Abstract

Traditional Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) often provides single-point estimates that lack the statistical rigour required for high-stakes investment decisions in the agri-food sector. To bridge the gap between data uncertainty and actionable management, this study proposes a robust decision-support framework integrating Monte Carlo uncertainty analysis with inferential statistics (ANOVA and Tukey HSD). We applied this methodology to the industrial production of Dictyophora rubrovolvata, a climate-sensitive crop representing the “energy–food nexus.” The study aimed to distinguish genuine environmental performance differences from background data variability. The probabilistic modelling revealed that electricity consumption is the paramount ecological hotspot. Furthermore, the statistical tests confirmed that differences in regional grid composition generate significant variances in impact categories (p < 0.001), validating that the environmental benefits of low-carbon grids are systematic and robust. By transforming complex uncertainty data into clear statistical hierarchies, this framework enables producers and policymakers to identify and prioritise high-impact sustainability levers with confidence, providing a generalisable blueprint for the environmental management of energy-intensive agricultural systems.

1. Introduction

Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), requires a fundamental transformation of global agri-food systems to mitigate climate change and reduce environmental degradation. As the global population continues to expand, pressure mounts to intensify agricultural production. However, this intensification, particularly within energy-intensive controlled-environment agriculture (CEA), often drives a surge in greenhouse gas emissions and resource depletion. This trend creates a direct conflict with international climate targets, such as those outlined in the Paris Agreement, and national ambitions for achieving carbon neutrality. For nations like China, which have pledged ambitious “dual carbon” goals, reconciling the growth of modern agriculture with these commitments is a paramount challenge.

Speciality mushroom cultivation represents a compelling microcosm of the energy–food nexus. With global production exceeding 48 million tonnes in 2021 [1] the industry’s scale is significant. On one hand, it exemplifies a circular economy model, converting agricultural residues into high-value protein sources [2] and bolstering rural economies. However, a critical trade-off exists. Its industrial-scale reliance on climate control and substrate sterilisation renders the sector highly energy-intensive. This creates a tight coupling between food output and energy input. Consequently, the sector’s environmental footprint is critically dependent on the regional energy infrastructure. Therefore, developing a robust methodology to navigate this nexus is not merely an internal challenge for the mushroom industry; it provides a valuable and generalisable blueprint for a wide array of emerging high-tech agricultural systems.

To operationalise this blueprint, this study focuses on Dictyophora rubrovolvata (also known as Phallus rubrovolvatus) as a strategic case study. Selected for its dual economic and physiological significance, this crop is recognised as the ‘Queen of mushrooms’ and serves as a characteristic pillar industry for rural revitalisation in Southwest China [3]. Crucially, unlike robust conventional fungi, D. rubrovolvata demands precise thermal regulation; while the biological optimum ranges from 18 to 25 °C, industrial facilities typically target a strict 21–22 °C for stability [4]. This narrow tolerance makes its production exceptionally sensitive to energy inputs. This strict microclimate requirement transforms it into an ideal model organism for dissecting the ‘energy–food nexus’ and evaluating decarbonisation strategies.

However, applying rigorous environmental assessment to such specialised systems faces three critical barriers. First, existing LCA literature exhibits significant methodological limitations when applied to precision agriculture. While foundational studies, such as Leiva et al [5] and Dorr et al [6], focusing on substrate burdens, and Goglio et al. [2] on broader system hotspots, have correctly identified energy and raw materials as critical drivers, they predominantly utilise deterministic models with static emission factors. These approaches fail to capture the stochastic nature of critical variables, such as the yield instability inherent to biological systems or fluctuations in grid intensity. Consequently, producers of niche, climate-sensitive crops are forced to rely on generic proxies that mask the true range of environmental risks. This data gap creates a high risk of maladaptation. Specifically, capital may be misallocated to suboptimal strategies, resulting in wasted resources rather than meaningful environmental benefits.

Second, the decisive influence of regional electricity grid heterogeneity, the direct interface between farm-level operations and national energy policy, has not been rigorously quantified. This omission creates a strategic blind spot for both producers planning their energy procurement and policymakers seeking to evaluate the specific agricultural co-benefits of regional energy transitions.

Finally, and most critically, traditional deterministic LCA models provide only single-point estimates, which offer an insufficient and potentially misleading basis for high-stakes investment decisions. Although Monte Carlo simulations are increasingly applied in LCA to assess parameter uncertainty, they are rarely integrated with formal hypothesis testing (e.g., ANOVA) to compare mitigation strategies in the agricultural sector rigorously. This methodological disconnection leaves a crucial question unanswered for managers and policymakers: is a projected benefit statistically significant, or merely an artefact of data variability? Without bridging quantitative uncertainty analysis with inferential statistics, true evidence-based environmental management remains elusive.

This study addresses these critical management and policy challenges by developing and applying a statistically robust environmental assessment framework to a commercial D. rubrovolvata facility in Guizhou, China. Our goal is to translate complex environmental data into a clear, actionable decision-support tool. To achieve this, we pursue three objectives: (1) To move beyond generic conclusions by conducting a cradle-to-gate LCA, integrated with quantitative uncertainty analysis, to identify and rank the primary, context-specific environmental management hotspots. (2) To use formal statistical hypothesis testing (ANOVA with Tukey HSD) to rigorously evaluate the environmental performance of different electricity sourcing scenarios, thereby providing reliable, evidence-based guidance on the single most impactful management lever. (3) To deliver a transparent and replicable methodological framework. This framework bridges the gap between farm-level operational decisions and macro-level sustainability policy, supporting strategic planning and a genuine green transition for energy-intensive agricultural enterprises.

2. Methodology

The environmental performance of the D. rubrovolvata production system was evaluated following the ISO 14040/14044 [7,8] standards for Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). The methodology was specifically structured to serve as a quantitative foundation for identifying and validating management strategies for environmental improvement.

2.1. Goal and Scope: Defining the Management Context

The primary goal of this study was to equip the facility’s managers with a quantitative tool to identify and prioritise the most effective environmental improvement actions. The functional unit (FU), the basis for comparing all results, was defined as “the cultivation of 1 kg of fresh D. rubrovolvata mushrooms”.

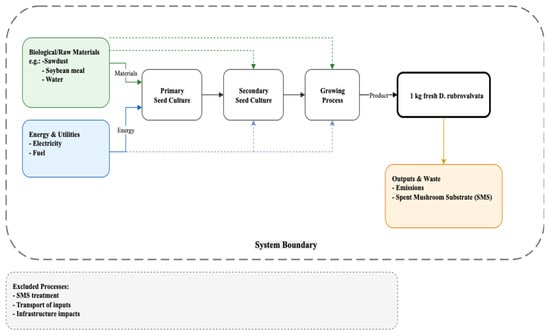

The system boundary was established as “cradle-to-gate” (Figure 1), encompassing all activities from the acquisition of raw materials to the point where fresh mushrooms are packaged and ready for shipment. This boundary was intentionally chosen to cover all processes under the direct or indirect control of the facility’s management, ensuring that the results are directly relevant to their operational and procurement decisions.

Figure 1.

Cradle-to-gate system boundary of D. rubrovolvata production.

To rigorously justify excluding raw material transportation from the system boundary, we conducted a screening-level sensitivity analysis. This involved modelling a worst-case scenario: a transportation distance of 500 km for all bulk substrates (sawdust and wheat bran) via heavy-duty diesel lorries. The results indicate that even under these extreme logistical assumptions, transportation contributes less than 3.0% to the total GWP. This confirms that the environmental profile of D. rubrovolvata production is overwhelmingly dominated by on-site energy consumption (which accounts for >88% of GWP), validating the focus on cradle-to-gate energy flows.

2.2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

Site-specific primary data for all foreground processes, including substrate preparation, cultivation, harvesting, and packaging, were collected directly from a commercial facility in Guizhou, China (Table 1). This facility was strategically selected to reflect the standard technological baseline of the region’s expanding industrial agriculture sector. It employs the standardised climate control infrastructure (automated electric-driven HVAC systems) and substrate formulations (sawdust and wheat bran mix) that characterise modern D. rubrovolvata cultivation in Southwest China. Consequently, while the primary data are derived from a single site, its operational parameters, particularly the energy intensity of the microclimate regulation systems, serve as a robust proxy for the typical environmental performance of this specific agricultural sector.

Table 1.

Raw material inputs for producing 1 kg of fresh D. rubrovolvata.

Data for background processes, such as the production of upstream materials (e.g., glucose, bran) and energy generation, were sourced from the Ecoinvent v3.9.1 [9] database. Recognising that energy sourcing is a critical variable, the electricity mix was specifically modelled to represent the Guizhou provincial grid alongside other relevant regional grids in China for comparative analysis.

2.3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

This study focuses on assessing the environmental performance of D. rubrovolvata production, adopting a cradle-to-gate model. The functional unit of this research is defined as the production of 1 kg of fresh D. rubrovolvata. The approach to data quality and uncertainty management in this study follows the methodological framework of the official SimaPro 9.5 manual [10] and the requirements of ISO 14044 [7,8]. Ten relevant impact categories were selected for this research based on their common usage in analysing the environmental impact of mushroom production [2,6,11,12,13,14]. The detailed list of these categories, including their abbreviations, reference units, and descriptions, is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Selected impact categories, units, and descriptions used in this study.

The selection of these categories, particularly GWP100, AC, and EU, directly aligns with China’s key environmental policy priorities, such as the ‘Dual Carbon’ goals (peaking carbon emissions by 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060) and national strategies for pollution control and water quality protection [15,16,17]. Moreover, the research aims to evaluate the environmental contributions of each phase of production, including the preparation of the primary seed culture, the preparation of the secondary seed culture, and the growing process, and to identify potential improvements by analysing environmental hotspots.

The CML-IA baseline V3.09 method [18] was used to characterise environmental impacts at the midpoint level. This method was selected for its recognised objectivity and robustness as well as its higher frequency in mushroom studies in the scientific literature [2,11,18,19]. While endpoint methods, such as ReCiPe, provide a more aggregated, damage-oriented perspective, the CML midpoint approach was chosen here to avoid the additional uncertainties and value-based weighting inherent in endpoint modelling, thereby providing a more transparent analysis of specific environmental mechanisms. To translate qualitative data-quality judgments into quantitative uncertainty for probabilistic propagation, this study applied the pedigree matrix approach, as introduced by Weidema and Wesnæs [20], Weidema [21], and later consolidated within the ecoinvent framework. In this application, each of the eleven LCI parameters was scored across five dimensions: reliability, completeness, temporal correlation, geographical correlation, and technological correlation. Scores range from 1 (best) to 5 (worst), representing a greater potential deviation between the recorded value and the unobservable true system mean. For each dimension–score combination, the pedigree matrix provides a corresponding geometric uncertainty factor (UFj ≥ 1). These factors are then combined to establish the overall geometric standard deviation (GSD) for the parameter. All data visualisation was performed in RStudio (version 4.5.1) [22] using the ggplot2 package [23].

2.3.1. Uncertainty Characterisation Framework

The input data were obtained from a single factory during one production period, which constrains representativeness and increases uncertainty. Accordingly, a pedigree matrix approach was applied to derive empirically grounded uncertainty factors. A five-dimensional pedigree matrix operationalised qualitative data-quality judgments into quantitative multiplicative factors. For each LCI parameter, reliability, completeness, temporal correlation, geographical correlation, and technological correlation were scored on an ordinal 1–5 scale (1 = best evidence; 5 = weakest). Every (dimension, score) pairing is associated with a geometric uncertainty factor UF ≥ 1 that quantifies the dispersion attributable to that deficiency. A base (irreducible) uncertainty factor Ub = 1.05 was elicited via expert judgement and introduced to encode residual variability for best quality observations. Foundational pedigree references [22,23] define the qualitative dimensions and the multiplicative aggregation rule but do not prescribe a universal base factor. Hence Ub = 1.05 was selected and empirically calibrated against high quality measurement subsets (typical CV = 3–6%), placing it near the lower bound of dispersion values reported in previous applications.

The approach to data quality and uncertainty management in this study follows the methodological framework of the official SimaPro manual [10] and the requirements of ISO 14044 [7,8]. Each foreground input and emission was assessed using the five-dimensional pedigree matrix; scores (1–5) were mapped to geometric standard-deviation multipliers, treated consistently as uncertainty factors (UF ≥ 1). The resulting total geometric standard deviation is calculated according to Equation (1) and then converted to the log-normal parameters σ and μ (Equations (2) and (3)). In this study, all non-negative, right-skewed variables (e.g., emission factors, material consumption, background emissions) are modelled as log-normal distributions.

2.3.2. Monte Carlo Simulation Setup

Monte Carlo Simulation for LCA

We conducted n = 1000 Monte Carlo iterations in SimaPro to propagate parameter uncertainty. A pilot run (500 vs. 1000 iterations) showed that the relative differences in mean impact category results were <0.2%, and changes in the coefficient of variation (CV; Equation (4)) were <0.1 percentage points. Increasing the number of iterations to 5000 produced only a marginal reduction in the standard error of the mean (Equation (5)), insufficient to justify the additional computational cost. Each input parameter was sampled independently from its assigned distribution. Cross-process correlations were not explicitly modelled, which may slightly underestimate the joint output variance. For each impact category, we report the mean, median, standard deviation, CV, the empirical 95% (2.5–97.5%) interval and its relative half-width (RHW) (Equation (6)) for robustness appraisal.

Monte Carlo Simulation for Sensitivity Analysis

To quantify the uncertainty in each scenario and assess the robustness of the comparison results, we performed 1000 Monte Carlo simulations for each of the six scenarios. For each environmental impact category c and scenario s, we calculated the mean impact value μc,s and standard deviation c,s. The internal uncertainty of each result was then quantified using the CVc,s (Equation (7)).

To systematically evaluate the discriminative power of each impact category, we formulated a Discriminative Index (DI) based on the signal-to-noise principle (Equation (8)). This index is conceptually analogous to the F-statistic in ANOVA but utilises the coefficient of variation (CV) to assess the relative magnitude of variation. It quantifies the ratio of the between-scenario variability (the signal) to the average within-scenario uncertainty (the noise). This approach enables a robust, scale-independent comparison across different impact categories to identify which ones serve as reliable differentiators between the evaluated scenarios.

* Each UFj comprise the base reference uncertainty factor Ub and the five pedigree dimension factors (reliability, completeness, temporal correlation, geographical correlation, and technological correlation).

μ = ln(m)

X = exp(μ + Zσ), Z∼N(0,1)

2.4. Sensitivity Analysis Method

To assess the sensitivity of the environmental profile to electricity sourcing, a scenario analysis was conducted that accounts for the significant regional heterogeneity in China’s electricity generation infrastructure. Four distinct scenarios were developed by replacing the model’s original electricity input, which was based on the Southwest grid mix.

These scenarios utilised specific regional grid mix datasets from the ecoinvent v3.9.1 database [9], employing the “Cut-off by classification” system model. The datasets correspond to the operational areas of China’s main regional power grids: Northeast China (NECG), East China (ECGC), Central China (CCG), Northwest China (NWG), and Southwest China (SWG). To ensure a comparable basis for the analysis, the total electricity consumption per functional unit was held constant across all scenarios.

The results for ten impact categories across five scenarios were generated through 1000 Monte Carlo iterations, yielding a distribution for each outcome characterised by a mean and standard deviation. Due to this inherent variability, a direct comparison of mean values is insufficient for drawing robust conclusions, as it cannot distinguish between genuine systematic differences and random statistical noise. To address this, a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed for each impact category. The primary purpose of the ANOVA was to test whether the variance between the scenario groups was significantly greater than the variance within them.

Following a significant ANOVA result (p < 0.05), which indicates that at least one scenario differs from the others, Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc test was conducted to perform all pairwise comparisons. This procedure ensures that specific conclusions about which scenarios outperform others are drawn while controlling for the family-wise error rate. Additionally, effect sizes were calculated using eta-squared (η2) to assess the practical significance of the observed differences. This metric measures the proportion of the total variance in the impact scores that is attributable to the choice of scenario. This comprehensive statistical approach allowed for a robust differentiation of scenario performances, moving beyond simple rankings to identify differences that are both statistically significant and practically meaningful.

3. Results

3.1. Pedigree Dimensions and Scoring

Table A1 presents the life cycle inventory (LCI) data quality indicators: reliability, completeness, temporal correlation, geographical correlation, and technological correlation, scored using the 1–5 ordinal pedigree scale adopted in this study (1 = highest quality; 5 = lowest). Table 3 summarises the pedigree matrix assessment results. The researcher and the stakeholder recorded the results separately, and then held a discussion to resolve any discrepancies. Overall, the assessment confirms that the data are highly representative in terms of time and geography. However, its completeness and reliability are limited by its reliance on single-source data and estimated allocations for key inputs like electricity, gasoline, and water. The modelling approach improves data comparability at the cost of hiding process-level details. Additionally, the inputs with the lowest reliability (electricity, gasoline, and water) are also the largest drivers of the model’s overall quantitative uncertainty, a structural consequence of how their data is metered and allocated.

Table 3.

Results of the pedigree matrix assessment for D. rubrovolvata production.

3.2. Monte Carlo Simulation

This study employed Monte Carlo simulation (n = 1000 iterations) to assess the model’s response to parameter uncertainty. A detailed statistical summary—including the mean, median, standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variation (CV), 95% confidence intervals, and relative half-width (RHW)—is presented for each impact category in Table 4.

Table 4.

Statistical summary of Monte Carlo simulation results (n = 1000) for environmental impact categories.

The results demonstrate high overall robustness across all impact categories. Key categories such as GWP100, AC, and EU exhibited low coefficients of variation (2–5%). Similarly, OLD also showed high stability with a CV of 3.03%, indicating that the model is robust to parameter uncertainty across the full spectrum of environmental impacts.

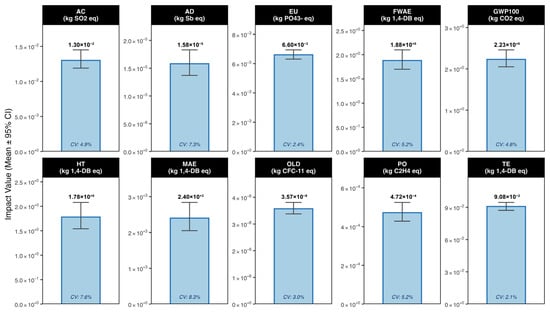

Figure 2 presents the probabilistic results for the ten impact categories. The bar charts display the mean values with error bars representing the 95% confidence intervals derived from 1000 Monte Carlo iterations.

Figure 2.

Environmental impact assessment results. The chart displays the mean values for ten core impact categories, sorted in descending order. The error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals derived from Monte Carlo simulations (n = 1000 runs), and the y-axis is on a logarithmic scale.

The analysis reveals that the characterisation results span a wide numerical range across the evaluated categories, spanning nearly eleven orders of magnitude due to the distinct reference units employed. In terms of absolute magnitude within the CML baseline method, MAE exhibits the highest numerical value (approximately 2.40 × 103 kg 1,4-DB eq), followed by GWP100 (2.23 kg CO2 eq), FWAE (1.88 kg 1,4-DB eq), and HT (1.78 kg 1,4-DB eq). Conversely, categories such as OLD show the smallest calculated values (3.57 × 10−8 kg CFC-11 eq). It is important to note that these variations in magnitude reflect the specific characterisation factors of each category rather than their relative environmental severity. However, the distinct scale of these results highlights the need for precise, category-specific management strategies.

As indicated by the error bars (representing 95% confidence intervals) in Figure 2, the results of this assessment are highly robust. For most high-impact categories, including MAE and GWP100, the uncertainty ranges are very narrow relative to their mean values, suggesting stable and reliable assessment results. This enhances the credibility of the key environmental impact categories identified in this study. Therefore, subsequent improvement measures and mitigation strategies should prioritise the processes and substances that contribute to high-impact categories such as MAE, GWP100, and FWAE.

3.3. Overall Environmental Impact Analysis

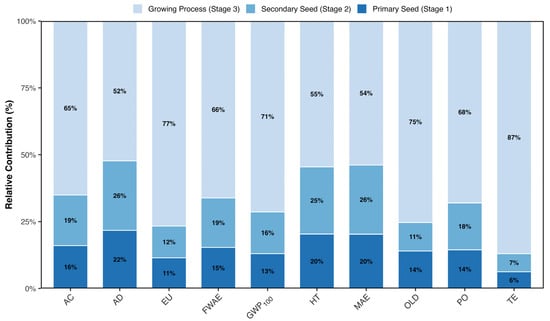

Table 5 presents the total environmental impact results for D. rubrovolvata production, along with detailed contributions from its three primary production phases: the preparation of the primary seed culture, the preparation of the secondary seed culture, and the growing process.

Table 5.

Environmental impact results for 1 kg of fresh D. rubrovolvata mushroom production, including contributions from three Phases.

Table 4 presents the total environmental impacts for 1 kg of fresh product, along with contributions from the three main phases: preparation of the primary seed culture (Phase 1), preparation of the secondary seed culture (Phase 2), and the growing process (Phase 3).

Overall, the growing process (Phase 3) dominates most impact categories. This is evident in its contributions to GWP100 (1.59 kg CO2 eq, ~71%), MAE (1.29 × 103 kg 1,4-DB eq), and EU (5.06 × 10−3 kg PO43− eq). Conversely, Phase 1 contributes less to the total burden, with its contribution to HT being 3.62E-01 kg 1,4-DB eq.

As shown in Figure 3, the growing phase is the undisputed environmental hotspot, contributing over 70% to key impacts like GWP and FWAE. Interestingly, its contribution to AD is relatively lower (~52%), suggesting that upstream inputs for seed culture play a more significant role in this specific impact pathway.

Figure 3.

Relative contributions of the three phases (Primary, Secondary, and Growing) to each environmental impact category for the production of 1 kg of fresh D. rubrovolvata.

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

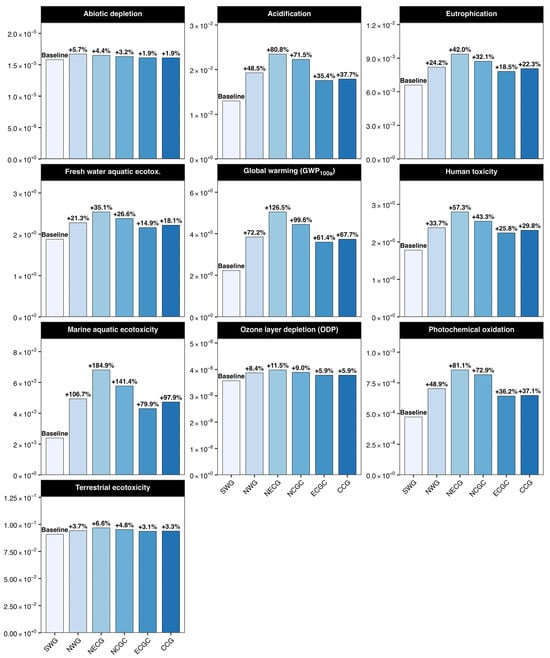

To assess the impact of regional energy heterogeneity on the environmental profile, a scenario analysis was conducted across six distinct regional grid mixes in China: Southwest (SWG), Northwest (NWG), Northeast (NECG), North China (NCGC), East China (ECGC), and Central China (CCG). The detailed results for all impact categories are presented in Table 6 and visually summarised in Figure 4.

Table 6.

Comparison of key environmental impact categories under six regional grid scenarios.

Figure 4.

LCA results for six different power structure scenarios across ten key environmental impact categories. The chart displays the mean values for ten core impact categories. The error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals derived from Monte Carlo simulations (n = 1000 runs), and the y-axis for each category is on a linear scale.

3.4.1. Scenario Comparison

The results reveal substantial variations in environmental performance driven solely by the regional grid composition. The SWG consistently exhibited the lowest environmental burden across all key impact categories, validating its status as the optimal baseline. In stark contrast, the NECG demonstrated the highest impact intensities.

Specifically, for GWP100, the total carbon footprint ranged from a low of 2.23 kg CO2 eq (SWG) to a high of 5.05 kg CO2 eq (NECG). This implies that producing the same quantity of mushrooms in Northeast China would result in a 126% increase in carbon emissions compared to the Southwest region. The NCGC followed closely as the second most carbon-intensive scenario (4.45 kg CO2 eq).

The disparity was even more pronounced for MAE, the study’s dominant impact category. The impact under the NECG scenario (6.81 × 103 kg 1,4-DB eq) was nearly 2.8 times higher than that of the SWG scenario (2.39 × 103 kg 1,4-DB eq). Similarly, for AC, the SWG scenario 1.3 × 10−2 kg SO2 eq) offered a 45% reduction compared to the NECG scenario (2.35 × 10−2 kg SO2 eq).

3.4.2. Statistical Significance

A one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed to verify the statistical robustness of these observations. The results, summarised in Table 7, confirm that the choice of electricity source creates statistically significant differences across all evaluated impact categories (p < 0.001). The F-statistics for key categories such as GWP100 and MAE were exceptionally high, indicating that the “signal” (difference between grid scenarios) is far bigger than the “noise” (internal uncertainty of the model). This confirms that the observed environmental benefits of the SWG scenario are not artefacts of data variability but represent genuine systematic advantages.

Table 7.

Summary of One-Way ANOVA Results for Environmental Impact Categories.

3.4.3. Post Hoc Grouping

To identify specific performance hierarchies, Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc tests were conducted (Table 8). The analysis revealed a clear “tiered” structure among the regional grids:

Table 8.

Tukey’s HSD post hoc comparisons.

Tier 1 (Best Performance): The SWG scenario formed a distinct statistical group with the lowest means for GWP, MAE, and AC, significantly outperforming all other regions.

Tier 2 (Intermediate Performance): The ECGC, CCG, and NWG scenarios generally clustered in the middle range. While statistically distinct from the best and worst scenarios, the differences between these three were less pronounced.

Tier 3 (Worst Performance): The NECG and NCGC scenarios consistently formed the highest-impact group.

Crucially, for the primary indicator GWP100, the 95% confidence intervals of the best scenario (SWG) and the worst scenario (NECG) did not overlap, providing strong statistical evidence that transitioning production from a coal-heavy grid (like NECG) to a hydro-rich grid (like SWG) is the single most effective strategy for decarbonisation.

4. Discussion

Our findings decisively identify electricity consumption as the primary environmental hotspot for the industrial cultivation of D. rubrovolvata, a conclusion that aligns with broader LCA literature on CEA. However, this study moves significantly beyond simple hotspot identification. By integrating uncertainty analysis with formal statistical testing, we provide a quantitative measure of confidence. Our results demonstrate not only that electricity is a major factor, but that the choice of its source is the single most powerful lever for reducing environmental impact. The statistically significant (p < 0.001) performance disparity observed across different regional grid scenarios provides an unambiguous, evidence-based hierarchy for strategic decision-making, effectively eliminating the ambiguity that plagues many conventional LCA studies.

While previous LCA studies in the field of speciality agriculture have provided valuable insights into environmental hotspots [11,12,13,14], they have mainly relied on deterministic approaches. These traditional methods typically use average inventory data, often neglecting the inherent variability in agricultural practices caused by weather conditions, soil heterogeneity, and management differences. As a result, decision-makers are often given single-point estimates that may not fully capture the uncertainty risks.

In contrast to these studies, the framework proposed in this work integrates statistical robustness into the LCA interpretation phase. By explicitly incorporating data variability and performing rigorous statistical analyses (as shown in Section 3), our approach enables a more confident prioritisation of sustainability levers. This supports the growing call in recent literature for more transparent management of uncertainty in LCA [2,6], ensuring that the identified mitigation strategies are not merely artefacts of data averaging but are statistically significant improvements.

4.1. The Primacy of Energy over Agronomy: A Paradigm Shift in Environmental Hotspots

This study reveals that the environmental profile of industrialised D. rubrovolvata production is dominated by ecotoxicological and human health impacts (MAE, FWAE, HT), driven almost entirely by energy consumption. This represents a fundamental paradigm shift away from the typical environmental burdens of open-field agriculture. Unlike traditional farming, where hotspots are linked to agronomic practices, such as fertiliser application (N2O emissions), pesticide use (direct ecotoxicity), and land-use change, our system’s impacts are almost exclusively industrial.

The leading impact, MAE, is a powerful illustration of this shift. It is not caused by farm-level chemical runoff, but is instead an embodied impact from upstream industrial processes. The heavy reliance on coal in the regional energy mix, both for direct electricity use and for the production of inputs like glucose and wheat bran, results in heavy metal emissions (e.g., mercury, arsenic) that are transported and deposited into marine environments. This creates a unique trade-off: the system nearly eliminates direct land use and agricultural pollution, but concentrates its entire environmental load onto the energy sector. Consequently, mitigation strategies must pivot away from traditional farm management and focus squarely on industrial energy systems.

4.2. Strategic Implications and Actionable Pathways for Stakeholders

The clear identification of energy as the decisive hotspot translates complex environmental data into a clear, actionable hierarchy of priorities for key stakeholders. This framework serves as a strategic tool to guide investment and policy.

For Producers and Investors: The message is unequivocal: prioritise capital expenditure on securing clean energy. Our analysis provides a robust business case, demonstrating that investing in clean electricity (e.g., through power purchase agreements or on-site solar PV) yields a vastly superior return on investment for decarbonisation compared to other operational tweaks. This evidence-based directive helps managers avoid maladaptation and costly investments in suboptimal strategies and channels resources toward the most impactful actions.

For Policymakers and Government Agencies: This study provides compelling scientific evidence to directly link energy policy with agricultural development goals. For a government committed to both developing its speciality agriculture sector and achieving carbon neutrality, our findings reveal a powerful synergy: investments in decarbonising the regional electricity grid are the most effective lever for fostering a genuinely sustainable high-tech agricultural industry. This justifies targeted policies such as:

- ♦ Subsidising the adoption of renewable energy technologies at the farm level.

- ♦ Prioritising grid connections to clean energy sources for agricultural enterprises.

- ♦ Integrating agricultural sustainability metrics into regional energy transition planning. In essence, our research demonstrates that for modern CEA, energy policy is agricultural policy.

For Industry Associations: The methodology offers a blueprint for creating robust, sector-wide sustainability standards and eco-labels. By moving beyond generic guidelines to a statistically validated assessment framework, associations can empower members with credible tools to benchmark performance, guide best practices, and enhance the industry’s collective brand reputation in a competitive market. This can also foster collaborative investment in larger-scale renewable energy projects that are unfeasible for a single entity.

4.3. Methodological Contribution: Advancing LCA to a Decision-Support Science

Beyond its specific findings, this study demonstrates a methodological advancement for the agri-food sector. By integrating LCA with Monte Carlo simulation and rigorous statistical testing (ANOVA), we elevate the framework from a descriptive accounting tool to a prescriptive, statistically defensible decision-support science. This approach directly addresses the critical challenge of uncertainty, allowing us to offer conclusions with a specified level of confidence. It provides a transferable template for enterprises to move beyond simple hotspot estimations towards data-driven strategic planning, translating sustainability goals into concrete, verifiable, and impactful actions.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study provides a statistically robust LCA of D. rubrovolvata production, we acknowledge two primary limitations concerning the system boundary. These define the scope of our analysis and highlight clear pathways for future research.

First, our ‘cradle-to-gate’ boundary excludes the end-of-life phase of Spent Mushroom Substrate (SMS). This is based on the observed local practice where SMS is repurposed as a soil conditioner, effectively entering a separate agricultural life cycle. We recognise this ‘cut-off’ approach has significant implications. The reuse of SMS involves a complex environmental trade-off: while it can generate environmental credits by displacing synthetic fertilisers, its decomposition in fields inevitably produces direct greenhouse gas emissions (notably CH4 and N2O) and potentially contributes to nutrient runoff. Consequently, the EU and GWP impacts reported in this study should be interpreted as conservative estimates of the full life cycle performance. However, it is critical to note that this exclusion does not compromise the robustness of our primary conclusion regarding electricity. Given the sheer magnitude of energy consumption in this industrialised facility (contributing >88% to GWP), the net emission variations from SMS soil dynamics, while relevant for eutrophication categories, are statistically unlikely to challenge the dominance of electricity as the primary carbon driver. The ‘signal’ from the energy-intensive climate control system is sufficiently strong to remain the decisive factor for decarbonisation, regardless of downstream soil emission scenarios.

Secondly, the environmental impacts of raw material transportation were excluded, a decision necessitated by the unavailability of reliable primary data. This exclusion is justified by the overwhelming dominance of electricity consumption, which our analysis identifies as the primary environmental hot-spot. To place this in context, a sensitivity analysis based on standard emission factors suggests that even a hypothetical transport distance of 100–200 km for high-volume, locally sourced substrates like sawdust would contribute negligibly, likely less than 3% of the total GWP, a value dwarfed by the contribution from electricity. However, we acknowledge this assumption is more robust for locally sourced bulk materials than for lower-volume inputs like wheat bran, which may be transported over greater distances and warrant specific investigation in future studies. To enhance the model’s completeness, subsequent research should incorporate a detailed transportation log, documenting the origin, distance, and mode for all key inputs.

5. Conclusions

This study delivers a robust, statistically grounded decision-support framework that bridges the gap between high-level sustainability goals and concrete, actionable management decisions in the agri-food sector. By integrating Monte Carlo simulations with formal hypothesis testing (ANOVA), we move beyond the limitations of deterministic LCA to provide decision-makers, from farm managers to policymakers, with the statistical confidence needed to distinguish between marginal improvements and truly transformative actions. The power of this approach was demonstrated through our analysis of a commercial D. rubrovolvata facility, which definitively identified electricity consumption as the paramount environmental hotspot. Our statistical tests confirmed that the choice of electricity source is not just a major factor, but the single most powerful lever for decarbonisation. Specifically, the analysis reveals that production in regions with low-carbon grid mixes (such as the hydro-rich Southwest grid) achieves a statistically significant reduction in carbon footprint compared to coal-dependent regions, highlighting the critical role of regional grid selection. For producers, the message is unequivocal: strategic energy sourcing must be the cornerstone of any credible sustainability plan. For policymakers, this study provides tangible evidence that investments in decarbonising the public grid yield direct and substantial co-benefits in the agricultural sector, creating a powerful synergy between energy and food system policies.

While this study provides a detailed analysis of a specific high-value crop, the methodological framework itself is highly adaptable. Future research could apply it to a broader range of controlled-environment agriculture systems to build a more comprehensive understanding of industrial-scale food production. Ultimately, by providing a clear, statistically validated hierarchy of improvement levers, this work offers not just an operational solution for one facility but a replicable strategic blueprint for evidence-based sustainability management, applicable across the wider landscape of modern, intensive agriculture as it navigates the path toward a carbon-neutral future.

Author Contributions

K.L. (Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing—original draft). A.H.S. and N.N.R.N.A.R. (Supervision, review and editing). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial or personal interests.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Pedigree matrix criteria and uncertainty factors (UFs) for data quality assessment.

Table A1.

Pedigree matrix criteria and uncertainty factors (UFs) for data quality assessment.

| Dimension. | Score | Detailed Criterion | UF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reliability | 1 | Verified data based on measurements | 1.00 |

| 2 | Verified data partly based on assumptions OR non-verified data based on measurements | 1.05 | |

| 3 | Non-verified data partly based on qualified estimates | 1.10 | |

| 4 | Qualified estimate (e.g., by industrial expert); data derived from theoretical information (stoichiometry, enthalpy, etc.) | 1.20 | |

| 5 | Non-qualified estimate | 1.50 | |

| Completeness | 1 | Representative data from all sites relevant for the market considered over an adequate period to even out normal fluctuations | 1.00 |

| 2 | Representative data from >50% of the sites relevant for the market considered over an adequate period to even out normal fluctuations | 1.02 | |

| 3 | Representative data from only some sites (<<50%) relevant for the market considered OR > 50% of sites but from shorter periods | 1.05 | |

| 4 | Representative data from only one site relevant for the market considered OR some sites but from shorter periods | 1.10 | |

| 5 | Representativeness unknown or data from a small number of sites AND from shorter periods | 1.20 | |

| Temporal | 1 | Less than 3 years of difference to our reference year | 1.00 |

| 2 | Less than 6 years of difference to our reference year | 1.03 | |

| 3 | Less than 10 years of difference to our reference year | 1.10 | |

| 4 | Less than 15 years of difference to our reference year | 1.20 | |

| 5 | Age of data unknown or more than 15 years of difference to our reference year | 1.50 | |

| Geographical | 1 | Data from area under study | 1.00 |

| 2 | Average data from larger area in which the area under study is included | 1.001 | |

| 3 | Data from smaller area than area under study, or from similar area | 1.02 | |

| 4 | Data from area with slightly similar production conditions | 1.05 | |

| 5 | Data from unknown OR distinctly different area (north America instead of Middle East, OECD-Europe instead of Russia) | 1.10 | |

| Technological | 1 | Data from enterprises, processes and materials under study (i.e., identical technology) | 1.00 |

| 2 | Data from processes and materials under study (i.e., identical technology) but from different enterprises | 1.05 | |

| 3 | Data on related processes or materials but same technology, OR data from processes and materials under study but from different technology | 1.20 | |

| 4 | Data on related processes or materials but different technology, OR data on laboratory scale processes and same technology | 1.50 | |

| 5 | Data on related processes or materials but on laboratory scale of different technology | 2.00 |

References

- FAOSTAT. FAOSTAT, Statistics Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. 2024. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Goglio, P.; Ponsioen, T.; Carrasco, J.; Tei, F.; Oosterkamp, E.; Pérez, M.; van der Wolf, J.; Pyck, N. Environmental impact of peat alternatives in growing media for European mushroom production. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 964, 178624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Ding, M.; Wu, T.; Deng, X.; Li, Q. Impact of planting Phallus rubrovolvatus on physicochemical and microbial properties and functional groups of soil. Ann. Microbiol. 2023, 73, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GH/T 1422-2023; Technical Regulations for the Cultivation of hongtuozhusun ACFSMC (All-China Federation of Supply and Marketing Cooperatives). China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Leiva, F.; Saenz-Díez, J.; Martínez, E.; Jiménez, E.; Blanco, J. Environmental impact of mushroom compost production: Impact of mushroom compost production. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 3983–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorr, E.; Koegler, M.; Gabrielle, B.; Aubry, C. Life cycle assessment of a circular, urban mushroom farm. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Ecoinvent. 2022 Ecoinvent V3.9.1 Database; Swiss Centre for Life Cycle Inventories: Dubendorf, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- PRé Sustainability. Life Cycle Consultancy and Software Solutions; Simapro 9.5; PRé Consultants: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, B.; Winans, K.; Kendall, A.; Dlott, J.; Dlott, F. A life cycle assessment of Agaricus bisporus mushroom production in the USA. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongpool, R.R.; Pongpat, P. Analysis of Shiitake Environmental Performance via Life Cycle Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2013, 4, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usubharatana, P.; Phungrassami, H. Life cycle assessment of the straw mushroom production. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2016, 14, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, F.; García, J.; Martínez, E.; Jiménez, E.; Blanco, J. Scenarios for the reduction of environmental impact in Agaricus bisporus production. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Action Plan for Air Pollution Prevention and Control. 2013. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2013-09/12/content_2486773.htm (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Action Plan for Water Pollution Prevention and Control. 2015. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-04/16/content_9613.htm (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Opinions on Completely, Accurately and Comprehensively Implementing the New Development Concept and Doing a Good Job in Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-10/24/content_5644614.htm (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Guinee, J.B.; Gorree, M.; Heijungs, R.; Huppes, G.; Kleijn, R.; van Oers, L.; Wegener Sleeswijk, A.; Udo de Haes, H.A.; de Bruijn, J.A.; van Duin, R.; et al. Life Cycle Assessment: An Operational Guide to the ISO Standards; Kluwer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Leiva, F.J.; Saenz-Díez, J.C.; Martínez, E.; Jiménez, E.; Blanco, J. Environmental impact of Agaricus bisporus cultivation process. Eur. J. Agron. 2015, 71, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidema, B.P.; Wesnæs, M.S. Data quality management for life cycle inventories—An example of using data quality indicators. J. Clean. Prod. 1996, 4, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidema, B.P. Multi-user test of the data quality matrix for product life cycle inventory data. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 1998, 3, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 4.5.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.