Simple Summary

Racial and ethnic minority patients are underrepresented in cancer clinical trials (CCTs) due to barriers at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, and community levels. While previous studies aimed to increase minority CCT participation, none have addressed multiple barriers at once. Additionally, formative research is used to inform multilevel interventions (MLIs) aimed at reducing health disparities and is an important step to deploy interventions in real world settings. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to provide an overview of a formative research process to identify (1) barriers and facilitators to minority CCT participation and (2) perspectives on digital and community outreach interventions among community and cancer center end-user groups. This process is particularly important for future research seeking to engage end users in the design and development of targeted MLIs to reduce barriers to CCT participation and health disparities more broadly.

Abstract

Background/objectives: Racial and ethnic minority patients are underrepresented in cancer clinical trials (CCTs) and multilevel strategies are required to increase participation. This study describes barriers and facilitators to minority CCT participation alongside feedback on a multilevel intervention (MLI) designed to reduce participation barriers, as posited by the socioecological model (SEM). Methods: Interviews with Moffitt Cancer Center (MCC) physicians, community physicians, patients with cancer, community residents, and clinical research coordinators (CRCs) were conducted from June 2023–February 2024. Verbal responses were analyzed using thematic analysis and categorized into SEM levels. Mean helpfulness scores rating interventions (from 1 (not helpful) to 5 (very helpful)) were summarized. Results: Approximately 50 interviews were completed. Thematic findings confirmed CCT referral and enrollment barriers across all SEM levels. At the community level, MCC patients and community residents felt that community health educators can improve patient experiences and suggested they connect patients to social/financial resources, assist with patient registration, and provide CCT education. While physicians and CRCs reacted positively to all institutional-level tools, the highest scored tool simultaneously addressed CCT referral and enrollment at the institution (e.g., trial identification/referrals) and interpersonal level (communication platform for community and MCC physicians) (mean = 4.27). At the intrapersonal level, patients were enthusiastic about a digital CCT decision aid (mean = 4.53) and suggested its integration into MCC’s patient portal. Conclusions: Results underscore the value of conducting formative research to tailor interventions to target population needs. Our approach can be leveraged by future researchers seeking to evaluate MLIs addressing additional CCT challenges or broader health topics.

1. Introduction

Non-Hispanic (NH) Black/African American (AA) and Hispanic populations are underrepresented in cancer clinical trials (CCTs) and experience barriers to CCT referral and enrollment across multiple levels [1]. These include barriers posited within the socioecological model (SEM) [2] at the intrapersonal (e.g., patient and physician knowledge, awareness, attitudes, financial barriers) [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15], interpersonal (e.g., relationships between patients and physicians) [6,8,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18], institutional (e.g., trial availability, restrictive eligibility criteria, complex referral processes, logistical challenges) [1,8,14,15,16,17,19,20], and community levels (e.g., lack of community engagement and appropriate trials in community settings) [1,21].

Previous interventions have strived to increase minority CCT participation at the patient- and physician-level, including in a single-session educational program [22] with digital tools aimed at enhancing research literacy and CCT decision-making for minority patients [23,24,25], implicit bias training for physicians [26], and a clinical trial site self-assessment tool designed to review data on clinical trial site screening and enrollment [27]. However, these studies did not address CCT barriers across multiple levels simultaneously. Given the abundance of literature and recent frameworks suggesting that multilevel interventions (MLIs) are needed to increase patient participation in trials [18,28,29,30,31], we used an intervention development guided by the SEM needed to systematically address multilevel barriers to minority patient CCT referral and enrollment.

Formative research is being used to inform the design and development of interventions aimed at reducing health disparities [22,32,33,34,35,36]. Engaging individuals who will be targeted by an intervention (e.g., end user) [34,35,36] is an important determinant of successful MLI implementation and outcomes [37]. Quantitative and qualitative research methods have been used to elicit in-depth perspectives on barriers to CCTs among cancer patients [38,39], cancer center physicians/clinical staff [12,15,16,17,40,41], community oncology providers [12,14,15,16,18,21], and community members [41,42]. Understanding local context is also an essential step in designing interventions deployed in real-world settings [43]. Thus, we conducted interviews with end users on an MLI designed to decrease barriers to referral and enrollment of Black/AA and Hispanic patients to CCTs at the patient, physician, institutional, and community level. This report (1) identifies barriers and facilitators to CCT referral and enrollment and (2) describes end-user feedback in the context of the SEM that was used to develop and refine the MLI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the ACT WONDER2S Study

Advancing Clinical Trials: Working Through Outreach, Navigation, and Digitally Enabled Referral and Recruitment Strategies (ACT WONDER2S) aims to reduce barriers to Black/AA and Hispanic patient CCT referral and enrollment through community outreach, education, and navigation efforts coupled with digital strategies for multiple target populations within the Moffitt Cancer Center (MCC) catchment area (intervention components described in Table 1). These include internal (MCC physicians, clinical research coordinators (CRCs), cancer patients) and external populations (community residents, community physicians). This study was approved by the Advarra Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Moffitt Cancer Center Scientific Review Committee (MCC #22140).

Table 1.

Overview of ACT WONDER2S.

2.2. Recruitment

The target sample sizes for each end-user group were guided by the principles of saturation (e.g., no new themes) in qualitative research, which is generally reached between 5 and 10 interviews per group of interest [44,45] The final sample sizes were as follows: community residents (number (n) = 5 Black/AA, n = 5 Hispanic); MCC patients (n = 5 Black/AA, n = 5 Hispanic); community physicians (n = 5 oncologists, n = 5 nononcologists); MCC CRCs (n = 10); and MCC physicians (n = 10) (n = 50 total). Recruitment strategies included flyer distribution in target clinics, social media advertisements, direct emails, and collaboration with MCC’s Patient and Family Advisory Council, advocacy, and support groups to distribute interview participation details. The MCC physician liaison team and two ACT WONDER2S physician coinvestigators also helped identify community physicians to advertise the interview opportunity across Tampa Bay and surrounding areas. MCC clinical departments and Clinical Trial Office leadership assisted in promoting the study to MCC physicians and CRCs. All end users provided verbal consent prior to interviews and were compensated with a USD 50 gift card via Greenphire ClinCard, a reloadable card that automates reimbursements and stipends for research participants.

2.3. Interviews

End users completed interviews (averaging 45 min) as part of the first of two interview phases in the ACT WONDER2S intervention design and development process. Interviews were conducted via phone or Zoom and were based on the SEM and simultaneously addressed (1) CCT knowledge, perceived barriers and facilitators to CCTs, current and potential outreach, referral, and enrollment strategies; and (2) feedback on how to design and refine several proposed ACT WONDER2S interventions before study launch. Interviews were conducted by two doctoral-level analysts (RB and CG) in the Participant Research, Interventions, and Measurement Core (PRISM) at MCC, who both have extensive training and experience in qualitative data collection. Initial drafts of the interview guides were developed by the study team, tailored to each end user group, and refined by PRISM. Structured questions were included to elicit specific information on perceived barriers and facilitators to CCTs and perspectives on the ACT WONDER2S intervention components. Quantitative scales (ranging from 1 (not helpful) to 5 (very helpful)) were developed by the study team to collect perceived helpfulness scores of the intervention components overall and by specific functionality to understand their utility and refine content. All questions (open- and closed-ended) were collected verbally during the interviews.

2.4. Quantitative Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of all end user groups were summarized by frequencies and percentages for categorical variables (e.g., sex, race, oncology specialty, etc.) and means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables (e.g., age [in years]). On a scale from 1 (not helpful) to 5 (very helpful), means of the scaled responses on the helpfulness of the ACT WONDER2S intervention components overall and by specific component features. Statistical analyses were performed via Research Electronic Data Capture (RED Cap), a web-based application software for building online surveys and databases [46].

2.5. Qualitative Analysis

All interviews were transcribed, deidentified, and analyzed following the tenets of applied thematic analysis [47]. Based on interview guides, emerging themes discovered during data collection, and study team meetings, an initial codebook was created and refined through the intercoder reliability process by study team members (RB and MM). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. An acceptable level of intercoder reliability was reached (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.82) after several rounds of coding [48]. Data were then coded using NVivo 12 Plus software and synthesized into themes and subthemes by RB, MM, and CG. Subsequently, findings were categorized into levels of the SEM framework (MG).

3. Results

A total of 50 interviews were completed with MCC physicians (n = 10), CRCs (n = 10), MCC patients (n = 10), community physicians (n = 10), and community residents (n = 10) (Table 2). Most end-user groups were equally compromised by sex (female (50%) and male (50%)), except for MCC physicians (30% female, 70% male). Besides community physicians, less than 40% of end users were white, and most identified as non-Hispanic. The mean years of employment at MCC was 8.8 for MCC physicians (SD + 5.79, range = 3–23) and 1.4 for CRCs (SD + 0.54, range = 1–2.5) (Appendix A and Appendix B). Most MCC physicians specialized in medical oncology (90%) and 50% classified themselves as MCC physician educators who lead training and education for early-career healthcare professionals. Among community physicians, 30% reported that their healthcare system offered clinical trials and 40% had led a therapeutic CCT in the last five years. However, 80% of community physicians referred patients to MCC for cancer care and 60% referred patients to a CCT outside of their healthcare system (Appendix C).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of participants from the ACT WONDER2S interviews.

3.1. Perceived Barriers, Facilitators, and Needs for Minority CCT Referral and Enrollment

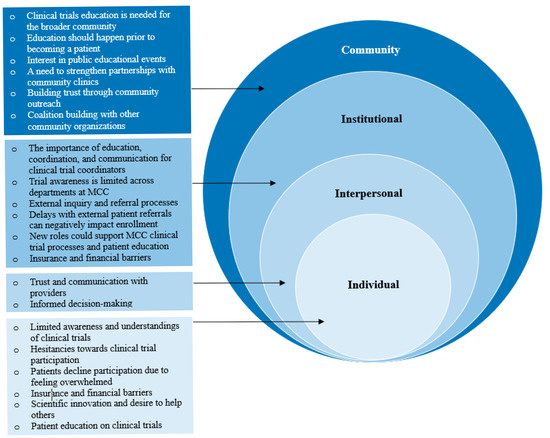

Themes emerged across all interviews and were organized by levels of the SEM as described below (Figure 1). Exemplary illustrative quotes are provided in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Themes grouped by levels of the socioecological model (SEM).

Table 3.

Exemplary quotes from participants grouped by levels of the socioecological (SEM) model.

3.1.1. Community Factors

Clinical trial education for the broader community was considered essential for increasing enrollment, with some end users emphasizing the need for CCT education prior to diagnosis. MCC patients and community residents expressed interest in attending educational events held by MCC, with some reporting positive experiences attending prior events. Building trust in the community was also described as important to foster diversity in CCTs; one community resident expressed that Black and Hispanic patients often lack trust in the medical system due to historical discrimination and persistent inequalities. End users emphasized strengthening partnerships with community clinics and suggested offering continuing medical education credits and utilizing patient navigators, health educators, community liaisons, or clinical trial champions for continued outreach. Another suggestion included establishing partnerships with other institutions or entities (e.g., American Cancer Society, local government agencies, community centers, churches, and universities) to reach those who may not know about MCC or CCTs.

3.1.2. Institutional Factors

While ongoing institutional coordination, communication, and education were identified as facilitators, perceived obstacles to CCT enrollment included high turnover for CRCs, complex scheduling processes, delays in receiving patient referrals/inconsistent referral patterns across institutions, and medical record sharing. Due to time constraints, MCC physicians recommended that patient navigators or health educators should educate patients on CCTs. MCC physicians and CRCs expressed limited awareness of CCTs and resources outside of their own departments, and some described relying on personal connections, research collaborations, and attendance at institutional department meetings and tumor boards for CCT information. Community physicians also reported limited awareness of availability and enrollment processes for MCC CCTs. While physicians and CRCs expressed that direct communication (e.g., email) was the most effective method of sharing information across departments and institutions, they desired an easier way to share details about upcoming CCTs due to difficulties ascertaining CCT information aside from personal connections (e.g., websites). End users also described insurance and financial factors as barriers to care, and community physicians expressed frustrations with referring patients to CCTs only to learn the patient’s insurance was not accepted by MCC.

3.1.3. Interpersonal Factors

Interpersonal factors emerged as themes across MCC patients and community residents. Both groups described that collaborating with a trusted provider would enhance their confidence in making informed decisions about CCT participation. They expressed needing information from their providers on clinical trial benefits, risks, safety, side effects, drug interactions, symptom management, findings from previous phases, effectiveness, and how quickly to expect results. Conversely, MCC physicians and CRCs also described the importance of teamwork and collaborating with principal investigators within their departments to effectively prioritize patients for trial candidate selection based on disease-related factors.

3.1.4. Intrapersonal Factors

Limited understanding and awareness of CCTs were noted by MCC patients, community residents, and community physicians. For instance, MCC patients and community residents were uninformed about the differences between clinical trials and standard treatment options, and community residents had less knowledge overall than MCC patients. They also reported hesitancies toward CCT participation related to potential risks (e.g., side effects, ineffectiveness), lack of trust in pharmaceutical companies/CCTs generally, discomfort in sharing health data, fear of disease progression, and feeling overwhelmed with diagnosis and treatment. Patient and physician education was described as necessary to address CCT misunderstandings, with some community physicians expressing that they were not always informed about available CCTs and associated processes. One MCC patient stated the importance of understanding the information they receive and emphasized simple, accessible language. Another patient suggested receiving CCT information through educational materials and having their questions answered during clinic visits.

3.2. ACT WONDER2S Intervention Feedback

3.2.1. Community

Half of MCC physicians were willing to use the precision engagement tool (mean = 3.0) (Table 4). While the overall mean helpfulness score was 3.75, the highest rated functionality was to include a list of community physicians who practice in areas with high proportions of minority patients and their associated referral patterns to facilitate targeted events and outreach (mean = 4.4). While some MCC physicians viewed the precision engagement tool as irrelevant to their role, they shared that the tool would be helpful to their department or across MCC as a whole. Suggestions included making the precision engagement tool more user-friendly, assigning designated staff to utilize the tool, and incorporating data on prevalent cancers across different geographic areas.

Table 4.

Participant feedback on the ACT WONDER2S digital tools.

Community Health Educators

All MCC patients and community residents believed that community health educators (CHEs) focused on CCT outreach and education would improve the patient experience. They felt CHEs could help connect them to social or financial resources (mean = 5.0 for both groups) and provide support during the new patient process (mean = 4.8 for both groups). Additional suggestions included on-site promotion of services, patient portal navigation, assisting with treatment logistics, and providing supportive care. MCC patients also expressed the need for language services and assistance with transferring international medical records to MCC (Table 5).

Table 5.

MCC patient and community resident feedback on community health educators for additional patient support.

3.2.2. Institutional

The portfolio profiler scored the highest for helpfulness among physicians and CRCs (mean = 4.0). The highest scoring functionality was to show the number of open MCC trials by department and by cancer characteristics (mean = 4.1). The recruitment dashboard had an overall helpfulness score of 3.62 among MCC physicians and CRCs, and the highest scoring functionality for both groups was to display demographic characteristics of all MCC patients relative to MCC trial enrollees (mean = 4.05). The eligibility criteria calculator was rated the lowest among MCC physicians (mean helpfulness score = 3.60), who described concerns with the tool’s practical value, noted limited time for modifying CCT protocols, and questioned whether this tool would impact CCT enrollment for patients who face other barriers to CCTs (e.g., access to care).

3.2.3. Institutional and Interpersonal

The trial connect portal was rated highly for helpfulness (mean = 4.27) and willingness to use the tool (mean = 4.07) among community physicians, MCC physicians, and CRCs. The highest rated feature was the ability for community physicians to send electronic patient referrals to MCC (mean = 4.60). The option for community physicians to search for open trials at MCC and communicate with MCC physicians about referrals was also rated highly (mean = 4.57; mean = 4.53). Suggestions included adding information on distance to the treatment site, social services, live CCT enrollment data, patients’ awareness of their referral to MCC, and information on specific biomarker criteria. End users also suggested easy integration of this tool into their workflow, continuous updates on the CCTs, and coordination with new patient intake.

3.2.4. Individual

The CHOICES DA was rated highly among MCC patients (mean overall helpfulness score = 4.53). The highest rated functionality was the ability to share self-reported barriers to receiving care with MCC clinical teams (mean = 4.9), followed by the option to send questions electronically before visits (mean = 4.6). A mean helpfulness score of 4.3 was given for (1) integrating CHOICES DA into the patient portal and (2) generating a list of CCT-related questions for patients to discuss with their clinical team. Additional suggestions included having in-depth information on trials, sharing patient testimonials, tracking patient interest in CCTs, finding ways to empower patients, communicating with other patients in the portal, and creating a forum where patients can ask questions anonymously.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to holistically obtain insights from the community and cancer center end users on CCT knowledge, barriers, and needs in parallel with input on interventions to reduce barriers to minority patient CCT referral and enrollment. A unique approach to this study was utilizing the SEM to guide the interviews and group emerging themes, which confirmed the presence of barriers and needs to CCT referral and enrollment among patients, physicians, CRCs, and community residents in the same study, supporting previous findings [1,12,13,14,16,17,31,38,41,42,49,50,51]. Integrating quantitative measures to assess the utility of the ACT WONDER2S components validated the value of the proposed interventions in reducing barriers to minority CCT referral and enrollment. This comprehensive approach informed ACT WONDER2S to systematically address the target populations’ key needs.

4.1. Community Outreach and Engagement Strategies

End users expressed the need for community outreach and engagement strategies to promote CCT awareness and for CHEs to provide additional patient support, similar to previous reports [16,30,52,53,54,55]. Fostering mutual relationships and trust between cancer centers and the communities they serve is crucial in embodying community needs and priorities into clinical and translational research [30,56] and can mitigate factors precluding CCT participation across institutions and their geographic catchment areas [57]. Yet, most interventions focused on increasing CCT awareness, referral, and enrollment in underrepresented populations have targeted barriers at the cancer patient and physician levels, respectively [58]. Thus, seeking input from our end users confirmed the value of incorporating community outreach and education strategies to enhance CCT education, improve the patient experience, and provide supportive care (e.g., resources on available programs and support services at MCC) as a component of ACT WONDER2S.

4.2. Institutional and Interpersonal Approaches

Reported institutional-level CCT challenges included a lack of awareness and resources on available CCTs, delays in receiving external referrals, and inconsistent referral patterns. Previous reports observed similar challenges, including difficulties understanding referral processes [59] and inconsistent referral processes limiting CCT opportunities for minority populations [16,17]. Notably, our findings suggest these institutional barriers are interwoven with interpersonal experiences, including a lack of ongoing communication between physicians and inconsistent communication preferences across institutions. For instance, some MCC and community physicians in this study preferred direct communication across institutions about available CCTs and eligibility. Similar findings were observed in a study that found that referring providers will normally send patients to oncologists with whom they have previously collaborated [19]. While end users reacted positively to the ACT WONDER2S institutional-level digital tools, the trial connect portal was ranked the most positively overall, likely because this tool addresses the most common challenges end users described at both the institutional level (e.g., facilitation of CCT identification, rapid referrals) and interpersonal level (e.g., providing a digital platform for community and MCC physicians to easily communicate about referrals and trial availability). Eliciting feedback on barriers in conjunction with the ACT WONDER2S digital tools underscores the potential impact of this tool in alleviating complex CCT referral processes and facilitating more streamlined communication processes.

4.3. Patient-Level CCT Decision-Making

Individual-level barriers to CCTs are consistent with the literature, including cancer patients’ limited CCT knowledge, awareness, and hesitancy, which can ultimately lead to patients declining participation [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. While previous interventions aimed to increase CCT awareness and knowledge for patients and providers, most studies relied on one or a few simple strategies, including patient navigation [60,61], decision support tools [23,24], or cultural/linguistic adaptations of single-session education sessions [28,61,62,63] to increase CCT knowledge. This study expands on previous work by engaging end users in refining digital and community interventions designed to increase CCT knowledge, awareness, and facilitate decision-making for minority patients, physicians, and community members. Collectively, all strategies were well received, adding utility to our MLI. Future studies seeking to evaluate MLIs should consider engaging end users early in the development process to facilitate the development of targeted interventions that address CCT knowledge barriers among relevant target populations.

4.4. Limitations and Strengths

This study is not without limitations. First, due to the small sample size, we recognize that our findings may not reflect some segments of the community and cancer center populations ACT WONDER2S aims to serve. While this study aimed to collect preliminary feedback on several topics, our sample size also limited the ability to detect statistically significant associations for our quantitative measures. ACT WONDER2S is also a single center study, and end-user perspectives may be limited to barriers and facilitators to CCTs at Moffitt Cancer Center, limiting the generalizability of our findings to other cancer center populations. Likewise, the landscape of CCTs continues to evolve, with more trials now including international sites [64,65], thus warranting future studies on how barriers and facilitators to CCTs may differ across regions. End users were also exclusively asked about ACT WONDER2S conceptually and were thus unable to provide personal experiences about using the digital tools or with community outreach and education directly. However, the qualitative interviews described in this study is the first of a two-phased approach for the ACT WONDER2S study development process; while not described here, phase 2 included additional qualitative interviews utilizing learner verification (LV) [66] and user-centered design (UCD) [67,68] approaches to finalize intervention components based on how they were refined from the feedback described in this study, which is a strength of our interview process.

5. Conclusions

In summary, findings reveal that community and cancer center populations face barriers to CCTs as posited within the SEM. Importantly, most end users were enthusiastic about leveraging community and digital strategies to reduce barriers to minority CCT referral and enrollment at the individual, interpersonal, institutional, and community levels. Our interviews confirmed the need for comprehensive approaches to address barriers to CCT referral and enrollment. This formative research approach is the basis for the ACT WONDER2S study that will be conducted across 14 geographic zones in the catchment area of our center through a cluster randomized design [69]. Our formative approach could serve as a model for developing future MLIs that aim to address further challenges to minority clinical trial referral and enrollment across levels of the SEM.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G., D.E.R. and S.T.V.; methodology, C.G., R.B., M.L.M., S.A.E., Y.Z., D.E.R. and S.T.V.; formal analysis, C.G., R.B., M.L.M. and Y.Z.; investigation, D.E.R. and S.T.V.; data curation, E.T.-K., C.G., R.B. and M.L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.; writing—review and editing, M.G., C.G., R.B., M.L.M., R.P.A., E.T.-K., K.T., L.F., Y.Z., S.A.E., D.E.R. and S.T.V.; visualization, M.G., D.E.R. and S.T.V.; project administration, R.P.A.; funding acquisition, D.E.R. and S.T.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institutes of Health (1U01-CA274971-02) and awarded to Susan Vadaparampil. This work has also been supported in part by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource, the Moffitt Merit Society Fund, and by the Participant Research, Interventions, and Measurement Core Facility at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helinski and approved by the Advarra Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Moffitt Cancer Center Scientific Review Committee (MCC #22140).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available to protect participant confidentiality and privacy. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCTs | Clinical Trials |

| MLIs | Multilevel Interventions |

| MCC | Moffitt Cancer Center |

| CRCs | Clinical Research Coordinators |

| ACT | Advancing Clinical Trials: Working Through Outreach, Navigation, and Digitally |

| WONDER2S | Enabled Referral and Recruitment Strategies |

Appendix A

Table A1.

MCC physician clinical characteristics (N = 10).

Table A1.

MCC physician clinical characteristics (N = 10).

| MCC Physician Clinical Characteristics | Statistic |

|---|---|

| Years at MCC; M (SD) range | 8.8 (5.79) 3–23 |

| Oncology specialty; n (%) | |

| Medical oncology | 9 (90%) |

| Radiology | 1 (10%) |

| Clinical Program; n (%) | |

| Blood and Marrow Transplant and Cellular Immunotherapy | 3 (30%) |

| Breast Oncology | 1 (10%) |

| Cutaneous Oncology | 1 (10%) |

| Genitourinary Oncology | 2 (20%) |

| Malignant Hematology | 1 (10%) |

| Radiation Oncology | 1 (10%) |

| Thoracic Oncology | 1 (10%) |

| Track; n (%) | |

| Clinical investigator | 4 (40%) |

| Physician educator | 5 (50%) |

| Physician scientist | 1 (10%) |

| Rank; n (%) | |

| Assistant member | 1 (10%) |

| Associate member | 9 (90%) |

Appendix B

Table A2.

MCC CRC clinical characteristics (N = 10).

Table A2.

MCC CRC clinical characteristics (N = 10).

| MCC CRC Clinical Characteristics | Statistic |

|---|---|

| Years at MCC; M (SD) range | 1.4 (0.54) 1–2.5 |

| Department; n (%) | |

| Malignant Hematology and Myeloid | 3 (30%) |

| Bone Marrow Transplant | 2 (20%) |

| Thoracic | 2 (20%) |

| Head and Neck | 2 (20%) |

| Phase 1 Clinical Trials | 1 (10%) |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Community physician clinical characteristics (N = 10).

Table A3.

Community physician clinical characteristics (N = 10).

| Participant Characteristic | Statistic |

|---|---|

| Age; M (SD) range (in years) | 45.7 (8.68) 33–58 |

| Practice Type; n (%) | |

| Private practice | 1 (20%) |

| Group practice | 4 (40%) |

| Medical center | 3 (30%) |

| Number of patients seen per month; M (SD) range | 451 (576.78) 160–2000 |

| Volume of cancer patients seen and/or diagnosed per month (nononcologists only, N = 6); M (SD) range | 3.88 (3.59) 0.3–10 |

| Health care system offers cancer clinical trials; n (%) | 3 (30%) |

| Has led a therapeutic cancer trial in the past 5 years; n (%) | 4 (40%) |

| Has referred a patient outside of their health system for cancer care; n (%) | 9 (90%) |

| Has referred a patient to MCC for cancer care; n (%) | 8 (80%) |

| Has referred a patient outside of their health system to a therapeutic cancer trial; n (%) | 6 (60%) |

| Has referred a patient to MCC for a therapeutic clinical trial; n (%) | 4 (40%) |

| Has attended a MCC physician CME activity; n (%) | 6 (60%) |

| Has engaged with a member of the MCC physician liaison team; n (%) | 5 (50%) |

References

- Hamel, L.M.; Penner, L.A.; Albrecht, T.L.; Heath, E.; Gwede, C.K.; Eggly, S. Barriers to Clinical Trial Enrollment in Racial and Ethnic Minority Patients with Cancer. Cancer Control. 2016, 23, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salihu, H.M.; Wilson, R.E.; King, L.M.; Marty, P.J.; Whiteman, V.E. Socio-ecological Model as a Framework for Overcoming Barriers and Challenges in Randomized Control Trials in Minority and Underserved Communities. Int. J. MCH AIDS 2015, 3, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allison, K.; Patel, D.; Kaur, R. Assessing Multiple Factors Affecting Minority Participation in Clinical Trials: Development of the Clinical Trials Participation Barriers Survey. Cureus 2022, 14, e24424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, D.; August, E.M.; Sehovic, I.; Green, B.L.; Quinn, G.P. A systematic review of the factors influencing African Americans’ participation in cancer clinical trials. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2013, 35, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.; Nguyen, C.; Lee, Y.-H.; Cooksey-James, T. A Review of Barriers to Minorities’ Participation in Cancer Clinical Trials: Implications for Future Cancer Research. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 18, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, D.P.; Chetty, U.; O’DOnnell, P.; Gajria, C.; Blackadder-Weinstein, J. Implicit bias in healthcare: Clinical practice, research and decision making. Futur. Health J. 2021, 8, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nipp, R.D.; Lee, H.; Gorton, E.; Lichtenstein, M.; Kuchukhidze, S.; Park, E.; Chabner, B.A.; Moy, B. Addressing the Financial Burden of Cancer Clinical Trial Participation: Longitudinal Effects of an Equity Intervention. Oncologist 2019, 24, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awidi, M.; Al Hadidi, S. Participation of Black Americans in Cancer Clinical Trials: Current Challenges and Proposed Solutions. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.G.; Howerton, M.W.; Lai, G.Y.; Gary, T.L.; Bolen, S.; Gibbons, M.C.; Tilburt, J.; Baffi, C.; Tanpitukpongse, T.P.; Wilson, R.F.; et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Cancer 2007, 112, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanarek, N.F.; Tsai, H.-L.; Metzger-Gaud, S.; Damron, D.; Guseynova, A.; Klamerus, J.F.; Rudin, C.M. Geographic Proximity and Racial Disparities in Cancer Clinical Trial Participation. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2010, 8, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabin, J.A.; Nosek, B.A.; Greenwald, A.G.; Rivara, F.P. Physicians’ implicit and explicit attitudes about race by MD race, ethnicity, and gender. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2009, 20, 896–913. [Google Scholar]

- Niranjan, S.J.; Wenzel, J.A.; Martin, M.Y.; Fouad, M.N.; Vickers, S.M.; Konety, B.R.; Durant, R.W. Perceived Institutional Barriers Among Clinical and Research Professionals: Minority Participation in Oncology Clinical Trials. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, e666–e675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.B.; Burris, J.L.; Borger, T.N.; Acree, T.; Abufarsakh, B.M.; Arnold, S.M. Perspectives of facilitators and barriers to cancer clinical trial participation: A mixed-methods study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, e23206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Chaudhary, P.; Quinn, A.; Su, D. Barriers for cancer clinical trial enrollment: A qualitative study of the perspectives of healthcare providers. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2022, 28, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, H.A.; McCaskill-Stevens, W.; Wolfe, P.; Marcus, A.C. Physician Perspectives on Increasing Minorities in Cancer Clinical Trials: An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Initiative. Ann. Epidemiol. 2000, 10, S78–S84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niranjan, S.J.; Martin, M.Y.; Fouad, M.N.; Vickers, S.M.; Wenzel, J.A.; Cook, E.D.; Konety, B.R.; Durant, R.W. Bias and stereotyping among research and clinical professionals: Perspectives on minority recruitment for oncology clinical trials. Cancer 2020, 126, 1958–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durant, R.W.; Wenzel, J.A.; Scarinci, I.C.; Paterniti, D.A.; Fouad, M.N.; Hurd, T.C.; Martin, M.Y. Perspectives on barriers and facilitators to minority recruitment for clinical trials among cancer center leaders, investigators, research staff, and referring clinicians: Enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT). Cancer 2014, 120 (Suppl. 7), 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, G.K.; Oberoi, A.R.; Finkelstein-Fox, L.; Park, E.R.; Nipp, R.D.; Moy, B. Qualitative study of Oncology Clinicians’ Perceptions of Barriers to Offering Clinical Trials to Underserved Populations. Cancer Control 2023, 30, 10732748231187829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, M.; D’aGostino, T.A.; Blakeney, N.; Weiss, E.S.; Binz-Scharf, M.C.; Golant, M.; Bylund, C.L. Impact of Primary Care Provider Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs about Cancer Clinical Trials: Implications for Referral, Education and Advocacy. J. Cancer Educ. 2014, 30, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, H.; Megally, S.; Plotkin, E.; Shivakumar, L.; Salgia, N.J.; Zengin, Z.B.; Meza, L.; Chawla, N.; Castro, D.V.; Dizman, N.; et al. Barriers to Clinical Trial Implementation Among Community Care Centers. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e248739-e. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A.R.; Sun, V.; George, K.; Liu, J.; Padam, S.; Chen, B.A.; George, T.; Amini, A.; Li, D.; Sedrak, M.S. Barriers to Participation in Therapeutic Clinical Trials as Perceived by Community Oncologists. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e849–e858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham-Erves, J.; Barajas, C.; Mayo-Gamble, T.L.; McAfee, C.R.; Hull, P.C.; Sanderson, M.; Canedo, J.; Beard, K.; Wilkins, C.H. Formative research to design a culturally-appropriate cancer clinical trial education program to increase participation of African American and Latino communities. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Ferrante, J.M.; Macenat, M.; Ganesan, S.; Hudson, S.V.; Omene, C.; Garcia, H.; Kinney, A.Y. Promoting informed approaches in precision oncology and clinical trial participation for Black patients with cancer: Community-engaged development and pilot testing of a digital intervention. Cancer 2023, 130, 3561–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, A.T.; Hawley, S.T.; Stableford, S.; Studts, J.L.; Byrne, M.M. Development of a Plain Language Decision Support Tool for Cancer Clinical Trials: Blending Health Literacy, Academic Research, and Minority Patient Perspectives. J. Cancer Educ. 2019, 35, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.; de la Riva, E.E.; Tom, L.S.; Clayman, M.L.; Taylor, C.; Dong, X.; Simon, M.A. The Development of a Communication Tool to Facilitate the Cancer Trial Recruitment Process and Increase Research Literacy among Underrepresented Populations. J. Cancer Educ. 2015, 30, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, N.J.; Boehmer, L.; Schrag, J.; Benson, A.B.; Green, S.; Hamroun-Yazid, L.; Howson, A.; Matin, K.; Oyer, R.A.; Pierce, L.; et al. An Assessment of the Feasibility and Utility of an ACCC-ASCO Implicit Bias Training Program to Enhance Racial and Ethnic Diversity in Cancer Clinical Trials. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, e570–e580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, C.; Pressman, A.; Hurley, P.; Garrett-Mayer, E.; Bruinooge, S.S.; Howson, A.; Kaltenbaugh, M.; Williams, J.H.; Boehmer, L.; Bernick, L.A.; et al. Increasing Racial and Ethnic Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion in Cancer Treatment Trials: Evaluation of an ASCO-Association of Community Cancer Centers Site Self-Assessment. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, e581–e588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaels, M.; Weiss, E.S.; Sae-Hau, M.; Illei, D.; Lilly, B.; Szumita, L.; Connell, B.; Lee, M.; Cooks, E.; McPheeters, M. Strategies for increasing accrual in cancer clinical trials: What is the evidence? Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerido, L.H.; He, Z. Improving Patient Participation in Cancer Clinical Trials: A Qualitative Analysis of HSRProj & RePORTER. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2019, 264, 1925–1926. [Google Scholar]

- Oyer, R.A.; Hurley, P.; Boehmer, L.; Bruinooge, S.S.; Levit, K.; Barrett, N.; Benson, A.; Bernick, L.A.; Byatt, L.; Charlot, M.; et al. Increasing Racial and Ethnic Diversity in Cancer Clinical Trials: An American Society of Clinical Oncology and Association of Community Cancer Centers Joint Research Statement. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2163–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, C.; Balls-Berry, J.E.; Nery, J.D.; Erwin, P.J.; Littleton, D.; Kim, M.; Kuo, W.P. Strategies addressing barriers to clinical trial enrollment of underrepresented populations: A systematic review. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2014, 39, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, A.P.; Fair, A.M.; Joosten, Y.A.; Dolor, R.J.; Williams, N.A.; Sherden, L.; Stallings, S.; Smoot, D.T.; Wilkins, C.H. A Multilevel Approach to Stakeholder Engagement in the Formulation of a Clinical Data Research Network. Med. Care 2018, 56, S22–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lange, A.H.; Teoh, K.; Fleuren, B.; Christensen, M.; Medisauskaite, A.; Løvseth, L.T.; Solms, L.; Reig-Botella, A.; Brulin, E.; Innstrand, S.T.; et al. Opportunities and challenges in designing and evaluating complex multilevel, multi-stakeholder occupational health interventions in practice. Work Stress 2024, 38, 352–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, E.; Mahony, L.O.; Riordan, F.; Flynn, G.; Kearney, P.M.; McHugh, S.M. What and how do different stakeholders contribute to intervention development? A mixed methods study. HRB Open Res. 2022, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laird, Y.; Manner, J.; Baldwin, L.; Hunter, R.; McAteer, J.; Rodgers, S.; Williamson, C.; Jepson, R. Stakeholders’ experiences of the public health research process: Time to change the system? Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, K.L.; Atkin, A.J.; Corder, K.; Suhrcke, M.; Turner, D.; van Sluijs, E.M.F. Engaging stakeholders and target groups in prioritising a public health intervention: The Creating Active School Environments (CASE) online Delphi study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, M.S.; Thompson, V.L.S. The science of stakeholder engagement in research: Classification, implementation, and evaluation. Transl. Behav. Med. 2017, 7, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.C.; Arnold, C.L.; Mills, G.; Miele, L. A Qualitative Study Exploring Barriers and Facilitators of Enrolling Underrepresented Populations in Clinical Trials and Biobanking. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, J.A.; Mbah, O.; Xu, J.; Moscou-Jackson, G.; Saleem, H.; Sakyi, K.; Ford, J.G. A Model of Cancer Clinical Trial Decision-making Informed by African-American Cancer Patients. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2014, 2, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprague, M.L.; Freeman, E.R.; Winkfield, K.M. Perceptions of Cancer Care and Clinical Trials in the Black Community: Implications for Care Coordination Between Oncology and Primary Care Teams. Oncologist 2017, 22, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, M.; Rivelli, A.; Molina, Y.; Ozoani-Lohrer, O.; Lefaiver, C.; Ingle, M.; Fitzpatrick, V. Trial staff and community member perceptions of barriers and solutions to improving racial and ethnic diversity in clinical trial participation; a mixed method study. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2024, 38, 101262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevalo, M.; Heredia, N.I.; Krasny, S.; Rangel, M.L.; Gatus, L.A.; McNeill, L.H.; Fernandez, M.E. Mexican-American perspectives on participation in clinical trials: A qualitative study. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2016, 4, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naderbagi, A.; Loblay, V.; Zahed, I.U.M.; Ekambareshwar, M.; Poulsen, A.; Song, Y.J.C.; Ospina-Pinillos, L.; Krausz, M.; Kamel, M.M.; Hickie, I.B.; et al. Cultural and Contextual Adaptation of Digital Health Interventions: Narrative Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e55130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvale, S. Interviews: An Introduction to Qualiitative Research Interviewing; Sage: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, K.K.S.; Abrahão, A.A. Research Development Using REDCap Software. Health Inform. Res. 2021, 27, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.; Namey, E. Applied Thematic Analysis; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, I.; Wright, J.; Nolan, M.B.; Eggen, A.; Bailey, E.; Strickland, R.; Traynor, A.; Downs, T. Overcoming Barriers: Evidence-Based Strategies to Increase Enrollment of Underrepresented Populations in Cancer Therapeutic Clinical Trials—A Narrative Review. J. Cancer Educ. 2019, 35, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendren, S.; Chin, N.; Fisher, S.; Winters, P.; Griggs, J.; Mohile, S.; Fiscella, K. Patients’ Barriers to Receipt of Cancer Care, and Factors Associated With Needing More Assistance From a Patient Navigator. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2011, 103, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.H.; Tisnado, D.M.; Keating, N.L.; Klabunde, C.N.; Adams, J.L.; Rastegar, A.; Hornbrook, M.C.; Kahn, K.L. Physician-reported barriers to referring cancer patients to specialists: Prevalence, factors, and association with career satisfaction. Cancer 2015, 121, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Odedina, F.T.; Wieland, M.L.; Barbel-Johnson, K.; Crook, J.M. Community Engagement Strategies for Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Populations. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2024, 99, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, M.D.; Patrick-Lake, B.; Abdulai, R.; Broedl, U.C.; Brown, A.; Cohn, E.; Curtis, L.H.; Komelasky, C.; Mbagwu, M.; Mensah, G.A.; et al. Inclusion and diversity in clinical trials: Actionable steps to drive lasting change. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2022, 116, 106740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl, S.A.; Nelson, B.A.; Patwary, T.R.; Amanuel, S.; Benz, E.J., Jr.; Lathan, C.S. Evolution of community outreach and engagement at National Cancer Institute-Designated Cancer Centers, an evolving journey. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cunningham-Erves, J.; Mayo-Gamble, T.L.; Hull, P.C.; Lu, T.; Barajas, C.; McAfee, C.R.; Sanderson, M.; Canedo, J.R.; Beard, K.; Wilkins, C.H. A pilot study of a culturally-appropriate, educational intervention to increase participation in cancer clinical trials among African Americans and Latinos. Cancer Causes Control. 2021, 32, 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, D.F.; Jackson, S.A.; Camacho, F.; Hall, M.A. Attitudes of African American and Low Socioeconomic Status White Women toward Medical Research. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2007, 18, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leader, A.E.; Brandt, H.M.; Briant, K.J.; Curry, G.; Ellis, K.; Gonzalez, E.T.; Guerra, C.E.; Harding, G.; Hull, P.C.; Israel, A.; et al. Community Outreach and Engagement at U.S. Cancer Centers: Notes from the Third Cancer Center Community Impact Forum. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2023, 32, 1777–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.M.; Nolan, T.S.; Gregory, J.; Joseph, J.J. Diversity in clinical trials: An opportunity and imperative for community engagement. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monreal, I.; Chappell, H.; Kiss, R.; Friedman, D.R.; Akesson, J.; Sae-Hau, M.; Szumita, L.; Halwani, A.; Weiss, E.S. Understanding the Barriers to Clinical Trial Referral and Enrollment Among Oncology Providers Within the Veterans Health Administration. Mil. Med. 2024, 190, e891–e898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, M.N.; Acemgil, A.; Bae, S.; Forero, A.; Lisovicz, N.; Martin, M.Y.; Oates, G.R.; Partridge, E.E.; Vickers, S.M. Patient Navigation As a Model to Increase Participation of African Americans in Cancer Clinical Trials. J. Oncol. Pract. 2016, 12, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouvini, R.; Parker, P.A.; Malling, C.D.; Godwin, K.; Costas-Muñiz, R. Interventions to increase racial and ethnic minority accrual into cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Cancer 2022, 128, 3860–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelto, D.J.; Sadler, G.R.; Njoku, O.; Rodriguez, M.C.; Villagra, C.; Malcarne, V.L.; Riley, N.E.; Behar, A.I.; Jandorf, L. Adaptation of a Cancer Clinical Trials Education Program for African American and Latina/o Community Members. Health Educ. Behav. 2015, 43, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, T.S.; Bell, A.M.; Chan, Y.; Bryant, A.L.; Bissram, J.S.; Hirschey, R. Use of Video Education Interventions to Increase Racial and Ethnic Diversity in Cancer Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2021, 18, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, C.H.; Werutsky, G.; Martinez-Mesa, J. The Global Conduct of Cancer Clinical Trials: Challenges and Opportunities. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2015, 35, e132–e139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izarn, F.; Henry, J.; Besle, S.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Blay, J.-Y.; Allignet, B. Globalization of clinical trials in oncology: A worldwide quantitative analysis. ESMO Open 2024, 10, 104086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavarria, E.A.; Christy, S.M.; Simmons, V.N.; Vadaparampil, S.T.; Gwede, C.K.; Meade, C.D. Learner Verification: A Methodology to Create Suitable Education Materials. HLRP Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2021, 5, e49–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walden, A.; Garvin, L.; Smerek, M.; Johnson, C. User-centered design principles in the development of clinical research tools. Clin. Trials 2020, 17, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabbs, A.D.V.R.; Myers, B.A.; MC Curry, K.R.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.R.; Hawkins, R.P.; Begey, A.B.; Dew, M.A. User-Centered Design and Interactive Health Technologies for Patients. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2009, 27, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollison, D.E.; Amorrortu, R.P.; Fuzzell, L.N.; Garcia, M.A.; Tapia-Kwan, E.S.; Zhao, Y.; Eschrich, S.A.; Gore, B.R.; Mittman, B.S.; Stanley, N.B.; et al. Abstract 4824: Multi-level intervention to increase minority cancer patient enrollment to clinical treatment trials—Study design considerations and baseline characteristics from the ACTWONDER2S Study. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).