1. Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) imposes unusually tight mathematical and systems constraints. Dynamics must be physically plausible. Spatial estimation must be accurate. Rendering must be photometrically consistent. Interaction must be responsive. All of these must run within millisecond budgets at 90–120 Hz to sustain presence and avoid cybersickness. Even small latency spikes or implausible physics can break immersion. VR is therefore a stringent testbed for methods spanning differential equations, optimization on manifolds, real-time rendering, and human–computer interaction.

Classical foundations remain indispensable. Rigid-body dynamics and constraint methods [

1,

2] govern motion and contact; illumination and projection models [

3,

4,

5] determine image formation; quaternions and inverse kinematics (IK) on Special Euclidean Group (3D) (

) [

6,

7,

8,

9] enable natural manipulation and embodiment. Recent advances augment rather than replace these tools: NeRFs [

10] and real-time variants [

11,

12] learn geometry and appearance for high-quality view synthesis; differentiable rendering [

13] exposes image-level gradients for joint calibration; Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) [

14] embed physical laws in learning.

1.1. Scope, Perspective, and Positioning

We focus on mathematical models that enable real-time VR on consumer hardware (90–120 Hz). The survey is system-oriented. It is organized around four pillars:

- (i)

Physics-based simulation: integration, constraints, collision, learned surrogates.

- (ii)

Spatial representation and geometric transforms: quaternions, Lie groups, differentiable transforms, manifold optimization.

- (iii)

Real-time rendering: Phong/Bidirectional Reflectance Distribution Function (BRDF), GPU pipelines, neural/differentiable rendering, perceptual strategies.

- (iv)

Interaction modeling: sensing/pose, IK, hand/body tracking, constraint-based manipulation, haptics, comfort-aware control.

Authoritative surveys exist for 3D user interfaces [

15], classical rendering/geometry [

4,

5], inverse kinematics [

9], and rigid-body physics [

2]. Recent surveys address neural, differentiable, and foveated rendering [

10,

11,

12,

13,

16,

17], but typically treat these topics in isolation or outside a VR systems perspective. Our positioning reads physics, tracking/Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM), rendering, and interaction together, framed by VR-specific constraints (quality–latency–memory trade-offs, motion-to-photon, reprojection error, SSQ) and by cross-module interfaces (e.g.,

tracking feeding differentiable rendering and avatar controllers).

1.2. Contributions and Methodology

This article is a survey; contributions are curatorial and integrative:

- (i)

We organize stability-oriented practices for VR physics. We clarify when semi-implicit/symplectic integrators are preferable. We explain how constraint projection maintains plausibility under contact. We identify where perceptually gated adaptivity can safely reduce cost. We also situate differentiable simulators within this toolbox.

- (ii)

We connect literatures on manifold optimization, SLAM, differentiable image formation, and neural scene fields. We present an end-to-end view for tracking, calibration, and reconstruction. We include a taxonomy and typical failure modes for avatars and hand–object interaction.

- (iii)

We review hybrid and neural rendering for dual-eye 90/120 Hz VR. We distill rules of thumb for the quality–latency–memory trade-off (e.g., radiance caching, network factorization, perceptual scheduling).

- (iv)

We align methods in physics, rendering, and interaction (IK, haptics, personalized avatars) with user-facing and system metrics. We link algorithm families to time-to-grasp, slip rate, embodiment, Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE)/Relative Pose Error (RPE), reprojection error, and motion-to-photon latency.

- (v)

We compile checklists and a consolidated benchmark table (

Appendix A). We outline a near-term (1–2 year) agenda with concrete goals. Targets include numerical energy drift

on standard scenes. We seek average reprojection error

px. We target end-to-end motion-to-photon

ms. We aim for 20–

lower SSQ under standardized protocols. To ground the discussion in practical device constraints,

Appendix A.1 reports a headset specification summary (

Table A1).

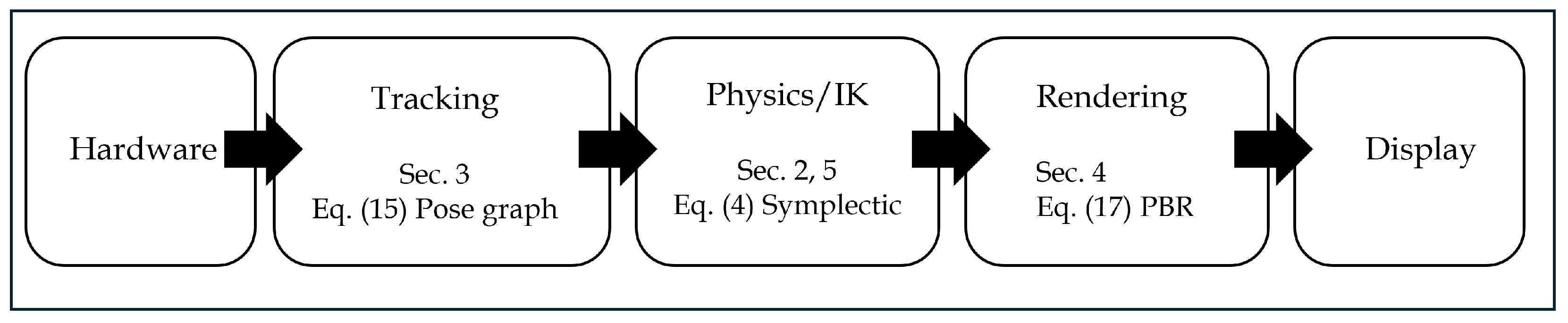

To provide a high-level roadmap,

Figure 1 summarizes the simplified VR system pipeline considered in this survey (hardware → tracking → physics/IK → rendering → display) and maps each block to the corresponding sections and representative equations. In particular, we later illustrate the numerical stability of the physics update in

Figure 2 and detail the rendering pipeline in

Figure 3.

Selection criteria. We surveyed 2020–2025 work in SIGGRAPH, TOG, Eurographics, IEEE VR, TVCG, Virtual Reality, CHI, CVPR, ICCV, ECCV, NeurIPS, and ICRA, prioritizing: (i) real-time constraints (≥90 Hz or ≤20 ms), (ii) explicit mathematical formulations, (iii) quantitative validation, and (iv) integration/deployment considerations. Foundational references are included where they clarify principles or baselines.

1.3. Reader’s Guide and Conventions

Reader’s guide.

Section 2 covers numerical integration, constraint satisfaction, collision detection/response, and stability–performance trade-offs.

Section 3 treats coordinate frames, rotation representations, differentiable transforms, manifold optimization, and pose-graph estimation.

Section 4 spans classical to neural/differentiable rendering and perceptual strategies.

Section 5 reviews sensing, IK, haptics, and comfort-aware control.

Section 6 sets near-term targets;

Section 7 synthesizes implications.

Notation and conventions. Bold letters denote vectors/matrices; / denote rotations/rigid motions; unit quaternions represent orientation. We use standard reprojection/trajectory metrics (ATE/RPE), SSQ for comfort, and per-eye throughput (resolution × refresh) for system reporting.

2. Physics-Based Simulation in VR

VR immersion depends not only on visual fidelity but also on physically consistent responses under tight frame budgets. This section formalizes equations of motion and constraints, compares time integration schemes under accuracy-stability-structure trade-offs, summarizes contact/friction as non-smooth dynamics, and details perceptual/system-aware adaptivity and learning-augmented simulators relevant to real-time deployment.

Table 1 provides an at-a-glance summary of modeling priorities across representative VR application domains. The ratings indicate relative emphasis (1–5) in terms of typical system requirements rather than a universal ranking. These priorities guide the focus of the subsequent sections on tracking, physics/IK, and rendering, where we detail the corresponding mathematical formulations.

2.1. VR Strengths and Limitations (at a Glance)

Strengths

- –

Perceptual realism: physically consistent responses increase presence and make user action outcomes predictable.

- –

Interaction stability: constraint-aware solvers reduce jitter/failure during grasp/manipulation [

2].

- –

Composability: shared rigid/soft formulations unify haptics, avatars, and environment logic.

Limitations

- –

Strict frame budgets: solver work must fit

ms @ 90 Hz (8.3 ms @ 120 Hz); physics LOD/scheduling are mandatory [

18,

19].

- –

Stability–accuracy trade-off: Semi-implicit/projection schemes preserve stability but bias trajectories. Higher-order non-symplectic methods are costlier [

2,

20].

- –

Contact/constraint overhead: non-smooth friction/contact induces LCP/SOCP solves; under-resolved contacts cause visible interpenetration/haptic artifacts [

21,

22].

- –

Latency coupling: physics–tracking–render clocks interact; motion-to-photon and prediction errors degrade comfort [

5].

2.2. Equations of Motion and Constraints

This subsection states the equations of motion for a rigid multibody system and how equality/inequality constraints enter the model. We fix notation for the state , separate model terms , and introduce Lagrange multipliers for constraints; these definitions will be used throughout the section.

Classical physically based modeling formulations established the rigid-body dynamics and constraint foundations that still underpin real-time physics engines used in modern VR [

23].

Let generalized coordinates

and velocities

. In the absence of constraints, the equations of motion read

with mass matrix

M, Coriolis/gyroscopic term

C, and external forces

.

Intuitively, Equation (

1) is the

n-DOF generalization of Newton’s law:

maps accelerations to forces, while

gathers velocity-dependent inertial effects that become prominent in coupled or fast motions.

Holonomic constraints

(e.g., joints) and unilateral nonpenetration

(contacts) impose algebraic conditions. Introducing Lagrange multipliers

for the constraints yields the constrained system

where

J is the constraint Jacobian. Constraint drift can be reduced by Baumgarte stabilization (enforcing

in the integrator) or by post-stabilization, i.e., projecting

back to the constraint manifold after each step [

1,

2].

A common post-stabilization step applies a minimal correction that projects the tentative configuration

back onto the constraint manifold:

where

.

2.3. Time Integration: Accuracy, Stability, and Structure

This subsection contrasts commonly used time-stepping schemes for interactive VR physics and graphics. We focus on how order of accuracy, stability, and structure preservation trade off under real-time budgets. Let be the fixed timestep and let denote the instantaneous acceleration implied by forces and constraints.

Explicit Euler. The explicit Euler integration is formulated as follows:

It is first-order accurate and cheap, but it tends to drift in energy over long horizons.

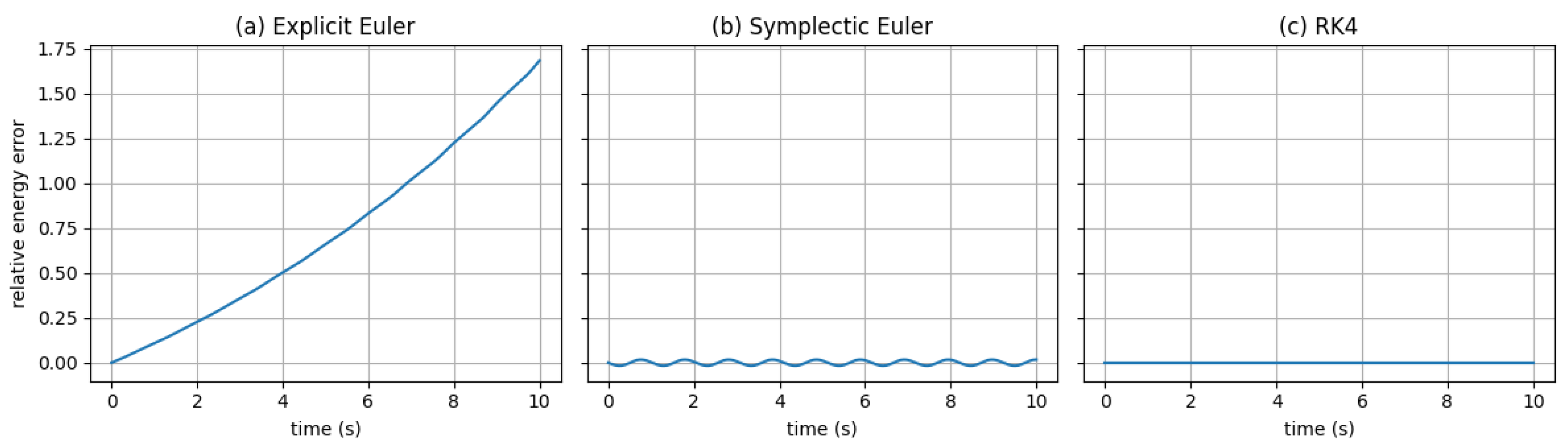

Symplectic (semi-implicit) Euler. The symplectic Euler integration is formulated as:

This scheme preserves a discrete symplectic structure and often exhibits bounded long-horizon energy error for Hamiltonian systems. To illustrate the long-horizon stability of Equation (

4),

Figure 2 compares the relative energy error of a simple pendulum using explicit Euler, symplectic (semi-implicit) Euler (Equation (

4)), and RK4 under the same step size

.

Position Verlet. This simple equation gives the position Verlet method:

It is second-order accurate and symplectic for conservative forces and is widely used for cloth and soft-constraint models.

High-order non-symplectic (RK4). Classical RK4 is fourth-order accurate per step but non-symplectic and costlier; it suits small, nonstiff subsystems (e.g., camera oscillators) when local accuracy outweighs structure preservation [

20].

In practice, semi-implicit updates are often coupled with constraint projection methods such as position-based dynamics (PBD) and extended position-based dynamics (XPBD) to maintain stability under contact bursts [

2,

24,

25].

2.4. Contact, Friction, and Non-Smooth Dynamics

This subsection summarizes the discrete-time treatment of rigid contact and Coulomb friction used in real-time VR simulators. We adopt an impulse and velocity level view, which handles intermittent contact, sticking and sliding, and naturally leads to complementarity or cone projection problems.

Normal contact. Let

denote the end-of-step normal gap (non-penetration requires

) and let

be the normal impulse delivered over the step. Normal contact is enforced by the complementarity condition

meaning either a positive gap with zero impulse, or zero gap with a compressive impulse [

1,

21].

Tangential friction. With coefficient

, the Coulomb cone is

with sticking if the post-impact tangential velocity

lies strictly inside the cone, and sliding on the boundary with

opposite the friction direction (maximum dissipation).

Discrete formulations and solvers. Approximating the circular cone by a friction pyramid yields a linear complementarity problem (LCP); keeping the cone gives a second-order cone program (SOCP). Common real-time solvers include projected Gauss–Seidel and cone projection (PGS/CP), proximal or alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM) variants, and interior-point methods

Proximity queries. Accurate contact generation requires robust distance queries and feature pairs. For rigid models, Gilbert–Johnson–Keerthi (GJK) algorithm with Expanding Polytope Algorithm (EPA) refinement and bounding volume hierarchies (BVHs) are standard; for deformables, signed distance fields or volumetric proxies are widely used [

26,

27,

28].

2.5. Perceptual- and System-Aware Adaptivity

This subsection formalizes adaptivity for real-time VR as four ingredients: error-controlled timestepping, contact-aware substepping, gaze-driven physics LOD, and frame-budget scheduling. The goal is to meet a per-frame budget of

B (e.g.,

ms at 90 Hz) without perceptible artifacts [

2,

18,

19,

22].

- (i)

Error-controlled timestepping.

Let the integrator have local order

p, and let

be an estimate of the local truncation error at step

k (from an embedded pair or a residual). For a user or device tolerance

,

with

to prevent step rejection cascades. This keeps integration error below a perceptual threshold while exploiting slack when motion is slow.

- (ii)

Contact-aware substepping.

For a candidate contact with normal gap

and closing speed

, choose the number of substeps

m inside the frame step

so that predicted closure per substep is a fraction

of the gap:

with small

to avoid division by zero. This reduces penetrations without globally shrinking

during brief contact bursts.

- (iii)

Gaze-driven physics LOD.

Let

be the rendering projection and

evaluated at object

i. To bound screen-space motion by an eccentricity-dependent tolerance

(from eye-tracking),

which yields a per-object update interval

Equivalently, define a perceptual weight

(e.g.,

) and set per-object iteration counts

or update rates

that decrease with eccentricity [

19].

- (iv)

Frame-budget scheduling.

Let be tasks in the current frame (constraint batches, cloth solver iterations, background rigid updates, etc.). Each task has cost and perceptual utility (higher near fovea, for large screen-space motion, or for audible haptic coupling).

We allocate work by

a knapsack-style problem. A greedy policy using ratio

is effective in real time; engine backends (e.g., DOTS, Chaos, Flex) realize this by prioritizing foreground constraints and deferring low-

tasks to worker queues [

2].

Clock Alignment

Let

. We reduce perceived latency by predicting the presented state to the next vsync time

:

and by choosing

via (

9) so that jitter in

does not spill over

B.

2.6. Learning- and Gradient-Based Simulation

Differentiable physics layers embed simulation inside gradient-based pipelines for system identification, control, and inverse problems; Recent differentiable solvers that explicitly handle contact (and, when available, frictional effects) improve gradient quality for learning-based control and inverse problems [

29]. Such advances make physically grounded optimization more practical within real-time VR pipelines.

Moreover, contact is often regularized (compliance/soft constraints) to ensure stable gradients [

30,

31]. Physics-Informed Neural Networks incorporate PDE residuals into the loss,

serving as surrogates for expensive substeps (e.g., local solves in reduced FEM) or for environment response fields in digital twins [

14,

32,

33]. These hybrids can reduce substep counts while meeting comfort constraints when validated against baselines.

Deployment in real-time VR must additionally account for tail latency and out-of-distribution failures; practical guardrails and fallback strategies are discussed in

Section 6.8.

2.7. Practical Guidance and Trade-Offs

Based on

Table 2 and the preceding discussion, several practical guidelines emerge for real-time VR: structure-preserving (symplectic) schemes are generally preferable for long-horizon stability; adaptive substepping near impacts mitigates penetrations without shrinking the global step; per-frame constraint projection helps maintain feasibility under contacts; and perceptual gating reduces workload by lowering update rates for off-gaze or low-saliency bodies [

18,

19].

To ground the above dual-rate scheduling principles in a concrete VR medical scenario, we summarize a representative deployment in

Box 1 (see

Appendix A.2 for full details).

Box 1. Illustrative Deployment: Medical VR Surgical Simulator

Context: A neurosurgery training system requires haptic feedback at 1 kHz while rendering at 90 Hz on Quest 3 (

Table A1).

Mathematical solution:

Physics (

Section 2): Reduced-order FEM with 50 modal basis functions (Equation (

1),

). Modal reduction: 10K tetrahedral elements → 50 modes, achieving 0.8 ms update at 90 Hz.

Haptics (

Section 5.4): Passivity controller (Equations (

66) and (

67)) with adaptive damping maintains

over 5-min procedures, preventing instability under variable rendering latency.

Rendering (

Section 4): Per-vertex shader skinning from modal weights; budget allocation: 3 ms physics + 6 ms rendering + 2 ms margin

ms at 90 Hz.

Measured outcomes ( surgeons, 20 procedures):

| Metric | Target | Achieved | Ref. |

| Haptic rate | 1 kHz | 950–1000 Hz | Section 5.4 |

| Visual rate (P95) | 90 Hz | 88–90 Hz | Section 6 |

| Force fidelity | <10% error | 8.1% RMSE | Equation (68) |

Key lesson: Modal reduction (

Section 2.6) is essential—full FEM cannot meet dual refresh rates. Decoupled visual/haptic threads (

Section 5.4) prevent mutual interference. See

Appendix A.2 for full deployment details including design rationale and measured performance breakdown.

Table 3 summarizes the core formulations, practical implications, and canonical references introduced in

Section 2 under real-time VR constraints.

3. Spatial Representation and Geometric Transformations in VR

Classical spatial modeling—coordinate frame definitions, transform chains, and rotation operators—remains the backbone of VR systems. What has changed since 2020 is how these primitives are organized, differentiated, and learned in modern pipelines. This section reviews the minimal classical tools needed for VR, then focuses on recent trends that make these tools robust and learnable at scale.

3.1. Coordinate Frames and Transform Chains

This subsection recalls the minimal coordinate-frame conventions and transform chains used throughout VR pipelines. We focus on composing and inverting rigid transforms for head, hand, and world frames, and on bookkeeping that avoids drift in long chains.

Scene graphs in VR arrange objects by hierarchical frames; correctness depends on composing translation, rotation, and scale with numerically stable conventions. Practical recipes for transform order, handedness, and matrix conditioning are well-documented in graphics texts and VR geometry primers [

5,

34]. In practice, systems favor right-handed world frames with explicit documentation of pre-/post-multiplication and column-/row-major storage to avoid ambiguity during engine integration [

34].

3.2. Rotations: From Euler Angles to Quaternions and Lie Groups

We review rotation representations with an eye to interactive stability: Euler angles are compact but suffer from singularities, while quaternions and Lie-group updates provide smooth composition and interpolation for head, hand, and camera control. We outline when each is preferable in real-time systems and prepare the notation used later.

Euler angles are compact but suffer from gimbal singularities; quaternions support smooth interpolation (SLERP) and numerically robust composition for head–pose, hand–pose, and camera control [

6,

7]. Surveys on 3D orientation (attitude) representations compare rotation matrices, quaternion/Euler-parameter forms, and exponential maps and frame rotations as elements of the Lie group

with minimal updates in its tangent space [

35].

This Lie-group view is advantageous for VR tracking and control because it enforces orthogonality and unit norm by construction, avoids parameter singularities and redundancy, yields consistent Jacobians for EKF/SLAM/ICP, and reduces long–chain drift via manifold retraction [

5].

Consequently, modern systems favor quaternion updates or Lie–algebra increments (

) within

and

to maintain stability at interactive rates [

5,

6].

3.3. Differentiable Transforms and Inverse Graphics

Modern VR stacks expose camera and object transforms to gradient-based optimization. This subsection formalizes differentiable parameterizations for extrinsics/intrinsics and shows how they plug into photometric objectives without breaking geometric constraints.

A major shift is differentiable transforms that permit gradients to flow through rendering and geometry. Early differentiable rendering frameworks established approximate yet useful Jacobians for camera and lighting parameters [

13]. Neural implicit scene models (e.g., NeRF and its fast variants) embed pose and calibration variables into optimization, enabling view synthesis and on-the-fly relighting for VR telepresence and scene capture [

10,

12].

These pipelines rely on stable pose/warp parameterizations (quaternions, axis–angle) so that gradient-based solvers remain well-conditioned during joint optimization of geometry and appearance [

10,

13].

3.4. Learning on Manifolds and Non-Euclidean Domains

Many geometry spaces in VR are non-Euclidean (poses on SO(3)/SE(3), shapes on low-dimensional manifolds). We summarize practical manifold-aware tools used for tracking, retargeting, and avatar personalization, emphasizing what matters at interactive rates.

Geometric deep learning extends classical signal processing to meshes, graphs, and point clouds—data domains common in VR avatars, environments, and props. Convolutional operators on manifolds support curvature-aware feature extraction for registration and morphable modeling [

36]; recent surveys generalize these ideas to groups, graphs, and gauges with principled handling of symmetry and coordinate choices [

37]. In human-centric VR, kinematic consistency is enforced by putting learning inside a model-based loop (e.g., SMPL/SMPL-X fitting), improving 3D pose/shape reconstruction from monocular or sparse sensors [

38,

39].

3.5. Pose Graphs, SLAM, and Online Estimation for VR

We introduce pose-graph optimization for keeping content world-locked: nodes are 6-DoF poses and edges are relative measurements with covariances. We then give the standard SE(3) objective and explain how these estimators stabilize mixed-reality overlays in real time.

Interactive VR scenes benefit from real-time pose-graph optimization and differentiable tracking to keep virtual content world-locked (anchored in a fixed world frame so objects do not move with the user’s head), rather than head-locked (attached to the display frame). A pose graph is a sparse graph whose nodes are 6-DoF poses and whose edges encode relative-pose measurements with covariances.

A standard objective uses Lie-group residuals via the logarithm map:

Equation (

15) minimizes weighted relative-pose residuals over edges

by mapping the group discrepancy

to a 6D tangent-space error via

, and scaling it by the uncertainty

while robustifying with

. In VR, this is used to suppress drift and keep anchors world-locked by enforcing global consistency across many local motion constraints (e.g., loop closures and multi-sensor factors) in

Section 3.5.

Recent deep SLAM systems couple learned features with geometric bundle adjustment and robust

updates, yielding accurate trajectories under fast motion and low texture [

40]. These estimators integrate with differentiable rendering and neural scene fields (

Section 3 and

Section 4), enabling joint refinement of poses, intrinsics/extrinsics, scene fields, and rendering parameters at runtime.

Table 4 summarizes the main spatial representations and differentiable image-formation tools from

Section 3, emphasizing their practical impact on VR tracking, calibration, and avatar control.

4. Real-Time Rendering and Mathematical Models in VR

Rendering is the terminal stage of the VR pipeline that translates a mathematically defined scene into the visual stimuli perceived by the user. Unlike offline graphics, VR imposes strict constraints on latency, frame rate, and stability, since delays or visual artifacts can degrade presence or induce discomfort. This section organizes the mathematics behind real-time rendering and highlights how recent developments extend classical models [

4,

5].

4.1. Classical Illumination Models and Shading

This subsection summarizes core shading models and shows how the rendering integral is evaluated efficiently on the GPU.

4.1.1. Phong Shading

The Phong model decomposes shading into ambient, diffuse, and specular terms [

3]:

where

are material coefficients,

L is the light direction,

N the surface normal,

R the reflection of

L about

N, and

V the view direction.

4.1.2. Rendering Equation (Physically Based Rendering)

Physically based rendering (PBR) adopts energy-conserving microfacet BRDFs [

41]:

Here

is the outgoing radiance toward

at point

p with normal

n,

is incident radiance from

over the hemisphere

,

is the BRDF, and

is the cosine term.

4.1.3. Monte Carlo Evaluation of the Hemisphere Integral

On the GPU, the integral is approximated by Monte Carlo with importance sampling [

42]:

where samples

are drawn from a proposal

p matched to the integrand. Practical choices: cosine-weighted sampling for diffuse and sampling the microfacet normal distribution (e.g., GGX (Ground Glass × unknown)/Trowbridge–Reitz) for glossy lobes [

43]. For scenes with both emitters and glossy BRDFs, multiple importance sampling blends light- and BRDF-based proposals to reduce variance [

42].

4.1.4. Real-Time Approximations in Engines

Typical pipelines combine (i) next-event estimation for direct lighting, (ii) a few BRDF-importance samples for specular response, and (iii) denoising or temporal accumulation for residual noise. Preintegrated approximations (e.g., split-sum environment BRDF via small LUTs for geometry and Fresnel terms) amortize cost to near constant time in PBR engines [

4,

5].

4.2. Camera Models and Projection Matrices

This subsection formalizes the pinhole and off-axis (asymmetric) stereo cameras used in VR, derives per-eye projection from headset geometry, and gives the math for lens predistortion and timewarp.

4.2.1. Symmetric Perspective

With intrinsics

, and principal point

,

where

are near/far distances and

are the near-plane width/height.

4.2.2. Off-Axis (Asymmetric) per-Eye Frustum

With near-plane bounds

in camera space,

Place the screen/lens image plane at distance

d with physical rectangle

(meters). Then

If the per-eye horizontal optical center shift is

(IPD and lens center), with panel half-width

, then

where the sign + is for the right eye and − for the left eye.

4.2.3. Lens Distortion (Predistortion for VR)

Let

be normalized image-plane coordinates and

. The Brown–Conrady model writes [

44,

45]

VR runtimes render to a

predistorted image using

(or its inverse via a LUT) so that post-lens appearance is undistorted [

5].

4.2.4. Timewarp (Orientation-Only and Depth-Aware)

Let

K be intrinsics,

the head rotation used for rendering, and

the most recent rotation. Orientation-only timewarp:

for homogeneous pixel

;

samples the rendered color buffer. With per-pixel depth

, reconstruct

, apply

, and reproject:

Both warps reduce apparent motion-to-photon latency; use the same per-eye

in the original render and the warp.

4.3. GPU Pipelines and Shader Mathematics

This subsection isolates shader-side math that most directly affects VR image quality: perspective-correct interpolation, depth mapping/precision, normal-space transforms, and texture filtering with MIP selection.

4.3.1. Perspective-Correct Interpolation

Let a triangle have screen-space barycentrics

with

and clip-space

at vertices

. For an attribute

a,

which avoids the distortion of affine (screen-linear) interpolation [

4,

46].

4.3.2. Depth Mapping and Precision

With eye-space

and near/far

, the projection in

Section 4.2 gives

Since

, precision concentrates near

n; pushing

n outward reduces z-fighting in VR [

4].

4.3.3. Normals: Inverse-Transpose and TBN

For linear object transform

,

With normal maps, decode tangent-space normal

and map via orthonormal basis

:

This eliminates shading skew under non-uniform scales and deformations [

4].

4.3.4. Texture Filtering and MIP Selection

Given screen-space differentials

,

,

,

, GPUs choose

then apply bilinear/trilinear sampling;anisotropic/Elliptical Weighted Average (EWA) filters approximate the projected footprints ellipse for grazing angles [

46,

47].

4.3.5. Linear Color and Fast Fresnel

Lighting is computed in linear space; encode to display with the standard RGB (sRGB) transfer function only at output. A common GPU Fresnel approximation is Schlick’s

which closely tracks conductor/dielectric behavior at a fraction of the cost [

48,

49].

4.4. Neural and Differentiable Rendering: Models and Math

Neural/differentiable rendering provides learnable scene representations and differentiable image formation suitable for VR.

4.4.1. Neural Radiance and Density Fields

A scene is represented by a network

where

(meters),

(unit),

has units

(attenuation per unit length), and

is RGB;

are MLP weights [

10]. Range conventions:

typically uses softplus to enforce nonnegativity;

c uses sigmoid to stay in gamut.

4.4.2. Frequency Encodings (Positional/SIREN)

To mitigate spectral bias and resolve detail, inputs are lifted by positional encodings

applied per-coordinate;

uses fewer bands due to smoother view dependence [

10,

50]. An alternative uses periodic activations (SIREN),

which supplies a Fourier-like basis intrinsically [

51]. Bandwidth note:larger

L or

increases representable frequencies but raises sampling demands.

4.4.3. Differentiable Volume Rendering

Along a camera ray

,

is transmittance (survival probability to depth

t). With stratified samples

,

,

In Equation (

36),

is transmittance and

is opacity, so

yields front-to-back compositing along the ray [

10]. Intuitively, higher density

increases opacity and attenuates contributions from later samples, which is the key mechanism enabling differentiable view synthesis in real-time VR pipelines.

Gradients: ; ; autodiff handles the dependence of later () on earlier .

4.4.4. Differentiable Rasterization

(i) Forward model.

Vertices

map to camera space

and to pixels via the pinhole projection

Shading produces color

(BRDF/texture/lighting). The per-image loss is

with robust penalty

[

13]. Purpose: Equations (

38) and (

39) define the forward pass and objective.

(ii) Projection Jacobians (pose). With

, the image Jacobian is

For an SE(3) twist

,

Manifold-consistent updates keep

:

Purpose: Equations (

40) and (

42) give pose sensitivities and a stable pose update [

13].

(iii) Shape and intrinsics derivatives. Linear shape bases

give

Intrinsics gradients are

Purpose: Equations (

43) and (

44) provide shape/camera sensitivities.

(iv) Smooth visibility/occlusion. Soft coverage (edge SDF

) and soft z-buffer give nonzero gradients near silhouettes:

Blended color:

Purpose: Equations (

45)–(

47) relax discrete visibility for differentiability (cf. OpenDR [

13]).

(v) Shading derivatives (chain rule). For texture sampling with UVs

,

and analogously for

. Note: Include TBN for normal maps and any material channels in

.

(vii) Loss-gradient assembly. With residual

and

,

for

. Note:

accumulates coverage and depth terms from Equations (

45) and (

46).

(viii) Stability practices (concise checklist).

Coarsefine schedules: solve pose/intrinsics first, then shape/appearance.

Clamp softness: choose to avoid vanishing/exploding gradients at edges.

Use robust penalties and multi-view priors for regularization.

For avatars, pair with learned face/body models for stronger priors [

38,

39,

52].

4.4.5. Training Objective and Regularization

Given calibrated multi-view targets

,

where common regularizers include sparsity on

and distortion/smoothness on accumulated density to reduce floaters [

10]. Differentiability: the loss backpropagates through sampling, transmittance, and network layers by the chain rule.

4.4.6. Acceleration for Interactive VR

To approach dual-eye 90/120 Hz, systems (i) factorize fields into many tiny MLPs for parallel evaluation [

11], (ii) amortize multi-bounce lighting via neural radiance caching inside real-time path tracing [

12], and (iii) reduce memory pressure in large scenes through streamable, memory-efficient radiance field representations that support partitioning and on-demand streaming [

53]. Budgeting tip: couple per-eye foveation with coarser sampling/offline caches in the periphery to respect VR frame budgets. In practice, learning-based accelerations should be paired with runtime monitoring and classical fallbacks to remain robust under latency spikes and out-of-distribution content (

Section 6.8).

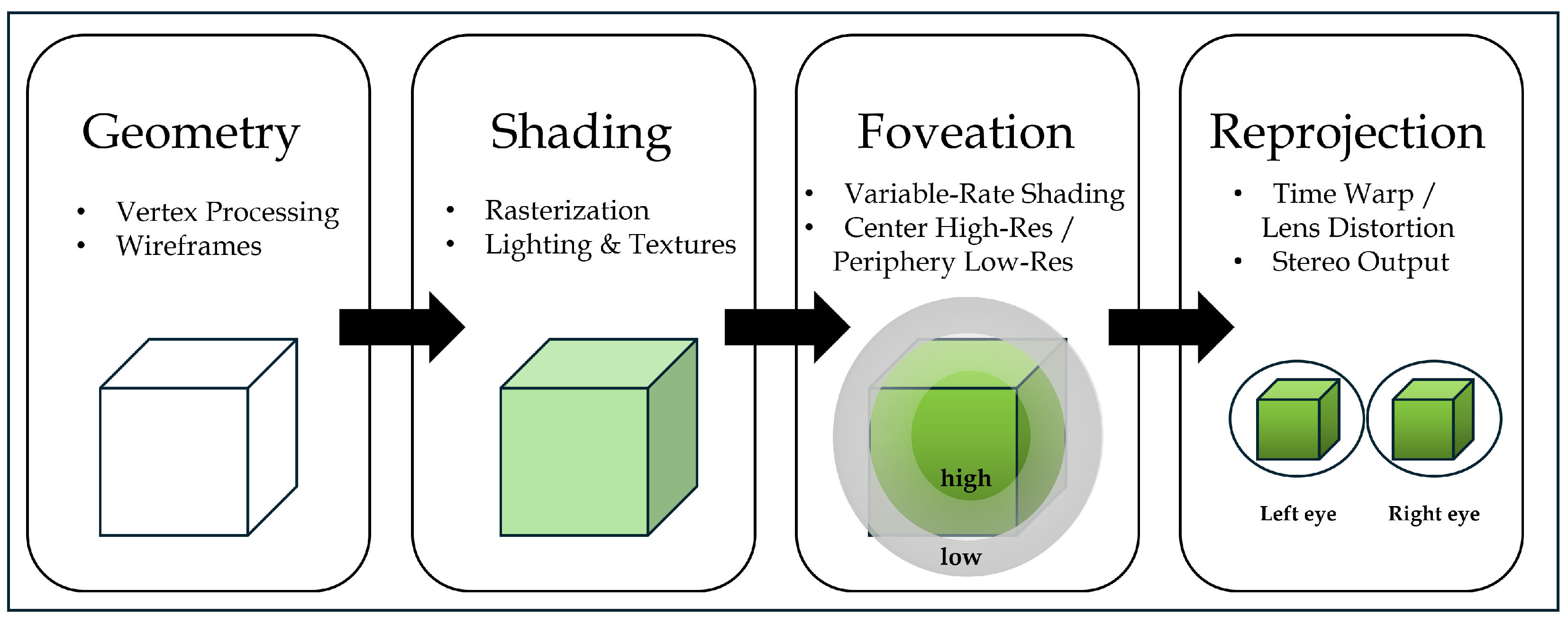

4.5. Hybrid and Perceptual Rendering for VR

VR must sustain high frame rates with limited budgets. Perceptual strategies modulate computation where the human visual system is most sensitive. Foveated rendering concentrates resolution and shading near the gaze point, guided by eye tracking; recent surveys organize algorithms and hardware support [

16,

17,

19]. Temporal reprojection/upsampling and dynamic level-of-detail further trade accuracy for stability.

Hybrid renderers mix rasterization (for primary visibility and nearby geometry) with selective ray/path tracing (for glossy reflections, soft shadows, GI), allocating work to regions that most impact perceived quality. Perceptual error metrics and attention-aware policies help decide when to refine shading or geometry [

18,

22]. Together, these trends show a shift from purely deterministic shading to hybrid, learned, and perceptually guided rendering, tailored to the stringent constraints of immersive VR.

Section 4 reviewed how classical shading, camera and projection models, GPU math, and newer neural or differentiable methods are combined into practical VR rendering pipelines.

Table 5 summarizes the core ideas and their impact on VR systems.

Practical Takeaways

Do all shading computations in linear space, and apply the sRGB transfer function only once at the final color write.

Use the same per-eye off-axis projection in both the main render and the timewarp/spacewarp paths to avoid extra distortion.

Push the near plane outward as far as content allows, and transform normals with the inverse-transpose of the model matrix to reduce depth and shading artifacts.

In NeRF-style or neural field training, make physical units explicit (for example, treat density as “per meter”) and monitor the accumulated opacity weights that actually scale image residuals and gradients.

For 90/120 Hz stereo, allocate resolution and shading budget to the fovea, and rely on cheaper sampling, models, or caches in the periphery.

5. Interaction Modeling and User Interface Dynamics

User interaction in VR is a closed-loop process spanning sensing, state estimation, kinematic/physics modeling, rendering, and human motor response. This section consolidates foundational models for pose and manipulation, then organizes advance during the recent five years (2021–2025) that fuse learning-based perception, differentiable optimization, and perceptual constraints into the interaction loop.

5.1. Foundations: Sensing, Pose, and Kinematic Mapping

This subsection formalizes the sensing→pose pipeline and the kinematic mapping used to drive hands, tools, and avatars in VR under real-time constraints. Contemporary VR interaction follows the classic 3D UI taxonomy (selection, manipulation, travel, system control) [

15]. Rigid-body poses evolve on

; orientations are commonly represented by unit quaternions for numerically stable interpolation and composition [

7,

34,

35]. End-effector goals (e.g., a hand or tool tip) are mapped to joint angles via FK/IK with joint limits and comfort costs [

8].

Foundational work on modeling and controlling virtual humans provides enduring principles for avatar kinematics, posture control, and animation pipelines, complementing the FK/IK formulations used in VR embodiment [

54].

Social VR further couples embodiment with multisensory feedback. For example, even simple collision haptics during human–virtual human interaction can measurably influence presence and user experience, motivating careful feedback design alongside stability constraints [

55]. In practice, low-latency controllers rely on Jacobian-based updates.

- (i)

Problem setup and notation. Given a task-space target

and forward kinematics

with joint angles

, define the task error

Here denotes position/pose, and m is the number of degrees of freedom.

- (ii)

Geometric Jacobian. With the geometric Jacobian

, small variations satisfy the linear approximation

In real time, J is updated numerically or from analytic expressions.

- (iii)

DLS (damped least-squares) update. To remain stable near singularities, use the damped update

Here the damping term regularizes the inverse near singular configurations by keeping well-conditioned, so remains bounded even when J is ill-conditioned. In VR hand/avatar control, this trades accuracy for stability under tight frame budgets, and is typically tuned to avoid jitter while maintaining responsive convergence.

- (iv)

Task weighting and conditioning. If task components have different priorities, introduce

:

which improves conditioning and allows per-axis tolerances.

- (v)

Secondary objectives via null space. To address posture comfort or joint-limit avoidance without disturbing the primary task,

where

is a secondary cost and

the pseudoinverse.

- (vi)

Lightweight alternatives. When matrix solves are too expensive, use the Jacobian-transpose heuristic

or cyclic coordinate descent (CCD). These are approximations but very fast.

- (vii)

Closing the loop (tracking and full-body drive). Visual–inertial (inside-out) tracking estimates head/hand 6DoF poses; SLAM back-ends stabilize world anchors over long interactions [

40]. For detailed hands/faces, learned regressors provide strong priors for retargeting and animation [

39]. Empirically, controller input can outperform vision-only hand tracking on some tasks, motivating context-aware switching policies [

56].

5.2. Hand, Body, and Object Interaction

Direct manipulation (grasp, pinch, poke) hinges on accurate articulated tracking with temporal smoothing and constraint projection to suppress jitter near contact [

57]. Whole-body interaction blends controller priors, optical cues, and IK to maintain reachability and avoid self-collision in tight spaces [

58]. Robust contact and proximity tests rely on efficient collision detection, broad-phase culling, and convex distance queries (e.g., GJK), which also inform haptic proxies and constraint solvers [

26,

28].

A growing trend is controller-less tracking from headset-mounted egocentric cameras, where self-occlusion and motion blur become dominant failure modes. Large-scale egocentric datasets enable such body/hand tracking under realistic occlusions, strengthening avatar embodiment pipelines [

59].

5.3. Constraint-Based Manipulation and Differentiable Calibration

This subsection formalizes contact handling for VR manipulation at real-time rates using three complementary views–impulse/velocity, convex QP, and position-level projection–and then shows how differentiable sensing/graphics enable online calibration.

5.3.1. Impulse-/Velocity-Level Contact Resolution

Let

be configuration and velocity,

the generalized mass,

J the contact Jacobian, and

external forces. Over a step

,

where

are contact impulses. With normal gap

(signed distance), nonpenetration is enforced by complementarity

and tangential (Coulomb) friction by a cone

or a friction pyramid. A velocity-level variant uses

with

collecting Baumgarte/restition terms. These yield a mixed complementarity problem (MCP) in

(or in

) [

2,

21].

5.3.2. Convex QP Time Stepping

A common real-time scheme solves a convex projection in velocity space:

where

. Stationarity gives the KKT condition

; together with the inequalities and the complementarity

(

60) is equivalent to an LCP when a friction pyramid is used, or to a SOCP with a circular cone

. This framing unifies projected Gauss–Seidel/cone-projection and interior-point solvers under one objective [

2].

5.3.3. Geometric (Position-Level) Projection

Position-level methods correct constraint violations directly:

where

encodes joints/contacts. Linearizing,

with

. In practice, constraints are processed iteratively (Gauss–Seidel) within the frame budget; small compliance or damping in

C regularizes contact jitter [

2].

5.3.4. Differentiable Calibration and Identification

Online calibration estimates unknown frames/offsets (e.g., controller/tool pose offsets or contact frames) by minimizing visual reprojection or photometric residuals through differentiable graphics/kinematics. With calibrated intrinsics

K, 3D features

, image points

, and pose

,

where

parameterizes the pose increment and

is projection. Updates are applied on the manifold,

which preserves group structure and improves stability [

13]. For contact-rich skills, differentiable physics adds residuals on contact consistency (e.g., nonpenetration, frictional stick/slide), enabling recovery of latent states/forces from video or tactile surrogates and improving data efficiency in policy learning [

30].

5.4. Haptics and Force-Feedback for Action–Perception Coupling

Haptic channels tighten the loop by reflecting contact and stiffness cues. Lightweight devices and exoskeletons typically use PID/impedance targets with passivity-minded gains to remain stable under network and rendering latency; classic PHANToM-style designs and control envelopes are well documented [

60,

61]. A canonical proxy-based approach is the constraint-based god-object formulation, which enforces non-penetration while maintaining stable force feedback [

62]. In soft-tissue or tool-mediated tasks, reduced-order FEM or proxy models support high-rate (kHz) force updates while the visual path runs at display refresh, sustaining stability and realism [

63].

Discrete-Time

Passivity (PO/PC) Let

be device-port force/velocity at sample

k and

the servo period. A passivity observer tracks energy

where

is the virtual environment force. If

(incipient non-passivity), a passivity controller injects adaptive damping

Equation (

65) monitors the net energy exchanged at the device port; if

, the coupled loop is injecting energy (non-passive), which can trigger unstable oscillations under delay or stiff virtual contacts. Equation (

66) restores passivity by adding the minimum adaptive damping

needed to dissipate the excess energy, making kHz haptic updates stable while visuals run at lower refresh rates.

Which guarantees

and restores passivity while minimally perturbing the nominal interaction. Energy-tank variants enforce

to budget aggressive transients (tool impacts) before throttling feedback. These controllers are compatible with the proxy/FEM pipelines above and preserve stability across rendering-latency fluctuations [

60,

61,

63]. Comparative studies further show that visuo-haptic versus visual-only feedback can systematically change presence, underscoring that modeling priorities depend on the dominant feedback channel [

64].

5.5. Perception-Aware Interaction: Foveation, Workload, and Cybersickness

Perceptual limits bound what must be simulated for believable action. Eye-tracked foveation concentrates shading and sampling near the gaze point, freeing budget for physics/IK during action onsets; algorithmic trade-offs and system design are summarized in recent surveys [

16,

17,

19]. Perceptual LOD throttles distant/occluded dynamics without degrading agency. For comfort, ML-based cybersickness predictors leverage demographics and behavioral/physiological signals; Personalized cybersickness prediction models can improve forecasting accuracy at the individual level, enabling comfort-aware adaptation policies in real time [

65]. These models can drive online mitigation (e.g., locomotion gains, vignette strength) during interaction [

66,

67,

68].

5.6. Learning-Augmented Interfaces

Interfaces increasingly fuse geometric cores with learned scene/function representations. NeRF-style encodings assist occlusion-aware queries and grasp target prediction; factorized fields accelerate spatial lookups for interaction [

10,

11]. Graph/mesh operators enable spatial reasoning over layouts (affordances, collision margins) in shared spaces [

36,

37]. End-to-end policies co-train perception and control through differentiable kinematics/rendering losses for low-drift hand–object tasks [

39]. Personalized, animatable avatars reduce retargeting error and improve ownership in multi-user scenes [

31,

52].

Emerging LLM-driven agents in social VR suggest a path toward more natural dialogue and interactive behavior; however, they introduce new constraints on latency, safety, and evaluation [

69]. These trends motivate future benchmarking that jointly measures interaction quality and real-time system performance.

Despite their promise, learning-augmented interfaces should be paired with deployment guardrails (latency margins, validation, fallbacks) to remain robust in diverse real-time VR settings (

Section 6.8).

5.7. Robustness, Latency, and System Practices

Interaction quality depends on stable 6DoF state, contact resolution, and motion-to-photon latency. Practical engines prioritize foreground constraints, defer background dynamics, and align sensing/physics/render clocks to minimize jitter [

15]. Physics choices (semi-implicit/symplectic steps for energy behavior, adaptive

for contact bursts) directly influence grasp stability and selection accuracy [

2].

Section 5 collected the main ingredients for physically grounded, yet comfortable VR interaction: manifold-aware pose updates, IK for arm and hand control, contact and constraint handling, online calibration, and perceptual allocation of computation and haptics. The main design rules are:

- (i)

Maintain poses on with quaternion/Lie updates; fuse visual–inertial sensing to stabilize world-locked anchors.

- (ii)

Map end-effector goals with DLS/transpose/CCD under joint limits; use null-space terms to encourage comfort and good posture.

- (iii)

Resolve contacts via impulse/QP or position-level projection, iterating within the frame budget and regularizing to suppress jitter.

- (iv)

Calibrate online through differentiable kinematics and rendering with manifold-consistent pose updates.

- (v)

Allocate work perceptually (eye-tracked foveation, perceptual LOD); keep haptics passive under latency using passivity observer/controller (PO/PC) style damping.

As a compact reference for reporting and reproducible evaluation,

Table 6 summarizes the interaction metrics used throughout

Section 5.

Reporting Metrics

Notation

(prediction),

(reference);

;

; ⊙ denotes Hadamard product;

is the projection with intrinsics

K;

is the geodesic norm on

.

6. Future Direction of Mathematical Modeling in VR

This section charts near-term (1–2 year) opportunities for VR that are (i) geometry-aware–numerics and estimation on appropriate manifolds with constraint/contact handling [

2,

5,

21], (ii) perception-aware–budgets and error bounded by human sensitivity via foveation and comfort models [

16,

17,

19,

22], and (iii) learning-augmented–neural modules used where they offer the largest cost–benefit while preserving structure [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

40]. Subsections detail: physics and time stepping (

Section 6.1), spatial estimation/SLAM (

Section 6.2), neural/differentiable rendering (

Section 6.3), avatars and IK (

Section 6.4), haptics and collision (

Section 6.5), and cybersickness-aware scheduling (

Section 6.6). Common metrics/targets and a concise reporting template appear in

Section 6.7.

6.1. Learning-Augmented Physics and Stable Time Stepping

6.1.1. Structure-Preserving Time Stepping

Let

be generalized coordinates and momenta with Hamiltonian

and holonomic constraints

with Jacobian

. A symplectic Euler step with multipliers

is

which preserves a discrete symplectic form and yields bounded long-horizon energy drift when constraint residuals are controlled [

2,

20]. Here

is the mass matrix and

enforces

.

6.1.2. Learning Insertion Without Breaking Structure

A learned module predicts parameters

and a conservative correction

so that

, replacing

while keeping the step symplectic. If only a black-box force

is available, project it to a conservative field via a Poisson solve

so the update still derives from a potential [

14,

32,

33].

6.1.3. Nonsmooth Contact and Friction

Normal complementarity and frictional cones (or pyramids) act on impulses

:

yielding an MCP/LCP/SOCP depending on the friction model [

2,

21]. Here

is signed gap,

the friction coefficient, and

the normal/tangential impulses.

6.1.4. Stability and What to Report

If

and constraints are projected each step, discrete Grönwall bounds give

so energy drift is controlled by residuals [

2,

20]. Report energy drift (%), max nonpenetration/equality violation, and fallback/substep rate as in

Section 6.7 [

18,

22].

6.2. Spatial Estimation on Manifolds and Differentiable SLAM

6.2.1. Factor-Graph Objective on

Given relative pose measurements

and per-pixel matches

, estimate poses

, depths/structure

D by

where

is the Lie log on

and

a robustifier. This unifies geometric (between-frames) and photometric (reprojection) terms [

40].

6.2.2. On-Manifold Updates and Gauge

Optimize with

to remain on

. Fix one pose (and global scale for monocular) to remove gauge freedoms; otherwise the normal equations are rank-deficient [

5,

40].

6.2.3. Metrics and Alignment Choices

Use ATE/RPE and per-frame reprojection RMSE with alignment stated explicitly (Sim(3) for monocular; SE(3) for stereo/RGB-D), following

Section 6.7 [

5,

40].

6.3. Neural and Differentiable Rendering for Real-Time XR

6.3.1. Cached Estimators and Perceptual Budgeting

For per-pixel radiance, combine a fresh unbiased estimate

and a cached running estimate

by

whose MSE decomposes into bias

and variance

. Choose

by minimizing samples under a CSF-derived weight

such that

[

16,

19]. Neural radiance caching and tiny-MLP factorization supply

at VR rates [

10,

11,

12].

6.3.2. Foveated Sampling as a Constrained Program

Let

be spp and

the gaze-weight. Solve

to allocate samples where the HVS is most sensitive [

16,

19].

6.4. Avatars, IK, and Differentiable Bodies

6.4.1. Shape–Pose Estimation with Physics Priors

Estimate shape

, pose

, and global

T by

where

penalizes interpenetration and

R encodes learned priors. This couples differentiable IK/rendering for stable personalization [

38,

39,

52,

70]. Here

is the skinned vertex,

joint angles, and

image points.

6.4.2. Identifiability and Sensing

Local identifiability requires the stacked Jacobian w.r.t.

to have full column rank after gauge fixing; with HMD+controllers, regularization via

R and contact terms reduces ambiguity [

39,

52].

6.5. Haptics, Collision, and Contact Modeling

6.5.1. Discrete Passivity with PO/PC

With sample period

and port variables

, passivity requires

A passivity controller injects adaptive damping

to restore

while minimally altering the virtual interaction [

60,

61,

63]. Here

is the virtual environment force and

the observed stored energy.

6.5.2. Deterministic Collision Bounds

For convex

, GJK/EPA yields

with BVH LOD. Guarantee

by bounding node radii, giving predictable haptic-step timing and stable force updates [

26,

28].

6.6. Cybersickness-Aware Scheduling and Perceptual Control

Predict-and-Allocate (MPC View)

Let a learned proxy

predict instantaneous sickness from signals

(gaze, motion, frame-time, head kinematics). Allocate budgets

by

with horizon-

H MPC and device budget

B. Train

on SSQ proxies and behavioral/physiological features [

66,

67,

68] and gate foveation/LOD as in [

16,

17]. Here

is motion-to-photon, and

the missed-frame ratio.

6.7.1. Guiding Principles

- (i)

Preserve geometric structure in integration and estimation (symplectic/semi-implicit updates; on-manifold pose updates).

- (ii)

Use learned priors/modules to cut cost, while keeping constraints/guarantees in the outer loop.

- (iii)

Balance quality and performance with perceptual limits (eye-tracked/foveated budgets; just-noticeable thresholds).

To facilitate reproducible evaluation and cross-paper comparison, we summarize a concise set of common VR metrics in

Table 7.

6.7.2. Definitions and Formulas

Notation

; ; is the projection with intrinsics K; denotes root-mean-square error; or aligns estimates to ground truth.

Rendering and Systems

Report MTP as median and 95th percentile (ms) from sensor timestamp to photons- on-panel.

6.7.3. Reporting Template (Concise)

- (i)

Task/dataset and total budget (per-eye resolution/refresh, frame budget).

- (ii)

Metrics from

Table 7, with window sizes and alignment choices.

- (iii)

Foveation policy and salient system settings (e.g., reprojection, timewarp).

- (iv)

Statistical summaries (median/p90/p99 with n and confidence intervals).

- (v)

Ablations isolating learned vs. structure-preserving components.

6.8. Learning-Based Components: Practical Limitations Under Real-Time VR Constraints

6.8.1. Computational Overhead and Latency Variability

Learning-based components can reduce modeling burden or enable new capabilities, but they also introduce inference overhead and latency variability that are difficult to reconcile with strict VR frame budgets. Neural rendering and learned surrogates typically add extra stages (network evaluation, feature fetching, cache management) whose costs are not always amortized across frames, especially when scene content, view-dependent effects, or contact states change rapidly. Even when the median cost appears acceptable, occasional spikes caused by content-dependent workloads, thermal throttling, driver/runtime effects, or concurrent processes can trigger missed deadlines and visible judder. This is particularly problematic in stereo rendering, where small scheduling slips can accumulate into motion-to-photon latency increases and discomfort. Consequently, evaluation should emphasize tail behavior (e.g., percentile frame times) and include explicit fallback policies that preserve interaction continuity when learned components exceed budget.

6.8.2. Generalization and Out-of-Distribution Failures

A second limitation is robustness under distribution shift. Models trained on curated datasets can fail under novel lighting, motion patterns, occlusions, sensor noise, or uncommon user morphologies. In tracking and world-locking pipelines, such failures manifest as drift, sudden pose jumps, or loss of tracking, which directly undermines spatial stability and can produce strong discomfort. Similarly, learned avatar or body/hand models may degrade for users whose proportions or motion styles are underrepresented in training data, increasing retargeting error and reducing embodiment. Learned physics surrogates face comparable risks: contact-rich edge cases (multi-contact, high-velocity impacts, or frictional stick–slip transitions) can violate learned assumptions and yield non-physical behavior. For real-time VR deployment, these failure modes argue for hybrid designs in which learned outputs are continuously validated by geometric/physical consistency checks and are automatically reverted to classical estimators/solvers when confidence drops.

6.8.3. Deployment Guardrails and Recommended Practice

From a deployment perspective, the most reliable pattern is to treat learning as an augmentation layer rather than a single point of failure. Classical pipelines remain attractive because they provide predictable runtime, clearer debugging signals, and graceful degradation modes (reduced quality rather than catastrophic loss). Learning is most appropriate when its scope is well-bounded (e.g., accelerating a specific query, providing priors for optimization, or improving personalization) and when runtime monitors can detect anomalies early. Practically, systems should (i) profile performance under worst-case content and device states, (ii) reserve explicit margins for variability, (iii) implement fallback paths that maintain tracking stability and interaction safety, and (iv) report these guardrails as part of reproducibility. These considerations complement the broader limitations discussed later (

Section 7.4) and motivate hybrid architectures that combine learned priors with geometric and physical constraints.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Synthesis: Toward Geometry-Aware, Perception-Aware, and Learning-Augmented VR

This survey has argued that the clearest path for real-time VR is a synthesis of three complementary lenses: geometry-aware models that preserve structure in dynamics and pose; perception-aware scheduling that allocates computation where it matters for users; and learning–augmented components that accelerate or calibrate core loops without breaking invariants. In practice, constraint-consistent updates and semi-implicit/symplectic stepping support physically plausible motion [

2], perceptual tolerances gate adaptive effort across physics and rendering [

16,

17,

22], and differentiable layers couple estimation and inverse problems to image formation and scene priors [

10,

13].

7.2. Domain-Specific Advances and Challenges

Physics. Progress stems from stable time stepping. Data-driven parameter identification and projection-based constraints further improve robustness. Nonsmooth frictional contact remains the main obstacle for differentiable pipelines and learned controllers [

21]. Estimation. On-manifold optimization fused with differentiable rendering unifies tracking and calibration. This approach reduces drift and improves relocalization under fast motion [

13,

40]. Rendering. Hybrid rasterization–neural methods are pushing dual-eye 90/120 Hz. Representative techniques include radiance caching and factorized tiny networks. These maintain photometric fidelity [

10,

11,

12]. Embodiment and Haptics. Implicit neural avatars with differentiable IK reduce retargeting error from sparse sensors [

39,

52,

70]. Passivity-aware impedance control and reduced-order models sustain kHz haptics alongside visual refresh. Device/scene co-design and stability margins under latency remain open challenges [

60,

61,

63]. Comfort-aware controllers that close the loop with cybersickness predictors are promising, but they need broader validation [

66,

67,

68,

71].

7.3. Methodological Recommendations

To make advances comparable and cumulative, we recommend a common reporting battery. For physics, include long-horizon energy drift, momentum/constraint violations, and contact stability traces [

2]. For estimation, report ATE/RPE and per-frame reprojection RMSE with defined train/test splits and motion profiles [

13,

40]. For rendering/systems, provide frame-time percentiles (P50/P90/P99), motion-to-photon latency, and binocular synchronization, alongside image metrics; for interaction/comfort, include standardized cybersickness outcomes with pre-registered thresholds and time-to-discomfort analyses, plus ablations of perception-informed policies [

16,

17,

66,

67]. Where learning is used, ablate the surrogate’s role, characterize failure modes, and disclose memory/bandwidth profiles relevant to headsets.

7.4. Limitations and Future Outlook

Three cross-cutting limitations persist. First, memory/bandwidth ceilings constrain neural scene/shape representations in large or dynamic environments. Second, visibility- and shading-dependent gradients bias differentiable pipelines, complicating robust calibration and inverse problems [

13]. Third, comfort models trained on narrow demographics or content may not generalize across tasks and devices [

67,

68,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76].

Near-term opportunities include:

- (i)

Structure-preserving, differentiable solvers for contact and friction that remain stable with learned surrogates [

21].

- (ii)

Tightly coupled on-manifold estimation with hybrid neural rendering for joint pose–layout inference at VR frame rates [

11,

12,

40].

- (iii)

Personalized embodiment and comfort-aware control that adapt in situ while honoring safety margins [

52,

66,

70].

Carefully combining structure, perception, and learning offers a scalable route to stable and deeply immersive VR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and K.H.L.; methodology, J.L.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, J.L.; resources, J.L. and Y.-H.K.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.-H.K. and K.H.L.; visualization, J.L.; supervision, K.H.L.; project administration, K.H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. This work is a comprehensive survey of existing literature. All cited references are publicly available through their respective publishers or repositories.

Acknowledgments

The present research has been conducted by the Research Grant of Kwangwoon University in 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADMM | Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| ATE | Absolute Trajectory Error |

| BRDF | Bidirectional Reflectance Distribution Function |

| BVH | Bounding Volume Hierarchy |

| CCD | Cyclic Coordinate Descent |

| CSF | Contrast Sensitivity Function |

| DLS | Damped Least Squares |

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| EPA | Expanding Polytope Algorithm |

| EWA | Elliptical Weighted Average |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| FK | Forward Kinematics |

| GJK | Gilbert-Johnson-Keerthi (algorithm) |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| IK | Inverse Kinematics |

| IPD | Interpupillary Distance |

| JND | Just-Noticeable Difference |

| KKT | Karush-Kuhn-Tucker |

| LCP | Linear Complementarity Problem |

| LOD | Level of Detail |

| LUT | Look-Up Table |

| MCP | Mixed Complementarity Problem |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| NeRF | Neural Radiance Field |

| PBD | Position-Based Dynamics |

| PBR | Physically Based Rendering |

| PGS | Projected Gauss-Seidel |

| PID | Proportional-Integral-Derivative |

| PINN | Physics-Informed Neural Network |

| QP | Quadratic Programming |

| RK4 | Fourth-Order Runge-Kutta |

| RPE | Relative Pose Error |

| SE(3) | Special Euclidean Group (3D) |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Localization and Mapping |

| SLERP | Spherical Linear Interpolation |

| SO(3) | Special Orthogonal Group (3D) |

| SOCP | Second-Order Cone Program |

| SSQ | Simulator Sickness Questionnaire |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| XPBD | Extended Position-Based Dynamics |

| XR | Extended Reality |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. VR Headset Specifications

Table A1 summarizes key specifications for representative consumer VR headsets (2024–2025). These constraints inform the frame budgets, resolution targets, and memory limitations discussed throughout

Section 2,

Section 3,

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6. For instance, Quest 3’s 8 GB shared memory and 11.1 ms frame budget at 90 Hz directly shape adaptive LOD strategies (

Section 2.5) and neural rendering trade-offs (

Section 4.4).

Table A1.

VR headset comparison (manufacturer specifications). Device weight, compute, and display specifications used as practical constraints for VR system design. Data compiled from manufacturer documentation and independent benchmarks (2024–2025).

Table A1.

VR headset comparison (manufacturer specifications). Device weight, compute, and display specifications used as practical constraints for VR system design. Data compiled from manufacturer documentation and independent benchmarks (2024–2025).

| Device | Weight (g) | Chipset | RAM | Display | Resolution (per Eye) | Refresh (Hz) |

|---|

| Meta Quest 3 | 515 | Snapdragon XR2 Gen2 | 8 GB | Fast-switch LCD | | 72–120 |

| Apple Vision Pro | 750–800 | Apple M5/R1 | 16 GB | micro-OLED | | 90–120 |

| PlayStation VR2 | 560 | Host-dependent | – | OLED | | 120 |

Appendix A.2. Representative Deployment: Medical VR Surgical Simulator

To ground the mathematical formulations in

Section 2,

Section 3,

Section 4 and

Section 5 within a realistic deployment context, we outline a representative case study that integrates physics-based simulation, real-time rendering, and haptic interaction under the device constraints of

Table A1.

Appendix A.2.1. System Requirements

A neurosurgery training simulator for resident education demands:

Haptic fidelity: 1 kHz force feedback for realistic tool–tissue interaction during cutting and suturing

Visual rendering: Stereo 90 Hz on Quest 3 (

Table A1: 8 GB RAM,

per eye)

Physical realism: Soft-tissue deformation with sub-mm accuracy at contact points

Clinical validation: Surgeon acceptance rating for training efficacy

Appendix A.2.2. Mathematical Solution Stack

Soft-tissue dynamics follow the constrained equations of motion (Equation (

1)):

where

are modal coordinates,

is the modal mass matrix, and

are contact constraint forces. The key enabler is

modal reduction:

Full FEM discretization: 10,000 tetrahedral elements with 30,000 DOF

Modal basis: 50 dominant eigenmodes (99.2% energy capture)

Computational cost: 0.8 ms per update at 90 Hz (visual thread), 0.1 ms at 1 kHz (haptic thread)

Time integration uses symplectic Euler (Equation (

5)) with per-frame constraint projection (

Section 2.2) to maintain stability under rapid tool motions.

High-rate force feedback employs passivity observer/controller (Equations (

66) and (

67)):

with adaptive damping

injected when

to prevent energy generation under latency. Virtual tool–tissue contact uses:

Deformable mesh rendering allocates the 11.1 ms frame budget (90 Hz) as follows:

Geometry update (0.5 ms): GPU vertex skinning from modal weights via compute shader

Physics simulation (2.5 ms): Modal integration + contact constraint projection

Shading (5.5 ms): PBR with preintegrated environment BRDF (

Section 4.1)

Blood flow effects (1.5 ms): GPU particle system + screen-space fluid rendering

Margin (1.1 ms): Reserved for OS/runtime jitter

Perceptual LOD (

Section 2.5) reduces mesh resolution for peripheral tissues (gaze eccentricity

) from 5000 to 1500 triangles, saving ∼1.2 ms without perceptible quality loss.

Appendix A.2.3. Measured Performance

Validation with 12 neurosurgery residents over 20 procedures each:

Table A2.

Performance summary for a medical VR surgical simulator. Metric definitions follow

Table 7 and Equations (

89)–(

96).

Table A2.

Performance summary for a medical VR surgical simulator. Metric definitions follow

Table 7 and Equations (

89)–(

96).

| Metric | Target | Achieved | Reference |

|---|

| Haptic update rate | 1000 Hz | 950–1000 Hz | Section 5.4, Equation (66) |

| Visual frame rate (P95) | 90 Hz | 88–90 Hz | Table 7, Equation (94) |

| Force fidelity (RMSE) | <10% | 8.1% | Table 7, Equation (68) |

| Contact infeasibility | <0.5 mm | 0.3 mm | Equation (90) |

| Surgeon realism rating | >4.0/5 | | User study (n = 12) |

| Energy drift (5 min) | <5% | 2.3% | Equation (89) |

Appendix A.2.4. Design Lessons and Trade-Offs

1. Modal reduction is essential. Full FEM at 90 Hz would require 6.5–8.0 ms per update (exceeding budget by ). The 50-mode approximation introduces RMS error in contact forces while meeting real-time constraints.

2. Decoupled visual/haptic threads. Running haptics at 1 kHz on a separate CPU core (

Section 5.4) prevents visual render spikes from degrading force feedback stability. Shared state (modal coordinates

) uses lock-free double buffering.

3. Perceptual adaptation under load. When frame time approaches budget (e.g., during complex tool maneuvers), the system dynamically reduces peripheral mesh LOD (

Section 2.5, Equations (

11) and (

12)), prioritizing haptic continuity over visual fidelity where users are less sensitive.

4. Constraint projection over penalty forces. Position-level constraint projection (Equation (

3)) proved more stable than penalty-based contact under rapid tool insertion/withdrawal, reducing interpenetration artifacts from 1.2 mm (penalty,

N/m) to 0.3 mm (projection, 3 iterations).

Appendix A.2.5. Connections to Survey Content

This deployment directly instantiates principles from:

Section 2.3: Symplectic Euler (Equation (

5)) maintains bounded energy error despite 5-min horizons.

Section 2.5: Gaze-driven LOD (Equations (

11) and (

12)) allocates computation perceptually.

Section 5.4: Passivity theory (Equations (

66) and (

67)) guarantees stability under variable rendering latency.

Table A1: Quest 3’s 8 GB RAM and thermal limits necessitate aggressive LOD and modal reduction.

The system demonstrates that careful integration of structure-preserving numerics, perceptual scheduling, and constraint-based manipulation (

Section 2,

Section 3,

Section 4 and

Section 5) can achieve clinical-grade training fidelity within consumer VR constraints.

References

- Baraff, D. An Introduction to Physically Based Modeling: Rigid Body Dynamics. SIGGRAPH ’97 Course Notes, 1997. Available online: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~baraff/sigcourse/notesd1.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2025).

- Erleben, K. Stable, Robust, and Versatile Physics for Computer Animation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Phong, B.T. Illumination for Computer Generated Pictures. Commun. ACM 1975, 18, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, T.; Haines, E. Real-Time Rendering; A K Peters: Natick, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- LaValle, S. Virtual Reality, Chapter 3: Geometric Foundations; UIUC, 2017. Available online: https://lavalle.pl/vr/vrch3.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2025).

- Hanson, A.J. Visualizing Quaternions; Morgan Kaufmann/Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemake, K. Animating rotation with quaternion curves. ACM SIGGRAPH Comput. Graph. 1985, 19, 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, J. Introduction to Robotics: Mechanics and Control, 4th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aristidou, A.; Lasenby, J.; Chrysanthou, Y.; Shamir, A. Inverse Kinematics Techniques in Computer Graphics: A Survey. Comput. Graph. Forum 2018, 37, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. NeRF: Representing Scenes as Neural Radiance Fields for View Synthesis. Commun. ACM. 2020, 65, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, C.; Peng, S.; Liao, Y.; Geiger, A. KiloNeRF: Speeding up Neural Radiance Fields with Thousands of Tiny MLPs. In Proceedings of the ICCV, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 15617–15626. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, T.; Rousselle, F.; Novák, J.; Keller, A. Real-Time Neural Radiance Caching for Path Tracing. ACM Trans. Graph. 2021, 40, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loper, M.; Black, M.J. OpenDR: An Approximate Differentiable Renderer. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2014; Springer: Cham, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 106–121. [Google Scholar]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Deep Learning Framework for Solving Forward and Inverse Problems Involving Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaViola, J.; Kruijff, E.; McMahan, R.; Bowman, D.; Poupyrev, I. 3D User Interfaces: Theory and Practice, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y. Foveated Rendering: A State-of-the-art Survey. Comput. Vis. Media 2023, 9, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanto, B.; Subramanyam, A.V.; Hassan, E.A. An Integrative View of Foveated Rendering. Comput. Graph. 2022, 102, 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, C.; Howlett, S.; McDonnell, R.; Morvan, Y.; O’Conor, K. Perceptually Adaptive Graphics. In Eurographics 2004—State of the Art Reports (STARs); Schlick, C., Purgathofer, W., Eds.; Eurographics Association: Aire-la-Ville, Switzerland, 2004; pp. 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weier, M.; Zender, H.; Wimmer, M. A Survey of Foveated Rendering. Comput. Graph. 2015, 53, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberly, D.H. Game Physics, 2nd ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]