Discrete Element Simulation Study of Soil–Rock Mixture Under High-Frequency Vibration Loading

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A discrete element model for soil–rock mixtures suitable for high-frequency vibratory compaction was established, addressing the limitation of laboratory tests in simulating high-frequency loading.

- (2)

- A multi-scale particle modeling approach was proposed, combining realistically shaped aggregates, lumpy soil, and spherical fine particles to more accurately replicate field gradations.

- (3)

- Systematically revealed the influence mechanisms of stone content and vibration modes on porosity, cumulative strain, and structural evolution, providing theoretical foundations for optimizing IC process parameters.

2. An Introduction to the Discrete Element Method for Particle Flow

2.1. An Introduction to the Theory of Numerical Simulation of Particle Flows

2.1.1. Principles of Computation

- (1)

- Particles are rigid bodies without deformation, consistent with the assumption in soil mechanics that solid-phase particles are incompressible and non-deformable.

- (2)

- The contact area between particles is very small.

- (3)

- Particle-to-particle contact is flexible, allowing particles to overlap, with the overlap amount being significantly smaller than the particle size.

2.1.2. Particle Flow Program Model

2.2. Contact Constitutive Model for Particle Flow Programs

2.3. Principles and Implementation of Three-Axis Servo Mechanisms

3. Profile of Dynamic Triaxial Test

3.1. Test Apparatus

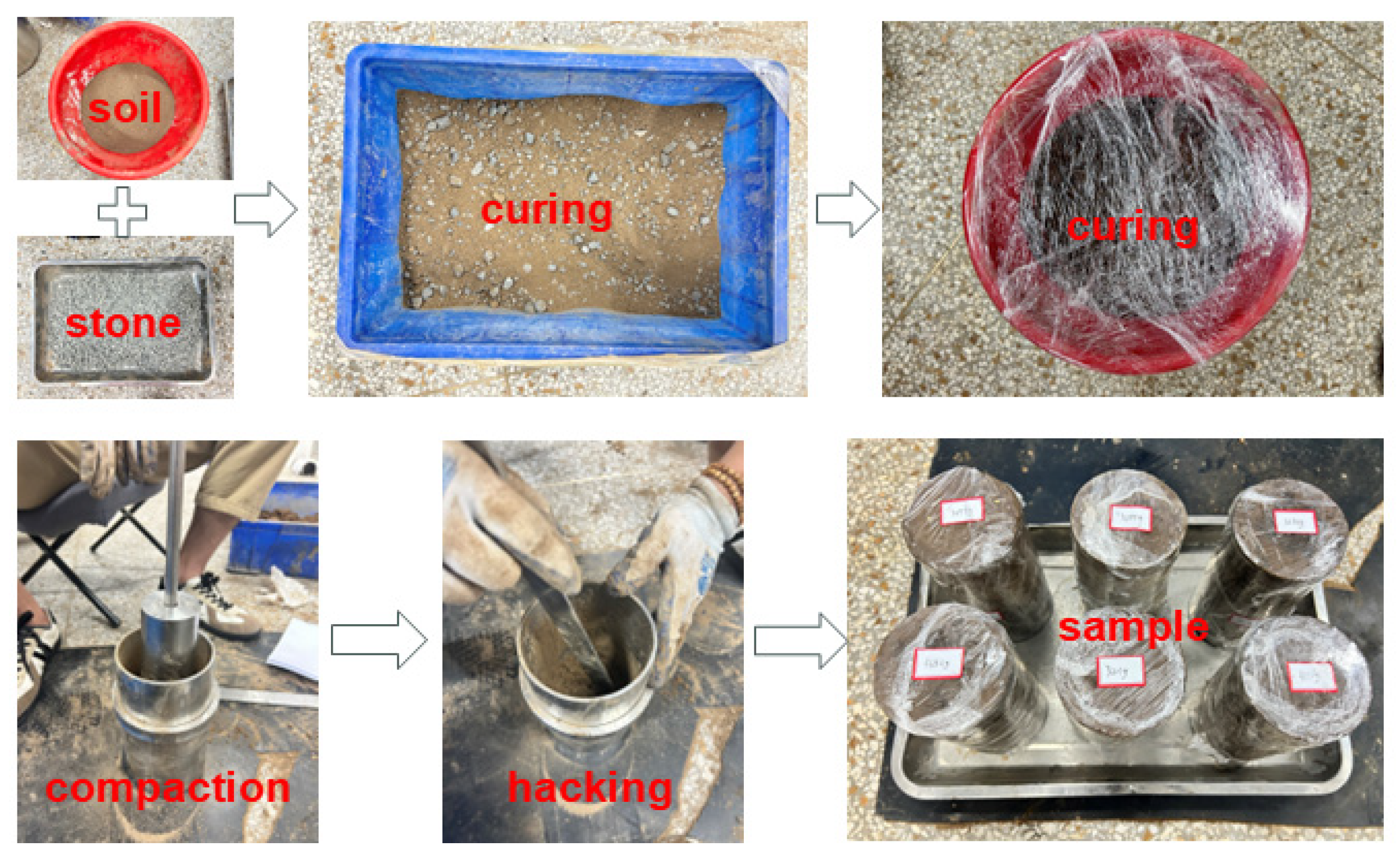

3.2. Soil Sample Properties and Specimen Preparation

3.3. Test Loading Scheme

4. Dynamic Triaxial Discrete Element Numerical Simulation of Soil–Rock Mixture

4.1. The Composition of the Numerical Model

4.1.1. Coordinate System and Unit System

4.1.2. Calculation Area and Wall Boundary

4.1.3. Construction of Particle System

4.1.4. Modeling

4.2. Contact Model Setting

4.3. Numerical Experimentation Scheme

5. Mesoscopic Parameter Calibration

6. Typical Law of the Dynamic Triaxial Test of Soil–Rock Mixture

6.1. Porosity

6.2. Vertical Cumulative Strain and Particle Displacement

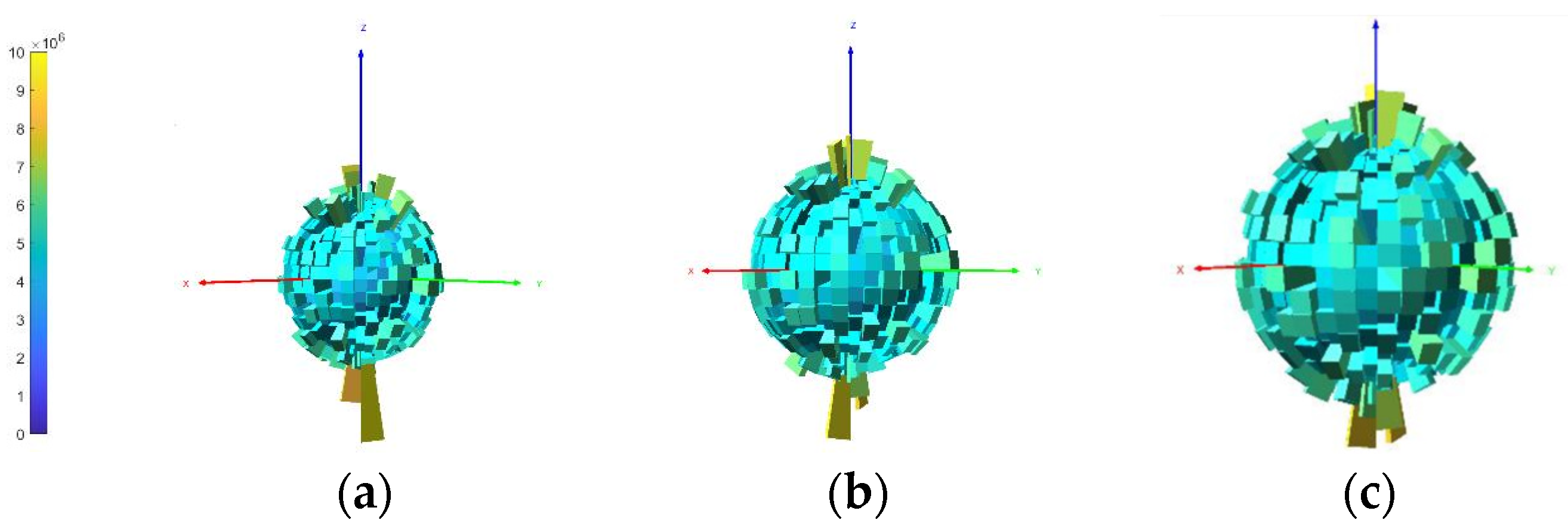

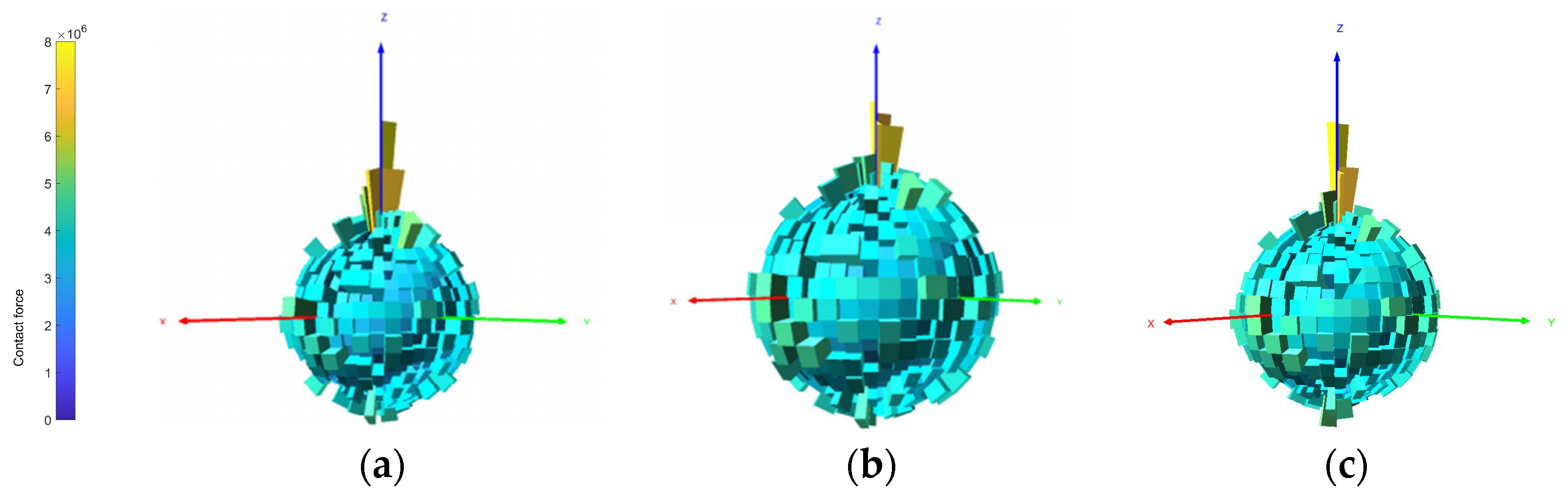

6.3. Fabric Evolution

6.4. Implications for Intelligent Compaction

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- A validated high-frequency DEM model: The established discrete element model successfully overcomes the low-frequency limitations of laboratory tests, enabling the simulation of field-like vibratory compaction. This addresses the first innovation point and reveals that the evolution of specimen porosity is significantly more pronounced under strong vibration than under weak vibration. Furthermore, the relationship between porosity reduction and rock content is nonlinear, with the most significant compaction occurring at a rock content of 50%.

- (2)

- Macro-response explained by multi-scale modeling: The multi-scale modeling strategy, which combines true-shaped aggregates, clumpy soil, and spherical fine particles, provides a credible micromechanical basis for macroscopic observations. It elucidates that the macroscopic cumulative strain increases with loading cycles at a decelerating rate, a direct result of particle rearrangement and void filling. Strong vibration generates greater cumulative strain due to longer inter-particle contact duration. The nonlinear impact of rock content on strain—peaking at 50%—is attributed to the formation of an optimal skeleton–soil structure at this content.

- (3)

- Influence mechanisms of vibration mode and rock content: The systematic analysis reveals the underlying mechanisms through which vibration modes and rock content influence compaction. Fabric tensor analysis demonstrates that the internal force chain network evolves from an initial isotropic state to a vertically concentrated distribution to resist external stress. This fabric anisotropy is more developed under strong vibration, forming a denser and more stable structure. The rock content dictates the efficiency of this fabric evolution: 50% content facilitates a uniform and efficient force distribution; 30% content leads to a more dispersed pattern in a soil-dominated matrix; and 70% content results in a rigid skeleton with weaker inter-particle contacts.

- (4)

- The meso-scale mechanisms quantified in this study—the systematic reduction in porosity and the reorientation of contact forces—provide a physical interpretation for the macro-scale indicators used in IC. The documented densification and force chain formation are the fundamental reasons for the increase in soil stiffness, which is the key parameter that IC systems aim to evaluate indirectly. Thus, this work links the evolution of the internal soil structure to the engineering practice of compaction quality control.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, Y.; Yi, T.; Li, X.; Rong, X.; Gao, Y.; Leng, Z.; Dong, L.; Wang, D. Advances in Intellectualization of Transportation Infrastructures. Engineering 2023, 24, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Cai, B.; Chai, L. Research on Over-the-Horizon Perception Distance Division of Optical Fiber Communication Based on Intelligent Roadways. Sensors 2024, 24, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullya, J.P.; Sgambatti, J.; Templetonb, J.S.; McClelland, F.; Perez, F.; Laya, E. Geotechnical characterization of Rio Caribe soils. In Proceedings of the 27th Offshore Technology Conference, OTC 1995, Houston, TX, USA, 1–4 May 1995; pp. 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Niu, D.; Niu, Y.; Hu, B.; Chen, X.; Liu, P. Effect of compaction parameter on aggregate particle migration and compaction mechanism using 2D image analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 382, 131298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Yu, J.; Liu, M. Porosity- and reliability-based evaluation of concrete-face rock dam compaction quality. Autom. Constr. 2017, 81, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Huangfu, Z.; Li, Q.; An, Z. Compaction quality assessment of rockfill materials using roller-integrated acoustic wave detection technique. Autom. Constr. 2019, 97, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, L.B.; Sysyn, M.; Gerber, U.; Fischer, S. Analysis of the Stressed State of Sand-Soil Using Ultrasound. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Li, W. Effect of initial fabric from sample preparation on the mechanical behaviour of a carbonate sand from the South China Sea. Eng. Geol. 2023, 326, 107311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Zuo, S.; Li, J.; Bi, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, M. Intelligent Compaction System for Soil-Rock Mixture Subgrades: Real-Time Moisture-CMV Fusion Control and Embedded Edge Computing. Sensors 2025, 25, 5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Liu, S.; Gao, X.; Ren, F.; Liu, P.; Wu, Q. Real-Time Evaluation of Compaction Quality by Using Artificial Neural Networks. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 2020, 6617742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, F.; Ma, T.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y. Intelligent Compaction: An Improved Quality Monitoring and Control of Asphalt Pavement Construction Technology. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 14875–14882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Lei, H.; Kang, X. Examination of interface roughness and particle morphology on granular soil-structure shearing behavior using DEM and 3D printing. Eng. Struct. 2023, 290, 116365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Bai, S.; Xue, G.; Yang, J.; Cai, Y.; Hu, W.; Jia, X.; Huang, B. Assessment of compaction quality of multi-layer pavement structure based on intelligent compaction technology. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 161, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, C.; Qiao, L.; Wu, H.; Liu, R.; Guo, W. Compaction Quality Control and Assurance of Silt Subgrade Using Roller-Integrated Compaction Monitoring Technology. J. Test. Eval. 2024, 52, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Dong, F.; Ma, S.; Shen, J.; Liu, Z. Vibratory compaction characteristics of the subgrade under cyclical loading based on finite element simulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 419, 135378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Lin, M.; Li, S. Real-Time Quality Monitoring and Control of Highway Compaction. Autom. Constr. 2016, 62, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Cui, X.; Du, Y.; Jin, Q.; Hao, J.; Cao, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Development and verification of subgrade service performance test system considering the principal stress rotation. Transp. Geotech. 2025, 50, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Khabbaz, H.; Fatahi, B.; Wu, D. Real-time determination of sandy soil stiffness during vibratory compaction incorporating machine learning method for intelligent compaction. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 14, 1609–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Dan, H.; Shan, H.; Li, S. Investigation of Particle Rotation Characteristics and Compaction Quality Control of Asphalt Pavement Using the Discrete Element Method. Materials 2024, 17, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potyondy, D.O. The bonded-particle model as a tool for rock mechanics research and application: Current trends and future directions. Geosystem Engineering 2015, 18, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; An, Q.; Suo, S.; Wang, W.; Jia, X. An Analytical Model for the Normal Contact Stiffness of Mechanical Joint Surfaces Based on Parabolic Cylindrical Asperities. Materials 2023, 16, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Krengel, D.; Nishiura, D.; Furuichi, M.; Matuttis, H.G. A force-displacement relation based on the JKR theory for DEM simulations of adhesive particles. Powder Technol. 2023, 427, 118742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JTG 3430-2020; Test Methods of Soils for Highway Engineering. Ministry of Transport: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Hua, T.; Yang, Z.; Yang, X.; Huang, H.; Yao, Q.; Wu, G.; Li, H. Assessment of geomaterial compaction using the pressure-wave fundamental frequency. Transp. Geotech. 2020, 22, 100318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Lei, H.; Kang, X. Effects of particle morphology on the shear response of granular soils by discrete element method and 3D printing technology. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2022, 46, 2191–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defaveri, L.; Barkai, E.; Kessler, D.A. Brownian particles in periodic potentials: Coarse-graining versus fine structure. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, G. Influence of Stone Shape Factor on the Pull-Out Resistance of Geogrid in the Soil-Rock Mixture. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 4975059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, Q. Evaluation of rock size on the mechanical behavior and deformation performance of soil-rock mixture: A meso-scale numerical and theoretical study. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, W.; Tang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, C. A thermodynamically consistent constitutive model for soil-rock mixtures: A focus on initial fine content and particle crushing. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 169, 106233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimun, N.; Mohamad, H. Investigation of Particle Gradation Effect on Soil-Rock Mixture Using Direct Shear Test. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2024, 16, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Ma, G. Physical-based subgrade compaction assessment combining vibratory response and real-time soil deformation. Transp. Geotech. 2026, 56, 101749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, Y.; Jia, F.; Wang, X. Intelligent compaction quality evaluation based on multi-domain analysis and artificial neural network. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 341, 127583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Luan, J.; Gao, X.; Wang, J.P.; Dadda, A. A micro-investigation on water bridge effects for unsaturated granular materials with constant water content by discrete element method. Particuology 2023, 83, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Gong, J.; Jia, M.; Nie, Z.; Hu, W.; Li, B. Effect of the intermediate principal stress on the mechanical behaviour of breakable granular materials using realistic particle models. Acta Geotech. 2022, 17, 4887–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, M.; Konishi, J. Microscopic Deformation Mechanism of Granular Material in Simple Shear. Soils Found. 1974, 14, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, M.; Nakayama, H. Yield function for soil with anisotropic fabric. J. Eng. Mech. 1989, 115, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lade, P.V. Failure criterion for cross-anisotropic soils. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2008, 134, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satake, M. Fabric tensor in granular materials. In Proceedings of the IUTAM-Conference on Deformation and Failure of Granular Materials, Delft, The Netherlands, 31 August–3 September 1982; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Symbols | Size | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| vibration wheel mass | md | 6500 | kg |

| frame quality | mf | 10,500 | kg |

| excitation frequency | f | 29/35 | Hz |

| nominal amplitude | H | 1.8/0.9 | mm |

| vibratory force | P | 410/300 | kN |

| vibration wheel width | L | 2.14 | M |

| vibration wheel radius | R | 0.775 | m |

| driving speed | v | 2.8/5.6/9.1 | m/s2 |

| Parameter | Strong Vibration | Weak Vibration |

|---|---|---|

| vibratory force (kN) | 410 | 300 |

| frequency (Hz) | 29 | 35 |

| principal stress (kPa) | 781 | 615 |

| confining pressure (kPa) | 260 | 205 |

| Frequency (Hz) | Confining Pressure (kPa) | Load (kN) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 200 | 600 |

| 5 | ||

| 10 |

| Physical Values | Symbol | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| mass | M | kg |

| length | L | m |

| time | T | s |

| density | ρ | kg/m3 |

| force | F | N |

| stress | σ | kPa |

| stiffness | kn, ks | N/m |

| Rock Content R/% | 30 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original porosity n0 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.20 |

| Broken-stone particles occupied by volume particles | 0.195 | 0.219 | 0.234 | 0.240 |

| Soil grain occupied by volume particles | 0.455 | 0.511 | 0.546 | 0.560 |

| Corresponding porosity of broken-stone particles | 0.805 | 0.781 | 0.766 | 0.760 |

| Corresponding porosity of soil grain particles | 0.545 | 0.489 | 0.454 | 0.440 |

| Compaction degree C/% | 87 | 91 | 93 | 94 |

| Rock Content R/% | 30 | 50 | 70 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original porosity n0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Broken-stone particles occupied by volume particles | 0.25 | 0.375 | 0.525 |

| Soil grain occupied by volume particles | 0.5 | 0.375 | 0.225 |

| Corresponding porosity of broken-stone particles | 0.75 | 0.625 | 0.475 |

| Corresponding porosity of soil grain particles | 0.5 | 0.625 | 0.775 |

| Rock Content R/% | 30 |

|---|---|

| Original porosity n0 | 0.35 |

| Broken-stone particles occupied by volume particles | 0.195 |

| Soil grain occupied by volume particles | 0.455 |

| Corresponding porosity of broken-stone particles | 0.805 |

| Corresponding porosity of soil grain particles | 0.545 |

| Contact Type | Effective Modulus E* (MPa) | Stiffness Ratio k* | Stiffness Ratio μ |

|---|---|---|---|

| soil–soil | 6 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| soil–field stone | 10 | 3.0 | 0.55 |

| field stone–field stone | 20 | 3.5 | 0.4 |

| soil–wall | 6 | 0.5 | 0.45 |

| field stone–wall | 10 | 3.0 | 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, K.; Cai, Y.; Hu, Y.; Hu, J.; Yan, S.; Shu, R.; Cui, X.; Zhang, X. Discrete Element Simulation Study of Soil–Rock Mixture Under High-Frequency Vibration Loading. Buildings 2025, 15, 4426. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244426

Cheng K, Cai Y, Hu Y, Hu J, Yan S, Shu R, Cui X, Zhang X. Discrete Element Simulation Study of Soil–Rock Mixture Under High-Frequency Vibration Loading. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4426. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244426

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Kai, Yu Cai, Yun Hu, Junlin Hu, Shirong Yan, Rong Shu, Xinzhaung Cui, and Xiaoning Zhang. 2025. "Discrete Element Simulation Study of Soil–Rock Mixture Under High-Frequency Vibration Loading" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4426. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244426

APA StyleCheng, K., Cai, Y., Hu, Y., Hu, J., Yan, S., Shu, R., Cui, X., & Zhang, X. (2025). Discrete Element Simulation Study of Soil–Rock Mixture Under High-Frequency Vibration Loading. Buildings, 15(24), 4426. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244426