showed wider variation and achieved higher inter-rater reliability by AMSTAR vs. R-AMSTAR assessment. The average rating was consistent between the tools (R-AMSTAR: 88.3% vs. AMSTAR: 83.6%) for Cochrane reviews but inconsistent for non-Cochrane reviews (R-AMSTAR: 63.9% vs. AMSTAR: 38.5%). Overall, the Cochrane reviews changed an average of 4.2 places compared to 2.9 for non-Cochrane in the rankings generated between the two tools. The authors concluded that R-AMSTAR provided more excellent guidance in the assessing domains and produced quantitative results. However, AMSTAR was much easier for consistency in application than R-AMSTAR. They recommended incorporating their findings in AMSTAR and additional guidance for its application to improve its reliability and usefulness [77]. AMSTAR-2, the current version of the tool, was developed after extensive revision of the original tool. It includes ten of the original items and six additional items for appraisal of RCTs and non-RCTs. The overall rating is based on weaknesses in critical domains and provides comprehensive guidance for using the tool [11].

The limitations of AMSTAR-2 have been reported by various investigators. Li et al. reported on an AMSTAR 2-based quality assessment of SRs with meta-analysis related to heart failure. A total of 79 of the 81 included SRs were “critically low-quality”. The remaining two were of “low quality.” These findings were attributed to insufficient a priori protocols (compliance rate: 5%), complete list of exclusions with justification (5%), risk of bias assessment (69%), meta-analysis methodology (78%), and investigation of publication bias (60%). The authors concluded that the low rating for these potential high-quality SRs questions the discrimination capacity of AMSTAR 2. They emphasized the need to identify insufficiency areas in the AMSTAR-2 tool and justify or modify its rating rules [78]. Puljak et al. assessed the applicability of AMSTAR-2 to a total of 80 SRs of non-intervention studies in a meta-research study. They used SRs (20 each) for the following four types: diagnostic test accuracy reviews, etiology and/or risk reviews, prevalence and/or incidence reviews, and prognostic reviews. Three authors applied AMSTAR-2 independently to each of the included SRs. They then assessed the applicability of each item to that SRs type and “any SR” type. Their results unanimously showed that 7 of 16 AMSTAR-2 items were applicable for all 4 specific SR types and any SRs (Items 2, 5, 6, 7, 10, 14 and 16), but 8 of 16 items were for any SR type. These items could cover generic SR methods that do not depend on a specific SR type. They concluded that AMSTAR-2 is only partially applicable for non-intervention SRs and emphasized the need to adapt or extend AMSTAR-2 for SR of non-intervention studies [79].

The findings of our umbrella review show the difficulties in deriving robust conclusions from available systematic reviews for guiding research and clinical practice in the field. Current evidence does not help in guiding selection of participants (age at diagnosis, severity of ASD, baseline gut microbiota) or the intervention (e.g., probiotic strain/s, dose, duration). The only finding that is common to all studies in this field is that children with ASD have dysbiosis and probiotic supplementation has the potential to modulate the gut microbiota for host benefits. Interpreting the significance of our results in the context of evidence-based medicine is essential. Well-designed and adequately powered RCTs are considered as the gold standard of clinical research to assess what works and what does not [80]. SRs of RCTs, or non-RCTs as the second-best choice under some circumstances, are at the apex of the pyramid of the hierarchy in evidence-based medicine. Experts advocate that every clinical trial should begin or at least end with a SR [81]. The significance of the quality of SRs cannot be overemphasized for guiding research and clinical practice and making informed health policy decisions. Given the enormous health burden of the underlying health issue and the potential benefits of the proposed intervention, it is important that the design, conduct, and reporting of RCTs and non-RCTs of probiotics to improve the outcomes in young children with ASD needs to be robust. This ensures that the SRs of RCTs and non-RCTs in this field is of high quality. Both the limitations of quality assessment tools such as AMSTAR, as discussed above, and the responsibilities of the investigators in assuring robust design, conduct, and reporting of their RCTs or non-RCTs are critical issues. Conducting adequately powered, well-designed large RCTs to detect small but clinically meaningful effects to improve the outcomes of the participants is challenging, mainly when the participants include community-based children with ASD. Hence, it will not be surprising if the trend towards conducting small studies of probiotics for children with ASD continues. Conducting SRs of small studies will continue to be the accepted approach to generate evidence with more power and precision. However, if information on critical domains of assessment tools such as AMSTAR continues to be missing for various reasons, the quality of SRs of such studies will continue to be low. The current SR adds meaningful data to guide further research in the field of gut microbiota in children with ASD and the potential of probiotics as an intervention for the condition.

5. Conclusions

The quality of SRs evaluating gut microbiota and effects of probiotics in children (and in few SRs, adults) with ASD is low to critically low. Robust methodology for designing, conducting, and reporting future clinical studies and their SRs is critical for generating robust evidence to guide research and clinical practice in this field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P. and S.A.; methodology, S.P. and S.A.; software, S.A. and C.R.; validation, S.P., S.A. and C.R.; formal analysis, S.A.; investigation and resources, S.A. and C.R.; data curation, S.A. and C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A. and C.R.; writing—review and editing, A.W., S.P. and S.R.; visualization A.W., S.A., S.P. and S.R.; supervision A.W., S.P. and S.R.; project administration, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lai, M.C.; Lombardo, M.V.; Baron-Cohen, S. Autism. Lancet 2014, 383, 896–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidan, J.; Fombonne, E.; Scorah, J.; Ibrahim, A.; Durkin, M.S.; Saxena, S.; Yusuf, A.; Shih, A.; Elsabbagh, M. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, S.; Rao, S.C.; Bulsara, M.K.; Patole, S.K. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Preterm Infants: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20180134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, X.; Fu, J.; Wang, X.; Pu, L.; Gu, C.; Cai, C. Efficacy and Safety of Diet Therapies in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 844117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Xu, X.; Cui, Y.; Han, H.; Hendren, R.L.; Zhao, L.; You, X. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the benefits of a gluten-free diet and/or casein-free diet for children with autism spectrum disorder. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathe, N.; Andrews, J.C.; McPheeters, M.L.; Warren, Z.E. Nutritional and Dietary Interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20170346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, E. A review of probiotics in the treatment of autism spectrum disorders: Perspectives from the gut–brain axis. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1123462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bero, L.A.; Jadad, A.R. How consumers and policymakers can use systematic reviews for decision making. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997, 127, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, T.A.; Weinstein, M.C.; Newhouse, J.P.; Munir, K.; Kuhlthau, K.A.; Prosser, L.A. Economic burden of childhood autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e520–e529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matin, B.K.; Byford, S.; Soltani, S.; Kazemi-Karyani, A.; Atafar, Z.; Zereshki, E.; Soofi, M.; Rezaei, S.; Rakhshan, S.T.; Jahangiri, P. Contributing factors to healthcare costs in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, A.S. The role of nutraceuticals in the management of autism. Saudi Pharm. J. 2013, 21, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinna Meyyappan, A.; Forth, E.; Wallace, C.J.K.; Milev, R. Effect of fecal microbiota transplant on symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fond, G.; Boukouaci, W.; Chevalier, G.; Regnault, A.; Eberl, G.; Hamdani, N.; Dickerson, F.; Macgregor, A.; Boyer, L.; Dargel, A.; et al. The “psychomicrobiotic”: Targeting microbiota in major psychiatric disorders: A systematic review. Pathol. Biol. 2015, 63, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancheva, R.; Chamova, R.; Marinov, D.; Toneva, A.; Dzhogova, M.; Eyubova, S.; Usheva, N. Therapeutic diets and supplementation: Exploring their impact on autism spectrum disorders in childhood—A narrative review of recent clinical trials. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2024, 112, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, G.; Wan, L.; Liang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yan, H.; Zhang, B.; Yang, G. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1123658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persico, A.M.; Asta, L.; Chehbani, F.; Mirabelli, S.; Parlatini, V.; Cortese, S.; Arango, C.; Vitiello, B. The pediatric psychopharmacology of autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review part II: The future. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2024, 136, 111176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarezadeh, M.; Mahmoudinezhad, M.; Hosseini, B.; Khorraminezhad, L.; Razaghi, M.; Alvandi, E.; Saedisomeolia, A. Dietary pattern in autism increases the need for probiotic supplementation: A comprehensive narrative and systematic review on oxidative stress hypothesis. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1330–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzatello, P.; Novelli, R.; Montemagni, C.; Rocca, P.; Bellino, S. Nutraceuticals in Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhari, A.; Azizan, F.; Esposito, G. A systematic review of gut-immune-brain mechanisms in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Dev. Psychobiol. 2019, 61, 752–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Zhang, M.; Teng, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L. Prebiotics and probiotics for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 71, 001510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siafis, S.; Çıray, O.; Wu, H.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Bighelli, I.; Krause, M.; Rodolico, A.; Ceraso, A.; Deste, G.; Huhn, M.; et al. Pharmacological and dietary-supplement treatments for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Mol. Autism 2022, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, R.S.D.; Vieira-Coelho, M.A. Probiotics and prebiotics: Focus on psychiatric disorders—A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, P.; Zhang, C.Z.; Fan, Z.X.; Yang, C.J.; Cai, W.Y.; Huang, Y.F.; Xiang, Z.J.; Wu, J.Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J. Effect of probiotics on children with autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2024, 50, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimanpour, S.; Abavisani, M.; Khoshrou, A.; Sahebkar, A. Probiotics for autism spectrum disorder: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of effects on symptoms. J. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 179, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowska, M.; Kołodziej, M.; Szajewska, H.; Łukasik, J. The impact of probiotics on core autism symptoms-a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 63, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi, C.N.; Orish, C.N.; Frazzoli, C.; Orisakwe, O.E. Dietary interventions for autism spectrum disorder: An updated systematic review of human studies. Psychiatriki 2022, 33, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Vargas, D.; Leonario Rodriguez, M. Effectiveness of nutritional interventions on behavioral symptomatology of autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Nutr. Hosp. 2022, 39, 1378–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Mishra, D.; Eshraghi, R.S.; Mittal, J.; Sinha, R.; Bulut, E.; Mittal, R.; Eshraghi, A.A. Altering the gut microbiome to potentially modulate behavioral manifestations in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 128, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Fu, X.; Liao, X.; Li, Y. Effects of gut microbial-based treatments on gut microbiota, behavioral symptoms, and gastrointestinal symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Atluri, L.M.; Gonzalez, N.A.; Sakhamuri, N.; Athiyaman, S.; Randhi, B.; Gutlapalli, S.D.; Pu, J.; Zaidi, M.F.; Khan, S. A Systematic Review of Mixed Studies Exploring the Effects of Probiotics on Gut-Microbiome to Modulate Therapy in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Cureus 2022, 14, e32313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvares, M.A.; Serra, M.J.R.; Delgado, I.; Carvalho, J.C.; Sotine, T.C.C.; Ali, Y.A.; Oliveira, M.R.M.; Rullo, V.E.V. Use of probiotics in pediatric patients with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2021, 67, 1503–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Q.X.; Loke, W.; Venkatanarayanan, N.; Lim, D.Y.; Soh, A.Y.S.; Yeo, W.S. A Systematic Review of the Role of Prebiotics and Probiotics in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Medicina 2019, 55, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, W.; Tang, F.; Chen, X.; Song, G. Effects of Probiotics on Autism Spectrum Disorder in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patusco, R.; Ziegler, J. Role of Probiotics in Managing Gastrointestinal Dysfunction in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Update for Practitioners. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Orsso, C.E.; Deehan, E.C.; Kung, J.Y.; Tun, H.M.; Wine, E.; Madsen, K.L.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Haqq, A.M. Probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of behavioral symptoms of autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Autism Res. Off. J. Int. Soc. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 1820–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosperi, M.; Santocchi, E.; Guiducci, L.; Frinzi, J.; Morales, M.A.; Tancredi, R.; Muratori, F.; Calderoni, S. Interventions on Microbiota: Where Do We Stand on a Gut-Brain Link in Autism? A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Vila, O.; García-Mieres, H.; Ramos, B. Probiotics in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review of clinical studies and future directions. Nutr. Rev. 2024, 83, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, F.; Toguzbaeva, K.; Qasim, N.H.; Dzhusupov, K.O.; Zhumagaliuly, A.; Khozhamkul, R. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics for patients with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis and umbrella review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1294089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, K.; Budzyńska, A.; Wiktorczyk-Kapischke, N.; Chomacka, K.; Grudlewska-Buda, K.; Wilk, M.; Wałecka-Zacharska, E.; Andrzejewska, M.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E. The role of psychobiotics in supporting the treatment of disturbances in the functioning of the nervous system—A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wan, G.B.; Huang, M.S.; Agyapong, G.; Zou, T.L.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, Y.W.; Song, Y.Q.; Tsai, Y.C.; Kong, X.J. Probiotic Therapy for Treating Behavioral and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Curr. Med. Sci. 2019, 39, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Lin, P.; Jiang, P.; Li, C. Characteristics of the gastrointestinal microbiome in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2013, 25, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Xu, X.; Li, J.; Li, F. Association Between Gut Microbiota and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, K.A.; Yin, X.; Rutherford, E.M.; Wee, B.; Choi, J.; Chrisman, B.S.; Dunlap, K.L.; Hannibal, R.L.; Hartono, W.; Lin, M.; et al. Multi-angle meta-analysis of the gut microbiome in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A step toward understanding patient subgroups. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, H.; Lu, W.; Zhai, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, W.; Gu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Potential of gut microbiome for detection of autism spectrum disorder. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 149, 104568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputi, V.; Hill, L.; Figueiredo, M.; Popov, J.; Hartung, E.; Margolis, K.G.; Baskaran, K.; Joharapurkar, P.; Moshkovich, M.; Pai, N. Functional contribution of the intestinal microbiome in autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and Rett syndrome: A systematic review of pediatric and adult studies. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1341656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, J.; Wu, F.; Zheng, H.; Peng, Q.; Zhou, H. Altered composition and function of intestinal microbiota in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnechere, B.; Amin, N.; Van Duijn, C. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Neuropsychiatric Diseases—Creation of An Atlas-Based on Quantified Evidence. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 831666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkova, M.; Chervenkov, T.; Pancheva, R. Genus-Level Analysis of Gut Microbiota in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Mini Review. Children 2023, 10, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundgaard-Nielsen, C.; Knudsen, J.; Leutscher, P.D.C.; Lauritsen, M.B.; Nyegaard, M.; Hagstrøm, S.; Sørensen, S. Gut microbiota profiles of autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic literature review. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 1172–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J. Perturbations of Gut Microbiota Compositions in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review and Meta-analysis. Preprints 2023, 2023051435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, J.; Li, Q.; Li, D.; Zhu, M.; Fu, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, M.; Lou, X.; et al. A comparison between children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and healthy controls in biomedical factors, trace elements, and microbiota biomarkers: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1318637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.-L.; Abbaspour, A.; Mkoma, G.F.; Bulik, C.M.; Rück, C.; Djurfeldt, D. Gut Microbiota in Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review. Psychosom. Med. 2021, 83, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grau-Del Valle, C.; Fernández, J.; Solá, E.; Montoya-Castilla, I.; Morillas, C.; Bañuls, C. Association between gut microbiota and psychiatric disorders: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1215674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurek, L.; Sevil, M.; Jay, A.; Schröder, C.; Baghdadli, A.; Héry-Arnaud, G.; Geoffray, M.-M. Is there a dysbiosis in individuals with a neurodevelopmental disorder compared to controls over the course of development? A systematic review. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 30, 1671–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreo-Martínez, P.; Rubio-Aparicio, M.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Veas, A.; Martínez-González, A.E. A Meta-analysis of Gut Microbiota in Children with Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 1374–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezawada, N.; Phang, T.H.; Hold, G.L.; Hansen, R. Autism Spectrum Disorder and the Gut Microbiota in Children: A Systematic Review. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 76, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Vázquez, L.; Van Ginkel Riba, G.; Arija, V.; Canals, J. Composition of Gut Microbiota in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligezka, A.N.; Sonmez, A.I.; Corral-Frias, M.P.; Golebiowski, R.; Lynch, B.; Croarkin, P.E.; Romanowicz, M. A systematic review of microbiome changes and impact of probiotic supplementation in children and adolescents with neuropsychiatric disorders. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 108, 110187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska-Pietruszka, Z.; Figlerowicz, M.; Mazur-Melewska, K. Microbiota in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, A.E.; Andreo-Martínez, P. Prebiotics, probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation in autism: A systematic review. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2020, 13, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikantha, P.; Mohajeri, M.H. The Possible Role of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain-Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, U.; Habib, H. The Link Between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Gastrointestinal Microbiota. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2021, 33, 513–518. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, L.K.H.; Tong, V.J.W.; Syn, N.; Nagarajan, N.; Tham, E.H.; Tay, S.K.; Shorey, S.; Tambyah, P.A.; Law, E.C.N. Gut microbiota changes in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Gut Pathog. 2020, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korteniemi, J.; Karlsson, L.; Aatsinki, A. Systematic review: Autism spectrum disorder and the gut microbiota. Acta Psychiatry Scand. 2023, 148, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, A.; Deonandan, R.; Konkle, A.T. The link between autism spectrum disorder and gut microbiota: A scoping review. Autism 2020, 24, 1328–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasheras, I.; Gracia-García, P.; Santabárbara, J. Modulation of gut microbiota in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2021, 35, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoudi, M.U.; Hosie, S.; Shindler, A.E.; Wood, J.L.; Franks, A.E.; Hill-Yardin, E.L. Comparing the Gut Microbiome in Autism and Preclinical Models: A Systematic Review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 905841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Su, Q.; Ng, S.C. New insights on gut microbiome and autism. Trends Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 1100–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.X.; Henders, A.K.; Alvares, G.A.; Wood, D.L.A.; Krause, L.; Tyson, G.W.; Restuadi, R.; Wallace, L.; McLaren, T.; Hansell, N.K.; et al. Autism-related dietary preferences mediate autism-gut microbiome associations. Cell 2021, 184, 5916–5931.e5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, B.; McVeigh, C.; Bendriss, G.; Chaari, A. The Promising Role of Probiotics in Managing the Altered Gut in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, B.J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Wells, G.A.; Boers, M.; Andersson, N.; Hamel, C.; Porter, A.C.; Tugwell, P.; Moher, D.; Bouter, L.M. Development of AMSTAR: A measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, R.C.; Matthias, K.; Pieper, D.; Wegewitz, U.; Morche, J.; Nocon, M.; Rissling, O.; Schirm, J.; Jacobs, A. A psychometric study found AMSTAR 2 to be a valid and moderately reliable appraisal tool. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 114, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faggion, C.M., Jr. Critical appraisal of AMSTAR: Challenges, limitations, and potential solutions from the perspective of an assessor. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burda, B.U.; Holmer, H.K.; Norris, S.L. Limitations of A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) and suggestions for improvement. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, J.; Chiappelli, F.; Cajulis, O.O.; Avezova, R.; Kossan, G.; Chew, L.; Maida, C.A. From Systematic Reviews to Clinical Recommendations for Evidence-Based Health Care: Validation of Revised Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (R-AMSTAR) for Grading of Clinical Relevance. Open Dent. J. 2010, 4, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovich, I.; Windsor, B.; Jordan, V.; Showell, M.; Shea, B.; Farquhar, C.M. Methodological quality of systematic reviews in subfertility: A comparison of two different approaches. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Asemota, I.; Liu, B.; Gomez-Valencia, J.; Lin, L.; Arif, A.W.; Siddiqi, T.J.; Usman, M.S. AMSTAR 2 appraisal of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the field of heart failure from high-impact journals. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puljak, L.; Bala, M.M.; Mathes, T.; Poklepovic Pericic, T.; Wegewitz, U.; Faggion, C.M., Jr.; Matthias, K.; Storman, D.; Zajac, J.; Rombey, T.; et al. AMSTAR 2 is only partially applicable to systematic reviews of non-intervention studies: A meta-research study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2023, 163, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariton, E.; Locascio, J.J. Randomised controlled trials—The gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: Randomised controlled trials. BJOG 2018, 125, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.; Hopewell, S.; Chalmers, I. Reports of clinical trials should begin and end with up-to-date systematic reviews of other relevant evidence: A status report. J. R. Soc. Med. 2007, 100, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).