1. Introduction

The production of high-quality, individualized concrete components remains an economic challenge in the construction industry, primarily due to production inefficiencies and an increasing shortage of skilled labor for formwork fabrication. Traditional formwork systems are resource-intensive, costly, and generate substantial material waste, particularly in the case of geometrically complex architectural elements. A large amount of waste is produced because complex, labor-intensive formwork is typically used only a few times before being discarded. Handcrafted solutions, such as wooden formwork, as well as CNC-milled formwork produced from expanded foams or machinable polyurethane/epoxy blocks, fail to meet contemporary demands for improved ecological and economic efficiency. This highlights the urgent need for environmentally friendly and automatable formwork technologies capable of supporting the future production of individualized precast concrete components.

Within the Eurostars Robocrete project, funded by the European Union Horizon 2020 Framework Programme, the research consortium addresses this challenge by developing a closed digital production chain for individualized concrete components without formwork waste. The Institute of Structural Design (ITE) has developed a 100% recyclable wax formwork technology and continues research on wax formwork technology for industrial applications, while Odico A/S (DK) has advanced the finish milling process through toolpath-design-driven surface articulation milling strategies. BNB Beton und Naturstein Babelsberg GmbH (DE) has contributed a specially formulated CO2-reduced concrete designed for shotcrete application on wax formwork. The experimental investigations are conducted and evaluated by ITE at the Digital Building Fabrication Laboratory (DBFL) at TU Braunschweig.

This paper presents the outcomes of these collaborative efforts, demonstrating that the integration of toolpath-design-driven milled wax formwork and robotic shotcrete 3D printing (SC3DP) with CO2-reduced concrete enables a fully automated manufacturing process with substantially increased manufacturing efficiency for one-sided freeform concrete elements. Ecological efficiency is achieved through the use of recyclable wax formwork in combination with CO2-reduced sprayed concrete, while economic efficiency is enhanced by full digitalization and automation of the manufacturing process as well as by toolpath-design-driven milling strategies that significantly reduce finish milling times. Here, the programmed toolpaths intentionally generate visible milling marks that correspond directly to the parametrically defined surface design, transforming what is typically a technical by-product into a controlled design feature.

In parallel, the approach facilitates the production of geometrically complex shapes and refined surface articulation in precast concrete construction.

1.1. Related Works: Sprayed Fiber-Reinforced Concrete on Formwork

Contemporary architecture favors lightweight, high-performance façades, reducing reliance on heavy precast cladding. In response, Pilkington and the UK Building Research Establishment (BRE) introduced Glassfibre Reinforced Concrete (GFRC) in the 1970s, cutting panel thickness from 150 mm to 20 mm and reducing weight by up to 80%. This was achieved by incorporating alkali-resistant glass fibers, enhancing strength and durability while preventing corrosion [

1]. Mostly applied manually rather than through automated systems, GFRC spraying enables uniform application across the surface shape of formwork systems.

Projects like the Broad Museum in Los Angeles (opened 2015) illustrate the potential of combining GFRC spraying on single-sided formworks [

2]. The museum’s façade, composed of 2450 GFRC sprayed façade elements, employed CNC-milled expanded foam formworks to achieve precise geometries and high-quality finishes. Similarly, case studies like the “Smart Slab” (DFAB House ETH Zurich) and “Incidental Space” (Swiss pavilion Biennale 2016) demonstrate how integrating 3D-printed formworks (3DPF) with GFRC spraying can facilitate the production of freeform geometries and customized concrete components [

3].

Manual GFRC spraying is already successfully applied on an industrial scale for complex surfaces. The application of robotic sprayed concrete for single-sided components like façade panels with architectural surface quality remains, until today, mostly underexplored.

At the Institute of Structural Design (ITE), shotcrete 3D printing (SC3DP) [

4,

5,

6,

7] is being investigated within the framework of the Collaborative Research Center TRR277 “Additive Manufacturing in Construction” (AMC) [

8,

9,

10]. In the SC3DP process, fiber-reinforced fine-grained concrete is pumped to a nozzle, where it is ejected at high speed by compressed air to form a conical jet of high kinetic energy. This kinetic energy ensures a monolithic bond between successive layers and enables the integration of reinforcement, which can be placed during the printing process and sprayed over directly. While the robotic SC3DP process has primarily been applied to the fabrication of vertically layered concrete elements, its suitability for producing horizontally oriented double-curved concrete elements in combination with wax formwork has not yet been investigated.

1.2. Related Works: Formwork Technologies for Individualized Concrete Elements

Precast concrete plants already operate fully automated slab circulation systems in which formwork bodies can be customized using magnetic inserts, and component thicknesses can be adjusted through height-adjustable edge formwork. However, these systems are generally limited to the production of flat concrete components, as the rigid steel base plates of the formwork provide little geometric flexibility and are optimized for high repetition rates rather than customized geometries [

11]. Cut-to-form timber and thermoplastic polymers as formwork materials are widely used for producing individualized concrete elements with planar or simply curved surfaces in small series, primarily due to their availability and compatibility with established conventional precast practices. Freeform timber formwork is labor-intensive, requiring skilled workers for formwork manufacturing and formwork assembly [

12], and is characterized by a low potential for automation.

Expanded Polystyrene (EPS) is often used as a formwork material due to its lightweight nature, isotropic properties, and easy CNC millability, making it suitable for detailed designs. When paired with robotic wire or blade cutting, EPS enables precise multi-curved formworks for architectural elements [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Robotically milled double-curved polystyrene formwork was employed in Frank O. Gehry’s New Customs House (completed in 1999), where it was used for House B during the prefabrication of double-curved façade elements. Milled polystyrene formwork was also applied in the project “House within a House” of the “Bodenseekiesel”, enabling the fabrication of thin-walled, fiber-reinforced concrete façade elements mounted on a timber substructure [

11].

Both projects demonstrate the use of robotically milled polystyrene formwork and indicate early approaches toward automated formwork production for geometrically complex concrete elements.

However, formworks based on polystyrene or expanded polystyrene are, due to additionally required coating or concrete residues, typically non-reusable, contributing to large amounts of waste in the precast industry.

Pin bed formworks, which employ adjustable computer-controlled pins and a flexible overlay to create smooth casting surfaces, present an adaptable solution for accommodating multi-curved designs [

17]. These systems integrate seamlessly with digital workflows, allowing for rapid adjustments to meet changing design requirements. However, pin bed formworks are unable to achieve high-resolution detailing, especially for complex and detailed geometries in façade elements.

Advances in additive manufacturing have introduced 3D-printed formworks (3DPF) as an innovative solution in precast concrete production, offering geometric flexibility and material efficiency by enabling thin, customized formworks [

18,

19,

20]. Stay-in-place 3DPF functions as “lost formwork,” eliminating removal processes while integrating designed surface patterns directly into the concrete [

20,

21]. However, layer height resolution limits fine detailing.

Removable 3DPF provides greater precision by allowing smaller layer heights, making it suitable for customized façade elements [

18,

19]. A key example is the Eggshell method, which combines printing and casting to address hydrostatic pressure challenges, enabling the production of thin-walled concrete components [

20,

21]. Another advanced approach involves coated thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) formworks, as seen in the Cadenza free-form stair, offering structural robustness but remaining small in scale [

19]. Despite these innovations, 3DPF faces challenges such as layered textures on non-post-treated formwork surfaces transferring onto concrete surfaces. Additionally, managing hydrostatic pressure during casting remains a key issue, particularly for thin-walled and lightweight formworks.

Cut-to-form timber and thermoplastic polymers such as EPS are commonly treated as disposable formwork once contaminated with coatings, release agents, or concrete residues, contributing to substantial formwork material waste in the precast industry. Because cleaning and reuse are economically impractical, these materials generate substantial formwork waste in the precast industry and raise significant environmental concerns. While numerous newly developed formwork systems claim formwork material recyclability, the specifics often remain uncertain, as contamination with concrete residues and coatings complicates material recycling. It is unclear whether recyclability refers to a theoretical potential or practical implementation and whether the recycled material is specifically reprocessed for formwork production or redirected into general waste recycling streams—practical recycling implementation and lifecycle impact assessments are often lacking.

The Non-Waste-Wax-Formwork Technology, which forms the foundation of the research presented in this paper, represents an advancement in sustainable formwork systems by enabling material reuse within a researched and validated closed-loop formwork material recycling framework [

22,

23,

24,

25]. This approach substantially reduces waste in precast concrete production, aligning closely with sustainability goals. Research conducted at the ITE has identified ConFormWax (CFW) [

26] as a suitable material for this formwork system due to its precision in CNC milling, allowing for the production of high-quality, free-formed concrete components with minimal resource waste.

Unlike conventional formwork and the previously presented formwork systems, the Non-Waste-Wax-Formwork Technology supports the production of both simple and highly complex concrete geometries, offering a combination of high precision, geometric adaptability, and scalability. In previous research at ITE and the Robocrete consortium, wax block production techniques have been investigated to ensure the fabrication of stress-free and crack-free wax blocks, which are essential for precise CNC milling processes [

22].

Challenges persist, including the presence of slightly visible milling grooves on multi-curved wax formwork surfaces and the reliance on a wax-based release agent, which often precludes unique coloration of the demolded concrete surface.

1.3. Related Works: Efficient Robotically Applied Toolpath-Design-Driven Surface Articulation

Although rough milling and planar finishing operations for wax formwork technology have been extensively investigated at ITE [

22,

23,

24,

25], and high levels of efficiency have been achieved through optimized cutting chip volumes, further optimization is required for finishing processes involving intricate and multi-curved geometries. Producing smooth, double-curved surfaces necessitates shorter step-over distances, which substantially increases machining time in order to meet the surface quality requirements of formwork. Consequently, the economic efficiency of conventional finishing strategies for double-curved surfaces remains limited, primarily due to prolonged milling times. This inefficiency arises from restricted tool engagement, as less than 5% of the diameter of a 20 mm ball-nose finishing tool is utilized when milling paths are spaced at intervals below 1 mm. The smaller the required step-over distance to achieve very smooth curved surfaces, the longer the machining process becomes, ultimately leading to milling durations that are economically inefficient. A more efficient approach replaces smooth surfaces with parametrically designed textures, maximizing tool engagement during finishing, similar to traditional woodworking and stone carving. Robotic systems further enhance economic efficiency by converting digitized hand movements into precise robotic motions, enabling the accurate reproduction of complex textures and finishes using traditional tools. In woodworking research, robotic systems have successfully replicated traditional chiseling techniques with high precision [

27]. Moreover, in robotic stone carving, parametric design and automated path-planning algorithms enable robots to apply parametrically designed patterns with reduced labor and processing time, adding new computational design possibilities for stone carving [

28].

Another time-efficient application of robotic subtractive processes is demonstrated in the Armadillo Vault project, where a robotic system equipped with circular saw blades shaped the undersides of the stone voussoirs, and the joints were subsequently milled to high precision using a five-axis CNC machine [

29,

30]. Rather than fully smoothing the surfaces, the process retained cutting paths typically associated with roughening steps, but in this case, used as a finish step aligned with the force flow lines derived from the digital design. This approach minimized machining time while imparting a distinct textural quality to the pavilion’s ceiling, enhancing its aesthetic appeal. Another example of toolpath-driven surface articulation is presented in [

31], where CNC toolpaths are used as generative design elements, demonstrating how milling trajectories can create surface articulation to double-curved cubature.

2. Methodology: Production Process for Freeform Thin-Shell Concrete Elements

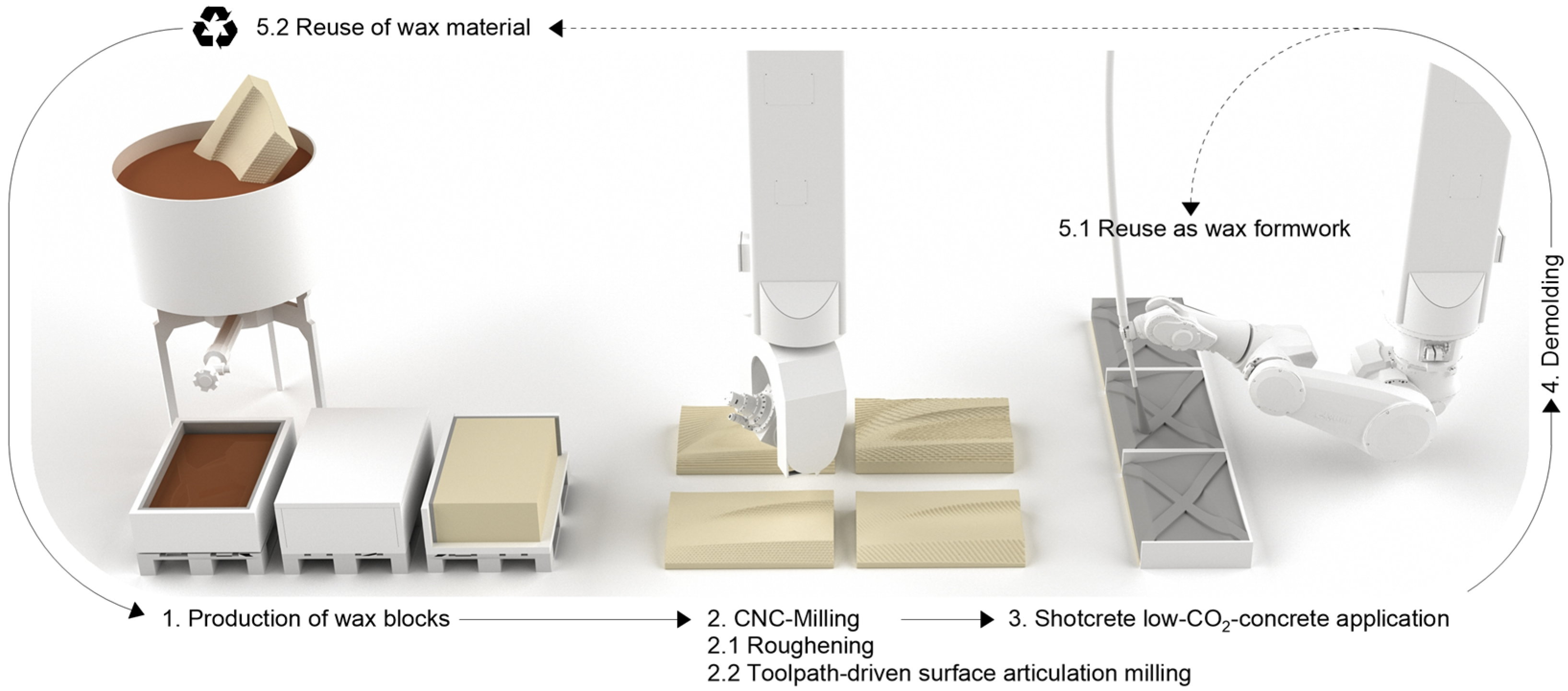

The production process for thin-walled concrete elements, utilizing the combined approach of wax formwork and robotic shotcreting, comprises five steps shown in

Figure 1. In Step 1, wax blocks are produced using a single-stage casting method, with reproducibility tests ensuring consistent quality across repeated production cycles. Once solidified, the blocks are CNC-milled in Step 2, which consists of two sub-steps: in Step 2.1, the blocks are roughly machined to approximate their final contour, followed by Step 2.2, where time-efficient toolpath-design-driven milling strategies are applied to articulate the wax formwork surfaces, allowing for a significant reduction in milling time compared to traditional smooth finishing. Step 3 focuses on the integration of wax formwork technology with shotcrete application, employing a CO

2-reduced, fiber-reinforced, fine-grained concrete specifically designed for robotic shotcrete production. In Step 4, the thin-shell concrete elements are demolded. Finally, in Step 5, two reuse scenarios are possible: in Step 5.1, the wax formwork surface is reused for subsequent shotcrete applications, whereas in Step 5.2, after final use, the wax material itself is recycled by melting the formwork together with milling chips, filtering out contaminants, and reprocessing the recovered wax into new blocks.

Steps 2, 3, and 4 are conducted at the Digital Building Fabrication Laboratory (DBFL) [

32,

33] of the Institute of Structural Design (ITE). Established in 2016, the DBFL functions as a research center for digital construction processes in prefabrication. The laboratory is equipped with a dual-gantry system, each featuring specialized capabilities: one gantry houses a five-axis milling unit for CNC milling, while the other incorporates a six-axis robotic system enabling, for example, additive concrete manufacturing like Shotcrete 3D Printing (SC3DP). The cooperative workspace, measuring 10.5 m × 5.25 m × 2.5 m, enables a seamless digital workflow. This setup supports both the subtractive CNC milling of wax blocks and the additive manufacturing of thin-shell, surface-articulated concrete elements.

2.1. Wax Block Production

In prior research at ITE [

22,

23,

24,

25], the production of large-scale wax blocks proved challenging due to significant residual stresses during cooling, leading to significant deformations. In the Robocrete research, three novel methods for the production of stress-free and crack-free wax blocks were investigated [

22]. One method, the single-stage wax casting under optimized cooling conditions, was further developed for its labor-time efficiency, material efficiency, and suitability for large-format wax block production. In this method, shown in

Figure 2, wax heated to 90 °C is poured into a form constructed from plywood boards. The form is lined with a sliding inner layer, a non-stick paper lubricating layer to prevent the wax from adhering to the interior walls. Additionally, 50 mm polystyrene insulation is applied on the outside on all sides, including a sealed lid to ensure thermal insulation.

For the design studies of the toolpath-design-driven milled concrete elements, four wax blocks were produced using the previously described method to simultaneously confirm and verify the reproducibility. The measurements of the cooled wax blocks deviate from the dimensions of the form used during casting. This discrepancy arises due to the inherent volume contraction of the wax during the cooling phase, a process that is carefully controlled in this method to avoid the formation of cracks and internal stresses.

To practically apply the toolpath-design-driven milling, the four prefabricated wax blocks (~1.2 m × 0.8 m × 0.3 m) are processed to be used in the further steps of the process at the DBFL.

2.2. CNC Milling Operations

Conventionally, a cubature is first modeled and then reproduced as precisely as possible through CNC milling. Although this approach yields high surface quality, conventional finishing, particularly for multi-curved geometries, is extremely time-intensive, with milling time increasing exponentially as smoother surfaces are required. In contrast, the surface design strategies for CNC-milled wax formwork developed in this study pursue two primary objectives: (1) a significant reduction in CNC milling time through surface design approaches that employ the CNC toolpath itself as a generative design element, and (2) the improvement of surface articulation with high visual richness while simultaneously reducing manufacturing time.

To streamline operations, both the rough milling and toolpath-design-driven milling are programmed and modeled using the visual programming language plugin Grasshopper in the 3D CAD software Rhinoceros v7. This integrated digital workflow generates three-dimensional planes oriented along the X, Y, and Z axes, specifying the tool orientation and trajectory in relation to the reference geometry.

The spindle speed and feed rate for the milling process are defined and implemented in the G-code, with:

Rough milling (substep 1) using a cylindrical end mill (80 mm diameter, 40 mm cutting height) at a spindle speed of 4000 rpm and a feed rate of 4000 mm/min.

Rough milling (substeps 2 and 3) using a cylindrical end mill (40 mm diameter, 40 mm cutting height) at a spindle speed of 4000 rpm and a feed rate of 4000 mm/min.

toolpath-design-driven finishing using a ball nose tool (20 mm diameter, 225 mm cutting height) at a spindle speed of 5000 rpm and a feed rate of 4000 mm/min.

2.2.1. Roughening Milling, Preparation for Toolpath-Design-Driven Milling

To prepare the wax blocks for the toolpath-design-driven milling, the rough milling process is conducted in three successive steps to achieve a cubature with a 2 cm offset from the final contour. In the first rough milling sub-step, the wax block is milled into a cuboid to eliminate the irregular edges and surfaces that occur due to the free volume contraction during the cooling process, shown in

Figure 3a.

In the second 3-axis rough milling sub-step, the tool operates along three linear axes (X, Y, Z) with fixed rotational axes, maintaining perpendicularity to the bottom surface and removing material in 2 cm vertical increments, which ensures high material removal rates while preserving geometric accuracy and progressively approaching the final contour shown in

Figure 3b.

In the third 5-axis rough milling sub-step, all three linear axes and both rotational axes are used to refine the surface by smoothing the coarse steps created in the previous sub-step. Here, the milling path distance is reduced to 1 cm, producing a cubature close to the final contour while maintaining the required 2 cm offset for subsequent toolpath-design-driven milling shown in

Figure 3c. This refined cubature provides the necessary foundation for the precise application of toolpath-driven milling design strategies.

2.2.2. Milling Time Efficiency Improvement and Surface Articulation Through Toolpath-Design-Driven Milling

For this part of the study, four parametric design strategies were developed that generate surface articulation through toolpath-driven designs. Following a top-down design strategy, a basic cubature with double curves and sharp edges was defined as the reference geometry; in this hierarchical approach, the global form is established first, and subordinate features and manufacturable surface patterns, such as the surface articulation by toolpath-design-driven milling introduced here, are derived from it. Although demonstrated on a single cubature, the strategies are transferable to a wide range of geometries. In contrast to conventional finishing operations, the toolpaths are intentionally used as design features rather than being minimized or removed. By fully exploiting the milling tool’s diameter, toolpath spacings greater than 20 mm can be employed instead of the sub-millimeter intervals typical of conventional finishing, resulting in substantial reductions in machining time. Parametric control of the milling paths allows precise and customizable surface articulation to be generated, applicable to both multi-curved and planar geometries, while maintaining the basic cubature as a fixed boundary condition. The digital design workflow mirrors the physical milling process to ensure a direct and accurate translation of the virtual model into the physical wax formwork. Corresponding waypoints are generated in a Grasshopper script [

26] shown in

Figure 4a, guiding the milling tool to follow the programmed surface trajectory of the cubature shown in

Figure 4b. The X, Y, and Z planes define the path of the ball-nose cutter, which executes the programmed sequence, thereby structuring the surface with intentional milling marks as a design feature.

To evaluate both the milling process and the resulting surface design, the waypoints are first simulated within the digital model. A subtractive Boolean operation simulates material removal from the digital reference geometry, producing a virtual digital twin of the wax formwork. This digital twin serves as a critical tool for assessing the designed surface structure before physical milling, enabling iterative refinement and optimization of the milling strategy and design. The investigation examines four design strategies: (a) linear surface articulation, (b) crossed surface articulation, (c) typology-adapted curve flow surface articulation, and (d) typology-adapted drilling chisel surface articulation, each resulting in a unique surface structure on the wax formwork. The time savings achieved by the toolpath-design-driven milling strategies are assessed by evaluating both the tool travel time and the effective milling time resulting from the toolpath distances and are subsequently compared with those of conventional CNC finishing strategies.

(a) Linear surface articulation: The linear surface articulation utilizes a ball-nose end mill oriented at a 45° angle relative to the short edge of the wax block. The milling process aligns with the Z-values of the reference cubature surface, enabling the tool to mill the wax block in a linear pattern parallel to the reference cubature. The milling paths are spaced at 2 cm intervals, measured from the center of the ball-nose cutter, producing grooves that are 1 cm deep and 2 cm wide, as shown in

Figure 5a,b.

(b) Crossed surface articulation: The crossed surface articulation is an extension of the linear surface articulation design, incorporating a secondary milling pass oriented at 90° to the linear milled grooves. This additional pass generates a crossed, intersecting pattern on the wax block surface shown in

Figure 6a,b.

(c) Topology-adapted curve flow surface articulation: This strategy adapts to the natural curve flow of the reference cubature, creating a dynamic interplay of groove density. Milling tracks overlap in areas where the center-point distance between consecutive paths is smaller than the diameter of the ball-nose cutter, increasing the density of the milling grooves. Conversely, in regions where the center-point distance exceeds the cutter diameter, the surface retains elements of the rough milling process, resulting in reduced groove density, shown in

Figure 7a,b. This variation in path spacing strengthens the reference cubature’s topology by highlighting its curves and lines, offering a nuanced surface design.

(d) Robotic drill topology-adapted surface articulation: Inspired by traditional woodworking techniques, the robotic drill topology-adapted surface articulation involves the milling tool plunging into the wax cubature’s surface in a curved entry motion and exiting tangentially with a similarly curved trajectory. This produces milled cavities distributed along the reference cubature surface. Similarly to the topology-adapted curve flow surface articulation, this pattern features varying milling path spacing, creating areas of local overlap and untouched regions. These variations follow the lines and contours of the reference cubature, adding a distinctive character to the surface while emphasizing the topology shown in

Figure 8a,b.

The surface articulation design strategies of the linear and crossed designs effectively maintain alignment with the basic cubature by adapting the Z-values to the reference geometry with a fixed rotational axis. The topology-adapted curve flow and robotic drill topology-adapted surface articulation not only follow the Z-value adjustments of the reference geometry but also align with its topological lines, allowing rotation in the axis while enhancing the definition and emphasis of the basic cubature through strategic variations in milling track density and spacing.

These finishing milling strategies reduce the milling time significantly compared to conventional smoothing milling methods with small milling path distances. The significantly reduced milling times of the toolpath-design-driven milling strategies are compared to conventional milling methods, and the quality of the resulting wax formwork surfaces is evaluated both visually and haptically in

Section 3.2.

2.3. Concreting with Low-CO2 Concrete Using Manual and Automated Shotcrete Methods

This process step addresses the concreting of toolpath-design-driven milled wax formworks using two shotcreting techniques: (a) manual application on uncoated wax formwork treated with a wax-based release agent and (b) automated robotic application on coated wax formwork treated with a mineral-oil-based release agent. In approach (a), the focus lies on testing the sprayability of the developed fine-grained concrete and verifying the compatibility of wax formwork with SC3DP technology. In approach (b), wax formwork surface coatings are investigated with the aim of improving the quality of wax formwork for architectural concrete applications, while the concreting process itself is carried out robotically. Both approaches employ a fine-grain concrete formulated with Celitement binder, which is characterized by reduced CO

2 emissions [

22,

23,

24,

25].

2.3.1. Concrete Material Testing with Manual Shotcreting (a) on Uncoated Wax Formwork

The fine-grain concrete mix [

26] presented in

Table 1 was specifically designed for shotcrete applications on wax formwork, incorporating fibers for reinforcement and a maximum aggregate size of 4 mm, which is required for the shotcrete process to enable pumpability. The mix utilizes Celitement as a CO

2 emission-reduced alternative to conventional Portland cement. Celitement is a clinker-free hydraulic binder developed as an alternative to Portland cement. Produced currently at pilot scale, it offers a significantly reduced environmental impact, with a gross GWP approximately 40% lower than gray cement clinker and 50% lower than white clinker. This reduction results from a lower-carbon raw material basis, containing about 30% less calcium, and a largely electrified production process that replaces the rotary kiln with a stirred media mill. Celitement concretes can be recycled similarly to conventional concretes, during which part of the previously emitted CO

2 can be chemically re-bound. The material meets strength class 52.5 R and exhibits a dense lamellar C–S–H microstructure with low permeability and high durability [

34,

35,

36,

37]. The mix was formulated to provide enhanced properties essential for shotcrete applications, including improved stickiness for adhesion and increased green strength to maintain stability during application. The spreadability of the mix was calibrated to approximately 46 cm according to EN 12350-5 [

38], a measure of consistency and workability for shotcrete application. The binder content was aligned with traditional shotcrete formulations to ensure performance equivalence while maintaining a reduced CO

2 profile. Alongside the concreting tests, the concrete’s compressive strength is tested according to DIN 1045-3 [

39].

The process step of manual shotcrete investigations on toolpath-design-driven milled wax formwork focused on evaluating the performance of the developed low-CO

2 concrete for shotcrete application and the compatibility of high-kinetic shotcreting with wax formwork, ensuring that the formwork surface remained undamaged. Additionally, the step aims to determine optimal shotcrete parameters, including the nozzle-to-surface distance. The wax surfaces were treated with a wax-based release agent (Pieri Cire LM-33) [

26] to facilitate the demolding process—no additional coatings were applied to assess the robustness of the wax formwork when directly exposed to shotcreting. Concrete was applied in successive layers, achieving a uniform thickness of approximately 4 cm, shown in

Figure 9a,b. Anchors embedded within the concrete layers facilitated the demolding process shown in

Figure 9c.

2.3.2. Coated Wax Formworks and Robotic Automated Shotcreting (b)

The application of coatings on wax formwork surfaces aims to improve wax formwork surface smoothness, enable the use of mineral-oil-based release agents commonly employed in the precast industry for exposed concrete components, and prevent oil diffusion into the wax to maintain recyclability and release performance. From an initial pool of 22 coatings, three coatings were selected for further evaluation. The adhesion potential was assessed indirectly by determining the surface energy of uncoated CFW-wax using the Owens–Wendt–Rabel–Kaelble (OWRK) method with a contact Angel System (OCA), Data Physics Instruments, Filderstadt, Germany. Contact angles of water (51 mN/m) and diiodomethane (0 mN/m) were measured on milled wax samples (200 mm × 200 mm × 40 mm) at four positions to account for local variation. These measurements enabled calculation of the polar and dispersive components of surface energy, providing insights into the expected adhesion behavior of coatings on wax substrates. The selected coatings [

26]—a blue one-component system (Coating 1), a transparent one-component system (Coating 2), and a white/gray two-component system (Coating 3)—were applied in two layers with a compressed-air spray gun. The first layer acted as a primer, while the second ensured full coverage after drying, with a total application rate of ~200 g/m

2 across both layers shown in

Figure 10a–c.

The coated wax blocks were then used for the automated robotic shotcrete with the same low-CO2-concrete mix that was used in the material tests with manual shotcreting. Three nozzle movement strategies were considered and dry-tested for trajectory planning: (i) long-side to long-side, (ii) short-side to short-side, and (iii) diagonal movement. Additionally, nozzle inclination relative to the surface normal (90°) was considered. For the experiments, the short-side-to-short-side movement with fixed nozzle inclination was selected, as it provided the most uniform application, enabled consistent parameter control, and at the same time prevented unnecessary robot movements that could otherwise lead to non-uniform concrete coverage.

The three coated wax formwork surfaces were treated with the mineral oil-based release agent (SOK Ultra) [

26] before shotcreting was conducted. Fine-grain concrete was deposited in successive layers along a linear trajectory using the shotcrete parameters from the manual shotcrete tests, with the nozzle positioned at an inclination of 85° and a distance of 40 cm from the surface. This fixed inclination ensured coverage of all edges while minimizing path inefficiencies. The nozzle traversed horizontally short-side to short-side with a path spacing of 14.2 cm, spraying layers with a final thickness of ~4 cm. A constant spraying velocity ensured uniform deposition and compaction, as shown in

Figure 11c. After application, stiffening crosses (4 cm height, 14 cm width) were printed on the rear side of the element shown in

Figure 11d, with anchors embedded to facilitate demolding and enable structural integration.

3. Results

3.1. Reproducibility of Wax Block Production Method and CO2 Savings by Wax Recycling

The single-step casting method under optimized cooling conditions enabled the production of four wax blocks with dimensions of 1.2 m × 0.8 m × 0.3 m. This highly labor-efficient method required just 1 h of mold preparation, enabling the rapid commencement of wax block production. The short preparation time significantly improves the feasibility and scalability of the method. The 8-day cooling phase reduced the wax temperature from 90 °C to 25 °C (approximately 5 °C above room temperature). This controlled cooling approach enabled the production of wax blocks free of cracks and internal stresses, with no observable warping (corner lifting), an indication of no stresses in the wax blocks. These results indicate uniform contraction and stress-free solidification, making the blocks ideal for precision milling applications. Two key factors contributed to the consistent, crack-free results:

Uniform cooling rate: Insulating all six sides of the mold (achieving a U-value of 0.581 W/m2K) and sealing the opening to balance heat transfer, allowing wax molecules to gradually align into a crystalline structure. This process significantly reduces stress and ensures homogeneity. This method prevents uninsulated casting surfaces from cooling faster than the inner mold, leading to uneven solidification, internal stresses, and cracking.

Free volume contraction: A lubricating layer—such as non-stick paper—prevents wax adhesion, allowing free contraction and tension-free cooling. This method prevents wax adhesion to the form’s inner walls, restricting contraction, generating stress that deforms the block during milling.

This labor-efficient and reliable casting method, combined with its capacity to produce stress-free wax blocks, highlights its suitability for the mass production of high-quality wax blocks for milling and concrete applications. The results confirm process reproducibility, ensuring consistent performance in subsequent manufacturing stages.

While materials such as expanded polystyrene 24 kg/m

3 (EPS) [

40], polyurethane 700 kg/m

3 (PU) [

41], or unexpanded polymers such as polyoxymethylene 1410 kg/m

3 (POM) [

42] can typically be used only once as formwork and must subsequently be downcycled or disposed of as special waste, CFW wax has been demonstrated to withstand at least 200 melting cycles and can be reused accordingly as a formwork material. Indications even suggest a possible reuse potential of up to 500 melting cycles.

Although the exact composition of the CFW wax mixture is proprietary and not publicly accessible, paraffin 900 kg/m

3 is the main constituent. Considering CO

2 emissions associated with producing the primary materials, paraffin-based wax appears initially disadvantageous, with approximately 3375 kg CO

2/m

3 [

43,

44], compared to EPS (70 kg CO

2/m

3) [

40,

45], PU 700 (2450 kg CO

2/m

3) [

41,

46], and POM solid material (4570 kg CO

2/m

3) [

42,

47].

Taking the recycling of the formwork material into account, the effective CO2 emissions per cubic meter of usable formwork material are substantially reduced. For CFW wax (paraffin), these emissions decrease to approximately 17 kg CO2/m3, assuming 200 melting cycles, and to 7 kg CO2/m3, assuming 500 melting cycles. With a reuse rate of 200 cycles, the effective CO2 emission rate of the wax is approximately 4 times lower than that of EPS 100, which is characterized by particularly low production-related CO2 emissions due to its very low density of 20 kg/m3 (compared with approximately 900 kg/m3 for paraffin). At a reuse rate of 500 cycles, the effective CO2 emissions of the wax become roughly ten times lower than those of EPS 100.

3.2. Toolpath-Design-Driven Milled Wax Formwork Surface and Milling Time Comparison of Toolpath-Driven Finishing and Conventional Smoothing

The applied toolpath-design-driven milling strategies enabled the precise translation of digital designs into physical milled wax formworks, emphasizing the topology of the basic cubature and adding surface definition through controlled milling paths. This approach introduced textural variation while maintaining functionality, with digital modeling ensuring design alignment and reproducibility, as shown in detail in

Figure 12a–d.

In the linear surface articulation, minor interferences were observed between the rough milling and toolpath-driven finishing milling steps. These inconsistencies were due to an insufficient offset from the reference geometry during rough milling, which necessitated additional adjustments to improve the transition to the toolpath-design-driven milling. The interferences were localized in specific areas, particularly between grooves, but did not significantly affect the molded concrete components, as they remained confined to deeper regions of the thin-shell concrete elements and were visually negligible.

The analysis of the two topology-adapted surface articulations revealed minor interferences in areas where the milling path density was lower than the diameter of the ball-nose milling head. This reduction in path density resulted in sections where the roughened surface from the previous milling step became slightly visible. Specifically, the 1 cm stepover traces from the rough milling phase were not fully eliminated during the finishing step and remained faintly noticeable on the wax formwork surface.

The study compared four toolpath-design-driven milling strategies to conventional smoothing methods, using consistent travel and milling speeds of 4000 mm/min. Conventional smoothing with 0.5 mm and 1 mm stepover distances served as the baseline, highlighting their time-intensive nature. The 0.5 mm stepover required 517.79 min (8:37:47 h), while increasing the stepover to 1 mm reduced processing time to 260.29 min (4:20:17 h), calculated in Grasshopper Build 1.0.00007, with minor discrepancies attributed to motor deceleration and acceleration during transitions.

The linear surface articulation finishing milling strategy was the most time-efficient, completing in 29 min with significant time savings of 94% and 89% compared to 0.5 mm and 1 mm smoothing, respectively.

The crossed surface articulation finishing milling strategy, featuring a more complex overlapping path, required 59 min—twice as long as the linear diagonal but still achieving reductions of 89% (0.5 mm) and 77% (1 mm). It demonstrated suitability for applications requiring increased surface detail.

The topology-adapted curve flow surface articulation finishing milling strategy achieved a processing time of 30 min, only slightly longer than the linear diagonal strategy, with reductions of 94% (0.5 mm) and 88% (1 mm) compared to conventional smoothing. It offered a balance of efficiency and moderate surface complexity.

The robotic drill topology-adapted surface articulation finishing milling strategy, the most intricate strategy, required 60 min due to its longer milling paths. Despite the increased time, it still achieved reductions of 89% (0.5 mm) and 77% (1 mm) compared to conventional smoothing while providing the highest potential for surface detail and design richness.

In summary, all toolpath-design-driven milling strategies significantly reduced processing times compared to conventional smoothing, as shown in

Figure 13. The linear diagonal surface articulation and topology-adapted curve flow surface articulation proved most time-efficient, while the cross-over weave and drilling chisel strategies offered more detailed designed surface structures.

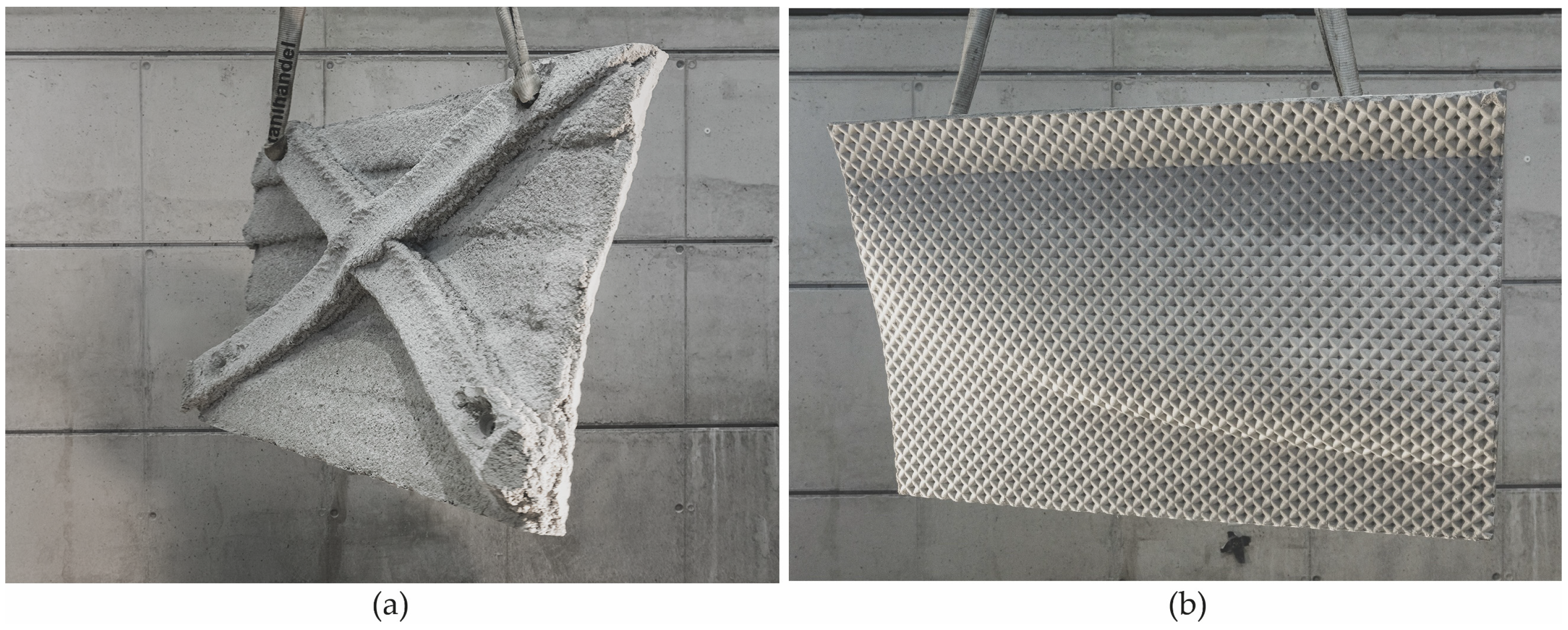

3.3. Demolding Process and Final Result

The demolding process of the manually shotcreted thin-shell concrete elements was conducted after a curing period of 24 h, as shown in

Figure 14a,b. To ensure stability during separation, the wax formwork was fixed to the underground of the DBFL. The thin-shell concrete elements were lifted using a gantry crane attached to the anchors embedded in the rear side of the panels. High-pressure air was injected between the concrete and the wax formwork surfaces to reduce adhesion forces, facilitating clean detachment. Three of the four toolpath-design-driven milled wax formwork surfaces remained undamaged during demolding, confirming their robustness and suitability for reuse. However, the formwork made by chisel-drilled surface articulation design sustained damage due to undercuts in its geometry, which impeded clean separation and rendered the formwork unsuitable for reuse in a robotic shotcreting application. The corresponding thin-shell concrete element, shown in

Figure 14c, developed cracks during demolding. The damaged wax formwork was melted and repurposed into new wax blocks. Despite the high kinetic energy of the manual shotcreting process, no visible damage was observed on the other wax formwork surfaces, confirming their resilience for the shotcrete application.

The demolding process of the robotically shotcreted thin-shell concrete elements was also performed after 24 h, using the same high-pressure air injection technique. The process yielded a homogeneous, high-quality concrete surface with improved coloration and smoothness compared to the manually shotcreted panels. These findings are further analyzed in

Section 3.4. The rough rear surface shown in

Figure 15a, resulting from the shotcrete process, is sufficient for its intended purpose, as these panels are typically mounted as, for example, façade panels against a wall, eliminating the need for high precision on the rear side. The front side exhibits a high-quality concrete surface with high precision surface articulation shown in

Figure 15b and

Figure 16.

The robotic shotcrete process proved highly compatible with the milled wax formwork, exhibiting no visible damage to wax formwork surfaces despite the high kinetic energy of the shotcrete application. The compressive strength tests for the low-CO

2 fiber-reinforced concrete, formulated with Celitement as the binder, a maximum aggregate size of 4 mm, and fiber reinforcement, were conducted in compliance with DIN 1045-3 standards [

26]. The tests spanned multiple curing ages (3, 7, and 28 days), with consistent specimen dimensions and controlled conditions. Overall, the compressive strength results confirm that the low-CO

2 concrete mix with Celitement fulfills the requirements for C30/37 concrete and demonstrates high reliability and environmental benefits in structural applications.

3.4. Coating Adhesion on Toolpath-Design-Driven Milled CFW-Wax Formwork and Concrete Surface Quality in Comparison of Coated and Uncoated Wax Formwork Surface

Coating 1, characterized by its blue coloration, is easy to apply and allows for uniform thickness due to its visibility on the wax surface. The coating forms a smooth, glossy surface, with no dissolution observed when paired with the SOK Ultra release agent. However, small droplets tend to form during application, and a slightly thicker layer of the coating accumulates due to gravity, as shown in

Figure 15b. During demolding, the coating detaches with the wax formwork, and its adhesive properties enable only a single repeated concreting per application. Residual coating can be easily removed from both the wax formwork and the concrete surface using compressed air. Additionally, the coating can be filtered out of the melted wax as a “skin” during recycling, ensuring the integrity of the wax material system. In comparison to the coarse, porous, and partially discolored concrete surface observed using the wax-based release agent on the uncoated wax surface shown in

Figure 17a, the concrete surface resulting from wax formwork coated with Coating 1 is smooth, glossy, and free from discoloration, as shown in

Figure 17c. However, the small droplets of coating formed during application result in an uneven, imperfect concrete surface after demolding, slightly compromising the uniformity of the finish. Despite this limitation, Coating 1 remains a suitable option for achieving improved exposed concrete quality in single-use applications. To prepare the wax formwork for subsequent concreting, the coating must be entirely removed and reapplied.

Coating 2, the transparent coating, was also easy to apply, although its lack of color makes it challenging to determine coated areas during application. Light refraction and reflections suggest an uneven coating layer, but this unevenness is not discernible to the touch and results in a surface that feels smooth, with no visible droplet formation or accumulation in milling grooves shown in

Figure 18b. The coating exhibits compatibility with the SOK Ultra release agent, adhering well to the wax formwork without detachment during the concrete shotcrete process. Upon demolding, the coating remains mostly intact but shows minor peeling at the corners of the wax formwork. This minor peeling can propagate further during subsequent concreting, restricting its durability to a maximum of two/three repeated concreting before complete removal and reapplication become necessary. Despite this limitation, the concrete surface resulting from Coating 2 is glossy, smooth, and free from discoloration, as shown in

Figure 18c, representing a significant improvement compared to the coarse, porous, and partially discolored surfaces observed when using a wax-based release agent on a wax formwork surface, shown in

Figure 18a. Furthermore, the coating residues can be effectively removed during wax recycling, as they can be filtered out as a “skin,” preserving the recyclability of the wax material system.

Coating 3, a two-component white/gray coating, exhibits lower viscosity compared to other tested coatings, resulting in less precise application. This characteristic leads to uneven thickness across the wax formwork surface shown in

Figure 19b, which is subsequently mirrored on the molded concrete surface. Despite this, the concrete surface produced using this coating is smooth and shiny, as shown in

Figure 19c, marking a notable improvement over the coarse, porous, and partially discolored surface observed when utilizing a wax-based release agent on an uncoated wax formwork surface, as shown in

Figure 19a. However, during demolding, the coating detaches from the wax formwork, leaving residues on both the wax formwork and the concrete surface. This detachment limits the coating’s suitability to single-use applications similar to Coating 1.

The results of the OWRK tests highlight the inherent challenges of coating CFW wax due to its predominantly non-polar nature, which presents significant obstacles for coating adhesion. Measurements revealed a water droplet contact angle of 92.01° (±1.32°) and a diiodomethane droplet contact angle of 68.4° (±0.92°) on the CFW wax surface. These values were used to calculate the free surface energy of the wax as 26.77 mN/m (±0.94 mN/m), comprising a dispersive component of 23.77 mN/m (±0.52 mN/m) and a polar component of only 3 mN/m (±0.42 mN/m). This confirms the wax surface’s highly dispersive and low polar energy characteristics, reflecting its nonpolar properties. The dominance of the non-polar component creates a barrier to effective wetting and adhesion, complicating the application and durability of coatings on the wax surface.

4. Discussion and Future Work

The investigations presented in this study show that the combination of wax formwork technology and robotic shotcreting enables a digital, automated, and materially efficient workflow for producing thin-walled, free-formed concrete elements. Economic efficiency is increased through toolpath-design-driven milling strategies and reduced manual labor, ecological efficiency is enhanced through the closed-loop use of wax and the application of low-CO2 concrete, and architectural surface quality is improved through targeted coating systems.

Economic Efficiency—toolpath-design-driven milling surface articulation and digital, automated workflow: The combination of subtractively manufactured, recyclable wax formwork and robotic shotcreting establishes a fully digital and automated production workflow for thin-walled, free-formed concrete elements. This integrated process reduces labor requirements, shortens production time, and enhances overall economic efficiency. A major contributor to this efficiency is the substantial reduction in finishing-milling time achieved through toolpath-driven surface articulation strategies, which simultaneously enrich the visual texture quality of the wax formwork surface. Toolpath-design-driven surface articulation milling strategies enable design features and visually expressive and customizable surface textures that extend beyond conventional smooth formwork surfaces. By eliminating the need for dense sub-millimeter finishing passes typically required for complex geometries, these strategies yielded milling-time reductions of up to 94% in this study.

This approach is particularly suited for one-sided concrete elements used in façade applications, where only the exposed face requires architectural concrete quality, while the rough shotcrete backside is sufficient for structural mounting. Future research could explore additional application fields that require only a single exposed surface, such as force-flow-optimized ceiling slabs, following the same digital workflow. Further work could expand the parametric milling strategies introduced here, enabling continuous surface articulation across multi-module façade systems, and accommodate a broader range of geometries while avoiding undercuts to support repeated concrete casting cycles.

Ecological efficiency—through close-loop-wax formwork: The single-stage wax casting method is a proven, repeatable method for the production of homogeneous, crack-free wax blocks with only one hour of preparation time but eight days of cooling. However, cooling time increases exponentially with block size, making durations beyond 14 days impractical for precast-industry workflows. As a result, the method is effectively limited to pallet-sized blocks. Future research will therefore focus on 3D-printed wax foam blocks, which represent a highly promising alternative to massive cast wax blocks. In this approach, near-net-shape wax blocks are rapidly printed at a rate of approximately 50 kg/h and subsequently milled with high precision once cooled. This hybrid method combines the advantages of both additive and subtractive manufacturing while mitigating their respective drawbacks. Additive wax-foam manufacturing could significantly reduce the amount of wax that must be melted, as only the near-net-shape volume is printed, and infill patterns can be integrated in the 3D-printing strategies. Printed wax foam cools substantially faster than solid cast blocks, and the rough milling step, typically responsible for removing large material volume, is no longer necessary. A precise finishing-milling step then ensures the required surface quality.

Wax formwork technology demonstrates a better CO2 emissions balance compared to comparable formwork materials, primarily due to its high reuse rate of 200–500 melting cycles. Assuming that EPS can realistically be used only once as a formwork material before it is downcycled or disposed of, the contrast becomes even more pronounced: at 200 reuse cycles, the effective CO2 emissions of wax formwork are approximately 3.5 times lower than those of EPS, and at 500 cycles they become nearly nine times lower, despite EPS’s low material density.

The development of wax foam offers additional potential to reduce the CO2 footprint. By incorporating 30–50% air, wax foam lowers block weight and overall wax consumption, reducing the paraffin content to only 50–70%.

Concrete mixture performance and achieved architectural concrete surface quality: The fine-grain Celitement-based concrete mix achieved a compressive strength class of C30/37 according to DIN 1045-3, performing comparably to Portland Cement while offering substantial CO2 reductions. Wax formwork demonstrated high robustness under shotcrete application. Future studies could evaluate the long-term durability and environmental performance of Celitement-based low-CO2 concrete under varying climatic and mechanical conditions to further validate its suitability for architectural and structural applications. Regarding surface quality, Coating 2 produced the best architectural concrete surface and enabled at least two shotcrete cycles. Coatings 1 and 3 improved surface quality for single-use applications but required reapplication before additional shotcrete application. In contrast, uncoated wax formwork consistently resulted in rough, porous, and uneven concrete surfaces, confirming that coatings are essential for achieving exposed architectural concrete quality. OWRK measurements revealed an extremely low polar component of the wax surface (≈3 mN/m), which explains the inherently poor adhesion behavior of coatings on CFW wax.

Consequently, the development of improved coating systems represents an important direction for future research. Strategies include (i) investigations into advanced coatings optimized for the low-polarity wax surface, (ii) chemically modifying the wax surface to enhance coating adhesion, and (iii) reducing the polarity of the wax material itself to potentially eliminate the need for coatings or release agents entirely. Advancements in these areas could significantly increase the durability, efficiency, and sustainability of reusable wax formwork for high-quality architectural concrete production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J., A.S., B.K., F.M. and N.H.; methodology, S.J., J.M., H.K., B.K., A.S., F.M. and N.H.; software, S.J. and B.K.; validation, S.J. and F.M.; formal analysis, S.J.; investigation, S.J., B.K. and F.M.; data curation, S.J., B.K. and F.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J.; writing—review and editing, J.M., H.K., A.S., B.K., F.M. and N.H.; visualization, S.J. and B.K.; supervision, N.H.; project administration, A.S. and N.H.; funding acquisition, A.S. and N.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project with the funding code 01QE2040C and E!114493 ROBOCRETE was funded as part of the European funding program Eurostars with funds from the Federal Ministry of Research, Technology, and Space (Bundesministerium für Forschung, Technologie und Raumfahrt—BMFTR) and supported by the project management German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt—DLR). We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of Technische Universität Braunschweig.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Benedict Sonntag for his technical support and Osman Zihni for his student support in carrying out the experiments at the DBFL. This paper’s English scientific language was refined with the assistance of ChatGPT v5.1 to enhance clarity and precision in technical communication.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Bhavatarini Kumaravel and Asbjørn Søndergaard were employed by the company Odico A/S. Author Falk Martin was employed by the company BNB Potsdam. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Bennett, D. The Art of Precast Concrete: Colour Texture Expression; Birkhauser—Publishers for Architecture: Basel, Switzerland, 2005; ISBN 9783764371500. [Google Scholar]

- Feirabend, S.; Emami, A.; Riedel, E. Eine Einzigartige Fassade Aus Glasfaserbeton. Bautechnik 2014, 91, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jipa, A.; Bürgin, T.; Dillenburger, B. 3D-Printed Formworks for Glass Fibre Reinforced Shotcrete. In Proceedings of the International Glassfibre Reinforced Concrete Association GRC2023 Congress, London, UK, 9–12 May 2023; International Glassfibre Reinforced Concrete Association: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hack, N.; Kloft, H. Shotcrete 3D Printing Technology for the Fabrication of Slender Fully Reinforced Freeform Concrete Elements with High Surface Quality: A Real-Scale Demonstrator. In Proceedings of the Second RILEM International Conference on Concrete and Digital Fabrication, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–8 July 2020; Bos, F.P., Lucas, S.S., Wolfs, R.J.M., Salet, T.A.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1128–1137. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, G.; Nicholas, P.; Paul, G.; Pietroni, N.; Vidal Calleja, T.; Xie, M.; Schork, T. Automated Shotcrete: A More Sustainable Construction Technology. In Sustainable Engineering: Concepts and Practices; Dunmade, I.S., Daramola, M.O., Iwarere, S.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 331–345. ISBN 978-3-031-47215-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kloft, H.; Hack, N.; Sawicki, B.; Dörrie, R.; Gosslar, J.; Jonischkies, S.; Ledderose, L.; Zöllner, J.-P. Digital Fabrication Strategies for Sustainability. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Sustainable Development in Civil, Urban and Transportation Engineering, Wrocław, Poland, 14–17 October 2024; Różański, A., Bui, Q.-B., Sadowski, Ł., Tran, M.T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dörrie, R.; Laghi, V.; Arrè, L.; Kienbaum, G.; Babovic, N.; Hack, N.; Kloft, H. Combined Additive Manufacturing Techniques for Adaptive Coastline Protection Structures. Buildings 2022, 12, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloft, H.; Gehlen, C.; Dörfler, K.; Hack, N.; Henke, K.; Lowke, D.; Mainka, J.; Raatz, A. TRR 277: Additive Manufacturing in Construction. Civ. Eng. Des. 2021, 3, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloft, H.; Gehlen, C.; Dörfler, K.; Hack, N.; Henke, K.; Lowke, D.; Mainka, J.; Raatz, A. TRR 277: Additive Fertigung Im Bauwesen. Bautechnik 2021, 98, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Additive Manufacturing in Construction (AMC), TRR 277—Additive Manufacturing in Construction (AMC) TRR277. Available online: https://amc-trr277.de/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Bock, T. Digital Design and Robotic Production of 3D Shaped Precast Components. In Proceedings of the ISARC 2008—Proceedings from the 25th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction, Vilnius, Lithuania, 26–29 June 2008; Zavadaskas, E.K., Kalauskas, A., Skibniewski, M.J., Eds.; International Association for Automation and Robotics in Construction (IAARC): Vilnius, Lithuania, 2008; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Lin, X.; Bao, D.W.; Min Xie, Y. A Review of Formwork Systems for Modern Concrete Construction. Structures 2022, 38, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, D.; Bærentzen, A.; Clausen, K.; Fsiker, A.-S.; Gravesen, J.; Lund, M.N.; Nørbjerg, T.B.; Steenstrup, K.; Søndergaard, A. Desigining for Hot-Blade Cutting. In Proceedings of the Advances in Architectural Geometry 2016, Zurich, Switzerland, 9–13 September 2016; Adriaenssens, S., Gramazio, F., Kohler, M., Menges, A., Pauly, M., Eds.; vdf Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zürich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 306–327. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, R.; Gramazio, F.; Kohler, M. Force Adaptive Hot-Wire Cutting: Integrated Design, Simulation, and Fabrication of Double-Curved Surface Geometries. In Proceedings of the Advances in Architectural Geometry 2015—Force Adaptive Hot-Wire Cutting: Integrated Design, Simulation, and Fabrication of Double-Curved Surface Geometries, Zurich, Switzerland, 29 September 2016; vdf Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zürich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 288–305. [Google Scholar]

- Søndergaard, A.; Feringa, J.; Nørbjerg, T.; Steenstrup, K.; Brander, D.; Graversen, J.; Markvorsen, S.; Bærentzen, A.; Petkov, K.; Hattel, J.; et al. Robotic Hot-Blade Cutting. In Proceedings of the Robotic Fabrication in Architecture, Art and Design 2016, Sydney, Australia, 28 February 2016; Reinhardt, D., Saunders, R., Burry, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 150–164. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, R.; Gramazio, F.; Kohler, M. Force Adaptive Hot-Wire Cutting. In Proceedings of the Advances in Architectural Geometry 2016, Zürich, Switzerland, 16 August 2016; Adriaenssens, S., Gramazio, F., Kohler, M., Menges, A., Pauly, M., Eds.; vdf Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zürich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 288–305. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, H.R. Double-Curved Precast Concrete Elements Research into Technical Viability of the Flexible Mould Method Double-Curved Precast Concrete Elements. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, D.; Herr, C.; Lombardi, D.; Xia, J.; Herr, C.M.; Gao, Z. Prototyping Parametrically Designed Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Façade Elements Using 3D Printed Formwork. In Proceedings of the IASS 2022 Symposium affiliated with APCS 2022 conference, Beijing, China, 19 September 2022; International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures (IASS): Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chousou, G.; Yoo, A.; Jipa, A.; Dillenburger, B. Cadenza 3D-Printed Formwork for a Free-Form Stair. In Proceedings of the esign Modelling Symposium Berlin: Scalable Disruptors, Kassel, Germany, 14–18 September 2024; Eversmann, P., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 520–532. [Google Scholar]

- Jipa, A.; Dillenburger, B. 3D Printed Formwork for Concrete: State-of-the-Art, Opportunities, Challenges, and Applications. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 9, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowke, D.; Anton, A.; Buswell, R.; Jenny, S.E.; Flatt, R.J.; Fritschi, E.L.; Hack, N.; Mai, I.; Popescu, M.; Kloft, H. Digital Fabrication with Concrete beyond Horizontal Planar Layers. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 186, 107663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonischkies, S.; Mainka, J.; Kloft, H.; Kinzebach, W.; Hack, N. Non-Waste-Wachsschalung Für Den Individualisierten Betonfertigteilbau—Praxisbeispiel Des Digitalen Fertigungsprozesses Für Eine Kleinserie Großformatiger Poller. Beton-Und Stahlbetonbau 2022, 117, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, F.W. Untersuchungen Zur Eignung Der Non-Waste-Wachsschalungstechnologie Für Die Automatisierte, Individuelle Fertigung von Betonbauteilen. Ph.D. Thesis, Technischen Universität Carolo-Wilhelmina zu Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jeldrik, M. Non-Waste-Wachsschalungen. Ph.D. Thesis, Technischen Universität Carolo-Wilhelmina zu Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mainka, J.; Kloft, H.; Baron, S.; Hoffmeister, H.W.; Dröder, K. Non-Waste-Wachsschalungen: Neuartige Präzisionsschalungen Aus Recycelbaren Industriewachsen. Beton-Und Stahlbetonbau 2016, 111, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonischkies, S.; Mainka, J.; Kloft, H.; Kumaravel, B.; Sondergaard, A.; Martin, F.; Hack, N. Dataset on Accentuated Milled Wax Formwork for Thin-Shell Robotic Shotcreted Architectural Low-CO2 Concrete Façade Elements. Dataset. 2025. Available online: https://leopard.tu-braunschweig.de/receive/dbbs_mods_00079371 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Brugnaro, G.; Hanna, S. Adaptive Robotic Carving—Training Methods for the Integration of Material in Timber Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the ROBARCH 2018, Robotic Fabrication in Architecture, Art and Design 2018, Zurich, Switzerland, 10–15 September 2018; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 336–348. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhagen, G.; Braumann, J.; Brüninghaus, J.; Neuhaus, M.; Sigrid, B.-C.; Kuhlenkötter, B. Path Planning for Robotic Artistic Stone Surface Production. In Proceedings of the Robotic Fabrication in Architecture, Art and Design 2016, Sydney, Australia, 28 February 2016; Reinhardt, D., Saunders, R., Burry, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Rippmann, M.; Van Mel, T.; Popescu, M.; Augustynowicz, E.; Echenagucia, T.M.; Barentin, C.C.; Frick, U.; Block, P. The Armadillo Vault. In Proceedings of the Advances in Architectural Geometry 2016, Sydney, Australia, 16 August 2016; Adriaenssens, S., Gramazio, F., Kohler, M., Menges, A., Pauly, M., Eds.; vdf Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zürich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 344–363. [Google Scholar]

- Rippmann, M.; Van Mele, T.; Popescu, M. The Armadillo Vault: Computational Design and Digital Fabrication of a Freeform Stone Shell. In Proceedings of the Advances in Architectural Geometry 2015—The Armadillo Vault: Computational Design and Digital Fabrication of a Freeform Stone Shell, Zurich, Switzerland, 29 September 2016; Adriaenssens, S., Gramazio, F., Kohler, M., Pauly, M., Eds.; vdf Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zürich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 344–363. [Google Scholar]

- Surface Articulation Through Digital Design and Fabrication Tools|Agata Kycia. Available online: https://agatakycia.com/2017/02/02/articulation-of-doubly-curved-surfaces-through-cnc-milling/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- DBFL. Available online: https://www.tu-braunschweig.de/ite/large-scale-fabrication-laboratories/digital-building-fabrication-laboratory-dbfl (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Kloft, H.; Dörfler, K.; Bährens, M.; Dielemans, G.; Diller, J.; Dörrie, R.; Gantner, S.; Hensel, J.; Keune, A.; Lowke, D.; et al. Die Forschungsinfrastruktur Des SFB TRR 277 AMC Additive Fertigung Im Bauwesen. Bautechnik 2022, 99, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemmermann, P.; Schweike, U.; Garbev, K.; Beuchle, G.; Möller, H. Celitement—A Sustainable Prospect for the Cement Industry. Cem. Int. 2010, 8, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Garbev, K.; Beuchle, G.; Schweike, U.; Stemmermann, P. Hydration Behavior of Celitement®: Kinetics, Phase Composition, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. In Proceedings of the 13th International Congress on the Chemistry of Cement, Madrid, Spain, 3–8 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Garbev, K.; Beuchle, G.; Schweike, U.; Merz, D.; Dregert, O.; Stemmermann, P. Preparation of a Novel Cementitious Material from Hydrothermally Synthesized C-S-H Phases. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 97, 2298–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemmermann, P.; Beuchle, G.; Garbev, K.; Schweike, U. Celitement®—A New Sustainable Hydraulic Binder Based on Calcium Hydrosilicates. In Proceedings of the 13th International Congress on the Chemistry of Cement, Madrid, Spain, 3–8 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- EN 12350-5; Testing Fresh Concrete—Part 5: Flow Table Test. CEN (European Committee for Standardization): Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- DIN 1045-3; Tragwerke aus Beton, Stahlbeton und Spannbeton—Teil 3: Bauausführung. DIN (Deutsches Institut für Normung): Berlin, Germany, 2012.

- EPS Foam Density Guide: Choosing the Right Grade for Your Project. Available online: https://www.thefoamcompany.com.au/blogs/news/a-guide-to-understanding-eps-foam-density?srsltid=AfmBOoq-qXOU0TIPUSb-yK99TLWGgX5BdveHl_LOw8_tZ1AyvibN6HWH (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- SikaBlock® M700 N|Braune Modellbauplatten. Available online: https://deu.sika.com/de/industrie/advanced-resins/modell-und-formenbau/blockmaterialien/braune-modellbauplatten/sikablock-m700-n.html (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Polyoxymethylene—Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polyoxymethylene (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Paraffin Wax—Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paraffin_wax (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Paraffin Wax 3.75 Kg CO2e/Kg|Verified by CarbonCloud. Available online: https://apps.carboncloud.com/climatehub/product-reports/id/453411129460 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Emission Factor: PS (Polystyrene)|Materials and Manufacturing|Plastics and Rubber Products|Germany|Climatiq. Available online: https://www.climatiq.io/data/emission-factor/8999e49a-9e59-4c21-9489-6fd60eebdad4 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Your Next Polyurethane Will Be Recycled. Available online: https://plastics-rubber.basf.com/emea/en/performance_polymers/news-events/stories/your-next-polyurethane-will-be-recycled (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Emission Factor: Polyoxymethylene (POM)|Materials and Manufacturing|Plastics and Rubber Products|Europe|Climatiq. Available online: https://www.climatiq.io/data/emission-factor/1125cba1-849b-477c-ae1f-886eaa88e02f (accessed on 2 December 2025).

Figure 1.

Diagram of the production of thin-shelled concrete elements in 5 steps.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the production of thin-shelled concrete elements in 5 steps.

Figure 2.

Crack- and stress-free wax block production in three steps with optimized cooling parameters.

Figure 2.

Crack- and stress-free wax block production in three steps with optimized cooling parameters.

Figure 3.

(a) Physical roughening substep 1, (b) digital model of 2nd roughening substep, (c) digital model of 3rd roughening substep.

Figure 3.

(a) Physical roughening substep 1, (b) digital model of 2nd roughening substep, (c) digital model of 3rd roughening substep.

Figure 4.

(a) Corresponding waypoints with x, y, and z-coordinates for orienting the milling tool; (b) programmed milling path sequence executing toolpath-design-driven milling surface articulation.

Figure 4.

(a) Corresponding waypoints with x, y, and z-coordinates for orienting the milling tool; (b) programmed milling path sequence executing toolpath-design-driven milling surface articulation.

Figure 5.

(a) Digital twin, linear surface articulation milling tool trajectory; (b) physical milled wax block by linear surface articulation.

Figure 5.

(a) Digital twin, linear surface articulation milling tool trajectory; (b) physical milled wax block by linear surface articulation.

Figure 6.

(a) Digital twin, crossed surface articulation milling tool trajectory; (b) physical milled wax block by crossed surface articulation.

Figure 6.

(a) Digital twin, crossed surface articulation milling tool trajectory; (b) physical milled wax block by crossed surface articulation.

Figure 7.

(a) Digital twin, topology-adapted flow surface articulation milling tool trajectory; (b) physical milled wax block by topology-adapted flow surface articulation.

Figure 7.

(a) Digital twin, topology-adapted flow surface articulation milling tool trajectory; (b) physical milled wax block by topology-adapted flow surface articulation.

Figure 8.

(a) Digital twin, topology-adapted drilling chisel surface articulation milling tool trajectory; (b) physical milled wax block by topology-adapted drilling chisel surface articulation design.

Figure 8.

(a) Digital twin, topology-adapted drilling chisel surface articulation milling tool trajectory; (b) physical milled wax block by topology-adapted drilling chisel surface articulation design.

Figure 9.

(a,b) Manual shotcrete on toolpath-design-driven milled wax formwork with wax-based release agent, (c) placing the anchors.

Figure 9.

(a,b) Manual shotcrete on toolpath-design-driven milled wax formwork with wax-based release agent, (c) placing the anchors.

Figure 10.

Application of (a) Coating 1—Kaiser Hydro-Trennlack EP4211189, (b) Coating 2—LF Modellak 13-1362, and (c) Coating 3—MC-Color Flair vision.

Figure 10.

Application of (a) Coating 1—Kaiser Hydro-Trennlack EP4211189, (b) Coating 2—LF Modellak 13-1362, and (c) Coating 3—MC-Color Flair vision.

Figure 11.

(a–c) Robotic shotcrete on toolpath-design-driven milled coated wax formwork with SOK Ultra release agent; (d) finished shotcreted thin-shell concrete element with printed stiffening cross.

Figure 11.

(a–c) Robotic shotcrete on toolpath-design-driven milled coated wax formwork with SOK Ultra release agent; (d) finished shotcreted thin-shell concrete element with printed stiffening cross.

Figure 12.

Details toolpath-design-driven milled wax formwork surfaces: (a) linear surface articulation wax formwork; (b) crossed surface articulation wax formwork; (c) topology-adapted flow toolpaths driven milled wax formwork; (d) topology-adapted drilling chisel toolpaths driven milled wax formwork.

Figure 12.

Details toolpath-design-driven milled wax formwork surfaces: (a) linear surface articulation wax formwork; (b) crossed surface articulation wax formwork; (c) topology-adapted flow toolpaths driven milled wax formwork; (d) topology-adapted drilling chisel toolpaths driven milled wax formwork.

Figure 13.

Comparison of conventional smoothing and toolpath-design-driven surface articulation milling and travel time.

Figure 13.

Comparison of conventional smoothing and toolpath-design-driven surface articulation milling and travel time.

Figure 14.

(a,b) Demolding of manually sprayed thin-shell concrete elements; (c) demolded manually sprayed thin-shell concrete element of topology-adapted drilling chisel toolpath-design-driven milled wax formwork.

Figure 14.

(a,b) Demolding of manually sprayed thin-shell concrete elements; (c) demolded manually sprayed thin-shell concrete element of topology-adapted drilling chisel toolpath-design-driven milled wax formwork.

Figure 15.

(a) Rear side of robotic shotcreted thin-shell concrete element; (b) front side of robotic shotcreted thin-shell concrete element.

Figure 15.

(a) Rear side of robotic shotcreted thin-shell concrete element; (b) front side of robotic shotcreted thin-shell concrete element.

Figure 16.

Final result: robotic shotcreted thin-shell concrete elements on toolpath-design-driven milled, coated wax formwork.

Figure 16.

Final result: robotic shotcreted thin-shell concrete elements on toolpath-design-driven milled, coated wax formwork.

Figure 17.

Coating 1 on wax formwork: (a) concrete surface quality result without coating, (b) coated wax formwork, (c) concrete surface quality result of coated wax formwork.

Figure 17.

Coating 1 on wax formwork: (a) concrete surface quality result without coating, (b) coated wax formwork, (c) concrete surface quality result of coated wax formwork.

Figure 18.

Coating 2 on wax formwork: (a) concrete surface quality result without coating, (b) coated wax formwork, (c) concrete surface quality result of coated wax formwork.

Figure 18.

Coating 2 on wax formwork: (a) concrete surface quality result without coating, (b) coated wax formwork, (c) concrete surface quality result of coated wax formwork.

Figure 19.

Coating 3 on wax formwork: (a) concrete surface quality result without coating, (b) coated wax formwork, (c) concrete surface quality result of coated wax formwork.

Figure 19.

Coating 3 on wax formwork: (a) concrete surface quality result without coating, (b) coated wax formwork, (c) concrete surface quality result of coated wax formwork.

Table 1.

Fine-grain fiber-reinforced low-CO2 shotcrete concrete mixture.

Table 1.

Fine-grain fiber-reinforced low-CO2 shotcrete concrete mixture.

| Concrete Composition for 1 m3 (Dry) | Requirements/Application |

|---|

| kg/m3 | Designation |

|---|

| 900 | Aggregate 0/2 | C 30/37 | Strength class |

| 700 | Celitement | X0 | Exposure class |

| 1.5 | Plasticiser | WO | Moisture class |

| 400 | Water | F2/F3 | Consistency class |

| 2 | Fibers | 0.47 | Max. w/c or w/z eq-value |

| 150 | Limestone powder | 2.00% | Air void class |

| | | 4.0 mm | Largest grain size |

| | | A | Grading curve range |