Abstract

Skeletal muscle is a pivotal organ in humans that maintains locomotion and homeostasis. Muscle atrophy caused by sarcopenia and cachexia, which results in reduced muscle mass and impaired skeletal muscle function, is a serious health condition that decreases life longevity in humans. Recent studies have revealed the molecular mechanisms by which long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) regulate skeletal muscle mass and function through transcriptional regulation, fiber-type switching, and skeletal muscle cell proliferation. In addition, lncRNAs function as natural inhibitors of microRNAs and induce muscle hypertrophy or atrophy. Intriguingly, muscle atrophy modifies the expression of thousands of lncRNAs. Therefore, although their exact functions have not yet been fully elucidated, various novel lncRNAs associated with muscle atrophy have been identified. Here, we comprehensively review recent knowledge on the regulatory roles of lncRNAs in skeletal muscle atrophy. In addition, we discuss the issues and possibilities of targeting lncRNAs as a treatment for skeletal muscle atrophy and muscle wasting disorders in humans.

1. Introduction

More than 400 skeletal muscles are present throughout the human body and account for 30–40% of the body weight in the human adult. The coordinated action of the skeletal muscles enables body movement, exercise, and postural maintenance. Additionally, maintaining adequate skeletal muscle mass is important for a healthy lifestyle to maintain body temperature, homeostasis, metabolism, blood pumping, and myokine secretion. The skeletal muscle is also a highly plastic organ. The skeletal muscle mass decreases with immobilization, malnutrition, and injury [1,2,3]. Diseases such as cancers, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) reduce skeletal muscle mass [4,5,6,7,8]. Cancer-induced cachexia is a complex metabolic disorder characterized by marked muscular wasting and is implicated in approximately 30% of all cancer-related deaths [9]. Aging also causes the loss of muscle mass and strength, even if one does not encounter such adversities and diseases [10]. The reduction in skeletal muscle mass due to aging is called sarcopenia and results in bedridden status, dysphagia, and dyspnea. Sarcopenia is present in 9.9–40.4% of community-dwelling older adults and impedes healthy life maintenance [11]. Moreover, in the recent COVID-19 pandemic, loss of muscle strength as a consequence of viral infection is becoming a major problem, regardless of the underlying diseases [12]. Global social isolation and physical inactivity due to the COVID-19 pandemic are also responsible for muscle weakness, even in non-virus-infected groups [13,14]. Skeletal muscle atrophy and weakness decrease the quality of life due to reduced activities of daily living and increased mortality from diseases [15]. On the other hand, resistance training is effective in alleviating muscle atrophy by improving both the quantity and quality of skeletal muscle. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses of cohort studies have indicated that muscular training reduces the risk of mortality, cardiovascular diseases, cancers, and diabetes [16]. However, performing adequate training safely without injury is difficult for sick and elderly individuals who have lost physical fitness. Therefore, elucidating the pathophysiology of skeletal muscle atrophy caused by complex factors is required to develop safe and effective treatments for muscle atrophy.

The balance between the synthesis and degradation of skeletal muscle components is the primary factor that determines the skeletal muscle mass [15]. The insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is a positive regulator of skeletal muscle mass. When IGF-1 binds to its receptor on the plasma membrane through a sequence of phosphorylation reaction cascades mediated by Akt and mTOR, it activates p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K) and suppresses 4E-BP1, which are regulators of protein synthesis [17,18]. Consequently, activated translational initiation and elongation, and increased ribosome biogenesis contribute to skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Stimulated Akt inhibits the nuclear translocation of FoxO transcription factors and prevents the expression of muscle-specific E3 ubiquitin ligases, MuRF1 and Atrogin-1/MAFbx [19,20,21]. The β-adrenergic pathway also enhances muscle protein synthesis but is known to be associated with adverse cardiac-related events [22]. Protein synthesis normally predominates over protein degradation, whereas in pathogenic conditions, several signaling pathways are stimulated, leading to the degradation of muscle proteins. Myostatin, a cytokine belonging to the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) superfamily, is a well-known inducer of skeletal muscle atrophy. An important negative regulation of skeletal muscle mass by myostatin was first demonstrated by McPherron et al. in 1997, using myostatin-deficient mice [23]. The mice showed a 2-fold increase in muscle mass due to increases in both muscle fiber size (hypertrophy) and myofiber number (hyperplasia). Increased muscle mass has also been observed in other animals, such as cattle, sheep, dogs, goats, pigs, rabbits, and fish, with naturally occurring or artificially mutated myostatin genes [24,25,26,27]. In Japan, muscle hypertrophy of sea bream with inactivation of myostatin protein by genome editing technology is commercially available [28]. Spontaneous mutations in the myostatin gene resulted in increased skeletal muscle mass in humans [29]. Intriguingly, activin, another member of the TGF-β superfamily, induces muscle atrophy [30]. Activin appears to be more potent than myostatin in inducing muscle atrophy in primates [31]. Both myostatin and activin signaling contribute to the predominant proteolysis of muscle proteins via the transcription factors Smad2/3 [32]. In addition, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and glucocorticoid signaling negatively regulate skeletal muscle mass [18,33]. Eventually, this atrophy-related signaling results in the activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system [34]. Under several pathogenic conditions, hyperactivation of autophagy, another proteolytic system, contributes to the reduction of skeletal muscle mass [35].

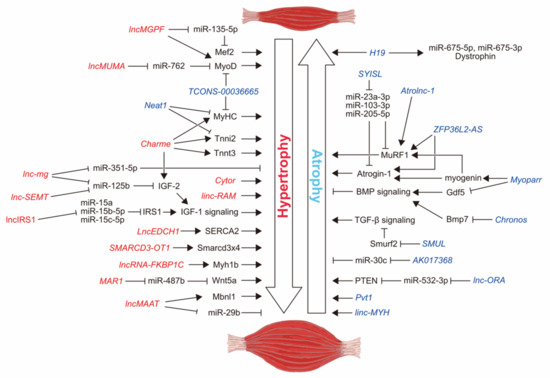

Over the past decade, emerging evidence has demonstrated that long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which are not translated into proteins, serve as novel regulators of diverse biological processes [36]. lncRNAs are more than 200 nucleotides (nt) in length and are expressed not only from non-coding genomic DNA, including cis-regulatory regions, introns, 5′- and 3′- untranslated regions, intergenic regions, and repetitive sequences, but are also transcribed from the coding genomic DNA in the antisense direction [37]. A curated database of human lncRNAs contains 268,848 lncRNA genes as of November 2019 [38]. Dysregulated lncRNA expression is associated with cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders [39,40]. lncRNAs have pleiotropic functions; transcriptional and translational regulation, chromatin modification, mRNA stability, RNA splicing, and nuclear body architecture [37,41]. The lncRNA sequences tend not to be conserved among species. In contrast to the unique functional domains found in proteins, the characteristic functional sequences of lncRNAs have not been fully determined [41]. The expression levels of lncRNAs are generally lower than those of mRNAs, and they are localized predominantly in the nucleus. Depending on their unique nucleic acid sequences, lncRNAs directly interact with proteins or genomic DNA and regulate the expression of downstream genes in the nucleus [42]. In the cytoplasm, lncRNAs function as decoys against microRNAs (miRNAs) [43], which post-transcriptionally fine-tune gene expression through mRNA degradation and translation inhibition [44]. Genome-wide studies using next-generation sequencing technology have identified thousands of novel lncRNAs in skeletal muscle. Additionally, lncRNAs have provided new insights into the regulation of skeletal muscle cell proliferation and differentiation. Recent studies have revealed the molecular functions of lncRNAs in the regulation of skeletal muscle mass. In this review, we summarize recent findings regarding lncRNAs involved in skeletal muscle atrophy caused by cancer cachexia, aging, neurological diseases, disuse, and fasting. The mechanism of muscle atrophy by lncRNA Myoparr, which we discovered, has been described in detail. We also discuss the possibilities and limitations of using lncRNAs as a treatment for human muscle atrophy. The molecular roles of lncRNAs described in this review in the regulation of skeletal muscle mass are summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the lncRNAs involved in the regulation of skeletal muscle mass. Based on the results from in vivo experiments (partial in vitro experiments are included for ceRNAs), lncRNAs increasing muscle mass are represented in red. lncRNAs decreasing muscle mass are represented in blue.

2. Myogenic Differentiation-Related lncRNAs

During embryogenesis, myogenic progenitor cells, myoblasts, proliferate until they reach an appropriate number, which is a major predictor of future skeletal muscle mass. Following mitotic arrest, myoblasts begin to differentiate and fuse to form multinucleated myotubes. Subsequently, myotubes further mature into myofibers, which form skeletal muscle tissues [45]. The formation of skeletal muscle, known as myogenesis, is regulated by a multistep process orchestrated by many transcription factors [46]. The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor Myf5 initiates myogenesis [47] and cooperatively works with the bHLH transcription factor MyoD to determine myogenic cell fate [48]. Cell cycle of myoblasts is arrested concomitantly with myogenic differentiation. MyoD induces the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, p21 and p57, and p53 family members to arrest the cell cycle in myoblasts [49,50,51]. MyoD also activates the expression of the bHLH transcription factor, myogenin, leading to the entry of myoblasts into the myogenic differentiation program [52]. Formation of multinucleated myotubes by myoblast-myoblast fusion is mediated by the muscle-specific transmembrane protein myomaker [53]. Another bHLH transcription factor, MRF4, and MEF2 family transcription factors are also involved in both cell specification and differentiation [54,55]. Many lncRNAs have been identified in myoblasts and myotubes and have been shown to regulate myogenic differentiation [56]. Subsequently, the role of these lncRNAs in the regulation of skeletal muscle mass was investigated. In this section, we introduce the molecular functions of these lncRNAs, focusing on the regulation of myogenic differentiation and skeletal muscle mass.

2.1. Myoparr

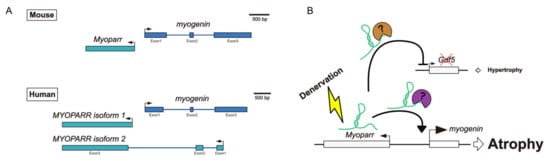

By analyzing the transcriptionally activated region around the myogenin locus during C2C12 differentiation using an RNA polymerase II (Pol II) binding signal, we identified a novel lncRNA from the myogenin promoter region and named it myogenin promoter-associated myogenic regulatory antisense lncRNA, Myoparr [57]. Myoparr is expressed in a head-to-head fashion along with the myogenin gene during myogenic differentiation of human and mouse myoblasts. Mouse Myoparr is a single exon lncRNA and the lengths of Myoparr are 1172 nt and 1167 nt in C2C12 cells and C57BL/6J mice, respectively. This difference in length was due to the different lengths of repeat sequences in Myoparr. In humans, two types of MYOPARR exist: one is a 1977 nt lncRNA (isoform 1) consisting of a single exon, and the other is a 2245 nt lncRNA (isoform 2) consisting of three exons (Figure 2A). Human MYOPARR isoform 1 is expressed in a head-to-head fashion along with the myogenin gene, as in mice. In isoform 2, the first exon is expressed in reverse orientation from the last exon of myogenin, the 2nd exon of MYOPARR is in the 2nd intronic region of myogenin, and the 3rd exon is essentially in the same position as in isoform 1.

Figure 2.

(A) Structures of both mouse Myoparr and human MYOPARR. (B) Molecular functions of mouse Myoparr in the regulation of muscle mass. Denervation activates Myoparr expression, and then Myoparr increases and decreases myogenin and Gdf5 expression, respectively. Thus, Myoparr promotes muscle atrophy caused by denervation.

The timing of Myoparr and myogenin expression were mutually correlated in human and mouse myoblasts, suggesting that Myoparr participates in the regulation of myogenin expression [57]. Our group showed that Myoparr knockdown drastically decreased myogenin expression at the transcriptional level and inhibited the myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells. Although several promoter-associated lncRNAs are involved in the DNA methylation status of neighboring genes [58], Myoparr knockdown did not affect the DNA methylation status of the myogenin promoter region. Instead, the reduction in Myoparr expression decreased Pol II recruitment, histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), and histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) levels in the myogenin locus. Mechanistically, Myoparr directly binds to the DEAD-box protein Ddx17, a transcriptional co-activator, and promoted protein–protein interactions between Ddx17 and the histone acetyltransferase PCAF during C2C12 differentiation. The binding of PCAF to Ddx17 is essential for the high transcriptional activity of Ddx17 [59]. Myoparr is mainly localized to the chromatin fraction and binds to the myogenin promoter. Therefore, Myoparr activates myogenin expression by promoting histone acetylation at the myogenin promoter via the Ddx17-PCAF complex. In addition to myogenin expression, Myoparr regulates cell cycle withdrawal by activating the expression of miR-133b, miR-206, and H19 lncRNA, which promotes myoblast cell cycle withdrawal [60,61,62]. Thus, Myoparr promotes both myogenic differentiation and myoblast cell cycle withdrawal by activating myogenin, miR-133b, miR-206, and H19 during C2C12 differentiation. Although the molecular function of Myoparr in myogenic differentiation of mouse myoblasts is clear, the role of MYOPARR in human myogenesis remains to be elucidated.

The functions of lncRNAs can be altered depending on their binding partners [42]. We recently identified heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (hnRNPK) as a Myoparr binding protein [63]. Unlike Ddx17, hnRNPK negatively regulates the expression of myogenin at the transcriptional level. Deleting the hnRNPK-binding region of Myoparr enhances myogenin promoter activity. Interestingly, hnRNPK knockdown caused morphological abnormalities in the myotubes. Since hnRNPK knockdown increased the expression levels of MyoD protein and myogenin, hnRNPK might contribute to preventing premature differentiation of myoblasts by restricting Myoparr function.

Although the myogenin gene is essential for skeletal muscle development [64,65], its expression is suppressed after myogenesis by innervation. Conversely, in denervated skeletal muscles, reactivated myogenin expression triggers the expression of E3 ligases MuRF1 and Atrogin-1 [66]. Therefore, dysregulated myogenin expression results in skeletal muscle atrophy. During myogenic differentiation, Myoparr shares the same promoter region as myogenin. Moreover, MyoD and TGF-β signaling directly regulate Myoparr expression through the myogenin promoter region [57]. Therefore, we hypothesized that Myoparr expression is also activated by denervation in adult skeletal muscles. Sciatic nerve transection in mice resulted in a 10–20% reduction in tibialis anterior (TA) muscle mass 3–7 days after treatment. In this situation, we found increased Myoparr and myogenin expression. Since Myoparr is essential for myogenin expression during myogenic differentiation, we next examined whether Myoparr contributed to the activation of myogenin in denervated skeletal muscles. RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown of Myoparr decreased myogenin expression at both the mRNA and protein levels in denervated muscles (Figure 1, right panel). Moreover, Myoparr knockdown attenuated denervation-induced muscle atrophy (Table 1). Increased Myoparr expression was observed in denervated muscles but not in other muscle atrophy conditions caused by cancer cachexia, hindlimb suspension, cast immobilization, fasting, and dexamethasone administration [67]. Therefore, Myoparr serves as a specific inducer of muscle atrophy caused by denervation.

To determine whether alleviated muscle atrophy by Myoparr inhibition was caused only by the cell-autonomous effect of preventing myogenin reactivation, or whether other mechanisms are also responsible, we performed a comprehensive gene expression analysis in Myoparr-depleted TA muscles by RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis. Myoparr knockdown increased and decreased the expression of the 423 and 425 genes, respectively [68]. Among them, Gdf5, which encodes one of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) family members, was previously shown to alleviate muscle atrophy caused by denervation [69]; therefore, we focused on the expression changes of Gdf5 by Myoparr knockdown. Three days after Myoparr knockdown, substantially increased Gdf5 expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis of TA muscles (Figure 1, right panel). Moreover, Myoparr knockdown activated BMP signaling, as indicated by the increased phosphorylation levels of Smad1/5/8. Thus, our findings indicated that skeletal muscle atrophy caused by denervation may be regulated by the Myoparr/myogenin/Gdf5 axis (Figure 1, right panel, and Figure 2B). Intriguingly, the set of genes whose expression was affected by Myoparr knockdown differed substantially between myogenic differentiation and denervation-induced muscle atrophy [68], suggesting that in skeletal muscle atrophy conditions Myoparr functions with a binding protein other than Ddx17 or hnRNPK, which were identified as Myoparr-binding proteins during myogenic differentiation [57,63].

2.2. Charme

In 2015, lnc-405 was first identified in differentiating C2C12 cells by RNA-Seq analysis [70]. Later, this lncRNA was renamed the chromatin architect of muscle expression (Charme) [71]. Charme is specifically expressed in skeletal and cardiac muscles, localized primarily to the chromatin fraction in the nucleus, and has orthologous transcripts in humans. Charme expression was observed after day 1 of myogenesis, and knockdown of Charme inhibited the myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells. Charme is associated not only with its own transcribed genomic region but also with Igf2, Tnnt3, and Tnni2 loci. Pol II recruitment and H3K9ac modification in these regions were reduced by Charme knockdown. Charme knockdown also caused physical dissection of the Igf2 locus from the genomic region in which Charme itself was transcribed. It is noteworthy that forced overexpression of Charme by plasmid DNA did not rescue the defect caused by Charme knockdown. Therefore, Charme can promote myogenic differentiation by bringing its own transcribed genomic region close to the Igf2 locus. Intriguingly, the binding of PTBP1, a splicing regulator, and MATR3, an RNA/DNA binding protein, to intron 1 of Charme was required for the localization of Charme to the nucleus [72]. In the gastrocnemius muscles of Charme knockout mice, expression levels of MCK, myosin heavy chain (MyHC), Tnnt3, Tnni2, and Igf2 were reduced, resulting in skeletal muscle atrophy in 4-week-old mice (Figure 1, left panel, and Table 1) [71]. These knockout mice also exhibited aberrant heart size, shape, and hypertension. Charme knockout mice were not lethal and there were no reproduction problems, but they had a lifespan of less than one year.

2.3. Neat1

In the nucleus, several lncRNAs can form liquid droplet-like features, which are referred to as architectural lncRNAs [73]. Nuclear-enriched abundant transcript 1 (Neat1) is an architectural lncRNA, and its expression is increased during C2C12 differentiation [74]. Gain- and loss-of-function experiments have indicated that Neat1 inhibits p21 expression and promotes myoblast proliferation. At the same time, Neat1 inhibited myogenic differentiation by suppressing myogenin, Myh4, Tnni2, and Myomaker expression. Unlike the well-recognized function of Neat1 as an architectural lncRNA [75], Neat1 interacts with enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (Ezh2), a component of the polycomb repressive complex 2, and recruited Ezh2 to the promoter regions of myogenin and p21 in myoblasts [74]. During the lifetime of the mice, Neat1 expression tended to increase until 4 weeks of age and then declined [76]. In adult mice, Neat1 expression is increased in skeletal muscle during regeneration after cardiotoxin (CTX)-induced skeletal muscle injury [74]. Moreover, Neat1 expression consistently increased in conditions of muscle atrophy, including denervation, hindlimb suspension, dexamethasone administration, and cast immobilization [67]. It is noteworthy that lentivirus-mediated knockdown of Neat1 increased skeletal muscle mass in the TA, gastrocnemius, and quadriceps muscles with increased myogenin, Myh4, and Tnni2 expression (Figure 1, left panel, and Table 1) [74]. However, Neat1 inhibition delayed skeletal muscle regeneration following CTX injection in the gastrocnemius muscle, with reduced satellite cell numbers. Thus, inhibition of Neat1 would be beneficial for inducing muscle hypertrophy, but detrimental to injured muscle.

2.4. TCONS-00036665

RNA immunoprecipitation using an Ezh2 antibody in the longissimus dorsi muscle of pigs revealed 356 Ezh2-binding lncRNAs [77]. TCONS-00036665 was identified as an Ezh2-binding lncRNA in addition to Neat1 and its expression increased during myogenic differentiation. TCONS-00036665 is mainly localized in the nucleus. TCONS-00036665 overexpression promoted proliferation but inhibited differentiation of pig skeletal muscle satellite cells. In contrast, TCONS-00036665 knockdown inhibited the proliferation but promoted the myogenic differentiation of satellite cells, indicating that TCONS-00036665 is required for satellite cell proliferation. Similar to Neat1, TCONS-00036665 recruited Ezh2 to the promoter regions of p21, myogenin, and Myh4, thereby repressing the expression of these genes and maintaining the proliferative state of satellite cells. Interestingly, overexpression of TCONS-00036665 in the skeletal muscles of the lower limbs of 6-week-old mice induced a decrease in muscle weight, accompanied by decreased expression of MyHC, MyoD, and myogenin proteins (Figure 1, left panel) [77]. Although the detailed molecular mechanism remains largely unknown, it is likely that TCONS-00036665 negatively regulates postnatal muscle growth (Table 1).

2.5. linc-RAM

Conventionally, lncRNAs have not been considered to encode proteins, but several small polypeptides encoded by lncRNAs have been discovered [78]. The small polypeptides encoded by lncRNAs are called micropeptides. Myoregulin is a 46 amino acid micropeptide that is specifically expressed in the skeletal muscle [79]. Myoregulin directly interacts with sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) and inhibits Ca2+ uptake into the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Mice lacking myoregulin show improved exercise performance. On the other hand, Yu et al. reported that an lncRNA encoding myoregulin functions not only to encode a micropeptide but also as a regulatory ncRNA [80]. They used MyoD chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-Seq data to identify 45 lncRNAs, whose expression was regulated by MyoD during C2C12 cell differentiation. One of them was named lincRNA activator of myogenesis (linc-RAM). Overexpression of linc-RAM promoted myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells, while no effect was observed in linc-RAM mutants without the open reading frame of myoregulin. These findings suggest that the effect of linc-RAM in promoting myogenic differentiation is a feature of regulatory ncRNAs, independent of micropeptides. linc-RAM was localized in both the nuclei and cytoplasm of C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes. It has been hypothesized that the function of linc-RAM in the nucleus may be different from that of myoregulin. Using RNA immunoprecipitation and pulled-down assays, linc-RAM was found to be physically associated with MyoD [80]. Moreover, linc-RAM facilitated the association of the MyoD–Baf60c–Brg1 complex and enhanced the transcriptional activity of MyoD in the myogenic cells. linc-RAM knockout mice, which were generated by deleting exon 2 of linc-RAM, had fewer myofibers than wild-type mice (Figure 1, left panel, and Table 1) [80]. These mice also showed smaller myofiber size after 14 days of muscle regeneration following CTX injection. Notably, these mice retained intact myoregulin; therefore, reduced myofiber number and regeneration potential would depend on linc-RAM deficiency. The same group later found cytosolic linc-RAM function [81]. In myotubes, the majority of linc-RAM localizes in the cytoplasm, where linc-RAM interacts with glycogen phosphorylase (PYGM), which is involved in glycogen metabolism. Interestingly, PYGM promoted myogenic differentiation in an enzyme activity-dependent manner. linc-RAM positively regulated the enzymatic activity of PYGM by interacting with PYGM. Thus, crosstalk between lncRNAs and cellular metabolism may be a new regulator of myogenic differentiation. Other micropeptides have been identified in skeletal muscle cells and tissues [82]; therefore, it is expected that more examples of lncRNAs that function as both micropeptides and regulatory ncRNAs will be identified. Further studies are required to elucidate how the functions of both micropeptides and regulatory ncRNAs are differentially executed from one lncRNA.

2.6. lncMGPF

Murine lncRNA muscle growth-promoting factor, lncMGPF, is highly expressed in skeletal muscle tissues and promotes myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells [83]. lncMGPF homologs have been identified in humans and pigs. lncMGPF knockout mice showed slower growth, smaller skeletal muscle, and weaker muscle regeneration than wild-type mice (Table 1). Overexpression of lncMGPF resulted in larger skeletal muscles than in wild-type mice, indicating that lncMGPF promotes skeletal muscle mass. Mechanistically, lncMGPF acted as a decoy for miR-135-5p and increased the expression of transcription factor Mef2c (Figure 1, left panel) [83]. Additionally, lncMGPF promoted human antigen R (HuR)-mediated mRNA stabilization of both MyoD and myogenin (Figure 1, left panel) [83]. Interestingly, 10 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in pig lncMGPF have been identified in commercial and Chinese local pig breeds [84]. These SNPs are linked to lncMGPF stability and skeletal muscle growth. Taken together, lncMGPF may be a unique lncRNA with functional SNPs. However, further studies are required to determine whether lncMGPF antagonizes muscle atrophy.

3. lncRNAs Related to Muscle Atrophy and Hypertrophy Conditions

Sarcopenia is characterized by the age-related loss of muscle mass and skeletal muscle function [85]. A comparison of the expression profiles of lncRNAs in skeletal muscle biopsy samples from old and young participants identified 76 upregulated and 76 downregulated lncRNAs [86]. Using the 271 increased mRNAs and 153 decreased mRNAs discovered at the same analysis, Zheng et al. constructed a co-expression network between lncRNAs and mRNAs, and found that lncRNAs AC004797.1, PRKG1-AS1, and GRPC5D-AS1 may be involved in aging-associated muscle atrophy [86]. Another group has shown that the expression of metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript-1 (Malat1), which is a nuclear-retained lncRNA, decreased with age in mouse skeletal muscles [87]. Mikovic et al. also reported that Malat1 expression decreases with age [76]. Additionally, aging decreased the expression of genome imprinting-related lncRNAs, Gtl2/Meg3, Mirg, and Rtl1 [76]. Significantly decreased Gtl2/Meg3 expression in skeletal muscle was also observed during skeletal muscle growth in 5–13-week-old mice [88]. Using four muscle atrophy models, cancer cachexia, denervation, cast immobilization, and fasting, it was found that the expression of 524, 283, 234, and 273 lncRNAs, respectively, was deregulated in each atrophy condition [89]. Of these, 51 lncRNAs showed common changes in expression across the four muscle atrophy models, suggesting that they might be associated with the onset or progression of muscle atrophy. Thus, the expression levels of lncRNAs have been revealed to be altered by muscle atrophy conditions or wasting disorders. In this section, we introduce the molecular functions of lncRNAs discovered under skeletal muscle atrophy or hypertrophy conditions.

3.1. Chronos

Chronos, previously referred to as Gm17281, is skeletal muscle- and heart-enriched lncRNA. Among striated muscles, Chronos is specifically expressed in fast-twitch myofibers [90]. Chronos expression largely decreased after CTX-induced muscle injury. In addition, a progressive increase in Chronos expression was observed with age, whereas Chronos expression was not altered by hindlimb suspension or streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. The knockdown of Chronos resulted in myofiber hypertrophy, as shown by a 42% increase in myofiber cross-sectional area (CSA) in mice (Table 1). It is worth mentioning that the degree of this hypertrophy was comparable to that of siRNA-mediated myostatin knockdown [90]. Chronos knockdown increased Bmp7 expression and led to the activation of BMP signaling, indicated by phosphorylated Smad1/5, which is an inducer of skeletal muscle hypertrophy in mice [69]. Inhibition of Bmp7 expression counteracted muscle hypertrophy caused by Chronos inhibition. Mechanistically, Chronos suppressed Bmp7 expression by recruiting Ezh2 to the upstream region of the Bmp7 gene via the Chronos homology region [90]. Thus, Chronos negatively regulated skeletal muscle mass by suppressing Bmp7 expression (Figure 1, right panel).

3.2. Atrolnc-1

Skeletal muscle loss due to cachexia increases the risk of morbidity and mortality in patients with cancer and CKD [4,7]. Sun et al. examined lncRNAs whose expression differed in three murine cachexia conditions, including cancer, CKD, and fasting, using microarray analysis. They identified 17 lncRNAs whose expression was dysregulated in the three cachexia conditions [91]. The expression levels of eight lncRNAs, 1110038B12Rik, Snhg8, Snhg1, Sngh4, Gm14005, Sox2ot, Bvht, and 1700007L15Rik, and nine lncRNAs, A3300009N23Rik, 1700020l14Rik, Airn, Meg3/Gtl2, Nctc1, Rian, H19, Neat1, Gt(ROSA)26Sor, commonly increased or decreased in the three cachexia conditions, respectively. Among them, the expression of 1110038B12Rik was robustly increased under these cachexia conditions; therefore, 1110038B12Rik was named Atrolnc-1. Increased Atrolnc-1 expression after fasting was confirmed and observed after dexamethasone treatment in mice [92,93]. Overexpression and knockdown of Atrolnc-1 in C2C12 myotubes revealed that Atrolnc-1 promoted proteolysis without affecting protein synthesis. Furthermore, overexpression of Atrolnc-1 in TA muscles using an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector induced muscle atrophy with increased MuRF1 expression in mice (Table 1). Knockdown of Atrolnc-1 increased TA muscle weight in a CKD mouse model, whereas no effect on TA muscle weight was observed in sham control mice [91]. As a molecular mechanism, Atrolnc-1 impeded ABIN-1, an inhibitor of NF-κB signal, and induced muscle atrophy by promoting NF-κB-mediated MuRF1 transcription (Figure 1, right panel) [91]. Thus, inhibition of Atrolnc-1 is a promising strategy for alleviating cachexia.

3.3. lncMAAT

The lncRNA muscle-atrophy-associated transcript lncMAAT is a promising therapeutic target for skeletal muscle atrophy. Li et al. first identified 1913 upregulated and 1117 downregulated lncRNAs in denervated gastrocnemius muscles compared with sham-operated muscles in mice using microarray analysis [94]. They further examined lncRNAs that play central roles in multiple types of skeletal muscle atrophy. They previously identified miR-29b, which is involved in multiple muscle atrophy [95,96], and then focused on lncRNAs that might interact with miR-29b through in silico analysis. This analysis identified 18 lncRNAs. Furthermore, four lncRNAs whose expression in skeletal muscle decreased after denervation were defined. Finally, lncMAAT, whose knockdown decreased C2C12 myotube diameter, was selected. The expression of lncMAAT was decreased in in vitro atrophy models by angiotensin II, H2O2, and TNF-α treatment in C2C12 myotubes. Additionally, lncMAAT expression was decreased in various types of muscle atrophy caused by angiotensin II infusion, fasting, immobilization, and aging in mice. No significant change in lncMAAT expression was observed in the heart atrophy model, indicating that decreased lncMAAT expression is specific to skeletal muscle atrophy. Interestingly, lncMAAT knockdown by two independent short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) reduced the weight of the gastrocnemius muscles of mice (Table 1). In addition, overexpression of lncMAAT effectively alleviated muscle atrophy caused by angiotensin II infusion, denervation, and immobilization in mice. Overexpression and knockdown of lncMAAT decreased and increased miR-29b expression, respectively. Contrary to our initial hypothesis, lncMAAT did not directly bind to miR-29b. Instead, lncMAAT interacts with the transcription factor Sox6 and prevents Sox6 from binding to the miR-29b promoter, thus contributing to the repression of miR-29b expression at the transcriptional level [94]. lncMAAT is located in the third intron of Mbnl1, which encodes one of the pivotal splicing regulators. Li et al. showed that lncMAAT positively regulates the expression of its host gene Mbnl1. Since knockdown of Mbnl1 reduced C2C12 myotube diameter, it is likely that lncMAAT regulates skeletal muscle mass by regulating miR-29b expression and RNA splicing events via Mbnl1 (Figure 1, left panel) [94].

3.4. Pvt1

Alessio et al. examined differentially expressed lncRNAs using models for skeletal muscle atrophy caused by denervation and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) by single-cell analysis [97]. The expression levels of lncRNA plasmacytoma variant translocation 1 (Pvt1), previously reported as a cell cycle regulator in carcinoma [98], were shown to increase under each muscle atrophy condition in mice [97]. Pvt1 knockdown in proliferating C2C12 myoblasts upregulates the expression of mitochondria-related genes, resulting in a fragmented mitochondrial network. In vivo knockdown of Pvt1 in the TA muscles of mice increased the size and number of mitochondria, as determined by electron microscopy [97]. Mitochondrial DNA content also increased after Pvt1 knockdown. In denervated muscles, the amount of mitochondria was reduced, and Pvt1 knockdown attenuated this reduction. Moreover, Pvt1 knockdown increased the proportion of oxidative myofibers in gastrocnemius muscles. Intriguingly, the CSA of both fast and slow myofibers increased after Pvt1 knockdown (Figure 1, right panel, and Table 1). Additionally, Pvt1 knockdown prevented the denervation-induced atrophy of slow myofibers. Although the detailed molecular mechanism is unknown, Pvt1 knockdown attenuated mitochondrial fragmentation, apoptosis, and autophagy via c-Myc phosphorylation and degradation [97].

3.5. LncEDCH1

RNA-Seq analysis of differentially expressed lncRNAs between a white recessive rock (a fast-growing broiler chicken) and Xinghua chicken (a slow-growing breed native to China) revealed that lncRNA lncEDCH1 was enriched in hypertrophic broiler chickens [99]. lncEDCH1 is evolutionarily conserved in wild turkeys and guineafowl. lncEDCH1 was highly expressed in breast and leg muscles, whereas its expression gradually decreased during myogenic differentiation of chicken primary myoblasts. lncEDCH1 has been shown to promote proliferation and inhibit differentiation of chicken primary myoblasts. Lentivirus-mediated lncEDCH1 overexpression and knockdown in 1-day-old chickens revealed that lncEDCH1 reduced intramuscular fat accumulation and inhibited muscle atrophy (Table 1). In addition, lncEDCH1 knockdown increased the distribution of fast-twitch muscle fibers in chicken skeletal muscle. Mechanistically, lncEDCH1 interacted with sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium Ca2+-ATPase 2 (SERCA2) protein to increase the stability of SERCA2, which increases SERCA2 activity and enhances ER calcium accumulation (Figure 1, left panel) [99]. lncEDCH1 also improved mitochondrial efficiency by activating the AMPK pathway. However, the mechanism by which lncEDCH1-induced reduction in cytosolic calcium leading to AMPK activation remains unknown. If the molecular function of lncEDCH1 is evolutionarily conserved, lncEDCH1 might be a potential target for the treatment of muscle atrophy and energy metabolism in humans.

4. Competing Endogenous lncRNAs Related to Skeletal Muscle Atrophy

In previous sections, the molecular mechanisms of lncRNAs in the regulation of muscle atrophy have been presented, mainly focusing on their interactions with specific proteins. However, lncRNAs also function by inhibiting the activity of miRNAs, that is, they act as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) against miRNAs. For example, the first ceRNA reported in skeletal muscle cells was long non-coding MD1 (linc-MD1), which is expressed in the same genomic region as miR-133b and miR-206. The expression of linc-MD1 increases during myogenic differentiation and is mainly localized in the cytoplasm [100]. The cytoplasmic accumulation of linc-MD1 is favored by the HuR protein [101]. Moreover, the expression levels of linc-MD1 are correlated with the progression of Duchenne muscular dystrophy [100,102]. Gain- and loss-of-function experiments showed that linc-MD1 promotes myogenic differentiation. Cesana et al. found that linc-MD1 inhibits miR-133 and miR-135 activities, and increases their target gene expression. Thus, linc-MD1 is required for myogenic differentiation by acting as a ceRNA against miR-133 and miR-135 [100]. In addition to linc-MD1, Meg3/Gtl2 regulates myogenic differentiation by acting as a ceRNA for miR-135 [103]. Moreover, multiple ceRNAs for miR-133 have been reported [104,105,106]. lncMGPF, mentioned above, is a ceRNA for miR-135-5p [83]. Considering these findings, many ceRNA-type lncRNAs have been discovered and shown to be associated with muscle atrophy. In this section, we introduce the molecular functions of lncRNAs acting as ceRNAs in the regulation of skeletal muscle mass.

4.1. H19

H19 is an imprinted lncRNA expressed from a maternally inherited allele in mammals and is highly expressed in skeletal muscle tissues after birth. H19 expression is induced during C2C12 cell differentiation. In vivo, H19 expression was increased or decreased by denervation or fasting in mice, respectively [67]. Several groups have reported the different molecular functions of H19 during in vitro myogenic differentiation. Kallen et al. showed that H19 contains binding sites for the let-7 miRNA family and acts as a ceRNA for these miRNAs [107]. In addition, H19 also worked as a source of miR-675-3p and miR-675-5p, which are encoded in the first exon of H19 and regulate the expression of Cdc6 and SMAD family members (Smad1/5) during myogenic differentiation (Figure 1, right panel) [62]. However, whether H19 promotes or inhibits muscle regeneration remains controversial [62,108]. In terms of the regulation of skeletal muscle mass, H19 knockout mice exhibited muscle hypertrophy, accompanied by an increased number of muscle fibers (Table 1) [108]. Intriguingly, H19 has recently been demonstrated to stabilize dystrophin protein by inhibiting ubiquitination induced by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Trim63 through direct binding to the dystrophin protein (Figure 1, right panel) [109]. Given that the expression level of H19 is very high compared to that of other lncRNAs, the multifunctional role of H19 in skeletal muscle function may be important. Further studies are needed to elucidate the molecular function of H19 in regulating skeletal muscle mass.

4.2. lnc-mg

Zhu et al. identified a myogenesis-associated lncRNA (lnc-mg) that partially overlaps with the Myh1 gene from the intergenic region between Myh1 and Myh4 in mice [110]. lnc-mg was highly expressed in skeletal muscle tissue and its expression increased during myogenic differentiation. Gain- and loss-of-function experiments revealed that lnc-mg promotes satellite cell differentiation. Interestingly, lnc-mg knockout mice had thinner muscle fibers and showed reduced muscle strength and endurance compared with wild-type mice [110]. Conversely, lnc-mg transgenic mice demonstrated thicker muscle fibers and greater muscle strength and endurance (Table 1). Moreover, myofiber diameters of lnc-mg transgenic mice were larger than those of wild-type mice even after denervation treatment. Mechanistically, lnc-mg functioned as a ceRNA against miR-125b to regulate the protein abundance of IGF-2 (Figure 1, left panel). Later, lnc-mg was shown to act as a molecular sponge for miR-351-5p, which inhibits C2C12 differentiation by targeting the Lactb gene (Figure 1, left panel) [111]. lnc-mg expression in the skeletal muscle was reduced after 48 h of fasting [93]. Thus, it would be interesting to investigate whether lnc-mg transgenic mice are also resistant to fasting-induced muscle atrophy.

4.3. SYISL

SYISL, a Synpo2 intron sense-overlapping lncRNA, was identified by microarray analysis as an lncRNA that is highly expressed in C2C12 myotubes [112]. SYISL overlaps with the fourth intron of the Synpo2 gene, but unlike Synpo2 expression, which is abundant in the stomach, small intestine, and heart, SYISL is highly expressed in muscle tissues such as the longissimus dorsi, leg muscle, and tongue. SYISL expression was directly activated by the MyoD protein via a MyoD-binding site (E-box) at its 5′ end. SYISL knockdown in differentiating C2C12 myoblasts increased the expression of genes associated with muscle differentiation, including myogenin, Myh1, Myh2, Myh4, Myh7, Tnni1, and Mybpc2, and decreased the expression of genes associated with axon guidance, cell cycle, and MAPK signaling pathways, including CDKs, N-Ras, Zeb2, Igf2bp3, Ki67, and Pcna. Further gain- and loss-of-function experiments of SYISL showed that SYISL promoted myoblast proliferation and myogenic fusion but inhibited myogenic differentiation. Mechanistically, SYISL recruits Ezh2 to the promoters of p21, myogenin, MCK, and Myh4 to induce trimethylation at H3K27, leading to epigenetic silencing and regulation of downstream gene expression [112].

In SYISL knockout mice, the CSA of myofibers was reduced but the number of myofibers was increased, resulting in muscle weight gain at 2 months (Table 1) [112]. However, unlike at a young age, sarcopenia-induced muscle atrophy was alleviated in 18-month-old SYISL knockout mice compared with wild-type mice [113]. A similar alleviation of sarcopenia was also observed by shRNA-mediated suppression of SYISL in 18-month-old mice. In addition, SYISL knockout mice were resistant to dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy [113] and these mice showed accelerated regeneration of skeletal muscle after CTX-induced muscle injury [112]. SYISL is conserved in humans and pigs, and overexpression of human and pig SYISL causes muscle atrophy in mice. The mechanism by which SYISL induces muscle atrophy is distinct from the regulation of muscle differentiation via Ezh2. SYISL acts as a sponge for miR-23a-3p, miR-103-3p, and miR-205-5p, leading to increased expression of the muscle atrophy-inducing genes FoxO3a, MuRF1, and Atrogin-1 (Figure 1, right panel) [113]. Thus, SYISL is an lncRNA that is involved in muscle atrophy across species.

4.4. lnc-SEMT

Sheep enhanced muscularity transcript lncRNA (lnc-SEMT) was specifically expressed in skeletal muscle by RNA-Seq analysis in sheep [114]. Overexpression and knockdown experiments in sheep myoblasts revealed that lnc-SEMT accelerates myoblast differentiation. The authors generated transgenic sheep that specifically overexpressed lnc-SEMT in the muscles. These sheep exhibited a 1.5-fold increase in skeletal muscle weight (Table 1). In contrast, in vivo knockdown of lnc-SEMT reduced gastrocnemius muscle mass by approximately 2/3. lnc-SEMT increased IGF-2 expression by acting as a ceRNA for miR-125b shown by in vitro experiments (Figure 1, left panel). Moreover, increased IGF-2 was confirmed in the longissimus dorsi muscle of lnc-SEMT-transgenic sheep, indicating that the lnc-SEMT/miR-125b/IGF-2 axis increases skeletal muscle mass [114].

4.5. lncIRS1

Li et al. identified 239 lncRNAs, 763 mRNAs, and 101 miRNAs differentially expressed between hypertrophic and leaner broilers using RNA-Seq analyses [115]. They focused on the sponging function of lncRNAs against miRNAs and identified lncIRS1, which was highly expressed in the skeletal muscle of hypertrophic broilers, by constructing an lncRNA-miRNA-gene network. In particular, lncIRS1 is primarily expressed in breast muscle and heart. During chicken embryogenesis, lncIRS1 is expressed in somites, and lncIRS1 regulates myoblast proliferation and differentiation of chicken myoblasts. Mechanistically, lncIRS1 acted as a ceRNA for miR-15a, miR-15b-5p, and miR-15c-5p, and increased IRS1 expression (Figure 1, left panel). Moreover, overexpression of lncIRS1 activated the IGF-1/Akt pathway by promoting Akt phosphorylation and increased the weight of chicken breast muscle by enlarging myofiber size (Table 1) [115]. Conversely, knockdown of lncIRS1 induced muscle atrophy. Additionally, although the experiment was performed in vitro, overexpression of lncIRS1 prevented muscle atrophy of myotubes induced by dexamethasone treatment. Taken together, the activation of lncIRS1 shows therapeutic potential for the treatment of muscle atrophy.

4.6. lncMUMA

Mechanical unloading-induced muscle atrophy-related lncRNA (lncMUMA) was identified as the lncRNA that was most downregulated in murine skeletal muscle by hindlimb suspension [116]. Decreased lncMUMA expression is associated with reduced muscle mass after hindlimb suspension. Knockdown of lncMUMA reduced gastrocnemius muscle weight and strength. Intriguingly, inhibited myogenic differentiation with decreased lncMUMA and MyoD expression was observed in microgravity-conditioned C2C12 cells, which mimic in vivo hindlimb suspension. In C2C12 myotubes, lncMUMA prevented MyoD degradation by antagonizing miR-762 activity as a ceRNA (Figure 1, left panel). MyoD expression was also decreased by hindlimb suspension. Therefore, it is hypothesized that lncMUMA maintains skeletal muscle mass by increasing MyoD expression as a ceRNA for miR-762. Zhang et al. generated miR-762 knock-in mice that showed lower muscle mass and decreased MyoD expression in the gastrocnemius muscle. They demonstrated that overexpression of lncMUMA alleviated muscle atrophy in these mice by increasing MyoD expression [116]. Furthermore, lncMUMA overexpression reversed skeletal muscle mass, muscle function, and MyoD expression caused by hindlimb suspension in wild-type mice (Table 1). Thus, boosting the expression of lncMUMA would be beneficial for alleviating muscle atrophy caused by hindlimb suspension, and further application to other muscle atrophy models should be considered.

4.7. MAR1

Comparative analysis of expression changes of lncRNAs in skeletal muscle tissue between 6- and 24-month-old mice by microarray analysis revealed that lncRNA muscle anabolic regulator 1, MAR1, was downregulated in aged skeletal muscle [117]. In mouse organs, MAR1 is highly expressed in the skeletal muscle, whereas modest MAR1 expression is detected in the heart and kidney. In skeletal muscle, the expression of MAR1 was decreased and increased by hindlimb suspension and fasting, respectively [93,117]. MAR1 expression also increased during C2C12 differentiation. MAR1 overexpression increased MyoD expression, whereas MAR1 knockdown decreased MyoD expression in C2C12 cells. MAR1 promotes C2C12 differentiation by directly associating with miR-487b, which inhibits myogenic differentiation by targeting Wnt5a [117,118]. Intriguingly, overexpression and knockdown of MAR1 increased and decreased skeletal muscle mass in mice, respectively (Table 1). Furthermore, MAR1 overexpression in the murine gastrocnemius muscle alleviated muscle atrophy caused by sarcopenia and hindlimb suspension. Increased Wnt5a expression was observed in this model. Thus, MAR1 may increase skeletal muscle mass by functioning as a ceRNA for miR-487b (Figure 1, left panel).

4.8. AK017368

AK017368 is highly expressed in the skeletal muscle and heart, and to some extent in the lung. AK017368 was localized in both the cytoplasm and nucleus of C2C12 cells, promoted proliferation, and inhibited the differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts by arresting them in the G0/G1 stage [119]. Knockdown of AK017368 in gastrocnemius muscles increased myogenin and MyHC expression and induced muscle hypertrophy with increased myofiber CSA in mice (Table 1). Bioinformatic analysis revealed that AK017368 has the recognition sequence of miR-30c, which is an inhibitor of proliferation and differentiation of C2C12 cells [120]. AK017368 acted as a sponge for miR-30c in C2C12 cells (Figure 1, right panel). The expression level of Tnrc6a, one of the targets of miR-30c [120], was increased by AK017368 overexpression. Therefore, the ceRNA function of AK017368 against miR-30c may be required for myoblast proliferation. However, the detailed molecular mechanism by which AK017368 inhibition causes skeletal muscle hypertrophy in mice remains unclear.

4.9. lnc-ORA

Cai et al. first identified the obesity-related lncRNA lnc-ORA as an adipogenic regulatory factor via regulation of the Akt/mTOR pathway [121]. Two years later, Cai et al. further demonstrated that lnc-ORA expression was upregulated with aging in mouse skeletal muscle tissues [122]. The expression levels of lnc-ORA also increased during the myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells, and lnc-ORA was shown to promote proliferation and inhibit the differentiation of C2C12 cells. Interestingly, dexamethasone treatment increased lnc-ORA expression in C2C12 myotubes, and lnc-ORA knockdown restored dexamethasone-induced myotube atrophy, suggesting that lnc-ORA is a novel inducer of muscle atrophy (Table 1). Indeed, overexpression of lnc-ORA in murine skeletal muscles induced muscle atrophy with increased levels of atrophy-related proteins, MuRF1 and Atrogin-1, and decreased levels of muscle differentiation-related proteins, MyoD and MyHC. In both proliferating and differentiating C2C12 myoblasts, lnc-ORA was predominantly localized to the cytoplasm, where lnc-ORA acted as a ceRNA against miR-532-3p [122]. Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate 3-phosphatase and dual-specificity protein phosphatase (PTEN), an inhibitor of the Akt/mTOR pathway, was the target of miR-532-3p, thereby lnc-ORA overexpression increased the expression levels of PTEN protein in C2C12 myoblasts (Figure 1, right panel). Additionally, lnc-ORA interacts with IGFBP2, resulting in reduced stability of MyoD and MyHC proteins. Therefore, lnc-ORA is a novel modifier of myogenic differentiation and skeletal muscle mass through regulation of the Akt/mTOR pathway and myogenic transcription factors.

5. Skeletal Muscle Fiber-Type-Associated lncRNAs

Skeletal muscle is composed of a combination of slow- and fast-twitch muscle fibers, which have distinct metabolic and contractile properties [123]. Slow-twitch muscle fibers are rich in mitochondria and have high oxidative capacity, whereas fast-twitch muscle fibers have higher amounts of glycogen and produce ATP primarily through glycolysis. Skeletal muscle fibers exhibit remarkable plasticity in energy metabolism and contractile function to meet an individual’s activity and energy demands. Aging, inactivity, and wasting diseases reduce muscle mass and alter muscle fiber-type composition, along with changes in metabolic capacity. Skeletal muscle aging, represented by sarcopenia, primarily causes a decrease in the number and diameter of fast-twitch muscle fibers compared to slow-twitch fibers [10,124]. Additionally, the muscle wasting seen in cancer patients, similar to that seen in disuse atrophy, occurs primarily in slow-twitch muscle fibers, converts muscle fibers toward the fast-fiber type, and reduces muscle mass [125]. Thus, the regulation of muscle mass and alteration of muscle fiber-type composition can occur in parallel. Although enhanced catabolic signaling changes muscle fiber composition toward a slow-fiber type and prevents muscle hypertrophy, this does not fully explain the pathophysiology described above. Recent studies have identified lncRNAs as novel players involved in the regulation of muscle fiber-types. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms of lncRNAs underlying muscle fiber-type specialization and adaptation will provide therapeutic strategies for specific diseases. In this section, we introduce the functions and molecular mechanisms of lncRNAs involved in the regulation of muscle fiber-type switching and muscle mass.

5.1. Cytor

RNA-Seq analysis of differentially expressed lncRNAs in the human vastus lateralis muscle after one-leg knee extension exercise revealed cytoskeletal regulator RNA (CYTOR) [126]. CYTOR expression increases to some extent upon endurance exercise but is more pronounced in resistance training. CYTOR does not exist near (>100 kb separation) other genes and shows nucleotide conservation in mice (annotated as Gm14005) and rats (annotated as XR_146885.3). Increased expression of Cytor was observed in both mice and rats subjected to treadmill exercise, indicating that the Cytor’s response to exercise is also conserved among species. In human and mouse myoblasts, Cytor expression increased during myogenic differentiation. Gain- and loss-of-function experiments using C2C12 cells showed that Cytor inhibits myoblast proliferation and promotes myogenic differentiation. Young mouse gastrocnemius muscles with Cytor knockdown showed a sarcopenia-like phenotype, including muscle atrophy, decreased muscle strength, and decreased composition of fast-twitch fibers (Figure 1, left panel, and Table 1). On the other hand, restoring Cytor expression, which decreased with aging, recovered muscle weight loss, and increased muscle strength and fast-type fiber composition. Interestingly, overexpression of CYTOR in myoblasts derived from aged human muscles resulted in an improved myogenic differentiation potential and increased expression of fast-twitch myosin isoforms. Mechanistically, Cytor, by binding to the Tead1 transcription factor, reduced chromatin accessibility and occupancy in the binding motif of Tead and sequestered Tead1, thereby suppressing the slow-muscle phenotype and inducing a fast-muscle phenotype. Considering that Tead transcription factors and their cofactors are known to play an important role in the composition of muscle fibers [127,128,129], manipulating CYTOR function could have therapeutic potential to increase fast-twitch fibers and attenuate muscle atrophy caused by aging in humans.

5.2. lncRNA-FKBP1C

Analysis of differentially expressed lncRNAs between the breast muscle of white recessive rock and Xinghua chickens by RNA-Seq revealed lncRNA-FKBP1C [130]. During the differentiation of chicken primary myoblasts, lncRNA-FKBP1C expression transiently increased and then decreased. In vitro overexpression and knockdown experiments revealed that lncRNA-FKBP1C inhibits the growth of chicken primary myoblasts and promotes myogenic differentiation. Moreover, lncRNA-FKBP1C drove the slow-type muscle phenotype, both in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, lncRNA-FKBP1C overexpression induced an increase in muscle fiber diameter, whereas knockdown of lncRNA-FKBP1C reversed this phenotype (Table 1). Although the detailed molecular mechanism remains unknown, lncRNA-FKBP1C binds to Myh1b protein (homologous to murine embryonic MyHC) and enhances its stability (Figure 1, left panel) [130].

5.3. SMARCD3-OT1

In chickens, lncRNA SMRCD3-OT1, which is partly overlaid on the Smarcd3x4 gene, was highly enriched in the breast and leg muscles [131]. SMARCD3-OT1 expression remained constant in chicken primary myoblasts in a proliferative state but increased after the induction of myogenic differentiation. In chickens, SMARCD3-OT1 expression increases with embryonic development and continues to be expressed in the skeletal muscle after birth. Overexpression and knockdown experiments in chicken primary myoblasts showed that SMARCD3-OT1 promoted myoblast proliferation and myotube formation at the differentiation stage. SMARCD3-OT1 also induces the expression of fast-twitch muscle fiber-related genes in myotubes. Moreover, SMARCD3-OT1 induced hypertrophy and a fast-twitch muscle fiber phenotype in chicken skeletal muscles (Table 1). Thus, SMARCD3-OT1 promotes cell proliferation and myotube formation, and can also induce fast-twitch muscle fiber-related genes in chicken primary myoblasts by increasing Smarcd3x4 expression (Figure 1, left panel) [131]. Smarcd3x4 is one of the isoforms of the evolutionarily conserved Smarcd3 gene [131], which encodes a component of the SWI/SNF complex. Therefore, investigating whether SMARCD3-OT1 and its molecular function are also evolutionarily conserved in humans is important.

5.4. ZFP36L2-AS

The ZFP36 ring finger protein-like 2 (ZFP36L2)-antisense transcript (ZFP36L2-AS) was more abundant in breast muscle than in leg muscle [132]. ZFP36L2-AS expression increased with chicken primary myoblast differentiation. ZFP36L2-AS suppressed proliferation and promoted myogenic differentiation of chicken primary myoblasts. ZFP36L2-AS also promoted glycolytic metabolism and suppressed oxidative metabolism by reducing mitochondrial function. However, these effects on cellular metabolism were not observed in adult satellite cells, suggesting the existence of a developmentally specific function for ZFP36L2-AS. Furthermore, ZFP36L2-AS knockdown in chicken skeletal muscle showed decreased expression of glycolytic metabolism-related genes, increased slow-twitch muscle fiber composition, and increased muscle mass with reduced expression of MuRF1 and Atrogin-1, suggesting that ZFP36L2-AS induces a fast-twitch muscle fiber phenotype and muscle atrophy in vivo (Figure 1, right panel, and Table 1). ZFP36L2-AS bound to the acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha (ACACA) protein and pyruvate carboxylase protein, and when ZFP36L2-AS was increased, the ACACA protein was activated with reduced phosphorylation levels, but pyruvate carboxylase was destabilized. Activated ACACA inhibits fatty acid β-oxidation and decreases pyruvate carboxylase, resulting in reduced mitochondrial function [132]. This may be one of the mechanisms underlying the induction of the fast-twitch muscle fiber phenotype by ZFP36L2-AS in chickens. ZFP36L2-AS is primarily conserved in birds [132]. Whether ZFP36L2-AS is a suitable therapeutic target for human muscle atrophy remains to be elucidated.

5.5. linc-MYH

The fast-twitch Myh genes are localized within a 300 kb region on chromosome 17 to form clusters in humans, and this genomic structure is conserved among species. Sakakibara et al. found a super-enhancer for fast-twitch Myh genes, 50 kb upstream of Myh2 [133], and linc-MYH is located 4 kb downstream of the super-enhancer [133]. linc-MYH is specifically expressed in fast-twitch skeletal muscles and accumulates in the nuclei of adult mice. In vivo knockdown experiments using shRNAs showed that a decrease in linc-MYH expression was accompanied by a decrease in the expression of fast-twitch muscle fiber-related genes and an increase in the expression of slow-twitch muscle fiber-related genes. Conversely, forced expression of linc-MYH in slow-type muscle by in vivo transfection induced the fast-twitch gene Myh4. However, it was later reported that mice lacking linc-MYH showed a myofiber-type distribution similar to that of wild-type mice [134]. In addition, linc-MYH knockout mice had a larger pool of satellite cells than wild-type mice. The loss of linc-MYH may strengthen the association of chromatin remodeling proteins, including INO80, YY1, WDR5, and TFPT, leading to an increase in satellite cells. Moreover, in mice lacking the super-enhancer of fast-twitch MyHC genes, no clear change in myofiber-type distribution in distal hindlimb muscles was observed, whereas linc-MYH expression was lost [135], indicating that further studies are required to determine the function of linc-MYH in the regulation of myofiber-type distribution. Interestingly, linc-MYH knockout mice showed a muscle hypertrophy phenotype with increased muscle weight (Figure 1, right panel, and Table 1) [134]. We found linc-MYH expression was largely decreased in conditions of muscle atrophy induced by denervation, cast immobilization, fasting, and cancer cachexia [89]. Thus, decreased linc-Myh expression may be associated with the pathogenesis of muscle atrophy.

5.6. SMUL

Integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analyses identified 104 micropeptides translated from lncRNAs with altered expression during myogenic differentiation of chicken myoblasts [136]. SMAD-specific E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (Smurf2) upstream lncRNA (SMUL) was one of the identified lncRNA-encoded micropeptides and was highly expressed in skeletal muscle tissues. SMUL expression was downregulated during chicken myoblast differentiation. Gain- and loss-of-function experiments showed that SMUL promotes myoblast proliferation and inhibits myogenic differentiation. In chicken skeletal muscle, SMUL induced muscle atrophy and activated switching from slow- to fast-twitch myofiber. Mechanistically, SMUL mediated the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay of Smurf2, which downregulates TGF-β signaling (Figure 1, right panel) [137]. Overexpression of Smurf2 induced muscle hypertrophy, whereas Smurf2 knockdown led to muscle atrophy (Table 1). Thus, SMUL reduced skeletal muscle mass by enhancing TGF-β signaling via Smurf2 stability. Given that myostatin and activin, members of the TGF-β superfamily, negatively regulate skeletal muscle mass and that Smurf2 is involved in their signaling [138], this mechanism can partly explain the effect of SMUL. However, it is unclear why the enhanced TGF-β signaling by SMUL stimulated the slow-to-fast fiber switch because depletion of myostatin, which is highly similar to TGF-β signaling, results in increased fast-twitch myofibers [139].

Table 1.

The Summary of lncRNAs involved in the regulation of skeletal muscle mass. Data are based on the in vivo experimental results, but partially include in vitro experiments for ceRNAs. ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; C.C., cancer cachexia; CKD, chronic kidney disease; Den, denervation; Dex, dexamethasone treatment; H.S., hindlimb suspension; S.M., skeletal muscle.

Table 1.

The Summary of lncRNAs involved in the regulation of skeletal muscle mass. Data are based on the in vivo experimental results, but partially include in vitro experiments for ceRNAs. ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; C.C., cancer cachexia; CKD, chronic kidney disease; Den, denervation; Dex, dexamethasone treatment; H.S., hindlimb suspension; S.M., skeletal muscle.

| Name | Expression Changes by | Experiments in | Methods | For S.M. Mass | Function | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AK017368 | - | Mouse | siRNA-mediated knockdown | Negative | Sponge for miRNA | [119] |

| Atrolnc-1 | C.C., CKD, Dex, Fasting | Mouse | AAV-mediated overexpression shRNA-mediated knockdown | Negative | Transcriptional regulation | [91] |

| Charme | - | Mouse | Genetic knockout | Positive | Transcriptional regulation | [71] |

| Chronos | Aging | Mouse | siRNA-mediated knockdown | Negative | Transcriptional regulation | [90] |

| Cytor | Aging | Mouse | AAV-mediated overexpression, Gapmer-mediated knockdown | Positive | Transcriptional regulation | [126] |

| H19 | Den, Fasting | Mouse | Genetic knockout | Negative | Source of miR-675-5p & miR-675-3p Dystrophin stability | [62,108,109] |

| linc-MYH | C.C., Den, Fasting, Immobilization | Mouse | Genetic knockout | Negative | Regulation of satellite cell pool | [134] |

| linc-RAM | - | Mouse | Genetic knockout | Positive | Micropeptide Transcriptional regulation | [79,80] |

| LncEDCH1 | - | Chicken | Lentiviral-mediated overexpression Lentiviral-mediated knockdown | Positive | SERCA2 activity | [99] |

| lncIRS1 | - | Chicken | Lentiviral-mediated overexpression Lentiviral-mediated knockdown | Positive | Sponge for miRNA | [115] |

| lncMAAT | Aging, Angiotensin II infusion, Den, Fasting, Immobilization | Mouse | Lentiviral-mediated overexpression Lentiviral-mediated knockdown | Positive | Transcriptional regulation | [94] |

| lnc-mg | Fasting | Mouse | Transgenic overexpression Genetic knockout | Positive | Sponge for miRNA | [110] |

| lncMGPF | - | Mouse | Lentiviral-mediated overexpression Genetic knockout | Positive | Sponge for miRNA mRNA stability | [83] |

| lncMUMA | H.S. | Mouse | Lentiviral-mediated overexpression | Positive | Sponge for miRNA | [116] |

| lnc-ORA | Aging | Mouse | AAV-mediated overexpression | Negative | Sponge for miRNA mRNA stability | [122] |

| lncRNA-FKBP1C | - | Chicken | Lentiviral-mediated overexpression Lentiviral-mediated knockdown | Positive | Protein stability | [130] |

| lnc-SEMT | - | Sheep | Transgenic overexpression shRNA-mediated knockdown | Positive | Sponge for miRNA | [114] |

| MAR1 | Aging, Fasting, H.S. | Mouse | Transgenic overexpression shRNA-mediated knockdown | Positive | Sponge for miRNA | [117] |

| Myoparr | Den | Mouse | shRNA-mediated knockdown | Negative | Transcriptional regulation | [57,68] |

| Neat1 | Den, Dex, H.S., Immobilization | Mouse | Lentiviral-mediated knockdown | Negative | Transcriptional regulation | [74] |

| Pvt1 | Den, ALS | Mouse | Gapmer-mediated knockdown | Negative | Mitochondrial network regulation | [97] |

| SMARCD3-OT1 | - | Chicken | Lentiviral-mediated overexpression ASO-mediated knockdown | Positive | Transcriptional regulation | [131] |

| SMUL | - | Chicken | Lentiviral-mediated overexpression Lentiviral-mediated knockdown | Negative | mRNA decay | [136] |

| SYISL | - | Mouse | Genetic knockout Lentiviral-mediated overexpression Lentiviral-mediated knockdown | Negative | Sponge for miRNA | [112,113] |

| TCONS-00036665 | - | Mouse | Lentiviral-mediated knockdown | Negative | - | [77] |

| ZFP36L2-AS | - | Chicken | Lentiviral-mediated knockdown | Negative | - | [132] |

6. Therapeutic Potential and Limitations of lncRNAs for Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in Humans

As described above, lncRNAs are potential therapeutic targets in human muscle atrophy and wasting disorders. However, several issues must be resolved before they can be applied to human therapy. First, even if the existence of corresponding lncRNAs among different species including humans is confirmed, the nucleotide sequences of lncRNAs are not generally well conserved compared to functional proteins [140]. Although they can alleviate muscle atrophy in mice and other vertebrates, whether their human counterparts have similar molecular functions in muscle mass remains unclear. Therefore, their applicability for treating muscle atrophy in humans must be carefully considered. The second issue is that optimal methods for controlling the expression or function of lncRNAs in human skeletal muscle have not been established. As mentioned above, increasing or decreasing the expression levels of lncRNAs is effective in regulating their functions. However, nucleic acid-based technologies, which have been applied to many mRNAs in the past, have shown limited progress in the treatment of human diseases [141]. Virus-vector-based technologies, which have been available for practical use in the last few years as COVID-19 vaccines [142], should be considered for lncRNA therapy in the future. In recent years, a small molecule-based inhibitor for Xist lncRNA has been developed [143]; therefore, the application of such a method may also be considered for other lncRNAs. The third issue is the complexity of the pathogenic factors of muscle atrophy [15], and lncRNAs, which function across the entire spectrum of muscle atrophy caused by cancer cachexia, disuse, fasting, and aging, have not yet been elucidated. Therefore, it is important to identify the cause of muscle atrophy and target appropriate lncRNAs.

Telomeres protect the ends of chromosomes from damage and a shortening of telomere length is known as a hallmark of cellular senescence. Telomere length is regulated by two lncRNAs, telomerase RNA component (TERC) and telomeric repeat-containing RNA (TERRA) [144]. Decreased TERRA expression in leukocytes is associated with sarcopenia [145]. Besides, H19 impedes the function of telomerase, which extends the length of telomeres, in human acute promyelocytic leukemia cells [146]. Although whether the differences in telomere length are associated with sarcopenia is not conclusive [145,147,148,149], leukocyte telomere length is associated with a life span limit among humans [150]. In addition, genetic factors associated with longevity are being explored [151,152]; therefore, more detailed analysis of telomere-associated lncRNAs in skeletal muscles or research on lncRNAs associated with longevity could lead to identifying the new therapeutic targets for sarcopenia.

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

There are no lncRNAs in advanced clinical trial phases for skeletal muscle atrophy yet, but this may be because it has only been a decade since biological attention was focused on the pleiotropic functions of lncRNAs. Recent characterization has elucidated the association of lncRNAs with muscle atrophy. Thus, while many issues remain to be resolved, lncRNAs will become effective targets for skeletal muscle atrophy in the near future, leading to the development of therapeutic agents. We have high hopes that it will be possible to overcome human muscle atrophy using cutting-edge technologies related to new frontiers of lncRNAs.

Author Contributions

K.H., M.H. and K.T. wrote and edited the manuscript. K.H. designed the figures. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (19H03427 and 20K07315).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gao, Y.; Arfat, Y.; Wang, H.; Goswami, N. Muscle atrophy induced by mechanical unloading: Mechanisms and potential countermeasures. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picot, J.; Hartwell, D.; Harris, P.; Mendes, D.; Clegg, A.; Takeda, A. The effectiveness of interventions to treat severe acute malnutrition in young children: A systematic review. Health Technol. Asses. 2012, 16, 1–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otzel, D.M.; Kok, H.J.; Graham, Z.A.; Barton, E.R.; Yarrow, J.F. Pharmacologic approaches to prevent skeletal muscle atrophy after spinal cord injury. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2021, 60, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohm, M.; Zeigerer, A.; Machado, J.; Herzig, S. Energy metabolism in cachexia. EMBO Rep. 2019, 20, e47258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Palus, S.; Springer, J. Skeletal muscle wasting in chronic heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2018, 5, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, C.; Manzano, R.; Vaz, R.; Osta, R.; Brites, D. Synaptic failure: Focus in an integrative view of ALS. Adv. Neurol. 2016, 1, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oliveira, E.A.; Cheung, W.W.; Toma, K.G.; Mak, R.H. Muscle wasting in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2018, 33, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreiro, E.; Jaitovich, A. Muscle atrophy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Molecular basis and potential therapeutic targets. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 1, S1415–S1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Haehling, S.; Anker, S.D. Cachexia as a major underestimated and unmet medical need: Facts and numbers. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2010, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larsson, L.; Degens, H.; Li, M.; Salviati, L.; Lee, Y.I.; Thompson, W.; Kirkland, J.L.; Sandri, M. Sarcopenia: Aging-related loss of muscle mass and function. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 427–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wan, C.S.; Ktoris, K.; Reijnierse, E.M.; Maier, A.B. Sarcopenia is associated with mortality in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontology 2022, 68, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, M.N.; Eggelbusch, M.; Naddaf, E.; Gerrits, K.H.L.; van der Schaaf, M.; van den Borst, B.; Wiersinga, W.J.; van Vugt, M.; Weijs, P.J.M.; Murray, A.J.; et al. Skeletal muscle alterations in patients with acute COVID-19 and post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, M.; Kimura, Y.; Ishiyama, D.; Otobe, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Koyama, S.; Kikuchi, T.; Kusumi, H.; Arai, H. The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and new incidence of frailty among initially non-frail older adults in Japan: A follow-up online survey. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.R.; Sudati, I.P.; Konzen, V.D.M.; de Campos, A.C.; Wibelinger, L.M.; Correa, C.; Miguel, F.M.; Silva, R.N.; Borghi-Silva, A. COVID-19 and the impact on the physical activity level of elderly people: A systematic review. Exp. Gerontol. 2022, 159, 111675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartori, R.; Romanello, V.; Sandri, M. Mechanisms of muscle atrophy and hypertrophy: Implications in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, H.; Kawakami, R.; Honda, T.; Sawada, S.S. Muscle-strengthening activities are associated with lower risk and mortality in major non-communicable diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latres, E.; Amini, A.R.; Amini, A.A.; Griffiths, J.; Martin, F.J.; Wei, Y.; Lin, H.C.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Glass, D.J. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) inversely regulates atrophy-induced genes via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/Akt/mTOR) pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 2737–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoshida, T.; Delafontaine, P. Mechanisms of IGF-1-mediated regulation of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. Cells 2020, 9, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodine, S.C.; Latres, E.; Baumhueter, S.; Lai, V.K.-M.; Nunez, L.; Clarke, B.A.; Poueymirou, W.T.; Panaro, F.J.; Na, E.; Dharmarajan, K.; et al. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science 2001, 294, 1704–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, M.; Sandri, C.; Gilbert, A.; Skurk, C.; Calabria, E.; Picard, A.; Walsh, K.; Schiaffino, S.; Lecker, S.H.; Goldberg, A.L. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell 2004, 117, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stitt, T.N.; Drujan, D.; Clarke, B.A.; Panaro, F.; Timofeyva, Y.; Kline, W.O.; Gonzalez, M.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Glass, D.J. The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Mol. Cell 2004, 14, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiaffino, S.; Dyar, K.A.; Ciciliot, S.; Blaauw, B.; Sandri, M. Mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle growth and atrophy. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 4294–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherron, A.C.; Lawler, A.M.; Lee, S.-J. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature 1997, 387, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherron, A.C.; Lee, S.-J. Double muscling in cattle due to mutations in the myostatin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 12457–12461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mosher, D.S.; Quignon, P.; Bustamante, C.D.; Sutter, N.B.; Mellersh, C.S.; Parker, H.G.; Ostrander, E.A. A mutation in the myostatin gene increases muscle mass and enhances racing performance in heterozygote dogs. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3, e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, J.; Carpio, Y.; Borroto, I.; González, O.; Estrada, M.P. Myostatin gene silenced by RNAi show a zebrafish giant phenotype. J. Biotechnol. 2005, 119, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiello, D.; Patel, K.; Lasagna, E. The Myostatin Gene: An overview of mechanisms of action and its relevance to livestock animals. Anim. Genet. 2018, 49, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Japan Embraces CRISPR-edited fish. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 10. [CrossRef]

- Schuelke, M.; Wagner, K.R.; Stolz, L.E.; Hübner, C.; Riebel, T.; Kömen, W.; Braun, T.; Tobin, J.F.; Lee, S.-J. Myostatin mutation associated with gross muscle hypertrophy in a child. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2682–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.-J. Targeting the myostatin signaling pathway to treat muscle loss and metabolic dysfunction. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e148372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latres, E.; Mastaitis, J.; Fury, W.; Miloscio, L.; Trejos, J.; Pangilinan, J.; Okamoto, H.; Cavino, K.; Na, E.; Papatheodorou, A.; et al. Activin A more prominently regulates muscle mass in primates than does GDF8. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.-J. Regulation of muscle mass by myostatin. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004, 20, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schakman, O.; Kalista, S.; Barbé, C.; Loumaye, A.; Thissen, J.P. Glucocorticoid-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 45, 2163–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandri, M. Protein breakdown in muscle wasting: Role of autophagy-lysosome and ubiquitin-proteasome. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 45, 2121–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sandri, M.; Coletto, L.; Grumati, P.; Bonaldo, P. Misregulation of autophagy and protein degradation systems in myopathies and muscular dystrophies. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 5325–5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esteller, M. Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]