Colombian Regulations in the Seismic Design of Reinforced Concrete Buildings with Portal Frames: A Comparative and Bibliometric Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview

1.2. Studies Related to NSR

1.3. National Works (Colombia)

1.4. Aim of This Work

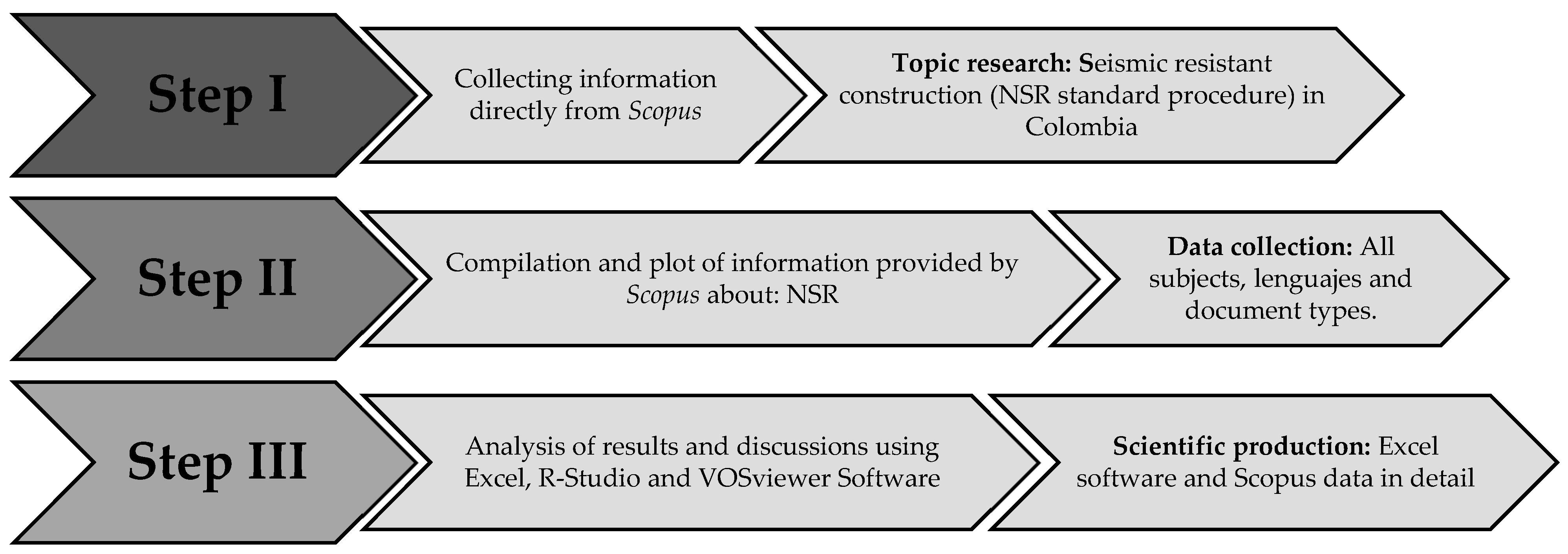

2. Materials and Methods

Bibliometric Analysis (BA)

3. Results and Discussion

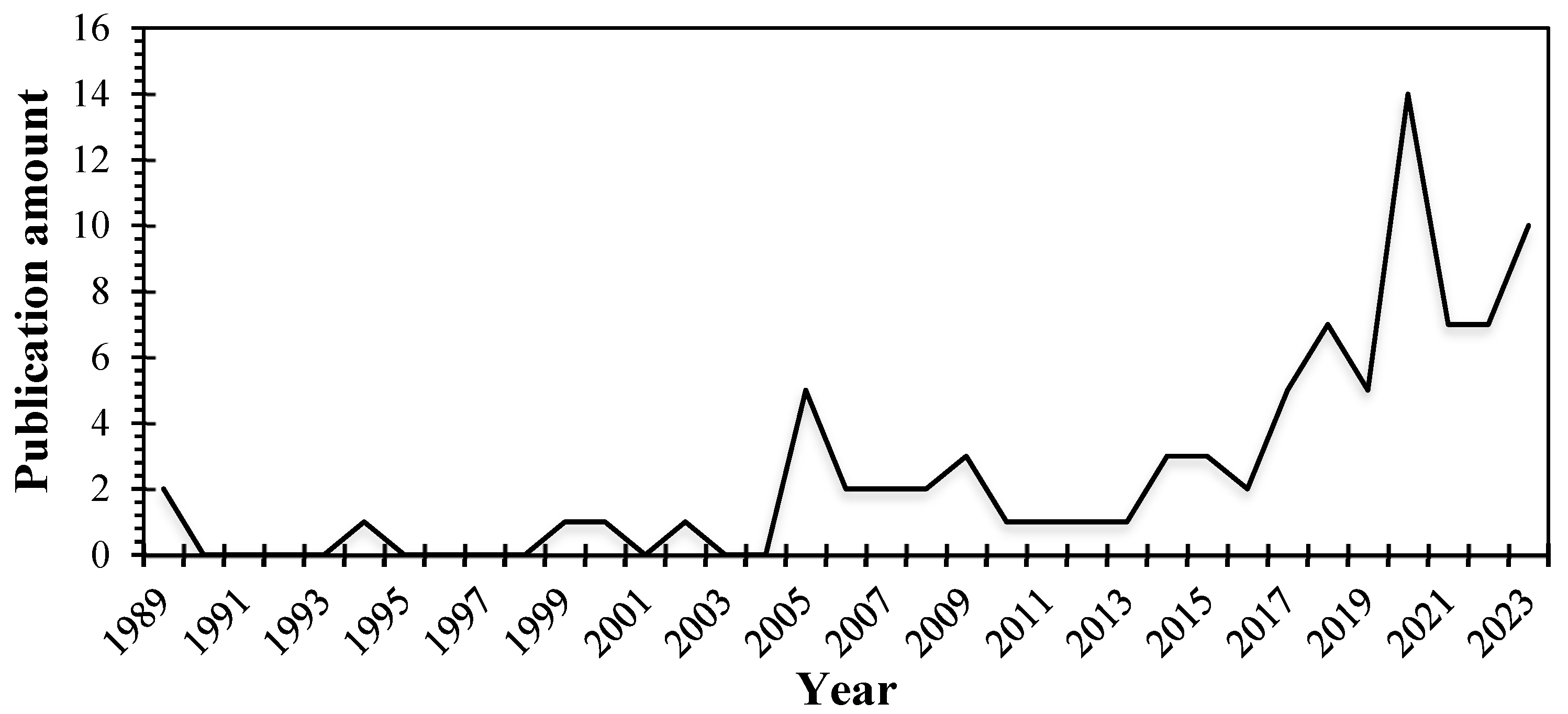

3.1. Data Collection and Information

3.2. Analysis of Results from the Bibliometric Analysis (BA)

3.3. Summary of Publications

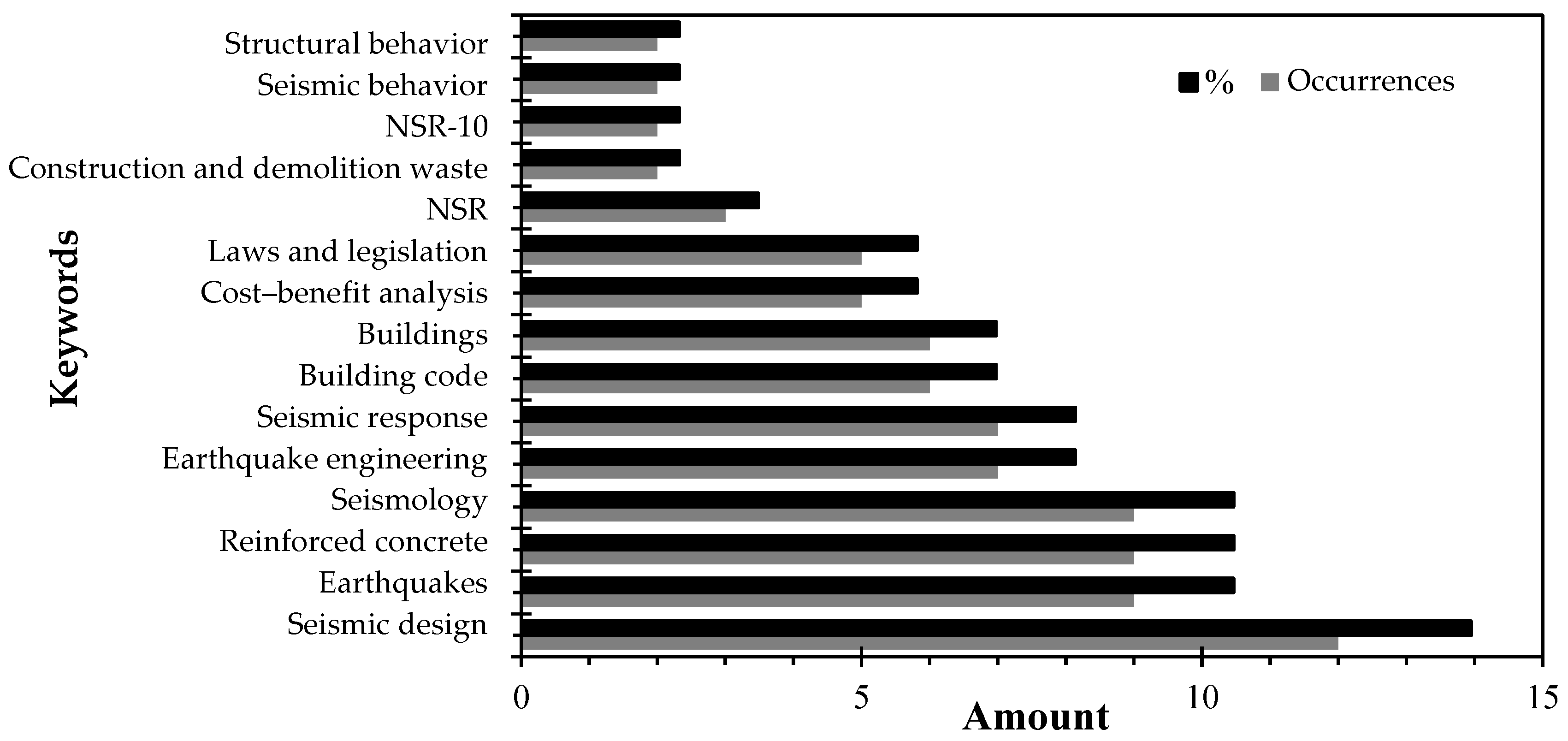

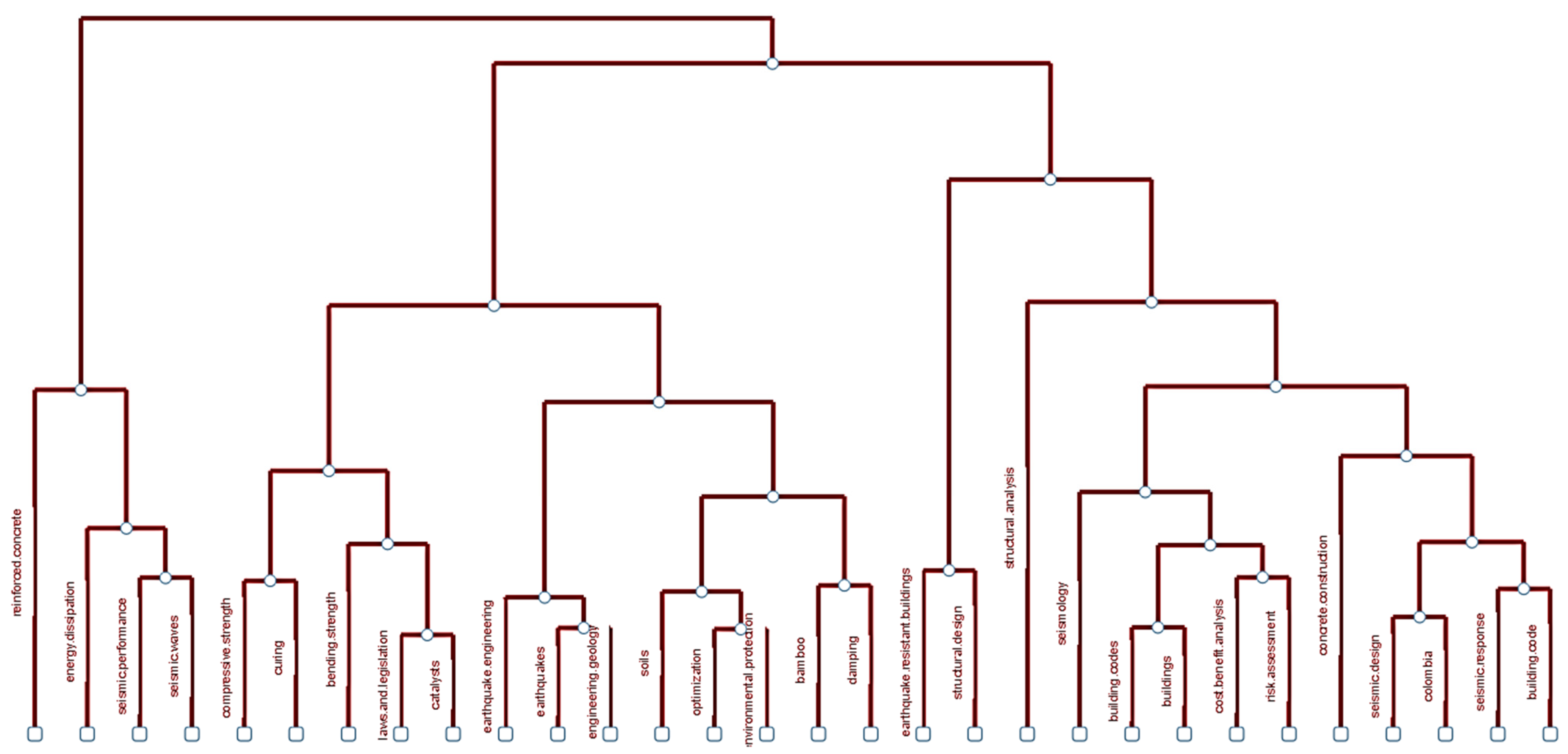

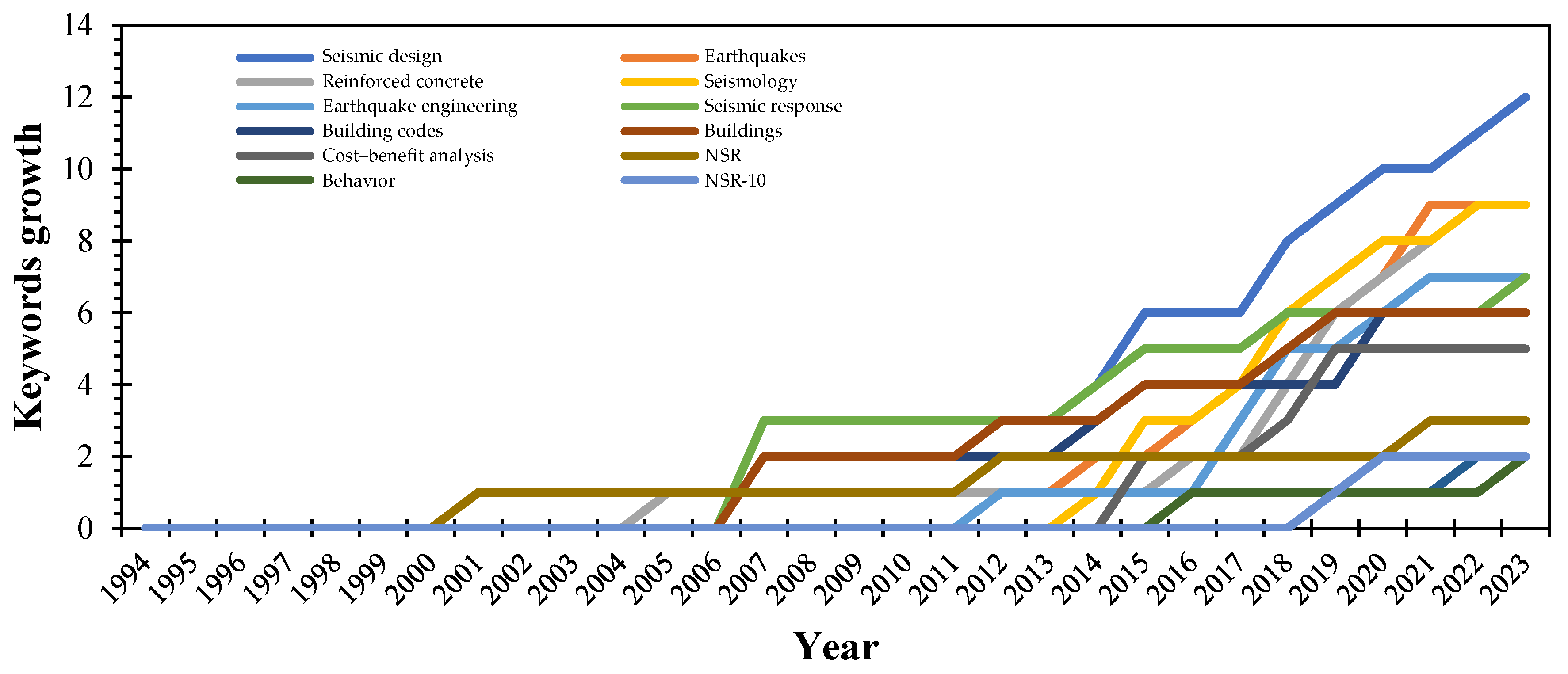

3.4. Evolution of the Use of Keywords over Time

3.5. Importance of Journals

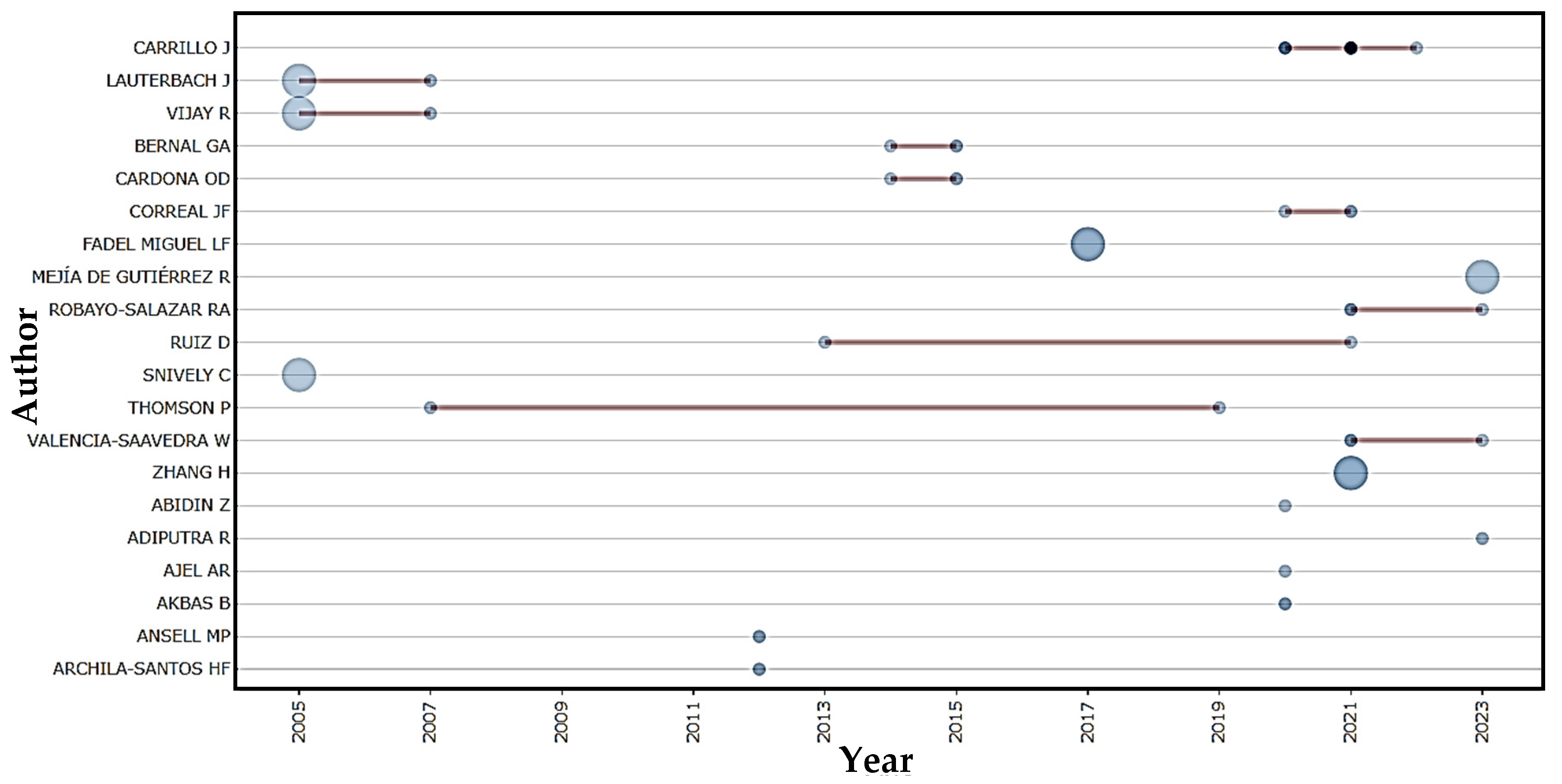

3.6. Relevant Authors

- ➢

- Performance Evaluation of Structures with Reinforced Concrete Columns Retrofitted with Steel Jacketing [20]. This article has been cited 35 times, indicating significant interest in the performance of reinforced concrete structures with retrofitted steel-jacketed columns. This research is crucial for understanding how retrofitting methods can enhance the structural integrity of concrete buildings.

- ➢

- Properties of Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Using Either Industrial or Recycled Fibers from Waste Tires [21]. With 17 citations, this article examines the properties of steel fiber-reinforced concrete using either industrial or recycled fibers derived from waste tires. Research in this area is crucial for enhancing the mechanical properties and sustainability of reinforced concrete, particularly when recycled materials are utilized.

| Article Information | TC | TC by Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lerchie W, 1989, Phys Rep | 156 | 4.33 | [22] |

| Witharana C, 2014, Isprs J Photogramm Remote Sens | 93 | 8.45 | [23] |

| Issa MA, 2016, J Compos Constr | 68 | 7.56 | [24] |

| Cai Z-K, 2018, Constr Build Mater | 48 | 6.86 | [25] |

| Casapu M, 2008, Appl Catal B Environ | 41 | 2.41 | [26] |

| Villar-Salinas S, 2021, J Build Eng | 35 | 8.75 | [20] |

| Shibazaki Y, 2009, Proc Spie Int Soc Opt Eng | 32 | 2 | [27] |

| Li J-R, 2005, Dalton Trans | 32 | 1.6 | [28] |

| Peled A, 2005, Mater Struct | 32 | 1.6 | [29] |

| Kachapi SHH, 2019, Appl Math Model | 22 | 3.67 | [30] |

| Kanert O, 1994, J Non Cryst Solids | 22 | 0.71 | [31] |

| Quintero MAM, 2022, Sustain Struct | 17 | 5.67 | [32] |

| Carrillo J, 2020, Fibers Polym | 17 | 3.4 | [21] |

| Archila-Santos HF, 2012, Key Eng Mat | 17 | 1.31 | [33] |

| Lu P, 2020, J Alloys Compd | 12 | 2.4 | [34] |

| Mora MG, 2015, Earthquake Spectra | 12 | 1.2 | [35] |

| Fiore M, 2017, Leibniz Int Proc Informatics, Lipics | 11 | 1.38 | [36] |

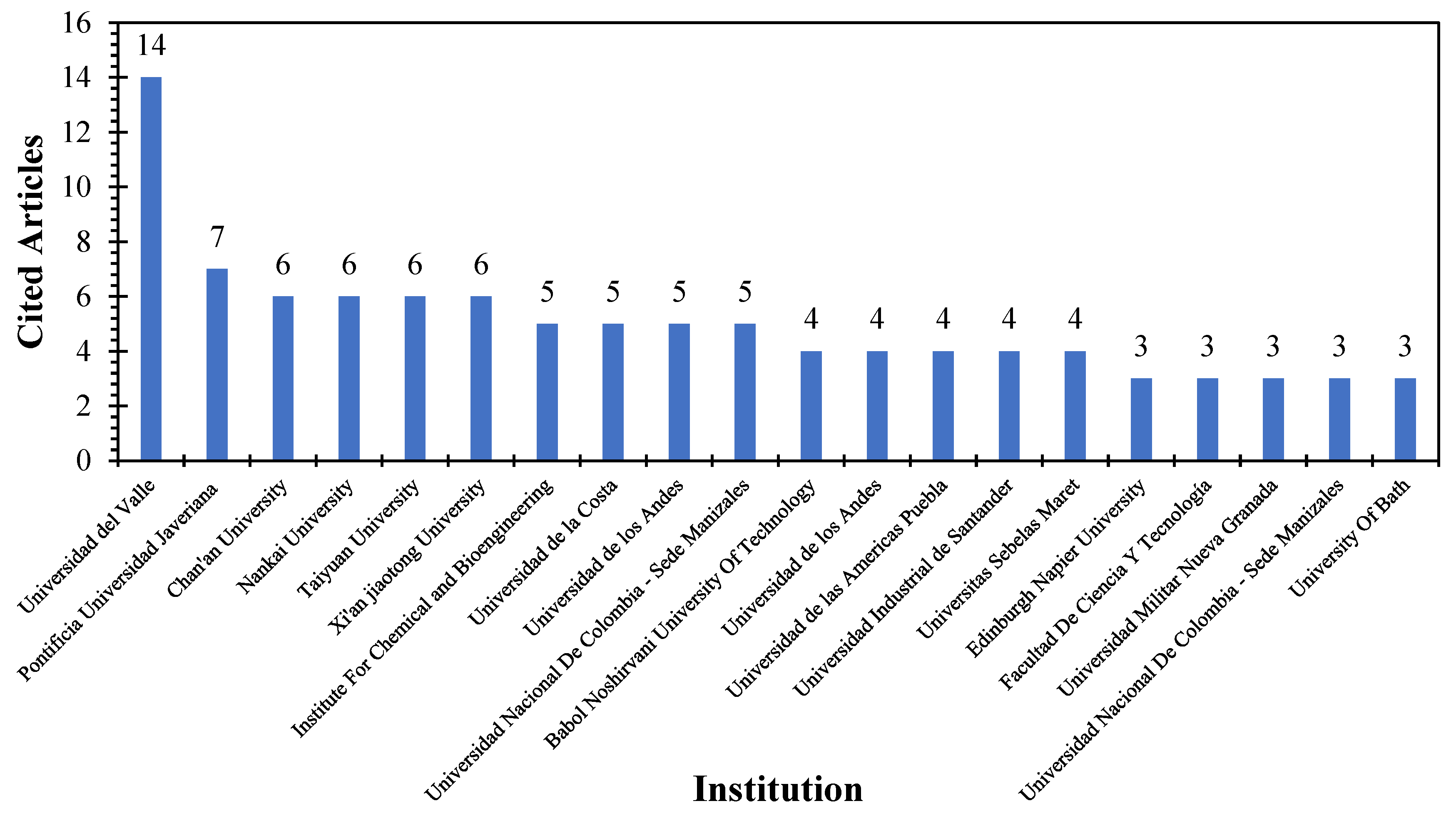

3.7. Most Important Institutions

3.8. Keyword Trends

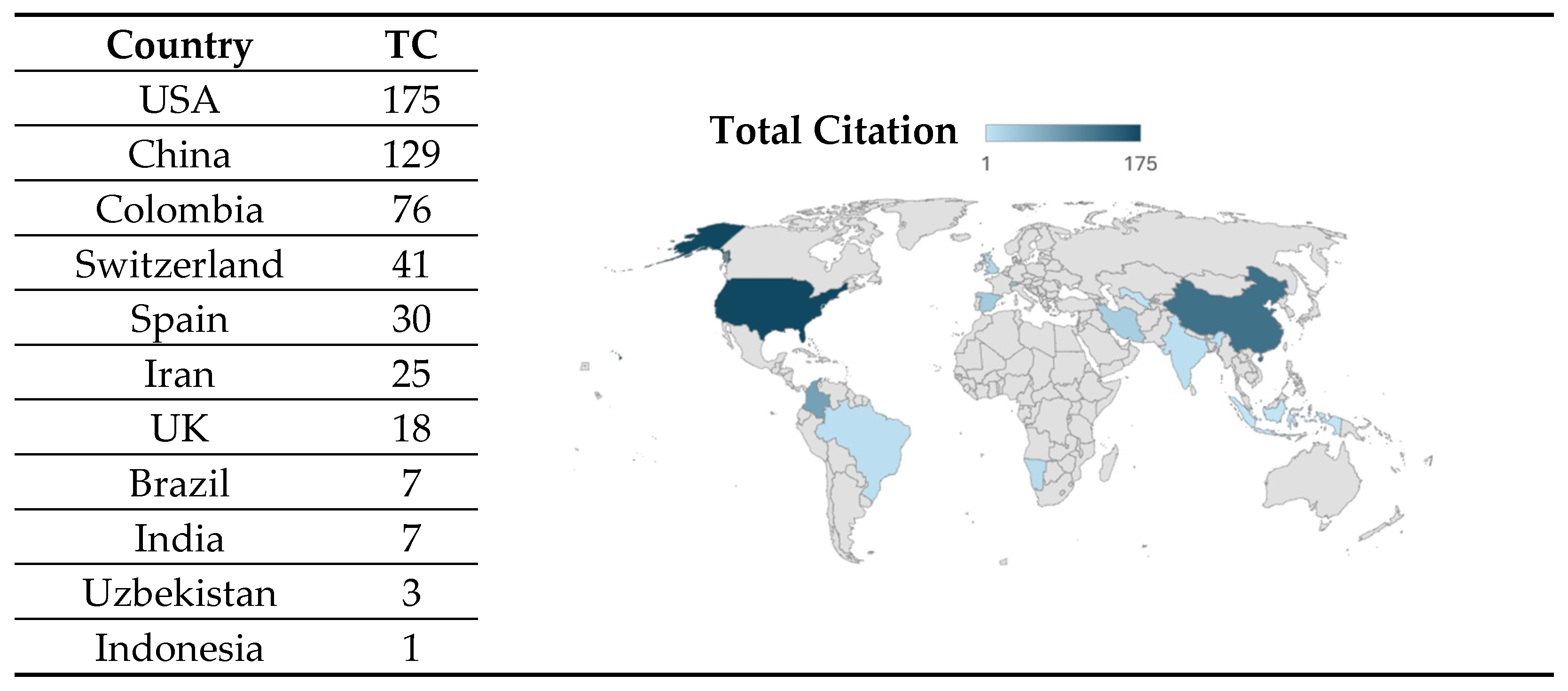

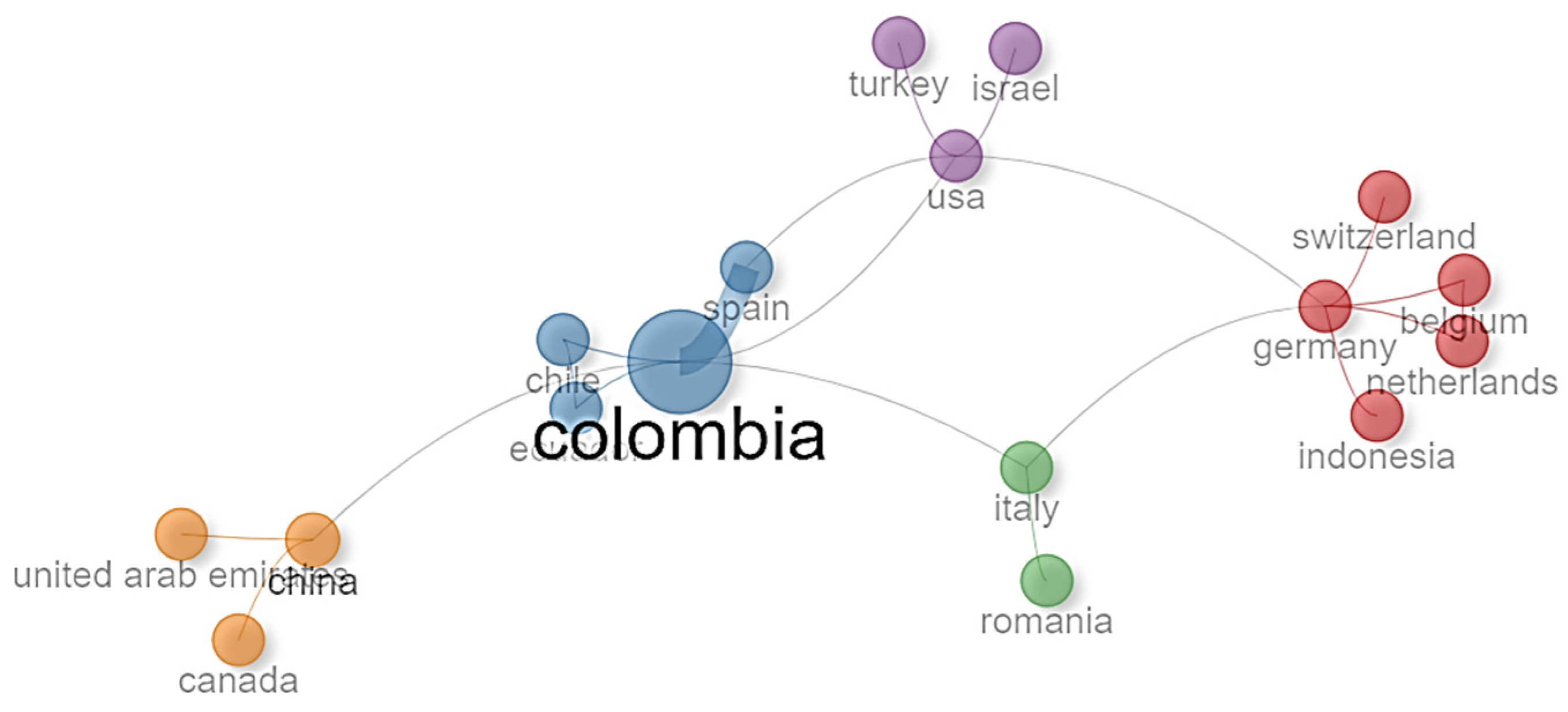

3.9. Collaboration Between Countries

3.10. Correlations Between (Institutions, Authors, and Countries) and (Keywords, Authors, and Journals)

3.11. Comparative Analysis of the Different NSR Standards

- ➢

- Regulatory Evolution: The document examines the evolution of seismic-resistant codes in Colombia, starting with the CCCSR-84, then the NSR-98, and culminating in the most recent NSR-10. Each of these regulations has introduced significant changes in requirements for reinforced concrete design and construction, particularly in seismic-prone areas. This analysis highlights how each code has incorporated advancements in understanding seismic phenomena and improvements in construction techniques, with a particular focus on enhancing the safety and structural resilience of buildings. It also identifies changes in key areas, including architectural and structural design and geotechnical studies. These regulatory changes have had a substantial impact on civil engineering practices in Colombia, fostering the adoption of stricter standards to ensure the safety of buildings.

- ➢

- Design and Construction Procedures: The procedures established by each regulation for designing and constructing buildings are outlined, with a particular emphasis on required geotechnical and architectural studies. Furthermore, the NSR-10 introduces new stages that demand more detailed analysis of soil conditions and structure, reflecting a rigorous approach to assessing seismic risks and structural planning.

- ➢

- Seismic Hazard Zones and Design Movements: The comparison explores how different codes classify seismic hazard zones and define design seismic movements. The NSR-10, for example, presents a more detailed classification, including new categories and coefficients. Changes in seismic zone definitions and the need to consider seismic movements in structural design are also discussed, providing a more robust framework for construction in high-risk zones.

- ➢

- General Seismic-Resistant Design Requirements: The article addresses the classification of structural systems in the codes, identifies key categories, and outlines their seismic-resistant characteristics. It also discusses height limitations for structures based on their structural systems and seismic zones. The NSR-10 modifies and expands these specifications, introducing stricter requirements to improve the ability of structures to withstand seismic events.

- ➢

- Materials and Concrete Quality Analysis: The comparative analysis of regulations on concrete and reinforcement steel focuses on the changes from dosage to mixing and placement procedures. The NSR-10 introduces more rigorous specifications to ensure concrete resistance under various environmental conditions, which is crucial for the durability and safety of buildings in seismic zones.

- ➢

- Foundation Design and Technical Supervision: A comparison of foundation design requirements across different regulations examines methodologies for calculating soil stresses and for designing foundations based on load combinations. The NSR-10 introduces more detailed procedures, including advanced geotechnical analysis to ensure foundation stability and safety across various soil types. Additionally, technical supervision during construction is emphasized as an essential requirement to ensure compliance with design specifications.

- ➢

- Soil-Structure Interaction: Soil–structure interaction is a key aspect of seismic-resistant design discussed in this analysis. Each code addresses this interaction, with the NSR-10 introducing a more detailed classification of soil types and specific criteria for their evaluation. These changes reflect a deeper understanding of how soil characteristics influence structural behavior during seismic events, highlighting the need to adapt structural designs to minimize damage risks.

- ➢

- Structural Analysis Methods: The structural analysis methods used in each code are reviewed, highlighting their evolution. For instance, the NSR-10 introduces more sophisticated calculation methods, such as dynamic analysis and structural modeling, to evaluate how a structure behaves under seismic forces. These methods include response spectrum and modal analysis, enabling a more detailed and accurate understanding of a structure’s seismic response.

- ➢

- Deflection and Drift Control Requirements: Colombian regulations on reinforced concrete structure design specify limits for controlling deflections and drifts, critical aspects for stability and safety during seismic events. This analysis shows how each version of the regulation addresses these controls, with NSR-10 imposing stricter limits to prevent structural collapse and minimize damage, particularly in high-seismic-hazard areas.

- ➢

- Energy Dissipation Systems: The comparison examines the permitted energy dissipation systems under each regulation. The NSR-10 includes detailed requirements for the use of energy-dissipating elements, such as seismic dampers and base isolators, which are crucial for enhancing a structure’s ability to absorb and dissipate seismic energy. The inclusion of these systems reflects the integration of advanced technologies in earthquake-resistant engineering.

- ➢

- Requirements for Critical Structural Elements: The requirements for critical structural elements, such as columns, beams, and connections, are examined. The NSR-10 introduces significant changes, particularly regarding reinforcement and detailing of connections, to improve their performance under seismic loads. These changes are essential for ensuring the structural integrity of key elements during an earthquake.

3.11.1. Evolution of Capacity Design, Confinement Requirements, Local Ductility, and Reinforcement Ratios in Colombian Codes

3.11.2. Evolution of Inspection, Intervention, Retrofit, and Strengthening Requirements in Colombia

3.12. Summarized Standards Analysis

4. Trends and Perspectives

- ➢

- Increased Material Demands: The adoption of the NSR-10 has led to more stringent requirements in material usage. Compared to NSR-98, the NSR-10 mandates a 15–25% increase in concrete volume and reinforcement steel, reflecting a trend toward prioritizing structural resilience in seismic zones.

- ➢

- Focus on Seismic Resilience: Colombian seismic regulations have shifted to incorporate advanced seismic design methods, including modal spectral analysis and pushover analysis. These approaches enhance the precision of structural modeling and improve the ability to withstand seismic forces. This trend aligns with international standards, reflecting the globalization of seismic engineering practices.

- ➢

- Academic Interest and Collaboration: The bibliometric analysis shows consistent annual growth of 4.85% in publications on seismic design. Approximately 75% of these studies focus on reinforced concrete and seismic resistance, while 19.5% involve international collaborations. This indicates a growing global interest in adapting and applying Colombian seismic standards to diverse contexts.

- ➢

- Integration of Local Conditions: The NSR-10 emphasizes soil-structure interaction and includes improved soil classification frameworks that account for Colombia’s unique geotechnical conditions. This aligns with a broader trend of tailoring seismic design to local environmental and geological factors.

- ➢

- Digital Tools in Design and Analysis: The use of advanced software, such as ETABS and RStudio for bibliometric and structural analysis, has become a key component of seismic design. These tools enable engineers to optimize designs and assess seismic performance with greater efficiency and accuracy.

- ➢

- Advanced Retrofitting and Rehabilitation: As Colombia’s infrastructure ages, retrofitting older buildings constructed under outdated codes will be critical. Incorporating modern seismic dissipation technologies, such as base isolators and energy-absorbing devices, can significantly reduce the vulnerability of these structures. This presents an opportunity for research and development in retrofitting technologies tailored to Colombia’s unique structural and economic context.

- ➢

- Sustainability in Construction: Future iterations of the NSR could incorporate guidelines for the use of sustainable materials, such as recycled aggregates and low-carbon concrete, to address environmental concerns while maintaining structural performance. Integrating sustainability into seismic design is becoming increasingly important globally.

- ➢

- Bridging Knowledge Gaps in Rural Areas: Many rural regions in Colombia lack the resources and expertise to implement the NSR-10 fully. Expanding educational programs and providing accessible tools for local engineers and builders can enhance compliance with seismic regulations, thereby reducing vulnerability in underserved areas.

- ➢

- Dynamic Response to Urban Growth: Rapid urbanization in Colombia necessitates adaptive seismic design strategies to accommodate high-density residential and commercial developments. Innovations in modular and prefabricated systems, combined with enhanced seismic resilience, can effectively address these needs.

- ➢

- International Integration and Benchmarking: Strengthening Colombia’s role in global seismic engineering networks is crucial. Benchmarking NSR-10 against international standards, such as Eurocode 8 and ACI 318, can foster greater collaboration, improve code efficacy, and position Colombia as a leader in seismic research and design.

- ➢

- Holistic Risk Mitigation: Beyond structural design, a comprehensive risk mitigation framework encompassing urban planning, emergency preparedness, and community engagement is essential. Such an approach would reduce human and economic losses during seismic events, complementing advancements in engineering.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- ➢

- The evolution of Colombian seismic design regulations, notably the transition from NSR-98 to NSR-10, represents a significant milestone in improving structural safety and resilience. The adoption of NSR-10 led to stricter standards, including a 15–25% increase in the required volumes of concrete and steel to meet updated seismic performance criteria. These changes, coupled with the introduction of new soil classifications and site-specific seismic coefficients, have enhanced design accuracy and reduced the structural vulnerability of buildings in high-risk seismic zones by an estimated 30%.

- ➢

- The bibliometric analysis revealed steady annual growth of 4.85% in academic publications on seismic design regulations from 1989 to 2023, with 75% of studies focusing on structural systems and seismic resistance. Additionally, 19.5% of the analyzed documents highlighted international collaborations, underscoring the global relevance of these regulations. Colombia has emerged as the third most influential country in this field, after the United States and China, with notable contributions from institutions such as Universidad del Valle and researchers such as Carrillo J.

- ➢

- Despite these advancements, significant gaps remain. Many older structures, especially in rural areas, were designed under outdated codes and are highly vulnerable to seismic events. Future efforts should prioritize advanced retrofitting techniques tailored to the local context and the integration of sustainable materials, aligning with global engineering trends.

- ➢

- The Colombian NSR has progressively incorporated more stringent seismic requirements, aligned with modern concepts such as capacity design, improved confinement, explicit ductility categories, and refined detailing provisions. These changes strengthen the overall seismic performance expected from reinforced concrete moment-resisting frame structures. The bibliometric analysis shows a growing academic interest in these regulations, reflected in increased scientific production and thematic consolidation in areas such as ductility, seismic vulnerability, and structural retrofitting. While this study does not quantify the seismic performance gains associated with each code revision, the literature consistently suggests that the increased demands introduced in NSR-10 contribute to the development of more resilient structural systems. Future research may include numerical case studies comparing material quantities, structural behavior, and seismic performance under different NSR versions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CCCSR-84. 1984. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/627094926/c-c-c-s-r-84 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- NSR-98. 1998. Available online: https://curaduriaunoibague.com/documentos/nacional/N-6.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- NSR-10. 2010. Available online: https://www.unisdr.org/campaign/resilientcities/uploads/city/attachments/3871-10684.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Salgado-Gálvez, M.; Bernal, G.; Yamin, L.; Cardona, O. Seismic Hazard Assessment in Colombia. Updates and Usage in the New National Building Code NSR-10. Rev. Ing. 2010, 28–37. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262427631_Seismic_Hazard_Assessment_in_Colombia_Updates_and_Usage_in_the_New_National_Building_Code_NSR-10 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- García, L.E. Desarrollo de la normativa sismo resistente colombiana en los 30 años desde su primera expedición. Rev. Ing. 2014, 71–77. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/276585102_Desarrollo_de_la_Normativa_Sismo_Resistente_Colombiana_en_los_30_anos_desde_su_primera_expedicion (accessed on 25 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Criado-Rodríguez, D.M.; Pacheco-Vergel, W.A.; Afanador-García, N. Vulnerabilidad sísmica de centros poblados: Estudio de caso. Rev. Ingenio 2020, 17, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amariles López, C.; Ramírez-Sepúlveda, D.; Cano-Saldaña, L. Comparación entre el ACI-318-19 y la NSR-10 para diseño estructural de pórticos de concreto en zonas de amenaza sísmica alta: Comparison between ACI-318-19 and NSR-10 for structural design of concrete frames in high seismic hazard zones. Cienc. E Ing. Neogranadina 2022, 32, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Paal, S.G. Artificial intelligence-enhanced seismic response prediction of reinforced concrete frames. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 52, 101568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, P.C.; Kavvadias, I.E.; Demertzis, K.; Iliadis, L.; Vasiliadis, L.K. Structural Damage Prediction of a Reinforced Concrete Frame under Single and Multiple Seismic Events Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahumada Mastrodoménico, A.M. Análisis Comparativo del Diseño para una Edificación de 5 Niveles, según las Normas Colombianas de Sismoresistencia NSR-98 y la NSR-10, en zona de Amenaza Sísmica Intermedia. Available online: https://repositorio.cuc.edu.co/entities/publication/97ea5c21-a366-42d0-9a68-07ef2b38199b (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Alvarado Perez, E.E.; Bustos Linares, B.; Quintero Rojas, C. Análisis de Vulnerabilidad Sísmica Estructural caso Asentamiento Subnormal Barrio Hacienda Los Molinos Localidad Rafael Uribe Uribe de Bogotá D.C. 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11396/3480 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Aranda-Nieves, S.; Díaz-Portilla, M. Comparación Técnica Entre el Reglamento Colombiano de Construcción Sismo Resistente NSR-98 y el Reglamento Colombiano de Construcción Sismo Resistente NRS-10 en Edificaciones en la Ciudad de Bogotá. 2017. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10983/15218 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Acosta Rodríguez, D.L. Análisis Estructural con ETABS, Aplicando Reglamento Colombiano de Construcción Sismo Resistente (NSR-10). 2016. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11634/2677 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- García-León, R.A.; Martínez-Trinidad, J.; Campos-Silva, I. Historical Review on the Boriding Process using Bibliometric Analysis. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2021, 74, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguillo, I.F. Is Google Scholar useful for bibliometrics? A webometric analysis. Scientometrics 2012, 91, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-León, R.A.; Afanador-García, N.; Guerrero-Gómez, G. A Scientometric Review on Tribocorrosion in Hard Coatings. J. Bio-Tribo-Corros. 2023, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, H.Y.; Vasco-Echeverri, O.H.; Moreno-Pacheco, L.A.; García-León, R.A. Biomaterials in Concrete for Engineering Applications: A Bibliometric Review. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, H.Y.; Vasco-Echeverri, O.; López-Barrios, R.; García-León, R.A. Optimization of Bio-Brick Composition Using Agricultural Waste: Mechanical Properties and Sustainable Applications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Salinas, S.; Guzmán, A.; Carrillo, J. Performance evaluation of structures with reinforced concrete columns retrofitted with steel jacketing. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 33, 101510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, J.; Lizarazo-Marriaga, J.; Lamus, F. Properties of Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Using Either Industrial or Recycled Fibers from Waste Tires. Fibers Polym. 2020, 21, 2055–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerchie, W.; Schellekens, A.N.; Warner, N.P. Lattices and strings. Phys. Rep. 1989, 177, 1–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witharana, C.; Civco, D.L.; Meyer, T.H. Evaluation of data fusion and image segmentation in earth observation based rapid mapping workflows. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 87, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, M.A.; Thilan, O.; Mustapha, I. Shear Behavior of Basalt Fiber Reinforced Concrete Beams with and without Basalt FRP Stirrups. J. Compos. Constr. 2016, 20, 4015083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.-K.; Wang, Z.; Yang, T.Y. Experimental testing and modeling of precast segmental bridge columns with hybrid normal- and high-strength steel rebars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 166, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casapu, M.; Grunwaldt, J.-D.; Maciejewski, M.; Krumeich, F.; Baiker, A.; Wittrock, M.; Eckhoff, S. Comparative study of structural properties and NOx storage-reduction behavior of Pt/Ba/CeO2 and Pt/Ba/Al2O3. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2008, 78, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibazaki, Y.; Kohno, H.; Hamatani, M. An innovative platform for high-throughput high-accuracy lithography using a single wafer stage. Proc. SPIE 2009, 7274, 72741I. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-R.; Bu, X.-H.; Jiao, J.; Du, W.-P.; Xu, X.-H.; Zhang, R.-H. Novel dithioether–silver(i) coordination architectures: Structural diversities by varying the spacers and terminal groups of ligands. Dalt. Trans. 2005, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, A.; Jones, J.; Shah, S.P. Effect of matrix modification on durability of glass fiber reinforced cement composites. Mater. Struct. 2005, 38, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachapi, S.H.H.; Dardel, M.; Daniali, H.M.; Fathi, A. Nonlinear dynamics and stability analysis of piezo-visco medium nanoshell resonator with electrostatic and harmonic actuation. Appl. Math. Model. 2019, 75, 279–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küchler, R.; Kanert, O.; Fricke, M.; Jain, H.; Ngai, K.L. Study of nuclear spin relaxation in CLAP glasses. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 1994, 172–174, 1373–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A. Structural analysis of a Guadua bamboo bridge in Colombia. Sustain. Struct. 2022, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archila-Santos, H.F.; Ansell, M.P.; Walker, P. Low Carbon Construction Using Guadua Bamboo in Colombia. Key Eng. Mater. 2012, 517, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Luo, X.; Yang, Y.; Le, W.; Huang, B.; Li, P. Co-free non-equilibrium medium-entropy alloy with outstanding tensile properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 833, 155074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, M.G.; Valcárcel, J.A.; Cardona, O.D.; Pujades, L.G.; Barbat, A.H.; Bernal, G.A. Prioritizing Interventions to Reduce Seismic Vulnerability in School Facilities in Colombia. Earthq. Spectra 2015, 31, 2535–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M.; Saville, P. List Objects with Algebraic Structure. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Formal Structures for Computation and Deduction, Oxford, UK, 3–9 September 2017; Schloss Dagstuhl-Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik: Dagstuhl, Germany, 2017; pp. 16:1–16:18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julián, C. Analysis of the Earthquake-Resistant Design Approach for Buildings in Mexico. Ing. Investig. Tecnol. 2014, 15, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qian, S.; Zhang, Q.; Li, L. Advanced Concrete Technology and Its Structural Applications. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 9781273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEMA-P695. Quantification of Building Seismic Performance Factors. FEMA: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2009. Available online: https://nehrpsearch.nist.gov/static/files/FEMA/fema_p695.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Santana, G.; Committee, A.C.I. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318-19) and Commentary; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevallos-Velásquez, O.A.; Guerra-Valladares, M.D.; Marcillo-Zapata, C.A.; Quinatoa-Martínez, J.G. Evolución histórica de las normativas de diseño sismo resistente en América Latina. Casos de estudio: Colombia, Ecuador, Perú, Chile. Rev. Científica INGENIAR Ing. Tecnol. Investig. 2024, 7, 2–25. [Google Scholar]

| Description | Results |

|---|---|

| Main Information | |

| Time Span | 1989:2023 |

| Sources | 75 |

| Documents | 87 |

| Average Document Age | 8.49 |

| Average Citations per Document | 9.276 |

| Document Content | |

| Keywords | 852 |

| Author’s Keywords | 294 |

| Authors | 277 |

| Single Author Documents | 6 |

| Co-authorship | |

| Single Author Documents | 6 |

| Co-authors per Document | 3.38 |

| % of International Co-authorship | 19.54 |

| Document Types | |

| Articles | 54 |

| Book Chapters | 1 |

| Section Documents | 30 |

| Reviews | 2 |

| No | Journal | h_Index | TC | NP | Publication Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Construction And Building Materials | 2 | 53 | 2 | 2018 |

| 2 | Earthquake Spectra | 2 | 19 | 2 | 2015 |

| 3 | Materials And Structures/Materiaux Et Constructions | 2 | 43 | 2 | 2005 |

| 4 | Advances In Intelligent Systems and Computing | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2021 |

| 5 | American Concrete Institute, Aci Special Publication | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2000 |

| 6 | Applied Catalysis B: Environmental | 1 | 41 | 1 | 2008 |

| 7 | Applied Mathematical Modelling | 1 | 22 | 1 | 2019 |

| 8 | Applied Physics A: Materials Science and Processing | 1 | 7 | 1 | 2020 |

| 9 | ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Proceedings (IMECE) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1999 |

| 10 | Bulletin Of Earthquake Engineering | 1 | 7 | 1 | 2020 |

| 11 | Case Studies in Construction Materials | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2018 |

| 12 | Catalysis Today | 1 | 30 | 1 | 2011 |

| 13 | Classical And Quantum Gravity | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1989 |

| 14 | Compdyn 2017—Proceedings of the 6th International Conference On Computational Methods In Structural Dynamics And Earthquake Engineering | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2017 |

| 15 | Dalton Transactions | 1 | 32 | 1 | 2005 |

| 16 | Dyna (Colombia) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2018 |

| 17 | Em: Air and Waste Management Association’s Magazine for Environmental Managers | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2002 |

| 18 | Energy Procedia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2015 |

| 19 | Energy Reports | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2023 |

| 20 | Engineering Structures | 1 | 6 | 1 | 2007 |

| Author | Year | h_Index | TC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carrillo J | 2021 | 1 | 35 |

| Ansell MP | 2012 | 1 | 17 |

| Archila-Santos HF | 2012 | 1 | 17 |

| Carrillo J | 2020 | 1 | 17 |

| Fadel Miguel LF | 2017 | 2 | 14 |

| Bernal GA | 2015 | 1 | 12 |

| Cardona OD | 2015 | 1 | 12 |

| Robayo-Salazar RA | 2021 | 1 | 8 |

| Valencia-Saavedra W | 2021 | 1 | 8 |

| Zhang H | 2021 | 2 | 8 |

| Akbas B | 2020 | 1 | 7 |

| Lauterbach J | 2007 | 1 | 6 |

| Thomson P | 2007 | 1 | 6 |

| Vijay R | 2007 | 1 | 6 |

| Correal Jf | 2021 | 1 | 5 |

| Adiputra R | 2023 | 1 | 1 |

| Ajel AR | 2020 | 1 | 1 |

| Correal JF | 2020 | 1 | 1 |

| Mejía De Gutiérrez R | 2023 | 2 | 1 |

| Ruiz D | 2013 | 1 | 1 |

| Thomson P | 2019 | 1 | 1 |

| Title A | Building Design and Construction Procedure | Seismic Hazard Zones and Design Seismic Movements | General Earthquake-Resistant Design Requirements | Drift Requirements | Soil-Structure Interaction | |

|

|

|

|

| ||

| Title C | Materials | Concrete quality, mixing, and placing | Formwork, embeddings, and construction joints | Reinforcement details | Analysis and design—requirements general | Strength requirements and operation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Parameter | CCCSR-84 | NSR-98 | NSR-10 | Future Developments/International Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design Philosophy | Working-stress design; limited seismic ductility considerations. | Adoption of LRFD; explicit ultimate limit states. | Consolidated capacity design (hierarchy of strengths). | Integration of updated hazard maps, resilience-oriented performance, and performance-based design (PBD). |

| Force Reduction/Behavior Factor (R) | Concept not fully formalized; implicit reductions. | Introduction of system-dependent R values. | Revised R values based on ductility categories and system behavior. | Calibration of R factors using nonlinear dynamic analyses and PSHA-based targeting. |

| Ductility Categories | Not defined. | Implicit moderate ductility. | Explicit categories: DES (high), DMO (moderate), DBA (low). | Refinement of ductility levels and detailing requirements following FEMA P-2082 and Eurocode 8. |

| Capacity Design Requirements | No requirement for Mc > Mb. | Initial conceptual introduction. | Full enforcement: ΣM_cap,column ≥ 1.2 ΣM_cap,beam at joints. | More explicit hierarchy verification, joint robustness checks, and deformation-based criteria. |

| Drift Limits | No explicit drift checks: serviceability-based. | Introduces maximum drift limits (elastic drift checks). | Drift limited based on ductility and occupancy; explicit Δ/h criteria. | Nonlinear drift limits, residual drift criteria, and functional recovery considerations. |

| Shear Design Expressions | V_n based on simplified nominal strength without cyclic effects. | Strength-based shear using φV_n; includes seismic amplification. | Shear demand tied to flexural overstrength (capacity design). | Models accounting for cyclic degradation and shear-flexure interaction. |

| Confinement & Transverse Reinforcement | Minimal confinement; no hinge detailing. | Basic transverse reinforcement for seismic zones. | Explicit confinement in hinge regions, joint cores, and plastic zones (s, A_sh, ρ_s). | Stricter transverse reinforcement spacing and confinement rules aligned with ACI 318-19. |

| Minimum Longitudinal Steel (ρ_min) | Basic prescriptive minimums. | Increased ρ_min for seismic elements. | Adjusted ρ_min based on axial load ratio and ductility category. | Updated ρmin and ρmax based on strain limits, buckling mitigation, and high-ductility requirements. |

| Joint Shear & Anchorage | Not explicitly addressed. | Initial consideration of anchorage in beam-column joints. | Detailed joint shear checks; anchorage length functions of f_y and bar diameter. | Enhanced joint shear models and confinement requirements. |

| Soil Classification | Basic soil types A, B, C. | Expanded classifications with amplification factors. | Introduction of Vs30-based categories; improved amplification rules. | More refined site-specific amplification from updated PSHA databases. |

| Spectral Shape | Simplified elastic spectrum. | Two-branch spectrum introduced. | Multi-branch spectrum with plateau and corner periods. | Region-specific spectral shapes based on updated seismic hazard models. |

| Seismic Coefficients (Aa, Av) | Uniform coefficients nationwide. | Regional coefficients and zonation maps. | Refined zonation; soil-dependent coefficients. | Integration of state-of-the-art national PSHA with spatially varying hazard levels. |

| Existing Structures | Not included. | Basic evaluation criteria. | Structured procedures referencing modern assessment guidelines. | Strengthening/retrofit provisions aligned with ASCE 41-23 and modern assessment guidelines. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-León, R.A.; Navarro-Barrera, C.J.; Afanador-García, N. Colombian Regulations in the Seismic Design of Reinforced Concrete Buildings with Portal Frames: A Comparative and Bibliometric Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 4303. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234303

García-León RA, Navarro-Barrera CJ, Afanador-García N. Colombian Regulations in the Seismic Design of Reinforced Concrete Buildings with Portal Frames: A Comparative and Bibliometric Analysis. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4303. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234303

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-León, Ricardo Andrés, Carlos Josué Navarro-Barrera, and Nelson Afanador-García. 2025. "Colombian Regulations in the Seismic Design of Reinforced Concrete Buildings with Portal Frames: A Comparative and Bibliometric Analysis" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4303. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234303

APA StyleGarcía-León, R. A., Navarro-Barrera, C. J., & Afanador-García, N. (2025). Colombian Regulations in the Seismic Design of Reinforced Concrete Buildings with Portal Frames: A Comparative and Bibliometric Analysis. Buildings, 15(23), 4303. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234303