A Machine Learning-Validated Comparison of LAI Estimation Methods for Urban–Agricultural Vegetation Using Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Imagery in Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

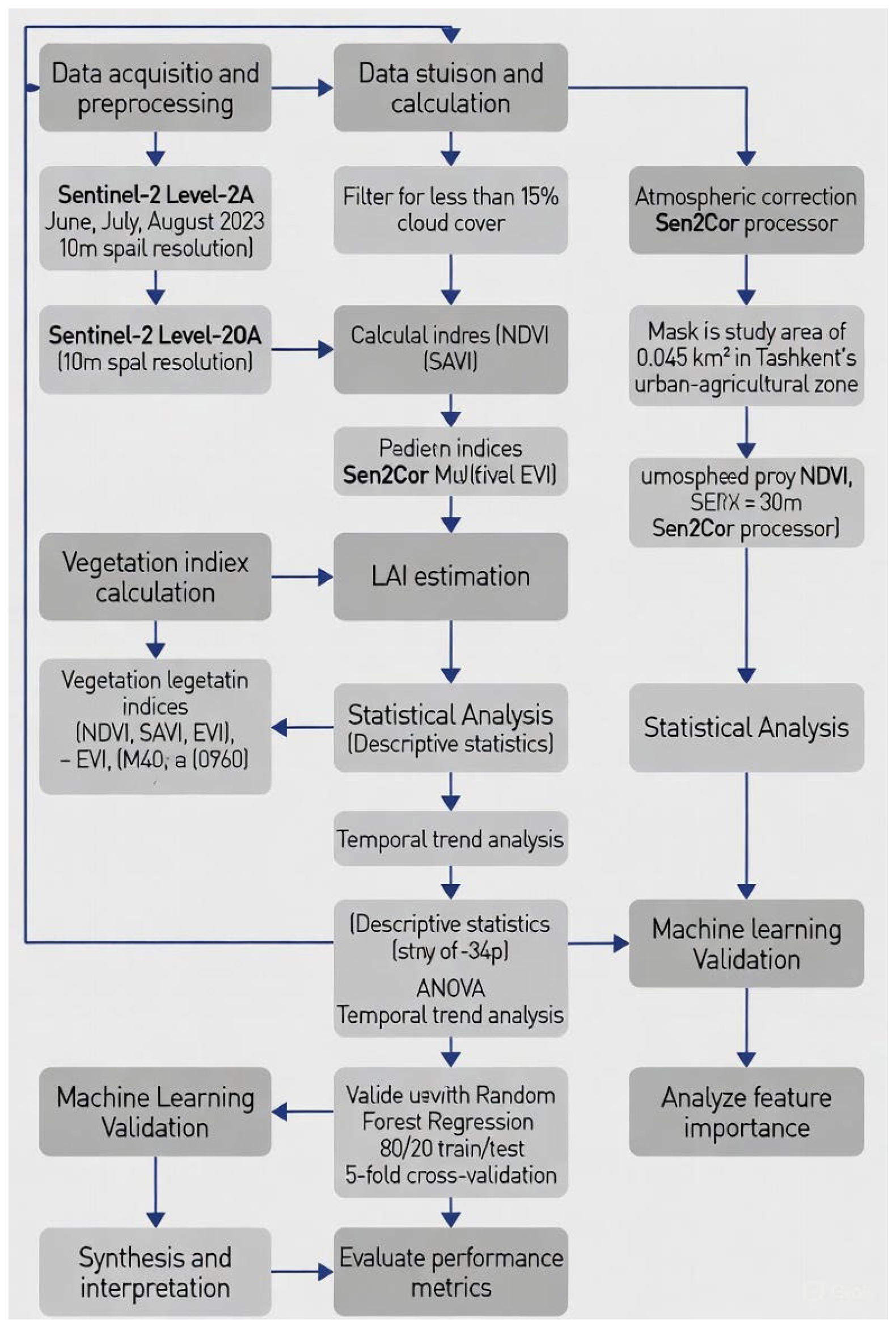

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

2.3. Vegetation Indices and LAI Estimation Methods

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Machine Learning Validation and Feature Importance

3. Results

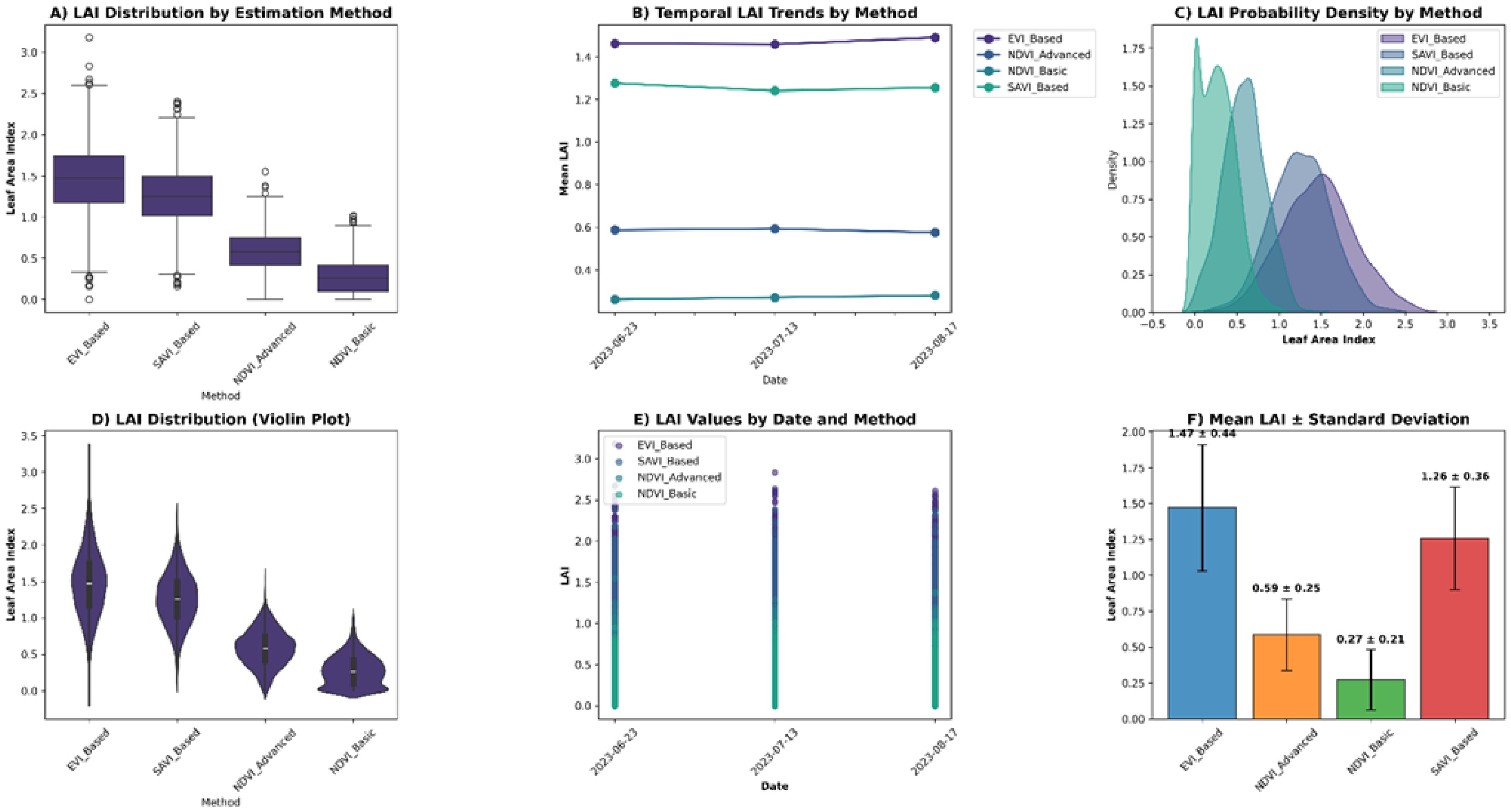

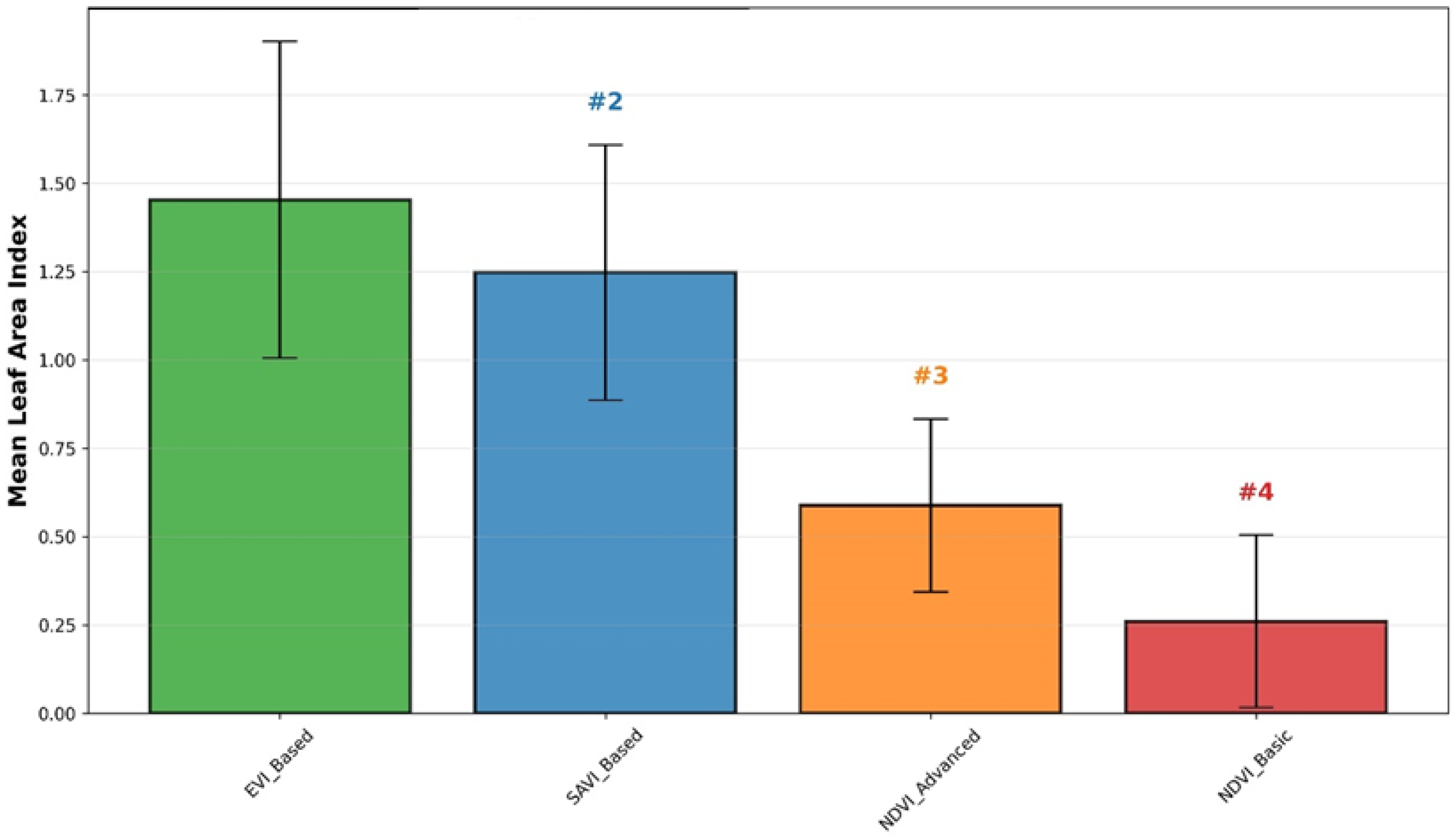

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of LAI Estimates

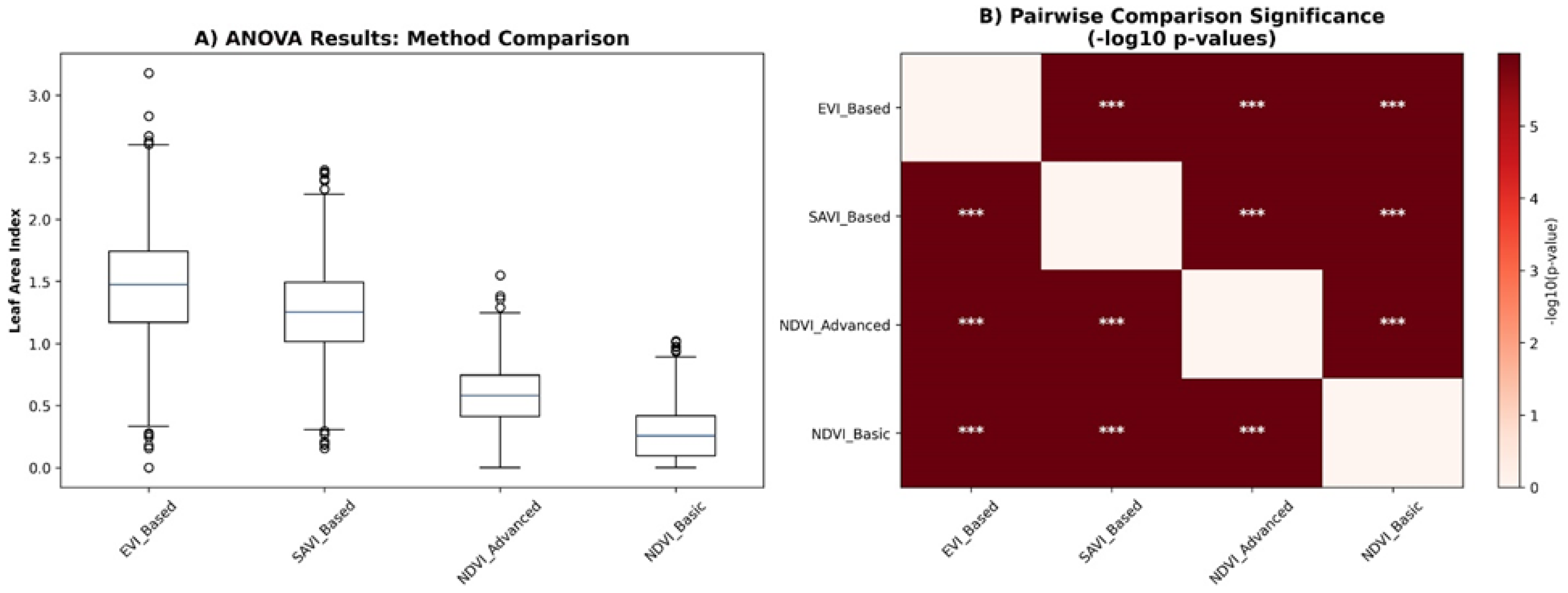

3.2. Statistical Comparison of Methods

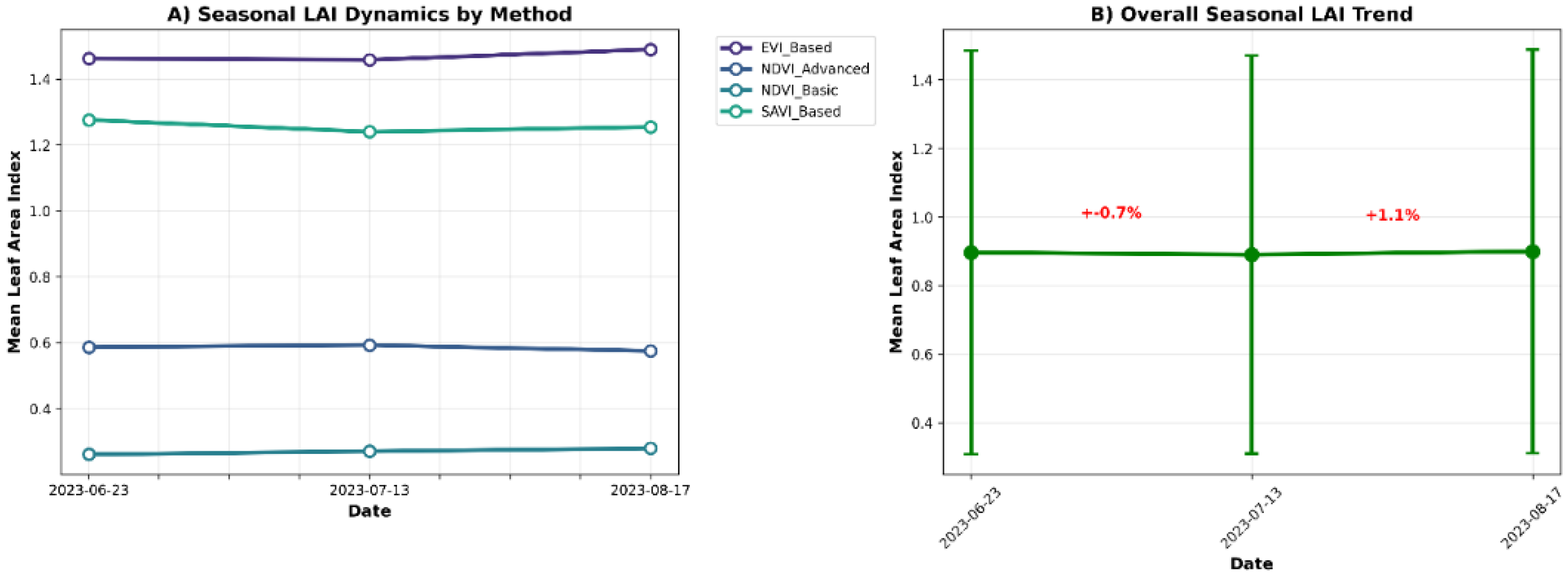

3.3. Temporal LAI Dynamics Across the Growing Season

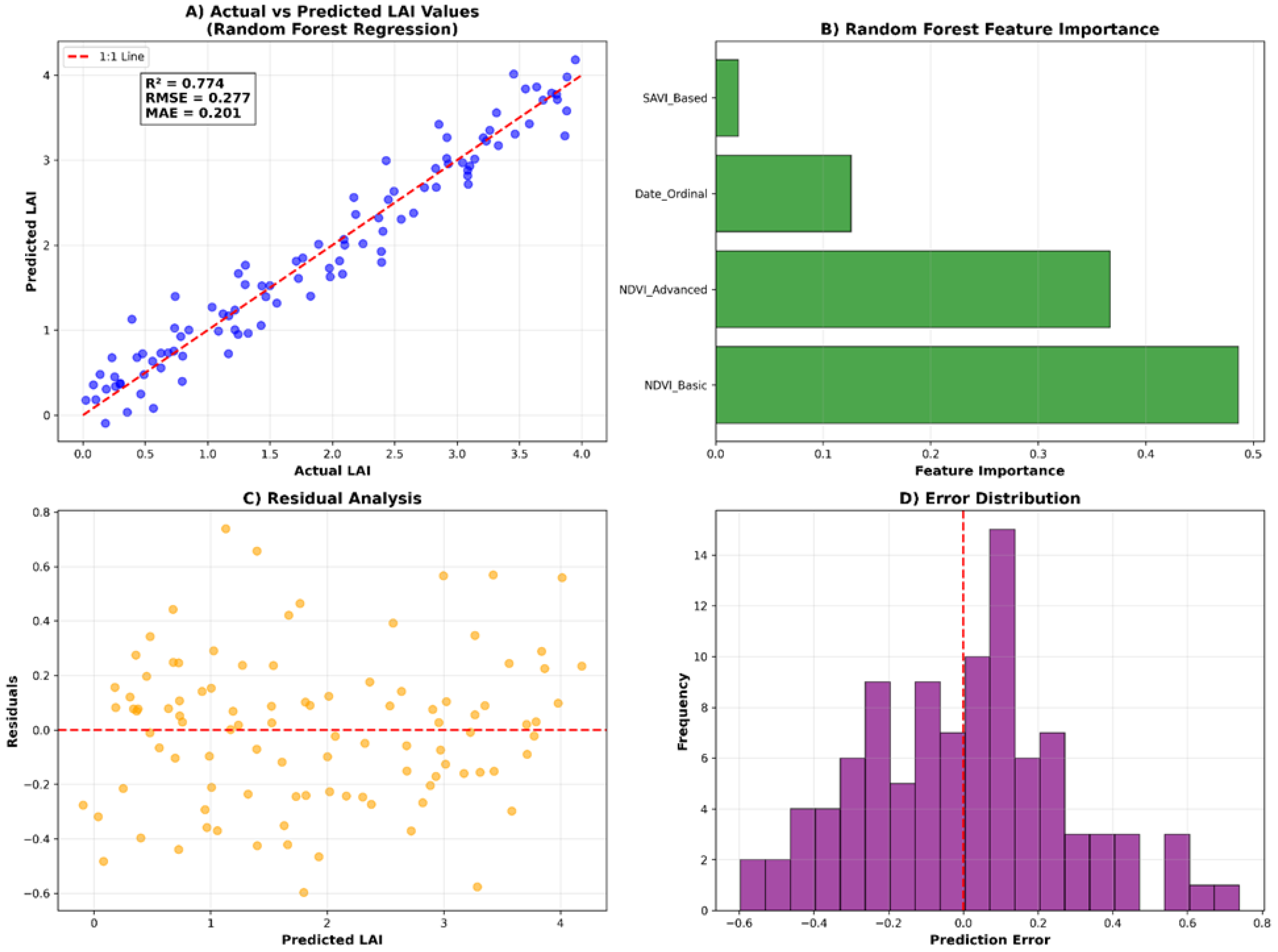

3.4. Machine Learning Validation

4. Discussion

4.1. Method Performance Comparison and Conceptual Interpretation

4.2. Temporal Dynamics and Ecological Relevance

4.3. Validation Approach and Limitations of Internal Consistency

4.4. Methodological Limitations and the Mixed Pixel Challenge

4.5. Practical Implications for Urban–Agricultural Management

4.6. Limitations and Scope

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LAI | Leaf Area Index |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| SAVI | Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index |

| EVI | Enhanced Vegetation Index |

| VI | Vegetation Index |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| MSI | Multispectral Instrument |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| RF | Random Forest |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| APC | Article Processing Charge |

References

- Baret, F.; Guyot, G. Potentials and Limits of Vegetation Indices for LAI and APAR Assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 1991, 35, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, T.N.; Ripley, D.A. On the Relation between NDVI, Fractional Vegetation Cover, and Leaf Area Index. Remote Sens. Environ. 1997, 62, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyns, R.; Canters, F. Mapping of Urban Vegetation with High-Resolution Remote Sensing: A Review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Urban Forest and Ecosystem Services. CSA News 2016, 61, 15–30. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Gren, Å.; Barton, D.N.; Langemeyer, J.; McPhearson, T.; O’Farrell, P.; Andersson, E.; Hamstead, Z.; Kremer, P. Urban Ecosystem Services. In Urbanization, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Challenges and Opportunities; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 175–251. [Google Scholar]

- Huete, A.R. A Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the Radiometric and Biophysical Performance of the MODIS Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, N.; Su, X.; Lu, J.; Yao, X.; Cheng, T.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Tian, Y. Estimating Leaf Area Index with a New Vegetation Index Considering the Influence of Rice Panicles. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; van Leeuwen, W.; Miura, T.; Glenn, E. MODIS Vegetation Indices. In Land Remote Sensing and Global Environmental Change; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 579–602. [Google Scholar]

- Scheiber, L.; Zühlsdorff, V.; Nong, D.H.; Ngo, T.S.; Downes, N.K.; Bachofer, F.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Garschagen, M.; Reimuth, A. Monitoring Urban Green Space for Climate-Resilient Development in the Face of Rapid Urbanization: A Tale of Two Vietnamese Cities. Remote Sens. Appl. 2026, 41, 101820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, F. A Very High-Resolution Urban Green Space from the Fusion of Microsatellite, SAR, and MSI Images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and Photographic Infrared Linear Combinations for Monitoring Vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyukira, C.; Mhangara, P. Advances in Vegetation Mapping through Remote Sensing and Machine Learning Techniques: A Scientometric Review. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 57, 2422330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raufu, I.O. Exploring the Relationship between Remote Sensing-Based Vegetation Indices and Land Surface Temperature through Quantitative Analysis. J. Bulg. Geogr. Soc. 2024, 50, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, H.; Haghighi, A.T.; Klöve, B.; Luoto, M. Remote Sensing of Vegetation Trends: A Review of Methodological Choices and Sources of Uncertainty. Remote Sens. Appl. 2025, 37, 101500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhou, W.; Dawa, Z.; Wang, J.; Qian, Y.; Wang, W. Quantifying Urban Vegetation Dynamics from a Process Perspective Using Temporally Dense Landsat Imagery. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ding, N. Spatial Effects of Landscape Patterns of Urban Patches with Different Vegetation Fractions on Urban Thermal Environment. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yao, R.; Luo, Q.; Yang, Y. Estimating the Leaf Area Index of Urban Individual Trees Based on Actual Path Length. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamungkas, S. Analysis of Vegetation Index for Ndvi, Evi-2, and Savi for Mangrove Forest Density Using Google Earth Engine in Lembar Bay, Lombok Island. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1127, 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Cloud Cover | Processing Level | Spatial Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23 June 2023 | <15% | Level-2A | 10 m |

| 13 July 2023 | <15% | Level-2A | 10 m |

| 17 August 2023 | <15% | Level-2A | 10 m |

| Method | Description | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| NDVI-Basic Method | A simple linear model [16] | |

| NDVI-Advanced Method | A logarithmic transformation based on radiative transfer theory, more sensitive at higher LAI values [17] | |

| SAVI-Based Method | A linear model incorporating soil adjustment [6] | |

| EVI-Based Method | A linear model utilizing the atmospherically resistant EVI [7]. |

| Method | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Median | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDVI-Basic | 0.292 | 0.264 | 0.000 | 1.291 | 0.245 | 1.1500 |

| EVI-Based | 1.453 | 0.448 | 0.770 | 3.504 | 1.363 | 1.061 |

| SAVI-Based | 1.247 | 0.361 | 0.626 | 2.708 | 1.199 | 0.804 |

| NDVI-Advanced | 0.588 | 0.245 | 0.214 | 1.818 | 0.543 | 1.205 |

| Period | Mean LAI | Std Dev | % Change (from June) |

|---|---|---|---|

| June 2023 | 0.661 | 0.469 | Baseline |

| July 2023 | 0.898 | 0.594 | +35.8% |

| August 2023 | 1.102 | 0.607 | +66.7% |

| Metric | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| R2 | 0.774 | High explained variance |

| RMSE | 0.277 | Low prediction error |

| MAE | 0.201 | High accuracy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mamadaliev, B.; Kranjčić, N.; Khamidjonov, S.; Teshaev, N. A Machine Learning-Validated Comparison of LAI Estimation Methods for Urban–Agricultural Vegetation Using Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Imagery in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Land 2026, 15, 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020232

Mamadaliev B, Kranjčić N, Khamidjonov S, Teshaev N. A Machine Learning-Validated Comparison of LAI Estimation Methods for Urban–Agricultural Vegetation Using Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Imagery in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Land. 2026; 15(2):232. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020232

Chicago/Turabian StyleMamadaliev, Bunyod, Nikola Kranjčić, Sarvar Khamidjonov, and Nozimjon Teshaev. 2026. "A Machine Learning-Validated Comparison of LAI Estimation Methods for Urban–Agricultural Vegetation Using Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Imagery in Tashkent, Uzbekistan" Land 15, no. 2: 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020232

APA StyleMamadaliev, B., Kranjčić, N., Khamidjonov, S., & Teshaev, N. (2026). A Machine Learning-Validated Comparison of LAI Estimation Methods for Urban–Agricultural Vegetation Using Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Imagery in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Land, 15(2), 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020232