Abstract

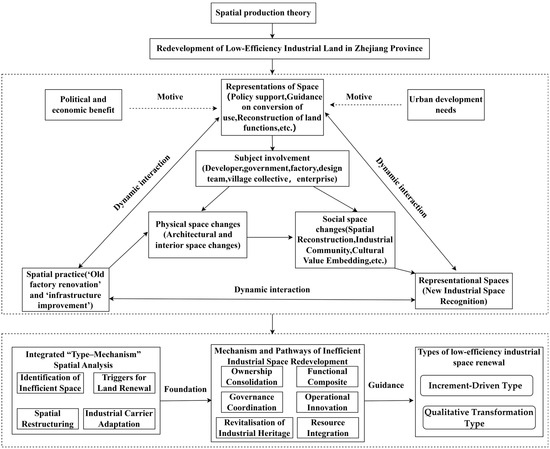

As Chinese cities move toward stock-based development, the redevelopment of inefficient industrial land has become essential for urban spatial restructuring and sustainable transformation. Building on Lefebvre’s triadic theory of spatial production, this study establishes a comprehensive analytical framework consisting of spatial practice, representations of space, and representational spaces, aiming to elucidate the mechanisms underlying spatial reconfiguration. Through a multi-case inductive approach, twelve representative cases from Zhejiang Province are systematically analyzed to reveal the fundamental logic driving spatial reconstruction within the context of inefficient land redevelopment. The results reveal the following: (1) In the process of inefficient land redevelopment, spatial practice involves land reuse and functional integration, representations of space reflect institutional planning, and representational spaces shape meaning through cultural identity and user experience. These dimensions interact dynamically to drive the transformation of both the form and meaning of inefficient land. (2) The redevelopment of inefficient land in Zhejiang can be classified into two primary models: increment-driven and qualitative transformation, which are further divided into seven subtypes. The increment-driven model includes enterprise-initiated renewal, integrated upgrading, platform empowerment, and comprehensive remediation; the qualitative transformation model comprises mine remediation, cultural empowerment, and use conversion. (3) Significant differences exist between these models: the increment-driven model emphasizes land expansion and floor area ratio improvement, while the qualitative transformation model enhances land value through mine restoration, cultural embedding, and functional transformation. This study extends the application of spatial production theory within the Chinese context and offers theoretical support and policy insights for the planning and governance of inefficient industrial land redevelopment.

1. Introduction

As a critical foundation for industrial development, industrial land serves as the cornerstone for constructing modern industrial systems and plays a pivotal role in supporting high-quality urban growth. In the context of increasingly scarce land resources and intensifying competition over urban space, the redevelopment of inefficient, idle, and obsolete industrial land has become an essential strategy for enhancing overall urban competitiveness [1,2]. This transformation is particularly pressing in China, where national development strategies are transitioning from expansion through new land supply toward optimizing existing land stocks and promoting sustainable, high-quality development. Consequently, the systematic redevelopment of inefficient industrial spaces has emerged as a key priority for urban governance and spatial restructuring [3]. In response to this challenge, the Ministry of Natural Resources issued the “Notice on Launching Pilot Work for the Redevelopment of Inefficient Land” in 2023, proposing to enhance land output efficiency and optimize spatial configurations through resource-saving approaches. The policy aims to establish a replicable and scalable framework for inefficient land redevelopment, thereby providing institutional support for intensive, connotative, and environmentally sustainable urban and rural development. In this study, we adopt a government perspective and define inefficient industrial land as industrial parcels that satisfy administrative criteria employed by Chinese local governments. This operationalization follows the Zhejiang Provincial Government’s Opinion on the Comprehensive Promotion of Urban Redevelopment of Inefficient Land (Zhezhengfa [2014] No. 20). Under the rubric of “old plants and mines,” the policy treats as inefficient parcels that do not conform to statutory plans and are designated to shift from secondary to tertiary uses; parcels that fail safety or environmental compliance; parcels associated with industries listed for prohibition or phase-out at the national or provincial level; parcels whose development intensity and input–output performance fall significantly below land-use control standards; parcels occupied by technologically backward sectors or distressed firms slated for exit; and closed or exhausted mining lands. Furthermore, old industrial areas, as significant remnants of industrial heritage, embody unique historical memory and urban identity. Their regeneration involves not only the adaptive reuse of physical space but also the preservation of cultural heritage and the redefinition of local identity [4].

In recent years, both domestic and international scholars have conducted multidimensional theoretical and empirical studies on the redevelopment of inefficient industrial land, primarily focusing on four key perspectives: property rights, institutional change, benefit distribution, and effect analysis. From the perspective of property rights, Chinese scholars argue that issues such as unclear ownership and fragmented tenure significantly increase negotiation and transaction costs, thereby hindering project implementation and equitable benefit sharing [5,6]. Similarly, in regions such as the UK’s coastal areas and Luxembourg, dispersed ownership and conflicting stakeholder interests have reduced redevelopment efficiency [7,8], underscoring the need for property rights clarification, optimized allocation, and institutional innovation. Empirical studies also suggest that ambiguous property rights may offer flexibility for multi-party collaboration but can simultaneously introduce governance risks, including planning inconsistencies and the erosion of public interest [9]. From the institutional change perspective, research highlights that evolving land policies and planning frameworks serve as major catalysts for initiating inefficient land redevelopment. Ongoing reforms in China’s urban land management system have effectively facilitated the revitalization of existing land stock and the renewal of industrial landscapes [10,11]. In the UK, the establishment of brownfield development targets and supportive policy incentives has promoted urban land reuse [12,13], while, in the United States, EPA-led legislative measures and financial support programs have integrated environmental remediation with economic revitalization, enabling large-scale brownfield redevelopment initiatives [14]. From the benefit distribution perspective, the equitable allocation of land value-added benefits among diverse stakeholders is crucial for the successful implementation of redevelopment policies. Chinese scholars propose that flexible and adaptive benefit-sharing mechanisms help balance cooperation efficiency and transaction costs, thereby fostering multi-stakeholder collaboration [15]. Similarly, in countries like the UK, the distribution of benefits among developers, local governments, and communities directly influences project outcomes and social acceptance [16]. In certain European regions, dynamic risk and return allocation through PPP models has become a widely adopted mechanism for improving governance in industrial land redevelopment [8]. Finally, effect analysis focuses on the spatial restructuring, economic spillovers, and improvements in social well-being resulting from redevelopment efforts. Studies in China indicate that the redevelopment of inefficient industrial land contributes to optimizing urban spatial structures, enhancing ecological environments, and driving industrial upgrading [17,18]. Case studies from Canada, the UK, and Europe demonstrate that brownfield redevelopment improves land use efficiency, residents’ quality of life, and urban aesthetics, while also stimulating employment and preserving green spaces [19,20,21].

In summary, contemporary scholarly research on the redevelopment of inefficient industrial land has evolved toward a multi-dimensional and integrative analytical framework. From the property rights perspective, research has identified the dual effects of ambiguous property structures on redevelopment processes. The institutional change perspective underscores the pivotal role of evolving land policies and planning systems in steering spatial transformation. Meanwhile, the benefit distribution perspective emphasizes the importance of coordination mechanisms that facilitate equitable sharing of land value-added benefits among diverse stakeholders. Lastly, the effect analysis perspective provides empirical evidence regarding the economic, spatial, and social impacts of redevelopment initiatives. Collectively, these studies have laid a solid theoretical and practical foundation for understanding the pathways and governance logic underlying the transformation of inefficient industrial spaces. However, existing research predominantly centers on policy, institutional, and economic dimensions, with relatively limited attention given to the social mechanisms, actor interactions, and identity construction embedded within the restructuring of spatial configurations during redevelopment. The theory of spatial production, as a comprehensive analytical framework examining the dynamic interplay between society and space, offers valuable insights into the roles of institutional power and agency in spatial reproduction processes. Therefore, this study aims to develop an analytical framework for the redevelopment of inefficient industrial land grounded in Lefebvre’s “triadic structure of space” theory. It systematically investigates the interrelationships and feedback dynamics among spatial practice, representations of space, and representational spaces across different types of redevelopment practices, thereby deepening the understanding of the underlying mechanisms of spatial redevelopment.

Focusing on Zhejiang Province as a case study region, this paper explores the redevelopment pathways and internal operational mechanisms associated with various forms of inefficient industrial land. The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 establishes the theoretical analytical framework; Section 3 outlines the research design and rationale for case selection; Section 4 examines the triadic structure mechanisms of each case through the dual lenses of “increment-driven” and “qualitative transformation” redevelopment pathways; Section 5 presents a broader discussion on the redevelopment of inefficient land in Zhejiang Province; and Section 6 concludes with key findings and implications for future research.

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Analysis

French scholar Henri Lefebvre, in The Production of Space, argued that space is not a passive or naturally given container, but rather a socially constructed product shaped by the interplay of social relations, power structures, and economic interests. The organization, distribution, and function of space serve as critical reflections of the conflicts and cooperation among various social classes and actors. Consequently, the theory of spatial production provides a robust and explanatory analytical framework for understanding the dynamic transformation of industrial land and urban space. Lefebvre conceptualizes the production of space through three interrelated dimensions: (1) spatial practice, which refers to the concrete use and transformation of space through everyday social activities; (2) representations of space, denoting the formal planning, design, and regulatory control of space by “experts” such as governments, planning authorities, and developers; and (3) representational spaces, which captures the lived experiences, symbolic meanings, and emotional attachments of ordinary citizens and users [22]. We frame industrial land redevelopment through Lefebvre’s insight that space is socially produced and that spatial form crystallizes relationships among actors, power, and capital. The triad distinguishes spatial practices, representations of space, and representational spaces, which together allow us to ask who produces space, through which instruments and practices, and with what implications for meaning and identity. Set against alternative frameworks, urban political economy explains how capital circulation, land rent and entrepreneurial governance drive urban restructuring [23,24]; the growth-machine perspective highlights land-based coalitions that pursue place-based growth [25]; urban-regime theory focuses on governing coalitions and their capacity to coordinate resources [26]; and relational approaches stress the co-constitution of spatial relations and the unboundedness of regions [27]. These lenses are complementary, and we privilege Lefebvre’s triad because it provides a unified language to connect instruments and plans as representations of space, implementation and land-use change as spatial practices, and identity and meaning as representational spaces; operationalized in this study, the triad allows us to trace feedback loops in which policy tools and planning norms structure investment and spatial reconfiguration, observed practices generate performance signals that prompt rule and sequencing adjustments, and lived meanings reshape stakeholder preferences.

To delimit our argument and situate it in China’s institutional setting, we articulate the limits of Lefebvre’s triad and our context-specific adaptation. While the triad links plans and instruments to practices and lived meanings, it is abstract and normatively open, risking indeterminate subjects and outcomes if not carefully operationalized; overemphasis on representations of space can also eclipse practice and lived space [28,29,30]. In China’s strong-government setting, planning centrality and market instruments under state entrepreneurialism concentrate control of land tools in the state and its SOE platforms, compressing the distance between representations and practices and translating plans into implementation through land finance, land leasing, and development corporations [31,32,33]. Socio-spatial meanings of such projects are frequently mediated by official narratives, place branding, and curated heritage programming [33]. To enhance tractability for industrial land redevelopment, we therefore map each dimension to observable indicators used in our cases: representations as statutory plans, redevelopment rules, and regulatory yardsticks; practices as floor area ratio change, phasing, standardized multistory industrial supply, and leasing regimes; representational spaces as heritage designation and museum or park programming. We interpret policy–practice–meaning feedback within these constraints.

2.2. Theoretical Development and Empirical Insights from a Global Perspective

In recent years, spatial production theory, with its multidimensional perspective and critical capacity, has continued to shape the development of urban renewal and governance abroad, moving from abstract interpretation to multi-layered analyses of real-world issues. The theory has been widely applied in various domains, including urban governance, metropolitan renewal, public housing redevelopment, heritage preservation, and the politics of racialized space [34,35,36,37,38]. For example, studies have emphasized the dynamic interplay among perceived, conceived, and lived spaces in understanding spatial change and social transformation [34]. Research on public housing redevelopment has analyzed the tensions between state-led spatial commodification and grassroots practices, revealing how spatial production can reinforce urban stratification and inequality [35]. Infill policies and place-making initiatives have also been examined through the lens of spatial triads, exposing the complex relationships among policymakers, residents, and everyday spatial practices [39,40]. Overall, the application of spatial production theory in international contexts has expanded from macro-level governance and legal frameworks to micro-level daily life, social identity, and cultural production. This expansion has deepened our understanding of the dynamic relations among space, power, identity, and capital, and has provided a robust theoretical foundation and practical guidance for advancing spatial justice, social participation, and the revaluation of historical memory in urban governance.

2.3. Contextualized Application and Theoretical Advancement of Spatial Production Theory in China

In recent years, the theory of spatial production has been extensively and deeply integrated into the governance of urban and rural spaces in China, gradually contributing to the development of localized theoretical frameworks and practical models. In the domain of rural governance, research has centered on the coupling relationship between cultivated land and homestead transformation, emphasizing their multidimensional interactions and significance for the evolution of rural spatial structures and revitalization strategies [41]. Furthermore, the reconstruction of “production–living–ecological” spaces has drawn scholarly attention, with studies uncovering the complex dynamics of rural transformation, revitalization, and ecological civilization through the lenses of power relations, capital flows, and social forces [42]. Scholars have also identified that resilient rural spatial restructuring and collaborative governance require attention to spatial differentiation, functional optimization, organic integration, and adaptive capacity [43]. Meanwhile, comprehensive regional land consolidation is recognized as necessitating a balanced approach that aligns national strategies, industrial development, and livelihood improvement, aiming to achieve multi-objective synergy and optimized urban–rural spatial configurations [44].

In the realm of urban spatial governance, the integration of spatial production theory with collaborative governance has led to the conceptualization of a “collaborative spatial production” mechanism. This framework highlights the importance of co-governance and benefit integration among government, enterprises, and collectives, as well as multi-actor collaboration and shared value creation under governmental leadership [45]. Studies on urban villages have uncovered the internal mechanisms linking spatial production, social structure transformation, and the reconfiguration of spatial boundaries [46]. In the domain of urban stock space reproduction and effective governance, scholars have developed a collaborative governance framework grounded in the theory of spatial production. They argue that the interaction among governmental institutions, market forces, social actors, and cultural contexts, as guided by policy frameworks, jointly facilitates the functional transformation and high-quality governance of urban stock spaces [47]. Fiscal systems and multi-stakeholder collaboration are also acknowledged as critical drivers of urban spatial reproduction and value enhancement, prompting recommendations for policies aimed at achieving fiscal sustainability [48].

In the context of old urban districts, industrial heritage, and cultural space conservation and renewal, spatial production theory has offered novel analytical perspectives on the roles of land policy, capital coordination, and planning operations in the spatial reproduction of industrial heritage. These insights have informed the development of multidimensional renewal strategies encompassing spatial practice, spatial representation, and spatial governance [49]. Research on the evolution of old industrial areas and intangible cultural heritage tourism zones underscores the combined influence of power dynamics, capital interventions, and social mechanisms, with increasing emphasis placed on spatial justice and public participation as essential future directions [4,50]. The integration of interests, capital, and power has further revealed multi-stage mechanisms of spatial regeneration driven by policy, capital, and consumption. Improvements in benefit evaluation, capital coordination, and public participation are considered vital for achieving sustainable spatial regeneration [51]. Case studies such as the Xi’an “Old Market” project and Beijing Shougang Industrial Park illustrate how spatial functions are redistributed and social relations reorganized under conditions of capital dominance, physical redevelopment, and multi-actor engagement. These examples reaffirm that space is not merely a physical container but also a site for the re-articulation of power relations and collective memory [52,53].

Overall, spatial production theory in China has undergone multidimensional expansion, encompassing transitions from macro-level policy frameworks to micro-scale contextual analyses, from urban to rural settings, and from theoretical adaptation to indigenous innovation. This evolutionary process has established a robust theoretical foundation and methodological framework for advancing innovative governance of urban and rural spaces in China.

2.4. Theoretical Framework

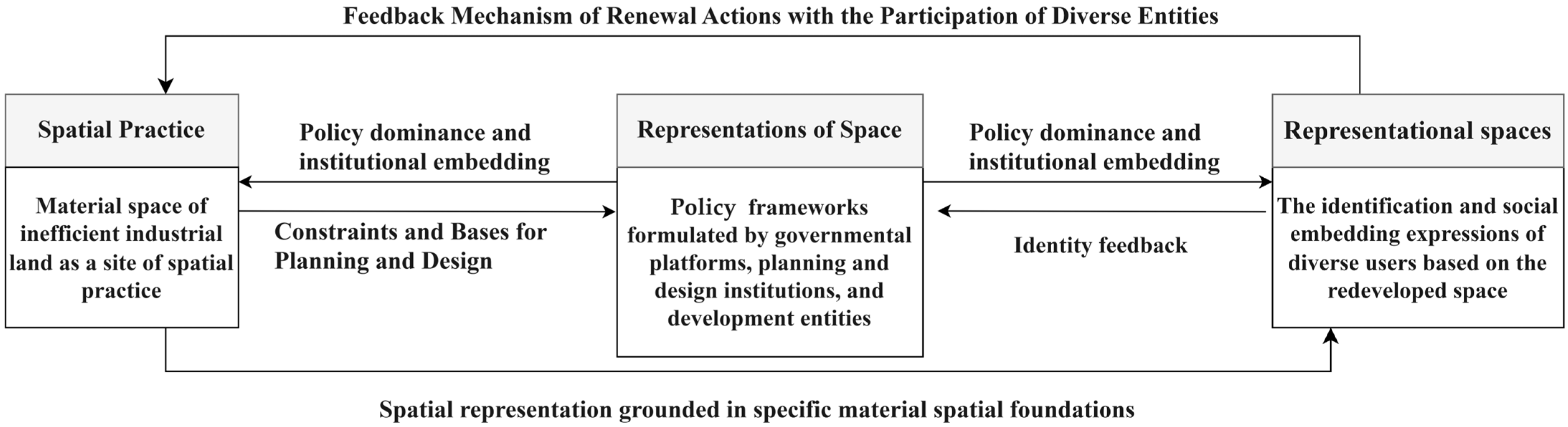

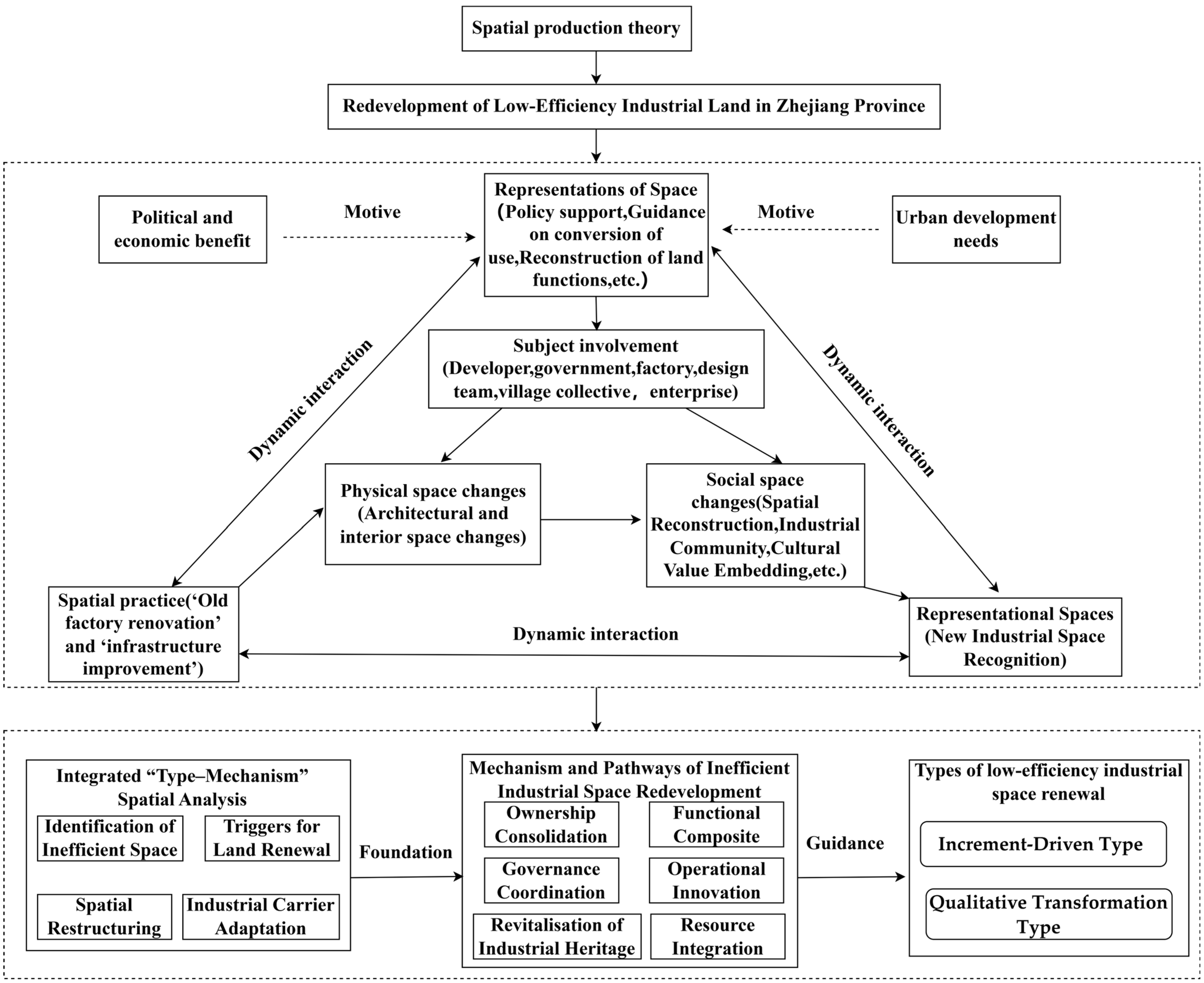

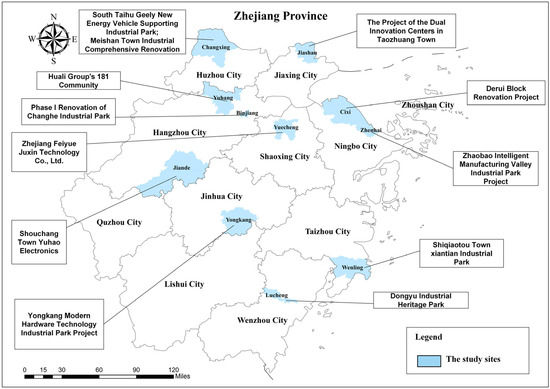

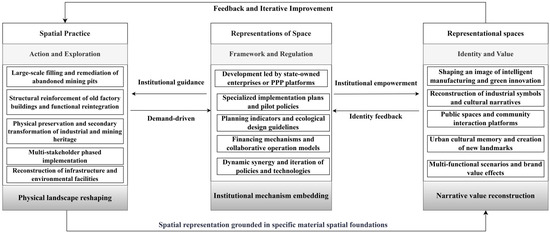

Building on prior scholarship, this study situates Lefebvre’s triadic theory of spatial production within the context of inefficient industrial land redevelopment in China, thereby constructing a theoretical framework tailored to this empirical setting. Figure 1 illustrates the framework of the theory of space production. Within this framework, the dimension of spatial practice refers to the actual utilization and transformation of inefficient industrial sites, encompassing processes such as demolition, reconstruction, and functional conversion. Representations of space are embodied in the actions of governmental bodies and their technical agents, including planning and design institutions, which enact spatial configurations and exercise development control in line with policy imperatives. The dimension of representational spaces centers on users’ affective identification, cultural expression, and processes of social reintegration in relation to the renewed space, thereby embodying the social and symbolic meanings inherent in spatial production. These three spatial dimensions are not static or parallel, but rather form a dynamic coupling mechanism throughout the redevelopment process of inefficient industrial land. On one hand, representations of space guide the implementation of spatial practice through planning, indicators, and policy frameworks, while also shaping representational spaces. At the same time, the performance and outcomes of spatial practice feed back into institutional optimization and mechanism adjustment. Moreover, the cognitive feedback of space users within representational spaces continuously stimulates the revision and reconstruction of spatial representations. In summary, the spatial triad model advanced in this paper emphasizes the co-construction of spatial institutions and social practice, foregrounding the socially produced and culturally embedded nature of urban space. This analytical framework underpins the subsequent typological and mechanistic analysis of empirical cases and offers a structured lens for understanding urban spatial governance in the Chinese context.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for inefficient industrial land redevelopment based on the theory of spatial production.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

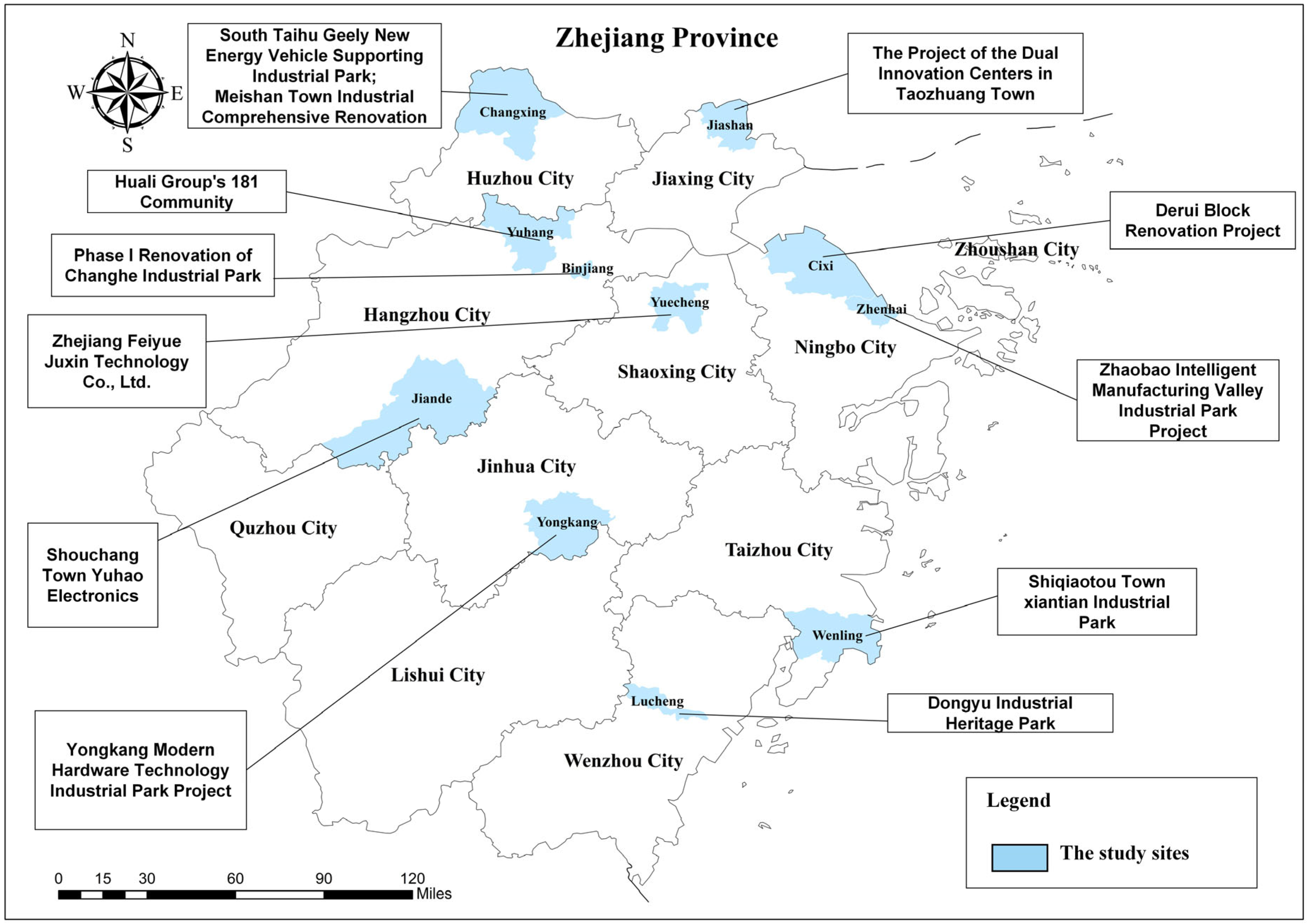

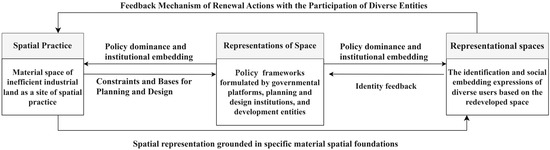

Zhejiang Province is located on the southeast coast of China, forming the southern wing of the Yangtze River Delta. It is characterized by a distinctive topography known as “seven parts mountains, one part water, and two parts farmland,” and is regarded as one of the nation’s exemplary provinces for integrated land–sea development. According to the Zhejiang Provincial Territorial Spatial Plan (2021–2035), the province had a permanent population of 64.57 million in 2020, with an urbanization rate of 72.2%. All prefecture-level cities experienced net population growth compared to the sixth national census. The province’s GDP reached CNY 6.47 trillion, and its per capita GDP exceeded CNY 100,000. Despite accounting for only 1.1% of China’s land area, Zhejiang supports 4.6% of the national population and contributes 6.4% of the national GDP, making it one of the most densely populated and economically dynamic regions in the country. Amid rapid urbanization and industrialization, Zhejiang faces structural challenges such as intense competition for urban and rural land, increasing scarcity of land reserves, and pronounced spatial conflicts between urban and rural sectors. At the national level, Zhejiang has long been at the forefront of land spatial optimization and the redevelopment of inefficient land. The province stands out as a benchmark for revitalizing existing land stock and promoting high-quality development in China, owing to its highly intensive and efficient land use, policy innovation capacity, and pioneering institutional environment. This study focuses on typical regions characterized by the redevelopment of inefficient industrial land in Zhejiang Province, selecting eight representative pilot cities: Hangzhou, Ningbo, Shaoxing, Jinhua, Jiaxing, Wenzhou, Huzhou, and Taizhou. The locations of cases are shown in Figure 2. These cities are distributed across various geographical zones within the province, encompassing the provincial capital, sub-provincial cities, and economically developed prefecture-level cities, thereby reflecting the diversity and representativeness of Zhejiang’s approaches to spatial governance and industrial transformation. As a leading region and a typical case of national spatial governance and industrial upgrading, Zhejiang’s practical experience not only serves as a model for its own sustainable development but also provides valuable insights for similar regions across the country.

Figure 2.

The locations of the study sites.

3.2. Research Background

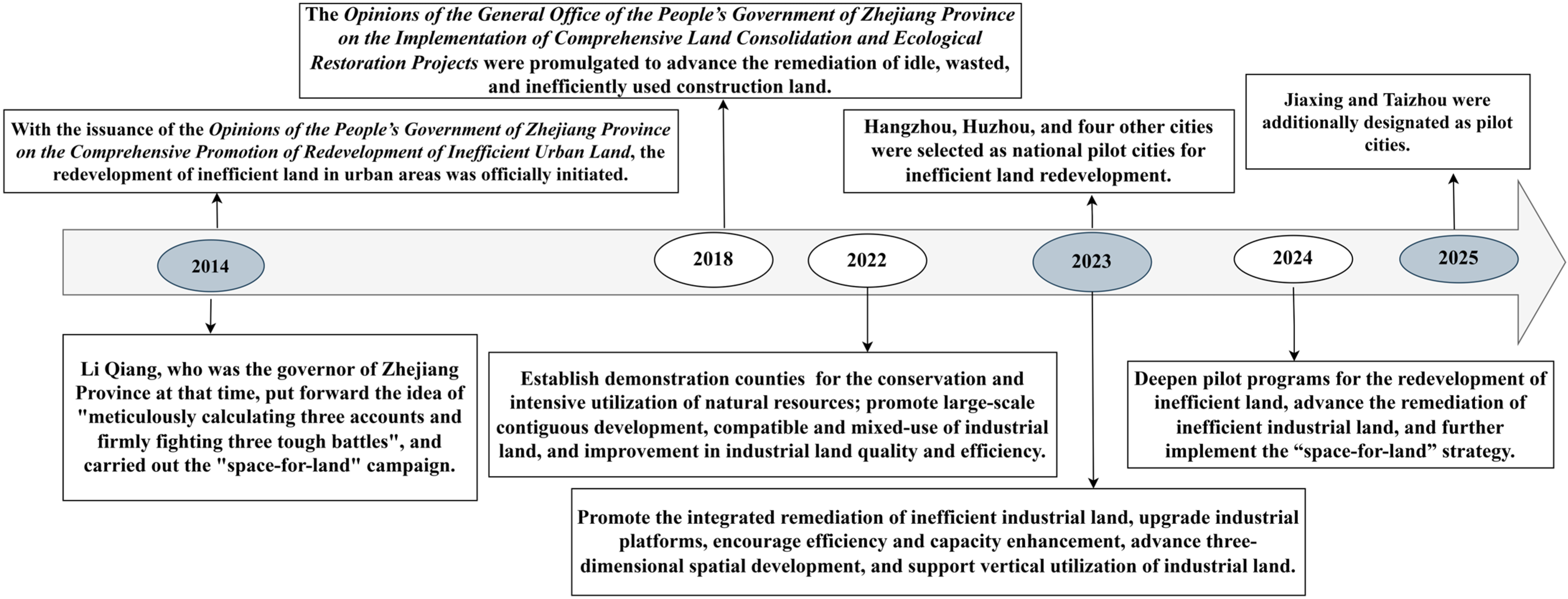

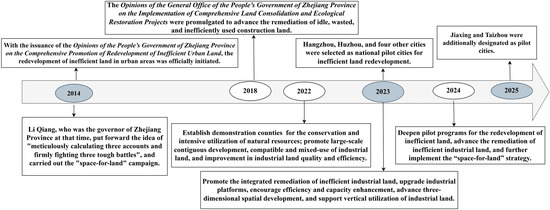

With the accelerated expansion of urban and industrial areas, the potential for developing new land reserves in Zhejiang Province has become increasingly limited. In response, Zhejiang issued the Opinions on Fully Advancing the Redevelopment of Inefficient Urban Land in 2014, launching a province-wide campaign to promote the comprehensive redevelopment of inefficient urban land. At that time, Governor Li Qiang emphasized the importance of “calculating three critical accounts and fighting three tough battles,” advocating for the “space-for-land” initiative to accelerate the process and marking the formal beginning of large-scale redevelopment efforts across the province. In 2018, Zhejiang introduced the Opinions on Implementing Comprehensive Land Consolidation and Ecological Restoration Projects Province-wide, which articulated requirements to control the total amount of land used, optimize new land supply, revitalize existing stock, release land flow, and achieve a net reduction in land consumption, all aimed at promoting the economic and intensive use of land resources. By 2022, the province further advanced this agenda by establishing a series of demonstration counties (and cities) for the economical and intensive use of natural resources. These initiatives promoted land conservation, reduction in new land use, optimization of land use structure and layout, and a stronger focus on revitalizing existing land resources and enhancing land use intensity and efficiency. In the same year, Zhejiang issued the Opinions on Further Promoting the Revitalization and Utilization of Existing Land Guided by Digital Reform, which encouraged the concentrated and contiguous redevelopment of land and aimed to improve the quality and efficiency of industrial land use. In 2023, the Ministry of Natural Resources selected 44 cities (districts and counties) nationwide for pilot programs in inefficient land redevelopment, with six cities in Zhejiang, including Hangzhou, being selected. That same year, the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Natural Resources issued the Opinions on Further Enhancing the Economical and Intensive Use of Land, deepening efforts in industrial land consolidation. In 2025, the Notice on Expanding and Deepening Pilot Projects for the Redevelopment of Inefficient Land was released, expanding the pilot program to include Jiaxing and Taizhou as additional sites for inefficient land redevelopment. As shown in Figure 3, over the past decade, Zhejiang has consistently pursued institutional and policy innovation in this domain, accumulating extensive experience in areas such as capacity enhancement and vertical industrial development. These policy experiments and practical advancements have provided a rich set of cases and empirical material for the present research.

Figure 3.

Evolution of inefficient industrial land redevelopment in Zhejiang Province.

3.3. Case Selection

We selected twelve representative cases from Zhejiang (Hangzhou, Ningbo, Jinhua, Wenzhou, Huzhou, Shaoxing, Jiaxing, Taizhou) using the following consolidated criteria: (1) diversity of redevelopment models and stakeholders, involving SOE platforms, enterprises, and government-led actors; (2) policy relevance and typicality, giving priority to cases included in the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Natural Resources’ pilot/typical compilations and the ministerial case library, with most recognized as exemplary at national, provincial, or municipal levels; (3) documentation richness and verifiability, with official materials suitable for cross validation and triangulation of provincial and municipal records; (4) implementation stage and observability, namely projects initiated or completed in the past decade with completed or accepted components or officially reported outcomes; and (5) intra-provincial diversity, ensuring coverage across cities and counties to capture governance variation. The case summaries are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of cases.

Overall, these cases capture the diversity of renewal mechanisms, development actors, and institutional arrangements, highlighting the richness and heterogeneity of Zhejiang’s experience in redeveloping inefficient industrial land.

3.4. Data Sources

This study uses official data. First, during a commissioned project with the Zhejiang Department of Natural Resources, we accessed the provincial pilot case compendium and the national case library curated by the Ministry of Natural Resources, together with county-level submissions that are routinely reported and consolidated by the province. Second, to enrich case attributes, we systematically consulted municipal government portals across the pilot areas, covering multiple prefecture-level cities, such as Hangzhou, Ningbo, and others, and extracted case columns and project notices that document case background, measures, outcomes, and policy learning. Third, we held working meetings with provincial and pilot area staff to confirm facts related to case scope, implementation paths, and policy instruments; these communications served for verification. For each case, key facts were cross-checked across at least two independent official sources or confirmed once through a formal communication to ensure consistency between provincial and municipal records and to reduce single-source bias. The data sources are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of case data sources.

3.5. Research Methods

An inductive approach was employed to analyze the empirical materials. Interpretation follows an inductive strategy grounded in official documents. For each case, the full set of records was read and four attributes were coded, namely, whether the statutory land use changes, the spatial scope and ownership complexity, the organisational modality, and the dominant intervention content. Through constant comparison across cases, these attributes yielded two top-level groups and several subtypes. Cases with a recorded change in statutory land use are classified as transformational upgrading and are further differentiated by content into land-use conversion, culture and tourism-oriented renewal, and mine-land remediation. Cases without land-use change are classified as incremental driven and are differentiated into enterprise-initiated renewal, integration and upgrading, platform-enabled renewal, and comprehensive remediation, depending on whether the work concerns a single enterprise with demolition and reconstruction to raise floor-area ratio, multi-owner contiguous consolidation, a state-owned or public-private platform that bundles acquisition and clearance, or township-level coordination with village–enterprise co-building and ecological improvement.

Two brief examples illustrate how the rules are applied. Zhejiang Feiyue Juxin Technology Co., Ltd. involves one enterprise and large-scale demolition and reconstruction to enhance the floor-area ratio while the statutory land use remains industrial, so it is coded as enterprise-initiated renewal within the incremental-driven group. By contrast, the Yuhao Electric project in Shouchang Town converts industrial land to commercial and cultural tourism use, which changes the statutory land use, so it is coded as transformational upgrading under the land-use conversion subtype. Other cases in the dataset are assigned using the same rules.

4. Results

4.1. Logic and Criteria for Categorizing Pathway Types

We classify redevelopment into two analytically distinct pathways. The increment-driven pathway is supported by research on efficiency-oriented upgrading and consolidation of industrial sites, where projects intensify existing industrial functions without changing the primary land-use category [54,55,56,57]. The qualitative transformation pathway is grounded in studies of repurposing and conversion, including shifts to mixed or non-industrial uses and identity reconfiguration through ecological remediation, heritage reuse, and new programming [58,59,60]. In the increment-driven pathway, the primary objective is to raise land use efficiency and industrial performance without changing the primary land use category. A case is classified as increment driven when at least two of the following conditions are satisfied: (1) no formal approval for land use conversion is recorded; (2) the dominant interventions focus on industrial intensification and plot consolidation, including standardized multistory plants, shared logistics, and service upgrades; (3) admissions catalogues and performance benchmarks remain oriented to manufacturing; (4) pre and post indicators show increases in floor-area proxies, output or tax per land area, and employment density. By contrast, the qualitative transformation pathway centers on land use conversion or functional reconfiguration accompanied by a redefined place identity. A case is classified as qualitative transformation when at least two of the following conditions are satisfied: (1) the dominant function shifts to non-industrial or mixed use; (2) substantial ecological remediation, heritage reuse, or major landscape works are implemented; (3) programmed uses in culture, services, tourism, or advanced producer services are introduced; (4) evidence appears of new user groups, visitor flows, and functional diversity consistent with the new positioning. Because phased projects may exhibit hybrid features, we apply a dominant-mechanism rule to maintain analytical clarity while acknowledging real-world overlap. The classification features of the cases are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Table of classification characteristics of cases.

4.2. Comparative Mechanisms by Pathway for Industrial Land Redevelopment

Table 4 sets out a comparative framework for industrial land redevelopment pathways. It specifies, for each pathway, the primary objective, typical triggers, land use status at completion, dominant interventions, and the associated economic, policy, and social logics. It also identifies the principal stakeholders and their roles, the expected observable outputs with corresponding indicators, and challenges.

Table 4.

Comparative mechanisms by pathway for industrial land redevelopment.

4.3. Increment-Driven Pathways and Practical Forms

4.3.1. Enterprise-Initiated Renewal

This category is driven by the autonomous initiatives of enterprises or landowners in response to market demand. It adopts an incremental and flexible approach to the intensive spatial and functional renewal of underutilized industrial land. The government provides institutional innovation and streamlined procedures as supportive measures, resulting in an effective coupling of enterprise leadership, market forces, and policy support. This type of redevelopment typically involves large-scale demolition and reconstruction, with comprehensive re-planning and high-standard development of land parcels. Measures such as “industrial buildings above ground” (gong ye shang lou) are employed to significantly increase the total building volume and improve land use efficiency, thereby achieving substantial spatial expansion and value enhancement.

- (1)

- The Renewal Project of Zhejiang Feiyue Juxin Technology Co., Ltd.

The organic renewal project of Zhejiang Feiyue Juxin Technology Co., Ltd. illustrates the hierarchical interplay among spatial practice, representations of space, and spaces of representation. At the level of spatial practice, the company independently redeveloped its outdated 9.73-hectare textile factory to meet the demands of the pan-semiconductor industry, significantly increasing the floor area ratio from 0.535 to 2.12 and upgrading both spatial functions and industrial structure, as shown in Table 5. At the level of representations of space, government policies such as the Implementation Rules for Autonomous Organic Renewal of Stock Industrial Land provided institutional guidance on renewal models, procedures, and standards, thereby supporting a regulated, enterprise-led transformation. At the level of representational spaces, the renewal process fostered a new spatial identity for both the enterprise and the district, promoting the social and cultural re-embedding of the area. The redevelopment of Feiyue Juxin Technology’s industrial site exemplifies a robust feedback mechanism linking public policy, firm-level needs, and land-use optimization. Measurable performance signals from the project, including intensity gains and fiscal yields, feed back into practice and prompt the refinement and wider replication of the admission catalogue, renewal procedures, and operating standards, thereby improving factor allocation efficiency and regulatory enforceability. Ultimately, this mechanism strengthens the reconfiguration of property rights and land use, the standardization of safety and compliance, the upgrading of industrial structures and business formats, and the integration of industry, city, and people, steadily transforming underutilized stock space into a growth pole for new-quality productive forces. This case underscores the integrated roles of institution, practice, and identity, offering both a practical model and a theoretical reference for efficient land redevelopment and industrial spatial transformation.

Table 5.

Pre- and post-redevelopment indicators for the Zhejiang Feiyue Juxin Technology Co., Ltd.

- (2)

- Redevelopment of Huali Group’s 181 Community

Guided by Lefebvre’s theory of spatial production, the redevelopment of Huali Group’s 181 Community in Yuhang District, Hangzhou, illustrates the interplay among spatial practice, representations of space, and representational spaces. At the level of spatial practice, Huali Group independently redeveloped its outdated 33.63 hectare industrial site, increasing the floor area ratio from 0.67 to 2.2 and restructuring both spatial layout and function to meet the demands of advanced manufacturing and R&D, as shown in Table 6. At the level of representations of space, the government provided institutional frameworks and planning guidance through regulatory adjustments, streamlined procedures, and targeted policies such as those promoting multi-story industrial buildings. Based on these foundations, the enterprise established integrated functional zones and ensured compliance with industrial standards. At the level of representational spaces, the park’s transformation and service upgrades fostered a new spatial identity and facilitated its evolution into an integrated industry–city platform. The redevelopment of the project reflects a strong feedback mechanism between government policies, enterprise needs, and land use optimization. First, planning and rules directly structure construction sequencing, plant types, and functional programming. Second, phased implementation and multistory industrial plants feed back to streamline approvals and refine indicators, entrenching the unified investment-promotion and leasing plus subdivided-transfer package. Third, ecology-oriented user experiences heighten park attractiveness and stickiness, driving firm clustering and functional upgrading, which in turn validate and stabilize the established zoning and policy mix. Overall, the project operates a planning–implementation–experience–replanning loop in which higher intensity, industrial optimization, and environmental improvements reinforce one another. This case demonstrates how institutional regulation and spatial practice mutually reinforce each other, offering a systematic model for the efficient redevelopment of industrial land.

Table 6.

Pre- and post-redevelopment indicators for the Huali Group 181 Community redevelopment.

- (3)

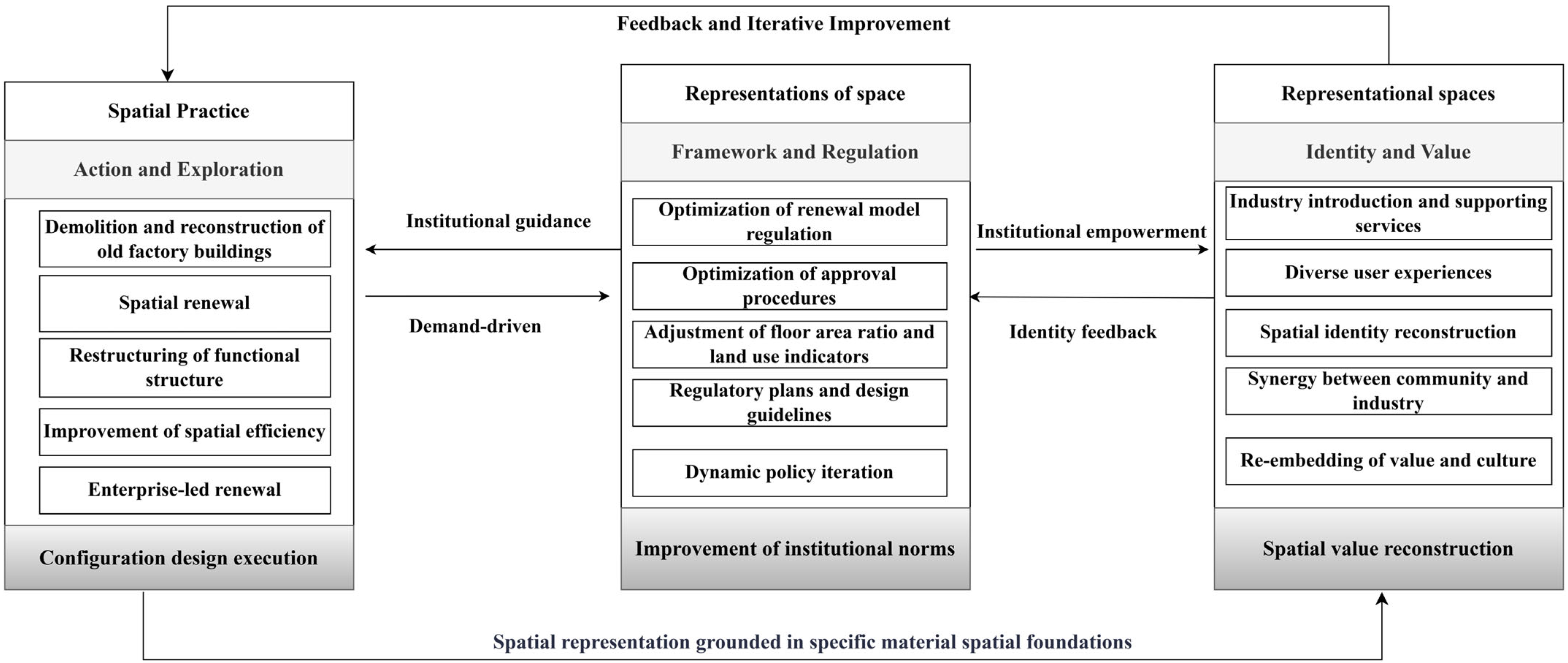

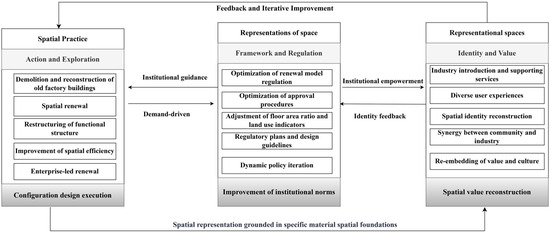

- Mechanisms of Enterprise-initiated Renewal

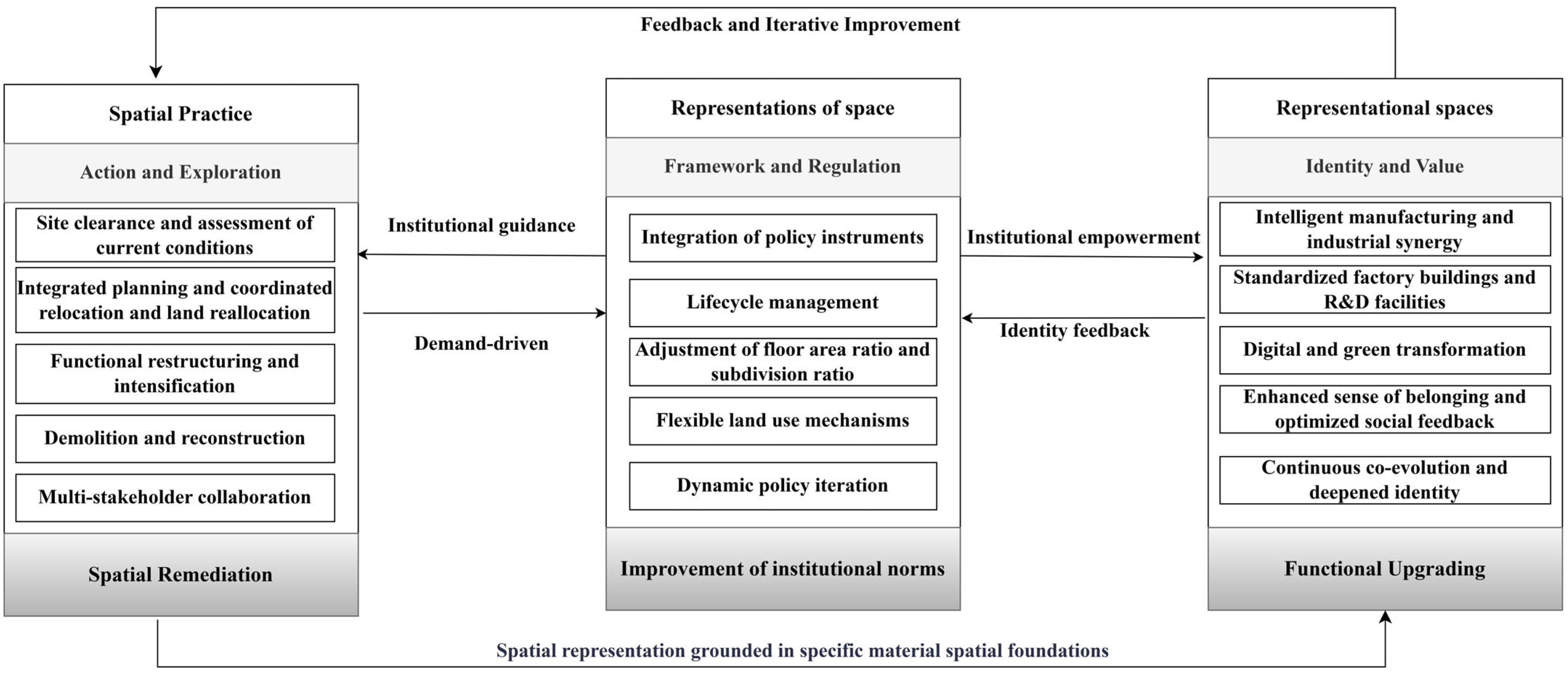

As shown in Figure 4, the mechanism of enterprise-led autonomous renewal in the redevelopment of inefficient industrial land is characterized by the synergistic interplay of spatial practice, representations of space, and representational spaces. At the level of spatial practice, enterprises actively undertake the demolition and reconstruction of obsolete factory buildings, reorganize functional structures, and enhance spatial efficiency through renewal, thereby achieving efficient land use under autonomous decision-making. In terms of representations of space, the government continuously optimizes regulatory frameworks, streamlines approval procedures, dynamically adjusts floor area ratios and land use indicators, and refines planning controls and design guidelines, providing institutional flexibility and support for enterprise-led renewal. At the level of representational spaces, the introduction of emerging industries and supporting services enriches the diversity of spatial experiences, reshapes spatial identity, and promotes collaboration between industry and community, facilitating the reintegration of social value and local culture. The interplay among these three dimensions forms a feedback loop from policy and regulation to practical implementation and socio-cultural recognition, effectively supporting high-quality, sustainable renewal of inefficient industrial land.

Figure 4.

Mechanisms of enterprise-initiated renewal.

4.3.2. Integration and Upgrading Type

This type of redevelopment focuses on resolving issues such as fragmented land parcels, diversified property rights, and the clustering of small, low-efficiency enterprises. Projects are typically led by the government or state-owned enterprises and are implemented through land consolidation, unified planning, and spatial reallocation, effectively increasing land-use intensity and industrial agglomeration. The process emphasizes policy and institutional innovation, including property rights clarification, spatial adjustment, and increased plot ratio, while also ensuring the targeted introduction of strategic emerging industries such as high-end manufacturing and next-generation information technology. These efforts facilitate a comprehensive shift from difficult governance and low output to integrated development and high efficiency.

- (1)

- Yongkang Modern Hardware Technology Industrial Park Project

The Modern Hardware Technology Industrial Park exemplifies the dynamic feedback mechanisms within the spatial triad. At the level of spatial practice, fragmented and inefficient industrial land in Suxi Village, covering 22.72 hectares and originally comprising one state-owned ceramics factory and five private hardware firms primarily engaged in leasing, was consolidated and restructured through collaborative efforts among government, enterprise, and village stakeholders. At the level of representations of space, the local government provided a clear institutional framework and policy instruments, such as plot ratio guidelines and building segmentation regulations, to regulate and guide redevelopment. At the level of representational spaces, as shown in Table 7, the park prioritized intelligent manufacturing and R&D, established standardized multi-story factories, a research institute, and talent services, thereby gradually shaping a renewed industrial identity. These outcomes coalesce into a new landmark image and into the everyday experience and recognition of a green ecological industrial park, which in turn strengthens governance instruments such as the industry admission catalogue, optimizes planning parameters and policy allocations, and thereby reinforces a virtuous cycle of property rights integration, safety standardization, industrial upgrading, and community shared prosperity. Overall, this case demonstrates a collaborative model for the renewal of inefficient industrial land that effectively integrates the interests of state-owned, private, and village stakeholders.

Table 7.

Pre- and post-redevelopment indicators for the Yongkang Modern Hardware Technology Industrial Park Project.

- (2)

- Cixi Derui Block Redevelopment Project

The Derui Block redevelopment project in Cixi, Ningbo, exemplifies the dynamic interplay among spatial practice, representations of space, and representational spaces as conceptualized by Lefebvre. At the level of spatial practice, the project transformed an inefficient and fragmented 4.1-hectare former textile site with a floor area ratio of only 0.23. This area was previously divided among 44 small workshops. Through coordinated acquisition, clearance, and comprehensive reconstruction led by the industry association, the total building area expanded to 94,118 square meters, and the floor area ratio increased to 3.0, as shown in Table 8, significantly enhancing land use efficiency and productivity. At the level of representations of space, municipal policies provided clear institutional direction, facilitating collaboration between the industry association and enterprises to promote land revitalization, industrial clustering, and spatial reorganization. This regulatory framework ensured effective project implementation and efficient spatial coordination. At the level of representational spaces, the introduction of new facilities and high-end production lines enabled a transition from low-end textile processing to a modern, technology-intensive industrial base, reshaping spatial identity and fostering enterprise recognition. In terms of the feedback mechanism, spatial reproduction played a key role in the redevelopment of the Derui block, significantly enhancing the regional industrial agglomeration effect and promoting the optimization and restructuring of the industrial chain. Throughout the implementation of the project, the government flexibly adjusted policies based on actual feedback, particularly by optimizing according to the characteristics of the light textile industry. For instance, the government not only promoted the planning of the agglomeration area but also facilitated the establishment of a company through the collaboration of industry associations and enterprises, addressing issues such as inefficient land use and poor spatial layout. This feedback process further strengthened the targeted and effective nature of policies at the spatial level, enabling spatial reproduction to better adapt to changes in market demand and the need for industrial upgrading, thereby driving the transformation and enhancement of the regional industrial structure. Overall, the project serves as a model of government guidance combined with enterprise initiative, offering valuable insights for industrial land transformation and innovation in spatial governance.

Table 8.

Pre- and post-redevelopment indicators for the Derui Block redevelopment.

- (3)

- Shiqiaotou Town Xiantian Industrial Park

Within Lefebvre’s theory of spatial production, the redevelopment of the Xiantian Industrial Park in Shiqiaotou Town illustrates a dynamic interrelationship among spatial practice, representations of space, and representational spaces. At the level of spatial practice, to address the concentration of small-scale, inefficient enterprises, low land use efficiency, and outdated facilities, the town government initiated a phased strategy in 2023 that integrated demolition, remediation, and planning. This approach coordinated enterprise relocation, building clearance, and reconstruction, thereby enhancing land use intensity and the quality of industrial space. The first phase involved a total investment of CNY 248 million and a planned building area of 68,700 square meters, effectively releasing high-efficiency industrial land. At the level of representations of space, customized policies, coordinated management, and green, integrated planning facilitated efficient project implementation. At the level of representational spaces, as shown in Table 9, the image of the new park has evolved from one of low efficiency and fragmented land use to that of a modern industrial community integrating green manufacturing, advanced equipment, and talent housing. The redevelopment of Shiqiao Tou Xiantian Industrial Park reflects a dynamic feedback mechanism between government policy, enterprise needs, and land use optimization. The local government, through clear guidelines and strong policy support, facilitated the transformation of low-efficiency industrial land. This allowed for the revitalization of the industrial park by addressing enterprises’ needs, such as offering tailored solutions for factory relocation, improving infrastructure, and providing financial incentives. The government also organized consultations with enterprises, allowing them to express their concerns and suggestions. These consultations, alongside the implementation of policies to attract high-quality enterprises, led to a more efficient use of land and the creation of a modern, high-standard industrial park. These material and organizational gains coalesce into the image and lived experience of a green, net-zero industrial park and a model industrial community at the township level, catalyzing investment attraction, concentrating capital, and bringing back talent while bolstering private firms’ confidence and willingness to participate in renewal. In turn, they spur the ongoing refinement of governance instruments, including industry entry rules and resettlement guarantees, thereby establishing a virtuous cycle of property rights integration, safety standardization, industrial upgrading, and shared community prosperity. This cycle shifts old industrial districts from extensive low-efficiency operations to coordinated high-end development and transforms formerly barren industrial land into a productive asset base. This case offers a replicable model for the revitalization of inefficient industrial land in small and medium-sized cities.

Table 9.

Pre- and post-redevelopment indicators for Shiqiaotou Town Xiantian Industrial Park.

- (4)

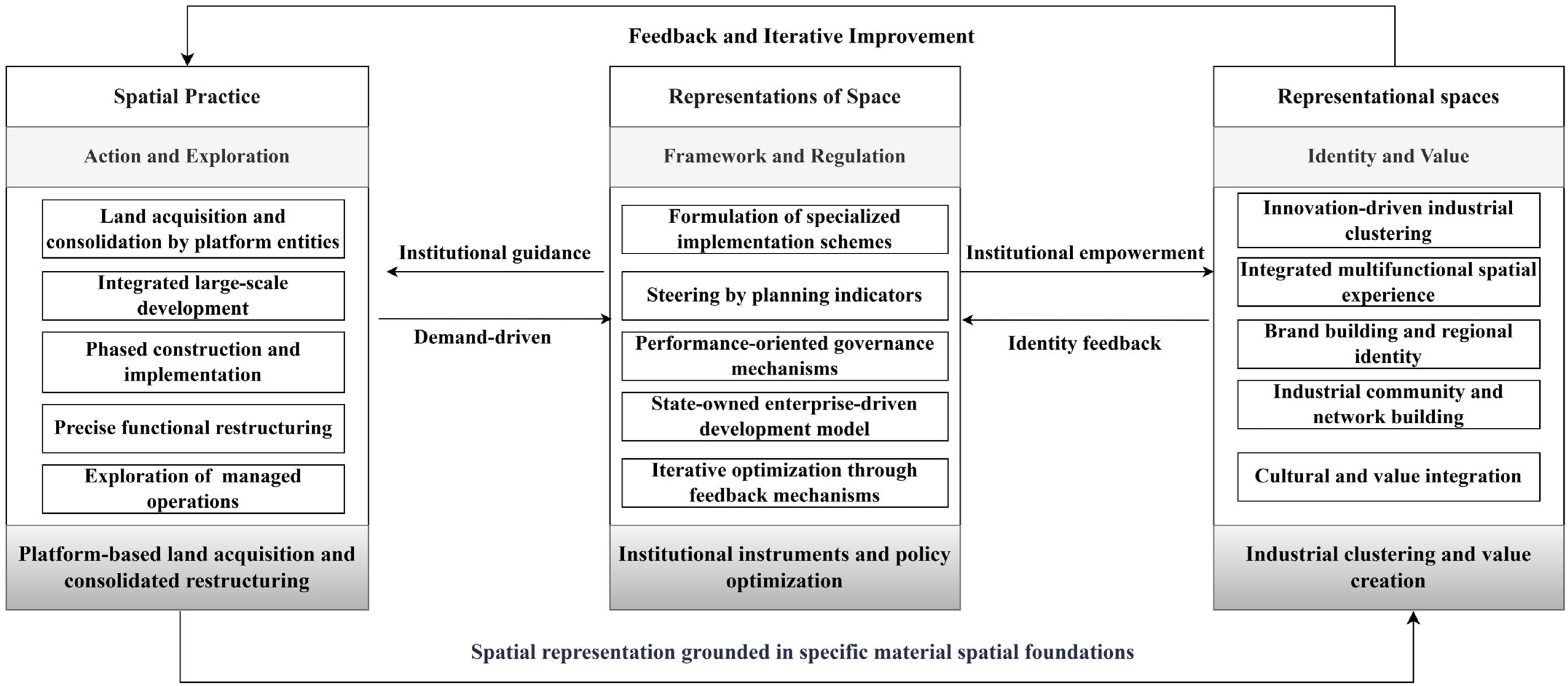

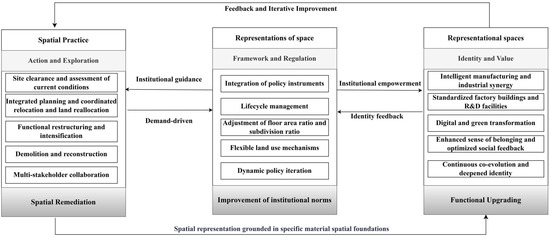

- Mechanisms of the Integration and Upgrading Type

As shown in Figure 5, in the integrated enhancement model of inefficient industrial land redevelopment, the spatial production triad drives systematic project upgrading. Spatial practice encompasses site clearance, unified planning, functional restructuring, and multi-stakeholder collaboration. Representations of space center on integrated policy tools, lifecycle management, and flexible land-use frameworks that are continuously refined through practical feedback. Representational spaces are shaped by the introduction of intelligent manufacturing, standardized facilities, and the strengthening of enterprise and social identity through sustained feedback loops. This dynamic triadic mechanism supports the continuous optimization of both practice and policy, offering a replicable pathway for the high-quality transformation of inefficient industrial land in urban contexts.

Figure 5.

Mechanism of the integration and upgrading type.

4.3.3. Platform Empowerment Type

The platform-empowerment type refers to redevelopment projects led by state-owned enterprises or platform companies, which drive the systematic upgrading and high-quality transformation of inefficient industrial land through resource integration, unified development, standardized operations, and comprehensive service provision. This approach emphasizes the organizing and coordinating capacity of state-owned platforms in land acquisition, large-scale consolidation, and spatial restructuring, as well as their enabling role in unified planning, industrial recruitment, intelligent management, public services, and ecological development. Leveraging advantages in capital, management, and industrial resources, platform companies facilitate the transformation of industrial parks from traditional, inefficient production spaces into comprehensive industry platforms that attract high-end industries and foster innovation-driven, sustainable development.

- (1)

- Phase I of Changhe Industrial Park

The Phase I redevelopment of Changhe Industrial Park in Binjiang District illustrates the dynamic interaction among spatial practice, representations of space, and representational spaces. At the spatial practice level, the project adopted an integrated model of government acquisition, targeted renovation, and unified leasing to explore new pathways for the renewal of existing industrial land. Covering 11 hectares, the site originally housed 13 traditional manufacturing firms focused on metal processing and color printing, characterized by outdated and fragmented facilities. The government led the unified acquisition and clearance of 33 factory buildings, followed by customized redevelopment to meet the spatial needs of biomedical and high-tech industries, resulting in a thorough restructuring of the spatial layout. At the representations of space level, the project adhered to unified planning, renovation, leasing, and operation principles, establishing a systematic institutional framework. The government, through a district-owned platform, guided the entire process and ensured that spatial and policy requirements were aligned with the needs of emerging industries. Clear criteria for tenant types, approval procedures, and rental mechanisms guaranteed that the renewed park was well-matched with strategic industrial projects, promoting standardized and orderly spatial use. At the representational spaces level, the redevelopment enhanced the park’s multifunctionality and ecological value, improved its integration with the surrounding urban area, and strengthened the site’s social significance and industrial identity. The redevelopment of Changhe Industrial Park illustrates a dynamic feedback mechanism between government policy, enterprise needs, and land use optimization. The local government’s decision to acquire and revitalize underutilized industrial land provided a foundation for transforming outdated facilities. The government’s effective engagement with businesses, including tailored plans for factory relocation and space redesign, helped ensure a smooth transition. These material and organizational outcomes further sediment into a representational space that functions both as a new industrial landmark where R&D and manufacturing operate in concert and as a locus of high-quality everyday experience, strengthening the park’s brand and its appeal to high-tech firms, capital, and talent. In turn, they consolidate and refine the unified solicitation-and-leasing rules, entry thresholds, and operating standards, enabling policy instruments to be replicated at broader scales, thereby creating a virtuous cycle of property-rights integration, safety standardization, and industrial upgrading, and continually transforming underutilized stock space into a growth pole for high-quality development. After redevelopment, as shown in Table 10, per-unit tax revenue increased more than sixfold, creating an efficient model where new spaces support new industries. Overall, this project demonstrates effective coordination between policy and practice, successfully transforming traditional industrial space into a modern, high-value industrial park. This case enhances land use and industrial capacity, providing a practical and theoretical model for renewing inefficient industrial land in other cities.

Table 10.

Pre- and post-redevelopment indicators for Phase I of Changhe Industrial Park.

- (2)

- Zhaobao Intelligent Manufacturing Valley Industrial Park Project

The project employs an integrated model of “state-owned enterprise acquisition, large-scale redevelopment, and spatial restructuring,” systematically illustrating the dynamic coupling among spatial practice, representations of space, and spaces of representation as theorized by Lefebvre. At the spatial practice level, a district-level state-owned enterprise acted as the sole developer, acquiring the former Zhenhai Thermal Power Plant and adjacent inefficient land for comprehensive consolidation and restructuring. This enabled the creation of a high-quality innovation complex that integrates technology incubation, pilot R&D, advanced manufacturing, industrial services, and supporting amenities, thereby achieving intensive land use and functional optimization, as shown in Table 11. At the representations of space level, the government formulated unified policies for planning, redevelopment, investment promotion, and operations. Documents such as the “Park Admission Management Measures” and “Investment and Leasing Plan” established clear standards for industry access, industrial output, energy consumption, and environmental protection. Performance-oriented, green, and digital management mechanisms ensured that diverse enterprise needs were precisely met, reinforcing the alignment of spatial organization and institutional frameworks. At the level of representational spaces, the park introduced high-end industries such as intelligent manufacturing and the digital economy, which facilitated the integration of industry, academia, and research, as well as the development of a modern industrial community. The redevelopment of this project highlights key feedback mechanisms, influencing policy adjustments and spatial development. The project’s outcomes led to continuous policy refinement in land use and industrial centralization. The park’s design evolved based on enterprise needs, enhancing services and attracting high-quality tenants. The “1+N” investment attraction mechanism, with clear industry standards and incentives, helped adjust industrial policies based on initial business success. Additionally, a digital management platform improved operational efficiency, enabling data-driven policy adjustments. These feedback processes ensured the park’s adaptive and sustainable development, aligning policies with its evolving needs. This dynamic generates a virtuous cycle, offering a replicable model for efficient land redevelopment and the cultivation of high-quality industrial spaces.

Table 11.

Pre- and post-redevelopment indicators for Zhaobao Intelligent Manufacturing Valley Industrial Park Project.

- (3)

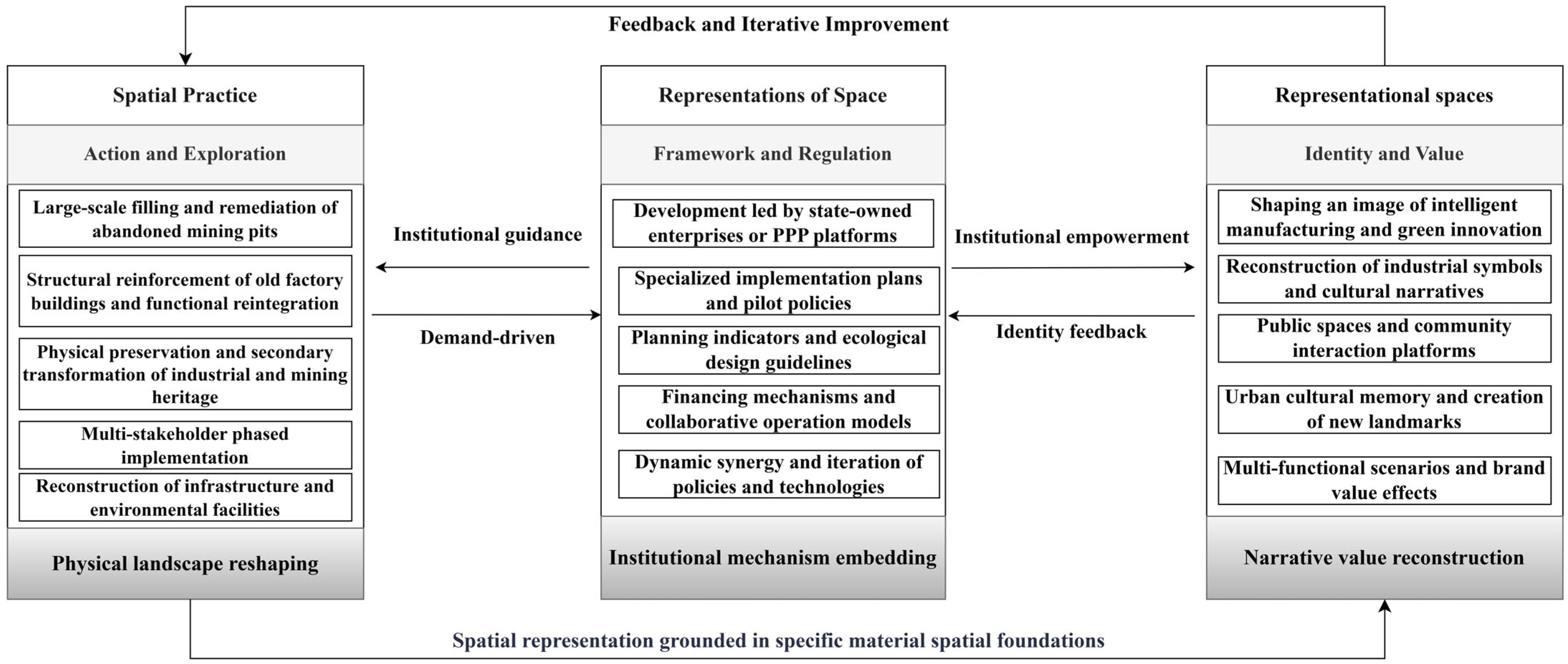

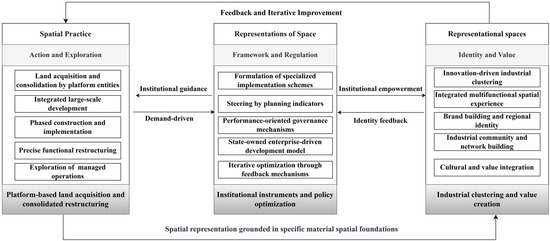

- Mechanisms of the Platform-Empowerment Type

As shown in Figure 6, in the platform-empowered model, state-owned enterprises lead the acquisition and integrated redevelopment of inefficient industrial land, advancing projects in phases and reconfiguring functional layouts to enhance land-use efficiency. Local governments formulate targeted implementation plans and utilize performance-based feedback to iteratively refine institutional frameworks. The platform-enabled pathway consolidates parcels and advances phased redevelopment to reconfigure functions, introduces research and development and manufacturing spaces and business service platforms, and adds public open space and community and cultural facilities, establishing the conditions for innovative industrial clustering, diversified spatial experience, and a reinforced local identity. This model illustrates how resource integration and professional management can facilitate the high-quality transformation of industrial land, offering a replicable strategy for urban renewal.

Figure 6.

Mechanism of the platform-empowerment type.

4.3.4. Comprehensive Spatial Remediation Type

This type of project features comprehensive renewal characterized by integrated planning, joint village-enterprise development, and coordinated industrial-ecological upgrading. The scope of renewal extends beyond individual industrial parks to encompass entire towns, typically starting with the remediation of outdated industries and ecological restoration. Through the “relocation and agglomeration” approach, the projects promote industrial concentration and modernization. Led by the government and involving social capital or village collectives, implementation pathways include land equity participation, unified development, and centralized operations, achieving simultaneous industrial upgrading and collective rural economic growth. Emphasis is also placed on ecological restoration and the improvement of living environments, forming a typical model of coordinated advancement across industry, ecology, and common prosperity.

- (1)

- Meishan Town Industrial Comprehensive Renovation

The comprehensive industrial remediation in Meishan Town exemplifies the cyclical interaction of spatial practice, representations of space, and representational spaces. Spatial practice involved phasing out inefficient enterprises, restoring abandoned mines, and consolidating nearly 200 hectares of fragmented industrial land, significantly improving land use and enabling large-scale renewal. Among these measures, refined strategies such as the “five-color zoning” system for land classification have significantly improved the identification and functional categorization of land parcels, laying a solid practical foundation for the adjustment of the park’s spatial structure. At the representations of space level, the town implemented targeted policies, such as the “Three-Year Action Plan for Comprehensive Industrial Remediation,” along with performance evaluation and planning guidance, to redirect resources toward emerging industries like photovoltaics and hydrogen energy. At the level of representational spaces, as shown in Table 12, institutional measures have enabled the government to reshape the value system of industrial land, thereby facilitating its transition from traditional to high-end, green industrial spaces and redefining both the physical landscape and the social identity of Meishan Town’s industrial area. The redevelopment of Meishan Town demonstrates a dynamic feedback mechanism where policy adjustments, enterprise demands, and industrial transformation mutually reinforced each other. The government’s “Five-Color Method” prioritized the categorization of enterprises based on efficiency, which led to targeted land use optimization and industrial restructuring. As emerging industries like hydrogen energy and photovoltaics expanded, the government swiftly responded to their needs by providing reclaimed land for new projects. The closure of outdated, high-energy-consuming industries and the introduction of high-tech sectors spurred economic growth and encouraged further investment, strengthening the town’s industrial clusters. Moreover, the shift to green manufacturing improved both the economy and the environment, creating a feedback loop that informed ongoing urban renewal policies. These interconnected feedback processes ensured the successful, sustainable transformation of Meishan into a modern, green industrial hub. Overall, Meishan’s approach demonstrates not just physical transformation but a systematic spatial production rooted in institutional innovation and regional value upgrading, offering a model for township-level industrial remediation in China.

Table 12.

Pre- and post-redevelopment indicators for Meishan Town industrial comprehensive renovation.

- (2)

- The Project of the Dual Innovation Centers in Taozhuang Town

From the perspective of spatial production theory, the Project of the Dual Innovation Centers in Taozhuang Town illustrates the profound interplay among spatial practice, representations of space, and representational spaces, establishing a spatial reproduction mechanism driven by local government leadership, industrial platform support, and ecological transformation. Spatial practice entailed comprehensive remediation of inefficient and polluted spaces in an area previously dominated by dispersed scrap steel enterprises, which posed significant barriers to sustainable development. The Taozhuang government implemented a “phasing out and clustering” strategy, removing over 1200 operators and demolishing more than 1.1 million square meters of unauthorized or obsolete buildings. This process significantly enhanced land and environmental capacity, laying a solid foundation for the introduction of new, high-quality industries. At the level of representations of space, the local government, guided by the “Two Mountains” theory, adopted a phased strategy encompassing clearance, construction, and management to drive the transformation of both industrial structure and spatial organization. Land from fourteen villages was consolidated through a collective shareholding model, enabling coordinated resource utilization and equitable distribution of economic benefits. The newly developed 113,600-square-meter industrial park is organized to accommodate scrap steel processing and warehousing functions, embodying the integration of circular economy principles into both policy formulation and spatial planning. As shown in Table 13, in terms of representational spaces, the entry of leading enterprises has established a modern industrial structure focused on advanced manufacturing and new materials, while initiatives such as the “Taozhuang Chengkuang Scrap Steel Price Index” have strengthened the park’s industrial identity. The project has also improved rural environments and increased collective income, transforming the area into a green and multifunctional community. The redevelopment of Taozhuang Town highlights a feedback mechanism where policy adjustments, industrial transformation, and enterprise needs are interconnected. The government’s decision to remove outdated industries and relocate businesses created space for new projects, including the Two-Innovation Center. This allowed for the integration of high-tech sectors such as green manufacturing and new materials, which in turn informed further policy refinements in land use and industrial clustering. The demand from enterprises, such as scrap steel processors, led to optimized land allocation, while the success of emerging industries contributed to economic growth, increased tax revenue, and employment, further driving infrastructure and service improvements. The shift to green manufacturing also improved the town’s environmental quality, reinforcing the commitment to sustainable development and supporting continued growth. Overall, Taozhuang’s institutionalized redevelopment preserves the industrial base and promotes economic growth, with ongoing ecological improvements supporting urban–rural integration and reinforcing spatial identity, thus fostering a positive cycle of green development and shared prosperity.

Table 13.

Pre- and post-redevelopment indicators for the project of the dual innovation centers in Taozhuang Town.

- (3)

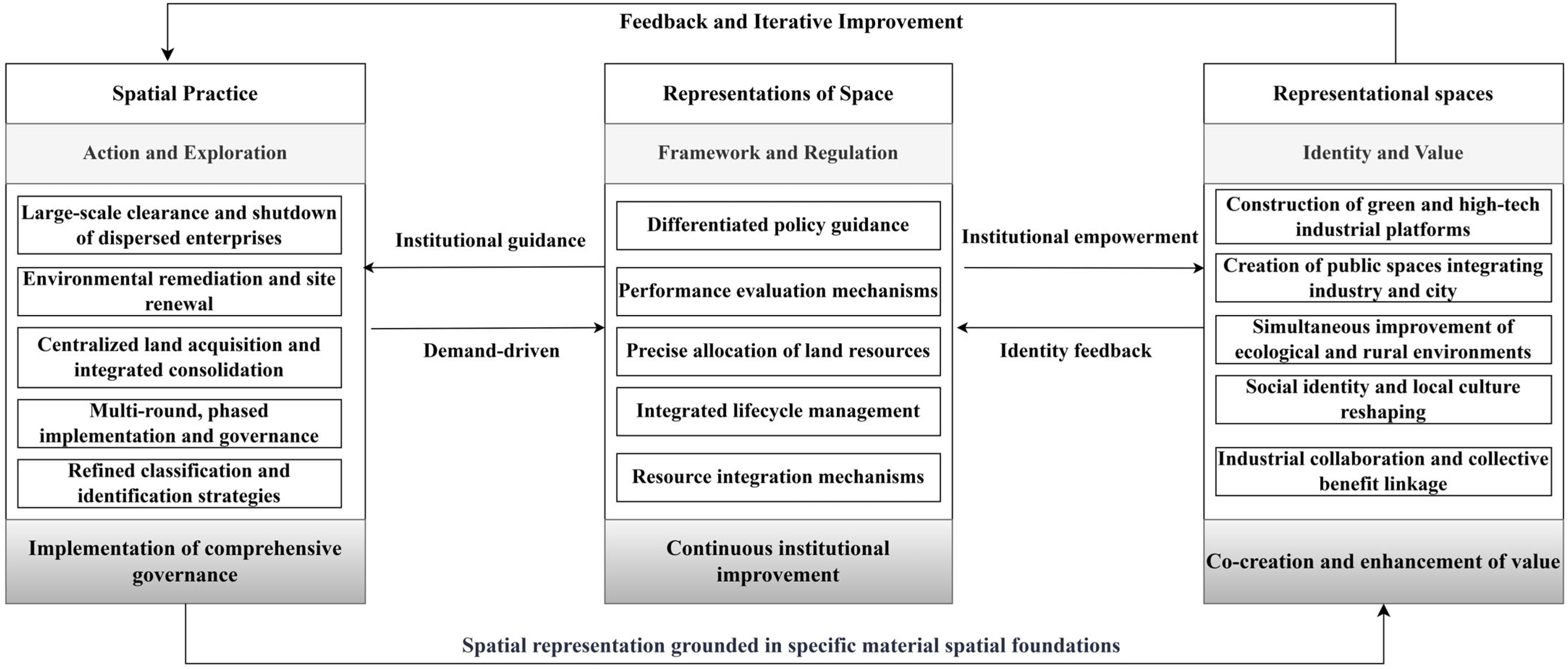

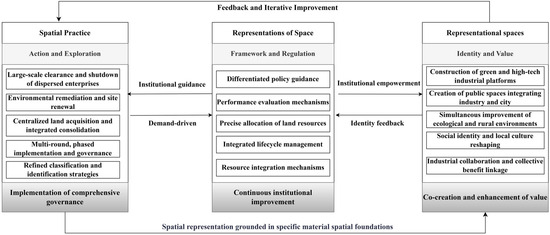

- Mechanisms of the Comprehensive Spatial Remediation Type

As shown in Figure 7, The comprehensive spatial remediation model for inefficient industrial land utilizes the triadic structure of spatial production to drive comprehensive upgrading. Spatial practice encompasses large-scale clearance of scattered enterprises, land consolidation, phased redevelopment, and targeted site classification as key measures to optimize land use efficiency. In terms of representations of space, differentiated policies, performance evaluations, and lifecycle management mechanisms serve to guide and refine the redevelopment process. Representational space is shaped through the development of green industrial platforms, the creation of public spaces that promote urban-rural integration, and initiatives aimed at reinforcing local identity and enhancing collective economic benefits. This dynamic interplay among institutional frameworks, practical implementation, and social meaning ensures effective policy adaptation and offers a replicable model for sustainable industrial land redevelopment.

Figure 7.

Mechanism of the comprehensive spatial remediation type.

4.4. Qualitative Transformation Pathways and Practical Expressions

Among the various pathways for the redevelopment of inefficient land, qualitative transformation pathways are characterized by a fundamental reconfiguration of original land functions. Rather than simply increasing plot ratio or substituting industries, these pathways achieve a cross-boundary transformation of land use, endowing land with new social meanings and development trajectories. Such approaches realize a leap in spatial value and a restructuring of social functions through methods such as ecological restoration of former mining sites, the creation of cultural and tourism destinations, and functional land-use conversion.

4.4.1. Mine Land Remediation Type—South Taihu Geely New Energy Vehicle Supporting Industrial Park

Viewed through Lefebvre’s spatial triad, the redevelopment of the South Taihu New Energy Vehicle Supporting Industrial Park in Changxing County exemplifies a model of qualitative transformation and enhancement centered on mine remediation, ecological restoration, and industrial upgrading. As shown in Table 14, the project area, once a limestone mining zone marked by fragmented terrain and inefficient land use, underwent a significant transformation as the local government implemented targeted land remediation, enterprise relocation, and the integration of state-owned and newly added construction land. These interventions enabled the release of over 286 hectares of land for high-value industrial use, signifying a shift from peripheral, resource-dependent land use to a strategically positioned regional growth hub. At the level of representations of space, local authorities provided sustained institutional leadership by establishing a dedicated management platform, introducing a public–private partnership (PPP) model to address funding constraints, and commissioning comprehensive ecological and industrial master planning. These measures ensured coherence between policy objectives and spatial outcomes. In terms of representational spaces, the introduction of flagship projects such as the Geely Automobile Data Center and its associated industrial chain rapidly established the park’s identity as a center for intelligent manufacturing. The redevelopment of the project showcases a feedback mechanism where policy adjustments, enterprise needs, and land use optimization are interconnected. The county government’s decision to repurpose abandoned mining land provided space for industrial development, which was further supported by infrastructure improvements such as roadways and utilities. The demand for large industrial spaces from companies like Geely drove the optimization of land use, creating a cycle where the park’s growth prompted additional development. The environmental remediation of the site, transforming it from a polluted mining area to a green industrial park, attracted further investment, and the resulting economic benefits, including increased tax revenue and employment, fueled continued infrastructure improvements, completing a cycle of sustainable development. Overall, this case demonstrates how institutional restructuring, coordinated spatial practice, and the evolution of industrial identity can synergistically drive the comprehensive transformation and re-embedding of inefficient land within a regional innovation system.

Table 14.

Pre- and post-redevelopment indicators for South Taihu Geely new energy vehicle supporting industrial park.

4.4.2. Culture and Tourism Empowerment Type—Dongyu Industrial Heritage Park

As a major pilot for urban renewal in Wenzhou, the “Light of Wenzhou” Dongyu Industrial Heritage Park exemplifies a triple transformation across physical, social, and cultural dimensions. As shown in Table 15, the project involves a total planned investment of CNY 1.84 billion and encompasses 152,000 square meters of integrated public space. In terms of spatial practice, the systematic remediation and adaptive reuse of the derelict factory transformed a closed, single-function industrial site into an open, multifunctional public venue. Structural reinforcement and façade renovation preserved the industrial heritage while accommodating new and diverse uses. At the level of representations of space, the municipal government prioritized the site as a key urban renewal initiative, implementing it through a state-owned development platform. The planning integrates energy science, industrial education, and cultural tourism, emphasizing both the green energy transition and the preservation of urban memory. The design strategy focuses on achieving synergy between public accessibility, cultural vibrancy, and commercial viability, enhancing local identity through iconic spatial nodes such as the Boiler Café and rooftop viewing platform. In representational spaces, cultural elements such as the park’s branding, public art installations, and references to local history reposition Dongyu as a center of collective memory and cultural identity. The former industrial core now serves as a civic and creative gathering space, redefining the social and symbolic value of the urban environment. The redevelopment of Dongyu Industrial Heritage Park showcases a dynamic feedback mechanism where policy decisions, industrial heritage preservation, and modern demands interact. The local government’s decision to transform the high-energy-consuming, polluting plant into a cultural and commercial hub created space for new functions while preserving key industrial elements. This adaptive reuse of the site has led to a cycle where the success of the initial phases, including leisure spaces and the energy museum, further encouraged expansion and integration of modern uses. The project’s focus on both ecological restoration and cultural preservation has enhanced the environmental quality, attracting more visitors and businesses. These feedback processes have not only driven the site’s revitalization but also demonstrated how industrial heritage can contribute to sustainable urban renewal. Overall, the “Light of Wenzhou” project illustrates an effective model for transforming industrial heritage into high-quality public space, offering a replicable strategy for urban regeneration and the adaptive reuse of inefficient land.

Table 15.

Pre- and post-redevelopment indicators for the Dongyu Industrial Heritage Park.

4.4.3. Land-Use Conversion Type—Shouchang Town Yuhao Electronics

The Yuhao Electric redevelopment project exemplifies an institutional and practice-led approach to revitalizing inefficient industrial land within the context of evolving urban and industrial dynamics. At the level of spatial practice, the government facilitated a land-use conversion from industrial to commercial purposes (“industry-to-commerce”), enabling the adaptive reuse of idle factory land for hospitality, wellness, and office services. As shown in Table 16, this transformation resulted in a multifunctional complex that supports over 100 new jobs and accommodates more than 300 daily visitors, effectively integrating the site into the local tourism and service economy. At the level of representations of space, Jiande City implemented planning-led institutional reform, establishing an integrated mechanism that spans planning adjustments, interdepartmental review, and contract transfer. As a pilot for land use conversion, the Yuhao project expedited the release of local redevelopment guidelines and demonstrated the practical feasibility of the associated policy instruments. In representational spaces, the project enhanced the identity and attractiveness of the Henggang area by transforming underutilized factory space into a key node for regional tourism and cultural activity, aligning with broader city branding and economic revitalization objectives. The redevelopment of the project illustrates a feedback mechanism where policy, enterprise needs, and land use optimization interact. The local government’s implementation of guidelines for “industrial-to-commercial” land conversion allowed the company to repurpose its underutilized industrial land into a commercial service area, including wellness and hotel facilities. This transformation addressed the company’s challenges and activated the space for new commercial uses. The project generated significant economic benefits, including increased revenue from hotel operations and the creation of over 100 local jobs, which further fueled the area’s development. These outcomes further crystallize into a nodal landmark identity oriented to cultural tourism and wellness, together with a high-quality everyday experience, strengthening the location’s brand and its appeal to capital and talent. In turn, they prompt the continued refinement and wider replication of the “industrial to commercial” conversion procedures and the rules for land transfer and oversight, improving institutional enforceability and the efficiency of factor allocation. This generates a virtuous cycle of property and land-use reconfiguration, safety and compliance standardization, industrial and business-format upgrading, and integrated development of industry, city, and tourism, continually transforming underutilized stock space into a growth pole for high-quality development. Overall, this project illustrates how institutional flexibility and the synergy between policy and practice can unlock the potential of inefficient industrial sites. It provides a valuable model for integrated land redevelopment at the county level and the strategic integration of urban development with tourism-driven growth.

Table 16.

Pre- and post-redevelopment indicators for the Shouchang Town Yuhao Electronics.

4.4.4. Mechanism of the Qualitative Transformation Type