1. Introduction

Historical seismic records indicate that strong aftershocks with considerable destructive potential often occur successively following a main shock [

1]. Owing to the extremely short time interval between the main shock and subsequent aftershocks, it is generally impractical to implement timely and effective repair or strengthening measures for damaged buildings [

2]. For instance, during the Ms 8.0 Wenchuan Earthquake in 2008 [

3], many building structures were initially damaged by the main shock, and the subsequent aftershocks further aggravated the destruction, rendering numerous residential buildings unsafe or even leading to collapse. Moreover, the cumulative effects resulting from progressive structural damage were particularly pronounced. Under such seismic conditions, the interaction and combined influence of main shocks and aftershocks deserve special attention [

4].

In current seismic design practice, building structures are typically designed considering only a single seismic event. However, to ensure structural safety and resilience, more comprehensive quantitative evaluations of seismic performance under aftershock sequences are required. Giovanni Rinaldin et al. [

5] selected seismic records with peak ground acceleration (PGA) values not lower than those of the main shock as aftershock inputs for time-history analyses, demonstrating that structures subjected to multiple seismic excitations demand significantly higher ductility capacity. Raghunandan et al. [

6] performed analytical studies on multi-degree-of-freedom reinforced concrete (RC) frame systems under main shock-aftershock sequences and reported that the maximum interstory drift ratio exhibited limited sensitivity to aftershock effects. Chorafa et al. and Panagiota et al. [

7,

8] emphasized that multiple seismic scenarios, structure-specific characteristics, and soil-structure interaction (SSI) effects should be comprehensively considered in the seismic design of concrete-filled steel tube (CFST) frame structures and steel structures equipped with buckling-restrained braces (BRBs). Katsimpini et al. [

9] proposed an empirical formulation for evaluating the bearing capacity of CFST members based on finite-element numerical simulations. Hua Huang et al. [

10,

11] further pointed out that the residual strength and stiffness of structures after seismic damage may differ substantially from estimations based solely on drift ratios, suggesting that damage states induced by main shocks can be more accurately characterized by explicitly incorporating residual bearing capacity. Overall, traditional time-history analysis methods based on specific ground motion parameters are insufficient to capture the inherent randomness and uncertainty of structural seismic responses. Consequently, probabilistic approaches for assessing seismic performance and damage have emerged as an important and promising direction for future research.

Incremental dynamic analysis (IDA) is currently one of the most widely adopted methods for evaluating the seismic performance of structures [

12,

13]. Cornell et al. [

14] established a rigorous probabilistic framework for seismic design and performance-based assessment, which was subsequently applied to steel moment-resisting frame systems. Building on this foundation, Wen et al. and Zhou et al. [

15,

16] proposed fragility assessment frameworks that explicitly account for main shock-aftershock sequences, thereby offering valuable references for seismic design that incorporates aftershock effects. Kinali et al. [

17] examined steel frame structures with three different heights, quantified the probabilities associated with four performance limit states, and discussed their implications for seismic risk evaluation. Nazari et al. [

18] demonstrated that structural damage assessment based solely on main-shock intensity may lack sufficient accuracy, and suggested that damage states can be more reliably identified through pushover analysis, IDA, or by modifying constitutive relationships.

Shear walls exhibit high lateral stiffness and favorable ductility, making them effective seismic-resistant components. Dowden et al. [

19] incorporated thin steel plate shear walls into self-centering steel frames as both lateral load-resisting and energy-dissipating elements, and derived analytical expressions for the internal forces of individual components. Clayton et al. [

20,

21] proposed corresponding design approaches for self-centering flat steel plate shear walls with either four-edge or two-edge connections. Li Zhuoyu [

22] conducted seismic fragility analyses of core tube systems composed of CFST frames combined with steel plate shear walls. Silva et al. [

23] investigated the mechanical behavior of CFST columns manufactured with rubberized concrete (RuC) and further evaluated the seismic performance of moment-resisting frames incorporating such members. Dou et al. [

24], recognizing the superior seismic behavior of shear walls using CFSTs as boundary confinement elements, proposed a novel prefabricated composite RC shear wall integrated with a CFST frame (CCRCSW-CFST). Nevertheless, studies focusing on the seismic fragility of CFST frame-shear wall structures subjected to main shock-aftershock sequences remain limited. Consequently, it is essential to conduct systematic fragility analyses of CFST frame-shear wall systems under combined main shock and aftershock excitations.

This study focuses on CFST frame-shear wall structures as the primary research object. Through numerical simulations, the seismic performance and corresponding fragility curves of the structural system under main shock and aftershock excitations are evaluated for two structural configurations: with and without BRBs. On this basis, a comparative investigation is carried out to quantify the influence of main shock-aftershock sequences on the overall seismic performance of the structure.

Considering the characteristics of sequential ground motions, this research further examines the correlation among different intensity measures (IMs) associated with main shock-aftershock sequences and clarifies their interdependence. The effects of various aftershock types on the probabilistic seismic demand of CFST frame-shear wall systems are systematically analyzed. Moreover, a multivariate probabilistic seismic demand model incorporating aftershock-related parameters is developed to characterize structural fragility under both single main shock excitation and combined main shock-aftershock loading conditions.

2. Establishment of Finite Element Model and Construction of Seismic Waves

A 15-story CFST frame-shear wall structure is modeled using MIDAS finite element software. The building consists of six spans in the longitudinal direction, with an overall length of 43.2 m, and three spans in the transverse direction, with a total width of 15.0 m. The first story has a height of 4.2 m, while all remaining stories have a uniform height of 3.3 m, resulting in a total structural height of 50.4 m. The shear walls are designed with a thickness of 200 mm. The vertical reinforcement is arranged as 12@200, and the horizontal reinforcement is configured as 10@200. The seismic design parameters adopted in the numerical model are specified in Ref. [

25], and the detailed component properties are summarized in

Table 1. The standard live load is taken as 2.0 kN/m

2 for all typical floors and 0.5 kN/m

2 for the roof, whereas the standard dead load is 3.5 kN/m

2 for each floor and 5.0 kN/m

2 for the roof. A three-dimensional perspective view of the structural model is illustrated in

Figure 1.

Shell elements were adopted to simulate concrete floor slabs and shear walls, while nonlinear beam elements were employed to model beams and columns. Connection elements were utilized for the modeling of BRBs. For concrete materials, the confined concrete constitutive model was selected, whereas the kinematic hardening model with bilinear characteristics was adopted for steel materials [

26]. BRBs were connected to the frame structure exclusively through their core materials, ensuring that the core materials bear all axial forces, while the external steel tubes only serve to constrain the core materials. No bonding treatment was applied between the core materials and external steel tubes to minimize interfacial friction. The Bouc-Wen model was selected for relevant simulations [

26,

27]. During the dynamic analysis procedure, the P-Δ effect was taken into consideration, and structural control over convergence was implemented based on the displacement criterion. The Newmark integration method was used for solution, with the structural damping ratio set to 0.05. The parameters of BRBs are presented in

Table 2, and a schematic diagram of the BRBs-CFST frame-shear wall structure is illustrated in

Figure 2.

Modal analyses were conducted on the CFST frame-shear wall structures with and without BRBs using two finite element analysis platforms, MIDAS and PKPM. The resulting natural vibration frequencies for both structural configurations are summarized in

Table 3 and

Table 4, respectively.

As indicated in

Table 3 and

Table 4, the maximum discrepancy in the calculated natural vibration periods of the CFST frame-shear wall structure without BRBs is within 4.3%, while the corresponding error for the structure equipped with BRBs does not exceed 2.8%. These results demonstrate that the dynamic responses of the structural systems can be predicted with satisfactory accuracy using the MIDAS finite element analysis platform. Moreover, MIDAS enables efficient post-processing and interpretation of dynamic response data. Accordingly, MIDAS is adopted in this study as the primary tool for conducting subsequent numerical analyses.

In accordance with the Chinese Standard for the Seismic Resilience Assessment of Buildings [

28], a dual-control criterion based on PGA and peak ground velocity was adopted to ensure that the selected ground motions satisfied the minimum requirements for both acceleration and velocity. A total of ten seismic records were employed in the subsequent analyses, comprising six recorded natural ground motions and four synthetic motions. All ground motion data were obtained from the Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research center (PEER), and the corresponding parameters are summarized in

Table 5. In addition, the normalized response spectra of the selected ground motions are presented in

Figure 3.

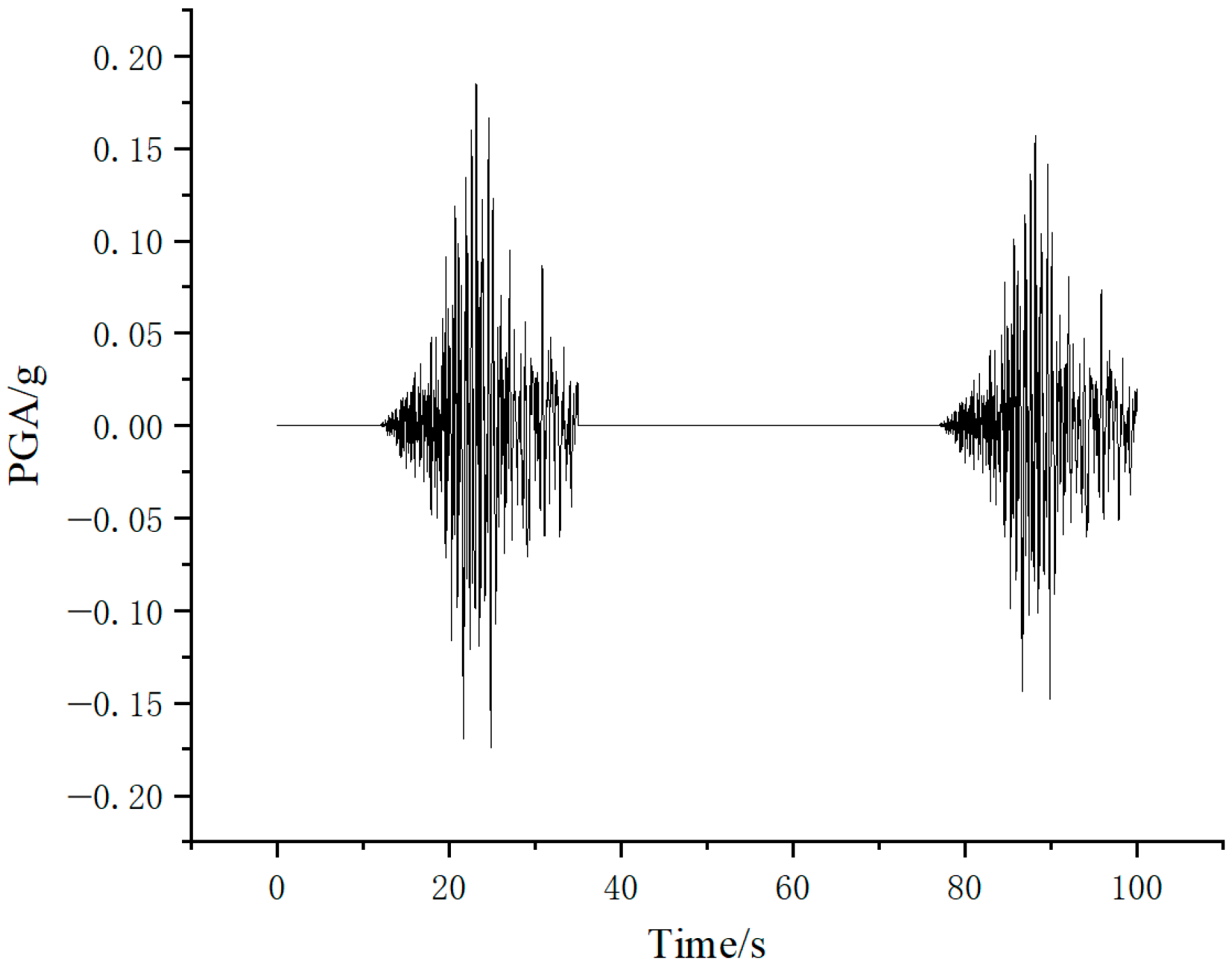

Main shock-aftershock sequences were generated using the attenuation method [

29,

30], and amplitude modulation was performed through the Hunt-Fill unequal-step modulation technique. Considering the realistic dynamic response characteristics of structures subjected to seismic loading, a time interval of 30 s was introduced between the main shock and aftershock inputs. This interval was selected to allow the structural response induced by the main shock to fully develop while preserving the plastic damage accumulated during the initial excitation. The detailed procedure for constructing the main shock-aftershock sequences is illustrated in

Figure 4. A bidirectional seismic input scheme was adopted, in which the longitudinal and transverse axes of the structure were designated as the principal and secondary input directions, respectively. For the primary direction, the ground motion was applied without scaling, whereas the input in the secondary direction was scaled by a factor of 0.8.