Finite-Time Tracking Control of Multi-Agent System with External Disturbance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries and Problem Statement

2.1. Notations

2.2. Preliminary Results

- 1.

- 2.

- (i)

- Let be a non-negative, absolutely continuous function defined on the interval , and satisfy the differential inequality for almost every .where and are non-negative, summable functions on . Then, for all , the following inequality holds:for all

- (ii)

- In particular, ifthen

3. Finite-Time Boundedness Analysis

3.1. Adaptive Distributed Finite-Time Observer

| Algorithm 1 Adaptive Distributed Finite-Time Observer (for Theorem 1) |

|

3.2. Special Case: The Reference Input Is Known

3.3. Finite-Time Tracking Consensus

3.3.1. Finite-Time Boundedness Analysis

| Algorithm 2 FTB Verification for Sliding Mode Dynamics (for Theorem 2) |

|

3.3.2. Finite-Time Tracking Protocol Design

| Algorithm 3 Finite-Time Tracking Control (for Theorem 3) |

|

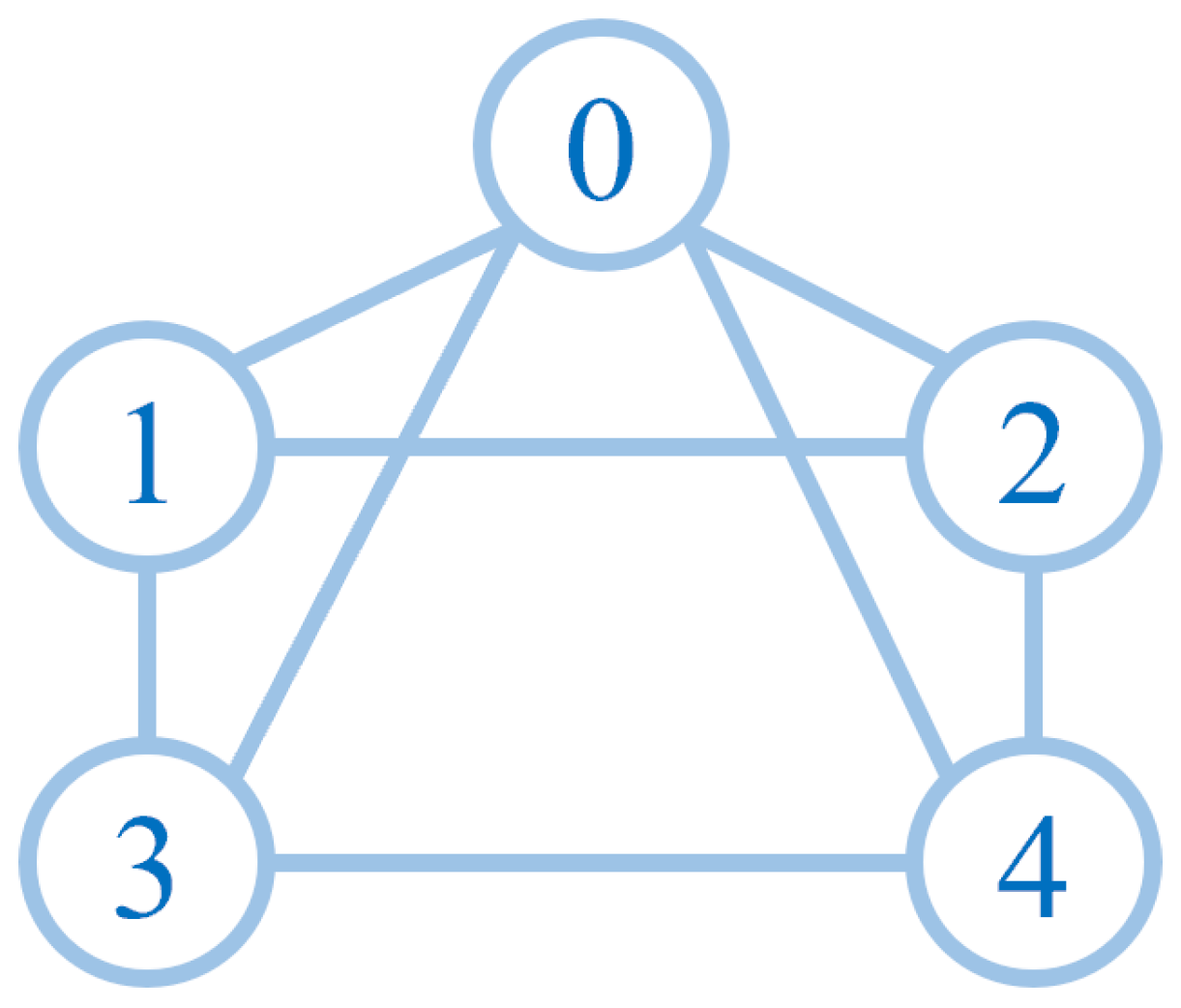

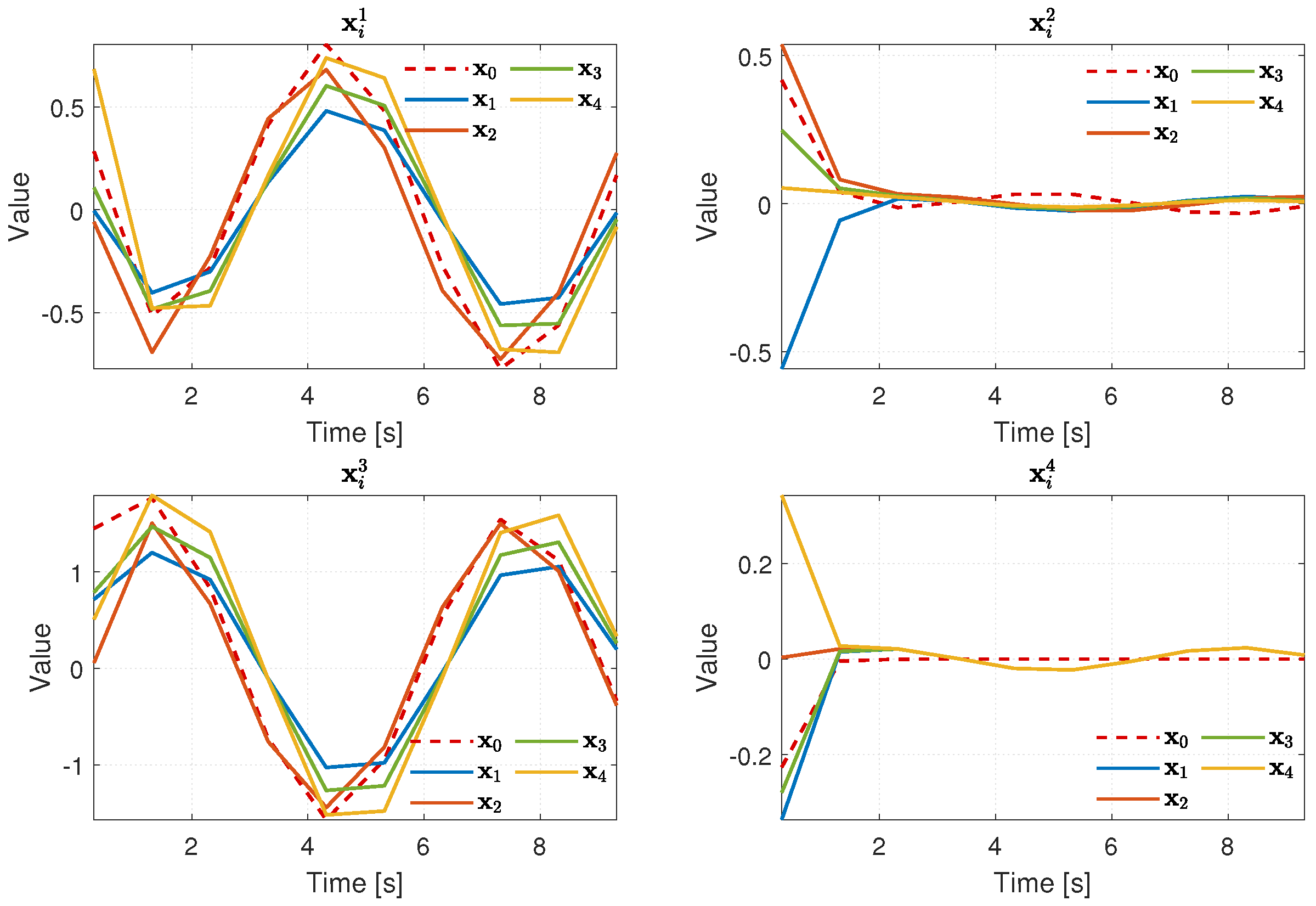

4. Numerical Example

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Derakhshannia, M.; Moosapour, S. Adaptive arbitrary time synchronisation control for fractional order chaotic systems with external disturbances. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2024, 56, 1540–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Pacheco, J.; Volos, C.; Serrano, F.; Jafari, S.; Kengne, J.; Rajagopal, K. Stabilization and synchronization of a complex hidden attractor chaotic system by backstepping technique. Entroy 2021, 23, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, V.; Kingni, S.; Volos, C.; Jafari, S.; Kapitaniak, T. A simple three-dimensional fractional-order chaotic system without equilibrium: Dynamics, circuitry implementation, chaos control and synchronization. AEU Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2017, 78, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Yang, B.; Yee, H. A multi-player game equilibrium problem based on stochastic variational inequalities. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 26035–26048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Xiong, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Zhou, S.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X. Trajectory tracking closed-loop cooperative control of manipulator neural network and terminal sliding model. Symmtry 2025, 17, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Beard, R. Consensus seeking in multi-agent systems under dynamically changing interaction topologies. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2005, 50, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Hu, J.; Gao, L. Tracking control for multi-agent consensus with an active leader and variable topology. Automatica 2006, 42, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Duan, Z.; Chen, G.; Hang, L. Consensus of multi-agent systmes and synchronization of complex networks: A unified viewpoint. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2010, 57, 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Duan, Z.; Lewis, F. Distributed robust consensus control of multi-agent systems with heterogeneous matching uncertainties. Automatica 2014, 50, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Wen, B.; Zhang, H.; Xue, F. Leader-following consensus control of multiple nonholomomic mobile robots: An iterative learning adaptive control scheme. J. Frankl. Institue 2022, 359, 1018–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrampour, B.; Asemani, M.H.; Dehghani, M.; Tavazoei, M. Consensus control of incommensurate fractional-order multi-agent systems: An LMI approach. J. Frankl. Institue 2023, 360, 4031–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhu, X.; Chen, W. Leader-following consensus problem with an accelerated motion leader. Int. J. Control. Autom. Syst. 2012, 10, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, X.; Lin, P.; Ren, W. Consensus of linear multi-agent systems with reduced-order observer-based protocols. Syst. Control Lett. 2011, 60, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, S.; Huang, W.; Gao, L. Leader-following consensus of discrete-time multi-agent systems with observer-based protocols. Neurocomputing 2013, 118, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gao, L. Intermittent observer-based consensus control for multi-agent systems with switching topologies. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2016, 47, 1891–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, R.; Murray, R. Consensus problems in networks of agents with switching topology and time-delays. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2004, 49, 1520–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Boyd, S. Fast linear iterations for distributed averaging. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2004, 53, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Luo, X.; Wand, J.; Guan, X. Finite-time consensus of nonlinear multi-agent system with precribed performance. Nonlinear Dyn. 2018, 91, 2397–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Yazdanpanah, M. Finite time consensus of nonlinear multi-agent systems in the presence of communication time delays. Eur. J. Control 2020, 53, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Mazouchi, M.; Modares, H.; Wand, X. Finite-time adaptive output synchronization of uncertain nonlinear heterogeneous multi-agent systems. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2021, 31, 9416–9435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Cheng, D. Leader-following consensus of multi-agent systems under fixed and switching topologies. Syst. Control Lett. 2010, 50, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIBsat, M.; Yaz, E. Robust and resilient finite-time control of a class of continuous-time nonlinear systems. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2012, 45, 331–352. [Google Scholar]

- EIBsat, M.; Yaz, E. Robust and resilient finite-time bounded control of a class of discrete-time uncertain nonlinear systems. Automatica 2013, 49, 2292–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; He, S. Observer-based finite-time passive control for a class of uncertain time-delayed Lipschitz nonlinear systems. Transations Inst. Meas. Control 2014, 36, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, W. Finite-time stability and stabilization of Iinear It ô stochastic systems with state and control dependent noise. Asian J. Control 2013, 15, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Ariola, M.; Dorato, P. Finite-time control of linear systems subject to parametric uncertainties and disturbances. Automatica 2011, 37, 1459–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D. Matrix Mathematics: Theory, Facts, and Formulas; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Wang, J.; Soh, Y. An adaptive technique for robust diagnosis of faults with independent effects on system outputs. Int. J. Control 2002, 75, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Yu, X.; Shirinzadeh, B.; Man, Z. Continuous finite-time control for robotic manipulators with terminal sliding mode. Automatica 2005, 41, 1957–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, C. Partial Differential Equations, 2nd ed.; American Mathematican Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y.; Ho, D.; Lam, J. Robust integral sliding mode control for uncertain stochastic systems with time-varying delay. Automatica 2005, 41, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description | Application Scenario |

|---|---|---|

| / | Represent the set of real numbers and complex numbers, respectively. | Defining the numerical domain of variables or matrix elements. |

| I | Identity matrix with dimensions compatible with other matrices in the operation. | Matrix operations (e.g., matrix multiplication, inverse matrix calculation). |

| (where S is a symmetric matrix) | Indicates that S is a positive definite matrix, meaning all eigenvalues of S are positive real numbers. | Determination of matrix properties (e.g., analysis of quadratic form positive definiteness). |

| (where S is a symmetric matrix) | Indicates that S is a negative definite matrix, meaning all eigenvalues of S are negative real numbers. | Determination of matrix properties. |

| / (where all eigenvalues of S are real numbers) | Represent the maximum eigenvalue and minimum eigenvalue of matrix S, respectively. | Eigenvalue analysis (e.g., matrix stability, spectral radius calculation). |

| / | Denote the transpose and conjugate transpose of a matrix or vector, respectively. | Matrix/vector operations (e.g., inner product calculation, definition of Hermitian matrices). |

| Generates a diagonal matrix (elements on the diagonal are those inside the parentheses, and off-diagonal elements are 0). | Matrix construction (e.g., constructing diagonalized matrices, sign matrices). | |

| ⊗ | Kronecker product, which satisfies two properties: 1. 2. If and , then . | High-dimensional matrix operations (e.g., tensor product, block matrix construction). |

| Sign matrix, defined as , where is the sign function (1 for positive numbers, −1 for negative numbers, and 0 for zero). | Matrix construction related to vector signs (e.g., error sign analysis). | |

| / | Represent the Euclidean norm (2-norm) and 1-norm, respectively. | Norm calculation of vectors or matrices (e.g., error measurement, convergence analysis). |

| ⋆ | Used in symmetric block matrices to represent elements below the main diagonal (symmetric to the corresponding elements above the main diagonal). | Simplified representation of symmetric block matrices (avoiding redundant writing of symmetric elements). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, X.; Gui, Y.; Xue, M.; Wang, X.; Gao, L. Finite-Time Tracking Control of Multi-Agent System with External Disturbance. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2061. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122061

Xu X, Gui Y, Xue M, Wang X, Gao L. Finite-Time Tracking Control of Multi-Agent System with External Disturbance. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2061. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122061

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Xiaole, Yalin Gui, Mengqiu Xue, Xincheng Wang, and Lixin Gao. 2025. "Finite-Time Tracking Control of Multi-Agent System with External Disturbance" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2061. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122061

APA StyleXu, X., Gui, Y., Xue, M., Wang, X., & Gao, L. (2025). Finite-Time Tracking Control of Multi-Agent System with External Disturbance. Symmetry, 17(12), 2061. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122061