A Filter and Nonmonotone Adaptive Trust Region Line Search Method for Unconstrained Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The new algorithm

| Algorithm 1. A new filter and nonmonotone adaptive trust region line search method. |

| Step 0. (Initialization) Start with and the symmetric matrix . The constants , , , , , and are also given. Set , . |

| Step 1. If , then stop. |

| Step 2. Solve the subproblems of Equations (18) and (19) to find the trial step , set . |

| Step 3. Compute and , respectively. |

| Step 4. Test the trial step. |

| If , then set , , and go to Step 5. |

| Otherwise, compute . |

| if is accepted by the filter , then ; add into the filter , and go to Step 5. |

| Otherwise, find the step length , satisfying Equations (8) and (9), and set . Then, set |

| , and go to Step 5. |

| Step 5. Update the symmetric matrix by using a modified Quasi-Newton formula. Set , , and go to Step 1. |

3. Convergence Analysis

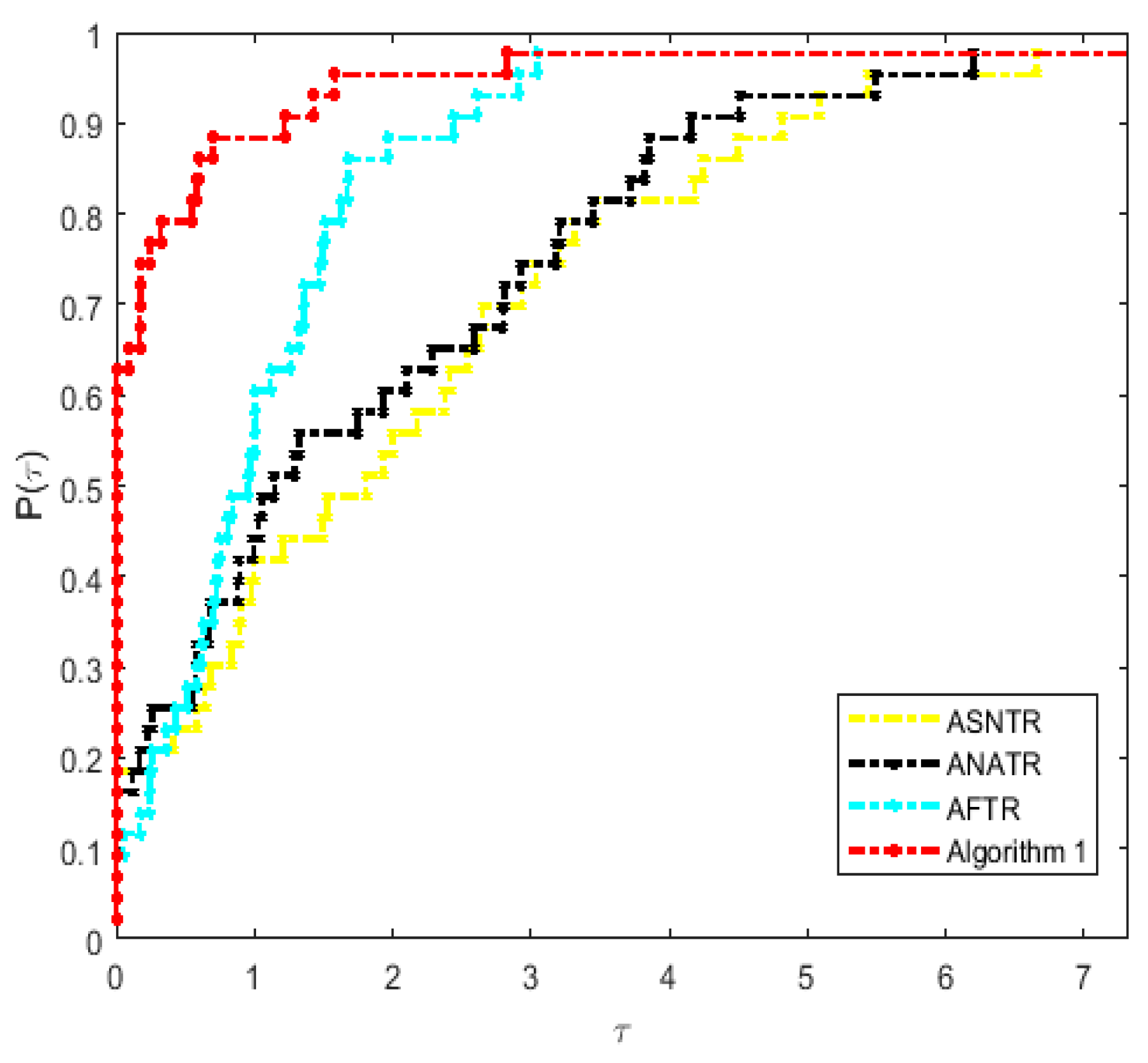

4. Preliminary Numerical Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

function [xstar,ystar,fnum,gnum,k,val]=nonmonotone40(x0,N,npro)

flag=1;

k=1;

j=0;

x=x0;

n=length(x);

f(k)=f_test(x,n,npro);

g=g_test(x,n,npro);

H=eye(n,n);

eta1=0.25;

fnum=1;

gnum=1;

flk=f(k);

p=0;

delta=norm(g);

eps=1e-6;

t=1;

F(:,t)=x;

t=t+1;

while flag

if (norm(g)<=eps*(1+abs(f(k))))

flag=0;

break;

end

[d, val] = Trust_q(f(k), g, H, delta);

faiafa=f_test(x+d,n,npro);

fnum=fnum+1;

flk=mmax(f,k-j,k);

Rk=0.25*flk+0.75*f(k);

dq = flk- f_test(x,n,npro)- val;

df=Rk-faiafa;

rk = df/dq;

flag_filter=0;

if rk > eta1

x1=x+d;

faiafa=f_test(x1,n,npro);

else

g0=g_test(x+d,n,npro);

for i=1:(t-1)

gg=g_test(F(:,i),n,npro);

end

for l =1:n

rg=1/sqrt(n-1);

if abs(g0(l))<=abs(gg(l))-rg*norm(gg)

flag_filter=1;

end

end

m=0;

mk=0;

rho=0.6;

sigma=0.25;

while (m<20)

if f_test(x+rho^m*d,n,npro)<f_test(x,n,npro )+sigma*rho^m*g'*d

mk=m;

break;

end

m=m+1;

end

x1=x+rho^mk*d;

faiafa=f_test(x1,n,npro);

fnum=fnum+1;

p=p+1;

end

flag1=0;

if flag_filter==1

flag1=1;

g_f2=abs(g);

for i=1:t-1

g_f1=abs(g_test(F(:,i),n,npro));

if g_f1>g_f2

F(:,i)=x0;

end

end

end

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

if flag1==1

F(:,t)=x;

t=t+1;

else

for i=1:t-1

if F(:,i)==x

F(:,i)=[];

t=t-1;

end

end

end

dx = x1-x;

dg=g_test(x1, n,npro)-g;

if dg'*dx > 0

H= H- (H*(dx*dx’) *H)/(dx'*H*dx) + (dg*dg')/(dg'*dx);

end

delta=0.5^p*norm(g)^0.75;

k=k+1;

f(k)=faiafa;

j=min ([j+1, M]);

g=g_test(x1, n,npro);

gnum=gnum+1;

x0=x1;

x=x0;

p=0;

end

val = f(k)+ g'*d + 0.5*d'*H*d;

xstar=x;

ystar=f(k);

end

function [d, val] = Trust_q(Fk, gk, H, deltak)

min qk(d)=fk+gk'*d+0.5*d'*Bk*d, s.t.||d|| <= delta

n = length(gk);

rho = 0.6;

sigma = 0.4;

mu0 = 0.5;

lam0 = 0.25;

gamma = 0.15;

epsilon = 1e-6;

d0 = ones(n, 1);

zbar = [mu0, zeros(1, n + 1)]';

i = 0;

mu = mu0;

lam = lam0;

d = d0;

while i <= 100

HB = dah (mu, lam, d, gk, H, deltak);

if norm(HB) <= epsilon

break;

end

J = JacobiH(mu, lam, d,H, deltak);

b = psi (mu, lam, d, gk, H, deltak, gamma) *zbar - HB;

dz = J\b;

dmu = dz(1);

dlam = dz(2);

dd = dz(3 : n + 2);

m = 0;

mi = 0;

while m < 20

t1 = rho^m;

Hnew = dah (mu + t1*dmu, lam + t1*dlam, d + t1*dd, gk, H, deltak);

if norm(Hnew) <= (1 - sigma*(1 - gamma*mu0) *rho^m) *norm(HB)

mi = m;

break;

end

m = m+1;

end

alpha = rho^mi;

mu = mu + alpha*dmu;

lam = lam + alpha*dlam;

d = d + alpha*dd;

i = i + 1;

end

val = Fk+ gk'*d + 0.5*d'*H*d;

end

function p = phi (mu, a, b)

p = a + b - sqrt((a - b)^2 + 4*mu^2);

end

function HB = dah (mu, lam, d, gk,H, deltak)

n = length(d);

HB = zeros (n + 2, 1);

HB (1) = mu;

HB (2) = phi (mu, lam, deltak^2 - norm(d)^2);

HB (3: n + 2) = (H + lam*eye(n)) *d + gk;

end

function J = JacobiH(mu, lam, d, H, deltak)

n = length(d);

t2 = sqrt((lam + norm(d)^2 - deltak^2)^2 + 4*mu^2);

pmu = -4*mu/t2;

thetak = (lam + norm(d)^2 - deltak^2)/t2;

J= [1, 0, zeros(1, n);

pmu, 1 - thetak, -2*(1 + thetak)*d';

zeros (n, 1), d, H+ lam*eye(n)];

end

function si = psi (mu, lam, d, gk,H, deltak, gamma)

HB = dah (mu, lam, d, gk,H, deltak);

si = gamma*norm(HB)*min (1, norm(HB));

end

Partial test function

function f = f_test(x,n,nprob)

% integer i,iev,ivar,j

% real ap,arg,bp,c2pdm6,cp0001,cp1,cp2,cp25,cp5,c1p5,c2p25,c2p625,

% c3p5,c25,c29,c90,c100,c10000,c1pd6,d1,d2,eight,fifty,five,

% four,one,r,s1,s2,s3,t,t1,t2,t3,ten,th,three,tpi,two,zero

% real fvec(50), y(15)

zero = 0.0e0; one = 1.0e0; two = 2.0e0; three = 3.0e0; four = 4.0e0;

five = 5.0e0; eight = 8.0e0; ten = 1.0e1; fifty = 5.0e1;

c2pdm6 = 2.0e-6; cp0001 = 1.0e-4; cp1 = 1.0e-1; cp2 = 2.0e-1;

cpp2=2.0e-2; cp25 = 2.5e-1; cp5 = 5.0e-1; c1p5 = 1.5e0; c2p25 = 2.25e0;

c2p625 = 2.625e0; c3p5 = 3.5e0; c25 = 2.5e1; c29 = 2.9e1;

c90 = 9.0e1; c100 = 1.0e2; c10000 = 1.0e4; c1pd6 = 1.0e6;

ap = 1.0e-5; bp = 1.0e0;

if nprob == 1

% extended rosenbrock function

f = zero;

for j = 1: 2: n

t1 = one - x(j);

t2 = ten*(x(j+1) - x(j)^2);

f = f + t1^2 + t2^2;

end

elseif nprob == 3

% Extended White & Holst function

f = zero;

for j = 1: 2: n

t1 = one - x(j);

t2 = ten*(x(j+1) - x(j)^3);

f = f + t1^2 + t2^2;

end

elseif nprob == 4

%EXT beale function.

f=zero;

for j=1:2: n

s1=one-x(j+1);

t1=c1p5-x(j)*s1;

s2=one-x(j+1) ^2;

t2=c2p25-x(j)*s2;

s3 = one - x(j+1) ^3;

t3 = c2p625 - x(j)*s3;

f = f+t1^2 + t2^2 + t3^2;

end

elseif nprob == 5

% penalty function i.

t1 = -cp25;

t2 = zero;

for j = 1: n

t1 = t1 + x(j)^2;

t2 = t2 + (x(j) - one) ^2;

end

f = ap*t2 + bp*t1^2;

elseif nprob == 6

% Pert.Quad

f1=zero;

f2=zero;

f=zero;

for j=1: n

t=j*x(j)^2;

f1=t+f1;

for j=1: n

t2=x(j);

f2=f2+t2;

end

f=f+f1+1/c100*f2^2;

elseif nprob == 7

% Raydan 1

f=zero;

for j=1: n

f1=j*(exp(x(j))-x(j))/ten;

f=f1+f;

end

elseif nprob == 8

% Raydan 2 function

f=zero;

for j=1: n

ff=exp(x(j))-x(j);

f=ff+f;

end

elseif nprob==9

% Diagonal 1

f=zero;

for j=1: n

ff=exp(x(j))-j*x(j);

f=ff+f;

end

elseif nprob==10

% Diagonal 2

f=zero;

for j=1: n

ff=exp(x(j))-x(j)/j;

f=ff+f;

x0(j)=1/j;

end

elseif nprob==11

% Diagonal 3

f=zero;

for i=1: n

ff=exp(x(i))-i*sin(x(i));

f=ff+f;

end

elseif nprob==12

% Hager

f=zero;

for j=1: n

f1=exp(x(j))-sqrt(j)*x(j);

f=f+f1;

end

elseif nprob==13

%Gen. Trid 1

f=zero;

for j=1: n-1

f1=(x(j)-x(j+1) +one) ^4+(x(j)+x(j+1)-three) ^2;

f=f+f1;

end

elseif nprob==14

%Extended Tridiagonal 1 function

f=zero;

for j=1:2: n

f1=(x(j)+x(j+1)-three) ^2+(x(j)+x(j+1) +one) ^4;

f=f1+f;

end

elseif nprob==15

%Extended TET function

f=zero;

for j=1:2: n

f1=exp(x(j)+three*x(j+1)-cp1) + exp(x(j)-three*x(j+1)-cp1) +exp(-x(j)-cp1);

f=f1+f;

end

end

function g = g_test(x,n,nprob)

% integer i,iev,ivar,j

% real ap,arg,bp,c2pdm6,cp0001,cp1,cp2,cp25,cp5,c1p5,c2p25,c2p625,

% * c3p5,c19p8,c20p2,c25,c29,c100,c180,c200,c10000,c1pd6,d1,d2,

% * eight,fifty,five,four,one,r,s1,s2,s3,t,t1,t2,t3,ten,th,

% * three,tpi,twenty,two,zero

% real fvec(50), y(15)

% real float

% data zero,one,two,three,four,five,eight,ten,twenty,fifty

% * /0.0e0,1.0e0,2.0e0,3.0e0,4.0e0,5.0e0,8.0e0,1.0e1,2.0e1,

% * 5.0e1/

% data c2pdm6, cp0001, cp1, cp2, cp25, cp5, c1p5, c2p25, c2p625, c3p5,

% * c19p8, c20p2, c25, c29, c100, c180, c200, c10000, c1pd6

% * /2.0e-6,1.0e-4,1.0e-1,2.0e-1,2.5e-1,5.0e-1,1.5e0,2.25e0,

% * 2.625e0,3.5e0,1.98e1,2.02e1,2.5e1,2.9e1,1.0e2,1.8e2,2.0e2,

% * 1.0e4,1.0e6/

% data ap,bp /1.0e-5,1.0e0/

% data y(1),y(2),y(3),y(4),y(5),y(6),y(7),y(8),y(9),y(10),y(11),

% * y (12), y (13), y (14), y (15)

% * /9.0e-4,4.4e-3,1.75e-2,5.4e-2,1.295e-1,2.42e-1,3.521e-1,

% * 3.989e-1,3.521e-1,2.42e-1,1.295e-1,5.4e-2,1.75e-2,4.4e-3,

% * 9.0e-4/

zero = 0.0e0; one = 1.0e0; two = 2.0e0; three = 3.0e0; four = 4.0e0;

five = 5.0e0; eight = 8.0e0; ten = 1.0e1; twenty = 2.0e1; fifty = 5.0e1;

cpp2=2.0e-2; c2pdm6 = 2.0e-6; cp0001 = 1.0e-4; cp1 = 1.0e-1; cp2 = 2.0e-1;

cp25 = 2.5e-1; cp5 = 5.0e-1; c1p5 = 1.5e0; c2p25 = 2.25e0; c40=4.0e1;

c2p625 = 2.625e0; c3p5 = 3.5e0; c25 = 2.5e1; c29 = 2.9e1;

c180 = 1.8e2; c100 = 1.0e2; c400=4.0e4; c200=2.0e2; c600=6.0e2; c10000 = 1.0e4; c1pd6 = 1.0e6;

ap = 1.0e-5; bp = 1.0e0; c200 = 2.0e2; c19p8 = 1.98e1;

c20p2 = 2.02e1;

if nprob == 1

%extended rosenbrock function.

for j = 1: 2: n

t1 = one - x(j);

g(j+1) = c200*(x(j+1) - x(j)^2);

g(j) = -two*(x(j)*g(j+1) + t1);

end

elseif nprob == 3

% Extended White & Holst function

for j = 1: 2: n

t1 = one - x(j);

g(j)=two*t1-c600*(x(j+1)-x(j)^3) *x(j);

g(j+1) =c200*(x(j+1)-x(j)^3);

end

elseif nprob == 4

% powell badly scaled function.

for j=1:2: n

s1 = one - x(j+1);

t1 = c1p5 - x(j)*s1;

s2 = one - x(j+1) ^2;

t2 = c2p25 - x(j)*s2;

s3 = one - x(j+1) ^3;

t3 = c2p625 - x(j)*s3;

g(j) = -two*(s1*t1 + s2*t2 + s3*t3);

g(j+1) = two*x(j)*(t1 + x(j+1) *(two*t2 + three*x(j+1) *t3));

end

elseif nprob == 5

% penalty function i.

for j=1: n

g(j)=four*bp*x(j)*(x(j)^2-cp25) +two*(x(j)-one);

end

elseif nprob == 6

% Perturbed Quadratic function

f2=zero;

for j=1: n

t2=x(j);

f2=f2+t2;

end

for j=1: n

g(j)=two*j*x(j)+cpp2*f2^2;

end

elseif nprob == 7

% Raydan 1

for j=1: n

g(j)=j*(exp(x(j))-one)/ten;

end

elseif nprob ==8

% Raydan 2

for j=1: n

g(j)=exp(x(j))-one;

end

elseif nprob==9

% Diagonal 1 function

for j=1: n

g(j)=exp(x(j))-j;

end

elseif nprob==10

% Diagonal 2 function

for j=1: n

g(j)=exp(x(j))-1/j;

end

elseif nprob==11

% Diagonal 3 function

for j=1: n

g(j)=exp(x(j))-j*cos(x(j));

end

elseif nprob==12

% Hager function

for j=1: n

g(j)=exp(x(j))-sqrt(j);

end

elseif nprob==13

% Gen. Trid 1

for j=1:2: n-1

g(j)=four*(x(j)-x(j+1)+one)^3+two*(x(j)+x(j+1)-three);

g(j+1)=-four*(x(j)-x(j+1)+one)^3+two*(x(j)+x(j+1)-three);

end

elseif nprob==14

%Extended Tridiagonal 1 function

for j=1:2: n

g(j)=two*(x(j)+x(j+1)-three)+four*(x(j)+x(j+1)+one)^3;

g(j+1)=two*(x(j)+x(j+1)-three)+four*(x(j)+x(j+1)+one)^3;

end

elseif nprob==15

% Extended TET function

for j=1:2: n

g(j)=exp(x(j)+three*x(j+1)-cp1)+ exp(x(j)-three*x(j+1)-cp1)-exp(-x(j)-0.1);

g(j+1) =three*exp(x(j)+three*x(j+1)-cp1)-three*exp(x(j)-three*x(j+1)-cp;

end

tic;

npro=1;

%Extended Rosenbrock

if npro==1

x0=zeros (500,1);

for i=1:2:500

x0(i)=-1.2;

x0(i+1) =1;

end

%Generalized Rosenbrock

elseif npro==2

x0=zeros (1000,1);

for i=1:2:1000

x0(i)=-1.2;

x0(i+1) =1;

end

%Extended White & Holst function

elseif npro==3

x0=zeros (500,1);

for i=1:2:500

x0(i)=-1.2;

x0(i+1) =1;

end

%Extended Beale

elseif npro==4

x0=zeros (500,1);

for i=1:2:500

x0(i)=1;

x0(i)=0.8;

end

%Penalty

elseif npro==5

x0=zeros (500,1);

for i=1:500

x0(i)=i;

end

% Perturbed Quadratic function

elseif npro==6

x0=0.5*ones (36,1);

% Raydan 1

elseif npro == 7

x0=ones (100,1);

%Raydan 2

elseif npro==8

x0=ones (500,1);

%Diagonal 1 function

elseif npro==9

x0=0.5*ones (500,1);

%Diagonal 2 function

elseif npro==10

x0=zeros (500,1);

for i=1:500

x0(i)=1/i;

end

%Diagonal 3 function

elseif npro==11

x0=ones (500,1);

% Hager function

elseif npro==12

x0=ones (500,1);

%Gen. Trid 1

elseif npro==13

x0=2*ones (500,1);

%Extended Tridiagonal 1 function

elseif npro==14

x0=2*ones (500,1);

%Extended TET function

elseif npro==15

x0=0.1*ones (500,1);

end

N=5;

[xstar,ystar,fnum,gnum,k,val]=nonmonotone40(x0,N,npro);

fprintf('%d, %d,%d',fnum,gnum,val);

xstar;

ystar;

toc

References

- Jiang, X.Z.; Jian, J.B. Improved Fletcher-Reeves and Dai-Yuan conjugate gradient methods with the strong Wolfe line search. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2019, 328, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, M. A new efficient conjugate gradient method for unconstrained optimization. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2016, 300, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, N. New hybrid conjugate gradient algorithms for unconstrained optimization. Encycl. Optim. 2009, 141, 2560–2571. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Zhang, H.B.; Li, Z.B. A nonmonotone inexact Newton method for unconstrained optimization. Optim. Lett. 2017, 11, 947–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenji, U.; Nobuo, Y. A regularized Newton method without line search for unconstrained optimization. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2014, 59, 321–351. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.Q.; Liu, H.W.; Liu, H.Z. An improved nonmonotone adaptive trust region method. Appl. Math. 2019, 3, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, S.; Babaie-Kafaki, S. A modified nonmonotone trust region line search method. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Ding, X.F.; Qu, Q. A New Filter Nonmonotone Adaptive Trust Region Method for Unconstrained Optimization. Symmetry 2020, 12, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocedal, J.; Yuan, Y. Combining trust region and line search techniques. Adv. Nonlinear Program. 1998, 153–175. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, G.E. A Quasi-Newton Trust Region Method. Math. Program. 2004, 100, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Zhou, Q.H.; Wu, X. A Non-Monotone Trust Region Method with Non-Monotone Wolfe-Type Line Search Strategy for Unconstrained Optimization. J. Appl. Math. Phys. 2015, 3, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, H.C.; Hager, W.W. A nonmonotone line search technique and its application to unconstrained optimization. SIAM J. Optim. 2004, 14, 1043–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, R.M.; Powell, M.J.D.; Lemarechal, C.; Pedersen, H.C. The watchdog technique for forcing convergence in algorithm for constrained optimization. Math. Program. Stud. 1982, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Grippo, L.; Lamparillo, F.; Lucidi, S. A nonmonotone line search technique for Newton’s method. Siam J. Numer. Anal. 1986, 23, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.C.; Wu, B.; Qu, S.J. Combining nonmonotone conic trust region and line search techniques for unconstrained optimization. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2011, 235, 2432–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahookhoosh, M.; Amini, K.; Peyghami, M. A nonmonotone trust region line search method for large scale unconstrained optimization. Appl. Math. Model. 2012, 36, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartenaer, A. Automatic determination of an initial trust region in nonlinear programming. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 1997, 18, 1788–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.S.; Zhang, J.L.; Liao, L.Z. An adaptive trust region method and its convergence. Sci. China 2002, 45, 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Yuan, G.L.; Cui, Z.R. A new adaptive trust region algorithm for optimization problems. Acta Math. Sci. 2018, 38B, 479–496. [Google Scholar]

- Kimiaei, M. A new class of nonmonotone adaptive trust-region methods for nonlinear equations with box constraints. Calcolo 2017, 54, 769–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, K.; Shiker Mushtak, A.K.; Kimiaei, M. A line search trust-region algorithm with nonmonotone adaptive radius for a system of nonlinear equations. Q. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 4, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyghami, M.R.; Tarzanagh, D.A. A relaxed nonmonotone adaptive trust region method for solving unconstrained optimization problems. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2015, 61, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.; Leyffer, S. Nonlinear programming without a penalty function. Math. Program. 2002, 91, 239–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, N.I.; Sainvitu, C.; Toint, P.L. A filter-trust-region method for unconstrained optimization. Siam J. Optim. 2005, 16, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wächter, A.; Biegler, L.T. Line search filter methods for nonlinear programming and global convergence. SIAM J. Optim. 2005, 16, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, W.H.; Sun, W. A filter trust-region method for unconstrained optimization. Numer. Math. J. Chin. Univ. 2007, 19, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, W.; Qi, L. A nonmonotone filter Barzilai-Borwein method for optimization. Asia Pac. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 27, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, A.R.; Gould, N.I.M.; Toint, P.L. Trust-Region Methods, MPS-SIAM Series on Optimization; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, N.Z.; Mo, J.T. Incorporating Nonmonotone Strategies into the Trust Region for Unconstrained Optimization. Comput. Math. Appl. 2008, 55, 2158–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.M.; Chen, L.P. A new family of nonmonotone trust region algorithm. Math. Pract. Theory. 2011, 10, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Andrei, N. An unconstrained optimization test functions collection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 10, 6552–6558. [Google Scholar]

- Toint, P.L. Global convergence of the partitioned BFGS algorithm for convexpartially separable optimization. Math. Program. 1986, 36, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, E.D.; Moré, J.J. Benchmarking optimization software with performance profiles. Math. Program. 2002, 91, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Problem | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASNTR | CPU | ANATR | CPU | AFTR | CPU | Algorithm 1 | CPU | ||

| Extended Rosenbrock | 500 | 2649/1326 | 1867.254 | 1071/840 | 1545.386 | 547/387 | 642.091 | 86/47 | 70.369 |

| Extended White and Holst function | 500 | 13/7 | 26.788 | 5/3 | 6.524 | 5/3 | 2.125 | 3/2 | 0.218 |

| Extended Beale | 500 | 29/15 | 4.386 | 43/22 | 15.351 | 40/36 | 8.532 | 22/17 | 2.953 |

| Penalty i | 500 | 13/8 | 32.186 | 5/3 | 6.593 | 7/4 | 2.176 | 3/2 | 0.171 |

| Pert.Quad | 36 | 153/80 | 0.5523 | 128/67 | 0.4704 | 101/73 | 0.8631 | 86/45 | 0.167 |

| Raydan 1 | 100 | 26/14 | 0.862 | 130/98 | 2.263 | 208/105 | 3.5009 | 82/42 | 0.923 |

| Raydan 2 | 500 | 13/8 | 0.9660 | 13/8 | 0.9966 | 11/6 | 0.9549 | 9/5 | 0.780 |

| Diadonal 1 | 500 | 82/42 | 40.591 | 1459/812 | 1957.794 | 59/43 | 21.091 | 21/11 | 9.107 |

| Diadonal 2 | 500 | 4765/3529 | 1532.176 | 251/198 | 106.641 | 390/201 | 43.252 | 2116/1062 | 430.600 |

| Diagonal 3 | 500 | 1634/933 | 1822.091 | 1389/766 | 1536.226 | 349/288 | 327.056 | 201/101 | 88.049 |

| Hager | 500 | 42/23 | 30.258 | 1418/760 | 270.837 | 87/46 | 45.342 | 51/26 | 14.278 |

| Generalized Tridiagonal 1 | 500 | 63/32 | 5.6490 | 53/28 | 8.349 | 46/24 | 13.419 | 70/36 | 11.163 |

| Extended Tridiagonal 1 | 500 | 25/13 | 0.9857 | 25/13 | 3.448 | 14/10 | 3.2337 | 8/7 | 0.823 |

| Extended TET | 500 | 15/8 | 4.2638 | 15/9 | 1.632 | 17/9 | 2.5044 | 17/9 | 1.452 |

| Diadonal 4 | 500 | 7/4 | 0.3293 | 7/4 | 0.857 | 9/8 | 4.0362 | 5/4 | 0.419 |

| Diadonal 5 | 500 | 106/54 | 43.3048 | 134/112 | 57.032 | 127/106 | 41.096 | 155/79 | 19.024 |

| Diadonal 7 | 1000 | 96/78 | 29.197 | 88/73 | 22.309 | 34/15 | 10.265 | 19/15 | 2.561 |

| Diadonal 8 | 1000 | 159/122 | 18.542 | 133/126 | 43.067 | 76/36 | 6.781 | 27/21 | 1.550 |

| Extended Him | 1000 | 35/18 | 7.150 | 30/16 | 17.975 | 108/87 | 514.843 | 28/18 | 22.572 |

| Full Hessian FH3 | 1000 | 11/6 | 1.755 | 11/6 | 5.555 | 17/13 | 5.1472 | 11/6 | 3.912 |

| Extended BD1 | 1000 | 43/25 | 61.358 | 30/16 | 17.9073 | 35/19 | 23.4119 | 30/19 | 26.971 |

| Quadratic QF1 | 1000 | 287/195 | 157.332 | 293/219 | 0.259 | 400/274 | 87.043 | 197/99 | 43.280 |

| FLETCHCR34 | 1000 | 847/505 | 67.511 | 345/225 | 100.676 | 24/16 | 73.265 | 8/5 | 33.145 |

| ARWHEAD | 1000 | 47/24 | 38.4334 | 29/16 | 24.338 | 64/41 | 38.552 | 24/17 | 18.299 |

| NONDIA | 1000 | 197/104 | 96.176 | 92/47 | 56.432 | 33/23 | 34.726 | 51/35 | 22.318 |

| DQDRTIC | 1000 | 23/12 | 52.102 | 36/19 | 40.949 | 46/37 | 86.265 | 22/15 | 16.526 |

| EG2 | 1000 | 55/30 | 79.991 | 28/16 | 16.042 | 19/19 | 14.169 | 51/26 | 32.424 |

| Broyden Tridiagonal | 1000 | 1978/1488 | 1545.221 | 1553/1288 | 1266.076 | 1226/987 | 782.560 | 754/646 | 456.105 |

| Almost Perturbed Quadratic | 1600 | 2548/2267 | 1960.433 | 2118/1829 | 1543.253 | 1078/718 | 1067.206 | 657/425 | 279.316 |

| Perturbed Tridiagonal Quadratic | 3000 | 1342/1025 | 1672.434 | 1132/876 | 1033.255 | 745/552 | 835.265 | 453/357 | 572.371 |

| DIXMAANA | 3000 | 576/463 | 132.240 | 223/198 | 88.211 | 378/320 | 108.452 | 209/165 | 78.542 |

| DIXMAANB | 3000 | 248/201 | 64.215 | 165/122 | 40.233 | 67/56 | 25.109 | 48/32 | 37.120 |

| DIXMAANC | 3000 | 279/197 | 177.221 | 246/167 | 134.272 | 95/43 | 30.140 | 58/24 | 19.011 |

| Extended DENSCH | 3000 | 673/418 | 476.214 | 533/388 | 309.605 | 254/105 | 199.421 | 87/42 | 219.167 |

| SINCOS | 3000 | 2067/1554 | 1045.301 | 1653/1274 | 836.022 | 337/233 | 472.032 | 275/141 | 165.665 |

| HIMMELH | 3000 | 967/721 | 526.211 | 506/349 | 255.629 | 197/196 | 109.276 | 45/32 | 40.127 |

| BIGGSB1 | 3000 | 3760/2045 | 2321.509 | 2254/1886 | 1308.227 | 1836/1025 | 904.234 | 4051/2381 | 1987.456 |

| ENGVAL1 | 3000 | 1784/1087 | 1643.092 | 587/423 | 960.421 | 63/43 | 243.840 | 58/32 | 167.991 |

| BDEXP | 3000 | 2259/1876 | 978.432 | 1342/978 | 832.013 | 172/137 | 385.439 | 67/43 | 59.276 |

| INDEF | 3000 | 325/209 | 2430.215 | 178/156 | 1023.211 | 34/31 | 721.343 | 19/11 | 479.263 |

| NONSCOMP | 3000 | 264/107 | 1742.856 | 96/47 | 1389.123 | 34/18 | 921.324 | 22/14 | 679.120 |

| QUARTC | 3000 | 167/123 | 643.254 | 332/289 | 921.313 | 22/20 | 425.995 | 67/54 | 356.762 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qu, Q.; Ding, X.; Wang, X. A Filter and Nonmonotone Adaptive Trust Region Line Search Method for Unconstrained Optimization. Symmetry 2020, 12, 656. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12040656

Qu Q, Ding X, Wang X. A Filter and Nonmonotone Adaptive Trust Region Line Search Method for Unconstrained Optimization. Symmetry. 2020; 12(4):656. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12040656

Chicago/Turabian StyleQu, Quan, Xianfeng Ding, and Xinyi Wang. 2020. "A Filter and Nonmonotone Adaptive Trust Region Line Search Method for Unconstrained Optimization" Symmetry 12, no. 4: 656. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12040656

APA StyleQu, Q., Ding, X., & Wang, X. (2020). A Filter and Nonmonotone Adaptive Trust Region Line Search Method for Unconstrained Optimization. Symmetry, 12(4), 656. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12040656