A Review of Transmission Line Icing Disasters: Mechanisms, Detection, and Prevention

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- An interdisciplinary framework is adopted, positioning advancements in AI and new materials as key catalysts for innovation in icing mitigation. The study examines their integration with power engineering, highlighting application methodologies and future potential to inspire novel solutions.

- (2)

- A focused analysis of research developments over the past decade is provided, with particular attention to emerging approaches such as deep learning-based intelligent monitoring, novel DC de-icing circuit topologies, and photothermal superhydrophobic coatings, ensuring the timeliness and relevance of the review.

- (3)

- A holistic “mechanism–detection–prevention–trend” analytical framework is established. This structure not only synthesizes the current technological landscape but also elucidates underlying scientific principles and evolutionary pathways, thereby enabling readers to develop a systematic understanding and identify promising research directions.

2. Overview of Transmission Line Icing

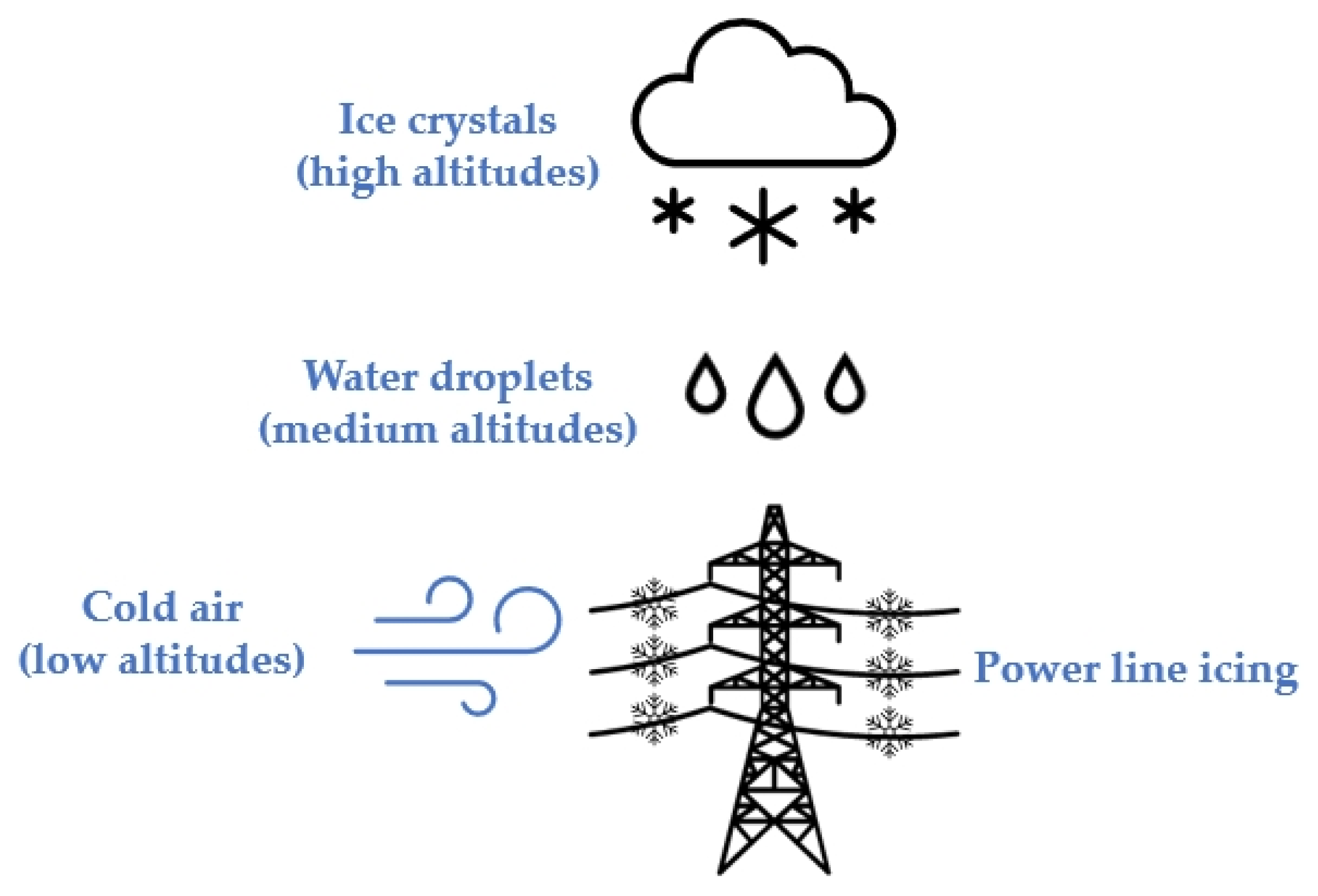

2.1. Formation of Icing

2.2. Classification of Icing

2.3. Factors Influencing Icing

2.3.1. Meteorological Conditions

2.3.2. Geographical Environment

2.3.3. Line Characteristics

2.4. Summary

3. Detection and Monitoring Technologies for Transmission Line Icing

3.1. Conventional Detection and Monitoring Technologies

3.1.1. Natural Icing Observation Stations

3.1.2. Simulated Conductor Method

3.1.3. Mechanical Modeling Method

3.1.4. Optical Fiber Sensor Method

3.2. Image-Based Detection and Monitoring Technologies

3.2.1. Image Detection and Monitoring Method

3.2.2. Deep Learning-Based Detection and Monitoring Methods

3.3. Summary

4. De-Icing and Anti-Icing Technologies for Transmission Lines

4.1. De-Icing Technologies for Transmission Lines

4.1.1. Mechanical De-Icing

4.1.2. Short-Circuit De-Icing

AC Short-Circuit De-Icing

DC Short-Circuit Current De-Icing

4.1.3. Ice-Melting of Bundled Conductors

4.2. Anti-Icing Technologies for Transmission Lines

4.2.1. Anti-Icing by Controlling Conductor Surface Electric Field Strength

4.2.2. Anti-Icing Superhydrophobic Coatings

4.2.3. Anti-Icing Expanded-Diameter Conductors

4.2.4. Other Anti-Icing Technologies

4.3. Summary

5. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| AC | Alternating Current |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CGM | Cross-Guide Module |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CG-UNet | Cross-Guide-UNet |

| CNN-RF | Convolutional Neural Network—Random Forest |

| CNT | Carbon Nanotubes |

| DABM | Dilated Asymmetric Bottleneck Module |

| DC | Direct Current |

| EDPNet | Efficient Dynamic Perception Network |

| EECNet | Efficient Edge Computing Network |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machine |

| EM-DCA | Expectation Maximization Dynamic Convolutional Attention |

| EPCM | Efficient Partial Conversion Module |

| Es | Surface Electric Field Strength |

| F1-score | Balanced F-Score |

| FBG | Fiber Bragg Grating |

| FCM | Fuzzy C-Means |

| FFNN | Feedforward Neural Network |

| FPN | Feature Pyramid Network |

| GMSA-Net | Global Micro Strip Awareness Network |

| GMAM | Global Micro-Awareness Module |

| GPR | Gaussian Process Regression |

| GSO | Glowworm Swarm Optimization |

| GWO | Gray Wolf Optimizer |

| IULBP | Improved Uniform Local Binary Patterns |

| KELM | Kernel Extreme Learning Machine |

| KPCA | Kernel Principal Component Analysis |

| K-SVD | k Singular Value Decomposition |

| LDKA-Net | Large Dynamic Kernel Aggregation Net |

| LE-SS | Low-emissivity Solar-assisted Superhydrophobic |

| LMRC | Lightweight Multi-dimensional Recombination Convolution |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAGSAC | Marginalizing Sample Consensus |

| mIoU | mean Intersection over Union |

| MMC | Modular Multilevel Converter |

| mPA | mean Pixel Accuracy |

| MSCM | Mixed Strip Convolution Module |

| MSR | Multi-Scale Retinex |

| MVD | Median Volume Diameter |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| ORB | Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| RANSAC | Random Sample Consensus |

| R-CNN | Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network |

| ResNet | Residual Network |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| S-UNet | Strengthened U-Net |

| SGAN-UNet | Strengthened Generative Adversarial Network U-Net |

| SIFT | Scale-Invariant Feature Transform |

| SSD | Single Shot MultiBox Detector |

| STATCOM | Static Synchronous Compensator |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| WFVC-Net | wide field of view convolutional network |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- Dai, D.; Hu, Y.; Qian, H.; Qi, G.; Wang, Y. A novel detection algorithm for the icing status of transmission lines. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Niu, D.; Wang, P.; Lu, Y.; Xia, H. The weighted support vector machine based on hybrid swarm intelligence optimization for icing prediction of transmission line. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2015, 798325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, J.; Xing, B.; Jiang, X.; Dong, S. Collision characteristics of water droplets in icing process of insulators. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 212, 108663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Li, D.; Li, K.; Wu, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, R. Analysis and study of transmission line icing based on Grey Correlation Pearson Combinatorial optimization support vector machine. Measurement 2024, 236, 115086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.; Marques, M.C.; Loureiro, S.; Nieto, R.; Liberato, M.L. Disruption risk analysis of the overhead power lines in Portugal. Energy 2023, 263, 125583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettschneider, S.; Fofana, I. Evolution of countermeasures against atmospheric icing of power lines over the past four decades and their applications into field operations. Energies 2021, 14, 6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levchenko, I.I.; Satsuk, E.I.; Shovkoplyas, S.S. Intellectual ice melting system on wires of overhead transmission lines of distribution electric networks. In Proceedings of the International Russian Automation Conference (RusAutoCon), Sochi, Russia, 8–14 September 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Karunasingha, N.; Titov, D. An Analysis of forecasting technologies for icing events in overhead power line wires. In Proceedings of the International Ural Conference on Electrical Power Engineering (UralCon), Magnitogorsk, Russia, 29 September–1 October 2023; pp. 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Zhlobitskiy, L.; Lankin, M.; Shovkoplyas, S. Method of forecasting icing on overhead power lines wires. In Proceedings of the International Russian Automation Conference (RusAutoCon), Sochi, Russia, 10–16 September 2023; pp. 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Analysis and countermeasures of ice accident of transmission lines in Jiangxi Province. Constr. Des. Proj. 2020, 6, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Qu, X.; Gul, C.; Yang, Y. The causes and forecasting of icing events on power transmission lines in southern China: A review and perspective. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, J.; Prado, J.C.D.; Nazaripouya, H.; Bertoletti, A.Z. Enhancing power grid resilience against ice storms: State-of-the-art, challenges, needs, and opportunities. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 60792–60806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Liu, F.; Wang, Z.; Zou, G.; Peng, Y. Detection and segmentation of overhead transmission line icing images via an improved YOLOv8-seg. Electr. Eng. 2025, 107, 9635–9647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.H.; Meng, J.; Li, J.S.; Liu, Y.L.; Chang, Q.; Jiang, M.; Guo, D. Spatial distribution and division of wire icing thickness under different return periods in Shanxi Province. J. Arid Meteorol. 2022, 40, 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.Z.; Zhou, K.; Zhao, L.X.; Tan, L.; Li, H.D.; Wang, Y.N.; Cai, Y.M.; Li, C.S.; Chen, S. Prediction technology of power transmission line icing based on micrometeorological and microtopography in Beijing area. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2022, 22, 14744–14751. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yue, S.; Zeng, W. A review of icing and anti-icing technology for transmission lines. Energies 2021, 16, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Farzaneh, M.; Bouchard, G. Two-dimensional modelling of the ice accretion process on transmission line wires and conductors. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2006, 46, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Wang, J.J. Effects of micrometeorological parameters and icing time on icing of transmission line. High Volt. Appar. 2017, 53, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Hu, J.L. Prediction of transmission line icing thickness applying AMPSO-BP neural network model. Electr. Power Constr. 2021, 42, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Farzaneh, M.; Savadjiev, K. Statistical analysis of field data for precipitation icing accretion on overhead power lines. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2005, 20, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lou, W.J.; Xu, H.W.; Wang, L.Q. Numerical simulation of icing on transmission conductors considering time-varying meteorological parameters. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. 2022, 54, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Li, D.; Gao, P.; Zang, W.; Duan, Z.; Ou, J. Numerical simulation of two-dimensional transmission line icing and analysis of factors that influence icing. J. Fluids Struct. 2023, 118, 103858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.B.; Qiao, G.J.; Jiang, X.L. Study on the influence of water droplet particle size distribution on transmission line icing. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 247, 111840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.Q.; Shao, M. Impacts of complex terrain features on local wind field and PM2.5 concentration. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.L.; Wu, Z.P.; Qin, P.; Huang, H.H.; Liu, A.; Zhi, S.Q. An analysis of the characteristics of strong winds in the surface layer over a complex terrain. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 2009, 67, 452–460. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.J.; Bian, R.; Zhou, W.Z. Wind-induced flashover incident analysis of jumper considering the effect of typhoon and mountainous topography. High. Volt. Eng. 2023, 49, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L.Z. Study on icing characteristics of overhead lines in high altitude mountainous region of northwest Sichuan. Electr. Power Surv. Des. 2019, S1, 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, X. Research on ice covering mechanism and intelligent ice melting technology of transmission lines in high-altitude areas. Technol. Mark. 2025, 32, 80–83+87. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.L.; Fan, C.J.; Xie, Y.B. New method of preventing ice disaster in power grid using expanded conductors in heavy icing area. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2019, 13, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.Y.; Chen, G.; Lv, Q.Y.; Dong, L.F.; Lu, C.J. Online ice quality measurement technology based on analogue conductors. Autom. Instrum. 2023, 4, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.H.; Ge, J.F.; Ye, L.; Yang, X.J.; Gong, Y.; Huang, Z.H.; Su, L.Z. Transmission line ice detection system based on the simulated wire. Foreign Electron. Meas. Technol. 2016, 35, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, X.M.; Dun, Z.; Dou, Y.K.; Xue, Y.; Yuan, K. The design of capacitive device for detecting transmission lines ice thickness. J. Taiyuan Univ. Technol. 2014, 45, 559–561. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.B.; Sun, Q.D.; Cheng, R.G.; Zhang, G.J.; Liu, J.B. Mechanical analysis on transmission line conductor icing and application of online monitoring system. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2007, 31, 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Hao, Y.P.; Li, W.G.; Dai, D.; Li, L.; Zhu, G.H.; Luo, B. A mechanical calculation model for on-line icing-monitoring system of overhead transmission lines. Proc. CSEE 2010, 30, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Hao, Y.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Huang, Z. Detection method for equivalent ice thickness of 500-kV overhead lines based on axial tension measurement and its application. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 9001611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y.; Iwasaki, J.I.; Nakamura, K. A multiplexing load monitoring system of power transmission lines using fiber Bragg grating. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Optical Fiber Sensors: Foreword, Williamsburg, VA, USA, 28–31 October 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M.; Zhang, J.T.; Zhao, Z.G.; Li, C.; Xu, X.; Liang, S. Monitoring and analysis of icing on transmission lines based on optical fiber sensing. Chin. J. Sens. Actuators 2018, 31, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.N.; Li, X.F.; Guo, Y.F.; Zhao, L.J. Influence of wind speed on the effectiveness of monitoring of ice-covered overhead transmission line based on BOTDA. Electr. Power Eng. Technol. 2022, 41, 152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.F.; Xu, Z.N.; Guo, Y.F.; Zhao, L.J. Review of application of icing monitoring technology for transmission lines based on optical fiber sensing. J. North China Electr. Power Univ. 2023, 50, 22–34+43. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, J.Y.; Yang, S.Y.; Shu, Z.Y.; Gao, J.; Li, Z.H. Research on monitoring of ice-coating thickness of transmission line based on aerial image. High Volt. Appar. 2021, 57, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.L.; Xiao, J.; Hu, X.G. New keypoint matching method using local convolutional features for power transmission line icing monitoring. Sensors 2018, 18, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Su, P.; Feng, J.H. Measurement of icing thickness of transmission line based on fractal theory. Meas. Control. Technol. 2018, 37, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Wei, A.M. A new image detection method of transmission line icing thickness. In Proceedings of the IEEE 4th Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC), Chongqing, China, 12–14 June 2020; pp. 2059–2064. [Google Scholar]

- Nusantika, N.R.; Hu, X.G.; Xiao, J. Improvement Canny edge detection for the UAV icing monitoring of transmission line icing. In Proceedings of the IEEE 16th Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA), Chengdu, China, 1–4 August 2021; pp. 1838–1843. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Yu, H.; Liu, J.; Zhai, Y. Measurement of ice thickness based on binocular vision camera. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), Takamatsu, Japan, 6–9 August 2017; pp. 162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Nusantika, N.R.; Xiao, J.; Hu, X.G. An enhanced multiscale retinex, Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF (ORB), and Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) pipeline for robust key point matching in 3D monitoring of power transmission line icing with binocular vision. Electronics 2024, 13, 4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusantika, N.R.; Xiao, J.; Hu, X.G. Precision ice detection on power transmission lines: A novel approach with multi-scale retinex and advanced morphological edge detection monitoring. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusantika, N.R.; Hu, X.G.; Xiao, J. Newly designed identification scheme for monitoring ice thickness on power transmission lines. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.H.; He, J.C.; Alsabaan, M. Image identification method of ice thickness on transmission line based on visual sensing. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2023, 28, 1783–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.M.; Chu, S.Q.; Xu, J.J.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, Y.T. Detection of ice thickness of transmission line based on GSO-Canny algorithm. Foreign Electron. Meas. Technol. 2022, 41, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Z.Y.; Shen, J.Y.; Li, H.Q.; Xiong, H.L.; Li, S.C.; Ma, J.C. Research on the identification of transmission line ice thickness based on aerial images. China Meas. Test 2023, 49, 21–25+59. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Ma, H.; Chen, B.; Dong, G. Intensive cold-air invasion detection and classification with deep learning in complicated meteorological systems. Complexity 2022, 2022, 4354198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liljedahl, A.K.; Kanevskiy, M.; Epstein, H.E.; Jones, B.M.; Jorgenson, M.T.; Kent, K. Transferability of the deep learning Mask R-CNN model for automated mapping of ice-wedge polygons in high-resolution satellite and UAV images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In Computer Vision-ECCV 2016: Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 9905, pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Wu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Miao, C. Position and morphology detection of mixed particles based on IPI and YOLOv7. Opt. Commun. 2023, 554, 130158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. In Computer Vision-ECCV 2024: Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 15089. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.H.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection Source. 38th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. NeurIPS 2024, arXiv:2405.14458. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, Z.; Zhai, T.; Xiao, Z.; Li, L. GPR-based high-precision passive-support fiber ice coating detection method for power transmission lines. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 30483–30493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.F.; Wang, Q.R.; Li, M. Electric equipment image recognition based on deep learning and random forest. High Volt. Eng. 2017, 43, 3705–3711. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.; Wang, B.; Li, M.; Dong, X.; Mao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, H. Edge intelligent perception method for power grid icing condition based on multi-scale feature fusion target detection and model quantization. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 754335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Jiang, X.; Hao, Y.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Li, R.; Luo, B. Recognition of natural ice types on in-service glass insulators based on texture feature descriptor. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2017, 24, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Yuan, M.; Lu, T.; Shivakumara, P.; Blumenstein, M.; Shi, J.; Kumar, G.H. Rotation invariant angle-density based features for an ice image classification system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 162, 113744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Shen, L.; Wu, D.; Duan, Y.; Song, Y. Research on transmission line ice-cover segmentation based on improved U-Net and GAN. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 221, 109405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wan, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, C. Research on detection of icing cover transmission lines under different weather conditions based on wide-field dynamic convolutional network LDKA-NET. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Dou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y. Ice thickness detection of transmission lines based on Cross-Guide-UNet. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaiki, R.; Jamali, A.; Rahem, A.; Shabani, M.; Barjenbruch, B.L. A metaheuristic-optimization-based neural network for icing prediction on transmission lines. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2024, 224, 104249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Duan, R. Research on an icing-thickness calculation model for power transmission lines based on KPCA and GWO. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 248, 111877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Lv, H.; Liang, Z.; Yi, J. Transmission line icing thickness prediction model based on ISSA-CNN-LSTM. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2588, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H.; Sun, H.; Zhao, H.; Wu, T. Ice cover prediction for transmission lines based on feature extraction and an improved transformer scheme. Electronics 2024, 13, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Chen, H.; Sun, S.; Guo, T.; Yang, L. Research on transmission line icing prediction for power system based on improved snake optimization algorithm-optimized deep hybrid kernel extreme learning machine. Energies 2025, 18, 4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretov, D.; Belko, A.; Mutalov, A. The dataset for a machine learning forecast model of an overhead power lines icing. In Proceedings of the International Russian Smart Industry Conference (SmartIndustryCon), Sochi, Russia, 24–28 March 2025; pp. 934–939. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H.M.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Wang, L. An intelligent method for fault situation in double-circuit transmission lines utilizing extreme learning machine. Electr. Eng. 2025, 107, 2051–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, D.; Wang, S.; Fan, Y.; Takyi-Aninakwa, P.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Fernandez, C. Enhanced multi-constraint dung beetle optimization-kernel extreme learning machine for lithium-ion battery state of health estimation with adaptive enhancement ability. Energy 2024, 307, 132723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Q. EDPNet: A transmission line ice-thickness recognition end-side network based on efficient dynamic perception. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Dou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y. EECNet: An efficient edge computing network for transmission line ice thickness recognition. Processes 2025, 13, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dou, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Guo, D. GMSA-Net: A transmission line ice thickness identification network based on global micro strip awareness. Sensors 2024, 24, 4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlman, J.C.; Landers, P. Present state-of-the-art of transmission line icing. IEEE Power Eng. Rev. 1982, PER-2, 20–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.S.; Song, W.; Wang, W.; Sun, T.; Huang, T.Z.; Cai, X.M. Study on blasting parameters of high voltage transmission line coated by ice. J. North Univ. China (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 39, 746–751. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.H.; Xue, K.Y.; Miao, L.L.; Li, H.T.; Guan, X.F.; Zhang, J.J.; Li, G.P. Dynamic response analysis of iced tower-line system due to blasting deicing. J. North Univ. China (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 40, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Chen, Y.; Huang, T.; Wang, M.; Huang, H. Electro-impulse de-icing (EIDI) test of aircraft wing leading edge. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Symposium on High Voltage Engineering, Xi’an, China, 21–26 November 2021; IET Conference Proceedings. pp. 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Alhassan, A.B.; Zhang, X.; Shen, H.; Xu, H. Power transmission line inspection robots: A review, trends and challenges for future research. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 118, 105862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, W.; Zhu, H. An efficient dynamic formulation for the vibration analysis of a multi span power transmission line excited by a moving de-icing robot. Appl. Math. Model. 2022, 103, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montambault, S.; Pouliot, N. The HQ LineROVer: Contributing to innovation in transmission line maintenance. In Proceedings of the IEEE 10th International Conference on Transmission and Distribution Construction, Operation and Live-Line Maintenance (ESMO), Orlando, FL, USA, 6–10 April 2003; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Guo, R.; Cao, L.; Zhang, F. Improvement of LineROVer: A mobile robot for de-icing of transmission lines. In Proceedings of the 2010 1st International Conference on Applied Robotics for the Power Industry, Montreal, QC, Canada, 5–7 October 2010; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Xian, H.X.; Qiao, G.; Wang, L.L.; Cheng, T.C.; Wu, H.Y. Structural design and simulation analysis of intelligent de-icing robots for high voltage transmission lines based on TRIZ theory. J. Mach. Des. 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.K.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, H.Y.; Xie, H.X. Design and research on the deicing robot for transmission lines. J. Chongqing Electr. Power Coll. 2024, 29, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.Q.; Du, L.; Han, W.H. Icing analysis of transmission lines considering the current heat. In Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference, Wuhan, China, 25–28 March 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Q/GDW 10716-2022; Technical Guide of Current Ice-Melting for Overhead Transmission Lines. State Grid Corporation of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Jiang, X.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, J.; Lei, Y. DC ice-melting and temperature variation of optical fiber for ice-covered overhead ground wire. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2016, 10, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Hou, Y.N. Application research of AC ice melting method in mountainous area of northern Guangdong. Telecom Power Technol. 2020, 37, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.G.; He, R. Engineering application and technical and economic comparison of DC de-icing device in 500 kV substation. Electr. Power Surv. Des. 2023, 11, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Z.; Zhang, Y. Realization of de-icing based on 12-pulse rectification for 500 kV transmission line. High Volt. Eng. 2012, 38, 3041–3047. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Wang, X.; Yao, Z.; Li, T.; Peng, Z. Circulating current suppressing strategy for MMC-HVDC based on nonideal proportional resonant controllers under unbalanced grid conditions. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.F.; Wang, W.; Tang, X.; Tang, C. A control method for modular multilevel AC/AC converter based the equivalent current decomposition model. J. Electr. Power Sci. Technol. 2021, 36, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P.F.; Liang, Y.Q.; Du, Y.; Bi, R.M.; Rao, C.L.; Han, Y. Development and testing of a 10 kV 1.5 kA mobile DC de-icer based on modular multilevel converter with STATCOM function. J. Power Electron. 2018, 18, 456–466. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.Q.; Zhou, Y.B.; Xu, J.Z.; Xu, S.K.; Zhao, C.Y.; Fu, C. Control strategy of DC ice-melting equipments for full-bridge modular multilevel converters. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2017, 41, 106–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, L.X.; Zhang, S.Q.; Wei, Y.D.; Li, X.Q.; Jiang, Q.R.; Li, M.R.; Li, W.R. DC traction power supply system based on modular multilevel converter suitable for energy feeding and de-icing. Csee J. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 10, 649–659. [Google Scholar]

- Zasypkin, A.; Shchurov, A. Capacitor protection of electromagnetic voltage transformers in dc ice melting schemes on overhead transmission lines. In Proceedings of the International Multi-Conference on Industrial Engineering and Modern Technologies (FarEastCon), Vladivostok, Russia, 6–9 October 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sadykov, M.; Garifullina, N.; Demkina, Y. Modernization of mobile installations for removing ice deposits on power transmission lines. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering, Applications and Manufacturing (ICIEAM), Sochi, Russia, 12–16 May 2025; pp. 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jourden, S. De-icer installation at Lévis substation on hydro Québec’s high voltage system. South Power Syst. Technol. 2009, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, A.G.; Ozgur, G.; Sevkat, E. Electrical resistance heating for deicing and snow melting applications: Experimental study. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2019, 160, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Z.; Li, B.; Zhang, H.X.; Fang, Z.; Jiang, Z.L. Application of new-type AC and DC de-icers in Hunan power grid. South. Power Syst. Technol. 2009, 3, 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.P.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Miao, D.; Tang, H.; Guo, H.D.; Zhang, X. Research on the application of sectional fixed DC ground wires de-icing method for 500 kV transmission lines. Electrotech. Appl. 2025, 44, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, W.G.; Liu, P.J.; Cui, R.J.; Zhao, H.; Xiang, H.B. Research on ice melting scheme for ground wires of ±800 kV UHV DC transmission lines under uninterrupted mode. Autom. Appl. 2025, 66, 240–244. [Google Scholar]

- Huneault, M.; Langheit, C.; St-Arnaud, R.; Benny, J.; Audet, J.; Richard, J.-C. A dynamic programming methodology to develop de-icing strategies during ice storms by channeling load currents in transmission networks. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2005, 20, 1604–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, Y.; Shu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, Q.; Wang, Q. Control scheme of the de-icing method by the transferred current of bundled conductors and its key parameters. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2015, 9, 2198–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Jiang, X.L.; Fan, S.H.; Meng, Z.G. Asynchronism of ice shedding from the de-iced conductor based on heat transfer. ET Sci. Meas. Technol. 2016, 10, 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Yan, B.; Wen, N.; Wu, C.; Li, Q. Study on jump height of transmission lines after ice-shedding by reduced-scale modeling test. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2019, 165, 102781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.Z.; Yan, B.; Mou, Z.Y.; Lv, X. Numerical investigation into torsional behavior of quad bundle conductors. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 36, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, S.; Tang, X.; Li, P.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wu, G. Effect of water droplets on the corona discharge characteristics of composite insulators in arid areas. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Electrical Materials and Power Equipment (ICEMPE), Guangzhou, China, 7–10 April 2019; pp. 467–472. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, F.H.; Farzaneh, M.; Jiang, X.L. Influence of AC electric field on conductor icing. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2016, 23, 2134–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.H.; Jiang, X.L.; Farzaneh, M. Influences of electric field of conductors surface on conductor icing. High Volt. Eng. 2018, 44, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Esmeryan, K.D. From extremely water-repellent coatings to passive icing protection-principles, limitations and innovative application aspects. Coatings 2020, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Pei, X.; Yu, B.; Zhou, F. Integration of self-Lubrication and near-infrared photothermogenesis for excellent anti-Icing/deicing performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 4237–4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najibi, H.; Mohammadi, A.H.; Tohidi, B. Estimating the hydrate safety margin in the presence of salt and/or organic inhibitor using freezing point depression data of aqueous solutions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 4441–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovin, K.; Dhyani, A.; Thouless, M.D.; Tuteja, A. Low-interfacial toughness materials for effective large-scale deicing. Science 2019, 364, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, J.; Jing, X.; Chen, H. Temperature self-regulating electrothermal pseudo-slippery surface for anti-icing. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 422, 130110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, T.; Schutzius, T.M.; Poulikakos, D. Imparting icephobicity with substrate flexibility. Langmuir 2017, 33, 6708–6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, C.; Emersic, C.; Rajab, F.H.; Cotton, I.; Zhang, X.; Lowndes, R.; Li, L. Assessing the superhydrophobic performance of laser micropatterned aluminium overhead line conductor material. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2022, 37, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitridis, E.; Lambley, H.; Tröber, S.; Schutzius, T.M.; Poulikakos, D. Transparent photothermal metasurfaces amplifying superhydrophobicity by absorbing sunlight. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 11712–11721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.H.; Jiang, G. Superhydrophobic coatings on iodine doped substrate with photothermal deicing and passive anti-icing properties. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 402, 126342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Xu, D.; Zhang, D.; Ma, L.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Chen, M.; Qian, H.; Li, X. A durable and photothermal superhydrophobic coating with entwinned CNTs-SiO2 hybrids for anti-icing applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 423, 130238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Y.; Han, J.; Li, Y.; Qin, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhong, X. Research on anti-icing performance of graphene photothermal superhydrophobic surface for wind turbine blades. Energies 2023, 16, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, W.; Kwon, Y.S.; Li, W.; Yao, S.; Huang, B. Solar deicing nanocoatings adaptive to overhead power lines. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2113297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinov, A.V.; Kostyukov, D.A.; Yasnaya, M.A.; Zvada, P.A.; Arefeva, L.P.; Varavka, V.N.; Zvezdilin, R.A.; Kravtsov, A.A.; Maglakelidze, D.G.; Golik, A.B.; et al. Oxide nanostructured coating for power lines with anti-icing effect. Coatings 2022, 12, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Y.F.; Zhu, L.M.; Li, R.Y.; Liu, B.S. Study on the preparation and properties of photothermal superhydrophobic coatings for ice-resistant transmission lines. New Chem. Mater. 2025, 54, 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Si, J.J.; Rui, X.M.; Liu, S.C.; Liu, L.; Yang, W.G. Stability analysis study on diameter-expanded conductor with fewer inner wires. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2022, 37, 3536–3546. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.K.; Yu, J.B.; Liu, Z.H.; Qin, Z.; Jiang, X.L.; Hu, Q. Comparison of icing between equivalent expanded diameter conductor and bundle conductor. High Volt. Eng. 2022, 48, 2698–2705. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, C.L.; Jiang, X.L.; Han, X.B.; Yang, Z.Y.; Ren, X.D. Anti-icing method of using expanded diameter conductor to replace bundle conductor. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2020, 35, 2469–2477. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.F.; Jiang, X.L.; Ren, X.D.; Li, Z.Y. Study on preventing icing disasters of transmission lines by use of eddy self-heating ring. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2021, 36, 2169–2177. [Google Scholar]

- Akhobadze, G. De-icing power transmission wires. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Actual Problems of Electron Devices Engineering (APEDE), Saratov, Russia, 24–25 September 2020; pp. 276–278. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, J.; Hu, Q.; Zheng, H.; Chen, Q.; Yang, G. Research on icing torsion suppression method of overhead single conductors based on dynamic balance of orthogonal moments. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2024, 39, 3398–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Research Focus | Methodology/Technique | Key Findings/Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yang et al. [35] | Detection of ice thickness | Axial tension measurement | The relative error is below 7% for the equivalent ice thickness (proposed method versus manual measurement). |

| Nusantika et al. [48] | Detection of icing cover | Integration of image restoration, filter enhancement and enhanced multi-threshold algorithm | The method achieved 90% measurement accuracy, with performance metrics of 97.72% accuracy, 96.24% precision, 86.22% recall, and 99.48% specificity. |

| Hu et al. [64] | Detection of icing cover | An optimized network SGAN_UNet composed by GAN and S_Unet | SGAN_UNet attains superior metrics (89.47% mIoU, 95.73% mPA, 92.31% F1-score) and a 1.10% mIoU gain over S_UNet. |

| Dong et al. [65] | Detection of icing cover | LDKA-NET (WFVC Net, Full-dimensional dynamic convolutional feature fusion network, and EM-DCA) | With a superior mAP@0.5 of 99.01%, the improved algorithm surpasses both the SSD and YOLOv5-L models by a clear margin (+4.81% and +3.11%, respectively). |

| Zhang et al. [66] | Detection of icing cover | CG-UNet (encoder–decoder architecture and CGM) | With optimal dataset and image scale scores of 0.934 and 0.938, the thickness detection error is constrained within 7.2%. |

| Snaiki et al. [67] | Prediction of the ice-to-liquid ratio | FFNN with metaheuristic optimizers | The metaheuristic optimizers consistently outperformed SGD. |

| Liu et al. [68] | Monitoring of ice thickness | KPCA, GWO, and SVM | The accuracy is 98.81%. |

| Ke et al. [70] | Monitoring of ice thickness | Feature extraction and improved Transformer scheme | The proposed algorithm is superior to all baseline methods under multiple features and parameters. |

| Li et al. [71] | Monitoring of ice thickness | Improved snake optimization algorithm and optimized deep hybrid kernel extreme learning machine | RMSE 0.057, MAE 0.044, R2 0.993. |

| Zhang et al. [77] | Monitoring of ice thickness | GMSA-Net (MSCM and GMAM) | Key performance metrics: 96.4% mIoU, 98.1% F1-Score, and <3.8% ice thickness identification error. |

| Reference | Research Focus | Methodology/Technique | Key Findings/Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hou et al. [98] | DC de-icing | DC traction power supply system suitable for energy feeding and de-icing | Efficient de-icing through energy recycling. |

| Wang et al. [118] | Anti-icing coating | Temperature self-regulating electrothermal pseudo-slippery surface | Key results: ~30% lower anti-icing energy use at 1.5 W/cm2; ~40% ice inhibition after 120 s at −40 °C. |

| Lian et al. [120] | Anti-icing surfaces | Superhydrophobic surfaces (Laser Micropatterned Aluminum) | Surfaces remained superhydrophobic after 1 year outdoors, with a post-16-week weekly contact angle loss of ~0.1° (static) and ~0.2° (hysteresis). |

| Zhang et al. [123] | De-icing coating | Durable photothermal superhydrophobic coating (CNT-Silica nanoparticle hybrid) | Water contact angle: 159.3°; complete photothermal de-icing in <60 s (onset: 5 s) under 808 nm NIR. |

| Gou et al. [124] | Anti-icing surfaces | Photothermal superhydrophobic surface (Graphene, fluorosilane-treated SiO2 solution, copper substrate) | Contact angle: 160.5°; maintained unfrozen droplets under 808 nm NIR laser (2 W/cm2). |

| Li et al. [125] | De-icing coating | Scalable solar-thermal icephobic nanocoating (Titanium nitride nanoparticle layer and dual-scale silica particles) | Temperature rise of 72 °C under 1 sun; high solar absorptance (90%) and low infrared emissivity (6%); rapid de-icing in 860 s and defrosting in 515 s at −15 °C. |

| Blinov et al. [126] | Anti-icing coating | Nanostructured coating (Solution of tetraethoxysilane and ammonia) | Tensile strength: 2385 N; Wetting contact angle: 130°; Ice accumulation: 0.52 ± 0.13 g; Voltage deviation: 0.5% at 100,000 Hz. |

| Wang et al. [127] | Anti-icing coating | Photothermal superhydrophobic coatings (Graphene and carbonblack, non-fluorinated n-octyltriethoxysilane) | Water contact angle: 158.3° ± 3.6°; Sliding angle: 4.6° ± 1.5°; Surface rapidly heats to 98.5 °C in 10 min, melting frozen droplets in 151 s. |

| Wang et al. [129] | Anti-icing expanded diameter conductor | Expanded diameter conductor replaces n (n = 4, 6, 8) bundle conductor | Identical transmission capacity, 60–70% less ice accumulation, and superior mechanical properties. |

| Huang et al. [131] | De-icing self-heating ring | Eddy self-heating rings made of ferromagnetic material | No ice forms on conductor with self-heating rings, reducing total ice mass by 18.38–30.61%. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Ju, Y. A Review of Transmission Line Icing Disasters: Mechanisms, Detection, and Prevention. Buildings 2025, 15, 3757. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15203757

Hu J, Liu L, Zhang X, Ju Y. A Review of Transmission Line Icing Disasters: Mechanisms, Detection, and Prevention. Buildings. 2025; 15(20):3757. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15203757

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Jie, Longjiang Liu, Xiaolei Zhang, and Yanzhong Ju. 2025. "A Review of Transmission Line Icing Disasters: Mechanisms, Detection, and Prevention" Buildings 15, no. 20: 3757. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15203757

APA StyleHu, J., Liu, L., Zhang, X., & Ju, Y. (2025). A Review of Transmission Line Icing Disasters: Mechanisms, Detection, and Prevention. Buildings, 15(20), 3757. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15203757