Efficacy of Spice Supplementation in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

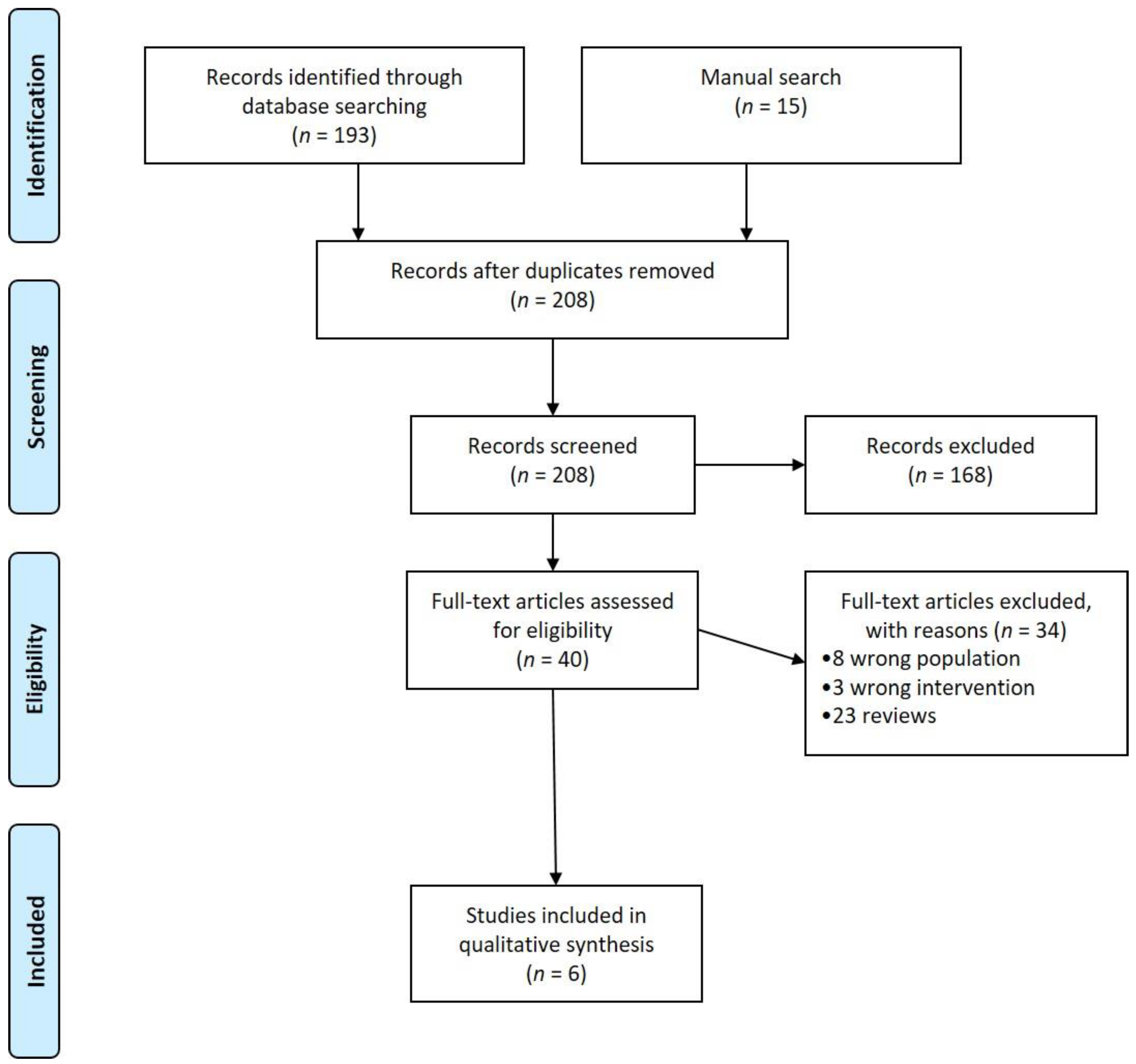

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias within Studies

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

3.4.1. Garlic Supplementation in Rheumatoid Arthritis

3.4.2. Curcumin Supplementation in Rheumatoid Arthritis

3.4.3. Ginger Supplementation in Rheumatoid Arthritis

3.4.4. Cinnamon Supplementation in Rheumatoid Arthritis

3.4.5. Saffron Supplementation in Rheumatoid Arthritis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vázquez-Fresno, R.; Rosana, A.R.R.; Sajed, T.; Onookome-Okome, T.; Wishart, N.A.; Wishart, D.S. Herbs and Spices-Biomarkers of Intake Based on Human Intervention Studies–A Systematic Review. Genes Nutr. 2019, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.A. Health Benefits of Culinary Herbs and Spices. J. AOAC Int. 2019, 102, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sureda, A.; Devkota, H.P.; Pittalà, V.; Barreca, D.; Silva, A.S.; Tewari, D.; Xu, S.; Nabavi, S.M. Curcumin, the golden spice in treating cardiovascular diseases. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 38, 107343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.H.; Blunden, G.; Tanira, M.O.; Nemmar, A. Some phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): A review of recent research. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Nakanishi, E.; Kuwata, H.; Chen, J.; Nakasone, Y.; He, X.; He, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, B.; et al. Inhibitory effects and molecular mechanisms of garlic organosulfur compounds on the production of inflammatory mediators. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 2049–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, B.B.; Shishodia, S. Molecular targets of dietary agents for prevention and therapy of cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 71, 1397–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, H.; Younesi, H.M. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of Crocus sativus L. stigma and petal extracts in mice. BMC Pharmacol. 2002, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available online: /cochrane-handbook-systematic-reviews-interventions (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Appendix: Jadad Scale for Reporting Randomized Controlled Trials. In Evidence-based Obstetric Anesthesia; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 237–238. ISBN 978-0-470-98834-3.

- Moosavian, S.P.; Paknahad, Z.; Habibagahi, Z. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, evaluating the garlic supplement effects on some serum biomarkers of oxidative stress, and quality of life in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2020, 74, e13498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavian, S.P.; Paknahad, Z.; Habibagahi, Z.; Maracy, M. The effects of garlic (Allium sativum) supplementation on inflammatory biomarkers, fatigue, and clinical symptoms in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phytother. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, B.; Goel, A. A randomized, pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of curcumin in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Phytother. Res. 2012, 26, 1719–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalraj, A.; Varma, K.; Jacob, J.; Divya, C.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Stohs, S.J.; Gopi, S. A Novel Highly Bioavailable Curcumin Formulation Improves Symptoms and Diagnostic Indicators in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Two-Dose, Three-Arm, and Parallel-Group Study. J. Med. Food 2017, 20, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryaeian, N.; Mahmoudi, M.; Shahram, F.; Poursani, S.; Jamshidi, F.; Tavakoli, H. The effect of ginger supplementation on IL2, TNFα, and IL1β cytokines gene expression levels in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran. 2019, 33, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryaeian, N.; Shahram, F.; Mahmoudi, M.; Tavakoli, H.; Yousefi, B.; Arablou, T.; Jafari Karegar, S. The effect of ginger supplementation on some immunity and inflammation intermediate genes expression in patients with active Rheumatoid Arthritis. Genes 2019, 698, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishehbor, F.; Rezaeyan Safar, M.; Rajaei, E.; Haghighizadeh, M.H. Cinnamon Consumption Improves Clinical Symptoms and Inflammatory Markers in Women with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2018, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamidi, Z.; Aryaeian, N.; Abolghasemi, J.; Shirani, F.; Hadidi, M.; Fallah, S.; Moradi, N. The effect of saffron supplement on clinical outcomes and metabolic profiles in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daily, J.W.; Yang, M.; Park, S. Efficacy of Turmeric Extracts and Curcumin for Alleviating the Symptoms of Joint Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. J. Med. Food 2016, 19, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fu, E.; Tsai, M.-C.; Chin, Y.-T.; Tu, H.-P.; Fu, M.M.; Chiang, C.-Y.; Chiu, H.-C. The effects of diallyl sulfide upon Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide stimulated proinflammatory cytokine expressions and nuclear factor-kappa B activation in human gingival fibroblasts. J. Periodontal Res. 2015, 50, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perricone, C.; Ceccarelli, F.; Saccucci, M.; Di Carlo, G.; Bogdanos, D.P.; Lucchetti, R.; Pilloni, A.; Valesini, G.; Polimeni, A.; Conti, F. Porphyromonas gingivalis and rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2019, 31, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Jung, Y.R.; An, H.J.; Dae, H.K.; Eun, J.J.; Yeon, J.C.; Kyoung, M.M.; Min, H.P.; Park, C.H.; Chung, K.W.; et al. Anti-wrinkle and anti-inflammatory effects of active garlic components and the inhibition of MMPs via NF-κB signaling. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luettig, J.; Rosenthal, R.; Lee, I.-F.M.; Krug, S.M.; Schulzke, J.D. The ginger component 6-shogaol prevents TNF-α-induced barrier loss via inhibition of PI3K/Akt and NF-κB signaling. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 2576–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoda, H.; Shan, S.-J.; Tanaka, J.; Seki, A.; Seo, J.-W.; Kasajima, N.; Tamura, S.; Ke, Y.; Murakami, N. Anti-inflammatory properties of red ginger (Zingiber officinale var. Rubra) extract and suppression of nitric oxide production by its constituents. J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.N.; Srivastava, K.C.; Gan, E.K. Suppressive effects of eugenol and ginger oil on arthritic rats. Pharmacology 1994, 49, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.M.; Seo, J.H.; Ryu, S.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Min, K.R.; Kim, Y. Cinnamaldehyde and 2-methoxycinnamaldehyde as NF-kappaB inhibitors from Cinnamomum cassia. Planta Med. 2004, 70, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Sethi, G.; Ahn, K.S.; Pandey, M.K.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Sung, B.; Aggarwal, A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Natural products as a gold mine for arthritis treatment. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2007, 7, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.-C.; Deng, J.-S.; Chiu, C.-S.; Hou, W.-C.; Huang, S.-S.; Shie, P.-H.; Huang, G.-J. Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Cinnamomum cassia Constituents In Vitro and In Vivo. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med. 2012, 429320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hurley, M.N.; Smith, S.; Forrester, D.L.; Alan, R.S. Antibiotic adjuvant therapy for pulmonary infection in cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 7, CD008037. [Google Scholar]

- Ayati, Z.; Yang, G.; Ayati, M.H.; Emami, S.A.; Chang, D. Saffron for mild cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajimonfarednejad, M.; Mohadeseh, O.M.; Raee, M.J.; Mohammad, H.H.; Johannes, G.M.; Mojtaba, H. Cinnamon: A systematic review of adverse events. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, N.H.; Kim, S.J.; Long, N.P.; Jung, E.M.; Young, C.Y.; Eun, G.L.; Mina, K.; Tae, J.K.; Yang, Y.Y.; Son, E.Y.; et al. Ginger on Human Health: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of 109 Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daien, C.; Hua, C.; Gaujoux-Viala, C.; Cantagrel, A.; Madeleine, D.; Maxime, D.; Bruno, F.; Xavier, M.; Nayral, N.; Richez, C.; et al. Update of French society for rheumatology recommendations for managing rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine 2019, 86, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewé, R.B.M.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; Gerd, R.B.; Maxime, D.; Andreas, K.; Iain, B.M.; Alexandre, S.; Van Vollenhoven, R.F.; De Wit, M.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Study | Country | Inclusion Criteria | Intervention | Controls | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | Disease Duration (Years) | RF+ | ACPA+ | Age (Years) | Disease Duration (Years) | RF+ | ACPA+ | |||

| Moosavian, 2020 [9,10] | Iran | ACR/EULAR criteria, DAS-28 ESR > 3.2, treated with csDMARDs, not receiving NSAIDs, or bDMARDs | G: 51.22 ± 12.61 | G: 6.60 ± 7.43 | NR | NR | 51.37 ± 11.04 | 6.68 ± 8.20 | NR | NR |

| Chandran, 2012 [11] | India | ACR 1987, DAS-28 ESR > 5.1, not receiving NSAIDs, csDMARDs, or bDMARDs | C: 7.8 ± 8.60 C + D: 47 ± 16.22 | NR | NR | NR | 48.87 ± 10.78 | NR | NR | NR |

| Amalraj, 2017 [12] | India | ACR/EULAR criteria, DAS-28 ESR > 5.1, CRP > 0.6 mg/dL or ESR > 28 mm/h, not receiving NSAIDs, csDMARDs, or bDMARDs | C 250 mg 36.7 ± 10.7 C 500 mg 38.3 ± 5.8 | NR | NR | NR | 39.6 ± 8.8 | NR | NR | NR |

| Aryaeian, 2019 [13,14] | Iran | ACR/EULAR criteria, 2 year disease duration, treated with methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, and prednisolone < 10 mg/day | Gi: 48.63 ± 2.38 | Gi: 18.12 ± 4.13 | NR | NR | 46.67 ± 1.94 | 14.87 ± 4.13 | NR | NR |

| Shishehbor, 2018 [15] | Iran | ACR/EULAR criteria, for at least 2 years, having active disease, treated with csDMARDs, not receiving NSAIDs or bDMARDs | Ci: 44.66 ± 11.22 | 6.27 ± 3.04 | NR | NR | 49.11 ± 7.45 | 5.00 ± 2.22 | NR | NR |

| Hamidi, 2020 [16] | Iran | ACR/EULAR criteria, for at least 2 years, having active disease | S: 51.55 ± 8.26 | S: 10.74 ± 5.66 | NR | NR | 51.80 ± 9.62 | 9.60 ± 5.13 | NR | NR |

| Intervention | Controls | Outcome | Outcome Measurement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spice | Study | Design | Population | Type | N | Type | N | ||

| Garlic | Moosavian, 2020 [11,12] | Double-blind RCT | 70 | 1000 mg garlic powder tablets | 35 | Placebo | 35 | DAS-28 ESR, SJC, TJC, VAS Pain, HAQ score, CRP, ESR | 8 weeks |

| equivalent to 2.5 g of fresh garlic | |||||||||

| Curcumin | Chandran, 2012 [13] | Single-blind RCT | 45 in 3 groups | Curcumin 500 mg twice a day and diclofenac 50 mg twice a day | 15 | Diclofenac 50 mg × 2/day | 15 | DAS-28 ESR, SJC, TJC, VAS pain, VAS activity, HAQ score, CRP, ESR | 8 weeks |

| Curcumin 500 mg twice a day | 15 | ||||||||

| Curcumin | Amalraj, 2017 [14] | Double-blind RCT | 36 in 3 groups | Curcumin 250 mg twice a day | 12 | Placebo | 12 | ACR-20, DAS-28, SJC, TJC, VAS pain, CRP, ESR | 12 weeks |

| Curcumin 500 mg twice a day | 12 | ||||||||

| Ginger | Aryaeian, 2019 [15,16] | Double-blind RCT | 63 | Ginger powder 750 mg twice a day | 33 | Placebo | 30 | DAS-28 ESR, CRP | 12 weeks |

| Cinnamon | Shishehbor, 2018 [17] | Double-blind RCT | 36 | Cinnamon 1 g twice a day | 18 | Placebo | 18 | DAS-28, SJC, TJC, VAS pain, ESR, CRP | 8 weeks |

| Saffron | Hamidi, 2020 [18] | Double-blind RCT | 66 | Saffron 100 mg per day | 33 | Placebo | 33 | DAS-28 ESR, SJC, TJC, VAS pain, morning stiffness, CRP, ESR | 12 weeks |

| Study | Outcome | Intervention | Controls | Between-Group Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline versus End of Treatment | Baseline versus End of Treatment | |||

| p-Value | ||||

| Moosavian et al. [11,12] | DAS-28 ESR | G: 4.61 ± 0.92 vs. 3.80 ± 0.81 * | 4.52 ± 0.78 vs. 4.45 ± 0.86 | <0.001 |

| SJC | G: 1.92 ± 1.62 vs. 1.19 ± 1.40 * | 1.74 ± 2.17 vs. 1.71 ± 2.34 | 0.117 | |

| TJC | G: 6.74 ± 4.55 vs. 3.61 ± 4.04 * | 5.57 ± 3.97 vs. 5.55 ± 4.5 | <0.001 | |

| VAS Pain (mm) | G: 68.46 ± 14.80 vs. 59.35 ± 13.30 * | 70.54 ± 16.66 vs. 69.19 ± 18.40 | <0.001 | |

| HAQ score | G: NR | NR | 0.23 | |

| CRP (mg/L) | G: 13.44 ± 13.76 vs. 8.62 ± 10.58 * | 13.57 ± 14.04 vs. 14.23 ± 16.22 | 0.018 | |

| ESR (mm/h) | G: 23.63 ± 13.82 vs. 19.03 ± 12.94 | 20.10 ± 11.74 vs. 20.74 ± 13.26 | 0.134 | |

| Chandran et al. [6] | DAS-28 ESR | C + D: 6.44 ± 0.51 vs. 3.58 ± 0.71 * | 6.72 ± 0.87 vs. 3.89 ± 1.43 * | NR |

| C: 6.40 ± 0.73 vs. 3.55 ± 0.73 * | NR | |||

| SJC | C + D: 11.5 vs. 0.42 * | 16.6 vs. 1.83 * | NR | |

| C: 12.15 vs. 0.36 * | NR | |||

| TJC | C + D: 16.67 vs. 2.75 * | 18.2 vs. 5.67 * | NR | |

| C: 18.64 vs. 3.14 * | NR | |||

| VAS Pain (mm) | C + D: 77.25 ± 9.65 vs. 34.29 ± 26.75 * | 78.25 ± 11.25 vs. 39.17 ± 20.1 * | NR | |

| C: 68.57 ± 17.14 vs. 27.5 ± 9.35 * | NR | |||

| VAS Activity (mm) | C + D: 78.75 40.83 * | 77.5 vs. 42.08 * | NR | |

| C: 83.93 vs. 30.7 * | NR | |||

| HAQ score | C + D: 3.95 vs. 1.53 * | 3.79 vs. 1.51 * | NR | |

| C: 4.41 vs. 1.0 * | NR | |||

| CRP (mg/L) | C + D: 9.11 ± 9.93 vs. 6.66 ± 6.87 * | 3.3 ± 2.4 vs. 3.35 ± 2.5 | NR | |

| C: 5.34 ± 4.12 vs. 2.56 ± 1.8 | NR | |||

| ESR (mm/h) | C + D: 28.75 ± 20.09 vs. 24.92 ± 22.6 | 27.08 ± 17.1 vs. 24.75 ± 13.5 | NR | |

| C: 28 ± 23.7 vs. 24.86 ± 17.7 | NR | |||

| Amalraj et al. [7] | DAS-28 | C 250 mg: 4.51 ± 0.64 vs. 2.14 ± 0.16 * | 3.53 ± 0.47 vs. 3.53 ± 0.47 | NR |

| C 500 mg: 5.29 ± 0.54 vs. 1.80 ± 0.36 * | NR | |||

| ACR-20 | C 250 mg: 19.33 ± 2.81 vs. 65.17 ± 10.67 * | 14.75 ± 6.58 vs. 14.75 ± 6.58 * | NR | |

| C 500 mg: 16.50 ± 3.78 vs. 67.83 ± 8.60 * | NR | |||

| SJC | C 250 mg: 14.42 ± 1.68 vs. 2.83 ± 0.83 * | 11.08 ± 2.23 vs. 10.67 ± 1.97 | NR | |

| C 500 mg: 17.00 ± 1.35 vs. 2.58 ± 0.67 * | NR | |||

| TJC | C 250 mg: 13.33 ± 3.17 vs. 2.92 ± 0.67 * | 9.50 ± 3.23 vs. 9.92 ± 1.93 | NR | |

| C 500 mg: 16.67 ± 1.92 vs. 2.00 ± 0.74 * | NR | |||

| VAS pain (cm) | C 250 mg: 7.01 ± 0.86 vs. 2.63 ± 0.74 * | 6.61 ± 0.73 vs. 6.84 ± 0.63 | NR | |

| C 500 mg: 7.99 ± 0.71 vs. 2.21 ± 0.45 * | NR | |||

| CRP (mg/dL) | C 250 mg: 0.97 ± 0.15 vs. 0.68 ± 0.10 * | 0.97 ± 0.15 vs. 1.08 ± 0.15 | NR | |

| C 500 mg: 1.21 ± 0.18 vs. 0.59 ± 0.08 * | NR | |||

| ESR (mm/h) | C 250 mg: 175.9 ± 12.9 vs. 21.0 ± 4.8 * | 180.2 ± 12.4 vs. 126.9 ± 17.3 | NR | |

| C 500 mg: 181.7 ± 4.8 vs. 21.2 ± 2.9 * | NR | |||

| Aryaeian et al. [8,9] | DAS-28-ESR | Gi: 4.73 ± 0.27 vs. 3.44 ± 0.30 * | 4.51 ± 0.27 vs. 4.30 ± 0.33 | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | Gi: 13.50 ± 3.45 vs. 7.62 ± 5.1 * | 13.01 ± 2.25 vs. 16.39 ± 9.6 | 0.044 | |

| Shishehbor et al. [10] | DAS-28 | Ci: 6.04 ± 0.52 vs. 3.92 ± 0.52 * | 5.35 ± 0.76 vs. 5.64 ± 0.66 | <0.001 |

| SJC | Ci: 8.44 ± 2.33 vs. 1.38 ± 0.97 * | 7.16 ± 2.23 vs. 7.66 ± 2.08 | <0.0001 | |

| TJC | Ci: 11.44 ± 2.52 vs. 2.77 ± 1.47 * | 10.05 ± 2.66 vs. 10.05 ± 3.09 | <0.001 | |

| VAS pain (cm) | Ci: 68.88 ± 14.30 vs. 43.88 ± 12.89 * | 54.72 ± 16.58 vs. 58.05 ± 18.24 | <0.001 | |

| CRP (mg/L) | Ci: 35.33 ± 10.08 vs. 24.61 ± 10.29 * | 27 ± 12.92 vs. 32.50 ± 13.15 * | <0.001 | |

| ESR (mm/h) | Ci: 32.88 ± 13.31 vs. 23.66 ± 12.98 * | 25.16 ± 17.44 vs. 27.83 ± 17.74 | 0.42 | |

| Hamidi et al. [11] | DAS-28 ESR | S: 5.09 ± 1.10 vs. 4.33 ± 0.94 * | 4.92 ± 1.09 vs. 5.19 ± 0.65 | <0.001 |

| SJC | S: 6.26 ± 3.63 vs. 4.13 ± 2.47 * | 7.07 ± 3.83 vs. 7.70 ± 2.54 | ≤0.001 | |

| TJC | S: 5.23 ± 3.27 vs. 3.84 ± 2.70 * | 4.53 ± 2.86 vs. 4.63 ± 2.73 | 0.259 | |

| VAS pain (mm) | S: 60.97 ± 21.19 vs. 42.58 ± 15.69 * | 52.33 ± 22.99 vs. 50.00 ± 21.81 * | ≤0.001 | |

| Morning stiffness: 1–3 h | S: 10 (32.30%) vs. 6 (19.40%) | 5 (16.70%) vs. 6 (20.00%) | 0.975 | |

| CRP (mg/L) | S: 12.00 ± 7.40 vs. 8.82 ± 7.93 * | 12.00 ± 12.84 vs. 14.56 ± 21.03 | 0.200 | |

| ESR (mm/h) | S: 29.94 ± 17.40 vs. 24.06 ± 12.66 * | 30.20 ± 28.19 vs. 32.00 ± 14.75 | 0.028 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Letarouilly, J.-G.; Sanchez, P.; Nguyen, Y.; Sigaux, J.; Czernichow, S.; Flipo, R.-M.; Sellam, J.; Daïen, C. Efficacy of Spice Supplementation in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Literature Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123800

Letarouilly J-G, Sanchez P, Nguyen Y, Sigaux J, Czernichow S, Flipo R-M, Sellam J, Daïen C. Efficacy of Spice Supplementation in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Literature Review. Nutrients. 2020; 12(12):3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123800

Chicago/Turabian StyleLetarouilly, Jean-Guillaume, Pauline Sanchez, Yann Nguyen, Johanna Sigaux, Sébastien Czernichow, René-Marc Flipo, Jérémie Sellam, and Claire Daïen. 2020. "Efficacy of Spice Supplementation in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Literature Review" Nutrients 12, no. 12: 3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123800

APA StyleLetarouilly, J.-G., Sanchez, P., Nguyen, Y., Sigaux, J., Czernichow, S., Flipo, R.-M., Sellam, J., & Daïen, C. (2020). Efficacy of Spice Supplementation in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Literature Review. Nutrients, 12(12), 3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123800