Abstract

Erwinia amylovora, the causal agent of fire blight disease of apples and pears, is one of the most important plant bacterial pathogens with worldwide economic significance. Recent reports on the complete or draft genome sequences of four species in the genus Erwinia, including E. amylovora, E. pyrifoliae, E. tasmaniensis, and E. billingiae, have provided us near complete genetic information about this pathogen and its closely-related species. This review describes in silico subtractive hybridization-based comparative genomic analyses of eight genomes currently available, and highlights what we have learned from these comparative analyses, as well as genetic and functional genomic studies. Sequence analyses reinforce the assumption that E. amylovora is a relatively homogeneous species and support the current classification scheme of E. amylovora and its related species. The potential evolutionary origin of these Erwinia species is also proposed. The current understanding of the pathogen, its virulence mechanism and host specificity from genome sequencing data is summarized. Future research directions are also suggested.1. Introduction

Fire blight, caused by the gram-negative bacterium Erwinia amylovora, is the first plant bacterial disease confirmed back in the 1880s and is a devastating necrotic disease affecting apples, pears and other rosaceous plants [1]. Currently, the disease is widespread across North America, Europe and the Middle East including Iran, threatening the native origin of apple germplasm resources in Central Asia. Although more than two centuries have passed and significant progress has been made in revealing the mysteries of the pathogen and the disease, many questions remain unanswered. Most notable ones are questions regarding the pathogen, its ability to cause disease, and interaction with host plants and insect vectors. Why natural isolates of E. amylovora display differential virulence? What are the molecular mechanisms underlying the host specificity of Erwinia strains, as some have wide host range, whereas others with limited host range? What are the genetic differences between them? In this review, we summarize the current understanding of pathogen from genome sequencing efforts in four Erwinia species, and highlight what we have learned from comparative genomic analyses, as well as genetic and functional genomic studies. Future perspectives on research for this important pathogen are also suggested.

2. Erwinia amylovora and Related Erwinia Species

As a member of the Enterobacteriaceae, E. amylovora is a gram negative rod-shaped bacterium, which is related to many important human and animal pathogens such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, Shigella flexerni, and Yersinia pestis. E. amylovora is capable of infecting various hosts within the family of Rosaceae including subfamily Spiraeoideae. However, some Erwinia strains are host-specific, which can only infect Rubus plants within the subfamily of Rosoideae. Furthermore, differential virulence among strains isolated from Spiraeoideae has been demonstrated on different apple cultivars [2,3]. These observations and earlier genetic studies have divided E. amylovora strains into three major groups with different host range; i.e., strains isolated from Spiraeoideae, from Rosoideae (Rubus spp.), and from Asian pear (a new species E. pyrifoliae). E. pyrifoliae, the causal agent of bacterial shoot blight disease of Asian pears, is only reported in Japan and South Korea [4]. In Spain, another species E. piriflorinigrans has been confirmed to cause necrosis of pear blossoms [5]. Other related Erwinia species are E. tasmaniensis and E. billingiae, both saprophytic microorganisms isolated from apple blossoms in Australia and trees in UK, respectively [6,7]. Knowledge of new Erwinia species has brought new challenges for management of fire blight disease, especially for international trade regulation, which has been greatly hindered due to insufficient information regarding E. amylovora and related Erwinia species.

This situation could change greatly as we find out more about the genetic composition of these microorganisms. Currently, genomes of four species from the genus Erwinia, including three E. amylovora strains, three E. pyrifoliae strains (two from Korean and one from Japan), and one E. tasmaniensis and E. billingiae strain each, have been sequenced and published [6-12] (Table 1). These genome sequences might have provided us near complete genetic information about E. amylovora and its closely-related species. Comparative genomic studies thus could be conducted to determine the relatedness and evolution of genes/proteins within the genomes of these closely related Erwinia species.

| Strains[Reference] | Size (Mb) | G+C content | Total proteins | Plasmid #s | Host | Sequencing methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. amylovora CFBP1430 [11] | 3.81 | 53.6 | 3706 | 1 | Crataegus | Illumina |

| E. amylovora ATCC 49946 [10] | 3.81 | 53.6 | 3565 | 2 | Apple | Sanger |

| E. amylovora BAA2158 [9] | 3.81 | 53.6 | 3857 | 3 | Blackberry | 454 |

| E. pyrifoliae 1/96 [6] | 4.03 | 53.4 | 3697 | 4 | Asian pear | 454/Sanger |

| E. pyrifoliae DSM 12163 [12] | 4.03 | 53.4 | 4038 | 4 | Asian pear | 454/Illumina |

| E. pyrifoliae Ejp617 [8] | 3.91 | 53.6 | 3672 | 5 | Asian pear | 454 |

| E. tasmaniensis Et1/99 [7] | 3.88 | 53.7 | 3622 | 5 | Apple flower | Sanger |

| E. billingiae Eb661 [6] | 5.1 | 55.2 | 4917 | 2 | Tree | 454/Sanger |

3. Comparative Genomics of Erwinia amylovora and Related Erwinia Species

The genomes of E. amylovora and its related species range from 3.8 to 5.1 Mbp (Table 1), with E. amylovora contains the smallest genome compared to other enterobacteria sequenced so far (up to 5.5 Mbp) [13]. A comparison of genomes of E. amylovora strains CFBP1430 (isolated from Crataegus in France) and ATCC 49946 (also called Ea273, an apple isolate from New York) shows that the two genomes share more than 99.99% identity at the nucleotide level, indicating that E. amylovora is a relatively homogeneous species as indicated previously [11,14]. However, due to annotation differences, the total predicted proteins in ATCC 49946 and CFBP1430 are 3565 and 3706, respectively, without considering that the latter does not contain the pEA72 plasmid [9,11]. The genomes of the two E. pyrifoliae strains from Korea (Ep1/96 and DSM 12163 (Ep16/99) are almost identical [14]. The same problem exists with genome annotation for E. pyrifoliae strains, in which 3697 and 4038 proteins in Ep1/96 and DSM 12163, respectively, are predicted [6,12]. In order to simplify our comparison, discussion described below is mostly based on annotations of CFBP1430 and DSM 12163 genomic data except otherwise mentioned.

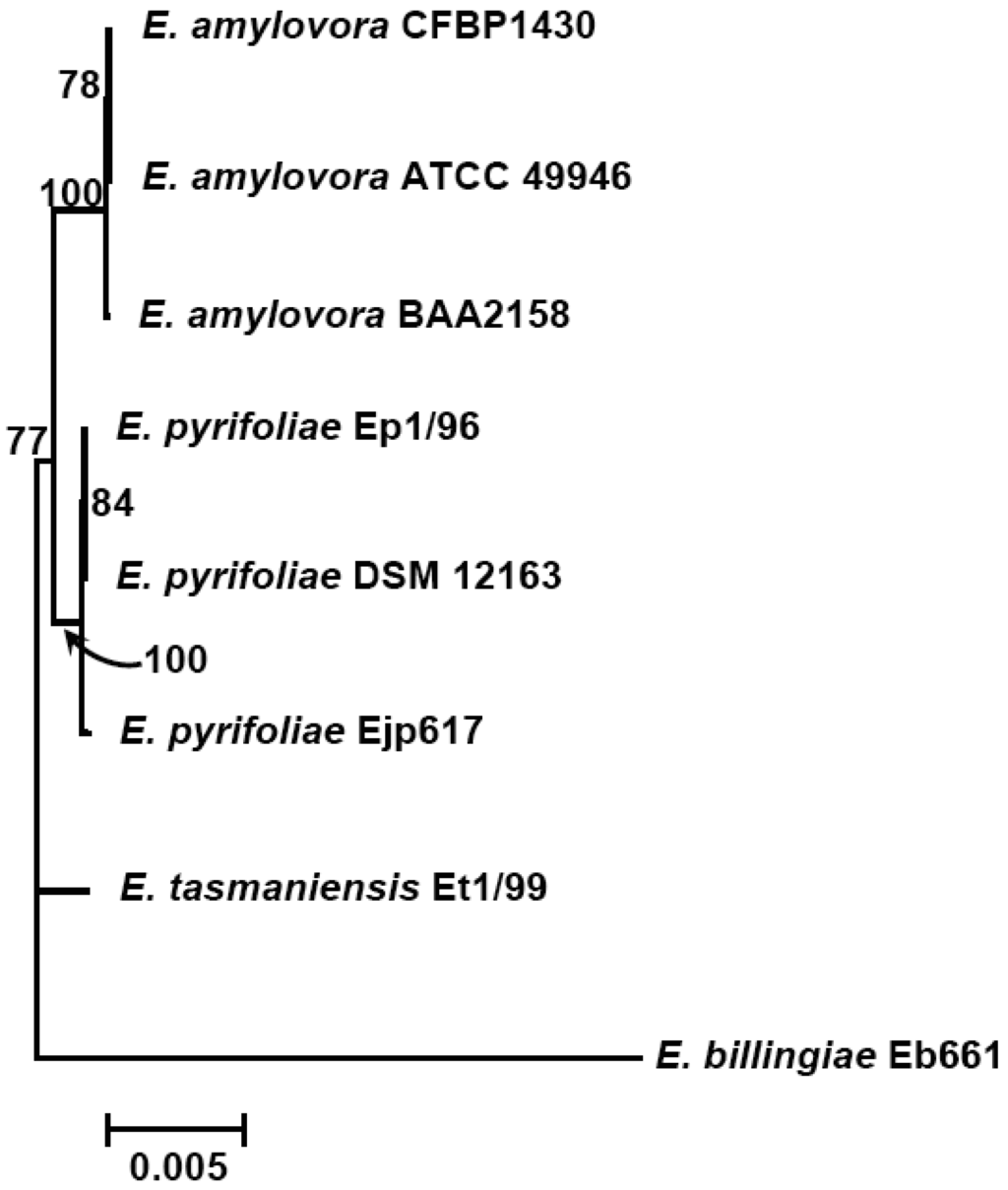

The subtractive hybridization-based mGenomeSubtractor program is used to run BLAST searches of the reference genome against one or multiple bacterial genomes as reported recently for in silico comparative genomic analyses [15,16]. Table 2 shows the numbers of specific and conserved proteins for each Erwinia genome against five others. Specific and conserved proteins are arbitrarily defined for those proteins with homology (H) value less than 0.42 and more than 0.81, respectively [15,16]. The most significant conclusion from this table is that the number of conserved proteins is around 2100, no matter which genome as reference, indicating these 2100 proteins may represent the “core” proteins of E. amylovora and related Erwinia species. In contrast, the specific proteins vary among genomes, indicating these proteins are unique ones for each genome. A phylogenetic tree reflecting their potential evolutionary relationship is thus generated using conserved housekeeping proteins (Figure 1).

| Genome compared to five genomes | Total proteins | Specific proteins | Conserved proteins | Intermediate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. amylovora CFBP1430 | 3706 | 147 | 2122 | 1437 |

| E. amylovora ATCC 49946 | 3565 | 268 | 2124 | 1173 |

| E. amylovora BAA2158 | 3857 | 217 | 2122 | 1518 |

| E. pyrifoliae DSM 12163 | 4038 | 502 | 2149 | 1387 |

| E. pyrifoliae 1/96 | 3697 | 282 | 2153 | 1262 |

| E. pyrifoliae Ejp617 | 3672 | 204 | 2145 | 1323 |

| E. tasmaniensis Et1/99 | 3622 | 588 | 2108 | 926 |

| E. billingiae Eb661 | 4917 | 1954 | 2072 | 891 |

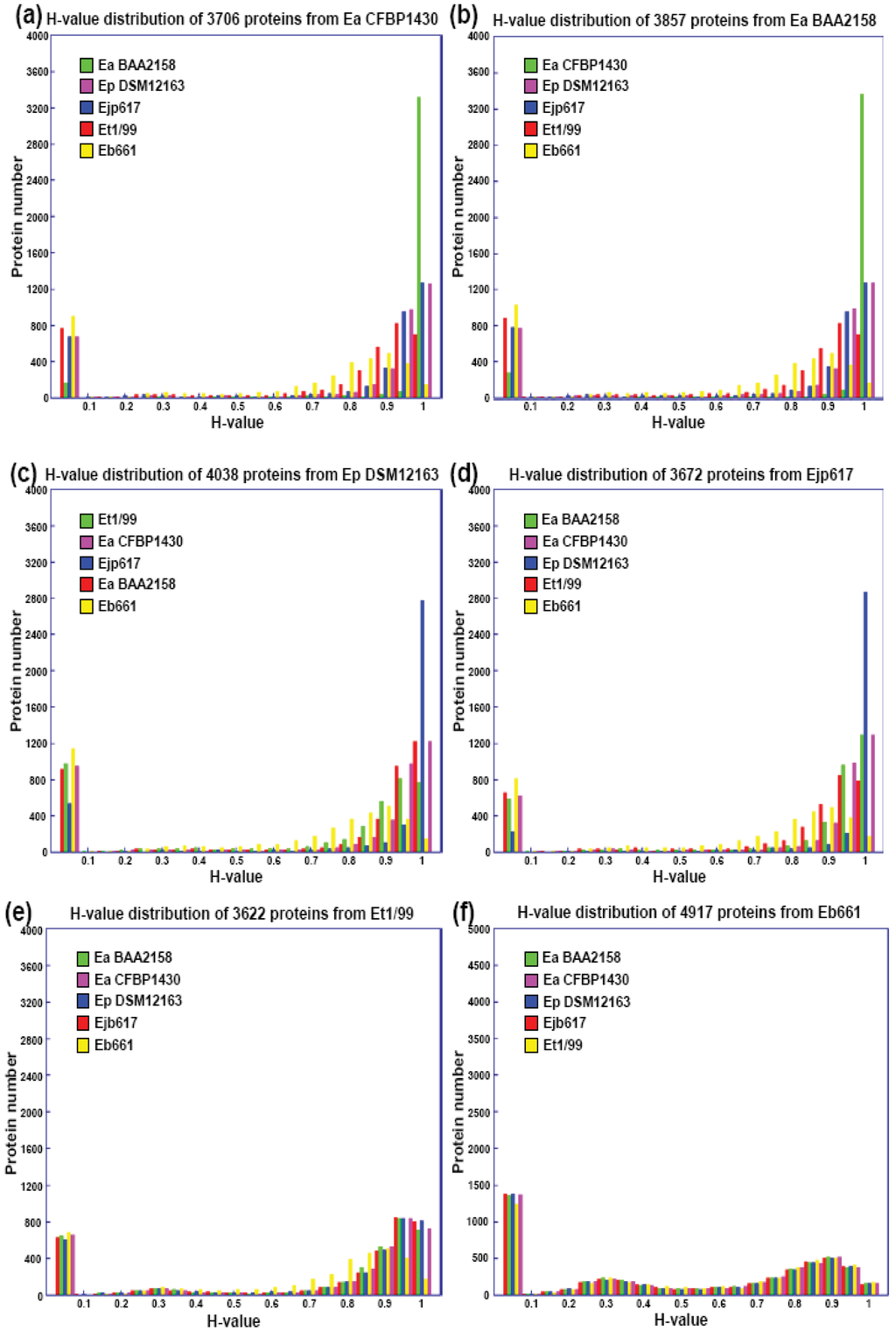

Further analyses indicate that the majority of conserved proteins in Erwinia species have H-values of more than 0.85, except E. billingae, which representing the core proteins among them and suggesting erwinias are evolutionally conserved (Figures 1 and 2). On the other hand, the majority of specific proteins in erwinias have H-values of less than 0.1, except E. billingae (Figure 2). Interestingly, when compared E. amylovora strains CFBP1430 or ATCC 49946 to BAA2158, a strain with limited host Rubus, more than 3400 of 3500 conserved proteins (98%) have H-values of 1 (Figure 2(a,b), Table 3), indicating the genomes of E. amylovora strains are almost identical, no matter their host range or geographic origin. These results further indicate that not much has been changed for genomes of E. amylovora except several recombination events [11] since the disease spread from North America to Europe about sixty years ago [1]. A similar conclusion could also be drawn for strains of E. pyrifoliae from Japan and Korea, in which about 85% conserved proteins (2800 out of 3300) have H-values of 1 (Figure 2 (c,d), Table 3). When compared E. amylovora strains with those of E. pyrifoliae strains, they share about 2800 conserved proteins (Table 3). However, the number of proteins with H-values of 1 drops dramatically to around 1200 (Figure 2), indicating diversification occurs for these two pathogenic species and suggesting these two species may be evolutionally derived from two separate sources, one in North America and the other in Asia (Figure 1). On the other hand, these results reinforce the assumption that E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae are both relatively homogeneous species and further support the current classification scheme of E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae as separate species, though they cause similar disease.

In contrast, the two saprophytic Erwinia species are distantly related to those pathogenic species (Figure 1), as indicated by the number of conserved proteins and the conservativeness of those proteins (Figure 2 (e,f), Table 3). Among them, E. tasmaniensis is more closely related to pathogenic Erwinia species than that of E. billingae (Figure 1). E. tasmaniensis and E. billingae share about 2600 and 2200 conserved proteins with pathogenic Erwinia species, respectively (Table 3). However, the number of proteins with H-values of 1 further drops, along with H-value below 1 increases dramatically, especially for those with H-value between 0.42 and 0.85 (Figure 2 (e,f), Table 3), indicating more diversification or changes occur in these saprophytic microorganisms and suggesting diversification may be related to its free-living life style or originated from different evolution sources than those of pathogenic ones.

On the other hand, the majority of specific proteins among Erwinia species have H-value of 0 (Figure 2), indicating these proteins are indeed unique proteins presented in the Erwinia genomes. As reported in pseudomonads [16], many specific proteins in erwinias except E. billingae are plasmid-borne, indicating that acquisition and maintenance of plasmids may represent a major mechanism for erwinias to change their genetic composition, which may represent a major mechanism of bacterial genome evolution [17].

| Comparison of genomes | Ea CFBP1430 | Ea BAA2158 | Ep DSM 12163 | Ep Ejp617 | Et Et1/99 | Eb Eb661 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | SP | CP | SP | CP | SP | CP | SP | CP | SP | CP | SP | |

| CFBP1430 | --- | --- | 3495 | 175 | 2831 | 802 | 2826 | 803 | 2678 | 910 | 2278 | 1134 |

| BAA2158 | 3526 | 297 | --- | --- | 2858 | 905 | 2851 | 910 | 2680 | 1034 | 2270 | 1274 |

| DSM 12163 | 2864 | 1086 | 2863 | 1061 | --- | --- | 3349 | 618 | 2731 | 1164 | 2293 | 1427 |

| Ejp617 | 2838 | 745 | 2842 | 722 | 3302 | 292 | --- | --- | 2706 | 832 | 2296 | 1076 |

| Et1/99 | 2648 | 879 | 2628 | 891 | 2659 | 849 | 2627 | 876 | --- | --- | 2344 | 988 |

| Eb661 | 2276 | 2253 | 2262 | 2254 | 2239 | 2283 | 2245 | 2279 | 2371 | 2125 | --- | --- |

4. Pathogenicity and Host Specificity of Erwinia amylovora: What is Known and What Remains Unknown?

E. amylovora has been developed as a model pathogen in studying plant-microbe interactions since the first cell free elicitor (HrpN, Harpin) was identified in 1992 [18,19]. The production of a functional hypersensitive response and pathogenicity (hrp)-type III secretion system (T3SS) and the exopolysaccharide amylovoran in E. amylovora are strictly required for inciting disease on host plants. Recent studies suggest that they are two major, yet separate virulence factors [20]. A T3SS island deletion mutant and an ams operon deletion mutant could complement each other in a co-inoculation experiment, indicating that a functional T3SS and the amylovoran are both necessary, but can be supplied by distinct bacterial strains outside of bacterial cells to cause disease [20].

The majority of hrp T3SS genes are encoded on the pathogenicity island 1 (PAI1). The T3SS system of E. amylovora secretes virulence effector proteins, including HrpA, HrpN, HrpW, and disease-specific protein DspE/A [21-23]. Many studies, including genome sequencing, have reached the conclusion that only five effector genes (eop1, eop3, avrRpt2Ea, dspA/E, and hopC1) exist in the genome of E. amylovora, which are subject to direct hrpL regulation, a master regulator of T3SS [23-25]. DspA/E, avrRpt2Ea, and hopC1 have been demonstrated to be induced in immature pear fruit, indicating that they may play a major role in virulence [23,25]. DspA/E, a virulence factor, is required for pathogenesis of E. amylovora [26,27]. Erwinia avrRpt2Ea exhibits homology to AvrRpt2 of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato, and is also a known virulence factor [25]; whereas hopC1 does not contribute to virulence when deleted [23]. Eop1 and Eop3 are YopJ and HopX homologs, respectively, and their role in virulence remains unknown [22,28].

Though studies in other plant pathogenic bacteria have begun to elucidate how type III effectors modulate plant susceptibility and promote bacterial growth and dissemination, effector function in Erwinia species is not well studied. Both DspE and HrpN are found to be involved in causing cell death and callose deposition in apple [29,30]. Two recent reports have identified potential host targets for DspE and HrpN [31,32], but the exact molecular mechanism is not well understood. Our recent functional genomic studies using an apple microarray may provide a first glimpse of host reaction to early pathogen infection [33], which could serve as a bridge to further understand Erwinia-host plant interaction.

Amylovoran, another major virulence factor, may function in plugging plant vascular tissues, suppressing plant basal defenses, and most importantly, in biofilm formation [34,35]. In E. amylovora, 12 amylovoran biosynthetic genes are encoded by the ams operon, which is directly regulated by the Rcs phosphorelay system [35,36]. It has been demonstrated that the RcsBCD two-component system is essential for virulence [35,37]. In addition, in vivo gene expression technology has identified several two-component systems to be induced during infection of host tissue in E. amylovora [23], and genome-wide systematic knockout experiment has demonstrated that four groups of two-component system mutants exhibit varying levels of amylovoran production in vitro [37]. These findings suggest that two-component systems in E. amylovora play a major role in regulating amylovoran production [37]. Currently, results from our functional genomic studies using whole-genome microarray have suggested that two-component systems may form a gene regulatory network governing the production of amylovoran in E. amylovora (Zhao, unpublished).

Natural isolates of E. amylovora from North America and Europe have been found to exhibit differential virulence on host apple plants [2,3]. A positive correlation between bacterial virulence on relatively susceptible genotypes, such as Golden Delicious, and the expression/production of major virulence factors such as HrpL, DspE and amylovoran in E. amylovora strains has recently been demonstrated [3]. These findings indicate that, although E. amylovora as a whole is a genetically homogeneous pathogen [14], the pathogen among Spiraeoideae strains may adapt to different hosts, thus maintaining a population capable of eliciting different levels of diseases on different host plants of varying levels of resistance. However, why some E. amylovora strains such as BBA2158 can only infect Rubus plant remains elusive. A recent study suggests that the effector Eop1 could act as a host specificity determinant [28]. Furthermore, it has been proposed that the structure of amylovoran, which is known to differ between apple and Rubus-infecting E. amylovora strains as well as E. pyrifoliae [38], may also play a role in host specificity. Indeed, several amylovoran biosynthesis genes in the ams operon are very diverse between these Erwinia strains, including amsCDE, indicating the substrate or specificity of these amylovoran biosynthetic proteins could be different [39]. Furthermore, effectors such as eop2, hopC1 and avrRpt2 are present in E. amylovora strains, but not in E. pyrifoliae strains, indicating these effectors may also contribute to host specificity of E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae. Another virulence factor in E. amylovora is the exopolysaccharide levan; however, the levansucrase gene (lsc) is absent in the genome of E. pyrifoliae strains. These direct or indirect evidences suggest that host specificity determinants may be very complex (Table 4). It is tempting to postulate that virulence factors act alone or in combination as well as interact with host factors could all contribute to this natural phenomenon.

| Traits | E. amylovora | E. pyrifoliae | E. tasmaniensis | E. billingae | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFBP 1430 | ATCC 49946 | BAA 2158 | DSM 12163 | EP 1/96 | Ejp 617 | Et1/99 | Eb661 | |

| T3SS PAI1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + (P) | - |

| T3SS PAI2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| T3SS PAI3 | + | + | + | - | - | - | + (P) | - |

| Flagella 1 (S) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Flagella2 (C) | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| Amylovoran biosynthesis * | + | + | + | + | + | + | +(E) | +(E) |

| Levansucrase (lsc) | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | - |

| Protease A (prtADEF) | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| eop2, hopC1, avrRpt2 | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| eop1 ** | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

*some genes are very diverse such as amsCDE, (E): In Et1/99 and Eb661, the amsE gene is missing, but additional genes present [6,7]; (P): partial; (S): separated; (C): clustered;**sequence diversification found in different species.

Analyses of the complete genome sequences of E. amylovora and related strains have revealed two additional non-flagellar T3SS PAIs (PAI2 and PAI3) and two flagellar T3SS systems (Fla1 and Fla2) (Table 4) [20]. Phylogenetic tree reconstructed based on the HrcV or InvA protein sequences for all copies from Erwinia species can divide the non-flagellar T3SSs into at least five groups. As expected, the PAI1 belongs to the Hrp1group, whereas PAI2 and PAI3 belong to Inv/Mxi/Spa group [40]. Interestingly, PAI2 and PAI3, which have a significantly lower G+C content, are clustered together and closely related to those of Sodalis glossinidius. In addition, phylogenetic tree is also constructed based on concatenation of 14 conserved flagellar proteins, which reveals that both Fla1 and Fla2 are clustered with enterobacteria, indicating that these flagellar systems may be originated from enterobacteria [40]. However, the Fla1 system is much closer to the phylogeny of species trees than that of Fla2, which is also closely related to those of S. glossinidius [40]. These findings suggest that PAI2, PAI3 and Fla2 may be acquired from a similar source by horizontal gene transfer.

Genetic analyses indicate that both PAI2 and PAI3 appear non-functional in the virulence of E. amylovora [20], however, genes on the two PAIs are expressed in rich medium [41], which is unique to plant pathogens, indicating that the two PAIs may play a role during interaction with other hosts such as insects. Comparative genomic analyses with other related Erwinia species indicate that most T3SSs are present in E. pyrifoliae and E. tasmaniensis, with the exception of PAI3 and Fla2, but not in E. billingae (Table 4). Determining the function of these additional islands in E. amylovora may provide us with clues as whether they may have a role in host specificity or during interaction with insect vectors, which remains to be elucidated.

5. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

In summary, genome sequences of four species in the genus Erwinia have provided us with the genetic composition of these conserved erwinias. Comparative genomic analyses have helped us to draw preliminary conclusions about the evolution and the classification of Erwinia species. However, the host specificity and differential virulence phenomenon of Erwinia strains is still not completely understood. Fully understanding the pathogen, its virulence mechanism and host specificity is very promising as whole genome sequencing and functional genomic studies are powerful hypothesis generators. With the advances of technologies and multidisciplinary collaboration, future work should address questions, to mention just a few: what are the functions of the PAI2 and PAI3 during interaction with insect vectors? What is the function of type VI secretion systems in erwinias, if there is any? What is the molecular mechanism of effector protein function such as DspE/A when they are translocated inside plant cells? Reconstructing the gene regulatory network of amylovoran biosynthesis using functional genomics tools such as microarray and computer modeling is also vital. We expect that there will be tremendous progress in the next decade or so in studying fire blight and related plant diseases, which will ultimately lead to the development of environmentally sound disease management strategies.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program Grant no. 2010-65110-20497 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

References

- Vanneste, J.L. Fire Blight: The Disease and Its causative Agent; Erwinia amylovora; CABI Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Norelli, J.L.; Aldwinckle, H.S.; Beer, S.V. Differential host × pathogen interactions among cultivars of apple and strains of Erwinia amylovora. Phytopathology 1984, 74, 136–139. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Korban, S.S.; Zhao, Y.F. Molecular signature of differential virulence in natural isolates of Erwinia amylovora. Phytopathology 2010, 100, 192–198. [Google Scholar]

- Geider, K.; Auling, G.; Jakovljevic, V.; Völksch, B. A polyphasic approach assigns the pathogenic Erwinia strains from diseased pear trees in Japan to Erwinia pyrifoliae. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 48, 324–330. [Google Scholar]

- López, M.M.; Roselló, M.; Llop, P.; Ferrer, S.; Christen, R.; Gardan, L. Erwinia piriflorinigrans sp. nov., a novel pathogen that causes necrosis of pear blossoms. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 561–567. [Google Scholar]

- Kube, M.; Migdoll, A.M.; Gehring, I.; Heitmann, K.; Mayer, Y.; Kuhl, H.; Knaust, F.; Geider, K.; Reinhardt, R. Genome comparison of the epiphytic bacteria Erwinia billingiae and E. tasmaniensis with the pear pathogen E. pyrifoliae. BMC Genomics 2010, 11, 393. [Google Scholar]

- Kube, M.; Migdoll, A.M.; Müller, I.; Kuhl, H.; Beck, A.; Reinhardt, R.; Geider, K. The genome of Erwinia tasmaniensis strain Et1/99, a non-pathogenic bacterium in the genus Erwinia. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 2211–2222. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.; Thapa, S.; Choi, B.; Kim, W.; Hur, J.; Cho, J.M.; Lim, J.; Choi, I.; Lim, C.K. Complete genome sequence of Japanese Erwinia strain Ejp617, a bacterial shoot blight pathogen of pear. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 586–587. [Google Scholar]

- Powney, R.; Smits, T.H.; Sawbridge, T.; Frey, B.; Blom, J.; Frey, J.E.; Plummer, K.M.; Beer, S.V.; Luck, J.; Duffy, B.; Rodoni, B. Genome sequence of an Erwinia amylovora strain with restricted pathogenicity to Rubus plants. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 795–796. [Google Scholar]

- Sebaihia, M.; Bocsanczy, A.M.; Biehl, B.S.; Quail, M.A.; Perna, N.T.; Glasner, J.D.; DeClerck, G.A.; Cartinhour, S.; Schneider, D.J.; Bentley, S.D.; et al. Complete genome sequence of the plant pathogen Erwinia amylovora strain ATCC 49946. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 2020–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Smits, T.H.M.; Rezzonico, F.; Kamber, T.; Blom, J.; Goesmann, A.; Frey, J.E.; Duffy, B. Complete genome sequence of the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora CFBP 1430 and comparison to other Erwinia spp. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2010, 23, 384–393. [Google Scholar]

- Smits, T.H.M.; Jaenicke, S.; Rezzonico, F.; Kamber, T.; Goesmann, A.; Frey, J.E.; Duffy, B. Complete genome sequence of the fire blight pathogen Erwinia pyrifoliae DSM 12163T and comparative genomic insights into plant pathogenicity. BMC Genomics 2010, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Toth, I.K.; Pritchard, L.; Birch, P.R.J. Comparative genomics reveals what makes an enterobacterial plant pathogen. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005, 44, 305–306. [Google Scholar]

- Triplett, L.; Zhao, Y.F.; Sundin, G.W. Genetic differences among blight-causing Erwinia species with differing host specificities identified by suppression subtractive hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 7359–7364. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, M.; Wang, D.; Bradley, C.; Zhao, Y.F. Genome sequence analyses of Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. glycinea and subtractive hybridization-based comparative genomics with nine pseudomonads. PLoS one 2011, 6, e16451. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; He, X.; Tai, C.; Ou, H.Y.; Rajakumar, K.; Deng, Z. mGenomeSubtractor: A web-based tool for parallel in silico subtractive hybridization analysis of multiple bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, W194–W200. [Google Scholar]

- Smits, T.H.M.; Rezzonico, F.; Pelludat, C.; Goesmann, A.; Frey, J.E.; Duffy, B. Evolutionary insights from Erwinia amylovora genomics. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 155, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.M.; Kim, J.F.; Beer, S.V. Regulation of hrp genes and type III protein secretion in Erwinia amylovora by HrpX/HrpY, a novel two component system, and HrpS. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2000, 13, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.M.; Laby, R.J.; Zumoff, C.H.; Bauer, D.W.; He, S.Y.; Collmer, A.; Beer, S.V. Harpin, elicitor of the hypersensitive response produced by the plant pathogen Erwinia amylovora. Science 1992, 257, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.F.; Sundin, G.W.; Wang, D.P. Construction and analysis of pathogenicity island deletion mutants in Erwinia amylovora. Can. J. Microbiol. 2009, 55, 457–464. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, C.-S.; Beer, S.V. Molecular genetics of Erwinia amylovora involved in the development of fire blight. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005, 253, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, C.-S.; Kim, J.F.; Beer, S.V. The Hrp pathogenicity island of Erwinia amylovora and identification of three novel genes required for systemic infection. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2005, 6, 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.F.; Blumer, S.E.; Sundin, G.W. Identification of Erwinia amylovora genes induced during infection of immature pear tissue. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 8088–8103. [Google Scholar]

- Nissinen, R.M.; Ytterberg, A.J.; Bogdanove, A.J.; van Wijk, K.J.; Beer, S.V. Analyses of the secretomes of Erwinia amylovora and selected hrp mutants reveal novel type III secreted proteins and an effect of HrpJ on extracellular harpin levels. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2007, 8, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.F.; He, S.Y.; Sundin, G.W. The Erwinia amylovora avrRpt2EA gene contributes to virulence on pear and AvrRpt2EA is recognized by Arabidopsis RPS2 when expressed in Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2006, 19, 644–654. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanove, A.J.; Bauer, D.W.; Beer, S.V. Erwinia amylovora secretes DspE, a pathogenicity factor and functional AvrE homolog, through the Hrp (type III secretion) pathway. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 2244–2247. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudriault, S.; Malandrin, L.; Paulin, J.P.; Barny, M.A. DspA, an essential pathogenicity factor of Erwinia amylovora showing homology with AvrE of Pseudomonas syringae, is secreted via Hrp secretion pathway in a DspB-dependent way. Mol. Microbiol. 1997, 26, 1057–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Asselin, J.E.; Bocsanczy, A.M.; Kim, J.F.; Oh, C.S.; Beer, S.V. Eop1 from a rubus strain of Erwinia amylovora functions as a host–range limiting factor. Phytopathology 2011, 101, 935–944. [Google Scholar]

- Boureau, T.; Siamer, S.; Perino, C.; Gaubert, S.; Patrit, O.; Degrave, A.; Fagard, M.; Chevreau, E.; Barny, M.A. The HrpN effector of Erwinia amylovora, which is involved in type III translocation, contributes directly or indirectly to callose elicitation on apple leaves. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2011, 24, 577–584. [Google Scholar]

- Boureau, T.; ElMaarouf-Bouteau, H.; Garnier, A.; Brisset, M.; Perino, C.; Pucheu, I.; Barny, M. DspA/E, a type III effector essential for Erwinia amylovora pathogenicity and growth in planta, induces cell death in host apple and nonhost tobacco plants. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2006, 19, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.D.; Bonasera, J.M.; Kim, J.; Nissinen, R.M.; Beer, S.V. Apple proteins that interact with DspA/E, a pathogenicity effector of Erwinia amylovora, the fire blight pathogen. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2006, 19, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, C.S.; Beer, S.V. AtHIPM, an ortholog of the apple HrpN-interacting protein, is a negative regulator of plant growth and mediates the growth-enhancing effect of HrpN in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007, 145, 426–436. [Google Scholar]

- Sarowar, S.; Zhao, Y.F.; Guerra, R.; Ali, S.; Zheng, D.; Wang, D.P.; Korban, S.S. Expression profiles of differentially regulated genes during early stages of apple flower infection with Erwinia amylovora. J. Exp. Bot. 2011. 1327.err147. [Google Scholar]

- Koczan, J.M.; McGrath, M.J.; Zhao, Y.F.; Sundin, G.W. Contribution of Erwinia amylovora exopolysaccharides amylovoran and levan to biofilm formation: Implications to pathogenicity. Phytopathology 2009, 99, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Korban, S.S.; Zhao, Y.F. The Rcs phosphorelay system is essential for pathogenicity in Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2009, 10, 277–290. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Korban, S.S.; Pusey, L.; Zhao, Y.F. Characterization of the RcsC sensor kinase from Erwinia amylovora and other enterobacteria. Phytopathology 2011, 101, 701–717. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.F.; Wang, D.; Nakka, S.; Sundin, G.W.; Korban, S.S. Systems-level analysis of two-component signal transduction systems in Erwinia amylovora: Role in virulence, regulation of amylovoran biosynthesis and swarming motility. BMC Genomics 2009, 10, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, M.; Orye, K.; Bobev, S.; Devreese, B.; Van Beeumen, J.; De Bruyn, A.; Busson, R.; Herdewijn, P.; Morreel, K.; Messens, E. Influence of amylovoran production on virulence of Erwinia amylovora and a different amylovoran structure in E. amylovora isolates from Rubus. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2001, 107, 839–844. [Google Scholar]

- Langlotz, C.; Schollmeyer, M.; Coplin, D.L.; Nimtz, M.; Geider, K. Biosynthesis of the repeating units of the exopolysaccharides amylvooran from Erwinia amylovora and stewartan from Pantoea stewartii. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 75, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.F.; Qi, M.; Wang, D. Evolution and function of flagellar and non-flagellar type III secretion systems in Erwinia amylovora. Acta Hort. 2011, 896, 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Nakka, S.; Qi, M.; Zhao, Y.F. The Erwinia amylovora PhoPQ system is involved in resistance to antimicrobial peptide and suppresses gene expression of two novel type III secretion systems. Microbiol. Res. 2010, 165, 665–673. [Google Scholar]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).