Abstract

It is broadly agreed that development needs and effects from changing environment will increase pressure on the ways natural resources are utilized and shared at present. In most parts of the world, resource stress has already reached unprecedented levels setting resource sustainability high on the policy agenda on multiple governance levels. This paper aims to explain how the benefit sharing approach can help reframe the debate for sustainability, its advantages and disadvantages for transforming governance challenges and adapting to increasing resource stress. We bring together fragmented discussions of benefit sharing from three resource domains: water, land, and biodiversity. Both theoretical and empirical examples are provided to aid understanding of how benefit sharing can facilitate adaptive governance processes in complex socio-ecological systems. The findings highlight importance of integrating the long-term perspective when societies move from volumes toward values of shared natural resources, as well as setting environmental conservation and equitable allocation as the top priority for benefit sharing to be sustainable.

1. Introduction

Shared natural resources such as water, land, and biodiversity are complex natural resources, sustainable management of which often requires collaboration beyond boundaries of any single nation, as well as on multiple levels within individual states and across sectors. The recent decades have seen a significant growth of collaborative treaties signed with the purpose to protect global environmental resources and increasing number of countries joining these treaties (see for instance, the International Environmental Agreements Database Project of the University of Oregon [1]). At the same time, scholars have increasingly emphasized that global level cannot be the starting point in shifting to more sustainable pathways in human–environment interaction, and that much “has to start from the ground up and be carried out simultaneously at all levels” from local to international ([2] p. 9; also see [3]). In any case, despite the growing efforts and overall attention, there is a common recognition that due to development needs of societies and effects from changing environmental conditions (particularly climate), the stress mounted on shared natural resources is reaching unprecedented high levels [4]. Examples include depletion and pollution of freshwater resources [5], degradation of land resources and deforestation [6], extinction of species [7], and links of these patterns to increased frequency and intensity of recorded natural disasters [8], while projections for the business as usual scenarios of resource use and governance are far from optimistic (e.g., [9]). Against this background, this paper explores ways of collaborative governance with shared benefits that can facilitate adaptation toward sustainability of shared natural resources.

Reframing the debate from competing interests and conflict into benefit sharing and cooperation has been increasingly suggested within various contexts of environmental governance (e.g., [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]). The idea of such a reframing is to focus on benefits derivable from use and allocation of shared natural resources rather than on their quantities. While focusing on resource quantity results in a zero-sum game, where one’s gain is another’s loss, focusing on benefits opens up a wide range of additional options where win-win becomes possible. Scholars argue that, by redirecting the focus, societies can continuously adapt to newly emerging challenges related to resource scarcity while ensuring the sustainability of the resource itself (e.g., [11]). Mechanisms of benefit sharing such as compensations (financial and in kind) and issue linkages (whereby total benefits can be increased by connecting trade-offs on different issues or different sectors) are said to help find innovative solutions (e.g., [19]). However, the use of the term “benefit sharing” and its explanation have been largely sporadic and fragmented across various sectors of environmental governance and research disciplines. While benefit sharing as a method has been increasingly applied to help transform transboundary water disagreements, the term itself has been most prominently coined within the 2010 Nagoya Protocol to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), where the emphasis is on the fair and equitable sharing of benefits rather than achieving win-win [20]. In this respect, the normative basis of the concept has also been linked with the international human rights law [21,22]. More recently, the approach has been suggested to move toward “win-win” solutions within the resource domain of land, too [23]. The origins of the concept can be traced back to the earlier game theoretic concepts such as Pareto improvement, as well as the negotiation research of the 1980s [24].

Within this paper, we present results of our exploratory research based on major observable trends available in the existing literature related to benefit sharing. Our guiding questions throughout the study have been: (1) whether the concept of benefit sharing indeed helps to facilitate cooperative processes; and (2) whether such cooperative processes induced by the benefit sharing approach are likely to lead to overall sustainability. While answering these questions, the purpose of the paper is twofold. First, we want to initiate a streamlined discussion of the theoretical debate across disciplines and sectors in relation to applicability of benefit sharing to managing shared natural resources (Section 2 and Section 4). Second, we want to illustrate various characteristics of the concept with examples from the three resource domains that are increasingly under stress globally: water, biodiversity, and land (Section 3). In Section 4, we reflect on our findings in relation to the two guiding questions, and discuss strengths of the concept, its individual mechanisms and lessons learned from the existing experience to understand the transformative power of benefit sharing in adapting to ever changing circumstances. We summarize our suggestions for further research (Section 4) before drawing main conclusions in the final section (Section 5).

2. Reframing, Sustainability, and Benefit Sharing

The discourse on conflict and cooperation over natural resources has been continuously reframed over the last several decades. Malthusian discussions in the 1960s and early 1970s set the tone that there were limits to growth due to finite capacities of the natural resources to meet the growing food and development needs of societies [25]. However, already back then, Boserup [26], in the example of agricultural growth, emphasized that it was rather important to focus on how societies could foresee the scarcity and adapt to these scarcities. In the 1980s, the novelty of the Brundtland Commission [27], which changed how we understand human–environment interaction till present, was that the focus of the debate was reframed from “human versus the environment” to “human and the environment” by introducing the sustainability concept. Realist theorists in the early 1990s, however, predicted more frequent and more intense conflicts due to natural resource scarcity; in particular, several authors warned about water becoming a source of wars in the 21st century (e.g., [28,29,30]).

In parallel, there have been empirical studies, which by the late 1990s showed that historically, cooperation over natural resources had been far more common than conflict (e.g., [31,32,33]). Reframed focus in the 1990s has led to growth in the literature with rather optimistic and solution-oriented views aimed at transforming conflicting interests over natural resources into opportunities to foster cooperation. Finally, a significant contribution has been made by scholars reiterating the complexity of the larger scale natural resource management systems, and highlighting diversity within and co-existence of conflict and cooperation [34,35,36,37,38,39]. While the focus differed within the above approaches, all of them share one important feature, that is, recognition of the necessity to enhance and maintain cooperative actions over shared natural resources.

In the 2000s, at least two parallel developments can be observed that led to the establishment and refinement of the present day “benefit sharing” terminology. First, within the context of transboundary water management, benefit sharing has been suggested and promoted as a new way to seek cooperation between countries with competing interests by development-oriented agencies such as the World Bank, Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs, and Overseas Development Institute (e.g., [11,15,16,40]). The suggested concept has been picked up by a number of scholars, who developed models for different transboundary river basins around the world (e.g., [41,42,43,44]), and by donor community and basin management organizations, who actively promoted the approach in negotiations to foster cooperation between riparian states (e.g., [45,46,47]). Second, the conference of parties to the Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD) took active steps to establish a new international regime on access to genetic resources and benefit sharing (ABS), which resulted in adoption of the Nagoya Protocol in 2010 [20,48].

In addition to the above two, there is also a relatively younger initiative within the resource domain of land. It is the “global call to action”, a campaign led by the Rights and Resources Initiative, International Land Coalition, and Oxfam along their multiple partners to support the communal land rights of indigenous communities [49]. The campaign calls for win-win solutions doubling the land area legally recognized as owned or controlled by indigenous communities by 2020. The purpose is to ensure that benefits from investments in land use and development are shared with those who historically and traditionally have resided on and used these lands.

2.1. Many Faces of Benefit Sharing

As noted, the idea of benefit sharing is to focus on potential benefits of shared natural resources that can be achieved through cooperation rather than on their limited quantities (e.g., [50]). Assuming status quo allocation is contested or reallocation is needed for coping with natural resource stress, the benefit sharing approach transforms the main question of reallocation from “who gets what” to “how to improve it for all”, and therefore attempts to circumvent the very conflict of the main reallocation question (Table 1).

Table 1.

How benefit sharing approach transforms the main question of allocation.

Essentially, the benefit sharing approach aims to enrich the pool that can be shared—enlarging the pie itself—to tackle the challenges of negotiations over and implementation of agreements on shared natural resources. The main criticism of the benefit sharing approach has been that although it might augment the total benefits through cooperation, it does not solve the distributional dilemma, when the increased benefits will have to be shared (e.g., [51,52,53]). However, Wolf [54], for example, argues that historical and existing cooperative experience helps to build confidence in achieving cooperation in new areas. Along similar lines of argument, Sadoff and Grey [11] state that among the advantages of the benefit sharing approach is that benefits from cooperation can be not only economic but also environmental, social, and political. From governance perspective, Nkhata et al. [18] propose to distinguish among the following three types of benefit sharing: (a) co-management, where focus is on the relationships between state actors and local communities in the allocation of benefits from ecosystem services; (b) market-oriented, which uses economic instruments and involves voluntary exchange of mutually beneficial favors; and (c) egalitarian that focuses on making the sharing equitable. The typologies show how benefit sharing can be framed with differing emphasis. We aim to extend this framework by investigating the implications from this varying emphasis on overall sustainability of the systems.

Further, a closer look into the idea of benefit sharing reveals that it resembles a number of other concepts from various disciplines. First, it replicates the idea of the broadly used win-win concept (e.g., [55]). Within this concept, the main negotiation strategies are distributive and integrative. A distributive strategy may lead to win-lose, lose-win or lose-lose situations. In the integrative strategy, the purpose is to augment the total gains. Negotiation partners try to reach an agreement that fulfills the needs of all parties leading to a win-win strategy [56]. In terms of application, benefit sharing also replicates the “mutual gains” approach known within the Harvard negotiation research since 1980s [24], which likewise focuses on achieving mutually beneficial deals between negotiating parties. The origins of the positive sum could be traced back to game theoretical concepts such as Pareto improvement, where in an interaction with a set of players, utility is improved at least for one player without making any other player worse-off.

2.2. Mechanisms of Benefit Sharing and Continuum of Complexity

As noted, one of the major advantages of the benefit sharing approach is that it offers a wide range of mechanisms enabling implementation of arrangements with shared benefits [19]. These include:

- financial compensation: monetary compensation that occurs one time or for a specified period, for example, payment for resettlement due to infrastructure development or conservation project;

- in kind compensation: non-monetary compensation that occurs one time or for a specified period, for example, provision of land and housing for resettlement;

- issue linkages within a single issue area (or within a single sector): for example, when negotiations are held on two transboundary river basins (i.e., the same issue area) to allow mutual gains for riparian parties; hence, issue linkages can be seen as a type of mutual compensation, fundamental difference being that commitments are recurring (for example, annual payments) and the issues are linked for an indefinite period; and

- issue linkages across multiple issue areas (or sectors): for example, where agreements are reached by connecting trade-offs within one sector, for instance forestry, with other sectors, for instance energy or trade.

From complexity point of view, the above ordering of the mechanisms might also reflect their positioning along the continuum from less to more complex mechanisms of benefit sharing. It is assumed that an in-kind compensation, holding all else equal, is slightly more complex than a monetary compensation as the complexity increases with the number of issues at hand. In general, and contrary to some existing literature [19], we argue that a mere monetary or even an in kind compensation of the market value should not suffice to qualify as benefit sharing. To qualify as benefit sharing it is reasonable that the added value, that is, the increased benefits because of cooperation, is shared as well. For example, in return for giving up land rights local communities should receive a share of benefits from the surplus of the yield and not just compensation for a loss of land.

Issue linkages, where issues are essentially merged, for example, when a new department is created to implement new arrangements linking two river basins, clearly represent the next level of complexity requiring considerably more—perhaps a lifelong—coordination and adaptive learning [57]. This complexity certainly amplifies when the linkages require cross-disciplinary coordination and learning [39].

2.3. Lifecycle of Benefit Sharing

The above indicates that, in order for benefit sharing to be successful in complex natural resource systems, reframing requires fundamental transformations that are continuous on many levels (see also [2]). This includes changes in perceptions highlighting the importance of total benefits or collective welfare, especially in complex resource systems under stress, where resource use is directly linked to sustaining livelihoods. The attitude toward resource use will have to transform from “divide and rule” to “cooperate and share” that should open up more options for possible linkages across sectors and disciplines allowing a positive sum. Finally, considerable societal learning and broader structural changes will be required to realize the actual changes with shared benefits. For example, in case of issue linkages in the water domain, actors in one river basin might need to learn how to take into account the circumstances in another river basin to implement agreements connecting the two different rivers. When it is an inter-sectoral issue linkage, for instance, actors in the forestry sector might need to understand how their decisions can lead to improved collective welfare when considered in conjunction with the energy sector. Implementation of agreed terms might require reevaluation and structural changes in existing institutions—formal and informal rules—governing the interactions within a given natural resource system. In addition, in line with path dependency theory, although the first transformation might be challenging, once “cooperate and share” brings its fruits and becomes a familiar mental model [58,59,60], one benefit sharing round might be followed by another, starting cyclical adaptive governance processes in complex socio-ecological systems.

Hence, a holistic analysis should include all phases of the process that is necessary for benefit sharing. Similar to regime analysis (e.g., [61,62]), for analytical purposes, we propose to distinguish among the following important phases in the lifecycle of benefit sharing (note that we distinguish among these phases for analytical purposes only, bearing in mind considerable overlaps and feedbacks between and among them in practice):

- Agenda setting: Here we aim to understand how the idea of benefit sharing within a particular resource domain “…initially makes its way onto the international political agenda, is formed for purposes of consideration in international forums, and rises to a sufficiently prominent place on the international agenda to justify the expenditure of time and political capital required to move it to the negotiation stage” ([61] p. 11). Analysts usually argue that power, interests, and ideas or combination thereof can influence framing of the problem in environmental regimes (e.g., [61]). While political, economic, and military potential of states is associated with the power aspect [63,64], the interests-based approach focuses on incentives to cooperate [65,66]. The epistemic communities such as academia, think tanks, but also nongovernmental organizations (especially when existing sharing is not equitable), and development agencies might help bring the issue to the table by initiating talks, proposing innovative solutions, calculating options, publishing articles with models, acting as watchdogs, and reporting best practices (e.g., [67]).

- Negotiations: Parties competing for shared natural resources, if necessary with the help of mediating organizations, reveal their positions in relation to the issues set in the agenda, and negotiate over the terms of possible new arrangements. Here, it is important to note that as we in this paper explore the emerging trends of benefit sharing in rather conceptual terms, our particular focus is on identifying some key conceptual negotiating positions that represent a conflicting situation to be transformed into benefit sharing. The purpose here is to understand whether and how benefit sharing can shift the focus from positions to interests in different contexts [15,24].

- Operationalization: The aim here is to understand how parties move from the more general idea-level agreement that benefits from the use of shared natural resources can be increased through collaboration, and should be shared among affected actors to actual processes of implementation. Operationalization includes processes where actors discuss details and agree on terms of concrete projects and arrangements rather than general principles, implement agreed terms, reorganize themselves, reevaluate and adjust institutions, create and modify organizations, assign responsibilities among actors, achieve the agreed targets, and share the surplus of benefits that results from cooperative actions. Here, it is also important how exactly operationalization is defined: only signed on paper (perhaps, even deliberately) that remains as so-called “paper tigers” [68] or when the agreement is enforced and actually implemented.

- Evaluation and adaptation: At this phase parties reevaluate the problem structure, negotiation positions, terms of agreement, and implementation effectiveness, and return to new agenda setting to define a new or adjusted problem structure [69]. For benefit sharing analysis, it will be important here to understand whether and how learning effects from benefit sharing [57] might reinforce an institutional environment for cooperative and adaptive governance.

3. Emerging Trends of Benefit Sharing: Water, Biodiversity, and Land

The following three subsections will detail emerging trends relevant to applicability of benefit sharing across three resource domains. First, we look at the trends in the global discourse of how the approach is suggested to transform transboundary water disagreements, and provide an illustrative theoretical example originating from the Nile Basin Initiative. Second, we discuss the advances of benefit sharing in biodiversity conservation, followed by an illustration of practical details from the Tubbataha Reefs in the Philippines. Third, we review newly emerging trends of benefit sharing related to land, first in the global context, then with an example from Uganda. To highlight relevant developments within each resource domain, we structure the discussion, to the extent possible, according to the above-described lifecycle of benefit sharing; however, due to the lack of data on the evaluation and adaptation phase, the analysis describes the agenda setting, some key arguments in negotiations, and operationalization. The illustrative examples are then provided at the end of the subsections to facilitate understanding of various more typical characteristics of benefit sharing within these trends.

3.1. Benefit Sharing to Transform Transboundary Water Disagreements

3.1.1. Agenda Setting to Transform Transboundary Water Disagreements

The solution-oriented views of the 2000s, as discussed in Section 2, resulted in re-invention of the benefit sharing approach promoting its application in transboundary water management. Sadoff and Grey ([11] p. 3) proposed a broad definition of benefit sharing as “any action designed to change allocation of costs and benefits associated with cooperation”, whereby facilitation of cooperation (with shared benefits on a spectrum of benefits) is implicitly defined as an ultimate outcome. Analyzing the earlier “mutual gains” approach, Sewell and Utton ([70] p. 201) contrasted mutually gainful cooperation with “a great deal to lose from intransigence” on the examples of United States—Canadian water disputes [71]. They stated that focusing on rights prevented from mutually beneficial cooperation and that “some major changes in attitude, accompanied by modifications in institutions” were needed for cooperation to be facilitated. A number of international conferences boosted the discussions of benefit sharing in the water sector in the 2000s: the 2001 International Conference on Freshwater in Bonn, the 3rd World Water Forum and Ministerial Conference of 2003, and the 2005 Stockholm World Water Symposium. The 1990s saw development of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Non-navigable Uses of International Watercourses, subsequently adopted in 1997, and entered into force in 2014 [72,73]. The 1997 UN Convention mentions mutual benefit only in general terms under Articles 5 and 8 and rather emphasizes the importance of equitable and reasonable utilization and cooperation. Phillips et al. ([13] p. 29) note that discussions at these high-level meetings were rather superficial and there was “… little substance … discernible beyond the catch-phrase level”. However, one can argue that these meetings did in fact help set the new agenda in transboundary water regimes. Soon after the criticism, review of practical aspects on how to apply the approach to the real-world cases followed (e.g., [16,19,74]).

Further, to promote the idea, researchers reported that historically the idea of the approach (although not explicitly called benefit sharing) helped find mutually beneficial solutions among riparian states in a number of shared water basins around the world. Thus, cases, historically seen as cooperative in broad terms were reframed as cases of benefit sharing. Such reframing included the 1961 Columbia River Treaty (referred to as a successful example by many authors including Sewell and Utton [70]), where the US succeeded to negotiate changes in Canada’s hydropower projects. The US would benefit from flood control while Canada would receive payments and additional rights for diversions between the Columbia and Kootenai for hydropower [75]. The Columbia River is not the only example of such reframing; multiple examples from other parts of the world are discussed by a number of scholars [16,19,74]. As mentioned earlier, some of the development agencies (e.g., [11,13,14,15,16,40,41,42,76]) adopted the approach, and increasingly promoted it as a way forward in many contentious transboundary river basins around the world, including the Nile, Tigris and Euphrates, Ganges, Mekong, Amu Darya, and Syr Darya Basins, among others.

3.1.2. Negotiations to Transform Transboundary Water Disagreements: Some Key Arguments

Negotiations within the transboundary water regimes often revolve around two main principles of international water law: “equitable and reasonable use” and “no significant harm”—first established in the 1966 Helsinki Rules, and most recently codified within the 1997 UN Watercourse Convention. Generally, it is referred to “equitable and reasonable use” when a riparian state contests the status quo allocation and demands a reallocation. At the same time, it is often referred to “no significant harm” when a riparian state insists on maintaining the status quo claiming reallocation would harm historical users [72,73]. Global debate of benefit sharing within the transboundary water cooperation and conflict discourse concentrates on whether benefit sharing can help avoid the conflict between the two principles. A number of studies [51,52,53,69] have emphasized that when focus is on benefits some cost categories tend to be overlooked. Such costs include costs to the environment, transaction costs, costs related to equitable sharing, and political costs when a riparian party with a more favorable position might take advantage of the weaker one. For example, developments related to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) are seen by some hydro-hegemony theorists [77] as a success that should result in a more balanced sharing of the benefits. However, Tawfik ([78] p. 574) concludes that “[n]egotiations over the GERD have not transformed the debate in the Eastern Nile from sharing water to sharing benefits. Nationalistic discourse used by the three governments, the political sensitivity of the Nile issue, cautious Egyptian approach towards Eastern Nile cooperation beyond the project, divisions within policy circles in Egypt on dealing with the project and with the [Nile Basin Initiative] as a framework of cooperation, the failure of Egypt to adapt its water policies to expected changes in the post-GERD era, and the new power asymmetries in the Eastern Nile have affected, and will continue to affect, positions in ongoing negotiations, making it more difficult to reach a benefit-sharing deal”. However, this is not surprising given how recently the idea of benefit sharing started to evolve more holistically. Within the Nile Basin in particular, one may argue, that the discussions on benefit sharing per se, which recently also reached some popular outlets (see, for example, the video “Vision or Reality—Benefit Sharing in the Eastern Nile Basin” [79]), have affected how GERD was presented by Ethiopia. The idea of benefit sharing might have in fact affected the transformation (that the construction of the long-disputed GERD has finally commenced) by highlighting that benefits in the Eastern Nile should be shared.

These problems are in line with the earlier considerations regarding the rights versus benefits in transboundary water law. Sadoff and Grey [11] suggested the benefit sharing concept to resolve transboundary water disagreements. They acknowledge the fundamental principles of international water law—equitable and reasonable use. However, they proposed the benefit sharing approach as an alternative where the focus on benefits is to help avoid conflicts over rights. Dombrowsky [50], who analyzed conditions related to property rights to see whether benefit sharing can cope with the challenges of international water law, disproved it as an alternative approach showing that underlying property rights will have to be addressed if mutual benefits to be achieved, and suggested that the approach could be rather complementary in certain cases. However, Dombrowsky [50] analyzes hypothetical examples and only property rights within those hypothetical examples, and there is still little research on a broader set of institutions affecting benefit sharing. In addition to the unresolved issue of equitable and reasonable sharing between riparian states, there is still not enough research on long-term implications of sharing of the benefits from developments with local populations, and how they can be integrated in interstate negotiations [80].

3.1.3. Operationalization to Transform Transboundary Water Disagreements

In the last two decades, benefit sharing has considerably evolved from being a catch phrase into a tested negotiating approach in the water sector. This development is also largely due to the pioneering work of Phillips et al. [13] in the Nile Basin (for a summary of contributions by David Phillips and colleagues to development of the benefit sharing framework see also McCaffrey et al. [76]). They developed the Transboundary Water Opportunities (TWO) tool [15] to help facilitate issue linkages among the Nile Basin riparian states, as well as across different sectors. Earlier works of Ohlsson and Turton [81] and Molle [82] pointed out that due to the development needs and changing environmental conditions societies will have to move first, toward gaining “more water”, then to “more use per drop”, and finally to “more value per drop”, creating similar trajectories of development across river basins. Thus, the three stages of focus in the human–water interaction have been characterized as “volume”, “efficiency”, and “value”. Phillips et al. [15] share a similar vision but as the third stage, in the context where interaction is transboundary, they consider Allan’s [83,84] “virtual water” concept, which similarly emphasizes embedded value of water in traded food and commodities (see also [85]). What Phillips et al. [14,15] did is that they reframed the debate into an actionable concept by stating that through cooperative development, benefits can be increased either through opening new sources of water (volume) or increasing efficiency in use or trading water virtually (value).

Phillips [14] reported on the preliminary use of the TWO tool with 35 stakeholders from all of the Nile River riparian states. They organized a three-day workshop where these participants representing different sectors brainstormed their needs and priorities of their countries in relation to water and development opportunities. They considered various potential linkages between water and development such as with energy sector, agriculture, land, environmental conservation, political and legal issues, and made notes regarding their preferences. Having carefully noted these preferences, they compared them with the ones of others and sought possible areas for cooperation. A color-coded methodology helped to identify and rank mutually beneficial priorities that would then be studied further. On the advantage of the approach to transform pre-existing disagreements into cooperative opportunities, Phillips ([14]) pp. 19–20) notes: “At the time of the workshop, the riparians were locked into a challenging process involving the consideration of the draft Cooperative Framework Agreement for the Nile, with outstanding disagreements over the wording of the draft agreement in respect to Article 14. This relates to the core of the discord between the riparians in terms of the historical volumetric agreements from 1929 and 1959, and the opposing Nyerere Doctrine. Despite this source of conflict and securitisation, the representatives at the workshop collaborated without difficulty on the task of preparing the TWO Analysis matrix. This emphasizes the “non-threatening” nature of the TWO Analysis procedure as a whole.”

The practical application of the TWO tool was indeed a major progress in operationalization of the benefit sharing approach in terms of moving from conceptual ideas to realizing them in the field. However, a full-scale operationalization of benefit sharing in terms of implementation of actual agreements with shared benefits is yet to be seen in the water sector. Implementation seems to be the weakest phase of benefit sharing.

3.1.4. Example: How Benefit Sharing Could Help Transform Transboundary Water Disagreements

Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) provides a theoretical example of a “full blown” benefit sharing approach, which explains how disagreement between upstream A and downstream B could be transformed into cooperation with a positive outcome [45]. Although it is a purely theoretical and highly simplified example, utilizing this example we would like to describe the main idea of benefit sharing as often suggested by the growing number of models in the context of transboundary water disagreements. NBI report [45] explains that a country with a stronger economic potential could invest in developing the capacities of the weaker one that will lead first to efficiency gains, then to improved allocative efficiency (reallocating to sectors with higher return value), and finally to increased net benefits across the basin. The following adapts this example and integrates the environment as a water-using sector (not included in the original example by NBI [45]).

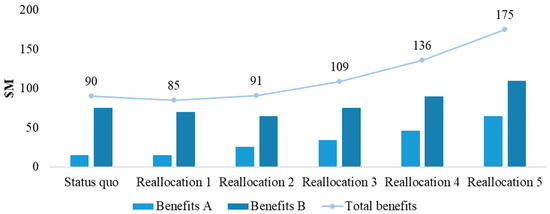

Suppose countries A and B share 100 km3 of water flow (Q) (Table 2). Country A is upstream, not industrialized but has more efficient agriculture. Country B is downstream where irrigated agriculture is a traditional and significant economic activity. The countries have an agreement that allocates 20 km3 to Country A and 80 km3 to Country B. As water resources are utilized fully, environment is degraded downstream resulting in additional costs. The combined economic return (P) of both countries from water use is US $90 million.

Table 2.

A theoretical example of transboundary benefit sharing.

Country A believes that the present sharing is inequitable and requests an increase to meet its demands for domestic use as well as to develop infrastructure (e.g., industries and hydropower). Country A, however, suggests that benefits from reallocation will be shared (agenda setting). Arbitrary assumptions are that efficiency can be increased in agricultural sector or water can be reallocated to uses that are more productive. Parties enter into negotiations and agree on a number of reallocations. After reallocation 1, total economic return falls to US $85 million, whereby Country B agrees to invest in Country A with the aim to increase own benefits in the long run.

The negative sum requires further adjustments (reallocation 2). Country A invests part of its profits from infrastructure development in improving efficiency in agriculture in Country B. Efficiency gains (additional water) are reallocated to Country A. Both countries continue investing in efficiency improvements. The total economic return might stabilize as a result, providing about as much as before the benefit sharing agreement.

Next, reallocation 3 is explained by increased efficiency downstream that allows reallocating some of the water to more productive uses such as infrastructure upstream but also finally to fully meeting the domestic demand of Country A.

Finally, both efficiency and reallocation for more productive uses continue providing enough benefits to meet development needs and ensure minimum environmental flow (reallocations 4 and 5). In the long run, while the total water available remains without major changes, both Counties A and B win individually (Figure 1), and the environmental flow increases gradually.

Figure 1.

An illustrative example of turning the zero-sum into a positive sum in the context of transboundary water disagreements. Source: Adapted from NBI [45].

3.2. Benefit Sharing to Transform the Pressure on Biodiversity

3.2.1. Agenda Setting to Transform the Pressure on Biodiversity

Benefit sharing as a concept within the biodiversity resource domain has considerably progressed due to the advances in the global biodiversity regime [68]. Pointing to increasing awareness and scientific consensus on immensely accelerated rates of species extinction, Rosendal ([68] p. 284) explains that “[t]he loss of biological diversity, which constitutes one of today’s greatest environmental challenges, entered the international negotiation agenda for two main reasons: acknowledgement of loss and value”. Solutions with win-win outcomes in biodiversity conservation can be traced back to cooperation on natural resources management in the early twentieth century (e.g., the 1911 Treaty for Preservation of Protection of Fur Seals, establishment of the 1946 International Whaling Commission) [86]. The 1972 UN Conference on Human Environment held in Stockholm gave rise to a streamlined discussions of environmental protection. A number of events from the 1970s to the 2000s (the 1971 Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, 1972 World Heritage Convention, 1973 Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, 1979 Bonn Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity, 2000 Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, 2001 International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agricultural Resources) discussed compensation mechanisms for the owners of scarce natural resources in return for restricting their use of the resources. This finally led to institutionalization of benefit sharing within the 2010 Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization (ABS).

3.2.2. Negotiations to Transform the Pressure on Biodiversity: Some Key Arguments

The 1992 UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) was a particularly important milestone that put conservation of biodiversity on a global policy agenda, and identified benefit sharing as one of its three main objectives. However, disagreements remained as to who pays for and who benefits from the use of the genetic resources, and on what terms. While the North possesses more advanced technological and economic ability to exploit genetic resources and hence can reap benefits thereof, terrestrial species diversity is highly concentrated in the South, thus accruing the major costs of conservation to the South [68].

After the CBD, negotiations continued by referring to some of the bilateral examples why and how benefit sharing should be defined as a global norm within the biodiversity resource domain. One example is around patenting and use of the rosy periwinkle, a native plant of Madagascar, by Eli Lilly, a US pharmaceutical company. Researchers at Eli Lilly, inspired by local use of the plant in traditional medicine, used traits of the plant to develop a medicine used in treatment of leukemia, which reportedly brings around US $200 million to the US company annually. However, the plant’s country of origin received no compensation [87]. Such cases pushed the CBD parties toward balancing among conservation, access, and equitable sharing of benefits from the use of genetic resources [68]. Rosendal [68] notes that the later discovery that the plant was also native to Jamaica raised new questions as to how benefits should be shared globally. In contrast, the Merck and INBio case between another US based pharmaceutical company and the National Institute for Biodiversity of Costa Rica respectively, was suggested as a clear example of how benefits from biodiversity can be shared internationally [88]. Merck and INBio agreed to a two-year deal, whereby Merck agreed to pay to INBio US $1 million for biodiversity conservation, US $130,000 for setting up a research laboratory, and royalties from future revenues related to potential discoveries (undisclosed percentage) in return for 10,000 environmental samples necessary for pharmaceutical research and production at Merck. The 2010 Nagoya Protocol institutionalizes such an arrangement on the level of states; however, its implementation is yet to be seen.

3.2.3. Operationalization to Transform the Pressure on Biodiversity

With operationalization of the Nagoya Protocol being in its early stages, benefit sharing through internalization of the values of biodiversity and ecosystem services on national and lower levels has become increasingly widespread within the biodiversity resource domain. While natural scientists highlighted the accelerated rates of loss in biodiversity, particularly because of human impact, social scientists emphasized the value of biodiversity and ecosystem services. The reframed focus here is that biodiversity is presented as not just something very important for the environment and planet in broad terms, but something particularly important for human. It implicitly defines human’s ability to recognize the value of biodiversity and ecosystems as the root problem of sustainability. This can be most prominently seen within the initiative on The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), which focuses on recognizing, demonstrating, and capturing the value of biodiversity and ecosystems [89]. TEEB database alone provides summary of over 120 “examples where a focus on ecosystem services and their economic significance helped decision makers to find more sustainable solutions for the management of ecosystems” [89].

3.2.4. Example: How Benefit Sharing Could Help Transform the Pressure on Biodiversity

One of the case studies within the TEEB database describes benefit sharing with the purpose of conservation of Tubbataha reefs in the Philippines [90]. Despite being designated as a World Heritage Site by the UNESCO in 1993, unregulated fishing and tourism coupled with pollution from passing ships put the Tubbataha Reefs Marine National Park (TRMNP) under threat. Located in the middle of the Sulu Sea, the TRMNP is home to 396 species of corals, 463 species of fish, 79 species of marine algae, at least 9 species of seagrasses, six species of sharks, two species of sea turtles, while top predators such as manta rays and whale sharks occasionally visit the area, too. Surrounding islands provide feeding and breeding grounds for more than 44 species of seabirds and other bird species. The TRMNP is seen as a globally significant site of biological diversity [91,92,93,94].

Being designated as a World Heritage Site and later inclusion in the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance in 1999 have clearly strengthened the conservation issues in the TRMNP agenda. Local divers as well as fishers were also increasingly concerned with the state of the TRMNP [95]. Discussions started about benefit sharing in the TRMNP aimed at turning the unsustainable fishery, poaching, and consequences thereof into a positive sum cooperation without degradation of biodiversity and ecosystem services. This resulted in the collaborative initiative among stakeholders at multiple levels, involving representatives of local authorities such as Governor’s and Mayor’s offices and departments of environment and tourism, Naval Forces, small and large fishers, and representatives of NGOs (WWF-Philippines, Conservation International) and donors (UNDP GEF, Packard Foundation, Japan International Cooperation Agency, and other local and international conservation agencies). Benefit sharing in the TRMNP starts with identification of buyers and providers/sellers of environmental services. While scuba divers are the end-users in the value chain, local multi-stakeholder authority whose members represent different interests in Tubbataha acts as a provider of the environmental service.

Negotiation started with preparatory workshops that were held to distill expectations of the fishers. Local stakeholders negotiated for a share from user fees, support their livelihoods, and the launching of a coastal resources management program to improve their fisheries. External donors—Packard Foundation, WWF-US, and UNDP-GEF grant—co-financed the latter two.

In practical terms, benefit sharing in the TRMNP is implemented through introduction of first, restrictions to harvesting, hunting, and fishing in the TRMNP, and second, user-fee scheme whereby local and international divers would have to pay for accessing the TRMNP. The fees were identified using willingness-to-pay surveys. The results indicate a steady growth of total revenue from user fees while live coral cover and fish biomass are reported to have reached their highest levels within five-six years. Foregone benefits of local fishers for losing access to Tubbataha were partially compensated by sharing the revenues from tourism. Co-production of knowledge, feeling of co-ownership, and pride to participate in restoring the TRMNP, as well as improved (regulated) coastal fisheries are reported to help facilitate the transformation process [92,93,95]. Dygico et al. [95] report that although seen as a good practice in marine protected area (MPA) management, the TRMNP is still far from becoming sustainable, particularly due to financial constraints. However, they highlight that recognizing foregone opportunities of the local fishers, as well as agreeing and fully enforcing the continuous compensatory mechanisms set an important precedence recognizing and operationalizing equity and stewardship rights of local populations while conserving biodiversity of global importance.

3.3. Benefit Sharing to Transform Competition for Land

3.3.1. Agenda Setting to Transform Competition for Land

Our third case describes trends related to complex socio-ecological system of large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs)—the buying or leasing of large pieces of land by foreign companies, governments, and individuals, which have increased in extent and pace over the last two decades. The idea of searching for win-win solutions is slowly entering the international land acquisitions debate, too; particularly in those cases characterized by negative effects, and thus named land grabbing [17]. There are not many studies that describe benefit-sharing cases where land grabbing was successfully transformed into a positive sum. Currently, more attention in the LSLAs research is being paid to complex interrelations of LSLAs with other natural resources, such as water grabbing [96], or soil grabbing given the income that can be generated from the sale of the carbon absorbed by the soil [17].

Azadi et al. [17] differentiates among four possible outcomes of LSLAs. First are loss-loss deals, which are destructive and should be stopped. The win-loss deals, which bring benefits only to the investor, as well as loss-win deals, which rather represent development aid, need adaptation in governance to allow for better results. The win-win deals, which they called green deals, are the ones with potential to significantly promote the agricultural sector of host countries. In this respect, trading land rights for overall development (employment generation and infrastructure development) [97] can be seen as a way forward to realize benefit sharing. What is striking when looking at LSLA processes in regard to benefit sharing though, is that case studies rather explore only the extent to which local communities and users are included in deal making and compensation, and the factors facilitating or hampering that [97], while concrete win-win options are not discussed.

In respect to land deals, the 2012 FAO Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security [23] can be seen as an agreement raising the issue of benefits for both investor and investee on the international agenda. The pressure here is to share the benefits from the LSLAs more equitably, and it mainly comes from the high media attention reporting on cases with negative social and environmental outcomes combined with the scholarly recognition, supported by the gathering of data, such as in the publicly available Land Matrix database. All of these try to influence the processes mostly by exposing governments, international businesses, and credit institutes involved in such deals to a risk of reputation loss.

3.3.2. Negotiations to Transform Competition for Land: Some Key Arguments

As noted, the exclusion of the broad range of affected actors from the negotiating processes is reported as the main cause of inequitable sharing of the benefits from the LSLAs [97]. However, from an investor point of view, there might be little incentive to share the benefits, as it would mean loss of profit at least to some degree. We hold that the risk of the investor, embodied in insecurity of promised water and land rights—as investors’ rights are often vulnerable in developing countries, especially in times of internal instability—is what actually can enlarge the pie in negotiations, and therefore could be the key point in shaping the benefit sharing argument. There is need for a stronger emphasis that by sharing the benefits with the local communities as well as by contributing to the development of local economies, investors will also invest in their longer-term stability and reputation. The question remains as to how to set up a collaborative governance system (e.g., [98]) that allows negotiating development of infrastructure, for example, establishment of health centers, schools, training sites, roads, drinking water networks, houses, equipment for security guards and alike in exchange for a better guarantee of the land rights. In this regard, trading secure access and withdrawal rights against investments in other sectors could represent a good use of in-kind compensation and issue linkage mechanisms of benefit sharing. Further, in such an arrangement, it needs to be highlighted that investor could also benefit directly from an improved infrastructure. For example, constructing proper roads and railways might help in exporting the products and transporting farm machines and equipment, all the while facilitating development in the host country.

Von Braun and Meinzen-Dick [99] call in that respect for a combination of an international code of conduct on the one hand, and improved domestic agricultural policies, on the other, that would make win-win outcomes a virtue of the investments. A spillover benefit here could be that investors might push the host governments for better tax conditions for farmers, which could also benefit the local producers. Transparency of these processes but also of the wider national statistics related to land deals, in turn, can serve as a driver to initiate more inclusive negotiations. The objective awareness of the impact of land deals could lay the groundworks for changing the perceptions of political actors. Teklemariam et al. [100] also warn that achieving benefit sharing solutions is particularly difficult in LSLAs. This is because there are only two groups (investor and investee or officials of guest and host countries) who participate in negotiations while those affected represent a far larger group of actors. Azadi et al. [17] point out that inclusive deals will require involving all interested parties in the negotiations (farmers, investors, representatives of civil society, and public authorities), and adapting to one another’s demands and offers, taking on diverse and often conflicting interests and differentiated powers.

3.3.3. Operationalization to Transform Competition for Land

Although there is no detailed study reporting on operationalization of successful win-win situations in LSLAs, the trends in relation to realizing benefits of LSLAs point to a number of problematic as well as promising areas of work. Primary consideration is the data availability. Practical aspects of moving toward win-win solutions start with simple reforms of governance structures as to improve administrative and cadastral data collection, which allows assessing the productivity of land use and taking measures to increase it. This in turn will allow identifying spillover effects from large-scale investments to small-scale farming. There is need for reliable and regular information in principle (is the land transferred to investors utilized, where is investment most desirable, how effective is the performance) to realize positive effects that come along with foreign investments. An example is Ethiopia, a country that, in line with Africa being the most targeted continent, has seen a significant rise in the number of LSLAs [101,102]. However, the actual data for Ethiopia show that 50% of the transferred land remains unutilized [103]. Further data show that commercial farms largely failed to generate the promised levels of employment with a record of only one permanent job per twenty hectares plus some temporary jobs.

Other studies, for instance in Mali, show possible application of in-kind compensations. Where cash compensation is unlikely to restore local livelihoods because of very low market value of land, a large scale irrigation project in Mali is reported to involve compensation in the form of irrigated land, namely, of five hectares per household [97]. Studies from Tanzania illustrate that levels and terms of compensation are rarely straightforward as it is difficult to agree on the amount of financial compensation in the absence of active monetized markets [97]. The gemstone deal in Madagascar shows for instance, that instead of rental fees for the farmland, an in-kind compensation in the form of jobs was promised. For a 450,000 hectares deal, 4500 part-time jobs were agreed. However, these jobs turned out to be unskilled, short-term, and smaller in number, thus overall not very valuable in terms of bringing benefits to local development [104].

3.3.4. Example: How Benefit Sharing Could Help Transform Land Acquisition Deals

A study of LSLAs in North Eastern Uganda [105], where the majority of land plots are held under customary tenure [106], reveals that approximately 62% of the total land area of the Karamoja region has been licensed for mineral exploration and exploitation [105]. Very few companies have actually started exploration, because the majority of the concessions were given to speculators who would then search for investors. The analysis shows that only after the establishment of the Communal Land Associations (CLAs) were the local communities able to voice their claims to the land. These CLAs enabled communities to act as legal entities and to register their claims under the Ugandan Law.

Interestingly, the Uganda Land Alliance has been the crucial actor to initiate the process of the CLA formation and thus empowering the local people to be able to negotiate with the speculators and investors. In contrast, Vermeulen and Cotula [97] argue that improved rights over land do not provide the necessary bargaining power for local land users to achieve better outcomes from the deal-making process. Instead, a legally required consultation process with local communities such as specified in Mozambique and Tanzania should be a precondition for successful negotiation [97]. This mandatory governance process paved the way for the negotiation of benefit sharing agreements in those cases. However, as Vermeulen and Cotula [97] point out, although the consultation is legally binding, benefit-sharing agreements reached within those consultations are generally not documented formally and represent legally non-binding contracts.

The Uganda case shows that the newly formed CLAs started negotiations with the investors and have been able to claim financial compensation for their loss of land rights. Two other implicit benefits, which appeared in the study on Uganda, are that in the course of the geographical mapping of the community land, the community elders for the first time could identify their communal lands, and thus develop a better awareness of their resources [105]. In total, fifty-two CLAs obtained the maps of their communal lands as a result. Second, this empowered the communities to defend their land rights and enter the negotiations. Although benefit-sharing processes are very far from maturity here, the fact that local communities feel more empowered to protect their lands can be seen as an important spillover benefit of these processes.

4. Discussion

Trends within the analyzed three complex socio-ecological systems show that benefit sharing as an approach does in fact help reframe the debate and facilitate the adaptive processes toward sustainability of these systems. While this represents a major reframing on its own where focus shifts from individual rights to benefits for all, we observed significant differences in reframing within each of these three resource domains. Broadly looking from a long-term sustainability perspective, the current state of benefit sharing within the analyzed socio-ecological systems—sharing water, preserving biodiversity, and acquiring land—seem to have different emphasis on economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainability (Table 3). While benefit sharing clearly has an effect on all three dimensions of sustainability, the framing places different emphasis in different contexts. In general, we have seen that the emphasis can be on achieving cooperation because of economic value of doing so. The emphasis can be on equitable sharing of the benefits, thus the focus is rather on sharing than benefits. Finally, the emphasis might stem from the environmental considerations of natural resource use.

Table 3.

Framing emphasis of benefit sharing across dimensions of sustainability within water, biodiversity, and land resource domains.

Benefit sharing, as discussed in relation to transboundary water disagreements, although provides a relatively clear conceptual process of moving from volume toward value of water, there is little evidence on making transformations equitable for local communities. Similarly, environmental benefits seem to be neglected completely, even within the Benefit Sharing Framework of the Nile Basin Initiative where benefit sharing significantly evolved as an approach. Hence, despite the theoretical promises of the approach that it can generate a broad spectrum of benefits, including environmental [11,40], the narrow economic emphasis clearly continues to prevail. The Tubbataha reefs case from the Philippines demonstrates how benefit sharing within the biodiversity resource domain that inherently focuses on the environmental dimension and equitable sharing of the benefits toward locals might be able to find economically viable solutions. Although not yet financially sustainable, the Tubbataha case seems to demonstrate the necessary societal resilience driven by the pride of local communities to be part of the transformation. Finally, the analysis of the increasingly promoted benefit sharing related to land acquisitions demonstrates that the main focus here is on ensuring equitable sharing of the benefits, while making the deals economically attractive for all affected sides is still immature, and preserving the environmental qualities of the resource system is missing altogether. Negotiating parties stick to their positions or the local users and farmers are not yet empowered enough to start negotiating processes. NGO guidance continues to increase, particularly with the FAO Voluntary Guidelines in combination with the high media attention. While awareness of the need for win-win processes is there, within the individual cases understanding how governance can be adapted so that all sides can win is not.

Framing as such is an art of working with emphasis. Without changing the substance in a social setting, one can facilitate different outcomes by placing greater emphasis on some aspects and lesser emphasis on others. This phenomenon is known as framing effects. In this respect, there seems to be a risk of “overemphasis” within the analyzed water and land resource domains. In these two cases, the prevailing objective of benefit sharing (or win-win) is facilitation of cooperation and equitable allocation respectively. This is understandable, because the problem structure within these resource domains has been conflicting interests between riparian parties and exclusion of locals from resource use accordingly. Hence, benefit sharing aims to address these very problems. However, if we look at sustainability of the entire system as a primary objective, then one should remember that benefit sharing could only serve as an intermediate outcome [107], whereas the final outcome should be correspondingly more system-oriented, for example, establishment of a resilient society able to adapt to ever changing environment. Therefore, it is highly likely that underemphasizing resource sustainability, as a side-effect of overemphasizing economic and/or social aspects, will lead to new levels of stress (also known as rebound effect when improved efficiency and technology lead to increased use, see also [108]); or become an obstacle already at the implementation phase of agreed terms and distribution of benefits when parties realize the resource scarcity.

In contrast, benefit sharing within the biodiversity resource domain seems to have the focus necessary for the overall sustainability relatively well aligned. That seems to be reasonable because once the ultimate objective is set as achieving sustainability of natural resources and equitable sharing of the benefits, it is probably safe to assume that actors seeking benefit sharing will not ignore economic return. The opposite is however, as discussed above, not true. Once the prevailing focus is on economic return, ensuring natural resource sustainability and equitable sharing of the benefits toward local populations might be easily neglected at least for the lack of their representation.

Our analytical approach that we partly adapted from regime analysis also helped to clearly reveal the dynamic nature of framing in the use of benefit sharing as a governance approach. The developments related to the GERD constructions in the Nile Basin show that although the international donor community had emphasized more the mutually beneficial economic value of cooperation through benefit sharing [13,14,15], later, hydro-hegemony scholars [77] as well as the Ethiopian government emphasized more the equitability aspect of benefit sharing [78,109]. First, it shows that the concept can be highly political as it provides a great room for manipulation through framing and reframing. This also shows the challenge related to typologies of benefit sharing, that is, of assigning the benefit sharing arrangements to one or another type of benefit sharing. For example, following the typology suggested by Nkhata et al. [18] would signal that most of the benefit sharing arrangements in complex socio-ecological systems would display characteristics from all of the three—co-management, market-oriented, and egalitarian—types of benefit sharing. This is while the varying emphasis on the environmental aspect of natural resources is largely considered as given. In contrast, we stress that it is important to look at the relative emphasis placed on these categories within the benefit sharing arrangements to be able to understand implications for the overall sustainability of the systems.

Further, the analysis has revealed both the major strength and a number of challenges common to benefit sharing in all three analyzed resource domains, but perhaps inherent to the underlying transformative nature of benefit sharing. On the one hand, while lessons related to agenda setting and negotiations about underlying principles of benefit sharing for overall sustainability seems to be relatively straightforward (that is, setting environmental conversation and equitability of sharing as top priorities), operationalization seems difficult, raising questions on modalities of setting up the collaborative governance regimes that would lead to sustainable benefit sharing [98]. The examples show that the role of non-state actors (especially of domestic and international NGOs and development agencies) is often crucial for representing the sustainability and equitability concerns, and inducing more inclusive transformation processes. Bringing these issues to attention sufficiently early, or as Emerson and Nabatchi [110] argue in line with path dependency theory, how collaborative governance regimes are formed, will greatly influence the collaboration dynamics over time. Hence, the initial emphasis is critical.

On the other hand, because benefit sharing promises a win for each and all, it can attract attention of all sides, including of those who might have a more advantageous position at present. In this respect, the concept of benefit sharing provides the so-called “constructive ambiguity”, the term Najam [111] uses to describe the greatest strength of reframing the debate into sustainability. Najam ([111] p. 225) explains, “sustainability” provides constructive ambiguity, that is, “actors that otherwise might not talk to one another could accept the concept for very different reasons and agree to talk”. It is exactly where benefit sharing is most powerful, too, and as such could be even viewed as a newer, refined version of sustainability. However, one must keep in mind that this very quality of benefit sharing might in fact prove to be exploitative where powerful actors can lobby to frame the emphasis for their own benefit, and use promises to make utilitarian gains (e.g., [112,113,114,115,116,117]). At the same time, because benefit sharing eventually requires change in use, it constitutes another important challenge as some resource users and owners will have to give up their rights or restrict their access. Indeed, to ensure equitability, this gap can be filled with the use of compensation mechanisms. However, as the complexity of socio-ecological system increases and we move toward more complex mechanisms of benefit sharing, transaction costs will be higher, as number of actors and size of the resource system will require greater awareness, learning, and coordination [39]. In this respect, availability and transparency of reliable data across the board will be crucial to prevent destructive opportunistic behavior [52,118].

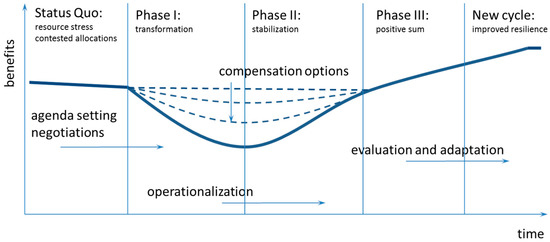

We believe it is important to emphasize further this lesson related to the time perspective, that transformation through benefit sharing is likely to lead to losses first, before resulting in a positive sum (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Transformation through benefit sharing.

Both water and biodiversity cases show that transformation to more sustainable practices through benefit sharing requires a temporary loss in total benefits. For transformations in land acquisitions, investors will likely have to give up certain share of otherwise higher revenues at the beginning, if benefits were to be shared with local communities. One non-monetary benefit is of course stability, as more equitable sharing will likely result in less contestation and conflict. However, within this period, mobilizing domestic as well as external financial resources might be important to compensate the losses of traditional/historical users. Compensation mechanisms of benefit sharing (financial and in-kind) can help during this period until stabilization is reached allowing further positive outcome. Issue linkages (within and outside sector) might further open up new benefits that are potentially more sustainable than mere compensations. Thus, not all of the loss-loss cases can be characterized as destructive (contrary to Azadi et al. [17]): loss-loss in the short term might be necessary to achieve win-win in the long term. It might be more so as the size of the resource system and number of involved stakeholders increase making transformative processes more costly [39]. As it goes in the well-known African proverb, as far as sustainability and continuous ability of societies to adapt to the ever changing environment are concerned, one might prefer going together and far over going fast but alone.

A next step in the analysis of the applicability of benefit sharing is an improved understanding of post-negotiation processes, when an agreement is reached and contract is signed. Quite often discrepancies occur between a formal agreement and its implementation, due to reasons beyond control but also because of a deliberate opportunistic strategy. Overall, complexity of the socio-ecological systems in the use and governance of shared natural resources coupled with ambiguity of the benefit sharing concept offers substantial room for manipulation, whereby actors that are more powerful can take advantage of those more vulnerable by making vague promises and using intangible benefits for their own gains. For the land sector, for instance, it is not clear how enforceable investors’ promises on local benefits can be [97]. Similarly, more data and research are needed to understand how to ensure that commitments are implemented in good faith in other complex socio-ecological systems, especially those involving parties beyond single jurisdiction. There is need for further research toward structured analysis of problems in de-facto implementation of the (signed) agreements to better tailor benefit sharing arrangements for sustainable adaptation processes.

5. Conclusions

This study has explored the transformative power of the benefit sharing approach to move from volume to value of shared natural resources in three complex socio-ecological systems: sharing water, preserving biodiversity, and acquiring land. The observed trends show that reframing the problems from the benefit sharing perspective has a strong potential to foster adaptive governance for reaching sustainability in human–environment systems, particularly where such interaction is complex. It is true that the costs of transformation might outweigh immediate benefits; however, these losses might be necessary to achieve win-win situations in the long run. However, one needs to be aware of the exploitative potential of the concept arising from its ambiguity and therefore potentially dynamic and conflicting nature of interpretation by various actors at different points in time. The same concept can be interpreted to promote environmental sustainability, equitability in sharing, and economic value of collaboration. We asserted that the first two should be set as the top priority for the overall sustainability while carefully facilitating governance processes that are more inclusive. In addition, benefit sharing mechanisms (compensations and issue linkages) when well-tailored to the cases in point are able to provide innovative solutions to cope with the possible transaction costs. Importantly, the processes with shared benefits, where one places sufficient emphasis on recognition and integration of the value natural resource systems provide, as well as on ensuring equitable sharing of the benefits, can result in societal learning crucial for adaptation to continuously changing circumstances. Successful adaptation means that systems provide room for governance structures that facilitate adaptation and learning. Benefit sharing comes to be a promising approach to meet the societies’ need in learning to recognize opportunities that can turn zero-sum games into positive sum interactions, and making long-term transformations toward sustainability.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Ilkhom Soliev and Insa Theesfeld designed the structure of the study, conducted the research and discussed the findings. The paper is a result of a close collaboration between the authors. Ilkhom Soliev led the research, drafted the first and final versions of the article incorporating multiple contributions of Insa Theesfeld. Ilkhom Soliev revised the manuscript based on the comments from the reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mitchell, R. International Environmental Agreements (IEA) Database Project. Available online: https://iea.uoregon.edu/ (accessed on 19 July 2017).

- Berkes, F. Environmental Governance for the Anthropocene? Social-Ecological Systems, Resilience, and Collaborative Learning. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Nested externalities and polycentric institutions: Must we wait for global solutions to climate change before taking actions at other scales? Econ. Theory 2010, 49, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Barrett, S.; Polasky, S.; Galaz, V.; Folke, C.; Engström, G.; Ackerman, F.; Arrow, K.; Carpenter, S.; Chopra, K. Looming global-scale failures and missing institutions. Science 2009, 325, 1345–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Economic Forum. Global Risks 2016; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brienen, R.J.; Phillips, O.L.; Feldpausch, T.R.; Gloor, E.; Baker, T.R.; Lloyd, J.; Lopez-Gonzalez, G.; Monteagudo-Mendoza, A.; Malhi, Y.; Lewis, S.L.; et al. Long-term decline of the Amazon carbon sink. Nature 2015, 519, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butchart, S.H.; Walpole, M.; Collen, B.; Van Strien, A.; Scharlemann, J.P.; Almond, R.E.; Baillie, J.E.; Bomhard, B.; Brown, C.; Bruno, J. Global biodiversity: Indicators of recent declines. Science 2010, 328, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Global Sustainable Development Report, Advance Unedited Version; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, M.; Knutti, R.; Arblaster, J.; Dufresne, J.-L.; Fichefet, T.; Friedlingstein, P.; Gao, X.; Gutowski, W.; Johns, T.; Krinner, G. Long-term climate change: Projections, commitments and irreversibility. In Climate Change 2013—The Physical Science Basis; Stocker, T., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; Chapter 12; pp. 1029–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Susskind, L. Environmental Diplomacy: Negotiating More Effective Global Agreements; Oxford University Press: Cary, NC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sadoff, C.W.; Grey, D. Cooperation on international rivers: A continuum for securing and sharing benefits. Water Int. 2005, 30, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L.E.; Ali, S.H. Environmental Diplomacy: Negotiating More Effective Global Agreements; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, D.; Daoudy, M.; McCaffrey, S.; Öjendal, J.; Turton, A. Trans-Boundary Water Co-Operation as a Tool for Conflict Prevention and Broader Benefit Sharing; Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sweden: Stockholm, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, D.J.H. The Trans-Boundary Waters Opportunity Analysis as a Tool for RBOs. Available online: http://www.waternet.co.za/sadcrbo/docs/dps7388sadcTWO.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2017).

- Phillips, D.J.H.; Allan, J.A.; Claassen, M.; Granit, J.; Jägerskog, A.; Kistin, E.; Patrick, M.; Turton, A. The TWO Analysis: Introducing a Methodology for the Transboundary Waters OpportunityAnalysis; Stockholm International Water Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Qaddumi, H. Practical Approaches to Transboundary Water Benefit Sharing; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Azadi, H.; Houshyar, E.; Zarafshani, K.; Hosseininia, G.; Witlox, F. Agricultural outsourcing: A two-headed coin? Glob. Planet. Chang. 2013, 100, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkhata, B.A.; Mosimane, A.; Downsborough, L.; Breen, C.; Roux, D.J. A Typology of Benefit Sharing Arrangements for the Governance of Social-Ecological Systems in Developing Countries. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaphake, A. Kooperation an Internationalen Flüssen aus Ökonomischer Perspektive: Das Konzept des Benefit Sharing; German Development Institute/Deutches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE): Bonn, Germany, 2005; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). About the Nagoya Protocol. Available online: http://www.cbd.int/abs/about/ (accessed on 11 September 2016).

- Morgera, E. The Need for an International Legal Concept of Fair and Equitable Benefit Sharing. Eur. J. Int. Law 2016, 27, 353–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgera, E. Fair and equitable benefit-sharing at the cross-roads of the human right to science and international biodiversity law. Laws 2015, 4, 803–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.; Ury, W.; Patton, B. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement without Giving in; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, G.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W., III. The Limits to Growth; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Boserup, E. The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change under Population Pressure; Aldine Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.; Khalid, M.; Agnelli, S.; Al-Athel, S.; Chidzero, B.; Fadika, L.; Hauff, V.; Lang, I.; Shijun, M.; de Botero, M.M. Our Common Future (‘Brundtland Report’); Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]