1. Introduction

Cultural heritage preservation and development have been at the center of global architectural conservation and practice [

1]. Museums safeguard the spiritual values of the past through the exhibition of artifacts, crafts, and intangible cultural heritage [

2]. They also serve as educational platforms that stimulate critical thinking and foster cultural identity [

3]. Understanding the interests and visiting habits of different groups can help museums tailor their exhibition content and services [

4]. Consequently, architects worldwide are committed to enhancing visitor experiences in museums with limited resources, whether through technological innovation or large-scale redevelopment [

5,

6]. Online interactions through social media further enrich the visitor experience [

7]. To support efficient renewal and design, it is essential to understand the environmental attributes that shape visitor experience and behavior.

In response to the dual demands of heritage protection and tourism development, site museums have emerged as a means to achieve authentic preservation, research, and exhibition of cultural heritage with an emphasis on sustainability [

8]. In recent years, research on visitors’ behavior and emotional experiences has become an interdisciplinary focus at the intersection of museum studies, human geography, and psychology. It mainly focuses on the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral interaction patterns of visitors within heritage site spaces, providing a basis for improving exhibition design and enhancing educational outcomes [

9]. Against this backdrop, understanding visitors’ experiences, especially their psychological and behavioral dimensions, has become a key to optimizing museum environmental design.

This study draws primarily on theories from environmental psychology, particularly the Attention Restoration Theory (ART), which posits that environments with attributes such as “fascination”, “extent”, and “compatibility” can effectively promote psychological restoration and positive emotional responses [

10]. Applying this theory to the museum context, it is particularly important to explore how the physical environment of museums, as a type of restorative environment, influences visitors’ behavioral and emotional experiences.

With the widespread adoption of digital technology, comment data generated by visitors on social media platforms have become a valuable dimension for understanding behavioral preferences and emotional experiences. The application of social media data analysis is already extensive in fields such as geography, urban park studies [

11], landscape and urban planning [

12], tourism management, and environmental research [

13]. Taking the Kimbell Art Museum as a case study, by collecting tourist reviews from travel websites to construct a database, and conducting visualization and multi-dimensional analysis, they developed a new evaluation framework for landscape-oriented public buildings. This framework compensates for the shortcomings of traditional evaluation methods and provides prospects for its application. Their findings also informed recommendations for crowd management and price regulation. Similarly, Zeng et al. [

14] used TripAdvisor reviews to integrate visitor feedback with assessments of museum functions, architecture, and landscape design, developing a novel evaluation method for landscape-type public buildings. Pung et al. [

15] applied an affective information processing framework to assess how discrete emotions like gratitude and regret shape authenticity perceptions at heritage sites, along with their subsequent impact on destination image and revisit intentions. Their findings from a heritage site in Sardinia confirm that gratitude can foster positive revisit intentions through enhanced perceptions of authenticity and place attachment.

Although aspects of the “environment–behavior–emotion” triad in cultural heritage museums have been explored, studies using social media data remain limited, and our understanding of how visitors perceive and experience these cultural settings is still incomplete. Existing research has enriched knowledge of museum experiences, but it lacks a systematic account of how environmental quality influences psychological responses. Current work remains fragmented. Studies of the environment–behavior nexus quantify spatial and behavioral patterns but give little attention to the underlying emotional drivers. Analyses of the environment–emotion link identify broad correlations yet seldom specify the environmental cues that elicit emotions or the associated behaviors. Research on the emotion–behavior relationship highlights co-occurring states but rarely traces their environmental triggers or clarifies which design features produce particular “emotion–behavior” combinations. This fragmented perspective has limited progress toward understanding the interactive dynamics of the triad. In particular, an integrated framework is still lacking to explain how museum environments act as stimuli, shape visitor behaviors, and influence psychological experiences. Addressing these pathways and mediating mechanisms represents an important direction for future research.

This study offers three key contributions to museum environmental design and practice. First, it introduces an innovative methodology that leverages social media data and natural language processing (NLP) to capture large-scale, spontaneous visitor feedback. Importantly, the proposed analytical framework is not bound to a specific cultural context or social media platform. Its structured approach to data processing, dimension construction, and relationship analysis can be adapted and applied to museums in other regions, utilizing local prevalent social media data (e.g., TripAdvisor, Twitter), thus offering a generalizable tool for cross-cultural comparative studies. Second, by focusing specifically on cultural heritage museums, the findings provide strong empirical evidence illuminating how cultural experiences shape public behavioral preferences. Finally, the study reveals and visualizes the operational pathways linking museum objects, visitor behaviors, and emotional experiences. Although not establishing strict causality, this analytical framework offers valuable data support and a foundation for exploring multivariate interaction mechanisms, thereby informing strategic design development and renewal for museum built environments.

2. Methods

2.1. Analytical Framework

In this study, the behavioral preferences of visitors to cultural heritage museums are examined through a systematic application of multi-stage text mining techniques, drawing on public visitor reviews from social media platforms such as Dianping and Weibo. A three-dimensional analytical framework is developed to capture the characteristics of heritage experiences, encompassing objects of interest, visiting behaviors, and cultural experience perceptions. Unstructured review texts are clustered using the LDA-Gibbs topic model, with manual coding employed to verify classification accuracy. This combined approach enables a multidimensional analysis of the mechanisms shaping visitor behavioral preferences in the context of cultural heritage sites (

Figure 1).

2.2. Study Area

To ensure the representativeness and generalizability of the findings, this study employed a stratified sampling strategy for case selection. Six cultural heritage museums were chosen based on a three-dimensional framework considering cultural region, administrative level, and primary function. This approach aimed to capture the diversity of visitor experiences across China’s major geographical and cultural spectra.

Firstly, regarding cultural and geographical representation, the cases span four distinct cultural regions that form a core transect of Chinese civilization: (1) Xinjiang Desert–Oasis Culture: Representing the multicultural interactions along the ancient Silk Road. (2) Sichuan Basin Culture: Exemplifying the unique and mysterious ancient Shu civilization of Southwest China. (3) North China Plain Culture: The heartland of Chinese civilization, featuring the Yellow River basin and the Grand Canal. (4) Jiangnan Waterfront Culture: Showcasing the refined aesthetic and water-town culture of southeastern China.

This selection ensures coverage from northwestern arid regions to southeastern humid zones, and from inland continental cultures to coastal-influenced traditions.

Secondly, in terms of administrative level and prestige, all selected sites are designated and managed as National Archaeological Site Parks or equivalent national-level museums under the National Archaeological Site Park Management Measures and other national regulations [

16,

17]. This indicates that they are among the most significant and well-managed heritage sites in China, receiving substantial state support and visitor attention. Focusing on this top tier minimizes variability due to management quality and resource disparity, allowing for a more focused examination of cultural and spatial influences on visitor experience.

Thirdly, the museums encompass a variety of core cultural themes and historical periods, as detailed in

Table 1. These include: Buddhist art and grottoes (Seven Star Buddha Temple), Neolithic settlement culture (Dahecun, Yangshao), Imperial industrial heritage (Imperial Kiln, Jingdezhen), Grand Canal transport heritage (Grand Canal Museum), Royal palace complexes (Southern Song Deshougong Palace), Bronze Age sacrificial civilization (Sanxingdui).

Finally, a practical criterion of high social media data availability was applied to ensure a sufficiently large sample of visitor comments for robust text mining. By integrating these dimensions cultural geography, administrative stature, and thematic diversity the selected cases provide a robust and strategically chosen sample for a systematic cross-regional comparison of visitor behavioral preferences in Chinese cultural heritage museums.

To ensure representativeness, this study selected six cultural heritage museums using a stratified framework based on cultural region, administrative level, and primary function. The cases cover four major cultural zones across China: (1) the Xinjiang Desert–Oasis Culture of the Silk Road; (2) the Sichuan Basin Culture, home to the ancient Shu civilization; (3) the North China Plain Culture, the heartland of Chinese civilization; and (4) the Jiangnan Waterfront Culture, known for its refined aesthetics. This selection captures a spectrum from northwestern arid to southeastern humid zones.

All selected sites are national-level institutions (National Archaeological Site Parks or equivalent), ensuring high management standards and cultural significance while minimizing confounding variables. As detailed in

Table 1, they represent diverse cultural themes, including Buddhist art, Neolithic settlements, imperial industry, canal heritage, royal palaces, and Bronze Age civilization.

A final criterion of high social media data availability ensured a sufficient sample for analysis. This multi-dimensional strategy provides a robust basis for cross-regional comparison of visitor preferences in major Chinese heritage museums (

Figure 2).

2.3. Data Sources

The data for this study were drawn from three major Chinese social media and online travel platforms: Ctrip (V8.85.4), Weibo (V15.10.1), and Dianping (V11.50.4). Ctrip, as a leading travel service platform, places strong emphasis on user-generated reviews, which are encouraged to ensure credibility and maintain competitiveness. Dianping, launched in 2003, is widely recognized as China’s foremost consumer review platform and one of the earliest independent third-party review sites globally. Sina Weibo, now the most influential social media platform in China, is characterized by its anonymity and immediacy of interaction, encouraging users to actively share opinions and emotions on public platforms [

18].

For this study, visitor comments related to six representative cultural heritage parks and museums were collected from these platforms. The data cover the period from 1 January 2016, to 30 July 2025. After systematic web crawling, cleaning, and screening, a total of 10,684 valid comments were retained for analysis. Sample data are presented in

Table 2.

2.4. Data Cleaning and Processing

Data collection was carried out simultaneously with the initial cleaning process. Data crawling was conducted using two approaches: the domestic website Bazhuayu and direct data extraction via the Requests and Selenium libraries in Python 3.7.0. The raw data were exported to Excel and subjected to multiple rounds of manual verification and refinement according to the following principles:

- (1)

elimination of garbled codes and non-text elements such as emoticons and hyperlinks;

- (2)

removal of meaningless special characters (e.g., ! # ¥ % …);

- (3)

de-duplication to retain unique records;

- (4)

exclusion of invalid comments with fewer than five characters or containing only emoticons;

- (5)

removal of redundant or repetitive content (e.g., “good, good, good” and other superlatives).

Following cleaning, the text was normalized, and high-frequency words related to visitor behaviors in cultural heritage parks and museums were extracted for preliminary coding. Comments were then categorized into three major dimensions: objects of concern, cultural experiences, and visiting behaviors. Within this framework, relevant nouns were classified as objects of concern, verbs and associated nouns as behavioral activities, and adjectives as indicators of cultural experience.

The final analytical framework (

Figure 3) was constructed through a two-stage, iterative process that integrated computational topic modeling with systematic manual content analysis.

- Stage 1:

Initial Topic Discovery via LDA Model

The LDA-Gibbs topic model (with alpha = 0.1, beta = 0.01, iterations = 100) was first applied to the cleaned corpus using the gensim library (version 3.8.3). This provided an unsupervised, data-driven identification of latent themes and their representative keywords, offering an objective starting point for understanding the broad content structure of the reviews.

- Stage 2:

Framework Refinement through Consensus-Based Manual Coding

The output from the LDA model served as the foundational input for the subsequent manual coding phase. This phase was conducted by two researchers following a consensus-based protocol:

Familiarization and Thematic Review: The researchers independently reviewed the LDA-generated topics and keywords alongside a large sample of raw comments. This step allowed for the contextual interpretation of the LDA topics and the identification of nuanced themes not fully captured by the model. Consensus Development and Codebook Formulation: The researchers met to compare their interpretations. They reconciled the LDA output with their qualitative insights, discarding, merging, or splitting topics as necessary. Through in-depth discussion, they defined clear category boundaries and collaboratively formulated a structured coding codebook.

Application and Finalization: The preliminary codebook was applied to further data subsets. Any ambiguities were discussed and resolved, leading to the finalization of the three-level indicator framework. The researchers then applied this final framework to the entire dataset through continuous consultation to ensure consensus coding for all data. This hybrid approach leveraged the scalability of LDA for initial theme discovery and the interpretative rigor of consensus-based qualitative analysis to build a valid and reliable framework grounded in both data patterns and deep textual understanding.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study utilizes publicly available, anonymized user-generated content from social media platforms. The data collection process adhered to the terms of service of the respective platforms (Dianping, Weibo, Ctrip). All comments were collected at an aggregate level, and no personally identifiable information (PII), such as usernames, real names, or contact details, was extracted or analyzed. The analysis focuses on the textual content and semantic patterns, ensuring the privacy and anonymity of all users. This research follows the guidelines for internet-mediated research outlined by the AoIR (Association of Internet Researchers) guidelines and was conducted for academic purposes, without any commercial intent.

3. Results

Analysis of word frequencies across the three indicator categories revealed that objects of concern were mentioned most frequently, appearing 25,575 times and accounting for 54.43% of all references. This was followed by excursion activities, with 12,297 mentions (26.17%), and cultural experience, with 9115 mentions (19.4%). The substantial number of references reflects both the popularity of cultural heritage parks and museums and the fact that visitors’ post-visit comments tend to emphasize descriptions of objects of interest, such as relics, cultural elements, and historical features, as well as excursion activities, including clocking in, taking photographs, and touring.

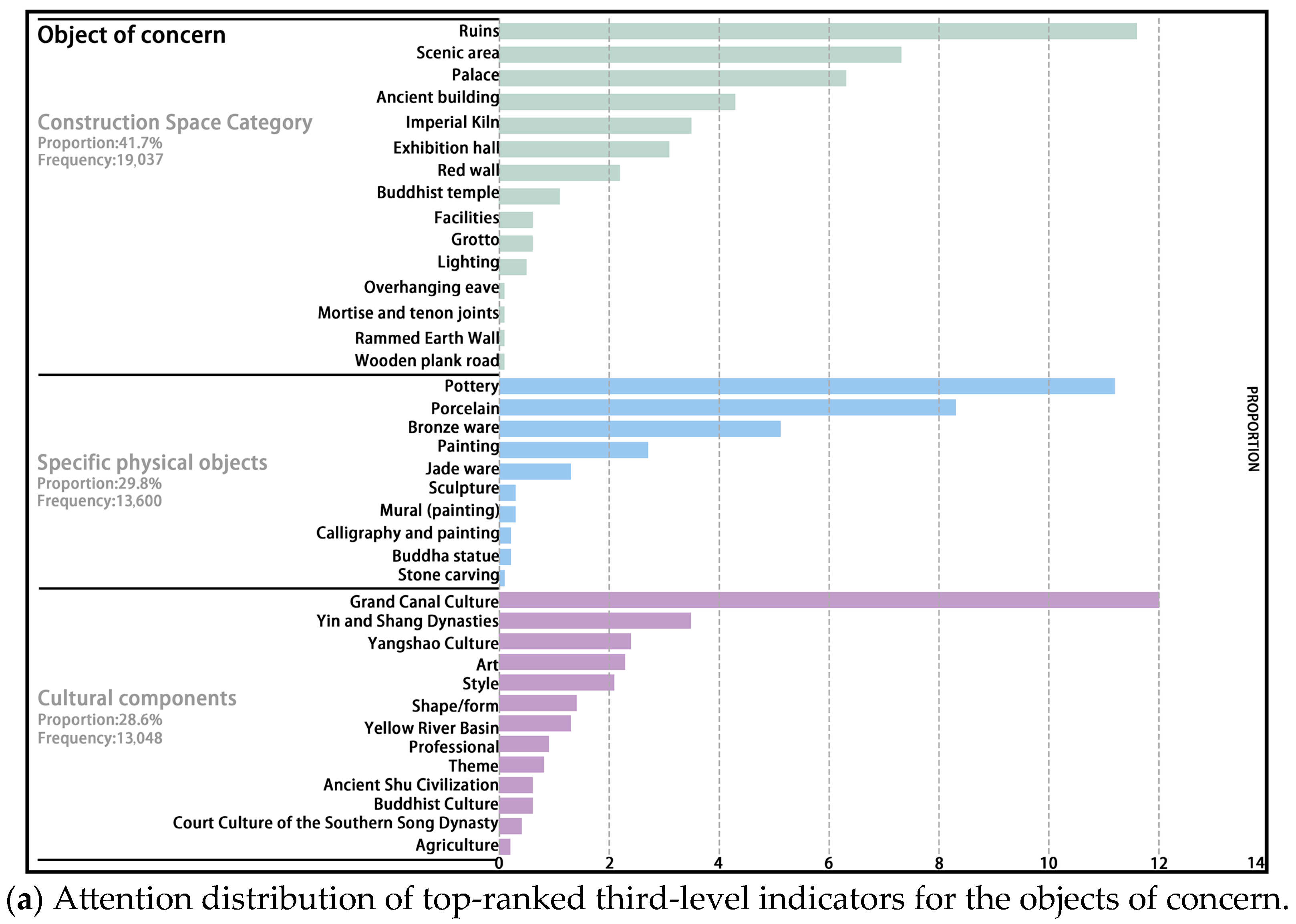

The three primary categories of objects, behaviors, and emotions were further divided into secondary and tertiary indicators, the distribution of which is shown in

Figure 4.

3.1. Attention to Object Analysis

The analysis of vocabulary data in the object category (

Table 3) indicates that the cognitive structure of site museum visitors follows a historical perception pattern mediated by spatial entities. Within this category, spatial settings account for 41.7% of references, specific physical objects for 29.8%, and cultural components for 28.6%. The ten tertiary indicators receiving the highest levels of attention include ruins, scenic spots, palaces, ancient buildings, imperial kilns, exhibition halls, red walls, Buddhist temples, facilities, and grottoes.

These results suggest that visitors’ historical understanding is strongly mediated by spatial entities, which serve as the primary anchors of perception. Spatial features such as ruins, scenic spots, and palaces emerge as the most prominent elements, underscoring visitors’ sensitivity to original remains and their ability to stimulate historical imagination through physical carriers such as rammed earth walls and flying eaves. Specific physical objects, representing 29.8% of references, rank second in importance and demonstrate a pronounced everyday orientation: pottery, porcelain, and bronze receive considerable attention, while religious artworks such as Buddha statues and frescoes attract comparatively less interest. This indicates that visitors tend to engage with history through material evidence of daily life rather than through religious or symbolic artifacts.

Although cultural components occupy the smallest share at 28.6%, they reveal a marked trend toward cultural symbolization. The Grand Canal culture stands out as a particularly salient cultural reference, while abstract concepts such as art and style also appear frequently, suggesting that visitors seek to distill tangible cultural symbols into broader interpretive labels. Variations in attention to different regional civilizations, such as the Yinshang and Southern Song cultures, further highlight a public demand for diverse forms of historical knowledge. Overall, the visitor’s trajectory of understanding follows a clear sequence: first, the capture of historical traces embedded in spatial forms; second, the visualization of historical narratives through everyday artifacts; and finally, the condensation of meaning through cultural symbols.

3.2. Analysis of Tour Behavior

Analysis of behavioral category vocabulary data (

Table 4) shows that basic experiential behaviors accounted for the largest share of visitor engagement in heritage museums (41.4%), followed by service support behaviors (35.7%), while in-depth cognitive behaviors represented the smallest proportion (22.9%). The ten most frequently mentioned tertiary indicators across the three categories were listening to a lecture, standing in line, making a reservation, visiting/viewing, parking, clocking in, walking, entering, educating/learning, and playing.

Interactions within museums connect individuals, social relations, and culture, allowing museums to transcend the role of mere repositories and instead become dynamic spaces that meet needs, sustain connections, and coexist with public life [

19].

Within the basic experiential category, visiting and viewing were the most common activities, accounting for 9.4% of comments, often accompanied by praise for the scenery, descriptions of weather conditions, and expressions of emotion. Check-in represented 7.8%, reflecting the democratization of cultural consumption in the digital era, where visitors actively participate in the production and dissemination of cultural meaning through low-threshold, high-dissemination activities. Walking and entering were also frequent behaviors, accounting for 7.4 and 6.1%, respectively. Leisure activities such as playing (4.2%) and shopping or purchasing creative products (3.8%) highlight the role of heritage sites as cultural consumption spaces. Taking photographs, accounting for 1.2%, was the primary means through which visitors constructed personal identity markers. Dining, stamping, and VR/AR interactions were the least frequently mentioned activities, each accounting for less than 1%.

For service support behaviors, queuing was the most frequently cited concern (12.8%), underscoring the importance of on-site management. Management-related terms such as reservation (10.2%), parking (8.2%), and code scanning (0.8%) further reflect the institutionalization of heritage visits in the digital era. In terms of transportation modes, public transit, self-driving, and taxis were most commonly reported by visitors.

3.3. Analysis of Cultural Experience Feelings

Analysis of vocabulary data in the cultural experience category (

Table 5) shows that spiritual engagement accounts for 43.0% of references, sensory pleasure for 34.8%, and negative feelings for 22.2%. The ten most frequently mentioned tertiary indicators across these three categories were beautiful, long queue, worthwhile, mysterious, shocking, interesting, like, unique, comfortable, and marvelous.

The findings suggest that visitors generally hold a positive impression of heritage museums. Within the spiritual engagement dimension, 2462 comments described the museums as worthwhile (17.1%), while mysterious (15.2%), shocking (6.2%), and unique (3.5%) were also common. These evaluations indicate the value of cognitive stimulation and innovation evoked by the historical settings. In contrast, terms such as educational significance (0.4%), awe (0.3%), deep impression (0.3%), and sublimation (0%) received limited attention, revealing shortcomings in the transmission of deeper cultural values through the museum experience.

In the sensory pleasure dimension, beautiful dominated with 20.6% of all responses, reflecting a strong, almost instinctive reaction to visual aesthetics. Interesting (5.5%) and like (4.5%) emerged as basic pleasure factors, while comfort (1.7%), wonder (1.5%), and tranquility (0.9%) were also present, though to a lesser extent.

Negative feelings were most strongly associated with long queues (18.6%), followed by tired (1.4%), crowded (0.8%), disappointing (0.5%), and confusing (0.3%). These responses highlight management challenges, including congestion and insufficient open space. Long queues, in particular, emerged as the most frequent negative issue, underscoring problems of overcrowding and extended waiting times during peak periods. Some visitors also described their experiences as boring, monotonous, or not good, suggesting that overly high expectations and limited variety in exhibition formats contributed to dissatisfaction.

3.4. Relationship Analysis of Objects, Behaviors and Feelings of Cultural Experience

3.4.1. Analysis of the Relationship Between Objects of Concern and Feelings of Cultural Experience

The correspondence between objects of concern and cultural experience indicators is illustrated in

Figure 5, revealing a clear hierarchy: built environment elements show the strongest correlation, followed by cultural components, while specific physical objects exhibit the weakest associations. This order of prominence is detailed as follows: sites, scenic areas, ancient buildings, palaces, exhibition halls, bronzes, Grand Canal culture, imperial kilns, porcelain, and style.

Architectural environments serve as the core medium for deep emotional experiences. Spatial markers such as ruins, scenic spots, ancient buildings, and palaces are strongly associated with in-depth responses like a sense of mystery, worthwhileness, and amazement. In contrast, functional spaces like exhibition halls and imperial kilns show weaker links to feelings of interest and comfort. Notably, technical architectural terms (e.g., rammed-earth walls) are predominantly tied to negative impressions like monotony, while negative feelings of crowding and fatigue are clearly linked to management-intensive spaces such as exhibition halls and scenic areas.

Although less frequent, abstract cultural components play a crucial and intense role. Elements such as Grand Canal culture and style are prominently correlated with profound experiences of mystery and shock. Other components, including Yin-Shang culture and art, are linked to awe and memorability, whereas themes like Buddhist culture show weaker interpretive value and emotional resonance. Specific physical objects exhibit an evident aesthetic bias. Three-dimensional artifacts such as bronzes and porcelains are primarily associated with superficial aesthetic pleasure, such as beauty and liking. In comparison, flat remains like murals and stone carvings exhibit only weak associations with emotional responses, reflecting a generally lower level of affective engagement.

3.4.2. Analysis of the Relationship Between Visiting Behavior and Objects of Concern

Figure 6 reveals the correspondence between touring behaviors and objects of concern. The analysis shows a clear hierarchy in the strength of these associations: basic experiential behaviors exhibit the strongest links, followed by in-depth cognitive behaviors, while service support behaviors demonstrate the weakest correlations. This hierarchy is further detailed in a descending order of association strength for specific behaviors: visiting/viewing, education, recommending, listening to lectures, discovering, inheriting, making reservations, walking, taking photographs, conducting research, and entering.

Within the basic experiential category, behaviors such as visiting/viewing, taking photographs, and check-in activities are strongly connected with ruins, scenic areas, and palaces, as indicated by thicker lines. This suggests that a substantial proportion of visitors engage with the heritage site primarily through these direct experiential activities.

In contrast, in-depth cognitive behaviors, such as education/learning, listening to lectures, and conducting research, demonstrate stronger connections with cultural elements such as Grand Canal culture, Yin-Shang culture, and Buddhist culture. The relative width of these associations highlights that a significant segment of visitors actively engages with these cultural themes through structured learning and interpretive activities.

Conversely, service-related behaviors, including queuing, parking, and making reservations, are represented by thinner lines, reflecting their weak correlation with any specific objects. This indicates that their experience is largely independent of the exhibits themselves, and within the overall experience framework, these service-related activities are not dominant modes of engagement.

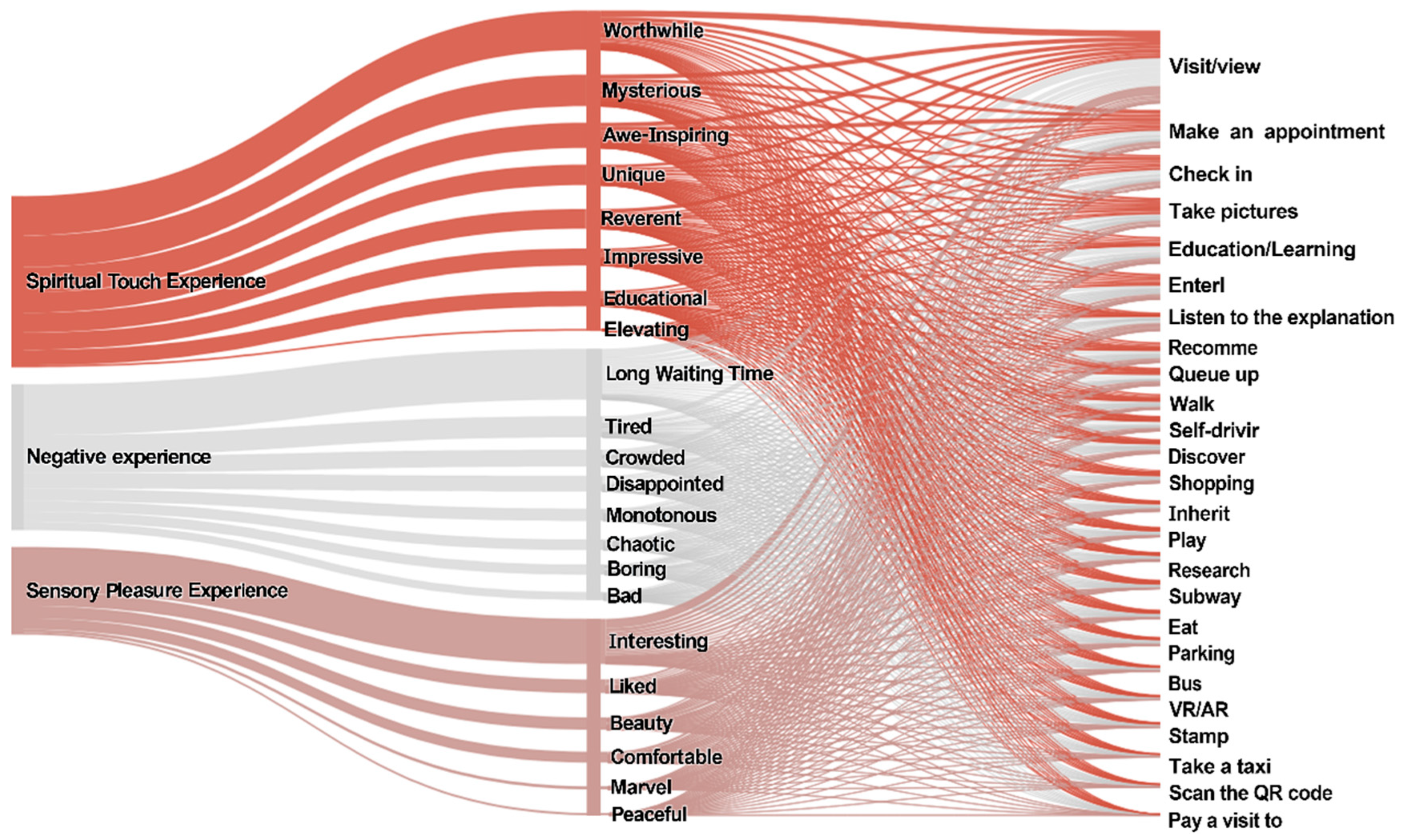

3.4.3. Analysis of the Relationship Between Cultural Experience Feelings and Excursion Behavior

The Sankey diagram in

Figure 7 illustrates how specific behaviors trigger experiential feelings, revealing a clear hierarchy: spiritual engagement has the strongest link to behaviors, followed by negative feelings, with sensory pleasure being the weakest. This is further detailed by the most prominent feelings in descending order: long queue, interesting, worthwhile, mysterious, marvelous, tiredness, unique, awe, impressive, crowded, and disappointment.

Negative experiences are highly concentrated and management-related. The feeling of “long queues”—the most prominent negative impression—stems almost entirely from “queuing” and “making reservations,” as shown by a thick data flow. Other negatives like “tiredness” and “crowding” also tie closely to these processes.

Spiritual engagement arises from diverse meaningful interactions. Feelings like “a sense of mystery” and “a sense of worth” are the most frequent deep impressions, strongly linked to both basic behaviors (e.g., “visiting/viewing,” “taking photos”) and cognitive behaviors (e.g., “listening to explanations”). “Listening to explanations” is a key catalyst, associated with multiple positive feelings, highlighting the role of interpretation.

Sensory pleasure is widespread but less intense. Feelings like “a sense of beauty” and “interest” connect to behaviors like “visiting” or “check-in,” but with thinner data flows, indicating more superficial engagement. “Making reservations” itself can reinforce cultural identity for some.

3.5. Comparative Analysis of Museums Across Cultural Zones

In this chapter, the six museums under study are grouped into four cultural regions based on cultural subdivisions: the Xinjiang Desert–Oasis culture (Seven Star Buddhist Temple Ruins Museum), the Sichuan Basin culture (Sanxingdui Ruins Museum), the North China Plain culture (Grand Canal Museum and the National Archaeological Site Museum of Dahecun), and the Jiangnan Waterfront culture (Southern Song Dynasty Deshougong Ruins Museum and Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum). The comparative analysis is structured along four dimensions: physical perception and architectural aesthetics, cognitive understanding and educational value, emotional connection and resonance, and spiritual sublimation and aesthetic significance.

3.5.1. Architectural Aesthetics Dimension

This study analyzes the data across both regional and museum dimensions through bar chart comparisons (

Figure 8a), highlighting the distributional characteristics of attention to architectural aesthetics under different contexts. At the regional level, the results show that attention to architectural aesthetics is highest in the Jiangnan Waterfront cultural region (0.35%) and lowest in the Sichuan Basin (0.06%), with the Xinjiang Desert–Oasis culture (0.25%) and the North China Plain culture (0.22%) falling in between. These findings reflect the varying degrees of attention attributed to different cultural regions.

At the museum level, the Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum receives the greatest attention (0.37%), followed by the Seven Star Buddhist Temple Ruins (0.25%), the Southern Song Deshougong Ruins Museum, and the Dahecun National Archaeological Site Park (both 0.32%). The Sanxingdui Museum records the lowest attention (0.06%). From the macro-regional scale to the micro-institutional level, the results reveal a clear hierarchy in the distribution of attention to architectural aesthetics, providing an empirical basis for further investigation into how cultural background and architectural characteristics shape public perception.

The prominence of the Jiangnan region reflects its architectural integration with water systems, while the Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum benefits from innovative design and its unique role as a cultural symbol—both of which contribute to heightened aesthetic appreciation. In contrast, the low levels of attention in the Sichuan Basin and the Sanxingdui Museum suggest the need to further highlight regional architectural features and enhance exhibition and communication strategies to strengthen aesthetic value.

3.5.2. Educational Value Dimension

A comparative analysis of the educational value of cultural regions and individual museums was conducted (

Figure 8b). At the regional level, the Sichuan Basin registers the highest proportion of attention to educational value (1.04%), making it the most prominent among the four cultural regions. The North China Plain follows with 0.9%, while the Jiangnan Waterfront culture (0.7%) and the Xinjiang Desert–Oasis culture (0.6%) rank lower.

At the museum level, the Dahecun National Archaeological Site Park shows the highest rating for educational value (1.32%). The Sanxingdui Museum (1.04%) and the Southern Song Deshougong Ruins Museum (0.92%) occupy intermediate positions, while the Seven Star Buddhist Temple Ruins (0.62%), the Grand Canal Museum in Beijing (0.76%), and the Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum (0.46%) fall toward the lower end of the scale.

Although the Sichuan Basin demonstrates a leading position in terms of educational value at the regional level, performance across museums within the region remains uneven. This highlights the need to further explore pathways for transforming regional cultural resources, while optimizing both the content and formats of museum education. Such efforts would enhance the dissemination and impact of cultural and educational value and promote the integrated development of regional cultural heritage transmission and the educational function of museums.

3.5.3. Emotional Resonance Dimension

The distribution of emotional resonance intensity across cultural heritage museums (

Figure 8c) shows that, at the regional level, the Sichuan Basin registers the highest proportion of attention (3.96%). The remaining cultural subregions follow in order: the Jiangnan Waterfront culture (3.71%), the North China Plain culture (3.62%), and the Xinjiang Desert–Oasis culture (3.42%).

At the museum level, the Sanxingdui Museum records the strongest emotional resonance (3.96%), followed by the Southern Song Deshougong Ruins Museum (3.75%). The Imperial Kiln Museum of Jingdezhen (3.67%) and the Grand Canal Museum in Beijing (3.68%) display similar levels, while the Dahecun National Archaeological Site Park (3.56%) ranks slightly lower. The Seven Star Buddhist Temple Ruins Museum shows the weakest resonance, with 3.42%.

These results indicate that the intensity of emotional resonance is unevenly distributed across museums and is largely determined by the cultural qualities embodied in each site—such as mystery, wonder, and aesthetic value—and by the institution’s ability to translate these qualities into meaningful visitor experiences. The Sichuan Basin, represented by the Sanxingdui Museum, stands out for its unparalleled sense of mystery and uniqueness, resulting in its higher proportion of emotional resonance. This case provides an important reference for how other museums might identify and amplify their own distinctive sources of emotional value.

3.5.4. Aesthetic Value Dimension

The distribution of aesthetic value (

Figure 8d) shows that, at the regional level, the Jiangnan Waterfront registers the highest proportion of attention in the aesthetic dimension (0.59%). The other cultural regions follow in order: Xinjiang Desert–Oasis culture (0.53%), North China Plain culture (0.49%), and Sichuan Basin culture (0.36%). Visitors’ aesthetic evaluations of heritage site museums are jointly shaped by the cultural origins of each region, the immediacy and universality of aesthetic expression, and the quality of contemporary architectural and landscape design. Accordingly, the Jiangnan Waterfront culture, with its mature aesthetic tradition, receives the highest level of attention.

A comparison of the mean values of aesthetic attention across individual museums further clarifies these differences. The Imperial Kiln Museum of Jingdezhen ranks first, with a mean share of 0.68%. It is followed by the Dahecun Ruins Museum (0.60%), the Seven Star Buddhist Temple Ruins (0.53%), the Deshougong Palace Ruins Museum (0.50%), the Grand Canal Museum (0.37%), and the Sanxingdui Museum (0.36%). These findings demonstrate how symbols, memories, and values internalized within regional cultures create systematic differences in how visitors perceive and rank aesthetic forms. At the same time, institutional attributes—including collections, exhibition halls, and display strategies—also influence aesthetic outcomes.

Strengthening cultural communication and aesthetic education thus requires attention to both regional cultural commonalities and the specific attributes of individual museums. Enhancing the aesthetic presentation of heritage carriers can improve visitor experiences and foster the transmission of aesthetic values and cultural identity.

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Narrative and the Architecture of Mystery

This study indicates that the “mysterious” experience in the cultural heritage environment is not a purely psychological phenomenon, but rather a result proactively constructed by spatial design. The sense of historical authenticity is closely associated with the materiality of relics and structures as well as the sense of spatial presence; in contrast, cognitive uncertainty often arises from the spatial sequences and narrative gaps intentionally or unintentionally created in exhibition layouts, which is consistent with the environmental psychology model [

20]. Specifically, historical traces such as rammed earth textures and foundation structures can stimulate visitors’ imagination, while macro symbols like the Ancient Shu Civilization and the Grand Canal Culture create cognitive gaps through their unsolved mysteries. These two aspects together form the foundation for the perception of authenticity. However, in the context of architecture, the power of unsolved cultural symbols (e.g., the Ancient Shu Civilization) stems not only from their conceptual connotations but also, more importantly, from the imaginative spatial context in which they are situated [

21]. This also supports Smith’s [

22] view that narrative gaps enhance the desire for exploration. Therefore, spatial design plays a core role in planning an experiential journey from “unknown” to “revealed”.

4.2. The Spatial Dimension of Educational Encounter

The identified stratification of educational behaviors—characterized by the dominance of superficial information reception and insufficient in-depth engagement—is directly associated with the spatial design approaches employed in museums. Spaces designed for linear, one-way communication, which are marked by static exhibitions and directional pathways, encourage passive learning. This stands in contrast to the concepts of “embodied learning” [

23] and knowledge co-creation [

24], both of which require spatially integrated interactive environments. The success of immersive scenarios in transforming artistic interpretation [

25] highlights the shortcomings of most current museums: for instance, their failure to convert abstract cultural themes into perceptible, narrative-driven experiences through spatial design. Therefore, the transition toward a “cultural production” model represents a spatial and architectural challenge.

4.3. Designing for the Body: Sensory Engagement and Spatial Experience

The interaction between bodily perception and cultural symbols underscores the significance of spatial experience. The “embodied cognition theory” [

26] finds expression in architecture: physical movement through space and engagement of multiple senses can transform abstract history into perceptible continuity. However, this aligns with the conclusion drawn by Zhan et al. [

27], which states that “sensory separation leads to disconnection of meaning”—that is, when divorced from cultural context, the perception of “beauty” remains at a superficial level; visual symbols such as isolated cornices and bronze decorations rarely evoke a sense of cultural identity. This contradicts the ideal of “cross-sensory meaning transmission” [

9], indicating that exhibitions need to better integrate space and senses to convert craftsmanship values (e.g., mortise-and-tenon joints) into experiential sentiments like “awe”.

4.4. Spatial Management and Narrative Failure as Primary Design Flaws

The most prominent negative experiences, such as “long queues” and “boredom,” are fundamentally issues of spatial planning and architectural narrative. Queues represent a failure in the design of visitor flow and the integration of digital management systems within the spatial envelope, exemplifying the “digital paradox” [

28]. Evidence on ineffective movement patterns [

24] reinforces that this is an architectural problem solvable through intelligent spatial management. Similarly, “boredom” often results from poor spatial narrative: a failure to use architectural elements (volume, light, sequence) and interpretive design to translate professional symbols into engaging stories [

22]. The lack of adequate rest facilities, which contributes to cognitive fatigue [

29], is a further oversight in the humane design of museum spaces, exacerbating museum fatigue.

4.5. Systematic Comparison with Similar Studies

This study advances social media-based heritage research by providing a unified framework that integrates fragmented findings. Unlike Wilken’s [

30] focus on behavioral motivations, our model systematically links specific behaviors (e.g., photo-taking) to the objects that trigger them (e.g., ruins) and the resulting emotions (e.g., awe), thereby mapping the “action-to-emotion” pathway. It extends affective studies like Pung et al. [

15] beyond comparing discrete emotions, to dissect the functional relationships between authenticity, place attachment, and revisit intentions across visitor groups. Furthermore, while aligning with Melton’s [

31] concept of “museum fatigue,” we identify poorly designed digital tools as a potential modern exacerbating factor.

4.6. Recommendation and Limitations

Based on the empirical findings, this study proposes phased design strategies for optimizing the spatial and experiential quality of cultural heritage parks and museums. These recommendations translate behavioral and emotional patterns into architectural and narrative interventions, categorized into short-term and medium-to-long-term actions.

Short-term strategies prioritize spatial and circulation improvements. To address issues such as “long queues” and “crowding,” it is critical to integrate intelligent visitor management with architectural layout. For instance, a digital booking system can be paired with suggested itineraries that sequence movement from high- to low-density zones—akin to the Guggenheim Museum’s spiral ramp, which naturally directs flow. Real-time data can also be used to dynamically adjust access to auxiliary spaces, alleviating congestion. Furthermore, thematic exploration should be embedded into the physical environment. Architecturally integrated trails—using flooring, lighting, or spatial cues to guide visitors—can deepen engagement, as demonstrated by the V&A Museum. Location-aware augmented reality can also enrich interpretation without disrupting the spatial narrative.

Medium-to-long-term strategies focus on narrative depth and sensory authenticity. Design should amplify the “mystery” and “awe” associated with spatial relics through narrative-driven sequences. For example, a ruin’s pathway might transition from confined passages to open vistas, enhancing the drama of discovery. Immersive media, such as theaters, should be carefully integrated as defined episodes within the spatial journey—similar to teamLab Borderless’s calibrated environments—to support rather than overshadow authentic heritage. Finally, spatial ambiance should be tailored to diverse visitors. Zoning can create dedicated areas such as hands-on discovery labs for children or quiet contemplation spaces with multi-language guides, emulating the minimalist, universally accessible design of Naoshima Art Island.

A key limitation of this study lies in its reliance on the content of user comments found on social media platforms. However, social media data analysis has now become a mature and validated methodology within research fields such as cultural tourism and architectural environment optimization [

32,

33,

34]. Although platform privacy policies restrict access to demographic details of commenters—such as age, gender, and educational background—this has minimal impact on the core research findings. This study primarily focuses on universal correlations between visitor behavioral preferences, environmental perceptions, and emotional experiences–such as how spatial relics evoke psychological resonance through authentic immersion, or how cultural symbols establish connections with cognitive gains–rather than demographic-level variations.

The substantial sample (N = 10,684) from multiple platforms (Ctrip, Weibo, Dianping) enhances representativeness and, by the law of large numbers, mitigates the impact of missing demographics. The primary structural bias is the self-selection of younger, digitally active users, potentially underrepresenting older or less proficient groups. However, this has limited effect on our core findings, as the identified patterns—such as the focus on spatial relics—are universal visitor trends, not demographics-specific. Future work should employ mixed methods, integrating surveys and interviews to further strengthen generalizability.

Secondly, regarding the manual coding process, we employed a rigorous, iterative, and consensus-based approach to establish the analytical framework. However, a formal quantitative measure of inter-coder reliability (e.g., Cohen’s Kappa) was not calculated. Future studies should incorporate such reliability metrics during the codebook development phase to further strengthen the methodological robustness.

5. Conclusions

Based on social media comment data, this study systematically examined the behavioral preferences and experiential perceptions of visitors to cultural heritage museums, and revealed the intrinsic relationships among objects, behaviors and experiences.

The main findings are as follows: (1) Visitor’ attention mainly focuses on spatial design and architectural elements, reflecting a high sensitivity to historical authenticity. This tendency promotes cultural cognition through direct contact with physical relics and establishes a fundamental connection between spatial heritage attributes and cognitive engagement. (2) Visitor behaviors show an obvious hierarchical structure: Basic experience activities are dominant, highlighting the museum’s social function as a cultural and leisure venue; while in-depth cognitive behaviors occur less frequently, they are closely related to the museum’s role as an informal education platform. (3) Emotional experiences are predominantly positive, often characterized by perceptions such as a sense of mystery, value, and aesthetic appreciation. However, spatial and facility management issues—such as overcrowding, prolonged queues, and inefficient visitor flow—as well as monotonous narrative approaches, significantly de-tract from the overall experience. (4) A structured correspondence exists among objects of attention, behaviors, and experiences. For instance, the spatial environment stimulates visitation and photo-taking behaviors, evoking feelings of mystery and awe; cultural elements promote interpretive and research-oriented actions, fostering perceptions of educational value; specific architectural and exhibit designs directly trigger sensory appreciation, generating aesthetic and pleasurable experiences. Although the overall experience tends to be positive, deficiencies in spatial planning, facility management, and narrative design remain considerable. (5) Cross-cultural comparison further highlights differences in architectural aesthetics, educational value, emotional resonance and aesthetic perception across regions, underscoring the decisive role of cultural context in shaping museum experiences.

This study presents a standardized “Objects–Behaviors–Experiences” framework for analyzing visitor experiences via social media data, offering a transferable tool for global heritage institutions. While the specific cultural elements (e.g., “Grand Canal culture”) are local, the analytical structure for connecting them to behaviors and emotions is universally applicable. This method, underpinned by adaptable NLP techniques, provides a replicable and low-cost pathway for conducting large-scale, cross-cultural post-occupancy evaluations of spatial and narrative design.

This study not only develops a framework for evaluating visitor behavior in heritage museums using social media data, but also provides empirical evidence and practical guidance for the sustainable revitalization of heritage spaces, the design-informed renewal of spatial practices, and the enhancement of museum experiences through improved architectural and facility management.