Abstract

In the past few years, Latin American countries have started to enact changes in their legal capacity regulations regarding persons with disabilities. However, even when these changes started over eight years ago, there were few to no analyses on the matter. In addition, there is no encompassing theory or typology on how these reforms happen and on their effects. In the present paper, we propose two axes of analysis for the reforms: enforceability and compliance with Article 12 of the CRPD. This matrix allows for four kinds of reforms: incipient, formal, conciliatory and radical. Using this matrix, we examined the legislative changes in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Mexico, Nicaragua and Peru. Incipient reforms (Mexico) are not that effective but can lead to serious later change. Formal reforms (the Dominican Republic, El Salvador and Nicaragua) have few to no effects. Conciliatory reforms (Argentina, Brazil and Costa Rica) are a legislative compromise that allows for progressive change. Finally, radical reforms create encompassing change that is good but might create problems in the implementation.

1. Introduction

Since the adoption of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in 2006, several countries, mostly in Latin America, have radically changed their approach to defining the legal capacity of persons with disabilities (Bezerra de Menezes et al. 2021b). These countries have started enacting changes in their legislation that recognize (different levels of) legal capacity, provide supports and establish safeguards. However, they have achieved this in different ways, or at different speeds.

Their reforms, nevertheless, have not generated a lot of attention from academia, and papers on the matter continue to be scarce (Martinez-Pujalte 2019; Constantino Caycho 2020; Marshall et al. 2023). This may have different causes. Legal knowledge follows the rules of the politics of knowledge (Quijano 2007). This means that the law—and the academia around it—created in “production sites” (López Medina 2004), usually placed in the metropolis (Bonilla Maldonado 2015), are seen as superior and universal. In contrast, the law created in “reception sites” (López Medina 2004) from the colonial space (Bonilla Maldonado 2015) are seen as inferior and merely local. Regarding the implementation of Article 12, this has had the effect that most of the literature about its implementation comes from the Global North countries (Dhanda 2017), especially, from countries of the Anglosphere.

When Latin American countries started the reforms pursuant to Article 12, most of the literature about it was from those places. However, such literature was of little use for Latin American countries for two reasons. The first reason has to do with legal systems. In Latin America, civil systems are the rule, while in the Anglosphere most of the systems are of common law. Civil law and common law systems are quite different, and lawyers in each system have divergent views regarding issues such as legislation or the roles of a judge. Basically, in the civil law jurisdictions, the main source of the law are codes, comprehensives bodies of norms with abstract answers for general situations (David 1985). On the contrary, in the common law systems, judges’ decisions for specific disputes are sources of law. Therefore, the literature of those countries did not have in mind problems that the civil law systems needed to anticipate for a reform. For example, the civil law systems needed to determine how to understand vices of will (a general abstract concept) without relating it to disability (Constantino Caycho 2020). This is not a problem in the common law systems, since they can solve those problems in a case-by-case basis.

Even though most of the Continental Europe’s countries have civil law systems, they were of little help in the Article 12 reforms in Latin America. Continental Europe legal concepts related to persons with disabilities (such as amministrazione di sostegno or Betreuung) were adopted prior to the CRPD and are not compliant with Article 12. One exception is Spain, a country that has recently enacted a reform to protect legal capacity of persons with disabilities. The Spanish reform is out of the scope of this paper. However, we argue that it brings some advancements such as the provision of support, safeguards against undue influence and an ad litem defender for cases in which it would be necessary (such as a conflict of interest).1 Then, it certainly has been an improvement from the previous situation and could be useful for other reforms both regionally and globally. Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that this reform does keep guardianship for some cases related to disability.

In conclusion, common law north-centric institutions did not resolve issues of Latin American civil law systems, and civil law north-centric institutions were not Article 12 compliant. Thus, when Latin American countries began to adapt their legislation to CRPD standards, there were no guidelines on how to adapt the different rules about capacity or juridical acts for the mandates of Article 12 of the CRPD. Nevertheless, these countries have managed to generate laws to expand the rights and liberties of persons with disabilities. Paraphrasing Mariátegui, our reforms have not been an imitation or copy, but a “heroic creation” (Mariátegui 1928). In this paper, we propose a four-speed typology of these reforms in Latin American countries to understand their scope and the possibilities for changing private law.

For our analysis, we will start by defining legal capacity reforms. We understand this concept as an encompassing change of the rules regarding legal capacity2 from a general scope. This means that, either in intent or effect, the new rules need to be widely applicable, at least to the entire private law (contracts, torts, family law and juridical acts, among others). Therefore, certain specific changes would not comply with our definition of legal capacity reform. For example, the recent mental health law in Chile (Law 21331 on the Recognition and Protection of the Rights of Persons in Healthcare of 11 May 2021) does not comply with the definition. Even when it recognizes the right to receive support for decision-making, it is not a general change, but a very specific one. Therefore, we will consider reforms in the following cases: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Mexico, Nicaragua and Peru.

2. Legal Capacity of Persons with Disabilities in International Human Rights Law

Approaches to the legal capacity of persons with disabilities have recently changed due to the adoption of the CRPD. The core of this revolutionary change is proposed in Article 12 of the CRPD, which establishes equal recognition before the law. This article consists of five items. The first of them refers to equal legal personality, that is to say, equal capacity to act and equal recognition of the person as a person. This right has been widely recognized in the world’s legal systems3. The second item recognizes the equal legal capacity of people with disabilities4. This is the radical change. Persons with disabilities, as per the CRPD, enjoy the ability to exercise their legal capacity in equal conditions as the rest of people. Therefore, concepts such as guardianship, which rescinds legal capacity and takes away the will of people with disabilities in a perpetual and complete manner, are prohibited, according to the interpretation of the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2014, p. 7). Items three and four plan the need for support and safeguards, and item five reiterates the obligation to recognize the legal capacity of people with disabilities and not exclude them from the possibility of being proprietors, inheriting and contracting.

We can summarize the basic obligations of Article 12 of the CRPD as follows: (i) recognizing legal capacity, (ii) abolishing guardianship, (iii) providing voluntary supports and (iv) guaranteeing safeguards. We will argue that we can evaluate the level of compliance of Latin American countries by judging the extent to which these countries have achieved these four obligations and the enforceability of their laws. It is important to mention two things. The first one refers to the margin of appreciation the States have regarding to legal capacity. While “the relevant rights of the person concerned must be respected”, States enjoy a certain level of discretion to decide the procedural arrangements needed by a person to exercise their legal capacity (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2016, 8.6).

The second one is related to the progressive realization of Article 12. Even though the CRPD Committee has said that progressive realization “does not apply to the provisions of article 12” (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2014, p. 30), it is not clear on what this means. Just after that sentence, the Committee indicated that “States parties must immediately begin taking steps towards the realization of the rights provided for in article 12” and that those steps must include “consultation with and meaningful participation of people with disabilities and their organizations” (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2014, p. 30). Taking into account this kind of measures, it is difficult to imagine an immediate implementation of Article 12. In a more precise way, we argue that some obligations may be immediate, such as eliminating legal capacity restrictions for voting, while others may be progressive, such as creating a system for the recognition of supports. Because of this variety of provisions, there is no one-size-fits-all answer for compliance with Article 12. Besides some guidelines, in this case, States enjoy of a broad margin for compliance in order to implement either immediate of progressive realization measures. With that in mind, our analysis will allow for different answers and the possibility of further change in the future.

2.1. Recognition of Legal Capacity

Recognizing legal capacity for persons with a disability means that the disability cannot be the reason for a restriction of legal capacity. This statement has a complex interpretation due to the breadth of the definition of a disability and the thin line that separates disabilities from associated conditions. The lack of consensus on the meaning of the term was present across the CRPD negotiations and its adoption (Dhanda 2007; McSherry 2008). Years later, the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee), the United Nations body in charge of monitoring the CRPD, sought to clarify its meaning in its General Comment 1. In doing so, they found that there are three possible approximations for the restriction of legal capacity linked to a disability: status or condition, result and functionality.

A restriction by status or condition, on one hand, operates when law restricts the possibility of making decisions for a person due to a diagnosis of a disability (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2014, p. 15). Thus, for example, it would not be possible to prevent a person with schizophrenia from entering into a marriage contract solely because of having such a diagnosis. A restriction by result, on the other hand, is the one that allows the limitation of the exercise capacity based on whether the decision adopted by the person with the disability is considered to be more adequate in certain conditions (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2014, p. 15). For example, if a person with an intellectual disability and an aggressive cancer decides to undergo an operation recommended by the health staff, their legal capacity would not be questioned, but this might happen if the person decided not to undergo the surgery.

Finally, the General Comment refers to a functionality or competence restriction. This concept analyzes whether the person really understands the implications of a particular legal act. This will be determined through functionality assessments that should be limited to a particular juridical act. The draft for the General Comment stated that “functional tests of mental capacity, or outcome-based approaches that lead to denials of legal capacity violate Article 12 if they are either discriminatory or disproportionately affect the right of persons with disabilities to equality before the law” (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2013, p. 12). However, in the Comment’s final version, the Committee decided to ban the functional approach for two reasons: because “it is discriminatorily applied to people with disabilities” (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2014, p. 15) and because “it presumes to be able to accurately assess the inner-workings of the human mind and, when the person does not pass the assessment, it then denies him or her a core human right—the right to equal recognition before the law” (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2014, p. 15). The fact that the draft of the General Comment did not proscribe the restriction of legal capacity by a functional approach seemed to indicate a lack of consensus about the discriminatory effects of functionality.

On this matter, Series and Nilsson have stated that knowing whether the functionality assessments are discriminatory or not is key in the debates on Article 12 of the CRPD (Series and Nilsson 2018, p. 354). This debate is centered around whether a minimum understanding is required for acting in law, or if asking for such an understanding results in discrimination in all cases. Then, the defenders of the functional approach consider that functional assessments are neutral tools that allow the mental capacity of a person to make specific decisions to be properly valued (Series and Nilsson 2018, p. 353). According to Series, if mental capacity assessments can and are used in a discriminatory and disproportionate way, it cannot be said that they are “inevitably discriminatory or disproportionate in all circumstances” (emphasis in the original) (Series 2014). In the same line, Martin and others have argued that functionality tests are compliant with the requirements of the CRPD, even if the CRPD Committee does not agree (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2016). Finally, Dawson has suggested that there are certain figures in law that seem to require a particular functioning of the human mind: malice, intention and informed consent, for example (Dawson 2015, pp. 70–73). Against this position, we can find another one called universalist (Series and Nilsson 2018, p. 365). Its proponents, such as those proposed by Minkowitz (2013) and Devandas (2017), have denied that the functional approach is compatible with the CRPD and argue against placing restrictions on legal capacity that are based on or related to the disability.

In our view, it is clear that the law, in many cases, requires some level of understanding of the implications or effects of juridical acts in order for an expression of will to be considered valid. In that sense, evaluating functionality is not necessarily discriminatory. It may even be necessary for the provision of supports. Additionally, functionality is already evaluated in different situations. For example, certain legal concepts such as “intention, understanding, or foresight” require an assessment of the human mind (Dawson 2015, p. 73). The same happens with regards to informed consent, as a potential patient needs to understand the implications of any given treatment. Therefore, we hold that the functional approach is compliant with Article 12 of the CRPD, since it is applied generally to all persons. Moreover, as we will state in this paper, all the major Latin American reforms have a functional approach.

2.2. Abolition of Guardianship

Compliance with Article 12 implies the abolition of regimes that establish an absolute negation of legal capacity and a substitution of will. In General Comment 1, the CRPD committee established the following criteria for identifying a substituted-decision regime: “(i) legal capacity is removed from a person, even if this is in respect of a single decision; (ii) a substitute decision-maker can be appointed by someone other than the person concerned, and this can be done against his or her will; and (iii) any decision made by a substitute decision-maker is based on what is believed to be in the objective “best interests” of the person concerned, as opposed to being based on the person’s own will and preferences” (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2014, p. 27).

For a situation to be an involuntary substitution of will, the three requirements must be met jointly. In the majority of Latin American countries, interdiction or guardianship meets these criteria. As an example, the Bolivian Civil Code establishes that the interdiction is directed at those adults with a “mental or psychic disability that prevents self-care and the administration of their well-being,” and deprives them of all ability to make decisions5.

2.3. Provision of Voluntary Supports

Article 12.3 states that people with disabilities have a right to “support for the exercise of legal capacity.” These can be understood as mechanisms to facilitate the will of a person at the time of making a decision of legal relevance. In this sense, its functions will help to “(a) obtain and understand information, (b) evaluate the possible alternatives and consequences of a decision, (c) express and communicate a decision, and/or (d) implement a decision” (Devandas 2017, p. 41). These elements reinforce not only the idea that supports do not replace the will of a person, but also that to act in the law, a minimum level of comprehension is needed.

It is also important to highlight that supports should not be confused with accessibility measures. Supports are not interpreters. They should help with decision-making. For Dinerstein, supported decision-making consists of “a series of relationships, practices, arrangements, and agreements, of more or less formality and intensity, designed to assist an individual with a disability to make and communicate to others decisions about the individual’s life” (Dinerstein 2012, p. 10). This system must be available for anyone who requires it, should be based on the will of the person (not the best interest) and must be recognized by the legal system (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2014, p. 29).

2.4. Establishing Safeguards

Regrettably, the CRPD committee did not provide a clear route on how to interpret the content of safeguards in the GC1. As a result, it has mostly been developed through doctrine (Constantino Caycho and Bregaglio Lazarte 2022; Martin et al. 2016; Szmukler 2017). Martin and others identify six distinctive characteristics of safeguards: (i) they are intended to prevent abuse; (ii) they must be used for the shortest time possible; (iii) they should be reviewed periodically; (iv) they should be proportional; (v) they should be effective; (vi) they should be plural (Martin et al. 2016, p. 38).

From these, it is clear that the safeguards are meant to protect the person with a disability from abuses when exercising their legal capacity. However, this protection scope and characteristics are not clearly determined. With regards to the scope, Article 12.4’s text is unclear as to whether safeguards only operate in the context of a support relationship or if they are also binding for third parties. As we have argued before, safeguards could compel certain third parties, especially those that have to verify a will, such as notaries or medical practitioners (Constantino Caycho and Bregaglio Lazarte 2022).

Regarding characteristics, the main question is around the interpretation of respect for “the rights, the will and the preferences of the person” in Article 12.4. Could safeguards be imposed against the will of a person with disabilities and, if so, is this a legal capacity restriction? We hold that for safeguards to be effective, they should be in place even if the person does not anticipate their need or rejects them. This interpretation would also be consistent with the characteristics of “proportionality” provided for in Article 12.4. Proportionality implies planning for interventions that can be carried out, even against the will of the person, to safeguard their rights (Szmukler 2017). Not safeguarding their rights in a precise way could go against some of the principles of the CRPD such as respect for the inherent dignity of the person (Article 3.a) or equality of opportunity (Article 3.e). If a person with a disability is left alone without safeguards, they could also be victims of discrimination and abuse. This means, according to Martin and others, that autonomy could not always be the prevailing principle or right (Martin et al. 2016, p. 39).

3. A Brief Description of Legal Capacity Reforms in Latin American Countries

A general approach centered in a legal source for the Latin American legislation on legal capacity shows four different formulas6. Some countries have reformed their civil codes, while others have adopted a specific law on the matter with a general scope, but without modifying the main regulations of private law. Another group just stated the right to legal capacity in their disability laws, following the spirit of Article 12 of the CRPD. Finally, Mexico comprises the last group, where even though it does not have a legal capacity regulation, its high court has recognized the legal capacity of persons with disabilities in several cases.

3.1. Civil Code Reforms

Argentina was the first country that reformed its Civil Code in 2014, through Law 26.994. This was not a specific reform on legal capacity, but a general revision of the older Civil and Commercial Code. Even though the said norm sought to align with the standards of Article 12 of the CRPD, it did not accomplish the goal of abolishing interdiction as the CRPD committee has stated, and did not provide voluntary supports.

Along this logic, even when Article 22 of the Civil Code states that every person holds legal rights and duties, there is no rule that expressly and specifically recognizes the legal capacity of people with disabilities. In fact, Article 31 points out that the general capacity of the person is presumed, even when they are admitted to a care facility. However, Article 32 allows for an incapacitation process before a judge. In addition, even though Article 31 states that limitations on capacity are exceptional and are always imposed for the benefit of the person, this may lead to full incapacitation or capacity restrictions. The former is a traditional guardianship and occurs when “the person finds themselves absolutely unable to interact with his environment and express their will in any suitable way, medium or format and the support system is ineffective.” On the contrary, capacity restrictions are imposed on certain acts if a person over the age of thirteen “suffers from an addiction or a prolonged permanent mental disorder, of sufficient severity, provided that he deems that the exercise of his full capacity may result in damage to his person or property.” It is only in this scenario where a judge would designate supports7. Then, there is no public policy for the provision of support or the possibility of requesting voluntary support, and there is no regulation of safeguards.

Certainly, the process to restrict the capacity or declare the incapacity of a person has some guarantees established in Article 31: (a) state intervention is always interdisciplinary, both in treatment and in judicial proceedings; (b) the person has the right to receive information by appropriate means and technologies for their understanding; (c) the person has the right to participate in the judicial process with legal assistance, which must be provided free of charge if they lack the means; (d) priority should be given to therapeutic alternatives that are least restrictive of rights and freedoms.

In this sense, although it is not completely aligned with the CRPD model (Kraut and Palacios 2014), the Argentine reform shows a transition from a model of substitution of the will to one of support in decision-making. In this scenario, it is clear that the Argentinian reform embraces a functional model. Not all persons with disabilities should be restricted in their capacity, and not for all acts. The main issue to determine whether or not this kind of measure should be adopted is the possibility of a person to interact with the environment, their comprehension of it, and their ability to communicate a will.

The second country to adopt a Civil Code reform that involved legal capacity was Brazil in 2015. Unlike Argentina, this was not a general reform. Law 13146, known as the Disability Law, modified the Civil Code only in matters of legal capacity. However, the reform seems to be very much comparable to the Argentinian one regarding guardianship. It was not abolished, but reduced. Article 84 of the Disability Law establishes the right to equal recognition before the law. In accordance, the law modified Articles 3 and 4 of the civil code in order to expulse norms referring to the incapacity of persons with disabilities. However, in a clear adoption of the functional restriction model, Article 4.III maintains incapacitation for certain acts of “those who, due to a temporary or permanent cause, cannot express their will.”

Regarding guardianship, Article 85 of the Disability Law reduces the scope of guardianship only to patrimonial acts and torts, and highlights the exceptional nature of guardianship. It also forbids its use for acts related to sexuality and the body, privacy, education, health, marriage, work and voting. Additionally, in line with the functional model, Article 1767.I of the Civil Code establishes that those persons who, for temporary or permanent reasons, cannot express their will are subject to guardianship. Even though we support a functional model, it is important to emphasize that, as the Argentinian reform, guardianship (a substitution of the will regime) remains in force for cases of people who cannot express their will, and it is less clear when it comes to defining what it means to “express will” than the Argentinian reform. In this sense, there is a risk that a medical approach will continue to be applied to the manifestation of will and that it will be concluded that those who have a mental disability, due to the fact of having it, cannot express their will (Bezerra de Menezes et al. 2021a).

The Disability Law also created a support system in Article 1783-A. According to the Brazilian civil code, supported decision-making is a process through which a person with a disability appoints, in a judicial procedure, at least two trusted people to help them make decisions about acts of civil life. These supports must provide the person with the necessary elements and information so that they can exercise their capacity, and Article 1783-A states that support does not replace the will of the person. It is difficult to argue that this regulation satisfies the standard of the CRPD because of the following reasons. First, according to Article 1783-4.5) of the Civil Code, a third party that contracts with a person with support can request the support to sign the contract. Second, in the case of a transaction that can “generate significant risks or prejudices,” Article 1783-A.6) states that, if there is a divergence of opinion between the person with support and one of the supports, the judge will rule after asking for an opinion from the Public Ministry. While this could be a situation where safeguards are necessary, it seems that the will of the person with the disability has no value in this circumstance. Assessing the opinion of the supporter when determining the validity of a decision would be contrary to the model of full legal capacity.

Peru is the third country to implement a Civil Code reform on legal capacity, through Legislative Decree 1384 in 2018. Since this reform, Peru has abolished incapacity and guardianship based on discernment, mental retardation or mental deterioration (Articles 43.2, 43.3 and 44.2 of the Civil Code). Regardless, the institution remains for alcoholism and drug addiction (both of which may be considered disabilities) and other situations such as bad administrators and spendthrifts (which could be manifestations of mental disabilities). Nevertheless, the intent was clear even if the result was not.

In accordance with Article 659 of the civil code, there are two kinds of supports: voluntary and exceptional (mandatory) supports, depending on the capacity to manifest a will. As a general rule, people with disabilities may appoint voluntary supports according to their preferences and will through a judicial or notary procedure8. This includes the possibility to appoint supports in advance9. As an exception, only judges may designate mandatory supports for those people with disabilities who cannot manifest their will10. It is important to point out that, following a functional perspective, the non-manifestation of will is only configured after real, considerable and pertinent efforts have been made to obtain a manifestation of the will of the person, after having provided the accessibility measures and reasonable accommodations, and only when the designation of support is necessary for the exercise and protection of their rights. That is to say, the measure must be ultima ratio and cannot be as used as a mechanism of deprivation of capacity.

In relation to safeguards, Article 659-G of the civil code establishes that they can only be appointed by the person with the disability in the voluntary support designation process. In our view, this regulation satisfies the unclear standard of Article 12.4 of the CRPD, even though we maintain that mandatory safeguards are not contrary to the CRPD, but needed in order to protect “the rights, the will and the preferences of the person” (Constantino Caycho and Bregaglio Lazarte 2022). On the contrary, in the exceptional (mandatory) support designation process, judges may decide on different safeguard measures, where the only mandatory one is a periodical review of the support performance.

Finally, Colombia reformed its Civil Code in 2019, through Law 1996. This law, as the Peruvian reform, eliminated incapacity- and disability-based guardianship. It also established a system of supports and safeguards. The law has a “scaled development” (Isaza Piedrahita 2021, p. 302): not all its provisions entered into force immediately. The ones related to the judiciary were delayed, allowing for the courts to adapt to the new regulations.

Similar to the Peruvian reform, Articles 16, 17 and 32 establish voluntary and mandatory supports. The first can be designated voluntarily through a notarial agreement, through an out-of-court conciliation or in a judicial process. They can also be established through advanced directives11. Following a functional perspective, the second can be appointed compulsorily by a judge when the person with disabilities cannot express their will and preferences, and there is a risk of violation of their rights12. In addition, the norm establishes in its Articles 5 and 37 the possibility of adopting safeguard measures.

Reforming civil codes is a complex issue. It takes time and demands a high level of amendments and articulation with other normative bodies. However, it is important to recall that civil codes are texts that aspire towards permanence. On the matter, Fletcher has said (with reference to a continental European context, but applicable to Latin American cases) that a civil code “provides the thread that runs through history and ties the country together through diverse political regimes” (Fletcher 2001, p. 14). In many of the cases presented, civil codes have survived even to constitutional changes. Because of that, and besides the costs, by changing the civil code, the reforms aspire to be stable.

3.2. Specific Reforms with General Scope

Costa Rica implemented a very unique reform. In 2016, they issued Law 9379, or the Law for the Promotion of the Autonomy of Persons with Disabilities. This law aims to promote and ensure, for people with disabilities, the full exercise of their right to their personal autonomy on an equal basis with others. It abolished guardianship—regulated in the family code—and established the figure of the guarantor for the legal equality of people with disabilities. For that, the law also modified the civil procedure code.

However, since Costa Rica has a Civil Code that is separate from its family code, the law did not modify the former. This led to the coexistence of opposing norms. As a matter of fact, Article 36 of the Civil Code states that, in the case of natural persons, legal capacity may be modified or limited (amongst others) by the person’s volitional or cognitive capacity. In addition, according to Article 591, those who do not have “perfect judgment” cannot make a testament. More importantly, according to Article 41, legal acts or contracts made without “determined and cognoscitive capacity” are voidable. As such, regardless of the law’s intended purpose, Costa Rica now has a contradictory legal capacity system. Because of this, numerous legal operators have refused to apply the law (Vásquez et al. 2022, p. 196).

Aside from the contradictions between legal bodies, Costa Rican law presents other issues that stem from a confusion between the guarantor and safeguards. Article 3 of Law 9379 defines a guarantor as “a person over eighteen years of age who, to ensure the full enjoyment of the right to legal equality of people with intellectual, mental and psychosocial disabilities, guarantees their legal standing and legal exercise of their rights and obligations. For the cases of persons with disabilities who are institutionalized in State entities, the guarantor may be a legal person.” On the other hand, the same article defines safeguards as “adequate and effective mechanisms or guarantees established by the Costa Rican State, in the legal system, for the full recognition of legal equality and the right to citizenship of all persons with disabilities (…) The design and implementation of the safeguards must be based on respect for the rights, will, preferences and interests of the person with disabilities, in addition to being proportional and adapted to the circumstances of each person, applied in the shortest possible time and subject to periodic examinations by a competent, independent, objective and impartial authority.” In addition, the norm indicates, in Article 6, that safeguards must be processed through the courts, and Article 5 indicates that the guarantor is the person designated as the safeguard.

From reading, it is clear that the guarantor would be a kind of support. This is consistent with Article 11, which states that the guarantor should “not act, without considering the rights, will and abilities of the person with disabilities.” However, it seems that the guarantor would be equivalent to the safeguard. Here lies the first problem, because according to Article 12.4 of the CRPD, the safeguard is a measure to prevent (among other things) abuses appearing in the relationship between the support and the person with a disability. In this sense, equating the support with the safeguard generates a lack of protection, since safeguards themselves would not be designated. That said, the only real safeguard measure identified in the law is a review of the designation ex officio by the judge every 5 years, which, in our view, is insufficient not only because of the long term, but also because the judge should be able to order complementary safeguards adapted to the circumstances of the person.

A second issue is that, at least in certain cases, it will be the guarantor/safeguard who expresses the will, and not the person with a disability. This emerges from the text of Article 11, which states that the guarantor should “not act” without considering the rights, will and abilities of the person with the disabilities. This regulation is not, per se, contrary to Article 12 of the CRPD. As has been seen in Peru and Colombia, exceptional supports should act in the name of the person with the disabilities. However, the problem with the Costa Rican law is the lack of clear provisions that state when the guarantor should have these attributions, or the exceptionality of that situation.

In addition, the regulation of the law, promulgated by Executive Decree 41087, refers not only to safeguards and guarantors, but also to support for legal capacity. It is particularly important to mention Article 8, where the “intensity levels of support” are regulated. This article also mandates that judges shall determine the level of intensity of support (mild, moderate or intense) depending on the level of consciousness of the person with the disabilities. However, no clear guidelines are established to designate each of these supports, not are the functions of intense support indicated. The law only provides that light support will guide and that moderate support, for example, would imply the joint signing of documents before a notary.

Although the Peruvian and Colombian models also contemplate the possibility that, in exceptional cases, the support assumes legal representation, the regulations are more careful when establishing the assumptions to apply this type of support, so that it does not remain as an indeterminate assumption. In addition, given that intense support is a substitution of the will, it would have been desirable that its regulation be given by a legal and non-regulatory instrument. On the other hand, in the definition of a guarantor in Article 3, the possibility is raised that institutionalized persons have legal persons as guarantors—presumably the legal persons that manage the place where the person is institutionalized. This is in contradiction with the standard of legal capacity, since the support must be freely chosen and not assumed.

3.3. Reforms within Disability Laws

Since the entry into the force of the CRDP, Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic and El Salvador have issued disability laws that contain a formal recognition of legal capacity on an equal basis with others. Nicaragua included such a recognition in Article 24 of its Law on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities of 2011. It establishes that “the full legal capacity of persons with disabilities” is recognized. The norm indicates that this implies the right to be recognized as persons before the law, to sign contracts, to represent themselves legally, to own and inherit assets, to control their own economic affairs, and to access loans, among others. It also indicates that mechanisms for the exercise of these rights will be established in the laws of the matter.

In the Dominican Republic, Article 23 of the Organic Law on Equal Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Law 5–13 of 2013, recognizes the obligation to ensure that persons with disabilities enjoy legal capacity. More recently, in El Salvador, Decree 672, the Special Law for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities of 2020, establishes in its Article 7.d) that persons with disabilities have the right to legal capacity. In addition, Article 29 establishes that the State must create a support mechanism for the exercise of rights and the decision-making process, which guarantees respect for the autonomy, will, preferences and interests of the person.

Notwithstanding the importance of these laws, they do need a later development and currently coexist with contradictory constitutional and private law provisions. Even though the disability laws are subsequent to civil codes, as this is the specific regulatory body in terms of legal capacity, its provisions cannot be understood as repealed. In Nicaragua, for example, Article 153 of the constitution establishes that citizenship is suspended due to declared incapacity when the person cannot act freely or discern. In a complementary way, the Civil Code establishes in its Article 7 that the insane and deaf–mutes who cannot make themselves understood in writing are absolutely incapable and may be subject to custody or interdiction13. The Dominican Civil Code states that adults “in a habitual state of imbecility, mental alienation or madness” (sic.) must be subject to an interdiction regime14 and maintains an interdiction process15, after which the subsequent acts of the person with disabilities will be null and void16. Finally, in El Salvador, the 1993 family code and the Civil Code contain provisions that indicate that people with mental disabilities and deaf people who “cannot undoubtedly make themselves understood” are incapable17, and also maintain a guardianship process18 that suspends citizenship rights19.

3.4. Jurisprudential Change

When a revolutionary change is needed in law, high courts may play a significant role by speeding up the process, forcing some actors to operate in a different way even if there is no legal regulation, and establishing new rules for the debate. Even though, at the moment of writing this paper, the Congress of Mexico City is debating a bill to reform its civil code to recognize the legal capacity of persons with disabilities (Human Rights Watch 2023), Mexico has not ruled on any regulation on legal capacity. It is a federal state in which every state has its own civil code, and all of those civil codes maintain interdiction systems. However, the Supreme Court of Justice of Mexico (SCJN) has played a key role in protecting the legal capacity of persons with disabilities through conventionality control. Prior to 2021, it issued several decisions protecting the legal capacity of persons with disabilities (Amparo Directo en Revisión 44/2018 2019; Amparo Directo en Revisión 8389/2018 2019), Quejosa: Bertha Romo Cornejo. Recurrente Elba Yolanda López Pérez (Tercera interesada); (Amparo en Revisión 702/2018 2019), Quejosos y recurrentes: Jesús Enríque Vázquez Quiroz y otros; (Acción de Inconstitucionalidad 90/2018 2020), Promovente: Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos; and (Amparo en Revisión 1082/2019 2020).

In that year, Mexico enacted a human rights reform that made it easier for courts to create precedents. Then, on 16 June 2021, the SCJN issued a precedent on the matter. In the judgment for Amparo Directo 4/2021 (Amparo Directo 4/2021 2021), the SCJN ruled in favor of a person under guardianship who asked for its termination, dismissing the idea that a person needs to undergo medical examinations in order to determine her legal capacity. After that, it issued two similar judgments (Amparo Directo en Revisión 1533/2020 2021; Amparo en Revisión 356/2020 2022). More recently, in 2022, the SCJN decided on the case of a woman under guardianship. In that judgment, the SCJN determined that several norms of the Mexico City Civil Code and Civil Procedure Code were contrary to CRPD norms and, thus, unconstitutional (Amparo en Revisión 356/2020 2022, p. 78). In that decision, the SCJN emphasized that its previous decision (Amparo Directo 4/2021 2021) should be considered as the precedent, giving it an erga omnes effect.

Despite this tremendous accomplishment of the judiciary, in our opinion, the programmatic nature of Article 12 of the CRPD and the support and safeguards system requires further legislation in order to become functional.20 Without it, the possibilities of compliance are low because judges could just rename a “guardian” as a “support,” and only the persons that file an amparo (a special process in Latin American law for challenging the constitutionality of an act or rule) could achieve real protection of their rights. Additionally, other legal operators besides judges may feel that the precedent is not relevant for them, such as notaries or medical practitioners.

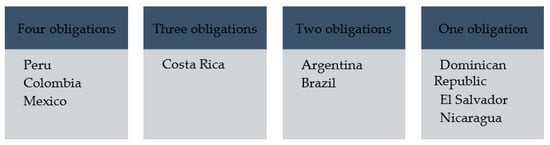

In this section, reforms have been presented through their source. Besides that, it is possible to appreciate a divergence in the compliance with the obligations determined by Article 12 of the CRPD. As mentioned before, the obligations contained in Article 12 are as follows: (i) recognizing legal capacity, (ii) abolishing guardianship, (iii) providing voluntary supports and (iv) guaranteeing safeguards. We can determine the compliance by analyzing how many obligations each country has met. In Table 1, we provide a systematization of such duties.

Table 1.

The categorization of nations according to the scope of their obligations.

4. A Framework for Analyzing the Reforms

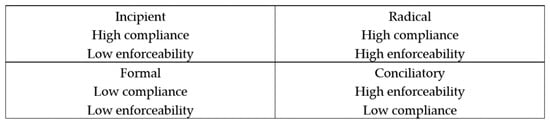

In this section, we will propose a framework for understanding and classifying the reforms according to the information described previously. This will allow us to classify the reforms depending on two main characteristics: compliance and enforceability. On the one hand, compliance in international human rights law refers to if and how States implement treaty obligations and the decisions of international human rights institutions (Grugel and Peruzzotti 2012). In the case of Article 12 CRPD, the evaluation of the compliance has to do with how many of the previously referred obligations have been legislated by countries. By reorganizing the countries in Figure 1 in the order of the number of obligations with which they have complied, we obtained the following order:

Figure 1.

The classification of countries based on the quantity of obligations that each nation has assumed.

On the other hand, enforceability refers to the provisions to guarantee that persons act with a certain degree of conformity to the law (McNeilly 1968). In this case, it is related to the possibility of legal operators to comply with or obey the changes in the reforms. If legal operators can avoid the reformed laws, they will be less enforceable. If they have to obey, they are more enforceable. In this order of ideas, modifying the civil code makes the reform more likely to resist pushback, since the civil code is usually the root for understanding private law. A specific law with a general scope is also strong. However, as in the Costa Rican case, even if many norms change, keeping the civil code untouched opens the door for contradictions. Then, judicial precedent may be of great help for future change, but in most cases, it may only apply to those who go through a judicial process. Its value is to act as a tool for change. Finally, reforms within disability laws tend to be significant from a symbolic point of view, but irrelevant from a practical one, since they do not change any operating rule.

By combining both axes, enforceability and compliance, we created a matrix for analyzing and understanding the reforms (Figure 2). According to this, reforms that meet the requirement of high compliance and high enforceability are considered radical since the changes in private law are thorough. Reforms with a high enforceability, but a low compliance are deemed as conciliatory since they try to include some of the minimal CRPD demands without modifying every aspect of private law. Reforms with a high compliance, but a low enforceability are called incipient, since they are in an early stage of the regulation process. Finally, reforms with low compliance and low enforceability are simply formal: they do not bring any real change. However, they could be the first steps towards bigger changes.

Figure 2.

A matrix for analyzing and understanding the reforms carried out in Latin America.

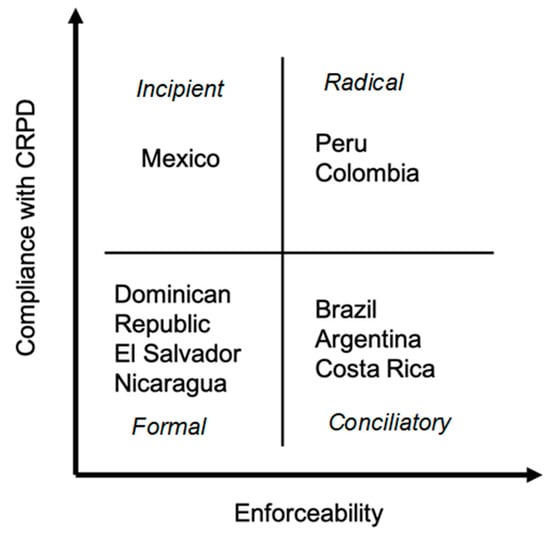

By applying this matrix to the Latin American reforms (Figure 3), we found the following results:

Figure 3.

Latin American reforms organized according to Compliance with CRPD and Enforceability.

The Dominican Republic, El Salvador and Nicaragua have formal reforms. They do recognize legal capacity in their disability laws. However, this is insufficient in order to guarantee voting rights, medical consent, marriage, access to justice or any other right. Few if no legal operators would prefer a law over the civil code. In that sense, these reforms are ineffective. However, they could be the first step towards a greater change, such as in the Peruvian case.

Mexico is the only country with an incipient reform. Despite the fact that the SCJN has recognized the need to eliminate guardianship and has called for a support-system provision and safeguards, its decisions have not changed the rules of private law. Moreover, in the Mexican experience, the decisions of the SCJN have created academic debates on what should be next steps regarding legal capacity (Núñez Escobar 2017; Herrera Gil 2020) and, as mentioned before, nowadays the Congress of Mexico City is discussing changes in its civil code.

Brazil, Argentina and Costa Rica have made conciliatory reforms. Even though these reforms modify some institutions of capacity, they do not eliminate all the incapacity rules from the civil code. That is the conciliation. As a matter of fact, Costa Rica eliminated guardianship, but did not modify its Civil Code. As a result, several legal capacity restrictions remained. Meanwhile, Brazil and Argentina created a support system, but did not abolish guardianship. However, the conciliation may be seen as temporary and not necessarily final. Future change is expected.

Finally, Peru and Colombia have made radical reforms. Both made a complex modification to their civil codes and other significant bodies. At the same time, they tried to comply the most with the CRPD. Their reforms eliminate disability-based guardianship, provide voluntary supports and establish safeguards. However, the stronger enforceability does not eliminate all the obstacles. In the context of a very conservative private law practice, radical reforms have dealt with pushback, precisely because of the changes in civil codes. Most legal operators dislike radical changes. In Peru, the reform was called defective and was compared to a virus (Espinoza Espinoza and Peralta Castellano 2020) or to Frankenstein’s monster (Vega Mere 2018). In Colombia, the constitutionality of the reform has been challenged at least eight times (Vásquez et al. 2022, pp. 217–18). In this scenario, the role of the judiciary is key. In the first place, high courts need to protect the reforms (Bolaños Salazar 2019; Vásquez et al. 2022, pp. 217–18) and lower courts need to apply them correctly. Nevertheless, in these cases, the change in mentality is usually slower than the change in rules; thus, decisions may not necessarily comply with the CRPD (Bregaglio Lazarte and Constantino Caycho 2023).

5. Conclusions

Legal capacity reforms in Latin America have brought an enormous change to different areas: private law, health law and sexual consent. By creating a typology, we are trying to predict possible problems in the enactment or implementation of future reforms. Without allies (such as a progressive judiciary or academia), organizations of persons with disabilities will have a difficult time achieving enforceable reforms. Without support after the enactment, those same reforms may dilute without a proper process of implementation. The four-speed idea means that countries may start reforms in one place and then speed up their changes. We believe that these lessons can help to achieve the implementation of legal capacity in other places. By creating feasible and ambitious reforms in the civil law systems, Latin American States are leading the way for other civil law countries, such as most of the European ones. However, their leadership and ambition can also become a catalyst for other Global South countries to create reforms in their own terms, without relying solely on the Global North’s norms and doctrines. Hopefully, these reforms are evidence of an unstoppable change that will eventually arrive to all Latin American countries and the entire world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.C.C. and R.A.B.L.; methodology, R.A.C.C. and R.A.B.L.; investigation, R.A.C.C. and R.A.B.L.; data curation R.A.C.C. and R.A.B.L.; writing-original draft preparation, R.A.C.C. and R.A.B.L.; writing-review and editing, R.A.C.C. and R.A.B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acción de Inconstitucionalidad 90/2018. 2020. Promovente: Comisión Nacional de los Derehcos Humanos, (Pleno January 30, 2020). Available online: https://www.cndh.org.mx/sites/default/files/doc/Acciones/Acc_Inc_2018_90.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Amparo Directo 4/2021. 2021. (Primera Sala June 16, 2021). Available online: https://www.scjn.gob.mx/sites/default/files/listas/documento_dos/2021-06/AD-4-2021-09062021.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Amparo Directo en Revisión 44/2018. 2019. (Primera Sala March 13, 2019). Available online: https://www.scjn.gob.mx/sites/default/files/listas/documento_dos/2019-02/ADR-44-2018-190207.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Amparo Directo en Revisión 1533/2020. 2021. (Primera Sala October 27, 2021). Available online: https://www.scjn.gob.mx/sites/default/files/listas/documento_dos/2021-10/ADR-1533-2020-20102021.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Amparo Directo en Revisión 8389/2018. 2019. Quejosa: Bertha Romo Cornejo. Recurrente Elba Yolanda López Pérez (Tercera interesada), (Primera Sala May 8, 2019). Available online: https://www.scjn.gob.mx/sites/default/files/listas/documento_dos/2019-04/ADR-8389-2018-190431.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- Amparo en Revisión 356/2020. 2022. (Primera Sala August 24, 2022). Available online: https://www.scjn.gob.mx/sites/default/files/listas/documento_dos/2021-08/AR-356-2020-16082021.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Amparo en Revisión 702/2018. 2019. Quejosos y recurrentes: Jesús Enríque Vázquez Quiroz y otros, (Primera Sala de la Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación de México September 11, 2019). Available online: https://www.scjn.gob.mx/sites/default/files/listas/documento_dos/2019-09/AR-702-2018-190912.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Amparo en Revisión 1082/2019. 2020. (Primera Sala May 20, 2020). Available online: https://www.scjn.gob.mx/sites/default/files/listas/documento_dos/2020-05/AR-1082-2019-200513.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Bezerra de Menezes, Joyceane, Francisco Luciano Lima Rodrigues, and Maria Celina Bodin de Moraes. 2021a. A Capacidade Civil e o Sistema de Apoios No Brasil. In Capacidade Jurídica, Deficiência e Direito Civil Na América Latina, 1st ed. Edited by Joyceane Bezerra de Menezes, Renato Antonio Constantino Caycho and Francisco José Bariffi. Indaituba: Editora Foco. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra de Menezes, Joyceane, Renato Antonio Constantino Caycho, and Francisco José Bariffi, eds. 2021b. Capacidade Jurídica, Deficiência e Direito Civil Na América Latina, 1st ed. Indaituba: Editora Foco. [Google Scholar]

- Bolaños Salazar, Elard Ricardo. 2019. Constitucionalizar la discapacidad. Gaceta Constitucional 140: 143–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla Maldonado, Daniel, ed. 2015. Geopolítica Del Conocimiento Jurídico. Biblioteca Universitaria Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades. Filosofía Política y Del Derecho. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, Siglo del Hombre Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Bregaglio Lazarte, Renata Anahí, and Renato Antonio Constantino Caycho. 2023. La Capacidad Jurídica En La Jurisprudencia Peruana. Análisis Cualitativo de Las Decisiones Judiciales de Restitución de Capacidad Jurídica y Designaciones de Apoyo En Aplicación Del Decreto Legislativo 1384. Revista de Derecho Privado 44: 15–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregaglio Lazarte, Renata. 2021. Marco Legal de Los Derechos de Las Personas Con Discapacidad: América Latina y El Caribe. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2013. General Comment on Article 12: Equal Recognition as a Person before the Law. Draft Prepared by the Committee, CRPD/C/11/4. Geneva: Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2014. General Comment No. 1 (2014) Article 12: Equal Recognition before the Law. Geneva: Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2016. Views Adopted by the Committee under Article 5 of the Optional Protocol, Concerning Communication No. 7/2012—CRPD/C/16/D/7/2012. Geneva: Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://docstore.ohchr.org/SelfServices/FilesHandler.ashx?enc=6QkG1d%2FPPRiCAqhKb7yhsu6NW3bG83XvqI3UJbggyL2AlnGNsIfeu6Zl%2FMadZhl5%2FGm1g4ZDu4vfK3%2FRw1Ct5oe0rTucVjRE0Xf%2BlKX8mkQ2EuS5iXvHJx0K8Ge6g4lbYTKgf0nGMFEq118Lu%2BL4Uw%3D%3D (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Constantino Caycho, Renato Antonio. 2020. The Flag of Imagination: Peru’s New Reform on Legal Capacity for Persons with Intellectual and Psychosocial Disabilities and the Need for New Understandings in Private Law. The Age of Human Rights Journal 14: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino Caycho, Renato Antonio, and Renata Anahí Bregaglio Lazarte. 2022. Las Salvaguardias Para El Ejercicio de Capacidad Jurídica de Personas Con Discapacidad Como Una Forma de Paternalismo Justificado. In Capacidad Jurídica, Discapacidad y Derechos Humanos. Edited by Nicolás Espejo Yaksic and Michael Bach. Ciudad de México: Centro de Estudios Constitucionales—Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación. Available online: https://www.scjn.gob.mx/derechos-humanos/publicaciones-dh/capacidad-juridica-discapacidad-derechos (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- David, René. 1985. Major Legal Systems in the World Today: An Introduction to the Comparative Study of Law, 3rd ed. Translated by John E. C. Brierley. London: Stevens. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, John. 2015. A Realistic Approach to Assessing Mental Health Laws’ Compliance with the UNCRPD. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 40: 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Salas Murillo, Sofía. 2022. El Nuevo Sistema de Apoyos Para El Ejercicio de La Capacidad Jurídica En La Ley Española 8/2021, de 2 de Junio: Panorámica General, Interrogantes y Retos. Actualidad Jurídica Iberoamericana 17: 16–47. Available online: https://revista-aji.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/01.-Sofia-de-Salas-pp.-16-47.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- Devandas, Catalina. 2017. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. A/HRC/37/56. New York and Geneva: United Nations Humans Rights Council. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanda, Amita. 2007. Legal Capacity in the Disability Rights Convention: Stranglehold of the Past or Lodestar for the Future? Syracuse Journal of International Law & Commerce 34: 35. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanda, Amita. 2017. Conversations between the Proponents of the New Paradigm of Legal Capacity. International Journal of Law in Context 13: 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinerstein, Robert D. 2012. Implementing Legal Capacity Under Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: The Difficult Road From Guardianship to Supported Decision-Making. Human Rights Brief 19: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza Espinoza, Juan, and Juan Carlos Peralta Castellano. 2020. El Mal Diseñado Sistema de Apoyos y Salvaguardias: El Otro Virus Que Trajo El Decreto Legislativo N.° 1384 y Ha Contagiado al Código Civil Peruano. Actualidad Civil 71: 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, George P. 2001. Three Nearly Sacred Books in Western Law. Arkansas Law Review 54: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Grugel, Jean, and Enrique Peruzzotti. 2012. The Domestic Politics of International Human Rights Law: Implementing the Convention on the Rights of the Child in Ecuador, Chile, and Argentina. Human Rights Quarterly 34: 178–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera Gil, Mariana. 2020. El Derecho Humano al Pleno Reconocimiento de la Capacidad Jurídica de las Personas con Discapacidad, La Agenda Pendiente de México. Revista Latinoamericana en Discapacidad, Sociedad y Derechos Humanos 4: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. 2023. Mexico: Bill to Support People With Disabilities and Older Persons. Guarantee Everyone’s Right to Make Their Own Decisions. Human Rights Watch (Blog). February 15. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/02/15/mexico-bill-support-people-disabilities-and-older-persons (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Isaza Piedrahita, Federico. 2021. La Ley 1996 de 2019: Una Aproximación General a La Reforma Derivada Del Artículo 12 de La CDPD En Colombia. In Capacidade Jurídica, Deficiência e Direito Civil Na América Latina, 1st ed. Edited by Joyceane Bezerra de Menezes, Renato Antonio Constantino Caycho and Francisco José Bariffi. Indaituba: Editora Foco. [Google Scholar]

- Kraut, Alfredo, and Agustina Palacios. 2014. Artículo 32. In Código Civil y Comercial de La Nación Comentado. Edited by Ricardo Lorenzetti. Buenos Aires: Rubinzal-Culzoni Editores, pp. 125–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lafferrière, Jorge Nicolás. 2021. La Reforma de La Ley Española En Materia de Capacidad Jurídica: Una Comparación Con Argentina. Jurisprudencia Argentina 3: 11. [Google Scholar]

- López Medina, Diego Eduardo. 2004. Teoría impura del derecho: La transformación de la cultura jurídica latinoamericana, Primera ed. México D.F.: Legis. [Google Scholar]

- Mariátegui, José Carlos. 1928. Aniversario y Balance. Amauta, September 15. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, Pablo, Paula Vásquez, Violeta Purán, and Loreto Godoy. 2023. Are We Closing the Gap? Reforms to Legal Capacity in Latin America in Light of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 56: 119. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Wayne, Sabine Michalowski, Jill Stavert, Adrian Ward, Alex Ruck Keene, Colin Caughey, Alison Hempsey, and Rebecca Mcgregor. 2016. Three Jurisdictions Report. Towards Compliance with CRPD Art. 12 in Capacity/Incapacity Legislation across the UK (p. 111). Essex Autonomy Project. Available online: https://autonomy.essex.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/EAP-3J-Final-Report-2016.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Martinez-Pujalte, Antonio. 2019. Legal Capacity and Supported Decision-Making: Lessons from Some Recent Legal Reforms. Laws 8: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeilly, F. S. 1968. The Enforceability of Law. Noûs 2: 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSherry, Bernadette. 2008. Protecting the Integrity of the Person: Developing Limitations on Involuntary Treatment. Law Context: A Socio-Legal Journal 15: 111–24. [Google Scholar]

- Minkowitz, Tina. 2013. CRPD Article 12 and the Alternative to Functional Capacity: Preliminary Thoughts Towards Transformation. SSRN Electronic Journal 1: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez Escobar, Alejandra Donají. 2017. La Capacidad Jurídica de las Personas con Discapacidad, Interpretaciones de la Segunda Sala de la Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación al Primer Párrafo del Artículo 8° de la Ley de Amparo en México. Revista Latinoamericana en Discapacidad, Sociedad y Derechos Humanos 1: 1. Available online: http://redcdpd.net/revista/index.php/revista/article/view/41/13 (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Quijano, Aníbal. 2007. Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality. Cultural Studies 21: 168–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Series, Lucy, and Anna Nilsson. 2018. Article 12 CRPD. Equal Recognition before the Law. In The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, a Commentary, 1st ed. Edited by Ilias Bantekas, Michael Ashley Stein and Dēmētrēs Anastasiou. Oxford Commentaries on International Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Series, Lucy. 2014. Comments on Draft General Comment on Article 12—The Right to Equal Recognition before the Law. Cardiff: Cardiff Law School. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/HRBodies/CRPD/GC/LucySeriesArt12.doc (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Szmukler, George. 2017. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: ‘Rights, Will and Preferences’ in Relation to Mental Health Disabilities. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 54: 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vásquez, Alberto, Federico Isaza, and Andrea Parra. 2022. Reformas Legales a Los Regímenes de Capacidad Jurídica. Un Análisis Comparativo y Crítico de Costa Rica, Perú y Colombia. In Capacidad Jurídica, Discapacidad y Derechos Humanos. Edited by Nicolás Espejo Yaksic and Michael Bach. Ciudad de México: Centro de Estudios Constitucionales—Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación. Available online: https://www.scjn.gob.mx/derechos-humanos/publicaciones-dh/capacidad-juridica-discapacidad-derechos (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Vega Mere, Yuri. 2018. La reforma del régimen legal de los sujetos débiles made by Mary Shelley: Notas al margen de una novela que no pudo tener peor final. Gaceta Civil & Procesal Civil 64: 19. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For more information on it, please see (De Salas Murillo 2022; Lafferrière 2021). |

| 2 | In this paper, we understand legal capacity as both “the ability to hold rights and duties (legal standing) and to exercise those rights and duties (legal agency)” (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2014, p. 12). |

| 3 | At the regional level, the right to legal personality is recognized in Article 3 of the American Convention on Human Rights. At a universal level, it is in Article 16 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 12 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 24 of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and their Families and 15 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. |

| 4 | Persons with disabilities are a broad collective. In this document, references to people with disabilities refer mainly to people with intellectual disabilities and people with psychosocial disabilities, who are the ones that face the most barriers in the exercise of their legal capacity. |

| 5 | Article 59 of Law 603 of 2014, Code of Families and Family Process; Article 5 of the Civil Code. |

| 6 | Most of the information comes from (Bregaglio Lazarte 2021). |

| 7 | Article 32—Person with restricted capacity and disability. The judge may restrict the capacity for certain acts of a person over the age of thirteen who suffers from an addiction or a permanent or prolonged mental disorder, of sufficient severity, provided that he deems that the exercise of his full capacity may result in harm to his person or to their assets. In relation to said acts, the judge must designate the necessary support or supports provided for in Article 43, specifying the functions with reasonable adjustments based on the needs and circumstances of the person. The designated support(s) must promote autonomy and favor decisions that respond to the preferences of the protected person. As an exception, when the person is absolutely unable to interact with their environment and express their will by any suitable means or format and the support system is ineffective, the judge can declare incapacity and appoint a curator. |

| 8 | Article 569-D of the Civil Code of 1984, modified by Legislative Decree 1384 of 2018. |

| 9 | Article 569-F of the Civil Code of 1984, modified by Legislative Decree 1384 of 2018. |

| 10 | Article 569-E of the Civil Code of 1984, modified by Legislative Decree 1384 of 2018. |

| 11 | Article 21 of Law 1996 of 2019. |

| 12 | Article 38 of Law 1996 of 2019. |

| 13 | Article 298 of the Civil Code of Nicaragua. |

| 14 | Article 489 of the Civil Code of the Dominican Republic. |

| 15 | Articles 490 and 491 of the Civil Code of the Dominican Republic. |

| 16 | Article 502 of the Civil Code of the Dominican Republic. |

| 17 | Article 293 of Decree 677 of 1993, Family Code; Article 1318 of the Civil Code of 1860. |

| 18 | Article 291 and 292 of Decree 677 of 1993, Family Code. |

| 19 | Article 74 of the Constitution; Articles 1318, 1341, 1555 and 762 of the Civil Code of 1860. |

| 20 | During the edition of this paper, the Mexican Parliament approved a new Code of Civil and Family Procedures that will recognize legal capacity of persons with disabilities, abolish guardianship and create a procedure for the establishment of supports and safeguards. Such reform has not been enacted yet. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).