Experimental Evaluation of the Impacts of Suspended Particle Device Smart Windows with Glare Control on Occupant Thermal and Visual Comfort Levels in Winter

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Review of Occupant Comfort Indicators

3.1. PMV

- = metabolic rate (;

- * 1 metabolic rate = 1 met = ;

- = effective mechanical power (;

- = clothing insulation (;

- * 1 clothing unit = 1 clo = W;

- = clothing surface area factor;

- = air temperature ;

- = mean radiant temperature ;

- = relative air velocity ;

- = water vapor partial pressure (Pa);

- = convective heat transfer coefficient ;

- = clothing surface temperature .

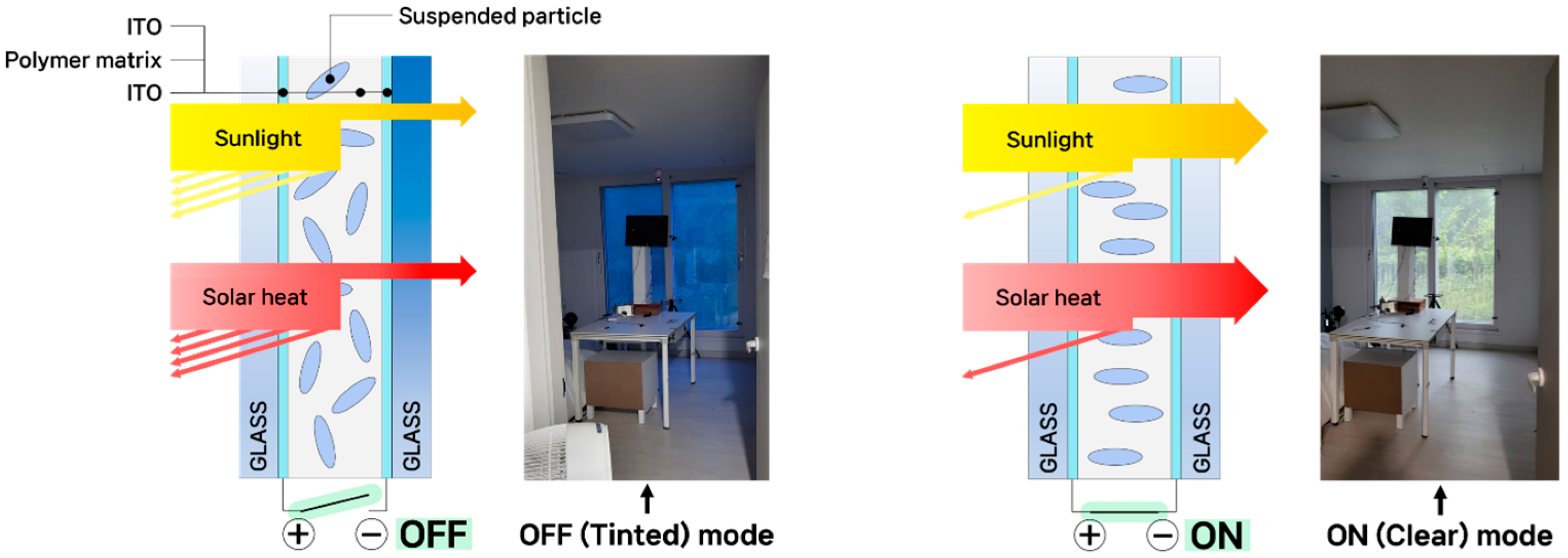

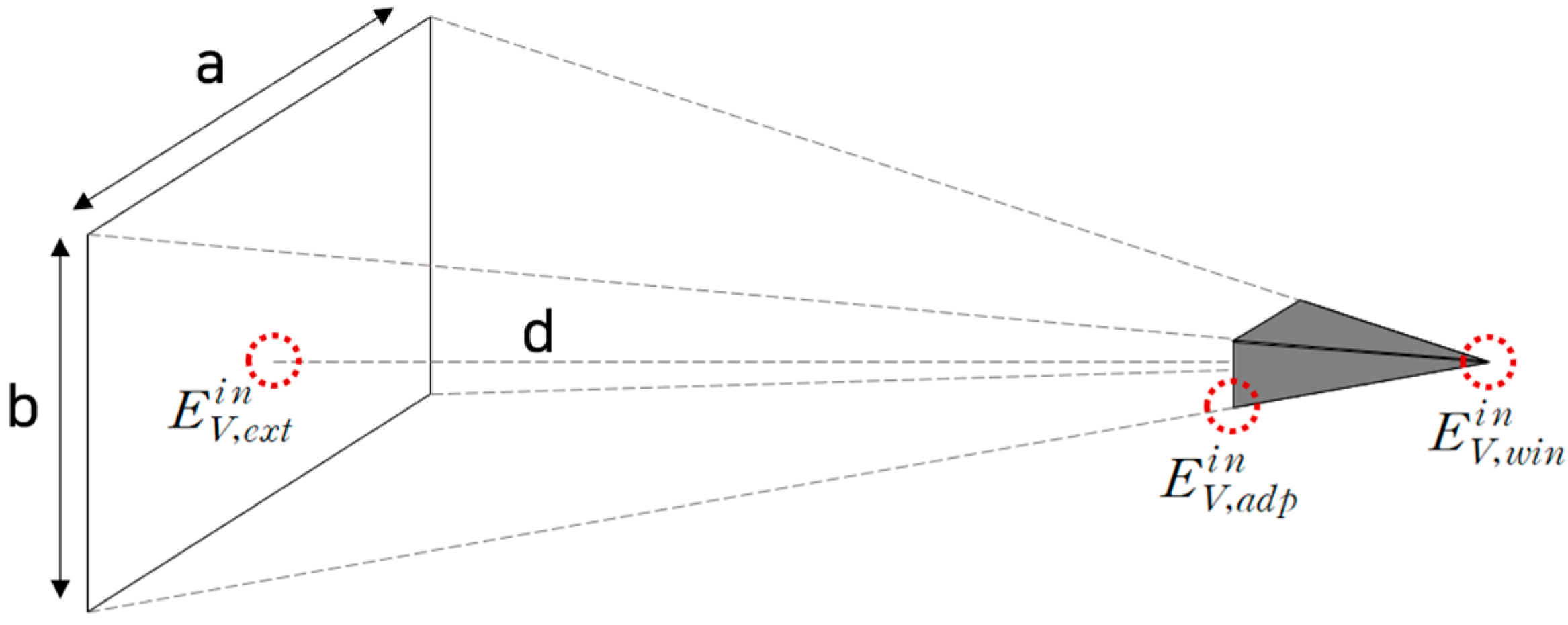

3.2. DGIN

- : Luminance of each segment of the light source ();

- : Average luminance of environmental surfaces within the field of view ();

- : Composition-weighted window luminance ();

- : Solid angle of the light source ();

- : Solid angle of the window ().

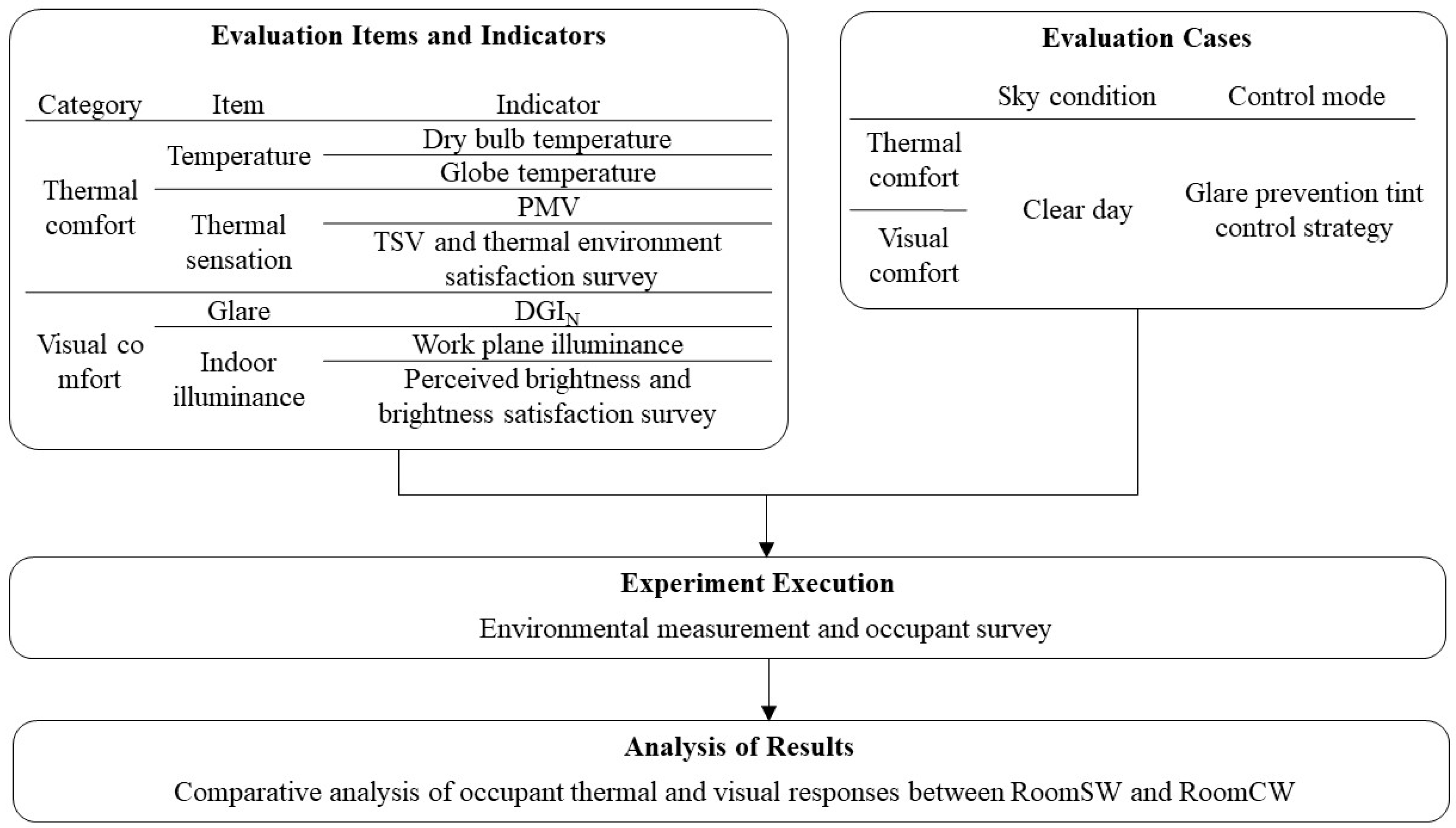

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Evaluation Indicators and Case Definitions

4.2. Experimental Building

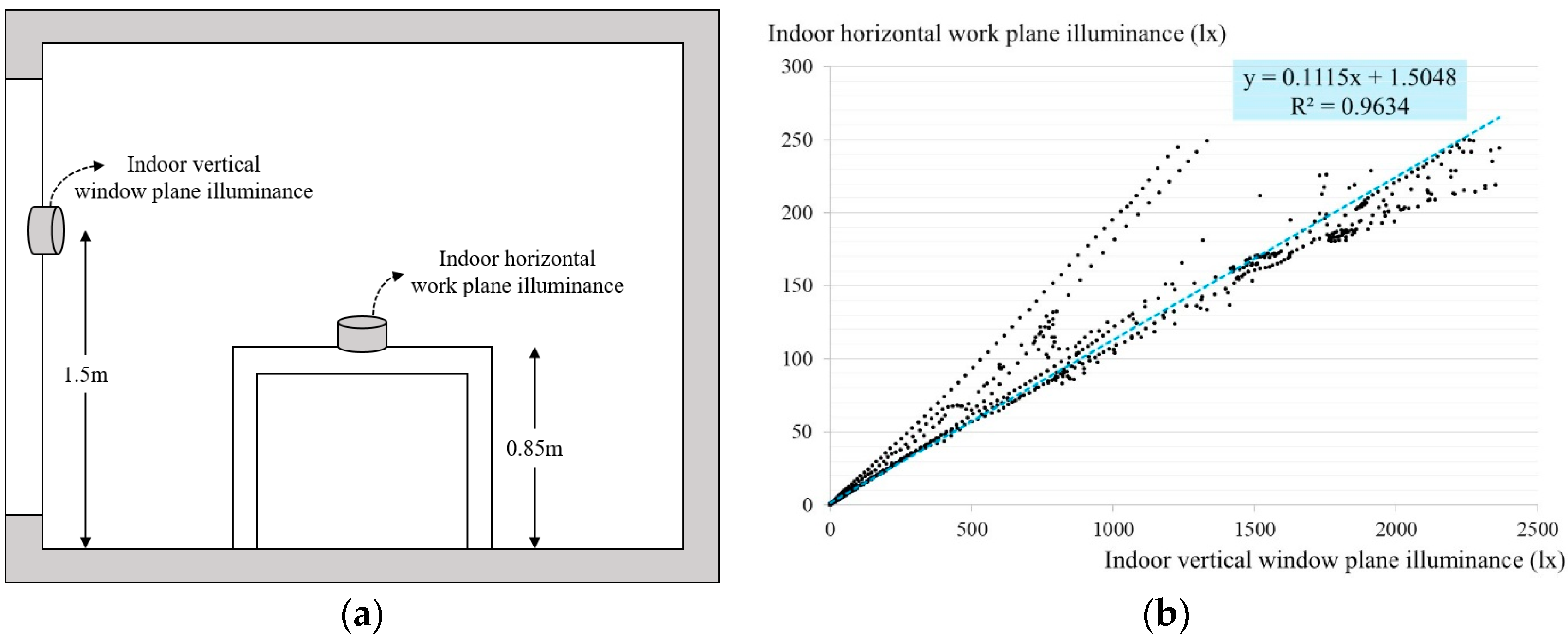

4.3. Measurements

4.4. Subjects

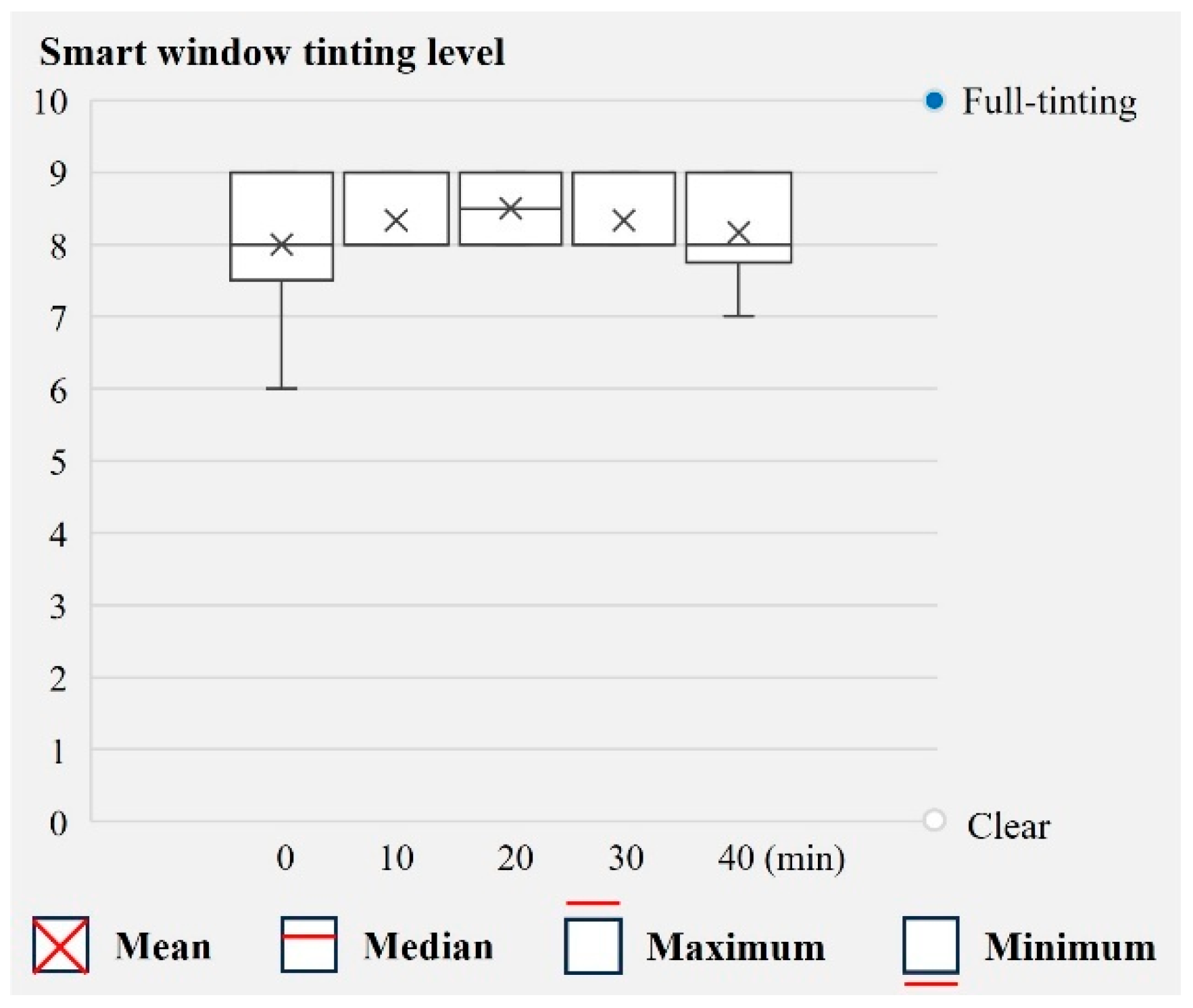

4.5. Experimental Procedures

4.6. Data Processing and Analysis

5. Results

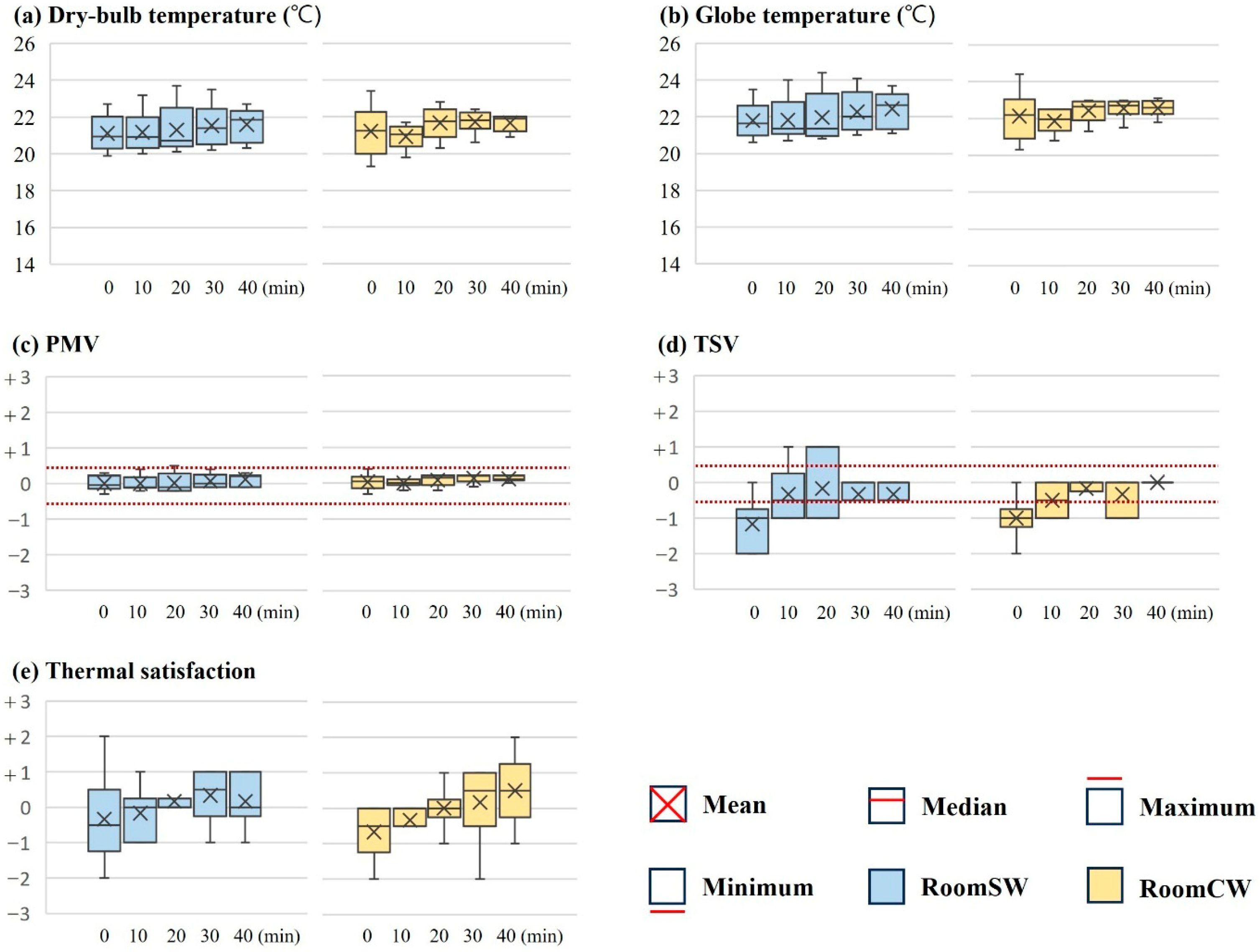

5.1. Thermal Comfort

5.1.1. Dry Bulb and Globe Temperatures

5.1.2. Thermal Sensation

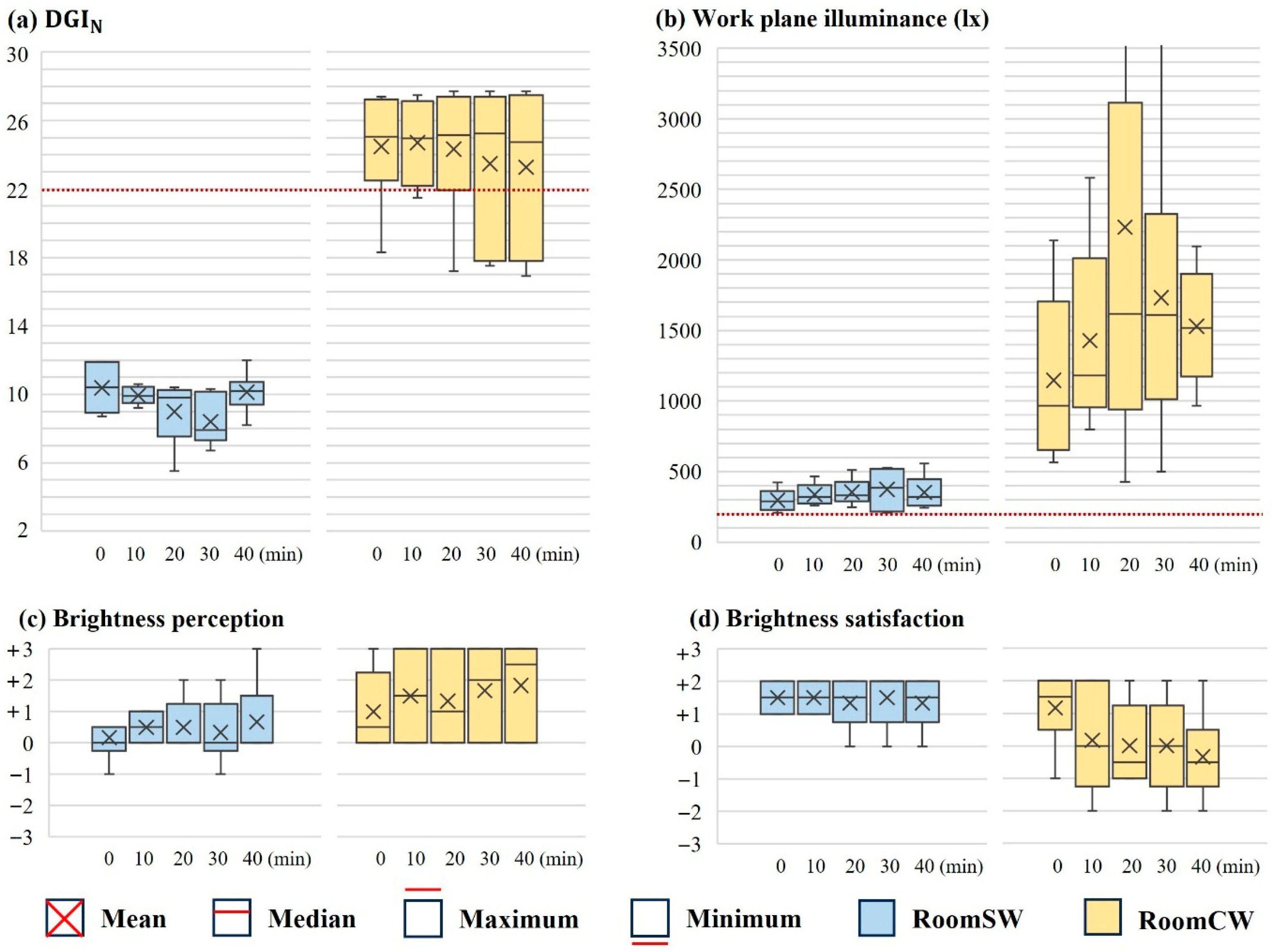

5.2. Visual Comfort

5.2.1. Glare

5.2.2. Indoor Illuminance

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- With respect to thermal comfort, the heating system was controlled to maintain the PMV within the target range of ±0.5 throughout the occupied period. Under this controlled thermal condition (with dry-bulb and globe temperatures maintained within the corresponding operating ranges), the occupant survey results indicated no substantial differences between RoomSW and RoomCW in terms of thermal sensation and satisfaction when applying the smart-window glare prevention tint control strategy in test spaces replicating an actual dwelling. The results of the paired-samples t-test confirmed that the differences between RoomSW and RoomCW were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Therefore, wintertime smart window tinting for glare prevention did not impair the thermal sensation or satisfaction of occupants.

- With respect to visual comfort, glare did not occur in RoomSW, whereas in the RoomCW, the DGIN exceeded 22, indicating the occurrence of glare. For the indoor illuminance, both RoomSW and RoomCW satisfied the minimum required illuminance of 200 lx. According to the occupant survey results, the participants were satisfied with the luminous environment in both RoomSW and RoomCW, with higher levels of satisfaction in RoomSW. These findings were confirmed to be statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Energy Agency. The Energy Efficiency Policy Package: Key Catalyst for Building Decarbonisation and Climate Action—Analysis—(n.d.). Available online: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/the-energy-efficiency-policy-package-key-catalyst-for-building-decarbonisation-and-climate (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Anand, V.; Kadiri, V.L.; Putcha, C. Passive buildings: A state-of-the-art review. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 2023, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito-Coimbra, S.; Aelenei, D.; Gloria Gomes, M.; Moret Rodrigues, A. Building Façade Retrofit with Solar Passive Technologies: A Literature Review. Energies 2021, 14, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favoino, F.; Loonen, R.C.G.M.; Michael, M.; Michele, G.D.; Avesani, S. 5—Advanced fenestration—Technologies, performance and building integration. In Rethinking Building Skins Transformative Technologies and Research Trajectories; Gaparri, E., Brambilla, A., Lobaccaro, G., Goia, F., Andaloro, A., Sangiorgio, A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: London, UK, 2022; pp. 117–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMARC Group. Smart Window Market Report by Technology, Type, Application, and Region; IMARC Group: St. Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 2024–2032. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, H.; Moret, A.R.; Aelenei, D.; Gomes, M.G. Literature review of solar control smart building glazing: Technologies, performance, and research insights. Build. Environ. 2025, 274, 112784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidzadeh, Z.; Heidari Matin, N. A Comparative Study on Smart Windows Focusing on Climate-Based Energy Performance and Users’ Comfort Attributes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesloub, A.; Ghosh, A.; Touahmia, M.; Albaqawy, G.A.; Alsolami, B.M.; Ahriz, A. Assessment of the overall energy performance of an SPD smart window in a hot desert climate. Energy 2022, 252, 124073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangir, M.H.; Aboutorabi, R. Comparison of energy consumption and life cycle assessment in a building equipped with smart windows (electrochromic, thermochromic and photochromic): Case study in Tehran. Results Eng. 2026, 29, 108878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatibi, A.; Jahangir, M.H.; Astaraei, F.R. Energy and comfort evaluation of a novel hybrid control algorithm for smart electrochromic windows: A simulation study. Sol. Energy 2022, 241, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, R.F.D.; Festa, V.; Gigante, A.; Ruggiero, S.; Vanoli, G.p. The incidence of smart windows in building energy saving and future climate projections. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Choi, S.Y.; Song, S.Y. Suspended Particle Device Windows in Residential Buildings: Measurement-based Assessment of Comfort and Energy Performance for Optimal Control in Intermediate and Heating Season. Energy Build. 2024, 330, 115339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Norton, B.; Duffy, A. Daylighting performance and glare calculation of a suspended particle device switchable glazing. Sol. Energy 2016, 132, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 7730; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment. International Organization for Standardization: Vernier, Switzerland, 2005.

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020.

- Fanger, P.O.; Toftum, J. Extension of the PMV model to non-air-conditioned buildings in warm climates. Energy Build. 2002, 34, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Commission on Illumination (CIE). International Lighting Vocabulary, 4th ed.; (CIE 17.4-1987); CIE Central Bureau: Vienna, Austria, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Osterhaus, W.K.E. Discomfort glare assessment and prevention for daylight applications in office environments. Sol. Energy 2005, 79, 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clear, R. Discomfort glare: What do we actually know? Light. Res. Technol. 2013, 45, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, R.G. Architectural Physics: Lighting; HMSO: London, UK, 1963; pp. 225–242. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvel, P.; Collins, B.; Dogniaux, R.; Longmore, J. Glare from windows: Current views of problem. Light. Res. Tech. 1982, 14, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzal, A.A. A new daylight glare evaluation method, Introduction of the monitoring control and calculation method. Energy Build. 2001, 33, 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzal, A.A. A new evaluation method for daylight discomfort glare. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2005, 35, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Standards Association. KS A 3011: Recommended levels of illumination. In Korean Industrial Standards; Korean Standards Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Meteorological Administration. KMA Weather Data Service, Open MET Data Portal. Available online: https://data.kma.go.kr/resources/html/en/aowdp.html (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- World Meteorological Organization. World Weather Information Service, Definition of Oktas. Available online: https://worldweather.wmo.int/oktas.htm (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Matuszko, D. Influence of the extent and genera of cloud cover on solar radiation intensity. Int. J. Climatol. 2012, 32, 2403–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, N.; Schiavon, S. Experimental evaluation of thermal comfort, SBS symptoms and physiological responses in a radiant ceiling cooling environment under temperature step-changes. Build. Environ. 2022, 224, 109512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association (WMA). WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. In Proceedings of the 64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, 16–19 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hajialiani, S.; Rostami, F.; Ahmadvand, M.; Mirakzadeh, A.A.; Azadi, H. Assessment of effect size and social indicators sustainability in the context of international rural development projects in Iran: Using BACI framework. ESI 2025, 27, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Guo, Z.; Liu, Y.; Han, N.; Song, J.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Sheng, C.; Balmer, L.; Li, H.; et al. Tissue-specific distribution of microplastics in human blood and carotid plaques: A paired sample analysis. Environ. Int. 2025, 203, 109743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Altan, H. A comparison of occupant comfort in a conventional high-rise office block and a contemporary environmentally concerned building. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin, M.F. Bridging theory and practice: Enhancing pharmacology education through simulation-based learning and statistical analysis training. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2025, 17, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Amin, M.E.K. Core reporting expectations for quantitative manuscripts using independent and dependent t tests, one way ANOVA, OLS regression, and chi square. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2025, 17, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keis, O.; Helbig, H.; Streb, J.; Hille, K. Influence of blue-enriched classroom lighting on students’ cognitive performance. Trends Neurosci. Educ. 2014, 3, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzen, J.; Albers, F.; Marggraf-Micheel, C. The influence of coloured light in the aircraft cabin on passenger thermal comfort. Light. Res. Technol. 2014, 46, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, G.M.; Shipworth, D.T.; Gauthier, S.; Witzel, C.; Raynham, P.; Chan, W. Saving energy with light? Experimental studies assessing the impact of colour temperature on thermal comfort. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 15, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.-H.; Lee, L.; Chiu, Y.-A.; Sun, Y. Effects of correlated color temperature on focused and sustained attention under white LED desk lighting. Color Res. Appl. 2015, 40, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minguillon, J.; Lopez-Gordo, M.A.; Renedo-Criado, D.A.; Sanchez-Carrion, M.J.; Pelayo, F. Blue lighting accelerates post-stress relaxation: Results of a preliminary study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illuminating Engineering Society. The Lighting Handbook, 10th ed.; Illuminating Engineering Society: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mardaljevic, J.; Andersen, M.; Roy, N.; Christoffersen, J. Daylighting metrics: Is there a relation between useful daylight illuminance and daylight glare probability? In Proceedings of the First Building Simulation and Optimization Conference (BSO12), Loughborough, UK, 10–11 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Krarti, M. Energy performance of control strategies for smart glazed windows applied to office buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 45, 103462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemaida, A.; Ghosh, A.; Sundaram, S.; Mallick, T.K. Simulation study for a switchable adaptive polymer dispersed liquid crystal smart window for two climate zones (Riyadh and London). Energy Build. 2021, 251, 111381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iluyemi, D.C.; Nundy, S.; Shaik, S.; Tahir, A.; Ghosh, A. Building energy analysis using EC and PDLC based smart switchable window in Oman. Sol. Energy 2022, 237, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesloub, A.; Ghosh, A.; Kolsi, L.; Alshenaifi, M. Polymer-Dispersed Liquid Crystal (PDLC) smart switchable windows for less-energy hungry buildings and visual comfort in hot desert climate. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 59, 105101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussault, J.-M.; Sourbron, M.; Gosselin, L. Reduced energy consumption and enhanced comfort with smart windows: Comparison between quasi-optimal, predictive and rule-based control strategies. Energy Build. 2016, 127, 680–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsukkar, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Eltaweel, A. Multi-objective optimization of daylighting systems for energy efficiency and thermal-visual comfort in buildings: A review. Build. Environ. 2016, 288, 113921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Value | Thermal Sensation |

|---|---|

| −3 | Cold |

| −2 | Cool |

| −1 | Slightly cool |

| 0 | Neutral |

| +1 | Slightly warm |

| +2 | Warm |

| +3 | Hot |

| DGIN | Level of Glare |

|---|---|

| 16 | Just perceptible |

| 16 18 | Perceptible |

| 18 20 | Just acceptable |

| 20 22 | Acceptable |

| 22 24 | Just uncomfortable |

| 24 26 | Uncomfortable |

| Category | Item | Indicator | Types of Indicators | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Subjective | |||

| Thermal comfort | Temperature | Dry bulb temperature | O | |

| Globe temperature | O | |||

| Thermal sensation | PMV | O | ||

| TSV and thermal environment satisfaction survey | O | |||

| Visual comfort | Glare | DGIN | O | |

| Indoor illuminance | Work plane illuminance | O | ||

| Perceived brightness and brightness satisfaction survey | O | |||

| Outdoor Illuminance (lx) | VT | Smart Window Tinting Level | AC Input (V) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥139,476 | 0.013 | Level 10 (Full-tinting) | 0 V |

| ≥53,330 | 0.034 | Level 9 | 30 V |

| ≥17,270 | 0.105 | Level 8 | 50 V |

| ≥11,700 | 0.155 | Level 7 | 60 V |

| ≥9397 | 0.193 | Level 6 | 70 V |

| ≥7990 | 0.227 | Level 5 | 80 V |

| ≥7284 | 0.249 | Level 4 | 90 V |

| ≥6768 | 0.268 | Level 3 | 100 V |

| ≥6455 | 0.281 | Level 2 | 110 V |

| ≥6254 | 0.290 | Level 1 | 120 V |

| 6254> | 0.333 | Level 0 (Clear) | 220 V |

| Weather Symbols | Oktas | Definition | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 oktas (0/8) | Sky clear (SKC) | Fine |

| 1 okta (1/8) | Few clouds (FEW) | Fine |

| 2 oktas (2/8) | FEW | Fine |

| 3 oktas (3/8) | Scattered clouds (SKT) | Partly cloudy |

| 4 oktas (4/8) | SKT | Partly cloudy |

| 5 oktas (5/8) | Broken clouds (BKN) | Partly cloudy |

| 6 oktas (6/8) | BKN | Cloudy |

| 7 oktas (7/8) | BKN | Cloudy |

| 8 oktas (8/8) | Overcast (OVC) | Overcast |

| Composition | State | U Value | SHGC | VT | |

| Smart window | (Outer glazing) 9SPD-10Ar-5CL (Inner glazing) 5CL-14Ar-5LE | Full tinting | 0.929 | 0.150 | 0.013 |

| Untinting (Clear) | 0.929 | 0.290 | 0.333 | ||

| Conventional window | (Outer glazing) 5CL-12Ar-5LE (Inner glazing) 5CL-12Ar-5LE | - | 0.943 | 0.352 | 0.523 |

| Category | Device | Measuring Range | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal comfort | T&D TR-74Ui | Illuminance 0~130,000 lx | 10~100,000 lx: ±5% (25 °C, 50%RH) |

| Visual comfort | Testo 480 |

|

|

| Mean | Median | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 33.4 | 25.0 | 21.0 | 59.0 |

| Height (cm) | 161.2 | 161.5 | 155.0 | 168.0 |

| Weight (kg) | 55.4 | 54.0 | 47.0 | 68.0 |

| BMI | 21.3 | 20.8 | 19.3 | 24.9 |

| Survey Dates | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12/03 | 12/06 | 12/10 | 12/13 | 12/17 | 12/20 | 12/24 | 12/31 |

| Cloudy | Cloudy | Clear | Cloudy | Clear | Cloudy | Clear | Cloudy |

| Category | Case | Sky Condition | Environmental Condition | Survey Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal comfort | Case WT1 | Clear day | Adjusted to maintain a PMV range of ±0.5 | 12/10, 12/17, 12/24 |

| Visual comfort | Case WV1 | Clear day | Adjusted to maintain a PMV range of ±0.5 | 12/10, 12/17, 12/24 |

| Average | p Value | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal comfort | RoomSW_DT—RoomCW_DT | −0.10 | 0.28 | 0.11 |

| RoomSW_GT—RoomCW_GT | −0.08 | 0.33 | 0.08 | |

| RoomSW_PMV—RoomCW_PMV | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.07 | |

| RoomSW_TSV—RoomCW_TSV | −0.07 | 0.81 | 0.10 | |

| RoomSW_TS—RoomCW_TS | +0.10 | 0.79 | 0.11 | |

| Visual comfort | RoomSW_DGIN—RoomCW_DGIN | −14.49 | <0.001 | 4.00 |

| RoomSW_WPI—RoomCW_WPI | −1271.02 | <0.001 | 1.08 | |

| RoomSW_BP—RoomCW_BP | −1.03 | 0.07 | 0.71 | |

| RoomSW_BS—RoomCW_BS | +1.23 | <0.05 | 1.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Choi, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-J.; Song, S.-Y. Experimental Evaluation of the Impacts of Suspended Particle Device Smart Windows with Glare Control on Occupant Thermal and Visual Comfort Levels in Winter. Buildings 2026, 16, 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020444

Choi S-Y, Lee S-J, Song S-Y. Experimental Evaluation of the Impacts of Suspended Particle Device Smart Windows with Glare Control on Occupant Thermal and Visual Comfort Levels in Winter. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):444. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020444

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Sue-Young, Soo-Jin Lee, and Seung-Yeong Song. 2026. "Experimental Evaluation of the Impacts of Suspended Particle Device Smart Windows with Glare Control on Occupant Thermal and Visual Comfort Levels in Winter" Buildings 16, no. 2: 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020444

APA StyleChoi, S.-Y., Lee, S.-J., & Song, S.-Y. (2026). Experimental Evaluation of the Impacts of Suspended Particle Device Smart Windows with Glare Control on Occupant Thermal and Visual Comfort Levels in Winter. Buildings, 16(2), 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020444