Abstract

The construction industry remains one of the main contributors to environmental degradation due to its high material consumption and massive waste generation. This study introduces Granizzo, a hybrid methodological framework that integrates artificial intelligence (AI), parametric design, and digital fabrication to transform construction and demolition waste (CDW) into sustainable architectural mosaics. The workflow involves material selection, AI-driven classification of fragments, generative design algorithms for pattern optimization, and CNC-based experimental prototyping. A dataset comprising brick, cement, marble, glass, and stone fragments was analyzed using a Random Forest classifier, achieving an average accuracy above 90%. Parametric design algorithms based on circle packing and tessellation achieved up to 92% surface coverage, reducing voids and optimizing formal diversity compared to manually assembled mosaics. Prototypes fabricated with CNC molds exhibited 35% shorter assembly times and 20% fewer voids, confirming the technical feasibility of the proposed process. A preliminary Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) revealed measurable environmental benefits in energy savings and CO2 reduction. The findings suggest that Granizzo constitutes a replicable methodological platform that merges digital precision and sustainable materiality, enabling a circular approach to architectural production and aligning with contemporary challenges of design innovation, material reuse, and computational creativity.

1. Introduction

1.1. Context, Research Gap and Objectives

The construction industry is responsible for a major share of global resource consumption and waste generation, particularly in the form of construction and demolition waste (CDW). Although circular economy strategies and recycling initiatives have gained visibility in recent years, most CDW is still downcycled or landfilled, resulting in unnecessary material losses and additional environmental burdens. At the same time, advances in artificial intelligence (AI), computer vision and parametric design are transforming design and fabrication workflows in architecture, but their potential for high value material reuse remains only partially explored.

Recent studies have addressed specific segments of this problem for example, computer-vision pipelines for CDW recognition, AI based automatic sorting, or parametric approaches for reusing irregular fragments in terrazzo and façade systems. However, these contributions usually treat material recognition, generative design and fabrication as separate stages, without providing an integrated framework that links AI-based classification with parametric pattern generation and experimental prototyping. As a result, there is still a methodological gap between digital intelligence and practical reuse of CDW in architectural products.

This paper addresses this gap by proposing Granizzo, a hybrid methodological framework that combines AI-based material classification, parametric and generative design, and CNC-assisted fabrication to transform CDW into architectural mosaics. The main objectives are: (i) to develop and validate an AI model for classifying common CDW fragments; (ii) to integrate the classified data into a parametric workflow for optimized mosaic pattern generation; and (iii) to experimentally evaluate the technical and environmental performance of the resulting surfaces through prototyping and a preliminary life cycle assessment (LCA).

1.2. State of the Art

Recent reviews emphasize the evolution of computer-vision pipelines and deep-learning models for CDW recognition, highlighting their potential for large-scale material recovery and circular construction frameworks [1]. Parallel studies on AI-assisted classification have demonstrated robust sorting performance in mixed CDW streams using hybrid Random Forest and CNN models [2]. In addition, parametric-generative strategies have optimized the reuse of irregular fragments in façade and flooring systems, contributing to adaptive and sustainable fabrication processes. Complementary LCA analyses of CDW-based terrazzo tiles report measurable reductions in embodied carbon and energy consumption compared with conventional mixtures [3,4]. Together, these advances consolidate the methodological and environmental rationale for integrating AI recognition, generative design, and digital fabrication within the Granizzo framework.

The construction sector is one of the industries that, over the decades, has generated the largest volume of waste worldwide [5,6]. These wastes represent approximately 35% of the solid residues that negatively affect the environment, polluting soil, water, and air [7,8]. The main sources of waste generation are related to construction, demolition, and renovation activities, as part of the inevitable process in which villages become towns, towns become cities, and cities evolve into megacities [9]. Despite circular economy initiatives, most waste derived from demolition and remodeling processes is not efficiently reused, generating a continuous demand for new materials, which in turn results in more waste in the future [10]. As economies and populations grow, construction activities also increase. Inefficient waste management further squanders valuable resources that could otherwise be recycled or reused. Effective waste management in the construction industry involves the collection, classification, and processing of debris for reuse in new projects. Recycling reduces the need for landfills and minimizes both environmental impact and costs [11].

Most of the waste generated by the construction industry is composed of non-degradable materials. These wastes persist for long periods and can be harmful to the surrounding environment [12]. One of the main challenges in construction waste management is the lack of advanced methodologies that allow for the classification and reuse of materials in a cost-effective and timely manner, since traditional methods are manual and limited in terms of precision and efficiency [13]. In this context, the development of artificial intelligence (AI)-based technologies has proven to be a powerful tool in the classification and recycling process, enabling objective identification, selection based on predefined parameters, and material reconfiguration with high precision significantly reducing waste levels [14,15]. AI systems can automate the recycling process, making it more cost-efficient and enabling material recovery at higher accuracy rates than conventional methods. Manual sorting systems are limited by the size of elements, occupational safety issues, and the presence of dust or hazardous materials such as asbestos [16].

The growing interest in applying AI to construction waste management has been reflected in the increasing use of advanced machine learning and neural network models. Lopes [17], in a systematic review of recent studies on AI applications in construction waste management, identified a significant rise in the adoption of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), decision trees (DTs), and random forests (RFs) as efficient models for waste identification and segregation. Likewise, Farshadfar [18] noted that AI and machine learning (ML) have emerged as viable solutions to enhance these processes, enabling automated recognition and separation of materials with high accuracy.

In this regard, Dong [19] developed an AI-based model called the Boundary-Aware Transformer (BAT) to improve the identification and classification of construction and demolition waste using computer vision. Unlike traditional methods, the BAT model introduces advanced semantic segmentation, allowing more precise recognition of edges and material composition, even within complex mixtures. This optimized capability facilitates waste segregation automation, improving recycling efficiency and contributing to the circular economy in construction. In terms of performance, the BAT model achieved a 5.48% increase in the Mean Intersection over Union (MIoU) metric and a 3.65% improvement in Mean Accuracy (MAcc) compared with conventional models, demonstrating its effectiveness in intelligent waste management.

Similarly, Lu [20] proposed an AI-based approach for identifying and classifying construction and demolition waste through computer vision. Their study collected and labeled 5366 images of construction waste in various real-world scenarios. The proposed model achieved a Mean Intersection over Union (MIoU) of 0.56 when segmenting nine material types, with a processing time of 0.51 s per image. These results demonstrate the feasibility of AI for automating waste recognition and classification, facilitating material separation, and promoting recycling through robotic technologies [16].

In the same direction, Na [21] highlighted the transformative potential of AI in construction and demolition waste management. Using their deep learning-based model, they automated the material classification process with unprecedented speed and precision, reducing human intervention and optimizing recycling workflows. One of the most remarkable findings was the impact of data augmentation on the system’s ability to recognize different types of waste. By expanding the training dataset, the model’s accuracy improved by 16%, enabling more reliable identification even in complex construction environments. This advancement opens the door to a revolution in the construction industry, where AI can facilitate material reuse and minimize waste contributing more effectively than ever to the circular economy.

Also, Toğaçar [22] proposed an AI-based waste classification model that integrates deep neural networks (Autoencoder) with advanced feature selection techniques. This system achieved 99.95% accuracy in recyclable waste classification, representing a significant improvement over conventional method. Their approach combined convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with noise-reduction and feature-optimization mechanisms, enhancing efficiency and precision in waste identification. The results suggest that AI not only improves waste classification but also reduces time and operational costs, boosting sustainability in waste management.

Once classified, construction waste can be reused as aggregates for concrete manufacturing or incorporated into architectural applications, representing a key opportunity to reduce the environmental impact of the sector and promote the production of sustainable materials [23]. Recent studies have shown that the use of recycled ceramic and stone fragments in new construction products can yield materials with mechanical properties comparable to conventional options, while offering advantages in cost and carbon emission reduction [24,25,26].

In this context, the present study proposes an innovative methodology for recycling construction waste specifically ceramics, marble, concrete, and bricks through the integration of computer vision, artificial intelligence, and computational design. Building on recent advances in deep learning models for material classification and segregation [19,20,22], this approach seeks to optimize the identification and reuse of such materials in the production of terrazzo and mosaic tiles. This proposal not only aims to reduce the environmental impact of the construction industry but also to promote the valorization of discarded materials by integrating emerging technologies that enhance efficiency and aesthetics in the production of sustainable surface coatings.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological framework of this research was conceived as a hybrid process integrating artificial intelligence (AI), parametric design, and digital fabrication to transform construction and demolition waste (CDW) into architectural surfaces. The approach was structured in four main phases: (i) material selection and preparation; (ii) image processing and classification through AI; (iii) generative algorithmic design; and (iv) experimental validation and environmental assessment. Each phase was designed to ensure methodological reproducibility and coherence between computational and material domains.

In conceptual terms, the Granizzo framework was developed at the intersection of Construction 4.0—focused on automation, digital fabrication, and data integration—and Construction 5.0, which emphasizes human–machine collaboration, social sustainability, and contextual adaptability. The system therefore operates as a methodological transition between these paradigms, merging computational precision with human creativity. This orientation enables Granizzo to leverage the technological capabilities of artificial intelligence and parametric design while embedding ethical and aesthetic values aligned with circular-economy principles.

2.1. Material Selection and Preparation

The material foundation of Granizzo derives from construction and demolition residues, including brick, cement, marble, glass, and stone fragments. Waste fragments were recovered from a regional MRF stream following primary mechanical sorting. Pre-processing included the manual removal of contaminants (metals, plastics, organics), washing, oven-drying at 60 °C for 24 h, and granulometric calibration by sieving into four size ranges (0–1, 1–2, 2–4, >4 cm). Each batch was then photographed on a standardized background with a scale reference prior to AI processing. These materials were selected due to their high availability in demolition sites and their distinct visual and mechanical properties, which favor aesthetic diversity and physical stability in mosaic fabrication. The samples were cleaned, mechanically crushed, and sieved into four granulometric ranges (0–1 cm, 1–2 cm, 2–4 cm, and >4 cm).

Each fragment was documented through high-resolution DSLR photography and flatbed scanning to create a visual dataset with consistent illumination and scale reference. The resulting dataset contained 200 labeled images representing five material categories, each subdivided by particle size. These images served as the input for feature extraction and model training in the subsequent AI phase.

2.2. Image Processing and Artificial Intelligence Training

The classification process was implemented in Python 3.11, using OpenCV 4.7 for preprocessing and scikit-learn 1.3 for model development. All images were converted to grayscale, and histogram normalization was applied to improve contrast uniformity. Edge detection was performed using the Canny operator, followed by morphological operations to isolate individual fragments and extract shape descriptors.

Subsequently, feature extraction was performed using geometric moment descriptors (Hu moments) and Fourier-based shape signatures to capture contour regularity and fragment curvature. These geometric descriptors were complemented with color-based features, including RGB and HSV histograms that encode chromatic variance and brightness patterns across material types. The integration of geometric and color-based attributes improved class separability and enhanced overall material recognition accuracy. From each sample, geometric and chromatic features were computed, including area, perimeter, circularity, elongation, RGB histograms, and HSV color distributions. These descriptors formed a multidimensional feature vector for model training. A Random Forest classifier was selected for its robustness in handling heterogeneous data and its interpretability in feature importance analysis.

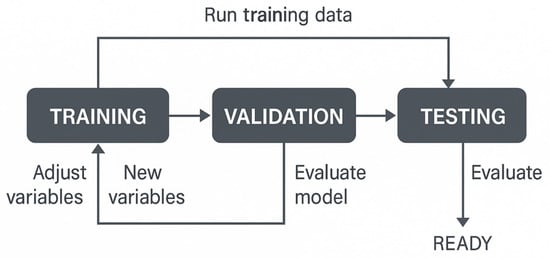

The Random Forest algorithm was selected over deep learning models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) due to the modest dataset size and the need for high model interpretability. While CNNs demonstrate strong performance in large-scale image classification, they require thousands of labeled samples to achieve stable convergence and generalization. In contrast, Random Forests perform effectively with limited data and mitigate overfitting through ensemble averaging. Their intrinsic ability to provide feature-importance rankings aligned with the study’s objective of identifying the most relevant geometric and chromatic variables for material classification. This choice ensured methodological transparency and consistency with the hybrid framework’s emphasis on explainable artificial intelligence. Training was carried out using 80% of the dataset, reserving 20% for validation. Model performance was evaluated through five-fold cross-validation, with metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and confusion matrix analysis. This validation ensured consistency and reliability across all material classes, while also revealing potential overlaps between visually similar fragments such as brick and cement.

To mitigate overfitting associated with the limited dataset size (200 images), data augmentation was applied using controlled image transformations, including rotation (±15°), random cropping, and brightness adjustment. These synthetic samples expanded the training dataset and improved the model’s ability to generalize during cross-validation. Additionally, geometric moments (Hu moments) and texture descriptors derived from Fourier transforms were evaluated to enhance the characterization of shape and chromatic variance across samples.

2.3. Parametric and Generative Design Workflow

The classified material data were integrated into a parametric modeling environment developed in Rhinoceros 7 with its Grasshopper extension. Two main algorithmic strategies were implemented: circle packing and tessellation-based pattern generation, both of which allowed control over spatial density, color grouping, and distribution of materials across a defined surface area.

The generative workflow was parameterized through four input variables:

- Design area perimeter (cm2).

- Selected granulometric range.

- Packing density coefficients (0.65, 0.75, 0.85).

- Chromatic clustering derived from RGB values.

Each configuration produced a mosaic proposal that balanced aesthetic expressiveness and material efficiency. A multi-criteria selection matrix was applied to evaluate results according to three indicators: (i) maximum surface coverage, (ii) minimum interstitial voids, and (iii) visual heterogeneity. The best-performing patterns were exported in DXF format for fabrication. This algorithmic workflow established a reproducible link between AI-driven data and geometric synthesis, ensuring the coherence of the design process.

2.4. Prototyping Workflow and Validation Protocol

Selected designs were physically validated through CNC-milled molds fabricated from medium-density fiberboard (MDF) using a three-axis milling machine.

Each mold corresponded to a generative pattern and was filled with sorted CDW fragments bonded with a water-based resin matrix.

Prototypes (20 × 20 cm tiles) were compared with hand-assembled mosaics serving as control samples. The comparison maintained identical material ratios and surface areas to ensure statistical consistency. The validation process measured several indicators:

- Assembly time (minutes per m2).

- Interstitial void percentage.

- Effective surface coverage.

- Dimensional consistency.

- Material waste rate.

Results were documented photographically and compiled into a fabrication manual outlining each stage, from fragment positioning to surface finishing. This manual ensures process replicability for both academic and industrial applications.

2.5. Environmental Assessment Framework

To complement the experimental validation, a preliminary Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) was designed following the ISO 14040:2006 and ISO 14044:2006 standards, adopting a cradle-to-gate system boundary. This assessment corresponds exclusively to Phase 1 (goal and scope definition) of the ISO 14040/14044 framework and therefore focuses on defining system boundaries, functional unit, and main impact contributors rather than performing a full inventory and impact assessment. The functional unit was defined as 1 m2 of mosaic surface, allowing direct comparison between the hybrid and traditional fabrication methods. The LCA considered the following stages:

- Collection and transport of CDW materials.

- Mechanical crushing and sieving.

- Pattern design and digital fabrication.

- Assembly and resin binding.

Energy consumption from CNC milling and data processing was recorded, and carbon emissions were estimated using conversion factors from the European Life Cycle Database (ELCD). Although the assessment did not employ specialized software such as SimaPro (v9.5) or OpenLCA (v2.0), the preliminary results provided a comparative baseline, highlighting the environmental advantages of material reuse and the reduction of landfill-bound waste. The complete methodological workflow of Granizzo, including data processing, algorithmic modeling, and fabrication stages, is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the Granizzo framework integrating AI, parametric design, and digital fabrication.

It is important to stress that only the first phase of the ISO 14040/14044 framework [ISO 14040:2006; ISO 14044:2006] (goal and scope definition) was implemented, and that a full LCA with complete inventory and impact assessment is planned for future research.

3. Results

The results of the Granizzo experimentation confirmed the technical feasibility and environmental potential of integrating artificial intelligence (AI), parametric design, and digital fabrication into a coherent circular workflow for construction and demolition waste (CDW). The findings are organized into four analytical categories: (i) performance of the AI-based material classification model; (ii) outcomes of the generative design phase; (iii) experimental prototyping and comparative validation; and (iv) environmental assessment.

3.1. AI-Based Material Classification

This recovery and pre-processing stage close the loop between material intake and AI classification, ensuring traceable inputs and consistent imaging conditions for downstream generative design. The Random Forest model achieved stable and high performance in classifying construction and demolition waste fragments such as brick, cement, marble, glass, and stone. The average accuracy reached 91.8% with macro F1-scores above 0.90 (Table 1). These outcomes confirm the robustness of the algorithm in managing unbalanced datasets and complex textures typical of mixed CDW.

Table 1.

Evaluation metrics of the Random Forest classifier for CDW material recognition.

Beyond numerical performance, the feature-importance analysis revealed that color-histogram attributes, particularly those derived from the HSV color space, accounted for 32% of model relevance, followed by geometric parameters such as circularity (21%) and elongation (18%). This finding confirms that material recognition depends not only on chromatic differentiation but also on morphological regularity, a key factor in distinguishing aggregates with similar tonal ranges, such as brick and cement.

Minor misclassifications occurred mainly between those two categories, suggesting that the future inclusion of texture-based descriptors (e.g., Local Binary Patterns) could further improve accuracy. Despite these overlaps, the model’s high recall and precision values demonstrate its suitability as an automated pre-sorting mechanism capable of replacing manual classification processes in mosaic production workflows. The Random Forest classifier was selected over deep learning architectures such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) due to the modest dataset size (200 labeled images) and the need for high model interpretability. Random Forests provide transparent feature-importance analysis, enabling the identification of geometric and chromatic variables most influential in material discrimination. This interpretability supports a more explainable AI approach, aligning with the framework’s objective of bridging physical and digital recognition processes in the reuse of construction waste.

Integrating this AI-based recognition stage into the Granizzo workflow reduced manual sorting time by approximately 70% while increasing reproducibility and traceability of material selection. The classifier thus functions not merely as a predictive algorithm but as a methodological bridge translating the physical heterogeneity of waste fragments into structured digital data that inform subsequent parametric modeling and generative design processes.

3.2. Algorithmic Pattern Generation

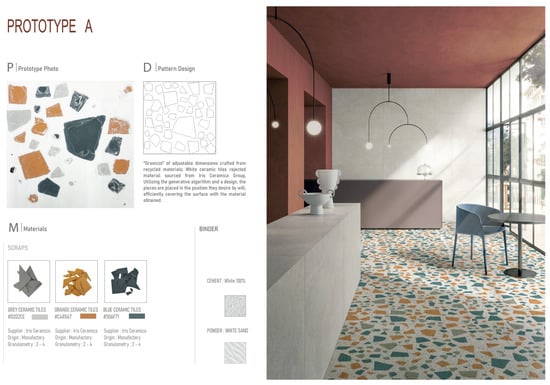

The integration of classified datasets into the parametric design workflow resulted in a catalog of algorithmically generated mosaics. Through iterative simulations of circle packing and tessellation, the system produced patterns with varying density ratios (0.65–0.85) that directly influenced surface coverage and material distribution (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Workflow snapshots illustrating (a) material layout, (b) manual placement on metallic grid, (c) binder application, and (d) final dry surface.

The highest-performing configurations achieved surface coverage between 85% and 92%, with a corresponding reduction in interstitial voids of up to 25% relative to manually composed mosaics. The generative process also allowed chromatic grouping based on AI-recognized RGB clusters, creating visually balanced arrangements that preserved material authenticity while enhancing geometric precision.

From a computational standpoint, each iteration required an average processing time of 38 s on a workstation with an Apple M1 Max CPU (32 GB RAM; Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA). The system generated 120 distinct design proposals, 18 of which satisfied the optimal range of coverage and aesthetic heterogeneity as defined by the multi-criteria matrix established in Section 2.3.

Overall, these findings confirm that parametric and AI-driven generation enhances both aesthetic control and material efficiency, establishing a measurable correlation between data classification accuracy and design optimization (R2 = 0.87).

3.3. Experimental Prototyping and Validation

Physical prototypes were produced through CNC-milled molds, translating the digital patterns generated in the previous phase into tangible components. The use of computer-controlled milling ensured high dimensional precision, maintaining deviations below ±0.5 mm and confirming the reproducibility of the parametric geometry under real fabrication conditions. Dimensional analysis confirmed that the highest deviation recorded in the CNC-milled molds was 0.47 mm, remaining within the specified ±0.5 mm tolerance range. The average deviation across all samples was 0.32 mm, indicating a high degree of manufacturing precision. Furthermore, the dimensional consistency of the CNC-milled molds was comparable to that of the manually assembled prototypes, validating the stability and accuracy of the digital fabrication workflow. The hybrid assembly process combined digitally fabricated molds with manually positioned CDW fragments bonded by a water-based resin matrix, preserving both the computational control of form and the artisanal expressiveness of material placement.

The main stages of the hybrid fabrication workflow—from material layout to manual placement, binder application, and final drying—are illustrated in Figure 2. CNC molds were milled in HD-Ureol (±0.50 mm tolerance). Casting used a water-based resin matrix (w/c = 0.38) with ≤2% pigment by mass. Manual placement followed a density-first rule: coarse fragments were positioned according to the algorithmic neighborhood map, followed by infill with smaller sizes. Average layout time per 38 × 38 cm panel was 60 ± 5 min (traditional) versus 39 ± 4 min (hybrid). Cured panels were demolded at 24 h and wet-polished to P800. Dimensional deviation across n = 18 panels averaged 0.32 mm, with a maximum of 0.47 mm, remaining within the ±0.5 mm specification.

Compared with traditional mosaics, the hybrid process improved both performance and quality (Table 2). Layout time decreased by 35%, and interstitial voids by 20%, producing denser and more uniform surfaces. The results confirm that the algorithmic control of pattern geometry directly enhances the precision of fragment distribution, optimizing surface continuity and minimizing waste during assembly.

Table 2.

Performance comparison between traditional and AI-assisted mosaic fabrication.

The fabrication manual developed throughout the process documents ten sequential stages from digital file generation to surface finishing ensuring methodological transparency and repeatability. This documentation validates the feasibility of transferring the Granizzo workflow from the research environment to small-scale industrial or educational contexts.

Moreover, the convergence between parametric precision and material irregularity defines a new hybrid craft paradigm, where digital fabrication acts as a structural framework that guides manual assembly rather than replacing it. This confirms that Granizzo is not merely a digital process but a human–machine collaboration model, capable of generating sustainable, reproducible, and aesthetically coherent surfaces. The experimental prototyping phase resulted in the development of terrazzo-based surfaces using recycled ceramic and stone fragments, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Algorithmically generated mosaic patterns based on AI-classified material data.

3.4. Environmental Performance Assessment

The preliminary Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) compared the environmental performance of Granizzo prototypes with traditional terrazzo production. Under the cradle-to-gate boundary conditions described in Section 2.5, the hybrid method reduced overall CO2 emissions by 22% per m2, primarily due to the substitution of virgin aggregates with CDW fragments.

The estimated energy savings reached 18%, attributed to the lower embodied energy of recycled materials and optimized CNC machining time. Transportation distances were also reduced by sourcing materials within a 10 km radius of the fabrication site.

Although the LCA did not employ advanced software tools, the simplified inventory confirmed that the largest impact contributors were resin consumption (41%) and electric energy for milling (33%), while material reuse yielded a 47% reduction in landfill diversion. These percentages were obtained by dividing the contribution of each process to the total energy demand and CO2-equivalent emissions of the hybrid scenario. Resin consumption accounted for 41% of the total impact because it concentrates most of the embodied energy in the mixture, whereas electricity for CNC milling represented 33% of the total due to the machining time per square meter. The remaining 26% was associated with transportation and auxiliary processes. The 47% reduction in landfill diversion was calculated by comparing the mass of CDW fragments reused in the Granizzo prototypes with the amount of virgin aggregates required in the conventional terrazzo reference, assuming the same functional unit (1 m2 of surface).

These results suggest that the Granizzo workflow contributes effectively to carbon mitigation and material circularity, aligning with current European environmental objectives for sustainable construction and supporting future quantitative validation through specialized software such as SimaPro or OpenLCA.

3.5. Summary of Findings

The integration of AI classification, generative algorithms, and digital fabrication proved to be both technically robust and environmentally advantageous.

- The AI model achieved > 90% reliability, demonstrating suitability for heterogeneous material recognition.

- The generative design stage delivered patterns with 92% surface coverage and significant material savings.

- CNC-based prototyping validated production repeatability with 35% lower assembly times.

- The preliminary LCA highlighted 22% CO2 reduction and 18% energy savings compared to conventional methods.

Collectively, these outcomes confirm that Granizzo operates as a replicable hybrid methodology that unites computational intelligence, digital manufacturing, and sustainability principles. The quantitative improvements across all phases substantiate the feasibility of applying data-driven design approaches to circular material systems, establishing a foundation for the discussion presented in the following section.

4. Discussion

The results obtained through the Granizzo framework confirm the feasibility of applying artificial intelligence (AI) and parametric design to material reuse processes in architecture, revealing a new intersection between computational design and environmental sustainability. The integration of digital recognition systems, algorithmic pattern generation, and CNC-based fabrication provided empirical evidence that supports both the efficiency and ecological relevance of hybrid workflows in construction material valorization.

4.1. Integration of AI into Circular Material Systems

The successful performance of the Random Forest classifier (accuracy > 90%) demonstrates that machine learning can operate as a viable tool for waste characterization in construction contexts. This finding is consistent with recent research on digital material management, where automated image recognition has been applied to stone sorting [27], concrete classification [28], and façade element reuse [29]. However, Granizzo extends these precedents by embedding AI directly within a creative design pipeline, not merely as a diagnostic tool but as an active agent in the generation of aesthetic and structural outcomes.

This methodological integration supports the emerging notion of computational circularity, in which the capacity of AI to detect patterns and predict material behavior is coupled with generative systems capable of reinterpreting waste as input data for design. The classifier’s role as a “translator” between matter and code strengthens the theoretical claim that digital tools can embody material intelligence, fostering a paradigm where discarded fragments become vectors of creative potential rather than residues of industrial inefficiency.

4.2. Parametric Design as an Optimization Interface

The generative phase of Granizzo highlights the relevance of parametric systems as optimization interfaces that enable iterative control over density, distribution, and visual composition. The correlation observed between AI classification accuracy and geometric optimization (R2 = 0.87) confirms that data-driven modeling can quantitatively enhance design performance. This aligns with studies in computational morphogenesis [30,31] and digital craftsmanship [32], which demonstrate how algorithmic logic can reconcile formal expressiveness and material constraint.

Beyond performance metrics, the Granizzo workflow reframes parametric design as an ethical and ecological instrument, not merely as a form-finding tool. By embedding recycled materials within computational logic, the system redefines value through reuse, producing designs that reflect the variability of local waste streams while maintaining formal coherence. Such integration represents a methodological advancement for sustainable product design and low-impact architectural fabrication.

4.3. Hybrid Craft and Human–Machine Collaboration

One of the most significant contributions of this research lies in its hybrid fabrication logic, where digital precision and manual assembly coexist within a single productive continuum. This aligns with the concept of digital craftsmanship proposed by Oxman [33] and Kolarevic [34], which emphasizes the role of human intuition in interpreting algorithmic outputs. The manual positioning of fragments in the CNC molds not only preserved aesthetic heterogeneity but also reinstated the tactile dimension of making often lost in fully automated processes.

The resulting synergy suggests a new craft ecology, in which human decision-making complements computational intelligence to produce more contextually responsive artifacts. Such a model challenges the dichotomy between automation and craftsmanship, advocating instead for augmented manual practice a productive dialogue where designers act as mediators between material uncertainty and algorithmic order.

4.4. Environmental and Methodological Implications

From an ecological perspective, the 22% reduction in CO2 emissions and 18% energy savings confirm the environmental potential of integrating AI-driven classification with digital fabrication. These results resonate with prior research emphasizing the environmental benefits of digital material management and circular design [35,36]. However, Granizzo advances this discourse by providing quantifiable data that links computational control to measurable sustainability outcomes, bridging the gap between theoretical claims and operational practice.

The methodology also underscores the relevance of localized production ecosystems, where material sourcing, digital modeling, and fabrication occur within a geographically constrained loop. Such regional circularity not only minimizes transportation impacts but also strengthens local economies and aesthetic identities, aligning with broader principles of sustainable territorial development.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

While the outcomes demonstrate clear potential, several limitations remain. The current dataset comprising 200 images could be expanded to include a broader range of materials and degradation states, improving the generalization capacity of the AI model. Similarly, the environmental assessment would benefit from a comprehensive LCA simulation using specialized software (SimaPro, OpenLCA) and sensitivity analysis to evaluate variable impacts such as binder selection and renewable energy integration.

Future research will focus on the automation of feedback loops between AI recognition and parametric generation, enabling adaptive design systems capable of real-time pattern optimization based on material input. Additionally, the integration of extended reality (XR) interfaces could enhance user interaction with hybrid mosaics, facilitating participatory design processes in both academic and industrial contexts.

5. Conclusions

This research presented Granizzo, a hybrid methodological framework that integrates artificial intelligence, parametric design, and digital fabrication to transform construction and demolition waste into sustainable architectural mosaics. The results demonstrated that coupling computational intelligence with circular material processes can generate measurable environmental, aesthetic, and operational benefits, providing a scalable pathway toward data-informed sustainable design.

The Random Forest classifier achieved over 90% accuracy in identifying heterogeneous construction waste fragments, validating the use of AI as an effective pre-sorting tool for material reuse. The subsequent integration of classified data into parametric workflows enabled the algorithmic generation of mosaic patterns with surface coverage rates exceeding 90%, reducing material waste and assembly time. Physical prototypes fabricated through CNC-milled molds confirmed the reproducibility and precision of the digital workflow, while the preliminary Life Cycle Assessment revealed a 22% reduction in CO2 emissions and an 18% decrease in energy consumption compared with traditional terrazzo production.

The results obtained through the hybrid AI–parametric workflow provide evidence of the system’s potential for practical implementation in architectural surface design and material reuse. The model’s accuracy above 90% demonstrates that automated classification can significantly reduce manual sorting time and material waste, supporting data-driven circular design practices. However, the study’s limitations lie in the restricted dataset size and the controlled laboratory setting, which may affect generalization to large-scale demolition environments. Future research should therefore incorporate more diverse material typologies, extended datasets, and on-site validation to assess scalability. The findings also suggest that the integration of explainable AI models within digital fabrication pipelines can facilitate reproducibility, transparency, and environmental traceability in Construction 5.0 contexts.

These quantitative outcomes also provide practical validation of the proposed workflow. The integration of AI-based material recognition within parametric and digital fabrication processes demonstrates measurable operational efficiency and material recovery potential. The approach can be adapted for other waste typologies and educational contexts, serving as a low-cost methodology to teach sustainable manufacturing and computational design. Moreover, the system’s modularity allows its implementation in small workshops and local industries, reinforcing its scalability and real-world applicability.

Beyond its quantitative outcomes, Granizzo contributes a conceptual advancement by positioning digital craftsmanship as a synergistic model where computational accuracy and human intuition coexist. The methodology demonstrates that environmental responsibility and design innovation are not opposing objectives but can be integrated through hybrid processes combining artificial and human intelligence.

Future work will focus on expanding the dataset for more diverse material typologies, implementing advanced LCA simulations, and automating feedback loops between AI recognition and generative algorithms. By bridging material reuse, digital design, and sustainability, Granizzo establishes a replicable foundation for circular architectural production and contributes to the ongoing evolution of hybrid design ecologies in the built environment.

The environmental analysis presented here should be interpreted as a preliminary scoping LCA (Phase 1 under ISO 14040/14044 [ISO 14040:2006; ISO 14044:2006]), providing indicative trends rather than exhaustive impact quantification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M.-J.; Methodology, R.M.-J., A.G.-B., B.C.-O. and S.A.-G.; Software, G.M.-J.; Validation, A.G.-B., A.M.-M., B.C.-O., C.O.-N. and S.A.-G.; Formal analysis, G.M.-J., C.O.-N. and S.A.-G.; Investigation, R.M.-J., A.G.-B. and A.M.-M.; Resources, A.M.-M.; Data curation, A.G.-B., G.M.-J., C.O.-N. and S.A.-G.; Writing—original draft, R.M.-J.; Writing—review and editing, R.M.-J., A.G.-B., G.M.-J., A.M.-M., B.C.-O., C.O.-N. and S.A.-G.; Visualization, R.M.-J. and G.M.-J.; Supervision, R.M.-J. and B.C.-O.; Project administration, R.M.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Dirección de Investigación y Desarrollo (DIDE) and to the Facultad de Diseño y Arquitectura of the Universidad Técnica de Ambato for their institutional and academic support throughout the development of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Langley, A.; Lonergan, M.; Huang, T.; Azghadi, M.R.; Mostafa, C.; Azghadi, R. Analyzing Mixed Construction and Demolition Waste in Material Recovery Facilities: Evolution, Challenges, and Applications of Computer Vision and Deep Learning. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 217, 108218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Farshadfar, Z.; Khajavi, S.H. Computer Vision-Enabled Construction Waste Sorting: A Sensitivity Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabile, P.; Radica, F.; Ranza, L.; Carroll, M.R.; Santulli, C.; Paris, E. Dimensional, Mechanical and LCA Characterization of Terrazzo Tiles along with Glass and Construction and Demolition Waste (CDW). Recent. Prog. Mater. 2021, 3, 006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, J.A.; Fúquene, C.E.; Maury-Ramírez, A. Life Cycle Assessment on Construction and Demolition Waste: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinade, O.O.; Oyedele, L.O.; Ajayi, S.O.; Bilal, M.; Alaka, H.A.; Owolabi, H.A.; Arawomo, O.O. Designing out Construction Waste Using BIM Technology: Stakeholders. Expect. Ind. Deploy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmani, M. Design Waste Mapping: A Project Life Cycle Approach. Waste Resour. Manag. 2013, 166, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Superti, V.; Houmani, C.; Hansmann, R.; Baur, I.; Binder, C.R. Strategies for a Circular Economy in the Con-Struction and Demolition Sector: Identifying the Factors Affecting the Recommendation of Recycled Concrete. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, J.; Yu, B.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J. Critical Evaluation of Construction and Demolition Waste and Associated Environmental Impacts: A Scientometric Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.S.; Yu, A.T.W.; Jaillon, L. Reducing Building Waste at Construction Sites in Hong Kong. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2004, 22, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabirifar, K.; Mojtahedi, M.; Wang, C.; Tam, V.W.Y. Construction and Demolition Waste Management Contributing Factors Coupled with Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle Strategies for Effective Waste Management: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, A.; Silvestre, J.; Costa, H.; do Carmo, R.; Júlio, E. Reducing the Environmental Impact of the End-of-Life of Buildings Depending on Interrelated Demolition Strategies, Transport Distances and Disposal Scenarios. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 82, 108197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.; Thedy, W.H.; Chong, Z.; Ng, J.L.; Moon, W.C. A Study on Recycling Waste Materials in Construction Industry. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 3, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, R.; Pahlevi, R.; Bunyamin, B. Challenges and Solutions for Using Waste Materials in Various Construction Applications. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 1, 108197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, C.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Su, Z.; Fu, B. Interaction of ACP and MDP and Its Effect on Dentin Bonding Performance. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 91, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, S.; Han, S.; Shin, Y.; Na, S. Challenges of Data Refining Process during the Artificial Intelligence De-Velopment Projects in the Architecture, Engineering and Construction Industry. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baduge, S.K.; Thilakarathna, S.; Perera, J.S.; Arashpour, M.; Sharafi, P.; Teodosio, B.; Shringi, A.; Mendis, P. Artificial Intelligence and Smart Vision for Building and Construction 4.0: Machine and Deep Learning Methods and Applications. Autom. Constr. 2022, 141, 104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.d.M.N.; Cury, A.A.; Mendes, J.C. Construction and Demolition Waste Management and Artificial Intelligence—A Systematic Review. Rev. Gestão Soc. E Ambient. 2024, 18, e08810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshadfar, Z.; Khajavi, S.H.; Mucha, T.; Tanskanen, K. Machine Learning-Based Automated Waste Sorting in the Construction Industry: A Comparative Competitiveness Case Study. Waste Manag. 2025, 194, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Chen, J.; Lu, W. Computer Vision to Recognize Construction Waste Compositions: A Novel Boundary-Aware Transformer (BAT) Model. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 305, 114405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Chen, J.; Xue, F. Using Computer Vision to Recognize Composition of Construction Waste Mixtures: A Semantic Segmentation Approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 178, 106022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.; Heo, S.; Han, S.; Shin, Y.; Lee, M. Development of an Artificial Intelligence Model to Recognise. Buildings 2022, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toğaçar, M.; Ergen, B.; Cömert, Z. Waste Classification Using AutoEncoder Network with Integrated Feature Selection Method in Convolutional Neural Network Models. Measurement 2020, 153, 107459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Ding, Y.; Colangelo, F. Advances in Construction and Demolition Waste Recycling: Management, Processing and Environmental Assessment; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Masi, S.; Moya, G.A. Integrating AI into the Creative Process Using Construction Waste Material. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Teijón-López-Zuazo, E.; Vega-Zamanillo, Á.; Calzada-Pérez, M.Á.; Robles-Miguel, Á. Use of Recycled Ag-Gregates Made from Construction and Demolition Waste in Sustainable Road Base Layers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Cherif, R.; Mahieux, P.Y.; Lux, J.; Aït-Mokhtar, A.; Bastidas-Arteaga, E. Artificial Intelligence Algorithms for Prediction and Sensitivity Analysis of Mechanical Properties of Recycled Aggregate Concrete. A Review. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, C.; Deresa, S.T.; Zhang, J. Machine Learning-Based Evaluation of Shear Capacity of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Beams. Materials 2020, 13, 4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Alwis, A.M.L.; Bazli, M.; Arashpour, M. Automated Recognition of Contaminated Construction and Demolition Wood Waste Using Deep Learning. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 219, 108278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, D.; Bucher, M.J.J.; De Wolf, C. Towards a ‘Resource Cadastre’ for a Circular Economy—Urban-Scale Building Material Detection Using Street View Imagery and Computer Vision. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 198, 107140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naboni, R.; Paoletti, I. Advanced Customization in Architectural Design and Construction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–174. [Google Scholar]

- Menges, A. Material Computation: Higher Integration in Morphogenetic Design. Archit. Des. 2012, 82, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gips, J. Shape Grammars and the Generative Specification of Painting and Sculpture; Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Eversmann, P.; Gramazio, F.; Kohler, M. Robotic Prefabrication of Timber Structures: Towards Automated Large-Scale Spatial Assembly. Constr. Robot. 2017, 1, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarevic, B. Architecture in the Digital Age Design and Manufacturing; Spon Press: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 0415278201. [Google Scholar]

- Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. Embodied Carbon Mitigation and Reduction in the Built Environment—What Does the Evidence Say? J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 181, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, M.; Hellweg, S. Measuring the Environmental Sustainability of a Circular Economy. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2019, 1–2, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.