3.1. Model Validation

In this study, on-site measurements were conducted on a university teaching building to check the validity of the simulation model. Since the simulated building was built upon a representative a typical teaching building with a four-sided atrium configuration, an actual university building with a similar architectural form was selected to ensure the reliability of the model (

Figure 6). Temperature and illuminance are key parameters that characterize the light and thermal environmental responses of a building, reflecting the accuracy of the physical model in simulating indoor thermal dynamics and daylighting performance. Therefore, the field measurements in this study focused on illuminance and time-dependent temperature variations throughout a single day. The first-floor atrium was selected as the measurement area for daylighting. Illuminance was measured at a height of 0.8 m above the floor within the designated zones. Each atrium was divided into measurement areas (Zones 1–2), with 12–15 test points in each zone used to calculate average temperature values.

Illuminance was measured using a MASTECH MS6300 Environment Multimeter (dynamic range: 0–50,000 lx; accuracy: ±(5.0% + 10) lx; resolution: 1 lx). Temperature was measured using a HOBO MX2301A Temperature and Humidity Data Logger (temperature range: −40 °C to +70 °C; temperature resolution: 0.02 °C; humidity range: 0 %RH to 100 %RH; humidity resolution: 0.01 %RH; response time: approximately 17 min for temperature and 30 s for humidity).

Illuminance measurements were conducted on 30 August 2025, at five time points: 8:00, 10:00, 12:00, 14:00, and 16:00, with each measurement completed within ten minutes. Temperature measurements were carried out on the same day from 7:00 to 19:00 at one-hour intervals in two designated zones. Over the course of the measurements, both the artificial lighting and air-conditioning systems in the teaching building were turned off. The weather on the measurement day was clear and cloudless. The meteorological data used for the building simulation experiment were obtained from the National Meteorological Science Data Center [

59], and a corresponding sky model was established based on the observed climatic and sky conditions.

In addition to on-site measurements of air temperature and illuminance, this study also investigated and calculated the annual dynamic energy use of the building. Complete monthly electricity consumption data for the year 2024 were obtained from the campus energy management office for the case-study building. The building relies on natural ventilation and is not equipped with a mechanical cooling system; in summer, indoor air movement is assisted by electric fans, while in winter space heating is pro-vided by a central district heating system. Therefore, the recorded electricity consumption primarily covers lighting, plug loads, and auxiliary equipment, and does not include electricity for air-conditioning systems. To enable a meaningful comparison between the measured data and the simulation results, the monthly electricity consumption (kWh) was normalized by the total gross floor area of the teaching building (10,829.16 m

2) to derive the monthly electricity use intensity (kWh/m

2·month). In the simulation experiments, the same operating schedules as those of the real building were adopted, and the simulated monthly electricity consumption was post-processed using the same method.

Figure 7b presents a comparison between the simulated and measured monthly electricity use intensities.

For the studied teaching building, the occupancy and operation schedule is as follows: the building is closed throughout the winter vacation (15 January to 15 February) and the summer vacation (15 July to 30 August), with no electricity use assumed during these periods. Outside the vacation periods, the building is assumed to be in use daily from 07:00 to 23:00.

According to ASHRAE Guideline 14–2014, the Mean Bias Error (MBE) and the Coefficient of Variation of the Root Mean Square Error (CV-RMSE) are explicitly recommended for evaluating the agreement between simulation results and measured data. MBE (Equation (2)) represents the systematic deviation between simulated and measured values, used to determine whether the model consistently overestimates or underestimates the results. CV-RMSE (Equation (3)) measures the overall dispersion between simulated and measured values, assessing whether the model’s fluctuations align with actual observations. A common validation criterion for temperature or illuminance simulations is MBE ≤ ±10% and CV-RMSE ≤ 30% [

60,

61].

where

denotes the measured value for model

,

denotes the simulated value for model

,

is the total number of data pairs, and

is the mean of the measured value.

As shown in

Figure 7a, the simulated and measured illuminance data exhibit similar distribution patterns, indicating that the model is capable of generating realistic results. Illuminance was measured and simulated at 5 time points throughout the day: 8:00, 10:00, 12:00, 14:00, and 16:00. Under idealized model conditions, the simulated illuminance values were consistently higher than the measured ones, leading to a more conservative optimum in the later optimization process. Based on the measured and simulated illuminance values at each point, the MBE was calculated to be 0.10742%, and the CV(RMSE) was 0.15594%.

Figure 7b presents the monthly electricity use intensity of the teaching building over the entire year. The calibration results indicate that the mean bias error (MBE) is 1.8% and the coefficient of variation of the root mean square error (CV-RMSE) is 6.5%, both falling within commonly accepted threshold values.

Figure 7c presents a comparison between the measured and simulated temperatures in the two test zones at one-hour intervals on the measurement day. The MBE and CV(RMSE) were calculated as 0.735% and 5.815%, respectively. Therefore, the deviation between the simulated and measured temperature data in this validation falls within the acceptable range.

Although the validation of the baseline near-zero energy model in this study is not yet fully complete, its energy consumption results are still according to the verified daylighting and thermal environment models. Given that the primary objective of this research is to optimize the atrium form design of teaching buildings, the energy use results are analyzed mainly as relative indicators to compare the performance differences among various design schemes, rather than to assess absolute energy levels. Therefore, when analyzing the optimal and trade-off solutions, the focus is placed on the trends and relative improvements in energy performance. In summary, the adopted model has been validated in terms of thermal and daylighting performance simulations, providing a reliable basis for relative evaluation in energy consumption analysis and multi-objective optimization.

3.3. Analysis of Pareto Front Solutions Among Optimization Objectives

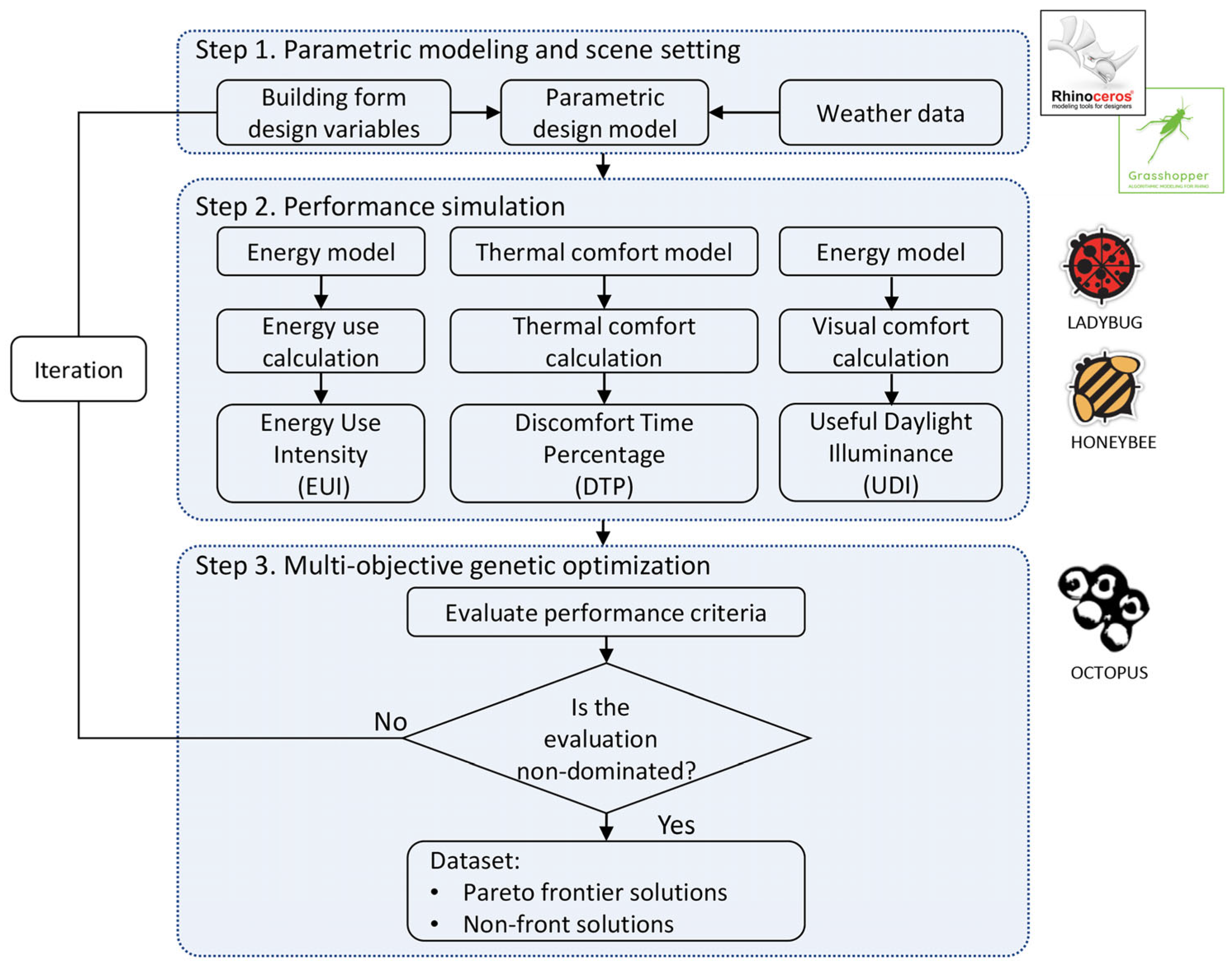

The main optimization objectives of this study are to minimize EUI and DTP while maximizing UDI.

Figure 9 illustrates the Pareto front relationships among all simulation results for EUI–DTP, EUI–UDI, and UDI–DTP in the multi-objective optimization (MOO), where the red points represent Pareto-optimal solutions.

Figure 9a shows the relationships among the three optimization objectives in the single-atrium educational building. The entire set of EUI–DTP solutions indicates a negative correlation between EUI and DTP. The scatter points exhibit a shallow U-shaped distribution, showing that when EUI is approximately 186–188 kWh/m

2·y, DTP reaches its lowest value. The Pareto front solutions demonstrate that as EUI increases, DTP decreases slightly, suggesting that a small increase in energy consumption can bring limited improvement in thermal comfort. Specifically, when EUI increases by about 10 kWh/m

2·y, DTP decreases by only 0.5–1.0%. This weak trade-off relationship indicates that the passive effect of building geometry on reducing indoor thermal discomfort is limited. Therefore, the interaction between energy use and thermal comfort is relatively indirect and exhibits nonlinear characteristics. A weak positive correlation exists between EUI and UDI. Although the overall sample does not show a clear linear relationship, the Pareto front indicates that when UDI increases, EUI also rises slightly, suggesting that the improvement of daylighting performance is often accompanied by higher energy consumption. This trend is mainly affected by the combined influence of skylight ratio and atrium geometry. A positive correlation is found between UDI and DTP, indicating that the enhancement of daylighting performance tends to reduce thermal comfort. Schemes with higher UDI values generally have larger skylight ratios, which improve the uniformity of indoor lighting but also intensify solar radiation entering the space. This leads to increased air temperature and more pronounced vertical stratification, extending the duration of thermal discomfort. When UDI exceeds 86%, DTP rises significantly to over 35%, suggesting that excessive daylighting can severely worsen the indoor thermal environment. These findings verify the inherent contradiction between visual comfort and thermal comfort in single-atrium buildings.

Figure 9b shows the relationships among the three optimization objectives in the double-atrium educational building. The relationship between EUI and DTP overall exhibits a negative correlation, but the scatter distribution is more dispersed. Most Pareto front solutions are concentrated in the range of EUI = 187–188 kWh/m

2·y and DTP ≈ 37%. Regarding the relationship between UDI and EUI, the double-atrium configuration shows a slight positive correlation. When energy consumption is relatively low, UDI is approximately 85–86%; as EUI increases to 189–190 kWh/m

2·y, UDI rises to 87–88%. This indicates that the enhancement of daylighting performance is often accompanied by increased energy consumption. In particular, in double-atrium configurations, large skylight areas and transparent enclosures improve daylighting but simultaneously increase cooling and heat transfer loads. A clear positive correlation is also observed between UDI and DTP. When DTP increases from about 37.0% to 39.0%, UDI simultaneously rises from about 82% to 87–88%, indicating that improving daylighting performance also increases the proportion of thermal discomfort.

3.4. Analysis of Optimal Solutions

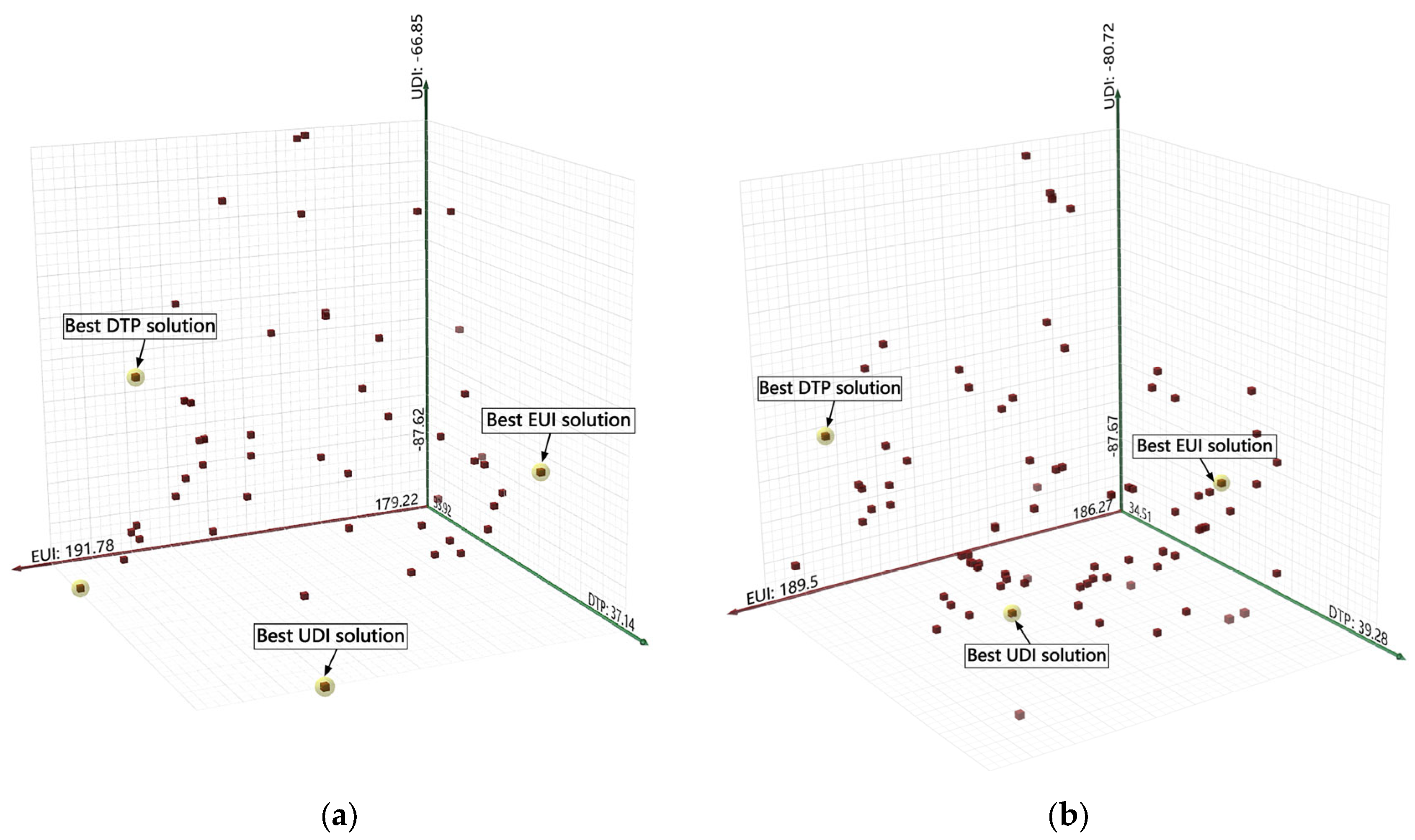

Figure 10 presents the Pareto front and the UDI, EUI, and DTP scatter plots obtained from the final generation. Based on Equation (1), the optimal and trade-off values of UDI, EUI, and DTP were calculated. Architects can select the most appropriate solution according to specific design objectives and project requirements.

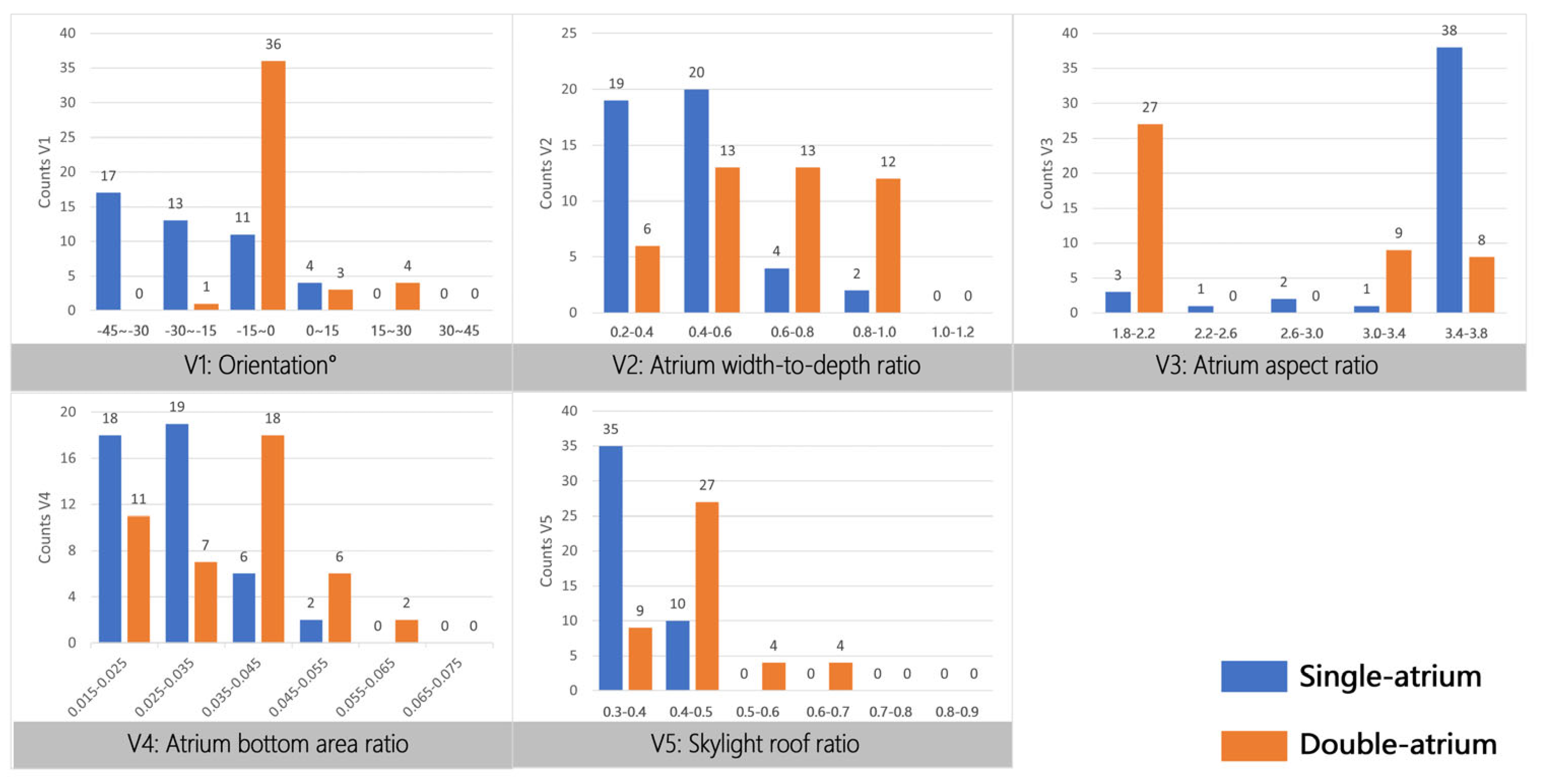

Figure 11 presents the distribution of atrium design variable values within the Pareto-optimal solutions. As shown in the figure, the optimal orientation solutions for the single-atrium building are relatively dispersed, primarily concentrated within the range of −45° to −15° (southeast-oriented). This indicates that single-atrium configurations are more sensitive to orientation, as a southeast-facing layout provides more stable daylighting and thermal balance during the morning while avoiding overheating caused by afternoon west solar exposure. In contrast, the double-atrium building shows optimal solutions that are highly concentrated within the −15° to 0° range (near-south orientation), suggesting that when two atriums are located symmetrically on both sides of the building’s central axis, maintaining an overall south-facing orientation ensures balanced daylight distribution and a more stable internal thermal environment. Therefore, single-atrium configurations rely more on a southeast orientation to regulate light and heat performance, whereas double-atrium configurations perform best near the south-facing direction.

Regarding the atrium width-to-depth ratio, the optimal solutions for single-atrium buildings are primarily distributed within the 0.2–0.6 range, indicating that relatively “elongated” atrium spaces achieve a better balance between daylighting and thermal comfort. In contrast, the optimal solutions for double-atrium buildings are concentrated within the 0.6–1.0 range, suggesting that “nearly square” atriums contribute to balanced light and thermal distribution between the two atriums. The single-atrium configuration tends to adopt a more elongated layout to mitigate heat accumulation, while the double-atrium configuration favors a more square plan to achieve uniform light distribution.

For the atrium height-to-width ratio, the optimal solutions for single-atrium buildings are concentrated within the 3.4–3.8 range, representing a tall and narrow vertical space. This configuration enhances the stack effect, promotes the upward movement and discharge of warm air, and utilizes reflected light from the upper portion to improve illuminance at the lower level. In contrast, the optimal solutions for double-atrium buildings are concentrated within the 1.8–2.2 range, corresponding to a lower and wider space, which helps avoid excessive vertical temperature stratification and maintains balanced ventilation between the two atriums.

Regarding the atrium bottom area ratio, the optimal solutions for single-atrium buildings are concentrated within the 2–3% range, while in double-atrium buildings, the optimal bottom area ratio for each individual atrium is concentrated within 1.8–2.2%. The optimal area ratios for individual atriums in both cases are therefore comparable. This suggests that double-atrium configurations do not rely on a larger single atrium but instead achieve spatial distribution of daylighting and redundant ventilation through two medium-sized atriums. This approach maintains high UDI values while reducing the sensitivity of EUI and DTP to variations in bottom area ratio, resulting in more stable performance.

With regard to the skylight–roof ratio, the optimal solutions for single-atrium buildings are concentrated within the 0.3–0.4 range, while those for double-atrium buildings are concentrated within the 0.4–0.5 range. This indicates that double-atrium configurations require a higher skylight opening ratio to maintain sufficient daylight penetration depth and airflow, whereas for single-atrium configurations, an excessively high skylight ratio can easily lead to overheating in the upper zone and increased energy consumption, thus resulting in a relatively lower optimal value.

By comparing the three Pareto-optimal designs and the balanced trade-off design with the reference scheme, the performance improvements achieved through optimization can be clearly identified, as shown in

Table 10 and

Table 11. The reference solution is constructed from the survey data of 25 atrium teaching buildings in Xi’an, by assigning the key geometric variables to the median values of the sample and selecting a configuration that closely represents a typical code-compliant case.

For the single-atrium configuration, the optimization results reveal distinct performance improvements compared with the reference scheme. The best EUI solution achieves a substantial 4.9% reduction in energy use intensity, accompanied by a slight 1.3% improvement in thermal comfort and increasing UDI by about 2.0%. This reduction results primarily from a narrower and taller atrium geometry combined with a moderate skylight ratio and a near-south-east orientation. Such a configuration enhances buoyancy-driven ventilation and reduces envelope heat gain while maintaining sufficient daylight via vertical reflections. The best DTP solution further minimizes thermal discomfort by reducing the bottom area ratio and skylight opening, combined with an eastward orientation that limits solar exposure. However, these changes lead to a UDI decrease about 9.2%, implying that thermal comfort is achieved at the cost of daylight quality and lighting energy demand. In contrast, the best UDI case improves daylight performance by 5.2% through a wider and shallower atrium and a large skylight opening, but causes an increase in DTP due to indoor overheating. The trade-off solution (y = 35.21) closely aligns with the best EUI configuration, balancing EUI = 179.46 kWh/m2·y, DTP = 35.04%, and UDI = 83.23%. Overall, the single-atrium model achieves the best comprehensive efficiency under a tall and slender form with a moderate skylight ratio, effectively reducing energy use while keeping comfort and daylight performance at acceptable levels.

For the double-atrium configuration, the overall optimization performance is more balanced but less sensitive to geometry changes. Compared with its reference case, the best EUI solution yields a 1.7% reduction in energy consumption, a 2.4% increase in daylight performance, but a 1.3% deterioration in thermal comfort. This outcome corresponds to relatively tall atrium, and a large skylight ratio. The larger skylight enhances daylight and reduces lighting demand, but also increases solar heat gain, causing a rise in discomfort hours. The best DTP solution attempts to mitigate thermal stress by reducing the skylight and bottom area ratio, yet the DTP decreased by 2.75% compared to the reference value. Conversely, the best UDI case achieves the highest daylight performance through a wide and low atrium and a large skylight opening, but at the cost of increased overheating. The trade-off solution (y = 39.37) coincides with the best EUI configuration, featuring EUI = 187.04 kWh/m2·y, DTP = 37.72%, and UDI = 85.32%, suggesting that in double-atrium designs, further energy reduction or daylight improvement inevitably sacrifices thermal comfort.

Overall, the optimization results highlight a clear distinction between the two typologies. The single-atrium configuration exhibits a stronger optimization potential, achieving significant energy savings with minimal daylight or comfort losses under a slender vertical form and moderate skylight opening. In contrast, the double-atrium configuration provides more balanced daylight distribution and visual comfort, but its dual-lightwell structure increases the internal heat load, limiting further improvement in thermal comfort. Hence, while the double-atrium design favors daylight utilization, the optimized single-atrium layouts in this study tend to achieve lower simulated energy use with acceptable thermal comfort under the specific modeling assumptions for cold-region educational buildings.