Highlights

What are the main findings?

- We make a review of mining-related eco-environmental issues that can be assessed from remote sensing.

- We describe different remote sensing platforms and data types used for monitoring.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- We discuss how remote sensing technology serves specific applications across different monitoring objectives throughout the entire mining lifecycle.

- We conclude with an overview of challenges, opportunities and future perspectives.

Abstract

Mining activities exert profound and long-lasting impacts on terrestrial eco-environmental systems, manifesting across multiple spatial and temporal scales throughout the mining lifecycle—from exploration and extraction to post-mining reclamation. Remote sensing technology serves as an advanced monitoring and analysis tool, playing a critical role in the continuous monitoring of mining-related eco-environmental disturbances. This work provides a systematic review of remote sensing applications for mining-related eco-environmental monitoring and assessment. We first outline the importance of mineral resource development and summarize the associated eco-environmental issues. The second section presents an overview of remote sensing platforms and data types currently employed for monitoring in mining areas. The third section systematically summarizes recent research advances in key mining-related eco-environmental dimensions, including spatiotemporal land-use and land-cover analysis, terrain and deformation monitoring, natural environmental factor disturbances assessment, comprehensive ecological-environment quality evaluation, and post-mining reclamation assessment. Finally, we analyze the opportunities, challenges and future perspectives associated with remote sensing applications in mining areas. This review aims to provide reference for advancing remote sensing-based eco-environmental monitoring in mining areas, thereby supporting more effective, long-term monitoring and informed decision-making within the mining sector.

1. Introduction

1.1. Importance of Mineral Resources Development

Mineral resources constitute a fundamental material foundation for socioeconomic development, providing essential support for global economic growth and industrial advancement [1,2,3]. Traditionally, minerals have underpinned the operation of heavy industries such as electricity, steel, and cement. More recently, they have emerged as a strategic cornerstone for building low-carbon energy systems, advancing digital transformation, and fostering sustainable development. Critical metals such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel are now indispensable for electric vehicles, renewable energy (e.g., wind and solar power), and the electronics industry [4,5,6]. Beyond their industrial significance, mineral resources development plays a vital role in promoting employment and improving livelihoods. Mining activities often create both direct and indirect job opportunities, contributing to local living standards and fiscal systems [7,8]. In resource-rich but economically underdeveloped regions, in particular, mining can effectively increase household incomes, enhance infrastructure, and promote social stability and regional growth [9,10,11]. Furthermore, mineral extraction exerts a strong driving force on national and regional economic expansion. As a key commodity in international trade, mineral exports yield substantial foreign exchange revenues, strengthening fiscal capacity, and enhancing global competitiveness [12,13]. For instance, in 2022–2023, the mining industry contributed USD 455 billion in export earnings to Australia—approximately two-thirds of the nation’s total export revenue [14]—while in 2022, mining accounted for 58% of Chile’s total export revenue [15]. In addition, mineral resources play an increasingly important role in driving technological innovation and international cooperation. Under the global energy transition, the stability and security of critical mineral supply chains have become central policy concerns [16]. This has spurred advances in resource exploration, extraction, and refining technologies [17], while also fostering cross-regional industrial partnerships and strategic alliances. In this context, mineral resources viewed not merely as an economic input, but also a critical pillar for global sustainable development and national strategic security.

1.2. Eco-Environmental Issue Caused by Mineral Resources Development

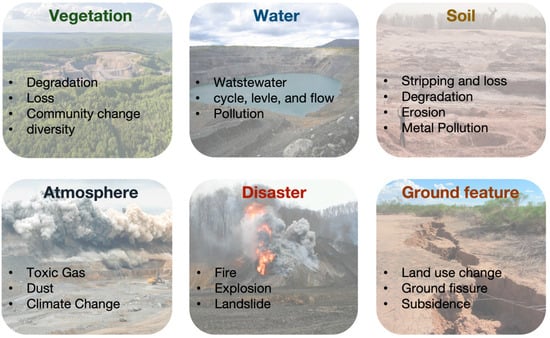

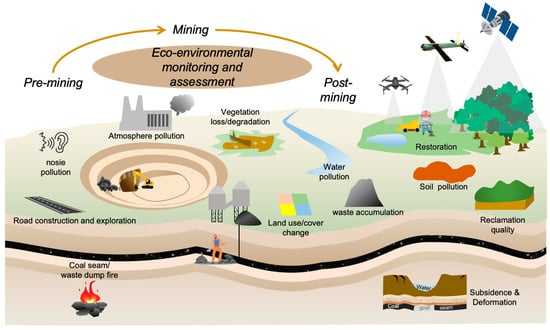

With the intensification of mineral resource exploitation to meet the growing demands of global economic development, conflicts between resource extraction and environmental sustainability have become increasingly prominent. These challenges encompass a wide range of eco-environmental issues, which are here categorized into six major aspects (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mining-related eco-environmental issues primarily involve vegetation, water, soil, atmosphere, disaster, and ground feature.

1.2.1. Vegetation

Mining often causes both direct and indirect damage to vegetation. Typically, mining operations involve the complete removal of surface soil and vegetation, resulting in large-scale losses of vegetation cover [18,19]. For instance, coal mining on the Mongolian Plateau has destroyed approximately 100,000 km2 of natural vegetation and cropland over the past four decades [20]. Beyond direct destruction, mining also exerts substantial indirect impacts on vegetation phenology and biodiversity in surrounding areas. The exposure of bare land post-mining increases local surface temperature and creates drier microclimates [21], thereby hindering natural vegetation regeneration. Combined with dust emissions, alterations in soil properties, and groundwater fluctuations, these processes can induce widespread changes in vegetation phenology [22,23], with effects extending up to 500–2000 m from mining sites [24,25]. Moreover, mining-induced disturbances frequently lead to reductions in vegetation diversity and species richness [26,27].

1.2.2. Water

Mining-induced aquifer disturbances can lead to groundwater depletion, loss of water resources, and a range of water-related environmental issues. Underground mining, in particular, often requires substantial groundwater extraction for production or mine dewatering, resulting in regional declines in groundwater level [28,29]. Furthermore, ground subsidence and fractures caused by underground mining can modify surface topography and alter precipitation runoff patterns, thereby affecting groundwater circulation [30,31]. In addition, mining operations are commonly associated with tailing and wastewater, which can infiltrate aquifers through the soil and cause heavy metal contamination in both surface water and groundwater [32,33]. When contaminant concentrations exceed drinking water standards, they may pose serious health risks to nearby communities [34].

1.2.3. Soil

Mining typically involves the direct removal of topsoil, which not only results in soil loss but also disrupts its natural structure. The use of heavy machinery leads to soil compaction, reducing porosity and diminishing water-holding capacity [35,36,37]. In the absence of vegetation, prolonged exposure to wind and water erosion can alter soil physicochemical properties, lowering organic matter and nutrient content [38,39]. Furthermore, the long-term accumulation of mining waste occupies extensive land resources, causing a severe depletion of soil resources [40]. These waste materials may also release large amounts of heavy metals, potentially leading to persistent soil contamination [41,42].

1.2.4. Atmosphere

Mining operation—including extraction, transportation, processing, and waste deposition—are often accompanied by substantial emissions of heavy-metal dust and respirable particulate matter. These particulates can readily disperse over large areas under wind action, severely degrading air quality in mining regions [43,44]. The particulates may contain toxic elements (e.g., lead, arsenic, mercury) which, once transported through the atmosphere and deposited, can further contaminate surrounding soils and water bodies [45,46,47,48]. Moreover, smelting and fuel combustion release substantial amounts of sulfides, nitrogen oxides, and carbon monoxide [49], which are easily converted into acidic compounds in the atmosphere.

1.2.5. Disaster

Mining disrupts original geological structures and surface environments, thereby driving a range of geological disasters that have severe impacts on both local ecosystems and human settlements. Underground mining often induces the deformation of rock and soil masses, characterized by large-scale ground subsidence or localized collapse [50,51,52]. Opencast mining involves extensive slope stripping, which significantly increases the risk of slope instability. Under the influence of rainfall and seismic events, these slopes are highly susceptible to landslides and rockfalls [53,54]. Exposed coal seams or accumulated coal gangue are highly prone to spontaneous combustion under conditions of oxidation and heat accumulation, causing long-term underground or surface fires that release substantial heat and pollutants [55,56,57,58]. Additionally, explosion hazards induced by mine gases (e.g., CH4) and coal dust have been widely reported [59,60], posing significant threats to the safety of miners.

1.2.6. Ground Feature

Mineral resources development is often accompanied by both direct and indirect geomorphological changes. Opencast mining directly removes surface features such as soil and vegetation, leading to immediate land-use changes [61]. Moreover, it generates large-scale anthropogenic landforms, including mining pits, stepped slopes, and substantial waste deposits (e.g., coal waste dumps) [62]. In contrast, underground mining disrupts the original stress equilibrium of rock strata, causing deformation of surrounding layers that subsequently induces surface subsidence and fissures [63,64]. Such large-scale subsidence can also indirectly modify surface characteristics; for instance, in mining areas with high groundwater tables, surface waterlogging may occur, thereby transforming terrestrial ecosystems and altering vegetation cover types [65,66,67].

1.3. Aim of This Study

With the rapid advancement of remote sensing technologies, their applications have expanded in both depth and breadth. The emergence of multi-scale and multi-modal remote sensing datasets, coupled with advanced algorithms and computational platforms, has highlighted the substantial potential of remote sensing for monitoring and assessing eco-environmental conditions in mining areas. The impacts of mineral resource exploitation are inherently complex, diverse, large-scale, and long-lasting, which makes full life-cycle monitoring particularly challenging. Under the ongoing global energy transition, mining is expected to remain a critical activity, while its associated environmental impacts are likely to persist as long-term issues. Although recent remote sensing-based studies have demonstrated substantial progress, existing reviews mainly focus on individual monitoring techniques or specific environmental components [68,69,70,71,72], and a systematic synthesis across the full mining lifecycle is still lacking.

In this context, the present review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of current applications of remote sensing in mining-related eco-environmental monitoring and assessment. This review is structured as follows: (i) We first introduce the research background, highlighting the importance of mineral resources and the wide-ranging eco-environmental impacts of mining; (ii) We provide a brief overview of remote sensing technologies, including diverse platforms and data types; (iii) We systematically synthesize recent research progress to present key remote sensing applications for full life-cycle monitoring and assessment of mining activities; (iv) Finally, we discuss future opportunities and current challenges of remote sensing technologies in monitoring the eco-environmental impacts of mining. Overall, this study establishes a framework that systematically likes mining-induced eco-environmental disturbances with corresponding remote sensing monitoring and assessment tasks, thereby providing targeted scientific support for environmental management and decision making in mining regions.

2. Remote Sensing Technology

2.1. Remote Sensing Platform

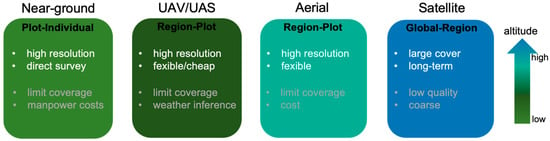

For mining-related eco-environmental monitoring, different types of disturbances exhibit distinct spatiotemporal characteristics. Based on different monitoring demands, remote sensing platforms can be categorized into four types: satellite, aerial, unmanned aerial vehicle /system, and near-ground remote sensing (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Different remote sensing platforms used for eco-environmental monitoring in mining areas, classified by observation altitude.

2.1.1. Satellite

Satellite remote sensing serves as the primary data source for large-scale and long-term monitoring of mining-induced eco-environmental changes. It has provided critical support for studies on land cover change, vegetation monitoring, and surface subsidence associated with mining activities [24,72,73,74,75]. However, most publicly available datasets remain at medium-to-low resolution (e.g., MODIS, 500 m) or medium resolution (e.g., Sentinel, 10 m; Landsat, 30 m), limiting their capacity to capture fine-scale impacts at the plot level. Moreover, common issues such as cloud cover and cloud shadows frequently degrade image quality [76,77,78].

2.1.2. Aerial

Aerial remote sensing, which primarily relies on manned aircraft or plane for data acquisition, offers high spatial resolution and flexible sensor configurations. This approach enables rapid monitoring of topography and vegetation cover across mining areas at regional scales (tens to hundreds of square kilometers) [79,80,81,82]. Nevertheless, compared to satellite data, its spatial coverage is limited. Furthermore, aerial surveys require specialized equipment and traditional personnel, making them costly and less suitable for applications requiring high temporal resolution or continuous monitoring.

2.1.3. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle/System

Declining costs and increasing payload versatility have made unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) an effective platform for environmental monitoring in mining areas [68]. UAVs are highly flexible and, by carrying diverse sensor types, can acquire centimeter-level data on topography, spectral characteristics, and thermal conditions at region-plot scales [83,84]. In mining-related applications, UAVs are particularly effective for detailed monitoring of pits, waste dumps, tailing ponds, and reclamation sites. However, flight endurance is often constrained by battery capacity, particularly over large areas. Additionally, the quality of UAV-derived data is frequently influenced by weather conditions and the performance of onboard sensor components [85].

2.1.4. Near-Ground Instrument

Ground-based remote sensing instruments (e.g., terrestrial LiDAR, field spectrometers, and thermal infrared cameras) provide high-precision observations, making them ideal for plot- or individual-scale applications and for continuous monitoring at fixed locations [86,87,88,89]. Nevertheless, their deployment often requires substantial human and material resources, and their spatial coverage is inherently limited. Consequently, ground-based systems play a critical supporting role in mining studies by providing ground truth data for the calibration and validation of remote sensing products [90,91,92,93].

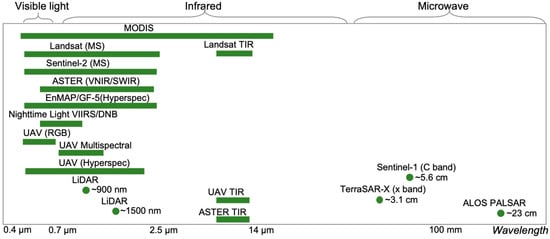

2.2. Remote Sensing Data Types

Remote sensing technology acquires data across various regions of the electromagnetic spectrum, with each spectral band exhibiting unique sensitivity to key surface features, including vegetation, soil, water, and minerals. Among these data types, optical, infrared, and microwave remote sensing have demonstrated particularly high relevance for addressing key eco-environmental issues associated with mining activities (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Different remote sensing data types used for eco-environmental monitoring in mining areas.

2.2.1. Visible Light Data

Visible light remote sensing is most widely used data type in mining area, primarily capturing the reflectance characteristics of surface features within the ~400–700 nm wavelength range. Given that different surface materials exhibit distinct spectral responses in the visible domain, visible light data effectively reveal vegetation cover and land-use patterns within these regions. Common satellite remote sensing platforms, including MODIS, Landsat 5/7/8, and Sentinel-2, provide visible bands with spatial resolutions ranging from 10 to 500 m. Time-series analysis of visible imagery facilitates monitoring of tailings accumulation and post-mining vegetation recovery. At finer scales, UAVs equipped with visible cameras acquire centimeter-level resolution imagery, providing a highly accessible and cost-effective means for high-precision vegetation surveys in mining areas [83,94,95]. Furthermore, it also has been widely applied for surface deformation monitoring and three-dimensional (3D) mapping of pits and waste dumps [62,96,97,98].

2.2.2. Infrared Data

Infrared remote sensing primarily encompasses the near-infrared (NIR), shortwave infrared (SWIR), and thermal infrared (TIR) regions, providing critical information on eco-environmental processes in mining areas. The NIR range (~0.7–1.3 μm) is highly sensitive to vegetation properties and plays a pivotal role in vegetation monitoring. For instance, the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), derived from the red and NIR bands [99], is one of the most widely used vegetation indices for assessing vegetation loss, degradation, and post-mining restoration [18,100,101,102]. Rededge-based indices are also commonly applied to indicate vegetation health [103,104,105]. Representative satellite platforms, including Landsat 5/7/8, Sentinel-2, ASTER VNIR, and EnMAP/GF-5 (Hyperspec), provide time-series data at regional to global scales. UAV-based multispectral sensors (e.g., Micasense RedEdge, Parrot Sequoia) and hyperspectral sensors (e.g., SPECIM FX, Headwall Photonics) enable acquisition of centimeter-resolution spectral data suitable for high-precision monitoring at the plot scales. The SWIR range (~1.3–2.5 μm) is sensitive to the spectral characteristics of soils, rocks, and minerals, making it a key data source for mineral identification, dust analysis, and tailings monitoring [106,107,108,109]. For example, ASTER SWIR, with six dedicated bands, has been widely applied to extract mineral alteration zones [110], while SWIR-derived indices are effective for detecting soil moisture variations in mining areas [111,112,113]. Thermal infrared (TIR, ~8–14 μm) remote sensing captures surface temperature anomalies, with significant applications in monitoring thermal disturbances such as coal seam fires and spontaneous combustion of coal waste dump [114,115,116]. Satellite platforms such as Landsat TIR and ASTER TIR provide long time-series datasets to monitor dynamic thermal anomaly evolution. At finer scales, UAV-based thermal cameras allow high-precision detection of localized temperature anomalies [117,118]. Additionally, UAV-based light detection and ranging (LiDAR) systems acquire high-precision 3D structural information on both terrain and vegetation, making them widely applicable for subsidence monitoring and reclamation vegetation assessment [119,120,121,122,123].

2.2.3. Microwave Data

Microwave remote sensing is indispensable for mining-related deformation monitoring, particularly in areas where optical observations are frequently limited by cloud cover or dense vegetation. It offers distinct advantages, including cloud penetration and all-weather, day-and-night observation capabilities. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) interferometry (InSAR) enables millimeter-level monitoring of surface deformation, with techniques such as Differential InSAR (D-InSAR), Permanent Scatterer InSAR (PS-InSAR), and Small Baseline Subset InSAR (SBAS-InSAR) widely applied to detect mining-induced subsidence and deformation, as well as to assess the stability of goaf areas [124,125,126,127,128]. Furthermore, given the inherent limitations of optical sensors, such as image saturation and poor quality in densely vegetated areas, SAR data are frequently combined with optical imagery to accurately estimate vegetation physiological parameters [129,130]. Furthermore, both active and passive microwave data (e.g., Sentinel-1 SAR, SMAP) can penetrate clouds and vegetation cover, enabling assessment of mining-induced changes in soil moisture [131,132].

3. Remote Sensing-Based Eco-Environmental Monitoring and Assessment

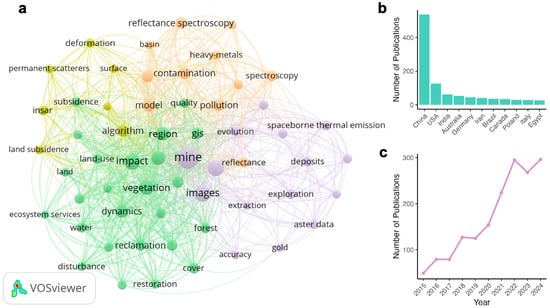

3.1. Overview of the Literature Publication

To conduct this systematic review, a statistical overview of literature publications is retrieved from the Web of ScienceTM Core Collection Database, covering the period 2015 to 2024. We use the following keyword combinations [“remote sensing” AND (“mine(s)” OR “mining”)] to restrict our analysis. Only peer-reviewed journal articles and reviews published in English are included in the analysis. Furthermore, conference proceedings, book chapters, and non-English publications are excluded. Following a manual screening process to exclude irrelevant publications, a total of 1030 records is retained for subsequent analysis. We employ VOSviewer software (version 1.6.20) [133] to perform keyword clustering and merge synonymous terms. It is a powerful tool that enables intuitive analysis of relationships within large academic publication datasets by constructing visual bibliometric networks. Figure 4a presents a keyword co-occurrence network, in which nodes represent keywords, with larger nodes indicating higher occurrence frequencies, while links between nodes denote co-occurrence relationships, and link thickness reflects the frequency of co-occurrence. It is observed that the co-occurrence is classified into four major clusters, each containing 8 to 24 keywords. The yellow cluster is associated with land surface change monitoring (e.g., deformation, land subsidence, InSAR), the orange cluster relates to pollution monitoring (e.g., heavy metals, contamination, pollution), the purple cluster corresponds to mining excavation (e.g., mine, exploration, gold, deposits), and the green cluster focuses on ecological and environmental monitoring (e.g., vegetation, land-use, ecosystem service value, forest, reclamation). Notably, the green cluster contains the largest number of keywords and exhibits the highest overall occurrence frequency, highlighting the growing emphasis on remote sensing-based eco-environmental monitoring in mining areas. The top ten publishing countries are China, the United States, India, Australia, Germany, Iran, Brazil, Canada, Poland, Italy, and Egypt (Figure 4b). Notably, China contributes the largest number of publication (536), accounting for more than 50% of the global total. The number of publications has steadily increased, growing from 29 publications in 2015 to 191 publications in 2024—a more than sixfold growth (Figure 4c). This trend underscores the rapid development and application of remote sensing technology in mining areas.

Figure 4.

Statistical analysis of publications from the Web of ScienceTM Core Collection during 2015–2024: (a) Keywords co-occurrence network generated using VOSviewer software. Each node represents a keyword, and node size reflects the frequency of keyword occurrence; (b) Ranking of countries by the number of published studies; (c) Annual number of published studies.

3.2. Demand for Full Life-Cycle Monitoring and Assessment in Mining Areas

Mining, as an intensive human activity, typically exerts continuous impacts throughout its entire life cycle—from pre-extraction resource exploration, active mining, to post-mining restoration—thereby imposing substantial demands on eco-environmental monitoring and assessment in mining areas (Figure 5). In this context, remote sensing technology, with its advantages of non-contact, large-scale spatial coverage, and continuous temporal observations, has emerged as a key technology for identifying and quantifying mining-related eco-environmental changes.

Figure 5.

Demands and requirement for the full life-cycle monitoring and assessment in mining areas.

In the pre-extraction stage, large-scale resource exploration, temporary access road construction, and engineering activities often result in habitat disturbance, stress on plant and animal communities, and the expose of local residents to noise pollution. High-resolution optical imagery and LiDAR data enable the construction of baseline land-cover maps, the detection of habitat fragmentation, and the quantification of pre-mining vegetation structure. Nighttime light data have also been employed to track the expansion of roads and infrastructure, thereby revealing early mining footprints. During the active mining operation stage, significant land-use changes, vegetation loss, air pollution, and soil and water contamination collectively substantially alter regional ecological patterns. Surface subsidence and fire of coal seams/coal waste dumps further exacerbate geological hazards. Optical imagery remains effective for detecting changes in land-use, vegetation degradation, and soil erosion. Thermal infrared data derived from UAVs and satellite thermal bands can identify thermal anomalies, while interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) enables continuous, centimeter-level monitoring of surface subsidence, particularly in underground mining areas. In the post-mining stage, tailings deposition and waste accumulation often occupy land for long periods and can introduce persistent environmental pollution. Insufficient ecological restoration, coupled with inadequate oversight and maintenance, often leads to delayed ecosystem recovery or even restoration failure. Time series satellite images can be used to reconstruct vegetation recovery trajectories, while LiDAR and UAV photogrammetry support fine-scale assessments of detailed vegetation type and structural characteristics.

Although remote sensing technology provides diverse datasets across multiple spatial resolutions and types, a key challenge for future research is the effective integration these datasets to enhance monitoring in mining areas. Building on previous studies, the following sections summarize remote sensing applications for mining-related eco-environmental monitoring across five key aspects, providing insights into improving full life-cycle monitoring.

3.3. Land-Use and Land Cover (LULC) Spatiotemporal Analysis

Severe land-use and land-cover changes (LULC) changes induced by mining are among the most prominent eco-environmental issues in mining areas [61,134,135]. Open-pit mining directly removes surface vegetation and soil, drastically altering regional land-use patterns [136,137]. As the mining footprint expands, original land-cover types may undergo complete transformation. Accurate and continuous LULC information is critical for evaluating environmental impacts and provides a foundation for designing restoration measures and planning sustainable management strategies [138]. Furthermore, spatiotemporal quantification of LULC enables researchers and decision-makers to better understand the combined ecological, environmental, and socioeconomic impacts of mining [139]. Given the challenges of conducting traditional field surveys in remote or high-risk mining areas, remote sensing technology provides essential support by enabling near-real-time, repeatable monitoring of LULC dynamics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of different classification methods.

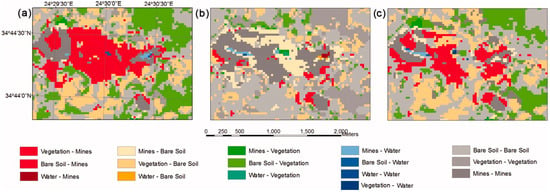

In the early stage of mining-related LULC mapping, visual interpretation is widely adopted as a fundamental approach. By comprehensively considering color, shape, and contextual information, manual interpretation can achieve high accuracy and is often regarded as the reference standard for validating automated classification results. However, this approach is highly labor-intensive, time-consuming, and subject to interpreter experience, which limits its applicability for large-scale LULC monitoring in mining areas. Pixel-based classification methods, which combines time-series optical remote sensing imagery with machine learning algorithms, is widely used for LULC classification. For example, Petropoulos et al. (2013) mapped Land-use changes in open-pit mining areas using Landsat imagery combined a support vector machine (SVM) classifier, revealing mining expansion and land reclamation process over a 23-year period [134] (Figure 6). Also, Chen et al. (2019) [140] used WorldView-3 data with SVM algorithm for detailed land-cover classification in mining areas. However, pixel-based classification relies solely on the spectral information of individual pixels, ignoring geometric features and contextual relationships. This frequently leads to the undesirable “salt-and-pepper effect,” particularly in high-resolution imagery [65]. With the proliferation of high-resolution imagery, researchers introduced object-based image analysis (OBIA), which aggregates pixels with similar spectral, textural, or geometric features into objects or patches, thereby significantly improving classification accuracy and spatial consistency [141,142,143,144,145]. More recently, deep learning methods have been widely applied to detailed mining classification, demonstrating superior accuracy and robustness in recognizing complex mining landscapes [141,146,147,148,149,150,151]. From a data perspective, optical imagery has historically been the primary source for LULC change monitoring in mining areas, as vegetation, water bodies, and mine pits exhibit distinct spectral differences. However, single-source data are often insufficient to capture the complex and dynamic processes inherent in mining environments. Consequently, an increasing number of studies integrate multi-source datasets (e.g., terrain information, nighttime light information) to capture comprehensive mining characteristics and substantially enhance classification accuracy [139,142,152,153].

Figure 6.

Land-use change detection in open-pit mining areas (Aggeria, Greek island of Milos) based on Landsat imagery for (a) 1987–2003, (b) 2003–2010, and (c) 1987–2010. Details in [134].

3.4. Terrain Survey and Deformation Monitoring

Mining operations induce profound disturbances to local topography and geomorphology. Open-pit mining involves large-scale removal of surface soil and vegetation, fundamentally reshaping the original slope morphology [154,155]. The waste rock and tailings generated during excavation are typically deposited in steep, structurally unstable artificial landforms [62,156], which are susceptible to subsidence, landslides, and other geohazards under wind and rainfall erosion [157]. Conversely, underground mining induces tensile, fractured, and bending deformation of the overburden above the goaf, resulting in surface subsidence, fissure propagation, and long-term progressive deformation [158]. These processes not only pose severe safety threats to infrastructure such as buildings, roads, and pipelines [159], but also exacerbate vegetation degradation and soil nutrient depletion [160]. Consequently, precise topographic mapping and continuous deformation monitoring are essential for safe mine management and the planning of ecological restoration.

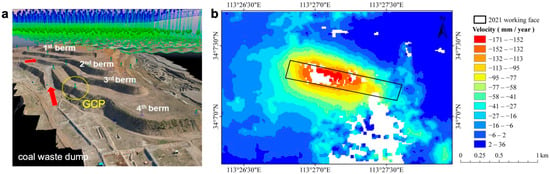

Remote sensing has emerged as a core approach for topographic surveying and subsidence monitoring in mining areas. At the local scale, UAV-based optical imaging integrated with Structure-from-Motion (SfM) and Multi-View Stereo (MVS) techniques enables centimeter-resolution reconstruction of Digital Surface Models (DSMs) and Digitial Elevation Models (DEMs) (Figure 7). These high-resolution products accurately capture the three-dimensional morphology of open-pit slopes and waste dumps [62,161] and can detect fine-scale mining fissures [162,163,164,165]. By comparing repeated surveys, these models also allow high-precision detection of localized subsidence [96,166]. Compared to traditional aerial photogrammetry, this approach requires fewer ground control points (GCPs) and offers a higher degree of automation, thus mitigating the limited coverage and safety risks of ground-based or GNSS measurements. It is also considerably more cost-effective and flexible than airborne or terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) systems. Furthermore, UAV-LiDAR system can penetrate dense canopy cover to retrieve the underlying terrain surface, providing unique advantages in forested or densely vegetated mining environments [121,167]. At the regional scale, Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) provides an effective solution for deformation monitoring due to its wide spatial coverage, high accuracy, and low acquisition cost. Differential InSAR (D-InSAR) is particularly suitable for detecting rapid subsidence during the early stages of mining [168,169,170], though its accuracy may deteriorate when temporal or spatial baselines become excessively large [171,172]. For long-term deformation analysis, time-series InSAR techniques—such as Small Baseline Subset (SBAS-InSAR) and Persistent Scatterer InSAR (PS-InSAR)—can effectively suppress atmospheric and decorrelation noise by leveraging multi-temporal observations, which makes them particularly advantageous for monitoring gradual subsidence [127,173,174,175,176]. Moreover, integrating InSAR with UAV-based surveys and GNSS observations further enhances mapping accuracy and enables a more comprehensive understanding of the spatial extent and temporal evolution of surface deformation [126,177,178,179].

Figure 7.

Terrain mapping and deformation monitoring in mining areas using remote sensing technologies: (a) DSM of a coal waste dump reconstructed from UAV visible imagery. Details in [62]; (b) Average annual subsidence rate of a mining area estimated by SBAS-InSAR. Details in [176].

3.5. Natural Environmental Factor Disturbance

3.5.1. Vegetation Disturbance

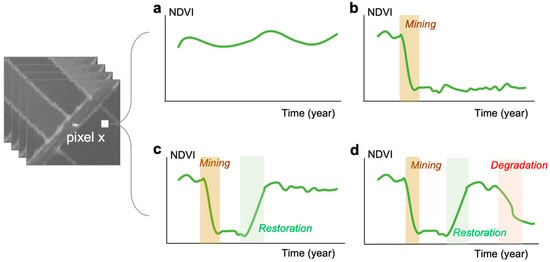

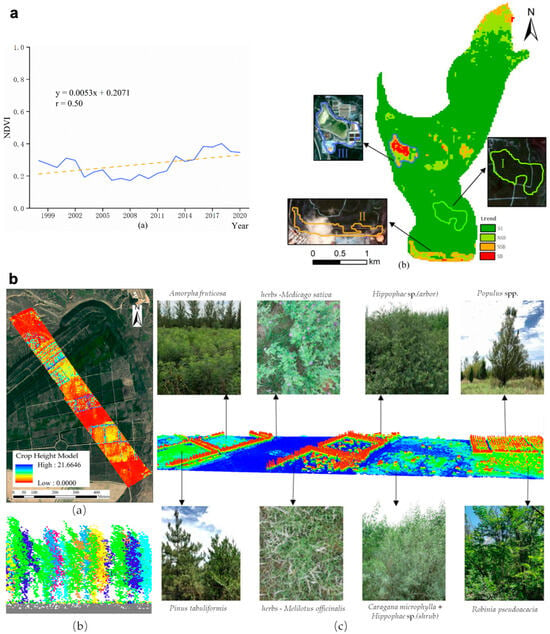

Vegetation disturbance represents one of the most direct and sensitive ecological indicators of mining activities. Open-pit extraction leads to immediate vegetation loss through large-scale stripping of surface layers, whereas underground mining indirectly causes degradation by altering soil structure and hydrological conditions through subsidence. Vegetation indices (VIs) derived from spectrally sensitive bands, such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), provide robust metrics for characterizing vegetation cover and productivity, thereby providing effective tools for monitoring vegetation changes associated with mining operations [102,180]. At large spatial scales, multi-year satellite observations enable direct quantification of vegetation loss and subsequent recovery by examining interannual variations in these indices [181,182,183] (e.g., Figure 8). However, analyses based on individual years or isolated time points often capture only transient conditions and may fail to detect the cumulative ecological impacts of such high-frequency and high-intensity disturbance. To overcome this limitation, time-series remote sensing imagery combined with trajectory-based change detection algorithms (e.g., LandTrendr [184], CCDC [185]) have been increasingly applied to monitor vegetation dynamics in mining areas. These approaches reconstruct pixel level disturbance trajectories, enabling detailed quantification of the spatiotemporal evolution of vegetation disturbance, land reclamation, and ecological recovery processes [72,186,187,188,189,190,191]. At the local scale, UAV-based remote sensing provides centimeter-level monitoring capability, offering valuable insights into the fine-scale assessment of post-mining vegetation recovery [84,192,193]. The increasing diversification of UAV payloads—including optical, multispectral, thermal infrared, and LiDAR—has greatly enhanced data acquisition flexibility and cost-effectiveness, while improving prediction accuracy [83] and expanding applicability across heterogeneous environments. In particular, UAV-LiDAR system exhibits a distinct in densely vegetated or structurally complex terrains [119,123,194], as it penetrates canopy layers to retrieve detailed three-dimensional vegetation structure. Moreover, the fusion of satellite and UAV data has emerged as a rapidly developing direction, as it compensates for the coarse spatial resolution of satellite imagery and the limited temporal continuity of UAV imagery [195,196].

Figure 8.

Examples of annual NDVI trajectories illustrating distinct vegetation responses to mining and post-mining reclamation or restoration: (a) Pixel with no mining disturbance, showing only minor NDVI fluctuations or remaining largely stable; (b) Pixel with mining disturbance but not experience restoration, characterized by a rapid NDVI decline followed by persistent low values; (c) Pixel with mining disturbance and subsequently experience artificial restoration, showing a rapid NDVI decline followed by recovery and stabilization with minor fluctuation; (d) Pixel with mining disturbance and restored but later degradation, displaying an initial NDVI decline and recovery phase followed a renewed downward trend.

3.5.2. Soil Disturbance

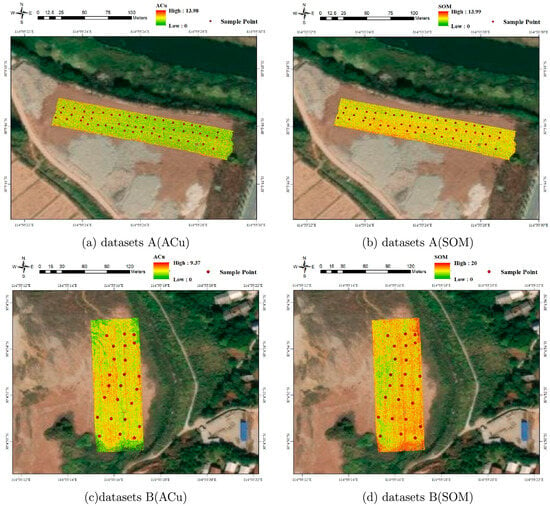

Soil stripping and disturbance during mining process induce substantial alterations in soil physical and chemical properties. Open-pit mining directly removes topsoil, leading to structural degradation, nutrient depletion, and a reduction in water-holding capacity [197]. Underground mining-induced subsidence modifies soil porosity, bulk density, and organic matter content [198,199,200], and may result in secondary waterlogging in areas with high groundwater tables [198]. Moreover, mining serves as a major source of heavy metal contamination in soils [42]. Conventional soil investigations primarily rely on field sampling, laboratory chemical analysis, and subsequent geostatistical modeling [201,202]. When combined with GIS, these approaches can effectively characterize the spatial heterogeneity of soil properties and identify potential sources of heavy metal pollution [157]. However, they are often labor-intensive, time-consuming, and costly. In contrast, remote sensing provides a large-scale, minimally invasive, and efficient alternative for monitoring soil physicochemical properties and heavy metal contamination. Spectral information in the visible, near-infrared, and shortwave infrared ranges is highly sensitive to soil attributes [203,204,205], and has been widely applied to soil quality assessment and pollution detection [206,207]. By integrating limited field sampling with spectral feature extraction, regression models based on machine learning and deep learning algorithms [208,209,210,211,212,213] have been developed to enable rapid mapping of soil properties. For example, ref. [210] employed UAV-based hyperspectral imagery in combination with a deep learning model (SA-DNN) to accurately predict soil available copper (ACu) and soil organic matter (SOM) in tailings areas, achieving an R2 of 0.89 for both prediction models (Figure 9). With the increasing availability of time-series and high-resolution imagery, remote sensing now supports dynamic monitoring and fine-scale assessment of soil attributes over large regions [210,214,215]. Furthermore, it has greatly improved soil erosion monitoring in mining areas. The Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE), a widely used model for global soil erosion estimation, can be readily integrated with GIS and remote sensing datasets to retrieve key parameters (e.g., terrain slope, vegetation cover), enabling quantitative evaluations of erosion intensity [216,217,218]. At finer spatial scales, UAV-derived DEMs combined with morphological detection algorithms can accurately identify rills and other microtopographic erosion features, facilitating detailed analyses of slope erosion processes [157,219,220,221].

Figure 9.

Spatial distribution of soil available copper (ACu) and soil organic matter (SOM) in tailing areas predicted using UAV-based hyperspectral data and deep learning model (SA-DNN). Details in [210].

3.5.3. Water Disturbance

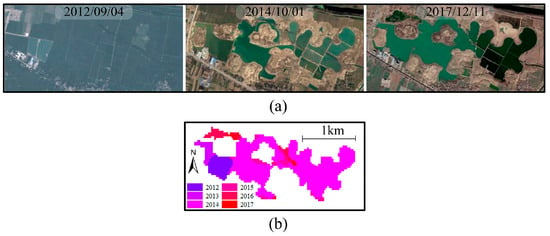

Mining activities exert persistent impacts on regional water systems, primarily through mine drainage and tailings dam failures, which collectively contribute to severe water pollution. These processes are highly dynamic and spatially heterogeneous, making continuous, large-scale monitoring challenging for conventional field-based observations. Remote sensing provides a rapid, cost-effective, and spatially extensive alternative, as reflectance in specific spectral bands can sensitively indicate variations in water quality [222,223]. For instance, water turbidity is closely correlated with reflectance in the red and near-infrared bands [224]. Long-term time-series observations further enable the detection of temporal trends in water contamination and facilitate the assessment of mining-induced water quality degradation [225,226]. In addition, underground mining-induced subsidence alters aquifer structures and subsequently reconfiguration of surface hydrological patterns. Recent studies [227,228] have demonstrated that optical remote sensing-based water indices and soil moisture indices can effectively identify subsidence-induced water bodies and understand their formation and stabilization processes (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Detection of water accumulation years in subsided water bodies based on time-series Landsat imagery. (a) Google Earth imagery reveals the temporal evolution of subsided water bodies; (b) Formation years of these water bodies identified from Landsat-based analysis. Details in [228].

3.5.4. Thermal Anomalies

Thermal anomalies are a primary type of ecological disturbance caused by mining activities, characterize by localized surface heating resulting from excavation and vegetation removal [21,229,230], and spontaneous combustion of coal seams [231,232] or coal waste dumps [114,233,234]. These anomalies not only signify substantial energy losses but also pose serious threats to mine safety and surrounding ecosystems. Thermal infrared sensing has proven highly effective for detecting and monitoring such anomalies [235]. By integrating satellite data (e.g., Landsat, ASTER) with single-channel or atmospheric-window-based surface temperature retrieval algorithms, researchers can monitor the intensity, spatial distribution, and evolution of large-scale heat anomalies [57,236,237,238]. Time-series analyses further enable tracking of persistent combustion dynamics and forecasting their development [239,240,241] (Figure 11a). Combining thermal information with radar-based surface deformation data enhances the detection of deeper or concealed underground coal fires [116,242,243,244,245]. However, satellite imagery generally lacks sufficient spatial resolution for small or relatively “cold” fires, and detecting early-subsurface smoldering in coal waste dumps remains a challenge [246,247]. Although airborne thermal infrared sensing offers high precision, its high operational cost limits large-scale applications. In contrast, UAV-based thermal infrared sensing has recently gained increasing application due to its high spatial resolution, rapid revisit frequency, and low cost, allowing early detection and fine-scale evaluation of mitigation efforts [92,117,118,248] (Figure 11b). Nevertheless, satellite remote sensing remains indispensable for reconstructing combustion history and capturing the long-term dynamics of thermal anomalies.

Figure 11.

Mining thermal anomalies detection based on remote sensing technology: (a) Time series ground temperature inversion results (2015–2017) from Landsat images in coal fire area. Details in [243]; (b) Land surface temperature estimation results obtained from UAV thermography in coal fire area. Details in [118].

3.6. Comprehensive Assessment of Ecological Environment Quality

The ecological environment encompasses the overall quantity and quality of water, land, biological, and climatic resources that influence human survival and development. Mining activities impose multidimensional and long-lasting pressures on regional ecosystems, manifesting as complex interactions among environmental, ecological, economic, and social dimensions [249]. Accordingly, a comprehensive assessment of ecological environment quality in mining areas is essential for sustainable regional management and environmental restoration planning.

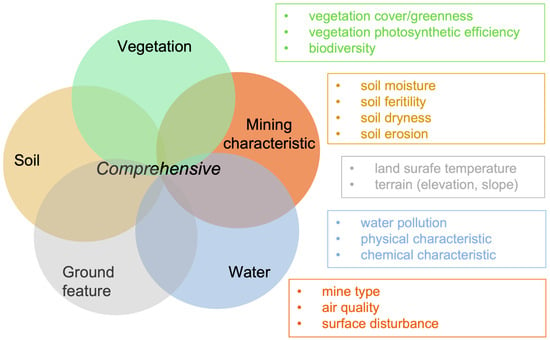

Remote sensing indices serve as powerful tools for quantifying ecosystem dynamics. Vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI, EVI) capture changes in vegetation systems, while land surface temperature reflects surface energy balance. Although these single indicators effectively represent specific ecosystem components, they often fail to capture the integrative and cumulative efforts of mining disturbances [250]. To overcome these limitations, researchers have developed comprehensive frameworks that combine multiple indicators from both landscape and ecological perspectives (Figure 12), often integrating remote sensing and geographic information system (GIS) techniques for spatiotemporal evaluations of environmental quality in mining areas [251,252,253,254]. A notable example is the Remote Sensing-Based Ecological Index (RSEI) proposed by Xu et al. (2013) [255], which integrates multiple surface environmental factors—including surface temperature, vegetation cover, soil moisture, and soil dryness—directly derivable from remote sensing. This index enables the rapid and comprehensive detection of regional ecological conditions and has therefore been widely applied in long-term assessments of ecological environment quality in mining areas [256,257,258,259,260,261]. For example, ref. [258] used the RSEI to assess ecological environmental quality in the Muli coalfield near Qinghai Lake over a 20-year period, demonstrating that the observed degradation was negatively influenced by open-pit mining activities (Figure 13). Given the unique characteristics of mining ecosystems, various adaptations have been proposed to enhance sensitivity and applicability of RSEI. For instance, modifications include replacing NDVI with net primary production (NPP) [262]; developing mine-specific indices such as IM-RSEI for iron mines [263] and RE-RSEI for rare earth mines [264]; incorporating PM2.5 concentration [265] or industrial coal dust index (ICDI) [266] to reflect atmospheric pollution; adding the normalized difference built-up and soil index (NDBSI) to capture land resource changes during mining [267,268]. Furthermore, other studies have employed moving-window models to construct RSEI indicators, allowing them to consider the relationships between land cover and adjacent features [269,270]. However, the limitations of the RSEI and its derived indices are also evident. Specifically, the complex spectral characteristics inherent to mining landscapes (e.g., exposed tailing, host rocks, and dust) can significantly affect the accurate estimation of individual component indicators, thereby diminishing the overall index accuracy. Furthermore, since the RSEI primarily reflects surface features, it is insufficiently sensitive to subsurface or potential mining disturbances.

Figure 12.

Multiple indicators for monitoring ecological environment quality in mining areas.

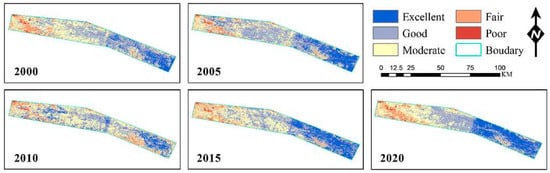

Figure 13.

Assessment of ecological environmental quality changes in the Muli coalfield from 2000 to 2020 based on the RSEI. Details in [258].

3.7. Post-Mining Reclamation Quality Assessment

Land reclamation in mining areas plays a pivotal role in achieving economic, social, and ecological sustainability [271]. It not only improves the utilization of degraded land resources but also mitigates environmental degradation and promotes the long-term recovery of ecosystem functions. Reclamation practices, including land grading, soil physical and chemical improvement, and subsequent artificial revegetation, can effectively accelerate vegetation restoration in mining-disturbed landscapes [272]. However, the inherent complexity of reclamation processes and the potential for secondary disturbances necessitate continuous post-reclamation monitoring [273]. As human intervention diminishes following reclamation project completion, vegetation degradation or ecosystem instability may occur during natural succession [274]. Therefore, post-reclamation quality assessment is essential for evaluating reclamation effectiveness, guiding adaptive management, and optimizing restoration strategies.

Traditional reclamation assessments primarily focus on ecological indicators, including soil physicochemical properties, vegetation cover, and topographic stability [275,276]. These evaluations typically rely on field surveys, which, despite their accuracy, are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and often spatially limited. Remote sensing technology provides a rapid, non-destructive, and spatially extensive alternative. By retrieving parameters such as vegetation indices (VI), land surface temperature (LST), and topographic variables from satellite imagery, remote sensing enables large-scale and continuous monitoring of reclamation performance. The availability of long-term satellite image time series further supports the evaluation of reclamation trajectories and sustainability over extended periods [277,278,279,280] (Figure 14). Since single indicators cannot capture the synergistic evolution among soil, vegetation, and environmental factors [281], integrated assessment frameworks have been developed by combining multiple remote sensing-derived indicators. These frameworks allow for the simultaneous evaluation of engineering performance, soil quality, vegetation recovery, and ecological benefits [282]. Some studies have further proposed composite indices constructed through selected representative indicators and normalization methods to represent overall reclamation quality [21,283,284,285]. Additionally, the rapid advancement of UAV-based platforms has significantly enriched post-mining monitoring approaches. For instance, UAV-LiDAR systems enable the extraction of fine-scale three-dimensional vegetation structural information [123,286,287], such as canopy height (Figure 14), proving new insights into the structural recovery of restored ecosystems. Beyond ecological restoration, recent studies have increasingly incorporated indicators related to land reuse potential, ecosystem services, and social well-being into reclamation quality assessment [288,289,290].

Figure 14.

Remote sensing-based assessment of vegetation restoration in mining areas: (a) Temporal trends in vegetation over reclaimed waste dumps based on Landsat-NDVI. Details in [280]; (b) Canopy height of different vegetation types (trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants) on reclaimed waste dumps derived from a UAV-based LiDAR system. Details in [123].

4. Discussion

The rapid advancement of remote sensing technology in recent years, coupled with the integration of multi-source datasets, diverse modeling and algorithms, and the emergence of powerful cloud-computing platforms (e.g., GEE platform), offers unprecedented opportunities for long-term, large-scale, and multi-dimensional assessment and monitoring of mining-induced eco-environmental changes. However, data quality inconsistencies, model interpretability issues, financial costs, and privacy or policy constraints continue to pose considerable challenges for their deployment in mining areas. In this section, we examine these opportunities and challenges in detail, while also proposing perspectives for future research to promote the broader application of remote sensing technologies in mining-related eco-environmental monitoring and assessment (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Opportunities and challenges of remote sensing technology in mining-related eco-environmental monitoring and assessment.

4.1. Opportunities

4.1.1. Enrichment of Remote Sensing Data Types

Remote sensing data are undergoing a rapid evolution toward greater diversity in both sensor types and spatiotemporal resolution. From optical and infrared imagery to LiDAR observations, these heterogeneous datasets have been extensively applied to monitor a variety of mining-induced environmental disturbances (e.g., vegetation, soil, terrain, thermal anomalies). The integration of multi-source data mitigates the limitations of single dataset and substantially improves monitoring accuracy and reliability. Across scales, the combined use of medium/high-resolution satellite imagery with high-resolution UAV observations has significantly broadened both the spatial and temporal scope of ecological monitoring in mining areas. While medium-resolution satellite observations (e.g., Landsat, Sentinel) are relatively coarse in spatial resolution, their long-term temporal coverage enables researchers to track multi-decadal land cover transitions [291] and reconstruct continuous trajectories of mining disturbance and reclamation [72,186]. The advancement of high-resolution remote sensing has shifted mining-area monitoring from coarse regional mapping toward fine-scale and three-dimensional structural characterization. Sub-meter satellite imagery (e.g., Gaofen) facilitates highly detailed mapping at regional scales, thereby improving the accuracy of mine/coal gangue detection [292,293], heavy metal contamination assessment [294,295], and post-mining ecological restoration monitoring [296]. At finer spatial scales, UAV-based multi-sensor platforms provide centimeter-level imagery that enables ultra-detailed monitoring. Specifically, UAV-LiDAR systems capture detailed vertical vegetation structure, which has been widely used for high-precision vegetation classification [122,123] and terrain reconstruction [120]. These UAV datasets can partially substitute for traditional ground surveys and serve as an important complement to satellite imagery, thereby reducing both labor and cost. More importantly, the synergistic integration of the high spatial resolution of UAV imagery with the high temporal frequency of satellite observations achieves an effective balance between monitoring scale and coverage [195,297].

4.1.2. Advances in Algorithms and Cloud Computing

Recent advances in modeling, algorithm, and cloud-based computing platforms have markedly enhanced both the accuracy and efficiency of eco-environmental monitoring in mining areas. Traditional remote sensing image interpretation—largely dependent on manual visual inspection or simple threshold-based classification—has long been constrained by subjectivity, high labor costs, and limited scalability. With the development of machine learning, a variety of models (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, K-Nearest Neighbors) have been applied to remote sensing imagery of mining areas, resulting in improved land cover classification accuracy. However, these algorithms typically rely on manual feature engineering and often show limited adaptability in the highly heterogeneous and noisy environments characteristic of mining areas [148,150]. Deep learning, with its powerful capability for automatic feature extraction, can learn representative features from multi-source datasets and significantly improve land cover classification accuracy in mining areas [151,298]. Deep learning has also demonstrated remarkable performance in object boundary detection tasks, such as tailing dam and mine pit detection [299,300,301,302] and mining fissure extraction [303,304]. Meanwhile, the emergence of cloud computing platforms has removed the storage and computation bottlenecks associated with large-scale spatiotemporal analysis. In particular, Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform [305] integrates continuously updated long-term remote sensing datasets, allowing users to access and process petabyte-scale imagery without local downloading or storage, which is essential for regional-to-global ecological monitoring [306]. Furthermore, interactive code editors (JavaScript/Python APIs) and a wide range of open-source cases enable researchers to rapidly learn basic operations and efficiency scale from method validation to large-scale applications.

4.1.3. Diverse Monitoring Indicators

The diversification of remote sensing data types and spatiotemporal resolutions has greatly enhanced the comprehensiveness of ecological monitoring in mining areas. Compared with earlier approaches that primarily relied on single indicators such as VIs or LST, recent assessments have increasingly adopted multi-indicator and integrated approaches. By combining multiple remote sensing datasets, diverse ecological parameters—such as vegetation greenness, soil moisture, and thermal anomalies—can be rapidly derived to support a multidimensional evaluation of mining-induced disturbances. These parameters can be further synthesized into composite indices using techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA), normalization, and ratio-based method, thereby improving the discrimination between degradation and restoration processes and enabling a more comprehensive understanding of ecosystem responses to mining [21,285]. Moreover, the availability of high-resolution and diverse imagery facilitates the retrieval of finer-scale ecological attributes, including canopy height and biomass in addition to vegetation cover or greenness [286], thereby enhancing both the completeness and interpretability of ecological assessments.

4.1.4. Complete Management and Decision Support

The rapid advancement of remote sensing platforms has enabled the establishment of an integrated satellite–UAV–ground monitoring framework for eco-environment assessment in mining areas [307,308]. Supported by cloud-based processing and analysis, the integration of long-term satellite observations with trend analysis algorithms enables continuous, pixel-level monitoring of mining-induced disturbances—from the initial occurrence of vegetation degradation and thermal anomalies to the quantification of disturbance intensity and the prediction of future trajectories. During critical periods, fine-scale UAV observations and ground surveys can be integrated with remote sensing-derived indicators and process-based models to enhance the accuracy of early warning. Moreover, remote sensing monitoring increasingly serves as a foundation for policy decision-making related to post-mining ecological compensation, reclamation effectiveness, and ecological risk early warning, by providing quantitative and spatially explicit evidence. For instance, long-term satellite observations have revealed that coal waste dumps after reclamation may experience secondary ecological degradation under extreme climatic conditions during natural restoration, raising concerns about the adequacy of current reclamation management schedules and practices [274]. UAV-based assessments in mining areas with high groundwater table have further demonstrated that the radius of vegetation degradation in subsidence farmland may exceed the traditional 10 mm subsidence threshold used for compensation evaluations, suggesting the necessity to refine existing policy criteria [103]. Similarly, remote sensing technology has been applied to identify spontaneous combustion sources in coal waste dumps and to predict the spatial evolution of associated fire hazards, thereby supporting ecological risk management [247,309]. Collectively, these advances illustrate the transition of remote sensing from an effective monitoring tool into an essential component of evidence-based ecological governance in mining areas.

4.2. Challenges

4.2.1. Image Quality and Accessibility

Despite the substantial increase in the diversity of remote sensing datasets, inconsistencies in data quality, temporal coverage, and accessibility continue to constrain eco-environmental monitoring in mining areas. Mines are often located in remote regions, where optical imagery is frequently affected by cloud cover and atmospheric aerosols, limiting the availability of high-quality observations, particularly in tropical regions [310]. Although satellite dataset (e.g., Landsat, MODIS) provide extensive temporal coverage, their coarse spatial resolution restricts the detection of small-scale mining-induced disturbances. Conversely, high-resolution satellite imagery (e.g., Worldview, Gaofen) provides detailed spatial information but remains limited in widespread application due to high acquisition costs and access restrictions. Consequently, several studies are constrained to site-specific analyses or short-term observation windows, thus hindering continuous monitoring over broader spatial and temporal scales. While UAV platforms are highly flexible and can capture fine-scale information, their monitoring capacity is often constrained by payload limitations, flight endurance, meteorological conditions, and airspace regulations [311], leading predominantly to one-off or short-duration observations. Expanding open access to high-resolution satellite data, coupled with advances in multi-source data fusion, will be essential for improving the continuity and reliability of eco-environmental monitoring in future.

4.2.2. Uncertainty of Models and Indicators

Recent advances in machine learning and deep learning have considerably improved the accuracy of remote-sensing-based monitoring and expanded its applicability to complex mining environments. Nevertheless, the stability and generalization of these models remain constrained by several factors. These approaches typically require high-quality and representative training samples, and their predictive performance can be highly sensitive to sample selection, potentially introducing feature-selection bias. Given the pronounced spatial heterogeneity of mining-induced ecological disturbances, models trained in specific region may not generate reliably when transferred to other areas. For example, ref. [312] reported that the integration of radar and multispectral datasets did not consistently enhance segmentation accuracy in mining areas, and the inclusion of additional features may sometimes reduce performance due to overfitting. Similarly, ref. [313] found that the performance of U-Net models may deteriorate under complex surface conditions characteristic of mining landscapes. Moreover, remote sensing–derived vegetation indices are not always transferable across varying spectral backgrounds [314]. In arid and semi-arid mining regions, for instance, inherently low vegetation cover results in persistently low NDVI values, rendering NDVI-derived trends insufficient for capturing mining-induced disturbances [21]. As models and datasets continue to evolve toward higher spatial and spectral resolutions, both computational costs and the risk of overfitting are likely to increase. Enhancing model interpretability and improving cross-scenario transferability will therefore be essential directions for future research.

4.2.3. Complex Mechanisms of Mining Disturbance

Remote sensing indicators, such as vegetation indices and land surface temperature, enable the rapid monitoring and indirect characterization of vegetation stress, soil degradation, water disturbances, and thermal anomalies. Nevertheless, remote sensing inherently provides a predominantly surface-level perspective, while mining-induced disturbances frequently originate from tightly coupled surface-subsurface interactions. This fundamental observation mismatch often limits the mechanistic interpretation of complex eco-environmental degradation processes. For instance, vegetation-based monitoring models (where remote sensing offer clear advantages) capture vegetation differences, indirectly identifying underground spontaneous combustion processes of coal waste dumps [247,309], assessing land damage of subsidence farmland [103], or estimating post-reclamation soil quality [198,315,316]. Although these methods achieve promising monitoring results, they provide limited explanatory power regarding the physical or biogeochemical pathways driving these disturbances. The integration of remote sensing with in situ monitoring data (e.g., subsurface temperature, soil properties, groundwater chemistry) can provide more robust constraints on subsurface conditions and significantly improve interpretation accuracy. Also, the multidisciplinary integration (e.g., geophysics, hydrogeology, thermal geology) is particularly important given the substantial spatial and operational variability inherent to the mining sector, including diverse mining types, extraction depths, orebody structures, and operational methods. Collectively, these factors influence disturbance intensity and spatial footprint and, consequently, limit the transferability of remote sensing-based models. Therefore, advancing toward integrated surface–subsurface observation systems and coupled modeling approaches will be essential for achieving deeper mechanistic insights and improving predictive assessment of mining-induced ecological degradation, even when accounting for the technical challenges involved.

4.2.4. Costs and Policy Constraints

High data acquisition and computational costs also limit the large-scale engineering application of remote sensing for mining-related eco-environmental monitoring. Ecological disturbances in mining areas often exhibit pronounced spatial heterogeneity and fine-scale structural variation, necessitating high-resolution satellite imagery or UAV-LiDAR system. Such observations involve substantial acquisition expenses and are challenging to sustain over long-term monitoring campaigns. Moreover, multi-source data fusion and the training or deployment of deep learning models require considerable computational resources and storage capacity, creating a substantial gap between model development and real-world deployment. Policy and regulatory constraints further compound these challenges. UAV-based monitoring is frequently limited by airspace regulations and flight permissions in many regions, while high-resolution satellite imagery may be subject to national security restrictions that limit spatial resolution or access. Additionally, enterprise-level disturbance data are often treated as confidential, preventing the integration of remote-sensing observations with regulatory oversight and ecological restoration planning.

4.3. Future Perspectives

High-resolution, multi-modal remote sensing imagery, together with artificial intelligence-driven algorithms and models, presents significant opportunities for monitoring mining-related eco-environmental changes. Future research should further develop applicable indicators for different mining types and landscape types to enhance their transferability across diverse environments. At the same time, strengthening multi-source data integration is critical, specifically by combining remote sensing with geophysical measurements (e.g., electrical resistivity and magnetics), hydrogeological observations (e.g., groundwater level and quality), and in situ monitoring (e.g., soil properties, temperature, topography). This combined approach is necessary to improve the coupling between surface and subsurface disturbances and to provide deeper insight into disturbance mechanisms. In addition, the adoption of explainable artificial intelligence techniques can further enhance model generalization and accuracy across different mining types, climatic zones, and geological conditions. Finally, integrating multi-spatial- and multi-temporal-resolution remote sensing data within a satellite–UAV–ground monitoring framework will facilitate historical analysis, real-time monitoring, and dynamic tracking of disturbances throughout the full mining life cycle. Low- and medium-resolution satellite data can support long-term continuous observations and rapid detection of disturbance at regional to global scales, whereas high-resolution satellite imagery, UAV observations, and ground-based measurements provide detailed surface change and structural information for precise disturbance identification and validation. Further advances in spatiotemporal resampling, cross-sensor radiometric harmonization, and the establishment of unified reference baselines linking observations across specific regions are expected to be key directions for improving the stability and transferability of monitoring outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This review examines the application of remote sensing technology in mining-related eco-environmental monitoring and assessment. By comprehensively reviewing recent advances, we outline the major eco-environmental issues associated with mining activities, summarize commonly used remote sensing platforms and data types, and highlight the advance of remote sensing monitoring in key aspects, including the spatiotemporal dynamics of land-use and land cover, terrain survey and deformation, natural environmental factor disturbance, comprehensive assessment of ecological environment quality, and post-mining reclamation quality assessment. The increasing accessibility of high-resolution, multi-modal remote sensing imagery has enabled monitoring across the full mining life cycle. Nevertheless, current monitoring efforts continue to face several challenges, including limitations in data quality and accessibility, difficulties in characterizing complex subsurface disturbance mechanisms, the limited transferability of monitoring indicators and models, as well as cost and policy constraints. Looking forward, systematically linking mining-induced multidimensional eco-environmental disturbances with corresponding remote sensing monitoring tasks, together with the integration of multi-resolution and multi-modal remote sensing data, coordinated surface and subsurface observations, and the development of explainable artificial intelligence models and algorithms, is expected to provide stronger support for improving the efficiency and reliability of remote sensing-based eco-environmental monitoring in mining areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.R. and Y.Z.; methodology, H.R.; software, H.R.; validation, H.R., Y.Z., and T.H.; formal analysis, H.R.; investigation, H.R.; resources, Y.Z.; data curation, H.R.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and T.H.; visualization, H.R.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, H.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant No. 42507624].

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, Y.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Xia, Q. Developments in quantitative assessment and modeling of mineral resource potential: An overview. Nat. Resour. Res. 2022, 31, 1825–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Mohsin, M. Role of mineral resources trade in renewable energy development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 181, 113321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L. Towards sustainability in mineral resources. Ore Geol. Rev. 2023, 160, 105600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mervine, E.M.; Valenta, R.K.; Paterson, J.S.; Mudd, G.M.; Werner, T.T.; Nursamsi, I.; Sonter, L.J. Biomass carbon emissions from nickel mining have significant implications for climate action. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, G.; Valero, A. Strategic mineral resources: Availability and future estimations for the renewable energy sector. Environ. Dev. 2022, 41, 100640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shahbaz, M.; Dong, K.; Dong, X. Renewable energy transition in global carbon mitigation: Does the use of metallic minerals matter? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 181, 113320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedrago, A. Local economic impact of boom and bust in mineral resource extraction in the United States: A spatial econometrics analysis. Resour. Policy 2016, 50, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xiong, W. Research on diversity of mineral resources carrying capacity in Chinese mining cities. Resour. Policy 2016, 47, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajkowicz, S.A.; Heyenga, S.; Moffat, K. The relationship between mining and socio-economic well being in Australia’s regions. Resour. Policy 2011, 36, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henckens, T. Scarce mineral resources: Extraction, consumption and limits of sustainability. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169, 105511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, S.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. How does green finance affect the sustainability of mineral resources? Evidence from developing countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 475, 143620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainguy, C. Natural resources and development: The gold sector in Mali. Resour. Policy 2011, 475, 143620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rawashdeh, R.; Maxwell, P. Jordan, minerals extraction and the resource curse. Resour. Policy 2013, 38, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://minerals.org.au/resources/mining-delivers-record-455-billion-in-export-revenue-in-fy23/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/chile-mining (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- IEA. Introducing the Critical Minerals Policy Tracker; IEA: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/introducing-the-critical-minerals-policy-tracker,Licence:CCBY4.0 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Riva Sanseverino, E.; Luu, L.Q. Critical raw materials and supply chain disruption in the energy transition. Energies 2022, 15, 5992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, W.; Bai, Z. Vegetation coverage change and stability in large open-pit coal mine dumps in China during 1990–2015. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 95, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Guo, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Ran, W.; Hu, J.; Mao, H. Automatically identifying the vegetation destruction and restoration of various open-pit mines utilizing remotely sensed images: Auto-VDR. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Wu, J.; He, C.; Fang, X. The speed, scale, and environmental and economic impacts of surface coal mining in the Mongolian Plateau. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 173, 105730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Zhang, M.; Guo, A.; Zhai, G.; Wu, C.; Xiao, W. A novel index combining temperature and vegetation conditions for monitoring surface mining disturbance using Landsat time series. Catena 2023, 229, 107235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Yan, K.; Guan, Y.; Wang, J. Identification of the disturbed range of coal mining activities: A new land surface phenology perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 143, 109375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhou, Y.; Jia, S.; Shao, H.; Liu, M.; Tao, S.; Dai, X. Impacts of mining on vegetation phenology and sensitivity assessment of spectral vegetation indices to mining activities in arid/semi-arid areas. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 356, 120678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Yuan, L.; Liu, M.; Liang, S.; Li, D.; Liu, L. Quantitative estimation for the impact of mining activities on vegetation phenology and identifying its controlling factors from Sentinel-2 time series. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 111, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, P.; Zhu, X. Quantification of vegetation phenological disturbance characteristics in open-pit coal mines of arid and semi-arid regions using harmonized Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, B.; Agrawal, M.; Singh, S. Coal mining activities change plant community structure due to air pollution and soil degradation. Ecotoxicology 2014, 23, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Liu, S.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, S.; Su, X.; Liu, G. Vegetation community composition along disturbance gradients of four typical open-pit mines in Yunnan Province of southwest China. Land. Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Wang, G.; Shi, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.; Jin, X. Impact of mining activities on groundwater level, hydrochemistry, and aquifer parameters in a Coalfield’s overburden aquifer. Mine Water Environ. 2022, 41, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, W.; Wang, Q. Prediction and zoning of the impact of underground coal mining on groundwater resources. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 168, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Zhang, D.; Honglin, L.; Hongzhi, W.; Yazhou, Z.; Shuai, Z.; Wei, Y.; Shuaishuai, L.; Qiang, Z. Simulation analysis of water resource damage feature and development degree of mining-induced fracture at ecologically fragile mining area. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, T.; Wen, X.; Ma, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, H. Analysis of Surface Runoff and Ponding Infiltration Patterns Induced by Underground Block Caving Mining—A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyamfi, E.; Appiah-Adjei, E.K.; Adjei, K.A. Potential heavy metal pollution of soil and water resources from artisanal mining in Kokoteasua, Ghana. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, K.O.; Shane, A.; Syampungani, S. Aquatic ecological risk of heavy-metal pollution associated with degraded mining landscapes of the Southern Africa River Basins: A review. Minerals 2022, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, A.; Chowdhury, A.; Mishra, B.K.; Gupta, S.K. Metal pollution in water environment and the associated human health risk from drinking water: A case study of Sukinda chromite mine, India. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2016, 22, 1433–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, W.; Wang, J.; Yu, Q.; Du, Z. Soil quality of surface reclaimed farmland in large open-cast mining area of Shanxi Province. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2013, 223, 2422–2428. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Cao, Y.; Pietrzykowski, M.; Zhou, W.; Zhao, Z.; Bai, Z. Spatial distribution of soil bulk density and its relationship with slope and vegetation allocation model in rehabilitation of dumping site in loess open-pit mine area. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]