Abstract

Utilizing the Kolmogorov–Arnold representation theorem, KANs have emerged as a mathematically rigorous and easily interpretable alternative to traditional neural networks. These networks decompose high-dimensional functions into sums of univariate continuous functions using adaptive activation functions. Compared to MLPs, KANs exhibit superior or comparable performance in accuracy, parameter efficiency, and interpretability. Applications highlight the advantages of KANs in solving complex partial differential equations with enhanced convergence and uncertainty quantification, modeling dynamic systems in a meaningful manner, and making reliable forecasts in the areas of power systems, environmental monitoring, and demand prediction. Based on current research on KANs, they demonstrate a promising frontier in interpretable deep learning, with increasing influence across numerous interdisciplinary scientific and engineering fields.

1. Theoretical Foundations of Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks

Symmetry, as an intrinsic property of both natural and mathematical systems, enhance model generalizability. It also serves as a crucial bridge linking data-driven approaches to mechanistic modeling. This characteristic is also evident in the recently emerged KAN field. A KAN is theoretically based on the Kolmogorov–Arnold representation theorem, which states that any continuous multivariate function with a bounded domain can be reduced to a finite composition of univariate continuous functions and the binary operation of addition for any multivariate continuous function [1]. The theorem provides a constructive method of function approximation, suggesting that high-dimensional mappings can be broken down into simple univariate components, which ultimately influences KAN architecture by guiding the decomposition of complex functions into univariate function compositions. Making the neural network design have a clear mathematical grounding and fundamentally improving model structure interpretability.

This theorem led to KANs being developed as an alternative to MLPs. Hecht-Nielsen initially proposed shallow Kolmogorov networks based on the theorem, but their practical ineffectiveness arose from poor univariate function properties [2]. Later, Liu et al. deepened this framework to develop KANs, which integrate learnable activation functions to enhance performance, effectively combining the structural insights of Kolmogorov networks with the flexibility of MLPs [3]. Mathematically, KANs approximate functions as cascaded compositions of layers (), where each layer is a sum of univariate functions , often parameterized by basis functions (e.g., B-splines, polynomials) with learnable coefficients [4].

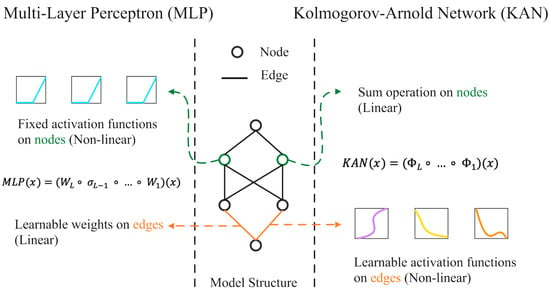

The structure of KANs differs fundamentally from the structure of MLPs. Based on linear transformations, traditional MLPs apply fixed nonlinear activations (e.g., Tanh, ReLU) at nodes, according to the following form [5]:

Here, denotes the weights between network layers, and represents the activation function. Contrary to KANs, the edges (weights) of KANs contain learnable univariate activation functions, while the nodes only perform summation operations. As a result, the computational graph has been shifted to

where denotes matrices of univariate functions (e.g., B-splines, orthogonal polynomials) replacing scalar weights [6,7]. This edge-based activation design eliminates the need for separate linear weight matrices, integrating transformation and nonlinearity into a unified, interpretable layer structure [8]. Figure 1 shows the comparison between them.

Figure 1.

MLPs vs. KANs.

In terms of their approximation mechanism, MLPs differ functionally from KANs. A KAN, in contrast to MLPs, implements the Kolmogorov–Arnold decomposition explicitly by summing compositions of parameterized univariate functions, rather than using nested layers of linear combinations followed by fixed nonlinearities [9]. Accordingly, KANs benefit from guaranteed constructive representation under the theorem, which complements MLPs’ universal approximation capability in a theoretically grounded manner [10,11]. KANs’ activation functions are highly flexible; early implementations used B-splines (e.g., vanilla PIKAN), while variants adopt orthogonal polynomials (Chebyshev, Jacobi), radial basis functions, or fractional Jacobi polynomials to improve efficiency, stability, or adaptability [12].

Training strategy and parameter complexity further distinguish KANs from MLPs. During the training phase, MLPs adjust the linear weights on the edges while keeping the nonlinear activation functions on the nodes fixed; while KANs adapt the nonlinear activation functions on the edges while keeping the linear operations on the nodes fixed. Due to the size of the grid and the polynomial order of the spline grids, KANs may be more complex. However, modified variants (e.g., Chebyshev-KAN) often reduce redundant parameters, enabling compact architectures with fewer nodes than MLPs [13]. By replacing linear layers with KAN-based function matrices, this structural and functional divergence distinguishes KANs from MLPs as an interpretable, theoretically grounded alternative. This paper makes the following contributions:

- According to the latest research using KANs, 80 papers were selected for analysis and review based on journal impact factors, citation counts, publication years, and journal rankings.

- This paper provides an overview of KAN applications across multiple domains. Analyzing the characteristics of these models enables readers to better apply and understand these models within their respective fields.

- This paper contains comparative research on KANs. It enables readers to gain a deeper understanding of the KAN model, facilitating its more judicious application.

- This paper explores existing challenges, limitations, and future research directions, providing relevant insights for subsequent research and development.

2. Architecture and Variants of KAN Models

Classical KANs are rooted in the Kolmogorov–Arnold representation theorem, decomposing multivariate functions into sums of learnable univariate activations on network edges, distinct from fixed node activations in traditional MLPs [14,15]. B-splines serve as the foundational activation of offering smooth, piecewise polynomial approximations. Their mathematical formulation typically combines a residual-like term with B-spline basis functions:

With scaling magnitude, as a basis function (e.g., SiLU), as trainable coefficients, and as B-spline basis functions. This activation function is well-suited to image recognition [16] and time series data prediction [17].

An extension of the KAN architecture that integrates sinusoidal embeddings with MLP layers is the FCN-KAN. The function is defined as

In this equation, is a learnable coefficient representing the frequency of sinusoidal functions and is the input value.

KAN layers are structured as matrices of such spline functions, enabling compositional multivariate mapping [18,19]. Computationally, B-splines support grid adaptation to enhance pattern capture [20], but incur higher complexity due to iterative basis calculations, limiting scalability in deep networks [21,22]. Practical implementations optimize spline order and grid points to balance performance and cost [23,24]. Furthermore, KANs reduce computational complexity by limiting node operations to simple additions and streamlining the computation process [25].

RBF-KAN is a quicker version of Spline-KAN that calculates the higher-order B-spline basis with Gaussian RBFs described as

In this equation, is the radial distance between input and grid center points , and it can be calculated as . denotes the width or extent of the Gaussian function specified by the grid range.

Polynomial basis functions, including orthogonal variants, offer alternatives to splines. Traditional polynomial KANs suffer from numerical instability (e.g., Runge’s phenomenon), but orthogonal polynomials (e.g., Chebyshev, Jacobi) mitigate this with bound outputs and improved derivatives. Chebyshev-KAN approximates functions as follows:

where is the normalized input value of , represents Chebyshev polynomials and .

Instead of spline coefficients, the Naive-Fourier-KAN uses 1-D Fourier coefficients. By using the Fourier series, this layer approximates the KAN univariate functions. The definition of this layer is as follows:

Here and are Fourier coefficients, is the input value. The number of Fourier terms (grid size) is .

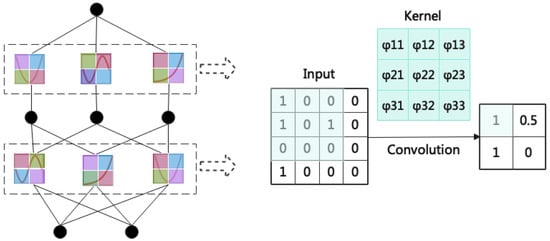

Recent advancements in enhanced KAN architectures focus on adaptive and hybrid designs. These designs integrate adaptive basis functions, attention mechanisms, and combinations of established deep learning components. The CKAN is one of the most basic structures. It combines the nonlinear modeling advantages of KAN with the spatial feature extraction capabilities of convolution operations. This breaks through traditional CNN performance bottlenecks in terms of feature representation and parameter efficiency, creating an overall optimization effect. Figure 2 shows the structure of a basic CKAN model.

Figure 2.

Basic CKAN model.

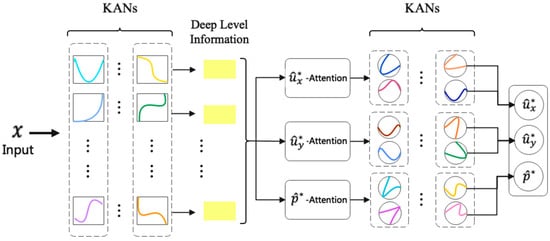

Another one, the KAN-MHA model, combines adaptive basis functions with MHA, enabling focused learning on critical flow regions (e.g., leading/trailing edges of airfoils) via parallel attention heads, significantly improving prediction accuracy and consistency in flow field modeling [26]. Figure 3 illustrates the overall structure of the model.

Figure 3.

Multi-head attention KAN structure.

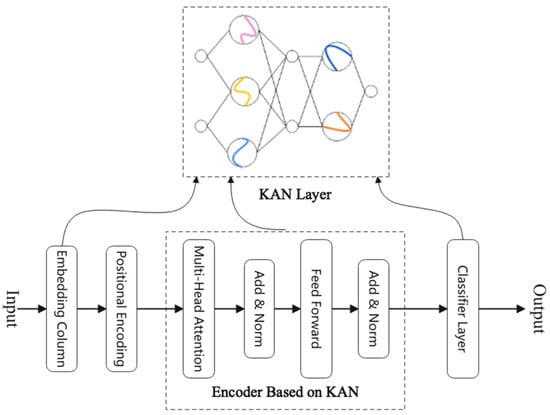

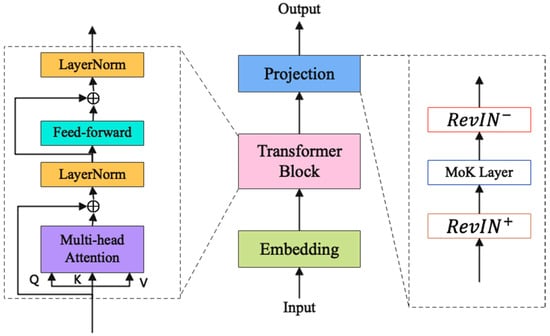

Hybridization with Transformers has emerged as a key strategy, with models like TFKAN and MTF-AViTK replacing traditional MLP layers in Transformers with KAN layers. For KAN layers’ compact representation, TFKAN reduces parameter counts by 78% compared to conventional Transformers while maintaining high accuracy in IoT intrusion detection, demonstrating the efficiency of combining a Transformer with KAN’s adaptive representations [9]. MTF-AViTK integrates KAN into an adaptive ViT for tool wear recognition, using self-attention for feature extraction and KAN in the classification layer to handle complex nonlinear mappings [27]. KANEFT further advances this by introducing Linear-KAN and Convolutional-KAN layers within a Transformer framework for hyperspectral image classification, where Convolutional-KAN enables multi-scale local feature extraction alongside spatial attention for global context integration [28].

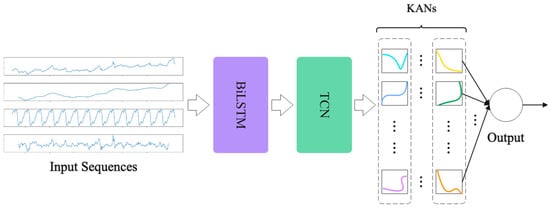

For sequence and temporal data, hybrid KAN models with RNNs and TCNs have been developed. In BiLSTM-KAN, the temporal dependency capture of LSTM is integrated with the nonlinear feature extraction of KAN, thus increasing the robustness of time series forecasting, while TCN-KAN incorporates the multi-scale local dependency modeling of TCN with KAN’s adaptive transformations to reduce overfitting when predicting electricity demand [29]. A KAN model combined with BiLSTM and TCN is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

KAN model combined with BiLSTM and TCN.

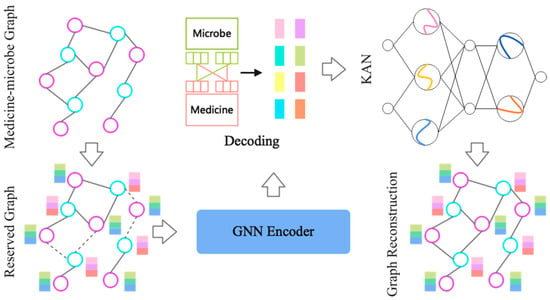

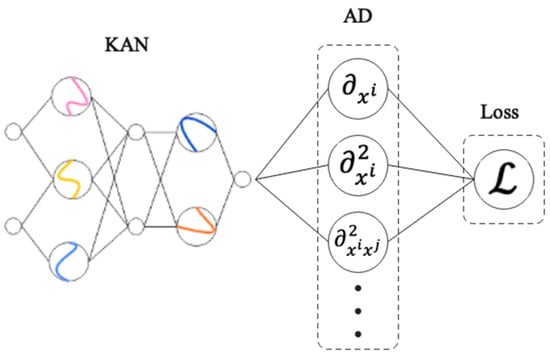

Integration with GNNs is exemplified by MKAN-MMI, which incorporates KAN into a masked graph autoencoder for medicine–microbe interaction prediction. KAN enhances weight learnability and interpretability in the prediction layer. It outperforms current leading models in capturing complex nonlinear mappings within sparse biological datasets [30]. The GNN encoder obtains node embeddings based on the input graph, while the decoder reconstructs the graph based on a set of known relationships between nodes. Figure 5 illustrates the MKAN-MMI model’s architecture.

Figure 5.

The MKAN-MMI model’s architecture.

Ablation studies validate the efficacy of these designs: KAN-MSA in KAN- improves PSNR compared to standard MSA [31]. As well as KAN layers in KANEFT [28] and HKAN [32] are critical for superior performance in hyperspectral image classification and fabric defect segmentation, respectively.

3. Applications of KAN in Scientific Computing and Engineering

3.1. Physics-Informed Neural Networks and Partial Differential Equations

In recent years, KANs have become increasingly integrated into physics-based machine learning frameworks for the solution of forward and inverse PDEs, which has led to the development of PIKANs, KINNs, and DeepOKANs [10]. By replacing traditional MLPs in PINNs and DeepONets, these models improve approximation capabilities for complex PDE solutions utilizing KANs’ unique activation functions constructed from basis functions such as B-splines, orthogonal polynomials (e.g., Chebyshev, Legendre, Jacobi), radial basis functions, and wavelets [2].

An important advantage of KAN-based frameworks is their interpretability. The KANs use nested spline bases as activation functions, which provide a natural interpretation of the PDE solution space [2]. A KAN-based AI4S framework, FiberKAN, has been proposed to discover and characterize the underlying dynamics of fiber optic systems [8]. With its trainable, transparent, and interpretable activation functions, it can explain and understand complicated systems. For stochastic PDEs, Bayesian inference integration (e.g., Hamiltonian Monte Carlo in PIKANs, Bayesian Higher Order ReLU-KANs) can also provide epistemic uncertainty estimates [10,33].

KAN-based models are also computationally efficient, requiring fewer parameters than MLPs. Accordingly, PIKANs for power system DAEs can achieve high accuracy at a 50% reduction in network size compared to conventional PINNs [34]. There have been demonstrations of accelerated training using JAX-based implementations of PIKANs, which have achieved up to 84 times faster training than previously implemented KANs [6]. Figure 6 shows the model structure. However, due to unoptimized libraries and complex activation functions, some architectures require longer training time per epoch.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of a PIKAN.

For fluid fields, KA-PointNet integrates KANs with PointNet in the irregular domains. The method predicts more accurately the pressure and velocity distribution along the surface of cylinders, resulting in more accurate calculations of lift and drag [35]. For turbulent flows, the AIVT method uses Chebyshev KANs to infer temperature and velocity fields from sparse experimental data in Rayleigh-Bénard convection, achieving high resolution, offering an additional approach to studying thermal turbulence [36]. In topology optimization, the KATO method uses convolutional KANs to minimize stress, achieving 10% lower maximum stress and 67% reduced computational time in comparison to conventional approaches [37]. Hybrid models like AL-PKAN, combining GRU encoding with KAN decoding and augmented Lagrangian loss, achieve higher accuracy than traditional PINNs for PDEs [38]. The results of the analysis for these models are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

KAN-based model analysis for scientific computing and engineering.

3.2. Dynamical Systems Modeling and Scientific Discovery

KANs have demonstrated significant potential in dynamical systems modeling and scientific discovery, with applications spanning dynamical systems identification, neural ODEs, and domain-specific scientific inquiry. In dynamical systems discovery, KANs address a critical limitation of traditional sparse optimization-based methods—their reliance on the often-unrealistic sparsity assumption that governing equations consist of only a few elementary functions [11]. As a general model-discovery framework, KANs decompose multivariate functions into sums of univariate functions, enabling accurate capture of complex nonlinear dynamics in systems lacking sparse structures. This capability extends to real-world scientific problems like modeling the AMOC fingerprint.

In the research of neural ODEs, KANs have been integrated into a specialized framework (KAN-ODEs) that replaces black-box MLPs with interpretable, parameter-efficient KAN structures [1]. Compared to traditional ODEs, KAN-ODEs offer higher accuracy, faster convergence, and superior interpretability. The framework works well in data-lean, nonlinear scenarios, successfully learning symbolic source terms and complete solution profiles for phenomena including wave propagation, shock formation, and the complex Schrödinger equation.

Within scientific discovery, KANs contribute to interpretable systems modeling by capturing relationships in domain-specific mechanisms. For example, the CardiOT model integrates KANs into a GNN framework for compound cardiotoxicity prediction, where KANs enhance both interpretability and accuracy [39]. This allows CardiOT to model relationships in cardiotoxicity mechanisms, with interpretability analyses (e.g., via EdgeSHAPer) linking KAN-learned weights to critical chemical effects, thereby advancing drug safety.

3.3. Load, Demand, and Environmental Forecasting

KAN-based models have demonstrated significant efficacy in power system load forecasting across diverse contexts. In district heating systems, the application of KAN enhanced heat load forecasting by dynamically adjusting spline function positions to capture local features and nonlinear relationships [40]. Based on real campus heating operational data, the model achieves a value of 0.98 and provides significant accuracy improvements over traditional methods at 3 h and 6 h timescales. For short-term load forecasting, a KAN model applied to a Swiss power system dataset outperformed MLPs and XGBoost by extracting periodic and random features [41]. Hybrid architectures integrating KAN with TCN, BiLSTM, and Transformer further improved electricity demand forecasting accuracy in the UK [29]. The TCN-KAN, Transformer-KAN, and BiLSTM-KAN models reduce RMSE and MAE while increasing compared to standalone LSTM/GRU models. In commercial buildings, KAN accurately predicted chiller energy consumption ( = 0.9465, RMSE = 6.1023) by modeling nonlinear dynamics using cubic spline basis functions and advanced parameter identification methods, outperforming ANN and hybrid metaheuristic-deep learning models [42].

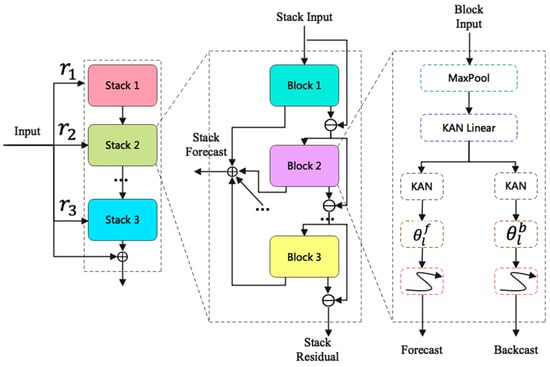

For DR prediction, the hybrid HITSKAN model combined KAN with N-HiTS to forecast day-ahead DR potential in residential buildings without requiring appliance-level data [43]. The HITSKAN architecture is shown in Figure 7. By leveraging KAN’s ability to model complex nonlinear multivariate functions and N-HiTS’s capacity to handle temporal dependencies via hierarchical interpolation and multi-rate sampling. HITSKAN outperformed state-of-the-art models (N-HiTS, TimesNet, Informer, TCN) across MAE, MAPE, RMSE, and sMAPE metrics in both the winter and summer seasons, with reduced computation time.

Figure 7.

The HITSKAN architecture.

In water resource management, KAN has advanced hydrological forecasting and flood risk assessment. For river discharge forecasting, KAN models outperformed Transformers in short-term (1–3 days) predictions across the Rhine, Danube, Elbe, and Oder rivers [44]. In FSM, novel KAN variants (Boubaker-KAN, Cheby-KAN, VietaPell-KAN) achieved an average overall accuracy of 92.5%, F1 score of 93.90%, and MCC of 0.866 in Iran’s Karun and Gorganrud basins, outperforming Random Forest and XGBoost [45]. These models, by utilizing polynomial basis functions, effectively capture basin-specific nonlinear relationships between flood conditioning factors and flood occurrences, with fewer parameters (~4000–21,000) and faster processing times (~10 s).

In environmental forecasting, KAN has enabled progress in cyanobacterial bloom monitoring, wind nowcasting, and weather impact assessment. For cyanobacterial monitoring in Canada’s Pigeon Lake, KAN classified shoreline sections into blooming hot spots/non-hot spots using Dynamic World land cover data (500 m radius), achieving a recall of 0.83 [46]. For wind nowcasting at Madeira International Airport, KAN improved GFS outputs by applying nonlinear transformations to correct topographic effects, reducing MSE by 48.5% [47]. Additionally, KAN predicted airport flight operation resilience under weather conditions at Xi’an Xianyang International Airport, achieving R2 = 99.8%, MAE = 0.0031, and MAPE = 2.3% by modeling relationships between weather factors (temperature, wind speed) and operational metrics [48]. Table 2 presents the analysis results of these models.

Table 2.

KAN-based model analysis for load, demand, and environmental forecasting.

4. Applications of KAN in Medical and Biological Domains

4.1. Medical Image Segmentation and Classification

KAN-integrated frameworks have been extensively developed for various medical imaging tasks, addressing challenges such as nonlinear feature modeling, boundary delineation, and noise robustness. In MRI cardiac segmentation, Li & Xu [53] proposed KS-Net, a semi-supervised U-shaped architecture incorporating KAN modules and a dual-stream perturbation strategy. Based on MyoPS 2020 and ACDC datasets, KS-Net is capable of segmenting the left ventricle, myocardium, and right ventricle with high Dice scores. Ablation studies confirm the KAN module’s critical role in enhancing nonlinear knowledge sharing and segmentation accuracy.

For lung nodule detection in CT scans, Jiang et al. [54] developed KansNet, which integrates a PKAB into a 3D CNN encoder–decoder network. Equipped with MSPCA and AMSF modules, KansNet outperformed state-of-the-art methods on the used dataset. Achieved a CPM of 90.32% and an AP of 89.19% on the LUNA16 dataset, with notable improvements in detecting small nodules (3–10 mm).

In medical image segmentation, two prominent frameworks have been introduced: KAC-Unet and MM-UKAN++. Lin et al. [55] proposed KAC-Unet, which combines KAN with an AGS and COT attention mechanism within a Unet architecture. It achieved Dice scores of 78.63%, 89.25%, and 92.55% on breast ultrasound (BUSI), dermoscopy (ISIC), and prostate MRI datasets, respectively. Zhang et al. [56] presented MM-UKAN++, replacing convolutional blocks with multilevel KAN layers and incorporating a FCSA mechanism. This framework delivered 69.42% IoU and 81.30% Dice, with real-time performance (40.8 FPS) and superior boundary delineation for regions of interest.

For computing tomography analysis, Chau et al. [57] applied KANs to the binary classification of QCT data for respiratory conditions induced by occupational cement dust exposure. Using 141 QCT-derived variables, their two-hidden-layer KAN model achieved 98.03% accuracy, outperforming traditional machine learning and deep learning models, with SHAP analysis identifying key features. Additionally, Amin et al. [58] introduced ViT-KAN, which integrates KAN layers into a Vision Transformer for lung EIT image reconstruction using CT scans as ground truth. This framework achieved a mean squared error of 0.0045 and a structural similarity index of 0.96, demonstrating robustness to Gaussian noise and potential for clinical lung function monitoring. Table 3 summarizes the key information from the literature.

Table 3.

Applications for medical image segmentation and classification.

4.2. Physiological Signal Processing and Health Monitoring

In EEG seizure detection, the KAN-based model has demonstrated efficacy in balancing accuracy and parameter efficiency. KAN–EEG, for example, employs spline-parametrized learnable activation functions to achieve high out-of-sample generalization across diverse datasets. With high AUROC values while requiring fewer network parameters and less training data compared to other models [62]. Another study comparing KAN with LSTM for EEG seizure prediction, however, found that the LSTM model performed better than KAN [63].

For PPG signal anomaly recognition, an architecture integrated parameterized learnable activation functions has been shown to strike a favorable balance between accuracy and parameter efficiency. Compared to the high-performing but parameter-heavy CNN-LSTM model (95% accuracy, 456,865 parameters), the CNN-KAN model achieved competitive performance (89% accuracy, AUC 95%) with substantially fewer parameters (127,206) [64].

In blood glucose prediction, the SugarNet model, which integrates frequency-domain learning with a Fourier Kolmogorov–Arnold network, excels at modeling individualized glucose dynamics. In comparison with state-of-the-art approaches, it demonstrated superior performance. Its balance of accuracy and parameter efficiency makes it promising for integration into diabetes management systems, including proactive glycemic control and autonomous insulin delivery [65].

Beyond these specific tasks, KANs have shown advantages in broader physiological signal-based health monitoring applications. For instance, in multi-task sitting posture recognition, a KAN model achieved higher average accuracy (97.03% upper body, 92.11% lower body) with fewer parameters (4320) than an MLP (93.87% upper body, 91.47% lower body; 7662 parameters) [66]. Providing evidence of KANs’ ability to provide accurate and efficient health monitoring. Additionally, methodological advances in KAN-based frameworks, such as PKAN for peptide function and activity prediction [67]. By eschewing linear weights and using learnable activation functions, the method is improved to handle multimodal peptide language information nuancedly. Table 4 summarizes and analyzes the models mentioned in this section.

Table 4.

KAN-based models in physiological signal processing and health monitoring.

5. KANs in Cybersecurity and Industrial Applications

5.1. Intrusion Detection Systems in IoT and Network Security

KANs and hybrid KAN models have demonstrated significant potential in IDS for IoT and network security, effectively addressing cyberattack detection, botnet classification, and anomaly detection. CKAN architectures, which integrate KAN layers into CNN frameworks (such as [73]) by replacing traditional MLP layers, have shown superior performance across multiple benchmark datasets. For example, one CKAN model outperformed conventional deep learning models like CNN, RNN, and Autoencoder in both accuracy and stability [13]. Similarly, another CKAN variant with attention mechanisms, designed for IoT and IoMT cybersecurity, exhibited enhanced accuracy on CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 datasets, though it faced limitations in memory usage and inference speed (88 samples/sec) due to spline-based kernel computations [74]. SNN-based intrusion detection is significantly more efficient [75]. Transformer-based KAN model, which replaced MLP layers in Transformers with KAN layers, further extended its performance, achieving high accuracy scores of 99.96% (RT-IoT2022), 98.43% (IoT23), and 99.27% (CICIoT2023) while maintaining effectiveness in detecting diverse attacks [9]. Figure 8 shows the model flowchart.

Figure 8.

TFKAN model flowchart.

In botnet classification, various KAN architectural variations (Original-KAN, Fast-KAN, Jacobi-KAN, Deep-KAN, Chebyshev-KAN) outperform traditional ML and DL models (e.g., MLP, CNN, LSTM, GRU) across datasets including N-BaIoT, IoT23, and IoT-BotNet. In particular, the Original-KAN is exceptional at capturing complex, nonlinear features present in IoT botnet traffic, resulting in higher accuracy and faster convergence [76]. For automotive cybersecurity, the DSC-KAN model, combined with SN-GAN for synthetic anomaly data generation, demonstrated robust detection of CAN bus attacks, outperforming CNNs and Vision Transformers while reducing computational cost [77]. Table 5 summarizes the key information from these studies.

Table 5.

KAN-based models for intrusion detection systems in IoT and network security.

5.2. Industrial Fault Diagnosis and Structural Monitoring

KANs have demonstrated significant potential in industrial fault diagnosis and structural monitoring, with applications spanning machinery components, power transformers, and power electronic systems, characterized by enhanced interpretability and suitability. In machinery component fault detection, KAN-based frameworks have been effectively applied to tool wear recognition and bearing fault diagnosis. A ViT that incorporates KAN (MTF-AViTK) can recognize tool wear states in manufacturing by converting 1D time series cutting signals into 2D MTF images in order to identify long-term dependencies. This data is then extracted using the Adapt-ViT module, and it is classified using a two-layer KAN. Validated on the PHM2010 dataset, MTF-AViTK achieved high classification accuracy with millisecond-level inference time, supporting real-time deployment in industrial settings [27]. Similarly, for bearing fault diagnosis, a KAN-based framework automates feature selection and hyperparameter optimization using shallow architectures, enabling lightweight deployment on resource-constrained edge devices [79]. This framework yielded perfect or near-perfect F1-Scores on the CWRU and MaFaulDa datasets.

In power transformer fault diagnosis, KANs have been tailored to address imbalanced real-world data. The approach employing the SyMProD oversampling technique to balance datasets and KAN layers with trainable spline function matrices for classification [80]. Compared to other models, achieved superior performance and improved interpretability.

For power electronic components, such as VSCs in power systems, DropKAN has emerged as a robust data-driven impedance modeling approach. DropKANs outperform conventional FNNs, LSTMs, and standard KANs in impedance identification accuracy, training/prediction times, and model simplicity [81]. Table 6 analyzes and summarizes the models mentioned in this section.

Table 6.

KAN-based models for industrial fault diagnosis and structural monitoring.

6. KANs in Image Processing and Vision Tasks

6.1. Hyperspectral Image Classification and Fusion

Through innovative architectural designs and superior nonlinear feature modeling capabilities, KANs have demonstrated substantial contributions to functions such as hyperspectral image classification, fusion, change detection, and spatiotemporal remote sensing. Jamali et al. developed a HybridKAN architecture combining 1D, 2D, and 3D KAN models, which achieved competitive classification accuracy compared to state-of-the-art CNN and Vision Transformer models, with faster convergence and improved feature separability visualized via t-SNE [82]. Similarly, Han et al. proposed KANEFT, a KAN-driven Enhanced Fusion Transformer that leverages KAN layers for linear/convolutional operations and a Multi-scale Fusion Learning Transformer module, achieving overall accuracies up to 99% on datasets like Indian Pines and Pavia University [28]. Firsov et al. introduced HyperKAN, replacing traditional layers with KAN blocks in architectures such as 1D-CNN, 3D-CNN, and transformers, leading to consistent accuracy improvements across seven hyperspectral datasets, enabling better modeling of complex patterns [7].

In hyperspectral image fusion, Zhu et al. proposed SFIGNet, a KAN-based spatial-frequency dual-domain implicit guided sampling network for HMIF. By integrating KAN with INR, SFIGNet conducts guided implicit sampling in spatial and frequency domains via SIGSU and FIGSU units, achieving superior spatial-spectral fidelity with a lightweight design [83].

In spatiotemporal remote sensing applications, Wang et al. proposed UKAN, a KAN-integrated U-Net, for flood inundation extraction from multisource data. UKAN outperformed U-Net and TransUNet on flood datasets, with KAN layers enhancing sensitivity to noise and low-contrast regions [84].

For change detection, a critical task in remote sensing, Liu et al. developed AEKAN, a superpixel-based AutoEncoder KAN for unsupervised multimodal change detection in HRSIs [85]. Using a Siamese KAN encoder with dual KAN decoders and hierarchical commonality loss, AEKAN outperformed state-of-the-art methods on five MCD datasets validated via ROC, PR curve, and metrics like overall accuracy and Kappa coefficient. In a study of HCD, Seydi et al. found that parameter numbers are less important in KAN-based models than nonlinear functions and model structure [12]. The Chebyshev-KAN model achieved an average overall accuracy of 97.35% across datasets, surpassing deep learning models like the Swin Transformer. Table 7 analyzes the models mentioned in this section.

Table 7.

KAN-based model for hyperspectral image classification and fusion.

6.2. Low-Light Image Enhancement and Deblurring

For low-light image enhancement, the KSID method introduces KANs into low-level vision tasks to model nonlinear dependencies between low-light and normal images [86]. Embedding a KAN-Block—composed of KAN-Layers with spline-based convolutional layers and learnable activation functions—into a U-Net denoising network within a diffusion model framework. KAN-Blocks are demonstrated to play a significant role in learning nonlinear degradation relationships through ablation studies. In image deblurring, the KT-Deblur framework integrates KANs with transformer architectures by replacing fixed activation functions with dynamically learnable ones based on KANs, enabling adaptation to various blur types [87]. Combining a U-Net architecture with a GAN framework and a UAFE module, it optimizes noise suppression and detail enhancement by combining neighborhood self-attention with linear self-attention. Experimental results on datasets demonstrate outperformance over state-of-the-art methods. According to the authors’ experimental results, the proposed KAN-based tracking method also demonstrates excellent effectiveness and robustness [88]. Figure 9 shows the model structure. Table 8 analyzes the models mentioned in this section.

Figure 9.

Structure of the KAN-based tracking model.

Table 8.

KAN-based models for low-light image enhancement and deblurring.

7. Challenges, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

KANs face a wide range of challenges in a number of critical areas. Robustness issues are evident, such as insufficient robustness in tool wear conditions recognition [27], susceptibility to adversarial attacks and noise with a risk of underperformance compared to MLPs in complex or noisy conditions [89], and persistent noise resilience concerns despite partial robustness demonstrations [11]. Ultrasound image segmentation suffers when regions of interest have low contrast with the surrounding tissues [56].

KAN replaces MLPs’ linear weights with learnable nonlinear basis functions. This offers significant theoretical advantages in terms of function approximation accuracy and interpretability. However, realizing these benefits often relies on optimizing the basis function parameters, which increases computational costs. As a result, KAN remains unsuitable for scenarios where the data itself demands substantial computational power. During application, additional considerations such as hardware configuration and energy consumption may be required.

Optimization instability poses another major hurdle. The loss of PIKANs increases sharply after grid extensions due to the re-initialization of the optimizer state [6]. When the KAN module is removed from models like KRN-DTI, performance may be significantly reduced [90]. PINNs are also prone to instability due to penalty factor inflation [38].

Scalability challenges remain; larger KANs may impede interpretability, KAN technology exhibits high computational complexity, and KAN-based topology optimization models, such as KATO, require large amounts of vRAM due to dense tensor representations, restricting high-resolution applications [37]. While variants like KAN-Mixer and convolutional KANs have been explored, the scalability results remain mixed.

Handling complex data geometries is problematic, with KANs struggling under adversarial attacks on complex geometries. US images present challenges like low contrast, fuzzy boundaries, and scale variations. Additionally, tuning hyperparameters, including grid sizes and spline orders, is critical, with neural network hyperparameters affecting optimization results significantly.

For future research, the summary of the aforementioned studies indicates that KAN’s training efficiency is low. This necessitates the optimization of basis functions and algorithms to improve computational efficiency. Research into lightweight KAN variants suitable for edge devices holds significant practical value, as it advances their real-time application to intelligent sensors, edge controllers, and similar equipment. Moreover, the current selection and combination of basis functions in KAN remain relatively fixed. Future research could explore dynamic adaptive mechanisms for basis functions to enhance multi-scale, complex nonlinear feature capture. Further exploration of fusion innovation between different model architectures may be pursued, leveraging their respective strengths to construct high-performance frameworks tailored to specific domains.

8. Conclusions

The KAN framework is underpinned by the Kolmogorov–Arnold representation theorem as its core theoretical foundation, whereas MLP is constructed upon the universal approximation theorem. Based on the Kolmogorov–Arnold Representation Theorem, which states that any multivariate continuous function can be decomposed into a finite superposition of univariate functions, the core of the KAN architecture lies in the combined learning of univariate functions. Based on the Universal Approximation Theorem, a feedforward network with a single hidden layer and a nonlinear activation function can approximate any continuous function on a compact set with arbitrary precision. This provides the theoretical basis for MLP’s ability to approximate functions through fixed nonlinear activation combined with weight adjustment. Among diverse function classes, including smooth functions and those derived from physical equations, KAN demonstrates distinct advantages owing to its unique structural design. With this structural innovation, nonlinear transformation and weight parametrization are integrated into unified layers. This leads to improved functional representation capability, flexibility, and interpretability. It has been shown that KANs extended with adaptive basis functions, hybridization with Transformers, CNNs, RNNs, and graph structures improve accuracy and parameter efficiency in a variety of domains. These domains include signal processing, physical modeling, and cybersecurity. Ablation analysis shows that LKAN can improve deep learning models with a reduction in parameters [91].

The use of KANs to diagnose and monitor industrial faults exploits their interpretability and efficiency for real-time condition assessments of machinery, transformers, and power electronics. There are also numerous image processing applications, such as medical image analysis, low-light image enhancement, etc. There are, of course, applications in other fields, such as stock price forecasting [92] and dam deformation prediction [93]. For quantum architecture search, KANs demonstrated 2× to 5× higher success probability than MLPs in preparing Bell and GHZ states under noiseless conditions and better fidelity in noisy environments [94]. In fraud detection, KANs’ hierarchical structure provides a more effective and interpretable solution over MLPs, with Efficient KAN achieving a 100% F1 score and 0.1 s detection time [95]. In [96], CoxKAN is described as a Cox proportional hazards KAN designed for high-performance, interpretable survival analysis. Based on real datasets, CoxKAN consistently outperformed the traditional Cox proportional hazards model. Multi-exit KAN is another interesting model [97]. By including a prediction branch at every layer, the network can make accurate forecasts at multiple depths at the same time. It provides scientists with a practical method for high performance and interpretability. As the aforementioned examples illustrate, KAN can be used across a wide range of fields and generate valuable results.

According to comparative evaluations, KANs have many aspects of outstanding performance compared to mainstream neural architectures in terms of accuracy, parameter efficiency, interpretability, and training dynamics, although there is a trade-off in computational complexity and occasional optimization instability. It should be noted that some studies are based on datasets collected by the authors themselves. This may pose obstacles for researchers who need to reproduce the results. In summary, KANs are theoretically based and practically versatile neural networks with demonstrated applications in scientific computing, engineering, medicine, environmental, and cybersecurity. For KANs to fully realize their potential in complex function approximation and interpretable machine learning, continuous innovations and systematic investigation into their limitations are essential.

Author Contributions

Z.W. designed the manuscript structure and completed the integration of the first content version. X.L. organized the KAN model architecture and variations. D.W. finished the part on applications of KAN in scientific computing and engineering. C.C. completed the part on applications of KAN in the medical and biological domains, and X.H. contributed the part on KANs in image processing and vision tasks. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Doctoral Research Fund Project of Guangdong University of Science and Technology, grant number GKY-2025BSQDK-29.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| KAN | Kolmogorov–Arnold network |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MHA | Multi-Head Attention |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| MMI | Medicine–Microbe Interaction |

| GAE | Graph Auto Encoder |

| PDE | Partial Differential Equation |

| DAE | Differential-Algebraic Equation |

| AIVT | Artificial Intelligence Velocimetry–Thermometry |

| ODE | Ordinary Differential Equation |

| AMOC | Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| DR | Demand Response |

| SE | Sensitivity |

| SP | Specificity |

| ACC | Accuracy |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| AUC | Area Under Curve |

| AUP | Areas Under PR Curve |

| MOTP | Multiple Object Tracking Precision |

| MOTA | Multiple Object Tracking Accuracy |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity |

| LPIPS | Learned Perceptual Image Block Similarity |

| FID | Fréchet Inception Distance |

| OA | Overall Accuracy |

| PR | Precision–Recall |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| Ka | Kappa coefficient |

| MAX | Maximum error |

| KGE | Kling-Gupta Efficiency |

| MARD | Mean Absolute Relative Difference |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Curve |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| FSM | Flood Susceptibility Mapping |

| MCC | Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

| GFS | Global Forecast System |

| PKAB | Partial Kan Attention Block |

| MSPCA | Multi-Slice Partition Channel Priority Attention |

| AMSF | Adaptive Multi-Scale Feature Fusion |

| CPM | Competition Performance Metric |

| AP | Average Precision |

| AGS | Adaptive Group Strategy |

| FCSA | Frequency-Channel Spatial Attention |

| EIT | Electrical Impedance Tomography |

| IDS | Intrusion Detection System |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| US | Ultrasound |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| MTF | Markov Transition Field |

| VSC | Voltage-Source Converter |

| FNN | Feedforward Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory network |

| HMIF | Hyperspectral and Multispectral Image Fusion |

| INR | Implicit Neural Representation |

| HRSI | Heterogeneous Remote Sensing Image |

| HCD | Hyperspectral Change Detection |

| UAFE | Union Attention Feature Extraction |

| HSI | HyperSpectral Image |

| FCN-KAN | Fully Connected Network KAN |

| RBF-KAN | Radial Basis Function KAN |

| CKAN | Convolutional Kolmogorov–Arnold Network |

| PIKAN | Physics-Informed KAN |

| KINN | Kolmogorov–Arnold-Informed Neural Network |

| DeepOKAN | Deep Operator KAN |

| PINN | Physics-Informed Neural Network |

| DeepONet | Deep Operator Network |

| DSC-KAN | Depthwise Separable Convolutional KAN |

| SN-GAN | Spectral Normalization GAN |

| SAR | Success Attack Rate |

| STD | Standard Deviation |

| FLOP | Floating-Point Operation |

| LKAN | Linear KAN |

| HKAN | Hybrid Kolmogorov–Arnold Network |

| MSA | Multi-headed Self-Attention |

| KANEFT | Kolmogorov–Arnold Network-based Enhanced Fusion Transformer |

References

- Koenig, B.C.; Kim, S.; Deng, S. KAN-ODEs: Kolmogorov-Arnold Network Ordinary Differential Equations for Learning Dynamical Systems and Hidden Physics. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 432, 117397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Bai, J.; Anitescu, C.; Eshaghi, M.S.; Zhuang, X.; Rabczuk, T.; Liu, Y. Kolmogorov–Arnold-Informed neural network: A physics-informed deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems based on Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2025, 433, 117518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wang, B.; Lei, C.; Zhou, K.; Chen, X. Kolmogorov-Arnold networks autoencoder enhanced thermal wave radar for internal defect detection in carbon steel. Opt. Laser Eng. 2025, 187, 108879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, A.A. fkan: Fractional kolmogorov–arnold networks with trainable jacobi basis functions. Neurocomputing 2025, 623, 129414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Vaidya, S.; Ruehle, F.; Halverson, J.; Soljačić, M.; Hou, T.Y.; Tegmark, M. Kan: Kolmogorov-arnold networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.19756. [Google Scholar]

- Rigas, S.; Papachristou, M.; Papadopoulos, T.; Anagnostopoulos, F.; Alexandridis, G. Adaptive training of grid-dependent physics-informed kolmogorov-arnold networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 176982–176998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firsov, N.; Myasnikov, E.; Lobanov, V.; Khabibullin, R.; Kazanskiy, N.; Khonina, S.; Butt, M.A.; Nikonorov, A. HyperKAN: Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks Make Hyperspectral Image Classifiers Smarter. Sensors 2024, 24, 7683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, M.; Luo, X.; Yu, Z.; Meng, Y.; Wang, D. FiberKAN: Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks for Nonlinear Fiber Optics. J. Light. Technol. 2025, 43, 7083–7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, I.A.; Abd Elaziz, M.; Aseeri, A.O.; Zied, H.S.; Abdellatif, A.G. TFKAN: Transformer based on Kolmogorov–Arnold networks for intrusion detection in IoT environment. Egypt. Inform. J. 2025, 30, 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, K.; Toscano, J.D.; Wang, Z.; Zou, Z.; Karniadakis, G.E. A comprehensive and FAIR comparison between MLP and KAN representations for differential equations and operator networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 431, 117290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, S.; Moradi, M.; Bollt, E.M.; Lai, Y.C. Data-driven model discovery with Kolmogorov-Arnold networks. Phys. Rev. Res. 2025, 7, 023037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seydi, S.T.; Sadegh, M.; Chanussot, J. Kolmogorov-arnold network for hyperspectral change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5505515. [Google Scholar]

- Abd Elaziz, M.; Fares, I.A.; Aseeri, A.O. Ckan: Convolutional kolmogorov–arnold networks model for intrusion detection in iot environment. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 134837–134851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abueidda, D.W.; Pantidis, P.; Mobasher, M.E. Deepokan: Deep operator network based on kolmogorov arnold networks for mechanics problems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2025, 436, 117699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakolkaran, P.; Guo, Y.; Saini, S.; Peirlinck, M.; Alheit, B.; Kumar, S. Can kan cans? input-convex kolmogorov-arnold networks (kans) as hyperelastic constitutive artificial neural networks (cans). Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2025, 443, 118089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollósi, J.; Ballagi, Á.; Kovács, G.; Fischer, S.; Nagy, V. Detection of bus driver mobile phone usage using kolmogorov-arnold networks. Computers 2024, 13, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livieris, I.E. C-kan: A new approach for integrating convolutional layers with kolmogorov–arnold networks for time-series forecasting. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wang, D.; Cao, C.; Xie, H.; Zhou, T.; Cao, C. GSA-KAN: A hybrid model for short-term traffic forecasting. Mathematics 2025, 13, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Lu, H.; Paoletti, M.E.; Su, H.; Jing, W.; Haut, J.M. KACNet: Kolmogorov-Arnold Convolution Network for Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5506514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.U.; Grolinger, K. Kolmogorov–Arnold recurrent network for short term load forecasting across diverse consumers. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zeng, Q.; Lu, L.; Abdul, W. Intelligent Semantic Communication System Based on Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks Driven by Dynamic Terminal-Side Computing Power Network. Electronics 2024, 13, 4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, E.; Ramakrishnan, D.; Gleyzer, S. Sinekan: Kolmogorov-arnold networks using sinusoidal activation functions. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 7, 1462952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zequera, R.A.G.; Rassolkin, A.; Vaimann, T.; Kallaste, A. Kolmogorov-Arnold networks for algorithm design in battery energy storage system applications. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 2664–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaushenova, A.; Kuznetsov, O.; Nurpeisova, A.; Ongarbayeva, M. Implementation of Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks for Efficient Image Processing in Resource-Constrained Internet of Things Devices. Technologies 2025, 13, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Luo, W.; Yin, S.; Zhang, J.; Liang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, S. Interpretable State Estimation in Power Systems Based on the Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks. Electronics 2025, 14, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lin, K.; Zhou, A. The KAN-MHA model: A novel physical knowledge based multi-source data-driven adaptive method for airfoil flow field prediction. J. Comput. Phys. 2025, 528, 113846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Meng, Y.; Yin, S.; Liu, X. Tool wear state recognition study based on an MTF and a vision transformer with a Kolmogorov-Arnold network. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 228, 112473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Jiang, F.; Wen, S.; Tian, T. Kolmogorov-Arnold Network-based Enhanced Fusion Transformer for Hyperspectral Image Classification. Inform. Sci. 2025, 717, 122323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, L.; Yan, W. Integrating Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks with Time Series Prediction Framework in Electricity Demand Forecasting. Energies 2025, 18, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, M.; Yuan, S.; Zhuo, L.; Chen, T.; Gao, J. MKAN-MMI: Empowering traditional medicine-microbe interaction prediction with masked graph autoencoders and KANs. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1484639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brateanu, A.; Balmez, R.; Orhei, C.; Ancuti, C.; Ancuti, C. Enhancing low-light images with kolmogorov–arnold networks in transformer attention. Sensors 2025, 25, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ye, P.; Cui, S.; Zhu, P.; Liu, J. HKAN: A Hybrid Kolmogorov–Arnold Network for Robust Fabric Defect Segmentation. Sensors 2024, 24, 8181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giroux, J.; Fanelli, C. Uncertainty quantification with Bayesian higher order ReLU-KANs. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2025, 6, 015073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, H.; Li, F. Physics-informed kolmogorov-arnold networks for power system dynamics. IEEE Open Access J. Power Energy 2025, 12, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashefi, A. Kolmogorov–Arnold PointNet: Deep learning for prediction of fluid fields on irregular geometries. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2025, 439, 117888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, J.D.; Käufer, T.; Wang, Z.; Maxey, M.; Cierpka, C.; Karniadakis, G.E. AIVT: Inference of turbulent thermal convection from measured 3D velocity data by physics-informed Kolmogorov-Arnold networks. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Jelovica, J. KATO: Neural-Reparameterized Topology Optimization Using Convolutional Kolmogorov-Arnold Network for Stress Minimization. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Eng. 2025, 126, e70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, T.; Zhang, W. Physics-informed neural networks with hybrid Kolmogorov-Arnold network and augmented Lagrangian function for solving partial differential equations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Du, Z.; Zhuo, L.; Fu, X.; Cao, D.; Xie, B.; Li, K. CardiOT: Towards interpretable drug cardiotoxicity prediction using optimal transport and Kolmogorov-arnold networks. IEEE J. Biomed. Health 2024, 29, 1759–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yang, J.; Cui, X.; Peng, M.; Liang, X. A novel adaptive adjustment Kolmogorov-Arnold network for heat load prediction in district heating systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 274, 126552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Geng, H. A novel interpretable short-term load forecasting method based on kolmogorov-arnold networks. IEEE T. Power Syst. 2024, 40, 1180–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M.H.; Mustaffa, Z.; Saealal, M.S.; Saari, M.M.; Ahmad, A.Z. Utilizing the Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks for chiller energy consumption prediction in commercial building. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muqtadir, A.; Li, B.; Ying, Z.; Songsong, C.; Kazmi, S.N. Day-ahead demand response potential prediction in residential buildings with HITSKAN: A fusion of Kolmogorov-Arnold networks and N-HiTS. Energy Build. 2025, 332, 115455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, F.; Zhu, S.; Di Nunno, F. Advanced streamflow forecasting for Central European Rivers: The cutting-edge Kolmogorov-Arnold networks compared to Transformers. J. Hydrol. 2024, 645, 132175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seydi, S.T.; Sadegh, M. Novel Kolmogorov-Arnold network architectures for accurate flood susceptibility mapping: A comparative study. J. Hydrol. 2025, 661, 133553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Luna, B.A.; Milne, R.; Wang, H. Cyanobacteria hot spot detection integrating remote sensing data with convolutional and Kolmogorov-Arnold networks. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 960, 178271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, D.; Mendonça, F.; Mostafa, S.S.; Morgado-Dias, F. On the use of kolmogorov–arnold networks for adapting wind numerical weather forecasts with explainability and interpretability: Application to madeira international airport. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 105008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wang, J.; Li, R. The Importance of Weather Factors in the Resilience of Airport Flight Operations Based on Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks (KANs). Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Github. 2017. Available online: https://github.com/dafrie/lstm-load-forecasting/tree/master (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Marino, D.L.; Amarasinghe, K.; Manic, M. Building energy load forecasting using deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the IECON 2016-42nd Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Florence, Italy, 23–26 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kaggle. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/chillerenergy/chiller-energy-data (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Barker, S.; Mishra, A.; Irwin, D.; Cecchet, E.; Shenoy, P.; Albrecht, J. Smart*: An Open Data Set and Tools for Enabling Research in Sustainable Homes. In Proceedings of the 2012 Workshop on Data Mining Applications in Sustainability, Beijing, China, 23–26 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Xu, X. Semi-Supervised Learning with Kolmogorov-Arnold Network for MRI Cardiac Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 2515311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Li, Y.; Luo, H.; Zhang, C.; Du, H. KansNet: Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks and multi slice partition channel priority attention in convolutional neural network for lung nodule detection. Biomed. Signal Process. 2025, 103, 107358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Hu, R.; Li, Z.; Lin, Q.; Zeng, K.; Wu, X. KAC-Unet: A Medical Image Segmentation with the Adaptive Group Strategy and Kolmogorov-Arnold Network. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 5015413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Huang, H.; Shen, Y.; Sun, M. MM-UKAN++: A Novel Kolmogorov-Arnold Network Based U-shaped Network for Ultrasound Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2025, 72, 498–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, N.K.; Kim, W.J.; Lee, C.H.; Chae, K.J.; Jin, G.Y.; Choi, S. Quantitative computed tomography imaging classification of cement dust-exposed patients-based Kolmogorov-Arnold networks. Artif. Intell. Med. 2025, 167, 103166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, I.; Shi, S.; AlMarzouqi, H.; Aung, Z.; Ahmed, W.; Liatsis, P. Kolmogorov-arnold vision transformer for image reconstruction in lung electrical impedance tomography. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2025, 6, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeimarani, B.; Costa, M.G.F.; Nurani, N.Z.; Bianco, S.R.; Pereira, W.C.D.A.; Costa Filho, C.F.F. Breast lesion classification in ultrasound images using deep convolutional neural network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 133349–133359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codella, N.C.; Gutman, D.; Celebi, M.E.; Helba, B.; Marchetti, M.A.; Dusza, S.W.; Kalloo, A.; Liopyris, K.; Mishra, N.; Kittler, H.; et al. Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection: A challenge at the 2017 international symposium on biomedical imaging (isbi). In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018), Washington, DC, USA, 4–7 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Dou, Q.; Yu, L.; Heng, P.A. MS-Net: Multi-site network for improving prostate segmentation with heterogeneous MRI data. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 2713–2724. [Google Scholar]

- Herbozo Contreras, L.F.; Cui, J.; Yu, L.; Huang, Z.; Nikpour, A.; Kavehei, O. KAN–EEG: Towards replacing backbone–MLP for an effective seizure detection system. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2025, 12, 240999. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.; Zhao, X.; Wu, W.; Dai, J.; Gu, X.; Noreen, A. Long Short-Term Memory and Kolmogorov Arnold Network Theorem for epileptic seizure prediction. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intel. 2025, 154, 110757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrab, A.; Lapenna, M.; Zanchetta, F.; Simonetti, A.; Faglioni, G.; Malagoli, A.; Fioresi, R. Kolmogorov–Arnold and Long Short-Term Memory Convolutional Network Models for Supervised Quality Recognition of Photoplethysmogram Signals. Entropy 2025, 27, 326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Connor, C. SugarNet: Personalized blood glucose forecast with a Fourier Kolmogorov–Arnold network. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 280, 127476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneros-Prado, D.; Cabañero-Gómez, L.; Johnson, E.; González, I.; Fontecha, J.; Hervás, R. A comparison between Multilayer Perceptrons and Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks for multi-task classification in sitting posture recognition. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 180198–180209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fu, X.; Ye, X.; Sakurai, T.; Zeng, X.; Liu, Y. PKAN: Leveraging Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks and Multi-modal Learning for Peptide Prediction with Advanced Language Models. IEEE J. Biomed. Health 2025, 29, 7000–7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Diabetes Federation. Simglucose v0.2.1. Available online: https://www.diabetesatlas.org/ (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- Zhao, Q.; Zhu, J.; Shen, X.; Lin, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Cao, B.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Rao, W.; et al. Chinese diabetes datasets for data-driven machine learning. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prioleau, T.; Bartolome, A.; Comi, R.; Stanger, C. DiaTrend: A dataset from advanced diabetes technology to enable development of novel analytic solutions. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Wang, L.; Fu, X.; Xia, C.; Zeng, X.; Zou, Q. ITP-Pred: An interpretable method for predicting, therapeutic peptides with fused features low-dimension representation. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UniProt, C. UniProt: A hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D204–D212. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Ghaleb, F.A. An attention-based convolutional neural network for intrusion detection model. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 43116–43127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zainal, A.; Siraj, M.M.; Ghaleb, F.A.; Hao, X.; Han, S. An intrusion detection model based on Convolutional Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Ghaleb, F.A.; Zainal, A.; Siraj, M.M.; Lu, X. An efficient intrusion detection model based on convolutional spiking neural network. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, P.H.; Le, T.D.; Dinh, T.D.; Dai Pham, V. Classifying IoT Botnet Attacks with Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks: A Comparative Analysis of Architectural Variations. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 16072–16093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, Y.; Hu, H.; Chen, Y.; Yu, F. A lightweight intrusion detection approach for CAN bus using depthwise separable convolutional Kolmogorov Arnold network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HCRL. Car-Hacking Dataset. Available online: https://ocslab.hksecurity.net/Datasets/CAN-intrusion-dataset (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Rigas, S.; Papachristou, M.; Sotiropoulos, I.; Alexandridis, G. Explainable Fault Classification and Severity Diagnosis in Rotating Machinery Using Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks. Entropy 2025, 27, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, T.W.; Gomes, F.V.; de Lima, E.R.; Filho, J.C.; Meloni, L.G. Kolmogorov–Arnold Network in the Fault Diagnosis of Oil-Immersed Power Transformers. Sensors 2024, 24, 7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Mohamed, Y.A.R.I. Dropout Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks: A Novel Data-Driven Impedance Modeling Approach for Voltage-Source Converters. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2025, 6, 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, A.; Roy, S.K.; Hong, D.; Lu, B.; Ghamisi, P. How to learn more? Exploring Kolmogorov–Arnold networks for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Song, X.; Li, Y.; Deng, S.; Zhang, T. A spatial-frequency dual-domain implicit guidance method for hyperspectral and multispectral remote sensing image fusion based on Kolmogorov–Arnold Network. Inform. Fusion 2025, 123, 103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L. FloodKAN: Integrating Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks for Efficient Flood Extent Extraction. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Xu, J.; Lei, T.; Wang, Y.; Du, X.; Zhang, W.; Lv, Z.; Gong, M. AEKAN: Exploring Superpixel-based AutoEncoder Kolmogorov-Arnold Network for Unsupervised Multimodal Change Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 63, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, A.; Xue, M.; He, J.; Song, C. KAN see in the dark. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2025, 32, 891–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Li, Z.; Lv, Q.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, K. KT-Deblur: Kolmogorov–Arnold and Transformer Networks for Remote Sensing Image Deblurring. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Ji, J.; Jing, R.; Su, H.; Wang, S.; Guo, A. Reynolds rules in swarm fly behavior based on KAN transformer tracking method. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahum, A.D.M.; Shang, Z.; Hong, J.E. How resilient are kolmogorov–arnold networks in classification tasks? A robustness investigation. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, J.; Liu, X.; Xu, P.; Shen, X.; Pan, C.; Zhang, W.; Liu, W.; Han, H. KRN-DTI: Towards accurate drug-target interaction prediction with Kolmogorov-Arnold and residual networks. Methods 2025, 240, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherednichenko, O.; Poptsova, M. Kolmogorov–Arnold networks for genomic tasks. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryono, A.T.; Sarno, R.; Anggraini, R.N.E.; Sungkono, K.R. Permuted Temporal Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks for Stock Price Forecasting using Generative Aspect Based Sentiment Analysis. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 178672–178689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Liu, X.; Wei, J.; Ai, X.; Li, Z.; He, H. Predicting the deformation of a concrete dam using an integration of long short-term memory (LSTM) networks and Kolmogorov–arnold networks (KANs) with a dual-stage attention mechanism. Water 2024, 16, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, A.; Sarkar, A.; Sadhu, A. Kanqas: Kolmogorov-arnold network for quantum architecture search. EPJ Quantum Technol. 2024, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Kang, H.; Kim, H. Robust credit card fraud detection based on efficient Kolmogorov-Arnold network models. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 157006–157020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knottenbelt, W.; McGough, W.; Wray, R.; Zhang, W.Z.; Liu, J.; Machado, I.P.; Gao, Z.; Crispin-Ortuzar, M. Coxkan: Kolmogorov-arnold networks for interpretable, high-performance survival analysis. Bioinformatics 2025, 41, btaf413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagrow, J.; Bongard, J. Multi-Exit Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks: Enhancing accuracy and parsimony. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.03302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.