Flexural Performance of Prefabricated Steel-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Wall Panels: Finite Element Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment on Steel-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete

2.1. Experimental Program

2.1.1. Materials

2.1.2. Mix Design

2.2. Experimental Results

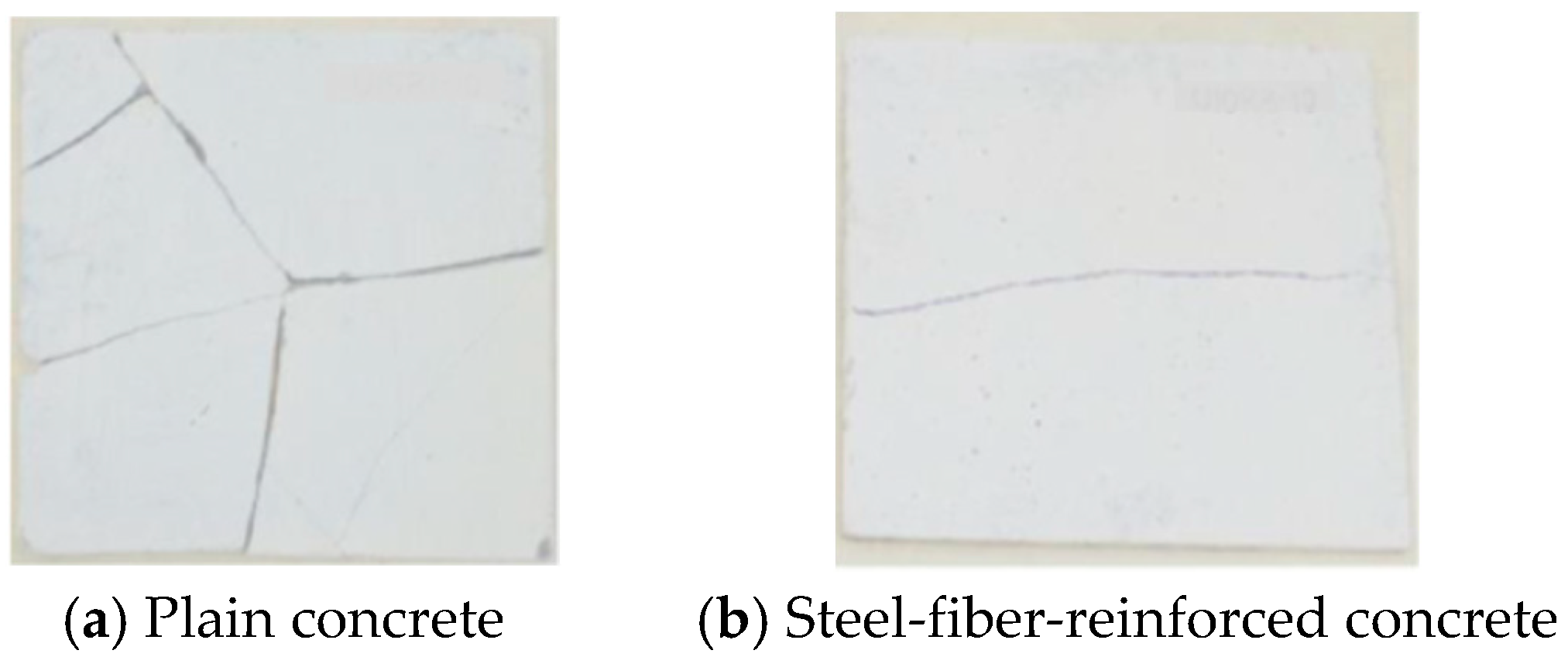

2.2.1. Failure Modes

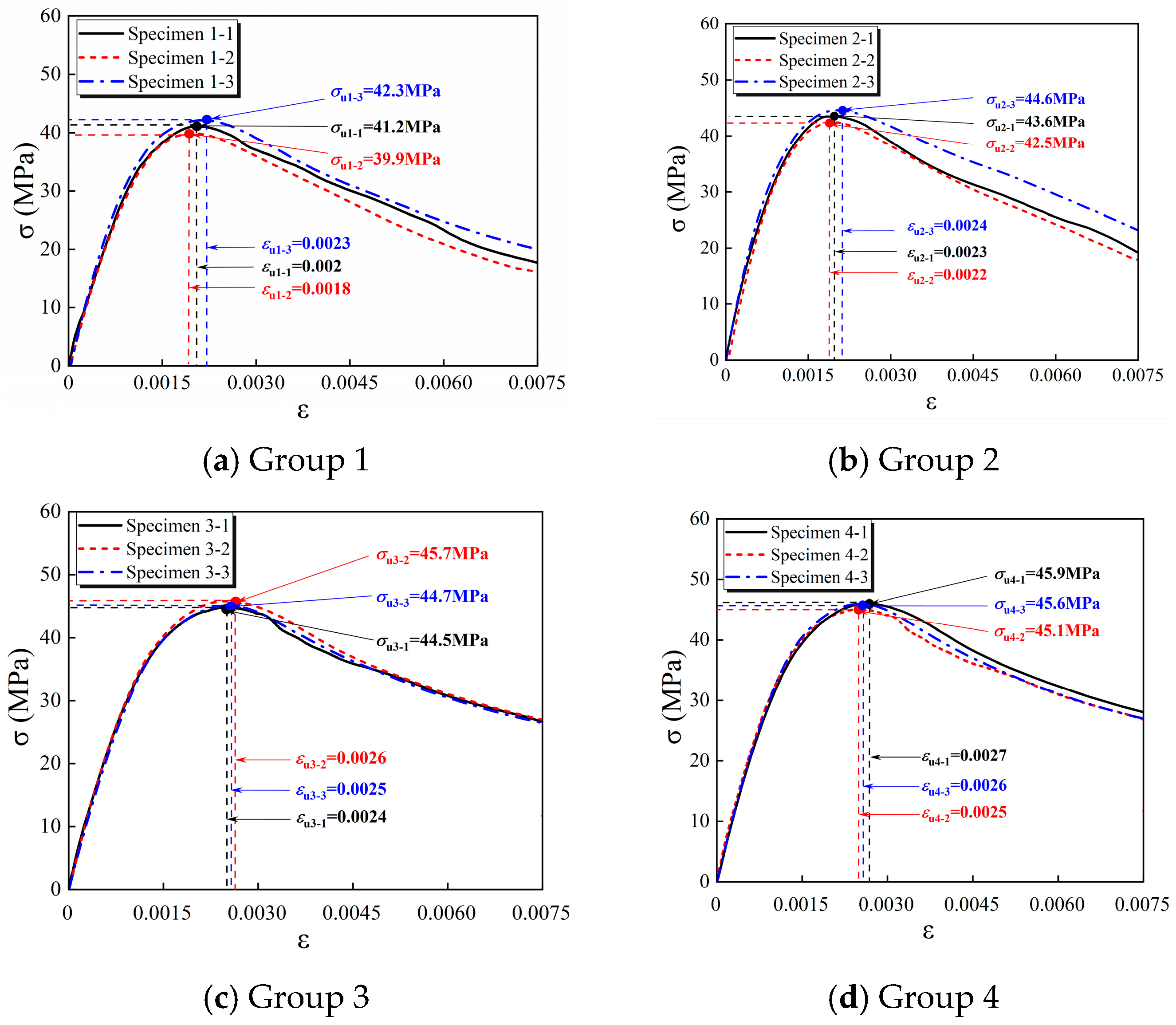

2.2.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

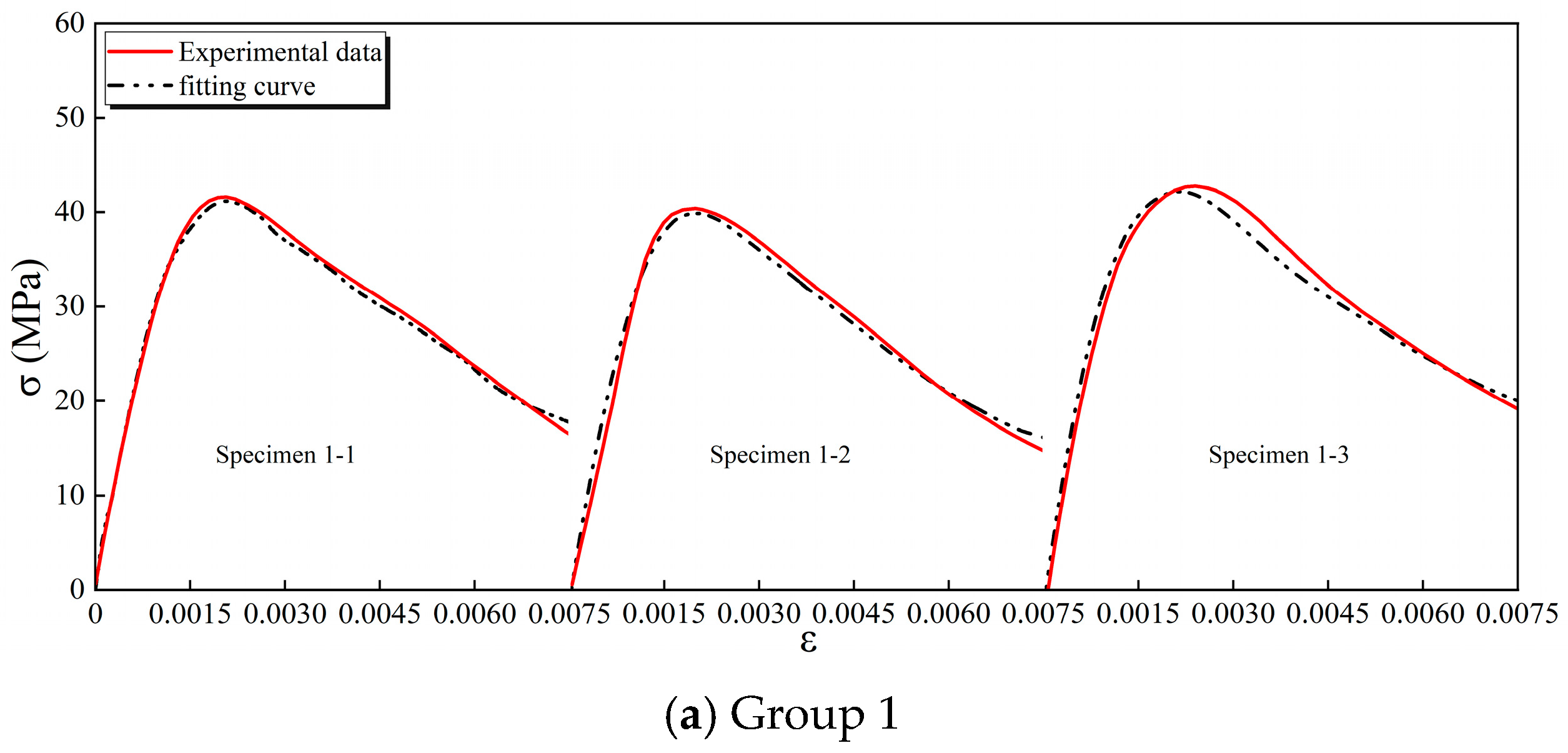

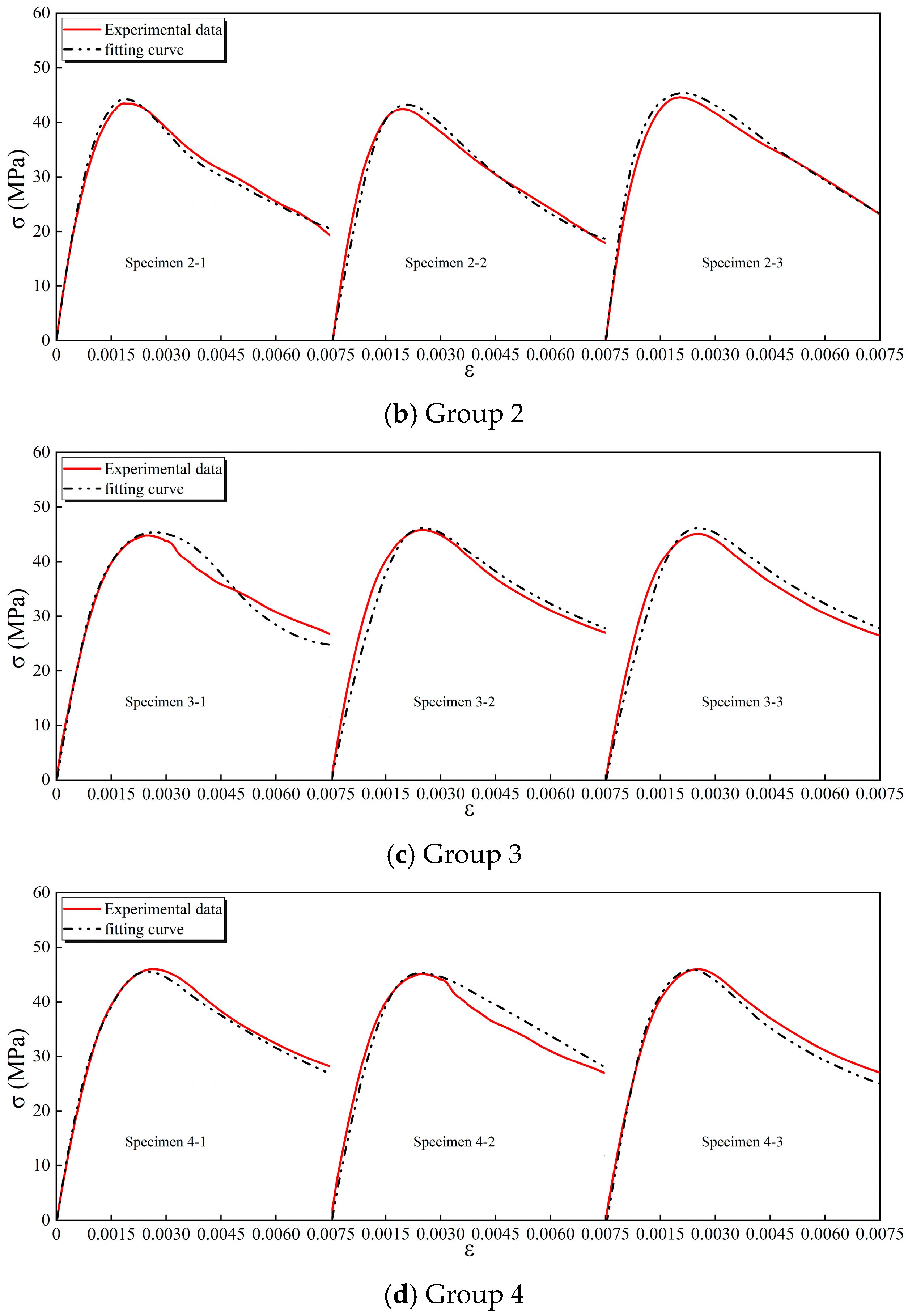

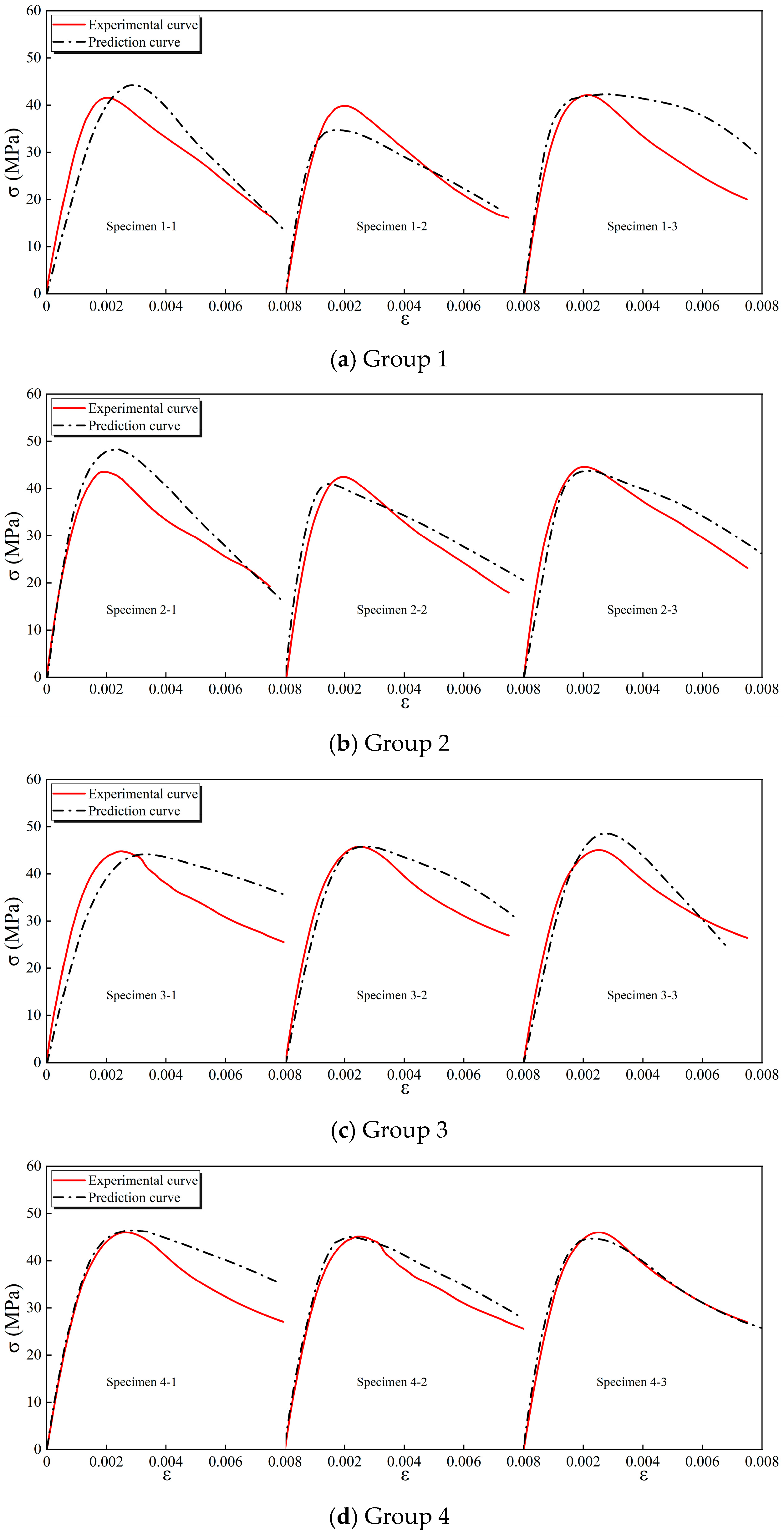

2.2.3. Fitting of Axial Compression Stress–Strain Curves

3. Finite Element Analysis

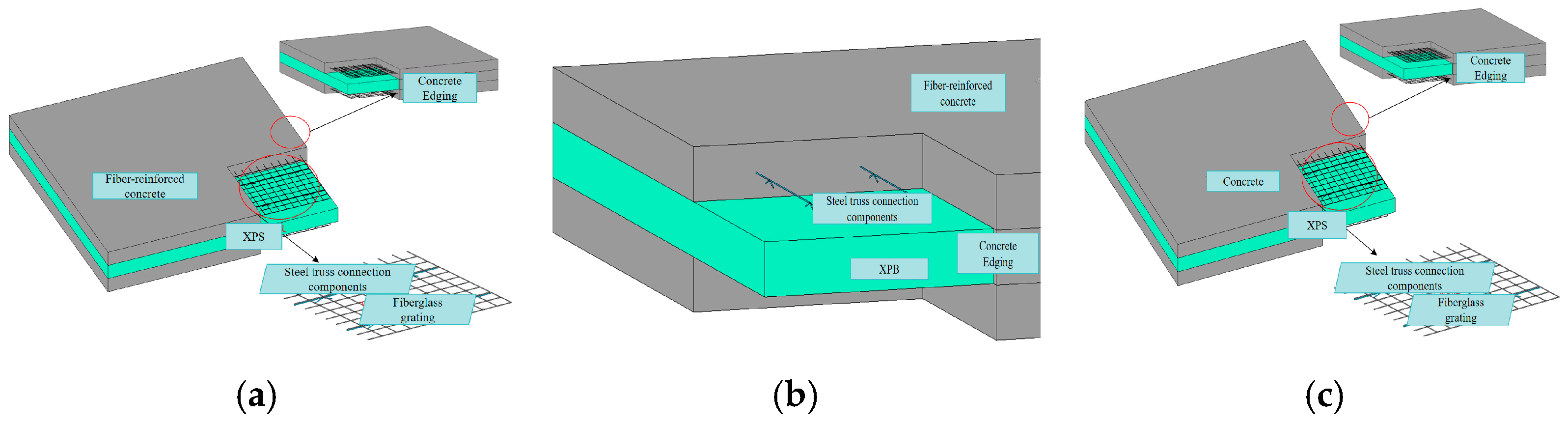

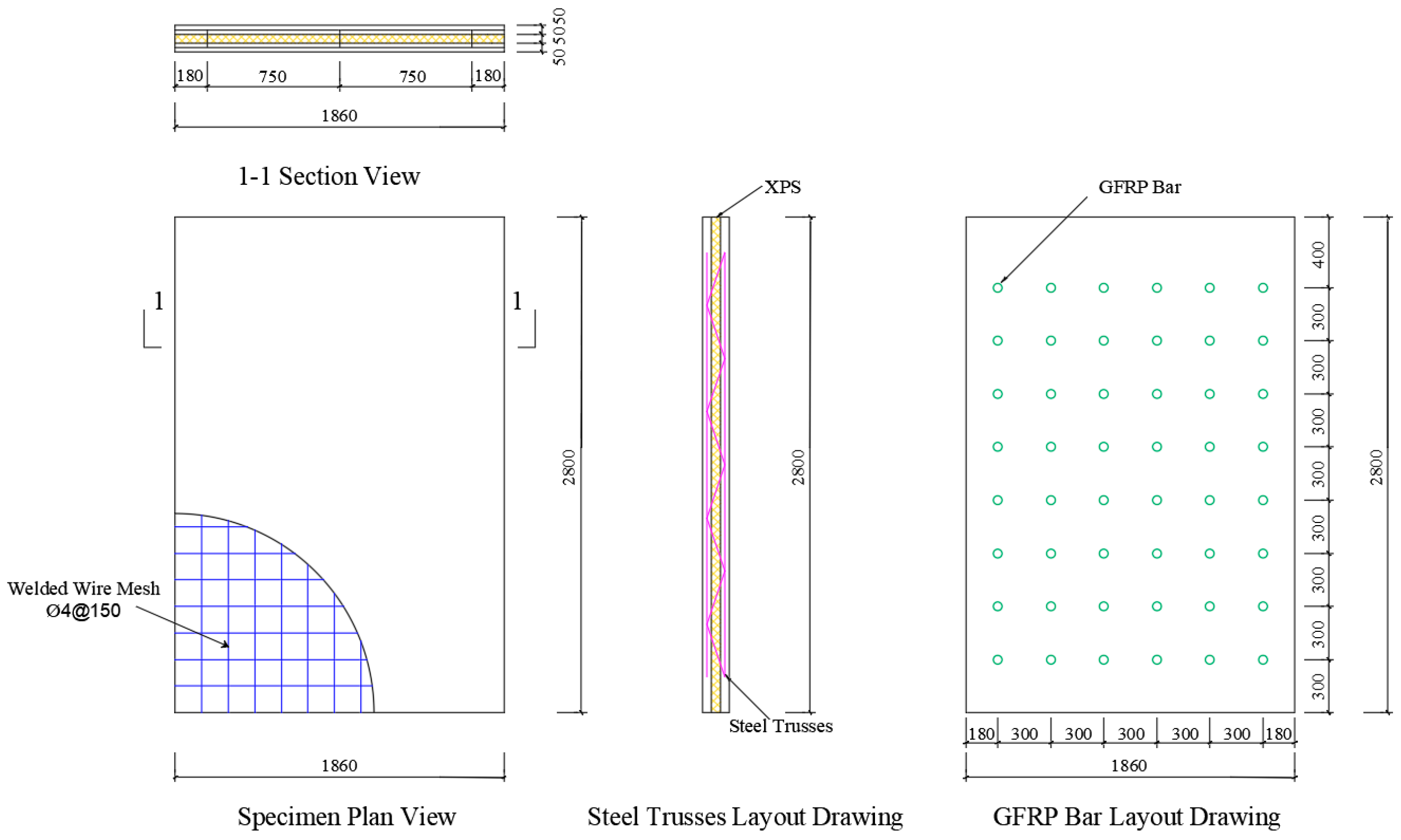

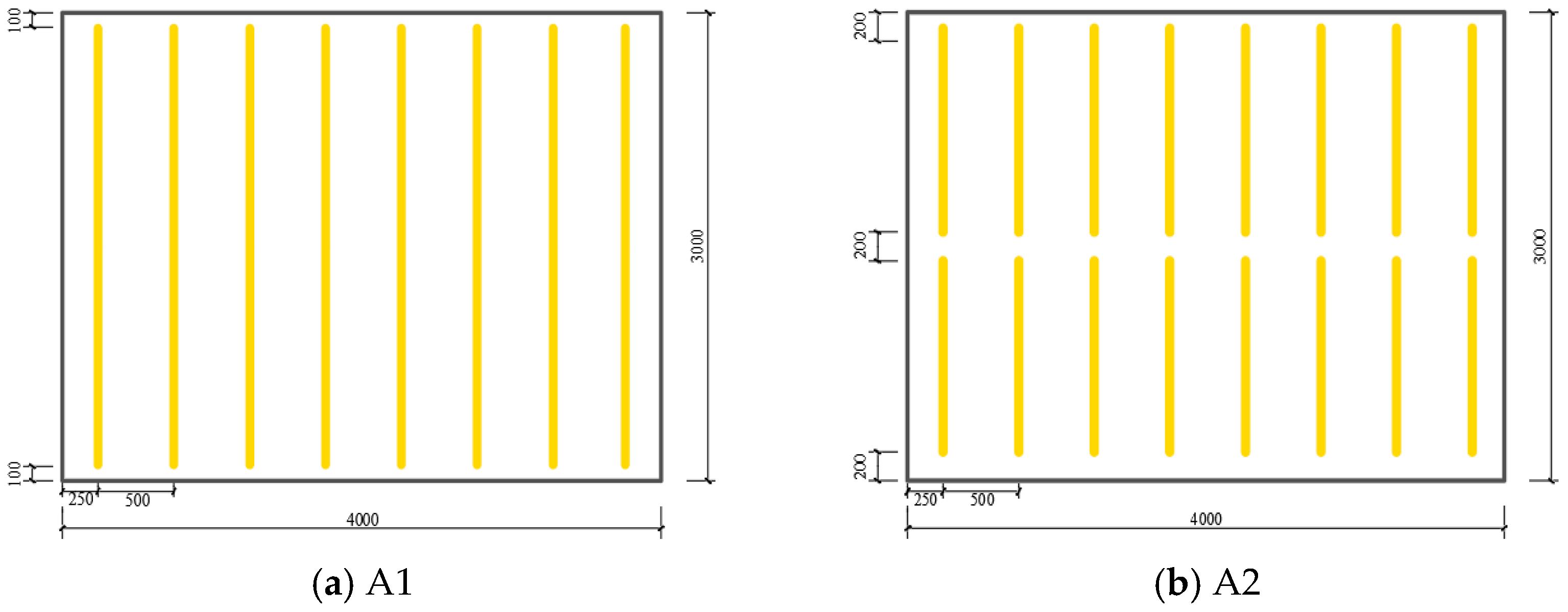

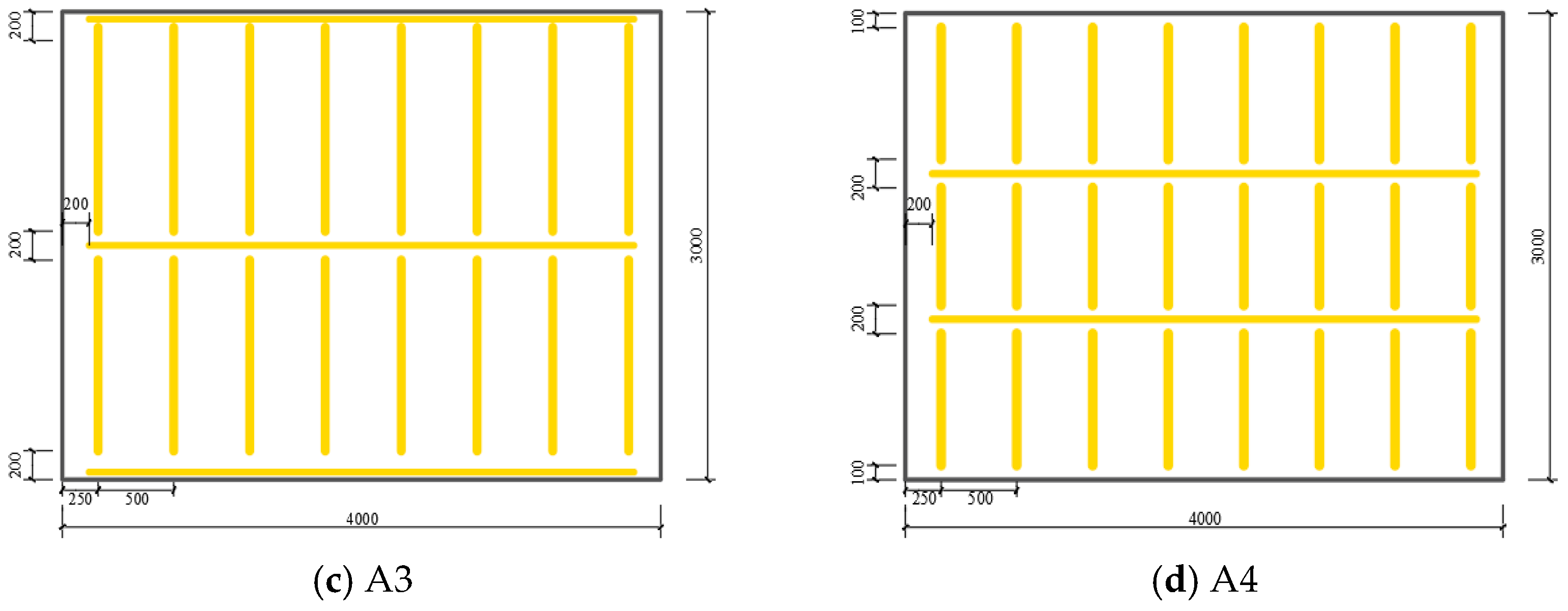

3.1. Wall-Panel Design

3.2. Constitutive Models

3.2.1. Steel-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (SFRC)

3.2.2. Steel Trusses and Glass-Fiber Grids

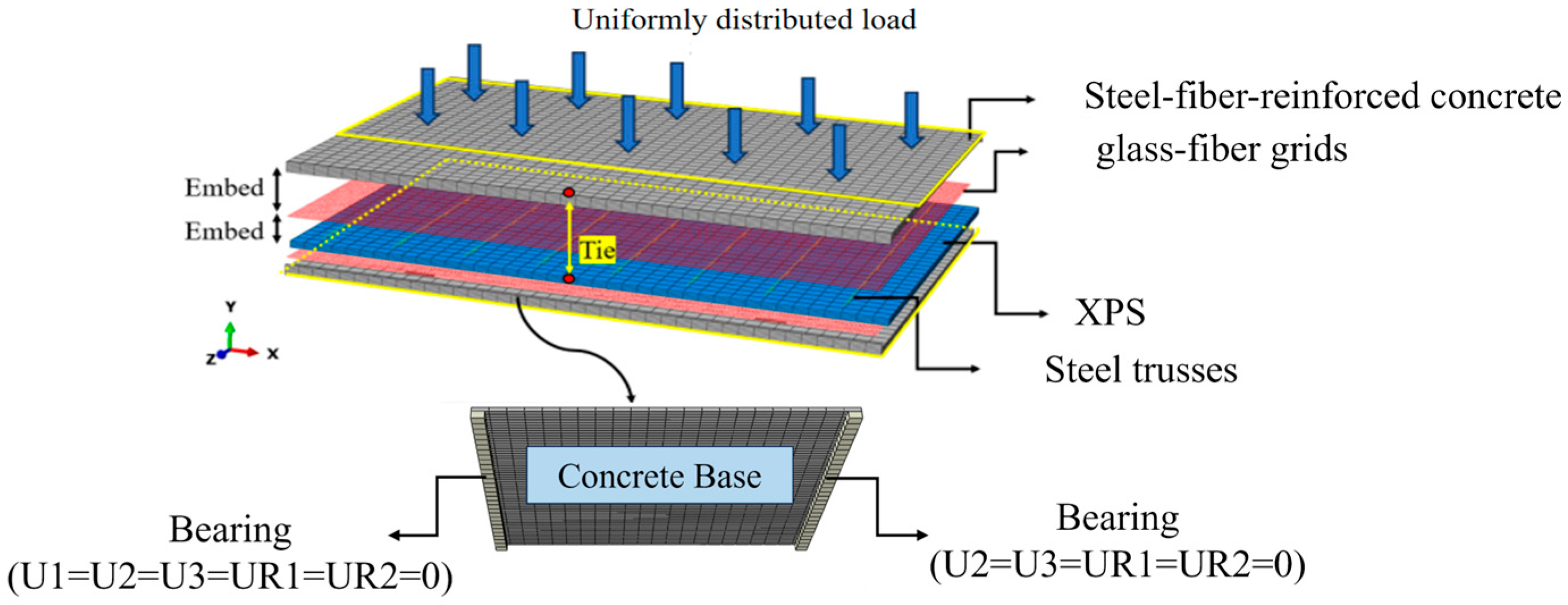

3.3. Element Types and Meshing

3.4. Boundary Conditions and Contacts

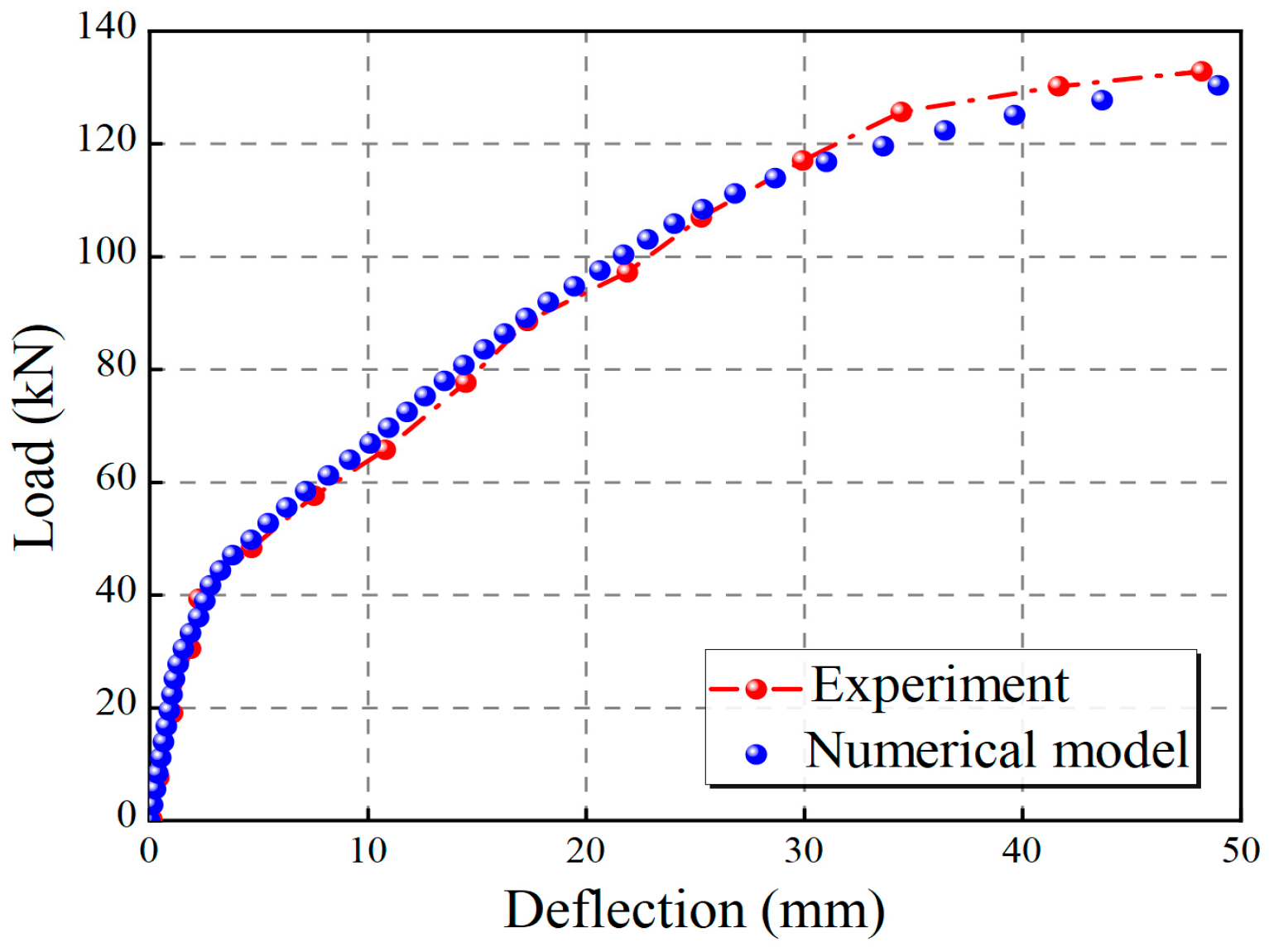

3.5. Finite Element Model Verification

3.6. Analysis of Typical Members

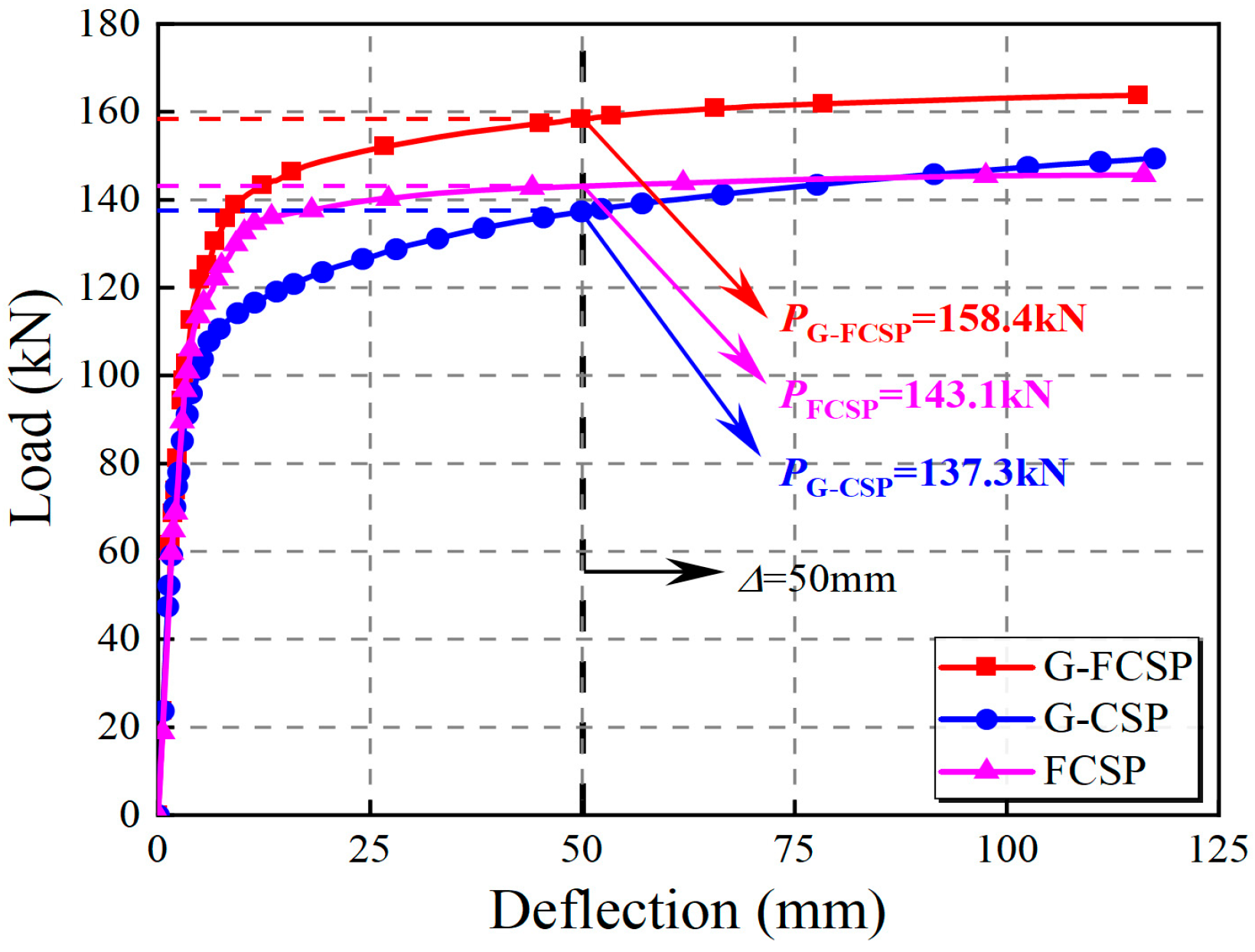

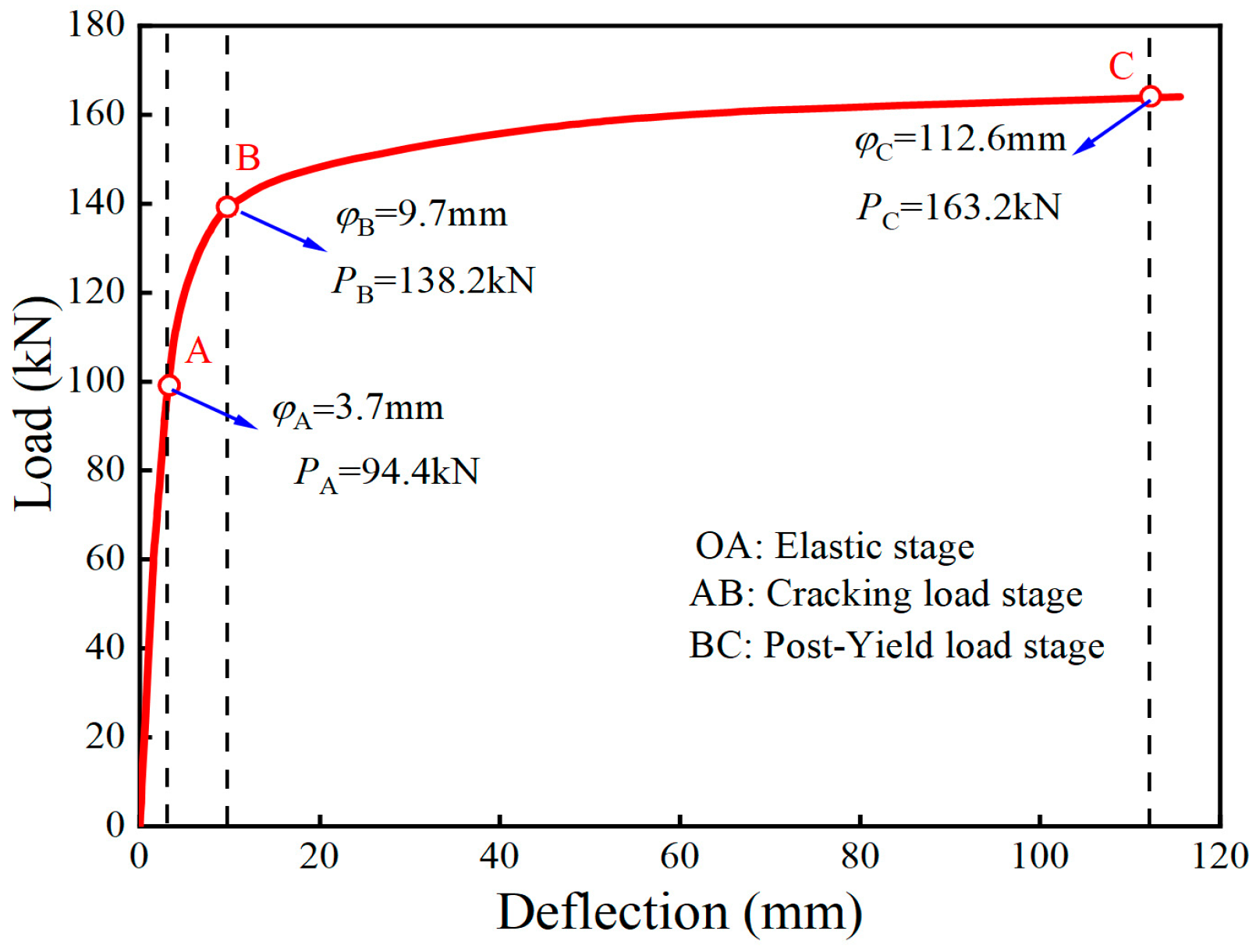

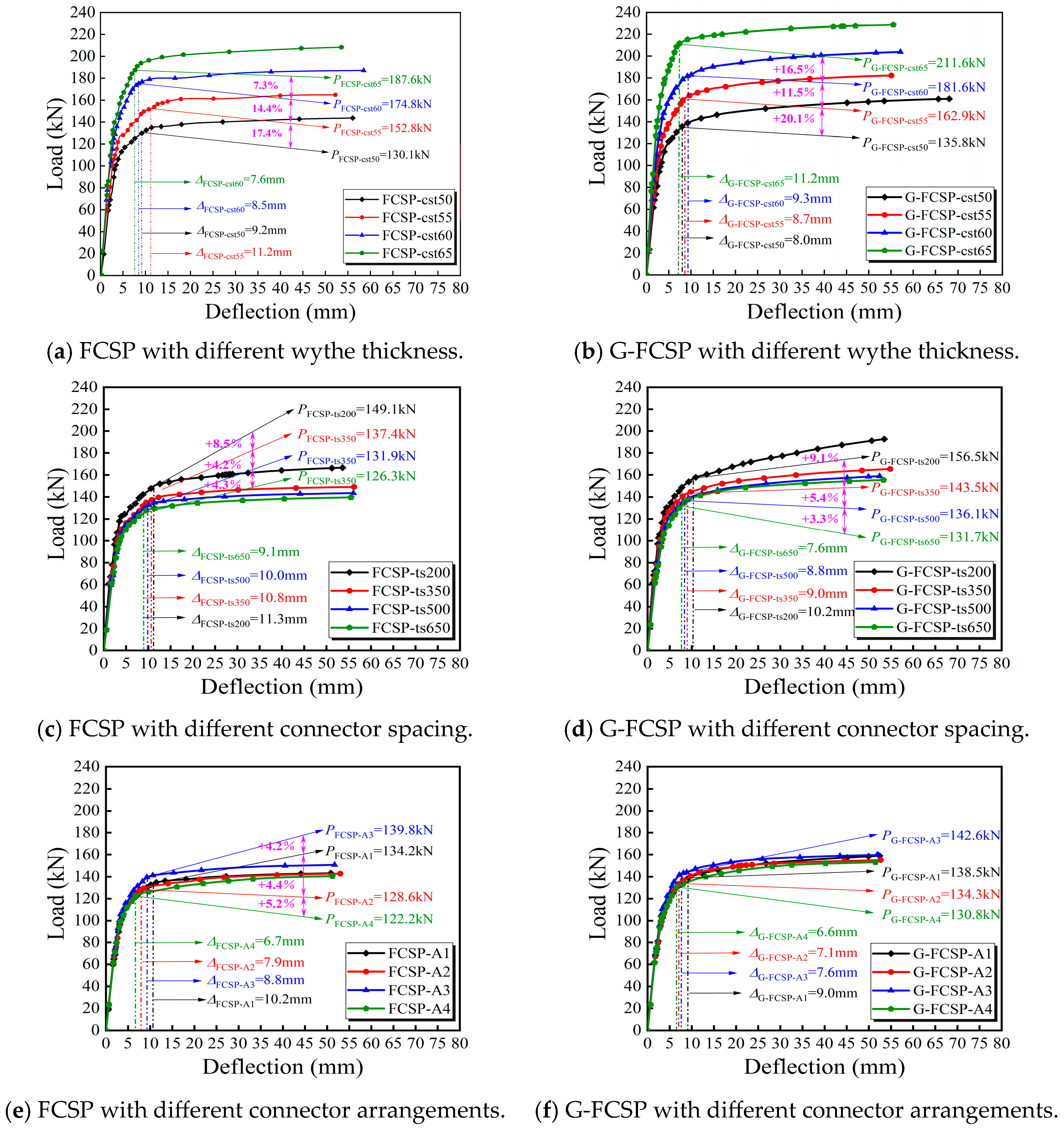

3.6.1. Load–Displacement Curves

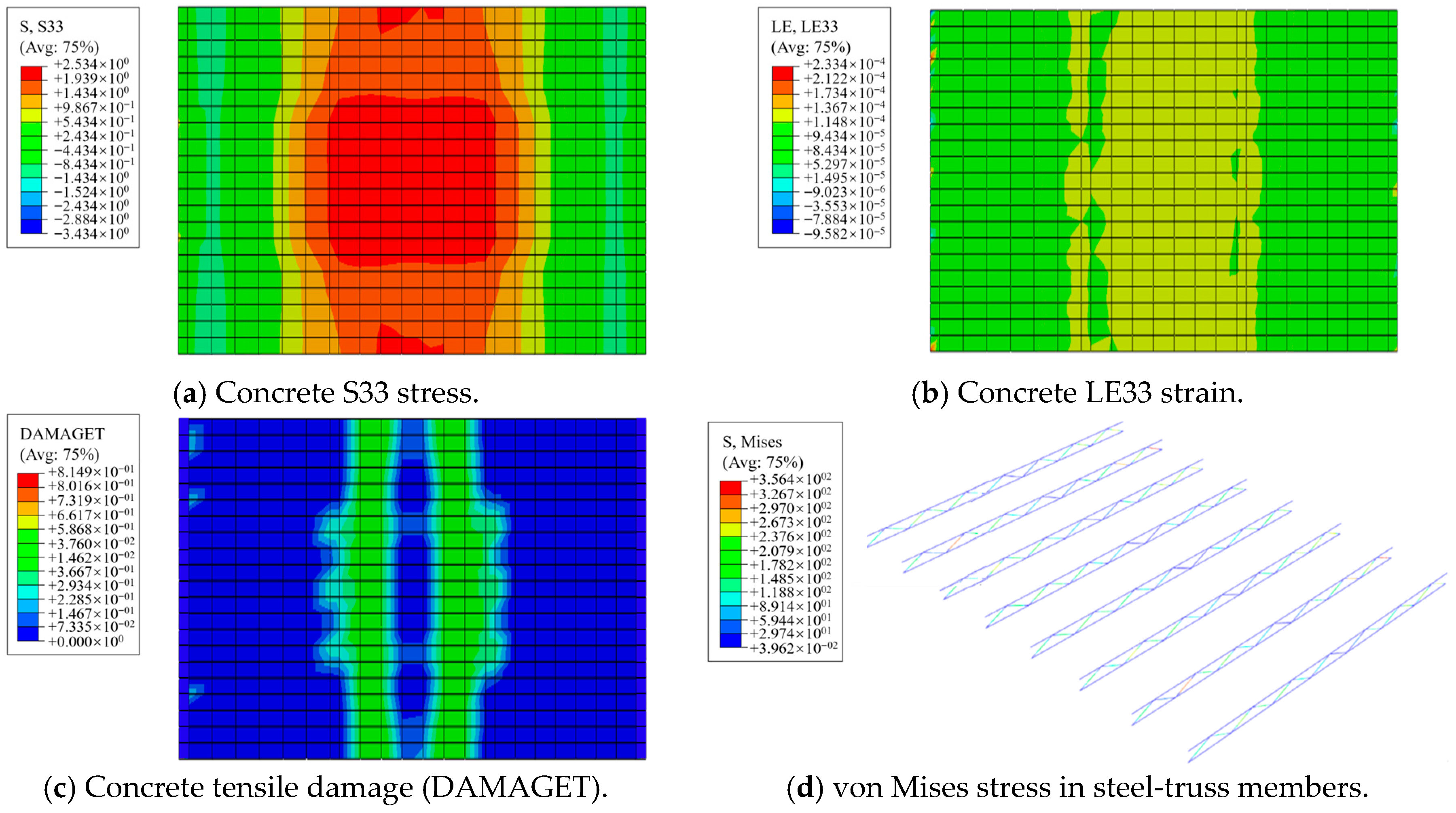

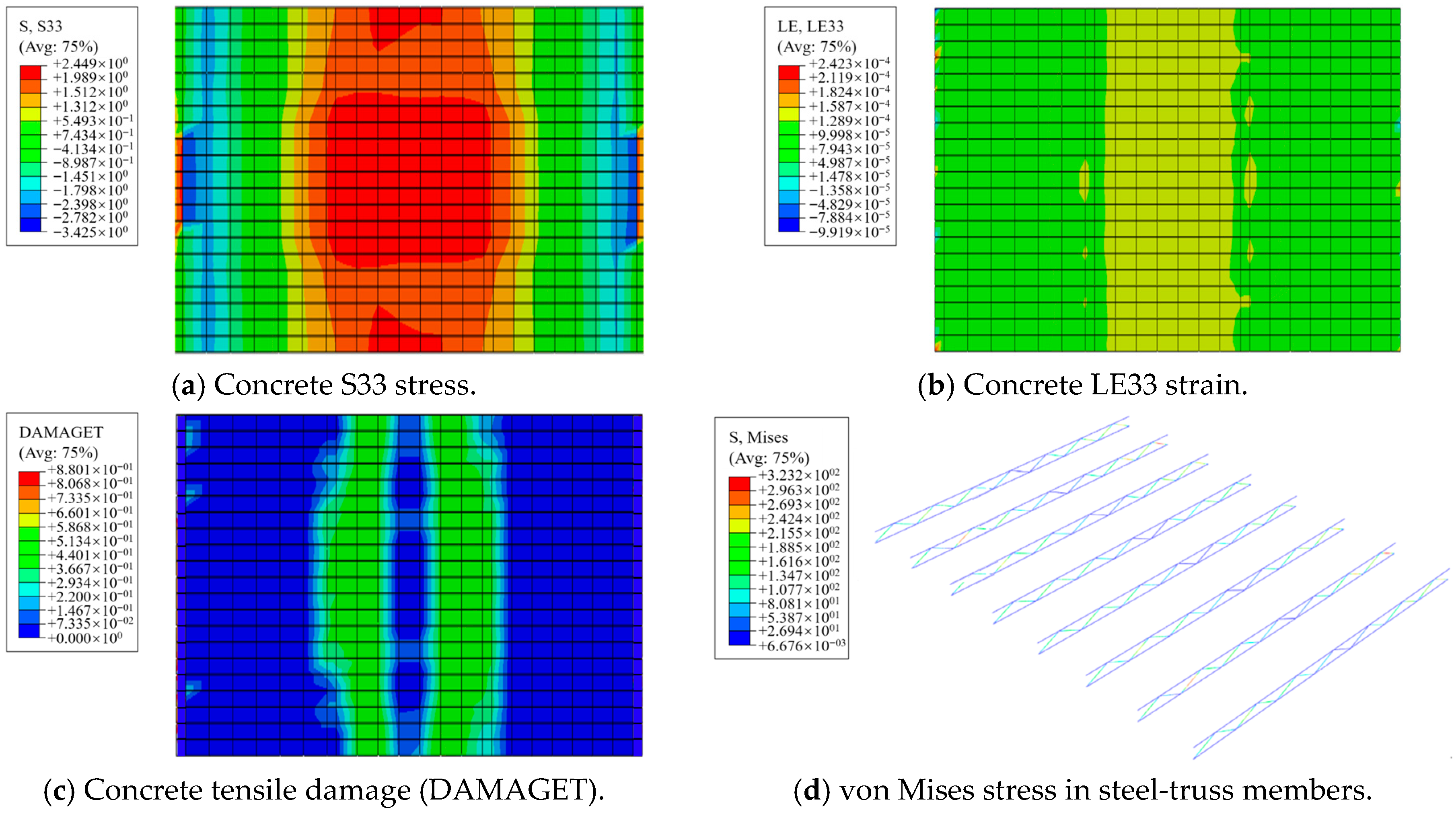

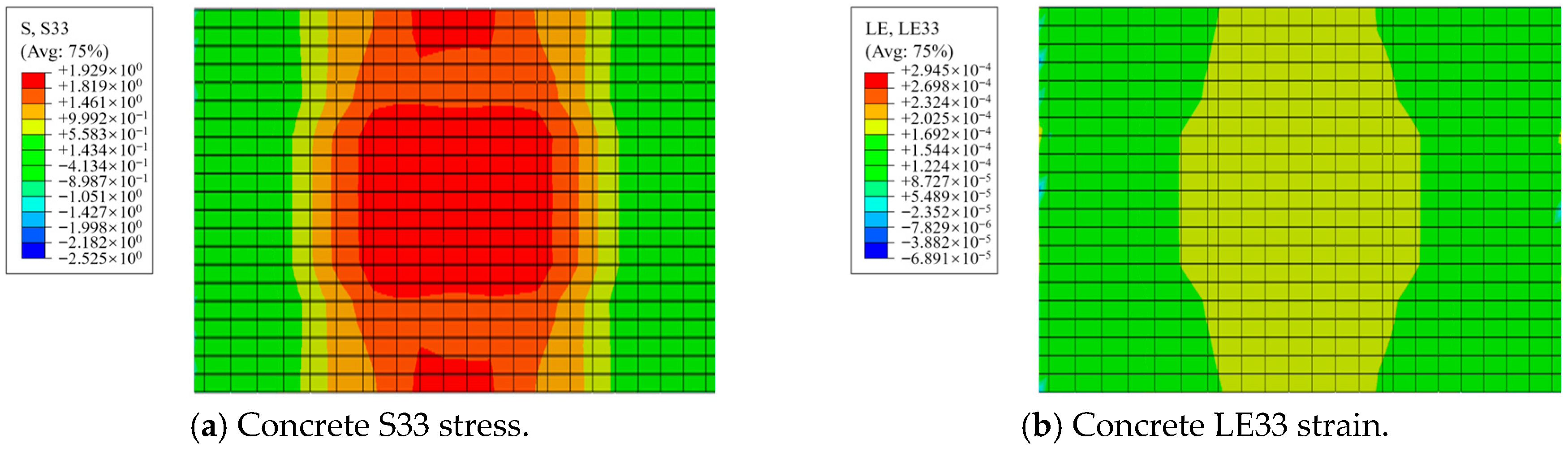

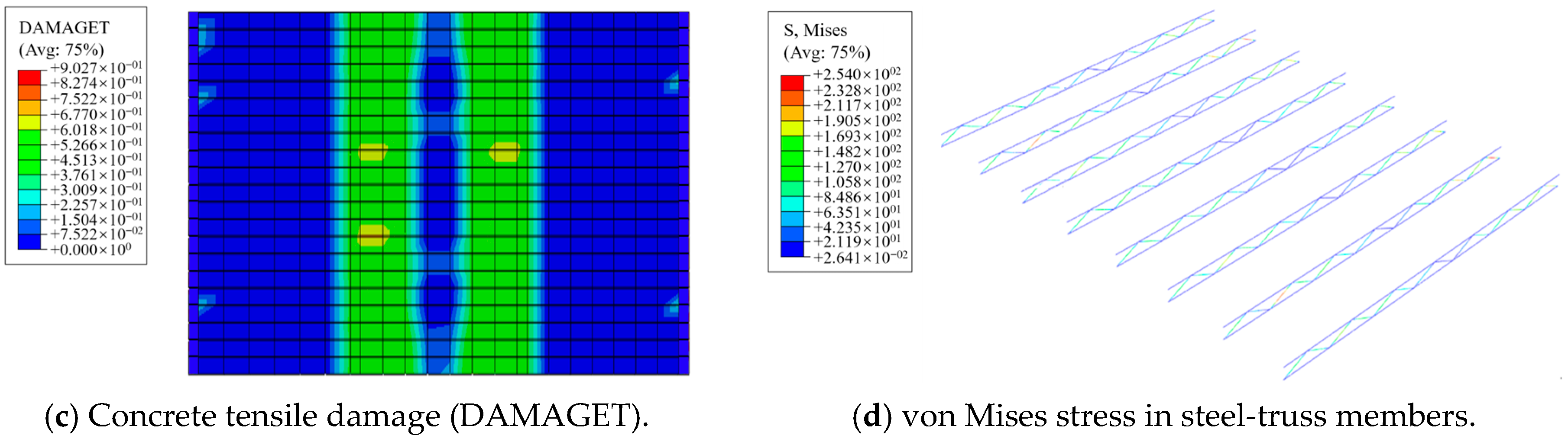

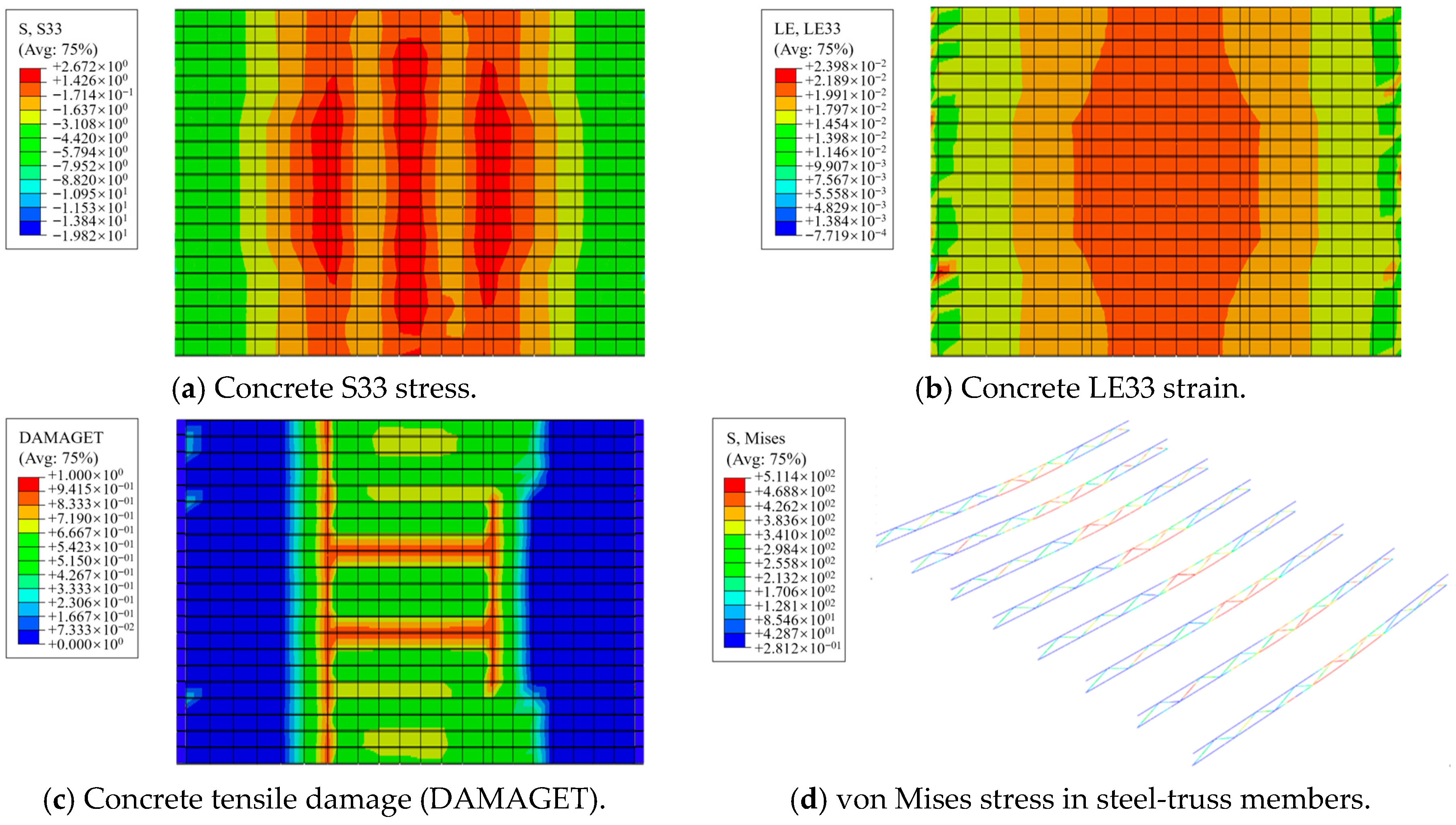

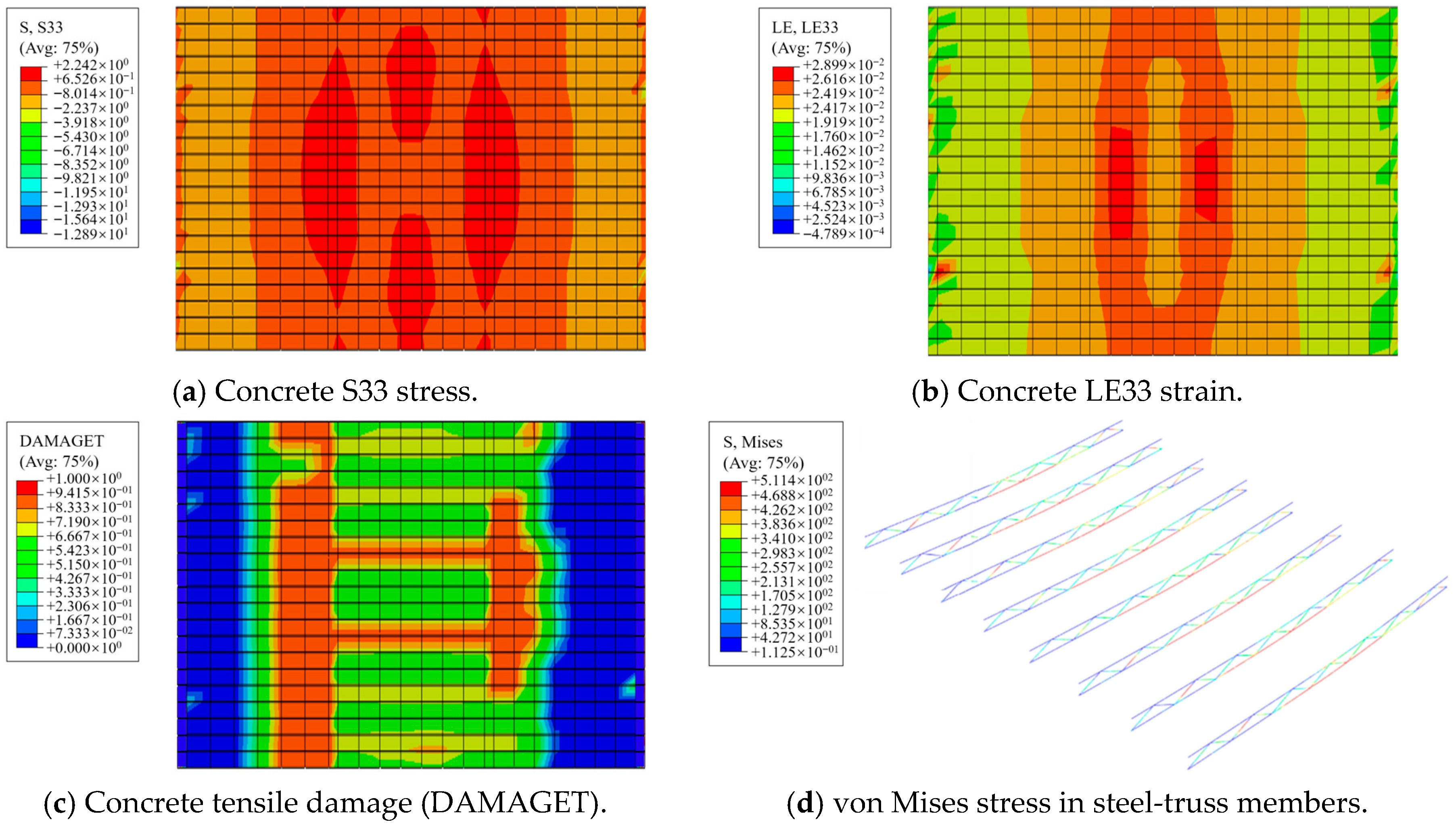

3.6.2. Contour-Plot Analysis

4. Parameter Analysis

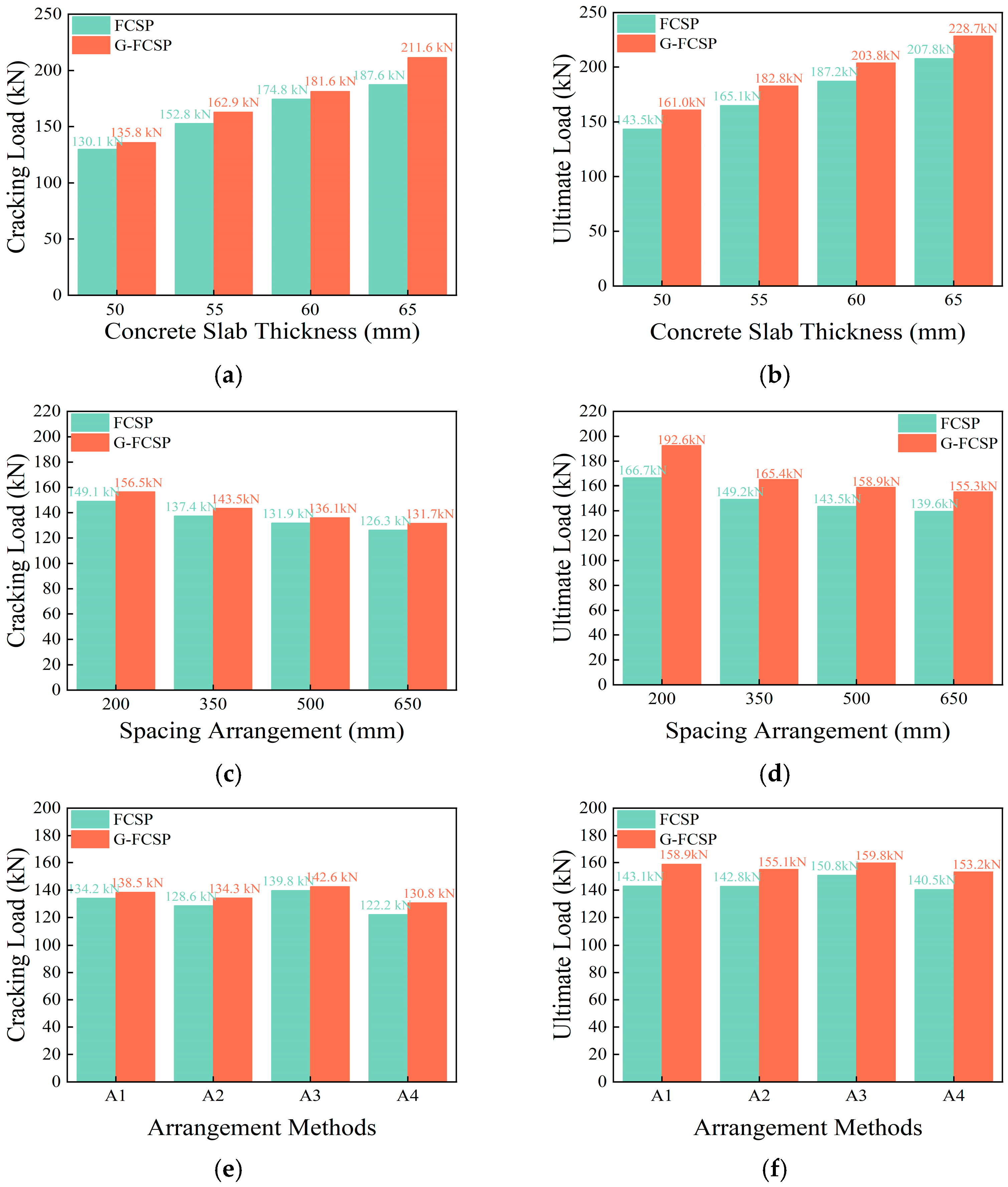

4.1. Cracking and Ultimate Load

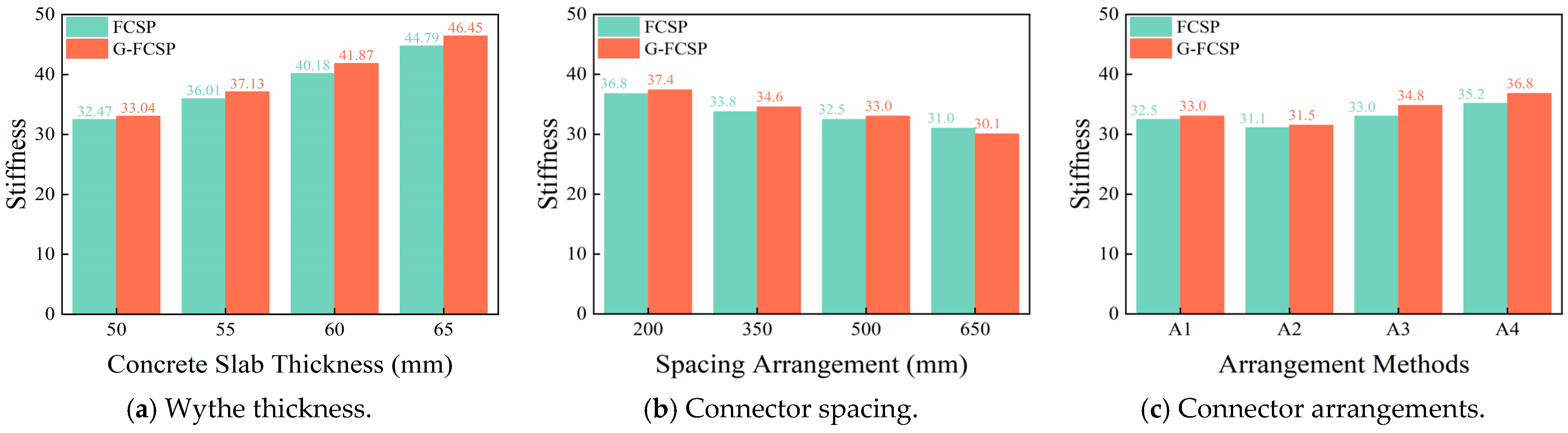

4.2. Stiffness at Cracking

5. Conclusions

- At a 1% steel-fiber volume fraction, the compressive strength increases by 7.8% relative to plain concrete. The strength gain diminishes at higher fiber contents, indicating 1% as the optimum content within this study. A compressive stress–strain law for the present SFRC mix was formulated based on Guo Zhenhai’s concrete model. The law agrees well with the measured curves. The fitted shape-parameter relations and the segmented law accurately predict the compressive behavior of SFRC.

- Analyses of typical panels show that steel fibers enhance overall integrity. Steel fibers provide effective restraint and delay crack initiation. At lower strain levels, SFRC panels sustain higher stress. Relative to plain-concrete panels, SFRC panels exhibit a 29.5% lower peak strain and 27.2% higher peak stress.

- Increasing wythe thickness markedly enhances panel load capacity. From 50 to 65 mm, the cracking load increases by 40.4%, with a concurrent 40.5% rise in panel stiffness. At the same thickness, G-FCSP exceeds FCSP by 6.9% in cracking load and 10.5% in ultimate load, confirming the synergy between grids and steel fibers. Greater wythe thickness is recommended where self-weight and cost permit. Connector spacing has a significant effect on overall stiffness. Reducing spacing from 500 to 200 mm raises G-FCSP ultimate load by 20.6%, mainly by mobilizing the steel-truss tension system. A full-height vertical connector layout is recommended to ensure structural integrity.

Further Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nam, S.; Yoon, J.; Kim, K.; Choi, B. Optimization of prefabricated components in housing modular construction. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Su, S.; Yuan, J.; Li, J.; Lou, F.; Wang, Q. Analyzing the environmental, economic, and social sustainability of prefabricated components: Modeling and case study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Tai, H.W.; Wang, T.; Qiao, L.; Cheng, K. Analyzing cost impacts across the entire process of prefabricated building components from design to application. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Li, L.; Sun, A.; Cao, X.; Yuan, J. How to combine different types of prefabricated components in a building to reduce construction costs and carbon emissions. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Gu, Y.; Xie, L.; Huang, Z. Automatic assembly of prefabricated components based on vision-guided robot. Autom. Constr. 2024, 162, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, T.; Mendis, P. Prefabricated building systems–design and construction. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghchesaraei, A.; Kaptan, M.V.; Baghchesaraei, O.R. Using prefabrication systems in building construction. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2015, 10, 44258–44262. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, J.; Sun, X.; Xue, Q.; Fan, C. Research and applications of prefabricated steel structure building systems. Eng. Mech. 2017, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Masood, R.; Roy, K. Review on prefabricated building technology. Technology 2022, 4, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, Z.S.M. Implementation of prefabricated building systems in Iraq. Al Nahrain J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 23, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Lora, F.F.; Sorensen, T.J.; Al-Rubaye, S.; Maguire, M. State-of-the-art and practice review in concrete sandwich wall panels: Materials, design, and construction methods. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbu, H.K.; Kothandapani, K. Enhancing impact resistance of concrete slabs. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2025, 19, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hegarty, R.; Kinnane, O. Review of precast concrete sandwich panels and their innovations. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 233, 117145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Xiong, F.; Liu, Y.; Ge, Q. Flexural performance of novel ECC-RC composite sandwich panels. Eng. Struct. 2023, 292, 116547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugahed Amran, Y.H.; Rashid, R.S.M.; Hejazi, F.; Safiee, N.A.; Abang Ali, A.A. Response of precast foamed concrete sandwich panels to flexural loading. J. Build. Eng. 2016, 7, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcous, G.; Kodsy, A.; El-Khier, M.A. Flexural behavior of composite ultrahigh-performance concrete sandwich wall panels. J. Archit. Eng. 2024, 30, 04024007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, S.; Ali, M.S.M.; Sheikh, A.H.; Elchalakani, M.; Xie, T. An investigation into the feasibility of normal and fibre-reinforced ultra-high performance concrete multi-cell and composite sandwich panels. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 41, 102728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Khayat, K.H.; Bao, Y. Flexural behaviors of fiber-reinforced polymer fabric reinforced ultra-high-performance concrete panels. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 93, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysinghe, C.M.; Thambiratnam, D.P.; Perera, N.J. Flexural performance of an innovative hybrid composite floor plate system comprising glass–fibre reinforced cement, polyurethane and steel laminate. Compos. Struct. 2013, 95, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hegarty, R.; West, R.; Reilly, A.; Kinnane, O. Composite behaviour of fibre-reinforced concrete sandwich panels with FRP shear connectors. Eng. Struct. 2019, 198, 109475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Q.; Dai, J.G. Flexural performance of precast geopolymer concrete sandwich panel enabled by FRP connector. Compos. Struct. 2020, 248, 112563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H.; Kim, H.J. Composite effects of shear connectors used for lightweight-foamed-concrete sandwich wall panels. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 29, 101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Guo, Z.; Liu, J. Composite behavior of sandwich panels with w-shaped SGFRP connectors. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 1889–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombeda, M.J.; Naito, C.J.; Quiel, S.E. Flexural performance of precast concrete insulated wall panels with various configurations of ductile shear ties. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 33, 101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI 544.1R-96; Report on Fiber Reinforced Concrete. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 1996.

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- Meng, S.Q.; Jiao, C.J.; Ouyang, X.W.; Niu, Y.F.; Fu, J.Y. Effect of steel fiber-volume fraction and distribution on flexural behavior of Ultra-high performance fiber reinforced concrete by digital image correlation technique. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 320, 126281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.S.; Hwang, S. Mechanical properties of high-strength steel fiber-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2004, 18, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CECS 13:2009; Standard Test Methods for Fiber Reinforced Concrete. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2010. (In Chinese)

- Guo, Z.H. Strength and Constitutive Relation of Concrete-Principle and Application; China Architecture and Building 541 Press: Beijing, China, 2004. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 08SJ110-2; Precast Concrete Exterior Wall Panels. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese)

- Moradi, M.; Bagherieh, A.R.; Esfahani, M.R. Constitutive modeling of steel fiber-reinforced concrete. Int. J. Damage Mech. 2020, 29, 388–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafighfard, T.; Cender, T.A.; Demir, E. Additive manufacturing of compliance optimized variable stiffness composites through short fiber alignment along curvilinear paths. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafighfard, T.; Mieloszyk, M. Experimental and numerical study of the additively manufactured carbon fibre reinforced polymers including fibre Bragg grating sensors. Compos. Struct. 2022, 299, 116027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafighfard, T.; Asgarkhani, N.; Kazemi, F.; Yoo, D.Y. Transfer learning on stacked machine-learning model for predicting pull-out behavior of steel fibers from concrete. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 158, 111533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, S.; Fan, M.; Rees, D.W.A. Predicting pull-out behaviour of 4D/5D hooked end fibres embedded in normal-high strength concrete. Eng. Struct. 2018, 172, 967–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrech, S.; Etse, G.; Meschke, G.; Caggiano, A.; Martinelli, E. Meso- and macroscopic models for fiber-reinforced concrete. In Computational Modelling of Concrete Structures, Proceedings of EURO-C 2010, Schladming, Austria, 15–18 March 2010; Bicanic, N., de Borst, R., Mang, H., Meschke, G., Eds.; CRC Press: Leiden, The Netherlands; Balkema: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Anandamurthy, A.; Guna, V.; Ilangovan, M.; Reddy, N. A review of fibrous reinforcements of concrete. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2017, 36, 519–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksouri, I.; De Almeida, O.; Haddar, N. Long term ageing of polyamide 6 and polyamide 6 reinforced with 30% of glass fibers: Physicochemical, mechanical and morphological characterization. J. Polym. Res. 2017, 24, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhao, L.; Yuan, L.X.; Wu, G.; Zheng, R.; Mu, Y.S. Research on Flexural Performance of Basalt Fiber-Reinforced Steel–Expanded Polystyrene Foam Concrete Composite Wall Panels. Buildings 2025, 15, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avudaiappan, S.; Saavedra Flores, E.I.; Araya-Letelier, G.; Thomas, W.J.; Raman, S.N.; Murali, G.; Amran, M.; Karelina, M.; Fediuk, R.; Vatin, N. Experimental investigation on composite deck slab made of cold-formed profiled steel sheeting. Metals 2021, 11, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.S.; Yuan, J.M.; Pang, H.X.; Huang, Z.M.; Guo, Y.Q.; Wei, J.X.; Yu, Q.J. UHPC-XPS insulation composite board reinforced by glass fiber mesh: Effect of structural design on the heat transfer, mechanical properties and impact resistance. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 75, 106935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.Y.; Du, L.F.; Chen, G.X.; Yue, L.F.; Cui, C.X.; Ge, M.M. Experimental and numerical study on the shear performance of stainless steel-GFRP connectors for use in precast concrete sandwich panels. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.T. Study on the Effect of Connectors on the Structural Performance of Prefabricated Concrete Sandwich Thermal Insulation External Wall Panel; Hefei University of Technology: Hefei, China, 2019. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- GB 50204-2015; Code for Quality Acceptance of Concrete Structure Engineering Construction. Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015. (In Chinese)

| Specific Surface Area/(m2/kg) | Setting Time/min | Compressive Strength/MPa | Flexural Strength/MPa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | 3 Days | 28 Days | 3 Days | 28 Days | |

| 350 | 95 | 150 | 28.5 | 49.3 | 5.6 | 7.9 |

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | CaO | Fe2O3 | TiO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58.13 | 25.14 | 5.18 | 7.12 | 4.43 |

| Loss | Al2O3 | CaO | SiO2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.52 | 1.57 | 0.18 | 95.73 |

| Length/mm | Diameter/mm | Aspect Ratio | Tensile Strength/MPa | Elastic Modulus/GPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 0.8 | 25 | 1200 | 200 |

| Group | Water | Cement | Sand | Aggregates | Steel Fiber Volume Fraction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 164 | 430 | 780 | 1024 | 0% |

| 2 | 164 | 430 | 780 | 1024 | 0.5% |

| 3 | 164 | 430 | 780 | 1024 | 1% |

| 4 | 164 | 430 | 780 | 1024 | 1.5% |

| Specimen ID | Steel Fiber Volume Fraction (%) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Average Compressive Strength (MPa) | Strength Growth Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1 | 0 | 50.6 | 51.1 | |

| 1-2 | 50.0 | — | ||

| 1-3 | 52.7 | |||

| 2-1 | 0.5 | 53.5 | 54.0 | 5.6 |

| 2-2 | 52.6 | |||

| 2-3 | 55.9 | |||

| 3-1 | 1.0 | 54.7 | 55.1 | |

| 3-2 | 55.7 | 7.8 | ||

| 3-3 | 54.8 | |||

| 4-1 | 1.5 | 56.2 | 56.0 | |

| 4-2 | 55.5 | 9.5 | ||

| 4-3 | 56.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Chen, Y. Flexural Performance of Prefabricated Steel-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Wall Panels: Finite Element Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 4370. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234370

Li Q, Wang Z, Zhou S, Chen Y. Flexural Performance of Prefabricated Steel-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Wall Panels: Finite Element Analysis. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4370. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234370

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Quanpeng, Zhenyu Wang, Shiru Zhou, and Yangyang Chen. 2025. "Flexural Performance of Prefabricated Steel-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Wall Panels: Finite Element Analysis" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4370. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234370

APA StyleLi, Q., Wang, Z., Zhou, S., & Chen, Y. (2025). Flexural Performance of Prefabricated Steel-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Wall Panels: Finite Element Analysis. Buildings, 15(23), 4370. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234370