1. Introduction

The use of community treatment orders (“CTOs”) specifically for people with mental illness remain widespread in New Zealand and other jurisdictions. This is despite a range of concerns that include: (i) challenges from a holistic recovery philosophy and alternative cultural perspectives being applied to policy and models of service delivery and (ii) a new human rights framework (United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities) and (iii) contested international evidence of CTO (clinical) effectiveness and social benefit.

We acknowledge there are multiple factors across different levels of New Zealand society that are influencing high and increasing rates of CTOs and disparity between population groups, most marked for indigenous New Zealanders (Māori). In this paper, we propose to focus on the CTO production process itself. CTOs made under the New Zealand Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992 (“MHAct”) are part of a medical and legal procedure that is one component of a mental health structure existing within a society made up of individuals living in a “complex net of influences” (

Gluckman and FRS 2017, p. 3). With the Government indicating political will for new ways of approaching mental health, including an interest in making changes to the existing MHAct framework, how do we make sense of all this complexity in the forces driving and restraining the production of CTOs?

1In this paper, we suggest an answer lies in finding a way to apply the assemblage concepts developed by Deleuze and Guattari. We see merit in proposing that the existing medical and legal procedure that makes and re-makes CTOs is an assemblage—different arrangements and combinations of multiple elements such as processes, documents, physical spaces, participants and different bases of knowledge that are held together or changed through constant, complex influences. Our aim is to examine Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of assemblage and explain its key components by applying it to a constructed CTO scenario, supplemented with examples from the existing literature of concerns about human rights, indigenous population disparity and clinical effectiveness, that we argue are destabilising influences on the existing CTO practices.

We begin by presenting a constructed scenario to illustrate how CTOs are commonly made in New Zealand. This is followed by a description of relevant provisions in the MHAct and aspects of the legal and organisational framework that produces CTOs. We identify problems from the literature of high, increasing and disproportionate use of CTOs and link these to destabilising influences insofar as they call for constraint or reduction in the use of CTOs. We then set out key concepts in assemblage theory and revisit aspects of the constructed scenario to demonstrate how the conceptualisation of a CTO assemblage could be applied to challenge taken for granted aspects of the procedure and reveal where there are opportunities for change, such as in participant roles and the types of knowledge included in existing CTO practices.

2. A Constructed CTO Scenario

Through the hospital entry, passed the reception desk and into the meeting room, strides a suited man who is followed by a woman with an oversized briefcase and a man in a padded vest. The suited man greets the hospital administrator holding the ‘list’ and all four disappear inside the meeting room. Waiting outside the room are mental health practitioners, lawyers, visitors and patients, who can anticipate the start of the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act hearings now the judge has arrived.

The judge takes a seat at the table alongside the court registrar, who pulls out a pile of cardboard folders from her briefcase. Each folder has a label (letters and numbers) and blank forms attached. The court registrar sets up a recording machine on the table. The court security officer sits in a chair between the table and opposite row of empty chairs. The hospital administrator says “When you are you ready sir, I will bring in Mr. Jones. It’s an application for an extension of his community compulsory treatment order.” “Yes, thank you” replies the Judge.

The hospital administrator exits. Seconds later she re-opens the door and directs four people into the room towards the empty chairs. She announces, “Judge Barry, this is Mr. Robert Jones, his lawyer Ms. Wendy Peters, responsible clinician consultant psychiatrist Dr. Raj Singh and second health professional, registered nurse Mr. Bill Hohepa.”

Our drawing in

Figure 1 below shows the participants in our scenario seated and ready for the hearing.

JB: Good morning everyone. Mr. Jones, my name is Judge Barry. I am here today because Dr. Singh has made an application to extend your community compulsory treatment order for a further six months. This means your treating team has asked the Court to continue the current order requiring you to accept mental health treatment in the community.

RJ: Yes Judge I understand that. But I don’t want to keep taking the medication they give me because it makes me too tired to do anything. I’ve already said this to the doctor and to Bill. But the doctor doesn’t listen to me. Bill says I have to take it if I want to keep well and stay out of hospital.

JB: Have you talked about your concerns with your lawyer Ms. Peters?

RJ: Yes Judge, outside we talked about it.

JB: Ms. Peters what are Mr. Jones instructions to you?

WP: Your honour. Mr. Jones instructed me that he opposes the extension of the order. He suffers considerably from fatigue as a side effect of his current medication. For example, he tells me that some days he can’t even get out of bed. On these days, he misses class which puts him at risk of failing his course for certification as a chef. Mr. Jones recognises that he has a mental illness and that he needs to manage it. His refusal to accept the extension of the order is because of the current medication. My client’s advised me that he has raised his concerns and asked to try alternative medication but his clinical team are unwilling to explore other options.

JB: Dr. Singh, I have read your clinical report in support of your application. Having heard from both Mr. Jones and his lawyer, would an extension of the order be necessary if an alternative medication option is available?

RS: Thank you Judge. I have been Mr. Jones psychiatrist for just 3 months. As stated in my report his diagnosis is schizophrenia. He reports symptoms of hearing voices that command violence. These started about 5 years ago and grew more frequent and intense over the last 2 years. Mr. Jones and his parents, who he was living with at the time, became more distressed by these episodes. After one such episode, referred to in my report, the police and the crisis team were called to the house. The outcome was Mr. Jones’ admission as a compulsory inpatient under the Mental Health Act. After 4 weeks, he was discharged on a community order and followed up by our team. Mr. Jones was prescribed an antipsychotic taken by injection every two weeks. He reports the voices have reduced both in their frequency and intensity. I would be very concerned that if Mr. Jones stopped taking his current medication then his symptoms will worsen and he would be at risk of causing harm to himself or others.

JB: Thank you Dr. Singh. Mr. Hohepa—your second health professional report states you’re in agreement to extend the order?

BH: Yes Sir. I have been Robert’s case worker since his discharge from hospital. Robert’s been doing really well. I see him once every two weeks for his injection. I’m aware he struggles with feeling really tired on the meds, so we’ve talked about the things he can do to help himself, like sleep hygiene, daily exercise, good diet and reducing his alcohol intake. I agree with Dr. Singh that if Robert wasn’t on the Order he wouldn’t consent to the injection to manage his symptoms and he could end up back where he was a couple of years ago or even worse.

JB: Thank you Mr. Hohepa. Dr. Singh, Mr. Jones accepts he has a mental illness and the need for treatment. This particular medication appears to have debilitating side effects for him. Are there other options, which could mean a compulsory order is not necessary?

RS: At Mr. Jones’ last assessment he asked me about alternative medications. I explained that his antipsychotic medication is known to cause fatigue. The degree varies across patients. We discussed lifestyle changes to reduce the effects. Unfortunately, there isn’t an alternative medication currently available that is proven to have the same success in reducing the symptoms associated with this diagnosis.

JB: Ms. Peters do you have any questions for either Dr. Singh or Mr. Hohepa?

WP: No Sir.

JB: Thank you, I will now record my decision for the Court.

“This is an application for an extension of a community CTO in respect of Mr. Jones who attended the hearing today with his lawyer, Responsible Clinician and second health professional. The court has had the benefit of clinical reports from Dr. Singh and Mr. Hohepa, who acknowledge the progress Mr. Jones has made.

Mr. Jones accepts that he has a mental illness for which he needs treatment. The objection raised by Mr. Jones and his lawyer against the Order is based on the prescribed antipsychotic from which Mr. Jones experiences fatigue that, sometimes, prevents him attending classes for chef training.

However, Dr. Singh advised that the prescribed antipsychotic is the most effective option currently available to treat Mr. Jones’ symptoms. Dr. Singh and Mr. Hohepa informed the court of actions Mr. Jones could take to reduce this side-effect of fatigue. I suggest that Mr. Jones may need further support from his treating team to make these changes in his life.

I am satisfied that Mr. Jones has a mental disorder as defined in the Act and that without treatment his condition would likely deteriorate. I am further satisfied, after hearing evidence provided to the Court, that without the Order Mr. Jones would not freely consent to the prescribed antipsychotic injection. For these reasons, I am going to extend the order for a further 6 months. I wish Mr. Jones success with his studies and in the future.”

3. The (Complex) Framework That Produces CTOs and Examples of Destabilising Influences

As described in the above scenario, CTOs are made under the MHAct

2 through application by “responsible clinicians” like Dr. Singh and decisions by Family or District Court Judges like Judge Barry. The procedural framework is simply illustrated in the Ministry of Health’s Guidelines to the MHAct with its appended flowcharts (

Ministry of Health 2012). The first period of five days and a second period of ten days of compulsory assessment may be initiated and continued by mental health clinicians in regard to any person who meets the legal criteria of “mental disorder.”

3 Mental disorder is an “abnormal state of mind” of such a degree that the person is a “serious danger” to the health or safety of themselves or others.

4 A person who is assessed as mentally disordered can become the subject of a responsible clinician’s application for a CTO for 6 months, which can be extended a further 12 months, as in our scenario with Mr. Jones and then extended indefinitely.

5 On the basis of an application, a Judge satisfied that the criteria for mental disorder are met can make an order requiring treatment in either a community or an inpatient setting, in the situation where the person cannot be adequately treated in the community.

6 In our scenario, Judge Barry expressly states that he is satisfied Mr. Jones has a mental disorder as defined in the MHAct, based on information in the clinical reports and hearing evidence from Dr. Singh, Mr. Hohepa and Mr. Jones.

There are in-built monitoring mechanisms to protect human rights while under CTOs. Under a part of the MHAct headed “rights of patients,” patients/mental health service-users have a right to information about their legal status, to request a second opinion from an approved psychiatrist and to obtain legal advice.

7 Mr. Jones has access to free services of legal aid lawyer Ms. Peters to represent him in the hearing, although we do not know whether he has exercised his right to request a second psychiatric opinion prior to the hearing and it is not something Ms. Peters raises as an option with Judge Barry.

During the period of a CTO there is a procedural requirement for clinical reviews of the patient/mental health service-user by the responsible clinician. The patient/mental health service-user has access to independently appointed lawyers, called District Inspectors, who monitor patients’ rights (and responsible clinician’s obligations) under the MHAct.

8 A Judge reviews all responsible clinician CTO applications and extensions of CTOs.

9 Once subject to a CTO, patients have a right to appeal their compulsory status through the Mental Health Review Tribunal.

10The effect of a CTO in the community requires a mental health service-user to accept treatment as directed by the clinical team, such as psychotropic medications and attend at a specified community mental health clinic.

11 It is the proposed requirement to continue on a particular prescribed medication as opposed to another with reduced side effects, or no medication at all, that Mr. Jones objects to in our scenario. Under a CTO, compulsory treatment such as assessments and administration of medications occur in a service-user’s home or their supported accommodation or in a community-based clinic as opposed to a hospital or inpatient residence. Furthermore, if the responsible clinician considers that the mental health service-user “cannot continue to be treated adequately as an outpatient” in the community, then the responsible clinician can direct the patient return to hospital for a period of inpatient treatment.

12 Readmission appears to be what Dr. Singh and Mr. Hohepa are seeking to avoid by application to continue the antipsychotic injection on a compulsory basis in the community. The alternative appears to invite too much uncertainty and risk for all involved. Without the CTO, Mr. Jones can refuse medication and without this treatment his nurse, Mr. Hohepa, states “

he could end up back where he was a couple of years ago or even worse.”

The existing MHAct framework is embedded in the wider institutional structure and organisation of national mental health services across New Zealand. In each of the twenty health administration areas a Director of Area Mental Health Services designates responsible clinicians to lead treatment of every person subject to the MHAct.

13 At the national level, the Director of Mental Health, under direction of the Minister of Health, is responsible for the general administration of the MHAct and provides guidance to area mental health services, supporting strategic policy direction and a recovery-based approach to mental health (

Ministry of Health 2017, p. 6).

The main social policy objective that provided justification for the introduction in 1992 of CTOs in New Zealand’s MHAct was the process of deinstitutionalisation of mental health (that is, the closure of large inpatient residential hospitals) and international civil and political human rights.

14 This context is acknowledged in the Ministry of Health’s latest annual report, which states that over the last 50 years, compulsory inpatient treatment has largely given way to voluntary engagement with services in community settings and mental health services have moved from an institutional model of care to a recovery model of care (

Ministry of Health 2017, p. 2). Where engagement with mental health services in community settings is

not voluntary, the MHAct “

defines the circumstances in which people may be subject to compulsory mental health assessment and treatment. It provides a framework for balancing personal rights and the public interest when a person poses a serious danger to themselves or others due to mental illness” (

Ministry of Health 2017, p. 5).

The problem under the existing framework is that New Zealand’s rates of civil commitment are noted to be high by international standards (

O’Brien 2014a). There is a trend of an increasing total number of people on CTOs in New Zealand despite policy endorsement of the ‘recovery model’ and obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities against the use of compulsion. Based on annual reports of the Office of the Director of Mental Health,

Gordon and O’Brien (

2014) state the average number of CTOs on a given day, per 100,000 population, has risen from 60 in 2005 to 86 in 2015 (compared to the average number of inpatient orders from 17 in 2005 to 14 in 2015). At the level of District Court, just over six percent of patients are released from compulsory status and just under six percent of service-users on CTOs are released on appeal to the Mental Health Review Tribunal—figures that

Gordon (

2013) argues represent a low level of disagreement with clinical teams (p. 278).

15 Further to this, statistical analysis of use of CTOs across New Zealand’s twenty health administration areas links variation in rate and use to socio-economic deprivation (

O’Brien 2013). New Zealand’s indigenous population (Māori) are much more likely to live in economically deprived areas. For indigenous psychiatrists

Elder and Tapsell (

2013), the importance of an indigenous-specific focus cannot be over-emphasised. They argue that deprivation alone does not explain the over-representation of indigenous New Zealanders in groups with mental illness (p. 251).

Most research literature on the problems associated with use of CTOs does not focus on the question of how the processes and practices of CTOs are maintained. In part, this is due to the private nature of mental health law (

Winders 2013). In the early 2000s a major research project was carried out to understand patient/mental health service-user, family carers and clinician experiences of CTOs with the aim of enhancing New Zealand’s legal framework (Otago Community Treatment Order Study 1999–2008). Decisions on CTOs were found to be associated with seeing them as necessary and of benefit.

16 A subsequent study by Newton-Howes and Banks in 2014 looked at the experience of assessed patient/mental health service-users’ regarding CTOs. There was a split between those who found CTOs beneficial and those who found them detrimental to their lives (

Newton-Howes and Banks 2014).

17 The recent Ministry of Health review of the 1992 MHAct and human rights acknowledged some mental health service-users and their family report positive benefits from CTOs. However, the majority of mental health service-users and their family report negative effects including enhanced stigma and discrimination (

Ministry of Health 2017).

Overall, research has suggested CTOs are an unjustified interference with people’s human rights because there appears to be no clear evidence of mental health benefits in terms of both clinical and social outcomes.

18 New Zealand research into CTO experience with patients/service-users, their families and their clinicians highlight a range of both positive and negative impacts. Variation, population disparity and increasing use of CTOs across health administration areas is negative from the perspectives of clinical effectiveness and justified limitations on human rights. New Zealand proponents of reform of the existing legislation and its implementation emphasise the need to address variation in rates, the clinical and social outcomes and alternatives to committal. All of this raises questions about the effectiveness of a compulsory community treatment regime that cannot be addressed by a medical and legal procedure alone (

O’Brien 2014b).

Recently, the Chief Science Advisor to the Government declared that the structure in New Zealand for treating mental disorder and supporting mental health is neither optimal nor working well. He argued “[w]

e need a new paradigm for mental disorder and mental health in New Zealand” that considers the complex net of influences of good and poor mental health. These diverse influences include family, employment, rapid social changes such as digitisation and urbanisation, the economy, genetics, education, poverty, alcohol, drug use and physical activity (

Gluckman and FRS 2017, p. 3). This was followed by the Prime Minister’s announcement on 23 January 2018 of a Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addictions to build public consensus on the specific changes in mental health needed to address inequalities, prevention of suicide and enable improved outcomes (

Ardern 2018). The complex issues and dilemmas associated with compulsory mental health treatment in community settings is likely to be part of the Inquiry and may lead to recommendations for a review of the MHAct.

New Zealand researchers and practitioners have reviewed the MHAct over the past 20 years (

Dawson and Gledhill 2013) and argued that there remain unanswered questions. What are the causes of this increase in community CTOs? Is the rate really rising or a result of the ways numbers have been collected over time? What factors are driving up rates? What could be done to reduce them? Are only changes in policy and practice necessary or in legislation too? (

Dawson and Gledhill 2013, p. 23). We argue these questions reveal signs of stress and pressure on the existing MHAct framework.

Addressing the problems of high, increasing and disproportionate rates of CTOs is complex due to the evolution of CTOs in New Zealand and beyond.

19 A number of interacting influences explain why CTOs have become part of mental health regimes in these countries. These influences include the process of deinstitutionalisation, the increased focus on risk and community safety in mental health services and the dominant neurobiological discourses that emphasise the use of drug treatment as a ‘solution’ to mental disorder. Alternative discourses of rights and recovery have also been influential ‘policy drivers’ (

Hardy and Jobling 2015, pp. 533–34).

In conceptualising debate around compulsory community treatment in Australia,

Brophy and McDermott (

2003) identify driving forces for use of CTOs that include deinstitutionalisation, shorter inpatient stays, the nature of severe mental illness (slow to regain decision making capacity), the ‘risk society’, accountability (service follow up), clinical wisdom (experience in CTO use) and legislative reform. Against this they identify restraining forces [opposing use of CTOs] such as a lack of evidence regarding effectiveness, ethical concerns, increased stigma and human rights objections. The availability of effective treatment and resources is identified as a restraining force, together with unintended consequences of CTOs (substitute for highly skilled and resource intensive interventions, increased focus of medicalisation/medication). Brophy and McDermott acknowledge that overall

“the use of CTOs is determined, not only by judgements about individual client need but also by wider social and structural factors played out at international, national and state levels … [for example] there is increasing evidence that CTOs and other forms of involuntary care and treatment are disproportionately used with young men and people from ethnic or indigenous backgrounds”.

The observation regarding use of CTOs with young men from indigenous backgrounds is particularly pertinent in the New Zealand context and we refer to the example of research on disparities among Māori and non-Māori in the context of CTOs below.

From our brief survey of the published research, reports and commentary on associated problems with CTO use, we highlight as examples at a national and an international level influences that are destabilising the existing CTO framework. The first is exemplified by a Ministry of Health human rights and MHAct review, second is population disparities in CTOs between indigenous Māori and non-indigenous New Zealanders. Our third example is the international contested evidence of the effectiveness of CTOs. In part 4 of our paper we argue in more detail how these examples can be understood and explained through Deleuze and Guattari’s “assemblage” concept as forces of deterritorialisation in the CTO assemblage and demonstrate with reference to our constructed scenario.

3.1. Human Rights Review

The existing procedure under the MHAct is argued to be out of step with the human rights framework based on the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (

Gordon and O’Brien 2014). The existing MHAct, in which mental illness is a criterion for treatment without consent, is inconsistent with international developments towards social inclusion of people with mental illness. A contemporary human rights approach asserts the capabilities of people with mental illness—adopting the principles of equality, participation and non-discrimination in the Convention (

Weller 2010, p. 71). This new human rights framework challenges the legal legitimacy of the existing medical and legal procedure and poses a threat to New Zealand’s CTO framework.

Challenges have arisen with the form and administration of MHAct and human rights. A challenge unfolding for the sector is on how the MHAct relates to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities. The United Nations report to the New Zealand Government included a recommendation to review the MHAct to remove mental illness (or disability) to ensure it complies with the Convention so that an individual’s capacity is the basis for treatment. In December 2017 the Ministry of Health released its analysis of submissions received in response to its discussion document on the MHAct and Human Rights and the MHAct (

Ministry of Health 2017). A key theme in submissions is inconsistencies between the MHAct and New Zealand’s human rights obligations under the Convention. Submissions also call for increased recognition of the views and preferences of service-users and informed consent as well as greater choice in treatment options—not just medication. In another key theme, lack of access to early intervention services is seen to be contributing to rates of treatment under the MHAct. Submissions report conflict between a ‘recovery model’ of mental health and the current culture of risk avoidance/management. Acknowledged service gaps are summarised in submissions on need to improve family consultation under the MHAct and need to strengthen cultural responsiveness, competency and assessment, including indigenous approaches.

Our scenario of a private CTO hearing illustrates some of the themes summarised in the Ministry of Health review of human rights and the MHAct. For example, there appears to be no accounting for Mr. Jones views and preferences. The role of legal representative Ms. Peters aligns more with substituted decision making versus supported decision making (which would be a contemporary human rights approach under the Convention). There is an attempt by Judge Barry to explore a greater choice in treatment options, other than Mr. Jones current prescribed medication. The responsible clinician Dr. Singh refers to what is proven most ‘clinically effective’ in medication treatment. Both Dr. Singh and second health professional Mr. Hohepa prioritise ‘risk avoidance/management’ over a ‘recovery model’ of mental health. And although Mr. Jones’ parents are mentioned in the context of the CTO hearing, none of Mr. Jones’ family are present and their existing or future involvement in Mr. Jones care is not discussed (

Figure 1 drawing of the scenario shows an empty chair in the hearing room).

3.2. Research on Disparities for Indigenous People

As stated in our introduction, there exists a marked disparity between CTO rates for indigenous Māori and non-indigenous New Zealanders. Since 2013 health administration areas are required to collect and monitor data on the number of Māori subject to CTOs and report progress on actions to reduce the number of Māori placed under CTOs. As documented by New Zealand Human Rights Commission, this data collection and monitoring is seen as “a good first step towards gaining a better understanding and awareness of overrepresentation of Māori on CTOs” to allow areas to look to address the rate where appropriate.

20In 2015 Māori were 3.6 times more likely than non-Māori to be subject to a CTO. The Ministry of Health acknowledge that social demographic data alone does not account for the high rate of Māori with mental illness giving rise to the question are Māori receiving differential treatment in the mental health system (

Ministry of Health 2017, pp. 25–26). Described by the Ministry of Health as a complex issue the “

figures emphasise that we need in-depth, area-specific knowledge to understand the particular disparities around the country and what could be done at a local level to address them” (

Ministry of Health 2017, p. 23). Elder and Tapsell call for urgent research that is led and designed by Māori (

Elder and Tapsell 2013, p. 258). Disparities between Māori and non-Māori exist in rates of serious mental illness, co-existing conditions and complex and late presentation to mental health services. Elder and Tapsell also point out the potential for bias by clinicians assessing Māori and applying the test of “abnormal state of mind” and risk in definition of “mental disorder” (

Elder and Tapsell 2013, p. 255).

We suggest that assemblage theory could be helpful to identifying ways in which “potential for bias” is framed in a systematic way in practices. For example, by highlighting the role of non-human elements in the process of making CTOs, such as the standard forms and the places for hearings. In our constructed scenario, cultural elements might become part of the CTO assemblage if the nature and order of headings on the standard clinical report form were to prioritise a cultural assessment (over a risk assessment) and prioritise family (whānau) involvement. In our scenario, if the patient/service-user Mr. Jones were Māori, the hearing might be conducted at a community meeting place (marae) of cultural and spiritual significance to Māori. The hearing procedure might be conducted in accordance with Māori cultural protocol (tikanga), for example opening with an acknowledgement prayer (karakia) or song (waiata).

21 3.3. Research on Effectiveness and Benefit

More recent studies beyond New Zealand have led academics and practitioners to cite contested evidence on the ‘effectiveness’ of compulsory treatment in mental health (and addictions), which has contributed to the debate on the use of CTOs—shifting concern about their ethical and legal justification to concern about evidence of their clinical effectiveness and social benefit (

Rugkåsa et al. 2014;

Burns et al. 2013).

22 We argue that these challenges from within the territorial knowledge base of psychiatry are having a destabilising effect on the CTO framework.

Recent international research questions the ethical and legal justification and the clinical benefits of CTOs from the perspective of bio-medical evidence-based practice. In 2007 a report on international experiences of using CTOs summarised 72 data-based empirical studies undertaken in six countries. The report found it was not possible to state whether CTOs were beneficial or harmful to patients and noted research in this area was hampered by conceptual, practical and methodological problems and the general quality of the empirical evidence was poor (

Churchill et al. 2007). In 2014, the Oxford Community Treatment Order Evaluation Trial found no evidence of obvious clinical benefit to justify the substantial curtailment of people’s liberty (

Rugkåsa 2016). This finding was based on a lack of evidence about either the positive or negative effects of CTOs on key outcomes, including hospital admission, length of hospital stay, improved medication compliance, or patient’s quality of life.

As mentioned in reference to our scenario, the responsible clinician Dr. Singh refers to what is proven most ‘clinically effective’ in medication treatment for Mr. Jones. However, the studies cited above have opened up potential for a new line of inquiry. For example, the Judge or the lawyer might raise questions about the effectiveness of a CTO on key outcomes described above, in addition to what constitutes effective treatment. Such an approach unpacks the conflation between effective treatment and effective risk management.

Now we propose looking into a theoretical framework ‘assemblage theory’ that offers a way of explaining and understanding the influences driving and restraining the evolution and use of CTOs and the complexity in the practices and processes around CTOs. In the next section, we examine more closely some of the concepts and components of assemblage theory and relate these specifically to our scenario.

4. What Is Assemblage Theory and Why Use It to Understand the Production of CTOs?

To answer the question what is an assemblage, we introduce Gilles Deleuze, a French philosopher (1925–1995) who collaborated with Felix Guattari, a psychoanalyst (1930–1992) to produce their famous critique of psychoanalysis

Capitalism and Schizophrenia volume one

Anti-Oedipus and volume two

A Thousand Plateaus. Together they also wrote

What is Philosophy? Through these works, Deleuze with Guattari invented a new vocabulary of concepts to think about human existence and social phenomena drawing on geology, geography, biology, art, literature and mathematics. For example, the concept of abstract ‘desiring machines’, later referred to as ‘machine assemblages.’ In Deleuze’s translated words:

“Machine, machinism, ‘machinic’: this does not mean either mechanical or organic. Mechanics is a system of closer and closer connections between dependent terms. The machine by contrast is a ‘proximity’ grouping between independent and heterogeneous terms … What defines a machine assemblage is the shift of a centre of gravity along an abstract line …. The machine is a proximity grouping of man-tool-animal-thing. It is primary in relation to them since it is the abstract line which crosses them and makes them work together”.

The above quote goes some way towards a definition of an assemblage. In English assemblage is the joining of or union of two things, a bringing or coming together. However, Deleuze and Guattari use the French concept of

agencement, which is translated into English as assemblage.

Agencement is an arrangement or layout of heterogeneous elements (different things). It also refers to the action of fitting together a set of different things (

agencer) (

DeLanda 2016, p. 1). The French term does not equate, therefore, to the joining or union of things and this has consequences for understanding the philosophical approach of Deleuze and Guattari. The concept

agencement, for example, enables the rejection of unity in favour of multiplicity and the rejection of essence in favour of events (

Nail 2017, p. 22). For Deleuze and Guattari there exists first ‘becomings’ such as actions, perceptions and variations from which we perceive or organise ‘beings’ (

Windsor 2015, p. 157). There is no presumption of what the organised being is, real experience is the biological, material, affective, social, semiotic, political and economic forces that necessarily combine in the articulation of an assemblage (

Duff 2014, p. 4). The focus is on examining processes or production and the effects through questions of ‘how’ a thing is working rather than ‘what’ is the thing. The idea is to unpack the black box, as Latour has said and see how it came into being (

Latour 1987, p. 21).

We propose that research on the making of CTOs, based on assemblage theory has potential to generate an understanding of how the complex and multilayered elements work together in the

process of making CTOs. Once its territory and elements are mapped, a CTO assemblage may reveal ‘lines’ and openings with the potential for it to be shaped otherwise.

“… If we want to know what an assemblage is, we need to know how it works. We have to do an analysis of the assemblage: what is its structure?... what are the processes of change that shape it? Once we understand how the assemblage functions, we will be in a better position to perform a diagnosis: to direct or shape the assemblage toward increasingly revolutionary aims”

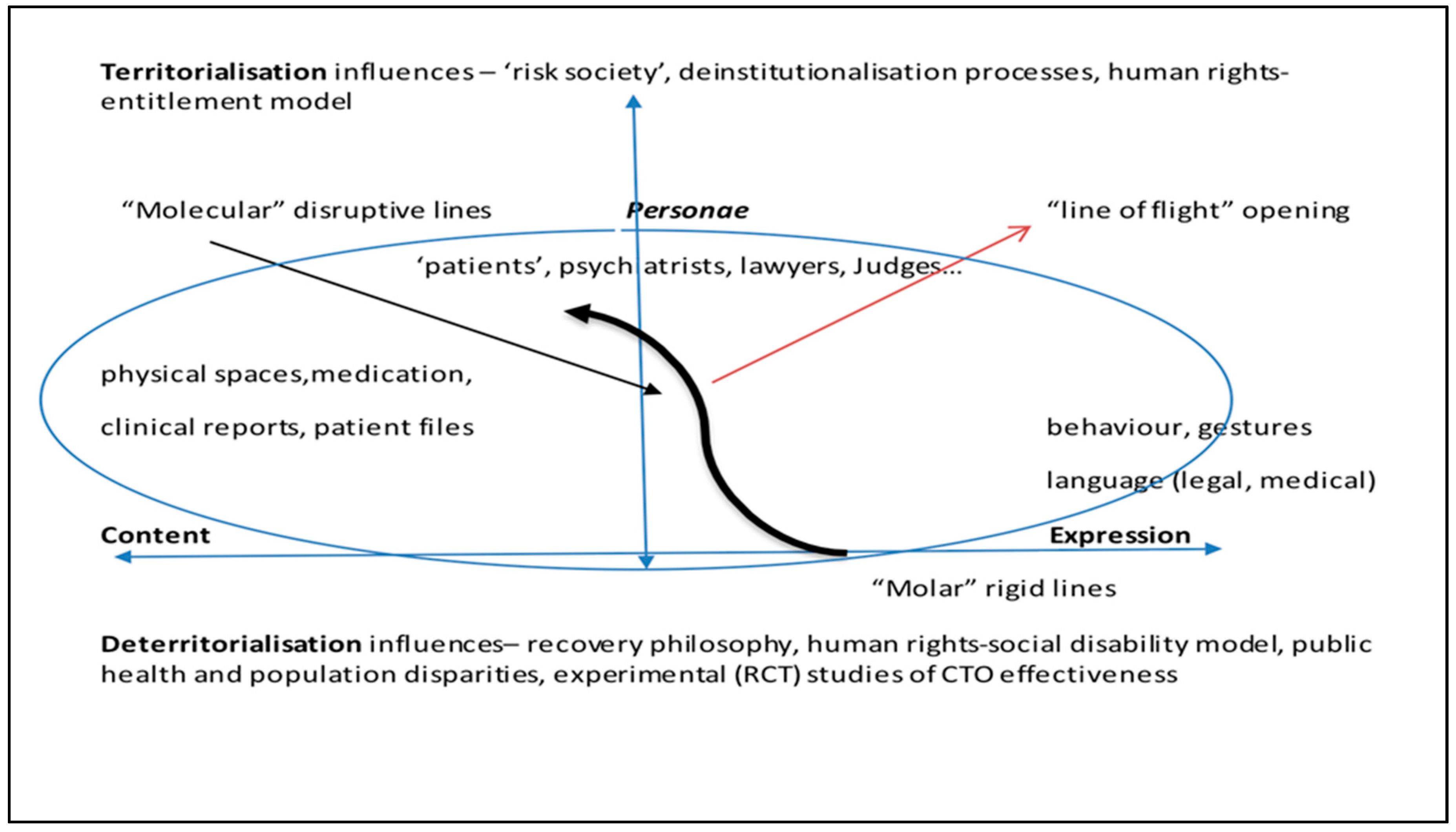

In the remainder of this part we unpack several conceptual devices within the overall concept of an assemblage to explain how it may be formed using the constructed scenario to demonstrate its relevance to MHAct procedures. To aid understandings of how these concepts relate, we bring them together in a diagram (

Figure 2).

Figure 2 shows how the concepts and some of the components of assemblage described below work together and might be mapped as a CTO assemblage. In addition to the material, expressive and personae examples from our scenario, we have identified some stabilising and destabilising influences under territorialisation and deterritorialisation respectively. The first conceptual device is the ‘plane of consistency’ giving rise to the description of Deleuze and Guattari’s philosophy of existence as a flat ontology.

4.1. Concept of a Plane of Consistency

Deleuze and Guattari refer to a plane of consistency that is a pre-subjective, pre-individual field. On a plane of consistency all phenomena or bodies (human, animal, social or chemical) are composed of the same matter and they exist independently and non-hierarchically (

Farrugia 2014). In our CTO scenario for example, there are human bodies and non-human ‘bodies’, such as the table, chairs, the clinical report, the recording machine, the MHAct, patient files. As all these ‘bodies’ enter into connections assemblages are formed (“man-tool-animal-thing”) where for example a service-user, a psychiatrist, a clinical report, a judge, the MHAct are independent elements that combine in an event to potentially make a CTO. Consistency of connections “concretely ties together heterogeneous, disparate elements” that occur in a rhizomatic way, as opposed to a tree-like, arborescent way and have no central source or hierarchy of relations (

Deleuze and Guattari 1988, pp. 589–90). Similar to our constructed scenario, multiple CTO events occur each week across twenty health administration areas, yet each event involves different people in roles as patients/service-users, responsible clinicians, second health professionals, lawyers and judges. The MHAct procedure helps ensure the consistency of connections between the elements in single and multiple events, across institutional areas and nation-state governance levels.

Key to assemblages are these extrinsic relations of composition, mixture and aggregation that are in a continual state of flux. It becomes possible to add, subtract, recombine elements (infinitely) without creating or destroying a unity. The elements of the assemblage are “

not pieces of a jigsaw puzzle” but like a “

dry stone wall and everything holds together only along diverging lines” (

Deleuze and Guattari 1994, p. 23). Each new mixture produces a new kind of assemblage, always free to recombine again and change its nature. Deleuze says “

what counts are not the terms or the elements but what is ‘between’ them, the in-between, a set of relations that are inseparable from each other” (

Deleuze et al. 2002, p. viii). These sets of conditioning relations (abstract machines) are arranged differently in different assemblages, such as in multiple CTO events involving many different people.

In a singular CTO event, such as in our scenario, the relations between the elements might even be re-arranged to imagine other possible outcomes from this particular assemblage. For example, the responsible clinician psychiatrist Dr. Singh could have said ‘yes we can try some other medication or treatment option but it won’t be as effective.’ Would Mr. Jones have objected to being on a CTO if an alternative, less effective treatment option available? How might that evidence have affected the Judge’s decision making, especially regarding risk management? What if the second health professional Mr. Hohepa had disagreed with the responsible clinician and advocated for the longer-term recovery benefits of Mr. Jones completing chef training? What if the lawyer Ms. Peters had challenged the historical assessment of risk and advocated a less conservative approach? If Mr. Jones was Māori, how might the application process and hearing have been conducted differently to reduce the potential for bias? Where were the service-user’s family/parents? Changes in relations between any one or more of these elements may have led the Judge to decide not to make the CTO, or the responsible clinician to decide not to make the application to continue the CTO. These questions reveal potential for things to be otherwise, raising questions about roles different elements play in different arrangements of conditions. This leads into discussion of our next conceptual device.

4.2. Concepts of ‘Content and Expression’

On a plane of consistency, Deleuze and Guattari characterise assemblages along two axes. On the horizontal axis, they distinguish the role which the different components of an assemblage may play and these can be either material content or expressive. In

Figure 2 above this axis is drawn as the horizontal line labelled content at one end and expression at the other. Deleuze and Guattari make an important distinction among expressive components, between those which are directly expressive, such as behaviour and those which rely on a specialised vehicle for expression, such as human language. In our scenario, the material contents include the physical hearing room located in the inpatient unit and the arrangement of tables and chairs. For example, in the drawing (

Figure 1) the position of the security officer’s chair between the row of participants’ chairs and the judge is both a material and an expressive element (symbolic of risk management). The standard forms used in CTO hearings are material documents that contain expressive elements such as psychiatric and legal terminology. These forms can frame CTO hearings and intersect with the participants. In our scenario, the clinical report form is referred to by the Judge and the responsible clinician. The Judge acknowledges he has read Dr. Singh’s report and asks him a question about alternative medication options for Mr. Jones. Dr. Singh does not answer the question (and later the Judge puts it to him again). Dr. Singh replies with a history of Mr. Jones’ episodes, one involving the police “

referred to in my report.” By referring to the patient history part of his clinical report in this way, Dr. Singh emphasises the potential risk that Mr. Jones poses to himself or others.

In addition to these non-human elements, we have human agents in our scenario. Deleuze and Guattari refer to

personae as the mobile agents, positions, roles that connect the concrete material and expressive elements together according to the abstract relations. Personae are not first person, self-knowing subjects and so they are not the origin of the assemblage, they are not above the assemblage, nor do they control it in advance (

Nail 2017, p. 27). In our scenario Mr. Jones, Ms. Peters, Judge Barry, Dr. Singh, Mr. Hohepa, have independent roles that interact with each other and the material and expressive content of the clinical report document. They also have roles in the MHAct procedure as patient, legal representative, judge, responsible clinician and second health professional that define their interaction. In

Figure 2 above, the dynamic connections between these abstract relations is depicted in the elliptical circle around personae, content and expression. In our scenario, the MH Act’s defined roles in the procedure are components in a process that stabilise the identity of the CTO assemblage. These roles can be embodied by different individuals, in multiple events and in this way, can sustain the ongoing use of CTOs. Next, we examine the conceptual device to explain the forces that stabilise and destabilise assemblages.

4.3. Concepts of ‘Territorialisation and Deterritorialisation’

On the vertical axis, Deleuze and Guattari distinguish processes which stabilise the identity of the assemblage (by sharpening its borders, for example, or homogenising its composition) from those which tend to destabilise this identity and open the assemblage to change. These are processes of territorialisation and deterritorialisation, respectively (

DeLanda 2006, p. 266; see

Deleuze and Guattari 1988, pp. 586–87). In

Figure 2 above, the vertical line with directional arrows shows territorialisation pointing upwards and deterritorialisation pointing downwards. In the context of CTO use, these processes might be the “driving forces” and “restraining forces” identified by Australian researchers

Brophy and McDermott (

2003) and referred to earlier in this paper.

In New Zealand, the territorial borders of a CTO assemblage are defined at nation state and institutional levels by the introduction of CTOs into the MHAct. Law (legislation) defines territory in terms of jurisdiction and its ongoing interpretative application in case-law decisions made by the courts and Tribunal. The MHAct (like other legislation) also functions to support governments’ implementation of social policy objectives, such as processes of deinstitutionalisation and human rights.

In the CTO event in our scenario, territory is defined by the physical location and space in which the event takes place. There are also territorial limits on the roles of CTO event participants (who is permitted and qualified to attend a hearing), the speaking order of participants and the subject matter (what is relevant documented and oral evidence). All these elements are defined by law and the procedure in the MHAct itself. Drawing on DeLanda’s philosophical interpretation of assemblage theory, we can use the example of sociologist Erving Goffman’s emphasis on external signs exchanged during conversations (

DeLanda 2006, p. 254). The most obvious expressive component of this assemblage is the flow of words itself. Every participant in a conversation, is also expressing his or her public identity through every facial gesture, dress, choice of subject matter, the use of (or failure to use) tact and so on.

DeLanda (

2006) argues that processes of territorialisation give a conversation well-defined borders in space and in time and are exemplified by behaviours guided by conventions. Similar to conversations, CTO hearing events have a well-defined temporal order, initiating and terminating the hearing and turns speaking during the hearing may all be legally enforced by the judge, in addition to being normatively enforced by the participants. The spatial boundaries of CTO hearing events, like conversational encounters, are also clearly defined because of the physical requirements of co-presence but also because the participants themselves ratify each other as legitimate interactors (

DeLanda 2006, p. 255). Our drawing of the scenario in

Figure 1 shows the close proximity of participants seated in an arc in the hearing room and the quasi-informal nature of the hearing means observations of participants expressing their “public identity” are more open to view.

Within this territory, some issues and dilemmas surface in the expressive content of the CTO assemblage. The existing medical and legal procedure has dual and sometimes conflicting purposes of protecting human rights/promoting individual recovery and social inclusion on one hand and maintaining public safety/social control on the other hand. The definition of “mental disorder” reflects a model of rights-based legalism described by

Weller (

2010) as “

a pendulum swinging between two fixed poles of patient rights and medical welfare paternalism”(p. 71). This tension is visible in discussions that frame the issue of balancing or weighing up compulsion (loss of individual autonomy) against risk in making decisions (

Gledhill 2013, p. 62). Assessment of risk (to the person or others) is central to the use of compulsion under the MHAct. The definition of “mental disorder” includes the words serious danger, from which the assessment of risk is inferred. In our scenario, the pendulum swings in favour of Dr. Singh’s opinion about the risk to Mr. Jones if the CTO is not made.

According to Deleuze and Guattari, assemblages are continually changing through the forces of deterritorialisation that establish, or undermine, or create new assemblages (

Nail 2017). We discussed in part 3 above examples of emerging forces that appear to be destabilising the identity of the existing the CTO assemblage in New Zealand. To describe how and where forces of deterritorialisation are occurring and demonstrate these in relation to our scenario, it is necessary to explain Deleuze and Guattari’s conceptual device of “abstract lines” that cross the elements in the assemblage and make them work together; these are molar lines, molecular lines and lines of flight.

Windsor (

2015) observes that Deleuze and Guattari speak of lines, rather than points or positions. Lines draw a boundary, or chart vectors, across a broader (social) field but also imply relation and connection, with no beginning and no end. While lines are creative in this way, Windsor describes how they can also “

become a slavish tracing, capitulating to established forms and structures” (

Windsor 2015, p. 157). In this image, molar lines are rigid (for example the bold line in

Figure 2 above pointing in the direction towards territorialisation). The term ‘molar’ is drawn from physics where mass is consolidated, concentrated in an integrated whole. Examples include binary categories ‘abnormal/normal’ or hierarchical categories such as gender and social class. The MHAct’s definition of “mental disorder” is an example of a molar line across the CTO assemblage. In molecular lines, the term ‘molecular’ gives us a contrasting image of an infinite number of particles in relations of motions and rest—kinetic and dynamic.

When the loosening of molar segmented lines takes place by molecular elements, new openings in the assemblage become possible in what Deleuze and Guattari refer to as ‘lines of flight.’ In

Figure 2 above, the molecular line is pointing in the direction of deterritorialisation and appears to bend (or even break through) the molar line. While these new openings can result in more freedom (and may even be emancipatory), they can also result in more rigid enclosures (

Windsor 2015). For Deleuze and Guattari, changes in assemblages always have positive and negative effects that cannot be foreseen. The point is that effects of changes in the assemblage cannot be predicted or controlled. For example, the historical process of deinstitutionalisation and human rights increased freedom

and increased stigma and discrimination experienced by former mental health patients in their community settings.

Our examples from the literature of emerging deterritorialisation forces in the CTO assemblage can be understood as directed toward changing (or perhaps even destroying) the existing medical and legal procedure. Assemblage theory can shed light on each of these examples of challenges to the high, increasing and disproportionate use of CTOs as processes of change that shape existing CTO practices. Recognition of the ‘complex net of influences’ involves increasing the types of knowledge that are engaged and privileging the relevance of certain knowledge in existing CTO decision making with the intended objectives of reducing high and disproportionate CTO rates. Examining relations in the existing CTO procedure can reveal where there is potential to effect different outcomes, as demonstrated by references to participants’ interaction in our constructed scenario.

Thinking about the production of CTOs in this way also challenges taken for granted limitations. For example, there are existing opportunities for increased types of participant roles and knowledge to be included? Reconnecting to our constructed scenario, perhaps a new participant could occupy that vacant chair in

Figure 1. In addition to, or in the absence of, a family member to support the service-user/patient a peer support person could advance the perspective of what successful recovery means for Mr. Jones. If Mr. Jones were Māori, the knowledge of a participant Māori cultural advisor might extend or challenge the perspective of “abnormal state of mind” that poses a “serious danger” in the context of Mr. Jones’ observed and clinically assessed behaviours. From a new or an amended CTO medical and legal procedure may emerge conditions for practice of a new ‘compliance assemblage’ that would generate positive effects for participants’ relations, risk and recovery-oriented practices and perhaps even variation and disparity in mental population outcomes.

However, there is also potential for unintended negative effects. An

increase in use of CTOs may result from a public health perspective that social reasons for invoking legislation are relevant to clinical decision-making if the influence of social factors on individual mental health is considered (

O’Brien 2013, p. 311). An example may be the social need for adequate housing or a suitable accommodation placement on the basis that it helps ensure the service-user/patient is protected from exploitation by, or isolation from, others in their community and facilitates access, monitoring and oversight by the clinical team. Similarly, a broader more flexible role has been advocated to engage clinical and social factors in addition to legal ones, for example in regard to Australian Mental Health Tribunals (

Carney et al. 2011).

23Further, a new or amended legal procedure for CTOs (or even the complete absence of one) provides no guarantee of reduced negative impacts of compliance for patients/service-users. In a real-world example of an ‘assemblage of compliance,’

Brodwin (

2010) ethnographic study follows a community mental health assertive treatment team in a United States mid-west town over a two-year period.

Brodwin (

2010) draws on the concept of an ‘assemblage of compliance’ in psychiatric case management to explain the role of community case managers for people with severe and persistent mental illness. He uses the theoretical notion of assemblage with its human and non-human elements (medications, biopsychiatry knowledge, division of professional labour and mundane tools) to highlight dilemmas based on his observations of case manager day-to-day practice. This theory allows

Brodwin (

2010) to examine the role of the medication cassette in shaping and directing relations of compliance between case managers and service-users.

Brodwin (

2010) highlights that compliance can be effected without the need for discussion and persuasion in face to face encounters.

The destabilising influences we identified in part 3 that are examples of ‘deterritorialisation’ in the context of Deleuze and Guattari’s assemblage theory become relevant if we view the law, medicine and public health as knowledge bases that have come to dominate the ways in which our understanding of ourselves is formed. Each uphold the logic, also characteristic of western philosophical thought, of the mind-body split and separation of self from other (

Malins 2004). By presupposing our individual body, knowledge bases of law, medicine and public health can distinguish ‘mental health problems’ as separate from particular social, economic, legal or cultural factors or determinants.

Duff (

2014) argues that a problem with “social and structural determinants of health” in public health research has been the challenge of documenting clear causal links between specific social or structural processes and the generation of inequalities in particular groups or places. The issue is how to identify the specific mechanisms or processes to intervene in structural factors that may be shown to improve health outcomes in particular areas, among particular groups, at particular times (

Duff 2014, p. 3).

We acknowledge it is a challenging to think about the use of compulsory mental health treatment from a philosophical approach that seems to assume an absence of hierarchy and individual agency in relations between elements and roles, as described in the concept of a ‘plane of consistency’ in part 4 above. This can result in a lack of priority being given to the examination of power and its effects. To safeguard against this, a general critical discursive analysis approach would be a useful and compatible strategy to problematize CTO use in the way it analyses multiple texts for ‘discourses’, articulates how they are historically formed and used within the context of a jurisdiction’s specific legal and medical procedure.

24 As in our scenario, a focus on the event of a CTO hearing can provide the place to observe where multiple practices, human and non-human elements, interplay. A CTO hearing potentially involves intersecting discourses and perspectives drawn from a range of knowledge bases, such as psychiatry, nursing, recovery, indigenous and human rights law. Analysis of blank template documents (texts) such as the clinical report form, referred to in our constructed scenario, can also draw on critical discursive analysis techniques. Observations of practices in CTO hearings can draw on ethnographic approaches.

25A second limitation of this paper is that it is not based on primary research. The paper draws on published research and documents together with a constructed scenario, with the aim of conceptualising a CTO assemblage. We suggest research to define and examine CTO assemblages could properly interrogate the usefulness in practice of the application and interpretation of assemblage in a real-world situation to generate novel insights.