Abstract

Bioinformatics is a scientific field that uses computer technology to gather, store, analyze, and share biological data and information. DNA sequences of genes or entire genomes, protein amino acid sequences, nucleic acid, and protein–nucleic acid complex structures are examples of traditional bioinformatics data. Moreover, proteomics, the distribution of proteins in cells, interactomics, the patterns of interactions between proteins and nucleic acids, and metabolomics, the types and patterns of small-molecule transformations by the biochemical pathways in cells, are further data streams. Currently, the objectives of bioinformatics are integrative, focusing on how various data combinations might be utilized to comprehend organisms and diseases. Bioinformatic techniques have become popular as novel instruments for examining the fundamental mechanisms behind neonatal diseases. In the first few weeks of newborn life, these methods can be utilized in conjunction with clinical data to identify the most vulnerable neonates and to gain a better understanding of certain mortalities, including respiratory distress, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, sepsis, or inborn errors of metabolism. In the current study, we performed a literature review to summarize the current application of bioinformatics in neonatal medicine. Our aim was to provide evidence that could supply novel insights into the underlying mechanism of neonatal pathophysiology and could be used as an early diagnostic tool in neonatal care.

1. Introduction

Bioinformatics is a scientific field that uses computer technology to gather, store, analyze, and share biological data and information. It is a multidisciplinary field integrating biology, physics, mathematics, and computer science [1]. The types of data that bioinformatics use include DNA sequences of genes or entire genomes, protein amino acid sequences, nucleic acid, and protein–nucleic acid complex structures. Moreover, further data streams include proteomics, the distribution of proteins in cells, interactomics, the patterns of interactions between proteins and nucleic acids, and metabolomics, the types and patterns of small-molecule transformations by the biochemical pathways in cells. Currently, the objectives of bioinformatics are integrative, focusing on how various data combinations might be utilized to comprehend organisms and diseases. Due to the latest developments in the reading of DNA sequences, the difficulty in obtaining information has decreased, yet the comprehension and interpretation of the gathered data are still challenging. Considering the enormous size of the collected datasets, computer-based methods are currently the standard methods of interpretation and analysis.

Bioinformatic techniques have become popular as novel instruments for examining the fundamental mechanisms behind neonatal diseases. In the first few weeks of newborn life, these methods can be utilized in conjunction with clinical data to identify the most vulnerable neonates and to gain a better understanding of certain mortalities, including respiratory diseases, sepsis, or inborn errors of metabolism [2,3,4]. Reviews of the application of bioinformatics to neonatal care are scarce, and this review aims to cover this important issue. In the current study, we performed a narrative literature review to summarize the current application of bioinformatics in neonatal medicine. Our aim was to provide evidence that could supply novel insights into the underlying mechanism of neonatal pathophysiology and could be used as an early diagnostic tool in neonatal care.

Our study is organized into (1) presenting the basic principles of bioinformatics, (2) grouping bioinformatics that pertain to neonatology into domains, elucidating their sub-domains, and highlighting the key components of the relevant studies, (3) reviewing and providing a thorough summary of the latest research to all areas of neonatology, and (4) examining and discussing the existing challenges related to bioinformatics in neonatology, as well as directions for future study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the study organization.

2. Basic Principles of Bioinformatics

2.1. Bioinformatic Analysis

Bioinformatics is primarily based on the internet and computer software, while a basic activity is the sequence analysis of proteins and DNA using different online databases and programs. Bioinformatics has expanded globally, establishing computer networks that facilitate the straightforward retrieval of biological data and the creation of software applications for analysis. Numerous global initiatives are underway to make gene and protein databases openly accessible online to the entire scientific community [1].

The growing volume of data resulting from genome research has made computer databases with quick assimilation, reusable formats, and algorithm software programs essential for effective biological data management [5]. Due to the diversity of new data, it is not possible to access all of this information in a single, complete database. Examples include websites that offer in-depth explanations of clinical conditions, a list of genetic mutations and polymorphisms associated with illness susceptibility, and the ability to search for disease genes based on a DNA sequence.

2.2. Bioinformatics Databases

To guarantee data transparency and traceability, several international collaborations and databases, or biorepositories, have been established [6]. These datasets are frequently combined to assist scientists in moving from identifying genetic alterations to figuring out which biochemical pathways the questioned genes are part of. These pathways assist in explaining the underlying physiology and give context to the findings. To name a few examples of databases and websites, the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), the European Nucleotide Archive, the Gene Ontology (GO), the Ensembl, the Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) catalog, the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), the SWISS-PROT, and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) are frequently referenced in the literature (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of bioinformatic databases and websites.

2.3. Functional Genomics

Functional genomics is the study and interpretation of biological data at the level of the transcriptome, proteome, and genome [7]. Clinical research and the molecular knowledge of diseases have made bioinformatics increasingly visible. Notably, this field covers several “omics” disciplines that enable a more thorough examination of biological systems, including proteomics (the study of proteins), metabolomics (the research of metabolites), transcriptomics (the study of transcripts), and genomics (the study of DNA), whereas more specialized disciplines, such as metagenomics, combine the study of the human genome with other organisms, such as bacteria, viruses, etc., and epigenomics studies epigenetic alterations of DNA [8]. For a more comprehensive examination, these distinct “omics” fields are frequently integrated and referred to as “multi-omics” or “panomics”.

Moreover, the DNA microarray technique incorporates genotyping and DNA sequencing and determines the degree of gene expression. In addition to analyzing genome sequence data, bioinformatics is currently being used for a wide range of other significant tasks, such as analyzing gene expression and variation, predicting and analyzing the structure and function of genes and proteins, identifying and predicting gene regulation networks, simulating whole-cell environments, modeling complex gene regulatory dynamics and networks, and presenting and analyzing molecular pathways to comprehend gene–disease interactions [9]. In bioinformatic protein research, a database of two-dimensional electrophoresis and annotated proteins is used, in order to predict the protein’s structure once it has been separated, identified, and characterized. Structural biologists also employ bioinformatics to manage the massive and complex data when creating three-dimensional models of molecules using electron microscopy, nuclear magnetic resonance, and X-ray crystallography [10]. Simpler bioinformatic activities, albeit on a lesser scale, that are useful to the clinical researcher can range from predicting the function of gene products to developing primers, which are short oligonucleotide sequences required for DNA amplification in polymerase chain reaction assays.

2.4. Translational Bioinformatics

The outcome of translational bioinformatics is “the transformation of increasingly voluminous biomedical data, and genomic data, into proactive, predictive, preventive, and participatory health”, according to the American Medical Informatics Association [11]. “Proact” refers to taking proactive measures to address a change or challenge that is anticipated. Even when there is not enough data to support a particular clinical choice, there is still another chance to use a proactive strategy to personalize care. “Predict” refers to stating or making known something before it is presented clinically, particularly by inference or specialized knowledge. Characteristics of the model itself may aid in improving the comprehension of the pathophysiology of a disease or in identifying hazardous behaviors that may be involved. “Prevent” describes actions that impede or lessen the progression of a disease. Prevention of prematurity is likely the best example of preventive treatment in the field of neonatology, even though there is some overlap in the care that is seen as proactive, predictive, and preventive. Finally, “participation” refers to when people, groups, and organizations are consulted about a project or program of activity or given the chance to actively participate in it [12].

3. Bioinformatics in Neonatal Medicine

3.1. Methods

Literature Search Strategy

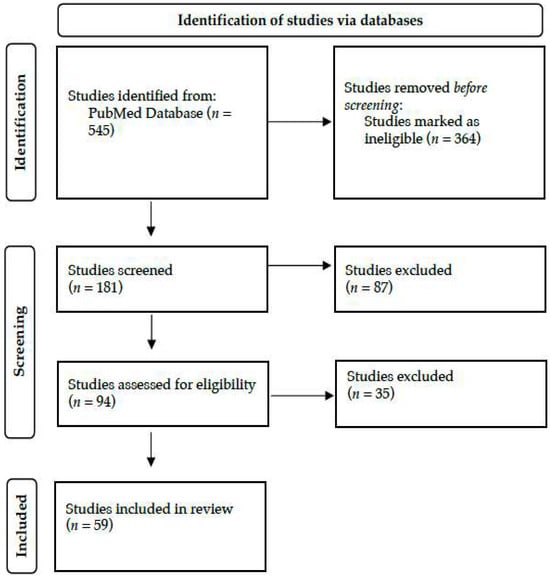

A literature search was conducted by two researchers in June 2024 in PubMed. Only human studies and English-language articles were taken into account. The terms ‘biomedical informatics’ OR ‘bioinformatics’ OR ‘computational biology’ OR ‘Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes’ OR ‘Genomes’ OR ‘Gene Ontology’ OR ‘Genome-wide association study’ OR ‘Biotechnology Information’ OR ‘gene dataset’ OR ‘SWISS-MODEL’ AND ‘neonate’ OR ‘newborn’ OR ‘infant’ OR ‘Neonatal Intensive Care Unit’ OR ‘Neonatology’ in the title or abstract were utilized. The studies that were retrieved were assessed according to their titles, abstracts, and suitability for the review. As outlined in Figure 2, 59 out of 545 studies were selected and included in this narrative review.

Figure 2.

Literature search strategy and study selection, adopted by the PRISMA flow chart.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Applications of Bioinformatics in Neonatal Respiratory Diseases

- Respiratory distress syndrome

Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) is very common among preterm neonates. Previously, Zhou et al., in 2021, explored the connection between circular RNA (circRNA) and the expression profile of circRNAs and RDS, performing high-throughput sequencing, and analysis with GO and KEGG [13]. The authors found 30 enriched KEGG pathways of 125 target genes engaged in the production and release of endocrine hormones associated with the development of RDS (Table 2) [13]. Overall, although additional molecular biology validation is required to precisely identify the function of differentially expressed circRNAs in neonatal RDS, circRNAs may serve as molecular markers for early RDS diagnosis, offering potential novel treatment options [13].

Table 2.

Original studies in neonatal respiratory diseases.

- Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

More extensively, bioinformatics analysis has been applied to the investigation of genetic variation associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in preterm neonates (Table 2). By employing a DNA pooling technique on newborns with African and White ancestry, Hadchouel et al. discovered the SPOCK2 gene as a novel, potentially susceptible gene for BPD [14]. Furthermore, Wang et al. used a GWAS in 2013 to analyze genomic DNA from newborn screening bloodspots and find genetic variations linked to the risk for BPD [15]. The authors analyzed samples from 1726 neonates, but they were not able to identify genomic loci or pathways that could explain BPD. The study’s results could be explained by genetic variants that were mapped to a large number of distributed loci, race and ethnicity, or the study population’s sample size [15]. In 2015, Ambalavanan et al. used a GWAS to locate single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and pathways linked to BPD [16]. The authors discovered that the genes miR-219 and CD44 were upregulated in the lungs of BPD patients as well as in relation to hyperoxia. A comparison of the pathways linked to mild/moderate and severe BPD revealed variations in these pathways, suggesting that these novel components and pathways may be involved in lung development and repair and genetic susceptibility to BPD [16]. Moreover, Mahlman et al., in 2017, performed a GWAS on preterm neonates (24–30 weeks of gestational age) and revealed that SNPs close to the C-reactive protein (CRP) gene were risk factors for BPD, independent of antenatal risk factors [17]. Therefore, the authors proposed a potential role for variants near CRP in BPD [17]. Yang et al. assessed the expression patterns of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) and angiogenesis-related genes (ARG) in neonates with and without BPD. Using the Gene-Cloud of the Biotechnology Information platform, the authors re-analyzed the GEO database dataset [18]. The study found that by interfering with the development of blood vessels, the up- and down-regulation of particular genes may increase the risk of BPD in preterm neonates [18]. Furthermore, Torgerson et al., in 2018, used ancestry studies and a GWAS to detect genes, pathways, and variants linked to survival in BPD neonates receiving inhaled nitric oxide [19]. Pathway analyses revealed variation in genes involved in immune/inflammatory processes in response to infection and mechanical ventilation, and examination of the genes upregulated in BPD lungs revealed an association with variants in a cytokine linked to fibrosis and interstitial lung disease [19]. Overall, the study indicated that genetic variations in immune response, drug metabolism, and lung development influence individual and racial/ethnic variations in respiratory outcomes when high-risk preterm neonates receive inhaled nitric oxide. Finally, using GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis, Wang et al. conducted a study to investigate differentially expressed exosomal circRNAs, long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), and messenger RNAs (mRNAs) in the umbilical cord blood of newborns with and without BPD [20]. The study’s conclusions demonstrated a substantial difference in expression in the exosomes obtained from umbilical cord blood between newborns with and without BPD, underscoring the possible biological roles of exosomal circRNAs and lncRNAs in BPD [20].

Nonetheless, whole-exome sequencing (WES) made it possible to investigate uncommon variations associated with BPD. In 2015, Carrera et al. identified potential candidate genes linked to the development of BPD by using WES in 26 unrelated newborns with severe BPD [21]. Among 3369 new variants found, the toll-like receptor family, NOS2, MMP1, CRP, LBP, and other top candidate genes were identified [21]. Furthermore, in 2022, Wang et al. performed an epigenome-wide association analysis in preterm neonates, utilizing cord blood DNA and DNA methylation techniques, providing insights into the molecular mechanisms involved in BPD etiology [22]. The study revealed that the incidence of stochastic epigenetic mutations at birth was considerably higher in patients with BPD, while changes in the transcriptome of cord blood cells were indicative of BPD disease [22]. In conclusion, the authors suggested that DNA methylation profiles in preterm cord blood were significantly altered by the nucleated red blood cell concentration, and epigenome-wide association study analysis provided possible insights into the molecular processes implicated in the pathophysiology of BPD [22].

In line with the development of genomics, proteomic analysis has also been used for identifying specific protein–BPD associations. Magagnotti et al., in 2013, discovered distinct variations in the proteomic profiles of preterm neonates born between 23–25 and 26–29 weeks of gestational age, as well as between neonates diagnosed with mild and severe BPD, utilizing proteome analysis in tracheal aspirates [23]. Also, Ahmed et al. performed proteomic analysis on the urine of neonates with BPD in a study that was published in 2022 [24]. They validated several proteins previously discovered in serum samples and tracheal aspirates that had been linked to the pathogenesis of BPD, providing a means of non-invasively tracking the disease’s progression over time [24]. The findings of the above studies could be used to help create new, successful treatments and therapeutic interventions for neonates with BPD in future studies.

- Cystic fibrosis

In 2024, Esposito et al. investigated whether newborn screening programs could aid in early identification and enhance the prognosis of neonates suffering from cystic fibrosis (Table 3) [25]. With the use of Sanger-sequencing-based molecular techniques and bioinformatics tools, the scientists were able to identify an Alu element insertion in exon 15 of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, which has a significant impact on splicing patterns, CFTR protein structure, and gene expression. In summary, the study underscored the significance of how the combination of contemporary technologies and human skills signified a crucial advancement in the field of genetic medicine [25].

Table 3.

Case-report studies in neonatal respiratory diseases.

3.2.2. Applications of Bioinformatics in Cardiovascular Disorders

Bioinformatics analysis has also been applied to the investigation of genetic variation and significant differences in genome-wide DNA methylation in neonates with congenital heart defects (CHD), as depicted in Table 4. When Bahado-Singh et al. analyzed the genome-wide DNA methylation of neonates with different CHDs, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome, ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, pulmonary stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, and Tetralogy of Fallot, they discovered significant variations in the cytosine methylation of hundreds of genes [26]. In 2020, the same group investigated whether isolated, non-syndromic coarctation of the aorta results in notable epigenetic alterations. Six artificial intelligence platforms, including deep learning, and biological and disease pathways that were epigenetically dysregulated were identified by the scientists using ingenious pathway analysis [27]. According to the study, the newborn blood spot might be used to accurately predict the coarctation of the aorta, and artificial intelligence and epigenomics could be utilized to accomplish key goals of precision cardiovascular therapy [27]. Similarly, to investigate the epigenetic alterations that occur in neonates with Tetralogy of Fallot, Radhakrishna et al. conducted a genome-wide methylation analysis [28]. Significant biological processes and functions associated with differentially methylated genes were found by GO analysis, which provided important insights into the pathophysiology of Tetralogy of Fallot [28]. Furthermore, Rashkin et al. utilized transmission/disequilibrium tests in complete case-parental trios and case-control analyses separately in infants and mothers to investigate the genetic architecture of obstructive heart diseases, and found an association between two specific SNPs and obstructive heart diseases [29]. In line with the previous authors, Mouat et al. [30], Huang et al. [31], and Wang et al. [32] investigated genetic variance and methylation differences in neonates with CHDs, indicating that bioinformatics may be useful for future efforts to improve genetic screening and patient counseling.

Table 4.

Original studies in neonatal cardiovascular disorders.

3.2.3. Applications of Bioinformatics in Neonatal Gastrointestinal Disorders

Several studies also explored the relation of human milk components with the development of gut microbiota (Table 5). Wang et al. recently investigated the expression of lactation-related miRNAs in microvesicles isolated from the umbilical cord blood, with Western blotting, transmission electron microscopy, and nanoparticle tracking analysis, while bioinformatics techniques for GO, miRNA target prediction, signaling pathway analysis, and lactation-related miRNAs were performed [33]. After profiling 337 miRNAs in human umbilical cord blood microvesicles, bioinformatics analysis revealed that 85 of them were connected to lactation [33]. According to the authors, umbilical cord blood microvesicles may play a significant role in fetal–maternal interaction by mediating β-casein secretion through miRNAs [33]. Similarly, Parnanen et al., in 2022, determined the impact of early exposure to formula on the antibiotic-resistance genes’ load, using a generalized linear model that was constructed using cross-sectionally sampled neonatal gut metagenomes to examine the effect of food on antibiotic-resistance genes’ loading in neonates, while neonatal metagenomes collected from public databases were used to cross-validate the model [34]. The study revealed that, when compared to neonates that were exclusively fed human milk, the formula-receiving group had a 69% greater relative abundance of antibiotic-resistance genes carried by gut bacteria [34]. Liu et al. more recently investigated the characteristics of gut microbiota dysbiosis and metabolite levels in very or extremely low-birth-weight neonates with white matter injury (WMI) by LC-MS/MS, diffusion tension imaging, and 16S rRNA gene sequencing as part of a multi-omics approach, and they found that there was a significant differential expression of 139 metabolic markers between WMI and non-WMI neonates [35]. Finally, Letourneau et al., in 2024, investigated the association between microbiome composition and biomarkers and the risk of developing specific diseases, and showed that neonates born earlier or exposed to antibiotics exhibited increased fecal pH and increased redox, while microbiome composition was also related to birth weight, gestational age, pH, and redox [36].

Table 5.

Original studies in neonatal gastrointestinal disorders.

Apart from the research on the gut microbiota, a recent study evaluated the role of bioinformatics analysis in detecting neonates at risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) (Table 5). Liu et al. explored the differentially expressed genes in neonates with NEC, using the GEO database, GEO2R, DAVID, and STRING to examine the roles, pathway enrichment, and protein interactions of the associated genes, while Cytoscape software (https://cytoscape.org/) was used to identify the important protein interaction modules and core network genes [37]. The findings showed that the differentially expressed genes that were upregulated were associated with protein dimerization activity, whereas the differentially expressed genes that were downregulated were associated with cholesterol transporter activity, suggesting that biological mechanisms and metabolic pathways might be crucial in the development of NEC [37]. Chen et al., in 2021, investigated the effects of human-milk-derived exosomes in the gut microbiota, revealing that the function of intestinal epithelial cells is regulated by the top 50 lipids through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK/MAPK) pathway [38]. The findings of the study revealed the lipidomic complexity in exosomes obtained from term and preterm milk and offered a new mechanistic understanding of how human milk inhibits the development of NEC [38]. Furthermore, Zhang et al. investigated biological function, pathways, transcription factors, and immune cells dysregulated in NEC using gene set enrichment analysis and found that both innate and adaptive immune systems may trigger the NEC-related inflammatory response [39]. Lastly, to examine biological and functional processes that may be involved in the pathophysiology of NEC, Tremblay et al. employed functional enrichments with the GO and the KEGG databases to evaluate earlier data [40]. The authors found that the most significant biological pathways that were over-represented in neonates with NEC were strongly related to innate immune systems. The study thus suggested that more research is necessary to precisely understand the function of inflammatory genes connected to the IL-17 pathway and its downstream targets in NEC [40].

Niu et al. used the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery to perform GO and KEGG pathway enrichment studies on differently expressed genes (DEGs) from public datasets in order to discover key genes involved in the development of Hirschsprung’s disease [41]. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis was used to create the co-expression network between lncRNAs and mRNAs. The authors proposed that hub mRNAs and hub lncRNAs may be involved in the development of Hirschsprung’s disease and that these genes may offer novel clinical indicators for assessing the disease’s risk [41]. Besides, Feng et al. explored the underlying mechanism of enteric neural precursor cells (ENPCs) and the ZEB2/Notch-1/Jagged-2 pathway in Hirschsprung’s-associated enterocolitis development by Western blot and RT-qPCR, while bioinformatics analysis and co-immunoprecipitation were utilized to investigate the ZEB2 and Notch-1 interaction [42]. It was found that Hirschsprung’s-associated enterocolitis colon tissues had higher levels of lipopolysaccharide, along with downregulated ZEB2 and elevated Notch-1/Jagged-2 expression. In lipopolysaccharide-induced ENPCs, overexpression of ZEB2 exacerbated inflammation and dysfunction while suppressing Notch-1/Jagged-2 signaling, thus playing a role in Hirschsprung’s-associated enterocolitis [42].

3.2.4. Applications of Bioinformatics in Neonatal Sepsis

Gene polymorphisms, biomarkers, and metabolomics have also been investigated in neonates with sepsis (Table 6). Mustarim et al. evaluated the association between several gene polymorphisms and the incidence of neonatal sepsis by PCR examination, sequencing, and bioinformatics analysis [43]. The authors found a significant correlation between the Interleukin 1β rs1143643 G>A gene polymorphism and the frequency of newborn sepsis [43]. Bu et al., evaluating upregulated and downregulated mRNAs and lncRNAs in neonatal sepsis, by constructing protein–protein interaction networks, demonstrated that neonatal sepsis was associated with 1128 upregulated and 1008 downregulated mRNAs, and 28 upregulated and 61 downregulated lncRNAs [44]. Thus, the findings could help detect new therapeutic markers for neonatal sepsis [44]. Navarrete et al. utilized two distinct bioinformatic approaches (a supervised and an unsupervised) using data from methylation arrays of leukocytes, and they managed to identify variation in DNA methylation traits in neonatal sepsis, as well as between neonates with early compared to late-onset sepsis [45]. Yan et al. tried to identify the optimal biomarkers in the progression of neonatal sepsis by gene set variation analysis (GSVA), CIBERSORT, receiver operating characteristic analysis, and the LASSO model [46]. The authors found that according to the GSVA data, differentially expressed genes mostly influenced the upregulation of metabolism-related activities and inflammation, as well as the suppression of adaptive immune responses in sepsis. Ultimately, three genes were shown to be important biomarkers for sepsis, providing novel insights into the pathogenesis and promising therapeutic options of neonatal sepsis [46]. Additionally, Ciesielski et al. conducted an exploratory GWAS to find genetic variations linked to late-onset sepsis and concluded that NOTCH signaling was over-represented based on pathway studies [47].

Table 6.

Original studies in neonatal sepsis.

Furthermore, Liu et al. investigated the characteristics of intestinal metabolomics and non-invasive biomarkers for late-onset sepsis by analyzing gut metabolites in preterm neonates and suggested that several metabolites (N-methyldopamine, cellulose, glycine, N-ribosylnicotinamide, Gamma-glutamyltryptophan, and 1-alpha, 25-dihydroxycholecalciferol) demonstrated distinct diagnostic values as non-invasive biomarkers for late-onset sepsis [48]. Also, Das et al., in 2024, examined the blood profile of very preterm neonates across episodes of sepsis with multi-parameter flow cytometry, single-cell RNA sequencing, and plasma analysis, and they found that a blood immune signature was present even in cases where CRP was normal. Single-cell RNA sequencing revealed elevation of amphiregulin in leukocyte populations during sepsis, which was associated with clinical indications of disease [49]. Furthermore, utilizing the GEO public repository to extract programmed cell death (PCD)-related genes from 12 distinct patterns and sophisticated machine learning methods, such as LASSO, support vector machine-recursive feature elimination (SVM-RFE), protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks, artificial neural networks, and consensus clustering, Hang et al. investigated whether PCD could function as a marker for diagnosing neonatal sepsis [50]. According to the study, the competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network showed a complex regulatory interplay based on the identified marker genes, and the immune infiltration analysis indicated considerable discrepancies in neonates diagnosed with sepsis [50]. Lastly, Zhao et al. examined the expression patterns of particular miRNAs and assessed their diagnostic utility for the early identification and management of sepsis by GO enrichment and PPI studies [51]. The three miRNA panels (miR-15a-5p, miR-223-3p, and miR-16-5p) may provide a unique non-invasive biological marker for EOS screening, according to the study’s overall findings [51].

3.2.5. Applications of Bioinformatics in Neonatal Neurology

Recent advances in neonatal care have changed the management and prognosis of neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE); therefore, interest has been focused on detecting prognostic patterns for suffering neonates (Table 7). Since 2006, Chu et al. investigated the metabolomic patterns of newborn urine samples with clinical indications of severe hypoxia at birth, using bioinformatic techniques, including hierarchical clustering analysis [52]. The authors found that inhibited biochemical networks involved in macromolecular production were associated with HIE, as elevated levels of eight urine organic acids in different biochemical pathways were found to be highly sensitive and specific indicators of the prognosis of neurodevelopmental impairment [52]. Moreover, Zhu et al. identified potential biomarkers of neonatal HIE, via the isobaric tags for absolute and relative quantification (iTRAQ) method, and bioinformatics investigations, such as GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis [53]. The authors found 51 frequently differently expressed proteins in neonates with HIE compared to controls [53], indicating haptoglobin and S100A8 as potential biomarkers for neonatal HIE, also reflecting the severity of the disease [53]. Furthermore, to investigate the processes of injury and recovery in neonatal encephalopathy, Friedes et al. used liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) to undertake a targeted metabolomic study [54]. The two-year neurodevelopmental outcomes, as assessed by the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development III, were compared to metabolite levels. The authors proposed that plasma metabolites could improve existing clinical predictors and aid in the prediction of neurological outcomes in infant brain damage using KEGG pathways [54].

Table 7.

Original studies in neonatal neurology.

Furthermore, several studies have been focused on evaluating the diagnostic performance of the newborn screening program (NBS) on inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs). Tangeraas et al. evaluated the performance of the Norwegian expanded NBS, including a total of 21 IEMs, and they found that the incidence of IEMs increased by 46%, mostly as a result of the discovery of attenuated phenotypes, after the expanded NBS was implemented [3]. Also, Hagemeijer et al. focused on the improvement of the detection of lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs), utilizing ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography/high-resolution accurate mass (UHPLC/HRAM) mass spectrometry screening technology, combined with an open-source iterative bioinformatics process [55]. The authors demonstrated that several LSDs were associated with abnormal urine oligosaccharide excretions, which could be potential urine biomarkers for the latter diseases [55]. Moreover, Sabi et al. examined through the NBS program, additional biomarkers for distinguishing falsely suspected glutaric aciduria type-1, by utilizing liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS), and they revealed several up- and down-regulated metabolites in transient disease [56]. Thus, the findings of the study suggested that a unique metabolic pattern associated with the transient rise in metabolites improves the prediction of falsely positive cases, potentially reducing the need for needless medical interventions [56].

Finally, Chung et al., in 2024, examined four prediction models for cognitive or motor function at 24 months of corrected age, using hospitalized and follow-up data of very preterm neonates that were analyzed using an evolutionary-derived machine learning technique, called EL-NDI, and compared to each other using random forest, SVM, and LASSO regression [57]. The EL-NDI model, using ten variables for cognitive delay and four variables for motor delay, respectively, achieved comparable predictive performance to other models using 29 or more variables [57].

Of note, several case-report studies have been published reporting bioinformatic applications for detecting specific IEMs (Table 8). Maryami et al. reported the use of whole-exome sequencing (WES) analysis in combination with different approaches of bioinformatics analysis for detecting metabolic crises on the background of IEMs in the early neonatal period [58,59,60]. Similarly, Forte et al. [61] and Wei et al. [62] reported the use of WES analysis, Sanger analysis, and bioinformatic application for the detection of the pathogenic variants of the galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase gene and the polycystic kidney disease-1 gene, respectively.

Table 8.

Case-report studies in neonatal neurology.

3.2.6. Miscellaneous Applications of Bioinformatics in Neonatal Medicine

A study by Lu et al. in 2006 investigated PAX3 SNPs that may be linked to syndromic neural tube abnormalities (Table 9). The results showed that certain variants of the PAX3 gene were linked to a higher incidence of spina bifida among Hispanic White neonates. [63]. Furthermore, Pan et al. investigated the expression of new noncoding RNAs, called circRNAs, between neonates with hypoxia-induced acute kidney injury and controls, using high-throughput sequencing [64]. The authors demonstrated that 112 circRNAs were considerably downregulated in the acute kidney injury group, while 184 were noticeably elevated and, thus, the findings could contribute to future research on neonatal acute kidney injury and facilitate the detection of novel therapeutic targets [64]. In a different aspect, Shipton et al. investigated the practicability of collecting and analyzing tear proteins from preterm infants at risk of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), which might be implicated in the pathophysiology and prognosis of ROP, using MS for proteomic analysis [65]. The findings of the study suggested that an increase in the lactate dehydrogenase B chain in tears was associated with an increased risk of ROP [65]. Nonetheless, Marom et al. aimed to assess the rapid trio genome sequencing clinical value, diagnostic effectiveness, and viability in all of Israel’s neonatal intensive care units, via sequencing analysis and questionnaires to evaluate clinical utility [66]. The authors revealed a 50% diagnostic effectiveness for disease-causing variations, 11% for variants of unknown significance suspected of being the cause, and 1% for one unique gene candidate [66]. Finally, by analyzing whole-genome sequencing and clinical data using genotype-first and phenotype-first approaches, Pavey et al. assessed the potential of genomic sequencing to supplement the current newborn screening for immunodeficiency. Their findings suggested that neonatal genomic sequencing could potentially supplement newborn screening for immunodeficiency [67].

Table 9.

Original studies of miscellaneous applications of bioinformatics in neonatal medicine.

Finally, in case-report studies (Table 10), in two newborns with congenital central hypothyroidism with anemia resistant to conventional treatment, Baquedano et al. revealed the molecular effects of a unique missense mutation and a novel splice-junction mutation in the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)-beta subunit gene [68]. Moreover, Zheng et al. explored the utility of WES to establish the diagnosis of congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II, revealing that the analysis by multiple bioinformatics tools predicted that the mutant proteins were deleterious [69]. Besides, Khabou et al., in 2024, reported that they managed to establish the diagnosis of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis in six unrelated Tunisian infants, via panel-target sequencing, followed by an exhaustive bioinformatics and modeling investigations [70].

Table 10.

Case-report studies of miscellaneous applications of bioinformatics in neonatal medicine.

4. Challenges and Ethical Issues of Bioinformatics

Bioinformatics has aided in establishing networks that facilitate the retrieval of biological data, providing new insight into many complex neonatal diseases. The comprehensive interpretation of gene variation and molecular pathways that are involved in the pathogenesis of several neonatal diseases, such as RDS, BPD, CHD, NEC, HIE, and IEMs, could provide several promising therapeutic options. However, though the amount of information being generated increases daily, it is challenging to establish the optimum time and ways to incorporate it. Neonatal diseases are complex and multifactorial and thus, the concept that “one SNP causes one phenotype” is unsatisfactory. Further research is warranted to explore the complex gene–gene and gene–environment interactions [71]. Furthermore, although GWAS has been widely used to establish the relationship between SNPs and diseases, the biological link between genetic variations and phenotypic features is rarely disclosed [72]. Therefore, a systems biology-based strategy combining data from several biological levels, including the genome, transcriptome, and proteome, may be beneficial in understanding these links [73].

Nonetheless, bioinformatics research incorporated with artificial intelligence algorithms must adhere to ethical and impartial standards [74]. Confidentiality and privacy of sensitive patient data must be protected [75], whereas potential medico-legal risks and issues with insurability if unfavorable long-term results are anticipated should be addressed [76]. Future studies must strike a balance between the increased uncertainty and anxiety that parents and carers may experience as a result of these discoveries and the ethical implications of beneficence.

5. Future Directions

Due to the recent advance in bioinformatics, the study of genetic disorders is shifting beyond the isolation of single genes and toward the discovery of gene networks within cells, the comprehension of intricate gene interactions, and the determination of the function of these networks in neonatal diseases [77]. Clinicians and clinical researchers will benefit from bioinformatics’ guidance and assistance in leveraging computational biology’s benefits [78]. Nonetheless, the clinical research teams who can transition with ease between the laboratory bench, neonatal clinical practice, and the use of these advanced computational tools will benefit the most in the upcoming decades. In addition, the role of artificial intelligence in the modern era has become an important partner in healthcare services. The main advantage of artificial intelligence is that provides clinicians the ability to evaluate large volumes of medical data that are too complex for medical professionals to study quickly enough to find the diagnosis and determine a treatment plan. After proper training, artificial intelligence models can function similarly to human neurons and support decision-making algorithms. Thus, in the following decades, clinicians could benefit from the advantages of using large bioinformatics datasets evaluated with artificial-intelligence-based models.

6. Conclusions

Bioinformatics is becoming popular as a novel instrument for examining the fundamental mechanisms behind neonatal diseases. Several studies have explored the gene expression and molecular pathways in neonatal RDS, BPD, CHDs, gut microbiota, NEC, sepsis, or IEMs. Further studies are, however, warranted to investigate complex gene–gene and gene–environment interactions in light of the variability of many neonatal disease symptoms and the multifactorial nature of their origin.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R. and V.G.; methodology, D.R.; investigation, D.R.; resources, D.R.; data curation, D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.R.; writing—review and editing, M.B., K.K., C.K., and V.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bayat, A. Science, medicine, and the future: Bioinformatics. BMJ 2002, 324, 1018–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundararajan, S.; Doctor, A. Early recognition of neonatal sepsis using a bioinformatic vital sign monitoring tool. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 91, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangeraas, T.; Sæves, I.; Klingenberg, C.; Jørgensen, J.; Kristensen, E.; Gunnarsdottir, G.; Hansen, E.V.; Strand, J.; Lundman, E.; Ferdinandusse, S.; et al. Performance of Expanded Newborn Screening in Norway Supported by Post-Analytical Bioinformatics Tools and Rapid Second-Tier DNA Analyses. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadie, C.T.; Arya, S.; Arora, T.; Pandillapalli, N.R.; Moreira, A. A bioinformatics approach towards bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Transl. Pediatr. 2023, 12, 1213–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benton, D. Bioinformatics—Principles and potential of a new multidisciplinary tool. Trends Biotechnol. 1996, 14, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewitter, F.; Kumuthini, J.; Chimenti, M.; Nahnsen, S.; Peltzer, A.; Meraba, R.; McFadyen, R.; Wells, G.; Taylor, D.; Maienschein-Cline, M.; et al. Ten simple rules for providing effective bioinformatics research support. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007531. [Google Scholar]

- Caudai, C.; Galizia, A.; Geraci, F.; Le Pera, L.; Morea, V.; Salerno, E.; Via, A.; Colombo, T. AI applications in functional genomics. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 5762–5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, A.; Beck, S. Making multi-omics data accessible to researchers. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoka, S.; Ouzounis, C.A. Recent developments and future directions in computational genomics. FEBS Lett. 2000, 480, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, S.K.; Almo, S.C.; Bonanno, J.B.; Capel, M.; Chance, M.R.; Gaasterland, T.; Lin, D.; Šali, A.; Studier, F.W.; Swaminathan, S. Structural genomics: Beyond the Human Genome Project. Nat. Genet. 1999, 23, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Informatics Areas, Translational Bioinformatics. Available online: https://amia.org/about-amia/why-informatics/informatics-research-and-practice (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Palma, J.P.; Benitz, W.E.; Tarczy-Hornoch, P.; Butte, A.J.; Longhurst, C.A. Topics in Neonatal Informatics. NeoReviews 2012, 13, e281–e284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Chanda, B.; Chen, Y.-f.; Wang, X.-j.; You, M.-y.; Zhang, Y.-h.; Cheng, R.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.-q. Microarray and Bioinformatics Analysis of Circular RNA Differential Expression in Newborns With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 728462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadchouel, A.; Durrmeyer, X.; Bouzigon, E.; Incitti, R.; Huusko, J.; Jarreau, P.-H.; Lenclen, R.; Demenais, F.; Franco-Montoya, M.-L.; Layouni, I.; et al. Identification of SPOCK2 As a Susceptibility Gene for Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 184, 1164–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; St Julien, K.R.; Stevenson, D.K.; Hoffmann, T.J.; Witte, J.S.; Lazzeroni, L.C.; Krasnow, M.A.; Quaintance, C.C.; Oehlert, J.W.; Jelliffe-Pawlowski, L.L.; et al. A Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) for Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Pediatrics 2013, 132, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambalavanan, N.; Cotten, C.M.; Page, G.P.; Carlo, W.A.; Murray, J.C.; Bhattacharya, S.; Mariani, T.J.; Cuna, A.C.; Faye-Petersen, O.M.; Kelly, D.; et al. Integrated Genomic Analyses in Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. J. Pediatr. 2015, 166, 531–537.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahlman, M.; Karjalainen, M.K.; Huusko, J.M.; Andersson, S.; Kari, M.A.; Tammela, O.K.T.; Sankilampi, U.; Lehtonen, L.; Marttila, R.H.; Bassler, D.; et al. Genome-wide association study of bronchopulmonary dysplasia: A potential role for variants near the CRP gene. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Chen, B.-L.; Huang, J.-B.; Meng, Y.-N.; Duan, X.-J.; Chen, L.; Li, L.-R.; Chen, Y.-P. Angiogenesis-related genes may be a more important factor than matrix metalloproteinases in bronchopulmonary dysplasia development. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 18670–18679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torgerson, D.G.; Ballard, P.L.; Keller, R.L.; Oh, S.S.; Huntsman, S.; Hu, D.; Eng, C.; Burchard, E.G.; Ballard, R.A. Ancestry and genetic associations with bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2018, 315, L858–L869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, Q.; Yin, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L. CircRNA, lncRNA, and mRNA profiles of umbilical cord blood exosomes from preterm newborns showing bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 3345–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, P.; Di Resta, C.; Volonteri, C.; Castiglioni, E.; Bonfiglio, S.; Lazarevic, D.; Cittaro, D.; Stupka, E.; Ferrari, M.; Somaschini, M.; et al. Exome sequencing and pathway analysis for identification of genetic variability relevant for bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in preterm newborns: A pilot study. Clin. Chim. Acta 2015, 451, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cho, H.-Y.; Campbell, M.R.; Panduri, V.; Coviello, S.; Caballero, M.T.; Sambandan, D.; Kleeberger, S.R.; Polack, F.P.; Ofman, G.; et al. Epigenome-wide association study of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants: Results from the discovery-BPD program. Clin. Epigenetics 2022, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magagnotti, C.; Matassa, P.G.; Bachi, A.; Vendettuoli, V.; Fermo, I.; Colnaghi, M.R.; Carletti, R.M.; Mercadante, D.; Fattore, E.; Mosca, F.; et al. Calcium signaling-related proteins are associated with broncho-pulmonary dysplasia progression. J. Proteom. 2013, 94, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Odumade, O.A.; van Zalm, P.; Smolen, K.K.; Fujimura, K.; Muntel, J.; Rotunno, M.S.; Winston, A.B.; Steen, J.A.; Parad, R.B.; et al. Urine Proteomics for Noninvasive Monitoring of Biomarkers in Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Neonatology 2022, 119, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, S.; Zollo, I.; Villella, V.R.; Scialò, F.; Giordano, S.; Esposito, M.V.; Salemme, N.; Di Domenico, C.; Cernera, G.; Zarrilli, F.; et al. Identification of an ultra-rare Alu insertion in the CFTR gene: Pitfalls and challenges in genetic test interpretation. Clin. Chim. Acta 2024, 558, 118317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahado-Singh, R.O.; Zaffra, R.; Albayarak, S.; Chelliah, A.; Bolinjkar, R.; Turkoglu, O.; Radhakrishna, U. Epigenetic markers for newborn congenital heart defect (CHD). J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015, 29, 1881–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahado-Singh, R.O.; Vishweswaraiah, S.; Aydas, B.; Yilmaz, A.; Saiyed, N.M.; Mishra, N.K.; Guda, C.; Radhakrishna, U. Precision cardiovascular medicine: Artificial intelligence and epigenetics for the pathogenesis and prediction of coarctation in neonates. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 35, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhakrishna, U.; Vishweswaraiah, S.; Veerappa, A.M.; Zafra, R.; Albayrak, S.; Sitharam, P.H.; Saiyed, N.M.; Mishra, N.K.; Guda, C.; Bahado-Singh, R. Newborn blood DNA epigenetic variations and signaling pathway genes associated with Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashkin, S.R.; Cleves, M.; Shaw, G.M.; Nembhard, W.N.; Nestoridi, E.; Jenkins, M.M.; Romitti, P.A.; Lou, X.Y.; Browne, M.L.; Mitchell, L.E.; et al. A genome-wide association study of obstructive heart defects among participants in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2022, 188, 2303–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouat, J.S.; Li, S.; Myint, S.S.; Laufer, B.I.; Lupo, P.J.; Schraw, J.M.; Woodhouse, J.P.; de Smith, A.J.; LaSalle, J.M. Epigenomic signature of major congenital heart defects in newborns with Down syndrome. Hum. Genom. 2023, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Lyu, C.; Liu, N.; Nembhard, W.N.; Witte, J.S.; Hobbs, C.A.; Li, M. A gene-based association test of interactions for maternal–fetal genotypes identifies genes associated with nonsyndromic congenital heart defects. Genet. Epidemiol. 2023, 47, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiao, F.; Qian, Y.; Wu, B.; Dong, X.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, G.; Wang, L.; Yan, K.; Yang, L.; et al. Genetic architecture in neonatal intensive care unit patients with congenital heart defects: A retrospective study from the China Neonatal Genomes Project. J. Med. Genet. 2023, 60, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.-j.; Wang, C.-m.; Wang, Y.-t.; Qiao, H.; Fang, L.-q.; Wang, Z.-b. Lactation-Related MicroRNA Expression in Microvesicles of Human Umbilical Cord Blood. Med. Sci. Monit. 2016, 22, 4542–4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parnanen, K.M.M.; Hultman, J.; Markkanen, M.; Satokari, R.; Rautava, S.; Lamendella, R.; Wright, J.; McLimans, C.J.; Kelleher, S.L.; Virta, M.P. Early-life formula feeding is associated with infant gut microbiota alterations and an increased antibiotic resistance load. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Xiang, M.; Cai, X.; Wu, B.; Chen, C.; Cai, N.; Ao, D. Multi-omics analyses of gut microbiota via 16S rRNA gene sequencing, LC-MS/MS and diffusion tension imaging reveal aberrant microbiota-gut-brain axis in very low or extremely low birth weight infants with white matter injury. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letourneau, J.; Walker, L.; Han, S.H.; David, L.A.; Younge, N. A pilot study of fecal pH and redox as functional markers in the premature infant gut microbiome. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0290598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, L. Bioinformatics analysis of potential key genes and pathways in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Chen, X.; Qian, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, X.; Yu, B.; Yao, S.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, J.; et al. Lipidomic Profiling of Human Milk Derived Exosomes and Their Emerging Roles in the Prevention of Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, 2000845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, L.; Wu, M.; Huang, J.; Huang, T. Identification of Inflammatory Genes, Pathways, and Immune Cells in Necrotizing Enterocolitis of Preterm Infant by Bioinformatics Approaches. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 5568724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, É.; Ferretti, E.; Babakissa, C.; Burghardt, K.M.; Levy, E.; Beaulieu, J.-F. IL-17-related signature genes linked to human necrotizing enterocolitis. BMC Res. Notes 2021, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Xu, Y.; Gao, N.; Li, A. Weighted Gene Coexpression Network Analysis Reveals the Critical lncRNAs and mRNAs in Development of Hirschsprung’s Disease. J. Comput. Biol. 2020, 27, 1115–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhao, F.; Ma, T.; Xiao, Y.; Peng, K.; Xia, R. ZEB2 alleviates Hirschsprung’s-associated enterocolitis by promoting the proliferation and differentiation of enteric neural precursor cells via the Notch-1/Jagged-2 pathway. Gene 2024, 912, 148365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustarim, M.; Yanwirasti, Y.; Jamsari, J.; Rukmono, R.; Nindrea, R.D. Association of Gene Polymorphism of Bactericidal Permeability Increasing Protein Rs4358188, Cluster of Differentiation 14 Rs2569190, Interleukin 1β Rs1143643 and Matrix Metalloproteinase-16 Rs2664349 with Neonatal Sepsis. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 2728–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, L.; Wang, Z.-w.; Hu, S.-q.; Zhao, W.-j.; Geng, X.-j.; Zhou, T.; Zhuo, L.; Chen, X.-b.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.-l.; et al. Identification of Key mRNAs and lncRNAs in Neonatal Sepsis by Gene Expression Profiling. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2020, 2020, 8741739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, P.; Garzón, M.J.; Lorente-Pozo, S.; Mena-Mollá, S.; Vento, M.; Pallardó, F.V.; Beltrán-García, J.; Osca-Verdegal, R.; García-López, E.; García-Giménez, J.L. Use of Two Complementary Bioinformatic Approaches to Identify Differentially Methylated Regions in Neonatal Sepsis. Open Bioinform. J. 2021, 14, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Zhou, T. Identification of key biomarkers in neonatal sepsis by integrated bioinformatics analysis and clinical validation. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciesielski, T.H.; Zhang, X.; Tacconelli, A.; Lutsar, I.; de Cabre, V.M.; Roilides, E.; Ciccacci, C.; Borgiani, P.; Scott, W.K.; Aboulker, J.P.; et al. Late-onset neonatal sepsis: Genetic differences by sex and involvement of the NOTCH pathway. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 93, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Yu, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, Y. Intestinal metabolomics in premature infants with late-onset sepsis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Ariyakumar, G.; Gupta, N.; Kamdar, S.; Barugahare, A.; Deveson-Lucas, D.; Gee, S.; Costeloe, K.; Davey, M.S.; Fleming, P.; et al. Identifying immune signatures of sepsis to increase diagnostic accuracy in very preterm babies. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hang, Y.; Qu, H.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Ma, S.; Tang, C.; Wu, C.; Bao, Y.; Jiang, F.; Shu, J. Exploration of programmed cell death-associated characteristics and immune infiltration in neonatal sepsis: New insights from bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lu, C.; Zhu, R.; Hu, X. Study on identification of a three-microRNA panel in serum for diagnosing neonatal early onset sepsis. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023, 36, 2280527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.Y.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, X.G.; Lau, T.K.; Rogers, M.S.; Fok, T.F.; Law, L.K.; Pang, C.P.; Wang, C.C. Metabolomic and bioinformatic analyses in asphyxiated neonates. Clin. Biochem. 2006, 39, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yun, Y.; Jin, M.; Li, G.; Li, H.; Miao, P.; Ding, X.; Feng, X.; Xu, L.; Sun, B. Identification of novel biomarkers for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy using iTRAQ. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2020, 46, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedes, B.D.; Molloy, E.; Strickland, T.; Zhu, J.; Slevin, M.; Donoghue, V.; Sweetman, D.; Kelly, L.; O’Dea, M.; Roux, A.; et al. Neonatal encephalopathy plasma metabolites are associated with neurodevelopmental outcomes. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 92, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagemeijer, M.C.; van den Bosch, J.C.; Bongaerts, M.; Jacobs, E.H.; van den Hout, J.M.P.; Oussoren, E.; Ruijter, G.J.G. Analysis of urinary oligosaccharide excretion patterns by UHPLC/HRAM mass spectrometry for screening of lysosomal storage disorders. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2023, 46, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabi, E.M.; AlMogren, M.; Sebaa, R.; Sumaily, K.M.; AlMalki, R.; Mujamammi, A.H.; Abdel Rahman, A.M. Comprehensive metabolomics analysis reveals novel biomarkers and pathways in falsely suspected glutaric aciduria Type-1 newborns. Clin. Chim. Acta 2024, 557, 117861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.W.; Chen, J.-C.; Chen, H.-L.; Ko, F.-Y.; Ho, S.-Y.; Chang, J.-H.; Tsou, K.-I.; Tsao, P.-N.; Mu, S.-C.; Hsu, C.-H.; et al. Developing a practical neurodevelopmental prediction model for targeting high-risk very preterm infants during visit after NICU: A retrospective national longitudinal cohort study. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryami, F.; Davoudi-Dehaghani, E.; Khalesi, N.; Rismani, E.; Rahimi, H.; Talebi, S.; Zeinali, S. Identification and characterization of the largest deletion in the PCCA gene causing severe acute early-onset form of propionic acidemia. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2023, 298, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maryami, F.; Rismani, E.; Davoudi-Dehaghani, E.; Khalesi, N.; Motlagh, F.Z.; Kordafshari, A.; Talebi, S.; Rahimi, H.; Zeinali, S. Identifying and predicting the pathogenic effects of a novel variant inducing severe early onset MMA: A bioinformatics approach. Hereditas 2023, 160, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maryami, F.; Rismani, E.; Davoudi-Dehaghani, E.; Khalesi, N.; Talebi, S.; Mahdian, R.; Zeinali, S. In silico Analysis of Two Novel Variants in the Pyruvate Carboxylase (PC) Gene Associated with the Severe Form of PC Deficiency. Iran. Biomed. J. 2023, 27, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, G.; Buonadonna, A.L.; Pantaleo, A.; Fasano, C.; Capodiferro, D.; Grossi, V.; Sanese, P.; Cariola, F.; De Marco, K.; Lepore Signorile, M.; et al. Classic Galactosemia: Clinical and Computational Characterization of a Novel GALT Missense Variant (p.A303D) and a Literature Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Zhang, B.; Tang, W.; Li, X.; Shuai, Z.; Tang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, L.; Liu, Q. A de novo PKD1 mutation in a Chinese family with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Medicine 2024, 103, e27853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Zhu, H.; Wen, S.; Laurent, C.; Shaw, G.M.; Lammer, E.J.; Finnell, R.H. Screening for novel PAX3 polymorphisms and risks of spina bifida. Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2006, 79, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.Q.; Shi, J.; Wang, M.Z.; Tong, M.L.; Zhou, X.G. RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis of circular RNAs in asphyxial newborns with acute kidney injury. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2023, 39, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shipton, C.; Aitken, J.; Atkinson, S.; Burchmore, R.; Hamilton, R.; Mactier, H.; McGill, S.; Millar, E.; Houtman, A.C. Tear Proteomics in Infants at Risk of Retinopathy of Prematurity: A Feasibility Study. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marom, D.; Mory, A.; Reytan-Miron, S.; Amir, Y.; Kurolap, A.; Cohen, J.G.; Morhi, Y.; Smolkin, T.; Cohen, L.; Zangen, S.; et al. National Rapid Genome Sequencing in Neonatal Intensive Care. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e240146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavey, A.R.; Bodian, D.L.; Vilboux, T.; Khromykh, A.; Hauser, N.S.; Huddleston, K.; Klein, E.; Black, A.; Kane, M.S.; Iyer, R.K.; et al. Utilization of genomic sequencing for population screening of immunodeficiencies in the newborn. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baquedano, M.S.; Ciaccio, M.; Dujovne, N.; Herzovich, V.; Longueira, Y.; Warman, D.M.; Rivarola, M.A.; Belgorosky, A. Two Novel Mutations of the TSH-β Subunit Gene Underlying Congenital Central Hypothyroidism Undetectable in Neonatal TSH Screening. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, E98–E103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Gao, L.; Liu, H.; Xiao, P.; Lu, J.; Li, J.; Wu, S.; Cheng, S.; Bian, X.; Du, Z.; et al. Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II in a newborn with a novel compound heterozygous mutation in the SEC23B: A case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Hematol. 2023, 119, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khabou, B.; Kallabi, F.; Abdelaziz, R.B.; Maaloul, I.; Aloulou, H.; Chehida Ab Kammoun, T.; Barbu, V.; Boudawara, T.S.; Fakhfakh, F.; Khemakhem, B.; et al. Molecular and computational characterization of ABCB11 and ABCG5 variants in Tunisian patients with neonatal/infantile low-GGT intrahepatic cholestasis: Genetic diagnosis and genotype–phenotype correlation assessment. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2023, 88, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernald, G.H.; Capriotti, E.; Daneshjou, R.; Karczewski, K.J.; Altman, R.B. Bioinformatics challenges for personalized medicine. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1741–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, K.A.; Murray, S.S.; Schork, N.J.; Topol, E.J. Human genetic variation and its contribution to complex traits. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohl, P.; Crampin, E.J.; Quinn, T.A.; Noble, D. Systems Biology: An Approach. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 88, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, X.; Singh, S.; Marmor, R.; Bonomi, L.; Fox, D.; Dow, M.; Ohno-Machado, L. Genome privacy: Challenges, technical approaches to mitigate risk, and ethical considerations in the United States. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2016, 1387, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, A.; Grassi, S.; Vetrugno, G.; Rossi, R.; Della Morte, G.; Pinchi, V.; Caputo, M. Management of Medico-Legal Risks in Digital Health Era: A Scoping Review. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 821756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, A.; Ormond, K.E. Ethical considerations in prenatal testing: Genomic testing and medical uncertainty. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debouck, C.; Metcalf, B. The Impact of Genomics on Drug Discovery. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2000, 40, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D. Are you ready for the revolution? Nature 2001, 409, 758–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).