1. Introduction

The global building and construction sector remains a dominant contributor to climate change, accounting for 34% of global carbon dioxide emissions and consuming 32% of the world’s total energy [

1]. A striking 18% of global emissions are attributed to building materials such as cement and steel, with cement production alone responsible for approximately 7% of worldwide anthropogenic CO

2 emissions [

2,

3]. This underscores an urgent imperative to develop and implement sustainable alternatives across all domains of civil engineering, especially as nearly half of the buildings that will exist by 2050 have not yet been constructed [

4]. While considerable research attention has been directed toward low-carbon above-ground structures, underground construction—a rapidly expanding frontier—presents equally critical opportunities for emissions reduction [

5,

6]. Innovative ground stabilization techniques in this field can minimize or eliminate permanent material consumption, directly addressing the lagging decarbonization of embodied carbon from building materials [

7,

8].

Water-rich sand strata represent particularly challenging geological formations for underground development, characterized by low cohesive strength, high permeability, and poor self-stability [

9,

10,

11]. Conventional excavation in these hydrogeological settings frequently triggers catastrophic sand–water inrush disasters, necessitating robust pre-excavation stabilization. Traditional methods such as chemical grouting or deep soil mixing often involve high-emission materials or energy-intensive processes [

12,

13], highlighting the need for more sustainable and reversible ground improvement solutions. Among available techniques, Artificial Ground Freezing (AGF) offers a reversible, resource-efficient alternative for traversing these problematic formations due to its superior water-sealing capacity.

AGF is widely used for stabilizing water-rich formations because it provides effective water sealing, can be applied in a variety of geological settings, and avoids the permanent incorporation of chemical agents [

14,

15,

16]. As a temporary and reversible ground support method, AGF creates stability through phase change rather than through the permanent addition of construction materials, which makes it broadly compatible with circular economy concepts. However, the potential sustainability benefits of AGF depend strongly on freezing efficiency, and energy consumption can be substantial if the design is overly conservative.

The mechanical behavior of frozen soils has been extensively investigated through conventional triaxial testing [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], typically revealing a characteristic three-stage strength variation with confining pressure: initial strengthening followed by pressure melting induced weakening and potential re-strengthening at extremely high pressures [

22,

23]. However, these conventional approaches suffer from two critical limitations: they predominantly employ simplified stress paths (

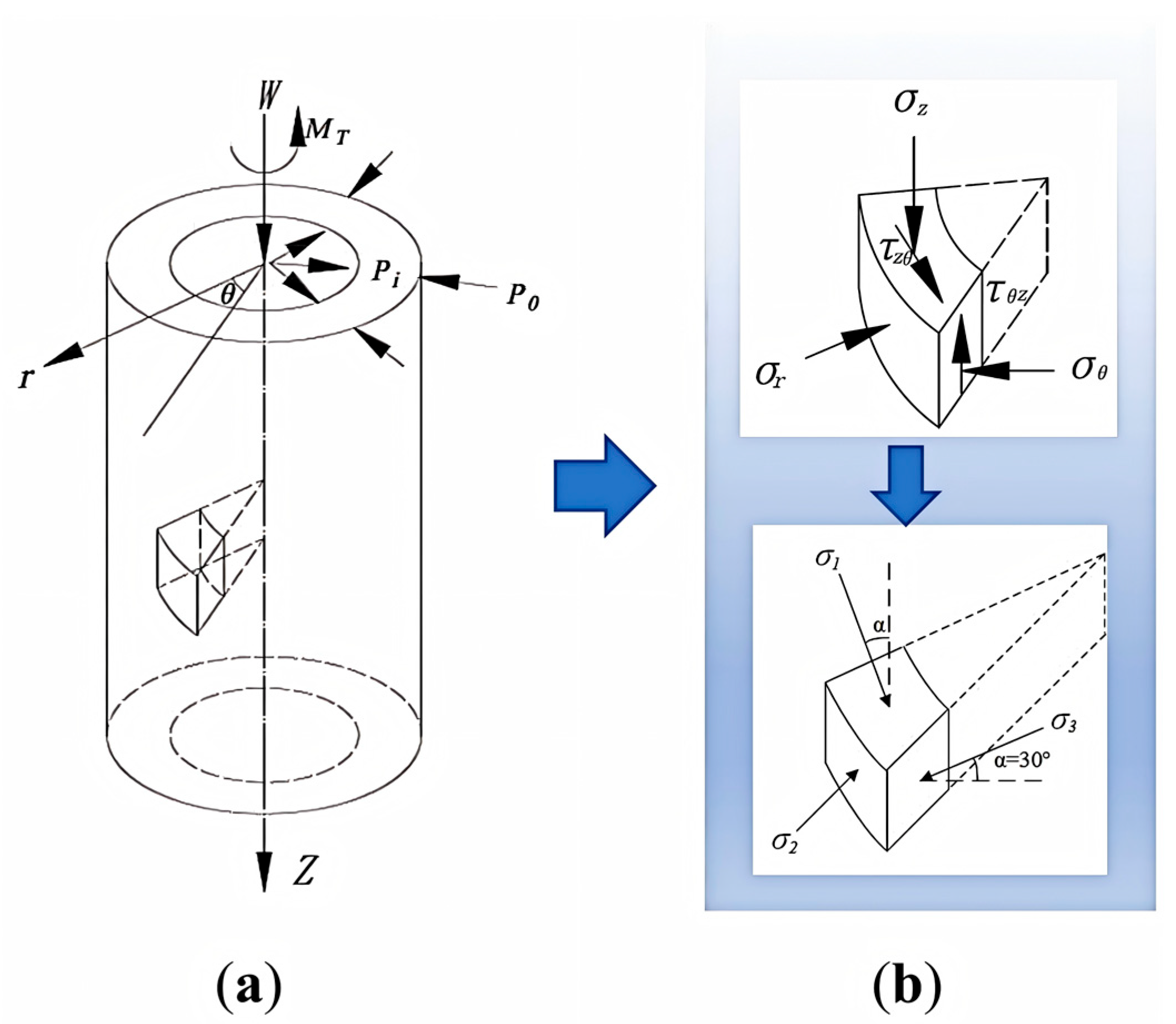

σ1 >

σ2 =

σ3) that poorly represent the true three-dimensional stress states in actual frozen walls, and they almost universally rely on unpressurized freezing protocols where ice formation occurs under zero confinement.

This second limitation is particularly significant. In situ freezing during AGF occurs under substantial geostatic stresses, yet conventional laboratory studies typically freeze specimens without confining pressure, creating ice microstructure that may not reflect field conditions [

24]. Advanced apparatuses like hollow cylinder and true triaxial devices have begun to address stress path limitations [

25,

26,

27,

28], with studies demonstrating the importance of principal stress rotation and intermediate principal stress effects on frozen soil behavior [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. However, the critical influence of pressurized freezing—where ice crystallization occurs under confining pressure—on the resulting mechanical response remains largely unquantified.

Three significant research gaps persist from both mechanical and sustainability perspectives: (1) The fundamental differences in mechanical behavior between pressurized and unpressurized frozen sand remain poorly characterized, particularly under complex stress paths relevant to practical applications. (2) The microstructural mechanisms responsible for the distinct mechanical responses of pressurized frozen soils are not well understood. (3) The potential for mechanical insights to reduce AGF’s carbon footprint through optimized design remains largely unexplored.

This study bridges these gaps through an integrated experimental and analytical investigation of pressurized frozen sand under directional shear conditions. Specifically, we conduct the following: (1) Employ a custom-developed frozen soil hollow cylinder apparatus (FS-HCA) to simulate in situ pressurized freezing (0.5–6 MPa) and complex stress paths (b = 0.5, α = 30°). (2) Systematically quantify the influence of mean principal stress (p) on the deformation, strength, and failure mechanisms of pressurized frozen saturated medium sand at −10 °C. (3) Develop a practical failure criterion and identify key behavioral transitions to inform energy-efficient AGF design. (4) Provide microstructural interpretations for the observed macroscopic responses. The outcomes of this research provide both scientific understanding and practical tools to advance AGF as a sustainable ground stabilization technology, supporting the construction industry’s transition toward low-carbon underground development in challenging hydrogeological conditions.

3. Results

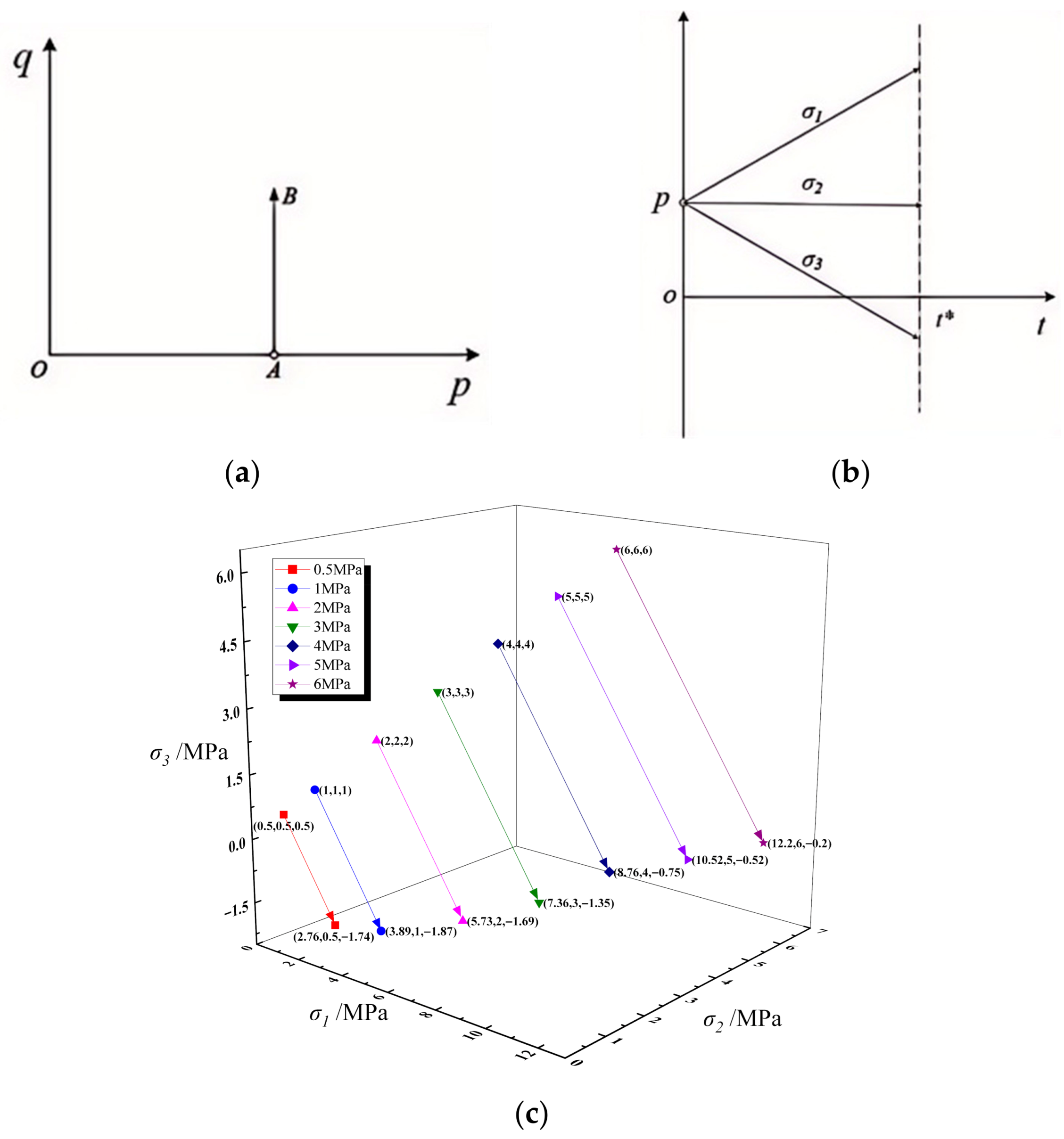

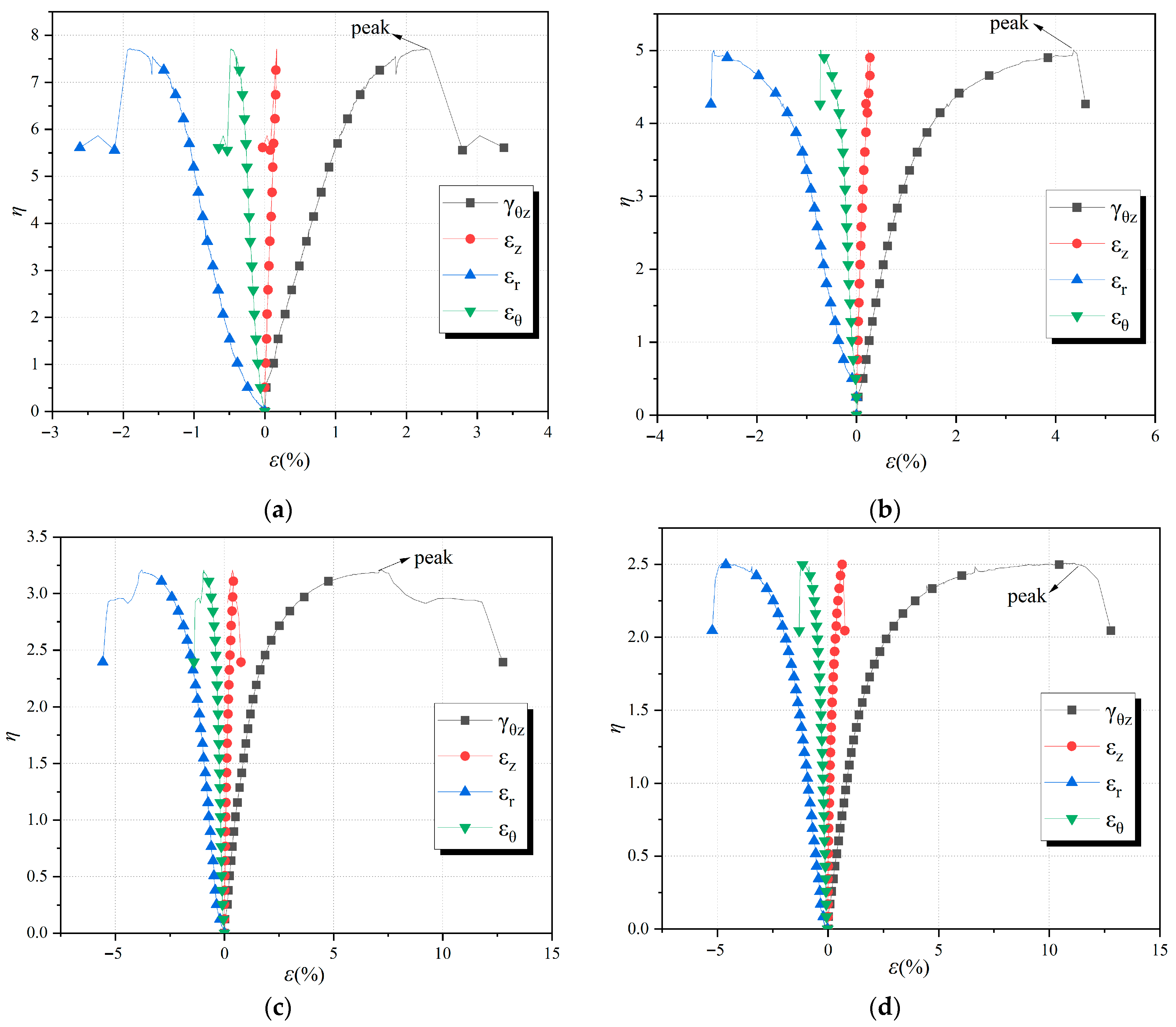

3.1. Consolidation Behavior and Its Implications for Ice Content

The mechanical properties of frozen soil are intrinsically governed by its ice content, which is itself a function of the initial porosity and water content before freezing. The isotropic consolidation phase, conducted under varying mean principal stresses (

p), precisely engineered these initial conditions.

Figure 6 delineates the compression behavior, plotting the void ratio (

e) against the consolidation pressure (

p). The curve exhibits a characteristic non-linear decay, indicative of the progressive rearrangement and compression of the sand skeleton. The associated reduction in total water mass, quantified in

Table 2, directly translates to a lower volume of freezable water. Consequently, the post-freezing ice content is not a constant but a variable intrinsically linked to the pre-shear stress history. This controlled variation in initial state is a critical, often overlooked, factor that underpins the subsequent interpretation of the frozen soil’s mechanical behavior, as the cementing ice matrix forms within a pre-compacted and dewatered soil fabric.

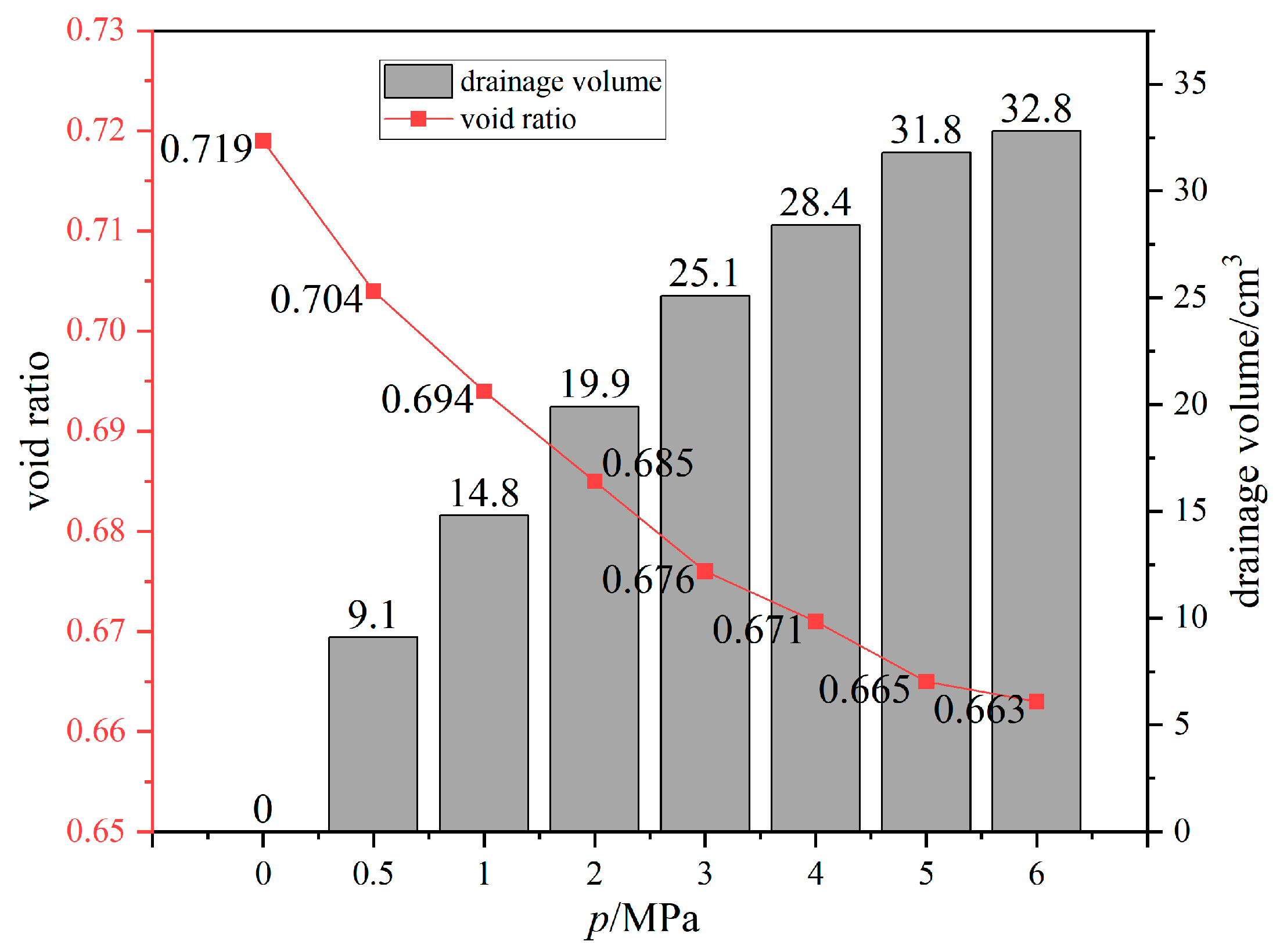

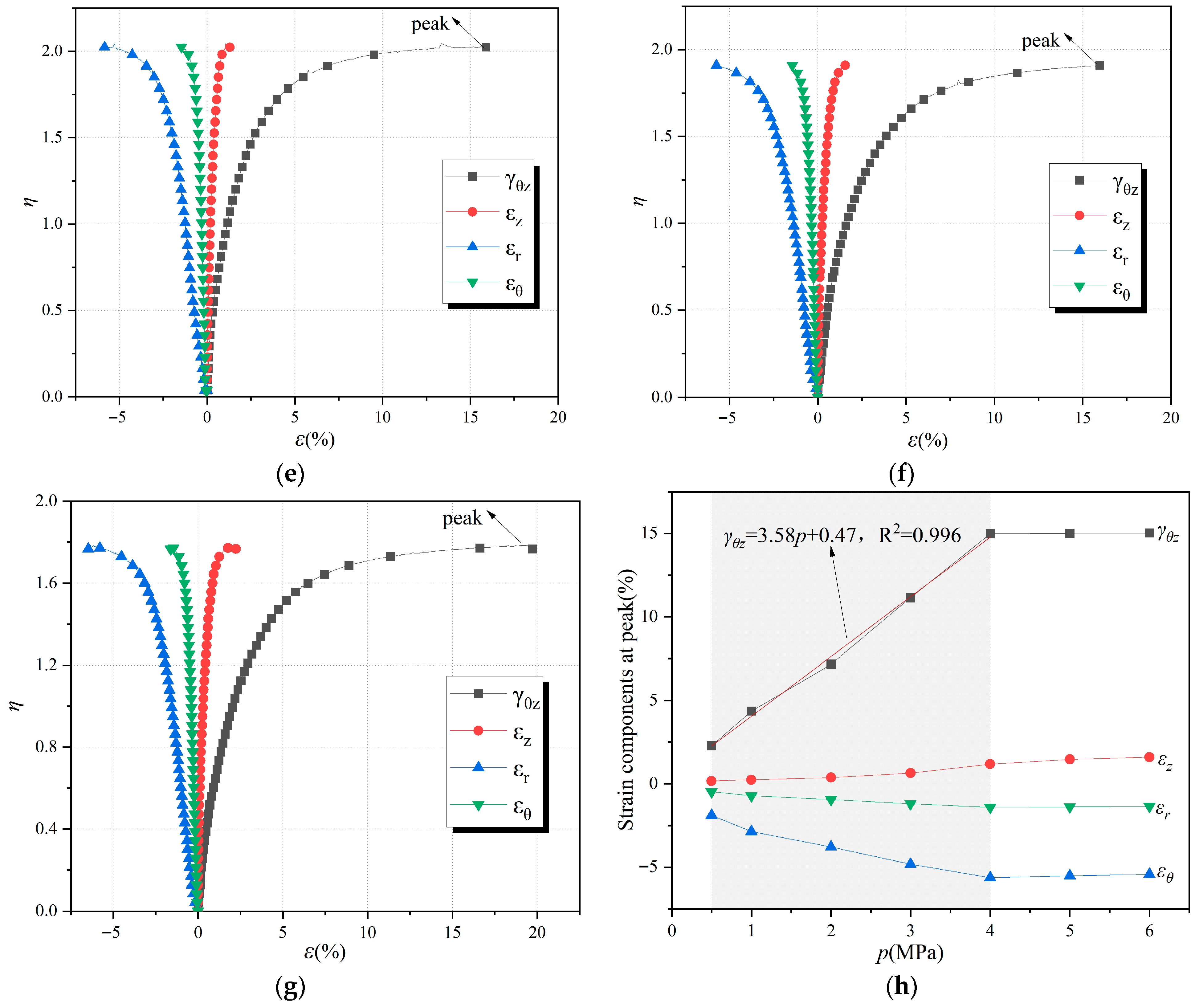

3.2. Evolution of Directional Shear Strains and Deformation Mechanisms

The strain development during directional shear, expressed as a function of the stress ratio (

η =

q/

p), reveals profound insights into the deformation mechanisms of pressurized frozen sand. The four strain components—axial (

εz), torsional shear (

γθz), radial (

εr), and tangential (

εθ)—were derived from direct measurements using Equations (5)–(8) and are presented for different

p levels in

Figure 7a–g.

A consistent kinematic pattern emerges across all stress levels. At low stress ratios (η < 0.5), all strain components increase quasi-linearly and reversibly, dominated by the elastic distortion of the soil–ice composite. As η increases, the strain paths diverge, signaling the onset of dominant, irreversible plastic processes. The torsional shear strain (γθz) undergoes the most pronounced acceleration, unequivocally establishing itself as the primary deformation mode under this specific stress path (α = 30°). This is accompanied by a significant and progressive development of compressive radial strain (εr). In contrast, the axial (εz) and tangential (εθ) strains remain comparatively modest.

This strain trajectory culminates at a critical stress ratio (ηpeak), where a marked kinematic instability occurs. This instability is characterized by a sudden surge in γθz and |εr|, often coinciding with the visual observation of strain localization. We define this inflection point, which corresponds to the peak deviatoric stress, as the ultimate failure state of the specimen.

The deformation at failure is further quantified in

Figure 7h, which plots the magnitude of each strain component at

ηpeak against the mean principal stress. This relationship reveals a critical brittle-to-ductile transition governed by

p: For

p < 4 MPa, failure is characterized by relatively small, localized deformations. The peak

γθz remains below 15%, and the stress–strain response exhibits a post-peak strain-softening regime.

For

p ≥ 4 MPa, a fundamental shift occurs. The specimens sustain progressively larger deformations, with

γθz exceeding 15% without a distinct peak stress, indicative of a continuous strain-hardening response. The radial strain at failure (|

εr|) also increases significantly, pointing towards enhanced dilatancy and particle rearrangement under higher confinement. This transition is not merely a change in magnitude but a shift in the fundamental failure mechanism, which will be corroborated by visual evidence in

Section 3.5.

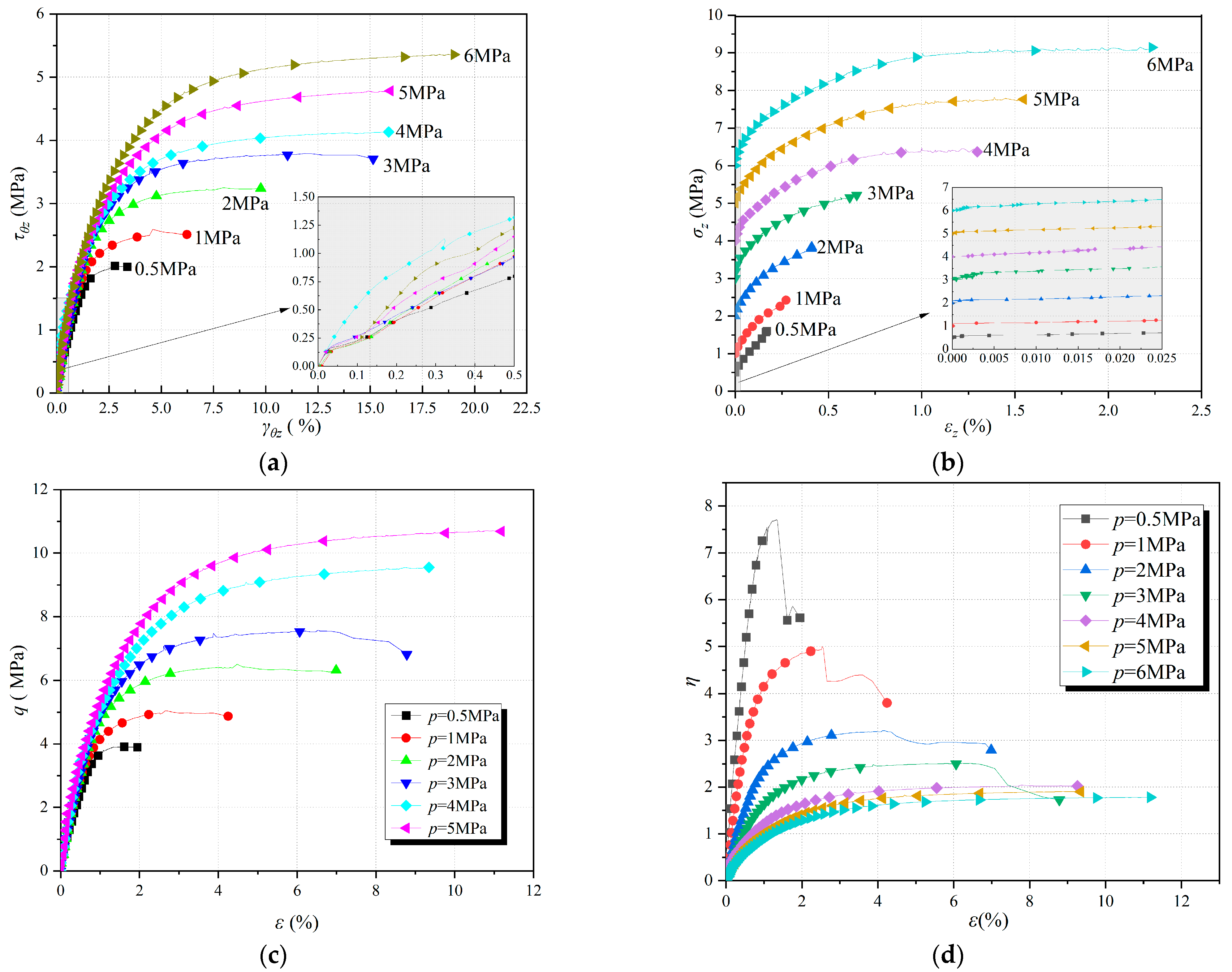

3.3. Stress–Strain Response and Strength Evolution

The component-specific and holistic stress–strain relationships provide critical insights into the deformation and failure mechanisms of pressurized frozen sand, revealing a pronounced dependence on the mean principal stress (p).

Analysis of the axial and torsional shear responses, presented in

Figure 8a,b, demonstrates a clear evolution in mechanical behavior with increasing confinement.

The axial stress–strain curves, depicted in

Figure 8a, undergo a distinct transition with increasing

p. Under low confinements (

p = 0.5, 1 MPa), the relationship remains predominantly linear elastic until failure, indicating that axial deformation is governed by the elastic distortion of the soil–ice matrix with negligible plastic yielding. This suggests robust ice bonding that effectively resists axial compression at low pressures. In contrast, for

p ≥ 2 MPa, the response progresses sequentially through linear elasticity, nonlinear elasticity, and finally, significant plastic deformation. The axial strain at failure increases substantially, by nearly an order of magnitude across the tested pressure range. This evolution reflects a fundamental shift in micromechanical processes: at higher

p, the soil skeleton undergoes extensive particle rearrangement, and the ice matrix likely sustains distributed micro-cracking prior to global failure, facilitating pronounced plastic flow.

The torsional shear stress–strain curves in

Figure 8b, which govern the dominant deformation mode, are particularly revealing. A systematic transition in curve morphology is observed. At low

p (<4 MPa), the response is characterized by a sharp, brittle peak followed by pronounced post-peak strain softening. This behavior signifies the sudden, localized rupture of ice bonds and the initiation of a discrete shear band, leading to a rapid loss of load-bearing capacity. For

p ≥ 4 MPa, the curves transform into a rounded, ductile profile exhibiting sustained strain hardening. This denotes a shift towards a distributed, frictional-flow-dominated deformation mechanism, where strength is mobilized through progressive particle sliding and rolling, augmented by the high confining pressure that suppresses strain localization. The absence of a distinct peak implies that the ice cementation yields in a more plastic manner, integrated with the evolving frictional soil skeleton rather than undergoing catastrophic brittle fracture.

The overall mechanical response is further elucidated by the generalized shear stress (

q) and stress ratio (

η =

q/

p) plotted against the generalized shear strain (

ε) in

Figure 8c,d. The calculation of

ε, verified by comparing two established methodologies (Equations (9)–(11)), showed a maximum discrepancy of less than 0.8%, thereby validating the accuracy of the strain measurements. Equation (11) was consequently adopted for subsequent analysis.

or

Figure 8c confirms a substantial increase in the peak generalized shear stress (

q) with

p, while the corresponding peak strain exhibits the previously identified brittle-to-ductile transition. More profoundly,

Figure 8d illustrates the evolution of the normalized strength, expressed as the stress ratio (

η). Although the initial paths for different

p values diverge at low strains, they demonstrate a marked convergence with increasing deformation. As

p increases, these paths coalesce towards a stable, limiting value. This convergence provides strong evidence that the material is approaching a critical state—a condition characterized by continuous shear deformation under constant shear stress and constant volume. The stable (

η) ratio at high

p defines this critical state stress ratio, a fundamental parameter representing the ultimate frictional capacity of the pressurized frozen sand.

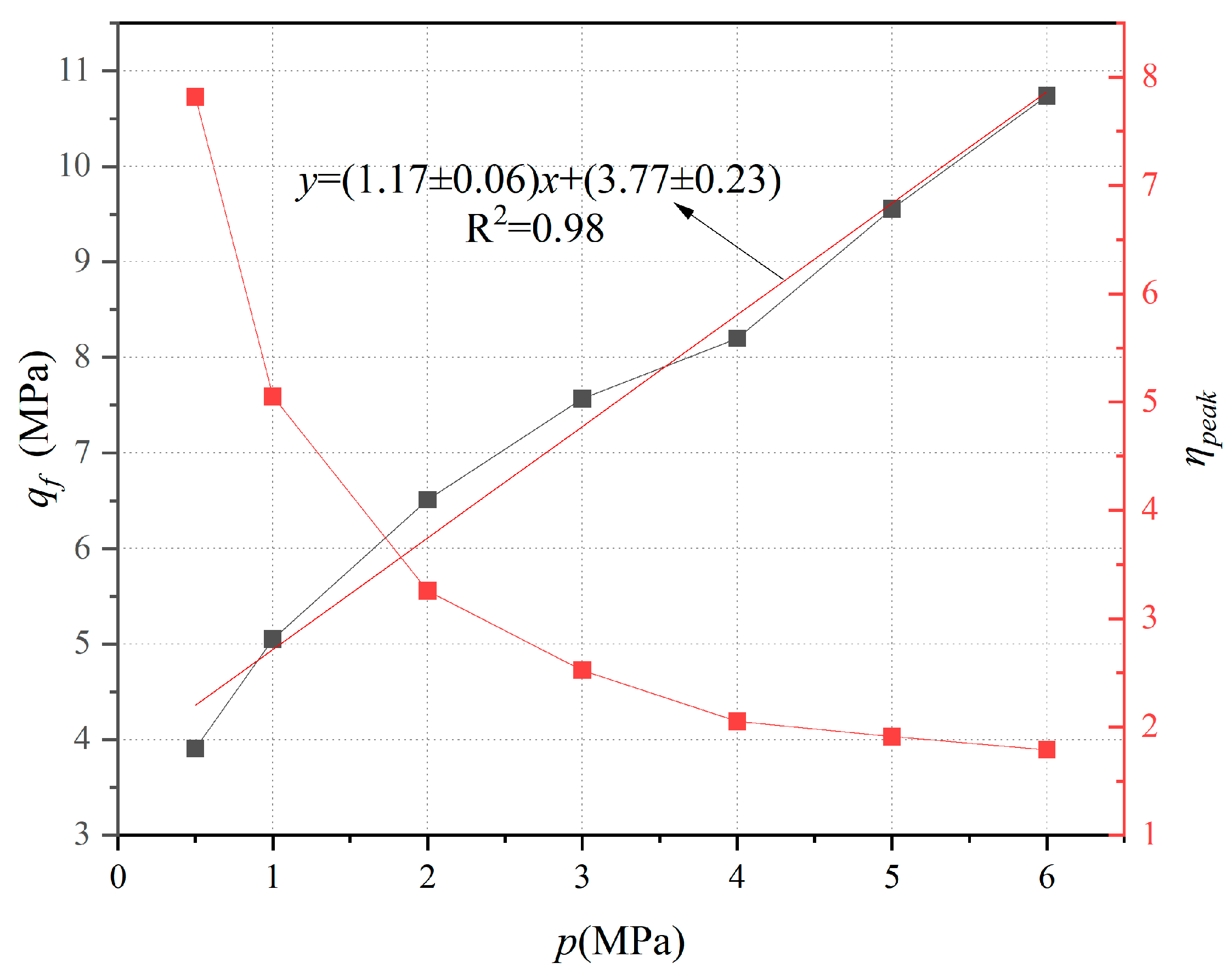

3.4. Strength Characterization and a Proposed Failure Criterion

Synthesis of the peak strength parameters, presented in

Figure 9, enables the establishment of a quantitative failure criterion and underscores a pivotal distinction from the classical behavior of unpressurized frozen soils.

The peak generalized shear stress (

qf) exhibits a remarkably strong linear correlation with the mean principal stress across the entire tested range (0.5–6 MPa). A least-squares regression yields the following failure criterion:

This robust linear equation effectively describes the strength envelope of pressurized frozen saturated medium sand under the tested conditions (T = −10 °C, b = 0.5, α = 30°) in the meridian plane (q-p space). Within this relationship: The slope (M = 1.17) represents the pressure-dependent component of strength, analogous to a coefficient of internal friction, quantifying the enhanced frictional resistance of the soil skeleton under increasing confining pressure. The intercept (cT = 3.77 MPa) signifies the temperature-dependent ice cementation strength, representing the cohesive contribution of the ice matrix, which remains constant at a given temperature and independent of the mean stress within this range.

Conversely, the peak stress ratio (

ηpeak), plotted on the secondary axis of

Figure 9, reveals a different trend. It decreases precipitously at low confinements before asymptotically approaching a stable value of approximately 1.8 for

p ≥ 4 MPa. This convergence corroborates the critical state concept, indicating that while the absolute strength increases indefinitely with

p, the efficiency of the stress ratio attains a frictional limit.

A paramount finding is the conclusive absence of a pressure melting critical point. Throughout the investigated stress range of 0.5–6 MPa, no evidence of the characteristic strength downturn—typically associated with unpressurized frozen soils—is observed. This behavior stands in stark contrast to reports on frozen clay, where a critical mean stress (

p ≈ 4.5 MPa) often initiates pressure melting-induced weakening [

35].

This fundamental divergence is attributed to the unique microstructural state engendered by pressurized freezing. In unpressurized freezing, ice formation occurs without confinement, potentially leading to large, susceptible intergranular ice lenses. During conventional shearing, increasing mean stress can directly load and destabilize this vulnerable ice structure. In our experiments, however, the ice crystallized under persistent confining pressure, likely resulting in a denser, finer-grained, and more integral ice matrix that resists stress-induced phase changes. Furthermore, the constant-p shearing path ensures that the deviatoric stress increment primarily mobilizes frictional resistance, rather than fracturing a pre-existing, unconfined ice fabric. This finding underscores that pressurized freezing generates a metastable soil–ice composite with a fundamentally distinct and more resilient strength response, a critical consideration for the design of deep AGF systems where in situ stresses are substantial.

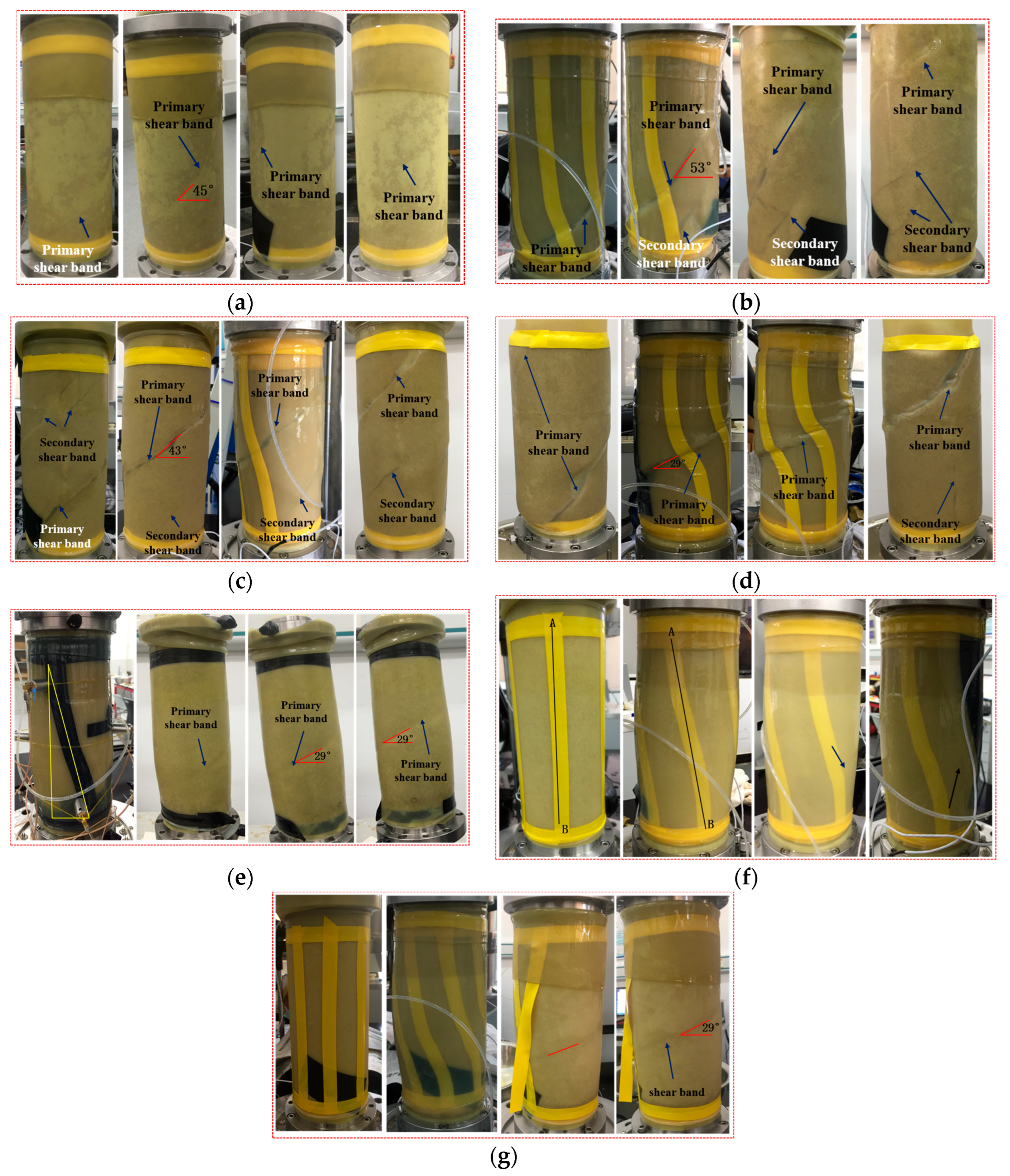

3.5. Failure Mode Transition

The post-failure morphology of the specimens, systematically documented in

Figure 10a–g, provides definitive visual evidence that aligns precisely with the quantified stress–strain responses, offering critical insight into the operative deformation mechanisms in pressurized frozen sand. The observed transition in failure modes reflects a fundamental shift in material behavior governed by the interplay between ice cementation strength and confining pressure, which dictates the competition between localized and homogeneous deformation.

Low-Pressure Regime (

p ≤ 3 MPa): Strain Localization and Brittle Ice Fracture. Within this regime, failure is characterized by the formation of discrete, through-going shear bands (

Figure 10a–d). These features signify the onset of intense strain localization, a process initiated once the material’s capacity for homogeneous deformation is exhausted. The underlying mechanism is the brittle fracture of the ice cementation under low confinement. Macroscopic strength in this regime derives predominantly from ice bonding. As deviatoric stress increases, it eventually surpasses the cohesive and tensile strength of the ice bridges between sand particles, leading to micro-crack nucleation and coalescence along a preferential plane. The low confining pressure provides insufficient normal stress to suppress crack propagation or mobilize significant frictional resistance, thereby permitting the formation and propagation of a persistent shear band. This process is inherently unstable and accounts for the post-peak strain softening observed in the stress–strain curves, wherein the load-bearing capacity diminishes abruptly within the localized zone. The systematic decrease in shear band inclination with increasing

p reflects the growing influence of confining pressure on the internal stress field, which progressively reorients the potential failure plane.

High-Pressure Regime (

p ≥ 4 MPa): Homogeneous Flow and Suppressed Localization. A fundamental transition in failure mechanism occurs for

p ≥ 4 MPa, where no distinct shear bands are observed. Instead, deformation manifests as homogeneous plastic flow, characterized by distributed bulging and torsional deformation of the specimen (

Figure 10e–g). This macroscopic response signifies the effective suppression of strain localization. The elevated mean stress acts through two reinforcing mechanisms: it imposes significant normal stress on potential failure planes, increasing frictional resistance and rendering localized sliding energetically unfavorable; concurrently, it alters the failure mode of the ice matrix itself, promoting ductile yielding via processes such as confined creep and recrystallization, rather than brittle fracture. As a result, the soil–ice composite deforms as a cohesive-frictional continuum, with strength mobilized through pervasive particle rearrangement, frictional sliding, and ductile ice flow. This distributed deformation mechanism is consistent with the observed sustained strain hardening, whereby the material maintains or increases its load-carrying capacity through volumetric compaction and progressive interparticle contact evolution.

This systematic transition—from localized brittle fracture to homogeneous ductile flow—is schematically summarized in

Figure 11.

Figure 11a illustrates the evolution of the three-dimensional principal stress state within the specimen, which underpins the macroscopic failure mode transition. Correspondingly,

Figure 11b depicts the development of the main shear band, showing how its inclination and persistence change with increasing mean principal stress (

p). This analysis establishes

p as a governing parameter controlling deformation stability in frozen soil. The identified threshold at

p ≈ 4 MPa represents a critical shift in material behavior. For the design of engineered frozen structures, maintaining stress states above this threshold ensures a ductile failure mode, thereby enhancing structural resilience and operational safety through progressive deformation rather than abrupt collapse.

4. Discussion

The experimental findings presented in this study reveal fundamental aspects of pressurized frozen sand behavior that challenge conventional understanding derived from unpressurized freezing conditions. This discussion synthesizes these findings to establish mechanistic links between the observed macroscopic responses and their underlying microstructural origins, while highlighting their significance for sustainable geotechnical design.

4.1. Microstructural Basis for the Suppression of Pressure Melting

The linear strength envelope observed in pressurized frozen sand fundamentally diverges from the characteristic strength degradation observed in unpressurized frozen soils beyond a critical mean stress. This divergence is attributed to the distinct microstructural state engineered via pressurized freezing: while the influence of freezing pressure on ice crystal size in soil pores is complex—individual ice crystal size exhibits limited sensitivity to such pressure [

36,

37], and does not consistently induce substantial refinement—the overall ice–soil fabric is profoundly modified. Such modifications encompass alterations to the spatial confinement and stress history of the ice phase, as well as changes to the distribution of ice lenses, the connectivity of pore ice, and the intimacy of grain–ice contacts. In unpressurized freezing, ice forms within unconfined pores; in contrast, pressurized freezing facilitates the formation of a soil–ice composite where ice crystallizes under a pre-existing hydrostatic stress field, thereby forming a pre-compressed, intimately confined, denser, and more integral ice matrix that is closely integrated with the soil skeleton.

In unpressurized freezing, ice forms in unconfined pores, creating a microstructure where ice lenses are susceptible to stress concentrations. During conventional shearing, increasing mean stress can directly induce brittle fracture or pressure melting in this vulnerable ice matrix. In contrast, pressurized freezing produces a soil–ice composite where the ice crystallizes under a pre-existing hydrostatic stress field. This process creates a denser, more integral ice matrix that is pre-compressed and intimately confined by the surrounding soil skeleton. Consequently, during shearing under constant mean stress, the deviatoric loading primarily mobilizes frictional resistance and induces distributed, ductile deformation in the confined ice, rather than triggering catastrophic failure of an unconfined ice structure.

4.2. Micromechanics of the Brittle–Ductile Transition

The transition in failure mode from localized shear bands to homogeneous plastic flow represents a fundamental shift in the dominant deformation mechanism, governed by the interplay between ice cementation and confining pressure.

In the low-pressure regime, the mechanical response is dominated by the ice matrix. The failure process initiates with the brittle fracture of ice bonds at particle contacts, a process facilitated by stress concentrations around non-spherical sand particles (average aspect ratio 1.385). The insufficient confining pressure cannot suppress the propagation of these micro-cracks, allowing them to coalesce into a persistent shear band—a process manifesting macroscopically as strain softening.

In the high-pressure regime, the immense confining pressure fundamentally alters the failure mechanics. It suppresses brittle fracture by both imposing significant normal stress on potential failure planes and forcing the ice to deform through ductile mechanisms such as confined creep. Consequently, the strength becomes governed by the frictional resistance of the soil skeleton, where the non-spherical particles now enhance interlocking and promote distributed deformation. This leads to the observed strain hardening and homogeneous plastic flow, indicative of a stable, frictional-flow-dominated response.

4.3. Engineering Implications and Sustainability Perspectives

The construction industry’s decarbonization requires re-evaluating conventional geotechnical practices through a sustainability lens. While material-focused research dominates sustainable construction literature, ground improvement techniques that reduce permanent material usage offer significant, under-explored potential. AGF represents such an opportunity, but its environmental benefits depend critically on energy efficiency during operation.

The established linear failure criterion (

q = M

p +

cT) provides a critical advancement for the design of Artificial Ground Freezing (AGF) systems. Its simplicity and reliability, stemming from the stable microstructure of pressurized frozen soil, enable a move away from conservative design practices. The clear physical interpretation of its parameters—where M represents the ultimate frictional capacity and

cT the true cohesion from ice cementation—allows for more accurate prediction of frozen wall strength. This precision allows for a move away from conservative design practices, which can potentially lead to optimized refrigeration energy requirements [

16], thereby supporting the reduction in the carbon footprint compared to conventional methods like chemical grouting [

12]. Furthermore, the identification of the ductile transition at

p ≈ 4 MPa provides a design principle for system resilience. Ensuring that frozen walls operate above this stress threshold is likely to promote a ductile failure mode, enhancing safety through progressive deformation rather than catastrophic collapse.

Compared to conventional ground improvement methods such as chemical grouting [

12] or deep soil mixing [

13], which often involve high-embodied-carbon materials and result in permanent environmental alteration, AGF offers a reversible and material-efficient alternative. The findings of this study, which provide a more reliable strength criterion for frozen soil formed under in situ stress conditions, enhance the viability and predictability of AGF. This advancement strengthens the case for adopting AGF as a lower-carbon solution for ground stabilization, particularly in water-rich sandy strata where traditional methods face significant challenges. A quantitative life-cycle assessment to precisely quantify the carbon reduction potential is a recommended direction for future work.

4.4. Limitations and Future Work

While this study provides fundamental insights into the behavior of pressurized frozen sand, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. The investigation was conducted under a specific set of conditions: a single temperature (−10 °C), a fixed stress path (b = 0.5, α = 30°), and focused on a single soil type (saturated medium sand). Furthermore, explicit repeatability tests were not the primary focus of this initial parametric study. These limitations define the scope of the current findings.

Future research should aim to generalize these results by exploring a wider range of temperatures, intermediate principal stress ratios (b-values), and principal stress directions (α). Investigating different soil types (e.g., silts, clays) and incorporating explicit repeatability tests are also crucial next steps. Such work will be instrumental in developing a comprehensive constitutive model that can reliably predict the behavior of artificially frozen ground under the diverse and complex conditions encountered in practice.

5. Conclusions

This study provides systematic insights into the mechanical behavior of pressurized artificially frozen sand, establishing a scientific basis for its application as a sustainable ground stabilization technique in underground construction. The principal conclusions, which connect fundamental mechanics to engineering practice, are outlined as follows:

(1) Pressurized freezing produces a soil–ice composite exhibiting fundamentally distinct mechanical responses compared to unpressurized frozen soils. This is demonstrated by a linear strength increase with mean principal stress (qf = 1.17p + 3.77) and the complete absence of a pressure melting critical point within the 0.5–6 MPa range. This behavioral profile allows for more predictable and reliable strength estimation in design.

(2) A crucial brittle-to-ductile transition occurs at a mean principal stress of approximately 4 MPa. Specimens sheared below this threshold exhibited strain softening and localized shear bands, whereas those above it demonstrated strain hardening and homogeneous plastic flow. This transition provides a design criterion for enhancing the resilience of frozen structures by ensuring ductile, non-catastrophic failure modes.

(3) The proposed linear failure criterion (q = Mp + cT), with M = 1.17 and cT = 3.77 MPa, offers a practical tool for engineering design. These parameters correspond to the ultimate frictional capacity and temperature-dependent ice cementation strength, respectively, facilitating the optimization of AGF systems with the potential for reduced energy consumption and lower carbon emissions.

Collectively, this research delivers experimentally validated parameters and a mechanistic framework that support the optimization of Artificial Ground Freezing. The proposed linear failure criterion is validated for the specific conditions tested; however, future investigations should explore the effects of temperature, diverse stress paths, and varied soil types to further validate and generalize this criterion for a comprehensive constitutive model for sustainable geotechnical design.