Abstract

Image watermarking is an essential technique for protecting the copyright of digital images. This paper proposes a novel color image watermarking algorithm based on the Walsh–Hadamard Transform (WHT). By analyzing the differences among WHT coefficients, an asymmetric embedding position selection strategy is designed to enhance the robustness of the algorithm. Specifically, the color image is first separated into red (R), green (G), and blue (B) channels, each of which is divided into non-overlapping 4 × 4 blocks. Then, suitable embedding regions are selected based on the entropy of each block. Finally, the optimal embedding positions are determined by comparing the differences between WHT coefficient pairs. To ensure watermark security, the watermark is encrypted using Logistic chaotic map prior to embedding. During the extraction phase, the watermark is recovered using the chaotic key and the pre-stored embedding position information. Extensive simulation experiments are conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm. The comparative results demonstrate that the proposed method maintains high imperceptibility while exhibiting superior robustness against various attacks, outperforming existing state-of-the-art approaches in overall performance.

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of the Internet, the transmission of digital media across networks has become widely adopted across various industries. During the process of network-based information transmission, preventing unauthorized access to protected content has become a critical and widely discussed issue [1]. Within the realm of intellectual property protection, cryptography, steganography, and digital watermarking are three widely adopted techniques for ensuring copyright authentication in digital media ecosystems [2,3,4]. Among these techniques, digital watermarking operates by embedding watermark information into digital media in a manner that ensures high imperceptibility to the human visual system [5]. After undergoing network transmission and potential processing distortions, the embedded watermark can still be reliably extracted and recognized, thereby enabling robust copyright protection of digital content [6].

In traditional digital watermarking techniques, methods are typically categorized into spatial-domain and frequency-domain approaches based on the embedding domain of the watermark [7,8]. Spatial-domain watermarking embeds watermark information by directly modifying the pixel values of the cover image [9]. This approach offers fast computation and low complexity but suffers from limited embedding capacity and poor robustness against common image processing attacks [10]. For instance, Li et al. [11] proposed a blind spatial-domain watermarking scheme where the host image is divided into blocks. By selecting blocks with lower standard deviations and further partitioning them into four sub-blocks, the watermark is embedded by adjusting the direct current coefficients of three selected sub-blocks. This method demonstrates significant advantages in imperceptibility compared to existing techniques. In contrast, frequency-domain watermarking involves transforming the cover image into the frequency domain and embedding the watermark within the transformed coefficients [12]. Although this technique significantly improves robustness, especially against compression and noise attacks, it typically incurs higher computational costs [13]. For instance, AbdElHaleem et al. [14] transformed images into the YCbCr color space and applied the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) and Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) to the Y channel for watermark embedding. The method also employs a fractional-order Lorenz system for watermark encryption, thereby enhancing the security of the watermarking scheme. Bounceu et al. [15] proposed a watermarking method that integrates DWT with Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) to enhance the robustness and stability of the embedded watermark. Experimental results indicate that the method achieves excellent imperceptibility, making it well-suited for medical image applications. Gao et al. [16] integrated the Integer Wavelet Transform (IWT) with Zernike Moments, extracting features from the IWT low-frequency sub-band to achieve high robustness against geometric transformations and common attacks.

Currently, deep learning-based watermarking algorithms are also very popular. Relying on the powerful feature extraction and fitting capabilities of deep learning, neural network watermarking algorithms demonstrate excellent performance in many scenarios. The research context of this field evolved from foundational end-to-end architectures to specialized cross-media applications. Zhu et al. [17] proposed the HiDDeN framework, which employed joint encoder–decoder training and introduced differentiable approximations of non-differentiable distortions like JPEG compression. To enhance the practicality of such models, Liu et al. [18] developed a two-stage separable deep learning framework, addressing the slow convergence and noise-simulation limitations of earlier one-stage end-to-end methods. As the field moved toward physical-world applications, Wengrowski and Dana [19] introduced Light Field Messaging to model the complex camera-display transfer function. Similarly, Tancik et al. [20] presented StegaStamp, which enables the robust encoding of hyperlinks into physical photographs by simulating a wide range of spatial and photometric distortions. More recently, to specifically counter the complex distortions of screen-shooting, Fang et al. [21] proposed PIMoG, which decomposes the noise layer into perspective, illumination, and moiré distortions, achieving superior extraction accuracy. Building upon these representative works, recent specialized innovations have further refined these mechanisms. Qiao et al. [22] proposed a Scalable Universal Adversarial watermark approach. By extending the defense range of pre-watermark mechanisms, their method effectively counters new forgery models while maintaining low computational costs. Wu et al. [23] developed a robust framework based on multi-layer watermark feature fusion. This architecture allows for arbitrary depthwise stacking to associate with watermarks, demonstrating superior invisibility and generalization capabilities, particularly in few-shot learning scenarios. Furthermore, deep learning methods have shown remarkable robustness against cross-media attacks, such as print-camera and screen-shooting processes, which are traditionally challenging. Qin et al. [24] designed a network architecture incorporating deep noise simulation and constrained learning, significantly reducing distortion and enhancing robustness against the print-camera channel. Similarly, targeting the screen-shooting resilience, Guo et al. [25] proposed a double-branch network. By assigning Gaussian-distributed weights to the encoder branches, their scheme achieves a balance between visual quality and robustness against screen-capture distortions. Cao et al. [26] proposed an end-to-end framework combining DCT-domain channel attention and adversarial training to resist screen-shooting attacks. By employing a training strategy based on Generative Adversarial Networks, their model effectively generates universal watermark masks that achieve a superior balance between imperceptibility and robustness. Although these neural network-based methods achieve excellent performance, they often require substantial computational resources, large training datasets, and long training times. In contrast, traditional methods, particularly those based on efficient transforms like WHT, offer the advantages of low complexity, blind extraction without training, and ease of hardware implementation. Therefore, optimizing traditional algorithms for specific application scenarios remains a valuable research direction.

With the rapid advancement of the multimedia big data era, color images have garnered increasing attention due to their large information capacity and superior visual quality [27,28,29]. These advantages have led to their widespread application in real-world scenarios. Over the past decades, most digital watermarking research has predominantly focused on traditional binary images [30] and grayscale images [31,32], with relatively limited attention given to dual color image watermarking. In recent years, research on dual color image watermarking, where both the cover image and the watermark are in color, has advanced significantly, leading to the development and recognition of numerous novel algorithms tailored for such scenarios. For instance, Su et al. [33] proposed a blind color image watermarking scheme that integrates a graph-based transform. The method leverages the structural properties of graphs to efficiently extract stable transform coefficients in the spatial domain and incorporates particle swarm optimization to adaptively optimize the embedding strength. Zhang et al. [34] proposed a blind color image watermarking algorithm based on dual quaternion QR decomposition. By introducing Arnold scrambling for watermark protection, the method combines dual quaternion matrix representation for color images and employs a dual-structure preservation algorithm to enhance computational efficiency. Wang et al. [28] proposed a watermarking algorithm based on the split quaternion matrix model, which effectively analyzes the complex spectral correlations among RGB channels in color images. The method is specifically optimized to address the inherent complexities of color image processing, demonstrating strong robustness and high perceptual quality.

In contemporary digital watermarking, WHT-based algorithms represent an important research direction. Numerous studies have explored various embedding strategies by exploiting the statistical and structural properties of WHT coefficients. Chen et al. [35] utilized the property that the first row of WHT coefficients concentrates the majority of energy, embedding watermark information into elements of that row. The embedding is achieved by adjusting specific coefficient pairs within the first row, and experimental results demonstrate strong robustness against common image processing operations. To reduce perceptual distortion caused by coefficient modification, Reddy et al. [36] proposed a strategy designed to minimize the range of coefficient perturbations. In this method, watermark bits are embedded into the first and second columns of WHT coefficients, effectively constraining the affected coefficient region. Experiments show that this method maintains good performance under median filtering, JPEG compression, and noise attacks. Unlike the above robustness-oriented approaches, Prabha et al. [37] focused on improving imperceptibility. Their algorithm embeds watermark information by slightly modifying the coefficients in the third and fourth rows, which are less perceptually sensitive, thereby achieving high visual quality after embedding. However, prioritizing imperceptibility inevitably leads to reduced robustness.

Imperceptibility and robustness are two fundamental performance metrics of digital watermarking systems [38]. However, this inherent trade-off dictates that enhancing imperceptibility typically compromises robustness, and vice versa. Striking an optimal balance between these competing requirements remains a pivotal challenge in contemporary digital watermarking research [39,40]. The choice of embedding regions within the cover image plays a crucial role in determining the overall performance of a watermarking system [41]. Embedding watermarks in high-texture regions enhances robustness against signal processing attacks, albeit often at the expense of visual imperceptibility. Conversely, embedding in smooth areas improves visual transparency but substantially reduces resilience to malicious manipulations [42]. This inherent trade-off has driven extensive research into adaptive region selection strategies aimed at optimizing the balance between imperceptibility and robustness. Kumari et al. [43] proposed a block selection strategy based on low variance values, where image blocks with minimal pixel variation are identified as suitable embedding regions. The selection is further optimized using an Enhanced Tunicate Swarm Algorithm, refined by the Sine Cosine Algorithm, to effectively locate blocks with the lowest variance and least visual complexity for watermark embedding.

The performance of digital watermarking techniques primarily depends on several key indicators, including imperceptibility, robustness, security, and embedding capacity. With the widespread use of color images, it has become increasingly important to design watermarking algorithms that can effectively process color images while maintaining both high imperceptibility and strong robustness.

To address this challenge, this paper proposes a novel watermarking algorithm. In the proposed method, the color image is first decomposed into its R, G, and B channels, each of which is further divided into non-overlapping 4 × 4 blocks. Candidate embedding blocks are then selected based on entropy calculations, followed by the application of the WHT to the selected blocks. Subsequently, the embedding and extraction of the color watermark are performed according to the differences between paired WHT coefficients in the frequency domain. This strategy fully exploits the energy compaction property of the WHT, embedding watermark information into the cover image by quantizing and adjusting the coefficient differences. As a result, the proposed method achieves a significant improvement in watermark robustness while ensuring imperceptibility to the human visual system.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- A WHT-based watermarking algorithm that achieves a superior balance between imperceptibility and robustness is proposed. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method exhibits good performance in both aspects. In particular, the algorithm consistently enables accurate watermark extraction under various attacks, outperforming state-of-the-art methods.

- An entropy-based block selection mechanism is employed to identify optimal regions for embedding, which enhances the imperceptibility of the watermarking algorithm. In addition, the watermark image is encrypted using the Logistic chaotic map to further enhance security.

- A difference-based embedding position selection strategy is proposed, which selects coefficient pairs with the smallest original differences for watermark embedding. This approach effectively minimizes embedding-induced distortion in the WHT coefficients, thereby preserving the high visual quality of the watermarked image.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the fundamental theories and mathematical derivations underlying the proposed algorithm. Section 3 details the specific procedures for watermark embedding and extraction. Section 4 describes the experimental setup, including dataset information and simulation results, and provides an in-depth analysis of the experimental data. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper with a comprehensive summary.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. WHT

WHT is a type of generalized Fourier Transform. Owing to its low computational complexity and high imperceptibility, WHT finds wide application in image compression and processing. The core component of WHT is the Hadamard matrix, which is generated by the Hadamard function. A Hadamard matrix is an orthogonal matrix composed of elements 1 and . The first-order Hadamard matrix, , is expressed as shown in Equation (1):

The second-order Hadamard matrix, , is expressed as shown in Equation (2):

The fourth-order Hadamard matrix, , is expressed as shown in Equation (3):

The N-th order Hadamard matrix, , is represented as given in Equation (4):

In the proposed method, the cover image is left-multiplied by the Hadamard matrix to concentrate energy in its first row. For a 2D image , the corresponding formulation of its WHT is given in Equation (5):

The inverse WHT of is given in Equation (6):

A concrete example is provided to illustrate the left-hand multiplication of a Hadamard matrix on an image block. For a 4 × 4 pixel block , its corresponding formulation is shown in Equation (7):

The WHT is applied to as shown in Equation (8):

The inverse WHT of is given in Equation (9):

2.2. Image Entropy

Image entropy quantifies statistical randomness. A lower entropy value typically implies a more predictable and structured image appearance. In watermarking, visual entropy and edge entropy are two common metrics that leverage the human visual system to identify suitable embedding regions. Visual entropy characterizes the texture of an image, and its calculation is given by Equation (10):

where represents the occurrence probability of event k, satisfying the constraint and . Edge entropy, which captures the influence of adjacent pixel values, is defined by Equation (11):

where means the uncertainty of the pixel value.

2.3. Logistic Chaos Mapping

To enhance security, the watermark is typically encrypted prior to the embedding stage. Chaotic security systems rely on non-linear dynamic systems characterized by inherent randomness and unpredictability. The Logistic map, a classic chaotic model, is employed to effectively disrupt the strong spatial correlation between adjacent pixels in the watermark image. Mathematically, the Logistic chaotic map is expressed as:

where denotes the state value generated at the n-th iteration, and serves as the control parameter. The system exhibits chaotic behavior when the parameter satisfies .

3. Proposed Method

The proposed algorithm is designed to achieve an optimal balance between two conflicting metrics: imperceptibility and robustness. Imperceptibility is governed by the magnitude of distortion introduced to the WHT coefficients, while robustness relies on the intensity of modifications. To address this trade-off, we propose a selection strategy involving entropy-based block selection and difference-based coefficient pair selection. This section provides a detailed description of the watermark embedding and extraction algorithms.

3.1. Watermark Embedding

3.1.1. Block Size Determination

The choice of block size influences the performance of the watermarking scheme. We evaluated the performance of and block configurations using images from the USC-SIPI Image Database under various attacks. As summarized in Table 1, the block size yields a higher Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Normalized Correlation (NC). Moreover, the configuration provides an embedding rate of 0.0833 bit/pixel, double that of the configuration, thereby offering a significant advantage in payload capacity. Consequently, the size is adopted.

Table 1.

Comparison of different block sizes.

3.1.2. Entropy-Based Block Selection

To enhance security and imperceptibility, we prioritize embedding in texture-suitable regions. For each block, the sum of visual entropy and edge entropy is calculated. Blocks with smaller entropy values are selected as embedding candidates. We compared the proposed low-entropy prioritization against a random selection strategy. The results in Table 2 demonstrate that the proposed strategy achieves higher PSNR and NC values.

Table 2.

Performance validation of the proposed entropy-based selection strategy compared to random selection.

3.1.3. Difference-Based Coefficient Pair Selection

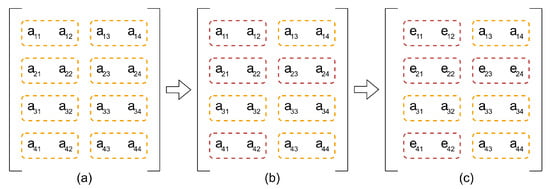

For the specific embedding position within a block, we propose a difference-based selection strategy. After applying WHT, the coefficient matrix is partitioned into pairs. The four pairs with the smallest differences are chosen for embedding, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the watermark embedding strategy based on WHT coefficient-pair selection: (a) A 4 × 4 coefficient block is divided into eight 1 × 2 pairs. (b) The four pairs with the smallest coefficient differences are selected. (c) Watermarked coefficients after embedding.

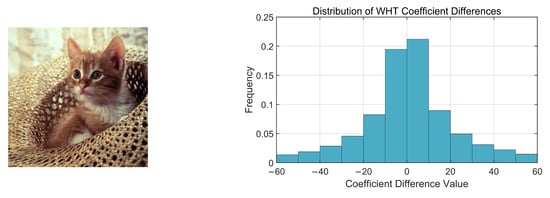

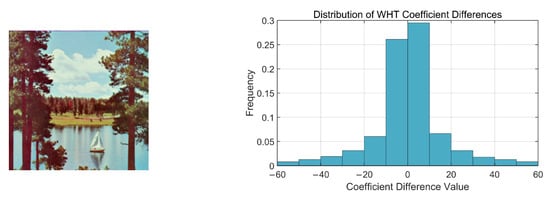

This strategy of prioritizing coefficient pairs with minimal differences provides a foundation for optimizing the trade-off between imperceptibility and robustness. According to the linearity of the inverse WHT, the distortion introduced in the spatial domain is directly proportional to the magnitude of coefficient modifications. Furthermore, the maximum modification strength of the coefficients is experimentally determined to ensure optimal visual quality while maintaining robustness, thus achieving a well-balanced trade-off between imperceptibility and robustness. Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the frequency distribution histograms of the coefficient pair differences for the images “Cat” and “Lake”, respectively.

Figure 2.

The image “Cat” and its corresponding frequency distribution histogram of the coefficient differences.

Figure 3.

The image “Lake” and its corresponding frequency distribution histogram of the coefficient differences.

3.1.4. Embedding Procedure

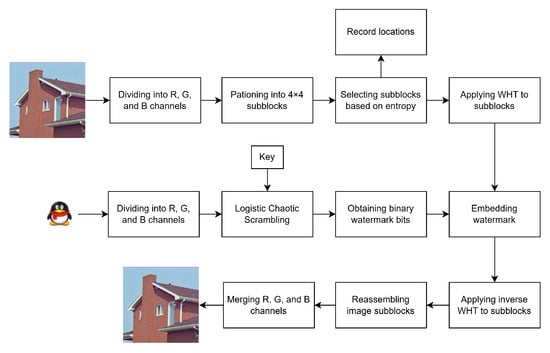

The complete workflow of the proposed embedding algorithm is depicted in Figure 4. Suppose I represents the color cover image and w denotes the watermark image. The detailed steps are executed as follows:

Figure 4.

The watermark embedding process flowchart.

- Divide I into R, G, and B channels. Partition each channel into non-overlapping blocks of size .

- Calculate the entropy for each block. The number of selected blocks is determined by the total bits of the watermark and the embedding capacity per block. In our method, each block accommodates 4 bits of watermark data. Therefore, all blocks are sorted by entropy in ascending order, and the first N blocks are selected, where N is the total watermark bits divided by 4. Record the positions of these blocks.

- Separate w into R, G, and B channels. Apply logistic map encryption to each channel to generate a scrambled bit sequence.

- Apply the WHT to each selected block in Step 2 using Equation (5).

- For each transformed block, identify four optimal coefficient pairs with the smallest differences using the selection described in Section 3.1.3. Store their coordinates in matrix P.

- Embed the watermark bits into the selected coefficients described in Algorithm 1.

- Apply the inverse WHT to the modified blocks via Equation (6) and recombine the R, G, and B channels to obtain the watermarked image.

| Algorithm 1 Watermark embedding |

|

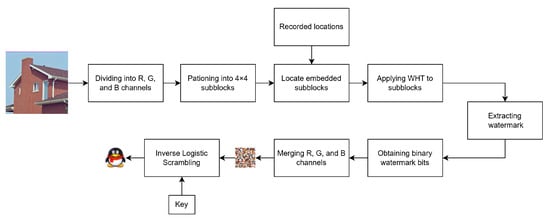

3.2. Watermark Extraction

In the watermark extraction phase, the watermarked image is separated into R, G, and B channels, and each channel is partitioned into non-overlapping blocks. The coordinates recorded during the embedding stage are used to locate the specific blocks containing the watermark. The WHT is then applied to these blocks to obtain the coefficient matrices. The binary watermark bits are extracted by comparing the coefficients at the pre-recorded positions. These bits are recombined to reconstruct the encrypted watermark sequence. Finally, the logistic map decryption process is applied using the correct security keys to recover the original watermark image.

Suppose denotes the watermarked image. The complete workflow of the proposed watermark extraction algorithm is illustrated in Figure 5, and the detailed steps are as follows:

Figure 5.

The watermark extraction process flowchart.

- Separate the watermarked image into R, G, and B channels, and divide each channel into non-overlapping blocks.

- Identify the target blocks based on the coordinates recorded during the embedding stage.

- Apply the WHT to each identified block according to Equation (5).

- Retrieve the embedded WHT coefficient positions recorded during the embedding stage.

- Extract the watermark bits from these positions using Algorithm 2.

- Reconstruct the scrambled binary watermark sequence from the extracted bits.

- Combine the sequences from R, G, and B channels to form the encrypted watermark image.

- Recover the original watermark by applying the inverse Logistic chaotic permutation to the encrypted image.

| Algorithm 2 Watermark extraction |

|

4. Experimental Results

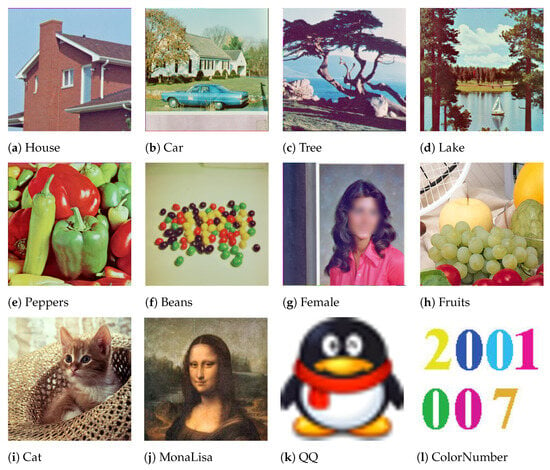

The benchmark methods [35,36,37] selected for comparison in this section are all based on a Hadamard Transform framework, where a Hadamard matrix is left-multiplied before watermark embedding in the transform domain. This common methodological foundation ensures an objective and equitable basis for comparison with the proposed algorithm. In the subsequent imperceptibility and robustness experiments, both the proposed algorithm and the benchmark methods are carried out under identical experimental conditions. All experiments were conducted on RGB cover images and RGB watermarks, with implementations performed in MATLAB 2024a. In the chaotic encryption phase, the control parameter and the initial value of the Logistic map are set to and , respectively, to ensure the system operates in a fully chaotic state. The specific sources of the datasets are detailed in the Data Availability Statement. Figure 6 displays the cover images and watermarks used in this study.

Figure 6.

Cover images (a–j) and watermark image (k,l).

To evaluate the imperceptibility of the proposed algorithm, the PSNR and Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) are employed, whereas the Normalized NC and Bit Error Rate (BER) are adopted to assess its robustness.

PSNR is employed to quantify the pixel-level distortion between the cover image I and the watermarked image . A higher PSNR value indicates greater similarity between the two images. For color images, the overall PSNR is calculated as shown in Equation (13):

where the PSNR of the i-th channel is given by Equation (14):

where correspond to the R, G, and B channels, respectively; M and N denote the number of rows and columns of the color image; represents the pixel value of the cover image I at coordinates in the i-th channel; and represents the corresponding pixel value of the watermarked image .

SSIM evaluates the similarity between two images based on luminance, contrast, and structural similarity. Along with PSNR, it is one of the most widely adopted metrics for assessing imperceptibility in image watermarking. The value of SSIM closer to 1 indicates a higher degree of similarity between the two images. The SSIM is defined as shown in Equation (15):

where , , and represent the luminance, contrast, and structural comparisons, respectively, and , , and are weighting exponents.

NC measures the correlation between the original watermark w and the extracted watermark . The value of NC closer to 1 indicates that the watermark has been accurately and completely extracted, reflecting strong resistance to attacks. The NC is defined as shown in Equation (16):

where correspond to the R, G, and B channels, while M and N denote the number of rows and columns of the watermark image, respectively. and represent the pixel values at coordinates in the i-th channel of the original watermark w and the extracted watermark , respectively.

BER directly quantifies the extent of errors in the extracted watermark caused by attacks on the watermarked image. A lower BER indicates stronger robustness of the watermarking algorithm, with BER = 0 meaning perfect extraction. The BER is defined as shown in Equation (17):

where correspond to the R, G, and B channels of the color image, ⊕ denotes the XOR operation, and M and N represent the number of rows and columns of the watermark image, respectively. and denote the pixel values at coordinates in the i-th channel of the original watermark w and the extracted watermark , respectively.

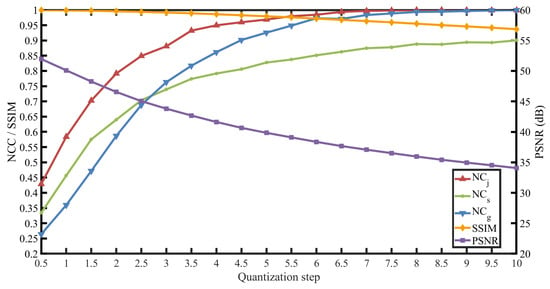

To determine the optimal quantization step size, simulation experiments were conducted using the entire USC-SIPI Image Database to ensure statistical reliability. Since attacks within the same category exhibit similar characteristics, representative attacks are selected from common types of image processing operations, including compression, geometric distortions, and enhancement attacks. Specifically, JPEG2000 compression (CR = 4), Scaling (0.9), and Gaussian noise (0.03%) are employed to simulate typical attacks. The quantization step size T is gradually increased during the experiment, and both imperceptibility (evaluated by PSNR and SSIM) and robustness (evaluated by NC) are assessed.

The experimental results, calculated as statistical averages, are illustrated in Figure 7. In the figure, denotes the average NC value under JPEG2000 attack, represents the average NC value under Scaling attack, and corresponds to the average NC value under Gaussian noise attack. The PSNR and SSIM values are computed without any attack. As the quantization step size T increases, the PSNR and SSIM values decrease, while the NC values increase. Specifically, a sensitivity analysis reveals a consistent trend across all three attack types: robustness improves rapidly at lower T values and subsequently stabilizes. This trend implies that a larger T enhances robustness at the cost of reduced imperceptibility. This process validates that the proposed method maximizes robustness while maintaining acceptable imperceptibility. In this paper, based on these global statistics, T = 8 is chosen as the quantization step size. It provides sufficient robustness margin for noise and compression attacks while maintaining the average PSNR above 35 dB, as PSNR > 35 dB generally indicates good visual quality [44].

Figure 7.

The average value of PSNR, SSIM, , and with different quantization steps.

4.1. Imperceptibility Analysis

In digital watermarking, good imperceptibility requires that the watermarked image be visually indistinguishable from the original cover image under human visual perception. To evaluate the imperceptibility of the proposed algorithm, we conducted an imperceptibility analysis using the images shown in Figure 6 as the cover and watermark images. The proposed watermarking algorithm is compared with the algorithms [35,36,37], all of which are based on the Hadamard Transform framework. The experimental results are presented in Table 3. Guided by the widely accepted benchmarks where PSNR dB indicates good visual quality [44] and SSIM is considered acceptable [45], we analyze the performance as follows. It can be observed that for multiple cover images, the proposed algorithm consistently achieves PSNR values greater than 35 dB and SSIM values above 0.96, indicating stable performance. Although Algorithms [35,36] achieve higher SSIM values in certain cases, their PSNR values sometimes <35 dB, reflecting less stable performance. Considering that SSIM > 0.93 is generally regarded as acceptable, the proposed algorithm provides higher and more stable PSNR performance while maintaining high SSIM values. Overall, in terms of imperceptibility, the proposed algorithm outperforms Algorithms [35,36]. Although Algorithm [37] demonstrates excellent imperceptibility, with both PSNR and SSIM values significantly higher than those of the compared methods, it exhibits a relatively high BER for watermark extraction even in the absence of attacks, and shows weak robustness against various attacks. This suggests that Algorithm [37] overemphasizes imperceptibility at the expense of accurate watermark recovery.

Table 3.

Comparison of PSNR/SSIM values among different watermarking algorithms under no-attack conditions.

In addition to ensuring imperceptibility, one of the core objectives of a watermarking algorithm is the complete extraction of watermark information. Table 4 presents a comparison of the NC and BER results among the proposed method and Algorithms [35,36,37]. The experimental results show that, for all tested images, the value of NC is 1 and the value of BER is 0 for the watermarks extracted using the proposed method, which are identical to those of the original watermark, thereby demonstrating perfect recovery. In contrast, Algorithms [35,36,37] fail to achieve complete extraction in certain watermarked images.

Table 4.

Comparison of NC/BER values among different watermarking algorithms under no-attack conditions.

4.2. Robustness Analysis

Digital images transmitted over networks are vulnerable to various processing operations and malicious attacks. Therefore, when designing a robust watermarking scheme, it is essential to ensure that the watermark remains both extractable and recognizable after attacks. Consequently, robustness against attacks has become one of the core criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of watermarking algorithms.

A series of robustness analysis experiments are conducted using the representative images displayed in Figure 6 as the cover images and watermarks. Table 5 summarizes the parameters for each attack type and presents the NC values obtained by comparing the original watermark with the extracted watermarks. To quantitatively evaluate the robustness, we establish the following criteria: an NC value greater than 0.90 indicates high-fidelity recovery, while an NC value between 0.70 and 0.90 implies that the watermark content is clearly recognizable and acceptable. The results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm can successfully extract recognizable watermarks under a wide range of attacks.

Table 5.

Attack parameters and corresponding extraction performance (NC).

4.3. Robustness Comparison

This section presents robustness comparison experiments using the cover and watermark images in Figure 6, comparing the proposed method with state-of-the-art algorithms [35,36,37].

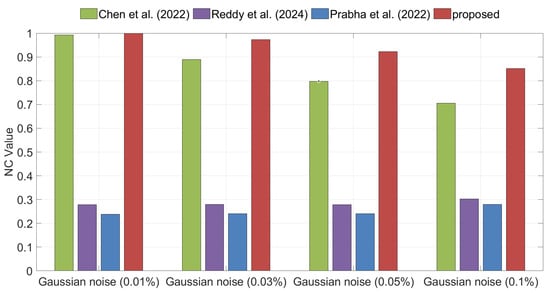

4.3.1. Robustness Against Common Image Processing Attacks

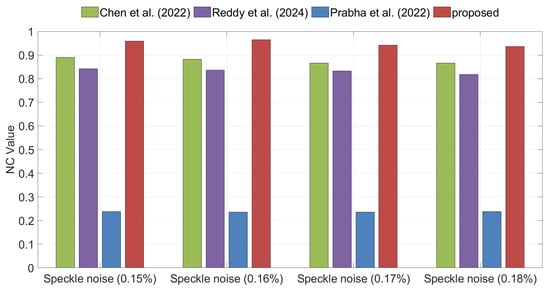

Noise attacks are among the most common types of image distortions, with Gaussian noise and Speckle noise being two representative forms. Figure 8 and Figure 9 illustrate the NC values of the extracted watermarks under Gaussian and Speckle noise for different watermarking algorithms. The experimental results demonstrate that, under both types of noise attacks, the proposed method consistently achieves the highest NC values, indicating superior robustness compared with the benchmark methods.

Figure 8.

Comparison of robustness under Gaussian noise attacks between the proposed method and the methods of Chen et al. [35], Reddy et al. [36], and Prabha et al. [37].

Figure 9.

Comparison of robustness under Speckle noise attacks between the proposed method and the methods of Chen et al. [35], Reddy et al. [36], and Prabha et al. [37].

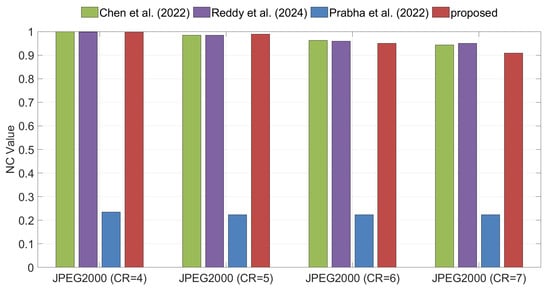

JPEG2000 is a widely adopted image compression standard. Figure 10 shows the NC values of the extracted watermarks under JPEG2000 compression for different watermarking algorithms. The results show that the proposed method yields slightly lower NC values compared with Algorithms [35,36], but achieves higher NC values than Algorithm [37]. Importantly, the NC values of the proposed method remain above 0.9 across all tested compression parameters, indicating that the extracted watermarks are still clearly recognizable. This is because JPEG2000 compression shifts pixel differences into the high-frequency components and discards part of the information through coarse quantization during compression. Since the proposed method embeds the watermark into WHT coefficients with small differences, it is inherently more sensitive to pixel variations, which explains why its robustness advantage is less pronounced under JPEG2000 compression attacks.

Figure 10.

Comparison of robustness under JPEG2000 compression attacks between the proposed method and the methods of Chen et al. [35], Reddy et al. [36], and Prabha et al. [37].

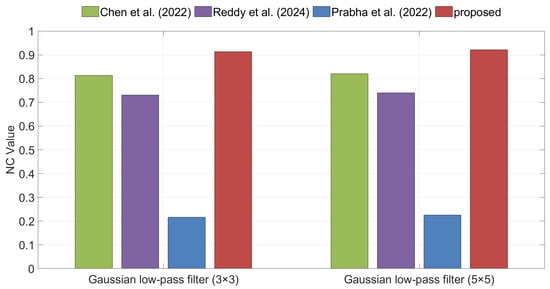

Filtering represents another major category of image attacks, among which Gaussian low-pass filtering is widely adopted. Figure 11 compares the NC values of the extracted watermarks for different algorithms under Gaussian low-pass filtering. The results show that the proposed method exhibits a clear performance advantage in this scenario, achieving higher NC values than the competing methods and thereby verifying its effectiveness against Gaussian low-pass filtering attacks.

Figure 11.

Comparison of robustness under Gaussian low-pass filter attacks between the proposed method and the methods of Chen et al. [35], Reddy et al. [36], and Prabha et al. [37].

4.3.2. Robustness Against Geometric Attacks

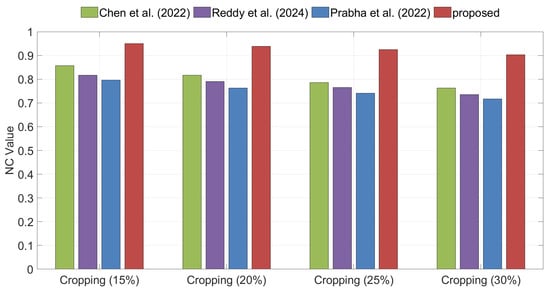

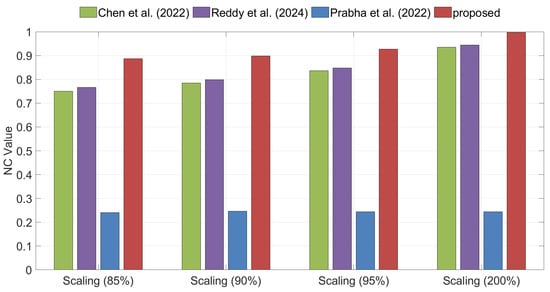

Cropping, Scaling, and Rotation are typical types of geometric attacks. Figure 12 illustrates the NC values of the extracted watermarks for different algorithms under cropping attacks. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves significantly higher NC values than other methods. Figure 13 presents the NC values of the extracted watermarks under scaling attacks, where the proposed method consistently achieves higher NC values than the competing algorithms. In summary, the proposed algorithm demonstrates strong robustness against both Cropping and Scaling attacks.

Figure 12.

Comparison of robustness under Cropping attacks between the proposed method and the methods of Chen et al. [35], Reddy et al. [36], and Prabha et al. [37].

Figure 13.

Comparison of robustness under Scaling attacks between the proposed method and the methods of Chen et al. [35], Reddy et al. [36], and Prabha et al. [37].

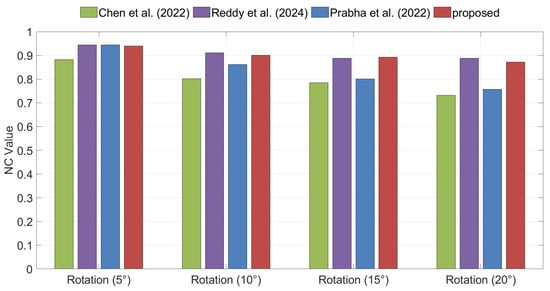

For rotation angles of and , the proposed method achieves higher NC values than Algorithm [35] but slightly lower values than Algorithms [36,37]. However, since all algorithms yield NC values above 0.9 at these angles and the extracted watermarks remain clearly recognizable, the differences between the methods are insignificant. At a rotation of , the proposed method outperforms all compared methods in terms of NC values. When the angle increases to , the proposed method achieves higher NC values than Algorithms [35,37], though slightly lower than Algorithm [36] (Figure 14). Overall, the proposed method can effectively extract watermarks subjected to various rotation angles.

Figure 14.

Comparison of robustness under Rotation attacks between the proposed method and the methods of Chen et al. [35], Reddy et al. [36], and Prabha et al. [37].

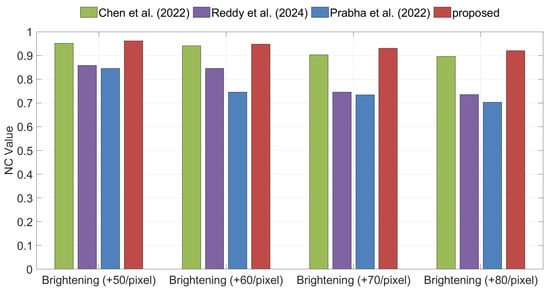

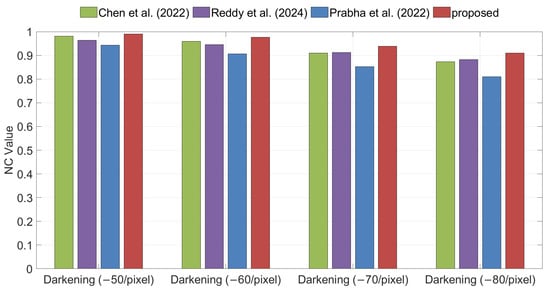

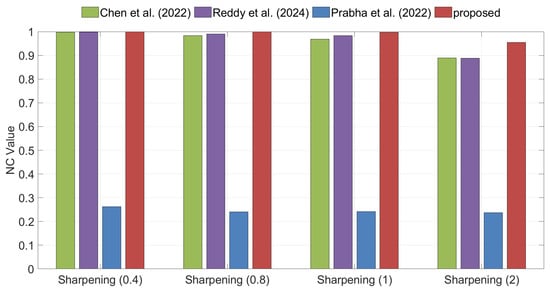

4.3.3. Robustness Against Image Enhancement Attacks

Brightening, Darkening, and Sharpening are typical types of image enhancement attacks. Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17 illustrate the watermark extraction results of different algorithms under these three attacks. The experimental results demonstrate that, across various attack parameters, the proposed method consistently achieves higher NC values than all competing methods, indicating superior robustness against these three types of image enhancement attacks.

Figure 15.

Comparison of robustness under Brightening attacks between the proposed method and the methods of Chen et al. [35], Reddy et al. [36], and Prabha et al. [37].

Figure 16.

Comparison of robustness under Darkening attacks between the proposed method and the methods of Chen et al. [35], Reddy et al. [36], and Prabha et al. [37].

Figure 17.

Comparison of robustness under Sharpening attacks between the proposed method and the methods of Chen et al. [35], Reddy et al. [36], and Prabha et al. [37].

4.3.4. Robustness Comparison Under Aligned Imperceptibility

It is well-established in watermarking research that imperceptibility and robustness are conflicting attributes. A strictly fair comparison requires normalizing the visual quality to evaluate the robustness performance. However, the baseline methods [35,36,37] exhibit widely varying PSNR levels (ranging from ≈33 dB to ≈52 dB) due to their fixed parameter settings, making direct comparison difficult.

To address this, we dynamically adjusted the quantization step size T of the proposed algorithm to strictly align its PSNR with each baseline method. The experimental results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Robustness comparison under aligned imperceptibility levels. The quantization step size T of the proposed method is dynamically adjusted to match the PSNR of each baseline method. The “Average NC” represents the mean value calculated over all simulated attacks.

These results conclusively demonstrate that the proposed algorithm optimizes the trade-off between imperceptibility and robustness more effectively than the state-of-the-art methods. The proposed scheme consistently yields higher watermark extraction accuracy under the same visual quality constraints.

4.4. Embedding Capacity Analysis

In this section, the embedding capacity of the proposed algorithm is compared with state-of-the-art image watermarking algorithms [35,36,37]. With the exception of [35], all other algorithms achieve a maximum embedding capacity exceeding 0.25 bits per pixel. During the watermark embedding process [35,36,37], and the proposed method all partition the cover image into 4 × 4 blocks; however, ref. [35] embeds 2 bits per block, whereas [36,37], and the proposed method embed 4 bits per block.

Table 7 presents the maximum embedding capacity of the different watermarking algorithms.

Table 7.

Comparison of the maximum watermark embedding capacity across different algorithms.

4.5. Real-Time Test

To evaluate the computational efficiency of the proposed scheme, the execution time for watermark embedding and extraction was measured. The experiments were conducted on a computer equipped with an Intel Core i7-9750H CPU(Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), 16 GB RAM, and MATLAB R2024a. The average execution time was calculated over 1000 independent runs on cover images of size and watermarks of size . Table 8 compares the average execution times of the proposed scheme with methods [35,36,37].

Table 8.

Comparison of average execution time (seconds).

It can be observed that the proposed method requires slightly more time compared to the referenced algorithms. This marginal increase in computational cost is primarily attributed to the Logistic chaotic encryption and the entropy calculation and sorting. However, considering the significant improvements in robustness and security demonstrated in previous sections, this trade-off is well-justified. Furthermore, the total execution time remains within the order of seconds, ensuring the algorithm’s feasibility for practical applications.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a robust color image watermarking algorithm based on the WHT is proposed. The algorithm first divides the cover image into non-overlapping blocks, from which optimal embedding blocks are selected by integrating visual entropy and edge entropy. After applying the WHT to the selected blocks, a novel embedding position selection strategy based on asymmetric coefficient difference analysis is introduced. Watermark bits are then embedded into coefficient pairs with smaller differences, effectively enhancing the imperceptibility of the watermark. Through experimental evaluation, the optimal embedding strength is identified, enabling the proposed method to achieve a desirable balance between robustness and imperceptibility. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves superior performance in terms of both imperceptibility and robustness. Furthermore, comparative analysis with existing WHT-based watermarking algorithms confirms the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed approach. In our future work, we plan to conduct in-depth theoretical research on the entropy changes of image blocks and coefficient differences during the embedding process. Our goal is to eliminate the reliance on auxiliary data and achieve a fully blind watermarking extraction mechanism with a stronger theoretical foundation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.J.; methodology, Y.J. and S.S.; software, Y.J.; validation, S.S.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, Y.J.; resources, S.Y.; data curation, H.W., J.W. and Z.Z.; visualization, Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.J.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and Y.L.; supervision, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Fund under Grant 2023A1515011472.

Data Availability Statement

The cover images used in this study were derived from publicly accessible resources: the USC-SIPI Image Database (available at https://sipi.usc.edu/database (accessed on 27 December 2025)) and the image collection of the “CS511-Topics in Computer Graphics” course at the Illinois Institute of Technology (available at http://www.cs.iit.edu/~agam/cs511/data/images/index.html (accessed on 27 December 2025)). For privacy protection, the facial regions in the displayed figures were blurred in this paper, while the original unaltered images from these datasets were used in the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Mohamed, A.F.; Samra, A.S.; Yousif, B.; Tawkol Khalil, A. Enhanced brain image security using a hybrid of lifting wavelet transform and support vector machine. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzgiene, R.; Venckauskas, A.; Grigaliunas, S.; Petraska, J. Enhancing Steganography through Optimized Quantization Tables. Electronics 2024, 13, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M.R.; Paterson, K.G. Analyzing Cryptography in the Wild: A Retrospective. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2024, 22, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskar, R.; Dwibedi, R.K.; Kumar, T.; Vijayalakshmi, N.; Rajesh Kanna, R.; Reddy, G.N. Digital Watermarking Techniques for Secure Image Distribution. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent and Innovative Technologies in Computing, Electrical and Electronics (IITCEE), Bangalore, India, 24–25 January 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlaskar, S.A.; Kirupakaran, A.M.; Laskar, R.H. A Human Visual System-Based Blind Image Watermarking Scheme in the IWT-APDCBT Domain Integrating Geometric and Non-Geometric Distortion Correction Techniques. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 3979–4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferik, B.; Laimeche, L.; Meraoumia, A.; Laouid, A.; AlShaikh, M.; Chait, K.; Hammoudeh, M. An Efficient Semi-blind Watermarking Technique Based on ACM and DWT for Mitigating Integrity Attacks. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 50, 15885–15905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, C.; Ren, N. Template Watermarking Algorithm for Remote Sensing Images Based on Semantic Segmentation and Ellipse-Fitting. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedillo-Hernandez, A.; Velazquez-Garcia, L.; Cedillo-Hernandez, M.; Conchouso-Gonzalez, D. Fast and robust JND-guided video watermarking scheme in spatial domain. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, N.; Guo, S.; Zhu, C.; Hu, Y. A zero-watermarking scheme based on spatial topological relations for vector dataset. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 226, 120217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malanowska, A.; Mazurczyk, W.; Araghi, T.K.; Megías, D.; Kuribayashi, M. Digital Watermarking—A Meta-Survey and Techniques for Fake News Detection. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 36311–36345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Luo, Y.; Liu, J.; Qiu, S. A Blind and Robust Image Watermarking Algorithm in the Spatial Domain using Two-level Partition. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2024, 29, 1705–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, G.; Wu, X. Hide and track: Towards blind video watermarking network in frequency domain. Neurocomputing 2024, 579, 127435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo El-Soud, M.W.; Meselhy Eltoukhy, M.; Abdel-Aziz, M.M.; Alourani, A.; Hosny, K.M. Robust Blind Watermarking to Secure Color Medical Images Using Multidimensional-FFT Fusing LFSR-Encryption and LZW Compression. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 46054–46069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdElHaleem, S.H.; Abd-El-Hafiz, S.K.; Radwan, A.G. Secure blind watermarking using Fractional-Order Lorenz system in the frequency domain. AEU—Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2024, 173, 154998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounceur, A.; Kara, M.; Ferik, B.; Laouid, A. An adaptive ACM watermarking technique based on combined feature extraction and non-linear equation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 275, 126954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Wang, M.; Wu, B. Efficient Robust Reversible Watermarking Based on ZMs and Integer Wavelet Transform. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 4115–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Kaplan, R.; Johnson, J.; Fei-Fei, L. HiDDeN: Hiding Data with Deep Networks. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of the COMPUTER VISION—ECCV 2018, PT 15, 15th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 11219, pp. 682–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, X. A Novel Two-stage Separable Deep Learning Framework for Practical Blind Watermarking. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM ’19, New York, NY, USA, 21–25 October 2019; pp. 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wengrowski, E.; Dana, K. Light Field Messaging With Deep Photographic Steganography. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tancik, M.; Mildenhall, B.; Ng, R. StegaStamp: Invisible Hyperlinks in Physical Photographs. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 2114–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Jia, Z.; Ma, Z.; Chang, E.C.; Zhang, W. PIMoG: An Effective Screen-shooting Noise-Layer Simulation for Deep-Learning-Based Watermarking Network. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM ’22, New York, NY, USA, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 2267–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, T.; Zhao, B.; Shi, R.; Han, M.; Hassaballah, M.; Retraint, F.; Luo, X. Scalable Universal Adversarial Watermark Defending Against Facial Forgery. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 8998–9011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Lu, W.; Luo, X. Robust Watermarking Based on Multi-Layer Watermark Feature Fusion. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2025, 27, 5156–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, F.; Zhang, X.; Feng, G. Print-Camera Resistant Image Watermarking with Deep Noise Simulation and Constrained Learning. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 2164–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Zhu, X.; Li, F.; Yao, H.; Qin, C. DoBMark: A double-branch network for screen-shooting resilient image watermarking. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 246, 123159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Guo, D.; Wang, T.; Yao, H.; Li, J.; Qin, C. Universal screen-shooting robust image watermarking with channel-attention in DCT domain. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Sun, Y.; Xia, Y.; Wang, Z. A robust color image watermarking scheme in the fusion domain based on LU factorization. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 174, 110726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, D.; Vasil’ev, V. Color image watermarking scheme based on singular value decomposition of split quaternion matrices. J. Frankl. Inst. 2025, 362, 107508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, F.; Xu, S.; Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Su, M.; Liu, J. CONCEAL: A robust dual-color image watermarking scheme. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 208, 118133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.T. Synergistic compensation for RGB-based blind color image watermarking to withstand JPEG compression. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2024, 80, 103673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaito, H.; Tetsuya, M.; Hirotsugu, K.; Sumiko, M. A Blind Color Image Watermarking for Grayscale Watermark Based on Tensor Decomposition. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 48th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Osaka, Japan, 2–4 July 2024; pp. 2014–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, R.; Srivastava, V.K. IWT based robust and secure color image watermarking using Hessenberg decomposition and SVD. J. Opt. 2024, 54, 2866–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Hu, F.; Tian, X.; Su, L.; Cao, S. A fusion-domain intelligent blind color image watermarking scheme using graph-based transform. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 177, 111191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Sun, J. QR decomposition of dual quaternion matrix and blind watermarking scheme. Numer. Algorithms 2024, 99, 1763–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Su, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, G. A high-efficiency blind watermarking algorithm for double color image using Walsh Hadamard transform. Vis. Comput. 2022, 38, 2189–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinadh Reddy, K.; Reddy, S.N. A Novel Blind Double-Color Image Watermarking Algorithm Utilizing Walsh—Hadamard Transform with Symmetric Embedding Locations. Symmetry 2024, 16, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabha, K.; Shatheesh Sam, I. An effective robust and imperceptible blind color image watermarking using WHT. J. King Saud Univ.—Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 2982–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.J.; Shelke, R. An effective digital audio watermarking using a deep convolutional neural network with a search location optimization algorithm for improvement in Robustness and Imperceptibility. High-Confid. Comput. 2023, 3, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsafar, P. PSO-based Quaternion Fourier Transform steganography: Enhancing imperceptibility and robustness through multi-dimensional frequency embedding. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 120, 109787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Qiu, Y.; Su, Q.; Shi, C.; Liu, Z. Enhancing Watermarking Robustness and Invisibility with Growth Optimizer and Improved LU Decomposition. Optik 2025, 329, 172353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Guan, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Niu, B.; Zhang, G. Robust Texture-Aware Local Adaptive Image Watermarking with Perceptual Guarantee. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 4660–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeinaddini, E. Selecting optimal blocks for image watermarking using entropy and distinct discrete firefly algorithm. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 9685–9699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.R.R.; Kumar, V.V.; Naidu, K.R. Digital image watermarking using DWT-SVD with enhanced tunicate swarm optimization algorithm. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 28259–28279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosazadeh, M.; Ekbatanifard, G. An improved robust image watermarking method using DCT and YCoCg-R color space. Optik 2017, 140, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Yang, S.; Zhang, S. COVER: A Secure Blind Image Watermarking Scheme. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 41, 6931–6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.