Abstract

Semantic segmentation of crowdsourced street-level imagery plays a critical role in urban analytics by enabling pixel-wise understanding of urban scenes for applications such as walkability scoring, environmental comfort evaluation, and urban planning, where robustness to geometric transformations and projection-induced symmetry variations is essential. This study presents a comparative evaluation of two primary families of semantic segmentation models: transformer-based models (SegFormer and Mask2Former) and prompt-based models (CLIPSeg, LangSAM, and SAM+CLIP). The evaluation is conducted on images with varying geometric properties, including normal perspective, fisheye distortion, and panoramic format, representing different forms of projection symmetry and symmetry-breaking transformations, using data from Google Street View and Mapillary. Each model is evaluated on a unified benchmark with pixel-level annotations for key urban classes, including road, building, sky, vegetation, and additional elements grouped under the “Other” class. Segmentation performance is assessed through metric-based, statistical, and visual evaluations, with mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) and pixel accuracy serving as the primary metrics. Results show that LangSAM demonstrates strong robustness across different image formats, with mIoU scores of 64.48% on fisheye images, 85.78% on normal perspective images, and 96.07% on panoramic images, indicating strong semantic consistency under projection-induced symmetry variations. Among transformer-based models, SegFormer proves to be the most reliable, attains higher accuracy on fisheye and normal perspective images among all models, with mean IoU scores of 72.21%, 94.92%, and 75.13% on fisheye, normal, and panoramic imagery, respectively. LangSAM not only demonstrates robustness across different projection geometries but also delivers the lowest segmentation error, consistently identifying the correct class for corresponding objects. In contrast, CLIPSeg remains the weakest prompt-based model, with mIoU scores of 77.60% on normal images, 59.33% on panoramic images, and a substantial drop to 59.33% on fisheye imagery, reflecting sensitivity to projection-related symmetry distortions.

1. Introduction

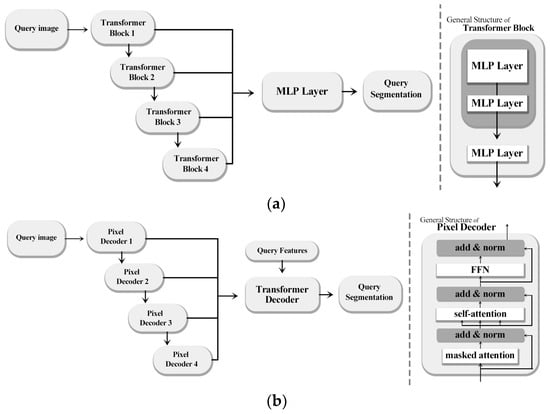

Semantic segmentation of street-level imagery enables detailed urban scene analysis by assigning a semantic label to each pixel [1]. This capability is fundamental for urban analytics applications such as walkability assessment, environmental comfort evaluation, and streetscape analysis. Prompt-based adaptation techniques [2] have emerged as a way to efficiently transfer knowledge across different domains and tasks, reducing the need for extensive retraining. In parallel, foundation models [3], which are large-scale pretrained models designed to be adaptable to multiple downstream applications, provide a unifying paradigm for leveraging vast amounts of data. While foundation models and transformer-based models are not equivalent concepts, transformer architectures frequently serve as the backbone of foundation models due to their scalability and strong generalization capacity. In urban scene understanding, transformer-based models such as SegFormer and Mask2Former have demonstrated strong performance on structured datasets. A variety of architectures, from fully convolutional networks to high-resolution refinement strategies, have been explored for urban scene segmentation [4,5]. Transformer-based architectures (Figure 1) such as SegFormer, further demonstrate strong performance in parsing street scenes [6]. Moreover, segmentation outputs are now used to quantify urban environmental factors like green space visibility, underscoring their broad utility [7]. Also, they represent new advances, enabling deployment in diverse domains from medical imaging to urban analytics (e.g., greenness and walkability indices) [7,8,9]. Despite these advances, semantic segmentation of crowdsourced street-level imagery from platforms such as Google Street View (GSV) and Mapillary remains challenging due to uncontrolled acquisition conditions and heterogeneous image geometries. These photos often vary widely in geometry (e.g., normal, fisheye, panoramic) and in conditions (e.g., illumination, weather), leading to occlusions, severe lens distortions, and inconsistent lighting [8]. These inconsistencies can degrade segmentation quality and thus affect higher-level tasks that rely on visual features, such as correlating streetscape appearance with housing values [8] or computing automated walkability scores [9]. To tackle geometric distortions, specialized data augmentation and calibration techniques have been proposed for fisheye and wide-FOV (Field of View) imagery [10,11]. By incorporating an additional, capable transformer-based model, we can gain deeper insights into the advantages and limitations of these architectures for image semantic segmentation (Table 1). Mask2Former builds upon this by introducing a unified mask-classification framework capable of handling semantic, instance, and panoptic segmentation within a single architecture [10] (Figure 1b). Its mask-level query representation and multi-scale attention design make it highly adaptable to diverse image sources, including heterogeneous crowd-sourced datasets with varying resolutions, lighting, and viewpoints. Testing Mask2Former alongside SegFormer on such imagery allows for evaluating trade-offs between SegFormer’s efficiency-oriented design and Mask2Former’s broader generalization capacity, potentially yielding complementary strengths in challenging real-world urban scenes. Meanwhile, large-scale datasets such as Mapillary Vistas provide diverse street scenes across different climates, times, and camera types to help models generalize [12]. Early approaches even leveraged multiple viewpoints of the same street scene to improve segmentation robustness [13]. Furthermore, numerous recent studies and dissertations continue to advance semantic segmentation for street-level imagery, reflecting sustained research interest in this domain [14,15,16,17]. Even in disaster scenarios, street-view segmentation provides critical insights for damage assessment [18].

Figure 1.

(a) SegFormer and (b) Mask2Former: schematic representation of the general architecture of the models.

Table 1.

Contrasts transformer-based features with prompt-based features.

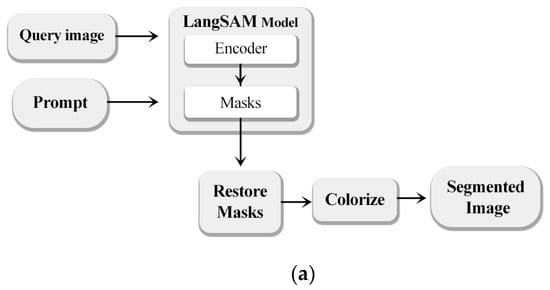

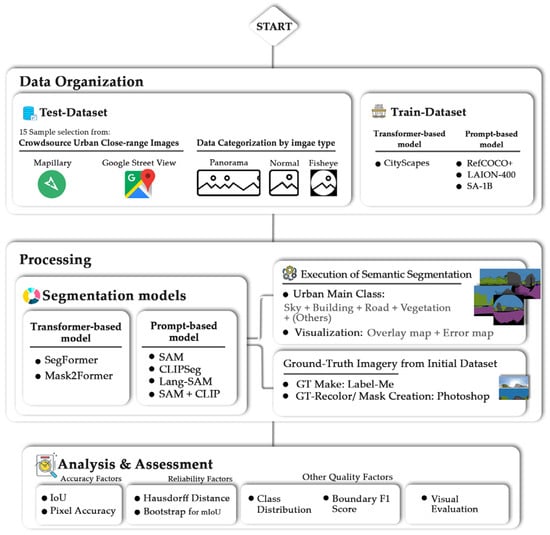

In this context, prompt-based models like CLIPSeg, LangSAM and SAM+CLIP (Figure 2) a fixed set of five textual prompts corresponding to the target classes (“road”, “building”, “sky”, “vegetation”, and “other”) was used consistently across all experiments, with prompt order kept constant to avoid bias, offer greater adaptability through textual guidance, while transformer-based models aim for high-resolution generalization across structured datasets, thus warranting a comparative evaluation across varied urban imagery. Prompt-based segmentation models represent a significant shift from traditional architectures by allowing semantic interpretation through natural language input, rather than relying on fixed, pre-defined label sets (Table 1, Figure 2). These models, such as CLIPSeg, LangSAM, and SAM+CLIP, integrate vision-language pretraining with zero-shot or few-shot segmentation capabilities [3].

Figure 2.

(a) LangSAM, (b) CLIPSeg and (c) SAM+CLIP: schematic representation of the general architecture of the models.

By aligning textual prompts with visual features (Figure 2), they enable dynamic, context-aware segmentation that adapts to user-defined categories at inference time.

This paradigm eliminates the need for retraining when new semantic classes are introduced, which contrasts sharply with earlier CNN or transformer-based models that depend on extensive supervised datasets. For instance, CLIPSeg employs the CLIP encoder to generate language-guided pixel-level predictions in a single forward pass, making it computationally efficient and ideal for low-resource applications [3]. LangSAM combines the grounding precision of GroundingDINO with the fine segmentation capacity of SAM, forming a two-stage pipeline that supports dense object localization even in cluttered urban environments. SAM+CLIP further enhances semantic alignment by classifying masks generated by SAM using textual embeddings from CLIP, enabling high-fidelity label assignment. These innovations have redefined segmentation workflows by decoupling class learning from training and allowing direct human-in-the-loop control. As a result, prompt-based models are increasingly adopted in fields requiring high adaptability and rapid deployment, including medical diagnostics [2], multi-organ 3D segmentation [3], and urban scene understanding. In the context of street-level imagery, their ability to generalize across diverse geometries and lighting conditions makes them promising tools for dynamic urban analysis.

Geometric Symmetry Variations in Street-Level Imagery

From a geometric perspective, street-level images acquired under different camera models exhibit distinct symmetry properties that directly influence semantic segmentation performance. Normal perspective images approximately preserve projective and translational symmetries, enabling relatively consistent spatial relationships between objects. In contrast, panoramic images introduce cylindrical projections with horizontal rotational symmetry, causing object elongation and non-uniform spatial scaling. Fisheye images exhibit strong radial symmetry combined with severe non-linear distortion, resulting in symmetry-breaking effects such as spatial compression near image borders and distortion of object boundaries. These projection-induced geometric symmetry variations alter spatial correspondence, disrupt attention mechanisms, and challenge feature consistency in segmentation models. Consequently, evaluating semantic segmentation performance across normal, panoramic, and fisheye imagery provides a geometry-aware assessment of model robustness under symmetry-preserving and symmetry-breaking transformations.

These challenges highlight a gap in systematic evaluations that jointly analyze transformer-based and prompt-based segmentation models under different projection geometries. This study addresses this gap by providing a comparative assessment across normal, fisheye, and panoramic street-level imagery. Specifically, we compare prompt-based segmentation models with two state-of-the-art transformer architectures: SegFormer and Mask2Former. The SegFormer (https://huggingface.co/nvidia/segformer-b5-finetuned-cityscapes-1024-1024 (accessed on 11 November 2025)) and Mask2Former (https://huggingface.co/facebook/mask2former-swin-large-cityscapes-semantic (accessed on 11 November 2025)) models, both pre-trained on the Cityscapes dataset, represent two distinct yet complementary paradigms in semantic segmentation and were evaluated in inference-only mode without additional fine-tuning to ensure a fair comparison with zero-shot prompt-based models. SegFormer offers enhanced scalability and rapid inference, making it efficient for large-scale deployments, while Mask2Former provides a unified transformer-based framework capable of producing high-quality, detailed segmentation outputs. In our evaluation, we subject these models to normal, fisheye, and panoramic imagery sourced from GSV and Mapillary, thereby capturing the diverse geometrical distortions and environmental variations inherent to complex urban scenes. This enables a robust assessment of how each architecture generalizes across different projection types and visual conditions. Our method follows a rigorous metric evaluation protocol, incorporating both accuracy-oriented and correctness-oriented parameters. Specifically, we employ Intersection over Union (IoU) and pixel accuracy to comprehensively capture different aspects of segmentation reliability and correctness, both in relative (model-to-model comparison) and absolute (alignment with ground truth) terms [1]. This dual perspective ensures that performance is not only measured in terms of aggregate accuracy but also in its capacity to correctly segment fine-grained and structurally complex elements. The comparative analysis yields valuable insights into the trade-offs between prompt-based segmentation and transformer-based segmentation frameworks. Transformer-based models exhibit consistent, high-resolution generalization across domains, demonstrating robustness to environmental variability and image distortions. Conversely, prompt-based models deliver flexible, language-guided segmentation capabilities without the need for retraining, making them particularly well-suited for dynamic urban environments where semantic targets may shift over time.

Beyond a direct empirical comparison, this study aims to conceptually position prompt-based and transformer-based segmentation frameworks within the broader landscape of vision foundation models for urban analysis. Unlike prior work that primarily emphasizes architectural modifications, fine-tuning strategies, or parameter-efficient adaptations, we focus on the interaction between model paradigm and image acquisition geometry. By systematically evaluating model behavior across normal, fisheye, and panorama projections, our analysis highlights how language-guided segmentation and fully supervised transformer-based approaches differ in their sensitivity to geometric distortions and uncontrolled acquisition conditions. This geometry-aware perspective provides methodological insights into the robustness and practical deployment of foundation-model-driven segmentation pipelines in real-world, crowdsourced urban environments. In contrast to existing studies that primarily focus on architectural extensions, fine-tuning strategies, or prompt optimization for foundation models, this work makes three distinct contributions. First, we provide a geometry-aware evaluation of both prompt-based and transformer-based segmentation paradigms under heterogeneous projection models, including normal, fisheye, and panoramic imagery. Second, we systematically analyze how language-guided and fully supervised segmentation frameworks differ in robustness, boundary accuracy, and error behavior when exposed to severe geometric distortions commonly found in crowdsourced street-level data. Third, rather than proposing a new architecture, we offer methodological insights into the practical deployment limits and strengths of current vision foundation models for real-world urban analysis scenarios, where imaging conditions are uncontrolled and highly variable.

2. Materials and Methods

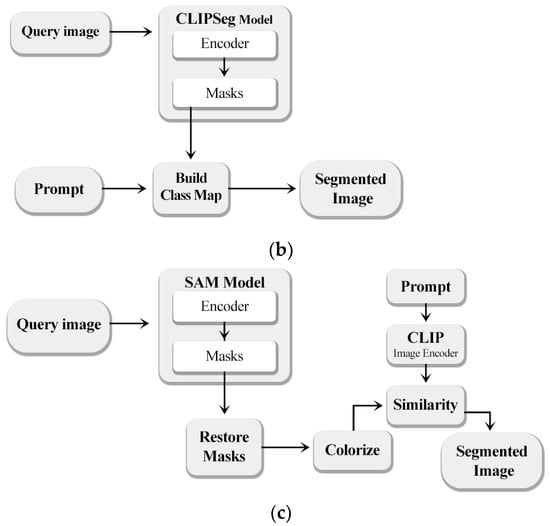

This research focuses on evaluating semantic segmentation in close-range imagery, considering the geometry and distortion of images (normal, fisheye, or panoramic). The study particularly examines the use of online imagery services, such as GSV and Mapillary, as crowdsourced imagery platforms that are freely accessible and available to users worldwide. In addition to a single individual sample used to test the performance of segmentation models, another 15 sample images were collected, comprising three types of images, which were classified during the processing stage using segmentation models (Figure 3). Multiple tests were conducted to assess visual challenges, including class distribution, segmentation accuracy, similarity between predicted and ground-truth segmentation boundaries, reliability and statistical assessment of the result and class imbalance. Visual mapping was also utilized to illustrate challenges in segmentation, such as variations in lighting conditions. The research flowchart, presented in Figure 3, outlines the milestones and details of the study.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the research.

2.1. Data Organization

2.1.1. Test Dataset

The dataset employed in this methodology comprises urban images captured at close range, with a particular emphasis on real-world challenges such as pedestrian occlusion, urban vegetation, and varying lighting conditions. The challenges associated with this endeavor are significant, but the availability of the dataset is crucial for assessing the adaptability of the models in various environments. While there are challenges related to obtaining permissions and data capture, the dataset offers the advantage of allowing for the use of any type of image, independent of geometry, data acquisition information, or view angle. This opportunity also facilitates a more comprehensive evaluation of the results, particularly in the context of the data capture or data organization section of the research, where parameters are achieved unconditionally. The collection contains a total of fifteen images, including five fisheye images, five panorama images, and five normal images. These images were obtained from two well-known online services: Mapillary and GSV Images. The majority of Mapillary’s content consists of Normal images, while GSV also offers Panorama and Fisheye images. To ensure a comprehensive sample, the Normal images were obtained from Mapillary, while the remaining two types were sourced from GSV. While the test set includes 15 images, our objective is not to establish large-scale generalization, but rather to evaluate the comparative and consistent segmentation behavior of LangSAM and SegFormer under controlled close-range urban scenarios. Each image represents a distinct scene with varying geometry, materials, and illumination conditions. Both models were evaluated on the same fixed dataset, ensuring a fair and direct comparison. Moreover, the observed consistency of performance across images suggests that the results are not driven by a small subset of samples. We acknowledge the limited dataset size as a limitation and plan to extend the evaluation to larger and more diverse datasets in future work.

2.1.2. Train Dataset

In the event that the primary training dataset is dominated by challenges related to illustration, such as shadows, the capacity for class identification can facilitate the research process. This capacity enables the independent evaluation of models with a heightened probability of correctness and accuracy. Cityscapes dataset, which consists of high-resolution urban scene images and includes 19 semantic classes. Cityscapes is a widely used benchmark dataset for training both transformer-based models. Both Transformer-based models utilized pre-trained weights on the Cityscapes dataset, were adapted to the task, and trained on the same subset of images to ensure fair and consistent evaluation.

The RefCOCO+ dataset, built on MS-COCO, provides images with referring expressions for urban semantic segmentation and is widely used to benchmark language-guided methods such as CLIPSeg and LangSAM [19]. The LAION-400M dataset, containing 400 million image–text pairs, serves as a large-scale pre-training source for CLIP model [20], which underpins approaches such as SAM+CLIP and CLIPSeg [21,22]. Finally, the SA-1B dataset, with over 1 billion marks on 11 million images, was created for training the SAM [23] and is leveraged by extended models including LangSAM and SAM+CLIP to ensure consistent and generalizable segmentation performance.

2.2. Processing

2.2.1. Segmentation Models

In this study, we adopt transformer-based and prompt-based semantic segmentation models, as these represent the most active and impactful trends [2,3,7,8].

We explored alternative approaches with functionalities as close as possible to DeepLabV3+, which has been widely adopted in numerous research studies [7,8]. Despite the efficiency of DeepLabV3+ in achieving robust semantic segmentation for urban scenes, we considered the importance of accessibility and availability of the processing model for a wider range of users. Therefore, SegFormer was selected as one of the alternative models to DeepLabV3+, as it is commonly employed for urban scene assessment tasks [6]. SegFormer, built on a transformer-based architecture rather than conventional convolutional neural networks, is fully open-source, freely available, and implemented in PyTorch (version 2.9). It demonstrates greater scalability, reduced complexity, and improved processing speed compared to DeepLabV3+. Another model considered in this research is Mask2Former, which also relies on a transformer-based architecture. Implemented in Python (version 3.14.2) and developed within the PyTorch framework [9], Mask2Former, like SegFormer, is free and open-source [6].

To ensure a fair comparison between both groups of models, the segmentation model was executed using personal computing resources equipped with 4 GB graphics card, 32 GB RAM, and a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-12650H processor. This approach enabled pixel-wise predictions, where each pixel was labeled according to the model’s interpretation of the class to which it belongs.

In addition to transformer-based approaches, we evaluated three prompt-driven segmentation pipelines, CLIPSeg, LangSAM and SAM+CLIP, to assess their flexibility and performance on crowdsourced street-view imagery. These models are particularly useful for adaptable, lightweight segmentation tasks where the class definitions are specified at runtime using natural language prompts. These models were applied in a zero-shot inference setting without retraining, following a standardized workflow consisting of prompt encoding, mask generation, mask–prompt matching, and class assignment based on maximum similarity. These models can adapt flexibly to new semantic categories using text prompts. CLIPSeg [24] is a single-step segmentation model that leverages the CLIP vision-language backbone to perform pixel-wise predictions based on free-form natural language prompts. Its simplicity, fast inference, and open-access implementation on HuggingFace make it an attractive option for urban applications with limited computational resources. LangSAM integrates the grounding capabilities of GroundingDINO with the segmentation strength of the Segment Anything Model (SAM) [23], offering a two-stage pipeline where prompt-based detection and mask generation are unified. It is particularly well-suited for dense and complex scenes such as street imagery, where object boundaries and overlapping instances must be resolved. The model is available through the LangSAM package and supports zero-shot inference with minimal setup. However, prompt order and overlap resolution are limitations that can affect prediction consistency. The third approach, SAM+CLIP, represents a hybrid model combining the generalization capacity of SAM with the semantic alignment of CLIP [20]. In this pipeline, masks generated by SAM are individually classified by comparing their visual features to CLIP’s textual embeddings, enabling label assignment via similarity matching. This modular structure allows for flexible integration with pre-existing prompt lists and improves semantic control. We compute a SAM-only coverage diagnostic: we take the union of all SAM masks and measure, both globally and per class, the fraction of ground-truth pixels that fall inside, irrespective of semantics [3]. We then use this measure to attribute residual errors—when coverage is high, remaining discrepancies are most plausibly due to the text-guided labeling stage CLIP rather than missed region proposals by SAM; when coverage is low, errors are more likely driven by proposal omissions.

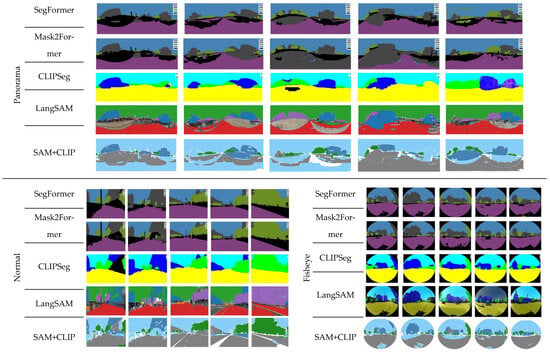

Across three types of images (normal, fisheye, and panoramic) semantic segmentation model assessment was conducted to analyze the test dataset, including 5 fisheye images, 5 panorama images and 5 normal images (Figure 4). The segmented areas were grouped into five primary classes: Sky, Building, Road, Vegetation, and Others, where the latter encompasses all objects in the scene not belonging to the four predefined categories. These classes are the major essential and influential elements for comfort assessment indicators [12,25]. All remaining pixels that do not belong to these primary classes are grouped under the “Others” category, which primarily includes heterogeneous minor urban objects such as vehicles, pedestrians, traffic signs, poles, and street furniture. For fisheye images, a binary template mask is applied prior to evaluation to restrict the analysis to the valid circular field of view. Pixels outside this region are excluded from all quantitative metrics. Within the valid region, the same four primary semantic classes are evaluated, while non-core pixels are consistently assigned to the “Others” category. Consequently, the “Others” class reflects segmentation behavior on heterogeneous minor objects within the valid image region, rather than errors originating from image borders or undefined areas.

Figure 4.

All 15 images used for segmentation model evaluation of both transformer-based and prompt-based models.

To ensure transparency and full reproducibility of the experimental setup, Table 2 presents a unified summary of all model-specific hyperparameters, training configurations, and prompt formulations used in this study. The table clearly distinguishes transformer-based models, which were fine-tuned using supervised learning, from prompt-based foundation models evaluated in a zero-shot inference setting. Consolidating these details into a single table enables consistent comparison across model families and facilitates faithful replication and future extension of the proposed experimental pipeline.

Table 2.

All model-specific hyperparameters, prompt configurations, and training settings used in the study. Transformer-based models were fine-tuned under supervised learning, while prompt-based foundation models were evaluated in a zero-shot inference setting.

2.2.2. Execution of Semantic Segmentation

While CLIPSeg offers a lightweight and fast segmentation approach, LangSAM and SAM+CLIP demonstrate greater flexibility and robustness, particularly under distorted input geometries. Their ability to generalize without explicit class retraining makes them especially suitable for dynamic and diverse urban data sources such as Mapillary and GSV [18]. Nonetheless, prompt-based models also face challenges, including inconsistent label resolution in overlapping regions, sensitivity to prompt phrasing, and computational costs in multi-stage pipelines. Further research is needed to enhance prompt sensitivity and contextual awareness in such models for large-scale urban analytics [2].

2.2.3. Ground-Truth Imagery from Initial Dataset

Ground-truth segmentation masks were generated through a semi-automatic, human-in-the-loop annotation workflow using the LabelMe AI tool, followed by systematic manual refinement and class-wise color correction in Adobe Photoshop to ensure pixel-level accuracy and consistency. The annotation process began with defining a fixed set of semantic classes (road, building, vegetation, sky, and others) within LabelMe AI, after which region-growing suggestions were generated and manually refined by an experienced operator to correct boundary inaccuracies, resolve class ambiguities, and eliminate misclassified regions.

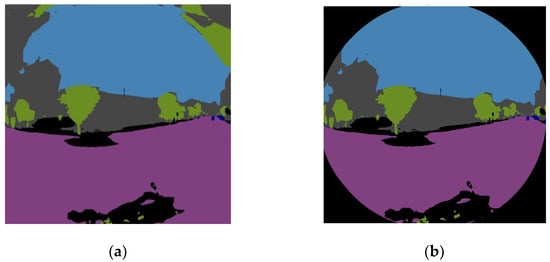

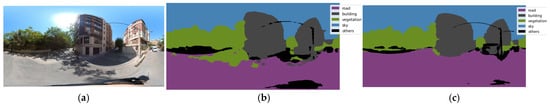

For fisheye imagery, an additional binary border mask was manually created to exclude non-informative regions caused by radial lens distortion and empty image borders, preventing these areas from influencing both model prediction and quantitative evaluation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The use of a mask is necessary to prevent model misclassification in fisheye images. As shown in (a), the fisheye image without a mask results in incorrect segmentation, whereas in (b), applying the mask ensures that the image borders remain unchanged.

All segmentation masks were visually inspected and iteratively corrected to ensure alignment with visible object boundaries, with particular attention paid to thin structures, occluded regions, and class transitions (e.g., vegetation–building interfaces), thereby minimizing annotation noise. Following segmentation, the masks were imported into Adobe Photoshop, where standardized RGB color codes were assigned to each semantic class to ensure consistent label encoding across all ground-truth images and compatibility with the evaluation pipeline. This structured annotation protocol ensures reproducibility by clearly defining class labels, annotation tools, human intervention steps, and post-processing procedures applied uniformly across all ground-truth images.

2.3. Analysis & Assessment

2.3.1. Accuracy Factors

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of semantic segmentation models, a combination of classical and advanced metrics was employed. These include pixel-level accuracy, Intersection-over-Union (IoU), and mean IoU (mIoU), which are standard in the semantic segmentation literature. Multiple complementary evaluation metrics were employed to capture different aspects of segmentation performance. Pixel accuracy provides a global measure of label correctness but is sensitive to class imbalance. Intersection over Union (IoU) offers a region-based evaluation that penalizes both over- and under-segmentation. IoU is computed on a per-class basis to measure the overlap between predicted and ground-truth regions (Formula (1)).

True Positive (TP) refers to the number of pixels correctly predicted as belonging to a specific class. False Positive (FP) represents pixels that are incorrectly predicted as part of a class but do not actually belong to it in the ground truth. False Negative (FN) denotes pixels that truly belong to a class but are not predicted as such by the model, indicating missed detections. mIoU summarizes this performance across all classes, providing both detailed and holistic insights into each model’s strengths and weaknesses (Formula (2)).

N denotes the total number of classes in the dataset, while IoUᵢ represents the Intersection over Union value calculated for each individual class (i).

Pixel accuracy is among the most fundamental and widely reported metrics in semantic segmentation, providing a direct measure of the proportion of correctly classified pixels. While simple, it serves as a baseline metric for model evaluation and comparison. Its strength lies in its ease of computation and interpretability, though it may be biased toward majority classes in imbalanced datasets. Pixel accuracy is mathematically defined as (Formula (3)):

where , and denote true positives, false positives, and false negatives across all classes. Higher values of PA indicate better global segmentation accuracy [5].

2.3.2. Reliability Factors

The Hausdorff distance (HD) provides a geometric measure of similarity between two sets of points, making it a powerful tool for assessing the closeness of predicted and ground-truth segmentation boundaries. Unlike overlap-based metrics such as IoU and average boundary measures such as Boundary F1, HD captures the maximum deviation between predicted and reference boundaries, highlighting the worst-case boundary error. While Boundary F1 complements region-based metrics by explicitly evaluating contour alignment, it remains less sensitive to isolated outliers than Hausdorff distance. This property makes HD particularly suitable for identifying localized but severe geometric errors, which are common in fisheye and panoramic imagery and may not significantly affect region-based accuracy. The directed Hausdorff distance between sets A (prediction) and B (ground truth) is defined as (Formula (4)):

where ‖⋅‖ denotes the Euclidean norm. Lower HD values indicate closer boundary alignment.

To account for confidence estimation in Intersection-over-Union (IoU) scores, bootstrap resampling techniques are applied. This approach enables statistical characterization of IoU distributions by repeatedly sampling with replacement from the test set and computing IoU across resamples. The bootstrap of IoU thus provides confidence intervals and variance estimates, ensuring reliable conclusions about model generalization. Formally, the bootstrap estimate of IoU for BBB resamples is given as (Formula (5)):

where denotes the IoU computed on the b-th bootstrap resample. Confidence intervals are derived from the empirical distribution of the bootstrap estimates. All confidence intervals reported in this study correspond to a 95% confidence level.

2.3.3. Other Quality Factors

Semantic segmentation tasks often require not only region-based accuracy but also precise delineation of object boundaries. The Boundary F1 Score (BF score) measures the alignment between predicted and ground-truth contours, capturing boundary-level fidelity that pixel accuracy alone cannot reflect. This is particularly valuable in high-resolution applications such as medical imaging and autonomous driving, where misaligned boundaries can lead to critical errors. The metric is calculated as the harmonic mean of boundary precision () and recall () within a specified tolerance band around ground-truth edges (Formula (6)):

where and , with representing true, false, and missed boundary pixels, respectively [16].

3. Results

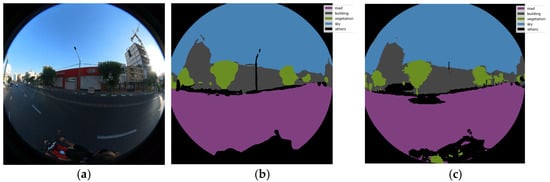

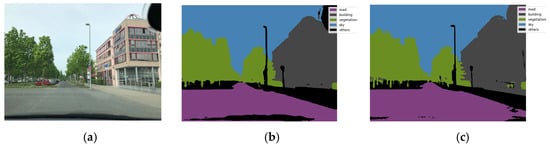

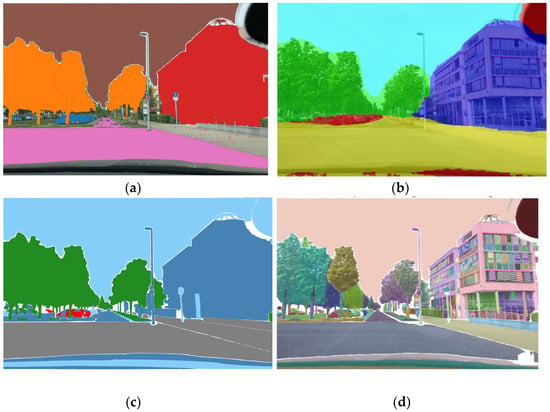

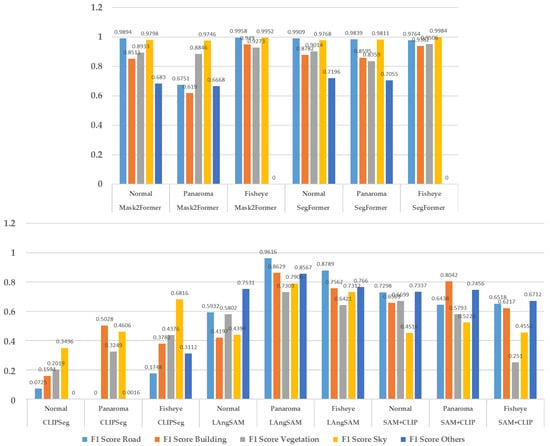

This research examines the performance and limitations of two recent semantic segmentation model groups using close-range urban imagery. Each model offers unique advantages: SegFormer from efficient transformer-based architecture, and Mask2Former from unified handling of multiple segmentation types. LangSAM from natural language–guided mask selection, CLIPSeg from zero-shot segmentation via vision–language alignment, SAM+CLIP from combining robust mask proposals with semantic filtering. The results in the tables indicate that both transformer-based models consistently achieve high accuracy, F1 score, and IoU for dominant categories such as road and sky (Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). For example, in fisheye images (Figure 6, Table 3), Mask2Former reached an F1 score of 0.9831 for road and 0.9831 for sky, with IoU values exceeding 0.96 in both cases. Similarly, SegFormer maintained strong performance, with road IoU of 0.9386 and sky IoU of 0.9328. These metrics highlight the robustness and accuracy of transformer-based encoders in capturing large-scale structures and consistent patterns across images.

Figure 6.

Semantic segmentation of an individual sample fisheye image, using Transformer-based model: (a) original image, (b) Mask2Former and (c) SegFormer-segmented image.

Figure 7.

Semantic segmentation of an individual sample normal image from mapillary service, using Transformer-based model: (a) original image, (b) Mask2Former and (c) SegFormer-segmented image.

Figure 8.

Semantic segmentation of an individual sample panorama image from GSV service, using Transformer-based model: (a) original image, (b) Mask2Former and (c) SegFormer-segmented image.

Table 3.

Quantitative evaluation of fisheye images using Mask2Former and SegFormer, including F1 score, IoU, pixel accuracy, and Hausdorff distance.

However, the distinction between the two models becomes evident when analyzing more complex or irregular classes such as building, vegetation, and others. Mask2Former typically outperformed SegFormer in these categories, particularly in fisheye and panoramic datasets. For example, vegetation segmentation under Mask2Former achieved F1 of 0.8288 in fisheye images, whereas SegFormer dropped slightly to 0.814. Likewise, for the “others” category, Mask2Former produced F1 of 0.8243 while SegFormer lagged at 0.7164. This reflects the advantage of Mask2Former’s unified architecture, which integrates instance-, semantic-, and panoptic-segmentation strategies, enabling it to better handle heterogeneous and irregular object categories. Nevertheless, performance differences are context-dependent. In some panorama cases, SegFormer occasionally surpassed Mask2Former, especially in “road” segmentation, where its F1 was 0.9387 compared to Mask2Former’s 0.8905. The Hausdorff distance analysis also indicates nuanced trade-offs. Mask2Former occasionally produced larger distance errors (e.g., 1654 in fisheye), reflecting inconsistencies in boundary adherence, whereas SegFormer yielded smaller values (e.g., 658.44 in the same dataset), suggesting slightly sharper boundary predictions in certain conditions. These findings reveal that while both transformer models excel in structured environments, their performance can diverge based on class complexity, boundary quality, and image type. SegFormer demonstrates slightly higher boundary adherence and more stable performance, reflected in its reduced variability across different test images. This suggests that SegFormer handles spatial variability and object class imbalances more effectively in standard perspectives compared to Mask2Former. In panoramic image segmentation, both models show the largest performance degradation, indicating that wide field-of-view and geometric distortions significantly challenge the segmentation task.

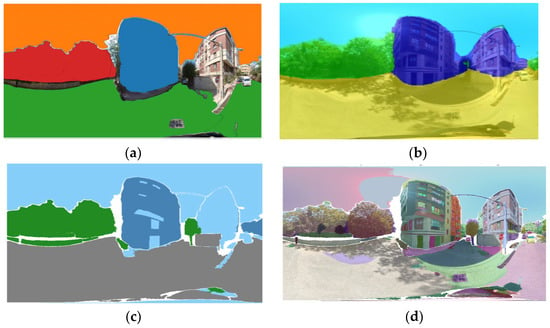

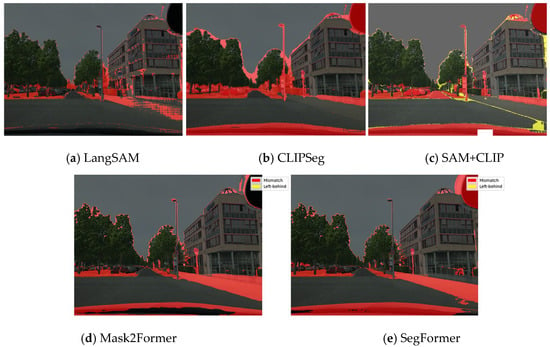

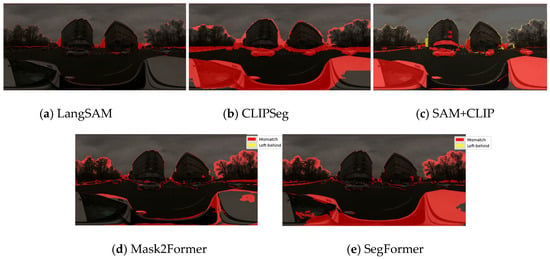

Prompt-based segmentation models (Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11) represent a different paradigm by allowing segmentation to be guided via text or point/box prompts. Their performance demonstrates unique advantages in adaptability but also exposes inefficiencies in precision compared to transformer-based approaches.

Figure 9.

Semantic segmentation of an individual sample normal image from mapillary service, using prompt-based model: (a) LangSAM, (b) CLIPSeg, (c) SAM+CLIP, (d) SAM segmented image. The original image is the same as that used in Figure 6.

Figure 10.

Semantic segmentation of an individual sample panorama image from mapillary service, using prompt-based model: (a) LangSAM, (b) CLIPSeg, (c) SAM+CLIP, (d) SAM segmented image. The original image is the same as that used in Figure 7.

Figure 11.

Semantic segmentation of an individual sample fisheye image from mapillary service, using prompt-based model: (a) LangSAM, (b) CLIPSeg, (c) SAM+CLIP, (d) SAM segmented image. The original image is the same as that used in Figure 5.

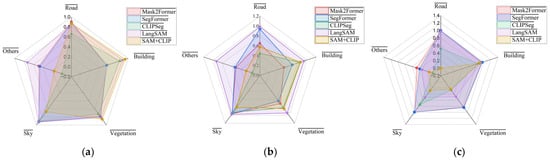

LangSAM generally provided the most balanced outcomes among the prompt-based group. For example, in panoramic scenes, LangSAM achieved F1 scores above 80% for road and sky, with IoU values exceeding 93% in several cases. Its ability to incorporate natural language prompts allowed it to adapt flexibly across categories, producing competitive accuracy, especially for dominant regions like sky (97.56% IoU). However, LangSAM also displayed inconsistency in fine-grained categories such as “building” or “others,” where F1 occasionally fell below 61%. CLIPSeg, relying on vision–language alignment without extensive fine-tuning, showed the weakest overall segmentation performance. Its F1 scores for road were often below 13%, and for “others”, the model failed entirely, producing zeros across F1, IoU, and accuracy. This underlines the limitation of purely zero-shot vision–language methods when precise pixel-level delineation is required. While CLIPSeg excelled in aligning global semantics with textual prompts, its segmentation lacked the structural precision needed for dense prediction tasks. SAM+CLIP, integrating the strong mask proposals from SAM with CLIP’s semantic filtering, demonstrated improved performance over CLIPSeg but remained inconsistent across categories. In normal images, SAM+CLIP achieved road accuracy of 98.86% and vegetation accuracy of 89.67%, reflecting its capacity to refine SAM’s general masks into semantically meaningful outputs. Nevertheless, it also suffered from low scores in ambiguous categories such as “others,” where F1 sometimes dropped to 73.37% but IoU was only 15.63%, indicating semantic mismatches. The base SAM performed reasonably well, consistently producing high-quality masks when provided with point or box prompts. For example, in panoramic images, SAM yielded sky IoU of 80.84% and accuracy exceeding 99%, which was comparable to transformer-based results. However, SAM’s reliance on explicit prompts limited its adaptability in automatic large-scale settings. Without carefully chosen prompts, its segmentation of non-dominant classes was often incomplete or imprecise. When comparing the two groups, clear distinctions emerge. Transformer-based models dominate in terms of consistent accuracy, IoU, and F1 scores across structured datasets. Their end-to-end training and learned attention mechanisms enable them to generalize reliably across all classes, including ambiguous ones. Conversely, prompt-based models excel in flexibility and adaptability, allowing interactive or language-driven segmentation but at the cost of statistical reliability in quantitative evaluations. The radar charts (Figure 12 and Figure 13) provide a multi-metric visualization of IIOUI (IoU) performance across segmentation classes for different image projection types. The results indicate that normal images achieve more consistent IoU across classes, suggesting that the geometric distortions introduced by panoramic and fisheye lenses significantly affect the spatial alignment between predicted and ground truth masks. Panoramic projections display moderate IoU reduction, likely due to stretching artifacts at the poles, whereas fisheye images exhibit performance variability, which can be attributed to severe radial distortion and reduced effective resolution in peripheral regions. These findings align with recent studies demonstrating that non-linear projection transformations challenge convolution-based architectures and require specialized distortion-aware training strategies [26].

Figure 12.

Radar charts illustrating the IoU parameters for the test dataset across three image types: (a) Normal, (b) Panorama, and (c) Fisheye.

Figure 13.

Radar charts illustrating the Pixel Accuracy parameters for the test dataset across three image types: (a) Normal, (b) Panorama, and (c) Fisheye.

The radar charts (Figure 12 and Figure 13) provide a comparative visualization of class-wise IoU and pixel accuracy across different image projection types. Normal perspective images exhibit the most balanced and stable performance across all semantic classes, indicating minimal geometric distortion effects. These trends demonstrate that segmentation robustness is strongly influenced by image geometry. Models trained primarily on perspective imagery generalize best to normal projections, while performance degradation in fisheye and panoramic views highlights the need for distortion-aware training strategies.

Pixel accuracy trends mirror IoU behavior but exhibit less sensitivity to class imbalance (Figure 12 and Figure 13). While fisheye images still underperform in certain classes, the overall accuracy remains higher compared to IoU due to the dominance of background pixels. This reinforces the notion that pixel accuracy can be less informative in scenarios with strong foreground–background imbalance [27]. The relatively stable accuracy in panoramic images suggests that, while geometric deformation affects precise boundary delineation (captured by IoU), pixel-level classification remains robust to some degree. Incorporating class-weighted accuracy or per-class recall could yield a more nuanced evaluation of segmentation in these distorted domains.

Overall, the evaluation reveals that LangSAM consistently delivers the highest segmentation performance across all image types, benefiting from its combined grounding and segmentation pipeline. CLIPSeg provides a fast and resource-efficient alternative with acceptable accuracy in normal views, while SAM+CLIP excels in certain semantic classes but remains highly sensitive to image geometry and initial mask quality. These findings reinforce the flexibility of prompt-based models and their growing applicability to real-world, variable street-view data, especially when robust prompt design and distortion-aware processing are considered.

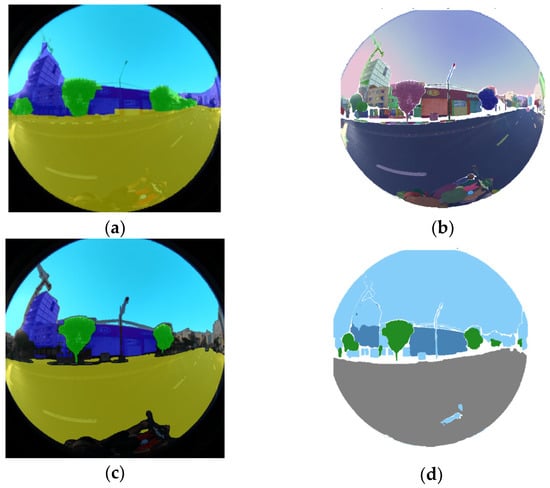

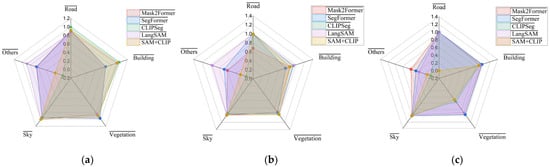

The comparative results highlight (Figure 14) that model performance is strongly dependent on both architecture and image projection type. Mask2Former and SegFormer maintain competitive performance across most conditions, indicating their robust transformer-based feature representation capabilities. LangSAM achieves the highest mIoU in panoramic images, suggesting that the integration of language-driven priors can improve semantic segmentation under distorted spatial layouts. Conversely, SAM+CLIP shows pronounced degradation in fisheye settings, possibly due to its reliance on high-level semantic alignment rather than geometric adaptability. This underscores the importance of incorporating distortion-invariant feature learning when addressing non-standard camera geometries. The quantitative results reveal several notable patterns (Table 4). LangSAM achieves the highest mIoU in panoramic settings (96.07%) and competitive accuracy (97.72%), demonstrating the effectiveness of multimodal priors in handling wide field-of-view distortions. Mask2Former and SegFormer exhibit balanced performance across image types, with SegFormer slightly outperforming Mask2Former in fisheye mIoU (94.92% vs. 94.23%). CLIPSeg performs well on normal images but suffers substantial mIoU degradation in panoramic and fisheye domains, reflecting its limited geometric adaptability. SAM+CLIP experiences the steepest performance drop in fisheye images (mIoU = 30.77%), highlighting a sensitivity to projection distortion. These results emphasize that distortion-aware training and domain adaptation remain critical for achieving consistent segmentation performance across varied image geometries [6,19].

Figure 14.

Bar chart showing the comparative evaluation of 5 segmentation models: Mask2Former, SegFormer, CLIPSeg, LangSAM, and SAM+CLIP on normal, panoramic, and fisheye street-view images, reported using the (a) mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) metric and (b) mean pixel accuracy.

Table 4.

Quantitative evaluation of normal images using Mask2Former and SegFormer, including F1 score, IoU, pixel accuracy, and Hausdorff distance.

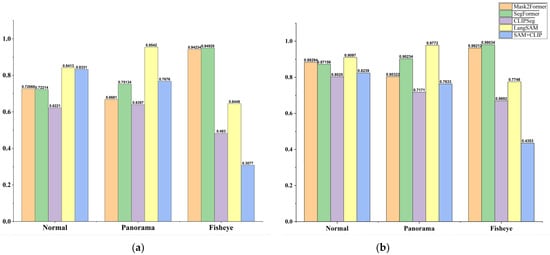

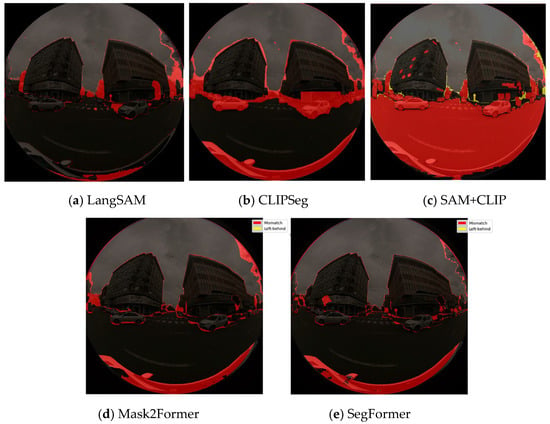

As demonstrated in Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17, the difference plot between the ground truth classes and the corresponding segmented ones provides a visual evaluation of the incorrect segmentation labels and classes. It should be noted that certain regions of the image have not been incorporated into any of the aforementioned classes. This may be indicative of a deficiency in the model’s functionality, specifically in regard to these specific areas. In general, the LangSAM model demonstrated a moderate degree of superiority in terms of its capacity to adequately encompass the designated class while effectively circumventing the presence of any unsegmented regions. It has been demonstrated that, in comparison with other prompt-based models, transformer-based models yield more accurate results. However, it should be noted that this is not the case for the model under consideration. Mask2Former identifies the border and distinguishes each class with a lower margin of error, with the exception of Fisheye images, for which SegFormer demonstrates a slightly higher degree of efficacy. It can be seen that only SAM+CLIP model left some unlabeled areas among all the models, and these features are all independent of image type and light condition of the scene. The F1 boundary scores (Figure 18) show that Mask2Former and SegFormer achieve the highest boundary precision (Figure 18), especially in fisheye and normal images, confirming their robustness in capturing fine contours. CLIPSeg performs weakest across all settings, while LangSAM leads among prompt-based models but remains below transformer-based approaches. Panoramic images consistently yield lower scores, highlighting the difficulty of maintaining boundary accuracy under geometric distortions.

Figure 15.

Difference maps between segmented fisheye images and their corresponding ground truth images: (a) LangSAM, (b) CLIPSeg, (c) SAM+CLIP, (d) Mask2Former, and (e) SegFormer. The maps highlight two types of mismatches: incorrect segmentation areas (red) and missed areas not included in the segmentation (yellow).

Figure 16.

Difference maps between segmented normal images and their corresponding ground truth images: (a) LangSAM, (b) CLIPSeg, (c) SAM+CLIP, (d) Mask2Former, and (e) SegFormer. The maps highlight two types of mismatches: incorrect segmentation areas (red) and missed areas not included in the segmentation (yellow).

Figure 17.

Difference maps between segmented panorama images and their corresponding ground truth images: (a) LangSAM, (b) CLIPSeg, (c) SAM+CLIP, (d) Mask2Former, and (e) SegFormer. The maps highlight two types of mismatches: incorrect segmentation areas (red) and missed areas not included in the segmentation (yellow).

Figure 18.

Boundary F1 score of each segmentation model demonstrating the significant power of transformer-based models.

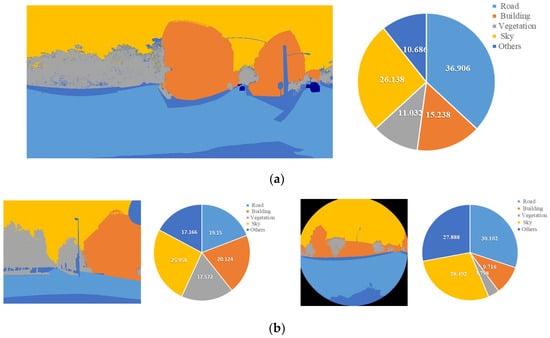

In panoramic images, small object classes often become elongated or fragmented, causing the IoU to decline more sharply than pixel accuracy. This reflects the inherent difficulty of preserving boundary precision across different spatial scales and highlights the critical role of class distribution in shaping accuracy metrics (Figure 19a). In contrast, normal images, with their narrower field of view, are less likely to include certain features such as “Others” class. As a result, the distribution of classes (Figure 19b) appears more balanced within the image; however, the reduced coverage of challenging classes plays a more decisive role in the performance outcomes. The main sources of error are closely tied to boundary irregularities, non-geometric object shapes, low contrast, and complex textures. This is particularly evident in the Vegetation and Building categories: the former is characterized by highly irregular and disconnected boundaries, while the latter contains complex textures and geometries, especially when compared to relatively homogeneous classes such as Sky and Road. These observations align with the results obtained for fisheye images, where the model achieved the highest accuracy scores, followed by the normal images.

Figure 19.

Mean Distribution of each class for each image type. The more a class covers, the more weight its accuracy parameters gain.

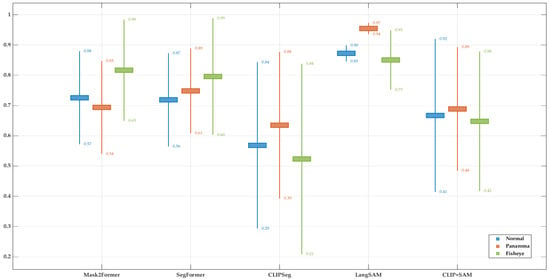

The bootstrap analysis of IoU demonstrated clear variability across models and image geometries. LangSAM exhibited the smallest confidence interval, indicating the reliability of its calculated IoU, and achieved the highest average IoU values, reflecting superior segmentation accuracy. However, this performance was moderately inconsistent across different image types. As shown in Figure 20, the panoramic case displayed a wider interval, and such variation was more evident among prompt-based approaches, whereas transformer-based models showed the opposite trend, maintaining significantly higher stability and reliability. Overall, we can claim that LangSAM achieved the highest reliability and accuracy of IoU, delivering the best results among both transformer-based and prompt-based models. This reliability, together with complementary accuracy checks, is further supported by the final stage of analysis, which examined boundary-level differences between models.

Figure 20.

Bootstrap-based 95% confidence intervals for mean IoU across models.

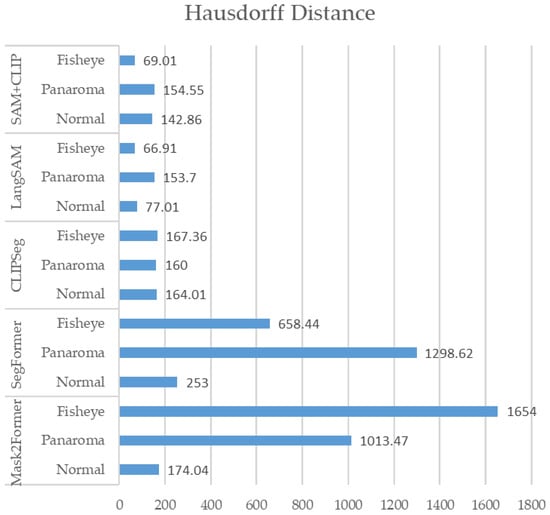

The Hausdorff Distance (HD) analysis (Figure 21) showed that Mask2Former achieved the lowest boundary error in normal imagery (174.0) but produced much higher values for fisheye (1654.0) and panoramic (1013.5) images, underlining the difficulty of maintaining contour accuracy under geometric distortion. SegFormer followed a similar trend, though with comparatively smaller errors for fisheye and panorama (658.4 and 1298.6, respectively). Among prompt-based approaches, LangSAM and SAM+CLIP consistently achieved lower HD values (e.g., 77.0–153.7 for LangSAM and 66.9–154.5 for SAM+CLIP), reflecting superior contour precision despite weaker region-overlap performance. Taken together, these findings suggest that transformer-based models provide stable segmentation overlap across geometries, while multimodal prompt-based approaches offer complementary advantages in boundary delineation under distortion.

Figure 21.

Hausdorff Distance analysis showed markedly higher boundary errors in fisheye and panorama projections.

The comparative evaluation demonstrates that transformer-based models, particularly Mask2Former and SegFormer, consistently outperform prompt-based approaches such as CLIPSeg, LangSAM, and SAM+CLIP across all image categories. Among them, Mask2Former applied to fisheye imagery achieves the highest performance with a mean IoU of 0.94234 and pixel accuracy of 0.96212, establishing it as the best-performing configuration overall. Conversely, CLIPSeg under fisheye conditions exhibits the lowest performance (mIoU = 56.37%), confirming its limited robustness to geometric distortion. Within Mask2Former, fisheye images yield the best segmentation outcomes, whereas panoramic inputs produce the weakest results, indicating sensitivity to projection-induced distortions. At the same time, LangSAM exhibits strong robustness across projection types, particularly excelling on panoramic imagery (IoU = 87.56%, 95.42%, and 86.94% for normal, panorama, and fisheye images, respectively), whereas SegFormer achieves higher mIoU scores on fisheye and normal perspective images. It delivers the lowest segmentation error, reliably identifies the correct class for the corresponding object, and demonstrates clear robustness across different projection types. While its performance is competitive with SegFormer among transformer-based models, LangSAM still achieves comparatively better results within the prompt-based category. In contrast, CLIPSeg remains the weakest performer overall.

4. Discussion

Based on the results obtained from single images across panoramic, fisheye, and normal formats, the initial findings provided a preliminary understanding of model performance. As presented in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8, Mask2Former achieved the best performance among transformer-based models, while LangSAM consistently outperformed other prompt-based models in terms of accuracy, robustness, and reliability. The accuracy values of Mask2Former and SegFormer were very close, with Mask2Former showing a slight overall advantage. However, while Mask2Former reached higher accuracy, LangSAM demonstrated stronger robustness and reliability, particularly under challenging conditions. This robustness was evident not only in pixel-level and boundary-based evaluations against ground truth data but also in additional tests (Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17) under limited illumination, where the superior reliability of prompt-based model was confirmed. To assess the reliability of the findings, the evaluation was extended to a larger and more diverse test set (Figure 4), covering variations in class distribution and illumination conditions. Under these expanded tests, LangSAM remained the most accurate prompt-based model, whereas CLIPSeg showed the weakest performance. The comparatively lower and less consistent performance of CLIPSeg across accuracy, IoU, and F1-based metrics reflects its single-stage prompt-to-pixel formulation, which is more sensitive to class imbalance and geometric distortions than multi-stage prompt-based pipelines such as LangSAM. Among transformer-based models, SegFormer generally outperformed its counterparts, as shown in Table 9 and Figure 12 and Figure 13. LangSAM and SegFormer achieved the best scores across pixel accuracy and mean Intersection over Union (IoU), consistently ranking first and second, even under low-light conditions. A more detailed inspection revealed that normal images yielded stable and reproducible segmentation results, maintaining the superiority of LangSAM and SegFormer. In contrast, fisheye and panoramic images, due to their unstable geometry and severe distortions, introduced variability into transformer-based models. While SegFormer often demonstrated higher accuracy, Mask2Former occasionally surpassed it in certain cases, suggesting localized improvements (Table 9, Normal image type; Table 3). Nevertheless, LangSAM consistently achieved the best results across all image types, confirming its robustness compared to transformer-based approaches. When considering per-class IoU distributions (Figure 19), the most frequently represented classes, namely Road, Sky, and Building, received greater weight in the evaluation. This analysis indicated that SegFormer continued to provide higher accuracy for these dominant classes. However, boundary-level assessments offered further insights. The Boundary F1 metric showed scattered segmentation errors for SegFormer, while Mask2Former demonstrated relatively greater stability, in some cases exceeding even LangSAM in boundary consistency. It should be noted that when the Hausdorff distance is very large but the Boundary F1 score remains high, the error is likely confined to a small localized region. In contrast, a low Boundary F1 score indicates that the predicted boundaries generally failed to follow the reference accurately [28,29,30,31,32,33]. Complementarily, the Hausdorff distance (Figure 21), a stricter measure that accounts for the worst-case boundary deviations, explained the observed fluctuations between Mask2Former and SegFormer as artifacts of severe distortions in fisheye imagery. Consequently, although SegFormer generally provided higher accuracy, its reliability was less stable, whereas prompt-based models showed more consistent boundary performance.

Table 5.

Quantitative evaluation of panorama images using Mask2Former and SegFormer, including F1 score, IoU, pixel accuracy, and Hausdorff distance.

Table 6.

Quantitative evaluation of normal images using LangSAM, CLIPSeg and SAM+CLIP models according to F1 score, IoU, pixel accuracy and Hausdorff Distance criteria.

Table 7.

Quantitative evaluation of panorama images using LangSAM, CLIPSeg and SAM+CLIP models according to F1 score, IoU, pixel accuracy and Hausdorff Distance criteria.

Table 8.

Quantitative evaluation of fisheye images using LangSAM, CLIPSeg and SAM+CLIP models according to F1 score, IoU, pixel accuracy and Hausdorff Distance criteria.

Table 9.

Comparative evaluation of 5 segmentation models, Mask2Former, SegFormer, CLIPSeg, LangSAM, and SAM+CLIP, on normal, panoramic, and fisheye street-view images, reported using the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) metric.

The observed performance degradation on panoramic and fisheye images can be attributed to the mismatch between training assumptions and projection geometry. Transformer-based models are predominantly trained on rectilinear imagery and rely on spatially consistent self-attention patterns, which are disrupted by severe distortions. In contrast, prompt-based models benefit from semantic grounding via language, making them less sensitive to projection-induced geometric variations. Recent studies exploring the geometric characteristics and calibration strategies of fisheye and panoramic imaging systems further emphasize that projection-specific distortions significantly affect visual representations, underscoring the importance of considering diverse image types when evaluating segmentation models [34,35]. While recent SAM- and CLIP-based studies emphasize architectural refinements or prompt optimization, our findings suggest that image acquisition geometry plays an equally critical role in determining segmentation reliability, particularly for crowdsourced urban imagery. From a broader foundation-model perspective, these findings indicate that robustness to image acquisition geometry constitutes a critical yet often underexplored dimension of segmentation performance. Prompt-based models benefit from semantic grounding through language, which appears less sensitive to geometric distortions than purely supervision-driven transformer architectures trained predominantly on rectilinear imagery. As a result, prompt-guided segmentation exhibits complementary strengths to transformer-based approaches, particularly in scenarios where camera calibration, projection geometry, and environmental conditions are uncontrolled. This observation suggests that evaluation protocols for vision foundation models should extend beyond standard accuracy metrics and consider geometry-induced reliability when targeting real-world urban applications.

Table 10 provides a concise comparative overview of the evaluated semantic segmentation models based on their final mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) scores across different image geometries, namely normal, fisheye, and panoramic views. The table complements the detailed quantitative and visual analyses by summarizing both numerical performance and qualitative behavior, including robustness to geometric distortion, boundary adherence, and class-level consistency. Overall, LangSAM emerges as the best-performing and most robust model across varying projections, while SegFormer demonstrates the strongest and most stable performance among transformer-based approaches. In contrast, CLIPSeg and SAM+CLIP show limited reliability under severe distortions, particularly in fisheye imagery, underscoring the importance of geometry-aware design for real-world urban scene segmentation.

Table 10.

Comparative summary of segmentation performance (mean Intersection over Union, mIoU) for transformer-based and prompt-based models across normal, fisheye, and panoramic street-level images, highlighting overall accuracy trends and qualitative performance characteristics.

Finally, to evaluate parameter stability, Bootstrap-derived IoU intervals (Figure 20) confirmed LangSAM as the most stable model, followed by SegFormer and Mask2Former with comparable robustness. Taken together, these results indicate that the comparative advantages of the models are projection-dependent: transformer-based models such as SegFormer perform more accurately on conventional and fisheye projections, while prompt-based LangSAM shows notable advantages on panoramic imagery.

5. Conclusions

The experimental analysis indicates that LangSAM achieves higher segmentation accuracy than other evaluated prompt-based and transformer-based models on the considered dataset, attaining an mIoU of 82.11% under the tested conditions. Among transformer-based approaches, SegFormer slightly outperforms Mask2Former, with mIoU scores of 80.75% and 77.90%, respectively. SegFormer also exhibits tighter bootstrap confidence intervals, suggesting more consistent performance across repeated runs within the experimental setting.

From these results, several observations can be drawn within the scope of the evaluated data. First, fisheye preprocessing leads to measurable improvements in segmentation performance compared to unprocessed fisheye inputs, while normal image views consistently yield higher accuracy and more stable predictions across all models. Within this context, LangSAM demonstrates comparatively stronger performance across the tested image types. Second, fisheye imagery remains the most challenging modality for all evaluated architectures, with Mask2Former and CLIPSeg showing larger performance degradation. This suggests that the evaluated models may benefit from additional adaptations, such as distortion-aware components, when handling strong geometric distortions. Third, while SegFormer occasionally achieves higher class-specific boundary precision, LangSAM produces more consistent results across image types in this dataset, particularly under distorted viewing conditions.

For fisheye images, the performance of both LangSAM and SegFormer declines relative to normal views. However, LangSAM maintains a marginally higher mIoU and improved boundary alignment in these cases, indicating greater resilience to spatial variability within the evaluated scenarios. This performance difference becomes more pronounced in panoramic images, where elongated object structures and wide field-of-view distortions pose additional challenges. Under these conditions, LangSAM achieves an mIoU of 96.07% compared to 75.13% for SegFormer, alongside narrower confidence intervals. While these results suggest improved adaptability to complex scene geometries within the dataset, further validation on larger and more diverse benchmarks would be required to confirm broader generalization.

Collectively, the findings support three dataset-specific insights: (1) fisheye imagery produces less stable segmentation outcomes compared to normal and panoramic views across all evaluated models; (2) fisheye images represent the most challenging input modality, motivating future exploration of distortion-aware and multi-scale methods; and (3) SegFormer and LangSAM both demonstrate relatively stable performance across input types, with LangSAM achieving higher average accuracy under the tested conditions. These results highlight LangSAM’s potential effectiveness for handling diverse camera geometries, though conclusions regarding real-world deployment should be drawn cautiously given the limited dataset.

The grounding-and-segmentation pipeline employed by LangSAM enables accurate localization of semantically relevant regions, resulting in high mean IoU scores for dominant classes such as sky, road, and vegetation, even under geometric distortion. CLIPSeg, while computationally efficient, exhibits lower segmentation accuracy across most classes and performs particularly weakly on normal-view images in categories such as sky and buildings. SAM+CLIP achieves strong semantic alignment for certain classes in normal views; however, its reliance on initial SAM mask quality leads to instability in distorted and wide-angle images, especially in fisheye scenarios.

Overall, these findings suggest that prompt-based segmentation approaches can serve as a flexible alternative to conventional architectures, although their effectiveness is closely tied to input geometry and prompt quality. Within the evaluated dataset, LangSAM demonstrates more consistent performance than CLIPSeg and SAM+CLIP, while SegFormer remains competitive in boundary-sensitive classes. However, the reliability and generalization of both prompt-driven and transformer-based models are strongly influenced by the diversity and representativeness of the training and evaluation data.

Current datasets remain limited in terms of cross-domain diversity, geometric variation, and challenging conditions such as shadows and extreme distortions. Future work should therefore prioritize the development of richer datasets that incorporate multi-scale, multi-modal imagery and prompt-specific annotations. Such datasets would enable more rigorous evaluation of models like LangSAM and support stronger conclusions regarding their generalization capabilities. Finally, the emphasis on shadow mitigation in this study highlights opportunities for future research in image translation and self-supervised shadow segmentation, which would benefit substantially from improved and more diverse training data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A.; methodology, H.A., A.Y. and S.R.; data collection, A.Y.; data analysis, S.R.; writing, original draft preparation, S.R. and A.Y.; writing—review and editing, A.Y.; visualization, S.R.; supervision, H.A.; project administration, H.A. and S.R.; funding acquisition, H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the i3mainz, Institute for Spatial Information and Surveying Technology, Mainz University of Applied Sciences. The authors greatly appreciate the financial support.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| mIoU | Mean Intersection over Union |

| F1 | F1 Score (harmonic mean of precision and recall) |

| BF Score | Boundary F1 Score |

| HD | Hausdorff Distance |

| TP | True Positive |

| FP | False Positive |

| FN | False Negative |

| PA | Pixel Accuracy |

| FOV | Field of View |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| SAM | Segment Anything Model |

| CLIP | Contrastive Language–Image Pretraining |

| GSV | Google Street View |

| ICCV | IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision |

| CVPR | IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition |

| LAION | Large-scale Artificial Intelligence Open Network |

| MS-COCO | Microsoft Common Objects in Context |

| RefCOCO+ | Referring Expressions COCO+ dataset |

References

- Hua, C.; Lv, W. Optimizing Semantic Segmentation of Street Views with SP-UNet for Comprehensive Street Quality Evaluation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Bai, L.; Yang, X.; Liang, J. Label-Semantic-Based Prompt Tuning for Vision Transformer Adaptation in Medical Image Analysis. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 10906–10917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Khanduri, P.; Qiang, Y.; Sultan, R.I.; Chetty, I.; Zhu, D. AutoProSAM: Automated Prompting SAM for 3D Multi-Organ Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 26 February–6 March 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankareddy, R.; Delhibabu, R. Dense Segmentation Techniques Using Deep Learning for Urban Scene Parsing: A Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 34496–34517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and Efficient Design for Semantic Segmentation with Transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wu, H.; Chen, P. An improved Deeplabv3+ semantic segmentation algorithm with multiple loss constraints. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Park, H.Y.; Lee, J. A Review on Recent Deep Learning-Based Semantic Segmentation for Urban Greenness Measurement. Sensors 2024, 24, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatius, M.; Lim, J.; Gottkehaskamp, B.; Fujiwara, K.; Miller, C.; Biljecki, F. Digital Twin and Wearables Unveiling Pedestrian Comfort Dynamics and Walkability in Cities. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, X-4/W5-2024, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Qi, Y.; Xiang, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. Mask2Former with Improved Query for Semantic Segmentation in Remote-Sensing Images. Mathematics 2024, 12, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasev, V.; Dimitrovski, I.; Chorbev, I.; Kitanovski, I. Semantic Segmentation of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing Images Using SegFormer. In Intelligent Systems and Pattern Recognition; Bennour, A., Bouridane, A., Almaadeed, S., Bouaziz, B., Edirisinghe, E., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Yin, Y.; Xue, Z.; Ma, D. Assessing and Comparing the Visual Comfort of Streets across Four Chinese Megacities Using AI-Based Image Analysis and the Perceptive Evaluation Method. Land 2023, 12, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheke, R.; Ganesh, S.; Eising, C.; van de Ven, P.; Kumar, V.R.; Yogamani, S. FisheyePixPro: Self-supervised pretraining using Fisheye images for semantic segmentation. Electron. Imaging 2022, 34, 147-1–147-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Jia, T.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Do street-level scene perceptions affect housing prices in Chinese megacities? An analysis using open access datasets and deep learning. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, S.; Nakaya, T.; Hanibuchi, T.; Amagasa, S.; Kikuchi, H.; Inoue, S. Objective scoring of streetscape walkability related to leisure walking: Statistical modeling approach with semantic segmentation of Google Street View images. Health Place 2020, 66, 102428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Yang, K.; Xiang, K.; Wang, J.; Wang, K. Universal Semantic Segmentation for Fisheye Urban Driving Images. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 11–14 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Hu, X.; Bergasa, L.M.; Romera, E.; Wang, K. PASS: Panoramic Annular Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 21, 4171–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhold, G.; Ollmann, T.; Bulo, S.R.; Kontschieder, P. The Mapillary Vistas Dataset for Semantic Understanding of Street Scenes. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 4990–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Belongie, S.; Koltun, V.; Ranftl, R. Language-driven Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.03546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual Event, 18–24 July 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüddecke, T.; Ecker, A.S. Image Segmentation Using Text and Image Prompts. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.-N.; Xiao, J.; Lu, Y.; Landman, B.A.; Yuan, Y.; Yuille, A.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, Z. CLIP-Driven Universal Model for Organ Segmentation and Tumor Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 21095–21107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.-Y.; et al. Segment Anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. Long Quan Multiple view semantic segmentation for street view images. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE 12th International Conference on Computer Vision, Kyoto, Japan, 29 September–2 October 2009; pp. 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhao, H.; Puig, X.; Fidler, S.; Barriuso, A.; Torralba, A. Scene Parsing through ADE20K Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 5122–5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-X.; Li, K.; Fu, Z.; Liu, M.; Chen, Z.; Guo, Y. Distortion-aware Monocular Depth Estimation for Omnidirectional Images. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2021, 28, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, M.; Van Gool, L.; Williams, C.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The Pascal Visual Object Classes (VOC) challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2010, 88, 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordts, M.; Omran, M.; Ramos, S.; Rehfeld, T.; Enzweiler, M.; Benenson, R.; Franke, U.; Roth, S.; Schiele, B. The Cityscapes Dataset for Semantic Urban Scene Understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaridis, C.; Wang, H.; Li, K.; Zurbrügg, R.; Jadon, A.; Abbeloos, W.; Reino, D.O.; Van Gool, L.; Dai, D. ACDC: The Adverse Conditions Dataset with Correspondences for Robust Semantic Driving Scene Perception. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2104.13395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaridis, C.; Dai, D.; Gool, L.V. Guided Curriculum Model Adaptation and Uncertainty-Aware Evaluation for Semantic Nighttime Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogamani, S.; Hughes, C.; Horgan, J.; Sistu, G.; Varley, P.; O’Dea, D.; Uricár, M.; Milz, S.; Simon, M.; Amende, K.; et al. WoodScape: A multi-task, multi-camera fisheye dataset for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, A.A.; Hanbury, A. Metrics for evaluating 3D medical image segmentation: Analysis, selection, and tool. BMC Med. Imaging 2015, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaus, A.; Seibold, C.; Reiß, S.; Marinov, Z.; Li, K.; Ye, Z.; Krieg, S.; Kleesiek, J.; Stiefelhagen, R. Every Component Counts: Rethinking the Measure of Success for Medical Semantic Segmentation in Multi-Instance Segmentation Tasks. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 3904–3912. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.18684 (accessed on 11 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.; Maier, A.; Arefi, H. Quality analysis of 3D point cloud using low-cost spherical camera for underpass mapping. Sensors 2024, 24, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, S.; Arefi, H. Evaluation of network design and solutions of fisheye camera calibration for 3D reconstruction. Sensors 2025, 25, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.