Abstract

Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) has adverse effects on aquatic life, including algae, crustaceans, and even fish. However, the freshwater quality criteria for the protection of aquatic life (ALFQC) of SMX are still unclear, as well as its ecological risk for surface waters in China. The acute and chronic toxicity data for SMX covered 10 and 11 species, respectively, which are widely distributed across China. The native species in China of Raphidocelis subcapitata displayed the most sensitivity after short-term exposure, whereas Lemna gibba showed the most sensitivity after long-term exposure to water contaminated with SMX. The short-term and long-term ALFQC of SMX were 2829 and 23.63 µg/L, respectively using the species sensitivity distribution in China. The 112 exposure data were collected from peer-reviewed publications and government reports published between 2006 and 2024, with the concentrations of SMX ranging from 0 to 0.531 µg/L in surface waters in China. A negligible ecological risk of SMX was observed in surface waters in China, confirmed by the low risk quotient (0~0.0225) and probability area overlap (0~0.005). This study provides a scientific basis for water quality standards and the ecological risk management for SMX in surface waters in China.

1. Introduction

Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) was a commonly used antibiotic in both human medicine and aquaculture due to its broad-spectrum antibacterial properties against a variety of bacteria [1,2]. SMX became a common emerging contaminant in surface waters environments across the world, because of the discharge of sulfonamide-containing wastewater and aquaculture drainage after application [3]. Data from the USGS highlight SMX as a priority pollutant, ranking it among the top 30 contaminants frequently found in wastewater, with a persistence of 85–100 days [4]. Toxicological studies confirmed that SMX has adverse effects on aquatic life across different trophic levels [5,6]. For example, photosynthesis was inhibited after exposure at 9000 µg/L for 24 h by reducing chlorophyll production and disrupting cellular metabolism for Raphidocelis subcapitata under short-term exposure [5]. In addition, long-term exposure to low environmental doses of SMX (300 µg/L) was shown to downregulate gene expression related to cholesterol and bile acid synthesis in Micropterus salmoides at 24.5 °C and a dissolved oxygen level of 8000 µg/L [7]. Given the adverse effect of SMX for freshwater aquatic life in surface waters, there is a critical need to establish freshwater quality criteria for the protection of aquatic life (ALFQC).

ALFQC define the maximum permissible concentration of pollutants that do not have harmful effects on aquatic life [8,9]. ALFQC are recognized as a critical tool for establishing environmental quality standards and assessing ecological risks, forming a fundamental basis for pollution control [10]. The research on ALFQC for antibiotics has made significant progress with the process of ALFQC methodology for contaminants and toxicity data for antibiotics to aquatic life [11,12,13]. The species sensitivity distribution (SSD) was applied to derive the ALFQC, which estimates the protective concentrations for the majority of ecosystem species by fitting toxicity data to a statistical distribution [14]. The most widely adopted framework employs a two-tiered system comprising the short-term freshwater quality criteria for the protection of aquatic life (the short-term ALFQC) and the long-term freshwater quality criteria for the protection of aquatic life (the long-term ALFQC). For example, the short-term and long-term ALFQC for sulfonamide antibiotics of sulfamethazine (19,010 µg/L, 3550 µg/L) and sulfadimethoxine (510 µg/L, 100 µg/L) were calculated using the SSD method [15,16]. In addition, the water quality criteria for quinolone antibiotics were derived using the SSD method, and the short-term ALFQC of enrofloxacin and ciprofloxacin were 100 µg/L and 20 µg/L, while the long-term ALFQC were 60 µg/L and 10 µg/L [17,18]. However, systematic research on the ALFQC of SMX is limited.

The concentration data of pollutants serve as the foundation for risk assessment, and reliable contaminant concentration data are crucial for assessing the potential ecological risk [19]. Currently, extensive reports of SMX concentrations detected in surface waters worldwide provided essential support for its risk assessment [1]. Enormously high concentrations of SMX were observed in the Kshipra River, India (~4.66 μg/L), surface waters in Korea (21.3 μg/L) and the Nairobi River Basin, Kenya (20 μg/L~142.6 μg/L), the João Mendes River, Brazil (2.42 μg/L), as well as the Charmoise River, France (3.066 μg/L), respectively [20,21,22,23,24]. The concentrations of SMX in the surface waters of the Huangpu River of the Yangtze River, the Daliao River of the Songliao River, the YuenLong River upstream of Pearl River, and the Wangyanggou River of Hai River were 0.260 µg/L, 0.114 µg/L, 0.108 µg/L, and 0.529 µg/L, respectively in China [25,26,27,28]. The Risk Quotient (RQ) and probability area overlap methods are commonly used for risk assessment [29]. For example, the RQ values indicated that over 36 pharmaceuticals may pose health risks to the aquatic environment, while several antibiotics—including amoxicillin, sulfasalazine, trimethoprim, oxytetracycline, and erythromycin—demonstrated particularly high RQ values [30]. Diisobutyl phthalate posed a medium risk in both the Haihe River (RQ = 0.41) and the Hun River (RQ = 0.16) in China [31]. However, research on the risk assessment of SMX in surface waters is limited in China.

The objectives of this research are as follows: (1) to compare the sensitivities of various species by establishing a toxicity database for SMX to aquatic life, (2) to derive the ALFQC for SMX including the short-term and long-term ALFQC, (3) to assess the ecological risk of SMX based on the concentrations of SMX collected from peer-reviewed publications and government reports published between 2006 and 2024. This work provides important support for the formulation of water quality standards and the environmental management of SMX in the surface waters of China.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Screening and Collection

The median lethal concentration (LC50) and the median effect concentration (EC50) with an exposure time less than 96 h were chosen as measurement endpoints of the acute toxicity values (ATV) for SMX to freshwater aquatic life. The no observed effect concentration (NOEC), the lowest observed effect concentration (LOEC), the maximum acceptable toxicant concentration (MATC), and the EC50 were typically chosen as endpoints for the chronic toxicity values (CTV) with an exposure time more than 21 days or one generation of aquatic life [8,32]. During the derivation of the ALFQC, both ATV and CTV of SMX to aquatic life were collected from the literature and toxicity databases. In detail, the retrieval strategy of “TI = (Sulfamethoxazole) AND TS = (toxicity or LC50 or EC50 or NOEC or LOEC or MATC)” was applied to screen the ATV and CTV for SMX in the China knowledge resource integrated database (http://www.cnki.net/, accessed on 22 September 2025), Elsevier (http://www.sciencedirect.com, accessed on 22 September 2025), and Web of Science (http://www.webofscience.com, accessed on 23 September 2025), respectively. For the ECOTOX database (http://cfpub.epa.gov/ecotox, accessed on 15 September 2025), the retrieval strategy “Chemicals = (Sulfamethoxazole) and Effects = (all) and Endpoints = (LC50 and EC50 and NOEC and LOEC and MATC) and Species = (both animals and plants) and Test condition = (fresh water)” was employed to collect the ATV and CTV for SMX to protect aquatic life.

The LC50 and EC50 values for exposure durations of 24, 48, and 96 h were prioritized for Rotifera, Daphnia/Midges, and other species, respectively, to derive the short-term ALFQC for SMX. The MATC was calculated as the geometric mean of the NOEC and LOEC from certain species under the same experimental conditions to derive the long-term ALFQC for SMX [33]. The Daphnia magna and Lemna gibba, as universal species, were used to derive the ALFQC, because of the wide distribution in freshwater ecosystems across China. As a representative macrophyte, Lemna gibba typically initiated vegetative reproduction (frond multiplication) within 7 days, which corresponded to a complete reproductive cycle for this species [34]. Accordingly, international standard guidelines recommended a 7-day exposure duration for assessing growth inhibition in Lemna gibba, as specified in OECD Test No. 221 [35]. Furthermore, toxicity data for Lemna gibba obtained from 7-day exposure experiments were applied as chronic endpoints in the derivation of the Water Quality Criteria for Freshwater Aquatic Organisms—Phenol issued by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China [36]. Toxicity data with enzymes as the effect and lacking specific toxicity values, such as a defined concentration or dose, were excluded in the screening process.

The published exposure data for SMX in surface waters were collected based on individual measurements from the literature in the Web of Science and CNKI. The search words included the name of the searched compound and keywords such as “water”, “freshwater”, “wastewater”, “exposure”, and their flexible versions from 2006 to 2024. The country or geographic region, concentration range, average concentration, and site-specific measured concentrations were extracted from the literature. The selected references offered a detailed explanation of the specific procedures for data collection and detection, along with an introduction to the corresponding quality assurance measures or quality control systems.

2.2. ALFQC Derivation Methodology

During the derivation of the ALFQC, the short-term and long-term ALFQC were derived to provide an appropriate level of protection for aquatic life with ATV and CTV, respectively. The geometric mean of the available ATV and CTV for each species were designed as the species mean acute toxicity value (SMAV) and the species mean chronic toxicity value (SMCV), as shown in Equations (1) and (2), respectively. The SMAV and SMCV for all species were sorted in ascending order from the smallest (1) to the largest number of species from acute and chronic toxicity, respectively. The log-transformed SMAV/SMCV and its corresponding cumulative frequency distribution were employed to calculate the short-term/long-term ALFQC with the SSD method. Origin software (Origin pro 2024) was employed to fit the SSD curves, evaluating the suitability of four distinct statistical models: normal, log-normal, logistic, and log-logistic distributions. The fitness of the four distribution models was assessed and evaluated by the root mean square (RMSE) and probability p-value with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test [14]. The hazard concentration at the 5th percentile (HC5) was calculated with the best fitted distribution model based on the SMAV and SMCV, respectively using EEC-SSD (Version 1.0). The short-term and long-term ALFQC were calculated by dividing the acute and chronic HC5 values by the assessment factor (AF), which accounts for the uncertainty that arises when extrapolating toxicity data from a limited number of species to the ecosystem level. Typically, an AF of 3 was recommended when the number of species ranged from 4 to 15 for both ATV and CTV, as outlined in the technical guidelines for deriving ALFQC [33].

where m and n were the total number of ATV and CTV for certain species.

2.3. Ecological Risk Assessment

The risk quotients (RQ) and probability area overlap method were applied to assess the ecological risks caused by SMX in surface waters in China [29]. The RQ was calculated as the quotients of the concentration of SMX in surface waters divided by the long-term ALFQC [37]. The overlap area (OA) was calculated for the log-SMCV of aquatic life and the log-concentration of SMX in surface waters in China using the probability area overlap method with Python (version 3.12, Python Software Foundation) [29,32]. The preliminary risk assessment ranks of SMX were classified as low risk if RQ/OA < 0.1, moderate risk if 0.1 ≤ RQ/OA < 1, and high risk if RQ/OA ≥ 1.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Acute and Chronic Toxicity of SMX to Aquatic Species

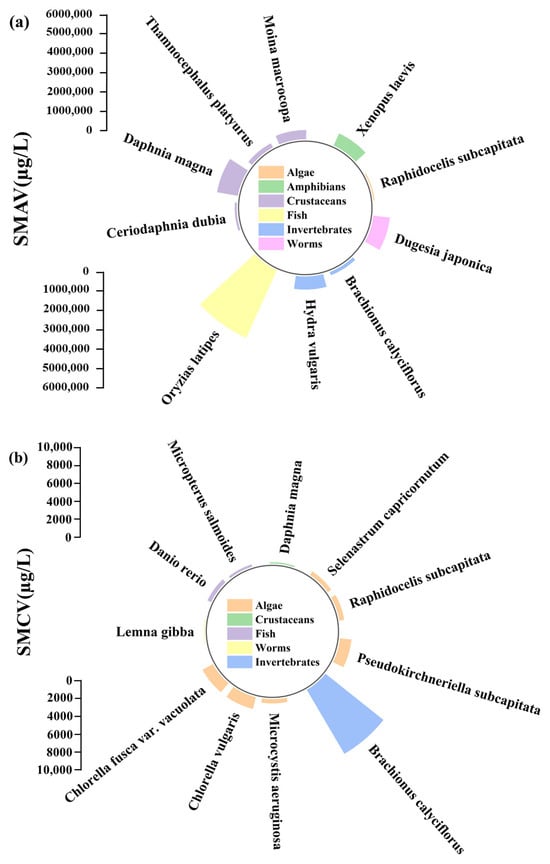

The acute and chronic toxicity data of SMX for native freshwater aquatic species in China were presented in Table 1 and Table 2. The ATV and CTV ranged from 9000 µg/L to 562,500 µg/L and from 10 µg/L to 9630 µg/L for SMX. The ATV for SMX included 10 native species in China, with the following distribution: one species of algae, one species of amphibian, four species of crustaceans, one species of fish, two species of invertebrates, and one species of worm (Figure 1a). The most sensitive species to SMX was Raphidocelis subcapitata with a 24 h EC50 of 9000 µg/L, while the second most sensitive species was Ceriodaphnia dubia with a 24 h EC50 of 15,510 µg/L for ATV in China (Table 1). The most tolerant species to SMX was Oryzias latipes with a 96 h LC50 of 562,500 µg/L, while the second most tolerant species was Daphnia magna with a 48 h LC50 of 234,180 µg/L for SMAV in China (Table 1). The ATV (562,500 µg/L) for the most tolerant species were approximately 63 times higher than the ATV (9000 µg/L) for the most sensitive species in this study.

Figure 1.

Radial plot of SMAV (a) and SMCV (b) across different aquatic life and species groups.

Regarding the CTV, 11 native species were identified in China, with the following distribution: six species of algae, one species of crustacean, two species of fish, one species of invertebrate, and one species of worm (Figure 1b). The most sensitive species to SMX was Lemna gibba with an NOEC and LOEC of 9–110 µg/L after exposure for 7 days, which made it a potential indicator of SMX contamination in the freshwater ecosystems under long-term exposure (Table 2). The high sensitivity of algae (e.g., Raphidocelis subcapitata) and plants (e.g., Lemna gibba) were due to the inhibition of the dihydropteroate synthase enzyme in the folate synthesis pathway [5,34]. The second most sensitive species was Daphnia magna to SMX with an NOEC and LOEC of 120–370 µg/L after exposure for 21 days. The most tolerant species to SMX was Brachionus calyciflorus with a 48 h EC50 of 9630 µg/L, while the second most sensitive species was Chlorella vulgaris with a 48 h EC50 of 1570 µg/L for SMCV in China, both of which were exposed over one generation during the experiment. The CTV (9630 µg/L) for the most tolerant species were approximately 963 times higher than the CTV (9 µg/L) for the most sensitive species in this study.

Table 1.

The rank of the SMAV of SMX to freshwater aquatic life in China.

Table 1.

The rank of the SMAV of SMX to freshwater aquatic life in China.

| Rank | Species Scientific Name | Species Groups | Endpoint | ATV (µg/L, ×103) | SMAV (µg/L, ×103) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Raphidocelis subcapitata | Algae | EC50 | 9 | 9 | [5] |

| 2 | Ceriodaphnia dubia | Crustacean | EC50 | 15.51 | 15.51 | [38] |

| 3 | Brachionus calyciflorus | Invertebrate | LC50 | 26.27 | 26.27 | [38] |

| 4 | Thamnocephalus platyurus | Crustacean | LC50 | 35.36 | 35.36 | [38] |

| 5 | Moina macrocopa | Crustacean | EC50 | 70.4 | 70.4 | [39] |

| 6 | Xenopus laevis | Amphibian | EC50 | 100 | 100 | [40] |

| 7 | Hydra vulgaris | Invertebrate | LC50 | 100 | 100 | [41] |

| 8 | Dugesia japonica | Worm | LC50 | 126.7 | 126.7 | [42] |

| 9 | Daphnia magna | Crustacean | EC50, LC50 | 96.7–234.18 | 159.83 | [39,43,44] |

| 10 | Oryzias latipes | Fish | LC50 | 562.5 | 562.5 | [45] |

Table 2.

The rank of the SMCV of SMX to freshwater aquatic life in China.

Table 2.

The rank of the SMCV of SMX to freshwater aquatic life in China.

| Rank | Species Scientific Name | Species Groups | Endpoint | CTV (µg/L, ×103) | SMCV (µg/L, ×103) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lemna gibba | Worm | NOEC, LOEC | 0.009–0.11 | 0.03 | [34,46] |

| 2 | Daphnia magna | Crustacean | NOEC, LOEC | 0.12–0.37 | 0.17 | [44] |

| 3 | Micropterus salmoides | Fish | LOEC | 0.3 | 0.3 | [7] |

| 4 | Danio rerio | Fish | NOEC | 0.53 | 0.53 | [47] |

| 5 | Selenastrum capricornutum | Algae | NOEC, LOEC | 0.5–0.61 | 0.55 | [6,48] |

| 6 | Microcystis aeruginosa | Algae | EC50 | 0.55 | 0.55 | [5] |

| 7 | Raphidocelis subcapitata | Algae | NOEC, LOEC | 0.5–0.8 | 0.63 | [49] |

| 8 | Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata | Algae | NOEC | 1.5 | 1.5 | [6] |

| 9 | Chlorella vacuolata | Algae | EC50 | 1.54 | 1.54 | [50] |

| 10 | Chlorella vulgaris | Algae | EC50 | 1.57 | 1.57 | [51] |

| 11 | Brachionus calyciflorus | Invertebrate | EC50 | 9.63 | 9.63 | [38] |

3.2. ALFQC of SMX for China

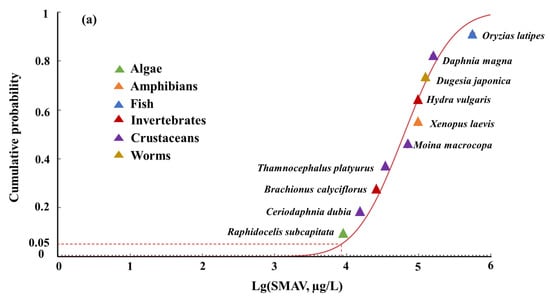

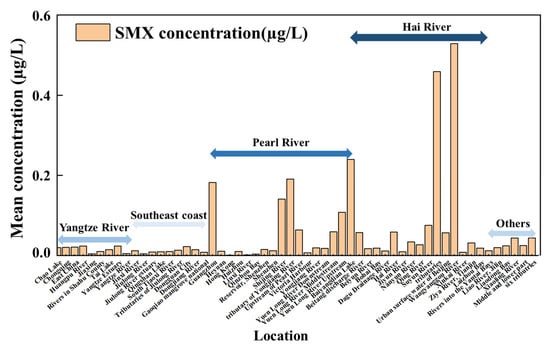

The short-term and long-term ALFQC were calculated based on the SMAV and SMCV using the SSD, respectively in China. The RMSE values for the normal, log-normal, logistic, and log-logistic distribution models were calculated as 0.0543, 0.0588, 0.0619, and 0.0646, respectively for the SMAV of aquatic life in China (Table 3). Similarly, the SSD curves were applied to fit the SMCV, resulting in RMSE values of 0.0626, 0.0669, 0.0634, and 0.0811 for the logistic, normal, log-logistic, and log-normal distribution models, respectively (Table 3). The normal distribution model and logistic distribution model were selected as the best fitting models for the SMAV and SMCV of SMX, respectively, because of the lowest RMSE values and statistically significant fitness (p > 0.05), to derive the ALFQC in China (Figure 2 and Table 3). The acute and chronic HC5 values were calculated as 8489 µg/L and 70.91 µg/L, respectively to protect freshwater aquatic life at the 95th percentile. When the AF was set to 3, the short-term ALFQC of SMX was calculated as 2829 µg/L, and the long-term ALFQC of SMX was calculated as 23.63 µg/L (Table 3). The quantitative or semi-quantitative approaches should be considered instead of arbitrary AF values based on the species number, trophic levels, and model uncertainty of the SSD. In addition, the deterministic predicted no-effect concentration (PNEC) for SMX based on chronic toxicity data from 16 species was 0.59 µg/L in Europe [52]. The differences in long-term ALFQC between this study and European could primarily be attributed to the toxicity data, species composition, and the derivation method used [11,14]. In detail, Synechococcus leopoliensis was identified as the most sensitive species in Europe, and Lemna gibba was identified as the most sensitive species in deriving the long-term ALFQC in the study using native species data. Furthermore, the SSD method was applied to derive the long-term ALFQC based on toxicity data from multiple species and the distribution curve of species sensitivity in the study, and the PNEC method was used to derive the long-term ALFQC by selecting a concentration corresponding to certain toxicity data in Europe. Both the different ATV and CTV set and derivation methods could lead to variations in the thresholds to protect aquatic life. The variations in criteria values resulting from different data sets and derivation methods should be taken into consideration for water quality standard setting and ecological risk management in China.

Table 3.

Fitting results of ALFQC SSD model and hazard concentration for short-term species and long-term species.

Figure 2.

The SSD curves of the log-SMAV (a) and the log-SMCV (b) of SMX for freshwater aquatic life in China.

3.3. Ecological Risk Assessment for SMX in China

3.3.1. Concentration of SMX in Surface Waters

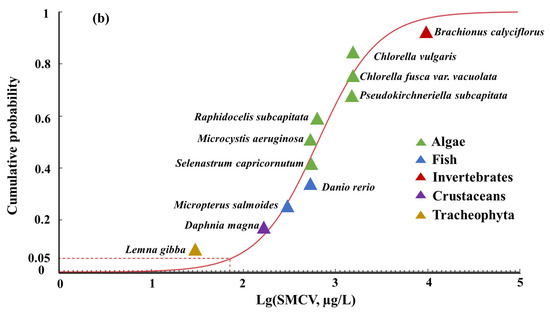

The 37, 15, 21, and 31 exposure data of SMX (Table S1) were collected from the Yangtze River, Southeast Coast, Pearl River, and Hai River watersheds in China [18,25,26,28,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86]. Due to the limited number of available samples (fewer than seven exposure data points), the Huai River, Songliao River, and Yellow River watersheds were combined and categorized as other watersheds [27,87,88,89] (Figure 3, Table S1). The exposure concentration of SMX ranged from 0 to 0.531 µg/L with a mean exposure concentration of 0.0519 µg/L in the surface waters in China. The Haihe River watershed (0.1012 µg/L) showed the highest mean concentration of SMX, followed by the Pearl River Delta watershed (0.063 µg/L), Yangtze River watershed (0.0289 µg/L), Southeast Coast (0.0112 µg/L), and others (0.0271 µg/L) (Songliao River watershed, Huai River watershed, Yellow River watershed), based on the mean exposure concentration of each watershed (Table S1). Detailed analysis showed that the highest concentration of SMX was observed in Guangzhou City (0.531 µg/L) of the Pearl River watershed, followed by the Wangyanggou River (0.529 µg/L) of the Hai River watershed [26,74]. The highest concentration of SMX (0.531 µg/L) in surface waters in China was 86.9% less than the concentration of SMX (4.072 µg/L) in surface waters Europe and was 78.1% less than the concentration of SMX (2.42 µg/L) in surface waters Brazil [2,24]. The most frequently reported watershed was the Yangtze River, where 37 samples were reported, and approximately 95% (35 out of 37) of the analyzed SMX samples were detected at concentrations above the limit of detection levels. The second frequently reported watershed was Hai River, where 31 samples were reported, and approximately 90% (28 out of 31) of the analyzed SMX samples were detected at concentrations above the limit of detection levels. It should be noted that studies in some watersheds were quite limited, for example, only two samples were reported in the Yellow River and Huai River. The uncertainty of the environmental risk assessment of SMX could be attributed to the limitations of the data, particularly for the Huai River, Songliao River, and Yellow River watersheds. More exposure data of SMX in the surface waters should be obtained in the future to explore the environmental risk assessment in China. A quantitative environmental risk assessment of SMX should be conducted in China, based on comprehensive and representative monitoring of environmental exposure concentrations.

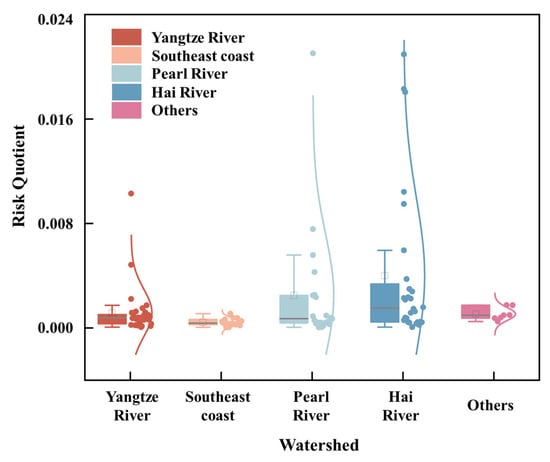

Figure 3.

The SMX concentrations (µg/L) in surface waters of China collected from peer-reviewed publications and government reports published between 2006 and 2024.

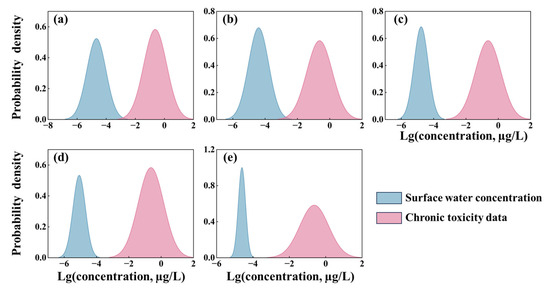

3.3.2. Quantitative Risk Assessment for SMX

The negligible risk of SMX was obtained, according to a low RQ (<0.1) and OA (<0.1) calculated with the risk quotients method and the probability area overlap method, respectively, in surface waters in China. The RQ and OA values of SMX in the surface waters ranged from 0 to 0.0225 and from 0 to 0.005 calculated for the collected exposure data in China from 2006 to 2024 (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Most RQ values were around 10−3, which accounted for 59% of all the collected exposure data of 112 in China. The distribution of RQ values were 0~0.011, 0.0001~0.0011, 0~0.0225, 0~0.0224, and 0.0005~0.0019 for the Yangtze River, Southeast coast, Pearl River, Hai River, and other watersheds, respectively (Figure 4). The value of OA was 0.003 and 0.005 for the Pearl River and Hai River watershed, respectively, while the value of OA of the Yangtze River, Southeast coast, and other watersheds were approaching 0 (Figure 5). The highest RQ value of SMX was observed in Guangzhou City (0.0225) of the Pearl River watershed, followed by the Wangyanggou River (0.0224) of the Hai River watershed, which still showed a low risk for aquatic life from SMX in the surface waters. Pearl River and Hai River have the highest potential risk from RQ and OA, which reflected its higher population density, lower precipitation, and efficient wastewater reuse system. In addition, some basins were limited sampling point, which may introduce uncertainty in the regional risk assessment. Therefore, more information on the concentrations of SMX in surface waters in China is necessary for further ecological risk assessment.

Figure 4.

The distribution of RQ based on the long-term ALFQC and the concentrations of SMX in five watersheds in China. The violin plots show data density, while the internal box plots indicate medians (horizontal lines) and means (Squares). Individual dots represent the observed data points.

Figure 5.

The ecological risk of SMX in (a) Pearl River; (b) Hai River; (c) Yangtze River; (d) Southeast coast; (e) others (including Huai River, Songliao River, Yellow River) obtained by the probability area overlap method.

4. Conclusions

A total of 15 ATV covering 10 species and 22 CTV covering 11 species were applied to establish the ALFQC for SMX in China. The most sensitive species to SMX for ATV under short-term exposure was Raphidocelis subcapitata, while the most sensitive species for CTV under long-term exposure was Lemna gibba in China. The normal and logistic distribution models were confirmed as the optimal models for deriving the short-term and long-term ALFQC, which were calculated to be 2829 µg/L and 23.63 µg/L, respectively using the SSD method. The concentration of SMX in the surface waters ranged from 0 to 0.531 µg/L, including the Hai River, Yangtze River, Southeast coast, Pearl River, and other river watersheds. The RQ and OA values of SMX in the surface waters ranged from 0 to 0.0225 and from 0 to 0.005 using the risk quotient and probability area overlap methods, which indicated that the current environmental concentrations of SMX in China posed negligible ecological risks.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18010045/s1, Table S1: Concentration data of SMX in major river watershed of China.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z.; Methodology, Z.Z.; Software, Y.F.; Validation, L.W.; Formal analysis, W.Z.; Investigation, L.W. and Y.F.; Resources, W.Z.; Writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.; Writing—review and editing, Y.F.; Visualization, W.Z.; Supervision, Y.B.; Project administration, Y.B.; Funding acquisition, Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No.2023YFC3208401).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SMX | Sulfamethoxazole |

| ALFQC | Freshwater Quality Criteria for the Protection of Aquatic Life |

| Long-term ALFQC | Long-Term Freshwater Quality Criteria for the Protection of Aquatic Life |

| Short-term ALFQC | Short-Term Freshwater Quality Criteria for the Protection of Aquatic Life |

| SSD | Species Sensitivity Distribution |

| AF | Assessment Factor |

| ATV | Acute Toxicity Values |

| CTV | Chronic Toxicity Values |

| NOEC | No Observed Effect Concentration |

| LOEC | Lowest Observed Effect Concentration |

| MATC | Maximum Acceptable Toxicant Concentration |

| SMAV | Species Mean Acute Toxicity Value |

| SMCV | Species Mean Chronic Toxicity Value |

| RQ | Risk Quotient |

| OA | Overlap Area |

References

- Yang, Y.; Song, W.; Lin, H.; Wang, W.; Du, L.; Xing, W. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in global lakes: A review and meta-analysis. Environ. Int. 2018, 116, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasannamedha, G.; Kumar, P.S. A review on contamination and removal of sulfamethoxazole from aqueous solution using cleaner techniques: Present and future perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.-V.; Chang, Y.-T.; Chao, W.-L.; Yeh, S.-L.; Kuo, D.-L.; Yang, C.-W. Effects of sulfamethoxazole and sulfamethoxazole-degrading bacteria on water quality and microbial communities in milkfish ponds. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Sun, F.; Goei, R.; Zhou, Y. Facile fabrication of RGO-WO3 composites for effective visible light photocatalytic degradation of sulfamethoxazole. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 207, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Grinten, E.; Pikkemaat, M.G.; van den Brandhof, E.-J.; Stroomberg, G.J.; Kraak, M.H.S. Comparing the sensitivity of algal, cyanobacterial and bacterial bioassays to different groups of antibiotics. Chemosphere 2010, 80, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.Y.; Liu, W.Q.; Nie, X.P.; Guan, C.; Yang, Y.F.; Wang, Z.H.; Liao, W. Growth response and toxic effects of three antibiotics on Selenastrum capricornutum evaluated by photosynthetic rate and chlorophyll biosynthesis. J. Environ. Sci. 2011, 23, 1558–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.W.; Yin, P.; Tian, L.X.; Liu, Y.J.; Tan, B.P.; Niu, J. Interactions between dietary lipid levels and chronic exposure of legal aquaculture dose of sulfamethoxazole in juvenile largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides. Aquat. Toxicol. 2020, 229, 105670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Li, H.; Yan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Fu, Z.; Liao, W.; Giesy, J.P.; Bai, Y. Technical study on national mandatory guideline for deriving water quality criteria for the protection of freshwater aquatic organisms in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 250, 109539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Xiao, S.; Naraginti, S.; Liao, W.; Feng, C.; Xu, D.; Guo, C.; Jin, X.; Xie, F. Freshwater water quality criteria for phthalate esters and recommendations for the revision of the water quality standards. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 279, 116517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Meng, W.; Zhao, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, R.; Cao, Y.; Liao, H. China embarking on development of its own national water quality criteria system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 7992–7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Feng, C.; Jin, X.; Xie, H.; Liu, N.; Bai, Y.; Wu, F.; Raimondo, S. A QSAR-ICE-SSD model prediction of the PNECs for alkylphenol substances and application in ecological risk assessment for rivers of a megacity. Environ. Int. 2022, 167, 107367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Jin, X.; Feng, C.; Wang, Z.; Wu, F.; Johnson, A.C.; Xiao, H.; Hollert, H.; Giesy, J.P. Ecological risk assessment of fifty pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in Chinese surface waters: A proposed multiple-level system. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, F.; Zuccato, E.; Davoli, E.; Fattore, E.; Castiglioni, S. Risk assessment of a mixture of emerging contaminants in surface water in a highly urbanized area in Italy. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 361, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Li, H.; Feng, C.; Liu, D.; Yan, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wu, F. A review on the water quality criteria of nonylphenol and the methodological construction for reproduction toxicity endocrine disrupting chemicals. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 260, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.X.; Wang, B.; Yuan, H.L.; Yu, G. Derivation of water quality criteria for sulfonamide antibiotics using species sensitivity distribution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 39, 184–188. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.Z.; Wang, B.; Yu, G.; Huang, J.; Deng, S.B. Water quality criteria for sulfonamide antibiotics based on QSAR and ICE models. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 38, 170–175. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Yang, Z.F.; Wang, T.; Sun, R.R.; Wang, Y.N. Ecological risk assessment and water quality criteria of fluoroquinolone antibiotics in surface waters. J. Environ. Health 2018, 35, 531–535. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Shi, T.; Wu, X.; Cao, H.; Li, X.; Hua, R.; Tang, F.; Yue, Y. The occurrence and distribution of antibiotics in Lake Chaohu, China: Seasonal variation, potential source and risk assessment. Chemosphere 2015, 122, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Wu, Q.; Liu, P.; Hu, W.; Huang, B.; Shi, B.; Zhou, Y.; Kwon, B.-O.; Choi, K.; Ryu, J.; et al. Ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in sediments and water from the coastal areas of the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, N.; Purohit, M.; Diwan, V.; Chandran, S.P.; Riggi, E.; Parashar, V.; Tamhankar, A.J.; Lundborg, C.S. Monitoring of water quality, antibiotic residues, and antibiotic-resistant escherichiacoli in the kshipra river in India over a 3-year period. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairigo, P.; Ngumba, E.; Sundberg, L.-R.; Gachanja, A.; Tuhkanen, T. Contamination of surface water and river sediments by antibiotic and antiretroviral drug cocktails in low and middle-income countries: Occurrence, risk and mitigation strategies. Water 2020, 12, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Ji, K.; Kim, C.; Kang, H.; Lee, S.; Kwon, B.; Kho, Y.; Park, K.; Kim, K.; Choi, K. Pharmaceutical residues in streams near concentrated animal feeding operations of Korea—Occurrences and associated ecological risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, Q.T.; Moreau-Guigon, E.; Labadie, P.; Alliot, F.; Teil, M.-J.; Blanchard, M.; Chevreuil, M. Occurrence of antibiotics in rural catchments. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabino, J.A.; de Sá Salomão, A.L.; de Oliveira Muniz Cunha, P.M.; Coutinho, R.; Marques, M. Occurrence of organic micropollutants in an urbanized sub-basin and ecological risk assessment. Ecotoxicology 2021, 30, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Feng, C.; Gao, M.; Wang, L. Prevalence of veterinary antibiotics and antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli in the surface water of a livestock production region in northern China. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, M.; Guo, C.; An, D.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xi, B. Distribution and ecological risk of antibiotics in a typical effluent–receiving river (Wangyang River) in north China. Chemosphere 2014, 112, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, A.; Hu, J.; Wu, X.; Peng, H.; Wu, S.; Dong, Z. Occurrence and source apportionment of sulfonamides and their metabolites in Liaodong Bay and the adjacent Liao River basin, North China. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2011, 30, 1252–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Leung, K.S.-Y.; Wong, J.W.-C.; Selvam, A. Preliminary occurrence studies of antibiotic residues in Hong Kong and Pearl River Delta. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, X.; Li, G.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Meng, Q.; Liu, R.; Li, W. The derivation of seawater quality criteria and ecological risk assessment of Tonalide. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 298, 118287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xi, X.; Yu, G.; Cao, Q.; Wang, B.; Vince, F.; Hong, Y. Pharmaceutical compounds in aquatic environment in China: Locally screening and environmental risk assessment. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2015, 9, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.-y.; Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Ge, H.; Zhang, M.; Guo, W.; Shi, J.; Li, X.-y. Development of ecological risk assessment for Diisobutyl phthalate and di-n-octyl phthalate in surface water of China based on species sensitivity distribution model. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; He, Y.; Song, K.; Xie, F.; Li, H.; Sun, F. Derivation of water quality criteria of zinc to protect aquatic life in Taihu Lake and the associated risk assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MEEC. Technical Guideline for Deriving Water Quality Criteria for Freshwater Organisms (HJ831-2022); Minisitry of Ecology and Environment of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Brain, R.A.; Johnson, D.J.; Richards, S.M.; Sanderson, H.; Sibley, P.K.; Solomon, K.R. Effects of 25 pharmaceutical compounds to Lemna gibba using a seven-day static-renewal test. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2004, 23, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Test No. 221: Lemna sp. Growth Inhibition Test, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- MEEC. Water Quality Criteria for Freshwater Aquatic Organisms-Phenol; Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Li, W.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Fan, B.; Gao, X.; Liu, Z. Development of aquatic life criteria for tonalide (AHTN) and the ecological risk assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 189, 109960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isidori, M.; Lavorgna, M.; Nardelli, A.; Pascarella, L.; Parrella, A. Toxic and genotoxic evaluation of six antibiotics on non-target organisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2005, 346, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Choi, K. Hazard assessment of commonly used agricultural antibiotics on aquatic ecosystems. Ecotoxicology 2008, 17, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.M.; Cole, S.E. A toxicity and hazard assessment of fourteen pharmaceuticals to Xenopus laevis larvae. Ecotoxicology 2006, 15, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, B.; Gagné, F.; Blaise, C. An investigation into the acute and chronic toxicity of eleven pharmaceuticals (and their solvents) found in wastewater effluent on the cnidarian, Hydra attenuata. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 389, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-H. Acute toxicity of 30 pharmaceutically active compounds to freshwater planarians, Dugesia japonica. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2013, 95, 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Jeong, D.H.; Choi, K. Environmental levels of ultraviolet light potentiate the toxicity of sulfonamide antibiotics in Daphnia magna. Ecotoxicology 2008, 17, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Li, Z.; Liu, J. Effects of selected pharmaceuticals on growth, reproduction and feeding of Daphnia magna. Fresenius Environ. 2013, 22, 2583–2589. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, K.; Jung, J.; Park, S.; Kim, P.-G.; Park, J. Aquatic toxicity of acetaminophen, carbamazepine, cimetidine, diltiazem and six major sulfonamides, and their potential ecological risks in Korea. Environ. Int. 2007, 33, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brain, R.A.; Ramirez, A.J.; Fulton, B.A.; Chambliss, C.K.; Brooks, B.W. Herbicidal effects of sulfamethoxazole in Lemna gibba: Using p-aminobenzoic acid as a biomarker of effect. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 8965–8970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madureira, T.V.; Rocha, M.J.; Cruzeiro, C.; Rodrigues, I.; Monteiro, R.A.F.; Rocha, E. The toxicity potential of pharmaceuticals found in the Douro River estuary (Portugal): Evaluation of impacts on fish liver, by histopathology, stereology, vitellogenin and CYP1A immunohistochemistry, after sub-acute exposures of the zebrafish model. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2012, 34, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, K.; Nagase, H.; Ozawa, M.; Endoh, Y.S.; Goto, K.; Hirata, K.; Miyamoto, K.; Yoshimura, H. Evaluation of antimicrobial agents for veterinary use in the ecotoxicity test using microalgae. Chemosphere 2004, 57, 1733–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.H.; Ying, G.G.; Su, H.C.; Stauber, J.L.; Adams, M.S.; Binet, M.T. Growth-inhibiting effects of 12 antibacterial agents and their mixtures on the freshwater microalga Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008, 27, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialk-Bielinska, A.; Stolte, S.; Arning, J.; Uebers, U.; Böschen, A.; Stepnowski, P.; Matzke, M. Ecotoxicity evaluation of selected sulfonamides. Chemosphere 2011, 85, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, W.; Sochacka, J.; Wardas, W. Toxicity and biodegradability of sulfonamides and products of their photocatalytic degradation in aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 1295–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, J.O. Aquatic environmental risk assessment for human use of the old antibiotic sulfamethoxazole in Europe. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016, 35, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Huang, X.; Witter, J.D.; Spongberg, A.L.; Wang, K.; Wang, D.; Liu, J. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals and personal care products and associated environmental risks in the central and lower Yangtze river, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014, 106, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Meyer, M.T.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, H.; Chen, J.-a.; Qiu, Z.; Yang, L.; Cao, J.; Shu, W. Determination of antibiotics in sewage from hospitals, nursery and slaughter house, wastewater treatment plant and source water in Chongqing region of Three Gorge Reservoir in China. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 1444–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Zi, C.F.; Zhang, Y.X.; Gan, X.M.; Peng, X.Y.; Gao, X.; Guo, J.-S. Pollution level and ecological risk assessment of typical pharmaceutically active compounds in the river basins of main districts of Chongqing. Res. Environ. Sci. 2013, 26, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.; Jiang, L.; Han, Q.; Xue, J.Y.; Ye, H.; Cao, G.M.; Lin, K.F.; Cui, C.Z. Distribution characteristics and health risk assessment of thirteen sulfonamides antibiotics in a drinking water source in East China. Environ. Sci. 2016, 37, 2515–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Hu, X.; Yin, D.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Z. Occurrence, distribution and seasonal variation of antibiotics in the Huangpu River, Shanghai, China. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wu, M.; Wang, H.; Xu, G. Antibiotics in the surface water of Shanghai, China: Screening, distribution, and indicator selecting. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 9836–9848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Shang, J.; Shen, Z.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Peng, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, R.; et al. Distribution and risk characteristics of antibiotics in China surface water from 2013 to 2024. Chemosphere 2025, 375, 144197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, M. Occurrence of antibiotics in the aquatic environment of Jianghan Plain, central China. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 497–498, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Wang, Y.; Tong, L.; Deng, Y.; Li, Y.; Gan, Y.; Guo, W.; Dong, C.; Duan, Y.; Zhao, K. Occurrence and risk assessment of antibiotics in surface water and groundwater from different depths of aquifers: A case study at Jianghan Plain, central China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 135, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.J.; Cao, S.; Mu, S. Characteristics of concentrations of antibiotics in typical drinking water sources in a city in Jiangsu Province. Water Resour. Prot. 2016, 32, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Xu, L.; Hu, Q.; Zeng, X.; Yu, Z. Occurrence, spatiotemporal distribution and potential ecological risks of antibiotics in Dongting Lake, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhou, J.L.; Zhao, H.; Hou, L.; Yang, Y. Application of passive sampling in assessing the occurrence and risk of antibiotics and endocrine disrupting chemicals in the Yangtze Estuary, China. Chemosphere 2014, 111, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Liu, M.; Nie, M.; Shi, H.; Gu, L. Antibiotics in the surface water of the Yangtze Estuary: Occurrence, distribution and risk assessment. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 175, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Cao, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Xu, J. Seasonal variation, flux estimation, and source analysis of dissolved emerging organic contaminants in the Yangtze Estuary, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 125, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Chen, H.; Li, J. Sources, distribution and potential risks of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in Qingshan Lake basin, Eastern China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 96, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, S.; Geng, C.; Zhang, X. Occurrence and sources of antibiotics and their metabolites in river water, WWTPs, and swine wastewater in Jiulongjiang River basin, south China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 9075–9083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, D.; Chen, B.; Bai, R.; Song, P.; Lin, H. Contamination of sulfonamide antibiotics and sulfamethazine-resistant bacteria in the downstream and estuarine areas of Jiulong River in Southeast China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 12104–12113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lin, L.; Luo, Z.; Yan, C.; Zhang, X. Occurrence of selected antibiotics in Jiulongjiang River in various seasons, South China. J. Environ. Monit. 2011, 13, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Qiu, X.; Chen, B.; Yu, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, G.; Li, H.; Chen, M.; Sun, G.; Huang, H.; et al. Antibiotics pollution in Jiulong River estuary: Source, distribution and bacterial resistance. Chemosphere 2011, 84, 1677–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, G.; Tang, J.; Xu, W.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Zou, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, X.-D. Levels, spatial distribution and sources of selected antibiotics in the East River (Dongjiang), South China. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2012, 15, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhou, K.; Sun, X.-L.; Zhao, L.-R.; Zhang, Y.-B. Occurrence and distribution of the environmental pollutant antibiotics in Gaoqiao mangrove area, China. Chemosphere 2016, 147, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.X.; Chen, Q.; Lei, M. Simultaneous determination of trace antibiotics in surface water by isotope-diluted high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Environ. Chem. 2016, 35, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.F.; Ying, G.G.; Zhao, J.L.; Tao, R.; Su, H.C.; Liu, Y.S. Spatial and seasonal distribution of selected antibiotics in surface waters of the Pearl Rivers, China. J. Environ. Sci. Health B 2011, 46, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.; Li, N.; Zheng, H.; Lin, H. Occurrence and risk assessment of antibiotics in river water in Hong Kong. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 125, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, B.; Yang, W.W.; Wang, Y.H.; Huang, W.; Li, P.; Zhang, R.J.; Huang, K. Occurrence, distribution and ecological risks of sulfonamides in the Qinzhou Bay, South China. Environ Sci. 2013, 33, 1664–1669. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. Occurrence and health risk assessment of antibiotics in drinking water of a city in Southern China. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 657, 012048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, G. Antibiotic contamination in a typical developing city in south China: Occurrence and ecological risks in the Yongjiang River impacted by tributary discharge and anthropogenic activities. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 92, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, T.B.; Leung, H.W.; Loi, I.H.; Chan, W.H.; So, M.K.; Mao, J.Q.; Choi, D.; Lam, J.C.W.; Zheng, G.; Martin, M.; et al. Antibiotics in the Hong Kong metropolitan area: Ubiquitous distribution and fate in Victoria Harbour. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 58, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shi, Y.; Gao, L.; Liu, J.; Cai, Y. Occurrence of antibiotics in water, sediments, aquatic plants, and animals from Baiyangdian Lake in North China. Chemosphere 2012, 89, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikaros, A.G.; Chrysikopoulos, C.V. Occurrence and distribution of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) detected in lakes around the world—A review. Environ. Adv. 2021, 6, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Xu, W.; Zhang, R.; Tang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G. Occurrence and distribution of antibiotics in coastal water of the Bohai Bay, China: Impacts of river discharge and aquaculture activities. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 2913–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xu, L.; Rysz, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Occurrence and transport of tetracycline, sulfonamide, quinolone, and macrolide antibiotics in the Haihe River Basin, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 1827–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.H.; Cao, Y.; Li, Q.; Meng, T.; Zhang, S. Pollution characteristics and ecological risk assessment of typical antibiotics in environmental media in China. Environ. Sci. 2023, 44, 6894–6908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Gao, L.; Shi, Y.; Liu, J.; Cai, Y. Occurrence, distribution and risks of antibiotics in urban surface water in Beijing, China. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2015, 17, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, G.; Zheng, Q.; Tang, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, W.; Zou, Y.; Chen, X. Occurrence and risks of antibiotics in the Laizhou Bay, China: Impacts of river discharge. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2012, 80, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Guo, Z.; Hua, X. Antibiotics in water and sediments from Liao River in Jilin province, China: Occurrence, distribution, and risk assessment. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, G.; Zou, S.; Ling, Z.; Wang, G.; Yan, W. A preliminary investigation on the occurrence and distribution of antibiotics in the Yellow River and its tributaries, China. Water Environ. Res. 2009, 81, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.