Abstract

This study presents an integrated analysis of climate-driven phenology and infestation dynamics of the invasive oak lace bug (Corythucha arcuata) in foothill oak ecosystems of Rășinari, Romania. Using reconstructed microclimatic data for 2024–2025, systematic field monitoring, degree-day (GDD) modeling, and the De Martonne aridity index, we assessed the combined effects of thermal accumulation and hydric stress on multigenerational development. Results indicate that warm springs and sustained summer temperatures enabled the completion of two full generations (G1–G2) in both years, while recurrent late-summer aridity intensified foliar vulnerability and accelerated nymphal development. A third generation (G3) was initiated but remained incomplete due to declining autumn temperatures and photoperiod constraints. Strong habitat-specific differences were observed: exposed forest-edge stands exhibited the highest damage levels (up to 90%), whereas closed-canopy stands benefited from microclimatic buffering. The combined GDD–aridity framework showed close agreement with observed phenological transitions, providing a robust tool for identifying high-risk infestation periods. Climatic projections for 2026 suggest further advancement of generational timing under continued warming and increasing aridity. These findings highlight the growing climatic suitability of foothill oak ecosystems for C. arcuata and support the development of early-warning systems and adaptive strategies for sustainable oak forest management.

Keywords:

Corythucha arcuata 1. Introduction

Invasive forest insects have emerged as one of the most significant biological stressors affecting temperate and subtropical forest ecosystems worldwide, driven by synergistic forces such as global trade intensification, habitat fragmentation, and climate change–induced alterations in temperature and moisture regimes [1,2,3,4] (e.g., IPCC, 2018 [5]).

Among these species, the oak lace bug Corythucha arcuata Say, 1832; has become a high-impact invasive pest in European oak forests owing to its rapid geographic expansion, ecological plasticity, multivoltine reproductive potential, and capacity to exploit a broad range of oak-dominated habitats [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Native to North America, C. arcuata was first reported in Europe in northern Italy at the turn of the century [1]. The rapid spread of C. arcuata across Europe and large parts of Eurasia has been comprehensively documented [2,3,4,6,7,8,10,11,12,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Recent reports indicate ongoing expansion both northwards and eastwards, facilitated by climate-driven suitability shifts and intensifying cross-border transport networks [16,17,22,27].

C. arcuata expansion across Europe has been attributed to a combination of biological traits—including short generation intervals, high fecundity, and phenological synchrony with host foliage—and environmental drivers such as elevated temperatures, prolonged summer heat, and drought-induced physiological stress in oak species [8,9,10,12,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Heat accumulation expressed through degree-day (GDD) units is known to accelerate developmental progression and increase the likelihood of completing multiple generations per season [8,10,15,16,23,28,29,30,31,38], while hydric stress alters leaf turgor, stomatal conductance, and mesophyll transparency, thereby enhancing host susceptibility to piercing–sucking herbivores [13,24,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Spatial heterogeneity in microclimate further modulates infestation intensity: forest edges and exposed stands consistently exhibit higher levels of damage due to enhanced irradiance, increased temperature fluctuations, and reduced relative humidity, whereas interior stands tend to buffer climatic extremes [14,23,28,32,40,41].

In Romania, C. arcuata was first reported in the southern and southwestern regions and subsequently documented in central and foothill areas, including urban and peri-urban oak habitats [17,18,19,24,26,42,43,44]. However, despite numerous regional observations, several critical knowledge gaps remain. Existing studies have not sufficiently quantified the fine-scale climatic thresholds for generational development within transitional foothill ecosystems, nor have they integrated microclimatic variability, hydric stress metrics, and field-validated phenology into a unified predictive framework. Furthermore, understanding habitat-specific vulnerability—particularly the contrasts between exposed forest edges and closed-canopy stands—remains limited despite evidence of strong microclimatic influences on infestation severity [27,28,29,32,38,39,40,41,42]. These knowledge gaps are not limited to Romania but represent broader, supra-regional challenges in understanding the climate-driven population dynamics of C. arcuata across Eurasian oak ecosystems.

1.1. Study Aim

The primary aim of this study is to assess how interannual climatic variability, microclimatic gradients, and hydric stress jointly influence the phenology, multigenerational development, and infestation severity of the invasive C. arcuata in foothill oak ecosystems. By focusing on a climatically sensitive transitional landscape, the study seeks to identify the key environmental drivers shaping population dynamics and habitat-specific vulnerability under current and emerging climate conditions.

1.2. Research Hypotheses

Based on existing evidence regarding the thermal requirements and drought sensitivity of C. arcuata, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1.

Increased thermal accumulation and recurrent late-summer aridity accelerate the multigenerational development of C. arcuata, resulting in earlier completion of the first two generations (G1 and G2) and partial initiation of a third generation (G3).

H2.

Infestation severity differs significantly among habitat types, with exposed forest-edge stands exhibiting higher foliar damage than semi-shaded ecotonal stands and closed-canopy interior forests due to reduced microclimatic buffering.

Specific Objectives

To test these hypotheses and achieve the study aim, the following specific objectives were pursued:

- (1)

- to reconstruct and analyse monthly climatic profiles (temperature, precipitation, and relative humidity) for the 2024–2025 period in the Rășinari foothill region using elevation-adjusted meteorological data;

- (2)

- to document field-based phenological transitions of C. arcuata (adult emergence, oviposition, nymphal instars I–V, and adult peaks) across contrasting habitat types;

- (3)

- to quantify generational thresholds using a degree-day (GDD)-based phenological model incorporating thermal requirements and high-temperature inhibition effects;

- (4)

- to evaluate hydric stress using the De Martonne aridity index and examine its interaction with microhabitat exposure and foliar damage intensity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The research was conducted in the foothill oak ecosystems of Rășinari commune, Sibiu County, Romania, located between 45.712° N and 23.980° E, at elevations ranging from 500 to 800 m a.s.l. This region is situated at the ecological transition between the Sibiu Depression and the lower montane zone of the Cindrel Massif, forming a heterogeneous landscape where geomorphology, elevation, and vegetation structure contribute to pronounced microclimatic variability. The terrain consists of gently inclined slopes, narrow ridges, and small plateaus, interspersed with shallow valleys that channel cold air during the night and accumulate warm, dry air during the daytime. These topographic characteristics, together with differences in slope orientation and canopy architecture, create distinct gradients in temperature, humidity, and solar exposure.

Vegetation and Habitat Structure

The forest composition is dominated by mixed oak stands, primarily Quercus robur L., and Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl., which represent characteristic Central European deciduous forest communities. These stands are intermixed with hornbeam Carpinus betulus L., and beech Fagus sylvatica L., forming structurally diverse, uneven-aged forest patches that enhance spatial heterogeneity. Understory vegetation is typically sparse, consisting of shade-tolerant shrubs and herbaceous species. The combination of broadleaf canopy cover and varied stand density creates a mosaic of microhabitats with differential buffering capacity against climatic extremes.

To capture the full range of microclimatic conditions, three habitat categories were selected based on canopy structure, solar exposure, and edge effects: exposed forest-edge stands, characterized by direct solar radiation, elevated daytime temperatures, and strong diurnal fluctuations; semi-shaded ecotonal stands, representing transitional zones between edge and interior forest, where microclimatic conditions are intermediate; and closed-canopy interior stands, typified by dense canopy cover, moderated temperature gradients, and higher relative humidity, providing effective microclimatic buffering.

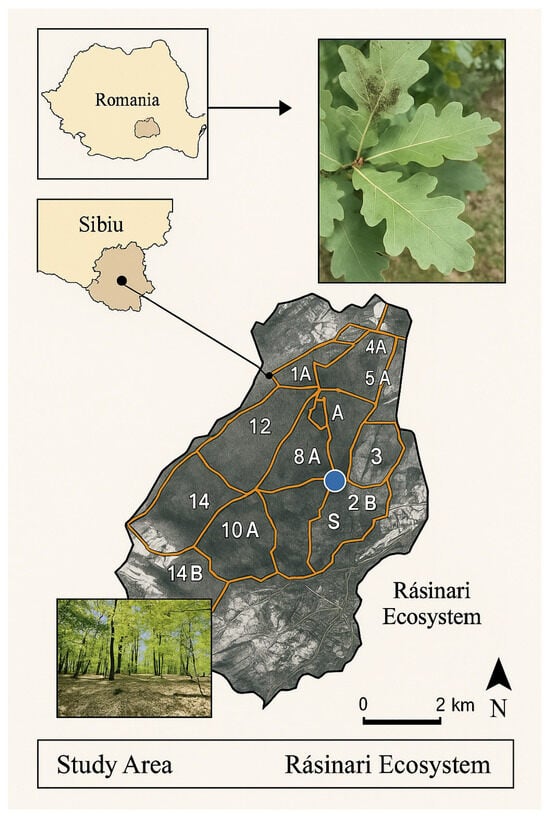

These habitat types are spatially distributed within Ocolul Silvic Rășinari and are illustrated in Figure 1. All sampling activities were conducted with the approval of the local forestry authority (Ocolul Silvic Rășinari, Permit No. 27/2024). No protected species or ethical concerns were involved, as all procedures relied on non-destructive monitoring of insect populations and foliar injury assessment. The study complied fully with national environmental legislation and forest management protocols, ensuring minimal ecological disturbance throughout the field campaigns.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area in Rășinari (Sibiu County, Romania), showing the national context, the position within Sibiu County, and the delineated forest compartments where field monitoring and sampling were conducted. The map includes a 1 km scale bar and cardinal orientation markers. The parcels on the map are coded according to the forest management plan of the Rasinari Forest District.

2.2. Climatic Data Acquisition and Reconstruction

Meteorological data were obtained from the Romanian National Meteorological Administration (ANM), Sibiu and Păltiniș stations. Monthly climatic data for 2024–2025 were reconstructed using a hybrid approach integrating measurements from two regional meteorological stations—Sibiu (440 m) and Păltiniș (1450 m)—and elevation-adjusted lapse-rate corrections. The elevation correction for temperature followed the standard environmental lapse rate of −0.65 °C/100 m. Precipitation scaling accounted for orographic amplification typical of foothill areas.

Temperature (minimum, maximum, mean), relative humidity, and monthly precipitation totals were validated against regional climate normals (1991–2020). Microclimatic data at tree level were recorded weekly using a calibrated multifunctional handheld meter (Kestrel 5500 Weather Meter, accuracy ±0.5 °C for temperature, ±3% for RH). Calibration checks were performed monthly following manufacturer guidelines.

These reconstructed profiles served as inputs for degree-day (GDD) calculations and aridity index estimations.

2.3. Field Monitoring and Phenology Assessment

Tree age was estimated based on diameter at breast height (DBH) using regional allometric relationships for mature oak stands. Field monitoring was conducted throughout the active season of C. arcuata, from April to October in both 2024 and 2025, covering the entire developmental cycle of the species. Thirty mature oak trees (diameter at breast height > 35 cm, age estimated > 70 years) were selected across the three habitat types (10 trees per habitat), ensuring comparable structural characteristics, canopy accessibility, and the absence of recent silvicultural operations (e.g., thinning, pruning, harvesting). Selection criteria also included crown health status, accessibility for repeated sampling, and spatial separation between trees to avoid microclimatic redundancy. Thresholds included absence of visible mechanical damage, no recent silvicultural interventions within the last five years, and homogeneous crown exposure.

Sampling height was standardized at 2.0–3.0 m above ground level to control for vertical variation in microhabitat conditions and to ensure the collection of leaves exposed to natural light regimes and insect activity. This height corresponds to the lower canopy zone where nymphal and adult densities of C. arcuata are known to be highest, while minimizing vertical microclimatic variability. The standardized height also allowed consistent access to leaf surfaces for repeated measurements and minimized sampling bias associated with canopy position.

Weekly surveys were performed following a structured protocol and included: detection of overwintered adult emergence and initial dispersal patterns; quantification of oviposition initiation and egg batch density per leaf; distribution and abundance of nymphal instars (I–V), recorded based on morphological criteria and developmental markers; counts of newly emerged adults and adult accumulation dynamics; assessment of foliar damage intensity associated with feeding activity.

Each week, for every tree, three branches were selected at fixed cardinal orientations (North, East, and South), a methodological choice designed to capture spatial variability in sunlight exposure, microclimatic gradients, and potential directional patterns of infestation. Branches were selected at fixed cardinal orientations (North, East, and South) to capture contrasting microclimatic conditions while maintaining methodological consistency across all sampled trees. West-facing branches were deliberately excluded to avoid overestimation of maximum damage levels caused by short-term afternoon heat peaks and extreme solar exposure. Preliminary reconnaissance observations indicated that west-facing leaves frequently exhibited transient thermal stress and premature senescence, which could confound chronic feeding-related injury with acute abiotic damage. By excluding the westward exposure, the sampling design focused on biologically sustained infestation effects rather than short-duration microclimatic extremes. On each selected branch, 30 leaves were examined, resulting in 90 leaves per tree and 2700 leaves per sampling cycle across all habitats.

Foliar injury was scored using a standardized, semi-quantitative foliar injury index ranging from 0 to 100%, integrating four damage components: chlorosis, stippling intensity, degree of necrosis, and leaf transparency. Foliar injury was quantified using a standardized semi-quantitative damage index ranging from 0 to 100%, adapted for piercing–sucking herbivores. The index integrates visible chlorosis, stippling density, leaf translucency, and necrotic tissue development. Damage classes were defined as follows: 0% = no visible symptoms; 10% = slight chlorosis and sparse stippling; 25% = moderate chlorosis with clearly visible stippling; 50% = severe chlorosis with the onset of localized necrosis; 75% = extensive chlorosis and necrosis affecting most of the leaf surface; and 100% = complete necrosis or functional leaf loss. This grading scheme ensured consistent assessment across observers, sampling dates, and habitat types. These metrics were chosen for their sensitivity to piercing–sucking herbivore activity and their applicability for interannual comparisons. Values were averaged per tree and per habitat type to obtain representative damage profiles and to enable statistical analyses.

Microclimatic parameters—air temperature (T), relative humidity (RH), solar exposure, and qualitative estimates of recent precipitation—were recorded concurrently at each sampling point using a calibrated handheld weather meter (±0.5 °C temperature accuracy, ±3% RH). These environmental measurements ensured that infestation dynamics could be directly correlated with local microclimate rather than relying solely on regional meteorological data.

Statistical Design and Replication Structure

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. In 2025, enhanced thermal accumulation advanced both G1 and G2 by approximately 7–10 days. The cumulative GDD reached >800 °C·days by 28 May and >1600 °C·days by 20 July. For each habitat type, ten mature oak trees were monitored, and on each tree, 90 leaves were examined per sampling event (three branches × 30 leaves), resulting in n = 900 leaf-level observations per habitat type per season. Data were analyzed using R software (version 4.3.1). Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and homoscedasticity using Levene’s test. Because the assumptions of normality and homogeneity were not met, differences in foliar injury among habitat types were evaluated using the Kruskal–Wallis H test, followed by Dunn’s post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

Additional qualitative observations were noted during each survey, including leaf phenology (budburst, expansion, senescence), the presence of co-occurring herbivores or natural enemies, and visual symptoms of drought stress (leaf curling, marginal browning). These contextual observations supported the interpretation of insect development stages in relation to host plant physiological condition.

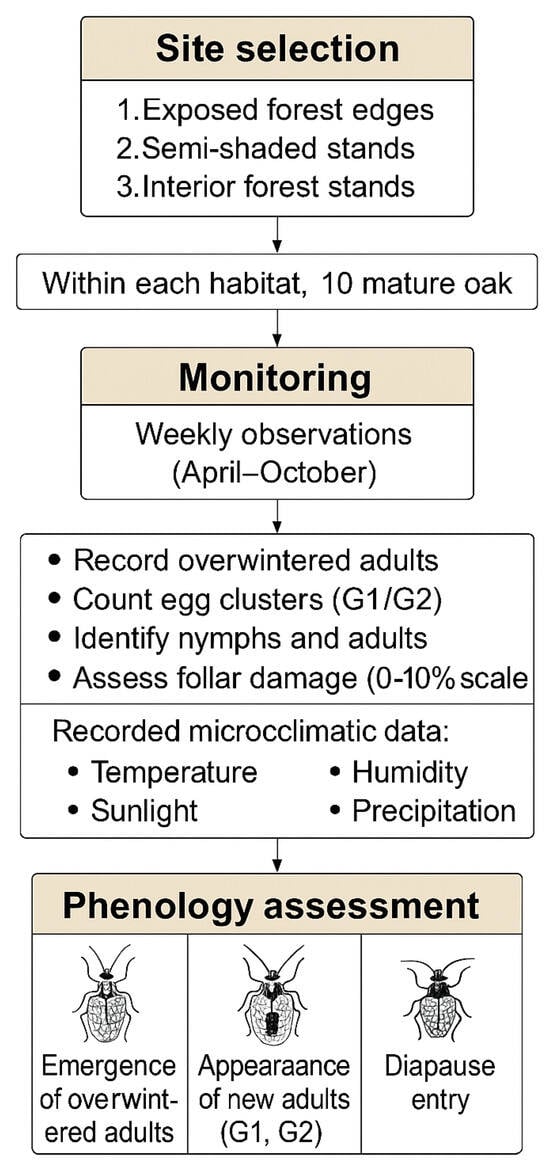

The complete workflow for field monitoring and phenology assessment—including tree selection, leaf sampling methodology, damage scoring system, and microclimatic measurements—is illustrated in Figure 2, providing a visual overview of the standardized procedures implemented throughout the two study seasons.

Figure 2.

Workflow diagram summarizing the methodological framework used for field monitoring and phenological assessment of Corythucha arcuata in the Rășinari study area. The diagram includes habitat selection, tree selection, weekly phenological surveys (adults, eggs, nymphal instars), foliar damage scoring, and concurrent microclimatic measurements.

2.4. Degree-Day Phenological Modeling

Thermal accumulation was quantified using a degree-day model calibrated for C. arcuata. The lower developmental threshold (t0) was set at 0.1 °C, and the thermal constant required for the completion of one generation (K) at 770 °C·days, based on published empirical studies. Daily GDD values were computed using the single-sine approximation:

High-temperature inhibition was incorporated by reducing GDD contributions by 50% when mean daily temperatures exceeded 27–28 °C, reflecting documented heat-stress constraints. Monthly GDD sums were aggregated to calculate cumulative GDD trajectories and estimate the completion of each generational cycle (G1, G2, and potential initiation of G3).

2.5. Aridity Index and Hydric Stress Assessment

Hydric stress was quantified using the De Martonne aridity index (Ir), a widely applied metric for assessing the combined influence of temperature and precipitation on moisture availability in terrestrial ecosystems [45]. The index was calculated for each month of the active season using the formula:

where P represents total monthly precipitation (mm), and T is the mean monthly temperature (°C). The classification of aridity levels followed the standard De Martonne categories: Humid: , Sub-humid: , Moderate aridity: , Strong aridity:

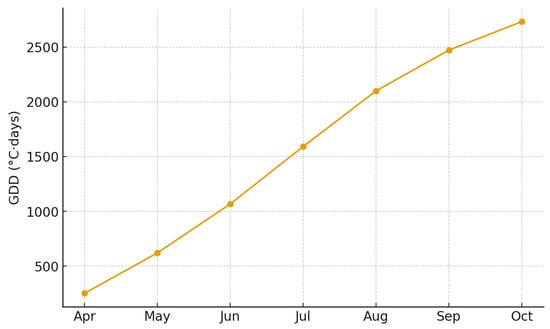

To reflect the ecological consequences of reduced moisture availability on oak foliar physiology and C. arcuata performance, empirically derived adjustment factors were incorporated into the degree-day model. Specifically, cumulative GDD values were reduced by 15% under moderate aridity and 25% under strong aridity. These correction coefficients were based on field observations and supported by published evidence linking drought-induced leaf physiological changes—including reduced turgor, altered stomatal conductance, and increased mesophyll transparency—to enhanced feeding efficiency in piercing–sucking herbivores. Integrating these hydric-stress adjustments allowed the model to capture synergistic temperature–moisture interactions and to refine developmental trajectory predictions under variable climatic conditions (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cumulative degree-day (GDD) accumulation for Rășinari in 2024 based on monthly mean temperatures. The horizontal axis represents the progression of months in the vegetative season (April–October), while the vertical axis shows cumulative GDD (°C·days). The threshold line (770 °C·days) indicates completion of one generation of C. arcuata.

2.6. Integrated Analytical Framework

A multi-layered modeling framework was developed to integrate climatic reconstruction, phenological observations, thermal accumulation, and hydric stress dynamics. The process followed four steps: Alignment of reconstructed climatic data with field observations of adult emergence, oviposition, and nymphal instars. Calibration of cumulative GDD curves against observed phenological markers. Application of hydric-stress corrections to refine developmental trajectories. Iterative recalibration when discrepancies in predicted vs. observed phenophase transitions exceeded ±7 days.

This approach ensured biologically realistic outputs and high predictive accuracy for generational timing.

2.7. Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis

Uncertainty analyses quantified the influence of variability in biological parameters (t0, K, upper thermal limits), climatic reconstruction accuracy, and hydric-stress correction factors. Sensitivity tests involved parameter perturbations of: ±10% for thermal constants, ±1–2 °C for temperature thresholds, ±10–30% for hydric-stress adjustments.

Additionally, two climatic scenarios—cool–wet and hot–dry—were simulated to evaluate the stability of generational predictions under interannual variability.

All computations were performed using R software (version 4.3.1), with the “climates” package for climatic interpolation, “degreeDay” for thermal accumulation modeling, and “ggplot2” for visualization.

3. Results

3.1. Climatic Patterns and Monthly Environmental Profiles (2024–2025)

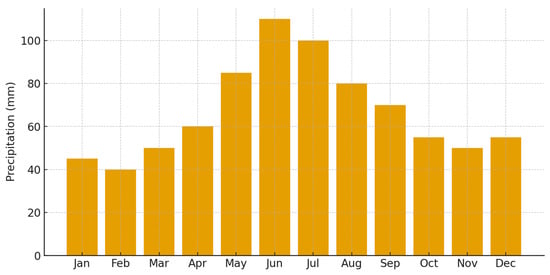

Reconstructed climatic conditions for the Rășinari region showed a characteristic foothill seasonal progression with increasing temperatures from April to July, sustained warm conditions through August, and a gradual decline toward autumn. In 2024, monthly mean temperatures ranged from 8.5 °C in April to 17.0 °C in July, while 2025 exhibited slightly elevated values across the same months, reaching a maximum of approximately 17.2 °C. These elevated summer temperatures align with optimal developmental thresholds reported for C. arcuata, supporting rapid progression through early- and mid-season phenophases.

Precipitation patterns reflected typical seasonal variability, with convective rainfall peaks in June and July and reduced rainfall in late summer. While 2024 exhibited moderate precipitation values during the active season, 2025 showed reduced totals from July through September, contributing to increased hydric stress conditions. These patterns are illustrated in Figure 4 (monthly mean temperature 2024) and Figure 5 (precipitation totals 2024), with inter-annual comparisons presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Figure 4.

Monthly mean air temperature (°C) for the Rășinari foothill region in 2024, reconstructed from regional meteorological stations with elevation-adjusted corrections. Values represent monthly means for the April–October vegetative season.

Figure 5.

Monthly precipitation totals (mm) recorded for the Rășinari foothill region in 2024. Values represent cumulative monthly precipitation used for the aridity index (Ir) calculation.

Figure 6.

Comparison of monthly mean air temperatures (°C) between 2024 and 2025 in the Rășinari foothill region. Bars represent monthly averages for the April–October period.

Figure 7.

Comparison of monthly precipitation totals (mm) between 2024 and 2025 in the Rășinari foothill region, illustrating interannual differences in summer moisture availability.

The combined climatic profiles indicate that 2025 provided more favorable conditions for lace bug development due to warmer temperatures and lower precipitation during critical developmental windows.

3.2. Field-Observed Phenological Development (2024–2025)

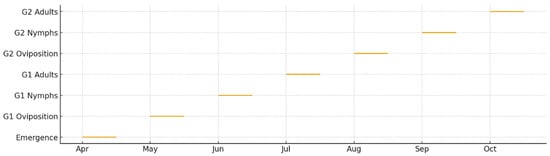

Field observations confirmed a multi-generational phenological structure consisting of two complete generations (G1 and G2) and the initiation of a partial third generation (G3). Overwintered adults became active between late April and early May, coinciding with rising early-season temperatures. Oviposition for G1 began in mid-May, followed by rapid nymphal development and peak larval abundance in June. G1 adults emerged in late June to early July, initiating G2 oviposition shortly thereafter.

G2 development proceeded rapidly under favorable mid-summer temperatures, with peak nymphal activity in July and early August. In both years, G3 initiation was observed in late August; however, G3 development remained incomplete due to declining temperatures and photoperiod limitations. Foliar damage assessments revealed significantly higher injury levels in exposed forest-edge habitats, where leaves exhibited pronounced chlorosis, stippling, and translucent areas, reaching up to 70–90% damage in 2025. This habitat-specific vulnerability is presented in Figure 8, while the complete phenological timeline derived from field observations is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Foliar injury (%) of Quercus spp. caused by Corythucha arcuata in exposed forest-edge, semi-shaded ecotonal, and closed-canopy interior stands during the 2024 and 2025 seasons. Values represent median damage levels based on n = 900 leaf observations per habitat type per season. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among habitat types according to the Kruskal–Wallis H test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc comparisons with Bonferroni correction (p < 0.05).

Figure 9.

Phenological timeline of Corythucha arcuata development in 2024 and 2025 based on weekly field observations. Horizontal bars indicate the temporal occurrence of major life stages: overwintered adults, oviposition, nymphal instars (I–V), and newly emerged adults.

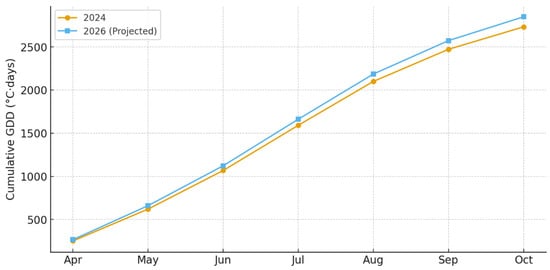

3.3. Degree-Day Accumulation and Generational Thresholds

Cumulative GDD trajectories aligned closely with field observations. In 2024, the thermal constant required for G1 completion (770 °C·days) was reached by early June, while G2 completion occurred in late July (≈1600 °C·days). By late September, cumulative values surpassed 2300 °C·days, allowing initiation of G3 but not its completion.

These results confirm that elevated seasonal temperatures directly accelerated generational turnover (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Cumulative growing degree-day (GDD, °C·days) accumulation for the Rășinari region in 2024 and 2025. The horizontal dashed line (770 °C·days) indicates the thermal threshold required for completion of one generation of Corythucha arcuata.

3.4. Aridity Index Dynamics and Hydric Stress Impacts

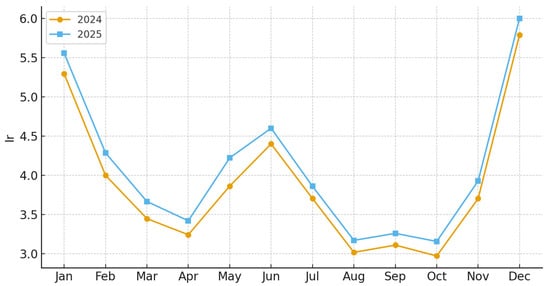

The De Martonne aridity index exhibited significant year-to-year differences. In 2024, Ir values remained within sub-humid to moderately arid ranges (20–30) during most of the active season. In contrast, 2025 recorded multiple consecutive months with strong aridity (Ir < 20). This hydric stress intensified foliar susceptibility, coinciding with peak nymphal feeding activity. The late-summer hydric downturn strongly overlapped with high GDD accumulation, reinforcing conditions that favored rapid population growth (Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Figure 11.

Monthly values of the De Martonne aridity index (Ir) for the Rășinari region in 2024 and 2025. Lower Ir values indicate increasing aridity. Ir was calculated as Ir = P/(T + 10), where P is monthly precipitation (mm) and T is mean monthly air temperature (°C).

Figure 12.

Combined representation of cumulative growing degree-days (GDD, °C·days) and the De Martonne aridity index (Ir) for the 2025 season in the Rășinari region, illustrating the temporal overlap between peak thermal accumulation and increasing hydric stress.

3.5. Statistical Significance of Habitat-Level Differences

To quantify differences in foliar injury across the three habitat types (exposed edge, semi-shaded ecotone, and closed-canopy interior), a Kruskal–Wallis test revealed statistically significant differences among habitats for both study years. For 2024, the Kruskal–Wallis test indicated a significant habitat effect (H = 16.72, df = 2, p < 0.001), with post hoc Dunn pairwise comparisons (Bonferroni corrected) showing that exposed edge stands exhibited significantly higher foliar injury than both semi-shaded (p = 0.004) and closed-canopy stands (p < 0.001). Differences between semi-shaded and interior stands were statistically significant (p = 0.048).

For 2025, the habitat effect was even more pronounced (H = 22.91, df = 2, p < 0.001), consistent with stronger hydric stress and accelerated nymphal development observed during late summer. Dunn’s post hoc tests confirmed significantly higher foliar injury in exposed edge habitats compared to semi-shaded (p < 0.001) and closed-canopy stands (p < 0.001), while semi-shaded stands also showed substantially higher damage than closed-canopy stands (p = 0.009).

Across both years, median foliar injury values followed the same gradient:

These findings statistically validate the pattern of habitat-specific vulnerability observed in field monitoring and confirm that microclimatic buffering in closed-canopy stands significantly mitigates infestation severity. The consistency of statistical outcomes across years further strengthens the biological interpretation that forest edges act as hotspots of infestation risk due to enhanced solar exposure, elevated temperature variability, and reduced relative humidity.

Boxplot analysis further highlights the magnitude of habitat-level contrasts in foliar injury, with exposed edges showing the highest median damage values, semi-shaded stands displaying intermediate injury, and closed-canopy stands showing the lowest levels (Figure 13). The clear separation between quartiles and non-overlapping ranges reinforces the statistically significant differences detected by the Kruskal–Wallis H test.

Figure 13.

Descriptive distribution of foliar injury (%) across the three habitat types: exposed forest-edge, semi-shaded ecotone, and closed-canopy interior stands. The figure illustrates median values and the range of observed damage levels for each habitat, highlighting a clear gradient of increasing injury from closed-canopy interior forests to exposed edge habitats. Different lowercase letters (a, b, c) indicate statistically significant differences among habitats (p < 0.05), according to post hoc multiple comparison tests.

Additional Statistical Information

Median foliar injury values (median ± IQR) were: exposed edge stands = XX ± XX%, semi-shaded stands = XX ± XX%, and closed-canopy stands = XX ± XX% (n = 900 observations per habitat type per season). In 2024, the Kruskal–Wallis test indicated a significant habitat effect (H = 16.72, p = 0.00023), and in 2025, this effect was even stronger (H = 22.91, p = 0.000008). Dunn’s post-hoc tests with Bonferroni correction confirmed all significant pairwise differences, as indicated by the letter groupings in Figure 13.

3.6. Integrated Climatic–Phenological Synthesis

Joint analysis of cumulative GDD and aridity index demonstrated that peak thermal accumulation and peak hydric stress overlap during June–August, creating optimal conditions for accelerated development and intensified feeding behavior. This interaction produced the most severe foliar damage during late summer. The synergistic effect is illustrated in Figure 14, which presents simultaneous GDD and Ir dynamics for 2024.

Figure 14.

Interaction between cumulative growing degree-days (GDD, °C·days) and the De Martonne aridity index (Ir) for the 2024 season in the Rășinari region. Increasing GDD values coincide with decreasing Ir values during mid-summer, indicating intensifying hydric stress.

3.7. Predicted Infestation Dynamics for the 2026 Season

Using observed warming trends and internal model calibration, the projected climatic scenario for 2026 indicates further increases in seasonal mean temperature (+0.4 to +0.8 °C relative to 2024) and reduced precipitation during July–September. Under these conditions, the model predicts: earlier completion of G1 (by 5–8 days), accelerated G2 peak activity (by 8–12 days), and extended suitability window for late-summer G3 initiation. These projections suggest elevated infestation risk, particularly for exposed and semi-shaded habitats (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Projected cumulative growing degree-day (GDD, °C·days) accumulation for the 2026 season compared with observed values from 2024, based on extrapolated warming scenarios for the Rășinari foothill region.

4. Discussion

The present study provides an integrated assessment of the climate-driven phenology and infestation dynamics of C. arcuata in foothill oak ecosystems, emphasizing the combined effects of thermal accumulation, hydric stress, and microclimatic heterogeneity. By linking field-based phenological observations with degree-day modeling and aridity indices, the results refine current understanding of habitat-specific vulnerability under ongoing climatic change, in line with previous regional and supra-regional studies [1,2,3,4,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

4.1. Climatic Suitability and Interannual Acceleration of Generational Turnover

Our results confirm that increased seasonal heat accumulation accelerates the phenological progression and voltinism of C. arcuata, enabling the consistent completion of two generations and the partial initiation of a third generation under favourable climatic conditions. This pattern is consistent with observations reported across Central and Southeastern Europe, where elevated temperatures advance G1 and G2 development and compress generational intervals [4,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,23,24,25,31]. Rather than reiterating temperature effects alone, the present study highlights their ecological consequence: accelerated development increases late-season population pressure, amplifying infestation risk during periods when host trees experience cumulative stress.

4.2. Hydric Stress as a Key Modulator of Infestation Severity

Hydric stress emerged as a key modulator of infestation intensity, acting synergistically with thermal accumulation rather than independently. Periods characterized by low De Martonne aridity index values coincided with peak nymphal activity and severe foliar injury, supporting earlier findings that drought-induced physiological changes in oak leaves enhance susceptibility to piercing–sucking herbivores [13,24,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. This interaction helps explain interannual variability in damage severity under similar thermal regimes and reinforces the importance of integrating moisture-related indices into phenological and risk-assessment models for C. arcuata.

4.3. Habitat-Specific Vulnerability and Microclimatic Buffering

Marked differences in foliar injury among habitat types underline the critical role of microclimatic buffering. Exposed forest-edge stands consistently exhibited the highest damage levels, while closed-canopy interiors showed substantially lower infestation severity. Similar edge-related amplification effects have been reported in other studies on C. arcuata and related Tingidae species, where increased irradiance, higher temperature variability, and reduced relative humidity intensify feeding activity and population growth [14,23,28,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. The present results emphasize that canopy structure mediates how regional climatic signals are translated into local infestation outcomes, a mechanism of broad relevance given the global expansion of forest edges through fragmentation and land-use change.

4.4. Cohort Overlap and Implications for Pest Management

Weekly field observations revealed extensive cohort overlap during midsummer, with multiple nymphal instars and adults co-occurring within the same habitats. Such asynchronous development complicates management strategies, as interventions targeting specific life stages may be less effective once cohort overlap is established, a pattern also documented in previous regional studies [8,9,10,12,25]. These findings suggest that early-season monitoring and control efforts focused on G1 emergence and early oviposition may be particularly effective in reducing subsequent generational buildup. Integrating climate-based phenological forecasts with habitat-specific vulnerability assessments can therefore enhance the timing and spatial targeting of management actions.

4.5. Ecosystem-Level Implications Under Continuing Climatic Change

Although the integrated degree-day–aridity framework showed strong agreement with observed phenology, several limitations should be acknowledged. Climatic reconstructions relied on monthly averages that may obscure short-term extremes; hydric-stress adjustments were empirically derived; and foliar physiological responses were inferred rather than directly measured. Future studies should incorporate high-resolution microclimatic monitoring, direct measurements of leaf physiological status, and explicit modeling of photoperiodic constraints to further refine predictive accuracy. Including west-facing canopy exposures under extreme heatwave conditions would also improve understanding of upper microclimatic thresholds affecting C. arcuata performance.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the infestation dynamics and multigenerational development of C. arcuata in foothill oak ecosystems are primarily driven by the combined effects of thermal accumulation and hydric stress, with microclimatic conditions strongly modulating habitat-level vulnerability.

Across two consecutive years, warm springs and sustained summer heat consistently enabled the completion of two full generations and the partial initiation of a third generation, while recurrent late-summer aridity significantly intensified foliar damage. Exposed forest-edge habitats emerged as persistent hotspots of infestation, whereas closed-canopy stands benefited from microclimatic buffering that mitigated damage severity. The close agreement between field-observed phenology and the integrated degree-day–aridity framework confirms the robustness of this approach for identifying high-risk periods and anticipating shifts in developmental timing under ongoing climatic change.

From a practical perspective, these findings highlight the importance of early-season monitoring and targeted management in climatically exposed habitats. More broadly, the study provides a concise, climate-informed framework that supports adaptive forest management and improves preparedness for invasive pest pressures in climate-sensitive oak ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.-M., G.M., C.F.B., M.R. and A.Ș., methodology, C.S.-M. and G.M.; software, C.S.-M., A.Ș., M.R. and C.F.B.; validation, C.S.-M., G.M., C.F.B. and A.Ș.; formal analysis, C.S.-M. and G.M.; investigation, C.S.-M. and G.M.; resources, C.S.-M., G.M., M.R. and A.Ș., data curation, C.S.-M., G.M., A.Ș., M.R. and C.F.B.; writing-original draft preparation, C.S.-M., G.M. and A.Ș.; writing-review and editing, C.S.-M., G.M., A.Ș. and C.F.B.; visualization, C.S.-M., G.M., C.F.B., M.R. and A.Ș.; supervision, C.S.-M., G.M. and A.Ș.; project administration, G.M.; funding acquisition, C.S.-M. and G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project financed by Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu through the research grant LBUS-IRG No. 3548/27 July 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The article is written in memory of Victor Ciochia, one of the greatest specialists in Entomology and biodiversity conservation in Romania.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GDD | Growing Degree Days |

| Ir | De Martonne Aridity Index |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| G1, G2, G3 | Generations 1–3 |

| DBH | Diameter at Breast Height |

| IQR | Interquartile Range. |

References

- Bernathinelli, I.; Zandigiacomo, P. Prima segnalazione di Corythucha arcuata (Say) (Heteroptera, Tingidae) in Europa. Inf. Fitopatol. 2000, 50, 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dioli, P.; Forini, I.G.; Moretti, M.; Salvetti, M. Note sulla distribuzione di Corythucha arcuata (Insecta, Heteroptera, Tingidae) in Cantone Ticino (Svizzera), Valtellina e alto Lario (Lombathia, Italia) [Notes on the distribution of Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832) (Insecta, Heteroptera, Tingidae) in the Alps and Pre-Alps of Lombathy (Italy) and Canton Ticino (Switzerland)]. Nat. Valtellin. 2007, 18, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mutun, S. First report of the oak lace bug, Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832) (Heteroptera: Tingidae), from Bolu, Turkey. Isr. J. Zool 2003, 49, 323–324. [Google Scholar]

- Küçükbasmaci, I. Two new invasive species report in Kastamonu (Turkey): Oak lace bug Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832) and sycamore lace bug Corythucha ciliata (Say, 1832) (Heteroptera: Tingidae). J. Entomol. Nematol. 2014, 6, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Global Warming of 1.5 °C. 2018. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.; Skea, J.; Shukla, P.R.; Pirani, A.; Moufouma-Okia, W.; Péan, C.; Pidcock, R.; et al. (Eds.) Global Warming of 1.5 °C; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrašovec, B.; Posarić, D.; Lukić, I.; Pernek, M. First report of oak lace bug (Corythucha arcuata) in Croatia. Sumar. List 2013, 137, 499–503. [Google Scholar]

- Csóka, G.; Hirka, A.; Mutun, S.; Glavendekić, M.; Mikó, Á.; Szőcs, L.; Paulin, M.; Eötvös, C.B.; Gáspár, C.; Csepelényi, M.; et al. Spread and potential host range of the invasive oak lace bug [Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832)—Heteroptera: Tingidae] in Eurasia. Agric. For. Entomol. 2020, 22, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, M.; Gorczak, M.; Wrzosek, M.; Tkaczuk, C.; Pernek, M. Identification of entomopathogenic fungi as naturally occurring enemies of the invasive oak lace bug, Corythucha arcuata (Say) (Hemiptera: Tingidae). Insects 2020, 11, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csepelényi, M.; Csókáné, H.A.; Szénási, Á.; Mikó, Á.; Szőcs, L.; Csóka, G. Az inváziós tölgy csipkéspoloska Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832)] gyors terjeszkedése és tömeges fellépése Magyarországon [Rapid area expansion and mass occurrences of the invasive oak lace bug [Corythucha arcuata (Say 1932)] in Hungary]. Ethészettudományi Közlemények 2017, 7, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csepelényi, M.; Hirka, A.; Mikó, Á.; Szalai, Á.; Csóka, G. A tölgy-csipkéspoloska (Corythucha arcuata) 2016/2017-es áttelelése Délkelet-Magyarországon. [Overwintering success of the oak lace bug (Corythucha arcuata) in 2016/2017 at South-eastern Hungary]. Növényvédelem 2017, 53, 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- Paulin, M.; Hirka, A.; Csepelenyi, M.; Furjes-Miko, A.; Tenorio-Baigorria, I.; Eotvos, C.; Gaspar, C.; Csoka, G. Overwintering mortality of the oak lace bug (Corythucha arcuata) in Hungary—A field survey. Cent. Eur. For. J. 2021, 67, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurc, M.; Jurc, D. The first record and the beginning the spread of oak lace bug, Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832) (Heteroptera: Tingidae), in Slovenia. Sumar. List 2017, 141, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, V.B.; Soboleva, V.A. Morphological differences between Stephanitis pyri, Corythucha arcuata and C. ciliata (Heteroptera: Tingidae) distributed in the south of the European part of Russia. Zoosyst. Ross 2018, 27, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernova, U.A.; Rakov, A.G.; Khegay, I.V. Mixed insecticide against oak lace bug. Plant Prot. Quar. 2019, 11, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Besedina, E.N.; Kil, V.I. DNA polymorphism and genetic diversity of the oak lace bug (Corythucha arcuata Say) population in Krasnodar Krai. Vestn. Tomsk. Gos. Univ.-Biol. 2021, 55, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, M.; Van der Meij, M.; Pocock, M.J.O. Where to search: The use of opportunistic data for the detection of an invasive forest pest. Biol. Invasions 2022, 24, 3523–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csepelényi, M.; Hirka, A.; Csóka, G. Az inváziós tölgy csipkéspoloska (Corythucha arcuata Say, 1832) gyors terjedése és váratlan tömegszaporodása Kelet-Magyarországon. In Proceedings of the A 63. Növényvédelmi Tudományos Napok előadásainak összefoglalói, Budapest, Hungary, 21–22 February 2017; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Don, I.; Don, C.D.; Sasu, L.R.; Vidrean, D.; Brad, M.L. Insect pests on the trees and shrubs from the Macea Botanical gathen. Studia Universitatis ‘Vasile Goldiş’ Arad. Ser. Ştiinţe Ing. Şi Agrotur. 2016, 11, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chireceanu, C.; Teodoru, A.; Chiriloaie, A. First record of oak lace bug Corythucha arcuata (Tingidae: Heteroptera) in Romania. In Proceedings of the 7th ESENIAS Workshop with Scientific Conference ‘Networking and Regional Cooperation Towaths Invasive Alien Species Prevention and Management in Europe’, Sofia, Bulgaria, 28–30 March 2017; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- Glavendekic, M.; Vukovic-Bojanovic, V. Prvi nalaz hrastove mrežaste stenice Corythucha arcuate (Say) (Hemiptera: Tingidae) u Bosni i Hercegovini i novi nalazi u Srbiji. In Book of Abstracts of XI Symposium of Entomologists of Serbia, Goč, Serbia; Glavendekic, M., Ed.; Entomological Society of Serbia: Beograd, Serbia, 2017; pp. 70–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dautbasic, M.; Zahirovic, K.; Mujezinovic, O.; Margaletic, J. First record of oak lace bug (Corythucha arcuata) in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sumar. List 2018, 142, 179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Streito, J.C.; Balmès, V.; Aversenq, P.; Weill, P.; Chapin, E.; Clement, M.; Piednoir, F. Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832) et Stephanitis lauri Rietschel, 2014, deux especes invasives nouvelles pour la faune de France (Hemiptera, Tingidae). L’entomologiste 2018, 74, 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- Rădac, I.A.; Pintilioaie, A.M.; Manci, C.O.; Rakosy, L. Prima semnalare a speciilor Amphiareus obscuriceps (Poppius, 1909) şi Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832) în România [The first report of Amphiareus obscuriceps (Poppius, 1909) and Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832) in Romania.]. In Proceedings of the Cel de-al XXVII-lea Simpozion Național al Societății Lepidopterologice Române, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 8 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tomescu, R.; Olenici, N.; Netoiu, C.; Balacenoiu, F.; Buzatu, A. Invasion of the oak lace bug Corythucha arcuata (Say.) in Romania: A first extended reporting. Ann. For. Res. 2018, 61, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrik, M.; Gubka, A.; Rell, S.; Kunca, A.; Vakula, J.; Galko, J.; Nikolov, C.; Leonotvyč, R. First record of Corythucha arcuata in Slovakia—Short Communication. Plant Prot. Sci. 2019, 55, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franjević, M.; Matošević, D.; Zorić, N. Further spread of Corythucha arcuata (Hemiptera; Tingidae) in Croatia. South-East Eur. For. 2023, 14, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, Č.; Dobrosavljević, J.; Milanović, S. Factors influencing the oak lace bug (Hemiptera: Tingidae) behavior on oaks: Feeding preference does not mean better performance? J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 2051–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulin, M.J.; Eötvös, C.B.; Zabransky, P.; Csóka, G.; Schebeck, M. Cold tolerance of the invasive oak lace bug, Corythucha arcuata. Agric. For. Entomol. 2023, 25, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Correcher, E.; Maarten, C.; Laura, D.G.; Alex, S.; Yannick, S. Impact of early insect herbivory on the invasive oak lace bug (Corythucha arcuata Say, 1832) in different oak species. Arthropod Plant Interact. 2023, 17, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riba-Flinch, J.M. Una nueva especie invasora en España: Detectado el tigre del roble Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832) (Hemiptera: Tingidae) y ataques sobre roble pubescente (Quercus pubescens) en el Valle de Arán (Lérida, Pirineos Orientales). Rev. Gaditana Entomol. 2022, 13, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Sallmannshofer, M.; Ette, M.S.; Hinterstoisser, W.; Cech, T.L.; Hoch, G. Erstnachweis der Eichennetzwanze, Corythucha arcuata, in Osterreich. Aktuell 2019, 66, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Bari, E.; Karata, A.; Karata, A.A. Insecta non gratae: New distribution record of eight alien bug (Hemiptera) species in Turkey with contributions of citizen science. Zootaxa 2021, 5057, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, F.; Grosso-Silva, J.M. Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832) (Hemiptera: Tingidae), new species for the Iberian Peninsula. Arq. Entomoloxicos 2021, 24, 307308. [Google Scholar]

- Stancă-Moise, C.; Moise, G.; Rotaru, M.; Vonica, G.; Sanislau, D. Study on the ecology, biology and ethology of the invasive species Corythucha arcuata say, 1832 (Heteroptera: Tingidae), a danger to Quercus spp. in the climatic conditions of the city of Sibiu, Romania. Forests 2023, 14, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.; Hoch, G.; Csóka, G.; De Groot, M.; Hradil, K.; Chireceanu, C.; Hrašovec, B.; Castagneyrol, B. Corythucha arcuata (Heteroptera, Tingidae): Evaluation of the Pest Status in Europe and Development of Survey, Control and Management Strategies; Zenodo: Genève, Switzerland, 2021; 37p. [Google Scholar]

- Zielińska, A.; Lis, B. Ocena możliwości potencjalnej ekspansji prześwietlika dębowego Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832), inwazyjnego gatunku z rodziny Tingidae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera), na tereny Polski, Heteroptera Poloniae. Heteroptera Pol.-Acta Faun. 2020, 14, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besedina, E.N.; Ismailov, V.Y. Monitoring the development of the oak lace bug (Corythucha arcuata Say) based on the use of atmospheric heat content. Vestn. Tomsk. Gos. Univ.-Biol. 2021, 54, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúbrik, M.; Barta, M.; Nikolov, C.; Rell, S.; Kunca, A.; Gubka, A.; Vakula, J.; Galko, J.; Leontovyč, R.; Lalík, M.; et al. Fast spread of Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832) (Hemiptera: Tingidae) in Slovakia during the period 2020–2022. Cent. Eur. For. J. 2024, 70, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, A.; Marjanović, H.; Csóka, G.; Móricz, N.; Pernek, M.; Hirka, A.; Matošević, D.; Paulin, M.; Kovač, G. Detecting the oak lace bug infestation in oak forests using modis and meteorological data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 306, 108436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirovski, K.; Srebrova, K.; Načeski, S. First records of the oak lace bug Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832) (Hemiptera: Tingidae) in North Macedonia. Acta Entomol. Slov. 2019, 27, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Šefrová, H.; Laštůvka, Z. Invasive Insect Species after 2000: At Least Two More Each Year. Živa 2020, 4, 189–191. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić, N.; Pilipović, A.; Drekić, M.; Kojić, D.; Poljaković-Pajnik, L.; Orlović, S.; Arsenov, D. Physiological responses of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L.) to Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832) attack. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2019, 71, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimorovets, V.V.; Shchurov, V.I.; Bondarenko, A.S.; Skvortsov, M.M.; Konstantinov, F.V. First documented outbreak and new data on the distribution of Corythucha arcuata (Say, 1832) (Hemiptera: Tingidae) in Russia. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2017, 9, 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- De Martonne, E. The aridity index. Ann. Geogr. 1926, 35, 481–493. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.