Resources to Support Decision-Making Regarding End-of-Life Nutrition Care in Long-Term Care: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

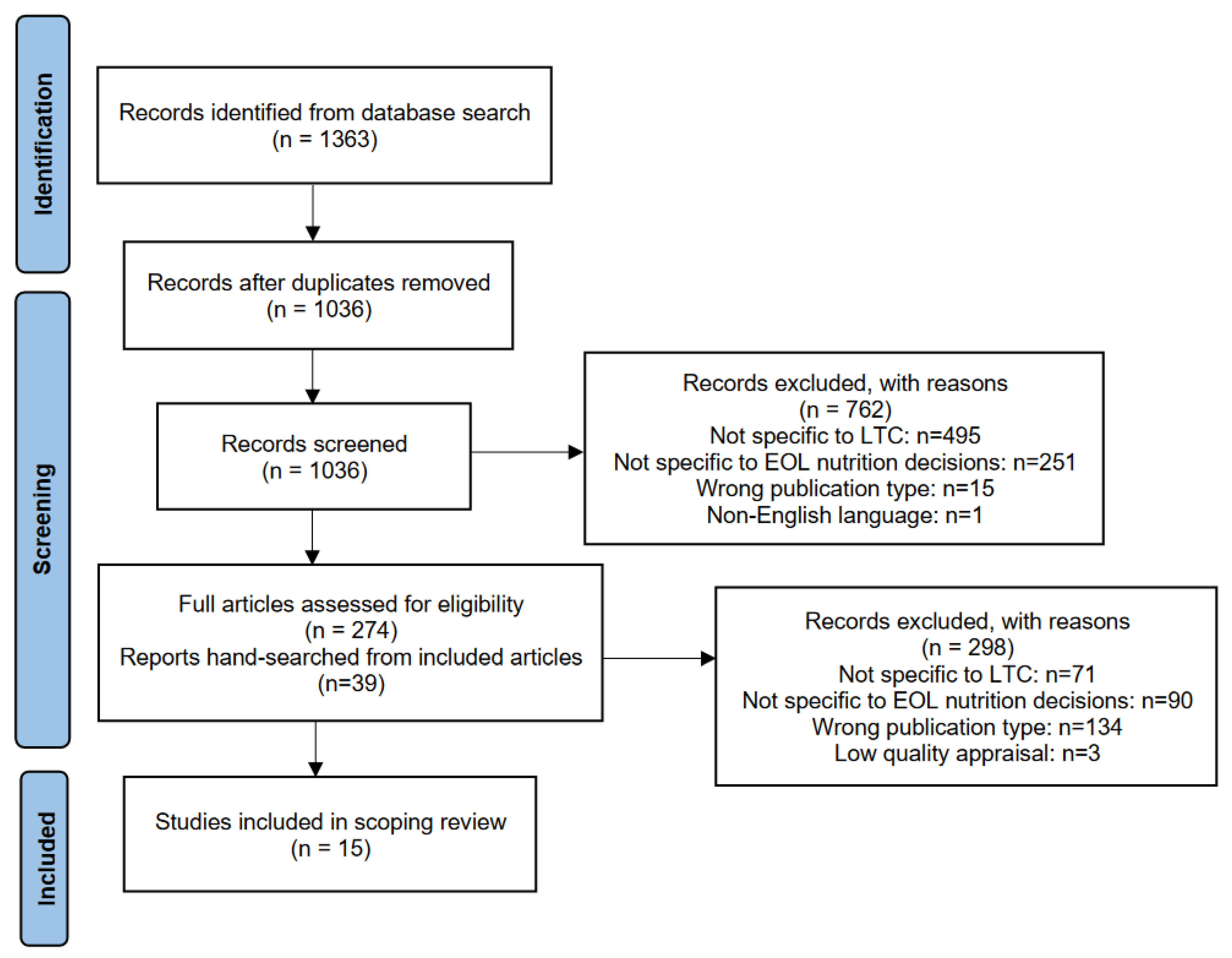

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Quality Appraisal

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Conversations about Care

3.2. Evidence-Based Decision-Making

3.3. A Need for Multidisciplinary Perspectives

3.4. Honouring Residents’ Goals of Care

3.5. Cultural Considerations for Adapting Resources

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Preedy, V. Handbook of Nutrition and Diet in Palliative Care, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- del Río, M.I.; Shand, B.; Bonati, P.; Palma, A.; Maldonado, A.; Taboada, P.; Nervi, F. Hydration and nutrition at the end of life: A systematic review of emotional impact, perceptions, and decision-making among patients, family, and health care staff. Psycho-Oncology 2011, 21, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldrop, D.P.; McGinley, J.M. Beyond Advance Directives: Addressing Communication Gaps and Caregiving Challenges at Life’s End. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022, 63, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vossius, C.; Selbæk, G.; Benth, J.; Bergh, S. Mortality in nursing home residents: A longitudinal study over three years. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. Residential Care Facilities. 2010. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/83-237-x/83-237-x2012001-eng.pdf?st=jBKM2RVH (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Barrado-Martín, Y.; Nair, P.; Anantapong, K.; Aker, N.; Moore, K.J.; Smith, C.H.; Rait, G.; Sampson, E.L.; Ma, J.M.; Davies, N. Family caregivers’ and professionals’ experiences of supporting people living with dementia’s nutrition and hydration needs towards the end of life. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, A.N. To What Extent Does Clinically Assisted Nutrition and Hydration Have a Role in the Care of Dying People? J. Palliat. Care 2020, 35, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, F.; Lau, F.; Downing, M.G.; Lesperance, M. A reliability and validity study of the Palliative Performance Scale. BMC Palliat. Care 2008, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, A.; Spathis, A.; Antunes, B.; Barclay, S. Medical communication and decision-making about assisted hydration in the last days of life: A qualitative study of doctors experienced with end of life care. Palliat. Med. 2022, 36, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Dementia in Long-Term Care. 2023. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/dementia-in-canada/dementia-care-across-the-health-system/dementia-in-long-term-care (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Ribera-Casado, J.-M. Feeding and hydration in terminal stage patients. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2015, 6, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochwald, I.H.; Yakov, G.; Radomyslsky, Z.; Danon, Y.; Nissanholtz-Gannot, R. Ethical challenges in end-stage dementia: Perspectives of professionals and family care-givers. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 1228–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, A.; Rogers, A.H.; Mitchell, S.L.; McCarthy, E.P.; Lopez, R.P. Staff and Proxy Views of Multiple Family Member Involvement in Decision Making for Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2023, 25, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie, J.; Anagnostou, D.; Sivell, S.; Van Godwin, J.; Byrne, A.; Nelson, A. Symptom management, nutrition and hydration at end-of-life: A qualitative exploration of patients’, carers’ and health professionals’ experiences and further research questions. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raijmakers, N.J.; Clark, J.B.; van Zuylen, L.; Allan, S.G.; van der Heide, A. Bereaved relatives’ perspectives of the patient’s oral intake towards the end of life: A qualitative study. Palliat. Med. 2013, 27, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, H. Hard Choices for Loving People: CRP, Feeding Tubes, Palliative Care, Comfort Measures, and the Patient with a Serious Illness, 6th ed.; Quality of Life Publishing Co.: Naples, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pengo, V.; Zurlo, A.; Voci, A.; Valentini, E.; De Zaiacomo, F.; Catarini, M.; Iasevoli, M.; Maggi, S.; Pegoraro, R.; Manzato, E.; et al. Advanced dementia: Opinions of physicians and nurses about antibiotic therapy, artificial hydration and nutrition in patients with different life expectancies. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrado-Martín, Y.; Hatter, L.; Moore, K.J.; Sampson, E.L.; Rait, G.; Manthorpe, J.; Smith, C.H.; Nair, P.; Davies, N. Nutrition and hydration for people living with dementia near the end of life: A qualitative systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 664–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, B. Evolving ethical and legal implications for feeding at the end of life. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2017, 6, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, I. Artificial nutrition and hydration in advanced dementia. Can. Fam. Physician 2015, 61, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, M.; Hattori, K. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes are placed in elderly adults in Japan with advanced dementia regardless of expectation of improvement in quality of life. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2014, 18, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokker, M.E.; Van der Heide, A.; Oldenmenger, W.H.; Van der Rijt, C.C.; Van Zuylen, L. Hydration and symptoms in the last days of life. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2021, 11, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dev, R.; Dalal, S.; Bruera, E. Is there a role for parenteral nutrition or hydration at the end of life? Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2012, 6, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druml, C.; Ballmer, P.E.; Druml, W.; Oehmichen, F.; Shenkin, A.; Singer, P.; Soeters, P.; Weimann, A.; Bischoff, S.C. ESPEN guideline on ethical aspects of artificial nutrition and hydration. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-F.; Hsu, T.-W.; Liang, C.-S.; Yeh, T.-C.; Chen, T.-Y.; Chen, N.-C.; Chu, C.-S. The Efficacy and Safety of Tube Feeding in Advanced Dementia Patients: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, N.; Barrado-Martín, Y.; Vickerstaff, V.; Rait, G.; Fukui, A.; Candy, B.; Smith, C.H.; Manthorpe, J.; Moore, K.J.; Sampson, E.L. Enteral tube feeding for people with severe dementia. Emergencias 2021, 2021, CD013503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Dev, R.; Bruera, E. The Last Days of Life: Symptom Burden and Impact on Nutrition and Hydration in Cancer Patients. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2015, 9, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somers, E.; Grey, C.; Satkoske, V. Withholding versus withdrawing treatment: Artificial nutrition and hydration as a model. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2016, 10, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrop, E.; Morgan, F.; Byrne, A.; Nelson, A. “It still haunts me whether we did the right thing”: A qualitative analysis of free text survey data on the bereavement experiences and support needs of family caregivers. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status Scale. Available online: https://ecog-acrin.org/resources/ecog-performance-status/ (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Péus, D.; Newcomb, N.; Hofer, S. Appraisal of the Karnofsky Performance Status and proposal of a simple algorithmic system for its evaluation. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2013, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palecek, E.J.; Teno, J.M.; Casarett, D.J.; Hanson, L.C.; Rhodes, R.L.; Mitchell, S.L. Comfort Feeding Only: A Proposal to Bring Clarity to Decision-Making Regarding Difficulty with Eating for Persons with Advanced Dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loofs, T.S.; Haubrick, K. End-of-Life Nutrition Considerations: Attitudes, Beliefs, and Outcomes. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2021, 38, 1028–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, B.; Berkley, A.S.; Kwak, J.; Fleischmann, K.R.; Champion, J.D.; Koltai, K.S. End-of-life decision making by family caregivers of persons with advanced dementia: A literature review of decision aids. SAGE Open Med. 2018, 6, 2050312118777517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, J.P.; Chichin, E.; Posner, L.; Kassabian, S. Vital Conversations with Family in the Nursing Home: Preparation for End-Stage Dementia Care. J. Soc. Work End Life Palliat. Care 2014, 10, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, R.J.; Llewellyn-Thomas, H.; Stacey, D.; Elwyn, G. Ten years of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration: Evolution of the core dimensions for assessing the quality of patient decision aids. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2012, 13, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, D.; Légaré, F.; Lewis, K.; Barry, M.J.; Bennett, C.L.; Eden, K.B.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Llewellyn-Thomas, H.; Lyddiatt, A.; Thomson, R.; et al. Decision Aids for People Facing Health Treatment or Screening Decisions (Review). 2017. Available online: www.cochranelibrary.com (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Graham, I.D.; Logan, J.; Bennett, C.L.; Presseau, J.; O’Connor, A.M.; Mitchell, S.L.; Tetroe, J.M.; Cranney, A.; Hebert, P.; Aaron, S.D. Physicians’ intentions and use of three patient decision aids. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’brien, K.K. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. 2010. Available online: http://www.cihr-irsc.ca (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. J. Soc. Res. Method. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CASP Checklists. 2023. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Arcand, M.; Monette, J.; Monette, M.; Sourial, N.; Fournier, L.; Gore, B.; Bergman, H. Educating Nursing Home Staff About the Progression of Dementia and the Comfort Care Option: Impact on Family Satisfaction with End-of-Life Care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2009, 10, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcand, M.; Brazil, K.; Nakanishi, M.; Nakashima, T.; Alix, M.; Desson, J.-F.; Morello, R.; Belzile, L.; Beaulieu, M.; Hertogh, C.M.; et al. Educating families about end-of-life care in advanced dementia: Acceptability of a Canadian family booklet to nurses from Canada, France, and Japan. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2013, 19, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.-Z.D.; Bourgeois, M.S. Effects of Visual Aids for End-of-Life Care on Decisional Capacity of People with Dementia. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2020, 29, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, N.; Sampson, E.L.; West, E.; DeSouza, T.; Manthorpe, J.; Moore, K.; Walters, K.; Dening, K.H.; Ward, J.; Rait, G. A decision aid to support family carers of people living with dementia towards the end-of-life: Coproduction process, outcome and reflections. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 1677–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggenberger, S.K.; Nelms, T.P. Artificial hydration and nutrition in advanced Alzheimer’s disease: Facilitating family decision-making. J. Clin. Nurs. 2004, 13, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Steen, J.T.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M.; de Graas, T.; Nakanishi, M.; Toscani, F.; Arcand, M. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of a family booklet on comfort care in dementia: Sensitive topics revised before implementation. J. Med. Ethics 2013, 39, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersek, M.; Sefcik, J.S.; Lin, F.C.; Lee, T.J.; Gilliam, R.; Hanson, L.C. Provider Staffing Effect on a Decision Aid Intervention. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2014, 23, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, L.C.; Carey, T.S.; Caprio, A.J.; Joon Lee, T.; Ersek, M.; Garrett, J.; Jackman, A.; Gilliam, R.; Wessell, K.; Mitchell, S.L.; et al. Improving Decision Making for Feeding Options in Advanced Dementia: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 2009–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizeau, A.J.; Theill, N.; Cohen, S.M.; Eicher, S.; Mitchell, S.L.; Meier, S.; McDowell, M.; Martin, M.; Riese, F. Fact Box decision support tools reduce decisional conflict about antibiotics for pneumonia and artificial hydration in advanced dementia: A randomized controlled trail. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 48, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, L.; Bertok, M.; Hartmann, J.; Fischer, J.; Rossmeier, C.; Dinkel, A.; Ortner, M.; Diehl-Schmid, J. Development and testing of an informative guide about palliative care for family caregivers of people with advanced dementia. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, E.A.; Caprio, A.J.; Wessell, K.; Lin, F.C.; Hanson, L.C. Impact of a Decision Aid on Surrogate Decision-Makers’ Perceptions of Feeding Options for Patients with Dementia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, S. Withholding or withdrawing nutrition at the end of life. Nurs. Stand. 2010, 25, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, P.M.; Rogers, J.; Strack, C. Artificial Nutrition and Hydration for the Terminally Ill A Reasoned Approach. 2008. Available online: www.homehealthcarenurseonline.com (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- van der Steen, J.T.; Arcand, M.; Toscani, F.; de Graas, T.; Finetti, S.; Beaulieu, M.; Brazil, K.; Nakanishi, M.; Nakashima, T.; Knol, D.L.; et al. A Family Booklet About Comfort Care in Advanced Dementia: Three-Country Evaluation. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2012, 13, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Steen, J.T.; Heck, S.; Juffermans, C.C.; Garvelink, M.M.; Achterberg, W.P.; Clayton, J.; Thompson, G.; Koopmans, R.T.; van der Linden, Y.M. Practitioners’ perceptions of acceptability of a question prompt list about palliative care for advance care planning with people living with dementia and their family caregivers: A mixed-methods evaluation study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcand, M.; Caron, C. Comfort Care at the End of Life for Persons with Alzheimer’s Disease or Other Degenerative Diseases of the Brain—A Guide for Caregivers; Centre d’expertise en sante de Sherbrooke: Sherbrooke, QC, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- van der Steen, J.T.; Toscani, F.; de Graas, T.; Finetti, S.; Nakanishi, M.; Nakashima, T.; Brazil, K.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M.; Arcand, M. Physicians’ and Nurses’ Perceived Usefulness and Acceptability of a Family Information Booklet about Comfort Care in Advanced Dementia. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givens, J.L.; Kiely, D.K.; Carey, K.; Mitchell, S.L. Healthcare proxies of nursing home residents with advanced dementia: Decisions they confront and their satisfaction with decision-making: Clinical investigations. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009, 57, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.L.; Tetroe, J.; O’Connor, A.M. A Decision Aid for Long-Term Tube Feeding in Cognitively Impaired Older Persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, A.; Rogers, A.H.; Hendricksen, M.; McCarthy, E.P.; Mitchell, S.L.; Lopez, R.P. Guilt as an Influencer in End-of-Life Care Decisions for Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2022, 48, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, H.; Kwak, J. End-of-life decision making for persons with dementia: Proxies’ perception of support. Dementia 2016, 17, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firnhaber, G.C.; Roberson, D.W.; Kolasa, K.M. Nursing staff participation in end-of-life nutrition and hydration decision-making in a nursing home: A qualitative study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 3059–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanesi, B.; Marchetti, A.; D’Angelo, D.; Capuzzo, M.T.; Mastroianni, C.; Artico, M.; Lusignani, M.; Piredda, M.; De Marinis, M.G. Exploring Nurses’ Involvement in Artificial Nutrition and Hydration at the End of Life: A Scoping Review. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2020, 44, 1220–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, D.; Thomas, C. Enhancing the Decision Making Process when Considering Artificial Nutrition in Advanced Dementia Care. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2019, 25, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, H.; Slaughter, S.; Gramlich, L.; Namasivayam-MacDonald, A.; Bell, J.J. Multidisciplinary Nutrition Care: Benefitting Patients with Malnutrition Across Healthcare Sectors. In Interdisciplinary Nutritional Management and Care for Older Adults: An Evidence-Based Practical Guide for Nurses; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.B.; Barrocas, A.; Wesley, J.R.; Kliger, G.; Pontes-Arruda, A.; Márquez, H.A.; James, R.L.; Monturo, C.; Lysen, L.K.; DiTucci, A. Gastrostomy Tube Placement in Patients with Advanced Dementia or Near End of Life. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2014, 29, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.L. A 93-Year-Old Man with Advanced Dementia and Eating Problems. JAMA 2007, 298, 2527–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcand, M. End-of-life issues in advanced dementia: Part 1: Goals of care, decision-making process, and family education. Can. Fam. Physician 2015, 61, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mayers, T.; Kashiwagi, S.; Mathis, B.J.; Kawabe, M.; Gallagher, J.; Aliaga, M.L.M.; Kai, I.; Tamiya, N. International review of national-level guidelines on end-of-life care with focus on the withholding and withdrawing of artificial nutrition and hydration. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2019, 19, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobak, S. Navigating Conversations Surrounding Nutrition Support at the End of Life. Support Line. 2019, Volume 41, pp. 18–23. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2225773481/3214204D71854CCEPQ/1?sourcetype=Trade%20Journals (accessed on 10 April 2024).

| End of Life | Nutrition | Decision-Making Resources | Long-Term Care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospice and palliative care nursing Palliative care Palliative medicine Palliative Terminal Dying Death | Nutr * Nutrition therapy * Patient comfort Sustenance Diet * Enteral nutrition Parenteral nutrition Dehydration Beverages Feeding behaviour Nutrition assessment Nutrition policy Comfort feeding Comfort care Compassionate terminal care Feeding behaviour Subsistence Tube feed * Hydrat * Drink Feed * Eat * | Clinical decision-making * Decision-making * | Long term care * Homes for the aged Nursing home * Hospice * Skilled nursing facilities Aged care * Senior care home Convalescent home Special care home Veteran’s home Skilled nursing facility * Health services for the aged |

| First Author, Year, Country | Type of Resource | Purpose | Target Audience for Decision Aid | Sample | Design | Goals of Study | Key Findings | Implications for EOL Nutrition Care | Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arcand, 2009 [43]; CA | An education program on comfort care and advanced dementia, supplemented with a comfort care booklet. | Pilot a palliative care education program for nurses and physicians in nursing homes. | Nursing home staff | N = 48 (bereaved family members) | Intervention | To pilot the impact of an education program on families’ satisfaction with EOL care in nursing homes. | Communication between staff and families increased post-intervention but did not reach statistical significance. | The educational program and booklet triggered more discussion between staff and families and appeared to have facilitated consensus on EOL nutrition decisions. | The small study sample may have contributed to statistical insignificance. Single site intervention. Poor uptake of the comfort care booklet among participants makes it difficult to discern the impact of the resource. |

| Arcand, 2013 [44]; CA, FR, JPN | A comfort care booklet on palliative care in dementia. | Test the acceptability of a comfort care booklet among nurses in three countries. | Nurses | N = 188 (nurses) | Survey | To test the acceptability of the booklet to nurses. | Quality ratings for each chapter of the booklet varied across countries, with consistently higher ratings in French Canada and lower ratings in Japan. Acceptability was highest in French Canada, high in English Canada, and acceptable for nurses in France and Japan. | The comfort care booklet was intended to inform families about palliative care options in dementia. Cultural adaptations likely improved the acceptability of the booklet to a limited extent in countries other than Canada. The booklet was well accepted and can support nurses in actively informing families about comfort care options. | Small, nonrepresentative sample size. Low response rate in two regions (i.e., <60% in FR and JPN.) |

| Chang, 2020 [45]; US | A six-page picture-text resource corresponding to a medical vignette about feeding tube placement for dysphagia. | Evaluate the decision-making capacity of persons living with dementia when using visual aids. | Persons with mild and moderate dementia | N = 20 (people living with mild or moderate dementia) | Experimental | To examine decisional capacity using a visual aid. | Participants had significantly better decisional capacity when supported with a visual decision aid. | Decision-making capacity can be improved for people living with dementia with the use of a visual aid in areas of understanding medical information (coughing/choking; lung infection; inadequate nutrition), evaluating and comparing treatment consequences, and relating information to one’s personal situation. | Small sample. Relied on hypothetical medical vignettes. Specific to feeding tube placement decisions, lacks other nutrition-related questions. |

| Davies, 2021 [46]; UK | An interactive booklet that highlights the progression of dementia, and several aspects of care/decision-making for resident including those around eating and drinking. | Co-produce a decision aid to support family carers of people living with dementia at the EOL. | Families | N = 33 (11 practitioners, 8 family carers, 4 people living with mild dementia) | Qualitative | To develop a process for designing a decision aid for EOL decisions in dementia through a co-production process, which would include the experiences of the resident with dementia. | Eating/drinking was one of the top four issues included in the final version of the decision aid that was developed. The paper summarizes the method used to comprehensively summarize and incorporate the data collected from each of the groups into one interactive decision aid designed for family carers. | Detailed description of the co-production process for designing decision aids to support EOL decision-making; grounded in theory, evidence, and lived experience. Can be useful to inform future interventions and the development of resources to support EOL decision-making. | Though multidisciplinary, not all roles relevant in LTC were highlighted or used in co-production. The resource was not tested; only the process for designing the booklet was documented. Cultural considerations were not addressed. |

| Eggenberger, 2004 [47]; US | Consensus building resource identifying those involved in decision-making, how the resident arrived at current condition, their prognosis with care options moving forward, and arriving at the best solution rather than focusing on fixing differences between decision makers. | Provide an ethical framework for nurses to help support families in decisions about ANH at EOL. | Nurses | N/A | Theoretical/Narrative | To provide nurses with a process of decision-making through a framework of ethical principles and evidence-based knowledge, which allows the family and nurse to come to a consensus. | Recommend nurses use a consensus-building model for supporting families in making EOL decisions. | The recommended model can aid nurses in best understanding and supporting families in making EOL ANH decisions. | Supports nurse leadership but does not include a multidisciplinary approach to consensus building. Includes theoretical discussion points to consider but lacks specific guidance on the approach or priority of evidence-based information, which can lead to an inability to reach a consensus |

| van der Steen, 2013 [48]; NL | A comfort care booklet on palliative care in dementia. | Categorize and compare revisions made to translated versions of a comfort care booklet to understand cultural and ethical sensitivities in dementia care resources. | Healthcare providers and family caregivers | N/A (data source: booklet revisions) | Qualitative Content Analysis of Implementation | To translate and adapt the originally Canadian booklet adapted for use in Italy, Japan, and the Netherlands. | Small adaptations concerned rephrasing; larger adaptations concerned additions regarding ANH in dementia. The adapted booklets for each country varied on three themes: patient-family-provider relationships, patient rights and family position, and the typology of treatments and decisions at EOL. | The respective booklets provide a cross-national perspective on palliative EOL care in dementia and particular sensitivities that are useful for shaping palliative dementia care (e.g., local legal and medical standards). | Though focused on patients/families, the local research teams responsible for translating and adapting the booklet did not include people living with dementia or families. |

| Ersek, 2014 [49]; US | A printed resource was provided to surrogate decision makers about dementia and options about feeding decisions in the intervention group. | Examine the effectiveness of a decision aid for supporting families in relation to staff levels (e.g., strained health human resources. | Surrogate decision makers | N = 256 (surrogate decision makers in 24 LTC homes) | Randomized Control Trial | To determine the effectiveness of intervention based on staffing levels. | With the use of the printed resource, families experienced reduced decisional conflict and increased conversations about EOL nutrition care in facilities with fewer staff (for example, perhaps provide a ratio of staff to residents?). | In homes with fewer staff, the resource helped to facilitate staff-family conversations about EOL nutrition care decisions. The resource can help relay important information to families in LTC homes with fewer nursing staff available to provide basic education or fundamentals about illness trajectory. | A multidisciplinary approach is not mentioned, which could assist with lower staffing levels of nurse practitioners and physician assistants. |

| Hanson, 2011 [50]; US | An audio or printed resource outlining feeding options in advanced dementia, including educational information and considerations for each. | Test whether a decision aid improves the quality of decision-making for feeding options for surrogate decision makers for nursing home residents living with advanced dementia. | Surrogate decision makers | N = 256 (resident-surrogate decision maker dyads from 24 LTC homes) | RCT | To determine if a decision aid would facilitate decision-making and reduce decisional conflict. | Surrogate decision makers had increased knowledge, lower decisional conflict, and more frequent conversations with providers, ultimately resulting in an increased trend of dysphagia diets, oral assistance feeding, and staff assistance. | With the use of a decision aid, there is likely to be more discussion around the clinical course/care of the resident and higher quality decision-making. | Population sample not representative (e.g., over half European descent and Protestant). Multidisciplinary approach noted? |

| Loizeau, 2019 [51]; CH | A printed resource on AH that describes administration, benefits, harms, and alternatives; used to help inform decision makers about AH using evidence-based information. | Apply fact boxes as decision support tools to hypothetical scenarios to determine if fact boxes impact comfort with decision-making, knowledge, or preferences for AH in advanced dementia. | Physicians, families | N= 232 (64 physicians, 100 family members of residents living with dementia, and 68 surrogate decision makers) | RCT | Brief, convenient tools for decision-making for a wide variety of target audiences. | Decisional conflict was significantly lower in the fact box intervention at one-month follow-up; knowledge scores were significantly higher. Fact box intervention did not significantly impact decisions to forgo AH. | Fact boxes can be used as both a communication tool and to aid in decision-making. The resources were versatile, making them accessible in any setting, and they are brief reference guides that can be applicable to HCPs or families. | Relied on hypothetical scenarios. Focuses on AH, not AN. Fact boxes were the same for physicians and families; family carers required a relatively high educational background to understand the information. |

| Riedl, 2020 [52]; GER | An information booklet provided to caregivers regarding general palliative care. | Develop an informative booklet for caregivers of people with advanced dementia on palliative care issues and to investigate family caregiver knowledge and involvement in decisions before and after studying the booklet. | Family caregivers | N = 38 (patient-caregiver dyads) | RCT | To measure the knowledge gain and increase in conversations/involvement regarding medical care and the decisions of family caregivers who received the information booklet. | Caregivers gained knowledge on 6 palliative care topics, including life prolonging measures (e.g., tube feeding). 80% were more involved in decision-making regarding life prolonging measures, including tube feeding. Caregivers lacked knowledge about palliative care and available services (including EOL nutrition, comfort feeding) before reviewing the booklet. | Use of the resource increased caregiver knowledge of palliative care issues, including tube feeding, and increased their participation in decision-making on topics including life prolonging measures (e.g., tube feeding). The study notes that the booklets cannot simply be translated; considerations of legal and cultural aspects, country-specific standards, and practice when adapting guidance on palliative care are recommended. | Dementia specific. The booklet covers a lot of content and therefore might be long/tedious to read. The resource includes sections on tube feeding and thirst and hunger at EOL, but not general eating/drinking at EOL. The research team noted a lack of registered dietitian involvement in development. |

| Snyder, 2013 [53]; US | A printed resource that provides information regarding eating/drinking interventions in EOL. | Test whether a resource reduces decisional conflict or increases knowledge about feeding options among surrogate decision makers. | Surrogate decision makers | N = 255 (surrogate decision makers in 24 nursing homes) | RCT | To determine if the resource impacted surrogate decision maker knowledge, decisional conflict, and expectations of tube feeding. | Surrogate decision makers had more knowledge and expected fewer benefits from tube feeding following the use of the resource. | This resource can help in educating and addressing myths surrounding the expectations and benefits of tube feeding for those living with EOL dementia. | Most participants were of similar cultural and religious backgrounds. |

| Holmes, 2010 [54]; UK | A resource that poses ethical questions to consider and helps guide when deciding if AN is in the best interest of the patient. | Overview/script of ethical questions to guide HCPs in supporting EOL ANH decision-making. | Healthcare Providers | N/A | Clinical narrative | To describe the ethical principles providers must consider through a framework of guidance questions when determining the course of nutrition treatment for a patient. | Presents ethical questions for HCPs to consider with patients/families before commencing AN. | Provides a series of questions that can be used to guide HCPs to support ethical decision-making about AN. | Ethical framework questions are framed only in the specific context of ANH. Culture is not referenced in the framework. Fails to mention multidisciplinary perspectives/participation. |

| Suter, 2008 [55]; US | A framework for HCPs to guide discussions with patients and families about ANH at EOL to address misconceptions about ANH. | Present a review of evidence on the physiological effects of ANH and a framework for discussion about ANH with patients and families. | Healthcare Providers | N/A | Clinical Narrative | To provide evidence-based advantages and disadvantages to ANH, a framework for discussion, and other supportive resources. | Provides a framework for guiding staff-family discussions about ANH. Summarizes a list of credible resources nurses can use to engage families in meaningful discussions about preferences for ANH. | Resources to assist families with advance directives and for engaging families in discussions about ANH. A 6-step framework can help nurses address common misperceptions about ANH and help families cope with feelings of helplessness. The resources emphasize collaboration and education. | The framework of questions does not direct families to multidisciplinary consultations, such as a dysphagia diet with assistance from an RD. URLs for listed resources are unavailable; a lack of a clear layout for framework questions and a printed guideline may deter nurses from using the recommendations. |

| van der Steen, 2012 [56]; NL | A comfort care booklet on palliative care in dementia. | Evaluate the content, usefulness, and acceptability of a comfort care booklet among families in three countries. | Families | N = 138 (bereaved family members of LTC residents) | Retrospective Cohort | To evaluate the content, format, usefulness, acceptability, and preferred way of obtaining the booklet. | The contents and format of the booklet were generally endorsed, with higher ratings among Canadian and Dutch families than Italian families. The need for and perceived usefulness of the booklet were almost universally positive. | The booklet is suitable for Canadian and Dutch families but requires additional cultural adaptations for use in Italy. | The retrospective study design may have introduced bias (e.g., receptiveness to information when a family’s loved one was still alive). Small, nonrepresentative sample. |

| van der Steen, 2021 [57]; NL | A question prompt list about palliative and EOL care in dementia. | Evaluate HCP perceptions of the acceptability and usefulness of a question prompt list for palliative care in dementia. | Healthcare providers | N = 66 (practitioners) | Mixed methods evaluation | To evaluate the acceptability and usefulness of a question prompt list for helping HCPs provide palliative EOL care for patients with dementia. | Most practitioners found the question prompt list acceptable; the contents were appreciated, with some concern about information overload. | A question prompt list can be a valuable tool for facilitating staff-family conversations about EOL care. | The question prompt list was not assessed by people living with dementia or their families. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alford, H.; Anvari, N.; Lengyel, C.; Wickson-Griffiths, A.; Hunter, P.; Yakiwchuk, E.; Cammer, A. Resources to Support Decision-Making Regarding End-of-Life Nutrition Care in Long-Term Care: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16081163

Alford H, Anvari N, Lengyel C, Wickson-Griffiths A, Hunter P, Yakiwchuk E, Cammer A. Resources to Support Decision-Making Regarding End-of-Life Nutrition Care in Long-Term Care: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2024; 16(8):1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16081163

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlford, Heather, Nadia Anvari, Christina Lengyel, Abigail Wickson-Griffiths, Paulette Hunter, Erin Yakiwchuk, and Allison Cammer. 2024. "Resources to Support Decision-Making Regarding End-of-Life Nutrition Care in Long-Term Care: A Scoping Review" Nutrients 16, no. 8: 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16081163

APA StyleAlford, H., Anvari, N., Lengyel, C., Wickson-Griffiths, A., Hunter, P., Yakiwchuk, E., & Cammer, A. (2024). Resources to Support Decision-Making Regarding End-of-Life Nutrition Care in Long-Term Care: A Scoping Review. Nutrients, 16(8), 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16081163