1. Introduction

Concrete is the most prevalent construction material globally due to its versatility, workability, and ability to form complex shapes for structural and non-structural members. However, despite its widespread use, plain concrete exhibits inherent limitations, including its weakness in tension, low resistance to cracking, and brittleness resulting from internal microcracking. These limitations challenge the long-term durability and performance of concrete structures, necessitating advancements in concrete technology to meet the diverse structural and durability demands in civil engineering. Plain concrete exhibits limitations in qualities such as tensile (flexural) strength, post-cracking behavior, fatigue resistance, and susceptibility to brittle failure [

1,

2]. The inherent brittleness of concrete, particularly as its strength increases, poses a significant challenge to its application as a construction material. This increased strength often results in reduced elasticity, representing a critical limitation. However, incorporating short fibers effectively balances strength and ductility in concrete [

3]. The initiation of microcracks, which contribute to the material’s inherent mechanical weaknesses, can be mitigated by incorporating various fiber types [

4].

The inherent brittleness of plain concrete is primarily due to its low tensile strength and its propensity to crack under loading. Traditional methods of enhancing concrete properties, such as increasing the cement content, often yield diminishing returns or raise environmental concerns due to the high carbon footprint associated with cement production. Therefore, alternative methods, such as incorporating fibers, have gained significant attention in recent years to improve concrete’s mechanical and durability properties. Fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC) is an advanced form of concrete that incorporates fiber into the mix to enhance its performance. These fibers, which can be made of steel, polypropylene, glass, or synthetic materials, help bridge cracks, enhance crack resistance, and improve the overall toughness of the material [

5]. Hybrid fibers have emerged as a significant innovation in materials science, particularly for enhancing the mechanical properties of construction materials like concrete and composites. The integration of hybrid fibers, which often combine various types (such as steel, polypropylene, or glass), optimizes the bridging mechanism that alleviates crack propagation under stress. This bridging mechanism is vital, as it not only helps arrest crack growth but also plays a crucial role in improving key mechanical properties. One area of improvement is flexural strength. The presence of hybrid fibers significantly increases the material’s resistance to bending forces. This capability is crucial in structural applications where components are subjected to fluctuating loads. Alongside flexural strength, hybrid fibers also enhance splitting tensile strength, enabling the material to withstand tensile stresses that can lead to separation or failure [

6,

7].

In terms of flexural toughness, hybrid fibers significantly enhance a material’s ability to absorb energy during deformation, thereby resisting fracture under bending loads. This quality is essential in dynamic loading situations, such as earthquake-prone areas or environments prone to impact. Despite the promising attributes of hybrid fibers, research gaps remain that need to be addressed for optimal application. For instance, there is insufficient understanding of how the combination of different fiber types affects the interaction mechanism at the microstructural level. Studies focusing on the specific bonding characteristics between various fibers and the matrix can reveal how to enhance performance further [

8,

9,

10].

Furthermore, while hybrid fibers have demonstrated superior effectiveness in mitigating both micro- and macro-cracks, the optimal ratios and types of fibers for specific applications remain largely unexplored. There is a pressing need for comprehensive studies to identify the ideal combinations of hybrid fibers tailored to various environmental conditions, loading scenarios, and precise material requirements [

6,

7].

Additionally, a significant gap exists in the investigation of the long-term durability of hybrid fiber-reinforced materials. Although current research indicates improvements in immediate mechanical properties, it is essential to understand the long-term behavior of these materials under varying environmental conditions, fatigue loading, and moisture exposure to accurately predict their performance over the lifespan of structures [

6,

7].

Finally, the economic implications of incorporating hybrid fibers into construction materials also require further exploration. While these fibers hold promise for enhanced durability and reduced maintenance costs, conducting a cost–benefit analysis comparing traditional materials with hybrid fiber-reinforced alternatives would enable engineers and construction professionals to make informed decisions about material selection [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

In summary, hybrid fibers offer a promising pathway for improving material performance. However, addressing these research gaps through targeted studies can lead to broader applications and the development of innovative material solutions in construction and beyond [

6,

7].

The efficiency of fiber-reinforced concrete depends on the type, content, and distribution of fibers. Experimental studies show that combining steel and polypropylene fibers can enhance mechanical properties. For one-way slabs, optimal performance is achieved with 0.7% steel and 0.9% polypropylene fibers, maximizing load capacity and flexibility. In contrast, two-way slabs perform best with 0.9% steel and 0.1% polypropylene fibers, improving load-bearing capacity and cracking resistance. These findings emphasize the need for tailored fiber proportions based on slab type and loading conditions for optimal results [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The observed synergy between steel and polypropylene fibers suggests an optimal balance between the two materials that varies with slab configuration and applied loading conditions. The performance improvements of fiber-reinforced slabs can be attributed to the complementary mechanisms provided by each fiber type. While steel fibers improve the slab’s strength and toughness, polypropylene fibers control crack formation and improve the post-cracking behavior, resulting in a more resilient and durable concrete structure [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Steel fibers have been proven to effectively enhance the flexibility and crack resistance of concrete. Additionally, shrinkage cracks can be mitigated by incorporating steel and glass fibers at a volumetric ratio of 0.1% [

19]. However, using a combination of fibers has proven more effective in improving a range of mechanical properties and the impact and blast resistance of concrete under both normal and elevated temperatures [

20,

21,

22]. Hybrid fiber-cementitious composites enhance the mechanical properties and durability of concrete structures under various loading conditions:

- i.

Cyclic Loading: These composites distribute stress evenly, increasing resistance to cracking and fatigue.

- ii.

Seismic Loading: They improve ductility and energy absorption, allowing structures to withstand lateral forces during earthquakes.

- iii.

Static Loading: By boosting tensile strength, they enhance the load-bearing capacity of concrete.

- iv.

Impact Loading: The added fibers increase toughness, helping concrete absorb energy from sudden impacts without significant damage.

These advanced composite materials demonstrate significant potential for retrofitting both masonry and concrete structures. They not only enhance the load-bearing capacity of these buildings but also extend their service life, ensuring that they remain safe and functional for years to come. Additionally, these composites are designed to preserve the original aesthetics of the structures, allowing for seamless integration with the existing architecture while improving overall stability and performance. Their versatility makes them valuable in both new construction and structural rehabilitation [

8,

9,

10].

Concrete behavior is ruled considerably by its compressive strength, but tensile strength also plays a significant role in determining the appearance and durability of concrete. Fibers are added to enhance flexural and tensile strengths, the crack-arresting system, and the fundamental matrix’s post-cracking ductile behavior. To control plastic and drying shrinkage cracking, a volumetric proportion of 0.1% polypropylene and glass fibers was found adequate [

23,

24].

In ordinary concrete, where compaction is achieved using mechanical vibrators, the incorporation of fibers is considered a reliable and widely utilized approach to mitigate cracking caused by paste contraction, mainly through the use of thin artificial fibers at a volumetric content of less than 0.5% [

25]. Experimental research on fiber-reinforced concrete has demonstrated that increasing the fiber volume significantly enhances its mechanical properties, including compressive, tensile, and bending strengths. These improvements are attributed to the fibers’ ability to reinforce the concrete matrix and resist crack propagation under various stress conditions. However, this enhancement comes at the cost of reduced workability, as the increased fiber content hinders the smooth flow and compaction of the concrete mix. Consequently, achieving an optimal balance between mechanical performance and workability requires careful consideration of the fiber volume in the mix design [

26].

Polypropylene has played a vital role in improving construction quality by reducing deflection and, consequently, providing greater structural stability. Polypropylene fibers have been shown to reduce concrete spalling. Surface cracks typically form when the internal vapor pressure within the concrete exceeds the surface pressure [

27,

28]. Cracks frequently form within the first hour after concrete is poured into the mold, even before it has gained sufficient strength. These early-stage cracks are critical entry points for harmful substances, such as water, chlorides, and other chemicals, that can infiltrate the concrete matrix. Over time, this infiltration can lead to severe issues, such as spalling of the concrete surface or corrosion of the embedded reinforcement. Such degradation not only undermines the durability of the concrete but also compromises its structural integrity, significantly affecting its long-term performance and safety [

29,

30,

31,

32].

The compressive strength of the concrete is slightly affected by the increase in polypropylene and glass fibers [

33,

34,

35,

36]. The most optimal results were obtained with volume ratios of 1.5 kg/m

3 and 2 kg/m

3. Mixing polypropylene fibers has slowed degradation, reduced permeability, and reduced shrinkage and expansion of concrete. This approach contributes to maintaining the structure in a more serviceable condition [

37]. The size and quantity of steel fibers significantly influence the mechanical properties of hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete (HFRC). Research indicates that even a small addition of steel fibers can lead to a noticeable increase in concrete compressive strength, as the fibers effectively distribute and mitigate internal stresses. However, the impact on tensile strength is comparatively modest, as the fibers primarily contribute to crack bridging and resistance rather than directly increasing the tensile capacity [

38]. This highlights the importance of optimizing fiber size and content to achieve desired performance improvements in HFRC [

39]. The highest compressive strength was achieved with a mix of 75% steel fibers and 25% polypropylene fibers by weight, due to the high modulus of elasticity of steel and the low modulus of elasticity of polypropylene fibers. It was also suggested that increasing the fiber content enhances concrete’s tensile strength. Using a specific fiber blend resulted in a notable improvement in split tensile strength [

40]. Polypropylene fibers at a 0.1% volume fraction were less effective for on-grade slabs, whereas a 0.5% volume fraction of polypropylene fibers provided significantly better resistance to impact loading [

41].

The type, content, and distribution of fibers within the concrete matrix significantly influence the performance of fiber-reinforced concrete. Experimental investigations have extensively examined the optimal steel and polypropylene fiber blends to maximize mechanical properties for various applications [

42,

43]. A significant relationship exists between these two fiber types, in which the presence of one enhances the performance of the other. Steel fibers provide strength and stiffness, thereby improving load-bearing capacity, while polypropylene fibers contribute to crack resistance and energy absorption. This unique interaction enables tailored combinations to meet specific structural demands, demonstrating the importance of balancing fiber characteristics for superior concrete performance [

44,

45,

46]. The investigation of the effects of SF and PF suggests an optimal balance between these materials that varies with slab configuration and applied loading conditions. The performance improvements of fiber-reinforced slabs can be attributed to the complementary mechanisms provided by each fiber type. While steel fibers improve the slab’s strength and toughness, polypropylene fibers control crack formation and improve the post-cracking behavior, resulting in a more resilient and durable concrete structure [

47,

48,

49,

50].

This research directly addresses these gaps by conducting a systematic experimental investigation on 42 reinforced concrete slabs (21 one-way and 21 two-way) with varying SF–PF volumetric ratios. Unlike previous studies, this work:

Identifies and compares optimal hybrid fiber proportions for both one-way and two-way slabs, recognizing that each slab geometry produces different crack patterns and stress trajectories.

Quantifies hybrid fiber synergy through full-scale structural testing, evaluating first-crack load, ultimate load, deflection response, and post-cracking ductility.

Demonstrates that optimal fiber combinations differ between slab types, providing new insight into how multidirectional load transfer in two-way slabs enhances the effectiveness of hybrid fibers.

Offers performance-based guidance for selecting hybrid fiber dosages that balance mechanical enhancement and workability, addressing a recurring problem in the literature.

The findings show that the combination of 0.7% SF + 0.9% PF yields the best performance for one-way slabs, while 0.9% SF + 0.1% PF is optimal for two-way slabs. These results reveal, for the first time, that the structural efficiency of hybrid fibers is strongly dependent on slab type and the associated flexural stress distribution, demonstrating a measurable, previously undocumented fiber–geometry interaction.

Overall, this study advances the understanding of hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete slabs by establishing clear, experimentally verified optimal SF–PF configurations, clarifying the conditions under which hybrid fibers are most effective, and providing a structural-scale evaluation of hybrid synergy under different bending systems. The work contributes novel, practical guidance for engineers seeking to enhance slab performance using hybrid fibers.

This research investigates the impact of hybrid fibers on the structural performance of one-way and two-way slabs. Additionally, the study aims to determine the optimal content of steel fibers combined with polypropylene fibers and to evaluate their impact on the flexural performance of slabs, including initial cracking, ultimate cracking, loading capacity at both initial and ultimate failure, and corresponding deflections. This study holds significant value for the construction industry, as it comprehensively analyzes key parameters, including ultimate load capacity, deflection, cracking behavior, and ductility, in slabs enhanced through the integration of hybrid fibers. Adding fibers to concrete modifies its mechanical properties by improving crack resistance, tensile strength, and fracture toughness. Fiber types and their proportions significantly influence concrete performance. Among the various types of fibers used in concrete, steel and polypropylene fibers have attracted significant attention for their distinct characteristics and effects on concrete’s structural behavior.

The primary goal of this research was to identify performance-optimized hybrid steel–polypropylene fiber combinations for reinforced concrete one-way and two-way slabs, with a specific focus on quantifying how different volumetric ratios influence load capacity, cracking behavior, ductility, and overall flexural performance. This objective was fully achieved through the systematic testing of 42 slabs, which demonstrated that optimal fiber proportions differ between slab types—0.7% SF + 0.9% PF for one-way slabs and 0.9% SF + 0.1% PF for two-way slabs—and that hybridization significantly enhances first-crack load, ultimate load, and deflection capacity. These findings not only confirm the effectiveness of hybrid fibers in improving mechanical behavior but also establish clear parameter boundaries and optimal dosage limits, providing a validated basis for future research. Building on this work, further studies are warranted to examine long-term durability, fiber–matrix interaction mechanisms at the microstructural level, and the performance of optimized hybrid mixes under environmental cycling, fatigue loading, and full-scale structural applications, enabling broader practical adoption of hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete systems.

3. Results and Discussions

For one-way slabs, the observed behavior did not exhibit a consistent trend. Specifically, in the case of specimen SM21, which contained the highest concentration of steel and polypropylene fibers, initial cracking occurred at a relatively low load of 56.65 kN, significantly lower than the load sustained by the control specimen. Conversely, specimen SM3, with only 0.7% steel and 0.3% polypropylene fibers, demonstrated improved performance, withstanding a load of 84.13 kN before cracking. The highest load at the onset of cracking was recorded for specimen SM6, which reached 90.25 kN. The complete set of experimental results is detailed in

Table 6. Applying load using a loading jack on two-way slabs resulted in the observation of flexural cracks, indicating the onset of the yielding zone. These cracking loads indicate the initiation of structural failure. A comparative analysis revealed that a specific ratio performed best across each fiber combination, highlighting the synergistic effect of steel and polypropylene fibers. This indicates that an optimal fiber volumetric ratio is essential to achieve maximum strength.

Figure 5 compares first-crack loads corresponding to various steel and polypropylene fiber volumetric ratios.

The comparison results show that including SF and PF significantly improves the concrete’s strength compared to the control specimen. The SM12 mix, with a fiber combination of 0.9% SF and 0.1% PF, demonstrated the highest resistance to cracking, with the first crack occurring at 112 kN, much higher than in the control specimen, which cracked at 35.84 kN. This represents a 213% increase in strength for the SM12 mix. Other mixes, such as SM4, SM9, and SM18, showed first-crack loads of 89.6 kN, 67.2 kN, and 89.6 kN, resulting in strength improvements of 150%, 88%, and 150%, respectively. These results highlight the significant performance enhancement provided by the hybrid fiber reinforcement. The final load capacity for each slab type is detailed in

Figure 5.

Following the appearance of the first cracks, the one-way slab specimens exhibited progressive failure. After the cracking initiation, the steel fibers effectively created a bridging mechanism, facilitating load transmission across the cracks. This mechanism enhanced the load-carrying capacity of the specimens. Concurrently, the polypropylene fibers improved elastic behavior, resulting in increased deflection. The experimental data on load-carrying capacities and the corresponding deflections at the onset of cracking and ultimate crushing are presented in

Figure 5.

In two-way slabs, failure primarily manifested as flexural cracking, with cracks originating at the slab edges and propagating toward them. This mode of failure indicates that the slabs experienced significant bending stresses, leading to crack formation in the tensile zone. As the applied load exceeded the material’s capacity to withstand bending, the cracks expanded, ultimately reaching the edges—a typical failure pattern for slabs subjected to flexural loading. This behavior highlights the critical role of reinforcement and the fibers’ capacity to reduce crack formation and enhance load-bearing capability. An increase in load-carrying capacity was observed, ranging from 5.76% to 55.0%, except for slabs SM19 and SM21. These specimens demonstrated decreases in ultimate strength of 5.56% and 34.74%, respectively, attributed to fiber flocculation, balling action, improper mixing, and concrete bleeding. The trends observed align with the recorded loads at the initiation of cracking, as presented in

Figure 5.

The data in the graph indicates a consistent trend across all groups: the load-carrying capacity increases to a specific fiber ratio before declining. This pattern is observed uniformly across all groups. A comparative analysis shows that adding steel and polypropylene fibers increases concrete strength relative to the control specimen. The SM12 mix with a fiber ratio of 0.9% steel fibers (SF) and 0.1% polypropylene fibers (PF) exhibited the highest ultimate resistance, withstanding a load of 223.93 kN before complete failure. In comparison, the control specimen, SM1, failed at 161.28 kN, representing a 40.36% increase in strength over SM12. Other specimens, SM4, SM9, and SM18, recorded ultimate loads of 189.76 kN, 221.21 kN, and 208.11 kN, corresponding to strength increases of 18.94%, 38.66%, and 30.45%, respectively, as presented in

Figure 5.

First and Ultimate Stage as per Deflection

Incorporating polypropylene fibers resulted in a substantial increase in the deflection observed in one-way slab specimens compared to the control specimen (SM1). The maximum deflection, reaching 18.9 mm, was recorded for the specimen SM6, which contained 0.7% steel and 0.9% polypropylene fibers. Experimental findings revealed that higher proportions of polypropylene fibers enhanced the elastic behavior of concrete. However, the internal cohesive forces between concrete particles remained unchanged. Consequently, excessive deflection may disrupt particle bonds, forming a fissure plane and eventually leading to concrete spalling. The inclusion of steel fibers mitigates this effect to some extent by enabling load transmission across the fissure plane, thereby maintaining load distribution over the entire span of the specimen. The optimal synergistic effect is attained through a strategic combination of steel and polypropylene fibers, wherein the complementary properties of both materials contribute to improved load-carrying capacity and enhanced deflection performance, as illustrated

Figure 6.

Deflection behavior in the two-way slabs was evaluated during load application using a Linear Variable Differential Transformer (LVDT) positioned at the bottom center of each slab. Deflection readings were recorded immediately after the first crack appeared for each slab type, as illustrated in

Figure 6. Observations during testing revealed that cracks formed at the slab’s center and consistently propagated outward toward the periphery.

The maximum deflection at the first crack load was observed for the SM12 specimen, containing 0.9% steel fibers (SF) and 0.1% polypropylene fibers (PF), which exhibited a 44.81% higher deflection than the control specimen (SM1). The control specimen deflected 2.832 mm. Including steel fibers enhanced the slab’s stiffness, while adding polypropylene fibers increased deflection, enabling better strain absorption. This enhancement indicates a significant improvement in the modulus of resilience and toughness, both critical flexural properties of concrete. The modulus of resilience is the material’s ability to absorb and release energy under stress, while toughness is the concrete’s capacity to withstand energy absorption before failure. The ultimate deflection, the maximum deflection observed at the highest load capacity before failure, was measured for all slab specimens. These deflection values provide essential insights into the slabs’ behavior under stress, reflecting their ability to deform and resist failure under applied loads. The results are illustrated in

Figure 6, highlighting the differences in deflection performance across the various slab specimens.

The deflection observed at the first crack in the SM12 slab surpassed that of all other slabs. Additionally, at ultimate loading capacity, the SM12 specimen—which included 0.9% steel fibers (SF) and 0.1% polypropylene fibers (PF) by volume of concrete—exhibited the highest deflection among all specimens tested. This behavior can be attributed to the SM12 slab’s enhanced load-carrying capacity. The maximum deflection recorded at the ultimate crack load for SM12 was 15.42 mm, representing a 35.19% increase compared to the 11.03 mm deflection of the control specimen (SM1). Flexural loading resulted in significant deflection, as measured with an LVDT. At the first crack load, the SM12 slab displayed a 44.81% increase in deflection compared to the control slab, while at the ultimate crack load, the increase was 35.19%. In terms of load-carrying capacity, the SM12 slab demonstrated remarkable improvements, showcasing increases of 213% at the first-crack load and 50% at the ultimate-crack load relative to the control mix (SM1). These findings underscore the substantial impact of the optimized fiber blend (0.9% SF + 0.1% PF) on enhancing both deflection and load-carrying performance, as presented in

Figure 6.

Incorporating polypropylene fibers resulted in a significant increase in deflection compared to the control specimen. The maximum deflection, reaching 15.42 mm, was observed in the SM12 specimen. Experimental results suggest that higher proportions of polypropylene fibers enhance the elastic behavior of concrete. However, the cohesive forces between concrete particles remain unchanged. Consequently, excessive deflection can occasionally disrupt particle bonding, forming a fissure plane that may lead to concrete spalling. Steel fibers mitigate this effect to some extent by facilitating load transfer across the fissure plane, enabling the specimen to distribute the load over its entire span. This synergistic effect, however, is achievable only with an optimal blend of fibers where steel and polypropylene fibers complement each other. Such a combination enhances the load-carrying capacity and improves the deflection performance of the concrete, ensuring balanced structural behavior, as presented in

Figure 6.

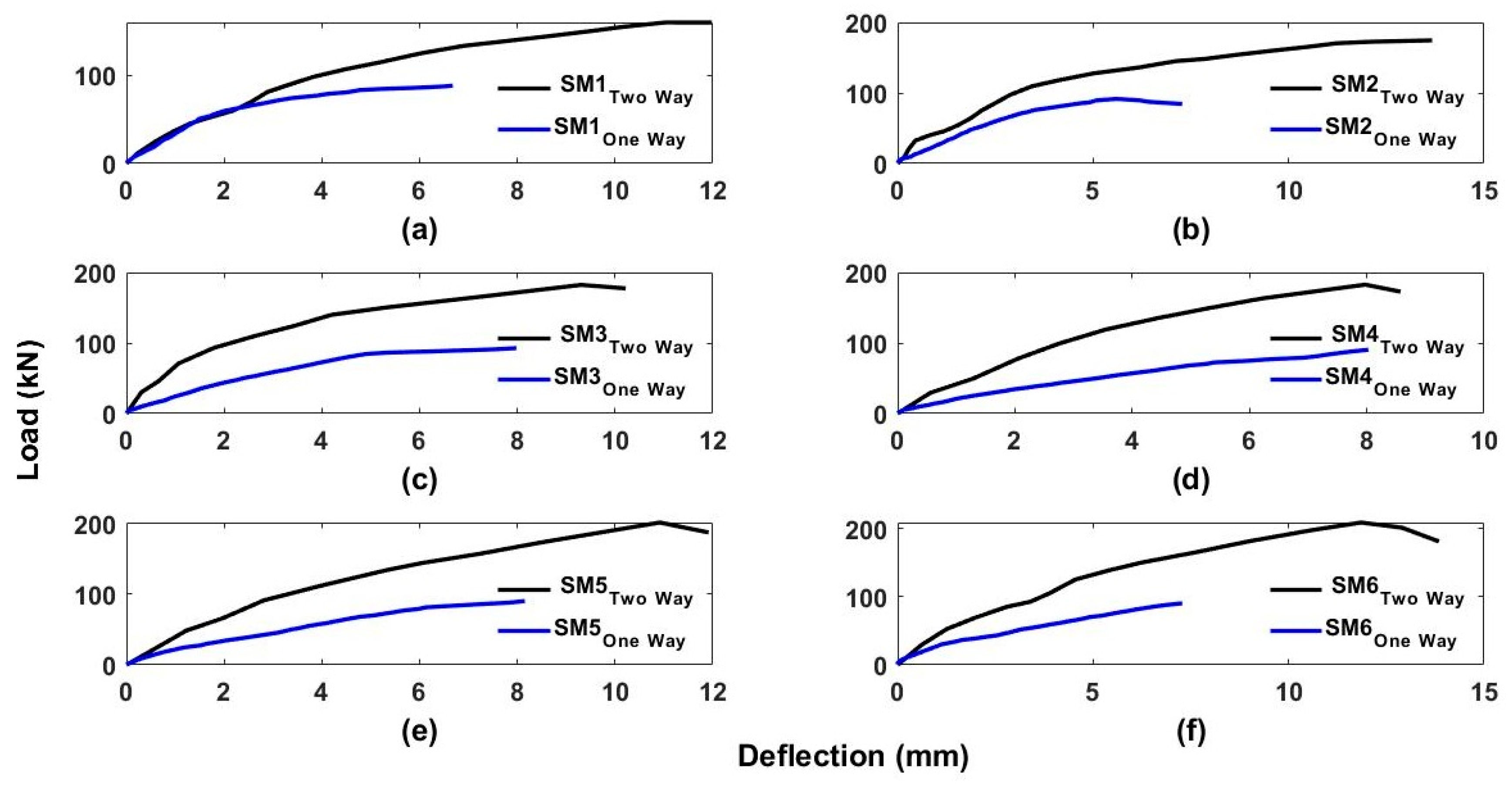

4. Comparison of 1-Way and 2-Way Behavior

4.1. Group 1: SF (0.7%) with PF % (0.1%, 0.3%, 0.5%, 0.7%, and 0.9%)

Figure 7 illustrates the load-deflection curves for one-way and two-way slabs for Group 1 with different PF % (0.1%, 0.3%, 0.5%, 0.7%, and 0.9%) but the same SF 0.7%. The experimental results for one-way slabs did not reveal a consistent trend regarding ultimate loading capacity. Different fiber blends yielded varying failure modes, including cracking, and ultimately resulted in different failure loads. For instance, specimen SM2, which exhibited a lower initial cracking load than the control specimen, required almost the same amount of loading to reach failure. Conversely, SM5 experienced its first crack at a lower load than SM4 and SM6, and failed at a lower load than either of them. The maximum load of 117.29 kN was attained by specimen SM6, which contained 0.7% steel fibers and 0.9% polypropylene fibers, as shown in

Figure 7. Notably, SM6 also demonstrated the highest flexibility, with a maximum deflection of 18.9 mm, as shown in

Figure 7 and the same fact can be witnessed in crack patterns in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

The crack patterns for one-way and two-way slabs in Group 1, with PF percentages ranging from 0.1% to 0.9% and a constant SF content of 0.7%, were carefully analyzed during testing. Examining the crack patterns revealed that the addition of polypropylene fibers significantly influenced the development and propagation of cracks. In particular, the use of polypropylene fibers resulted in a substantial increase in the deflection of the specimens compared to the control specimen. This enhancement in deflection can be attributed to the fibers’ ability to improve crack resistance and energy absorption, thereby enhancing the concrete’s overall toughness and resilience. The crack patterns also showed that polypropylene fibers helped in distributing the stresses more evenly, reducing the formation of large, localized cracks and improving the slab’s overall performance under load, as described by

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

Experimental results indicate that increasing the proportion of polypropylene fibers enhances concrete’s elastic behavior. However, the cohesive forces between concrete particles remain unchanged, meaning that excessive deflection can eventually exceed the tensile capacity of the concrete, leading to the formation of a fissure plane and subsequent spalling. Adding steel fibers mitigates this effect, delaying the failure process and prolonging the deformation phase. Steel fibers facilitate load transmission across the fissure plane, allowing the specimen to distribute the load evenly over its entire span. This enhanced performance is most effectively achieved when both fibers complement each other in an optimal blend, resulting in improved load-carrying capacity and deflection. The cracks in the two-way slabs predominantly developed on the tension side, progressing diagonally and gradually increasing through the final stages of loading. In specimen SM1, without adding fibers, cracks were produced in only one diagonal direction at a relatively low load for both first and ultimate cracking. In all other specimens, the cracks were in both diagonal directions except the specimen SM3, which was in the expected direction to the slab edges, as illustrated in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

This performance can be attributed to a complementary fiber-level mechanism. The polypropylene fibers, being numerous and finely distributed, are highly effective at controlling micro-crack initiation and growth within the cementitious matrix. This micro-crack control allows the concrete to sustain higher stresses before localized damage coalesces into a critical macro-crack. Once a macro-crack forms, the higher modulus steel fibers engage, providing robust bridging across the crack faces. Their primary role is to resist crack opening through pull-out resistance, which requires substantial energy and translates into the high post-cracking load capacity and large deflection observed in SM6. Therefore, the optimal combination of 0.7% SF and 0.9% PF creates a multi-scale defense: polypropylene fibers enhance the pre-cracking integrity and delay the onset of major cracking, while steel fibers provide the post-cracking ductility and strength, resulting in superior overall toughness. The crack patterns in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 visually corroborate this mechanism. In hybrid specimens, cracks were finer, more numerous, and distributed more evenly compared to the few, wide cracks in the control specimen (SM1). This indicates that the polypropylene fibers effectively distributed stresses, preventing localized failure. The excessive deflection in some high-PF mixes without sufficient steel fibers can lead to a loss of cohesion and spalling; however, the presence of 0.7% SF in SM6 provided adequate bridging to transmit loads across cracks, delaying this failure and allowing for the large, ductile deflection.

4.2. Group 2: SF (0.8%) with PF % (0.1%, 0.3%, 0.5%, 0.7%, and 0.9%)

Figure 10 presents structural elements’ load-deflection behavior under two-way and one-way loading conditions, highlighting the comparative performance of six specimens labeled SM1, SM7, SM8, SM9, SM10, and SM11, for Group 2 with different PF % (0.1%, 0.3%, 0.5%, 0.7%, and 0.9%) but the same SF 0.8%. In all cases, the load (kN) is plotted on the vertical axis against deflection (mm) on the horizontal axis, and the results show that the two-way loading condition (black curves) consistently performs better than the one-way loading condition (blue). The two-way loaded elements display significantly higher load-carrying capacity, as evidenced by their ability to sustain larger loads before failure. They also show greater stiffness, reflected in the steeper slope of the initial portion of the curves. This indicates that two-way loading distributes the applied forces more efficiently, resulting in reduced deflection at similar load levels and improved overall structural capacity. In contrast, the one-way-loaded specimens exhibit lower load capacities and greater deflections, suggesting a less effective load distribution mechanism. Each subfigure reinforces this trend, with two-way loaded specimens achieving noticeably better performance across all cases. This comparison underscores the structural advantage of two-way loading, demonstrating its ability to enhance both the load-bearing capacity and stiffness of the tested elements. The maximum load of 200 kN was attained by specimen SM9, which contained 0.8% steel fibers and 0.5% polypropylene fibers for the two-way slab, and the maximum value for the one-way slab was achieved by sample SM7, as shown in

Figure 10.

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 illustrate the crack patterns for one-way and two-way slabs in Group 2, where the PF content varied from 0.1% to 0.9% and the SF content remained constant at 0.8%. During testing, the crack patterns of all two-way slab specimens were closely examined. The results revealed that the inclusion of polypropylene fibers significantly affected the deflection behavior of the specimens, resulting in a marked increase in deflection compared to the control specimen. This suggests that the polypropylene fibers played a critical role in improving the concrete’s flexibility and crack resistance, thereby enhancing its ability to absorb energy and resist failure underloading. The crack patterns further demonstrated how the polypropylene fibers contributed to a more evenly distributed stress field, mitigating the formation of large, damaging cracks.

Experimental results show that incorporating polypropylene fibers enhances the elastic behavior of concrete, though the cohesive forces between particles remain unchanged. Excessive deflection can exceed the concrete’s tensile capacity, causing fissure planes and spalling. Adding steel fibers delays failure, extends the deformation phase, and improves load distribution across fissure planes. Optimal blending of both fibers significantly enhances load-carrying capacity and deflection. Cracks in two-way slabs predominantly developed diagonally on the tension side, increasing gradually under load. Specimen SM1, without fibers, exhibited single diagonal cracking at lower loads, while other specimens showed cracks in both diagonal directions, except for SM9, where cracks aligned with slab edges, as depicted in

Figure 11.

For the two-way slabs, the load-deflection curves for the peak values of specimens SM4 and SM9 were plotted to compare their behavior with that of the control specimen SM1, with load on the vertical axis and deflection on the horizontal axis. The comparison revealed that SM4 and SM9 exhibited significantly higher initial and ultimate load-carrying capacities than the control specimen SM1. At the initial stages, the load-deflection curves for all three specimens closely coincided, indicating similar behavior under lower loads. However, beyond the elastic phase, the load-carrying capacities of SM4 and SM9 increased substantially, which can be attributed to fiber reinforcement enhancing the slabs’ post-elastic properties. This capacity increase highlighted the fibers’ effectiveness in improving the slabs’ performance beyond the elastic region. Furthermore, the deflection at ultimate failure for the control specimen SM1 was lower than that of SM4 and SM9, as shown in

Figure 12, demonstrating the superior flexibility and energy absorption of the fiber-reinforced specimens.

The higher baseline content of steel fibers (0.8% vs. 0.7%) provides substantial post-cracking strength and stiffness from the outset. In this context, the role of polypropylene fibers becomes more specialized. An excessive amount of PF (e.g., 0.9%) can disrupt the concrete matrix’s packing density, creating weak points that may counteract the benefits of micro-crack control. The optimal 0.5% PF content appears to provide the ideal amount of micro-reinforcement to enhance the matrix’s integrity during the initial elastic and micro-cracking phases without compromising the efficiency of the steel fiber network. The synergy here is matrix enhancement: the PF refines the crack system, enabling the stronger steel fiber network to operate more effectively and achieving the highest observed load capacity.

Furthermore, the results consistently demonstrate the structural advantage of two-way action over one-way action, as seen in the steeper initial slopes (higher stiffness) and higher ultimate loads of the two-way slabs (black curves in

Figure 10). The fiber reinforcement mechanism is more efficiently utilized in two-way slabs because the multi-directional load path allows a greater volume of fibers to be engaged in bridging cracks. In contrast, in one-way slabs, the failure is localized to a single critical crack.

The crack patterns for Group 2 (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12) further confirm the role of fibers. The inclusion of polypropylene fibers again led to a marked increase in deflection capacity compared to the control. The cracks in the hybrid fiber specimens were more distributed, illustrating how the fibers create a more ductile failure mode by controlling crack width and propagation through the combined mechanisms of micro-crack arrest (PF) and macro-crack bridging (SF).

4.3. Group 3: SF (0.9%) with PF % (0.1%, 0.3%, 0.5%, 0.7%, and 0.9%)

Figure 13 illustrates the load-deflection behavior for six additional structural elements labeled SM1, SM12, SM13, SM14, SM15, and SM16 under two-way and one-way loading conditions. The vertical axis represents the applied load in kilonewtons (kN), while the horizontal axis represents deflection in millimeters (mm). In all six graphs, the black curves correspond to two-way loading, while the blue curves represent one-way loading. The results demonstrate that two-way loading outperforms one-way loading across all specimens. The two-way loaded elements exhibit higher load-carrying capacity and stiffer responses, as evidenced by a higher peak load and reduced deflection at similar load levels. For instance, SM12 and SM14 exhibit loads approaching 200 kN under two-way loading, whereas their one-way counterparts plateau at significantly lower values. Similarly, for SM15 and SM16, two-way loading results in more gradual deflection with increasing load, whereas one-way loading is characterized by lower stiffness and earlier saturation of load capacity. These trends emphasize the efficiency of two-way load distribution in enhancing the tested elements’ structural performance by increasing their strength and reducing deformation.

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 illustrate the crack patterns for one-way and two-way slabs in Group 2, where the polypropylene fiber (PF) content varied from 0.1% to 0.9%, while the steel fiber (SF) content remained constant at 0.9%. During testing, the crack patterns of all two-way slab specimens were closely examined. The results showed that the inclusion of polypropylene fibers significantly increased the specimens’ deflection compared to the control specimen. This increase in deflection indicates that the polypropylene fibers played a crucial role in improving the concrete’s flexibility and crack resistance. The fibers contributed to a more even distribution of stresses, mitigating the development of large, localized cracks and improving the slabs’ overall performance underload. The crack patterns in the figures further demonstrated the positive impact of fiber reinforcement on the concrete’s post-cracking behavior.

It was observed that cracking was initiated at the loading point (center) in all specimens. In specimen SM12, which exhibited the highest load-carrying capacity and corresponding deflection, the cracks at the bottom formed a triangular shape, which proved most effective in enhancing both the load-carrying capacity and the vertical mid-span deflection. In contrast, specimen SM13 failed without significant concrete crushing and exhibited only minor cracks, indicating a strong bond between the concrete. This was attributed to the use of 0.9% steel fibers (SF) and 0.3% polypropylene fibers (PF), which improved the specimen’s performance, as illustrated in

Figure 14.

Specimen SM12 absorbed the maximum energy among the two-way slabs with a fiber ratio of 0.9% steel fibers and 0.1% polypropylene fibers (S0.9–0.1). It was observed that both the initial and ultimate load-carrying capacities of SM12 were significantly higher than those of the control specimen SM1. At early loading stages, the load-deflection curves for SM12 and SM1 nearly overlapped, indicating similar behavior at lower loads. However, as loading progressed into the post-elastic stage, the load-carrying capacity of the two slabs diverged sharply, with SM12 showing a marked increase. This shift in behavior was attributed to the enhancement of the post-elastic properties of fiber-reinforced concrete, which improved its ability to resist cracking and sustain higher loads. The change in the load-deflection behavior, particularly during the post-elastic phase, is illustrated in

Figure 15, emphasizing the contribution of fiber reinforcement to the slab’s performance beyond initial loading.

This result can be explained by a fiber synergy dominated by the macro-crack bridging mechanism. At a high dosage of 0.9%, the steel fibers create a dense, high-stiffness network that is extremely effective at carrying tensile stresses across widening cracks. In this scenario, the primary role of the polypropylene fibers is not to add significant post-cracking strength, but to provide essential micro-crack control during the initial loading phases. The 0.1% PF content is sufficient to inhibit the initiation and coalescence of micro-cracks, thereby preserving the integrity of the matrix and allowing the powerful steel fiber network to engage more efficiently and at a higher stress level. The addition of higher PF volumes (e.g., 0.3% to 0.9%) did not yield further improvements and, in some cases, led to a slight decrease in performance. This suggests that beyond a certain threshold, an excess of flexible polypropylene fibers may slightly disrupt the packing density and homogeneity of the matrix, subtly interfering with the optimal performance of the dominant steel fiber bridging system.

The crack patterns, illustrated in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15, provide visual evidence of this mechanism. Specimen SM12, the top performer, developed a well-defined triangular crack pattern at the slab bottom. This pattern is indicative of efficient yield-line formation and excellent in-plane stress redistribution, facilitated by the fibers’ ability to maintain composite action after cracking. The fibers, particularly the high content of steel fibers, ensured that cracks remained tightly controlled, allowing the slab to develop its full plastic capacity. In contrast, specimen SM13 (0.9% SF, 0.3% PF) failed with only minor cracking and minimal concrete crushing. This behavior suggests an extremely strong fiber-matrix bond and a high degree of crack suppression, but it may also indicate a slightly more brittle failure mode where the energy absorption through fiber pull-out was less pronounced than in SM12.

The load-deflection curve of SM12 offers further mechanistic insight. In the initial stages, its behavior nearly overlapped with the control specimen (SM1), confirming that fibers have a minimal effect on the initial elastic modulus of concrete. The critical divergence occurred in the post-cracking phase. As micro-cracks developed, the low dosage of PF helped control them, while the high dosage of SF provided immense pull-out resistance. This combination resulted in a significant enhancement in post-cracking stiffness, a much higher ultimate load, and substantial energy absorption (as quantified by the area under the curve). This “pseudo-ductile” response is the hallmark of effective fiber reinforcement, transforming a inherently brittle material into one capable of sustaining load with large, controlled deformations.

4.4. Group 4: SF (0.9%) with PF % (0.1%, 0.3%, 0.5%, 0.7%, and 0.9%)

Figure 16 compares the load-deflection responses of six structural elements labeled SM1, SM17, SM18, SM19, SM20, and SM21 under two-way and one-way loading conditions. The vertical axis represents the applied load in kilonewtons (kN), while the horizontal axis shows deflection in millimeters (mm). The black curves represent two-way loading in all six cases, and the blue curves correspond to one-way loading. Across all specimens, the two-way loading condition consistently demonstrates superior performance, achieving higher load-carrying capacity and lower deflection than the one-way loading condition. For instance, in SM17 and SM18, the two-way responses reach approximately 200 kN, whereas the one-way curves level off at much lower loads. Similarly, for SM19, SM20, and SM21, the two-way loaded elements display steeper slopes and sustain higher loads before significant deflection, whereas the one-way curves exhibit earlier saturation and greater deformation. These results highlight the structural advantage of two-way loading, as it efficiently distributes loads, leading to improved stiffness and a higher strength capacity compared to one-way loading.

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 illustrate the crack patterns for one-way and two-way slabs in Group 2, where the polypropylene fiber (PF) content varied from 0.1% to 0.9%, with the steel fiber (SF) content fixed at 1.0%. The crack patterns of all two-way slab specimens were carefully examined during testing. The results revealed that adding polypropylene fibers significantly increased the deflection of the specimens compared to the control specimen. This increase in deflection indicates that the polypropylene fibers enhanced the concrete’s flexibility and crack resistance. The fibers helped distribute stresses more uniformly, reducing the formation of large, localized cracks and improving the slabs’ overall performance under applied loads. The crack patterns shown in the figures further highlight the positive effects of fiber reinforcement on the durability and structural integrity of the slabs.

The deflection at ultimate failure for the control specimen SM1 was significantly lower than that of SM12, indicating superior flexibility and energy absorption in the latter. In contrast, specimens SM19 and SM21 failed suddenly at their ultimate load, with a narrow gap between the elastic limit and ultimate failure. While these slabs showed a significant increase in load during the initial stages, they reached their ultimate load before the control specimen SM1. This behavior was attributed to the high content of steel and polypropylene fibers in these slabs, which enhanced their load-carrying capacity. However, issues such as fiber flocculation, balling action, improper mixing, and subsequent bleeding of the concrete mix likely contributed to the rapid failure observed in SM19 and SM21. These factors compromised the uniform distribution of fibers within the matrix, potentially weakening the slabs’ performance. The crack patterns and load-deflection behaviors of these slabs, as illustrated in

Figure 17 and

Figure 18, highlight the challenges and benefits of high fiber content in concrete.

The behavior of specimens SM19 and SM21 provides critical insights. These slabs, with high fiber volumes, exhibited sudden brittle failure due to a compromised fiber-matrix system. Key factors include

High fiber volumes (1.0% SF with PF) lead to entangled fibers that create uneven distribution, resulting in weak zones that initiate premature failure.

Disruption in aggregate packing increases voids and bleeding, leaving fibers embedded in a weak matrix, thus reducing bond strength and ductility.

Reduced workability from fiber congestion can lead to inadequate compaction, worsening internal voids, and stress concentrations.

In contrast, specimen SM12 from Group 3 (0.9% SF, 0.1% PF) performed well, achieving a balance that maximized energy absorption and ductility with a well-compacted matrix. The findings highlight a synergistic mechanism for crack control:

Polypropylene Fibers (Micro-Scale): Bridge micro-cracks and delay coalescence, enhancing first-crack strength.

Steel Fibers (Macro-Scale): Bridge macro-cracks, providing high pull-out resistance and improving post-cracking strength.

The optimal fiber blend varies across slab types (e.g., 0.7% SF, 0.9% PF for one-way slabs and 0.9% SF, 0.1% PF for two-way slabs), reflecting different stress states and crack patterns.

4.5. Summary of Crack Patterns

The crack patterns of all one-way slab specimens were analyzed and presented

Figure 8,

Figure 11,

Figure 14 and

Figure 17. It was observed that specimens S-M1, S-M3, S-M4, S-M8, S-M12, S-M18, S-M19, and S-M20 failed primarily in flexure, showing typical bending cracks as the slabs reached their load-bearing limits. On the other hand, specimens S-M5, S-M6, S-M7, S-M9, SM13, S-M14, S-M15, S-M16, and S-M21 exhibited shear failure, characterized by diagonal cracks originating from the loaded corners and propagating towards the support areas. Additionally, specimens S-M2, S-M10, S-M11, and SM17 displayed a combination of shear failure and various flexural cracks, indicating that both bending and shearing stresses contributed to the failure mechanisms in these specimens. These observations highlight the different failure modes that occurred depending on fiber content, mix design, and slab structural configuration. The cracks in the control specimen SM1 were more significant than those in the fiber-reinforced concrete (HFRC) specimens. This difference was attributed to the absence of fibers in the control specimen, which typically act as bridges between concrete particles, thereby improving crack resistance. Notably, specimen SM6 absorbed the maximum energy among all the specimens.

In most slab specimens, cracking initiated at the slab’s yield line under center-point loading during the flexural test, with cracks progressively expanding until the specimen failed. Each specimen exhibited two distinct peak behaviors: the first peak occurred from the onset of loading up to the elastic limit, representing the first crack load, while the second peak corresponded to the ultimate load-carrying capacity of the specimen, characterized by the rupture of the concrete material on the bottom side of the slabs.

Similarly,

Figure 9,

Figure 12,

Figure 15, and

Figure 18 illustrate the crack pattern for the two-way slab. The cracking behavior of S-M17 was like that of S-M13. The larger cracks were produced in specimens S-M18 and S-M21, showing a weaker bond between the concrete materials. In specimen S-M20, the minor cracks on the bottom side of the slab were produced at the ultimate loading stage. Thus, it is concluded that hybrid fibers with a ratio of 0.9% steel and 0.1% polypropylene fibers are the most effective in terms of loads and vertical mid-span deflections under flexural testing of two-way slabs.

The reviewer highlights the importance of discussing unexpected results, such as the performance of specimens SM19 and SM21 (from Group 4 with 1.0% SF), which displayed sudden, brittle failure instead of improved performance typically expected with higher fiber content. The following factors contributed to this outcome:

Fiber Congestion and Balling: The high total fiber volume likely caused fiber flocculation, creating weak zones in the matrix.

Workability and Compaction Issues: Reduced workability may have led to inadequate compaction during casting, increasing porosity and internal defects.

Matrix Imperfections: The dense fiber network could have disrupted aggregate packing, compromising the fiber-matrix bond essential for pull-out resistance.

This discussion addresses the upper limits of fiber addition and highlights the significance of workability and uniform dispersion. We recognize the need for statistical reliability and have re-analyzed our experimental data. All numerical tables will now include mean values and standard deviations (±SD) for each mix proportion, with captions indicating that error bars reflect standard deviation. The “Methods” section will clarify the number of specimens tested per mix (n-value) for better statistical context. We believe these revisions will effectively address the reviewer’s concerns, enhance our analysis, and bolster the reliability of our findings. We appreciate the reviewer’s guidance, which has significantly improved our work.