Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Parallel Stacked Structure Signals in VLF Electric Field Observations from CSES-01 Satellite

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data Sources and Signal Structure Characteristics

3. Feature Analysis

4. Influence of Geomagnetic and Solar Activity

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (1)

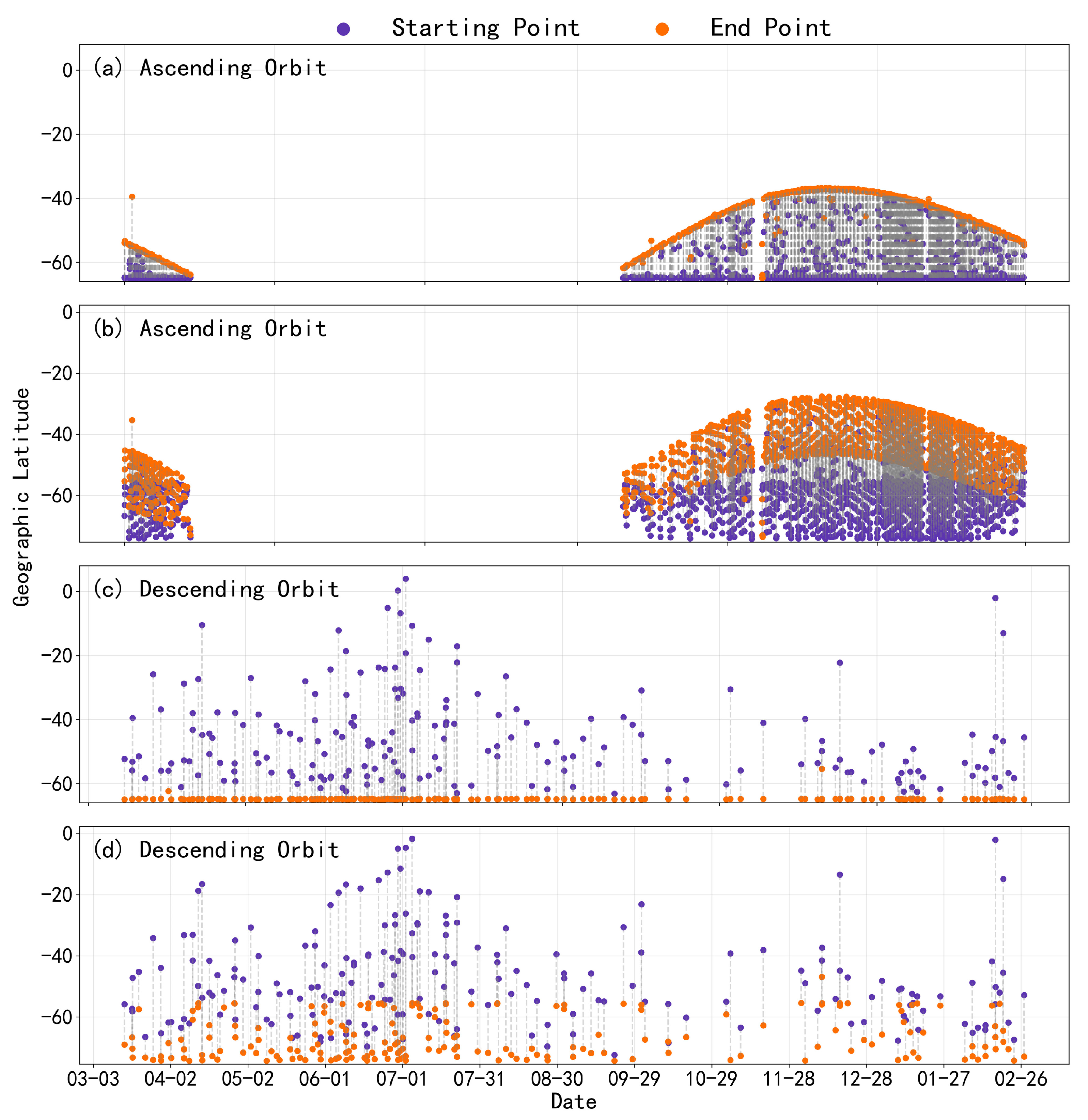

- Among 10,361 valid half-orbit datasets, 1465 images (14.14%) exhibited parallel stacked structure signals. These signals occurred predominantly during ascending (nightside) orbits (86.4%), indicating a clear day–night asymmetry.

- (2)

- Spatially, the signals were concentrated in the mid- to high-latitude regions of the Southern Hemisphere (40°S–65°S), mainly over the southern tip of South America, the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans, and the southern waters near Australia.

- (3)

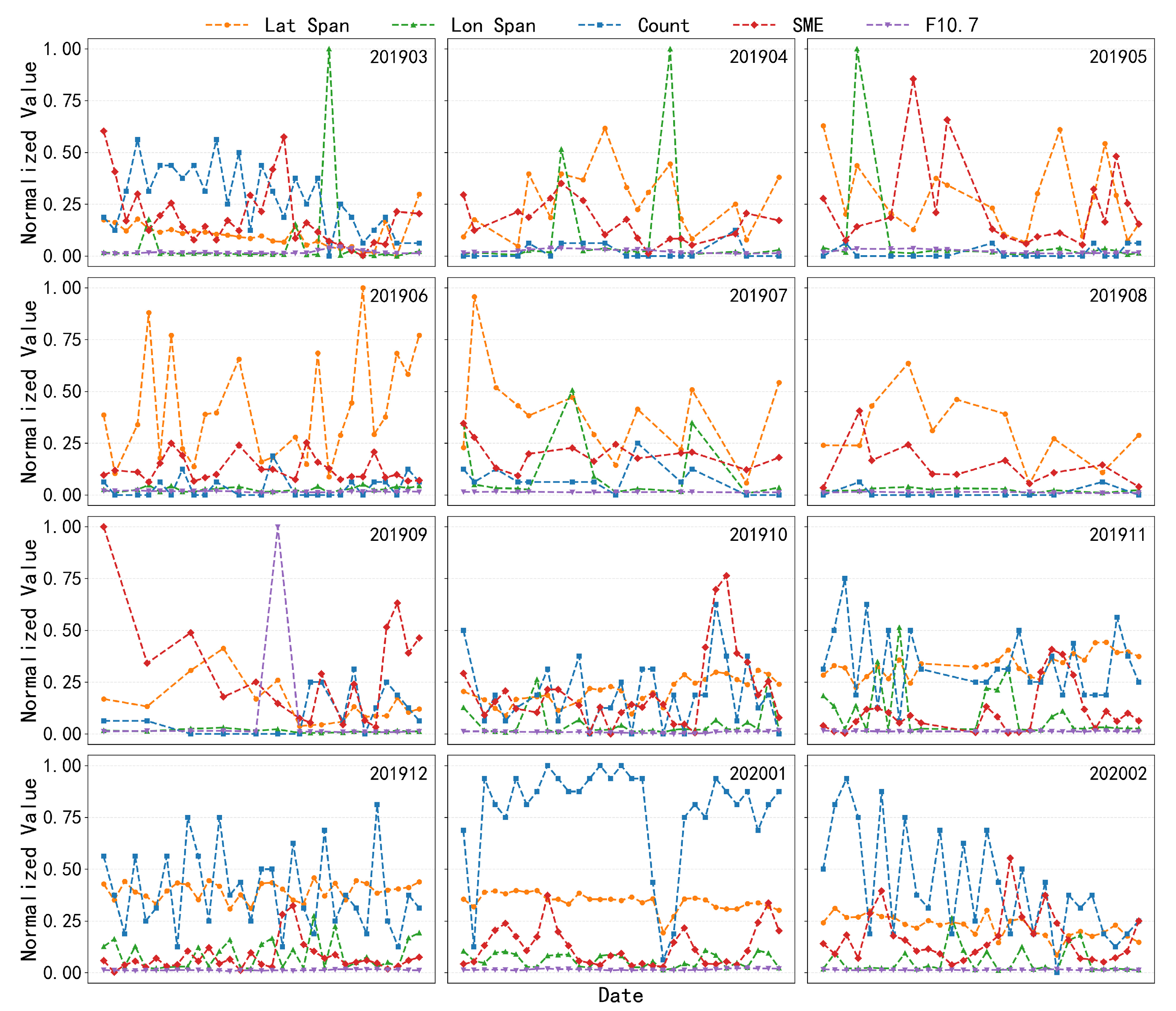

- The signals showed pronounced seasonal variation, with the highest frequency in winter (December–February) and autumn (September–November), and the lowest in summer (June–August), consistent to some extent with seasonal geomagnetic activity patterns.

- (4)

- Temporal comparisons with geophysical indices revealed partial correlation between signal occurrence and the SME index in specific months (e.g., March and November), while the F10.7 solar activity index showed no significant relationship with either the frequency or spatial distribution of the signals.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pulinets, S.; Ouzounov, D. Lithosphere–Atmosphere–Ionosphere Coupling (Laic) Model—An Unified Concept for Earthquake Precursors Validation. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2011, 41, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, A.; Marchetti, D.; Pavón-Carrasco, F.J.; Cianchini, G.; Perrone, L.; Abbattista, C.; Alfonsi, L.; Amoruso, L.; Campuzano, S.A.; Carbone, M.; et al. Precursory Worldwide Signatures of Earthquake Occurrences on Swarm Satellite Data. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Chen, Z.; Shen, X.; Zeren, Z. Investigation of Vlf Transmitter Signals in the Ionosphere by Zh-1 Observations and Full-Wave Simulation. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2019, 124, 4697–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, B.; Hua, M.; Gu, X.; Fu, S.; Xiang, Z.; Cao, X.; Ma, X. Artificial Modification of Earth’s Radiation Belts by Ground-Based Very-Low-Frequency (Vlf) Transmitters. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2022, 65, 391–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H. Power Spectra of Random Heterogeneities in the Solid Earth. Solid Earth 2019, 10, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Emoto, K. Propagation of a Vector Wavelet through Von Kármán-Type Random Elastic Media: Monte Carlo Simulation by Using the Spectrum Division Method. Geophys. J. Int. 2023, 234, 1655–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganefianto, G.; Nakahara, H.; Nishimura, T. Scattering Strength at Active Volcanoes in Japan as Inferred from the Peak Ratio Analysis of Teleseismic P Waves. Earth Planets Space 2021, 73, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, M.; Guo, Y.; Qian, G.; Liu, J.; Yuan, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhai, L.; et al. Spatio–Temporal Evolution of Electric Field, Magnetic Field and Thermal Infrared Remote Sensing Associated with the 2021 Mw7.3 Maduo Earthquake in China. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manglik, A.; Suresh, M.; Babu, M.D.; Pavankumar, G. Pre- and Coseismic Electromagnetic Signals of the Nepal Earthquake of 03 November 2023. Earth Planets Space 2024, 76, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igel, J.K.H.; Klaasen, S.; Noe, S.; Nomikou, P.; Karantzalos, K.; Fichtner, A. Challenges in Submarine Fiber-Optic Earthquake Monitoring. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2024, 129, e2024JB029556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeren, Z.; Hu, Y.; Piersanti, M.; Shen, X.; De Santis, A.; Yan, R.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q. The Seismic Electromagnetic Emissions during the 2010 Mw 7.8 Northern Sumatra Earthquake Revealed by Demeter Satellite. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 8, 572393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhima, Z.; Parrot, M. Spectral Broadening of Nwc Transmitter Signals in the Ionosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL088103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catania, M.; Figlioli, A.; Vitale, G.; D’aLessandro, A. Seismic Noise Characterization of Broad-Band Stations in the Italian Region Using Power Spectral Density: A Frequency, Spatial and Statistical Analysis. Geophys. J. Int. 2025, 242, ggaf168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Zeren, Z.; Yang, D.; Sun, X.; Lü, F.; Ran, Z.; Shen, X. Lightweight Automatic Detection Model for Lightning Whistle Waves Based on Improved Yolov5. Chin. J. Space Sci. 2024, 44, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Feng, J.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Q.; Yang, D.; Zeren, Z.; Shen, X. Diffusion State Recognition Algorithm for Lightning Whistler Waves of China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite. Prog. Geophys. 2022, 37, 541–550. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, Q.; Yang, D.; Liu, Q.; Zhima, Z.; Shen, X. Automatic Recognition Algorithm of Lightning Whistlers Observed by the Search Coil Magnetometer Onboard the Zhangheng-1 Satellite. Chin. J. Geophys. 2021, 64, 3905–3924. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, Z.; Zeren, Z.; Wang, Z.; Feng, J.; Shen, X.; Wu, P.; Wang, Q.; Yang, D.; Wang, T. Automatic Recognition Algorithm of the Lightning Whistler Waves by Using Speech Processing Technology. Chin. J. Geophys. 2022, 65, 882–897. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Liu, Q.; Huang, J.; Li, Z.; Yan, R.; Yuan, J.; Shen, X.; Xing, L.; Pang, G. Automatic Extraction of Vlf Constant-Frequency Electromagnetic Wave Frequency Based on an Improved Vgg16-Unet. Radio Sci. 2024, 59, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Z.; Lu, C.; Hu, Y.; Yang, D.; Sun, X.; Zhima, Z. Automatic Detection of Quasi-Periodic Emissions from Satellite Observations by Using Detr Method. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, P.; Nĕmec, F.; Santolík, O. Statistical Analysis of Vlf Radio Emissions Triggered by Power Line Harmonic Radiation and Observed by the Low-Altitude Satellite Demeter. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2014, 119, 5744–5754. [Google Scholar]

- Parrot, M.; Němec, F.; Cohen, M.B.; Gołkowski, M. On the Use of Elf/Vlf Emissions Triggered by Haarp to Simulate Plhr and to Study Associated Mlr Events. Earth Planets Space 2022, 74, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yue, C.; Xie, L. Conjugate Observations of Power Line Harmonic Radiation Onboard Demeter. Earth Planets Space 2023, 75, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, S.; Wang, L.; Cao, J.; Huang, J.; Zhu, X.; Piergiorgio, P.; Dai, J. The State-of-the-Art of the China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite Mission. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2018, 61, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zong, Q.-G.; Zhang, X. Introduction to Special Section on the China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite and Initial Results. Earth Planet. Phys. 2018, 2, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignalberi, A.; Pezzopane, M.; Coco, I.; Piersanti, M.; Giannattasio, F.; De Michelis, P.; Tozzi, R.; Consolini, G. Inter-Calibration and Statistical Validation of Topside Ionosphere Electron Density Observations Made by Cses-01 Mission. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spogli, L.; Sabbagh, D.; Regi, M.; Cesaroni, C.; Perrone, L.; Alfonsi, L.; Di Mauro, D.; Lepidi, S.; Campuzano, S.A.; Marchetti, D.; et al. Ionospheric Response over Brazil to the August 2018 Geomagnetic Storm as Probed by Cses-01 and Swarm Satellites and by Local Ground-Based Observations. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2021, 126, e2020JA028368. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gou, X.; Cheng, B.; Wang, J.; Li, L. Magnetic Field Data Processing Methods of the China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite. Earth Planet. Phys. 2018, 2, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L.; Picozza, P.; Sotgiu, A. A Critical Review of Ground Based Observations of Earthquake Precursors. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 676766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lei, J.; Li, S.; Zeren, Z.; Li, C.; Zhu, X.; Yu, W. The Electric Field Detector (Efd) Onboard the Zh-1 Satellite and First Observational Results. Earth Planet. Phys. 2018, 2, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diego, P.; Bertello, I.; Candidi, M.; Mura, A.; Vannaroni, G.; Badoni, D. Plasma and Fields Evaluation at the Chinese Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite for Electric Field Detector Measurements. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 3824–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diego, P.; Bertello, I.; Candidi, M.; Mura, A.; Coco, I.; Vannaroni, G.; Ubertini, P.; Badoni, D. Electric Field Computation Analysis for the Electric Field Detector (Efd) on Board the China Seismic-Electromagnetic Satellite (Cses). Adv. Space Res. 2017, 60, 2206–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, J.; Yang, X.; Li, W.; Huo, Y.; Song, J.; Yang, R. Detection Method and Application of Nuclear-Shaped Anomaly Areas in Spatial Electric Field Power Spectrum Images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonsi, L.; Ambroglini, F.; Ambrosi, G.; Ammendola, R.; Assante, D.; Badoni, D.; Belyaev, V.A.; Burger, W.J.; Cafagna, A.; Cipollone, P.; et al. The Hepd Particle Detector and the Efd Electric Field Detector for the Cses Satellite. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2017, 137, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjerloev, J.W. The Supermag Data Processing Technique. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Kang, G.; Gao, G.; Sun, Y. Wavelet Analysis of Geomagnetic Activity Index and Solar Activity. J. Yunnan Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2014, 36, 524–529. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Cui, R.; Weng, L. Seasonal Variations of Global Ionospheric N M F 2 and H M F 2. Chin. J. Space Sci. 2024, 44, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.; Peng, J.; Zhao, K.; Ding, L.; Rushi, L.A.N. The Geomagnetic Activity and Seasonal Variations of Upward Ions in the Polar Ionosphere: A Statistical Analysis. Trans. Atmos. Sci 2017, 40, 132–137. [Google Scholar]

| Type | Characteristic | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Layered structure | This type of image has multiple regular parallel high-energy stripes, presenting a highly ordered layered structure. | Figure 3a |

| Triangular extended layered structure | This type of image maintains the parallel structure of the subject while significantly triangulating the starting and ending points of its layered structure. | Figure 3b |

| Rope like structure | The parallel overlapping stripes of this type of image present a rope like shape with a certain degree of curvature, and the rope like regions often have higher energy compared to other layered regions. | Figure 3c |

| Thick layered structure | The layered structure of this type of image has thick stripes, but this phenomenon is not common in statistics. | Figure 3d |

| Composite parallel stacked structure | This structure combines four other morphological features, with regular parallel stripes as the main body, and features such as overlapping triangulated extensions or wide layer stripes appearing locally. | Figure 3e |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hao, B.; Huang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, K.; Li, W. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Parallel Stacked Structure Signals in VLF Electric Field Observations from CSES-01 Satellite. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1198. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16101198

Hao B, Huang J, Li Z, Zhu K, Zhang Y, Pan K, Li W. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Parallel Stacked Structure Signals in VLF Electric Field Observations from CSES-01 Satellite. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(10):1198. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16101198

Chicago/Turabian StyleHao, Bo, Jianping Huang, Zhong Li, Kexin Zhu, Yuanjing Zhang, Kexin Pan, and Wenjing Li. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Parallel Stacked Structure Signals in VLF Electric Field Observations from CSES-01 Satellite" Atmosphere 16, no. 10: 1198. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16101198

APA StyleHao, B., Huang, J., Li, Z., Zhu, K., Zhang, Y., Pan, K., & Li, W. (2025). Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Parallel Stacked Structure Signals in VLF Electric Field Observations from CSES-01 Satellite. Atmosphere, 16(10), 1198. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16101198