Abstract

Background: Gram-negative bacteria are causative agents of endogenous endophthalmitis (EBE). We aim to systematically review the current literature to assess the aetiologies, risk factors, and early ocular lesions in cases of Gram-negative EBE. Methods: All peer-reviewed articles between January 2002 and August 2022 regarding Gram-negative EBE were included. We conducted a literature search on PubMed and Cochrane Controlled Trials. Results: A total of 115 studies and 591 patients were included, prevalently Asian (98; 81.7%) and male (302; 62.9%). The most common comorbidity was diabetes (231; 55%). The main aetiologies were Klebsiella pneumoniae (510; 66.1%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (111; 14.4%), and Escherichia coli (60; 7.8%). Liver abscesses (266; 54.5%) were the predominant source of infection. The most frequent ocular lesions were vitreal opacity (134; 49.6%) and hypopyon (95; 35.2%). Ceftriaxone (76; 30.9%), fluoroquinolones (14; 14.4%), and ceftazidime (213; 78.0%) were the most widely used as systemic, topical, and intravitreal anti-Gram-negative agents, respectively. The most reported surgical approaches were vitrectomy (130; 24.1%) and evisceration/exenteration (60; 11.1%). Frequently, visual acuity at discharge was no light perception (301; 55.2%). Conclusions: Gram-negative EBEs are associated with poor outcomes. Our systematic review is mainly based on case reports and case series with significant heterogeneity. The main strength is the large sample spanning over 20 years. Our findings underscore the importance of considering ocular involvement in Gram-negative infections.

1. Introduction

Endogenous endophthalmitis (EE) is a rare but devastating complication of bloodstream infections found in less than 0.5% of patients with fungemia and 0.04% of patients with bacteraemia [1]. When left untreated, endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis (EBE) can damage the eye’s structures, leading to visual impairment and even blindness [2]. From any possible source of infection, the aetiological agent may spread through the bloodstream across the blood–retinal barrier (BRB), eventually reaching the eye structures [2]. Nearly 10% of EBE worldwide are caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), which is also the leading cause of EBE in the USA and Europe, comprising approximately 25% of these cases [3].

S. aureus itself can alter BRB tight junctions by disrupting the expression and/or organisation of the ZO-1 protein [4]. In other words, S. aureus possesses the ability to cause EBE regardless of pre-existing vascular leakage [5]. However, other bacteria are involved in the aetiology of EBE: Streptococcus spp. (including viridans group, S. pneumoniae, Streptococcus milleri group and group A and B streptococci), and Gram-negative pathogens such as Escherichia coli and especially Klebsiella pneumoniae represent important causes of EE [1]. A higher rate of endophthalmitis has been reported in patients with hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKp) bacteraemia associated with liver abscesses and prostate involvement [6]. Unlike S. aureus, no intrinsic pathogenic activity has been demonstrated for these bacteria. However, predisposing conditions that might cause damage to the BRB do exist. Diabetes mellitus ranks highest among the comorbidities related to EBE. It is associated with 33% of cases and causes significant permeability alterations in the BRB [4]. Studies in animal models have suggested that an increased BRB permeability could contribute to an increment in bacterial transmigration from the bloodstream into the eye [5].

It is uncertain whether it is necessary to conduct ocular screening for Gram-negative EBEs in day-by-day clinical practice. Literature on EBE consists mostly of case series or single case reports and only a few analyses on humans investigate risk factors for BRB alteration in cases of ocular involvement secondary to Gram-negative bloodstream infections [2]. Lastly, several primary focal ocular lesions might break into and seed the vitreous causing EBE, but these pathogenetic aspects are not well defined, especially for Gram-negative bacteria [7,8,9]. Our primary aim is to systematically review the current literature to properly assess the risk factors, main aetiologies, and early ocular lesions in case of EBE due to Gram-negative bacteria.

2. Methods

Our methods meet the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) updated guideline for systematic review stated in 2020 [10].

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

All articles published in peer-reviewed medical journals between January 2002 and August 2022 regarding EBE during Gram-negative infection were included. We excluded articles regarding non-bacterial EE or EE secondary to Gram-positive infection papers in which data regarding EBE due to a Gram-negative infection were available but impossible to extrapolate. Articles published in non-English languages, pre-print or ahead of print analysis, pre-clinical studies, reviews, systematic reviews, and metanalysis were excluded too.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

With the assistance of a professional medical librarian at our institution, we determined our process for the literature search. We consulted the United States National Library of Medicine, PubMed (last accessed August 2022), and the Cochrane Controlled Trials (last accessed August 2022). References for this review were identified with the following research terms combination: “endogenous endophthalmitis” AND “gram negative”. As the term “gram negative” was often taken for granted in the title or abstract of articles regarding EBE caused by Klebsiella spp., E. coli, or Pseudomonas spp., we decided to expand our search strategy by also including these combinations: “endogenous endophthalmitis” AND “Klebsiella” OR “Pseudomonas” OR “Escherichia coli” which are considered as the Gram-negative bacteria predominantly involved in EBE [11,12].

2.3. Selection and Data Collection Process

A team of 7 resident doctors in Infectious and Tropical Diseases of the University of Brescia, Italy, read the abstract of each scientific work and independently selected the articles according to the established criteria (SA, DL, MM, AM, SS, GT). A Professor in Infectious and Tropical Diseases and an Ophthalmologist of the ASST Spedali Civili di Brescia, Italy, revised the included and the rejected papers. Then, resident doctors formed two teams: the first one (SA, AM, SS, GT) collected data by considering each selected article full text, while the second group (DL, MM) created a thorough database to revise, compare and synthesise data. An ophthalmologist revised the collection and synthesis of the ophthalmologic data. No automated tools were used.

2.4. Data Items

For each selected article, we collected information regarding the number of patients with an EBE due to a Gram-negative infection, their demographic data (age, sex, and ethnicity), comorbidities, and the number of eyes involved, specifying (when available) if a right/left eye was affected. Aetiological data (Gram-negative bacteria involved, culture type and source of infection), as well as initial ocular lesions and visual acuity were reported. Furthermore, we assessed ocular and systemic complications, medical therapy (anti-Gram-negative topical, intravitreal, or systemic antibiotics along with the addition of steroids) and the eventual surgical approach employed. We reported the general and ocular outcome and of a follow-up visit within the 12 months after discharge had been performed. Missing or unclear data were reported as “non-available”. Similarly, we considered “non-available” data regarding EBE due to a Gram-negative infection but impossible to extrapolate because included in more comprehensive studies concerning endophthalmitis in general.

2.5. Synthesis Methods

All the collected data were reported in a single table that was revised by an independent group. Every column was specifically associated with a different item. In the case of columns with less than 5 records, a grouping of the result was performed: i.e., in the case of poorly represented bacterial species, we preferred grouping them under an “other gram-negative aetiology” column. We limited our study to a descriptive analysis of our findings due to the wide heterogenicity of the articles selected. The percentage calculation was performed in consideration of the number of data available for each specific item. No models to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity or sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the synthesised results were performed.

2.6. Bias and Certainty Assessment

This is a systematic review for which a descriptive analysis has been performed due to the wide heterogenicity of the selected articles. Risk of bias or certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence was not assessed.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Search Results

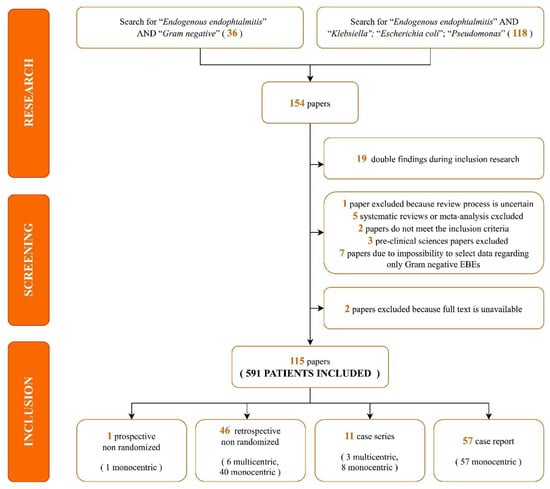

A total of 154 papers were identified through our search. We excluded 19 duplicate articles. A further eight analyses were removed as five were systematic reviews or meta-analyses [3,13,14,15,16] and three were pre-clinical sciences papers [17,18,19]. Moreover, two studies were excluded because the full text was unavailable [20,21] and one paper was removed due to a lack of data regarding the peer-revision process of the journal [22]. The remaining 124 articles were assessed for eligibility. Seven were excluded as data regarding EBE due to a Gram-negative infection were available, but impossible to select [23,24,25,26,27,28,29] and two further analyses were removed as they did not fully meet the inclusion criteria [30,31]. Eventually, 115 studies were included, as shown in the following flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search strategy and selection process flow-chart.

Most studies were case reports (57, 49.6%) and retrospectively non-randomized (46, 40%). Regarding the geographic distribution of the studies, 58.1% of the articles were from Asia, 13.2% were from Europe, and 9.6% were from America. Study characteristics, patient comorbidities, and aetiologic data included are summarized in Table 1 [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146].

Table 1.

Summary table regarding study characteristics, aetiologic data and patients’ comorbidities.

3.2. Results of Synthesis

A total of 591 patients were included. Considering the available demographic data, patients were prevalently Asian (98/120, 81.7%), male (302/480, 62.9%), and with a median age of 55.6 years old. As shown in Table 2, the most common comorbidities identified were diabetes mellitus (231, 55%), hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases (79, 18.8%), renal diseases (21, 5.0%), and malignancies (19, 4.5%).

Table 2.

Comorbidities in the selected population.

Overall, 592 infected eyes were involved, with a higher percentage of monocular EBE (429, 83.1%) than binoculars (67, 13%). Focusing on the available data, right eyes (277, 53.7%) were more involved than left eyes (239, 46.3%).

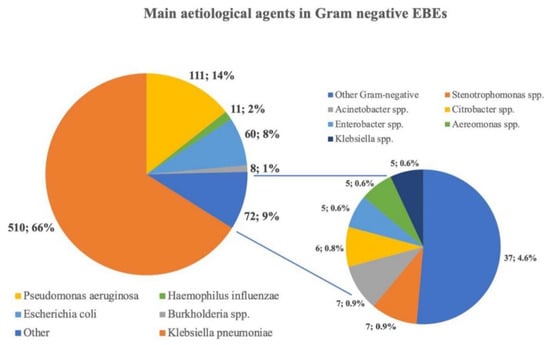

A total of 772 Gram-negative bacteria were included. As shown in Figure 2, Klebsiella pneumoniae (510, 66.1%) was the most common pathogen isolated in the case of Gram-negative EBE, followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (111, 14.4%), Escherichia coli (60, 7.8%), and Haemophilus influenzae (11, 1.4%).

Figure 2.

Prevalent aetiology found in this systematic review. Each pathogen included in the “Other” group represents less than 1% of the aetiology reported. Klebsiella spp. = Klebsiella other than K. pneumoniae.

These pathogens were isolated both from non-ocular (387, 42.5%) and ocular samples (286, 57.5%). More specifically, the microbiological diagnosis was prevalently performed on vitreous culture (239, 83.6%) and blood cultures (273, 70.5%) when considering the overall number of ocular and non-ocular samples, respectively. As shown in Table 3, liver abscesses (266, 54.5%) represented the predominant primary source of infection of the described EBEs, followed by bloodstream infections/sepsis (116, 23.8%), pneumonia (37, 7.6%), and abdominal infections (37, 7.6%).

Table 3.

Source of infection.

Overall, 270 initial ocular lesions were described. Vitreous opacity (134, 49.6%) and hypopyon (95, 35.2%) were the most commonly reported distinctive signs of EBE (Table 4). At the patient’s hospital admission, HM or hand motion (84, 25.4%) and LP or light perception (66, 19.9%) were the most frequently described visual acuities. Ocular complications were uncommon: bulbar atrophy (24, 10.9%), retinal detachment (13, 5.9%), and perforation (12, 5.5%) were the most prevalent. The most frequent systemic complications were septic emboli (4, 2.0%) and central nervous system infections (3, 1.5%).

Table 4.

Initial ocular lesions.

Few studies reported accurate therapeutic information regarding the antibiotics used and their route of administration. Ceftriaxone (76, 30.9%) was the most widely used anti-Gram-negative systemic antibiotic agent, while fluoroquinolones (14, 14.4%) and ceftazidime (213, 78.0%) were prevalently administered as topical or intravitreal agents, respectively. Only 25 studies appropriately reported antimicrobial therapy’s duration, with an overall mean duration of 39.2 days (range 13 to 84 days). Few patients (69, 28.3%) needed concomitant steroids in addition to the ongoing antimicrobial regimen. Regarding the surgical approach, the most frequently reported techniques were vitrectomy (130, 24.1%) and evisceration/exenteration (60, 11.1%).

Regarding the clinical outcomes at the end of the hospitalization, most patients were discharged (238, 85%), and mortality was recorded in only 15 cases. A higher percentage of NLP or no light perception (301, 55.2%) was reported as final ocular outcome compared to the initial visual acuity assessed. Only 25 studies reported follow-up information, and only five relapses occurred within 12 months after discharge.

4. Discussion

This systematic review estimates the clinical and epidemiological impact of Gram-negative EE, by analysing over a hundred papers spanning 20 years. EBEs, defined as the infection of intraocular tissues resulting from the hematogenous spread of bacteria to the eye, are both a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for ophthalmologists and infectious diseases specialists [67]. Gram-negative EBEs are an undoubtedly consistent clinical reality associated with poorer outcomes due to the production of endotoxins and the phagocytosis-resistant capsules conferring greater virulence [67,147].

Our search shows that, in East Asian nations, many EBEs are caused by Gram-negative bacilli, including Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli [1]. Studies from Singapore and Taiwan showed that up to 70% of the organisms isolated from patients with EBE were Gram-negative [67]. Similarly, other analyses reported frequencies ranging from 22.2% to 77.1%, considering Gram-negative as causative agents of EBE [147]. Interestingly, Klebsiella was found to be the most common causative organism (31.7%-87.6%) followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa [147].

In our systematic review, Klebsiella pneumoniae was the most common pathogen isolated, while liver abscesses represented the primary source of infection. Indeed, the association of liver abscesses with Klebsiella as the causative organism is observed worldwide, especially when considering hypervirulent strains (hvKp) [6]. Although the mortality rate of hvKp liver abscess is relatively low compared to that associated with pyogenic liver abscesses caused by bacteria other than K. pneumoniae, hvKp infection can lead to metastatic complications that cause significant morbidity such as, for instance, EBE [15]. Most hvKp infections are community-acquired, often afflicting individuals without any predisposing medical condition [15]. The incidence of hvKp infections seems to be rising both in Asia and Europe, and this can be explained by the rates of hvKp-carriers that range from 19% to the alarming percentage of 88% of healthy Chinese adults [15,148]. In a recent systematic review, 1 out of 22 patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae pyogenic liver abscess was found to develop EBE. This is explained by the K antigen, a capsular polysaccharide and a well-established virulence factor that makes K1 serotype infection an independent risk factor for the development of EE [15].

Although cases of EBE have been reported in otherwise healthy and immunocompetent people, EBEs are frequently associated with many systemic risk factors, including chronic immune-compromising illnesses, immunosuppressive diseases or therapies, recent invasive surgery or gastrointestinal procedures, hepatobiliary tract infections, and intravenous drug use [67]. Diabetes is the primary underlying condition associated with EBE (46–63.86%) in Asia. Considering the current scenario of the COVID-19 pandemic, the heavy use of systemic corticosteroids can predispose patients to the subsequent development of EBE via steroid-induced diabetes [147,149]. Although the pathogenic mechanism is poorly understood, it is known that poor glycaemic control might impair neutrophilic hepatic Kupffer cells’ phagocytosis against the bacterial infiltrators arriving with portal blood [15]. A recent review of case series published between 2011 and 2020 stated that while diabetes mellitus remains one of the medical conditions most frequently associated with EBE, malignancies and intravenous drug use represent significant risk factors too [11]. Malignancies were thought to be prevalently associated with endogenous mould endophthalmitis, where Aspergillus spp. and Fusarium spp. were the major pathogens involved [1]. However, malignancies have also been found to be a risk factor in the case of Streptococcus spp., Pseudomonas spp., and Candida spp. endogenous endophthalmitis [11]. In our systematic review, while malignancies are well represented, a small percentage of intravenous drug use is reported. This is consistent with the current literature, since the majority of EBE in people who inject drugs are caused by Gram-positive rather than Gram-negative agents [150].

In our study, vitreous opacity and hypopyon were EBE’s most described initial lesions. However, eye redness (91, 33.8%) alone or together with other ocular signs was commonly reported. This finding, together with the not always severely compromised visual acuity, enlightens the need for ophthalmologists to maintain high suspicion for EBE in patients with intraocular inflammation and significant medical comorbidities [67]. Patients with EBE usually present acutely, complaining only about decreased vision and eye pain [1]. Systemic complications or more alarming local signs such as hypopyon or vitritis might be absent during the initial evaluation [1].

The treatment of EBE should include both ocular and systemic therapy. This is a pharmacokinetic consequence, since most antimicrobial agents have a poor penetration capacity into the avascular vitreous cavity when parenterally administered [67]. Therefore, intravitreal injections are the treatment of choice for EBE. In line with our findings, the most commonly used antimicrobials for empiric treatment are third generation cephalosporines for Gram-negative microorganisms, followed by amikacin and gentamicin, which were mostly used in combination regimens [151]. The notorious Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study, a randomized clinical trial conducted between 1991 and 1994, stated that 89.5% of Gram-negative organisms causing endophthalmitis were susceptible to both amikacin and ceftazidime [152]. Although the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria is a global issue, the antibiotic susceptibility patterns of Gram-negative bacteria from vitreous isolates have not significantly changed in the United States [152].

The role of additional steroids in EBE management is controversial. A recent study in the Cochrane Library states that the currently available evidence on the effectiveness of adjunctive steroid therapy versus antibiotics alone in managing acute endophthalmitis after intraocular surgery is inadequate [153]. A combined analysis of a very limited number of studies suggests that adjunctive steroids might provide a higher chance of having a better visual outcome at three months [153]. Moreover, another study shows a higher rate of enucleation/evisceration in patients who did not receive steroid therapy [147]. These controversial findings match the differences in clinical approaches to EBE management and treatment revealed by our systematic review, where just a few patients were treated with steroids in addition to the ongoing antimicrobial regimen.

Adequate source control is often warranted in the case of EBE. Surgical intervention is generally recommended for patients infected with virulent organisms, with bilateral involvement, severe vitreous involvement, and progressive worsening [67]. Our systematic review shows that vitrectomy is the most often used surgical procedure as it helps in removing infectious organisms, toxins, and inflammatory cells from the vitreous cavity, thus leading to a better diffusion of antibiotics and a faster recovery [147]. Vitrectomy has several clinical and diagnostic implications: it might save eyes with EBE and restore vision while also providing a higher diagnostic yield compared to a vitreous biopsy, thus helping identify the causative organism [147].

Prognosis is poor in cases of Gram-negative EBE. Despite aggressive therapy, often necessitating surgical intervention, the poor clinical outcome in the case of EBE might be related to a delay in the diagnosis and treatment or the absence of worldwide shared guidelines [15]. Although several factors are associated with the visual outcome, a central role seems to be played by the pathogen involved. A recent study reported that very poor visual acuity (20/400 or worse) is associated with several Gram-negative pathogens such as H. influenzae (69%), Serratia spp. (70%), and Pseudomonas spp. (92%) [1]. Although not uniformly observed across all studies, it has been hypothesized that Gram-negative EE’s poorer outcome could be linked to both Gram-negative endotoxin production and the presence of a phagocytosis-resistant capsule [147].

The findings of this systematic review should be seen in the light of some limitations. First, our research strategy includes a selection bias that cannot be eliminated. Indeed, by including the three main EBE aetiologies, “Klebsiella”, “Escherichia coli”, and “Pseudomonas” in the initial search, it is subordinate that their prevalence will be found to be higher. However, the selection of these species allowed the authors to consider more papers that would have otherwise been wrongfully excluded. Secondly, our systematic review is based on many case reports and case series, with only one prospective study and no RCTs. Consequently, the inclusion of retrospective studies describing aggregate data makes it hard to select data for each patient individually. Lastly, the heterogeneity of the studies included in the absence of methods to assess the risk of bias or certainty in the body of evidence restricted our review to descriptive analysis. Therefore, we limited our comprehensive analysis to a descriptive evaluation of the past 20 years’ literature on Gram-negative EBE. On the other hand, the main strength of this systematic review is the large sample size. In addition, as it was noted during the search phase that most of the scientific output on the subject is produced by ophthalmologists, this systematic review presented Gram-negative EBEs from an infectious diseases specialist’s point of view.

5. Conclusions

Although the literature on EBE mainly comprises case series or single case reports, Gram-negative EBE is an undoubtedly consistent clinical reality associated with poorer outcomes due to virulence and pathogenetic aspects of the Gram-negative’s structure. Klebsiella pneumoniae is the most common causative pathogen in Gram-negative EBE, especially in the Asian population or diabetic people. Although in our study vitreous opacity and hypopyon were the most often described initial lesions of EBE, eye redness alone or together with other ocular signs was commonly reported. This enlightens the need for ophthalmologists to maintain high suspicion for EBE in patients with intraocular inflammation and significant medical comorbidities. Our findings underscore the importance of considering ocular involvement in the case of Gram-negative infections. In light of an ageing population and considering the concerning phenomenon of Gram-negative antimicrobial resistance, EBEs’ appropriate management remains an open challenge for both ophthalmology and infectious disease specialists.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Q.-R. and D.L.; writing–original draft preparation, G.T., D.L., A.M., S.A., S.S., M.M. and E.Q.-R.; methodology, G.T., D.L., A.M., S.A., S.S., M.M. and E.Q.-R.; software, G.T., D.L., A.M., S.A., S.S., M.M. and E.Q.-R.; validation, G.T., D.L., A.M., S.A., S.S., M.M. and E.Q.-R.; investigation, G.T., D.L., A.M., S.A., S.S., M.M. and E.Q.-R.; resources, G.T., D.L., A.M., S.A., S.S., M.M. and E.Q.-R.; data curation, G.T., D.L., A.M., S.A., S.S., M.M. and E.Q.-R.; writing—review and editing, G.T., D.L., A.M., S.A., S.S., M.M., A.B., L.S., F.C. and E.Q.-R.; visualization, G.T., D.L., A.M., S.A., S.S., M.M., A.B., L.S., F.C. and E.Q.-R.; supervision G.T., D.L., A.M., S.A., S.S., M.M., A.B., L.S., F.C. and E.Q.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Durand, M.L. Bacterial and Fungal Endophthalmitis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regan, K.A.; Radhakrishnan, N.S.; Hammer, J.D.; Wilson, B.D.; Gadkowski, L.B.; Iyer, S.S.R. Endogenous Endophthalmitis: Yield of the Diagnostic Evaluation. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, M.L. Endophthalmitis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coburn, P.S.; Wiskur, B.J.; Miller, F.C.; LaGrow, A.L.; Astley, R.A.; Elliott, M.H.; Callegan, M.C. Bloodstream-To-Eye Infections Are Facilitated by Outer Blood-Retinal Barrier Dysfunction. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.D.; Relhan, N.; Miller, D.; Flynn, H.W. Gram-Negative Bacteria from Patients with Endophthalmitis: Distribution of Isolates and Antimicrobial Susceptibilities. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2019, 13, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Francesco, M.A.; Tiecco, G.; Scaltriti, E.; Piccinelli, G.; Corbellini, S.; Gurrieri, F.; Crosato, V.; Moioli, G.; Marchese, V.; Focà, E.; et al. First Italian Report of a Liver Abscess and Metastatic Endogenous Endophthalmitis Caused by ST-23 Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in an Immunocompetent Individual. Infection 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdzis, M.; Figuła, K.; Kamińska, J.; Kaczmarek, R. Endogenous Endophthalmitis—The Clinical Significance of the Primary Source of Infection. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C.; Widder, J.; Raiji, V. Endophthalmitis. Dis.-A-Mon. 2017, 63, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simakurthy, S.; Tripathy, K. Endophthalmitis. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielescu, C.; Anton, N.; Stanca, H.T.; Munteanu, M. Endogenous Endophthalmitis: A Review of Case Series Published between 2011 and 2020. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samalia, P.D.; Welch, S.; Polkinghorne, P.J.; Niederer, R.L. Endogenous Endophthalmitis: A 21-Year Review of Cases at a Tertiary Eye Care Centre. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2022, 30, 1414–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittisupamongkol, W. Correspondence: Fastidious Gram-Negative Bacilli Such as HACEK and Haemophilus as Causes of Bilateral Endogenous Endophthalmitis. Retina 2010, 30, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, K.L.; Lin, R.T.P.; Teo, J.W.P. Klebsiella pneumoniae in Singapore: Hypervirulent Infections and the Carbapenemase Threat. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, I.; Ishrat, S.; Ho, D.C.W.; Khan, S.R.; Veeraraghavan, M.A.; Palraj, B.R.; Molton, J.S.; Abid, M.B. Endogenous Endophthalmitis in Klebsiella pneumoniae Pyogenic Liver Abscess: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 101, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teweldemedhin, M.; Gebreyesus, H.; Atsbaha, A.H.; Asgedom, S.W.; Saravanan, M. Bacterial Profile of Ocular Infections: A Systematic Review. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017, 17, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollreisz, A.; Rafferty, B.; Kozarov, E.; Lalla, E. Klebsiella pneumoniae Induces an Inflammatory Response in Human Retinal-Pigmented Epithelial Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 418, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, C.; Salmeri, M.; Anfuso, C.D.; Amodeo, A.; Scalia, M.; Toscano, M.A.; Giurdanella, G.; Alberghina, M.; Lupo, G. Klebsiella pneumoniae Induces an Inflammatory Response in an in Vitro Model of Blood-Retinal Barrier. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Selva Pandiyan, A.; Siva Ganesa Karthikeyan, R.; Rameshkumar, G.; Sen, S.; Lalitha, P. Identification of Bacterial and Fungal Pathogens by RDNA Gene Barcoding in Vitreous Fluids of Endophthalmitis Patients. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 35, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-P.; Chang, F.-Y.; Fung, C.-P.; Siu, L.-K. Klebsiella pneumoniae Liver Abscess in Taiwan Is Not Caused by a Clonal Spread Strain. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2002, 35, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kashani, A.H.; Eliott, D. Bilateral Klebsiella pneumoniae (K1 Serotype) Endogenous Endophthalmitis as the Presenting Sign of Disseminated Infection. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2011, 42, e12–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, S.-J.; Chou, L.-C.; Hong, M.-C.; Hsiao, Y.-C.; Liu, Y.-C. Risk Factors for Endogenous Endophthalmitis Secondary to Klebsiella pneumoniae Liver Abscess. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei) 2002, 65, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell, P.P.; O’Neill, E.C.; Fabinyi, D.; Islam, F.M.A.; Buttery, R.; McCombe, M.; Essex, R.W.; Roufail, E.; Clark, B.; Chiu, D.; et al. Endogenous Endophthalmitis: 10-Year Experience at a Tertiary Referral Centre. Eye 2011, 25, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, R.; Bharathi, M.J.; Shivkumar, C.; Mittal, S.; Meenakshi, R.; Khadeer, M.A.; Avasthi, A. Microbiological Profile of Culture-Proven Cases of Exogenous and Endogenous Endophthalmitis: A 10-Year Retrospective Study. Eye 2009, 23, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, G.-Z.; Jiang, R.; Ni, Y.-Q.; Wang, K.-Y.; Gu, R.-P.; Ding, X.-Y. Pediatric Infectious Endophthalmitis: A 271-Case Retrospective Study at a Single Center in China. Chin. Med. J. 2016, 129, 2936–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.H.; Chen, M.F.; Coleman, A.L. Adjunctive Steroid Therapy versus Antibiotics Alone for Acute Endophthalmitis after Intraocular Procedure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD012131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, B.; Rodrigues, C.; Deshmukh, M.; Natarajan, S.; Kamdar, P.; Mehta, A. Broad-Range Bacterial and Fungal DNA Amplification on Vitreous Humor from Suspected Endophthalmitis Patients. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2006, 10, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaburaki, T.; Takamoto, M.; Araki, F.; Fujino, Y.; Nagahara, M.; Kawashima, H.; Numaga, J. Endogenous Candida albicans Infection Causing Subretinal Abscess. Int. Ophthalmol. 2010, 30, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.-C.; Ho, J.-D.; Lou, H.-Y.; Keller, J.J.; Lin, H.-C. A One-Year Follow-up Study on the Incidence and Risk of Endophthalmitis after Pyogenic Liver Abscess. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 2358–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.-H.; Kurup, A.; Wang, Y.-S.; Heng, K.-S.; Tan, K.-C. Four Cases of Necrotizing Fasciitis Caused by Klebsiella species. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2004, 23, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, M.J.; Megharaj, C.; Patil, S.; Rani, P.K. Cryptococcus laurentii Endogenous Endophthalmitis Post COVID-19 Infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2022, 15, e246637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, G.; Yen, C.-L.; Lu, Y.-A.; Chen, C.-Y.; Sun, M.-H.; Lin, Y.; Tian, Y.-C.; Hsu, H.-H. Clinical and Visual Outcomes Following Endogenous Endophthalmitis: 175 Consecutive Cases from a Tertiary Referral Center in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2022, 55, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, J.M.; Elinav, H.; Tiosano, L.; Amer, R. Endophthalmitis Panorama in the Jerusalem Area. Int. Ophthalmol. 2022, 42, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, M.; He, L.; Zheng, P.; Shi, X. Clinical Features and Mortality of Endogenous Panophthalmitis in China: A Six-Year Study. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 37, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Xia, H.; Tang, R.; Ng, T.K.; Yao, F.; Liao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Ke, X.; Shi, T.; Chen, H. Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing Detects Pathogens in Endophthalmitis Patients. Retina 2022, 42, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourthai, P.; Choopong, P.; Dhirachaikulpanich, D.; Soraprajum, K.; Pinitpuwadol, W.; Punyayingyong, N.; Ngathaweesuk, Y.; Tesavibul, N.; Boonsopon, S. Visual Outcome of Endogenous Endophthalmitis in Thailand. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, G.; Remadevi, K.; Anilkumar, V.; Radhakrishnan, N.; Rasheed, R.; Ravindran, G. Clinical Profile and Outcome of Endogenous Endophthalmitis at a Quaternary Referral Centre in South India. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei, S.A.; Soleimani, M.; Mirshahi, R.; Bohrani, B.; Aminizade, M. Culture-Proven Endogenous Endophthalmitis: Microbiological and Clinical Survey. Int. Ophthalmol. 2020, 40, 3521–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounder, P.A.; Hille, D.M.; Khoo, Y.J.; Phagura, R.S.; Chen, F.K. Endogenous Endophthalmitis In Western Australia. Retina 2020, 40, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, V.; Pathengay, A.; Panchal, B.; Jindal, A.; Datta, A.; Sharma, S.; Pappuru, R.; Joseph, J.; Jalali, S.; Das, T. Clinical Presentations, Microbiology and Management Outcomes of Culture-Proven Endogenous Endophthalmitis in India. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Huang, X.; Jiang, S.; Xu, Z. Endogenous Endophthalmitis Caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae: A Ten-Year Retrospective Study in Western China. Ophthalmic Res. 2020, 63, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Manandhar, A. Microbiological Patterns of Endophthalmitis in a Tertiary Level Hospital of Kathmandu, Nepal. Nepal. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 12, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Di, Y. Surgery Combined with Antibiotics for the Treatment of Endogenous Endophthalmitis Caused by Liver Abscess. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, M.-C.; Chen, S.-N.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Li, K.-H.; Chuang, C.-C.; Wu, J.-S.; Lee, S.-T.; Chiu, S.-L. Clinicomicrobiological Profile, Visual Outcome and Mortality of Culture-Proven Endogenous Endophthalmitis in Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silpa-archa, S.; Ponwong, A.; Preble, J.M.; Foster, C.S. Culture-Positive Endogenous Endophthalmitis: An Eleven-Year Retrospective Study in the Central Region of Thailand. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2017, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celiker, H.; Kazokoglu, H. Ocular Culture-Proven Endogenous Endophthalmitis: A 5-Year Retrospective Study of the Microorganism Spectrum at a Tertiary Referral Center in Turkey. Int. Ophthalmol. 2019, 39, 1743–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.Y.; Wong, E.S.; Liu, C.C.H.; Wong, M.O.M.; Li, K.K.W. Clinical Features and Prognostic Factors of Klebsiella Endophthalmitis—10-Year Experience in an Endemic Region. Eye 2017, 31, 1569–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Lee, Y.-Y.; Chen, Y.-H.; Lin, H.-S.; Wu, T.-T.; Sheu, S.-J. Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection Leads to a Poor Visual Outcome in Endogenous Endophthalmitis: A 12-Year Experience in Southern Taiwan. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2017, 25, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, G.; Lu, Y.-A.; Sun, W.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Kao, H.-K.; Lin, Y.; Lee, C.-H.; Hung, C.-C.; Tian, Y.-C.; Hsu, H.-H. Epidemiology and Outcomes of Endophthalmitis in Chronic Dialysis Patients: A 13-Year Experience in a Tertiary Referral Center in Taiwan. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-J.; Chen, Y.-P.; Chao, A.-N.; Wang, N.-K.; Wu, W.-C.; Lai, C.-C.; Chen, T.-L. Prevention of Evisceration or Enucleation in Endogenous Bacterial Panophthalmitis with No Light Perception and Scleral Abscess. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satpathy, G.; Nayak, N.; Wadhwani, M.; Venkwatesh, P.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, Y.; Sreenivas, V. Clinicomicrobiological Profile of Endophthalmitis: A 10 Year Experience in a Tertiary Care Center in North India. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2017, 60, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Shin, Y.U.; Siegel, N.H.; Yu, H.G.; Sobrin, L.; Patel, A.; Durand, M.L.; Miller, J.W.; Husain, D. Endogenous Endophthalmitis in the American and Korean Population: An 8-Year Retrospective Study. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2016, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Artsi, E.; Katz, G.; Kinori, M.; Moisseiev, J. Endophthalmitis Today: A Multispecialty Ophthalmology Department Perspective. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 26, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falavarjani, K.G.; Alemzadeh, S.A.; Habibi, A.; Hadavandkhani, A.; Askari, S.; Pourhabibi, A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Endophthalmitis: Clinical Outcomes and Antibiotic Susceptibilities. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2017, 25, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, I.H.; Jun, C.H.; Wi, J.W.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, W.S.; Jung, S.I.; Park, C.H.; Joo, Y.E.; Kim, H.S.; Choi, S.K.; et al. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Endogenous Endophthalmitis in Patients with Pyogenic Liver Abscesses. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratra, D.; Saurabh, K.; Das, D.; Nachiappan, K.; Nagpal, A.; Rishi, E.; Bhende, P.; Sharma, T.; Gopal, L. Endogenous Endophthalmitis: A 10-Year Retrospective Study at a Tertiary Hospital in South India. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. (Phila) 2015, 4, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, J.; Kuriyan, A.E.; Flynn, H.W.; Miller, D. Endophthalmitis Caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Retina 2015, 35, 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.W.; Shin, J.W.; Cho, H.Y.; Kim, H.K.; Kang, S.W.; Song, S.J.; Yu, H.G.; Oh, J.R.; Kim, J.S.; Moon, S.W.; et al. Endogenous Endophthalmitis in the Korean Population. Retina 2014, 34, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasudha, R.; Narendran, V.; Manikandan, P.; Prabagaran, S.R. Identification of Polybacterial Communities in Patients with Postoperative, Posttraumatic, and Endogenous Endophthalmitis through 16S RRNA Gene Libraries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kim, K.H. Endogenous Endophthalmitis Complicated by Pyogenic Liver Abscess: A Review of 17 Years’ Experience at a Single Center. Digestion 2014, 90, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, S.; Pehere, N.; Rani, P.K.; Bobbili, R.B.; Nalamada, S.; Motukupally, S.R.; Sharma, S. Treatment Outcomes and Clinicomicrobiological Characteristics of a Protocol-Based Approach for Neonatal Endogenous Endophthalmitis. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 24, 424–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Chung, I.Y.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, J.E.; Park, J.M.; Park, J.M.; Han, Y.S.; Oum, B.S.; Byon, I.S.; et al. Emergence of Enterococcus species in the Infectious Microorganisms Cultured from Patients with Endophthalmitis in South Korea. Infection 2014, 42, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Um, T.; Joe, S.G.; Hwang, J.-U.; Kim, J.-G.; Yoon, Y.H.; Lee, J.Y. Changes in the Clinical Features and Prognostic Factors Of Endogenous Endophthalmitis. Retina 2012, 32, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheu, S.-J.; Kung, Y.-H.; Wu, T.-T.; Chang, F.-P.; Horng, Y.-H. Risk Factors for Endogenous Endophthalmitis Secondary to Klebsiella pneumoniae Liver Abscess: 20-Year Experience in Southern Taiwan. Retina 2011, 31, 2026–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.-J.; Sun, M.-H.; Lai, C.-C.; Wu, W.-C.; Chen, T.-L.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Chao, A.-N.; Hwang, Y.-S.; Chen, Y.-P.; Wang, N.-K.; et al. Endophthalmitis Caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa In Taiwan. Retina 2011, 31, 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.S.; Kim, Y.K.; Song, Y.G.; Kim, C.O.; Han, S.H.; Chin, B.S.; Gu, N.S.; Jeong, S.J.; Baek, J.-H.; Choi, J.Y.; et al. Clinical Review of Endogenous Endophthalmitis in Korea: A 14-Year Review of Culture Positive Cases of Two Large Hospitals. Yonsei Med. J. 2011, 52, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Z. Endogenous Endophthalmitis: A 10-Year Review of Culture-Positive Cases in Northern China. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2010, 18, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Pai, V.; Levinson, R.; Sharpe, A.H.; Freeman, G.J.; Braun, J.; Gordon, L.K. Constitutive Neuronal Expression of the Immune Regulator, Programmed Death 1 (PD-1), Identified During Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2009, 17, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sng, C.C.A.; Jap, A.; Chan, Y.H.; Chee, S.-P. Risk Factors for Endogenous Klebsiella Endophthalmitis in Patients with Klebsiella Bacteraemia: A Case-Control Study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 92, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.C.; Niederer, R.L.; von Lany, H.; Polkinghorne, P.J. Infectious Endophthalmitis: Clinical Features, Management and Visual Outcomes. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2008, 36, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, T.; Pelz, K.; Hansen, L.L. Endogenous Endophthalmitis: Microorganisms, Disposition and Prognosis. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 2007, 85, 852–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keswani, T.; Ahuja, V.; Changulani, M. Evaluation of Outcome of Various Treatment Methods for Endogenous Endophthalmitis. Indian J. Med. Sci. 2006, 60, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leibovitch, I.; Lai, T.; Raymond, G.; Zadeh, R.; Nathan, F.; Selva, D. Endogenous Endophthalmitis: A 13-Year Review at a Tertiary Hospital in South Australia. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 37, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Kuo, H.-K.; Wu, P.-C.; Kuo, M.-L.; Tsai, H.-H.; Liu, C.-C.; Chen, C.-H. A 10-Year Comparison of Endogenous Endophthalmitis Outcomes: An East Asian Experience with Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection. Retina 2004, 24, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiedler, V.; Scott, I.U.; Flynn, H.W.; Davis, J.L.; Benz, M.S.; Miller, D. Culture-Proven Endogenous Endophthalmitis: Clinical Features and Visual Acuity Outcomes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2004, 137, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.-M.; Chee, S.-P.; Soo, K.-C.; Chow, P. Ocular Manifestations and Complications of Pyogenic Liver Abscess. World J. Surg. 2004, 28, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.L.; Eykyn, S.J.; Graham, E.M.; Stanford, M.R. Endogenous Bacterial Endophthalmitis: A 17-Year Prospective Series and Review of 267 Reported Cases. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2003, 48, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.H.; Lee, S.U.; Sohn, J.-H.; Lee, S.E. Result of Early Vitrectomy for Endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae Endophthalmitis. Retina 2003, 23, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Chen, F.; Xie, Z. Report of Four Cases of Endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae Endophthalmitis Originated from Liver Abscess with Eye Complaints as the Initial Presentations. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2022, 30, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.V.; González, J.A.P.; Galindo-Ferreiro, A.; Monar, P.S.C.; Tarancón, A.M.A.; Frutos, M.P.G.D. Liver Abscess and Endogenous Endophthalmitis Secondary to Klebsiella variicola in a Patient with Diabetes: First Reported Case. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2022, 85, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-González, M.; Marín-Payá, E.; Pérez-López, M.; Bort-Martínez, M.Á.; Aviñó-Martínez, J.; España-Gregori, E. Posterior Scleral Perforation Due to Endogenous Endophthalmitis in a Pregnant with Selective IgA Deficiency. Rom. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 66, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Schlenker, A.C.; Dolman, P.J.; Wong, V.A. Two Cases of Bilateral Blindness from Klebsiella pneumoniae Endogenous Endophthalmitis. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 56, e155–e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgic, A.; Sudhalkar, A.; Gonzalez-Cortes, J.H.; March de Ribot, F.; Yogi, R.; Kodjikian, L.; Mathis, T. Endogenous Endophthalmitis in the Setting of COVID-19 Infection. Retina 2021, 41, 1709–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P.; Sinha, U.; Raj, A.; Pati, B.K. Bilateral Endogenous Endophthalmitis Complicated by Scleral Perforation: An Unusual Presentation. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e244547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Xia, J.; Zhang, F.; Huang, R.; Chen, Z.; Liu, J. Case Report of Catheter-Related Klebsiella pneumoniae Endophthalmitis. Clin. Lab. 2021, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, C.; Lopes, S.; Mendes, S.; Almeida, N.; Figueiredo, P. Endogenous Endophthalmitis and Liver Abscess: A Metastatic Infection or a Coincidence? GE Port. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 29, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamau, E.; Allyn, P.R.; Beaird, O.E.; Ward, K.W.; Kwan, N.; Garner, O.B.; Yang, S. Endogenous Endophthalmitis Caused by ST66-K2 Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 2215–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentecost, G.S.; Kesterson, J. Pyogenic Liver Abscess and Endogenous Endophthalmitis Secondary to Klebsiella pneumoniae. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 41, 264.e1–264.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurumkattil, R.; Trehan, H.; Tandel, K.; Sharma, V.; Dhar, S.; Mahapatra, T. Endogenous Endophthalmitis Secondary to Burkholderia cepacia: A Rare Presentation. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-de-Lossada, C.; Díaz Antonio, T.; Rachwani Anil, R.; Cuartero Jiménez, E. Meningoencephalitis Due to Endogenous Endophthalmitis by Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Diabetic Patient. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Takahashi, A.; Imaizumi, H.; Hayashi, M.; Okai, K.; Abe, K.; Ohira, H. Endogenous Endophthalmitis Associated with Pyogenic Liver Abscess Caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. Intern. Med. 2019, 58, 2507–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, A.D.; Wiggins, N.B.; Ansari, W.; Hwang, C.J.; Wilkoff, B.L.; Perry, J.D. Cautery Selection for Oculofacial Plastic Surgery in Patients with Implantable Electronic Devices. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 29, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Shen, J.; Lu, Z.; Liu, Y. Endogenous Endophthalmitis Caused by Carbapenem-Resistant Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: A Case Report and Literature Review. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2019, 27, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, M.; Singh, S.R.; Thattaruthody, F. Klebsiella pneumoniae Endogenous Endophthalmitis Mimicking a Choroidal Neovascular Membrane with Subretinal Hemorrhage. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2020, 28, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillsbury, M.M.; Geha, R.M.; Edson, R.S. Sticky Business: A Syndrome of Mucoid Bacterial Spread. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 12, e226956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Li, A.; Kong, H.; Zhang, W.; Chen, H.; Fu, Y.; Fu, Y. Endogenous Endophthalmitis Caused by a Multidrug-Resistant Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae Strain Belonging to a Novel Single Locus Variant of ST23: First Case Report in China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, U.; Benson, M.D.; Kulkarni, S.; Greve, M.D.J. Endogenous Endophthalmitis Due to Klebsiella pneumoniae from an Infected Gallbladder. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 53, e258–e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, C.Y.; Sin, H.P.; Chan, V.C.; Young, A. Klebsiella Endophthalmitis as the Herald of Occult Colorectal Cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2018, 2018, bcr-2017-223400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, M.; Sharma, M.; Katoch, D.; Dogra, M. Management of Multi Drug Resistant Endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae Endophthalmitis with Intravitreal and Systemic Colistin. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 66, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Chu, S.T.; Lee, K.S.; Nam, S.W.; Choi, J.K.; Chung, J.W.; Kwon, H.C. Metastatic Endophthalmitis and Thyroid Abscess Complicating Klebsiella pneumoniae Liver Abscess. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2018, 24, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadia, S.D.; Modi, R.R.; Shirwadkar, S.; Potdar, N.A.; Shinde, C.A.; Nair, A.G. Salmonella typhi Associated Endogenous Endophthalmitis: A Case Report and a Review of Literature. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2017, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Fu, B.; Lu, C.; Xu, L.; Sun, J. Successful Treatment of Endogenous Endophthalmitis with Extensive Subretinal Abscess: A Case Report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018, 18, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odouard, C.; Ong, D.; Shah, P.R.; Gin, T.; Allen, P.J.; Downie, J.; Lim, L.L.; McCluskey, P. Rising Trends of Endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae Endophthalmitis in Australia. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2017, 45, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, A.; Butet, B.; Ramel, J.C.; Martiano, D.; Baillif, S. Medical Management of a Subretinal Klebsiella pneumoniae Abscess with Excellent Visual Outcome without Performing Vitrectomy. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 2017, 40, 876–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, E.H.; Powers, M.A.; Moshfeghi, D.M. Spontaneous Globe Rupture Due to Rapidly Evolving Endogenous Hypermucoid Klebsiella pneumoniae Endophthalmitis. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2017, 48, 600–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, N.M.; Chandra, A.; Roufail, E.; Moodie, J.J.; Yeoh, J.; Allen, P.J.; Salinas-La Rosa, C.M.; Matthews, B.J. Chorioretinal Biopsy for the Diagnosis of Endogenous Endophthalmitis Due to Escherichia coli. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2017, 11, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kharashi, A.S. Endogenous Endophthalmitis Caused by Brucella melitensis. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2016, 10, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.; Raman, V. Serratia marcescens Endogenous Endophthalmitis in an Immunocompetent Host. BMJ Case Rep. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guber, J.; Saeed, M. Presentation and Outcome of a Cluster of Patients with Endogenous Endophthalmitis: A Case Series. Klin. Mon. Augenheilkd. 2015, 232, 595–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, G.D.J.-Y.; Lo, E.C.-F.; Young, A. Endogenous Endophthalmitis with a Visual Acuity of 6/6. Case Rep. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, P.P.; McGowan, G.F.; Sandhu, S.S.; Allen, P.J. Klebsiella pneumoniae Liver Abscess Complicated by Endogenous Endophthalmitis: The Importance of Early Diagnosis and Intervention. Med. J. Aust. 2015, 203, 300–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, J.W.H.; Tsang, F.C.W.; Fung, K.S.C.; Li, K.K.W. Presumed Aggregatibacter aphrophilus Endogenous Endophthalmitis. Int. Ophthalmol. 2015, 35, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Zhou, H.; Li, C. Endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae Endophthalmitis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2014, 32, 1300.e3–1300.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, C.; Kumar, K.; Sinha, M.K.; Venkata, A.; Majji, A.B.; Jalali, S. Review of Endogenous Endophthalmitis during Pregnancy Including Case Series. Int. Ophthalmol. 2013, 33, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, S.; Kumar, A.; Kapoor, K.; Bagri, N.K.; Chandra, A. Neonatal Endogenous Endophthalmitis: A Report of Six Cases. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1292–e1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruno, T.; Ooiwa, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Kodama, Y.; Takakura, S.; Ichiyama, S.; Chiba, T. A Liver Abscess Deprived a Healthy Adult of Eyesight: Endogenous Endophthalmitis Associated with a Pyogenic Liver Abscess Caused by Serotype K1 Klebsiella pneumonia. Intern Med. 2013, 52, 919–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sawada, A.; Komori, S.; Udo, K.; Suemori, S.; Mochizuki, K.; Yasuda, M.; Ohkusu, K. Case of Endogenous Endophthalmitis Caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae with MagA and RmpA Genes in an Immunocompetent Patient. J. Infect. Chemother. 2013, 19, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, I.H.; Sipkova, Z.; Patel, S.; Benjamin, L. Neisseria meningitidis Endogenous Endophthalmitis with Meningitis in an Immunocompetent Child. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2014, 22, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enani, M.A.; El-Khizzi, N.A. Community Acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae, K1 Serotype. Invasive Liver Abscess with Bacteremia and Endophthalmitis. Saudi Med. J. 2012, 33, 782–786. [Google Scholar]

- Suwan, Y.; Preechawai, P. Endogenous Klebsiella Panophthalmitis: Atypical Presentation. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2012, 95, 830–833. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mahmood, A.M.; Al-Binali, G.Y.; AlKatan, H.; Abboud, E.B.; Abu El-Asrar, A.M. Endogenous Endophthalmitis Associated with Liver Abscess Caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int. Ophthalmol. 2011, 31, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degoricija, V.; Skerk, V.; Vatavuk, Z.; Knezević, T.; Sefer, S.; Vućicević, Z. Bilateral Pseudomonas aeruginosa Endogenous Endophthalmitis in an Immune-Competent Patient with Nosocomial Urosepsis Following Abdominal Surgery. Acta Clin. Croat. 2011, 50, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Habeeb, S.Y.; Varma, D.K.; Ahmed, I.I.K. Oblique Illumination and Trypan Blue to Enhance Visualization through Corneal Scars in Cataract Surgery. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 46, 555–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.-J.; Hwang, Y.-S.; Wang, N.-K.; Chao, A.-N. Endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae Endophthalmitis with Renal Abscess: Report of Two Cases. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 14, e429–e432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, K.; Gyanendra, L.; Hari, S.; Dev Narayan, S. Culture Proven Endogenous Bacterial Endophthalmitis in Apparently Healthy Individuals. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2009, 17, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.-H.; Peng, M.-Y.; Chang, F.-Y.; Wang, Y.-C. Endogenous Endophthalmitis Caused by Citrobacter koseri. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2009, 338, 509–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodson, D.; Stewart, R.; Karcioglu, Z.; Conway, M.D.; Mushatt, D.; Ayyala, R.S. Klebsiella pneumoniae Endophthalmitis Secondary to Liver Abscess Presenting as Acute Iridocyclitis. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2009, 40, 522–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argelich, R.; Ibáñez-Flores, N.; Bardavio, J.; Burés-Jelstrup, A.; García-Segarra, G.; Coll-Colell, R.; Cuadrado, V.; Fernández-Monrás, F. Orbital Cellulitis and Endogenous Endophthalmitis Secondary to Proteus mirabilis Cholecystitis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2009, 64, 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karama, E.M.; Willermain, F.; Janssens, X.; Claus, M.; van den Wijngaert, S.; Wang, J.-T.; Verougstraete, C.; Caspers, L. Endogenous Endophthalmitis Complicating Klebsiella pneumoniae Liver Abscess in Europe: Case Report. Int. Ophthalmol. 2008, 28, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luemsamran, P.; Pornpanich, K.; Vangveeravong, S.; Mekanandha, P. Orbital Cellulitis and Endophthalmitis in Pseudomonas Septicemia. Orbit 2008, 27, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.K.W.; Tang, E.W.H.; Lai, J.S.M.; Wong, D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Choroidal Abscess in a Patient with Bronchiectasis. Int. Ophthalmol. 2008, 28, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, V.; Zaidi, F.; Larkin, G.; Muir, G.; Stanford, M. Bilateral Endogenous Endophthalmitis after Holmium Laser Lithotripsy. Urology 2007, 70, 590.e13–590.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.-J.; Sun, M.-H.; Hou, C.-H.; Sun, C.-C.; Chen, T.-L. Burkholderia pseudomallei Endophthalmitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 4073–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yodprom, R.; Pathanapitoon, K.; Kunavisarut, P.; Ausayakhun, S.; Wattananikorn, S.; Rothova, A. Endogenous Endophthalmitis Due to Salmonella choleraesuis in an HIV-Positive Patient. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2007, 15, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DÍaz-Valle, D.; del Castillo, J.M.B.; Aceñero, M.J.F.; Santos-Bueso, E.; de La Casa, J.M.M.; Garcia-Sanchez, J. Endogenous Pseudomonas Endophthalmitis in an Immunocompetent Patient. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 17, 461–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seale, M.; Lee, W.-K.; Daffy, J.; Tan, Y.; Trost, N. Fulminant Endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae Endophthalmitis: Imaging Findings. Emerg. Radiol. 2007, 13, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, V.E.S.; Jeevanan, J.; Lee, B.R. Parapharyngeal Abscess Complicated by Endophthalmitis: A Rare Presentation of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2008, 122, 867–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, S.; Chalermskulrat, W.; Miller, M.B.; Landers, M.; Aris, R.M. Bilateral Hematogenous Pseudomonas aeruginosa Endophthalmitis after Lung Transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2006, 6, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebayashi, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Nakagawa, Y.; Wakabayashi, S.; Aso, Y.; Inukai, T. Endogenous Endophthalmitis and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation Complicating a Klebsiella pneumoniae Perirenal Abscess in a Patient with Type 2 Diabetes. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2005, 329, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motley, W.W.; Augsburger, J.J.; Hutchins, R.K.; Schneider, S.; Boat, T.F. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Endogenous Endophthalmitis With Choroidal Abscess in a Patient with Cystic Fibrosis. Retina 2005, 25, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, M.; Nolan, L.; Lanigan, B.; Murphy, J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Endophthalmitis in a Preterm Infant. J. AAPOS 2005, 9, 288–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.-M.; Liu, D.T.L.; Fan, D.S.P.; Lau, T.T.Y.; Lam, D.S.C. Failure of Systemic Antibiotic in Preventing Sequential Endogenous Endophthalmitis of a Bronchiectasis Patient. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 139, 549–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matasova, K.; Hudecova, J.; Zibolen, M. Bilateral Endogenous Endophthalmitis as a Complication of Late-Onset Sepsis in a Premature Infant. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2003, 162, 346–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohmen, K.; Okubo, H.; Okabe, H.; Ishibashi, H. Endophthalmitis with Klebsiella pneumoniae Liver Abscess. Fukuoka Igaku Zasshi 2003, 94, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, P.; Clark, W.L.; Kaiser, P.K. Bilateral Endogenous Endophthalmitis Caused by HACEK Microorganism. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 133, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-H.; Chien, C.-C.; Fang, J.-T.; Lai, R.-H.; Huang, C.-C. Unusual Clinical Presentation of Klebsiella pneumoniae Induced Endogenous Endophthalmitis and Xanthogranulomatous Pyelonephritis in A Non-Nephrolithiasis and Non-Obstructive Urinary Tract. Ren. Fail. 2002, 24, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xie, C.A.; Singh, J.; Tyagi, M.; Androudi, S.; Dave, V.P.; Arora, A.; Gupta, V.; Agrawal, R.; Mi, H.; Sen, A. Endogenous Endophthalmitis—A Major Review. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECDC. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Risk Assessment: Emergence of Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae ST23 Carrying Carbapenemase Genes in EU/EEA Coun-tries. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/risk-assessment-emergence-hypervirulent-klebsiella-pneumoniae-eu-eea (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Franchini, M.; Glingani, C.; de Donno, G.; Lucchini, G.; Beccaria, M.; Amato, M.; Castelli, G.P.; Bianciardi, L.; Pagani, M.; Ghirardini, M.; et al. Convalescent Plasma for Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients: A Single-Center Experience. Life 2022, 12, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modjtahedi, B.S.; Finn, A.V.; Papakostas, T.D.; Durand, M.; Husain, D.; Eliott, D. Intravenous Drug Use–Associated Endophthalmitis. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2017, 1, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabbara, S.; Kelkar, N.; Conway, M.D.; Peyman, G.A. Endogenous Endophthalmitis: Etiology and Treatment. In Infectious Eye Diseases—Recent Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relhan, N.; Forster, R.K.; Flynn, H.W. Endophthalmitis: Then and Now. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 187, xx–xxvii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, S.; Kitayama, K.; Coleman, A.L. Adjunctive Steroid Therapy versus Antibiotics Alone for Acute Endophthalmitis after Intraocular Procedure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 6, CD012131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).