Simple Summary

The high-level aims of the Advocate-BREAST initiative are to study and improve the overall experience of patients with breast cancer (BC) through education, shared decision making, and patient-centered clinical trials. Advocate-BREAST80+ is a survey substudy that specifically focused on the unique needs and perspectives of BC patients aged ≥80 years. Although patients aged ≥80 years experienced less anxiety and symptom-related distress compared with younger patients, they were significantly less satisfied with information regarding short and long term side effects of BC therapies, as well as the management of same. Older patients were significantly less likely to have participated in a clinical trial or be open to considering this option in future. Future research should address unique educational needs and barriers to research participation in older BC patients. Focused interviews could assist with better comprehension of the lived experience of these patients, given the smaller number of BC patients ≥80 years in many available databases.

Abstract

Background: There are limited evidence-based data to guide treatment recommendations for breast cancer (BC) patients ≥80 years (P80+). Identifying and addressing unmet needs are critical. Aims: Advocate-BREAST80+ compared the needs of P80+ vs. patients < 80 years (P80−). Methods: In 12/2021, a REDCap survey was electronically circulated to 6918 persons enrolled in the Mayo Clinic Breast Disease Registry. The survey asked about concerns and satisfaction with multiple aspects of BC care. Results: Overall, 2437 participants responded (35% response rate); 202 (8.3%) were P80+. P80+ were less likely to undergo local regional and systemic therapies vs. P80− (p < 0.01). Notably, P80+ were significantly less satisfied with information about the short and long-term side effects of BC therapies and managing toxicities. P80+ were also less likely to have participated in a clinical trial (p < 0.001) or to want to do so in the future (p = 0.0001). Conclusions: Although P80+ experienced less anxiety and symptom-related distress compared with P80−, they were significantly less satisfied with information regarding the side effects of BC therapies and their management. P80+ were significantly less likely to have participated in a clinical trial or be open to considering this option. Future studies should address educational needs pertaining to side effects and barriers to research participation in P80+.

1. Introduction

In 2023, approximately 297,790 American women were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer (BC) [1], and ~12% were aged ≥80 years [2]. Despite important advances in BC care, there are limited evidence-based data to guide treatment recommendations in patients ≥80 years (P80+), which can lead to both under and over-treatment [3], as well as limited data on these patients’ perspectives on cancer and cancer therapy. Unique challenges in this patient population include concerns regarding treatment-related toxicities, comorbidities and limited life expectancy, and underrepresentation in clinical trials [4]. Furthermore, although BC biology in older women is often indolent [5], older patients may experience worse BC-specific outcomes when controlling for disease subtype and stage [4,6]. Older women with BC may also differ from younger women in their educational needs, but there are limited data regarding these needs [7]. Online patient resources devoted to this population are limited [8]. Therefore, identifying and addressing gaps will be a critical step toward the optimization of care for older BC patients and should be a clinical and research priority [9].

The Advocate-BREAST project, “Advocates and Patients’ Advice to Enhance Breast Cancer Care Delivery, Patient Experience and Patient Centered Research”, is a collaboration between breast oncologists at Mayo Clinic in Rochester (MCR), Minnesota, USA and Mayo Clinic BC Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) advocates. Its high level aims are to study and improve the overall patient experience through education, shared decision-making, and patient-centered clinical trials. The primary objective is to identify areas of unmet need in BC care delivery and research with the goal of improving patient experience and driving further research. We initially conducted a patient experience survey in BC survivors enrolled in the Mayo Clinic Breast Disease Registry (MCBDR) [10]. This paper presents the results of Advocate-BREAST80+, a survey substudy that compares the perspectives of P80+ with BC patients < 80 years (P80−) after having experienced a diagnosis of BC.

2. Methods

2.1. Advocate-BREAST Project Approach and Committee Formation

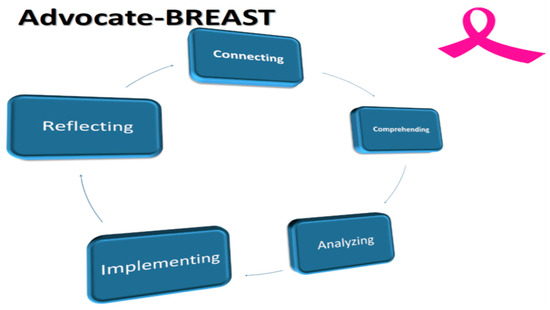

The Advocate-BREAST project uses a five-step framework: Connecting, Comprehending, Analyzing, Implementing, and Reflecting (Figure 1). The overall goals are outlined in Figure 2. The Mayo Clinic project management team included two Breast Medical Oncologists [C.O.S. and K.J.R.], a Research Program Co-Ordinator [N.L.], a statistician [R.V.], and two senior Mayo Clinic SPORE BC advocates [M.L.S. and C.C.].

Figure 1.

The Advocate-BREAST Project. Legend: The Advocate BREAST project involves 5 distinct steps as follows: 1. Connecting with advocates and patients to determine scope and focus of projects; 2. Comprehending the lived experience of EBC and MBC patients; 3. Developing, circulating surveys and analyzing results in partnership with patient advocates; 4. Implementing results to promote patient centered BC research and treatment; 5.Reflecting on process and considering ways to improve and repeat cycle.

Figure 2.

Goals of the Advocate BREAST Project.

2.2. Study Design and Recruitment

The Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center (MCCC) is an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center with three main campuses in Minnesota (MCR), Florida and Arizona. We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients enrolled in the MCBDR, a prospective longitudinal cohort study that enrolls patients with stage 0–4 BC who were seen at least once at MCR within one year of diagnosis (2001–2021). Informed consent was obtained prior to registry enrollment. Patients were excluded if they had received an initial BC diagnosis more than one year prior, did not speak English, or did not live within the USA.

2.3. Data Collection and Processing

In MCBDR, demographic information, histopathological tumor characteristics and treatment-related factors are abstracted from the electronic medical record by trained nursing personnel. For this study, we accessed age, sex, date of BC diagnosis and disease stage. Patients were classified into three groups: ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS; stage 0), invasive non-metastatic BC (stage 1–3), and metastatic breast cancer (MBC; stage 4) at time of survey completion. ZIP codes of residence were mapped to rural–urban commuting area (RUCA) codes, and rurality was defined as RUCA code 10 (i.e., >60 min road travel (one-way) to the closest edge of an urbanized area) [11]. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB1815-04) reviewed and approved this study. Data were handled in a manner consistent with both US laws and the Declaration of Helsinki.

In addition to medical chart review, participants completed a survey developed by the study team (see below) addressing satisfaction with (i) multiple aspects of cancer care delivery and (ii) the education and/or support they receive(d) regarding practical, financial, emotional, societal and spiritual concerns linked to their diagnosis. Racial/ethnic, educational, rural/urban, and financial status data were used to inform the development of novel resources to address patient-reported gaps in care. Participants were also asked to rank potential QI projects in order of the likelihood the proposal could improve quality of life for patients and their families. Patients were also asked to comment on how care for BC patients might be improved, and their thoughts on what research topics should be prioritized. Feedback from P80+ was initially reviewed by the research program coordinator, who categorized the content. The Breast Medical Oncology team further reviewed the qualitative data and classified each theme as either major or minor based on the number of responses. Comments regarding suggestions for further research were noted separately. Responses were collected via anonymous local language questionnaires.

2.4. Survey

Our 23-page survey, containing 147 items, was developed to assess patient levels of concern and satisfaction with various aspects of their BC diagnosis and treatment. We used REDCap, a secure web application for developing and managing online surveys and databases that is specifically tailored to support online and offline data capture for research studies. A questionnaire was electronically sent to all MCBDR participants who were consented, alive, and had an e-mail address on file on 12/9/2021. Non-respondents were sent two reminder e-mails on 12/16 and 12/23/2021.

The questionnaire captured: 1. Demographic Information; 2. BC Treatment; 3. Concerns Regarding Side Effects of BC Treatment; 4. BC Clinical Care Concerns ([i] level of symptoms experienced during the first year after BC diagnosis and [ii] level of concern regarding health-related, practical, financial, emotional, societal and spiritual issues related to BC during that time); 5. Clinical Care BC Patient Experience ([i] overall satisfaction with BC care, [ii] satisfaction with information and support received from the care team as regards symptom management during first year after BC diagnosis, and [iii] satisfaction with information and support received from BC care team as regards practical, financial, emotional, societal and spiritual issues related to BC during the first year after diagnosis); 6. Ranking of Proposed QI Projects; 7. Integrative Medicine; 8. Medical Second Opinions; 9. Clinical Trial Participation; and 10. Thoughts/suggestions (patient comments) on [i] how care for BC patients could be improved and [ii] what research topics should be prioritized in BC.

Sections 3–5 of the questionnaire contained different numbers of items to be scored, each on a 10-point Likert scale. For Section 3 and some items in Section 4, respondents were asked to score their responses (0 = not at all concerned, 10 = highly concerned). Other items in Section 4 related to symptom severity, and were scored accordingly (0 = none, 10 = [symptom] as bad as I can imagine). For Section 5, respondents were asked to rate their overall satisfaction with their BC care (0 = very dissatisfied, 10 = extremely satisfied). For the satisfaction data, scores of 0–3 were rated as low satisfaction, scores of 4–6 were rated as moderate satisfaction, and scores of 7–10 were rated as high satisfaction. Section 6 of the questionnaire asked respondents to rate the likelihood that a proposed QI project would improve patient care (0 = none, vs. 10 = as much as I can imagine).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Participants were dichotomized into two groups based on age at survey completion: those younger than 80 (hereafter referred to as P80−) and those 80 or older (P80+). Data were summarized using frequencies and percents for categorical variables and means, standard deviations (SDs), medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. We compared demographic and clinical characteristics across survey response status using chi-square tests of significance. Amongst those who returned surveys, associations of survey responses with dichotomized age were first univariately examined using two-sample t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. All statistical tests were two-sided, and all analyses were carried out using the SAS System (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

A total of 6918 MCBDR participants (6877 female) were sent surveys, and 2450 responses (response rate = 35.4%) were received. Thirteen males were excluded, resulting in a final study size of 2437. Overall, the mean age of participants was 64 (SD 11.8), and 202 (8.3%) were aged ≥80 years. The mean time from BC diagnosis at the time of the survey was 93.3 months (SD 70.2). Comparisons of the demographic and clinical characteristics of P80+ vs. P80− across survey response status are provided in Table 1. Survey responses are listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic Information.

Table 2.

Survey Responses.

Advocate-BREAST80+ Substudy Results

- Demographic Information

Compared with responding P80−, responding P80+ were more likely to be white (p = 0.0136), widowed (<0.0001), living in a rural location (0.0136), and initially diagnosed with BC ≥ 24 months prior to completing the survey (<0.0001). For P80+, the mean time from BC diagnosis at the time of survey completion was 128.5 months (SD 74.4) compared with 90.1 months (SD 68.9) for P80− (p ≤ 0.001). The BC stage distribution for patients (Stage 0–4) was similar in P80+ compared to P80− (p = 0.2571). Based on these results, the following variables were used to calculate propensity scores for subsequent weighted analyses: race, marital status, religion, time since BC diagnosis, primary BC treatment location, and recommendation status for surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, endocrine therapy, biologic therapy, and immunotherapy.

- Treatment Recommendations

Overall, P80+ were less likely to report that they had been advised to undergo local regional and systemic therapies than P80−. Specifically, surgery was recommended less frequently for P80+ compared with P80− (p = 0.0062, Table 1). However, when surgery was recommended, P80+ were as likely to proceed with the same as P80− (p = 0.5643). Adjuvant radiation therapy was also less likely to be recommended for P80+ compared with P80− (p = 0.0037); however, there was no difference between the groups regarding the likelihood of proceeding with radiation therapy if advised (p = 0.6635).

Regarding systemic therapies, P80+ were less likely to be advised to pursue chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted biologic therapy or endocrine therapy compared with P80− (p ≤ 0.0001 for each of these treatments). Furthermore, although P80+ were less likely to proceed with recommended endocrine therapy (p = 0.0011), targeted biologic therapy (p = 0.0940), and immunotherapy (p = 0.0015), they were as likely as P80− to proceed with chemotherapy if recommended (p = 0.1641).

- Symptom Severity

Overall, the most severe symptom experienced by patients in their first year following BC diagnosis was hair loss/thinning, followed by hot flashes, eyebrow/eyelash thinning, sexual dysfunction, cognitive/memory issues, neuropathy and lymphedema. Compared with P80−, P80+ were significantly less impacted by hot flashes, eyebrow/eyelash thinning, sexual dysfunction, cognitive/memory issues and lymphedema (p < 0.0001 each).

- Level of Concern Regarding Issues within the First Year after Breast Cancer Diagnosis

The main concerns patients of all ages recalled in the first year following their BC diagnosis were (i) fear of BC recurrence/spread, (ii) concerns about loved ones coping, (iii) diagnosis and prognosis, (iv) fear of dying of BC, (v) weight/physical fitness, and vi) their emotional health. P80+ were significantly less impacted than P80− regarding these issues (p < 0.0001 for each item), although they were still identified as top concerns overall.

- Overall Satisfaction with BC Patient Experience

Patients reported a high level of overall satisfaction with BC care received (>90%). Specifically, P80+ reported higher overall satisfaction with BC care than P80− (p = 0.0015). P80+ reported similar satisfaction overall with the information and support received from their cancer care teams compared to P80− (0.9826).

- Satisfaction with BC Information and Support Received Regarding Symptoms/Side Effects of Treatment

In the first year after BC diagnosis, patients of all ages were least satisfied with the information provided regarding (i) the side effects of immunotherapy, (ii) the side effects of targeted biologic therapies, (iii) sexual dysfunction, (iv) the long-term side effects of chemotherapy, and (v) eyebrow/eyelash thinning.

When compared with P80−, P80+ were significantly less satisfied with information they received regarding (i) the potential side effects of immunotherapy (p = 0.0320), targeted biologic therapies (p = 0.008), sexual dysfunction (p < 0.0001), peripheral neuropathy (p < 0.0001), hair loss/thinning (p = 0.0030), lymphedema (p < 0.0001), hot flashes (p < 0.0001), the short and long-term side effects of radiotherapy (p < 0.0001 and 0.0277, respectively) and the short term side effects of chemotherapy (p < 0.001).

- Satisfaction with BC Support Received Regarding Concerns

In the first year after BC diagnosis, patients of all ages reported high satisfaction overall with support provided (~90%). Specifically, there were no significant differences between P80+ and P80− regarding satisfaction with the availability of information pertaining to their BC diagnosis, access to their care team, and the amount of information available regarding their treatment plan. However, P80+ reported lower satisfaction with information provided regarding genetic testing (self) (p = 0.0239).

- Ranking of Quality Improvement (QI) projects

Compared to P80−, P80+ similarly prioritized proposed QI interventions focusing on (i) the provision of lifetime access to online educational resources (p = 0.2588). QI interventions focused on (i) wellness for early breast cancer (EBC) and metastatic breast cancer (MBC) patients and (ii) educational, practical, emotional and holistic support for patients with MBC were also considered high priority but did not differ across age.

- Integrative Medicine

P80+ were less likely to have visited an integrative medicine provider for BC treatment than P80− (p = 0.0003). P80+ who met with integrative medicine were as likely to have taken supplements or vitamins recommended as P80− (p = 0.0056). Despite lower care satisfaction reported overall compared with P80− (p = 0.0002), 80% of P80+ were satisfied/very satisfied with care received from integrative medicine. However, data from this section should be cautiously interpreted given the small number of P80+ who responded to these questions.

- Medical Second Opinions and Clinical Trial Participation

P80+ were less likely to have received a second opinion (p < 0.0001). P80+ were also more likely to have received assistance from a patient advocate regarding BC-related logistics and treatment decisions (p = 0.0029).

Regarding clinical trials, 40.5% of P80+ reported prior study participation vs. 47.2% of P80− (p < 0.001), and P80+ were less open to participating in a trial in the future (p = 0.0001) compared with P80− (18.6% responded “No” and 40.7% responded unsure).

- Qualitative Data: Suggestions to Improve BC Care and Prioritization for BC Research

Overall, 77 of 202 P80+ answered the open-ended survey questions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Qualitative Data from Survey Respondents Aged 80+ Years.

The major themes identified were (1) BC Education, (2) Side Effects of BC Treatment, and (3) Emotional Support During and After BC Diagnosis. Regarding BC education, suggestions included avoiding multiple printed resources unrelated to the patient’s diagnosis and treatment plan, instead providing tailored information based on patient preferences (more vs. less information). Patients also advised that clinicians use less medical terminology and provide thorough information regarding all treatment options. Regarding managing the side effects of BC treatment, suggestions included more detailed information regarding the short and long-term sequelae of local and systemic therapy. Regarding emotional support, patients noted the importance of ongoing access to BC and community support groups. The need for provider education and ongoing efforts to optimize emotional support for BC patients was also highlighted. Other themes included (4) Care Concerns/Provider Sensitivity (need to consider patient frailty, vulnerability and increased susceptibility to discomfort during medical procedures), (5) Survivorship/Long Term Sequelae of BC treatment (advice about surveillance, prosthesis selection, etc.), (6) Diversity, Ethnicity and Inclusion (questions regarding the applicability of BC data for ethnic minorities), (7) BC Care Access (faster surgery and test results), (8) Dense Breast Tissue Screening (insurance coverage), (9) Diet and Exercise (nutrition consultations) and (10) Sexual Dysfunction. Regarding thoughts on what areas of research should be championed, respondents prioritized focusing on efforts to determine the causes of BC, as well as to prevent and cure the same.

4. Discussion

We present the results of a large patient experience survey completed by ~2500 BC patients, of whom >200 were P80+; a comparison of both groups shows that P80+ appear to be a distinct population with regard to demographics, treatment-related symptoms, and unmet educational needs. Differences in engagement with integrative medicine and clinical trial participation, as well as the likelihood of pursuing a medical second opinion, were also noted between both groups. Based on our findings, ways to improve BC care in P80+ include: (i) refining patient education materials and (ii) identifying and reducing unique barriers to research participation. On review of the qualitative data, the need for ongoing emotional support during and after BC treatment was also found to be a priority for this population.

A strength of this substudy is the number of P80+ who responded to the survey, as well as the qualitative data provided from P80+; the latter helped identify relevant themes in this understudied population. Other strengths include the high survey response rate (35%) and the inclusion of rural-dwelling BC patients (15.3% of respondents were P80+), as these patients are often underrepresented in BC care delivery research. Notably, our definition of rurality was strict (RUCA code of 10) and did not include small towns (RUCA codes 7–9 inclusive). Regarding study limitations, most survey respondents had stage 0–3 BC (n = 196; 97%); therefore, concerns germane to P80+ with MBC are not well evaluated. Furthermore, as most survey respondents were married/widowed and Caucasian Christians living in the Midwest of the US, our conclusions may not be generalizable. Therefore, a future study should enroll a more ethnically, racially, and geographically diverse cohort of P80+. Although our survey response rate of 35% was higher than observed in some studies, the substantial number of non-responders could also have contributed to response bias. The higher rate of clinical trial participation reported in our study could also have been a function of response bias, as people who participate in clinical trials are likely more willing to complete a survey. In addition, 155 (76.7%) of the P80+ survey respondents were diagnosed 5–10 years ago, which may have led to recall bias when reporting BC-related symptom severity and concerns. Nevertheless, the inclusion of these patients is important to capture the unique perspectives of P80+ survivors.

P80+ were less likely than younger patients to report that they had been advised to pursue all types of BC therapy. However, when they recalled that this had been recommended, these older patients were as likely as P80− to report that they did indeed receive surgery, radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy. Conversely, if they reported that they had been recommended to receive endocrine therapy or immunotherapy, P80+ were less likely than P80− to report that they had indeed received that treatment. The reasons for therapy decline in older patients may include the duration of therapy, perceived unclear benefit of therapy, concerns regarding the potential for therapies to exacerbate preexisting medical conditions and/or cause new problems, financial concerns, and communication barriers (e.g., hearing or visual impairments that make it difficult to understand the benefits of a given cancer treatment) [12,13]. While the avoidance of potentially toxic therapies is often appropriate in P80+ as risks may outweigh benefits, some older BC patients do benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy [14,15]. The ADVANCE (ADjuVANt Chemotherapy in the Elderly) trial assessed the feasibility of two (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy regimens in parallel-enrolling cohorts of older persons (≥70 years) with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative BC [16]. Although neither regimen met target feasibility goals, trials such as ADVANCE inform the development of tolerable, evidence-based regimens for older BC patients who need chemotherapy. Better age-specific data and personalized decision tools are needed to assist with provider and patient decision-making [17,18,19], as well as the greater integration of existing tools into oncology clinical practice [20,21,22].

From an educational perspective, the level of satisfaction regarding information and support provided to address BC therapy side effects was lower in P80+ than in P80−. Specifically, P80+ were significantly less satisfied with information regarding the potential side effects of immunotherapy, targeted biologic therapies, the short and long-term side effects of radiotherapy, and the short and long-term side effects of chemotherapy. As these topics encompass much of what is discussed at the initial BC consultation(s), the provision of improved educational resources tailored to older patients (e.g., larger print materials and PC use if internet access is available) with additional concessions (e.g., longer visit times and nurse navigator assistance) may improve comprehension and retention of information. Furthermore, a short interval follow-up visit with a care team representative may aid patient decision-making and decrease overwhelming feelings. Even though P80+ were less likely to request a second opinion, those that obtained the same reported a similar level of satisfaction to P80−. A second consultation with an oncology provider provides additional education and may reinforce initial recommendations and improve comprehension [23,24]. A “refresher” visit with a care team representative shortly after the initial consultation to provide a reminder regarding accessing suitable educational materials/resources could be helpful. As P80+ in our substudy also reported less satisfaction with information/education regarding sexual dysfunction, peripheral neuropathy, hair loss/thinning, lymphedema, and several other topics compared with P80−, an institutional pilot study focusing on the delivery of age-appropriate, concise education for P80+ could be implemented. An initial approach could be to focus on one side effect, with patient satisfaction levels assessed thereafter. Given our aging population, strategies focusing on catering to the educational needs of elderly BC patients will increasingly need to be prioritized [25,26].

With regard to the main concerns experienced during the first year after a BC diagnosis, although P80+ reported less anxiety and symptom-related distress compared with P80−, their primary concerns were similar (i.e., emotional distress and anxiety related to the BC diagnosis). Despite the lower levels of emotional distress experienced overall, ongoing access to psychosocial support (in person or virtual) was valued. The importance of “wellness” was stressed, with physical fitness reported as a leading concern. Although P80+ were less inclined to visit an integrative medicine provider, the majority who did were satisfied with their experience; however, these results are based on a relatively small sample size. Given the many benefits of integrative medicine regarding holistic health and pain and symptom management (including for cancer patients) [26,27], efforts to educate older patients and foster connections with licensed professionals should be encouraged.

With regard to clinical trial participation, 60 (40.5%) P80+ reported that they had already participated in a trial (a higher proportion than the general population), but these older patients were significantly less open to doing so in the future compared with P80− (16 [18.6%] stated no and 35 [40.7%] were unsure). Unfortunately, the percentage of P80+ who have participated in/are open to participating in clinical trials is considerably lower in underserved and/or ethnically diverse patients [28,29]. Initiatives to prioritize the inclusion of older persons in research are urgently needed.

P80+ and P80− were well-aligned in recommending the implementation of the following QI initiatives: (i) the provision of lifetime access to online concise patient educational resources; (ii) educational, practical, emotional and holistic support programs for MBC patients; and (iii) BC Wellness Programs for EBC and MBC patients. This implies that, irrespective of age, patients with BC prioritize concise educational resources, continuity of care, ongoing psychological support, and holistic care.

5. Conclusions

Efforts to refine care and to address unique challenges in older patients must be a clinical and research priority. Strategies focusing on tailoring educational materials to BC patients diagnosed in their 80s and 90s should be prioritized, as should initiatives that aim to increase clinical trial accrual and promote psychological well-being for P80+. In the future, focused interviews with P80+ could inform interventions to enhance continuity of care, communication, holistic care, and long-term psychosocial support.

Author Contributions

Conception or design of the work: C.C.O., R.A.V., K.J.R., M.L.S. and C.C.; data collection: C.C.O., R.A.V. and N.L.L.; data analysis and interpretation: C.C.O., R.A.V., N.L.L., K.J.R., J.E.O., M.L.S. and C.C.; drafting the article: C.C.O., R.A.V., N.L.L., K.J.R. and J.E.O.; critical revision of the article: C.C.O., R.A.V., N.L.L., M.L.S., C.C., F.J.C., J.E.O., S.D., A.J. and K.J.R.; final approval of the version to be published: C.C.O., R.A.V., N.L.L., M.L.S., C.C., F.J.C., J.E.O., S.D., A.J. and K.J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Mayo Clinic Population Sciences Grant (P30 CA015083).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was reviewed by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB 1815-04).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment to the registry.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets for this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center pilot grant (P30 CA015083).

Conflicts of Interest

Ciara C. O’Sullivan—Dr. O’Sullivan has received research funding through Mayo Clinic from Lilly, Seagen Inc., Bavarian Nordic, Minnemarita Therapeutics, nFerence, AstraZeneca and Biovica. Mary Lou Smith—Serves on consulting/advisory boards with Bayer, Eisai, Novartis, Pfizer, and Rising Tide; received institutional grant funding from Genentech, Foundation Medicine, Novartis, Seagen, Eli Lilly, Exact Sciences, Daiichi, ECOG-ACRIN Medical Research Foundation, Pfizer, Prelude DX, International Association for Study of Lung Cancer, Conquer Cancer Foundation, and Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation; serves as Co-Chair of Cancer Research Advocate Committee and Member of Breast Core Committee, ECOG ACRIN Research Group; was a member of the following: Breast Cancer Treatment Guidelines Committee, National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN); External Advisory Board, University of Wisconsin Comprehensive Cancer Center; Board of Directors, National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers; Board of Directors, Gateway for Cancer Research; NCI BOLD Task Force; Mayo Clinic Breast SPORE; Steering Committee, ASCO TAPUR Study; Stakeholder Advisory Board, COMET study; Advisory Board, PRO-TECT study; Advisory Committee, NCI-NCORP; Breast Cancer Guidelines Advisory Group, American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO); EVOLV Study; NCI Tolerability Consortium; and Women’s Advisory Board, TMIST study. Janet E. Olson—Research support: Grail, Inc. Research grant: Exact Sciences, Exact-001.

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolo, A.; Rosso, C.; Voutsadakis, I.A. Breast Cancer in Patients 80 Years-Old and Older. Eur. J. Breast Health 2020, 16, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shachar, S.S.; Hurria, A.; Muss, H.B. Breast Cancer in Women Older Than 80 Years. J. Oncol. Pract. 2016, 12, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, R.A.; Keating, N.L.; Lin, N.U.; Winer, E.P.; Vaz-Luis, I.; Lii, J.; Exman, P.; Barry, W.T. Breast cancer-specific survival by age: Worse outcomes for the oldest patients. Cancer 2018, 124, 2184–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Herck, Y.; Feyaerts, A.; Alibhai, S.; Papamichael, D.; Decoster, L.; Lambrechts, Y.; Pinchuk, M.; Bechter, O.; Herrera-Caceres, J.; Bibeau, F.; et al. Is cancer biology different in older patients? Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e663–e677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleurier, C.; De Wit, A.; Pilloy, J.; Boivin, L.; Jourdan, M.L.; Arbion, F.; Body, G.; Ouldamer, L. Outcome of patients with breast cancer in the oldest old (≥80 years). Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 244, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.J.; D’Alimonte, L.; Angus, J.; Paszat, L.; Soren, B.; Szumacher, E. What do older patients with early breast cancer want to know while undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy? J. Cancer Educ. 2011, 26, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskin, A.S.; Wang, T.; Mott, N.M.; Hawley, S.T.; Jagsi, R.; Dossett, L.A. Gaps in Online Breast Cancer Treatment Information for Older Women. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagegni, N.A.; Peterson, L.L. Age-related disparities in older women with breast cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2020, 146, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, C.C.; Larson, N.; Vierkant, R.A.; Smith, M.L.; Chauhan, C.; Couch, F.J.; Olson, J.; Ruddy, K.J. Advocate-BREAST: Advocates and Patients’ Advice to Enhance Breast Cancer Care Delivery, Patient Experience and Patient Centered Research by 2025. Cancer Res. 2023, 83 (Suppl. S5), P6-05-41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Dataset) USDA Economic Research Service. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. 2022; Economic Research Service, Department of Agriculture. Available online: https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- White, M.J.; Kolbow, M.; Prathibha, S.; Praska, C.; Ankeny, J.S.; LaRocca, C.J.; Jensen, E.H.; Tuttle, T.M.; Hui, J.Y.C.; Marmor, S. Chemotherapy refusal and subsequent survival in healthy older women with high genomic risk estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 198, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, N.; Kozikowski, A.; Barginear, M.F.; Fishbein, J.; Pekmezaris, R.; Wolf-Klein, G. Reasons for Chemotherapy Refusal or Acceptance in Older Adults With Cancer. South. Med. J. 2017, 110, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, M.; Shimomura, A.; Tokuda, E.; Horimoto, Y.; Kawamura, Y.; Ishizuka, Y.; Sekine, K.; Obayashi, S.; Kojima, Y.; Uemura, Y.; et al. Is adjuvant chemotherapy necessary in older patients with breast cancer? Breast Cancer 2022, 29, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Lakritz, S.; Schreiber, A.R.; Molina, E.; Kabos, P.; Wood, M.; Elias, A.; Kondapalli, L.; Bradley, C.J.; Diamond, J.R. Clinical outcomes of adjuvant taxane plus anthracycline versus taxane-based chemotherapy regimens in older adults with node-positive, triple-negative breast cancer: A SEER-Medicare study. Eur. J. Cancer 2023, 185, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, R.A.; Li, T.; Sedrak, M.S.; Hopkins, J.O.; Tayob, N.; Faggen, M.G.; Sinclair, N.F.; Chen, W.Y.; Parsons, H.A.; Mayer, E.L.; et al. ‘ADVANCE’ (a pilot trial) ADjuVANt chemotherapy in the elderly: Developing and evaluating lower-toxicity chemotherapy options for older patients with breast cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2023, 14, 101377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid-Agboola, C.; Klukowska, A.; Malcolm, F.L.; Harrison, C.; Parks, R.M.; Cheung, K.L. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment for Older Women with Early-Stage (Non-Metastatic) Breast Cancer-An Updated Systematic Review of the Literature. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 8294–8309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepin, H.; Mohile, S.; Hurria, A. Geriatric assessment in older patients with breast cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2009, 7, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Okonji, D.O.; Sinha, R.; Phillips, I.; Fatz, D.; Ring, A. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in 326 older women with early breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohile, S.G.; Dale, W.; Somerfield, M.R.; Schonberg, M.A.; Boyd, C.M.; Burhenn, P.S.; Canin, B.; Cohen, H.J.; Holmes, H.M.; Hopkins, J.O.; et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2326–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, S.; Lawn, S.; Chan, R.; Koczwara, B. The role of comorbidity assessment in guiding treatment decision-making for women with early breast cancer: A systematic literature review. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Sun, C.L.; Kim, H.; Soto-Perez-de-Celis, E.; Chung, V.; Koczywas, M.; Fakih, M.; Chao, J.; Cabrera Chien, L.; Charles, K.; et al. Geriatric Assessment-Driven Intervention (GAIN) on Chemotherapy-Related Toxic Effects in Older Adults With Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, e214158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattersall, M.H.; Dear, R.F.; Jansen, J.; Shepherd, H.L.; Devine, R.J.; Horvath, L.G.; Boyer, M.L. Second opinions in oncology: The experiences of patients attending the Sydney Cancer Centre. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 191, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillen, M.A.; Medendorp, N.M.; Daams, J.G.; Smets, E.M.A. Patient-Driven Second Opinions in Oncology: A Systematic Review. Oncol. 2017, 22, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjong, M.C.; Menjak, I.; Trudeau, M.; Mehta, R.; Wright, F.; Leahey, A.; Ellis, J.; Gallagher, D.; Gibson, L.; Bristow, B.; et al. The Perceptions and Expectations of Older Women in the Establishment of the Senior Women’s Breast Cancer Clinic (SWBCC): A Needs Assessment Study. J. Cancer Educ. 2017, 32, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champarnaud, M.; Villars, H.; Girard, P.; Brechemier, D.; Balardy, L.; Nourhashémi, F. Effectiveness of Therapeutic Patient Education Interventions for Older Adults with Cancer: A Systematic Review. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, J.J.; Ismaila, N.; Bao, T.; Barton, D.; Ben-Arye, E.; Garland, E.L.; Greenlee, H.; Leblanc, T.; Lee, R.T.; Lopez, A.M.; et al. Integrative Medicine for Pain Management in Oncology: Society for Integrative Oncology-ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 3998–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, A.K.; Tabatabai, S.M.; Aghajanian, C.; Landgren, O.; Riely, G.J.; Sabbatini, P.; Bach, P.B.; Begg, C.B.; Lipitz-Snyderman, A.; Mailankody, S. Clinical Trial Participation Among Older Adult Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries With Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 1786–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumanlag, I.M.; Jaoude, J.A.; Rooney, M.K.; Taniguchi, C.M.; Ludmir, E.B. Exclusion of Older Adults from Cancer Clinical Trials: Review of the Literature and Future Recommendations. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 32, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).