Numerical Investigation of Wake Interference in Tandem Square Cylinders at Low Reynolds Numbers

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Identify critical gap spacing where abrupt transitions in drag, lift, and vortex shedding behaviour occur.

- Investigate the flow characteristics at various flow regimes.

- Examine the fluctuations in lift coefficient (), drag coefficient (), Strouhal number (St), and their root mean square (RMS) values for both cylinders.

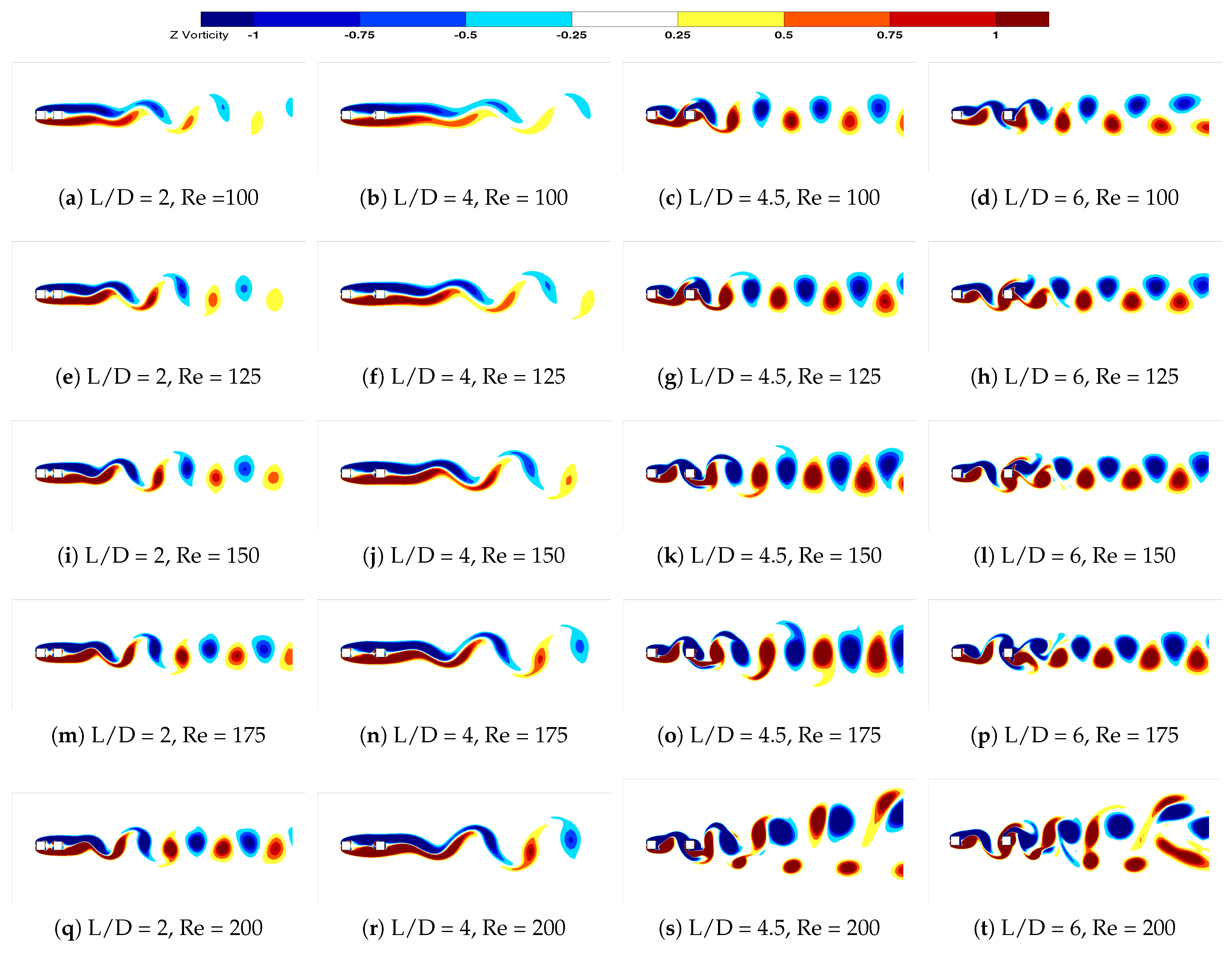

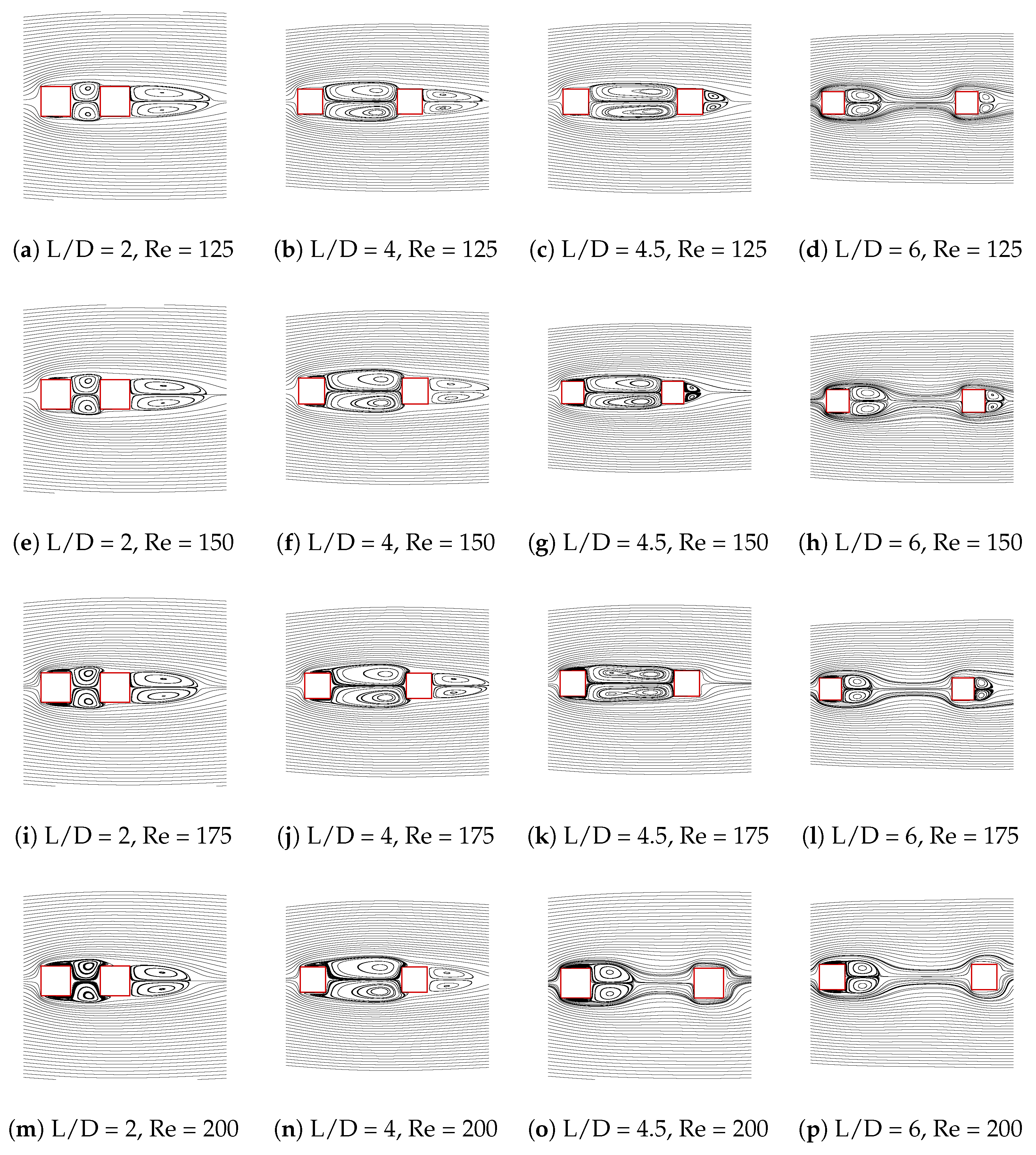

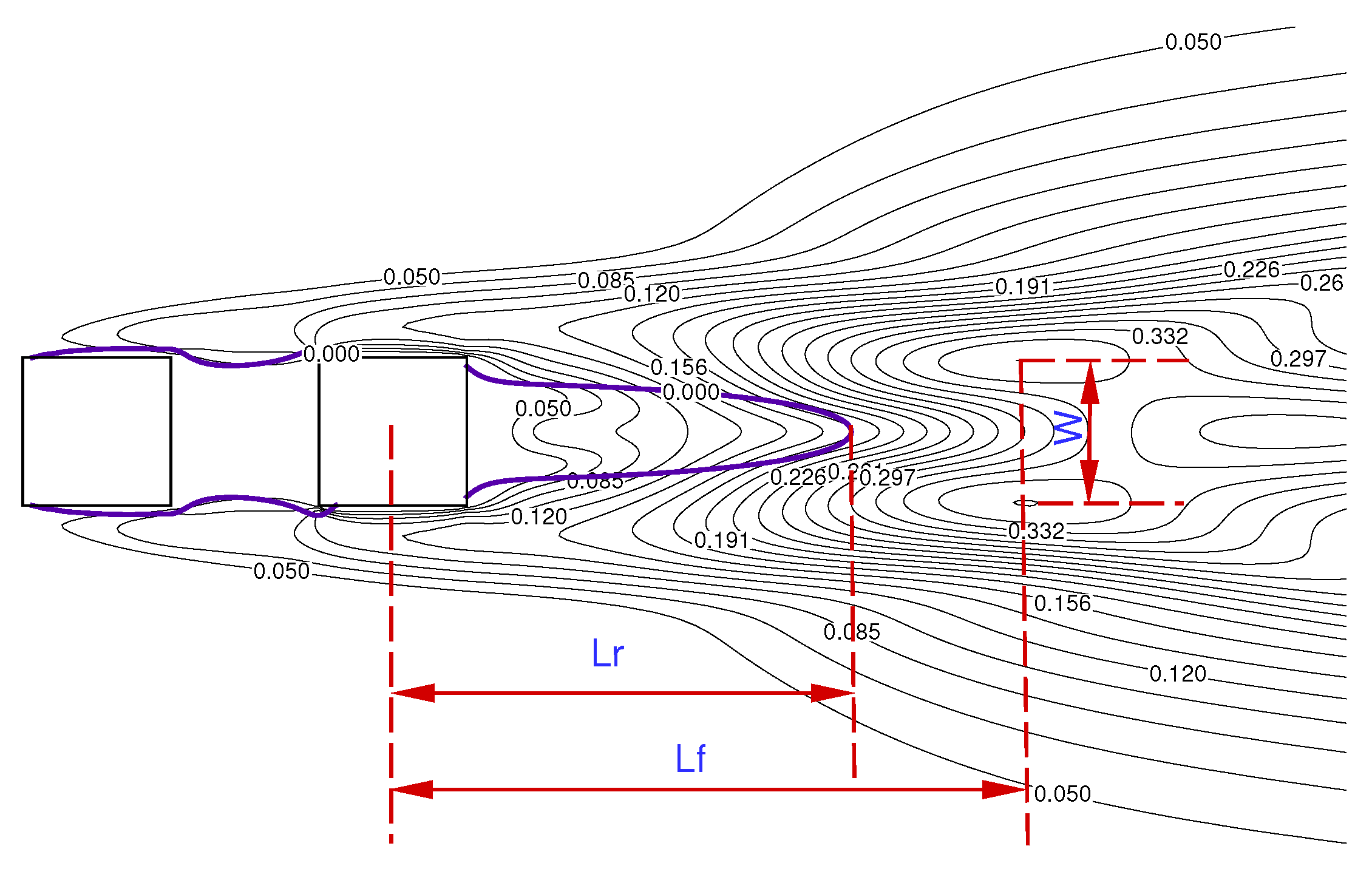

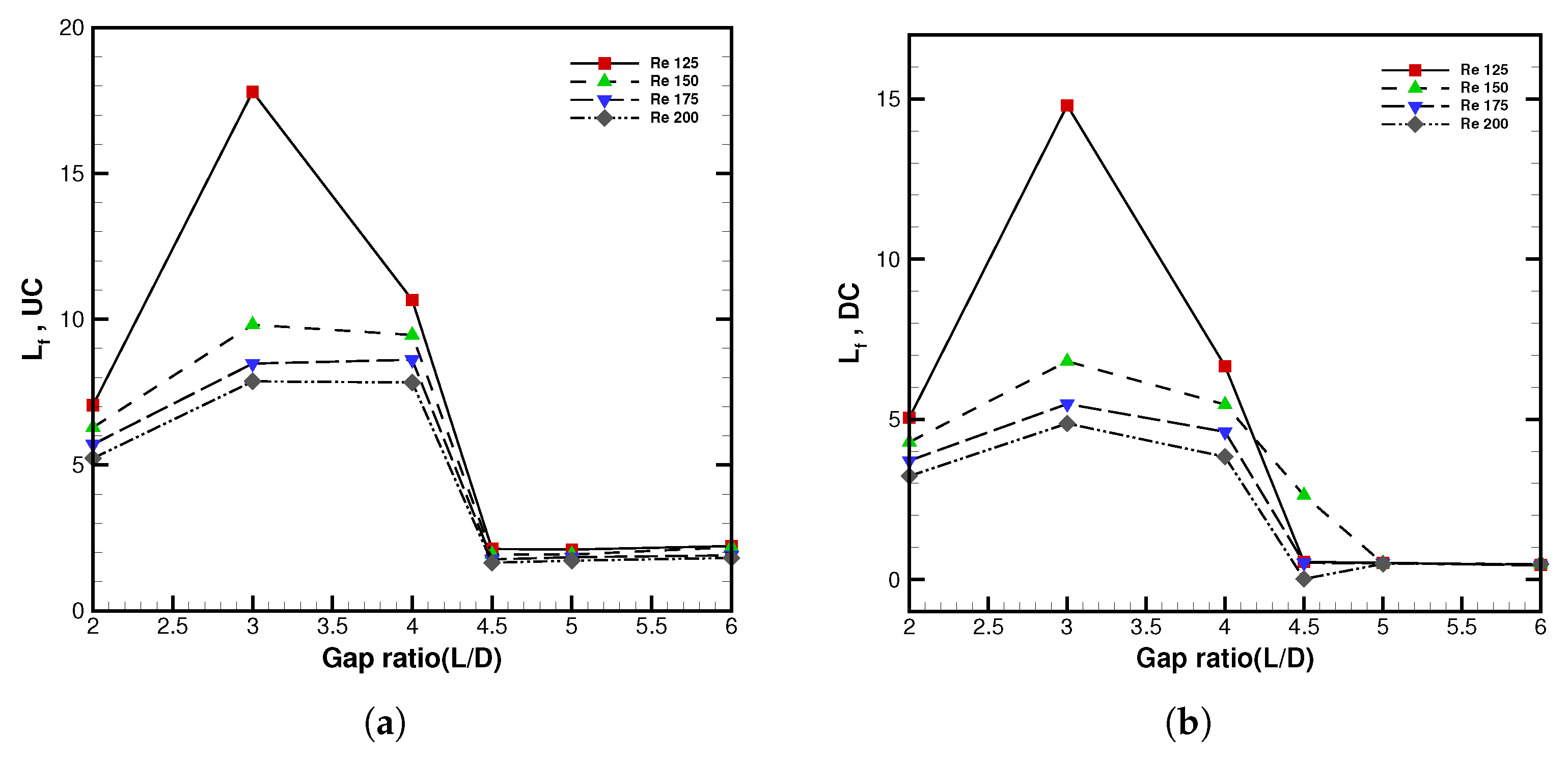

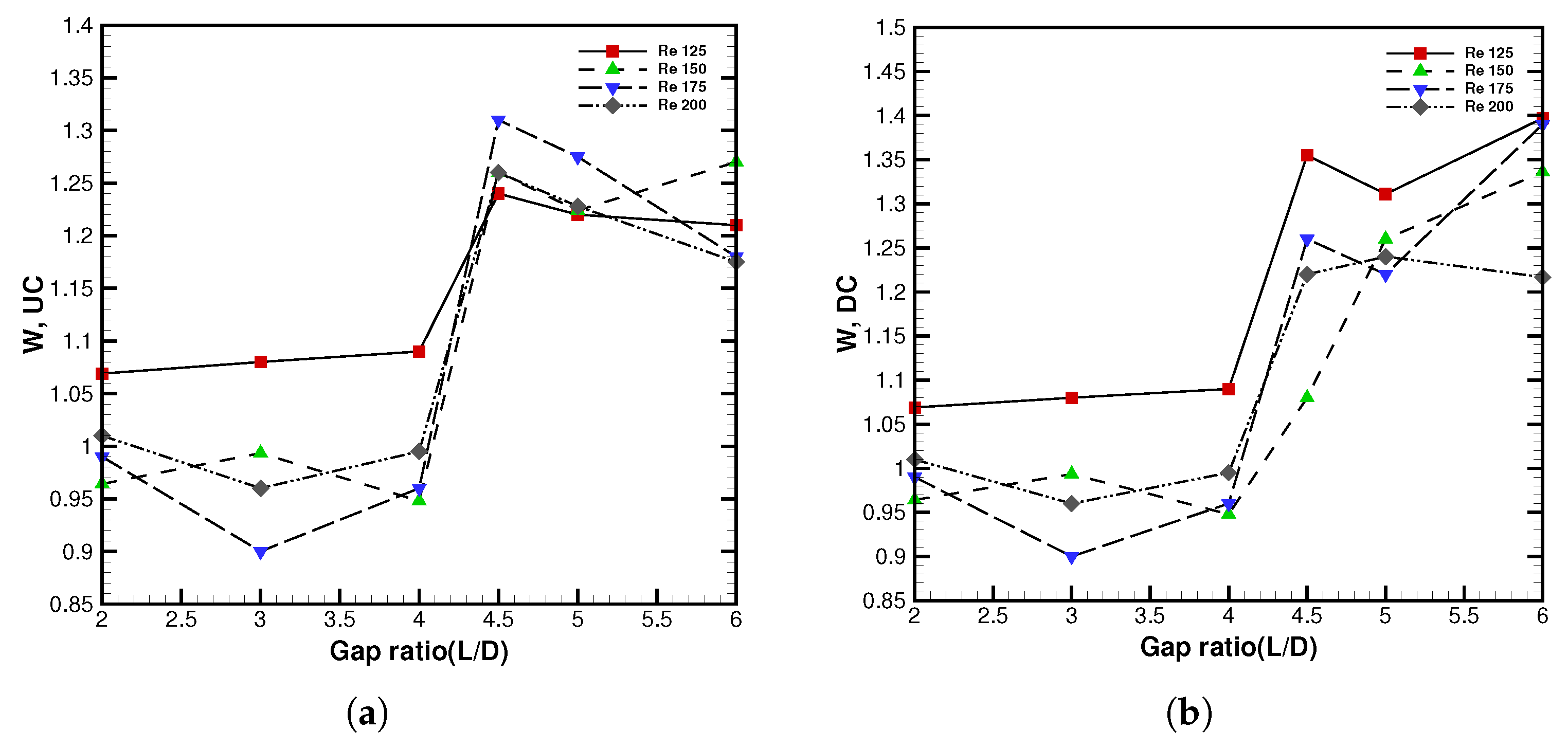

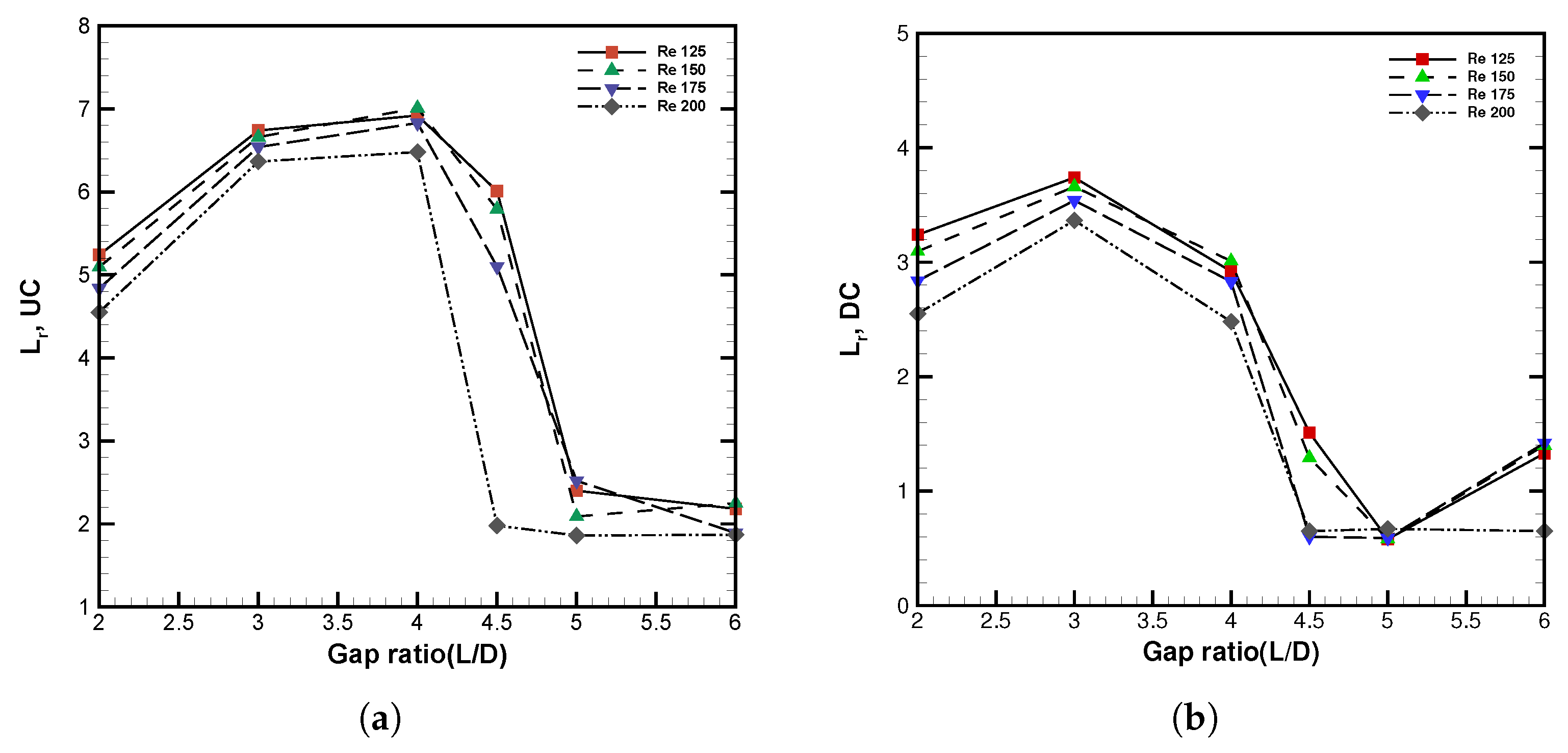

- Examine wake structure evolution, vortex formation length, wake width, and recirculation regions using streamlines and vorticity plots.

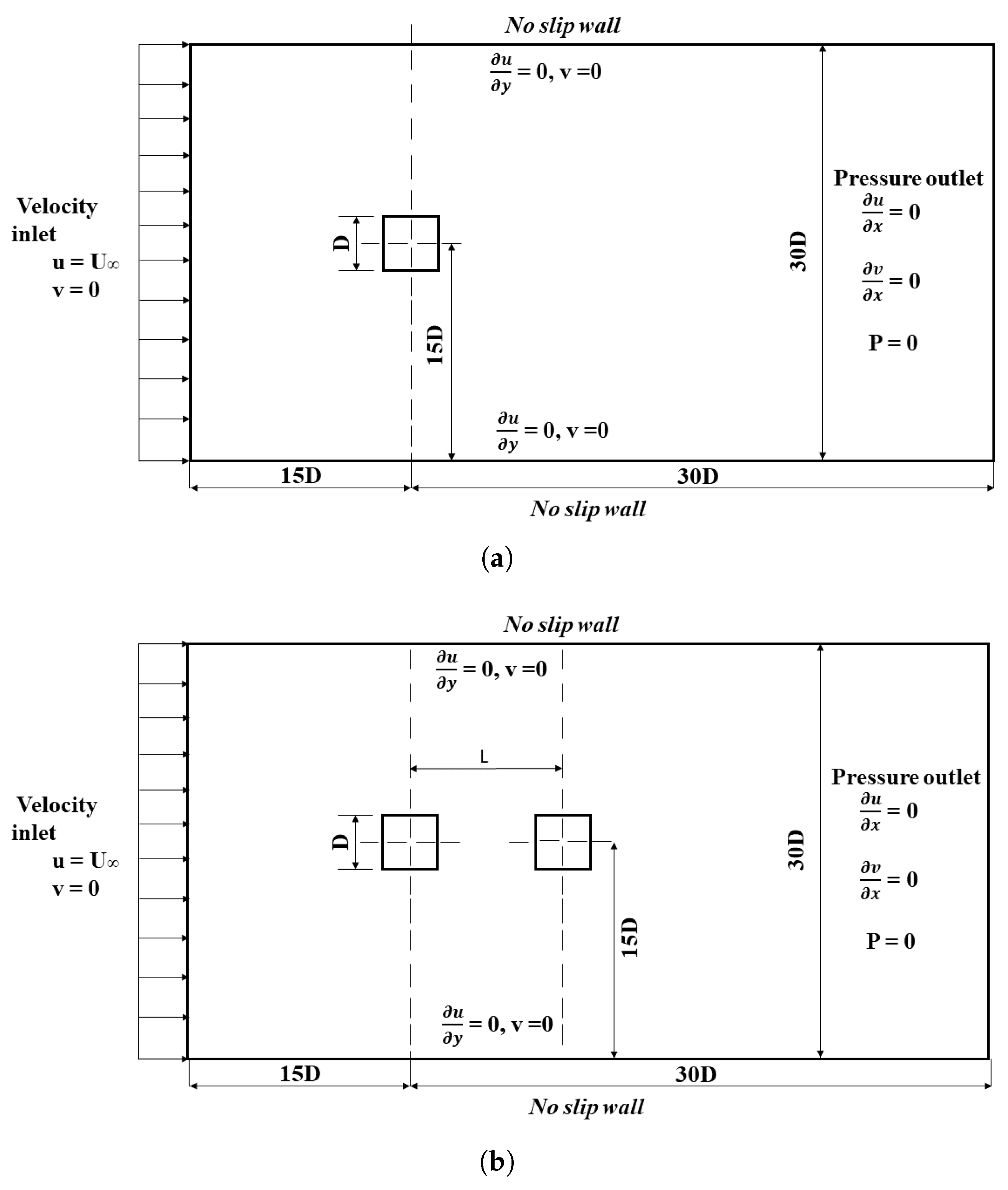

2. Problem Description and Computational Approach

2.1. Numerical Model and Solution Method

2.2. Governing Equations and Non-Dimensional Parameters

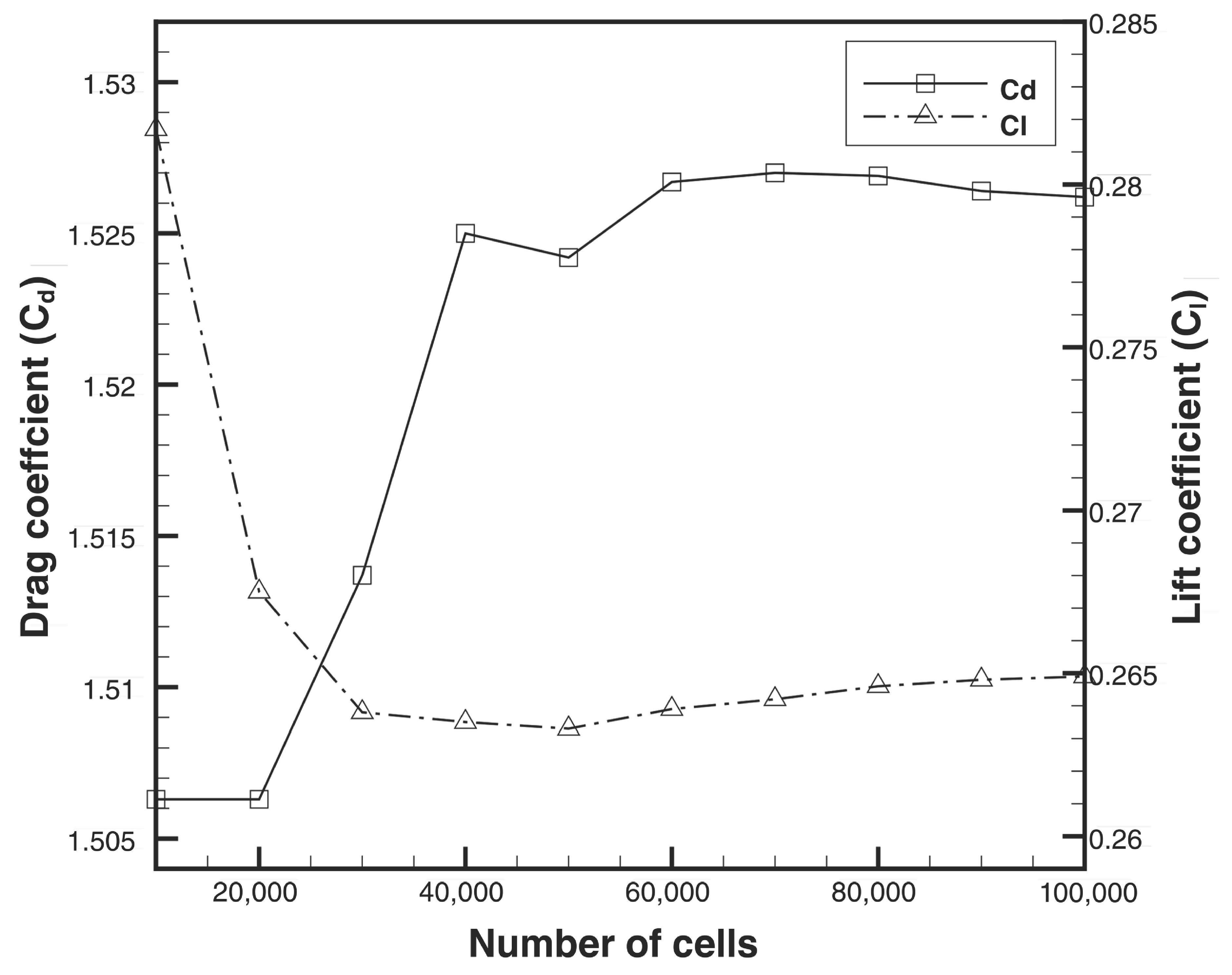

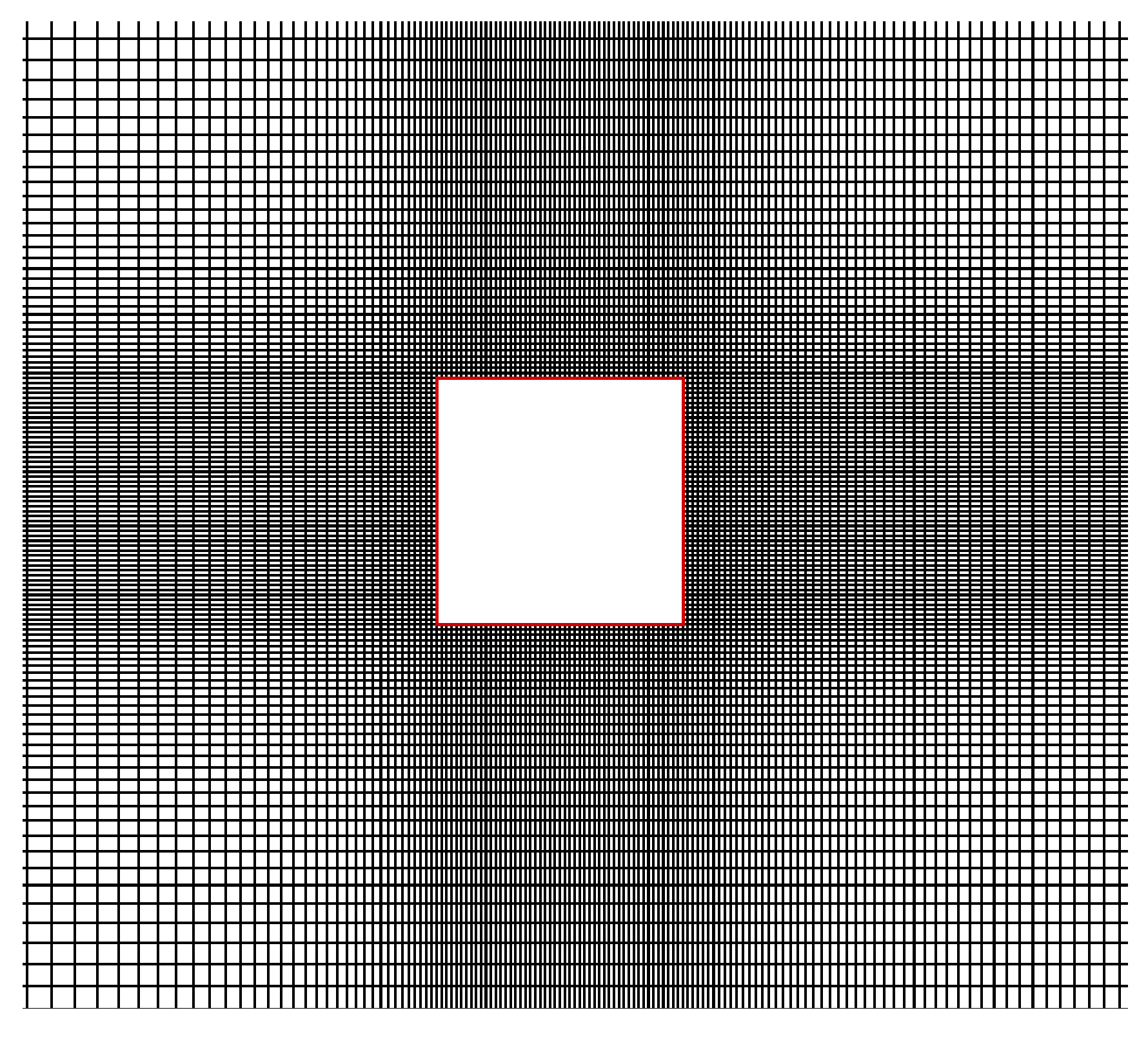

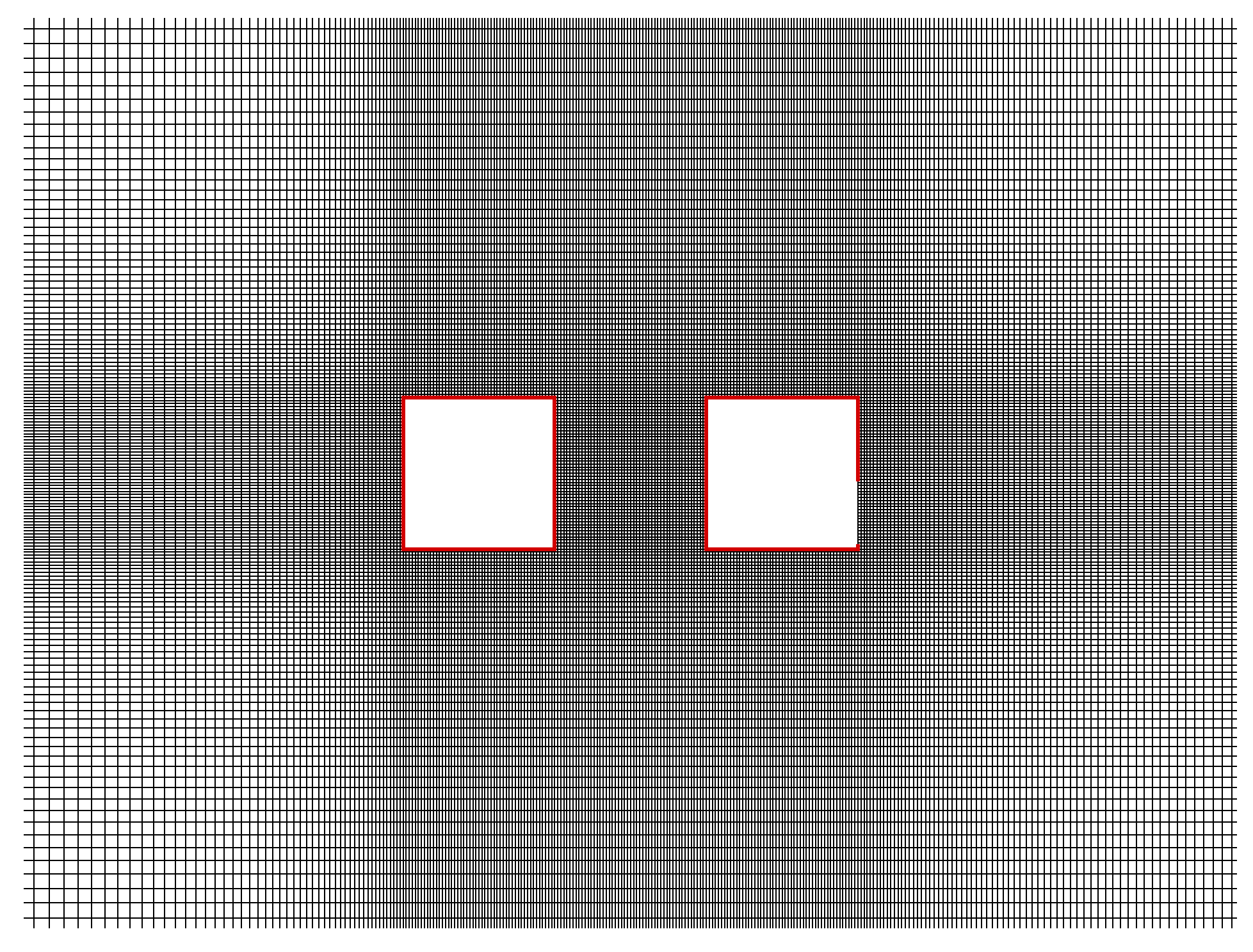

2.3. Domain and Grid Independence Studies

2.4. Numerical Code Validation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Detailed Numerical Analysis on a Single Square Cylinder

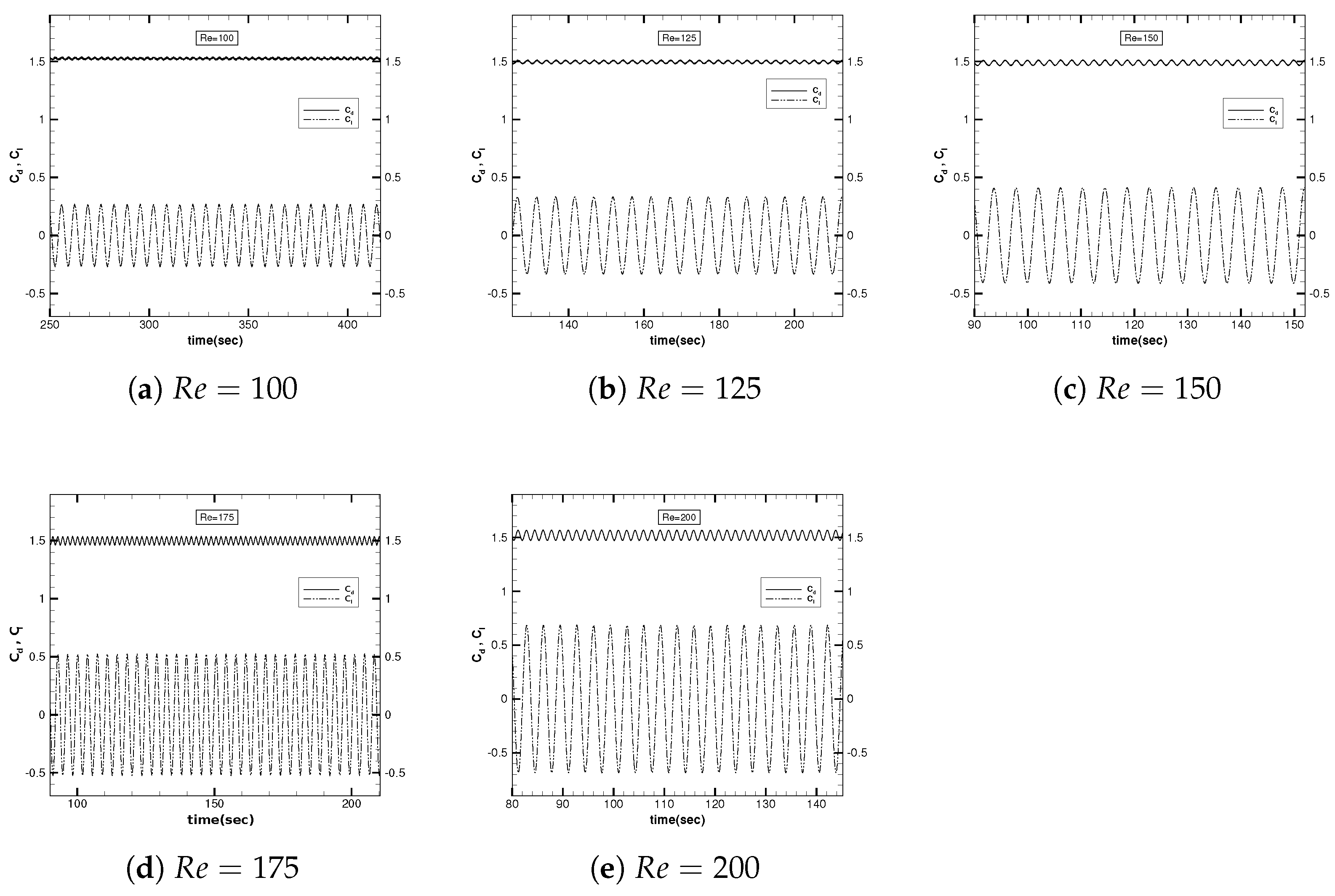

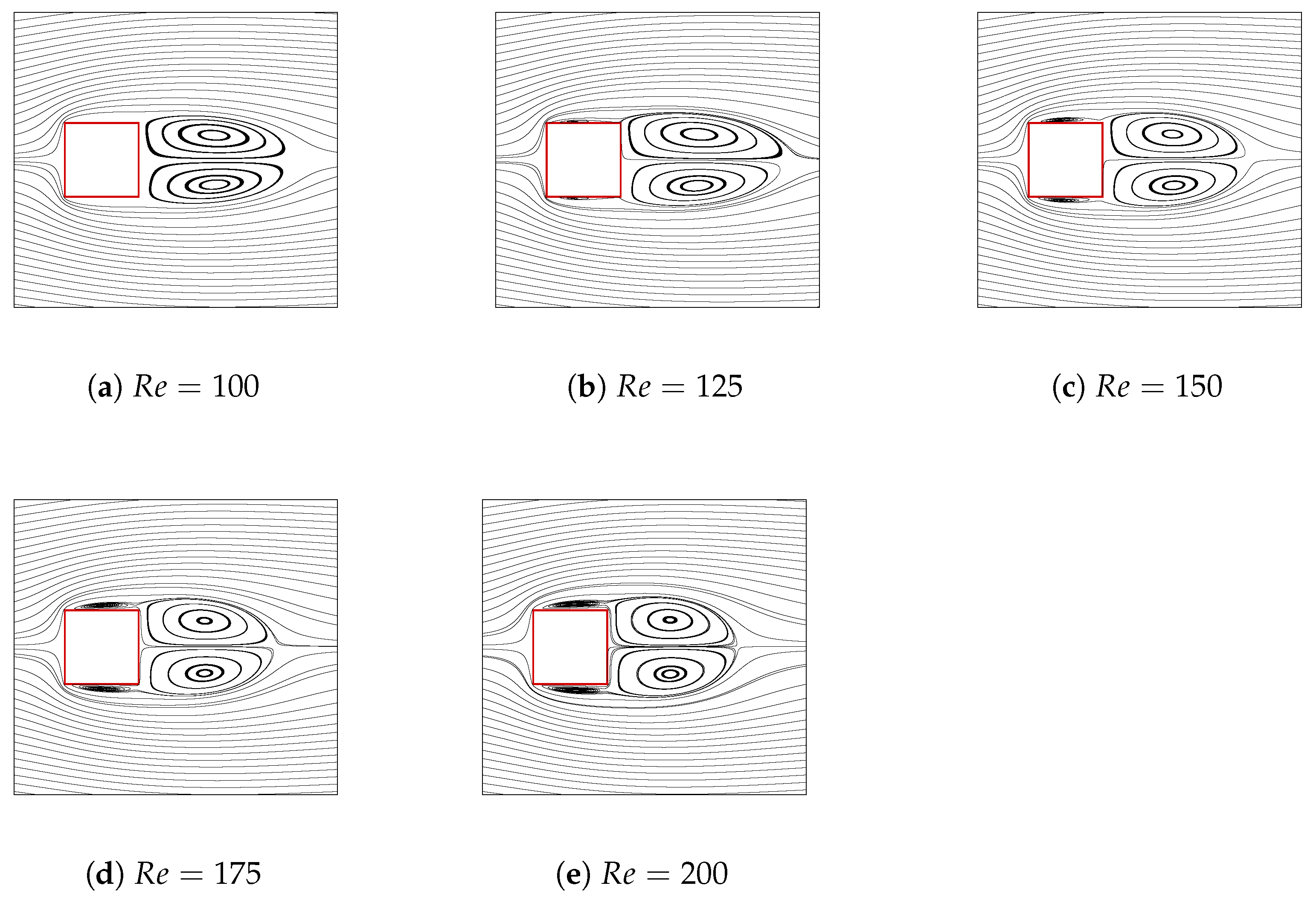

3.1.1. Aerodynamic Forces and Flow Structures

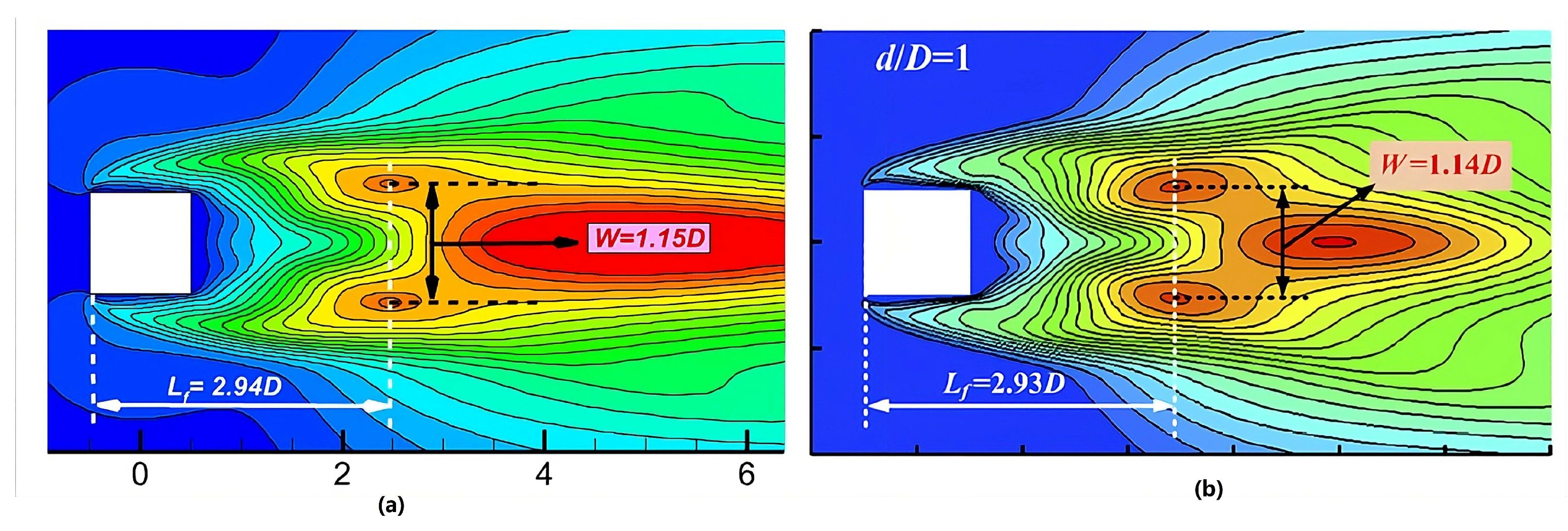

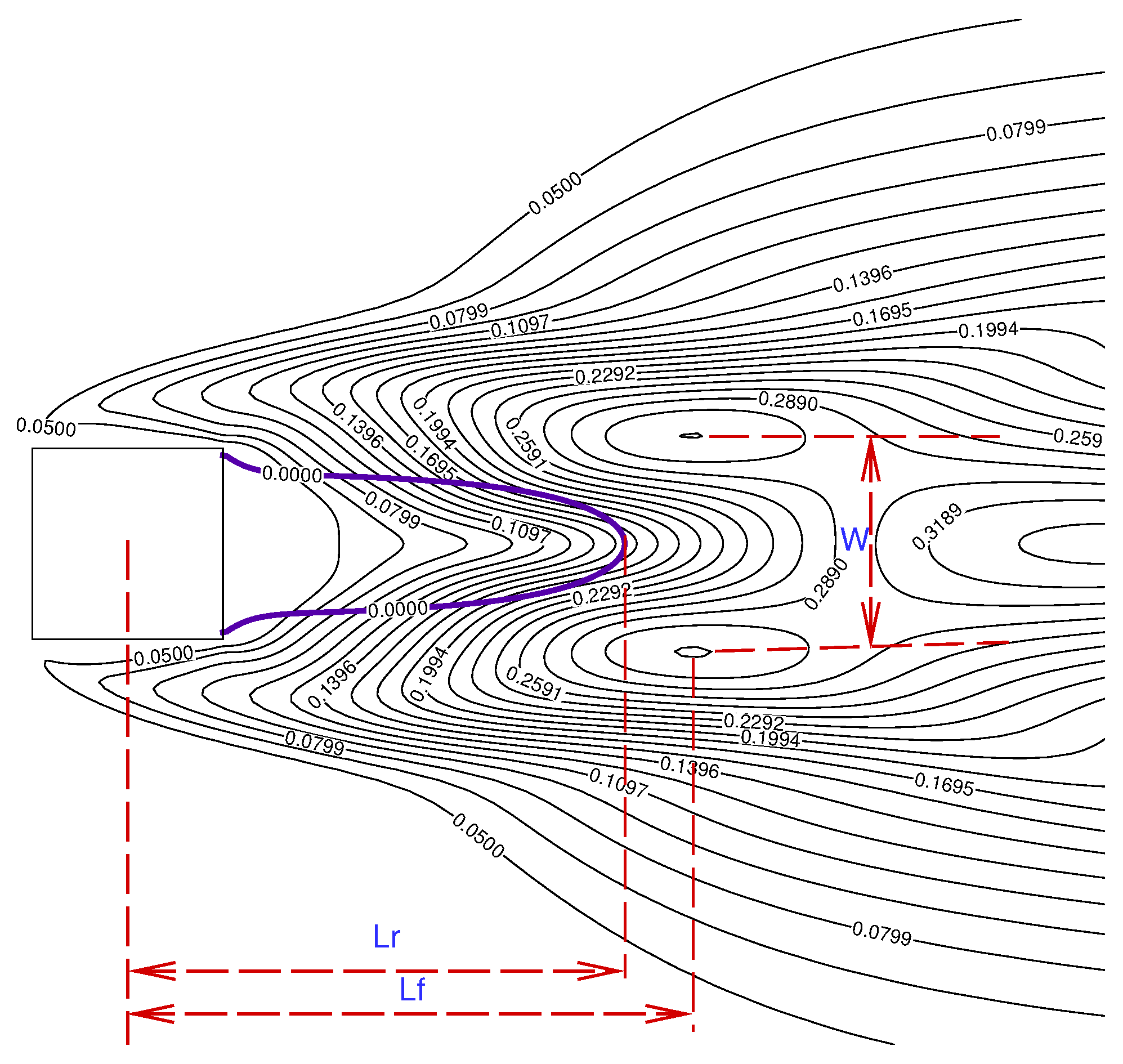

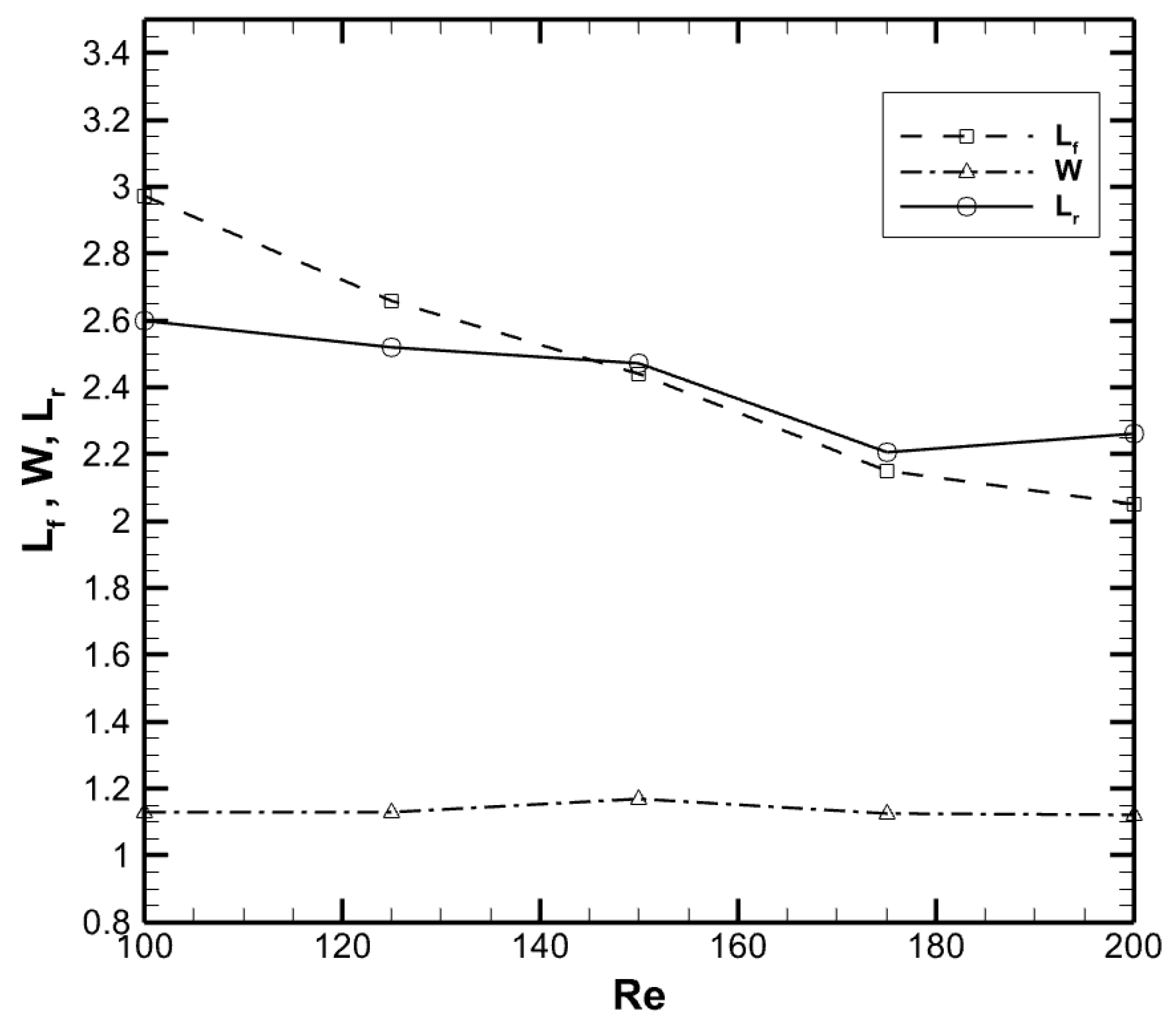

3.1.2. Cylinder Wake Parameters

3.2. Twin-Square Cylinder Interference Study

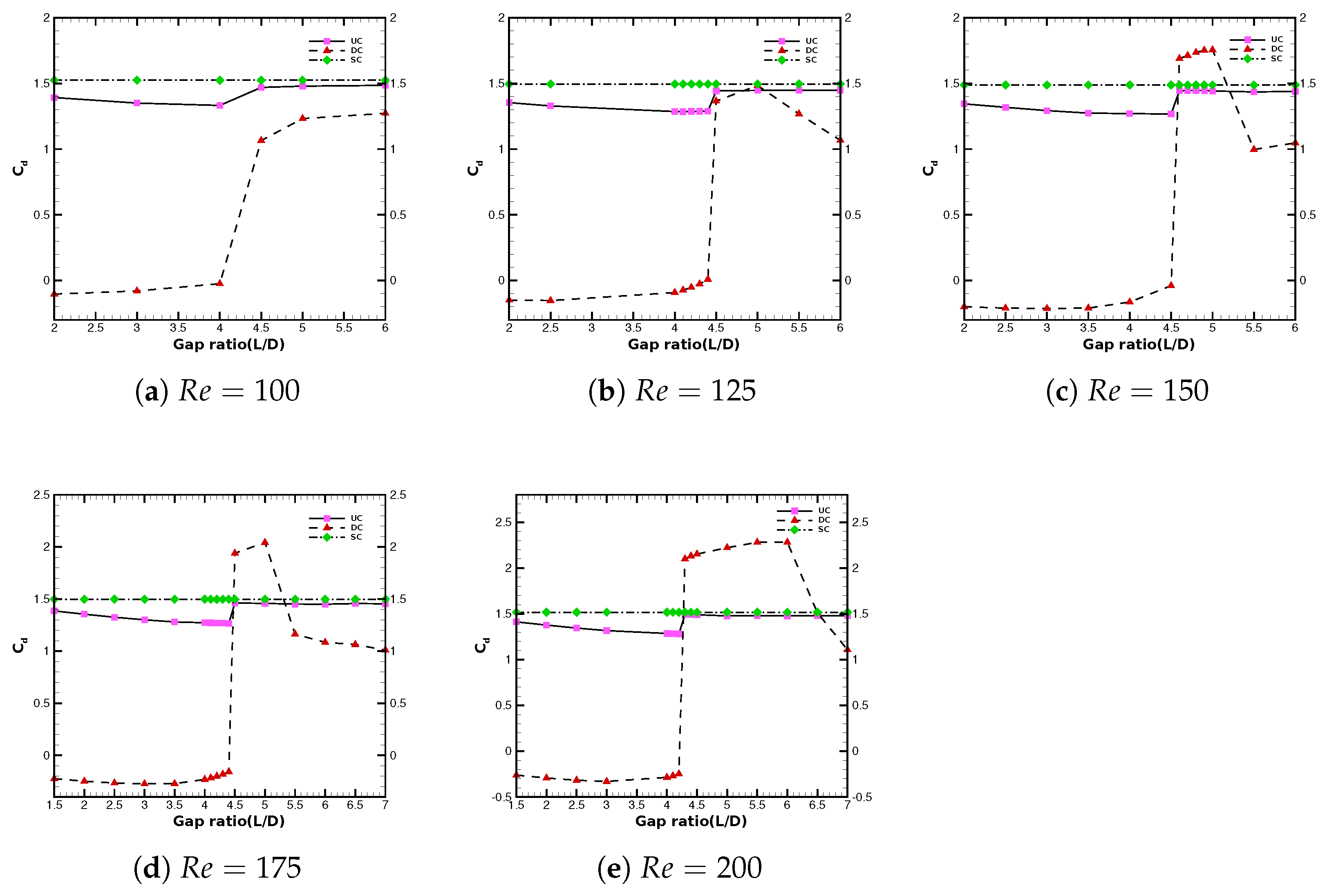

3.2.1. Drag Characteristics in Interference

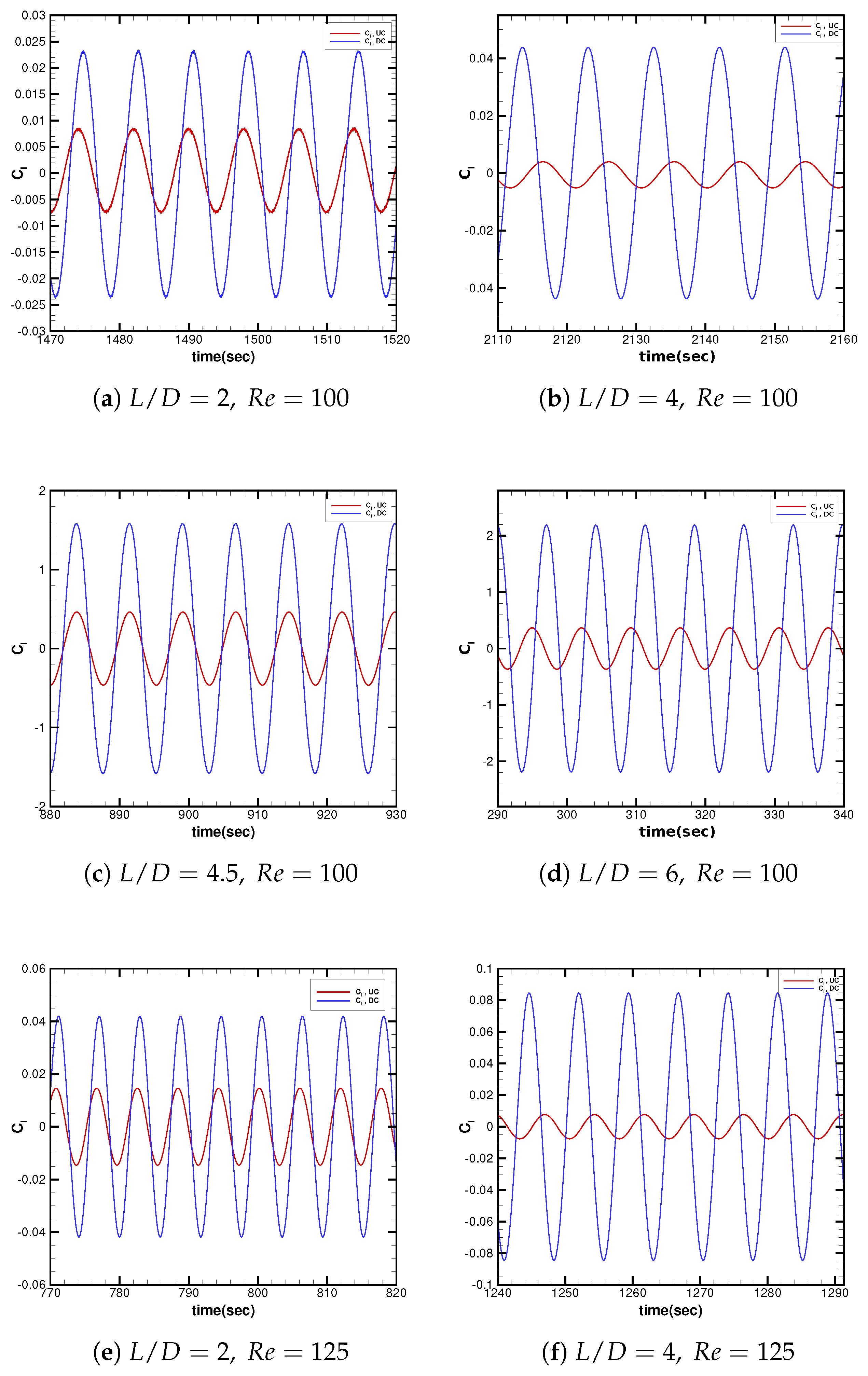

3.2.2. Temporal Lift Characteristics in Interference

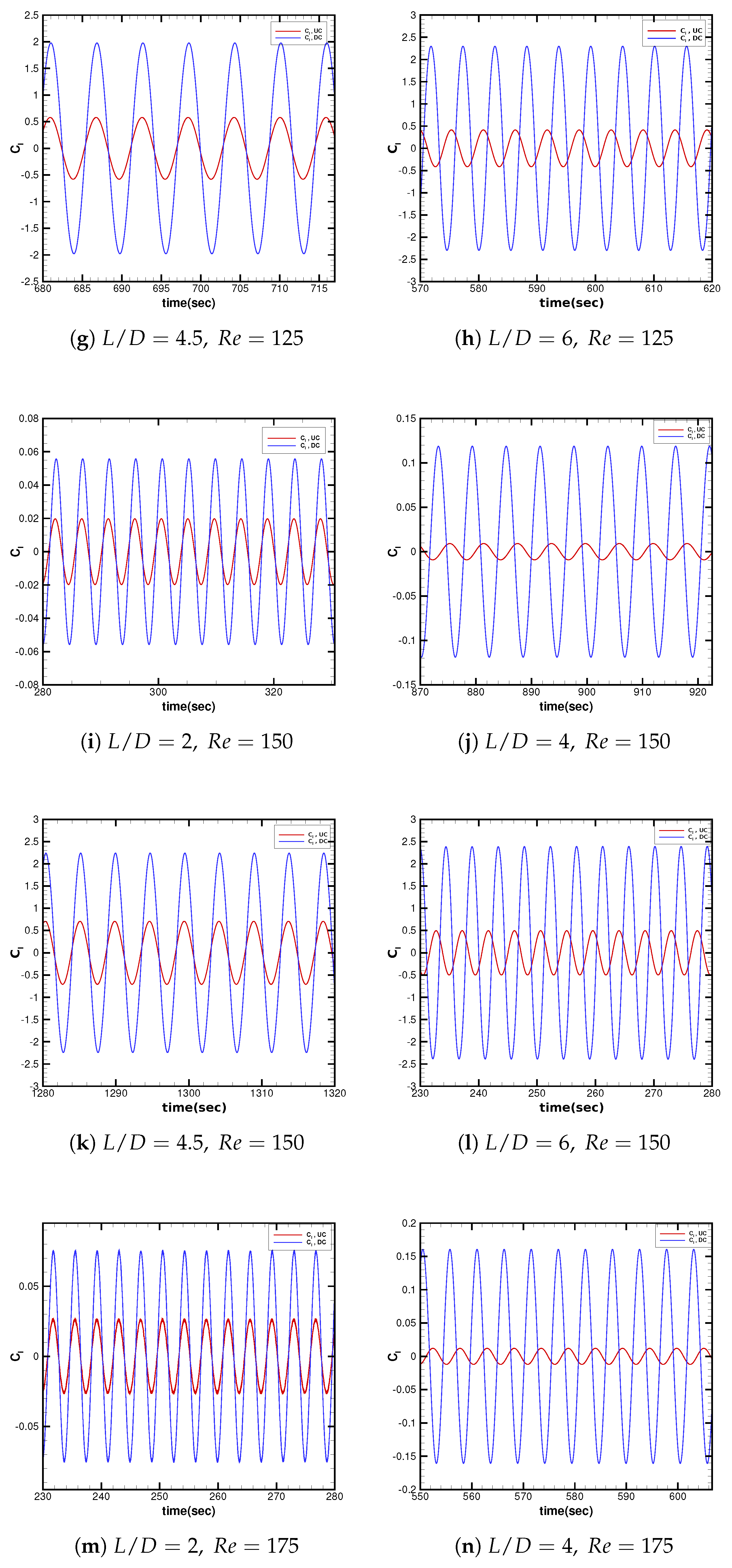

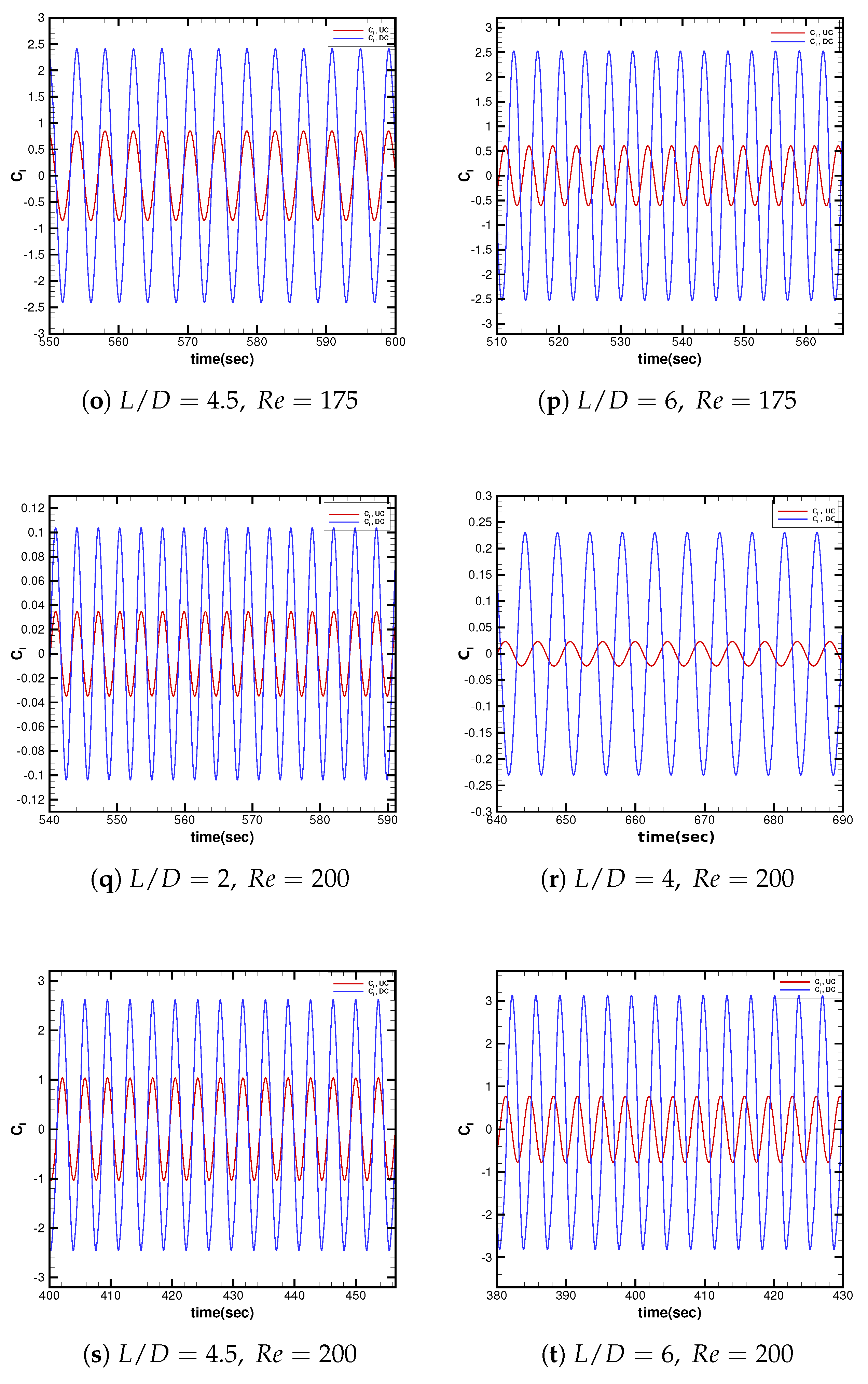

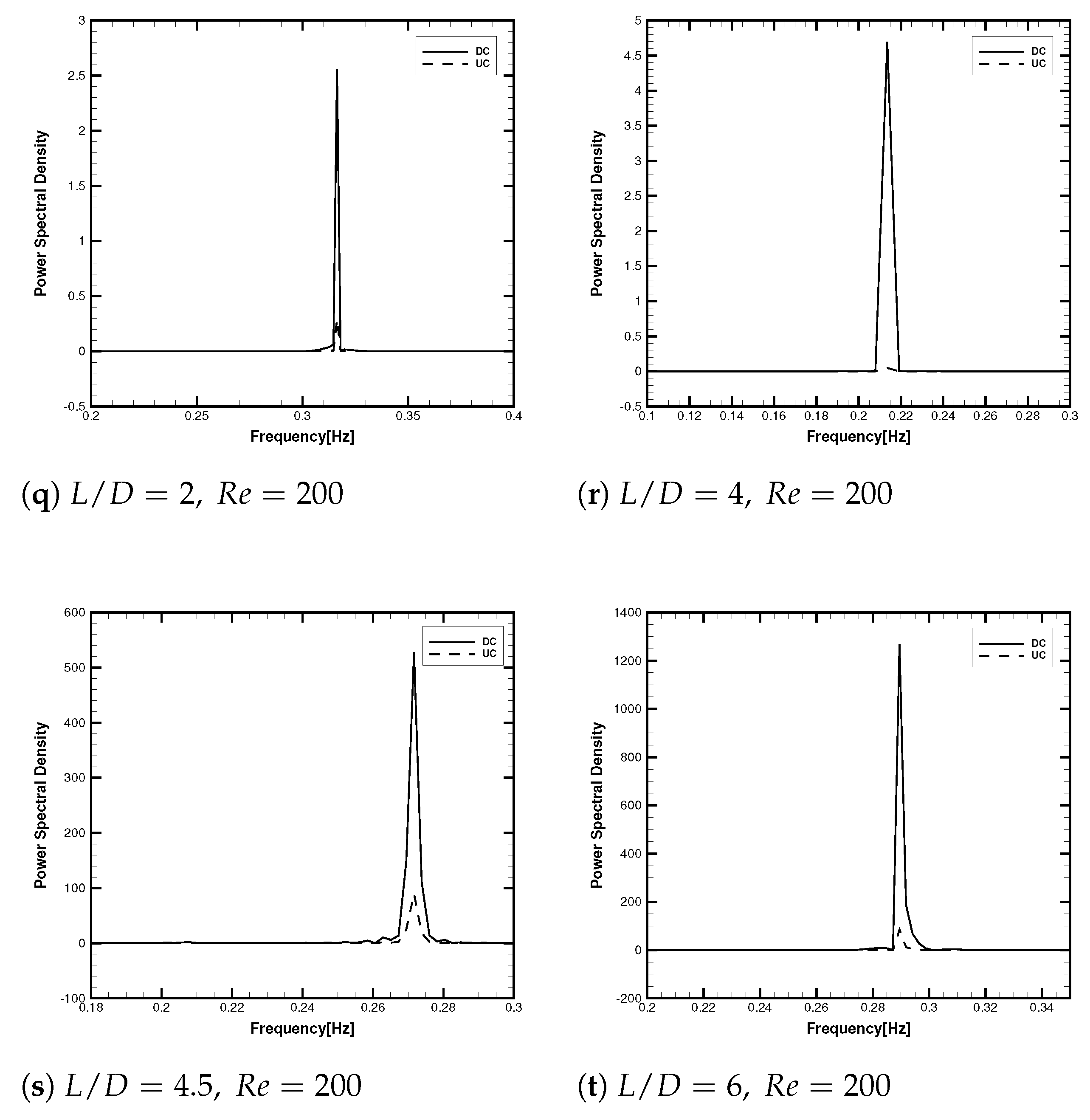

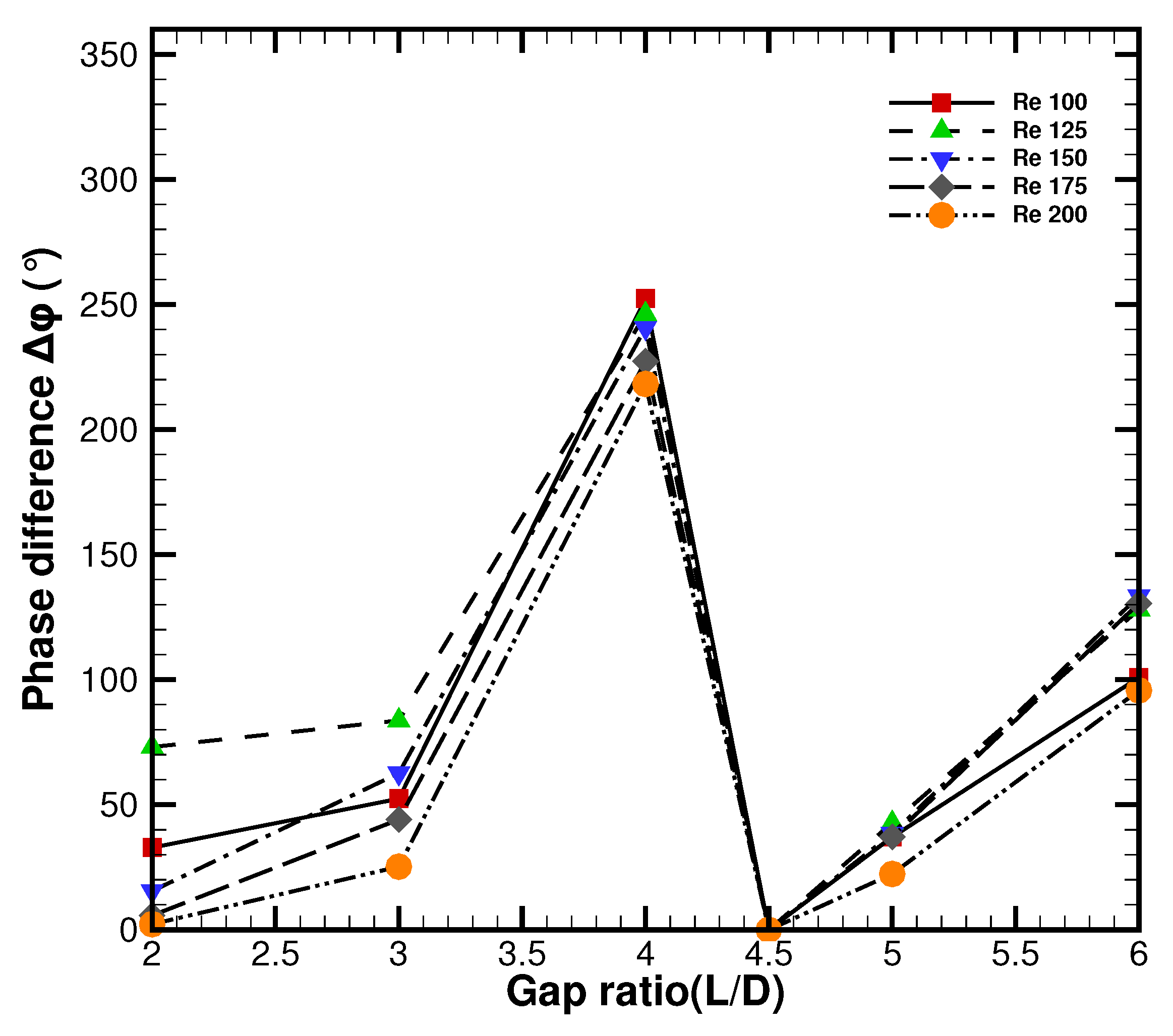

3.2.3. Spectral and Phase Shift Analysis of Lift Fluctuations

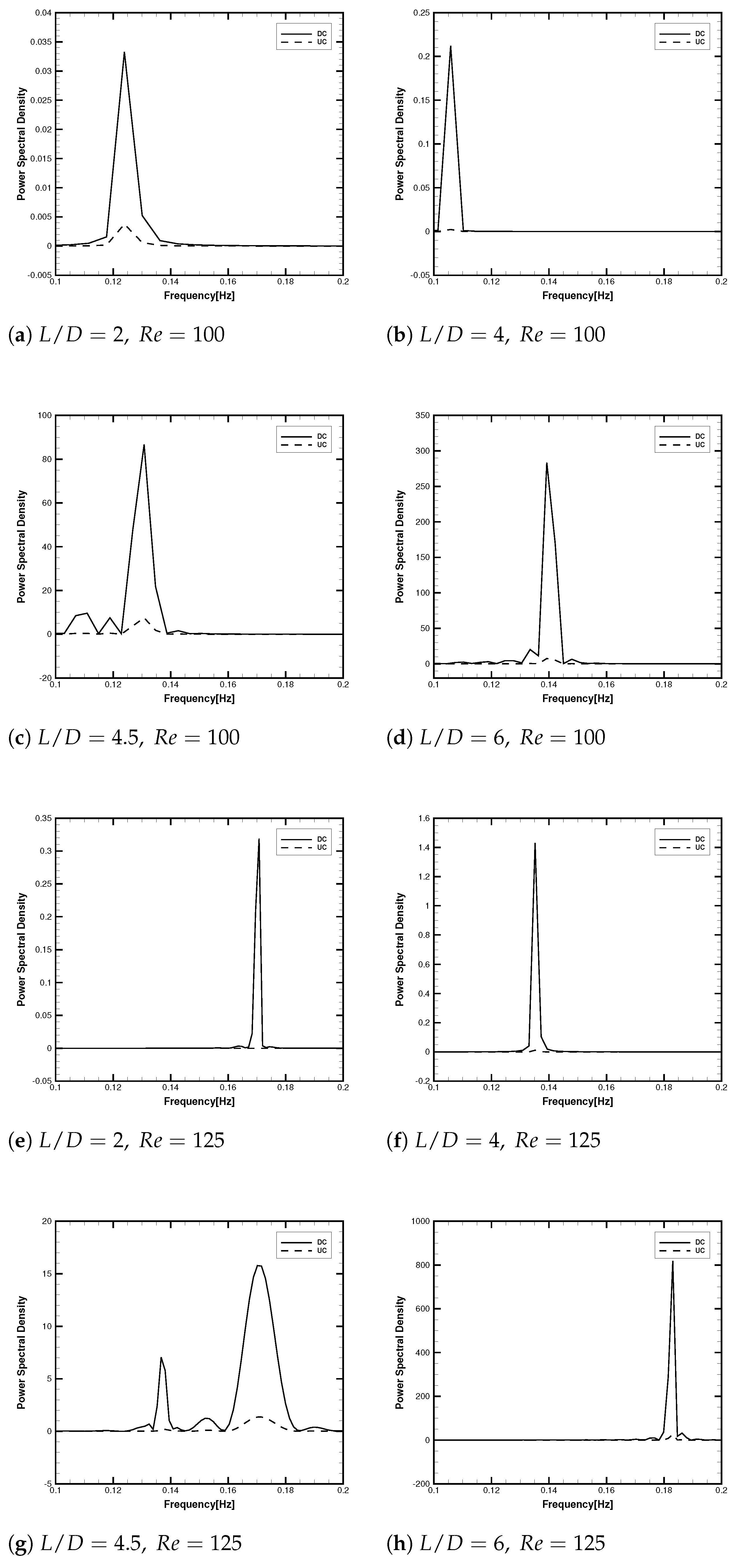

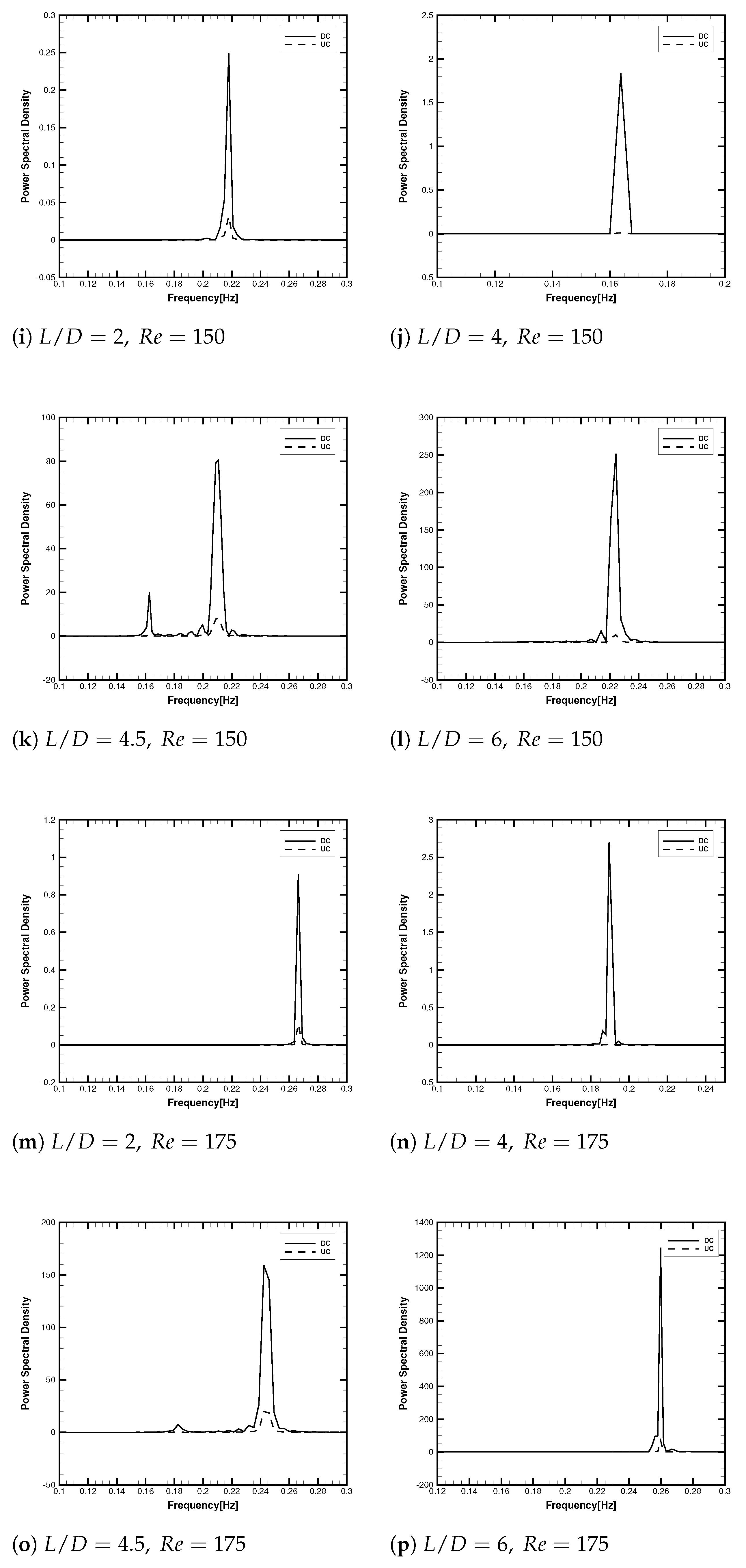

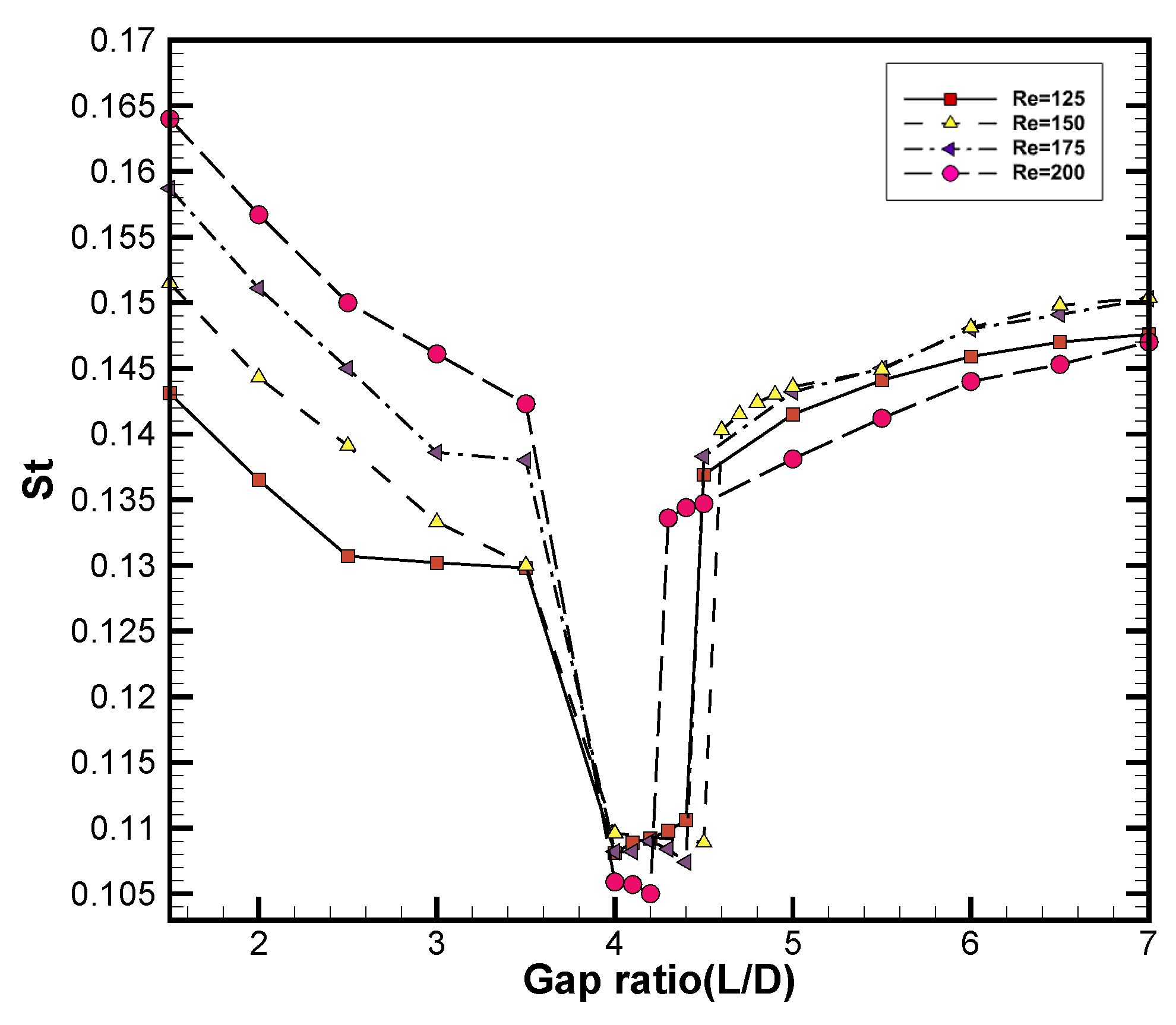

3.2.4. Strouhal Number () Characteristics in Interference

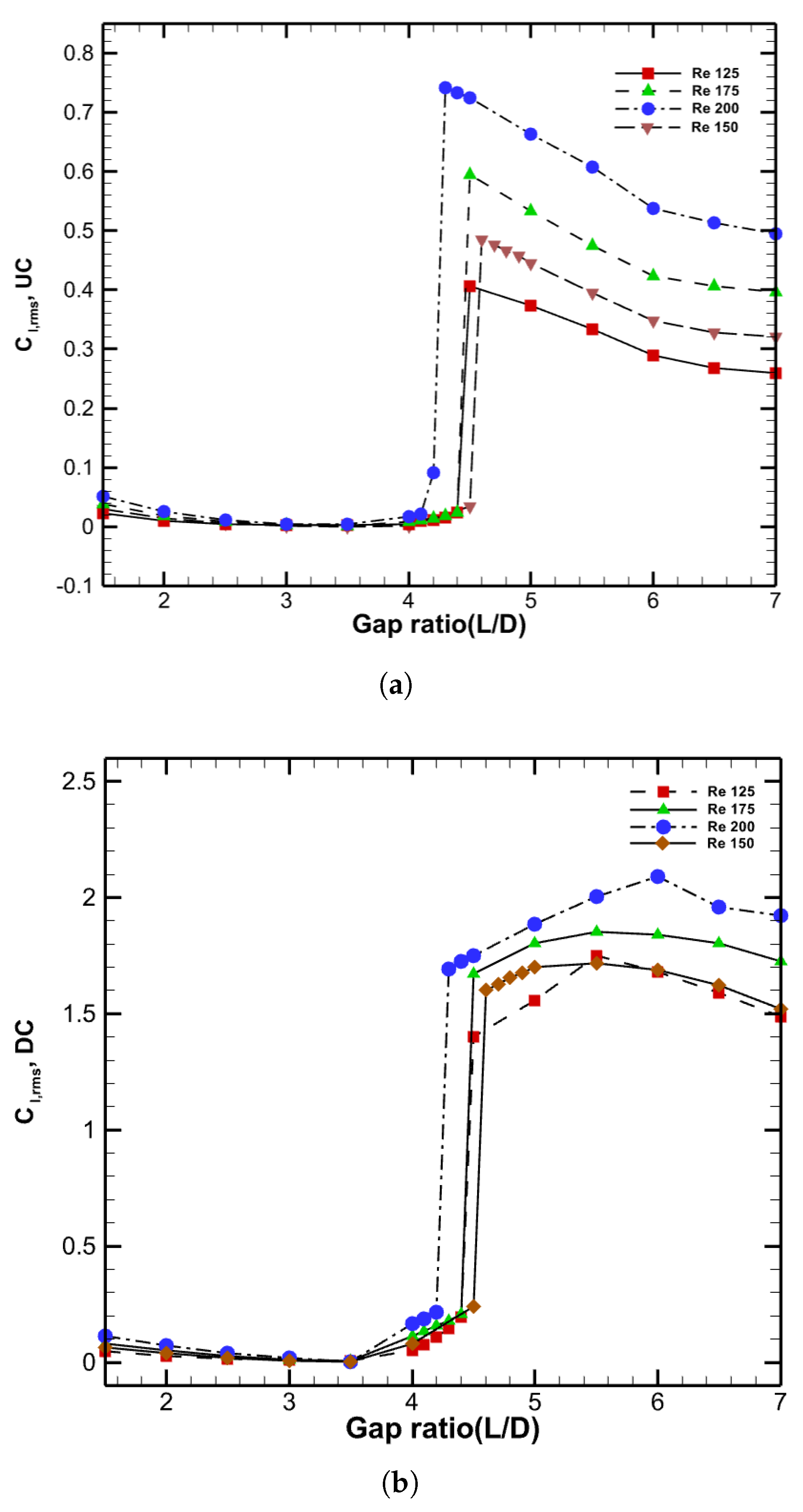

3.2.5. RMS Lift Characteristics in Interference

3.2.6. Vorticity Contours in Interference Case

3.2.7. Wake Interaction Patterns in Interference

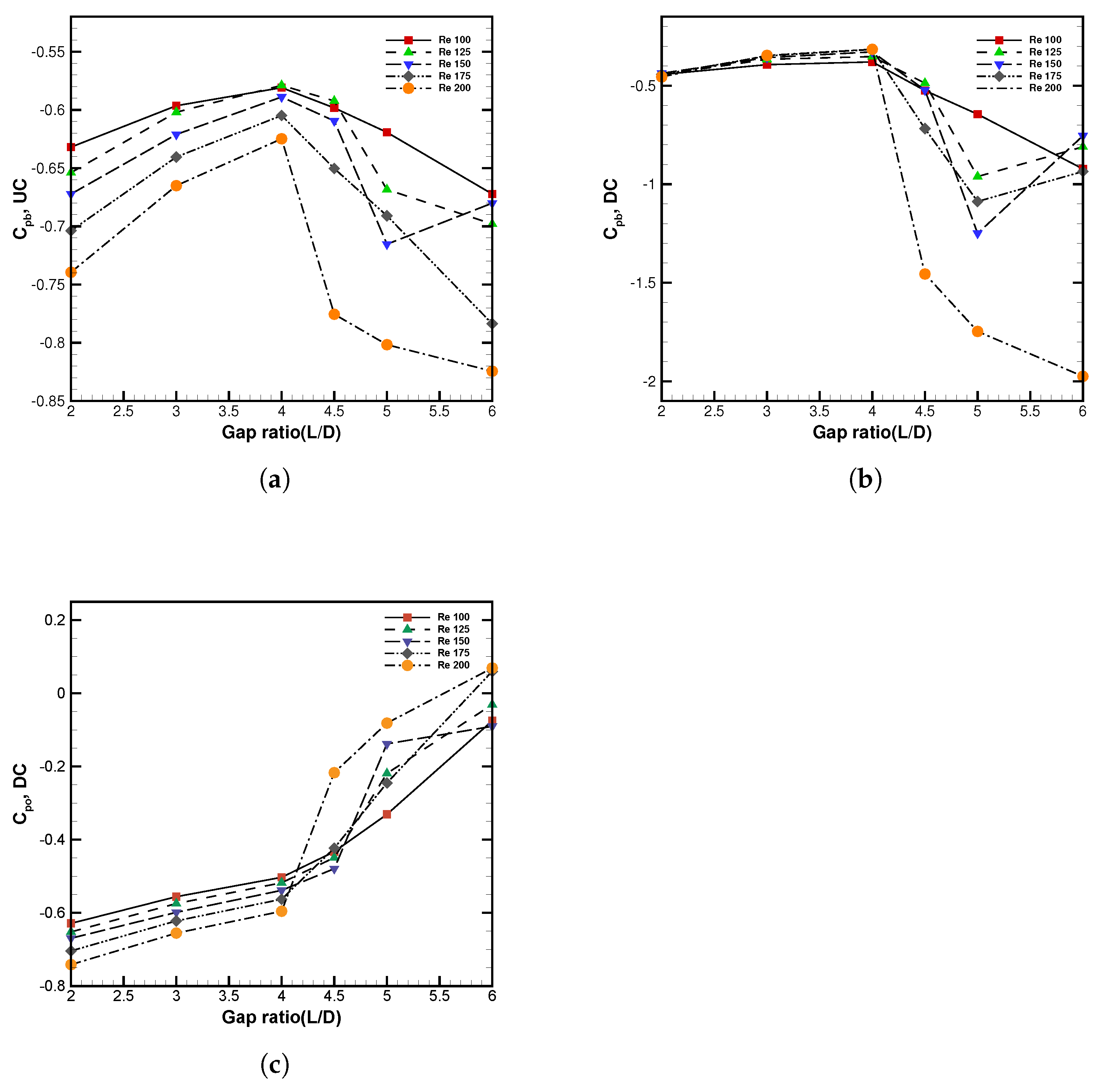

3.2.8. Pressure Coefficient Analysis

3.2.9. Detailed Wake Parameter Estimation in Interference

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, Y.; Cheng, Z.; McConkey, R.; Lien, F.S.; Yee, E. Modelling of flow-induced vibration of bluff bodies: A comprehensive survey and future prospects. Energies 2022, 15, 8719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.A.; Gowda, B.L. Flow-induced vibration of a square cylinder without and with interference. J. Fluids Struct. 2006, 22, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; He, J.; Zeng, H.; Zhu, Y.; Chan, S.Z.; Williams, M.R.; Khor, I.Z.L.; Yalla, O.V.; Sunny, M.R.; Ghoshal, R.; et al. A Review of Oscillators in Hydrokinetic Energy Harnessing Through Vortex-Induced Vibrations. Fluids 2025, 10, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.J.; Kumar, R.A.; Bernitsas, M.M. VIV and galloping of single circular cylinder with surface roughness at 3.0 × 104 ≤ Re ≤ 1.2 × 105. Ocean Eng. 2011, 38, 1713–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kumar, R.A.; Bernitsas, M.M. Suppression of vortex-induced vibrations of rigid circular cylinder on springs by localized surface roughness at 3.0 × 104 ≤ Re ≤ 1.2 × 105. Ocean Eng. 2016, 111, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lyu, Z.; Kou, J.; Zhang, W. Mode competition in galloping of a square cylinder at low Reynolds number. J. Fluid Mech. 2019, 867, 516–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, B.; Kumar, R.A. Flow-induced oscillations of a square cylinder due to interference effects. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 297, 842–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, M.K.; Dutta, S.; More, B.S.; Gandhi, B.K. Experimental investigation of flow over a square cylinder with an attached splitter plate at intermediate Reynolds number. J. Fluids Struct. 2018, 76, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandar, S.V.; Sarath, R.; Kumar, R.A. Aerodynamic characteristics of a square section cylinder: Effect of corner arc. In Proceedings of the 2017 2nd International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT), Mumbai, India, 7–9 April 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 814–819. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, M.A.; Abubaker, M.; Kumar, R.A.; Sohn, C.H. Drag reduction for flow past a square cylinder through corner chamfering. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2022, 36, 5501–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.A.; Sohn, C.H.; Gowda, B.L. A PIV study of the near wake flow features of a square cylinder: Influence of corner radius. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2015, 29, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, K.; Sarath, R. Investigation of Flow Structures Around a Circular Cylinder with Notch: A Flow Visualization Analysis. In Advances in Mechanical Processing and Design: Select Proceedings of ICAMPD 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Many, H.C.; Srinivasan, V.C.; Raghavan, A.K. Effect of corner-arc on the flow structures around a square cylinder. In Proceedings of the Fluids Engineering Division Summer Meeting, Montreal, QC, Canada, 15–20 July 2018; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 51555, p. V001T07A007. [Google Scholar]

- Hariprasad, C.; Ajith Kumar, R.; Dahl, J.; Sohn, C.H. Flow structures around a square cylinder: Effect of corner chamfering. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2024, 37, 04024021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Bernitsas, M.M.; Ajith Kumar, R. Selective Roughness in the Boundary Layer to Suppress Flow-Induced Motions of Circular Cylinder at 30,000 < Re < 120,000. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2012, 134, 041801. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.S.; Bernitsas, M.M.; Ajith Kumar, R. Multicylinder flow-induced motions: Enhancement by passive turbulence control at 28,000 < Re < 120,000. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2013, 135, 021802. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Kumar, R.A.; Bernitsas, M.M. Enhancement of flow-induced motion of rigid circular cylinder on springs by localized surface roughness at 3 × 104 ≤ Re ≤ 1.2 × 105. Ocean Eng. 2013, 72, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohankar, A.; Khodadadi, M.; Rangraz, E.; Alam, M.M. Control of flow and heat transfer over two inline square cylinders. Phys. Fluids 2019, 31, 123604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearman, P.W. Vortex shedding from oscillating bluff bodies. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1984, 16, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastan, M.; Alam, M.M.; Zhu, H.; Ji, C. Onset of vortex shedding from a bluff body modified from square cylinder to normal flat plate. Ocean Eng. 2022, 244, 110393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Tang, T.; Zhou, T.; Liu, H.; Zhong, J. Flow structures around trapezoidal cylinders and their hydrodynamic characteristics: Effects of the base length ratio and attack angle. Phys. Fluids 2020, 32, 103606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, T.; Alam, M.M.; Islam, M. Heat transfer and flow around cylinder: Effect of corner radius and Reynolds number. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 171, 121105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, F.; Alam, M.M. Flow structure around and heat transfer from cylinders modified from square to circular. Phys. Fluids 2019, 31, 083604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Dhiman, A.K. Computations of incompressible fluid flow around a long square obstacle near a wall: Laminar forced flow and thermal characteristics. Sādhanā 2017, 42, 941–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, B.; Bergadà, J.; Mellibovsky, F.; Sang, W.; Xi, C. Numerical investigation on the flow around a square cylinder with an upstream splitter plate at low Reynolds numbers. Meccanica 2020, 55, 1037–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavya, H.; Kotresha, B.; Naik, K. CFD Analysis of 2-D unsteady flow past a square cylinder at an angle of incidence. Int. J. Adv. Res. Mech. Prod. Eng. Dev. 2014, 1, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.U.; Manzoor, R.; Ying, Z.C.; Rashdi, M.M.; Khan, A. Numerical investigation of fluid flow past a square cylinder using upstream, downstream and dual splitter plates. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2017, 31, 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, C.K.; Ravindra, H.; Krishnegowda, Y. Visualization of flow past square cylinders with corner modification. J. Mech. Energy Eng. 2020, 4, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, Y.K.; Ravindra, H.V.; Chowdeswarally Krishnappa, V. Numerical analysis of two square cylinders of different sizes with and without corner modification. In Proceedings of the ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 11–17 November 2016; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 50626, p. V008T10A001. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Chang, J.; Yaying, M. Numerical Research on the Influence of Parallel Square Cylinder Space on the Characteristics of Karman Vortex Street and Combustion around Bluff Body. In Proceedings of the 2020 Asia Energy and Electrical Engineering Symposium (AEEES), Chengdu, China, 28–31 May 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 270–274. [Google Scholar]

- Mat Ali, M.S.; Doolan, C.J.; Wheatley, V. Low Reynolds number flow over a square cylinder with a splitter plate. Phys. Fluids 2011, 23, 033602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidhul, K.; Sunil, A.; Kishore, V. Numerical Investigation of Flow Characteristics over a Square Cylinder with a Detached Flat Plate of Varying Thickness at Critical Gap Distance in the wake at Low Reynolds Number. Int. J. Res. Aeronaut. Mech. Eng. 2015, 3, 104–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Singh, S.K. Flow past a bluff body subjected to lower subcritical Reynolds number. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 2020, 5, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Analysis of 2D unsteady flow past a square cylinder at low Reynolds numbers with CFD and a mesh refinement method. WSEAS Trans. Fluid Mech 2017, 12, 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.H.; Chen, J.M. Observations of hysteresis in flow around two square cylinders in a tandem arrangement. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2002, 90, 1019–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, R.; Ghaffar, A.; Baleanu, D.; Nisar, K.S. Numerical analysis of fluid forces for flow past a square rod with detached dual control rods at various gap spacing. Symmetry 2020, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.K.; Biswas, G.; Muralidhar, K. Three-dimensional study of flow past a square cylinder at low Reynolds numbers. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2003, 24, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayem, A.A.; Bayomi, N. Experimental and numerical flow visualization of a single square cylinder. Int. J. Comput. Methods Eng. Sci. Mech. 2006, 7, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Mohebbi, R.; Rashidi, M.; Yang, Z. Numerical simulation of flow over a square cylinder with upstream and downstream circular bar using lattice Boltzmann method. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 2018, 29, 1850030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, D.; Raja, M. Mixed convection heat transfer past in-line square cylinders in a vertical duct. Therm. Sci. 2013, 17, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ray, R.K. A numerical simulation of shear flow past two equal sized square cylinders arranged in parallel at Re = 500. AIP Conf. Proc. 2017, 1863, 490003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushyam, A.; Bergada, J.M. A numerical investigation of wake and mixing layer interactions of flow past a square cylinder. Meccanica 2017, 52, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Firdaus, A.F.; Nguyen, V.L.; Zuhal, L.R. Investigation of the flow around two tandem rotated square cylinders using the least square moving particle semi-implicit based on the vortex particle method. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 027117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouchakzad, M.; Sohankar, A.; Rastan, M. Onset of vortex shedding and hysteresis in flow over tandem sharp-edged cylinders of diverse cross sections. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 013604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, Q.; Duan, C.; Wang, D.; Gu, Z. New insights into numerical simulations of flow around two tandem square cylinders. AIP Adv. 2021, 11, 045315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.; Yasin, N.; Saqlain, M.; Ul-Islam, S.; Ahmad, S. Numerical investigation and statistical analysis of the flow patterns behind square cylinders arranged in a staggered configuration utilizing the Lattice Boltzmann method. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2024, 17, 1820–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohankar, A.; Rangraz, E.; Khodadadi, M.; Alam, M.M. Fluid flow and heat transfer around single and tandem square cylinders subjected to shear flow. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2020, 42, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Ni, Y.; Liu, C. Flow effect around two square cylinders arranged side by side using lattice Boltzmann method. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 2008, 19, 1683–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, W.S.; Ashfaq, K.; Rahman, H. Influence of gap ratios on wake dynamics of two rectangular 5:1 cylinders placed inline. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 103621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsoom, S.; Abbasi, W.S.; Manzoor, R. Numerical study of flow past two square cylinders with horizontal detached control rod through passive control method. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 065009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshandeh, J.F.; Alam, M.M. Reynolds number effect on the flow past two tandem cylinders. Wind Struct. 2020, 30, 475–483. [Google Scholar]

- Etminan, A.; Moosavi, M.; Ghaedsharafi, N. Characteristics of aerodynamics forces acting on two square cylinders in the streamwise direction and its wake patterns. Adv. Cont. Chem. Eng. Civ. Eng. Mech. Eng. 2010, 209, 217. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, W.S.; Islam, S.U. Transition from steady to unsteady state flow around two inline cylinders under the effect of Reynolds numbers. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2018, 40, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeeb, E.; Haider, B.A.; Sohn, C.H. Influence of rounded corners on flow interference between two tandem cylinders using FVM and IB-LBM. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 2018, 28, 1648–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishne Gowda, Y.; Ravindra, H.; Vikram, C. Effects of Corner Cutoffs on Flow Past Two Square Cylinders in a Tandem Arrangement. In Proceedings of the ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Houston, TX, USA, 9–15 November 2012; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 45233, pp. 643–650. [Google Scholar]

- Aboueian, J.; Sohankar, A. Identification of flow regimes around two staggered square cylinders by a numerical study. Theor. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 2017, 31, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Mittal, S.; Biswas, G. Flow past a square cylinder at low Reynolds numbers. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2011, 67, 1160–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Eswaran, V. Heat and fluid flow across a square cylinder in the two-dimensional laminar flow regime. Numer. Heat Transf. Part A Appl. 2004, 45, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichaux, J.; Balachandar, S.; Vanka, S. Three-dimensional Floquet instability of the wake of square cylinder. Phys. Fluids 1999, 11, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; De, A.; Carpenter, V.; Eswaran, V.; Muralidhar, K. Flow past a transversely oscillating square cylinder in free stream at low Reynolds numbers. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2009, 61, 658–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.K.; Chhabra, R.; Eswaran, V. Two-dimensional unsteady laminar flow of a power law fluid across a square cylinder. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2009, 160, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiman, R.K.; Sen, S.; Gurugubelli, P.S. A fully implicit combined field scheme for freely vibrating square cylinders with sharp and rounded corners. Comput. Fluids 2015, 112, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Alam, M.M. Intrinsic features of flow past three square prisms in side-by-side arrangement. J. Fluid Mech. 2017, 826, 996–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankadasu, A.; Vengadesan, S. Interference effect of two equal-sized square cylinders in tandem arrangement: With planar shear flow. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2008, 57, 1005–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithun, M.; Kumar, P.; Tiwari, S. Numerical investigations on unsteady flow past two identical inline square cylinders oscillating transversely with phase difference. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2018, 11, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohankar, A.; Norberg, C.; Davidson, L. Low-Reynolds-number flow around a square cylinder at incidence: Study of blockage, onset of vortex shedding and outlet boundary condition. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 1998, 26, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, R.; Rodi, W.; Schönung, B. Numerical calculation of laminar vortex-shedding flow past cylinders. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1990, 35, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, M.; Bernsdorf, J.; Zeiser, T.; Durst, F. Accurate computations of the laminar flow past a square cylinder based on two different methods: Lattice-Boltzmann and finite-volume. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2000, 21, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okajima, A. Strouhal numbers of rectangular cylinders. J. Fluid Mech. 1982, 123, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Tang, T.; Zhou, T.; Cai, M.; Gaidai, O.; Wang, J. High performance energy harvesting from flow-induced vibrations in trapezoidal oscillators. Energy 2021, 236, 121484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkovich, M. Flow Around Circular Cylinders. Volume 1: Fundamentals; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Etminan, A.; Moosavi, M.; Ghaedsharafi, N. Determination of flow configurations and fluid forces acting on two tandem square cylinders in cross-flow and its wake patterns. Int. J. Mech. 2011, 5, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Zhou, Y. Strouhal numbers in the wake of two inline cylinders. Exp. Fluids 2004, 37, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Perkins, N.C. Interference effects on vortex shedding from two square cylinders in a tandem arrangement. Phys. Fluids 1995, 7, 2575–2581. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Lin, M.G. Interactions of wakes behind two square cylinders in a tandem arrangement. J. Fluids Struct. 2003, 17, 387–403. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, C.; Roshko, A. Vortex formation in the wake of an oscillating cylinder. J. Fluids Struct. 1988, 2, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrard, J. The mechanics of the formation region of vortices behind bluff bodies. J. Fluid Mech. 1966, 25, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Re Range | L/D Range | Aerodynamic Parameters | Methodology and Arrangement | Flow Regime and Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firdaus et al. (2023) [43] | 3–150 | 0.5–6.0 | , , , | Vortex Particle Method (2D), tandem configuration | Identified five vortex wake patterns; critical spacing governed by wake merging and shielding effects. |

| Kouchakzad et al. (2023) [44] | 30–150 | 1–6 | , , | Numerical (2D), tandem | Three mean flow patterns reported; hysteresis observed near critical gap spacing. |

| Shui et al. (2021) [45] | 100 | 1.5–9.0 | , , ; phase lag | Finite Element Method (2D), tandem | Six flow regimes identified; vortex impingement induces phase lag and asymmetric shedding. |

| Abid et al. (2024) [46] | 1–150 | 0.5–5 | , , | Lattice Boltzmann Method (2D), offset cylinders | Five flow regimes including steady, periodic, and chaotic states depending on spacing and offset. |

| Sohankar et al. (2020) [47] | 70–150 | 1.0–5.0 | , , , | Finite Volume Method (2D), tandem | Two hysteresis modes reported; inlet shear strongly influences regime transitions. |

| Rao et al. (2008) [48] | ≤190 | 1.0–2.7 | , , | Lattice Boltzmann Method (2D), side-by-side | Observed flip-flop and synchronised shedding regimes. |

| Abbasi et al. (2024) [49] | 250 | 0.25–10 | , | Lattice Boltzmann, in-line rectangular cylinders | Four flow regimes ranging from single slender-body flow to fully separated wakes. |

| Kalsoom et al. (2024) [50] | 150 | 0.1D–21D (control rod length) | , | Lattice Boltzmann, tandem | Four distinct regimes classified based on control rod length variation. |

| Derakhshandeh et al. (2020) [51] | 50–200 | 4.0 | , , | Numerical (2D), tandem | Three wake modes identified as a function of Reynolds number and spacing. |

| Etminan et al. (2010) [52] | 1–200 | 5.0 | , | Finite Volume Method (2D), tandem | Onset of vortex shedding and recirculation region behind the DC examined. |

| Abbasi et al. (2018) [53] | 1–110 | 3.5 | , , | Numerical (2D), in-line cylinders | Identified three wake interference regimes with spacing-dependent transitions. |

| Adeeb et al. (2018) [54] | 100 | 1.5–10 | , | Hybrid LBM–FVM (2D), tandem cylinders | Rounded corners reduced drag and delayed vortex formation in the wake region. |

| Gowda et al. (2012) [55] | 100 | 2, 4, 6 | , | CFD (2D), tandem | Corner modifications significantly influence wake stability and vortex shedding frequency. |

| Kouchakzad et al. (2024) [44] | 30–150 | 1–6 (aspect ratio 1–4) | , , | Numerical (2D), tandem | Three wake modes with spacing-dependent hysteresis observed. |

| Aboueian et al. (2017) [56] | 150 | 0.1–6 | , | Finite Volume Method (2D), staggered | Five flow regimes identified; DC exhibited strong unsteadiness and large-scale vortex structures. |

| Present Study (2025) | 100–200 | 2–7 | , , , , , , , , | 2D Finite Volume Method, tandem configuration | Critical spacing () marks transition between wake shielding and independent shedding; detailed analysis of drag, lift, unsteady lift, vortex dynamics, pressure coefficients, and wake parameters performed. |

| Domain | Domain Size () | Cells | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | 19,700 | 1.7658 | 0.2404 | |

| D2 | 31,380 | 1.6854 | 0.2379 | |

| D3 | 44,108 | 1.6430 | 0.2250 | |

| D4 | 61,212 | 1.6035 | 0.2378 | |

| D5 | 80,300 | 1.5709 | 0.2298 | |

| D6 | 101,216 | 1.5230 | 0.26121 | |

| D7 | 125,416 | 1.5210 | 0.2666 | |

| D8 | 151,416 | 1.5220 | 0.2632 | |

| D9 | 179,016 | 1.5213 | 0.2601 |

| References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sen et al. [57] | 100 | 1.5287 (0.18%) | 0.1928 (3.66%) | 0.1452 (3.83%) |

| Sharma et al. [58] | 100 | 1.4940 (2.09%) | 0.1920 (3.23%) | 0.1488 (1.46%) |

| Robichaux et al. [59] | 100 | 1.5300 (0.26%) | – | 0.1540 (1.99%) |

| Singh et al. [60] | 100 | 1.5100 (1.05%) | – | 0.1470 (2.65%) |

| Sahu et al. [61] | 100 | 1.4880 (2.49%) | 0.1880 (1.08%) | 0.1486 (1.59%) |

| Present study (2025) | 100 | 1.5260 | 0.1860 | 0.1510 |

| Zhu et al. [21] | 150 | 1.4539 (1.50%) | 0.2941 (1.36%) | 0.1530 (4.58%) |

| Jaiman et al. [62] | 150 | 1.4740 (0.24%) | 0.2904 (2.96%) | 0.1565 (2.24%) |

| Zheng et al. [63] | 150 | 1.4678 (1.34%) | 0.2753 (8.60%) | 0.1567 (2.11%) |

| Sharma et al. [58] | 150 | 1.4667 (1.43%) | 0.2913 (2.99%) | 0.1588 (0.88%) |

| Singh et al. [60] | 150 | 1.5160 (2.64%) | 0.2870 (4.18%) | 0.1590 (0.63%) |

| Present study (2025) | 150 | 1.4876 | 0.2905 | 0.1602 |

| References | (UC) | (UC) | (DC) | (DC) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lankadasu et al. [64] | 1.423 | 0.2794 | 1.089 | 1.132 | 0.137 |

| Mithun et al. [65] | 1.595 | 0.2815 | 1.352 | 1.295 | – |

| Present study (2025) | 1.4789 | 0.2994 | 1.2323 | 1.3032 | 0.1356 |

| Re | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 1.5242 | 0.2633 | 0.1859 | 0.1519 | 0.1728 |

| 125 | 1.4949 | 0.3311 | 0.2347 | 0.1571 | 0.2215 |

| 150 | 1.4876 | 0.4105 | 0.2905 | 0.1602 | 0.2760 |

| 175 | 1.4972 | 0.5196 | 0.3673 | 0.1587 | 0.3469 |

| 200 | 1.5170 | 0.6797 | 0.4804 | 0.1515 | 0.4480 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

S, S.R.; Kumar, R.A.; Kumar, K.S. Numerical Investigation of Wake Interference in Tandem Square Cylinders at Low Reynolds Numbers. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2038. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122038

S SR, Kumar RA, Kumar KS. Numerical Investigation of Wake Interference in Tandem Square Cylinders at Low Reynolds Numbers. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2038. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122038

Chicago/Turabian StyleS, Sarath R, R Ajith Kumar, and K Suresh Kumar. 2025. "Numerical Investigation of Wake Interference in Tandem Square Cylinders at Low Reynolds Numbers" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2038. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122038

APA StyleS, S. R., Kumar, R. A., & Kumar, K. S. (2025). Numerical Investigation of Wake Interference in Tandem Square Cylinders at Low Reynolds Numbers. Symmetry, 17(12), 2038. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122038