Abstract

As protected areas (PAs) expand globally at an accelerating rate, reconciling biodiversity conservation with socioeconomic development in adjacent communities has become a critical challenge for landscape sustainability. This systematic review synthesizes literature (1990–2025) to trace three interconnected transitions: (1) the conceptual evolution from exclusionary to inclusive PA–community paradigms, grounded in shifting perceptions of cultural landscapes; (2) the governance transformation from tokenistic participation to power-sharing co-management frameworks; and (3) the spatial planning progression from fragmented “island” models to integrated protected area networks (PANs) leveraging ecological corridors. Our analysis reveals that disconnected PA–community relationships exacerbate conservation–development conflicts, particularly where cultural landscapes are undervalued. A key finding is that cultural–natural synergies act as pivotal mediators for conservation efficacy, necessitating context-adaptive governance approaches. This study advances landscape planning theory by proposing a rural landscape network framework that integrates settlement patches, biocultural corridors, and PA matrices to optimize ecological connectivity while empowering communities. Empirical insights from China highlight pathways to harmonize stringent protection with rural revitalization, underscoring the capacity of PANs to bridge spatial and socio-institutional divides. This synthesis provides a transformative lens for policymakers to scale locally grounded solutions across global conservation landscapes.

1. Introduction

Against the background of intensifying discussions on resource and environmental protection, striking a scientific balance between natural conservation and community development has emerged as a critical challenge. Establishing protected areas (PAs) is an internationally recognized strategy for preserving ecosystems, biodiversity, and endangered species [1]. According to the latest statistics, PAs account for 17% of the world’s total land area, with developed countries such as the United States and Germany designating over 20% of their national territories as PAs. In China, terrestrial PAs cover approximately 18% of the national land area, achieving the 17% target set by the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) for 2020 [2]. However, reconciling the conflict between PA resource conservation and local community economic development remains one of the most pressing challenges in PA management. This issue is particularly pronounced in developing countries, where the natural resources protected within PAs often serve as the primary means of subsistence and livelihood for local and surrounding communities, creating an inherent tension between conservation and development. In consequence, effectively balancing PA conservation with community development has become a central focus in PA planning and community-based conservation strategies [3,4,5,6,7,8].

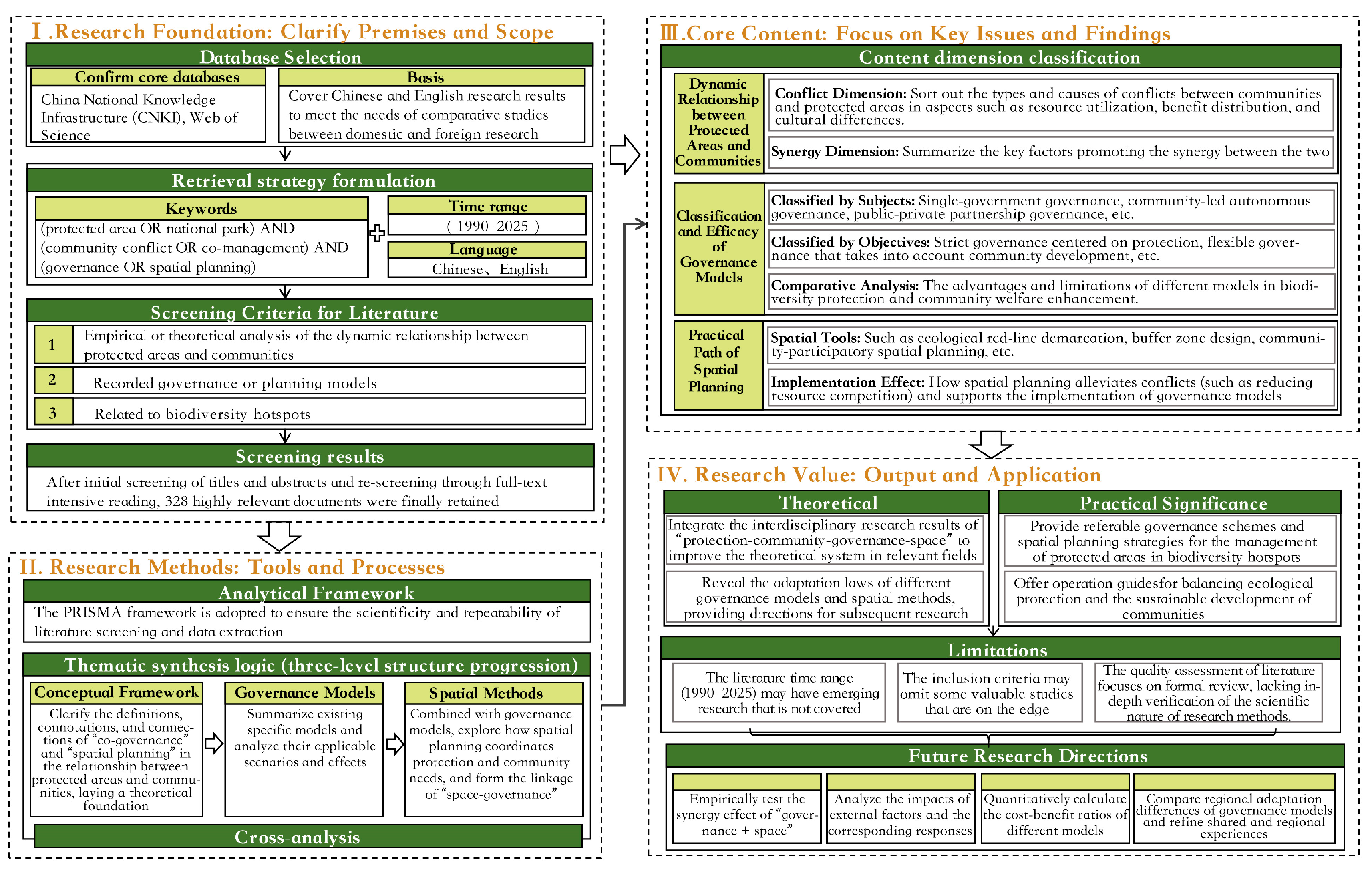

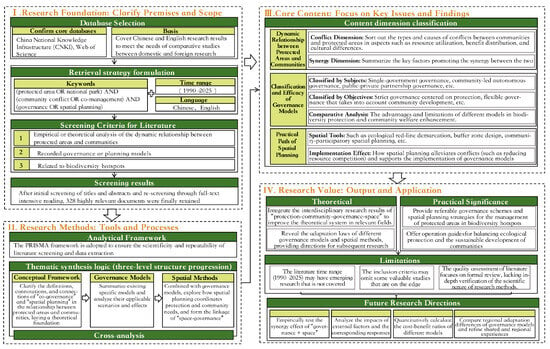

This review employs the PRISMA framework for systematic literature analysis. We screened 328 peer-reviewed studies (1990–2025) from Web of Science, Scopus, and CNKI using the search string: (protected area OR national park) AND (community conflict OR co-management) AND (governance OR spatial planning). Inclusion criteria required (1) empirical/theoretical analysis of PA–community dynamics; (2) documentation of governance or planning models; and (3) relevance to biodiversity-hotspot regions. Thematic synthesis followed a three-tier structure aligning with our research pillars: conceptual frameworks → governance models → spatial approaches (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA framework flowchart for systematic literature analysis.

In the early stages of establishing national parks and nature reserves, the international community generally adopted a construction pathway that separated human beings and nature and excluded local communities from the construction of national parks. It prevented native populations from utilizing the natural resources within the parks. Community residents were either evicted from the protected areas or prohibited or restricted from their traditional way of life [8]. However, in recent years, the “unique landscape resources” protected by U.S. national parks and their emphasis on “American national consciousness” and their claim to “absolute democracy” have evolved in response to the global spread of the national park concept. Both the “sense of American nationhood” and the “spirit of absolute democracy” that it emphasizes are changing as the concept of national parks spreads around the world. In particular, with the rise of social equity consciousness and the transformation of the understanding of wilderness, the planning concept of separating protected areas from community space, which directly deprives residents of their traditional rights of use and ownership of the land in the construction and development of nature reserves, has gradually been questioned [9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

By the late 20th century, an increasing number of studies began to challenge the notion that the natural ecosystems within global protected areas (PAs) have been preserved solely due to a lack of human intervention. Many regions previously regarded as “Wilderness” often bear traces of human activity [14]. Humans are not inherently destructive to nature; in many cases, local communities, through long-term interactions with ecosystems, have contributed to a process of “co-evolution between humans and nature” [9,15,16]. Over the course of more than a century of exploration, scholars have gradually recognized that PA conservation should positively incorporate local communities rather than excluding them. Sustainable conservation can only be achieved by enhancing community awareness of resource protection, fostering confidence in PA-related cultural values, empowering local residents, and securing their recognition and support for PA governance frameworks [6,10,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. As a result, the discourse on reconciling PA–community relationships has increasingly become a focal point in global research and practice concerning national parks and PAs [22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

Despite the ongoing global expansion of expanded protected areas (PAs), integrative frameworks reconciling biodiversity conservation with rural community development remain underdeveloped—particularly in regions like China, where high population density intersects with conservation priorities. To bridge this gap, we propose adapting biodiversity corridor models to establish rural landscape networks embedded within PA matrices. We also propose and evaluate three practical, implementable solutions that constitute the core of our analytical framework. (1) Community Conservation Trust Funds: Legally established, endowment-based financing mechanisms to ensure long-term, transparent revenue-sharing from tourism and ecosystem services, directly compensating for restricted resource access. (2) Spatial Zoning with Cultural Gradients: Replacing rigid “wilderness” buffers with multifunctional zones that recognize and legally protect culturally significant practices (e.g., traditional harvesting, sacred groves) within a broader ecological matrix. (3) Embedded Participatory GIS (ePGIS) Platforms: co-producing high-resolution land-use plans with communities using accessible digital tools to formally integrate local knowledge and preferences into PA zoning from the outset, preventing conflict.

2. Conceptual Evolution: From Exclusion to Inclusion

2.1. Community as Visual Landscape Component (19th Century)

The concept of the national park first emerged in the 19th century in the U.S. The United States of America was in a considerable period of all-around rise: economically, from a backward colonial agricultural producer, it jumped to become the world’s largest exporter of products and services; the population grew from 5.31 million in 1800 to 75.99 million in 1900, and the rate of urbanization grew from 5% in 1870 to 51% in 1920; and culturally, transcendentalist philosophy and literature, represented by Emerson, Thoreau, and others, began to emerge, clearly distinguishing it from the culture of continental Europe [26]. This historical background established the foundation for the national park concept.In the spring of 1832, during a trip to the Dakotas, the American artist George Catlin witnessed the profound impact of western expansion on Native American communities, wildlife, and wilderness landscapes. Deeply concerned by these transformations, he proposed a visionary conservation concept: “by some great protecting policy of government… in a magnificent park… A nation’s park, containing man and beast, in all the wild[ness] and freshness of their nature’s beauty!” This early vision notably included both Indigenous peoples and wildlife as essential components of protected areas, though this inclusive approach was rarely implemented in subsequent park establishment. In 1872, Catlin’s vision was realized, and the U.S. Congress established the Yellowstone area, now located in northwestern Wyoming, as a public park. Yellowstone is considered the world’s first national park. Following the United States, the national park concept and model were soon absorbed and carried forward by other nations, such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Subsequently, national parks were established in South Africa, Japan, and other nations. The emergence of the concept of national parks can be seen from the fact that national parks originated from a rational reflection on the large-scale exploitation of nature by humanity. The original intention of the national park concept was to protect Indian civilization, wildlife, and wilderness, not to exclude human factors, especially Aboriginal communities [27,28]. However, at this stage, due to the lack of deep human understanding of the relationship between human beings and nature, the object of protection of national parks is the visual landscape resources in the protected area, including natural landscapes and cultural landscapes created by aboriginal people, mainly to protect the visual aesthetic value of the landscape.

The origins of the national park concept are indeed complex and often romanticized. Although early visionaries such as George Catlin (1832) [29] articulated an ideal that explicitly included the preservation of Indigenous cultures alongside wildlife and wilderness—envisioning a park “containing man and beast”—its practical implementation was immediately subverted by the dominant colonial and socio-political paradigms of the 19th century. Consequently, a significant disconnect emerged between the early inclusive rhetoric and the exclusionary practices that followed. The establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872, while a landmark event, serves as a primary counterexample: it entailed the forcible displacement of the Shoshone, Bannock, and other Native American tribes who had inhabited the region for millennia, fundamentally undermining the professed goal of protecting Indigenous civilization. This analysis thus reframes the historical narrative: national parks emerged from a dualistic foundation—an idealized, inclusive vision co-opted by an exclusionary, wilderness-centric model of protection that systematically marginalized Indigenous peoples. This paradox is critical for understanding the historical roots of contemporary PA–community conflicts.

2.2. Community as a Negative Factor Stage: The Relationship Between PAs and Communities from the 1930s to the 1970s

During the 1930s, conservationists adhered to the paradigm of isolating humans from nature and proposed an exclusionary protection method that rejected human communities. This method, represented by the United States, has been popularized in many countries and regions such as Australia and Africa. The core characteristic is that human intervention in PAs would only harm resource and environmental protection, and that relocating Indigenous communities outside the park prevents the use of natural resources by the community, completely excluding community interests, and attempting to protect the original state and natural processes of nature entirely are typical practices [30]. For example, PAs in Africa allow prize-hunting activities during the breeding period of prey, and hunting or obtaining other survival resources in the area by local community residents is considered illegal. People have been relocated from the areas where they have lived for generations, and some PAs have even set up physical barriers to enhance isolation from community residents.

During this period, national parks were often managed through conservation and management policies that disregarded the needs of local people and excluded Indigenous communities from the parks. They prevented communities from utilizing the natural resources within them. For example, in the early days of the United States, national parks were considered common national assets, with national and regional values prevailing over the individual interests of residents and aboriginal communities, which were often relocated outside the parks. This model of national park management, which denies community participation, has had a negative social impact, with Indigenous groups in the area becoming marginalized from the development of the national parks (IUCN, 2004 [31]), and the exclusionary paradigm of conservation has brought about far-reaching social tensions.

2.3. From Excluding Communities to Inclusive Communities: Evolution of the Relationship Between PAs and Communities Since the 1970s

Since the 1970s, the objects protected by national parks have undergone significant changes, and ecosystems and biodiversity have gradually become important components of national park protection [30,32,33]. This paradigm shift was catalyzed by UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (MAB) program in 1970, which gave impetus to the concept of biosphere reserves and further promoted integrated linkages between reserve management and community residents. The content discussed at the World Parks Congresses organized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) also reflects the broader transition in the concept of protected land construction from emphasizing simple protection to focusing on the sustainable relationship between PAs and communities (Table 1). The national park plans established by IUCN also allow for diversified land use and the participation of local community residents [34]. The rights and perspectives of Indigenous peoples are increasingly being valued, and the relationship between PAs and communities has developed in inclusively, with European countries as representatives. For instance, the establishment of PAs in the UK does not eliminate the existing human land relationship to maintain natural wilderness, but adopts a landscape conservation approach. Respecting the long-term land ownership order and landscape characteristics formed during the construction of natural reserves and national parks, and the interests of local community residents, is the core content of the management of PAs. With the development of PAs and the continuous deepening of case studies, inclusive thinking is gradually being valued around the world [4,35].

Table 1.

Summary of the main content of the IUCN World Parks Conference [34].

Under the trend of diversifying the conservation objectives of national parks and nature reserves, and focusing on community participation, the construction of national parks is no longer a simple division of the parks to form “islands” isolated from neighboring communities. Since the early 1980s, there have been two prominent trends in the management of natural resources and PAs internationally: one is to focus on the participation of community residents in management, and the other is to seek a balance between resource protection and the development of communities within and near the area. Under the influence of this trend, the prohibition on human activities in protected areas has become an outdated concept. The concept of protected area management, which considers both ecological protection and the well-being of residents, has garnered increasing attention [36,37]. The concept of planning and management of PAs that balances ecological protection and the survival of community residents is increasingly being valued. However, since the protected natural resources or ecosystems within PAs are often the primary source and reliance for production and life for residents within the park or surrounding communities, a natural contradiction arises between the protection of natural ecosystems within the park and the economic and social development of the community. This contradiction is particularly acute in PA and national parks with well-established communities. The organic integration of the main body of this contradiction with the construction of national parks has become an important component of the sustainable development of PAs, and communities have gradually become a key participating force in the planning and management of national parks [38,39].

3. Governance Transformation: Toward Collaborative Models

3.1. “Community Participation” PA Governance Model

Communities and residents within and surrounding national parks are integral components in conserving the natural and cultural systems of these protected areas, serving as key stakeholders in the governance and management of national parks and protected areas. Community participation has emerged as a core principle in the global paradigm of protected area governance. As emphasized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the sustainability of national park management plans can only be realized through active community engagement. Community participation stands in contrast to centralized government control and top-down management approaches. Numerous studies attribute biodiversity loss to the inefficacy of state-led conservation strategies and the antagonistic attitudes of local communities toward the adverse impacts of protected areas. To reconcile this conflict, viable interventions include providing economic incentives and participatory decision-making opportunities for residents [5,40]. A defining feature of community participation lies in its direct linkage of protected areas with local communities to achieve the dual objectives of conservation and development. This approach ensures that biodiversity preservation and economic growth are mutually reinforcing [41]. The socioeconomic interests of communities are intrinsically tied to the sustainable use of natural resources. Through active engagement, residents regain agency over resource governance, enhance their decision-making capacity, and secure tangible benefits from the sustainable management and utilization of natural resources [22,42,43]. In practice, community participation in national park management manifests in various forms. According to the level of participation, community participation can be divided into three modes: top-down external management, informal consultation, and direct consultation.

A typical example of top-down foreign operations is in American national parks, where community residents reside and use designated resources within a limited range. Park management agencies do not typically seek decision-making advice from community residents on national park planning and development plans. Advisory committees, however, are an important way for community residents to participate in national park management, which can be divided into two forms: formal consultation and informal consultation [44] (Table 2). Informal consultations require a certain degree of interaction between national park managers or operators and community residents, including meetings between park managers and representatives of community residents. These meetings are not scheduled at a fixed time, and there is no formal advisory committee to organize them, unlike in Taiwan’s Yushan National Park. The formal consultation requires the establishment of a National Park Advisory Committee, in which community residents are represented in proportion to their population. Regular meetings are held, and residents participate in discussions about national park planning and management plans. For example, Xueba National Park in Taiwan, China, has established an Aboriginal Advisory Committee to ensure the right of community residents to participate. Regardless of whether consultations are formal or informal, community residents can only provide advice and opinions, acting as consultants or meaningful advisors. Community residents cannot control whether opinions or suggestions are adopted or not [44,45].

Table 2.

Primary forms of community participation in governance in protected areas.

3.2. Community Co-Management (CBCM) Model

The early paradigm of “human park separation” in PAs has led to intense community conflicts, and participatory community governance has faced challenges such as low enthusiasm and weak participation [17,46,47,48]. The international human rights movement calls for the restoration of the land rights of Indigenous peoples who have been expelled. The 2003 World Parks Congress and the 2007 World Heritage Committee both emphasized the need to strengthen awareness of community values and protect their rights. In 2013, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) published “Guidelines for Protected Area Governance: From Understanding to Implementation”, which classified protected area governance into four types: governance by government, shared governance, private governance, and community governance. At the implementation level, community co-management has been continuously trialed and refined, emerging as a widely accepted governance model for protected areas in countries such as Australia, Indonesia, Belize, Vietnam, and the Philippines [49].

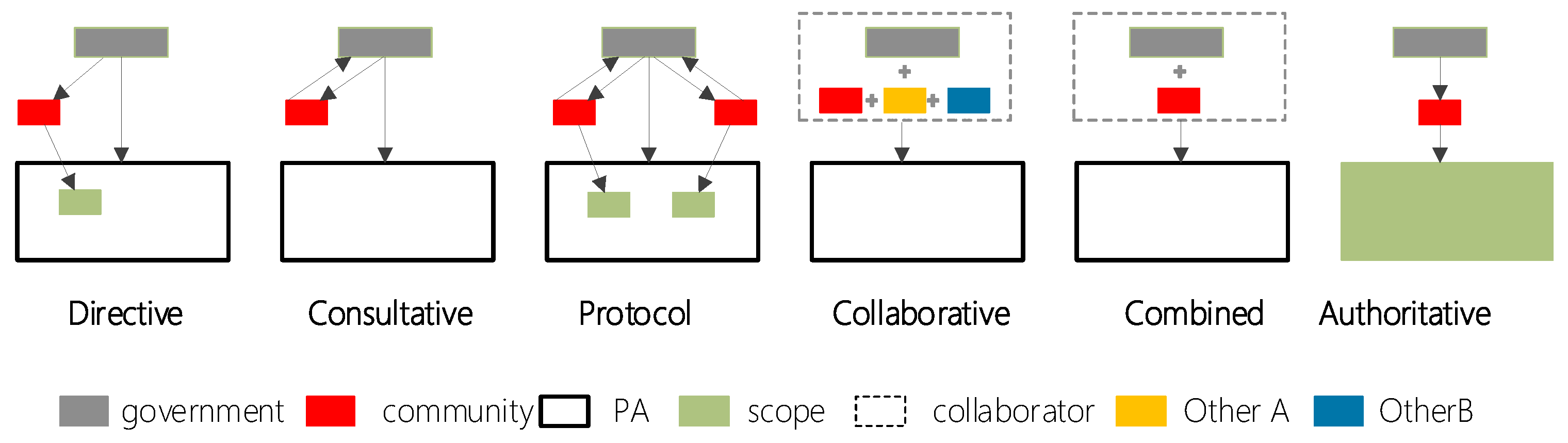

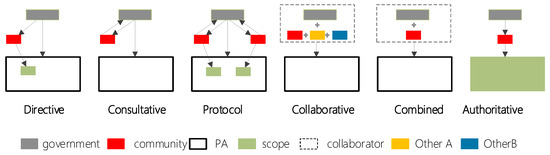

Community co-management (CBCM) lacks a universally accepted definition due to significant variations in its conceptualization and implementation across nations with diverse socio-political contexts. It is alternatively termed participatory management, collaborative management, multi-stakeholder governance, round-table governance, or shared governance. Conceptually, CBCM describes a governance framework in which stakeholders engage in protected area (PA) management activities through sustainable approaches [50]. Operationally, it refers to formal agreements co-developed by legally authorized governmental agencies and all stakeholders to delineate and safeguard their respective responsibilities, resource rights, and conservation obligations. These agreements aim to enhance the efficacy of resource management and promote biodiversity conservation, facilitate inter-party communication and mitigate conflicts between management authorities and local communities, and safeguard the fundamental rights of communities and Indigenous peoples while advancing community-led sustainable development. Typical CBCM models comprise six operational frameworks (Figure 2): the Directive model, Consultative model, Protocol model, Collaborative model, Combined model, and Authoritative model [17].

Figure 2.

Typical CBCM models include six operational frameworks.

Despite the absence of a universally agreed definition of community co-management (CBCM) in academia, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN, 1996 [51]) conceptualizes it as a negotiated relationship of rights and obligations among governmental agencies, local communities, resource users, NGOs, and other stakeholders over managed resources or specific territories. Borrini-Feyerabend (2000) [29] defines CBCM as a collaborative arrangement where two or more parties jointly exercise authority, rights, and responsibilities over a territory or its natural resources. Evelyn Pinkerton (2003) [52] posits that CBCM entails the engagement of stakeholders not as trustees but as equal partners in shared governance, ensuring equitable allocation of rights and benefits. Fikret Berkes (2010) [53] frames CBCM as a power-sharing mechanism between governments and community resource users regarding rights and responsibilities. Synthesizing these perspectives, CBCM fundamentally recognizes the residency rights, resource use privileges, and decision-making agency of local communities, while institutionalizing multi-stakeholder participation in governance. This is operationalized through mechanisms such as establishing management committees with reserved community seats in national parks and formalizing long-term agreements to protect participatory rights. Under CBCM, communities share both benefits and responsibilities with other stakeholders, promoting mutual accountability and fostering collective stewardship [50].

Participatory and co-management models are championed as “ideal” solutions because they theoretically address the root causes of PA–community conflict: the exclusion of local agency and the inequitable distribution of conservation costs and benefits. Their normative superiority is built upon three core pillars: By formally recognizing the rights, knowledge, and agency of local and Indigenous communities, these models foster a sense of ownership, transforming communities from adversaries of conservation into active stewards. This dramatically increases compliance with regulations and reduces enforcement costs. Integrating local ecological knowledge (LEK) with scientific monitoring leads to more nuanced, context-sensitive, and thus more effective management decisions. Furthermore, distributed governance structures (polycentricity) enhance the system’s capacity to adapt to ecological and social shocks. They align with international ethical frameworks (e.g., IUCN Guidelines, UNDRIP) that advocate for social equity, environmental justice, and the right to free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC). However, their designation as “ideal” is often aspirational; their success is contingent on fulfilling these demanding preconditions, which is why the manuscript critically examines the paradox of their implementation in contexts lacking strong democratic institutions or where power asymmetries are entrenched.

While formidable, the implementation challenges of participatory and co-management models can be mitigated through targeted, multi-level solutions. For Government Resistance, a proposed solution is to implement phased power-devolution protocols and pilot programs that demonstrate conservation efficacy to skeptical agencies, building trust through tangible results. Legally embedding co-management structures in PA legislation transforms them from voluntary to mandatory. For Financial Shortfalls, a proposed solution is to develop hybrid financing models that pool state funds, payments for ecosystem services (PES), and international conservation grants. Establishing community-led conservation trust funds ensures long-term fiscal autonomy and reduces reliance on unpredictable government budgets. For Community Resistance, a proposed solution is to address historical distrust through independent facilitators and transparent benefit-sharing agreements that guarantee a visible and equitable flow of benefits (e.g., revenue shares, preferential employment) before demanding conservation compliance. A foundational solution is to adopt an adaptive co-management framework, which uses structured feedback loops (e.g., participatory monitoring) to adjust agreements, balancing ecological goals with community priorities iteratively. This transforms challenges into opportunities for building resilient institutions.

4. Spatial Planning Approaches

4.1. Island Model: Advantages and Limitations

The “island-based” approach is also known as the island planning method. It is a form of national park planning that treats PAs as independent “island” units, with clear boundaries with the construction area of the living environment, and is guided by the goal of creating similar “shelters”. In the early stages of the construction of PAs and national parks, there was no concept of zoning. Instead, areas with unique visual scenic resources were designated as larger, independent national parks or nature reserves [54]. At the beginning of the establishment of Yellowstone National Park, the main planning approach was to determine the boundary range of the nature reserve [30]. To protect its internal scenic resources from human disturbance and maintain their original state, the construction of natural reserves excludes relevant factors considered to have a negative impact on protection. It establishes the spatial scope of natural reserves and protects visual landscape resources by delineating regional boundaries. The initial goal of the establishment of the Egmont National Park in New Zealand was also to protect the Egmont Mountains from further encroachment by the expanding agricultural activities of local community residents [55]. Subsequently, as the problems of wildlife conservation in nature reserves, mainly in national parks, gradually became prominent, the conflicts between PAs and surrounding communities became more complex. The threats of land-use changes such as hunting, dam construction, mining, logging, and grazing to PAs became increasingly severe. Many scholars have recognized the shortcomings of “island-style” conservation methods [56,57].

4.2. “Buffer” Conceptual Model

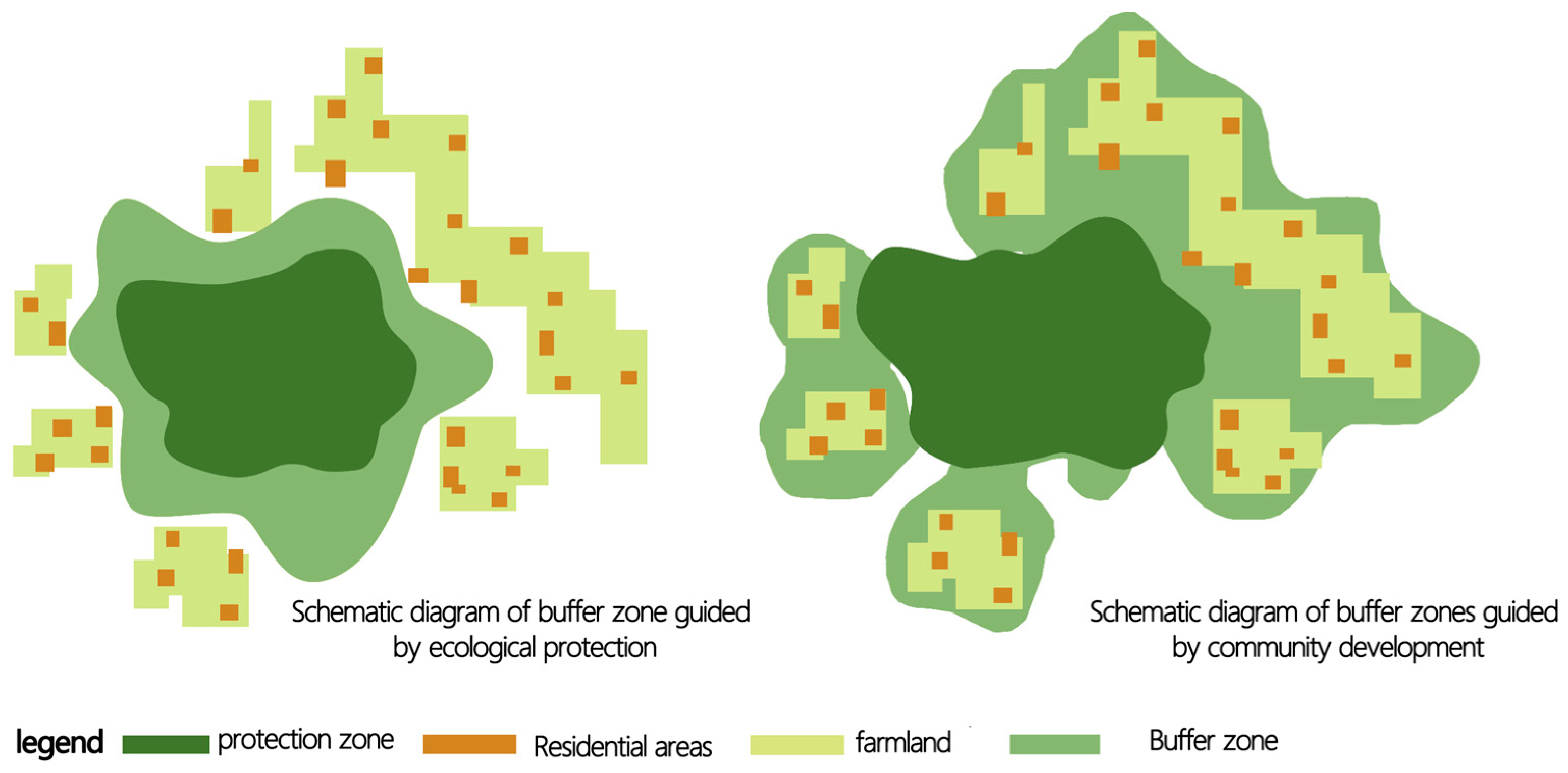

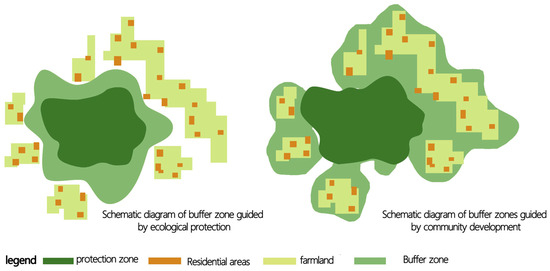

To address the issue of wildlife conservation arising from the “island-style” planning approach in the construction of nature reserves, Wright et al. [58] studied the size, boundaries, and external impacts of parks, and proposed that parks should be large enough to meet the habitat area required by species populations. They also proposed the establishment of a buffer area, which gradually evolved into the concept of a buffer zone. In 1974, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) officially proposed the establishment of buffer zones for biosphere reserves, integrating resource and environmental protection with the needs of local community residents. The buffer zone model was proposed, and the concept of buffer zones was gradually widely applied in nature reserve planning. In 1986, MacKinnon et al. [59] proposed to divide buffer zones into two types based on the goal of wildlife conservation. The first type is called “extension buffering”, which is an extension zone of the core zone to meet the needs of animal and plant habitats. The second type is social buffering, which aims to meet the food and service needs of community residents (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of buffer zones delineated by two different directions in PAs (revised according to reference [18]).

The concept of buffer zones has undergone progressive refinement in the construction and development of nature reserves. With people’s awareness of fairness and local community interests, the social and economic functions of buffer zones are gradually strengthening. A buffer zone can provide ecological buffering and resource protection, limit external impacts outside the PA, and play a significant role in coordinating community development and providing benefits compensation for local residents [60]. Establishing a buffer zone can appropriately compensate for the losses caused by the inability of community residents to enter the core area. Residents within the zone can also increase their income by providing various services for tourists and scientists. However, due to the complexity of land ownership relationships, it is still necessary to plan and design the actual location and area of buffer zones based on the specific nature of land conflicts in different PAs. Although various planning methods exist for buffer zones in current nature reserves, planning and designing buffer zones remains a challenging task. Many PAs still lack sufficient buffer zone areas to effectively protect large wildlife species and sustain the community economy.

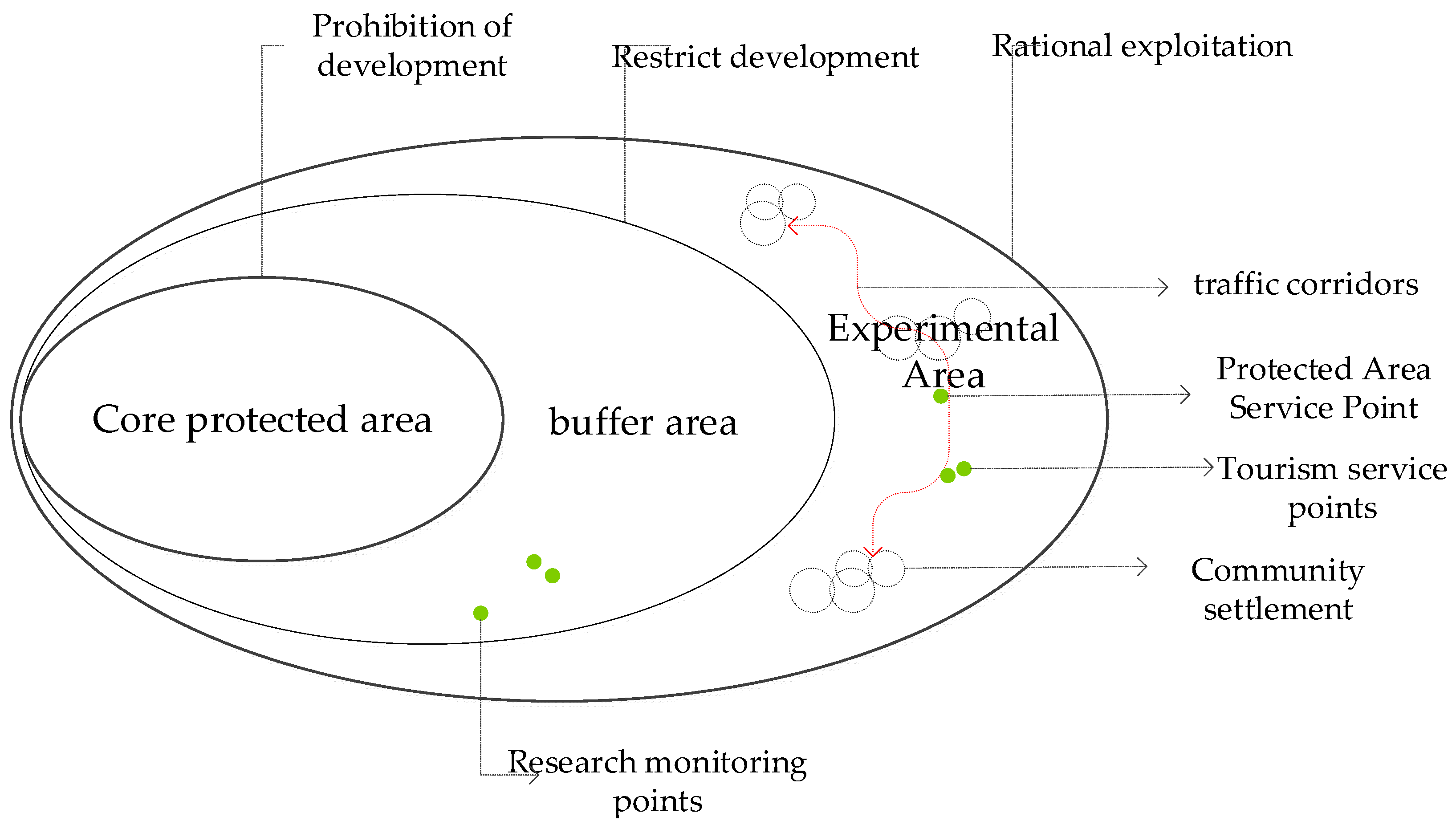

4.3. “Three Zone” Concentric Circle Mode

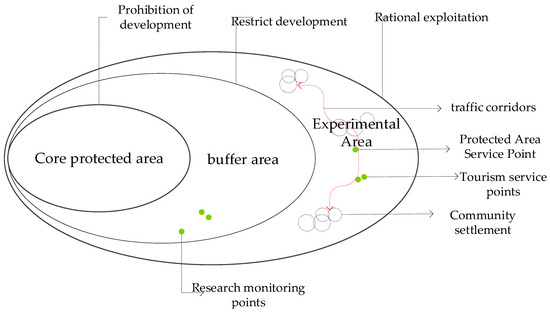

With the development and demand of biological, ecological, and environmental protection movements, scientists have found that “island style” planning and “buffer zone” models are far from sufficient for the protection of ecosystems and biodiversity. To further address the limitations of “island-style” planning in protected areas and optimize insufficient buffer zones, scholarly consensus acknowledges that refined zoning of natural reserves is an effective strategy. This has led to a paradigm shift in protected area (PA) planning, where ecological connectivity between core reserves and adjacent protected landscapes is systematically integrated. It is precisely this emphasis on ecological corridors and inter-PA linkages that has catalyzed the emergence of the protected area network (PAN) framework, a model designed to enhance landscape-scale conservation efficacy and mitigate fragmentation risks [61,62]. In 1970, UNESCO launched the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) program, which proposed a three-zone model for biosphere reserves based on “core zone, buffer zone, and transition zone” to promote comprehensive connections between PA management and community residents (Figure 4). The transition zone, as the peripheral area of a buffer zone, is subject to less stringent management requirements, allowing enhanced public access and utilization while prohibiting polluting industries or large-scale landscape-altering developments. The tri-zonal model (core–buffer–transition) remains widely applied in protected areas primarily aimed at species conservation. Broadly, both the transition zone and later-introduced functional zones, such as recreational areas, can still be categorized under the conceptual scope of buffer zones.

Figure 4.

Concentric circle pattern for spatial zoning planning of nature reserves.

The tri-zonal model, also known as the concentric zoning framework, classifies all lands within a protected area into three zones—core zone, buffer zone, and transition zone —based on the area’s inherent biogeographic and ecological characteristics, recreational capacity, stakeholder interests, and conservation objectives. This zoning system strictly prohibits human interference in the core zone (typically occupying >50% of the total area, where only limited scientific research is permitted), allows minimal low-impact activities in the buffer zone (designed to mitigate external disturbances and supplement core habitat functionality), and designates the outermost transition zone (often encompassing residential and production areas) for localized livelihoods while banning polluting industries. Advocates highlight the model’s simplicity and operational feasibility, arguing that it ostensibly balances conflicting stakeholder demands and minimizes anthropogenic pressures on pristine ecosystems. However, ongoing debates persist regarding the ambiguous definitions, inconsistent management goals, and contested efficacy of this tripartite zoning approach, particularly in achieving the dual mandate of ecological integrity and socioeconomic development.

A critical reappraisal of the “Island Model” of conservation reveals a fundamental trade-off between efficacy and equity. Its primary strength lies in the rapid implementation and unambiguous enforceability of protections, which can safeguard crucial habitats for immediately threatened, critically endangered species (e.g., providing a last refuge for species like the Javan rhinoceros). Furthermore, its clearly demarcated boundaries simplify management and reduce initial administrative costs. However, these short-term ecological advantages are systematically outweighed by profound long-term socio-ecological costs. The model inherently provokes social conflict through community displacement and disregarding customary land rights. Ecologically, it creates vulnerable insular fragments prone to extinction debt and incapable of supporting wide-ranging species or adapting to climate-induced range shifts. Therefore, the “Three-Zone “model emerged not merely to be inclusive but also to practically address these biological limitations of isolation by introducing buffering mechanisms, while simultaneously attempting to mitigate the model’s most severe social externalities through designated zones for limited use.

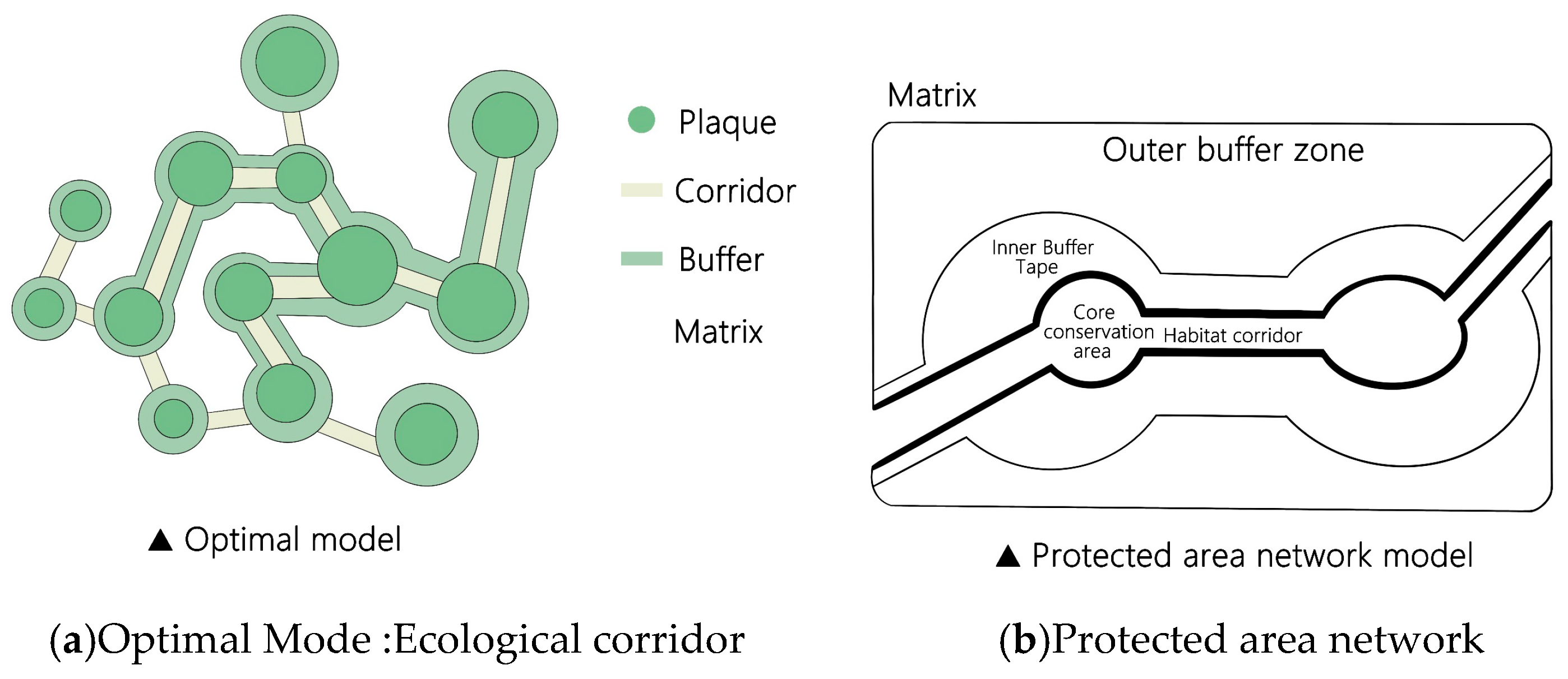

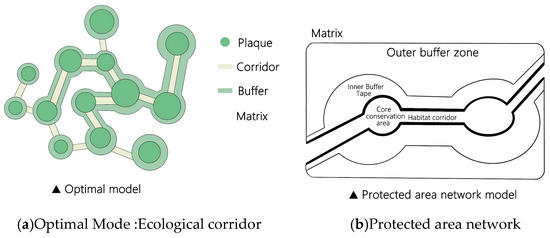

4.4. Ecological Corridor and PA Network Models

With advancing research in ecosystem ecology, there is a growing recognition of the inherent vulnerabilities of fragmented and isolated protected areas (PAs), driving concerted efforts to establish ecological connectivity between these areas [54]. In 1970, U.S. National Park management policies formally institutionalized the ecosystem-based approach [63]. Building on landscape ecology theory, the field of national park and nature reserve planning pioneered the ecological corridor framework (Figure 5a), breaking away from the rigid, compartmentalized planning paradigm centered on zoning approaches. The introduction of ecological corridor concepts has catalyzed a shift toward networked biodiversity conservation, exemplified by the U.S. Protected Area Network (PAN) model (Figure 5b). This framework expands conservation focus from individual PAs to landscape-scale corridor development and integrated network construction at the regional and national levels. Currently, the PAN framework has become a mainstream strategy for biodiversity-centric PA systems, particularly in marine protected areas (MPAs) and wildlife reserves, where connectivity is critical for migratory species and overall ecosystem resilience [64,65].

Figure 5.

Ecological corridor and protected area network (PAN) frameworks for biodiversity conservation [50].

The “Ecological Corridor” and “PA Network” (PAN) models represent a paradigm shift in conservation planning, offering distinct functional advantages over isolated “island” or static zonal approaches. Their advantage is derived from several unique, interconnected features. First, unlike contained models, corridors explicitly maintain or restore functional connectivity across landscapes. This facilitates essential ecological processes—such as gene flow, seasonal migration, and species range shifts in response to climate change—thereby lowering extinction risk in fragmented habitats and increasing the long-term resilience of meta-populations (e.g., jaguar movement in Mesoamerican corridors). Second, PANs operate across multiple spatial scales, from local habitat linkages to continental-scale networks. This allows them to address threats operating at different scales (e.g., local habitat loss vs. regional climate change) in a way that single-PA management cannot. Crucially, these models provide a spatial mechanism to integrate human-modified landscapes (e.g., sustainably managed forests, agroecosystems) into a broader conservation matrix. This framework moves beyond the pure/matrix dichotomy of earlier models, enabling strategic planning that can simultaneously improve habitat connectivity and sustainable livelihood opportunities (e.g., via eco-tourism routes along corridors), thus directly addressing core conservation–livelihood trade-offs. Therefore, the superiority of the PAN framework lies not in the absence of challenges, but in its capacity to address the fundamental limitations of previous models—namely ecological isolation and socio-ecological decoupling—through intentional design.

Successful implementations demonstrate the efficacy of the PAN framework while revealing persistent technical hurdles. A seminal example is the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor, which has improved landscape permeability for jaguars and other neotropical fauna, contributing to a ~25% increase in genetic connectivity between core PAs in Costa Rica and Panama. Similarly, the European Natura 2000 network—the world’s largest coordinated PA network—has been instrumental in improving the conservation status of habitat-specialist species across jurisdictional boundaries. Nevertheless, these models face significant technical and governance challenges:

1. Optimal Design Complexity: Defining ecologically effective corridor width, length, and optimal routing is taxon-specific and requires high-resolution spatial data on species movement and landscape resistance, which are frequently unavailable.

2. Implementation Costs and Land Tenure: Securing connectivity often entails prohibitively expensive land acquisition or long-term easement agreements across numerous private properties, creating massive transactional complexities.

3. Multi-Jurisdictional Governance: PANs typically span multiple administrative regions (e.g., the Yellowstone to Yukon initiative). Achieving consistent management goals and monitoring across these political boundaries remains a foremost challenge, often leading to inconsistent protection and creating weak links in the network. Thus, while superior in theory, the practical success of PANs is contingent on overcoming these pervasive technical and institutional barriers.

4.5. Critical Synthesis

The evolution of protected area (PA) planning models reveals fundamental tensions between ecological imperatives and socio-institutional realities (Table 3). The Island Model, rooted in 19th-century preservation ethics that mythologized “human-free wilderness,” prioritizes administrative simplicity but inherently sacrifices spatial justice by dispossessing communities of ancestral land rights—a legacy critiqued in Section 2.2. Although the Buffer Model attempts reconciliation through economic concessions (e.g., ecotourism quotas), its compensatory logic fails to devolve decision-making power to communities, reducing “social buffering” to an empty slogan that subordinates socio-cultural needs to ecological dogma.

Table 3.

Critical assessment of spatial planning models for protected area–community integration.

The three-zone model, while scientifically legitimized by UNESCO’s MAB program, suffers from contextual incompatibility: its static zoning framework—designed for low-density contexts—ignores climate-induced species migration and exacerbates human–ecological conflicts in high-density regions, such as China, where rigid transition zones cannot accommodate dynamic socio-ecological pressures. Conversely, the PAN/Corridor Model advances landscape planning by acknowledging cultural–natural synergies and replacing exclusionary boundaries with ecological connectivity. Yet its implementation paradoxically depends on polycentric governance—a condition largely absents in authoritarian or conflict-affected states—thus risking theoretical promise over practical applicability in China’s centralized system.

Collectively, these models expose a persistent governance gap: planning frameworks remain constrained by their ontological origins—whether wilderness romanticism (island), technocratic compartmentalization (three-zone), or neoliberal participation (PAN)—rather than centering landscape as a socio-ecological continuum. This necessitates context-driven paradigms like China’s proposed rural landscape network, which reimagines connectivity beyond biological corridors to embed community livelihoods within PA matrices through culturally grounded stewardship.

5. Conclusions and Research Implications

Scholars and scientists across disciplines have extensively researched the intersection of protected area (PA) governance and community development. Globally, the evolution from “island-style” planning to the protected area network (PAN) paradigm has phased out exclusionary approaches that marginalize communities and restrict Indigenous access. Instead, the recognition of community values and promotion of participatory governance in PA planning and management have gradually become foundational tenets in conservation practice. In the 21st century, PA–community relations have shifted from segregation to integration, with PAs increasingly framed as catalysts for regional sustainable development. A recent Science study by Jones et al. [65] reveals that approximately one-third of PA areas worldwide face intensive human pressures, with over half of PAs—particularly in Western Europe, South Asia, and Africa—experiencing significant anthropogenic impacts. This review holds substantial theoretical and methodological implications for conservation science. Theoretically, it challenges the persistent nature–culture dichotomy prevalent in Western PA frameworks by reframing human-modified landscapes not as threats, but as essential, dynamic components of sustainable conservation strategies. It provides a new lexicon for this integration—biocultural corridors, rural landscape networks—that reframes the debate from conflict to coexistence. Methodologically, this study demonstrates the utility of structuring a systematic review along conceptual, governance, and spatial-planning axes to diagnose complex socio-ecological problems. This tripartite framework offers a replicable model for analyzing other conservation dilemmas. Furthermore, by spatializing governance principles (e.g., mapping power-sharing onto corridor design), we provide a translational bridge between institutional theory and on-the-ground spatial planning, moving beyond theoretical critique to generate actionable, spatially explicit models for planners and policymakers.

With the progressive reforms of China’s national park system, the construction of a protected area (PA) network has emerged as a strategic priority. China has been transitioning from exclusionary conservation models—marked by the exclusion of villagers and community relocation—toward community-inclusive approaches, with an increasing number of PAs adopting participatory frameworks such as community co-management and collaborative governance. Nevertheless, China’s PA development faces more complex localized challenges. Geographically, the nation combines the vast territorial expanse and rich natural landscapes of countries like the United States, Canada, and Australia with the high population densities and strained human–environment dynamics seen in Europe, Japan, and South Korea. Temporally, China remains a developing nation where rapid modernization is urgently needed to lift hundreds of millions of rural residents out of poverty, a pressure that has accelerated ecological degradation across its territories. This environmental crisis has compelled the government to prioritize the establishment of PAs under a historical paradigm of “early and extensive demarcation, demarcation before development, prioritizing urgent protection, and gradual refinement” [41]. While effective in curbing habitat loss, this approach has entrenched systemic issues, particularly the unresolved tensions between conservation and rural community development. Concurrently, China is navigating a critical phase of rural transformation. Following initiatives like New Rural Construction, New Urbanization, Traditional Village Conservation, and Characteristic Town Development, the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China introduced the Rural Revitalization Strategy, mandating comprehensive rural modernization by 2050. Key questions remain unresolved: How can rural communities within PAs reconcile conservation imperatives with modernization goals? What specific forms should rural modernization take in ecologically sensitive regions? These dual challenges—balancing ecological integrity with socioeconomic advancement—demand urgent interdisciplinary research to align national conservation objectives with equitable, sustainable rural development.

The establishment of the global PA system has been historically shaped by Western anthropocentric dualism, which institutionalized the exclusion of human activities from PAs and fragmented cultural–natural interactions. Current PA-related research predominantly focuses on biodiversity conservation, ecological theories, and natural resource management, while systematic methodologies for rural community planning within PAs are notably scarce. This imbalance reflects divergent national contexts—sparsely populated countries like the U.S., Canada, and Australia face minimal rural pressures within PAs, whereas densely populated regions like Europe, Japan, and South Korea have resolved mainly rural poverty through modernization. China, however, confronts a unique paradox: its PAs encompass vast, historically rooted rural communities with distinct spatial patterns, yet lack integrative planning frameworks to reconcile conservation with development. Critically, rural community studies lack conservation-aligned paradigms, such as the ecological corridor and protected area network (PAN) models used in biodiversity protection. Through systematic governance and spatial optimization of these corridors, patches, and networks, multi-scale PA conservation could be synergized with rural development goals. This approach aims to achieve two fundamental priorities: enhancing ecosystem integrity while fostering sustainable rural modernization, thereby addressing China’s distinctive challenges of harmonizing biodiversity protection with the socioeconomic needs of its PA-embedded communities.

The suitability of Western-derived models in developing nations hinges not on direct transfer, but on critical and context-sensitive adaptation. Our analysis reveals a systemic contextual misalignment: models predicated on conditions of low population density, stable institutions, and high per-capita conservation funding (e.g., U.S. Wilderness Acts [67], EU Natura 2000 [68]) falter in developing contexts characterized by high demographic pressure, contested land tenure, and urgent poverty alleviation needs. In the case of China, this necessitates a foundational recalibration. (1) Rejecting Purity Paradigms: The Western ideal of “pristine wilderness” is inapplicable. Effective models must instead manage human-dominated landscapes (e.g., agroforestry systems, sacred forests) as integral components of the conservation matrix. (2) Sovereignty-Sensitive Governance: Co-management cannot mirror the NGO-driven advocacy of the West. It must be reconfigured within state-led, vertically integrated governance frameworks that nonetheless create authentic, legally defined spaces for community decision-making (e.g., village cooperatives integrated into PA management bureaus). (3) Spatial Innovation for Density. Planning must prioritize multifunctional landscapes where infrastructure (e.g., ecological corridors) simultaneously enhances biodiversity connectivity and supports sustainable livelihoods (e.g., cultural tourism routes, habitat-friendly farming), as piloted in Qianjiangyuan National Park. Thus, the contribution is not merely about examining suitability, but about providing a framework for the Sino-centric co-production of conservation models, with the proposed rural landscape network serving as one such exemplar.

This synthesis identifies critical pathways for future research, particularly in quantifying socio-ecological trade-offs: (1) Developing standardized metrics to rigorously measure the costs (livelihood restrictions, displacement) and benefits (biodiversity gain, ecosystem service provision) of different PA–community integration models, moving beyond qualitative assessment. (2) Governance Adapter Frameworks: Designing and testing context-specific “governance adapters”—flexible institutional and legal protocols—that enable the translation of co-management principles into functional arrangements within diverse political systems (e.g., centralized states, post-conflict regions). (3) Advanced Spatial Planning Tools: Innovating participatory modeling tools that integrate scenario planning, land-use simulation, and spatial prioritization algorithms to co-design optimal PA network configurations that simultaneously maximize ecological connectivity and minimize social conflict. Prioritizing these lines of inquiry is essential for evolving conservation paradigms from theory to contextually robust practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K.; methodology, Y.K., H.L. and X.Z.; software, H.L.; validation, Y.K. and C.W.; formal analysis, Y.K. and C.W.; data curation, Y.K., H.L. and X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.K., H.L. and X.Z.; visualization, Y.K. and H.L.; supervision, Y.K., H.L., X.Z. and C.W.; project administration, Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Yellow Sea Wetland Research Foundation of Yancheng (Grant No. HHSDKT202415, Y.K.); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52508096, Y.K.); the Basic Research Special Fund (Soft Science Research) of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BK20241661, Y.K.); and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (73rd Grant Program, Grant No. 2023M732641, Y.K.).

Data Availability Statement

This journal adopts the Taylor & Francis Basic Data Sharing Policy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Xu, W.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; Zhang, L.; Hull, V.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Liu, J.; Polasky, S.; et al. Strengthening protected areas for biodiversity and ecosystem services in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, R.M. Upgrading protected areas to conserve wild biodiversity. Nature 2017, 546, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Yang, R. Research on Optimization of Community Planning in National Parks of China—A Case Study of Jiuzhaigou Valley. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 33, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.; Zhong, L.; Zhou, R.; Yu, H. Review of international research on national parks as an evolving knowledge domain in recent 30 years. Prog. Geogr. 2022, 36, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Liang, B. Community Conflicts of the National Park Overseas: Performance, Tracing Origins and Enlightenment. Tour. Trib. 2017, 32, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatiso, T.T.; Kulik, L.; Bachmann, M.; Bonn, A.; Bösch, L.; Freytag, A.; Heurich, M.; Wesche, K.; Winter, M.; Ordaz-Nemeth, I.; et al. Sustainable protected areas: Synergies between biodiversity conservation and socioeconomic development. People Nat. 2022, 4, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.Y.; Huang, Z.D.; Bai, Y. The cooperative development relationship between Nature Reserves and local. Integr. Conserv. 2023, 2, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M. Locked out of national parks. Te Karaka 2014, 63, 23–31. Available online: https://ngaitahu.iwi.nz/opportunities-and-resources/publications/te-karaka/locked-national-parks/ (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Aseres, S.A.; Sira, R.K. Ecotourism development in Ethiopia: Costs and benefits for protected area conservation. J. Ecotourism 2021, 20, 224–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Yang, R. Practices and Trends Analysis of Community Planning for Chinese Natural World Heritage Properties. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2012, 28, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Review on the Settlements Policies of National Parks in England: Take Peak District National Park for Example. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Cao, Y.; Yang, R. Wilderness Protection and Rewilding: Status and Insights. China Land 2019, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford-Learner, N.; Addison, J.; Smallhorn-West, P. Conservation and human rights: The public commitments of international conservation organizations. Conserv. Lett. 2024, 17, e13035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buta, N.; Holland, S.M.; Kaplanidou, K. Local communities and protected areas: The mediating role of place attachment for pro-environmental civic engagement. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2014, 5–6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, F.C.; Espírito-Santo, M.M. Protected areas and territorial exclusion of traditional communities: Analyzing the social impacts of environmental compensation strategies in Brazil. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Han, F.; Ma, R. Progress and Representative Methods in Foreign Sacred Natural Site Conservation from World Heritage Perspective. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 26, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Yang, R. Research on Typical Models of Community-Based Co-management in Worldwide PA. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 27, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, J. Study and Reference on the Protection and Management Planning in Buffer Zone of PA in Nepal. Urban Plan. Int. 2014, 29, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, G. Exploring the Relationship Between Local Support and the Success of Protected Areas. Conserv. Soc. 2013, 11, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.J.; Mu, S.H.; Sui, Y.Z.; Yu, G.X. Research progress on coordinated development between natural protected areas and communities. Nat. Prot. Areas 2024, 4, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, G.S.M.; Rhodes, J.R. Protected areas and local communities: An inevitable partnership toward successful conservation strategies? Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, R. Optimization of Chinese National Park Community Planning Framework Based on Spatio-temporal Difference Analysis. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 36, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Study on Categories and Hotspots of Community Conservation Conflicts in China’s Natural PA: Based on Literature Research. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 26, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, R. The Analysis of the Current Situation and Reform Proposals of Community-based Co-management in China’s Nature Reserves. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 36, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesh, J.P. The National Estate (and the city), 1969–1975: A significant Australian heritage phenomenon. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. Guard Chinese National Parks Against Deterioration. Environ. Prot. 2015, 3, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Song, B.M.; Zhang, X.Y. World national parks: Origins, evolutions and development trends. Natl. Park 2023, 1, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, X.Y.; Wang, L.; Ke, L.N. Wilderness mind and wilderness management in Yosemite National Park. Resour. Sci. 2016, 38, 2192–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Farvar, M.T.; Nguinguiri, J.C.; Ndangang, V.A. Co-Management of Natural Resources: Organising, Negotiating and Learning-by-Doing; GTZ and IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2000.

- Li, B.; Wang, W.; Liu, L.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Q. Effectiveness of the Qilian Mountain Nature Reserve of China in Reducing Human Impacts. Land 2022, 11, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Kothari, A.; Oviedo, G. Indigenous and Local Communities and Protected Areas: Towards Equity and Enhanced Conservation. IUCN. 2004. Available online: https://iucn.org/resources/publication/indigenous-and-local-communities-and-protected-areas-towards-equity-and (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Wei, Y.; Lei, G.C. From biocenosis to ecosystem: The theory trend of conserving ecosystem integrity in national parks. J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 34, 1820–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.C.; Xue, Y.D.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, D.Q. Summary comments on assessment methods of ecosystem integrity for national parks. Biodivers. Sci. 2019, 27, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Dai, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wang, B. Construction of national PA system: A reflection on the Western-based criteria and exploration of a Chinese approach. J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 34, 1807–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolton, S.; Dudley, N. Partnerships for Protection: New Strategies for Planning and Management for Protected Areas; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.4324/9781315071398/partnerships-protection-nigel-dudley-sue-stolton (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Ke, Y.C.; Bai, Y.; Ali, M.; Ashraf, A.; Li, M.; Li, B. Exploring residents’ perceptions of ecosystem services in nature reserves to guide protection and management. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Y.; Min, Q.W. The origin, practice and evolvement of conservation-compatible idea. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 6041–6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Y. The role of communities in the governance of China’s national parks and the consolidation and development of their role. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 2310–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.C.; Zhang, Y.J. Gateway Community Development in American National Parks: Experience and Enlightenment. World For. Res. 2023, 36, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.M.; Newig, J.; Loos, J. Participation in protected area governance: A systematic case survey of the evidence on ecological and social outcomes. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 336, 117593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Stoffelen, A.; Vanclay, F. A conceptual framework and research method for understanding protected area governance: Varying approaches and epistemic worldviews about human-nature relations. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2023, 66, 1393–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Y.; Jiao, W.J. Adapting traditional industries to national park management: A conceptual framework and insights from two Chinese cases. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 133007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petriello, M.A.; Redmore, L.; Sène-Harper, A.; Katju, D. Terms of empowerment: Of conservation or communities? Oryx 2021, 55, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlett, D.; Edwards, J. Beyond prescription: Community engagement in the planning and management of national parks as tourist destinations. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2013, 10, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.N.; Shang, Q.Q.; Zhang, Y.J. Research on Community Participation Mechanism in National Parks Management in China. World For. Res. 2018, 31, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.J. On public participation in the construction of national parks. Biodivers. Sci. 2017, 25, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.G.; Mu, Y.J.; Li, W.L.; Li, T.T. Preliminary Exploration of Co-management of National Parks in China. For. Grassl. Resour. Res. 2020, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.C.; Zhong, L.; Li, B. Research on the Empowerment Levels and Influencing Factors of Community-based Comanagement (CBCM) in China’s Protected Areas. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 39, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.N. Study on Management Mode of Chinese Nature Reserve and Community. Ph.D. Dissertation, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China, 2012. Available online: https://www.dissertationtopic.net/doc/2123490 (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Visiting Lecturer, Wildland Management Center. Obstacles to Effective Management of Conflicts Between National Parks and Surrounding Human Communities in Developing Countries. Environ. Conserv. 1988, 15, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Guidelines for Protected Area Management Categories; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1996.

- Yinkerton, E. Toward specificity in complexity: Understanding co-management from a social science perspective. In The Social Economy of Co-Management; Natcher, D.C., Ed.; University of Alberta Press: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2003; pp. 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F. Devolution of environment and resources governance: Trends and future. Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, M.; He, Q. An Evolving Model for National Parks: From Island and Networks to Landscapes and Socio-ecological Approaches. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 35, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meijil, T. Making Our Place: Exploring Land-Use Tensions in Aotearoa New Zealand: [Book Review]. 2012. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43590510 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Shafer, C.L. US national park buffer zones: Historical, scientific, social, and legal aspects. Environ. Manag. 1999, 23, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Fang, S.; Ji, X. A Review on the Research of Natural Protected National Park. Urban Plan. Int. 2017, 32, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wright, G.M.; Thompson, B.H.; Dixon, J.S. Fauna of the National Parks of the United States: A Preliminary Survey of Faunal Relations in National Parks; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1933; Volume 1.

- MacKinnon, J.; MacKinnon, K.; Child, G.; Thorsell, J. Managing Protected Areas in the Tropics; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1986.

- Du, W.; Penabaz-Wiley, S.M.; Njeru, A.M.; Kinoshita, I. Models and approaches for integrating protected areas with their surroundings: A review of the literature. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8151–8177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wu, C.Z. An Innovative Research on Practical Problems and Zoning Modes of Nature Reserve. J. Landsc. Archit. 2014, 21, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhumuza, M.; Balkwill, K. Factors affecting the success of conserving biodiversity in national parks: A review of case studies from Africa. Int. J. Biodivers. 2013, 2013, 798101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Park Service. Administrative Policies for Natural Areas of the National Park System. 1968. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/admin_policies/policy2-appb.htm (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Watson, M.S.; Jackson, A.M.; Lloyd-Smith, G.; Hepburn, C.D. Comparing the marine protected area network planning process in British Columbia, Canada and New Zealand–Planning for cooperative partnerships with indigenous communities. Mar. Policy 2021, 125, 104386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.R.; Venter, O.; Fuller, R.A.; Allan, J.R.; Maxwell, S.L.; Negret, P.J.; Watson, J.E.M. One-third of global protected land is under intense human pressure. Science 2018, 360, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, C.L. National park and reserve planning to protect biological diversity: Some basic elements. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1999, 44, 123–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Congress. Wilderness Act of 1964. Public Law 88-577, 16 U.S.C. 1131-1136. 1964. Available online: https://www.umt.edu/media/wilderness/NWPS/documents/publiclaws/The_Wilderness_Act.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- European Council. Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora (The Habitats Directive). Off. J. Eur. Communities 1992, L 206, 7–50. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).