Abstract

The research and development of new accident-tolerant fuel cladding materials has emerged as a critical focus in international academic and engineering fields following the Fukushima nuclear accident. Due to the outstanding resistances in corrosion and radiation as well as high-temperature creep properties, oxide dispersion-strengthened (ODS) FeCrAl alloys have been studied extensively during the past decade. Current review articles in this field have primarily focused on the effects of chemical composition on the anti-corrosion performance and species of nano-oxide. However, several key issues have not been given adequate attention, including processing methods and parameters, high-temperature stability mechanisms, post-deformation microstructural evolution and high-temperature mechanical properties. This paper reviews the progress of basic research on ODS FeCrAl alloys, including preparation methods, the effects of preparation parameters, the thermal stability and irradiation stability of oxides, the microstructural deformation, and the mechanical properties at elevated temperatures. The aspects mentioned above not only provide valuable references for understanding the effects of preparation parameters on the microstructure and properties of ODS FeCrAl alloys but also offer a comprehensive framework for the subsequent optimization of ODS FeCrAl alloys for nuclear reactor applications.

1. Introduction

Since the start of the 21st century, global electricity consumption has experienced steady growth, while energy supply constraints and ecological conservation demands have emerged as dual challenges. In this context, the international community has increasingly prioritized nuclear energy over traditional fossil fuels. Recognized for its distinct low-carbon characteristics and superior energy conversion efficiency, nuclear power is now considered one of the most viable alternatives to fossil fuel-based energy systems.

The history of nuclear power development dates back more than sixty years. However, the profound negative impacts of nuclear accidents on humanity and the environment have made nuclear safety a global focus of concern. For instance, in the 1990s, following the accidents at the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl nuclear power plants, countries such as the United States, European nations, and Japan have actively pursued research and tackled key issues to develop derived third-generation reactors for preventing and mitigating serious accidents. Relative to the second-generation nuclear power units involved in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster on 11 March 2011, mainstream third-generation nuclear power units have demonstrated significant safety improvements. To improve the accident tolerance of light water reactors (LWRs), a pivotal technical strategy involves material innovation in the conventional Zircaloy-clad UO2 fuel system. The new material configurations must maintain operational performance equivalent to that of the existing system across three critical metrics: burnup, power density, and enrichment level, while replacing zirconium-based cladding with advanced oxidation-resistant cladding materials to significantly improve core safety under extreme operating conditions. Although the integrated response of the fuel-cladding system dominates LWR accident progression, the implementation of accident-tolerant cladding materials allows for the effective control of accident development rates and modifies the severity of consequences. These material properties provide dual safety benefits: reducing the operational demands on engineered safety systems while extending the time windows for mitigation, thereby substantially improving the safety margins of nuclear power plant systems [1]. Furthermore, the development of accident-tolerant fuel cladding is critical for operation in the high-burnup conditions of Generation IV nuclear reactor systems, such as the supercritical water-cooled reactor (SCWR) and the lead-cooled fast reactor (LFR). Following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident, enhancing severe accident safety margins has become a major focus of R&D (research and development). In response, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) launched a research program on accident-tolerant fuels (including both fuel pellets and cladding materials) [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

Fuel cladding, which serves as the sealed containment for nuclear fuel, constitutes the most critical safety barrier in nuclear power plants. Its primary functions include preventing the release of fission products, protecting the fuel from coolant corrosion, and efficiently transferring thermal energy. The fuel cladding faces challenges such as high-temperature burnup, intense radiation exposure, and coolant compatibility issues due to the extreme operating conditions in nuclear reactors. Therefore, fuel cladding materials must possess superior comprehensive performance to meet these challenges:

(1) High thermal conductivity coupled with a low thermal expansion coefficient;

(2) Small neutron absorption cross-section coupled with low induced radioactivity, short radioactive half-life, and excellent radiation resistance;

(3) Good fuel–coolant compatibility (demonstrating excellent corrosion resistance);

(4) High strength, good ductility, and exceptional high-temperature toughness.

Extensive studies indicate that superior oxidation resistance is generally achieved through the formation of Cr2O3, Al2O3, or SiO2 layers on structural materials or coatings containing Cr, Al, and Si when exposed to air at temperatures above 600 °C [11]. Consequently, coated zirconium-based cladding, ferritic alumina-forming alloys, and silicon carbide fiber-reinforced silicon carbide matrix composites are considered the leading candidate materials for accident-tolerant fuel cladding [12]. Long-term exposure tests (>1000 h) in dry air demonstrate that Cr2O3 provides effective protection up to 1000 °C, Al2O3 maintains resistance up to 1400 °C, and SiO2 exhibits stable performance up to 1700 °C (note that the actual temperature limits depend on the thickness of the material, exposure conditions, and design lifetime). However, the reactor core environment may contain either steam or a steam–hydrogen mixture under severe accident conditions. In high-temperature steam environments, Cr2O3 and SiO2 oxide scales may form volatile hydroxides, thereby reducing their operational temperature limits by several hundred degrees Celsius compared to the limits observed in dry air [13]. Under high-pressure steam conditions, researchers evaluated the oxidation resistance of SiC-based materials and high-Cr–Al stainless steels over the temperature range of 800~1200 °C. The results demonstrated that FeCrAl alloys exhibited extremely low reaction kinetics at temperatures up to 1200 °C, whereas Fe–Cr alloys with 15~20 wt.% Cr experienced corrosion at significantly higher rates [14]. Therefore, regarding corrosion resistance at ultra-high temperatures (T > 1000 °C), FeCrAl-based alloys are recognized as the most promising candidate material for accident-tolerant fuel cladding in light-water nuclear reactors [15,16].

Oxide dispersion-strengthened (ODS) alloys exhibit a strong pinning effect on both dislocation movement and grain boundary motion because of their ultra-high density of dispersed nano-scale oxides [17,18,19], resulting in a significant enhancement of the material’s high-temperature strength [20]. These high-density nano-oxides also promote the recombination of irradiation-induced point defects, including vacancies and self-interstitial atoms, thus effectively mitigating radiation damage [21].

ODS FeCrAl alloys, which combine the superior high-temperature mechanical properties [22,23] and radiation resistance [24,25,26,27,28] of ODS Fe–Cr alloys with the excellent corrosion resistance of FeCrAl alloys, represent a highly promising solution to accident-tolerant structural material requirements in nuclear energy systems. These alloys are particularly suitable for Generation II/III light-water reactors (LWRs), Generation IV supercritical water-cooled reactors (SCWRs), and lead-cooled fast reactors (LFRs) that use liquid lead alloys as coolants [29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

Based on the application background of ODS FeCrAl alloys [36,37,38,39,40], the fundamental principles of their chemical composition design were reviewed, with particular emphasis on the influence mechanisms of alloying element selection and concentration on their corrosion resistance, radiation resistance, microstructural evolution, and mechanical properties [41]. This review provides a critical assessment of ODS FeCrAl alloy developments, examining the following:

- (1)

- Advanced synthesis techniques;

- (2)

- Process-structure-property relationships;

- (3)

- Multifunctional roles of nano-dispersoids in

- Thermal stabilization;

- Radiation damage mitigation;

- Mechanical performance enhancement;

- (4)

- Deformation-induced microstructural evolution.

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of this review, enabling readers to readily grasp the key aspects of our discussion. The research findings across these domains summarized in the figure provide crucial references for optimizing the preparation processes, controlling microstructure and properties, and improving the evaluation means and experimental design parameters of ODS FeCrAl alloys.

Figure 1.

Frame diagram of the review.

Powder metallurgy technologies are the main methods for fabricating ODS FeCrAl alloys due to the inability of yttrium (Y2O3) to dissolve into the matrix via conventional melting techniques [42]. This review systematically examines the main preparation processes, including mechanical alloying (MA), hot isostatic pressing (HIP), hot extrusion (HE), and spark plasma sintering (SPS), while summarizing the influence mechanisms of MA parameters and hot consolidation parameters on the alloy’s microstructure and mechanical properties. The thermal stability of characteristic oxide phases (Y–Ti–O, Y–Al–O, and Y–Zr–O) in ODS FeCrAl alloys under both intermediate (300~650 °C) and ultra-high temperature (800~1400 °C) conditions, along with their irradiation stability below 800 °C, were systematically reviewed. Microstructural evolution during plastic deformation was comprehensively analyzed, encompassing texture development, recrystallization behavior, and oxide–matrix interactions. Finally, as a promising accident-tolerant candidate material, the critical high-temperature mechanical properties of ODS FeCrAl alloys—particularly tensile and creep behaviors—were thoroughly evaluated.

2. Powder Metallurgy Manufacturing Process

Owing to the differential density, melting point, and thermal conductivity of the strengthening phase relative to the steel matrix, it is difficult to fabricate oxide dispersion-strengthened (ODS) steel using traditional casting processes. Casting methods often result in an inhomogeneous microstructure, thereby degrading the mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of the material. Research indicates that the powder metallurgy (PM) route is a feasible alternative. The general PM process for manufacturing ODS steel consists of mechanical alloying (MA) using gas-atomized pre-alloyed powder or pure metal powder, consolidation, and thermal–mechanical treatment. The primary consolidation methods include hot isostatic pressing (HIP), hot extrusion (HE), and spark plasma sintering (SPS) [42]. This section reviews the effects of preparation process parameters on the microstructure and properties of ODS Fe–Cr (ODS FeCrAl) alloys.

2.1. Mechanical Alloying

Mechanical alloying (MA) is a manufacturing method in which metal or alloy powders are subjected to intense impact, collision, friction, and shear by ball milling media for an extended period in a ball mill. This results in severe plastic deformation of the powder particles, along with repeated cold welding and fracture. The general method for preparing ODS Fe–Cr (ODS FeCrAl) alloys involves the mechanical grinding of oxide powder particles (such as Y2O3 nanopowder) and powder particles of various constituent elements in a high-energy ball mill under an argon atmosphere at room temperature for a prolonged duration, according to the predetermined ratio [43,44,45,46].

Figure 2 presents a schematic diagram of the main types of ball mills, including attritor and planetary configurations. During mechanical alloying (MA), atoms of various alloying elements diffuse and become forcibly dissolved into the matrix, effectively enhancing their solid solubility. This process enables the production of alloy powders featuring a supersaturated solid solution structure. Compared with mechanical mixing, MA-derived powders demonstrate distinct advantages: finer oxide particles, more uniform distribution, and superior dispersion strengthening effects. The MA process effectively overcomes critical limitations inherent to conventional mechanical mixing methods, such as particle agglomeration and compositional segregation. Consequently, MA has emerged as the predominant technique for synthesizing advanced non-equilibrium materials (e.g., amorphous alloys, nanocrystalline phases, and supersaturated solid solutions) that exhibit exceptional structural homogeneity and tunable properties.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of mechanical alloying.

Mechanical alloying (MA) technology is a key step to study the formation mechanism of nano-oxides in ODS alloys. MA parameters, such as the variety of ball milling, milling time, rotation rate and milling atmosphere, etc., significantly affect the energy input intensity, thus affecting the crushing and dissolution of Y2O3 initially added [47].

During the mechanical alloying process for preparing ODS FeCrAl alloys, the average particle size of powder gradually decreases with increasing milling time and eventually stabilizes [48,49,50,51]. Regarding the microstructure within alloy powders, Chen et al. [48] investigated mechanically alloyed powders using a SPEX 8000 ball mill (a three-dimensional vibration ball mill). As shown in Figure 3, the crystallite size progressively decreases (reaching approximately 11 nm after 15 h of milling), while the lattice distortion increases (to ~0.47% after 15 h milling) with extended milling time. These results demonstrate that the mechanical alloying technique not only refines the powder but also induces significant lattice strain, thereby increasing dislocation density within the powder crystals. In contrast, when using a planetary ball mill, the lower energy input compared to the SPEX 8000 mill requires a longer duration to reach saturation. As reported in reference [49], the lattice parameter of body-centered cubic iron (bcc-Fe) increases rapidly during the initial 12 h milling period, reaching saturation after 48 h of mechanical alloying. Furthermore, compared to ball milling in an air atmosphere, processing under a pure argon (Ar) atmosphere effectively minimizes excessive oxygen content (generally considered contamination) in mechanically alloyed (MA) powders and solidified alloys, thereby improving the mechanical properties of consolidated alloys [49].

Figure 3.

Crystallite size and lattice distortion of Fe–Cr–Al–Ti–Y2O3 powders milled as a function of milling time [48].

The relationship between the ball milling duration and mechanical properties in ODS alloys is governed by a critical balance: extended ball milling time enables effective grain refinement and enhances elevated-temperature tensile strength provided that (i) alloying elements achieve complete dissolution and saturation, and that (ii) contamination (e.g., oxygen pickup) is rigorously suppressed [52].

Debate about the existing form of Y2O3 particles initially added in the milled powder has been initiated in previous studies. For example, Alinger et al. [18] suggested that Y and O were completely dissolved in the MA process, and oxide particles were precipitated in the HIP process of 14-YWT. However, Brocq et al. [53] observed that after mechanical alloying (MA), fine Y–Ti–O clusters directly formed in an alloy with a composition similar to the 14-YWT, and further nucleation and growth occurred during subsequent annealing at a relatively low temperature (<800 °C) for as short as 5 min. Hsiung et al. [54] proposed that the formation of oxide particles in ODS steel includes three main stages: (1) in the early stage of ball milling, the initial Y2O3 powder particles are broken to form fine dispersed nano-fragments; (2) in the later stage of ball milling, the fragments mixed with the matrix components are agglomerated and amorphous, and thus form amorphous aggregates and clusters ([MYO], M: Fe, Cr, Al, W, and Ti); (3) during the consolidation process, amorphous aggregates larger than the critical size (~2 nm) crystallize to form oxide nanoparticles with complex oxide cores and solute rich shells [55]. Liu et al. [56] observed the mechanical alloyed powder after ball milling for 48 h and found that amorphous Y–O was formed at the grain boundary (i.e., low-energy region). He et al. [54] observed using transmission electron microscope (TEM) and X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) that a small amount of Y2O3 dissolved in the steel matrix after 24 h of ball milling. Y was enriched at the edge of the particle, which was similar to the results observed by Liu et al. [56], while the powder milled for 80 h showed invisible Y segregation/agglomeration.

The results above reveal that the fragmentation and dissolution of the added Y2O3 are strongly reliant on milling time. With continuous advancements in characterization methodologies and breakthroughs in instrumental resolution, the intricate mechanisms underlying mechanical alloying (MA) processes and their consequent impacts on oxide characteristics (including phase composition, dimensional parameters, and crystallographic configurations) are expected to be systematically elucidated.

2.2. Hot Isostatic Pressing

Hot isostatic pressing (HIP) is currently the primary method used in laboratory research [57,58,59,60]. The HIP process parameters, such as pressure, temperature, and holding time, significantly influence the properties of ODS alloys. Each of these parameters can be adjusted to control specific performance characteristics of the alloy.

For example, HIP pressure has a remarkable influence on the alloy’s relative density. The homogeneity of densification can be assessed by the trend in microhardness variation: the lower the relative density of the compacted material, the lower the measured microhardness values. In ODS RAF steel [61], applying a HIP pressure of 200 MPa at 1150 °C for 3 h resulted in a relative density exceeding 99% of the theoretical value. Similarly, increasing the pressure to 210 MPa and extending the holding time to 4 h (at the same temperature) achieved a relative density of 99.8%, nearly matching the theoretical maximum.

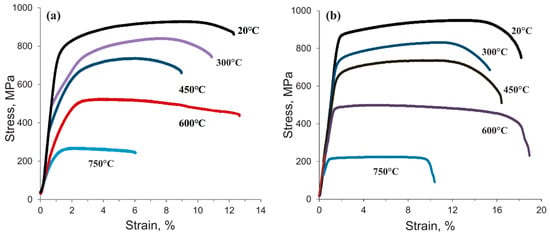

Oksiuta et al. [62] systematically studied the effects of HIP pressure on the microstructure, high-temperature tensile properties, and microhardness of the alloy. Specimens were processed by HIP at 1150 °C for 3 h under varying pressures of 185 MPa, 200 MPa, 215 MPa, and 300 MPa. Microstructural analysis revealed a positive correlation between HIP pressure (185~300 MPa) and relative density, although incomplete pore closure was observed even at the maximum applied pressure of 300 MPa. Mechanical testing indicated that consolidation pressures above 200 MPa had negligible effects on the hardness and tensile strength of oxide dispersion-strengthened (ODS) steel, while significantly improving the ductility of material, as detailed in Figure 4 [62]. These results demonstrate that consolidation pressure critically governs both the densification behavior and ductility of the material.

Figure 4.

Tensile properties of ODS ferritic steel as a function of testing temperature: (a) HIPped under the pressure of 200 MPa. (b) HIPped under the pressure of 300 MPa [62].

The consolidation temperature also exerts a pronounced influence on the morphology of precipitate phases. As the consolidation temperature increases from 850 °C to 1150 °C, the number density and volume fraction of oxides decrease, while their radius increases [18]. However, a HIP consolidation temperature above 1000 °C results in fully densified ODS alloys, thereby improving fracture toughness [63].

Based on previous studies, the typical HIP preparation parameters for ODS FeCrAl are as follows: 1100~1150 °C, 150~200 MPa, 2~4 h [64,65,66]. To further improve alloy densification and mechanical properties, thermomechanical processing (TMP) combining deformation and heat treatment is typically applied to the as-fabricated alloys. This includes cold rolling [61], hot rolling [67,68], forging [69,70,71,72,73], high-speed hydrostatic extrusion (HSHE) [74,75], and other deformation treatments, followed by stress relief annealing.

2.3. Hot Extrusion

The hot extrusion (HE) process is widely used for the large-scale industrial production of ODS alloys, such as MA956, PM2000, and MA957 [76]. Compared to HIP, HE-processed ODS steels exhibit finer grain sizes. The advantage of this process lies in its ability to produce a more uniform and pore-free microstructure due to the shorter processing time required for hot extrusion [76,77,78]. This microstructural refinement enhances material properties, particularly by significantly reducing the ductile-to-brittle transition temperature (DBTT).

The key HE (hot extrusion) parameters affecting the performance of ODS steel mainly include the hot extrusion temperature, extrusion ratio, extrusion die shape, and heating time. The microstructure is sensitive to the extrusion temperature. Hoelzer et al. [79] investigated the influence of different extrusion temperatures (e.g., 850 °C, 1000 °C, and 1150 °C) on the microstructure and mechanical properties of a 14YWT ODS alloy. The results indicated that as the hot extrusion temperature increased, the average size of nanoclusters increased, while their number density decreased. Additionally, the average grain size increased with higher hot extrusion temperatures. Samples extruded at 1150 °C exhibited excellent strength and ductility. Similar trends were observed in ODS FeCrAl alloys extruded at temperatures of 1050 °C and 1150 °C [80]. For example, Massey et al. [52] prepared an ODS FeCrAl 106ZY alloy using hot extrusion temperatures of 900 °C, 1000 °C, and 1050 °C. A controlled reduction in extrusion temperature promotes grain refinement within the ODS FeCrAl 106ZY alloy system, effectively enhancing fracture toughness.

In addition, thermomechanical processing during hot extrusion develops pronounced crystallographic texture in ODS steels. This texture-induced anisotropy critically determines mechanical anisotropy, particularly degrading transverse ductility [81,82]. During sustained reactor operation, the progressive accumulation of gaseous fission products increases the internal pressure of cladding tubes; consequently, the major stress component will be applied in the transverse direction [83]. The degree of anisotropy (measured by grain aspect ratio) depends on the extrusion ratio. Morris et al. [84] investigated the crystallographic texture in powder-compacted ODS FeCrAl alloys and concluded that compositional changes hardly affect the resulting texture, while reducing the extrusion ratio produces weakly textured, nearly isotropic materials. Currently, laboratory-prepared ODS FeCrAl alloys typically use circular extrusion dies with an extrusion ratio of approximately 4.7 [52,85].

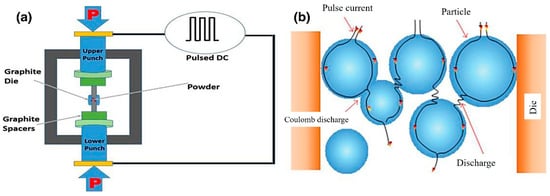

2.4. Spark Plasma Sintering

Spark plasma sintering (SPS), as a non-equilibrium processing technique, has attracted considerable research interest in recent years. Due to the short sintering time, high compactness, and low sintering temperature [86], the grain size remains in the nanometer range. A schematic of the SPS process is shown in Figure 5 [87]. The effectiveness of SPS technology relies on the phenomenon of electric spark discharge. A pulsed current is utilized to generate plasma and increase the temperature at the contact points of the powder. The SPS consolidation process is achieved through the activation and melting of powder surfaces, neck formation at powder contact points, and atomic diffusion, as well as the plastic flow of the sintered billet [86,88].

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of SPS principle: (a) a schematic of the SPS process; (b) DC pulse current flow through the particles [87].

The favorable sintering conditions of SPS, such as the sintering temperature, pressure, and heating rate, significantly impact the properties of the alloy. Regarding sintering temperature, it strongly influences the densification during the SPS consolidation process. Dash et al. [89] consolidated the milled powder via SPS in the temperature range of 1273~1423 K (1000~1150 °C) at 50 K intervals under a pressure of 40 MPa. The results show that the densification rate increases with the temperature, indicating that higher temperatures provide more thermal energy, thereby accelerating diffusion and sintering processes, ultimately achieving higher relative density. However, the densification rate did not increase significantly above 1323 K (1050 °C). At each temperature, densification reaches a maximum value, beyond which the densification rate does not increase over time. The author explained the reason for the variation in densification rate (from rapid to slow) from the perspective of surface energy.

Although hot working (deformation + heat treatment) positively influences the mechanical properties of samples prepared under lower SPS pressures [90,91,92], employing higher SPS pressures enables direct production of the as-sintered samples with enhanced mechanical properties without requiring post-processing heat treatment, thereby simplifying the manufacturing process. For example, Allahar et al. [93] consolidated Fe-16Cr-3Al (wt%) powder using SPS and investigated the effects of sintering conditions on the relative density, microstructure, and hardness of the sintered ODS alloy. They recommended applying pressures exceeding 80 MPa to improve density since higher sintering temperatures and prolonged sintering durations at 80 MPa failed to increase the relative density beyond 97.5%. Boulnat et al. [94] fabricated a Fe-14Cr-1W-TiH2-Y2O3 ODS alloy using high sintering pressure (76 MPa) and an extremely fast heating rate (300 °C/min) to minimize porosity. After sintering at 1373 K (1100 °C) for 5 min, the nano-oxide particles exhibited uniform size distribution and high number density. The yield strengths were 975 MPa at room temperature and 298 MPa at 923 K (650 °C), respectively (as shown in Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Tensile properties under axial (plain lines) and radial (dash lines) directions at room and high temperatures [94].

High sintering pressure combined with a high heating rate is more effective for improving the microstructure and properties of materials consolidated by SPS. For example, E. Macía et al. [95] prepared a Y–Ti–Zr-containing ODS FeCrAl alloy through MA and SPS at 80 MPa. They investigated the effects of SPS heating rates (100 °C/min, 200 °C/min, 400 °C/min, and 600 °C/min) on the microstructure and mechanical properties. The results showed that as the heating rate increased, the area of ultrafine-grained regions expanded while the grain size within these regions decreased, achieving an optimal balance between room-temperature plasticity (22~26%) and yield stress (800~910 MPa), as illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparison of engineering tensile stress–strain curves for the SPSed ODS steels. SEM micrographs showing the cracks formed during the tensile test of Zr200 ODS steel depending on tensile deformation [95].

The above experimental results demonstrate that the mechanical properties of ODS FeCrAl alloy, particularly its ductility, can be remarkably enhanced by employing higher sintering pressure and faster heating rates at 1100 °C, which effectively inhibits oxide coarsening in the ODS alloy. Mechanical property analysis reveals that the SPS-processed Zr-containing ODS FeCrAl alloy exhibits mechanical properties comparable to those of steels consolidated through conventional methods (HIP or HE).

Table 1 summarizes the correlation between SPS sintering parameters and mechanical properties. The experimental results demonstrate that samples prepared with higher sintering pressures and faster heating rates exhibit improved strength and ductility [94,95]. In contrast, samples sintered at lower pressures and slower heating rates require additional heat treatments (such as densification and/or homogenization) to achieve satisfactory performance [90,91]. These processing methods are equally effective for ODS FeCrAl alloys to achieve an optimal strength–ductility balance [95].

Table 1.

Relationship between SPS sintering parameters and mechanical properties.

3. Stability of Oxides

3.1. High-Temperature Stability of Oxides

The precipitation of nano-oxides endows ODS iron-based alloys [41,96] with enhanced high-temperature stability compared to conventional non-ODS iron-based alloys such as the F82H alloy [97]. Meanwhile, the thermal stability of nano-scale oxides is a key factor in prolonging their service life at high-temperatures.

In Ti-containing ODS Fe–Cr alloys, oxide particles exhibit exceptional long-term stability under reactor operating temperatures (600~800 °C) for durations ranging from 10 to 60,000 h, as demonstrated in alloys such as 12YWT [98], 14YWT [74], ODS Eurofer [99], and NFA MA957 [100]. Additionally, the short-term stability of Y–Ti–O-enriched oxides at ultra-high temperatures (800~1400 °C) in these ODS alloys has attracted significant attention. For instance, studies have shown that nanoclusters exhibit strong resistance to coarsening at temperatures of up to at least 1000 °C [17].

The coarsening resistance of nanostructured oxides is characterized by distinct microstructural features. For example, Hirata et al. [101,102] demonstrated that non-stoichiometric Y–Ti–O nanoclusters (1~2 nm) in 14Cr ferritic ODS steel exhibit complete coherency with the ferritic matrix and possess a NaCl-type crystal structure. Dou et al. [103] employed misfit Moiré fringes to quantify the proportions of coherent, semi-coherent, and incoherent particles in ODS alloys, while also determining the lattice misfit magnitude and misfit strain of the oxides. The coherency between the nano-oxides and matrix significantly influences the thermal stability and mechanical properties of ODS alloys [104,105]. As an essential fundamental issue, understanding the interface structure of the nano-scale oxides is crucial for explaining the nucleation, growth, and coarsening of particles. During the nucleation of the second phase, the oxide–matrix interface can be categorized as coherent, semi-coherent, or incoherent. When lattice parameter differences exist between the precipitate and matrix phases, coherent or semi-coherent interfaces form, generating interfacial misfit strain [106].

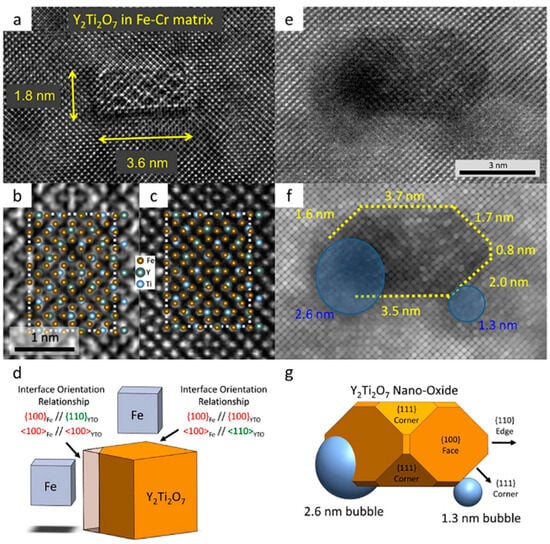

Some studies [106,107] have observed that during annealing at 1573 K, the Y–Ti–O nanoclusters transformed from spherical morphology into perfectly cubic Y2Ti2O7, establishing a cube-on-cube orientation relationship with the matrix, as shown in Figure 8 [107] and Figure 9 [25]. These findings are consistent with the results reported by Yamashita et al. [108], Kishimoto et al. [109], Ohnuma et al. [110], and Klimiankou et al. [111].

Figure 8.

TEM observations of the particle shape evolution: (a) indistinguishable shape (supposed spheroid) before annealing, (b) cube shape after annealing showing the diagonal {110} Y2Ti2O7 plane and proving the cube-on-cube orientation relationship (plus matrix diffraction pattern), (c) Y2Ti2O7 Moiré fringes after annealing creating by the 110 matrix reflection [107].

Figure 9.

(a) Small 1.8 × 3.6 nm Y2Ti2O7 NO showing Moiré fringes from coherency strains; (b) STEM and (c) exit wave focal series images of the central portion of a larger Y2Ti2O7 NO showing the ordered pyrochlore structure that produces a 5 × 7 near coincident site lattice interface with the Fe–Cr matrix; (d) a representation of the Fe and Y2Ti2O7 unit cells along with interfacial orientation relationships; (e) actual and (f) processed HRSTEM images; (g) corresponding 3-Dpolyhedral rendering of a NO with various low index interfaces and the position of two He bubbles that preferentially format the (111) corner facets [25].

In numerous cubic metals, misfit strain-induced elastic stresses control the equilibrium morphology of second-phase particles with cubic crystal structures [112]. As a key experimental parameter, a misfit strain generates elastic strain energy. When present in precipitates, this misfit-induced elastic strain energy significantly influences the morphological stability of the precipitate phase. Moreover, the anisotropy of elastic moduli (the stress-to-strain ratio) can reduce the elastic strain energy of precipitates, leading to a morphological transition from spherical to polyhedral shapes [113]. Through numerical calculations, S. Onaka et al. [114] demonstrated that among polyhedral morphologies, the {111} octahedron and {100} cube correspond to the highest and lowest elastic strain energy per unit of precipitate volume, respectively. These findings align with the experimental observations of the cube-on-cube orientation relationship reported by Ribis et al. [106,107]. Using the supersphere approach, Ribis and colleagues calculated both elastic and interface energies, determining a (100) interface energy value of 260 mJ·m−2 for Y2Ti2O7 particles. The stability and extremely slow thermal evolution of this coherent particle system can be partially attributed to the low interfacial energy resulting from the coherent embedding configuration of these nanoclusters.

This microstructure characteristic significantly affects the mechanical properties of ODS alloys. The origin of creep threshold stresses in dispersion-strengthened alloys is commonly linked to three mechanistic categories: (i) particle shearing [115], (ii) bypass through climb [115,116], and (iii) detachment [117]. Mechanisms (i) and (ii) operate in the presence of coherent [115,116,118] or semi-coherent particles [119], with lattice misfit and misfit strain being key influencing factors [115,116,118,119]. Mechanism (iii) becomes relevant when particles are incoherent [117].

The high-temperature stability of the nano-oxides dispersed within ODS FeCrAl alloys has also attracted widespread attention. Regarding ODS FeCrAl alloys without Zr, Zhang et al. [120] studied the crystal structure of nano-oxides (orthorhombic YAlO3) and the interface between the oxides and matrix in commercial PM2000 by HRTEM. The evolution of the orientation relationship is described as follows: (1) In the as-received alloy, the nano-oxides form a coherent interface with the ferrite matrix, exhibiting a near cube-cube orientation. (2) After annealing at 1200 °C for 1 h, the interface becomes predominantly non-coherent. (3) Annealing at 1300 °C can lead to the coarsening of the nano-oxide particles and the formation of new pseudo-cubic-to-cubic orientation relationships. Kyoto University developed a high-chromium ODS FeCrAl alloy to meet the demands of nuclear applications requiring long-term high-temperature exposure [80,121]. Studies revealed that the coherency of the oxides is size-dependent, with YAH oxides (diameter < 4.5 nm) remaining coherent with the matrix. Due to the exceptional thermal stability of the YAH phase (significantly superior to YAP, YAM, and YAG [122]), alloys with a higher fraction of YAH oxides and greater coherency are expected to exhibit lower metal–oxide interfacial energy and enhanced thermal stability.

A study on the coarsening kinetics of Y–Al–O nanoprecipitates in the second-generation low-Cr ODS FeCrAl alloy developed by Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) [123] revealed that the precipitate size remained stable below 1050 °C, with coarsening activated via Ostwald ripening above this temperature. In addition, phase transition may occur during oxide coarsening. For example, under prolonged high-temperature aging, newly formed YAG-type nanoprecipitates exhibit a tendency to transform into YAP-type structures, which may be attributed to internal oxidation and polymorphic transition reactions [124] during consolidation processes resulting from oxygen’s differential affinity with various solute atoms.

It is noteworthy that Y–Al–O phases detected in ODS FeCrAl alloys fabricated by different research teams exhibit distinct characteristics, with significant variations even observed in commercial alloys such as PM2000 and MA956 across different production batches. This variability may complicate alloy inspection and characterization, while also contributing to unpredictable microstructural evolution and service performance of the alloy under prolonged neutron irradiation.

With the compositional optimization of accident-tolerant ODS FeCrAl alloys, the thermal stability and coherency of Y–Zr–O oxide particles remain extensively studied as critical performance indicators. The coherence between Y–Zr–O phases and the bcc matrix was characterized and analyzed in detail by Dou et al. [125,126,127,128]. Table 2 summarizes the coherency data of Y–Zr–O phases in Zr-containing ODS FeCrAl alloys, including trigonal δ-phase Y4Zr3O12 and cubic Y2Zr2O7 complex oxides. A comparative analysis of the lattice misfit values in Table 2 reveals that the δ-phase Y4Zr3O12 is anisotropic due to asymmetric crystal structure. However, the lattice misfit of Y2Zr2O7 is isotropic due to its highly symmetrical crystal structure. Both oxide phases maintain excellent coherency with the matrix, indicating their low interface energy, high affinity with the matrix, and outstanding thermal stability.

Table 2.

Coherence data of Y–Zr–O phase in ODS FeCrAl alloy containing Zr.

For severe reactor accident, the growth kinetics of different types of oxides at temperatures ranging from 1200 °C to 1350 °C were systematically evaluated and compared by Oono et al. [129]. They concluded that the stability of Y4Zr3O12 is lower than that of YAM, Y2Ti2O7, Y2O3, and YAP. This conclusion is similar to the findings of Sawazaki’ s research [130].

The coarsening and stability of nano-oxides can be explained by the following factors: (1) The inherent Gibbs free energy of oxides at high-temperatures plays a critical role, as different oxides exhibit varying thermodynamic stability [129]. (2) According to the ZrO2-Y2O3 phase diagram, Y4Zr3O12 undergoes decomposition above 1660 K (1387 °C) [131], whereas other oxides (e.g., YAM, Y2Ti2O7, Y2O3, and YAP) remain stable at significantly higher temperatures [132,133,134]. (3) The growth of oxides in alloys is controlled by solute diffusion, which is called Ostwald ripening [135]. In this process, smaller oxide particles dissolve, and the released solute atoms diffuse to larger particles, leading to the growth of larger oxides at the expense of smaller ones. This phenomenon is most commonly analyzed using the Lifshitz–Slyozov–Wagner (LSW) theory of coarsening [136].

As previously mentioned, the coarsening rate of particles in a supersaturated matrix is controlled by the bulk diffusion of solute atoms through the matrix, as illustrated in Figure 10a,b. Given the extremely low solubility of O and Y in bcc-Fe [101] and the fact that Y exhibits the slowest diffusion rate in defect-free bcc-Fe [137,138,139,140,141], Y primarily governs the coarsening kinetics of nanoparticles. This characteristic effectively suppresses oxide coarsening [142]. Moreover, coherent oxide interfaces can reduce the Gibbs–Thomson effect at the interface [125]. Therefore, if solute atoms (such as Y or Zr) have difficulty attaching to coherent interfaces, it follows that for particles with complex lattice structures composed of two or three different elements, this process becomes even more challenging [106].

However, ODS alloys contain a high density of crystalline defects, including dislocations and grain boundaries, resulting from mechanical alloying (MA) and thermal solidification processes. These structural defects significantly complicate the oxide coarsening mechanisms. Through a comprehensive review of the existing literature on the Lifshitz–Slyozov–Wagner (LSW) coarsening theory, we propose that the following factors may critically influence the coarsening behavior:

(a) The matrix structure of alloys varies significantly with their chemical composition. In ODS Fe–Cr alloys, for instance, the Cr content determines the matrix phase: alloys containing less than 12 wt% Cr develop a martensitic structure, while those with ≥12 wt% Cr exhibit a ferritic structure. Specifically, the 9Cr-0.13C-2W-0.2Ti-0.35Y2O3 alloy at room temperature features a martensite lath structure with low-carbon [22,143], characterized by a substructure predominantly consisting of high-density dislocations, as illustrated in Figure 10a. When subjected to elevated-temperature annealing above 1200 °C, the matrix undergoes structural transformation due to the bcc-α to fcc-γ phase transition. Within this temperature range, both phases coexist in the system. This phase transformation leads to the formation of phase boundaries, which may initiate oxide coarsening. Concurrently, the dislocation density decreases through glide and climb mechanisms, enhancing the pipe diffusion of oxide-forming elements along dislocations and consequently accelerating oxide particle coarsening (see Figure 10b). As shown in Figure 10c, cooling back to room temperature results in a microstructure characterized by coarsened oxides and reduced dislocation density.

(b) The preparation methods can significantly alter the coarsening mechanisms of oxide particles. As demonstrated in reference [129], the hot extrusion process for 15Cr ODS FeCrAl alloy combines solidification and hot-working into a single integrated step, resulting in an as-extruded microstructure characterized by refined grains and a high density of dislocations (see Figure 10d). These microstructural features facilitate the diffusion of oxide-forming elements through dual pathways: along grain boundaries and through dislocation pipes, as shown in Figure 10e,f.

(c) The preparation route of alloys plays a crucial role in determining the coarsening behavior of oxide particles. Taking the Fe-12Cr-2W-0.3Ti-0.25Y2O3 alloy as an example, this material was subjected to an elaborate thermomechanical processing sequence comprising hot extrusion, hot forging, intermediate annealing, cold rolling, and final high-temperature annealing [144,145,146]. While during cold rolling, significant dislocation density and stored energy are accumulated; however, final heat treatment drives dislocation recovery, resulting in distinct and coarsened grains largely free of dislocations. These samples thus serve as an ideal platform for probing lattice diffusion processes (see Figure 10g,h).

(d) Further evidence of dislocation-mediated coarsening is presented in reference [147]: oxide particles located on dislocation lines exhibited morphological changes after interacting with dislocations. Notably, coarsened oxide particles were observed to align in rows parallel to adjacent dislocations, strongly suggesting their formation through dislocation migration mechanisms. Moreover, the study revealed the formation of dislocation networks with fine oxide particles serving as nodal points, creating favorable conditions for particle coalescence and growth, as illustrated in Figure 10i–k. In reference [147], the samples prepared by mechanical alloying (MA) and spark plasma sintering (SPS) within a short duration of 5 min contained abundant defects such as vacancies and dislocations. During annealing, these defects became activated and tended to migrate and accumulate. When encountering oxides at elevated temperatures up to 1200 °C, the stress or strain induced by dislocations may disrupt the bonding of oxide-forming elements, promoting their dissolution and subsequent diffusion along dislocation lines. This defect-assisted process ultimately led to the reprecipitation of larger oxide particles.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagrams of coarsening mechanisms of oxides [147].

The distinct diffusion mechanisms reported in previous studies are systematically summarized in Table 3. The grain boundary diffusion-dominated coarsening mechanism, as theoretically predicted in references [129,143], has been conclusively validated through experimental observations [148]. For instance, precipitate dissolution and coarsening occurred as a consequence of grain boundary migration, accompanied by the appearance of Precipitate-Free Zones (PFZs) [148]. Therefore, when extending theoretical models, it is essential to validate them with corresponding experimental datasets. This approach is critical for gaining insights into the microstructural evolution of ODS FeCrAl alloys under specific conditions, such as high-temperature thermomechanical processing or accident scenarios prior to material failure.

Table 3.

Differences in diffusion mechanisms of previous studies.

3.2. Irradiation Stability of Oxides

The development of advanced fission and fusion reactor technologies demands the creation of specialized materials capable of withstanding extreme operating conditions, including high temperatures (300~1000 °C) and intense radiation environments (>50 displacements per atom, DPA) [149,150]. In this context, oxide dispersion-strengthened (ODS) FeCrAl alloys have emerged as promising accident-tolerant materials, combining the exceptional high-temperature oxidation resistance inherent to FeCrAl alloys [151,152] with the superior mechanical strength and radiation tolerance characteristic of traditional ODS Fe–Cr alloys [24]. Over recent years, extensive research efforts have been devoted to investigating the microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of ODS FeCrAl alloys under irradiation conditions, yielding encouraging results that demonstrate their potential for nuclear applications.

Due to the high sink strength of oxides in ODS FeCrAl, α′-phase from the matrix is suppressed compared with forged FeCrAl alloy [153]. Regarding the radiation resistance of oxide particles in ODS FeCrAl alloys [154], several crystalline phases demonstrate exceptional performance owing to their unique structural characteristics. These include the triangle δ-phase Y4Zr3O12, cubic Y2Zr2O7, orthogonal Y2TiO5, cubic Y2Ti2O7, and orthogonal YAP. Among these, the trigonal δ-phase Y4Zr3O12 stands out as one of the most radiation-resistant fluorite-derivative structures [155]. This particular phase features a rhombohedral crystal symmetry that is structurally analogous to, yet distinct from, the cubic fluorite (CaF2) configuration. The cubic Y2Zr2O7 adopts an anion-deficient fluorite structure, which can be attributed to its favorable ionic radius ratio (rY3+/rZr4+ = 1.019 Å/0.72 Å ≈ 1.42) [134,156]. This specific structural characteristic endows the material with remarkable irradiation stability, as demonstrated in previous studies [157,158]. Among orthorhombic rare earth titanates, Y2TiO5 exhibits superior radiation resistance, undergoing a phase transformation to a disordered fluorite structure under irradiation while maintaining structural integrity [159]. And the irradiation stability of Y2TiO5 oxide particles in Fe-16Cr-0.1Ti ODS steel has been experimentally verified after 60 dpa ion irradiation at 650 °C [109]. Experimental studies have demonstrated that orthorhombic YAP (YAlO3) exhibits excellent irradiation stability under high-temperature and high-dose conditions. For instance, after ion irradiation at 670 °C up to 150 dpa, the orthorhombic YAP phase in K4 remained structurally stable, as confirmed in previous studies [160,161]. However, amorphization happened to the Y–Al–O in ODS Fe–Cr alloy containing Al (without Zr) after irradiation in later research. For example, when PM2000 [162] was irradiated by neutrons up to 20 dpa at 500 °C, the size, number density, and Y–Al ratio of YAlO3 precipitates (about 25 nm in diameter) did not change substantially, while YAlO3 precipitates are completely amorphous after irradiation.

Compared to neutron irradiation, heavy ion irradiation can induce a higher displacement damage rate, significantly influencing the evolution of oxide particles. For instance, when MA956 [163] was irradiated with 5 MeV Fe ions at 450 °C to a dose of 25 dpa, the Y–Al–O particles in the alloy exhibited an increase in diameter alongside a reduction in number density. Furthermore, under 700 MeV Bi ion irradiation at 300 K up to a fluence of 1.5 × 1013 cm−2, Y4Al2O9 (YAM) particles in ODS ferritic steel demonstrated size-dependent anti-amorphization behavior. Specifically, smaller YAM particles (~5 nm) retained their crystalline structure, whereas larger ones (~20 nm) underwent amorphization [164].

To systematically evaluate the irradiation resistance of alloys before service, researchers have investigated the evolution of microstructure and mechanical properties of ODS FeCrAl alloys under various simulated service conditions using different irradiation parameters. Representative cases are as follows:

(1) Massey et al. [153] studied the stability of Y–Al–O nano-oxides in ODS FeCrAl alloy (Fe-12Cr-5Al wt%) at different irradiation temperatures of 215, 357, and 557 °C using atomic probe tomography. The study demonstrated that while the oxide nanoparticle size remained stable post-irradiation, the Y–Al ratio exhibited temperature-dependent variations. This behavior stems from the competition between ballistic dissolution and precipitation recombination. At lower irradiation temperatures, where ballistic dissolution dominates, the composition of precipitates undergoes significant alteration. Conversely, at higher temperatures, enhanced atomic reverse diffusion facilitates the return of solute atoms to precipitates, causing the Y–Al ratio to gradually recover toward its pre-irradiation state. These findings suggest that irradiation temperature can significantly influence the structural evolution of (Y–Al–O) nano-oxide crystalline phases.

(2) Kondoa et al. [165] studied the correspondence between the microstructure and mechanical properties of 12Cr-6Al ODS ferritic steel (Fe-12Cr-6Al-0.4Zr-0.5Ti-0.5Y2O3-0.24 Ex.O) with different ion irradiation displacement damage (0.5, 5 and 20 dpa) at 300 °C. The study confirmed that oxide nanoparticles maintained stable size distribution and average size under ion irradiation up to 20 dpa. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observations indicated that irradiation-induced defect clusters grew in both size and number density with increasing displacement damage.

By calculating the correlation between irradiated microstructure and irradiated hardening theoretically, the theoretical hardness value is in good agreement with the experimental hardness value under 5 dpa irradiation, while under 20 dpa irradiation, the theoretical hardness value is slightly different from the experimental hardness value. The radiation hardening of 12Cr-6Al ODS ferritic steel is mainly caused by irradiation-induced defect clusters below 5 dpa. When the irradiation dose is increased to 20 dpa, the radiation will have additional effects, which is considered to be caused by α′-phase transition, indicating that a larger irradiation dose would lead to multiple defects in the material, resulting in deviation between actual performance and theoretical prediction [165].

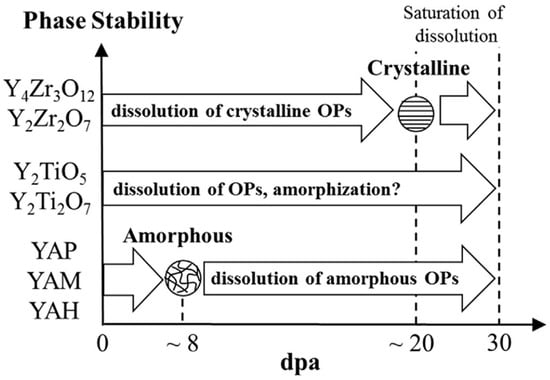

Song et al. [166] conducted a systematic investigation into the phase stability of various oxide nanoparticles (Y–Ti–O, Y–Al–O, and Y–Zr–O) in 15Cr ODS ferritic steel under 6.4 MeV Fe3+ ion irradiation at 200 °C up to 10 dpa. The research indicates that the phase stability of oxide particles, as evidenced by changes in volume fraction and amorphization resistance, follows the order: Y–Zr–O > Y–Ti–O > Y–Al–O. As illustrated in Figure 11, the dose-dependent amorphization behavior of these oxide phases exhibits distinct variations under increasing irradiation doses.

Figure 11.

Modeling ion irradiation effects on oxide particles (OPs) in three types of ODS ferritic steels at 200 °C up to 30 dpa [166].

It is noteworthy that under non-irradiated conditions, although Y–Zr–O oxides exhibit inferior high-temperature stability compared to Y–Ti–O and Y–Al–O at temperatures above 1200 °C [129], it can be anticipated that under reactor operating conditions, when these oxides coexist in ODS FeCrAl alloys, the Y–Zr–O phase will exhibit even more superior irradiation resistance, serving as the primary contributor to the alloy’s excellent irradiation performance. [127]. According to a relevant review [41], the long-term performance of the alloy is primarily governed by two key factors: (1) the thermal and irradiation stability of both the matrix [167] and oxide phases under coupled extreme conditions and (2) the corrosion resistance of the matrix in high-temperature, irradiated environments [168]. These factors collectively determine the alloy’s service lifetime.

In a recent study, Dou et al. [169] conducted a detailed characterization of the nano-oxides in a newly developed Ce-containing ODS FeCrAl alloy. Their findings confirmed that the addition of Ce has a dual effect of refining both the grains and the nanoparticles. The study also revealed the mechanisms of Ce-induced oxide formation and polymorphic transformation, as well as the evolution behavior of the microstructure, providing a crucial theoretical foundation for the compositional optimization and innovative design of ODS steels. However, further research is still needed to investigate high and low-temperature stability, irradiation resistance, and systematic comparison with other oxides in this novel alloy.

4. Microstructural Deformation

4.1. Deformation of the Matrix

Through progressive refinement of tubular manufacturing processes, Japanese researchers have successfully fabricated FeCrAlZr oxide dispersion-strengthened (ODS) alloy cladding tubes with precise wall thicknesses of either 0.3 mm or 0.4 mm, while maintaining tube lengths over 4 m [170]. During ODS cladding tube processing, recrystallization in the final heat treatment is critical for tailoring microstructure, texture, and mechanical properties. The oxide phases within these alloys significantly dictate their recrystallization kinetics and grain structure evolution [171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179].

The texture evolution of ferritic ODS steel under hot rolling, cold rolling, and recrystallization conditions was systematically investigated by Raabe et al. in 1993 [171]. Their study demonstrated that cold rolling induces a pronounced α-fiber texture with <110>‖RD, comprising {001} <110>, {112} <110>, and {111} <110>. Notably, the recrystallization of cold-rolled samples without stable oxides led to preferential grain growth selection along the {111} <112> orientation. Through electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) analysis, Leng et al. [172] studied the recrystallization behavior of cold-rolled ferritic ODS steel at low- and high-temperatures. The results indicated that the as-cold-rolled texture contains both α-fiber, such as {001} <110>, {112} <110>, and γ-fiber, such as {111} <110> and {111} <112>, which evolved into a unique {011} <211> oriented coarse grain at a lower annealing temperature of 1000 °C, and a typical {111} <211> oriented fine grain recrystallization texture at a higher annealing temperature. The different recrystallization behavior is attributed to the higher boundary mobility between {011} <211> and {001} <110> deformed matrices.

In addition to the final heat treatment, previous studies have also pointed out the influence of the rolling path and pre-annealing conditions of ODS steel on the final recrystallization structure [173]. The results showed that {111} <211> texture is produced in the first cold rolling, but a different {011} <211> texture is produced in the second cold-rolling annealing using higher recrystallization temperature. These variations are attributed to divergent crystal rotation pathways during the primary and secondary cold-rolling stages, which generate distinct cold-rolled textures. Moreover, the implementation of a 900 °C recovery annealing step prior to recrystallization suppressed recrystallization rates and resulted in coarse {011} <211> grains, regardless of higher subsequent annealing temperatures. Recently, the texture and microstructure of both the plate and tube of 14YWT nanostructured ferritic alloy produced by two different processing methods of spray forming followed by hydrostatic extrusion and also the hot extrusion and cross-rolling of the plate followed by hydrostatic tube extrusion were also studied [180]. The results showed that hydrostatic extrusion induced a mixed deformation mode of plane strain and shear, producing weak α and γ-fiber components of {001} <110> and {111} < 110> together with a weak ζ-fiber component of {011} <211> and {011} <011>. By contrast, multi-step plane strain deformation by hot extrusion and cross-rolling of the plate led to a strong texture component of {001} <110> together with a weaker {111} <112> component. These results above [180] confirm that texture evolution is highly sensitive to the specific processing conditions employed.

Taking the newly developed Fe-12Cr-6Al-0.5Ti-0.4Zr-0.5Y2O3-0.24 Ex.O (wt.%) as a research object, Aghamiri et al. [181] conducted a comprehensive investigation on the newly developed Fe-12Cr-6Al-0.5Ti-0.4Zr-0.5Y2O3-0.24 Ex.O (wt.%) alloy, systematically evaluating the microstructure and tensile properties of ODS FeCrAl cladding tubes under various processing conditions. Their work elucidated the evolution of microstructure and texture under different final processing stages, including extrusion, rolling, and recrystallization, yielding more comprehensive and practically relevant research conclusions: (1) the hot extruded microstructure with a strong α-fiber oriented in the <110> direction shrink to orientations between {110} <110> and {111} <110>, and a new γ-fiber forms in the {111} texture during cold pilger rolling. (2) The final annealing (810~850 °C) results demonstrate that highly deformed micron/submicron-sized grains in FeCrAl cladding tubes after cold pilger rolling grow into millimeter-sized recrystallized grains against the pinning force of nanometer-sized oxide particles, driven by the high stored energy within the material. (3) Different extrusion temperatures (1100 °C or 1150 °C) lead to distinct distributions of oxide particles, thereby forming varied final recrystallization textures. (4) The tensile properties of FeCrAl ODS cladding tubes are primarily controlled by the final microstructure and its processing history.

Table 4 summarizes the results of recrystallization-textured ODS steels from the above studies. From Table 4, it can be observed that although there are differences in the sample preparation processes, the cold-rolled and recrystallization textures exhibit certain similarities, primarily consisting of α and γ types. This suggests that these two types of textures remain stable in ODS steels. Leng et al. [172] proposed that the formation mechanism of recrystallization textures in ODS steels involves the growth of nuclei within the deformed matrix during the recrystallization process, thereby releasing the stored energy in the deformed microstructure. In the study by Aghamiri et al. [181], it was experimentally detected that there were weak texture components in the deformed matrix, such as {111} <112> and {110} <112> orientations, which are regarded as the main recrystallization nuclei existing in the deformed structure. The {111} <112> and {110} <112> orientations, based on the grain orientation results in the recrystallized structure align with those of the large recrystallized grains.

Several internal factors affect the formation of recrystallization texture:

(1) For the common {111} <112> orientation, the growth rate of recrystallized grains is evaluated according to the following equation: V = M × F, where M is the boundary mobility between the nucleus and the surrounding deformed matrix, and F is the total driving force of recrystallization. For F = E-P, E is the equivalent to the stored energy (E) of the deformed matrix, and P is the pinning force of the dispersed oxide particles. The stored energy of the deformed matrix depends on the orientation of deformed grains and the order from high to low, which is E {111} > E {112} > E {001} [173]. Thus, the driving force F {111} is highest when a nucleus tries to grow into the {111} <112> deformed matrix.

(2) Oriented growth theory [182] can be used to explain the unique {110} <112> orientation in ODS alloys [172,173,181]. According to M = M0 exp (–Q/RT), both temperature and boundary characteristics play key roles in determining boundary mobility. As seen in reference [178]: M0 is the initial value, Q is the activation energy for transfer of atoms across the boundary, R is the universal gas constant, and T is the temperature. For grain boundaries with a misorientation angle of 20~45° between deformed grains and nuclei of recrystallization, the nuclei has higher energy and higher mobility than lower energy boundaries [179]. From this calculation result, {110} <112> nuclei should have a higher mobility than {110} <112> nuclei, which is consistent with the experimental observation. Similarly, in the experimental study by Shen et al. [183], the authors also used the order of stored energy along the α- and γ- fibers; i.e., E {001} <110> < E {112} <110> < E {111} <112> < E {111} <110>. The authors of reference [184], to explain the formation mechanism of the recrystallization texture of the {111} <110> and {111} <112> components, explained the formation reason of the {110} <001> texture through the oriented growth theory [182].

(3) In ODS steels, the pinning effect of dispersed oxide particles is considered one of the factors that affect the selective growth of grain orientation. In deformed grains, grain orientations with lower stored energy may be unable to overcome the pinning effect of oxide particles, thereby leading to the suppression of their growth. However, the grain orientation with higher storage energy can break through the pinning effect of oxides and grow preferentially. To evaluate the effect of oxide dispersion, Qin et al. [185] compared the microstructure and recrystallization of wrought FeCrAl alloy and ODS–NFA in industrial pilgered tubes. The microstructure and recrystallization behavior are strongly influenced by second-phase particles. In the FeCrAl alloy, complete recrystallization occurs at 800 °C due to micron-sized Laves precipitates. By contrast, the presence of nano-oxide particles in the ODS–NFA tube stabilizes ultrafine fibrous grains, thereby postponing recrystallization to 1200 °C. Nano-oxides led to a significant reduction in the size of recrystallized grains. In FeCrAl alloys, the recrystallization mechanism primarily involves grain boundary migration and Laves precipitate-stimulated nucleation processes. Conversely, ODS–NFAs exhibit recrystallization behavior governed by the dissolution and reprecipitation dynamics of nanoscale particles. These findings not only enhance the fundamental understanding of microstructural evolution mechanisms but also provide actionable insights for designing and optimizing high-performance alloy tubes in extreme service environments through microstructure engineering.

Table 4.

Main types of textures in previous studies.

Table 4.

Main types of textures in previous studies.

| C | HC | AT | CT | HT (°C) | RT | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HE + F | α<110>//RD | α {100} <110> + γ {111} <110>, {111} <112> | 1000 | {011} <211>, {110} <112> | [172] |

| 1150, 1300 | {111} <211> | |||||

| 2 | HE + F | α<110>//RD | 1st: α {100} <110> + γ {111} <110> | 950 | {111} <211> | [173] |

| 2nd: α {100} <110> + γ {111} <112> | 1100 | {111} <110> | ||||

| 3 | HE | α<110>//RD | α {001} <110> + γ {111} < 110> | {001} <110> + {111} <112> | [180] | |

| 4 | HE1100 | α<110>//RD | α {110} <110> + γ {111} <110> | 1150–1200 | (110) <211> | [181] |

| HE1150 | (110) <211> + {111} <112> | |||||

| 5 | HE + F | α<110>//RD | γ {111} <110>, {111} <112> | 1000, | {111} <110>+ {111} <112> | [183] |

| 1100, | {111} <110> + {111} <112> | |||||

| 1200 | {111} <110> + {111} <112> {110} <001> |

C—Composition, HC—Hot consolidation, AT—Texture of as-prepared, CT—Cold-rolling texture, HT—Heat treatment, RT—Recrystallization texture, HE—Hot extrusion, F—forging. 1: Fe-15Cr-0.03C-2W-0.3Y2O3, 2: Fe-15Cr-0.03C-2W-0.3Y2O3, 3: Fe-12Cr-2W-0.3Ti-0.25Y2O3, 4: Fe-14Cr-3W-0.35Ti-0.25Y, 5: Fe-12Cr-6Al-0.5Ti-0.4Zr-0.5Y2O3.

Among previous studies reviewed, some scientists use more basic methods, i.e., dynamic plastic deformation (DPD) compression, to simulate the microstructure evolution of the rolling process of ODS alloys. For example, Zhang et al. investigated the effect of dynamic plastic deformation (DPD) compression on the microstructure of PM2000 and the annealing behavior of DPD-treated PM2000 [186]. The study revealed that DPD-induced refined nano-lamellae with a dual <111> + <100> fiber texture significantly enhanced material strength but compromised thermal stability. As shown by the hardness curves in Figure 12 [186], the nanostructure formed in PM 2000 after DPD compression exhibits remarkable stability even after annealing at temperatures up to 500 °C for 1 h. Meanwhile, annealing at a temperature higher than 500 °C makes the nanostructure unstable, which shows the significant softening. And obvious recrystallization occurs when the temperature is higher than 700 °C (see Figure 13). Compared to the as-prepared state, no signs of recrystallization were observed even after annealing at 1100 °C for 1 h [187], indicating a significant reduction in the thermal stability of the nanostructured state following DPD. Additionally, due to variations in stored energy density across different orientations, the microstructure undergoes orientation-dependent recrystallization, resulting in a strong fiber texture observed at near-complete recrystallization stages, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Vickers hardness of PM2000 compressed by DPD to a strain of 2.1 and annealed at different temperatures for 1 h [186].

Figure 13.

Orientation maps for PM2000 after compression by DPD and subsequent annealing at 715 °C for (a) 10 min, (b) 20 min, and (c) 80 min [186].

4.2. Deformation of the Oxides

Given the critical role of nano-oxides in ODS alloys, comprehensive studies have been conducted to characterize their chemical composition, crystal structure, and oxide-matrix interfaces in as-processed materials [41]. In actual manufacturing processes, however, nuclear fuel cladding tubes are typically subjected to around three to four passes of cold rolling with subsequent low-temperature annealing treatments, resulting in a total thickness reduction of 70~80% [170,181]. When subjected to such severe plastic deformation and mechanical stresses, complex interactions between the matrix and oxide particles inevitably occur, leading to substantial microstructural modifications.

Regarding the interaction between oxides and the matrix during plastic deformation, particular emphasis should be placed on the fact that any alterations in nano-oxide structure and morphology induced by plastic deformation may significantly modify their mechanical properties and radiation resistance [188].

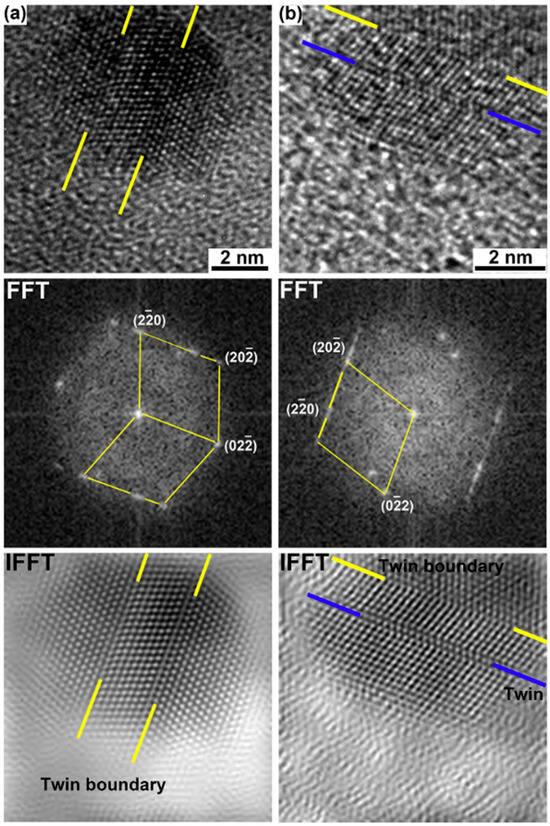

Zhang et al. [189] studied the response of nanoparticles in PM2000 to dynamic plastic deformation (DPD) and found that the main mechanism of plastic deformation of Y–Al–O oxides was deformation twins, as shown in Figure 14. It was concluded that the plastic deformation of oxides increases with the increase of strain applied and did not depend on the interfacial coherence between the oxides and the ferrite matrix. Wang et al. [188] observed the deformation behavior of 5 nm-sized Y–Zr–O nano-oxides in Zr-containing ODS FeCrAl alloys, revealing distinct evolutionary patterns of oxides with different dimensions during deformation. They proposed a deformation-induced microstructural evolution mechanism governed by the synergistic effects of oxide size dependency and heterogeneous interfacial structural correlation. A recent study [190] revealed that nanostructured ferritic alloys (Fe-12Cr-1Mo-0.3Ti-0.3Nb-0.3Y2O3, wt%) undergo a distinct morphological evolution of their nano-oxide precipitates under extreme thermomechanical processing during thin-walled tube fabrication. Remarkably, while the spherical precipitates transformed into elongated rod-like configurations, both their volume fraction (0.3%) and number density (>1023 m−3) remained unchanged. Throughout this morphological transition, the precipitates maintained their coherency with the Fe matrix without any detectable compositional variation. The researchers attributed this shape transformation to the unique shearable characteristics of the (Y, Ti, O)-enriched precipitates, suggesting they act as “soft” obstacles that can be readily deformed during dislocation interactions. Similar phenomena can also be observed in OFRAC, CrAZY, or 14YWT alloys [191]. These findings provide new insights into the deformation mechanisms of oxide nanoparticles under severe plastic deformation conditions.

Figure 14.

HRTEM images of two oxide nanoparticles in the longitudinal section of PM2000 after compression by DPD to a strain of 0.6 (a,b) and their corresponding FFTs and IFFT images [189].

The aforementioned studies demonstrate that different types of nano-oxides in ODS alloys can undergo “coordinated deformation” with the matrix during macroscopic deformation while maintaining a coherent interfacial relationship. This provides a crucial experimental foundation for the research on fabricating ODS FeCrAl alloy tubes.

Recent studies [188,191] have revealed that smaller nano-oxides are capable of deforming, and their surrounding interfaces maintain good continuity during deformation. The authors of this paper have identified two key issues:

(1) What is the underlying mechanism of the “coordinated deformation” between smaller nano-oxides and the matrix?

While researchers have proposed qualitative hypotheses based on experimental observations [188,189,190,191], systematic characterization and analysis of the interaction between oxides and dislocations in ODS alloy systems remain lacking. Tang et al. [192] employed atomic-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), image simulations, and first-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations to elucidate the slip systems of Ω′ precipitates in Al–Cu–Mg–Ag alloys. This work provides valuable insights and inspiration for understanding the interaction mechanisms between nano-oxides and mobile dislocations in ODS alloys.

(2) What is the damage behavior mechanism of ODS alloys under plastic deformation—specifically, what governs the void formation at interfaces between larger nano-oxides and the matrix?

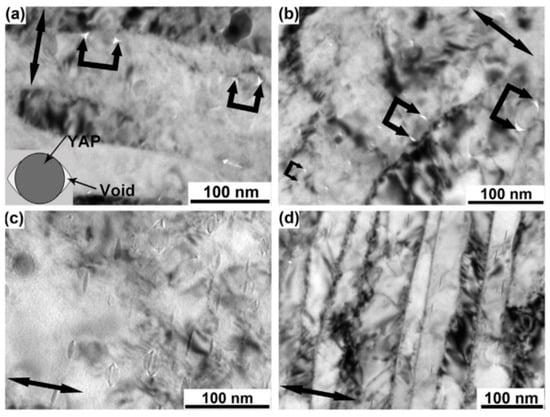

During the process of deformation for steels containing the second phase strengthening phase, the formation of voids is one of the defects that cannot be ignored in the workpiece. After the low and high-temperature rolling of steel, voids can form near the non-metallic particles [193,194,195,196]. Charles et al. [193,194] systematically investigated the deformation behavior of micrometer-sized MnS particles in steel and proposed that the void formation around the particle–matrix interface is attributed to the incapability of the steel matrix to flow around particles while sustaining contact. If the strength of the interface is not enough to bear the tensile stress caused by the deformation of matrix, the particles will decohesion with the matrix, thus forming an annular cavity at the interface. Zhang et al. [189] took PM2000 as the research object and found that after DPD compression, due to the incompatible deformation between the nanoparticles (YAP) and the matrix, nano-voids were formed at the interface during low strain deformation, and they evolved around the larger and smaller particles in different ways with the increase of deformation, resulting in such images as shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

TEM images showing the morphology of oxide nanoparticles from a longitudinal section: (a,b) PM2000 in the as-received condition after compression by DPD to a macroscopic strain of 1.0 and 2.1, respectively. (c,d) PM2000 after annealing at 1200 °C for 1 h followed by subsequent compression by DPD to a macroscopic strain of 2.1 [189].

Although different researchers have proposed varying mechanisms for void formation around non-metallic particles, it is generally agreed that localized heterogeneous flow—caused by interfacial discontinuity between particles and the matrix—is responsible for void nucleation. Consequently, the mismatch in yield stress between particles and the matrix is recognized as a primary driver of interfacial void formation.

In ODS FeCrAl alloys, Wang et al. [188] observed that atomic misalignment within dislocation pile-up zones at larger oxide–matrix interfaces directly contributes to void initiation. These findings suggest that a quantitative analysis of the damage behavior in ODS alloy systems—integrating the aforementioned research methodologies—is both feasible and imperative.

The presence of these nano-pores can significantly deteriorate the creep rate of ODS steels [197] and may markedly reduce their ultimate ductility and irradiation resistance. These findings not only hold important value for understanding the behavior of nanoparticles during the plastic processing of ODS steels but also contribute to elucidating the strengthening mechanisms of nanoparticles in such materials. It is therefore recommended to implement post-processing thermo–mechanical treatments on ODS steels after any plastic deformation-involved fabrication to eliminate voids to the greatest extent possible. Accordingly, Figure 16 schematically summarizes the factors (including but not limited to) influencing the final performance of nuclear reactor fuel cladding based on fabrication routes, highlighting the necessity for meticulous control over all processing details to ensure defect-free preparation of ODS FeCrAl cladding components.

Figure 16.

Factors affecting final properties of fuel cladding.

5. High Temperature Mechanical Properties

The ODS FeCrAl alloy is one of the most important candidate materials for accident tolerance, and its mechanical properties at high temperatures beyond stable operating conditions and within the accident temperature range (900~1400 °C) are critical for the safe operation of nuclear reactors [198]. The deformation and failure mechanisms of materials at such high temperatures are also the research focus for scientists.

Kamikawa et al. [199] investigated the high-temperature (1000 °C) deformation process of a recrystallized ODS FeCrAl ferritic steel with the chemical composition Fe-16.73Cr-6.28Al-0.49Ti-0.033C-0.47Y2O3-0.12Ex. The strain rates ranged from 1.0 × 10−2 to 1.0 × 10−5 s−1. It was found that when the strain rate changed from 1.0 × 10−2 down to 1.0 × 10−4 s−1, then down to 1.0 × 10−5 s−1, the deformation mechanism changed from displacement creep to grain boundary slicing, and then to differential creep. Ultra-high temperature ring tensile tests were performed by Yano et al. [200] to investigate the tensile behavior of oxide dispersion-strengthened (ODS) steel cladding materials with different compositions. The analysis focused on the mechanical properties at 900~1400 °C to investigate their evolution under these conditions. The experimental results (Figure 17) demonstrate that the tensile strength of the 9Cr-ODS steel cladding peaks among core materials at ultra-high temperatures of 900~1200 °C. However, above 1200 °C, the tensile strength decreases significantly due to grain boundary sliding deformation and the γ–δ phase transformation.

Figure 17.

Temperature dependence of tensile properties of FeCrAl-ODS claddings: (a) YS, (b) UTS, (c) UE, and (d) TE. Expanded scale views of the respective left side figures for high and ultra-high temperature ranges are given in the right-side column [200].

By contrast, the tensile strength of recrystallized 12Cr-ODS and FeCrAl-ODS steel claddings with Zr addition retained a high value above 1200 °C. Figure 17 shows that the strength of Zr-added ODS FeCrAl is significantly higher than that of Zr alloys, which is attributed to the pinning effect of Y–Zr–O fine oxide particles (formed at high temperatures) on dislocation motion. A temperature of 1000 °C was judged to be the critical temperature for the change of deformation mechanism. The SEM fractography analysis results of FeCrAl–ODS steel above 1000 °C are similar to those of 12Cr–ODS steel. The shift in deformation mechanisms from grain sliding to grain boundary sliding is attributed to the presence of stable oxide particles in the recrystallized ODS steel.

Regarding the high-temperature creep of the ODS FeCrAl alloy, Kamikawa et al. [201] investigated the elevated-temperature deformation mechanism of the FeCrAl-ODS ferritic alloy at 1000 °C with a strain rate ranging from 10−2 to 10−7 s−1. It was found that with a decreasing strain rate from 10−2 s−1 to 10−5 s−1, the creep mechanism transitions from the conventional oxide particle-pinned dislocation creep to grain boundary sliding (GBS) accompanied by diffusion creep. A new concept of “cooperative” GBS (CGBS) was originally defined and the threshold stress for the onset of CGBS was designated as (CGBS), corresponding to one-third of the conventional threshold stress for dislocation creep.