From MSG-SEVIRI to MTG-FCI: Advancing Volcanic Thermal Monitoring from Geostationary Satellites

Highlights

- The MTG-FCI sensor provides enhanced spatial, spectral, and temporal resolution compared to MSG-SEVIRI, enabling more continuous and detailed observation of volcanic activity.

- The RSDF algorithm was adapted to FCI data and successfully applied to Mount Etna’s 2025 eruptions, allowing accurate retrieval of volcanic radiative parameters.

- The combination of FCI and polar-orbiting satellite data ensures consistent quantitative estimates of volcanic radiance and thermal anomalies.

- The improved performance of MTG-FCI enhances the capability for near-real-time monitoring of active volcanoes from geostationary orbit.

- These results contribute to the development of advanced operational systems for volcanic hazard detection and early-warning applications based on next-generation satellite missions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Etna 2025 Activity

- February–March (Red): 10, 12, 17, 20, and 22 February 2025.

- March–June (Yellow): 8, 15, and 26 April; 13 May; and 2 and 20 June 2025

- August–September (Green): 16, 23, 24, 29, and 31 August 2025.

3. Satellite Data Sources

3.1. Flexible Combined Imager (FCI)

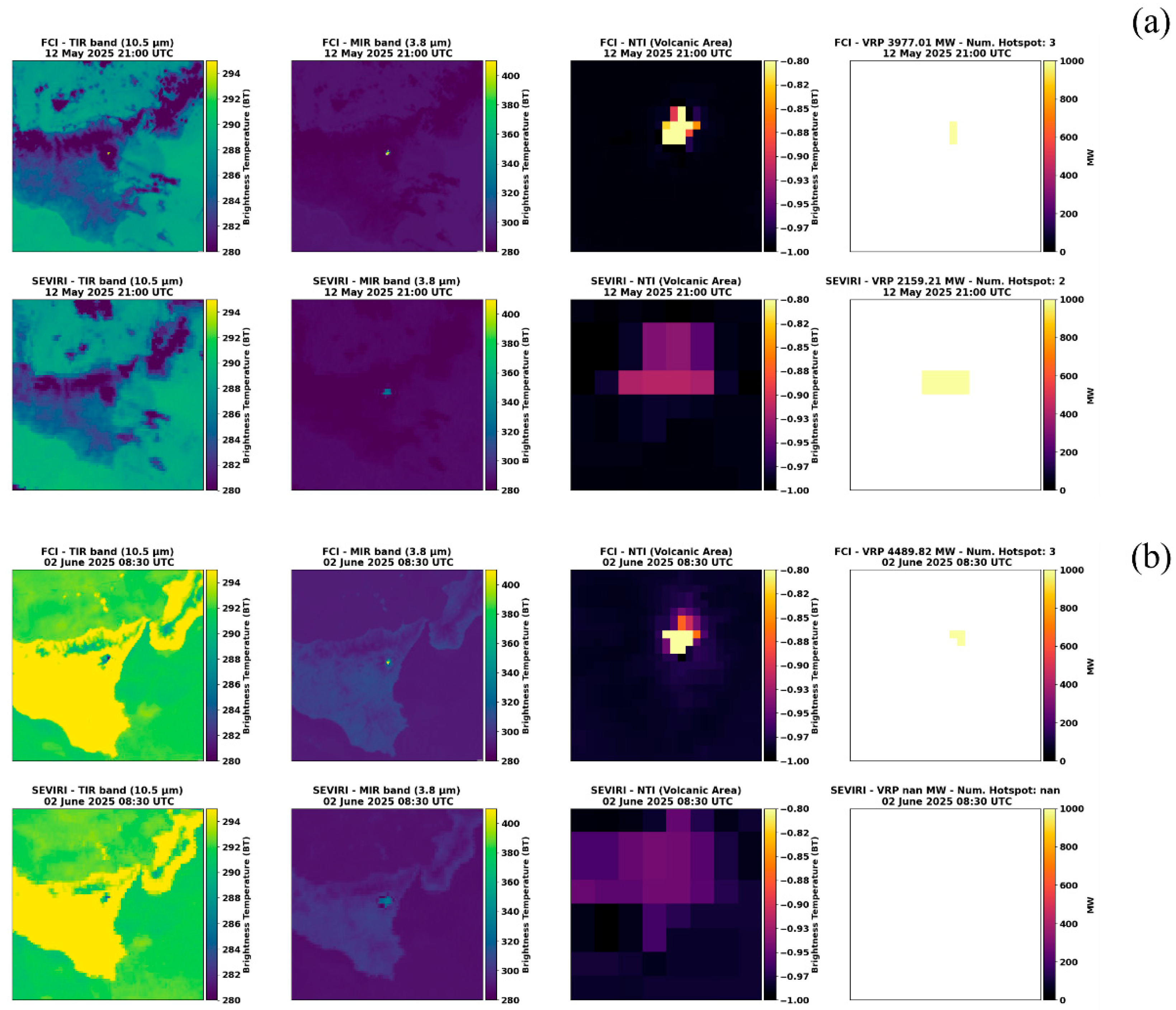

3.2. Comparison Between FCI and SEVIRI

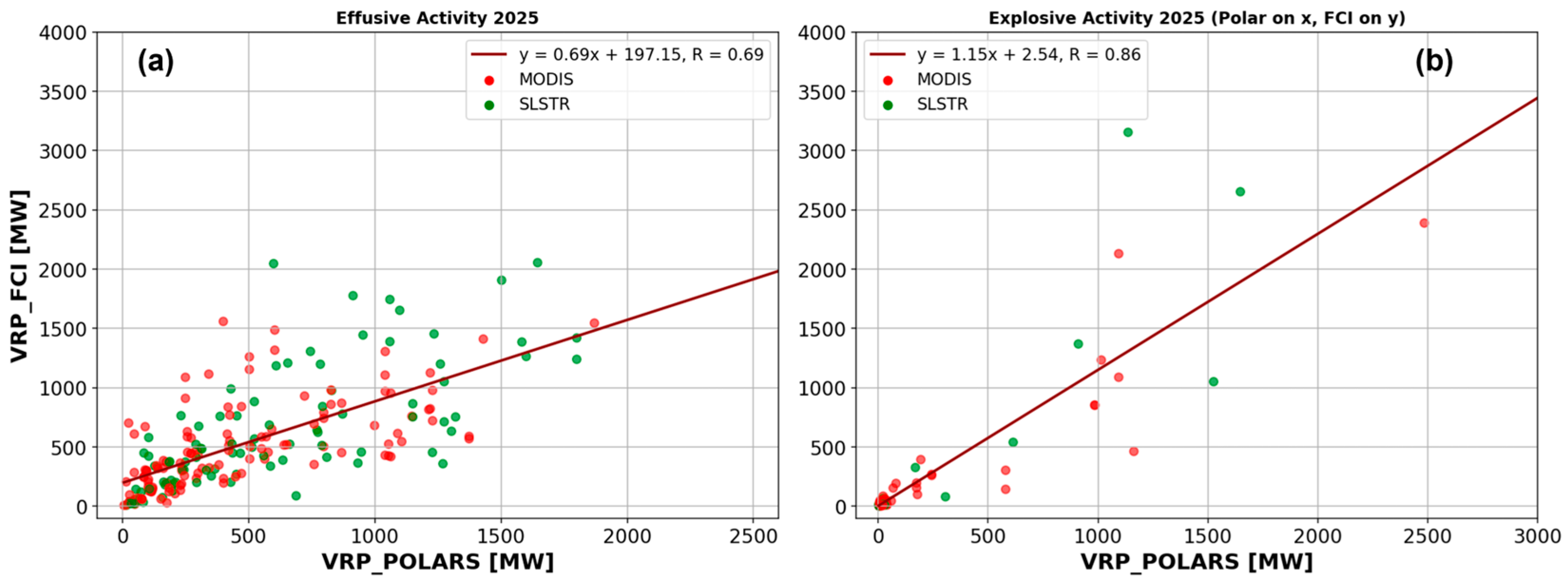

3.3. Comparison Between FCI and Polar Satellite Sensors

4. Methods

- Mask1 flags pixels in the volcanic area (VA) with SSD values exceeding the maximum SSD of the non-volcanic area (NVA):

- Mask2 is applied to differentiate and identify the “true hotspots” among the potential ones:

4.1. Adaptation of RSDF to FCI

4.2. Time Average Discharge Rate (TADR) and Volume Calculation

5. Results

5.1. Effusive Activity (February–March 2025)

5.2. Explosive Activity (March–June 2025)

5.3. Effusive Activity (August–September 2025)

6. Discussions

- The thermal and spatial features of the monitored event (e.g., portions of lava at different temperatures, from cooling to incandescent lava flow portions);

- The technical characteristics of the sensors, including saturation temperatures for each channel, spatial resolution, available spectral bands, and noise equivalent temperature difference (NetD) [82].

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blackett, M. An Overview of Infrared Remote Sensing of Volcanic Activity. J. Imaging 2017, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carn, S.A.; Clarisse, L.; Prata, A.J. Multi-Decadal Satellite Measurements of Global Volcanic Degassing. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2016, 311, 99–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, M.P.; Lopez, T.; Wright, R.; Pavolonis, M.J. Forecasting, Detecting, and Tracking Volcanic Eruptions from Space. Remote Sens. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 3, 55–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, M.S.; Harris, A.J. Volcanology 2020: How will thermal remote sensing of volcanic surface activity evolve over the next decade? J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2013, 249, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, D.; Laiolo, M.; Cigolini, C.; Massimetti, F.; Delle Donne, D.; Ripepe, M.; Arias, H.; Barsotti, S.; Parra, C.B.; Centeno, R.G.; et al. Thermal remote sensing for global volcano monitoring: Experiences from the MIROVA system. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 7, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.J.L.; Swabey, S.E.J.; Higgins, J. Automated thresholding of active lavas using AVHRR data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1995, 16, 3681–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Harris, A. VAST: A program to locate and analyse volcanic thermal anomalies automatically from remotely sensed data. Comput. Geosci. 1997, 23, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffke, A.M.; Harris, A.J. A review of algorithms for detecting volcanic hot spots in satellite infrared data. Bull. Volcanol. 2011, 73, 1109–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganci, G.; Vicari, A.; Cappello, A.; Del Negro, C. An emergent strategy for volcano hazard assessment: From thermal satellite monitoring to lava flow modeling. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 119, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramutoli, V. Robust AVHRR techniques (RAT) for environmental monitoring: Theory and applications. In Earth Surface Remote Sensing II; SPIE: Cergy-Pontoise, France, 1998; Volume 3496, pp. 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Di Bello, G.; Filizzola, C.; Lacava, T.; Marchese, F.; Pergola, N.; Pietrapertosa, C.; Piscitelli, S.; Scaffidi, I.; Tramutoli, V. Robust satellite techniques for volcanic and seismic hazards monitoring. Ann. Geophys. 2004, 47, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tramutoli, V.; Cuomo, V.; Filizzola, C.; Pergola, N.; Pietrapertosa, C. Assessing the potential of thermal infrared satellite surveys for monitoring seismically active areas: The case of Kocaeli (Izmit) earthquake, August 17, 1999. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 96, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, N.; Marchese, F.; Tramutoli, V. Automated detection of thermal features of active volcanoes by means of infrared AVHRR records. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 93, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.; Flynn, L.; Garbeil, H.; Harris, A.; Pilger, E. Automated volcanic eruption detection using MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 82, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, L.P.; Wright, R.; Garbeil, H.; Harris, A.; Pilger, E. A global thermal alert system using MODIS: Initial results from 2000–2001. Adv. Environ. Monit. Model. 2002, 1, 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Piscini, A.; Lombardo, V. Volcanic hot spot detection from optical multispectral remote sensing data using artificial neural networks. Geophys. J. Int. 2014, 196, 1525–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradino, C.; Amato, E.; Torrisi, F.; Del Negro, C. Data-Driven Random Forest Models for Detecting Volcanic Hot Spots in Sentinel-2 MSI Images. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders-Shultz, P.; Lopez, T.; Dietterich, H.; Girona, T. Automatic identification and quantification of volcanic hotspots in Alaska using HotLINK: The hotspot learning and identification network. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1345104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooster, M.J.; Zhukov, B.; Oertel, D. Fire Radiative Energy for Quantitative Study of Biomass Burning: Derivation from the BIRD Experimental Satellite and Comparison to MODIS Fire Products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 86, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooster, M.J.; Roberts, G.; Perry, G.L.W.; Kaufman, Y.J. Retrieval of biomass combustion rates and totals from fire radiative power observations: FRP derivation and calibration relationships between biomass consumption and fire radiative energy release. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2005, 110, D24311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, D.; Laiolo, M.; Cigolini, C.; Delle Donne, D.; Ripepe, M. Enhanced volcanic hot-spot detection using MODIS IR data: Results from the MIROVA system. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2016, 426, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacava, T.; Marchese, F.; Arcomano, G.; Coviello, I.; Falconieri, A.; Faruolo, M.; Pergola, N.; Tramutoli, V. Thermal monitoring of Eyjafjöll volcano eruptions by means of infrared MODIS data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2014, 7, 3393–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, N.; Sansosti, E.; Marchese, F. Active volcanoes: Satellite remote sensing. In Natural Hazards; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 447–482. [Google Scholar]

- Zakšek, K.; Hort, M.; Lorenz, E. Satellite and ground based thermal observation of the 2014 effusive eruption at Stromboli volcano. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 17190–17211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, F.; Genzano, N.; Nolde, M.; Falconieri, A.; Pergola, N.; Plank, S. Mapping and characterizing the Kīlauea (Hawaiʻi) lava lake through Sentinel-2 MSI and Landsat-8 OLI observations of December 2020–February 2021. Environ. Model. Softw. 2022, 148, 105273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariello, S.; Corradino, C.; Torrisi, F.; Del Negro, C. Cascading Machine Learning to Monitor Volcanic Thermal Activity Using Orbital Infrared Data: From Detection to Quantitative Evaluation. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, N.; Marchese, F.; Tramutoli, V.; Filizzola, C.; Ciampa, M. Advanced Satellite Technique for Volcanic Activity Monitoring and Early Warning. Ann. Geophys. 2008, 51, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girona, T.; Realmuto, V.; Lundgren, P. Large-scale thermal unrest of volcanoes for years prior to eruption. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrisi, F. Automatic Detection of Volcanic Ash Clouds Using MSG-SEVIRI Satellite Data and Machine Learning Techniques. Il Nuovo C. C 2022, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Torrisi, F.; Corradino, C.; Cariello, S.; Di Bella, G.; Del Negro, C. Challenges and Opportunities in Deep Learning and Geostationary Satellite Remote Sensing for Volcanic Cloud Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 8th Forum on Research and Technologies for Society and Industry Innovation (RTSI), Milano, Italy, 18–20 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gouhier, M.; Harris, A.; Calvari, S.; Labazuy, P.; Guéhenneux, Y.; Donnadieu, F.; Valade, S. Lava discharge during Etna’s January 2011 fire fountain tracked using MSG-SEVIRI. Bull. Volcanol. 2012, 74, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrisi, F.; Amato, E.; Corradino, C.; Mangiagli, S.; Del Negro, C. Characterization of Volcanic Cloud Components Using Machine Learning Techniques and SEVIRI Infrared Images. Sensors 2022, 22, 7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, C.; Durão, R.; Gouveia, C.M. A Year of Volcanic Hot-Spot Detection over Mediterranean Europe Using SEVIRI/MSG. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrisi, F.; Corradino, C.; Cariello, S.; Del Negro, C. Enhancing Detection of Volcanic Ash Clouds from Space with Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2024, 448, 108046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirn, B.; Di Bartola, C.; Ferrucci, F. Combined use of SEVIRI and MODIS for detecting, measuring, and monitoring active lava flows at erupting volcanoes. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2009, 47, 2923–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradini, S.; Guerrieri, L.; Stelitano, D.; Salerno, G.; Scollo, S.; Merucci, L.; Prestifilippo, M.; Musacchio, M.; Silvestri, M.; Lombardo, V.; et al. Near real-time monitoring of the Christmas 2018 Etna eruption using SEVIRI and products validation. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, S.; Di Bartola, C.; Brenot, H. Operational Integration of Spaceborne Measurements of Lava Discharge Rates and Sulfur Dioxide Concentrations for Global Volcano Monitoring. In Early Warning for Geological Disasters; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smittarello, D.; Smets, B.; Barrière, J.; Michellier, C.; Oth, A.; Shreve, T.; Grandin, R.; Theys, N.; Brenot, H.; Cayol, V.; et al. Precursor-free eruption triggered by edifice rupture at Nyiragongo volcano. Nature 2022, 609, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminou, D. MSG’s SEVIRI Instrument. ESA Bull. 2002, 111, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, P.P.; Durand, Y.; Aminou, D.; Gaudin-Delrieu, C.; Lamard, J.-L. FCI Instrument On-Board MeteoSat Third Generation Satellite: Design and Development Status. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Space Optics—ICSO 2020, Online, France, 30 March–2 April 2021; Volume 11852, pp. 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Torrisi, F.; Amato, E.; Corradino, C.; Del Negro, C. The FastVRP Automatic Platform for the Thermal Monitoring of Volcanic Activity Using VIIRS and SLSTR Sensors: FastFRP to Monitor Volcanic Radiative Power. Ann. Geophys. 2023, 65, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganci, G.; Bilotta, G.; Dozzo, M.; Spina, F.; Zuccarello, F.; Cristofaro, R.; Guardo, R.; Spina, M.; Cappello, A. Multi-Platform Satellite-Derived Products during the 2025 Etna Eruption. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filizzola, C.; Mazzeo, G.; Marchese, F.; Pietrapertosa, C.; Pergola, N. The Contribution of Meteosat Third Generation–Flexible Combined Imager (MTG-FCI) Observations to the Monitoring of Thermal Volcanic Activity: The Mount Etna (Italy) February–March 2025 Eruption. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bella, G.S.; Corradino, C.; Cariello, S.; Torrisi, F.; Del Negro, C. Advancing Volcanic Activity Monitoring: A Near-Real-Time Approach with Remote Sensing Data Fusion for Radiative Power Estimation. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, M.; Neri, E. Integrating Geoscience, Ethics, and Community Resilience: Lessons from the Etna 2018 Earthquake. Geosciences 2025, 15, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 11/02/2025; Rep. N. 07/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 18/02/2025; Rep. N. 08/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 25/02/2025; Rep. N. 09/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 04/03/2025; Rep. N. 10/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 18/03/2025; Rep. N. 12/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 25/03/2025; Rep. N. 13/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 08/04/2025; Rep. N. 15/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 15/04/2025; Rep. N. 16/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 22/04/2025; Rep. N. 17/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 29/04/2025; Rep. N. 18/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 06/05/2025; Rep. N. 19/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 13/05/2025; Rep. N. 20/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 20/05/2025; Rep. N. 21/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 10/06/2025; Rep. N. 24/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 24/06/2025; Rep. N. 26/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 12/08/2025; Rep. N. 33/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 19/08/2025; Rep. N. 34/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 26/08/2025; Rep. N. 35/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- INGV-OE, Bollettino Etna Settimanale Del 02/09/2025; Rep. N. 36/2025 ETNA. Available online: www.ct.ingv.it (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Cariello, S.; Malaguti, A.B.; Corradino, C.; Del Negro, C. V-STAR: A Cloud-Based Tool for Satellite Detection and Mapping of Volcanic Thermal Anomalies. GeoHazards 2025, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, M.; Ghorbanian, A.; Ahmadi, S.A.; Kakooei, M.; Moghimi, A.; Mirmazloumi, S.M.; Moghaddam, S.H.A.; Mahdavi, S.; Ghahremanloo, M.; Parsian, S.; et al. Google earth engine cloud computing platform for remote sensing big data applications: A comprehensive review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 5326–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganci, G.; Cappello, A.; Bilotta, G.; Hérault, A.; Zago, V.; Del Negro, C. Digital Elevation Model of Mt Etna updated to 18 December 2015. [Data set]. PANGAEA 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUMETSAT MTG FCI Level 1c Data Guide. Available online: https://user.eumetsat.int/resources/user-guides/mtg-fci-level-1c-data-guide (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Home—LAADS DAAC. Available online: https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- EUMETSAT—Data Store. Available online: https://data.eumetsat.int/data/map/EO:EUM:DAT:0411 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Ramsey, M.S.; Corradino, C.; Thompson, J.O.; Leggett, T.N. Statistical Retrieval of Volcanic Activity in Long Time Series Orbital Data: Implications for Forecasting Future Activity. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 295, 113704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valade, S.; Ley, A.; Massimetti, F.; D’Hondt, O.; Laiolo, M.; Coppola, D.; Loibl, D.; Hellwich, O.; Walter, T.R. Towards global volcano monitoring using multisensor sentinel missions and artificial intelligence: The MOUNTS monitoring system. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouhier, M.; Guéhenneux, Y.; Labazuy, P.; Cacault, P.; Decriem, J.; Rivet, S. HOTVOLC: A web-based monitoring system for volcanic hot spots. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wooster, M.J.; Xu, W. Approaches for Synergistically Exploiting VIIRS I- and M-Band Data in Regional Active Fire Detection and FRP Assessment: A Demonstration with Respect to Agricultural Residue Burning in Eastern China. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 198, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wooster, M.J.; Polehampton, E.; Yemelyanova, R.; Zhang, T. Sentinel-3 Active Fire Detection and FRP Product Performance—Impact of Scan Angle and SLSTR Middle Infrared Channel Selection. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 261, 112460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, D.; Laiolo, M.; Piscopo, D.; Cigolini, C. Rheological Control on the Radiant Density of Active Lava Flows and Domes. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2013, 249, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, S.; Marchese, F.; Filizzola, C.; Pergola, N.; Neri, M.; Nolde, M.; Martinis, S. The July/August 2019 lava flows at the Sciara del Fuoco, Stromboli–Analysis from multi-sensor infrared satellite imagery. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aleo, R.; Bitetto, M.; Delle Donne, D.; Coltelli, M.; Coppola, D.; McCormick Kilbride, B.; Pecora, E.; Ripepe, M.; Salem, L.C.; Tamburello, G.; et al. Understanding the SO2 degassing budget of Mt etna’s paroxysms: First clues from the December 2015 sequence. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 6, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, S.; Massimetti, F.; Soldati, A.; Hess, K.-U.; Nolde, M.; Martinis, S.; Dingwell, D.B. Estimates of Lava Discharge Rate of 2018 Kīlauea Volcano, Hawaiʻi Eruption Using Multi-Sensor Satellite and Laboratory Measurements. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 42, 1492–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Steffke, A.; Calvari, S.; Spampinato, L. Thirty Years of Satellite-Derived Lava Discharge Rates at Etna: Implications for Steady Volumetric Output. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2011, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volc@Hazard. Available online: https://www.ct.ingv.it/technolab/volchazard (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Corradino, C.; Ganci, G.; Bilotta, G.; Cappello, A.; Del Negro, C.; Fortuna, L. Smart Decision Support Systems for Volcanic Applications. Energies 2019, 12, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Features | Spinning Enhanced Visible InfraRed Imager (SEVIRI) | Flexible Combined Imager (FCI) |

|---|---|---|

| Satellite | Meteosat Second Generation (MSG) | Meteosat Third Generation (MTG) |

| Number of Channels | 12 channels | 16 channels (Full Disc), 2 additional (Rapid Scan) |

| Spectral Range | 0.4–14.4 µm (VIS, NIR, IR) | 0.4–13.3 µm (VIS, NIR, IR) |

| Spatial Resolution | 3 km (IR channels), 1 km (HRV) | 2 km (IR), 1 km (VIS/NIR), 0.5 km (HRV) |

| Temporal Resolution | Full Disc every 15 min, Rapid Scan every 5 min | Full Disc every 10 min, Rapid Scan every 2.5 min |

| High-Resolution Channel | 1 broadband HRV | 2 HR channels (0.5 km resolution) |

| MSG-SEVIRI | MTG-FCI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Channels | Band No. | Wavelength [µm] | Spatial Resolution [km] | Band No. | Wavelength [µm] | Spatial Resolution [km] |

| VIS 0.4 | - | - | - | 1 | 0.444 | 1 |

| VIS 0.5 | - | - | - | 2 | 0.510 | 1–0.5 (HR) |

| VIS 0.6 | 1 | 0.635 | 3 | 3 | 0.645 | 1 |

| VIS 0.8 | 2 | 0.81 | 3 | 4 | 0.865 | 1 |

| VIS 0.9 | - | - | - | 5 | 0.914 | 1 |

| NIR 1.3 | - | - | - | 6 | 1.380 | 1 |

| NIR 1.6 | 3 | 1.64 | 3 | 7 | 1.61 | 1 |

| NIR 2.2 | - | 8 | 2.25 | 1–0.5 (HR) | ||

| IR 3.8 | 4 | 3.90 | 3 | 9 | 3.8 | 2–1 (HR) |

| WV 6.3 | 5 | 6.25 | 3 | 10 | 6.3 | 2 |

| WV 7.3 | 6 | 7.35 | 3 | 11 | 7.350 | 2 |

| IR 8.7 | 7 | 8.7 | 3 | 12 | 8.7 | 2 |

| IR 9.7 | 8 | 9.66 | 3 | 13 | 9.660 | 2 |

| IR 10.5 | 9 | 10.8 | 3 | 14 | 10.5 | 2–1 (HR) |

| IR 12.0 | 10 | 12.0 | 3 | 15 | 12.3 | 2 |

| IR 13.3 | 11 | 13.40 | 3 | 16 | 13.3 | 2 |

| HRV | 12 | - | 1 | - | - | - |

| Satellite Sensor | Temporal Resolution | Apixel [m2] | α | k | Saturation Temp | NetD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIIRS-I | Twice per day | 375 × 375 | 3.21 · 10−9 [74] | 2.48 · 107 |

MIR (3.753 μm): 367 K

TIR (11.469 μm): 380 K |

MIR: <2.5 K at 270 K

TIR: <1.5 K at 210 K |

| VIIRS-M | Twice per day | 750 × 750 | 2.87 · 10−9 [74] | 1.11 · 107 |

MIR (4.067 μm): 634 K

TIR (10.729 μm): 363 K |

MIR: 0.107 K at 300 K

TIR: 0.070 K at 300 K |

| MODIS | Twice per day | 1000 × 1000 | 3.0 · 10−9 [19] | 1.89 · 107 | MIR (3.959 μm): ~500 K TIR (11.030 μm): ~340 K | MIR: 0.07 K at 300 K TIR: 0.05 K at 300 K |

| SLSTR | Twice per day | 1000 × 1000 | 3.30 · 10−9 [75] | 1.70 · 107 |

MIR (3.74 μm): 311 K

MIR (3.74 μm): 500 K TIR (10.8 μm): 321 K TIR (10.8 μm): 400 K |

MIR (S7): <0.08 K at 270 K

MIR (F1): Not specified TIR (S8): <0.05 K at 270 K TIR (F2): Not specified |

| FCI | Every 10 min | 1000 × 1000 | 3.22 · 10−9 | 1.76 · 107 | MIR (3.8 μm): 450 K TIR (10.5 μm): ~340 K | MIR: 0.2 K @ 300 K TIR: 0.1 K @ 300 K |

| SEVIRI | Every 15 min | 3000 × 3000 | 1.38 · 10−8 | 3.70 · 107 |

MIR (3.9 μm): ~335 K

TIR (10.8 μm): ~335 K |

MIR: 0.35 K at 300 K

TIR: 0.25 K at 300 K |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Torrisi, F.; Di Bella, G.S.; Corradino, C.; Cariello, S.; Malaguti, A.B.; Del Negro, C. From MSG-SEVIRI to MTG-FCI: Advancing Volcanic Thermal Monitoring from Geostationary Satellites. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010006

Torrisi F, Di Bella GS, Corradino C, Cariello S, Malaguti AB, Del Negro C. From MSG-SEVIRI to MTG-FCI: Advancing Volcanic Thermal Monitoring from Geostationary Satellites. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorrisi, Federica, Giovanni Salvatore Di Bella, Claudia Corradino, Simona Cariello, Arianna Beatrice Malaguti, and Ciro Del Negro. 2026. "From MSG-SEVIRI to MTG-FCI: Advancing Volcanic Thermal Monitoring from Geostationary Satellites" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010006

APA StyleTorrisi, F., Di Bella, G. S., Corradino, C., Cariello, S., Malaguti, A. B., & Del Negro, C. (2026). From MSG-SEVIRI to MTG-FCI: Advancing Volcanic Thermal Monitoring from Geostationary Satellites. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010006