Abstract

This study, conducted with a rigorous statistical analysis, aims to assess the applicability of current analytical models in predicting the likelihood of splitting in precast concrete tunnel segments during the thrust phase of tunnel boring. Five analytical models were analyzed and compared to experimental results. The accuracy and precision of the models in predicting the splitting load were evaluated. The study revealed that the prediction accuracy of the models can be affected by various factors, such as the size and geometry of the test specimens and the type of test configuration used. An adjustment to the analytical models with the best performance is proposed to correct for statistical bias and enhance the predictions to address this issue. These findings are significant for the construction industry, as improved cracking control can reduce repair costs. Furthermore, enhancing the predictability of analytical models can improve the safety and reliability of precast concrete tunnel segments during tunnel boring.

1. Introduction

Underground transportation systems have gained notorious importance in recent decades due to increased urban mobility problems. Investment in subway systems is one of the main alternatives to soften mobility issues and reduce social inequality in highly populated suburban areas [,]. In this sense, tunnel boring machine (TBM) technology is a viable option for the construction of long tunnels subjected to harsh geological and hydrological conditions [,]. The construction process consists of the excavation and assembly of precast concrete segments to produce the tunnel lining structure. During the thrust phase, the installed ring works as a reaction frame that receives the load applied by the TBM hydraulic jacks to advance the excavation front, which may result in considerable damage to the segments [].

During the construction, the major segment damages are cracks in the longitudinal direction of the tunnel and chipping of the segment corner. The latter results from contact deficiency on longitudinal joints and/or mishandling during installation []. In addition, the longitudinal cracks are related to the high compression loads applied by the thrust jacks [], the support conditions of the segments [] and loading conditions, such as jacks’ configurations and eccentricity [].

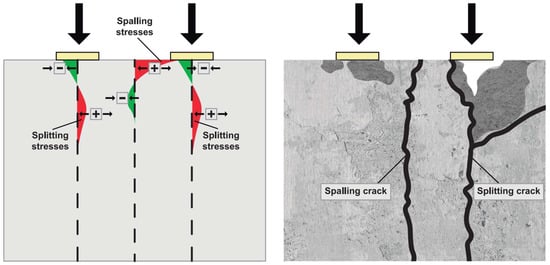

The results in the literature show that the variety of segment configurations leads to different stress distributions and, consequently, different cracking patterns. Concerning this aspect, the fib Bulletin 83 [] proposes two different levels of investigation for the TBM thrust phase: local and global segment behavior. The first one corresponds to stress concentrations under or between the actuators. At the same time, the second is generally focused on evaluating the distribution of stresses throughout the middle plane of the segments and strictly depends on the boundary conditions imposed. For local segment behavior, two types of cracking can occur: splitting (or bursting) and spalling cracks. The splitting is located under the loading shoes, and the spalling is characterized by its location between the jacks, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Splitting and spalling stresses in a concrete block (adapted from Conforti et al. []).

In reinforced concrete design, the structure is typically analyzed by considering two distinct regions []. One region follows the Bernoulli-Euler kinematic hypotheses, while the other adheres to the principle of Saint-Venant. When analyzing the splitting phenomena, the stress distribution is not homogeneous immediately under the jacks, which depends on the concentrated loads, support conditions and geometrical discontinuities []. This region with non-homogeneous stress distribution, also known as the “D region” [,,] is a disturbed area with approximately the specimen’s base length. For regions beyond the disturbed area, Bernoulli’s hypothesis validates a linear strain distribution along the cross-section, and the stress distribution is considered homogeneous [,].

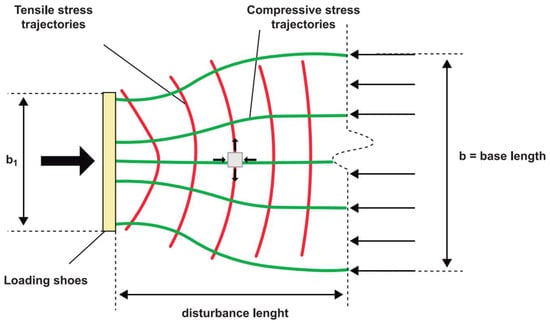

Figure 2 illustrates the stress state in the “D region” under the loading shoes. In this sense, the stress pattern near the supports of the segments depends on the relation between segment width and height, and two scenarios can occur: (1) when there is enough length to spread the compressive stresses to a uniform distribution (sufficient length), and (2) when there is not enough length to spread the stresses (insufficient length) [].

Figure 2.

Stress state in the “D region” under the loading shoe.

Given the importance of the topic, several analytical models based on two-dimensional elasticity theory, concrete plasticity theory, and strut-and-ties method have been proposed to predict splitting in concrete segments subjected to concentrated forces [,,,,,,]. In these models, the splitting load is taken as the necessary force to initiate the splitting cracks process in the elements. Moreover, several small-scale and full-scale experimental campaigns are available in the literature, focused on evaluating the occurrence of splitting in concrete segments [,,,,,,]. However, no published study addresses the integrated analysis of these different analytical models, and experimental validation is focused on verifying their applicability to segments used in TBM tunnel production.

Existing analytical formulations—such as classical strut-and-tie and elastic-based solutions—were primarily developed for prestressed anchorage zones or linear support conditions, where load transfer occurs through relatively uniform stress fields. Under TBM thrust, however, concentrated jack loads, localized confinement, and evolving boundary stiffness induce nonlinear stress redistributions not captured by traditional models. Therefore, an integrated and comparative assessment of available analytical solutions is needed to evaluate their predictive limitations and adapt them appropriately to TBM-driven tunnel segments.

In this context, this study aimed to assess the applicability of analytical models in predicting the splitting of TBM segments during the thrust phase. A statistical approach was employed, and the experimental results available in the literature were used to compare these models.

2. Background

This section presents a literature review of the analytical models proposed for splitting phenomena. Moreover, a brief literature review on experimental campaigns considering several concrete blocks and precast segments under concentrated loads is presented. These results are essential support for the integrated analysis conducted in this paper.

2.1. Analytical Models Available in the Literature

Several analytical models to predict splitting for TBM tunnels or prestressed concrete beams can be found in the literature [,,,,,,], as listed in Table 1. Each of the analytical models has different approaches to considering the splitting behavior. In the case of prestressed concrete, some analytical models deal with bursting forces (P), which are considered the force necessary to initiate cracking due to the splitting, developed perpendicularly to the loading direction. In these cases, the term ‘bursting force’ is synonymous with ‘splitting crack’. In other cases, the predicted splitting strength (Fpred) is calculated analytically based on the tensile strength of the matrix (ft). Overall, the strut-and-tie model is one of the approaches commonly used for designing conventional reinforcement for splitting.

Table 1.

Summary of the analytical models found in the literature.

Morsch developed one of the first models proposed in the literature [], in which the compressive stress trajectories are simplified in a symmetric bilinear stress path. From the applied load node, an oblique strut is designed to consider an approximation of the angle performed by the compressive stress trajectory. Inversely, the tie is in the center of the disturbance length, where a resultant bursting force is located. Considering the equilibrium condition, an analytical equation for the force (Z) is obtained as a function of the applied load (P), the length in which the load is applied (b1), the total specimen length (b), and the width ratio (b1/b).

After that, Leonhardt and Moning [] proposed an alternative concept to calculate the bursting force. The approach is based on the proposition of an equation based on the transverse tensile stresses diagram along a centered vertical axis under the loading area. It can be noticed that even through different methods, Leonhardt’s solution can be represented by a modified strut-and-tie model. Guyon [] proposed an approximated solution with corrections to satisfy elasticity compatibility equations for a concentrated load applied in a semi-infinite strip. Thus, an equation for the peak tensile transverse stress was developed. Later, Iyengar [] proposed an exact analytical solution using the two-dimensional elastic theory to predict the splitting stress distribution in concrete blocks’ critical areas. Conforti et al. [] adapted this solution to analyze splitting and crushing loads in concrete blocks with square transverse sections. The model proposed by Conforti et al. [] was validated using an experimental campaign with splitting tests.

Another alternative approach used to predict splitting phenomena in concrete specimens is presented by He and Liu []. In this case, the prediction is based on compression-dispersion models, in which the load paths are mathematically visualized by infinite isostatic lines with their own geometric and physical boundary conditions.

More recently, Liao et al. [] proposed a strut-and-tie structure like the work of Leonhardt and Moning [], which was focused on predicting the splitting load for TBM tunnels. Therefore, the formulation proposed can differ between two scenarios: (1) blocks with a height lower than the disturbance length, namely short blocks, and (2) blocks with a height equal to or greater than the disturbance length, namely long blocks. This classification is essential considering the boundary conditions and the non-uniform distribution of compressive stresses at the base of the long blocks. The main hypothesis of this model is that the fiber content does not influence the splitting load (Fpred). This assumption is valid due to the increase in importance of its contribution after the cementitious matrix cracks [,]. Some auxiliary parameters (k1 = 0.33, h’ and a2) are used as functions of geometric characteristics (such as specimens’ width, and height).

The most recent analytical model found in the literature to predict splitting is presented by Boye et al. []. This study proposes a linear regression model, in the form of y = α + βx, where α and β are functions of b and e. The model uses numerical results to improve predictions with low width ratios (b1/b) and consider the eccentricity effects. This study proposes a linear regression model based on numerical results to improve predictions with low width ratios (b1/b) and consider the eccentricity effects. The equation is designed for the peak transverse tensile stress and the applied load stress ratio (σpeak/σo). This analytical model was used by adopting the same strategy used in Guyon’s model for the peak and applied stresses, which allows for the calculation of Fpred.

From all analytical models presented, it can be noticed that each one presents different characteristics to consider the splitting behavior: the elastic solutions provided by Guyon [] and Iyengar [] are based on the expected stress flow along specimens’ height to distribute the stresses; the strut and tie model improved by Liao et al. [] considers this mechanism and also the boundary conditions of the segments; He and Liu [] showed mathematical formulations to give a parametric approach for the compression-dispersion; and Boye et al. [] improved solutions regarding eccentricity effects and low width ratios.

2.2. Experimental Campaigns Available in the Literature

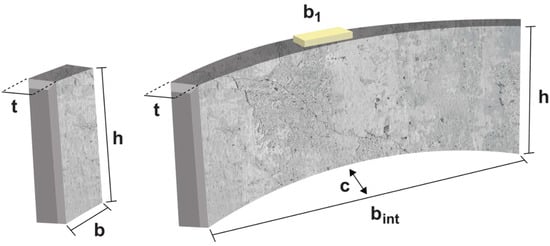

A review of the studies from 2001 to 2022 regarding experimental programs focused on evaluating precast segments under concentrated loads was conducted. The studies can be divided into two main groups: concrete blocks and full/partial-scale specimens (testing concrete segments with curvature). Figure 3 illustrates the geometrical dimensions for concrete blocks and full/partial-scale segments, in which t is the thickness, b is the base length, and h is the height of the specimen. The parameter c is a dimension created to assess the curvature of the segment, bint is an internal base length of the segments, and b1 is the length in which the load is applied.

Figure 3.

Geometrical dimensions for concrete blocks (left) and full/partial-scale segments (right).

For all the experimental campaigns, the cracking patterns were consistent with splitting and spalling cracks. Considering the concrete blocks tested, the specimens’ aspect ratio (h/b) varied from 0.33 to 3.00, meaning that the experimental campaigns with insufficient length and sufficient length to homogenize the stresses have been evaluated. The reinforcement solutions employed in these campaigns were plain concrete, steel rebars, steel fibers, polymeric fibers, and hybrid solutions (rebars + steel fibers). The steel fiber content ranged from 35 to 80 kg/m3, and the synthetic fiber content in literature results mainly were 10 kg/m3. For all cases, the concrete blocks were tested under perfect support conditions.

Most concrete blocks evaluated in the literature have been tested under one centered jack in a line load condition. Gettu et al. [] and Breitenbucher et al. [] presented test setups with load eccentricity. Conforti et al. [] evaluated a test setup considering the axial load applied by two jacks equally spaced from the center. Breitenbucher et al. [] conducted an experimental setup in which the loading was not applied entirely along the specimens’ thickness (i.e., point line condition). For all cases, the concrete compressive strength varied from 40 to 60 MPa, the exception being the work of Breitenbucher et al. [] with concretes in the 75 to 95 MPa range.

Considering the full/partial-scale segments tested, the aspect ratio (h/b) varied from 0.34 to 0.66, meaning that the experimental campaigns were conducted with insufficient length to homogenize the stresses. As verified, the segments do not have sufficient height to uniformly dissipate the transversal at the base of segments, denoted by the h/b < 1. Also, the reinforcement solutions for segments were plain concrete, steel rebars, steel fibers, polymeric fibers, and hybrid solutions (rebars + steel fibers). The steel fiber content ranged between 10 and 60 kg/m3, while the synthetic fiber content mainly was 10 kg/m3.

Most segments were tested with one or two centered jacks in a line load condition and perfect support. Sorelli and Toutlemonde [] tested a setup with extremely off-centered loading since the supports were as widely spaced to maximize the bending moment. The works of [,,,] Beno and Hilar [] tested cantilever configurations for support and/or loading conditions. The concrete compressive strength varied from 35 to 60 MPa for most campaigns, except for the works of [,,].

3. Materials and Methods

The proposed analytical models and their approaches can be evaluated according to their accuracy to predict the experimental results. Some of these studies developed experimental campaigns to validate the models. However, experimental studies have restricted boundary conditions, making a broader evaluation difficult. In this sense, a more significant number of experimental studies were collected to verify the accuracy of the analytical models in predicting the splitting of segments for TBM tunnels. This approach can provide a broader range of validation. Therefore, this section describes the experimental studies used for this evaluation and the evaluated models’ selection.

3.1. Selected Experimental Campaigns

The experimental splitting crack load (Fexp) in the campaigns was collected and later compared to the results obtained by the analytical formulations proposed in the literature. Taking as a basis the literature review conducted in Section 2.2, 26 experimental splitting load (Fexp) values were extracted from 7 of the 18 studies found in the literature. The selection criteria considered only the experimental setups with perfect support conditions, centered jacks, and results that allowed the estimation of the experimental splitting load values. In this sense, most works considered for the analysis were conducted with concrete blocks, with only two results for full-scale concrete segments. Also, only three studies provided Fexp values with more than one jack-bearing pad configuration [,] and Conforti et al. [].

Table 2 summarizes the relevant information and Fexp results considered in this paper. The literature results were obtained considering plain concrete (PC), as well as a wide variety of reinforcement solutions, such as steel fiber reinforced concrete (SFRC), polymer fiber reinforced concrete (PFRC), conventionally reinforced concrete (RC), and hybrid solutions. It is important to note that, due to the limited size of the available database (26 cases), the influence of reinforcement type on Fexp could not be statistically isolated. The experimental programs in the literature report different reinforcement strategies, but the small number of repetitions within each category prevents a meaningful stratified analysis. For this reason, the present study evaluates model performance across the entire dataset, while recognizing that reinforcement type may affect splitting resistance and should be examined in future work with expanded and more homogeneous experimental data.

Table 2.

Summary of the relevant information and Fexp results considered in this paper.

Taking as a basis the experimental results, the mean matrix tensile strength was estimated based on the equation proposed by the Model Code-10 [] as

where fMC is the estimated tensile strength of concrete (in MPa); fc is the average compressive strength of concrete (in MPa); and is taken as 8 MPa according to the Model Code-10 []. It is important to remark that Liao et al. [] experimentally evaluated the concrete tensile strength using two indirect tensile strength tests: the double punch and Brazilian tests. In this sense, the influence of using fMC or the experimental tensile strengths determined by the DPT and Brazilian test on the prediction of each analytical model was conducted. Therefore, the results are presented based on the input parameter for the tensile strength of the matrix, being identified as fMC for those estimated by Equation (1); fDPT for the experimental results employing the double punch test; and fBRT for the experimental results employing the Brazilian test based on the work of Liao et al. [].

3.2. Selected Analytical Models

Section 2.1 presents the models with different assumptions to predict the Fpred values. In summary, the elastic solutions provided by Guyon [] and Iyengar [] are based on the expected stress flow along specimens’ height to distribute the stresses; the strut and tie model improved by Liao et al. [] considers this mechanism and also the boundary conditions of the segments; He and Liu [] showed mathematical formulations for a parametric approach for the compression-dispersion; and Boye et al. [] improved solutions regarding eccentricity effects and low width ratios. Lastly, it is important to remember that these models were developed without considering the reinforcement strategy adopted (i.e., FRC, RC, or RC-FRC). Thus, the parametric analysis conducted in this paper focused on evaluating the influence of the concrete parameters and the dimension of specimens in the results.

Table 3 summarizes the analytical models evaluated in this study. This study evaluated all the analytical models in the literature that could determine the splitting crack load (Fpred) based on ft. Henceforth, the strut and tie model proposed by Morsch [] and Leonhardt and Moning [] was not employed since these models consider the bursting forces instead of ft to determine the predicted splitting crack load (Fpred).

Table 3.

Analytical models evaluated in this study.

The analytical models require the input of the concrete’s tensile strength to calculate the Fpred value. In this sense, the fMC values and the geometric parameters presented in Table 3 were employed as input for the analytical models to calculate the Fpred analytically. Lastly, a parametric study was conducted to evaluate the influence of fMC or the experimental tensile strengths of fDPT and fBRT on the prediction of each analytical model.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The applicability of the analytical models presented in Section 3.2 was compared to the experimental data listed in Section 3.1 and analyzed from a statistical standpoint, focusing on the difference between the predicted splitting load (Fpred) and the experimental load (Fexp). The statistical analysis considered the concept of relative error (RE) as follows:

where RE is the relative error (in %), Fexp is the experimental load (in kN), and Fpred is the splitting load predicted by the analytical model (in kN). Therefore, the more negative an analytical model’s RE, the more in favor of safety it will be.

The RE value was calculated considering each analytical model and compared to each Fexp result compiled in Table 3. In this sense, the first statistical analysis evaluated the relative error between Fexp and Fpred considering the fMC. After this first analysis, a particular investigation based on the experimental results of Liao et al. [] was conducted. This study was selected because the authors present the tensile strength of the material, taking as basis the Brazilian test and the double punch test. The second analysis was focused on comparing the splitting loads estimated by all the analytical models, taking as input three alternative tensile strength values: fMC, fBRT and fDPT.

Once all the RE values were calculated, the results were presented in boxplot diagrams, violin plots, qqplots, probability density function graphs, and descriptive statistics [,,,]. In the representation of figures, a differentiation in the symbology is employed to represent the specimens’ type (block or segment) and number of jacks to enable a discussion about the size effect. The discussion used the interquartile range (IQR), represented by the boxes’ range in the boxplot diagrams. The central tendency, dispersion, and distribution of relative errors were evaluated at this stage. Then, the influence of the width ratio (b1/b) and aspect ratio (h/b) on the analytical models’ results was assessed by linear regression models between the RE and each influence factor. This evaluation was conducted considering all the analytical models separately.

4. Results and Discussion

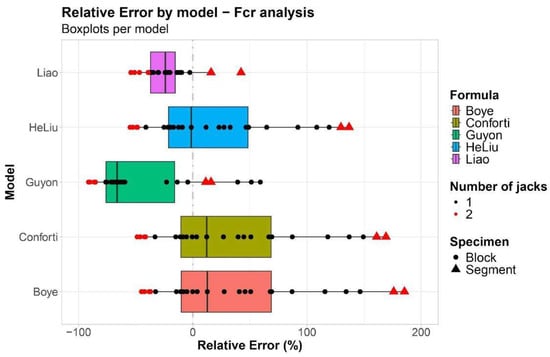

4.1. Applicability of the Models Considering the fMC

This section employed all analytical models to predict the splitting load as a function of specimens’ dimensions while considering the fMC. Figure 4 shows the applicability of analytical models to predict the experimental splitting results in the literature. The results show that the analytical models tend to underestimate the splitting load when applied for concrete blocks under double jack configuration, which the red dots may see in Figure 4. Contrarily, the models tend to overestimate the splitting load when applied to real scale segments tested under double jack configuration, verified by the red triangles in Figure 4. The latter is verified by the highest positive relative errors among all cases tested, except for the model proposed by Guyon []. This is an important finding as it demonstrates that analytical models tend to present results that are against safety, especially when predicting segment behavior. The observed decrease in model accuracy at full scale can be attributed to nonlinear stress redistribution, concrete heterogeneity, and reduced confinement stiffness in real segments. As the h/b ratio approaches unity, localized cracking and boundary compliance amplify deviations between analytical predictions and experimental results, which is consistent with the high positive relative errors observed in full-scale configurations.

Figure 4.

Applicability of the analytical models to predict experimental splitting results in the literature.

These results show that the capacity of the models to predict splitting is influenced by the test configuration (single or double jacks) and the specimens’ geometry, size, and scale. Given the limited number of studies in the literature employing concrete blocks and segments under double jack configuration, the quantitative comparison between groups (one and more one jack) is inconclusive. Even with this consideration, an inferential approach was employed to analyze the data, and the results were assumed to be from the same statistical population.

In terms of central tendency, the models exhibited different behaviors. Guyon [] and Liao et al. [] models presented the medians and an IQR that underestimate the splitting load, with relative errors centered around −70% and −25%, respectively, favoring safety for design purposes. Alternatively, He and Liu [] model showed a tendency centered in zero, with more dispersion for positive relative errors. The analytical models proposed by Conforti et al. [] and Boye et al. [] presented positive central tendencies with very similar relative error distributions, which means that employing these models is against safety when designing segments for splitting. This similarity occurred because both models have a similar base for their formulation by tending to an elastic solution, applicable for specimens with moderate to high width ratios (b1/b) and where thrust jack loads are applied without eccentricity. As eccentricity effects and low width ratios are introduced, the Conforti et al. [] and Boye et al. [] models are expected to provide different results.

Regarding dispersion, it can be noticed that Liao et al. [] model presented the lowest dispersion results with a range of approximately 50% relative error. In other words, the Liao et al. [] model demonstrated a high level of accuracy in predicting the splitting load. The models presented by He and Liu [], Conforti et al. [] and Boye et al. [] had similar dispersion ranges with magnitudes higher than 200%. The model proposed by Guyon [] showed segregation in results under −50% and results with a relative error greater than −25%, which indicates the influence of geometrical parameters (e.g., width ratio or specimen’s aspect ratio) in the overall response. In this condition, the results presented by this model are in favor of security in the sense of predicting splitting and may lead to a less economical design, depending on the magnitude of the safety factor.

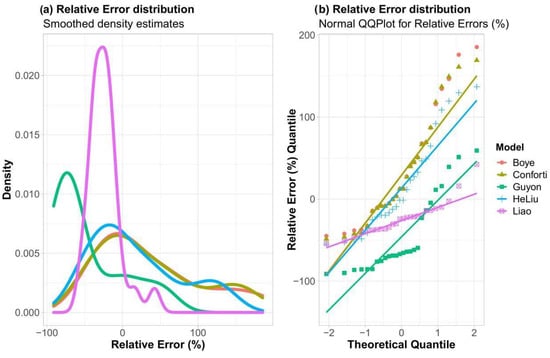

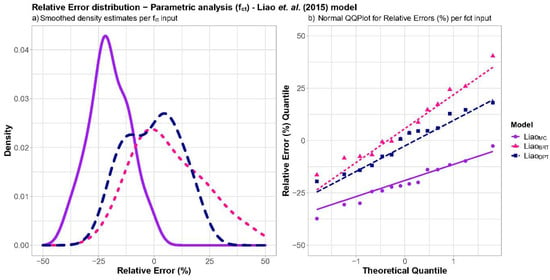

Figure 5 shows the probability density estimates and normal qqplots of the relative errors for each model. The density estimates show two peaks for all models with different intensities for the second peaks. The magnitude of these peaks is related to the highest positive relative errors exhibited in each model. It can be noticed that Liao et al. [] model presented a more abrupt second peak, which is coherent with the two highest values observed in the boxplot (see Figure 4). Alternatively, the model proposed by Guyon [] showed the more dispersed second peak, which is correlated to the observed segregation of results. Lastly, the second peak was less evident for all the remaining models evaluated.

Figure 5.

Graphs of (a) probability density estimates and (b) normal qqplots for the relative errors for each model.

Besides the second peaks, the shapes of the distributions have shown a normal/gaussian appearance. The normal qqplots presented the adherence of the observed values with the equivalent assumed normal distribution. Guyon’s [] model was the least adherent due to the mentioned segregation. He and Liu [], Conforti et al. [] and Boye et al. [] models showed better adjusts for the central portion of data, with less concordance in the extremities of their distributions. Liao et al. [] model showed the most adherent distribution, with only two points significantly apart from an assumed normal distribution (represented by the straight purple line), both located in the positive tail. As mentioned in the boxplot analysis, a greater number of usable experimental results with the configurations present in those two higher values (real scale segments with more than one jack thrust), could help to evaluate if this tail behavior is due to different populations (and, thus, need to segregate the data) or consequence of the intrinsic randomness of the sampling process, scale size effects and/or other factors.

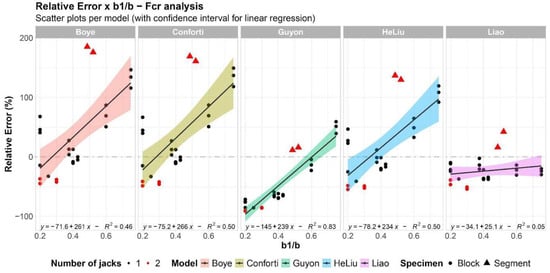

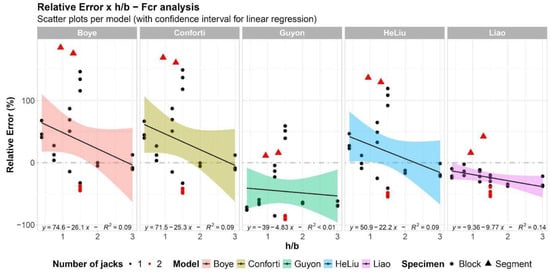

As indicated in some model deductions, besides materials inputs/characteristics (evaluated in parametric analysis), some geometric parameters such as the width ratio (b1/b) and specimens’ aspect ratio (h/b) are expected to influence the prediction. Thus, they can also be relevant in models’ relative errors and, consequently, affect the models’ safety factor used in design. Aiming at evaluating the influence of specimens’ width and aspect ratios, in the relative errors, some scatter plots with linear regression models (with the linear regressions 95 percent confidence intervals) are exposed in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Scatter plots per model: relative error vs. b1/b.

Figure 7.

Scatter plots per model: relative error vs. h/b.

As can be seen in Figure 6, all models but Liao et al. [] showed relative errors increasing tendencies as a function of the width ratio (b1/b). The variance in relative errors explained by the linear regression (i.e., the coefficient of determination R2) was about 50% for Boye et al. [], Conforti et al. [] and He and Liu [] models. Guyon’s [] model showed a higher coefficient of determination with an R2 of 83%. The aforementioned models presented a simultaneous increase in RE and b1/b ratio, which results in a reduced safety coefficient when employed for non-punctual loads (high b1/b ratio). Liao et al. [] model showed no affected response in relative errors as b1/b changed.

The results for blocks with two jacks (red dots) seemed closer to all models’ configurations with a single jack (black dots). As for the segments tested with two jacks (red triangles), Guyon’s [] model presented the closest responses to regression, while the other models exhibited some values apart from the expected ones. Unfortunately, the limited usable results in this condition make comparison analysis impractical.

For the aspect ratio analysis presented in Figure 7, it can be noticed that only Liao et al. [] model exhibited some influence on relative errors as h/b increased, but with a small coefficient of determination (R2 = 14%). This demonstrates the robustness of this model in relation to these geometric parameters’ variation, which is compatible with the assumptions adopted by Liao et al. [] during the conception of the analytical model. The other models showed explicit distinct behavior at the h/b = 1.5 with an R2 lower than 10%. An increase in relative errors was found as the aspect ratios came between 0.5 and 1.5. After this aspect ratio, an abrupt behavior change was observed, with more than 80% difference between neighboring points. No tendency was observed with an increase in h/b after this point. The lack of influence of specimens’ aspect ratio for these models can be explained by the assumptions of developed solutions considering semi-infinite strips, i.e., height enough specimens to overcome the disturbance length. For all models, the relative errors showed no influence from the h/b factor, with poor adherence to the generated linear regressions.

Moreover, the model proposed by Liao et al. [] was the most accurate model evaluated in this study, with the least dispersive response. Additionally, the Liao et al. [] model showed excellent adherence to a normal distribution with a relative error centered at approximately −25% and minimal influence of specimens’ width ratio (b1/b) and aspect ratio (h/b), showing a higher level of robustness. The model proposed by Guyon [] showed the best responses for real scale segments with two jacks for two reasons: (1) the relative error was lower than 25%; and (2) the adherence in the regression model based on the width ratio. It is important to remark that a segregation in the response obtained by the Guyon [] model was observed, and the behavior of its relative errors was satisfactorily described (R2 = 0.83) as a function of the width ratio (b1/b). Lastly, the models proposed by He and Liu [], Conforti et al. [], and Boye et al. [] showed similar tendencies and results with significant influence as a function of width ratio, and none of the models presented good adherences in the linear regressions as a function of specimens’ aspect ratios (h/b).

Based on the results previously presented, two main options are suggested to enhance the splitting load prediction from the applicability analysis performed: the use of the model proposed by Liao et al. [] with a correction for bias, assuming a normal distribution of the relative errors (centered at −25%) and the use of Guyon [] equation with a parametric correction obtained from the linear regression between relative error and width ratio (b1/b). Table 4 presents the improved analytical models suggested by the applicability analysis. The proposed corrections are presented in bold characters. It is important to remark that more experimental campaigns with two (or more) jacks are desirable to validate the assumption that the results originated from the same population, which was considered in this analysis.

Table 4.

Improved analytical models suggested from the applicability analysis.

4.2. Applicability of the Models Considering Experimental fct Values

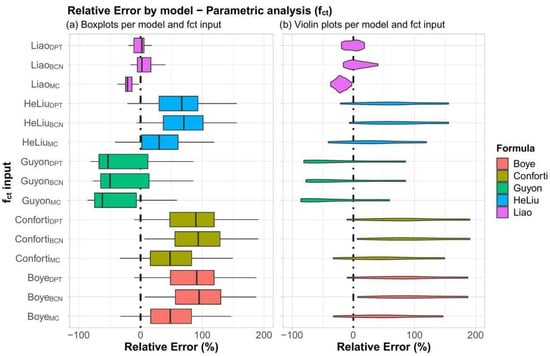

In this section, the influence of using the fib Model Code approach to estimate the matrix tensile strength (fMC), the experimental tensile strengths determined by the DPT (fDPT), or the Brazilian test (fBRT) for the prediction of each analytical model was analyzed. Figure 8 illustrates the relative error box and violin plots as a function of the input tensile strength.

Figure 8.

Relative error (a) box and (b) violin plots as a function of the input tensile strength.

For the models of Liao et al. [] and Guyon [], the use of fDPT and fBRT resulted in predicted values closer to the splitting load obtained experimentally when compared to their results using fMC. This indicates that these models present better predictions when used associated with experimental tensile inputs. In this sense, employing the fMC values in the Liao et al. [] and Guyon [] models would lead to predicted splitting loads that are in favor of safety when compared to using fDPT and fBRT. For all models evaluated, the use of fMC resulted in predicted values that are “more to the left” in the x-axis, represented by their boxes with a left offset when compared to fBRT and fDPT. Although the models proposed by He and Liu [], Conforti et al. [] and Boye et al. [] overestimate the splitting load (positive RE), the use of fMC led the results toward a safer scenario.

Additionally, the central tendency and IQR values were similar when comparing the predicted splitting load values estimated using fDPT and fBRT. This may indicate that employing the double punch test or the Brazilian test may yield similar splitting predictions for most of the analytical models employed in this study.

It is important to remark that the model proposed by Liao et al. [] yielded relative errors approximately centered at zero when using fDPT or fBRT. Moreover, the violin plots indicate a wide distribution of relative errors for all the models evaluated. The lowest range of relative errors was verified in the model proposed by Liao et al. [], with a range lower than 50% and the lowest IQR values regardless of employing fMC, fDPT or fBRT. These factors may indicate that the model proposed by Liao et al. [] has higher accuracy and precision than the other models evaluated in this study, especially when employing experimental input values of fDPT or fBRT.

Considering the response obtained by the model of Liao et al. [], a more in-depth analysis was conducted to evaluate the analytical response obtained. Figure 9 shows the probability density estimates and normal qqplots for the relative errors (%) for the model of Liao et al. [].

Figure 9.

Probability density estimates and normal qqplots for the relative errors (%) per fct input [].

The density estimations showed a more concentrated distribution when employing the fMC input, coherent with the results in Figure 5. However, it is important to recall that using fMC results in an average underestimation of ~25% of the splitting loads, while using fDPT or fBRT resulted in relative errors closer to zero. The systematic underestimation associated with fMC-based predictions arises from the conservative nature of the fib Model Code 2010 tensile strength equation, which does not account for local confinement and the tri-axial compressive state induced by TBM jack loading. These boundary effects increase the effective tensile resistance beyond what is predicted from uniaxial tensile correlations, resulting in the observed deviation. This means that the use of fMC yields more precise predicted splitting load values, although less accurate than those obtained when employing the experimental input values of fDPT or fBRT. In this sense, the fBRT presented a two-peak distribution, while the fDPT presented the most centered distribution relative to the origin. As for the shape of the distributions, the normal qqplots showed good adherence for fMC, fDPT, and fBRT inputs.

Among all analytical models tested, the model proposed by Liao et al. [] provided Fpred estimates with lower relative error, independently of the input choice. For Liao et al. [] model, the fDPT input showed a centered relative error distribution with good agreement to a normal distribution, and the fMC input yielded the lowest dispersion among the scenarios tested, although with an underestimation of Fpred.

5. Conclusions

This paper evaluated the applicability of analytical models to predict splitting in concrete segments employing a refined statistical analysis. In this context, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- -

- The splitting load under double jack configuration predicted by the analytical models tends to be generally underestimated for concrete blocks and overestimated for real scale segments. This means that the capacity of the models to predict splitting is influenced by the geometry, size, and scale of the specimens, as well as the test configuration (single or double jacks).

- -

- Given the limited number of studies in literature employing concrete blocks and segments under double jack configuration, the quantitative comparison between groups (one and more one jack) is inconclusive. In this sense, the data was assumed to be from the same statistical population for all subsequent conclusions.

- -

- The models presented distinct behaviors: Guyon [] and Liao et al. [] models presented central tendency results that underestimate the splitting load, which is in favor of safety for design purposes. Alternatively, He and Liu [] model showed a tendency centered in zero with a right-skewed distribution (more dispersion for positive relative errors). Conforti et al. [] and Boye et al. [] presented positive central tendencies with similar relative error distributions, meaning that these models are against safety when designing segments for splitting.

- -

- The model proposed by Liao et al. [] was the most accurate model evaluated in this study, with the least dispersive response. Additionally, the Liao et al. [] model showed great adherence to a normal distribution with a relative error centered at approximately −25% and minimal influence of geometrical parameters, such as specimens’ width ratio (b1/b) and aspect ratio (h/b). Guyon [] showed the best responses for real scale segments with two jacks based on the magnitude of the relative error and the adherence in the regression model based on the width ratio (b1/b).

- -

- The influence of the tensile strength parameter used as input for the analytical models was evaluated. Three different approaches were evaluated: fib Model Code 2010 [] approach (fMC), the DPT (fDPT), and the Brazilian test (fBRT). It was shown that Liao et al. [] and Guyon [] presented better predictions when used associated with experimental tensile inputs (fBRT and fDPT). Moreover, using fMC led the results toward a safer scenario for the models proposed by He and Liu [], Conforti et al. [], and Boye et al. [].

- -

- Based on the results of this study, improved analytical models for Liao et al. [] and Guyon [] are suggested from the applicability analysis. The improvement in the Liao et al. [] model was based on a correction for bias, while the model of Guyon [] was improved regarding its relation to the width ratio (b1/b).

This study provided an empirical evaluation and statistical calibration of existing analytical models for predicting splitting in precast concrete segments subjected to TBM thrust. The main empirical observations indicate that current analytical solutions tend to underestimate the splitting load for concrete blocks and overestimate it for full-scale segments, reflecting scale and boundary stiffness effects. Among the assessed formulations, the models by Liao et al. [] and Guyon [] demonstrated the most consistent behavior, with the proposed bias and regression corrections improving their predictive reliability. From these results, it is recommended that practitioners apply the bias-corrected formulations to enhance design accuracy while maintaining safety margins consistent with fib Model Code guidance. These conclusions distinguish between the experimental trends observed and the methodological adjustments proposed, offering both diagnostic and prescriptive outcomes for TBM segment design.

Future research should focus on extending the present framework through three-dimensional finite element calibration of the evaluated analytical models to capture local confinement and boundary effects more accurately. Additional investigations should consider eccentric and asymmetric loading conditions typical of TBM jack arrangements, as well as the development of hybrid analytical–statistical approaches that integrate mechanical formulations with data-driven corrections. Such advancements could significantly enhance the robustness and generalization of splitting load predictions across different segment geometries and reinforcement configurations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.H.M., R.S., R.N., R.R.A., A.D.d.F. and L.A.G.B.J.; methodology, T.H.M., R.S., R.N. and R.R.A.; software, T.H.M. and R.N.; validation, T.H.M., R.S., R.N., R.R.A., A.D.d.F. and L.A.G.B.J.; formal analysis, T.H.M., R.S., R.N., R.R.A., A.D.d.F. and L.A.G.B.J.; investigation, T.H.M., R.S., R.N. and R.R.A.; resources, A.D.d.F. and L.A.G.B.J.; data curation, T.H.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.H.M. and R.S.; writing—review and editing, T.H.M., R.S., R.N., R.R.A., A.D.d.F. and L.A.G.B.J.; visualization, T.H.M., R.S. and R.R.A.; supervision, A.D.d.F. and L.A.G.B.J.; project administration, T.H.M., A.D.d.F. and L.A.G.B.J.; funding acquisition, A.D.d.F. and L.A.G.B.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Ramoel Serafini would like to thank the support of Anima Institute—AI [grant #66/2024] and the São Paulo Research Foundation—FAPESP [grant #2022/14045-5]. Antonio D. de Figueiredo would like to acknowledge CNPq for the support [grant #305673/2023-8]. Luís A.G. Bitencourt Jr. would also like to acknowledge the fellowship of research productivity (PQ) granted by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development—CNPq [grant #307175/2022-7] and for the support of the São Paulo Research Foundation—FAPESP [grant #2022/03179-0].

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Josa, I.; Aguado, A. Infrastructure, Innovation and Industry as Solutions for Breaking Inequality Vicious Cycles. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 297, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenert, D.; Mattauch, L.; Edenhofer, O.; Lessmann, K. Infrastructure and Inequality: Insights from Incorporating Key Economic Facts about Household Heterogeneity. Macroecon. Dyn. 2018, 22, 864–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäppler, K. New Developments in TBM Tunnelling for Changing Grounds. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 57, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lance, G.A. The Risk to Third Parties from Bored Tunnelling in Soft Ground; Health and Safety Executive: Merseyside, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto, M. Causes of Shield Segment Damages during Construction. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Underground Excavation and Tunnelling, Bangkok, Thailand, 2–4 February 2006; pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalaro, S.H.P.; Blom, C.B.M.; Walraven, J.C.; Aguado, A. Structural Analysis of Contact Deficiencies in Segmented Lining. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2011, 26, 734–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conforti, A.; Tiberti, G.; Plizzari, G.A. Combined Effect of High Concentrated Loads Exerted by TBM Hydraulic Jacks. Mag. Concr. Res. 2016, 68, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanes, R.M.; Greco, M.; Guerra, M.B.B.F. Strut-and-Tie Models for Linear and Nonlinear Behavior of Concrete Based on Topological Evolutionary Structure Optimization (ESO). Rev. IBRACON Estrut. Mater. 2019, 12, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneweg, T.W. Shield Driven Tunnels in Ultra High Strength Concrete, Reduction of the Lining Thickness. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, M.V.G.; Bitencourt, L.A.G.; Das, S. A Performance-Based Optimization Framework Applied to a Classical STM-Designed Deep Beam. Structures 2022, 41, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, M.V.G.; Paini, B.; Bitencourt, L.A.G., Jr.; Das, S. Design and Experimental Investigation of Deep Beams Based on the Generative Tie Method. Eng. Struct. 2022, 255, 113913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T.T.C. Unified Theory of Reinforced Concrete; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Zaborac, J.; Choi, J.; Bayrak, O. Assessment of Deep Beams with Inadequate Web Reinforcement Using Strut-and-Tie Models. Eng. Struct. 2020, 218, 110832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Kim, M.S. Investigation and Improvement of Bursting Force Equations in Posttensioned Anchorage Zone. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 9807975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsh, E. Uber Die Berchnung Der Gelenkquader. In Beton und Eisen; Verlag von W. Ernst and Sohn: Berlin, Germany, 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt, F.; Monnig, E. Part I. Fundamentals in the Design of Reinforced Concrete Construction. In Lectures on Structural Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1973; pp. 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Guyon, Y. Prestressed Concrete; UC Berkeley Transportation Library: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Conforti, A.; Tiberti, G.; Plizzari, G.A. Splitting and Crushing Failure in FRC Elements Subjected to a High Concentrated Load. Compos. B Eng. 2016, 105, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liu, Z. Investigation of Bursting Forces in Anchorage Zones: Compression-Dispersion Models and Unified Design Equation. J. Bridge Eng. 2011, 16, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; de la Fuente, A.; Cavalaro, S.; Aguado, A.; Carbonari, G. Experimental and Analytical Study of Concrete Blocks Subjected to Concentrated Loads with an Application to TBM-Constructed Tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2015, 49, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, B.A.; Abbey, S.J.; Ngambi, S.; Fonte, J. Development of Improved Models for Estimation of Bursting Stresses in Elements under High-Concentrated Load. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2019, 16, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnütgen, B.; Erdem, E. Sub-Task 4.4–Splitting of SFRC Induced by Local Forces; Ruhr-University: Bochum, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tiberti, G.; Conforti, A.; Plizzari, G.A. Precast Segments under TBM Hydraulic Jacks: Experimental Investigation on the Local Splitting Behavior. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2015, 50, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabucchi, I.; Tiberti, G.; Conforti, A.; Medeghini, F.; Plizzari, G.A. Experimental Study on Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete and Reinforced Concrete Elements under Concentrated Loads. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 307, 124834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caratelli, A.; Meda, A.; Rinaldi, Z. Design According to MC2010 of a Fibre-Reinforced Concrete Tunnel in Monte Lirio, Panama. Struct. Concr. 2012, 13, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, K.S.R. Two-Dimensional Theories of Anchorage Zone Stresses in Post-Tensioned Prestressed Beams. J. Proc. 1962, 59, 1443–1466. [Google Scholar]

- Serafini, R.; Santos, F.P.; Agra, R.R.; De la Fuente, A.; Figueiredo, A.D. de Effect of Specimen Shape on the Compressive Parameters of Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete after Temperature Exposure. J. Urban Technol. Sustain. 2018, 1, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentur, A.; Mindess, S. Fibre Reinforced Cementitious Composites, 2nd ed.; Bentur, A., Mindess, S., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gettu, R.; Barragán, B.; García, T.; Fernández, C.; Oliver, R. Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete for the Barcelona Metro Line 9 Tunnel Lining. In Proceedings of the 6th International RILEM Symposium on Fibre Reinforced Concretes, Varenna, Italy, 20–22 September 2004; pp. 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Breitenbücher, R.; Meschke, G.; Song, F.; Hofman, M.; Zhan, Y. Experimental and Numerical Study on the Load-Bearing Behaviour of Steel Fibre Reinforced Concrete for Precast Tunnel Lining Segments under Concentrated Loads. In Proceedings of the FRC 2014 Joint ACI-fib International Workshop, Montreal, QC, Canada, 24–25 July 2014; pp. 417–429. [Google Scholar]

- Sorelli, L.; Toutlemonde, F. On the Design of Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Tunnel Lining Segments. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Fracture, Turin, Italy, 20–26 March 2005; pp. 5702–5707. [Google Scholar]

- Poh, J.; Tan, K.H.; Peterson, G.L.; Wen, D. Structural Testing of Steel Fibre Reinforced Concrete (SFRC) Tunnel Lining Segments in Singapore. In Proceedings of the World Tunnel Congress 2009, Budapest, Hungary, 23–28 May 2009; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hilar, M.; Vitek, J.L.; Pukl, R. Laboratory Testing and Numerical Modelling of SFRC Tunnel Segments. In Proceedings of the Eastern European Tunnelling Congress, Budapest, Hungary, 18–21 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Meda, A.; Rinaldi, Z.; Caratelli, A.; Cignitti, F. Experimental Investigation on Precast Tunnel Segments under TBM Thrust Action. Eng Struct 2016, 119, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo, S. Influence of Non-Uniform Support on FRC and Hybrid Precast Tunnel Segments with Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer Bars under TBM Thrust. In Proceedings of the First fib Italy YMG Symposium on Concrete and Concrete Structures, Parma, Italy, 15 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Beňo, J.; Hilar, M. Steel Fibre Reinforced Concrete for Tunnel Lining–Verification by Extensive Laboratory Testing and Numerical Modelling. Acta Polytech. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, S.; Soliman, A.; Nehdi, M. Structural Behaviour of Ultra-High Performance Fibre Reinforced Concrete Tunnel Lining Segments. In Proceedings of the FRC 2014 Joint ACI-fib International Workshop. Fibre Reinforced Concrete Applications, Montreal, QC, Canada, 24–25 July 2014; pp. 532–543. [Google Scholar]

- Conforti, A.; Trabucchi, I.; Tiberti, G.; Plizzari, G.A.; Caratelli, A.; Meda, A. Precast Tunnel Segments for Metro Tunnel Lining: A Hybrid Reinforcement Solution Using Macro-Synthetic Fibers. Eng. Struct. 2019, 199, 109628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federation Internationale du Beton. FIB Model Code for Concrete Structures 2010; Ernst & Sohn: Berlin, Germany, 2013; 434p, ISBN 978-3-433-03061-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bussab, W.; Morettin, P.A. Estatística Básica; Saraivauni, Ed.; Saraivauni: São Paulo, Brazil, 2017; ISBN 9788547220228. [Google Scholar]

- Devore, J.L. Probability and Statistics for Engineering and the Sciences, 9th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-305-25180-9. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, M.V.G.; Bitencourt, L.A.G.; Das, S. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Large-Scale Reinforced Concrete Deep Beams Designed with the Generative Tie Method. Structures 2023, 58, 105555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).