Abstract

Firm value reflects a company’s market competitiveness, while ESG controversies indicate its ESG risks. This study aims to examine the impact of ESG controversies on firm value and its underlying mechanisms. Using a panel dataset of 851 non-financial firms listed in China’s A-share market between 2010 and 2022, this study investigates the relationship between ESG controversies and firm value using a two-way fixed-effects model. The analysis shows that ESG controversies impair firm value. This relationship remains robust after conducting the Heckman test, 2SLS methods, and heteroskedasticity tests. Further mediation analysis indicates that ESG controversies negatively affect firm value through lower levels of green innovation, total factor productivity, and financing constraints. In addition, the study examines the moderating effects of social performance, environmental performance, and analyst forecast bias. Finally, a heterogeneity analysis was conducted. These findings provide new perspectives for understanding the complex dynamics between ESG controversies and firm value, essential for strengthening the ESG rating framework and promoting sustainable corporate development.

1. Introduction

Compared to traditional financial indicators, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors garner increasing attention in academic and professional spheres [1]. ESG represents a set of non-financial indicators that assess companies’ performance across environmental, social, and governance dimensions. It extends the concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) within the capital market, guiding market participants towards responsible investment practices. By integrating economic, social, and environmental considerations, ESG fosters sustainable economic and social development while ensuring long-term resource viability. From a microeconomic perspective, adopting ESG aligns with quality development principles, positioning it as a critical pathway for promoting sustainable national and corporate growth.

At the corporate level, ESG scores assess whether companies adhere to sustainable, ethical, and responsible business practices. In recent years, the frequent occurrence of ESG-related controversies—such as environmental destruction, labor rights violations, and governance failures—has not only posed a serious threat to corporate reputations but also raised widespread skepticism regarding the effectiveness of ESG metrics in measuring the ethicality and sustainability of corporate behavior. In the third quarter of 2024, the China Select Cloud Platform identified 1178 publicly listed companies exposed to ESG risks, with a total of 4491 risk incidents recorded, indicating that these companies still face significant challenges in ESG management [2]. Such controversies may lead to legal consequences, trigger the involvement of stakeholders, and complicate corporate operations [3].

The ESG controversies score is a recently developed metric within the ESG rating system that comprehensively assesses a company’s sustainability impact and behavior over time. Given the heightened ESG-related risks in China, studying the effects of ESG controversies on firm value is particularly significant, as it enhances academic awareness, encourages firms to shift from reactive remediation to proactive ESG management, and improves the ESG evaluation framework to mitigate greenwashing.

Although ESG controversies are of significant concern, research on their relationship with firm value remains limited. Existing studies primarily focus on ESG scores or their economic consequences [4,5], overlooking ESG controversies as a distinct economic indicator. Previous research often examines ESG controversies from a single dimension, such as tax disputes or control rights conflicts [6,7], lacking a comprehensive analysis. Moreover, most studies emphasize the impact of ESG controversies on analyst forecast accuracy [8] and banking risks [9], with limited exploration of their influence on firm value and the underlying mechanisms. Regarding moderating effects, existing studies predominantly highlight corporate governance within ESG [10], with limited attention to the other two dimensions. Furthermore, existing heterogeneity analyses mainly focus on firm size, performance, and analyst coverage [11,12], neglecting factors such as pollution levels and investor ownership. Against this backdrop, this study addresses the following questions: Do ESG controversies affect firm value? What mechanisms underlie this relationship? What factors may mitigate this effect? Does the impact vary across firms with different characteristics?

Therefore, this study aims to examine the impact of ESG controversies on firm value. Through our research, we seek to fill the existing gap in the literature. This study’s significance lies in its exploration of the mechanisms through which ESG controversies affect firm value and the moderating factors influencing this relationship, providing valuable insights for enhancing corporate ESG management practices.

The contributions of this study are as follows: (1) Expanding Existing Literature: Prior research on ESG controversies has been limited, and focusing solely on ESG ratings may not fully drive improvements in ESG management practices. This study fills the gap in the literature by examining the relationship between ESG controversies and firm value, thereby enriching the theoretical framework linking ESG and firm value. (2) Revealing Multiple Mediating Mechanisms: This study analyzes three mechanisms, contributing to the literature on factors influencing firm value and providing insights for firms committed to ESG principles and sustainable development. (3) Exploring the Moderating Role of ESG Controversies: While international scholars typically analyze the relationship between ESG controversies and firm value from a macro perspective, discussions on the moderating effects are limited. This study explores the moderating role of factors such as social performance, environmental performance, and analyst forecast bias in the impact of ESG controversies on firm value. (4) Innovative Heterogeneity Analysis: Unlike previous studies, this research analyzes the heterogeneity of the impact of ESG controversies on firm value from the perspectives of ownership type, pollution intensity, corporate reputation, and institutional investor shareholding. This conclusion provides valuable insights for promoting ESG practices and enhancing firm value in different contexts.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Framework

We draw on several key theoretical perspectives to understand how ESG controversies affect firm value through various mechanisms.

Signaling theory posits that firms convey information to the market through actions and disclosures [13]. The primary objective of signaling for firms is to reduce information asymmetry and communicate their business activities, product quality, and commitment to sustainability to the market and consumers [14]. In the context of ESG controversies, firms may send negative signals to investors and other stakeholders due to deficiencies in their ESG practices [15]. If a company fails to address ESG controversies effectively, it may be perceived as lacking sustainability and transparency, damaging its reputation [16]. This, in turn, can lower market expectations regarding its future potential, ultimately leading to a decline in firm value.

Resource-based theory emphasizes that a firm’s resources and capabilities are the key factors in achieving competitive advantage [17]. In responding to ESG controversies, firms may need to reallocate resources, particularly in balancing short-term crisis management with long-term strategic investments [18]. To address immediate ESG concerns, a company might divert resources from long-term investments, such as green innovation, toward emergency measures, weakening its future competitiveness [19]. Overemphasis on external ESG pressures, particularly from investors or regulators, can lead companies to delay technological innovation and investments, ultimately affecting productivity growth [20]. Thus, resource-based theory highlights how ESG controversies can influence firms’ long-term development and innovation capacity by altering resource allocation.

Agency theory focuses on the conflict of interests between shareholders and management [21]. Since the interests of shareholders and management may not always align, information asymmetry can lead managers to prioritize their interests at the expense of the firm’s long-term goals [22]. In the context of ESG controversies, management may take short-term actions, such as postponing responses or reducing ESG investments, to meet shareholders’ expectations for immediate returns. This can harm the company’s image and ultimately affect its long-term value [23]. However, a strong governance structure and incentive mechanisms can effectively reduce agency costs, encouraging management to focus more on long-term sustainable development and social responsibility [24].

Stakeholder theory asserts that a firm’s success depends not only on shareholder interests but also on the expectations of other stakeholders [25]. ESG controversies often involve multiple stakeholders, including government, consumers, employees, and communities, whose needs and expectations directly influence corporate decision-making [26]. If a company fails to manage these stakeholder expectations effectively, it may face reputational risks that could negatively impact firm value [27]. When responding to ESG controversies, companies that actively engage with stakeholders’ concerns and adopt appropriate ESG measures can build trust and cooperation with stakeholders, enhance their reputation, and improve market performance [28].

2.2. Hypotheses Development

2.2.1. ESG Controversies and Firm Value

Resource-based theory posits that a firm’s competitive advantage stems from its unique, scarce, and inimitable resources. ESG controversies erode these assets, depleting tangible and intangible resources [29], weakening operational efficiency, and increasing corporate risk exposure [30], ultimately reducing firm value. Firms with fewer ESG controversies demonstrate more excellent resource stability and lower bankruptcy risk [9], particularly in industries where strong ESG practices are crucial. Additionally, ESG controversies can lower employee morale, reduce productivity, and hinder talent retention, constraining innovation and human capital development [11].

Addressing ESG controversies requires significant resource allocation [31], including compliance costs, legal fees, and stakeholder communication. While these measures may temporarily ease regulatory pressure, they can lead to inefficient resource use and divert investment from core business activities and innovation [32]. Excessive focus on dispute resolution also increases managerial stress and reduces strategic flexibility, undermining firm value. These challenges highlight the need for proactive ESG strategies to protect critical resources and sustain competitive advantage. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

ESG controversies are negatively correlated with firm value.

2.2.2. The Mediating Role of Green Innovation

Green innovation, which refers to technological and product innovations aimed at environmental sustainability, is a crucial means to enhance a firm’s long-term competitiveness and market value [33]. When facing ESG controversies, companies must make strategic adjustments to address external pressures. According to resource-based theory, firms may prioritize compliance and reputation management due to resource allocation constraints or short-term financial pressures, potentially neglecting investments in green innovation [34].

According to signaling theory, firms convey information to the market through actions and disclosures, demonstrating their sustainability capabilities [35]. If a company fails to implement practical green innovation or upgrade its green technologies when facing ESG controversies, the market may perceive it as lacking a long-term strategic vision [36]. Particularly for companies with high ESG controversies, low levels of green innovation may be interpreted as insufficient attention to environmental issues, sending a negative signal that further damages the firm’s reputation and investor confidence. This negative signal undermines market valuation and long-term firm value, with media coverage intensifying public scrutiny and amplifying its impact [37]. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2.

ESG controversies diminish the green innovation level, negatively affecting firm value.

2.2.3. The Mediating Role of Total Factor Productivity

Total factor productivity (TFP) is a key indicator for measuring a firm’s technological progress and production efficiency [38]. During economic downturns, the decline in capital utilization is often a driving factor for the decrease in TFP growth [39]. Firms facing ESG controversies may encounter more significant external pressures, including regulatory scrutiny and public criticism. This could lead them to divert resources from long-term innovation and efficiency improvements toward short-term responses to ESG issues, thereby impacting TFP growth [40]. An excessive focus on ESG controversies may also shift investments away from core business activities, suppressing innovation and economies of scale, thus lowering TFP [41].

From the Resource-Based View perspective, a firm’s sustainable competitive advantage depends on its unique resources and capabilities, including efficient operational management and technological innovation. Lower TFP typically indicates inefficiency in resource allocation and technological progress, which, over time, can affect a firm’s core competitiveness. If addressing ESG controversies hinders a firm’s ability to grow TFP, it will face higher production costs, lower profit margins, and reduced market competitiveness, further undermining its long-term development potential [42]. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3.

ESG controversies reduce the level of total factor productivity, thereby negatively impacting firm value.

2.2.4. The Mediating Role of Financing Constraints

Although financing constraints pose challenges, they can encourage the prudent use of capital, prevent inefficient expansion, and enhance resource utilization efficiency [43]. Firms with high ESG controversies face reputational risks and stricter market scrutiny [44]. Due to factors such as the market’s perception of their long-term recovery potential, government support, the promotion of green finance, and the companies’ sizes, some investors may view these companies as potential investment opportunities and provide funding when these companies commit to improving their ESG performance, thereby reducing their financing constraints [45,46].

Agency theory highlights the conflicts arising from information asymmetry and divergent interests between principals and agents. Under low financing constraints, firms may become overly reliant on external capital, neglecting the efficient management of internal resources. When managers prioritize short-term cost avoidance over long-term ESG strategies, they may overinvest in low-return projects while overlooking high-growth opportunities, ultimately reducing capital returns [47]. Conversely, financing constraints force firms to pursue growth through endogenous means, such as self-accumulation and reinvestment of profits. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4.

Financing constraints play a mediating role in the impact of ESG controversies on firm value.

2.2.5. The Moderating Role of Environmental Performance

Environmental performance encompasses firms’ strategies and measures for environmental protection and sustainable development. This study measures it using the Environmental (E) pillar score of the ESG rating. Strong environmental performance signals firms’ commitment to sustainability, fostering stakeholder trust and cooperation [48]. According to stakeholder theory, firms demonstrate their dedication to sustainability through green innovation and emission reduction, reinforcing their responsibility to society and the environment [49]. Empirical evidence suggests that a well-established environmental governance framework can mitigate environmental risks, promote sustainable development, and positively impact financial performance [50].

Strong environmental performance enables firms to mitigate risks associated with fines, lawsuits, and regulatory penalties, thereby preventing financial losses resulting from non-compliance [51]. Adhering to environmental protection measures alleviates regulatory pressure and minimizes potential financial liabilities arising from environmental issues. Additionally, firms with strong environmental performance practices are more likely to attract environmentally conscious investors, as the consistent publication of environmental performance reports enhances transparency, reduces investor uncertainty [52], and stabilizes both market performance and firm value. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5.

Environmental performance mitigates the negative impact of ESG controversies on firm value.

2.2.6. The Moderating Role of Social Performance

Social performance encompasses companies’ social responsibility, labor rights, transparency, and stakeholder engagement [53]. This study measures social performance using the S-pillar score from the ESG rating. According to stakeholder theory, a firm’s long-term value is shaped by shareholders and a broad range of stakeholders, including employees, consumers, governments, and society. While disclosing corporate social responsibility (CSR) information may not lead to immediate short-term profit gains, it can significantly enhance a company’s long-term value [54]. A firm’s performance in social performance—such as employee welfare, labor protection, community support, and supply chain management—helps maintain strong stakeholder relationships during times of controversy, thereby mitigating the negative impact of ESG disputes on firm value [55].

Effective social performance fosters stakeholder engagement, reduces information asymmetry, and builds trust through transparent communication [56]. It also enables firms to manage risks related to labor conditions, consumer protection, and corporate social responsibility [57]. Firms can minimize financial losses and maintain market valuation despite ESG controversies by collaborating with stakeholders to address these concerns. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6.

Social performance mitigates the negative impact of ESG controversies on firm value.

2.2.7. The Moderating Role of Analyst Forecast Bias

Analyst forecast bias is the average deviation between analysts’ and actual earnings predictions. According to signaling theory, information asymmetry in the market makes it difficult for investors to accurately assess a company’s actual value. At the same time, analysts’ forecasts can help the market gain a more comprehensive understanding of a company’s long-term potential and strategy [58]. Excessive optimism can hinder investment in long-term initiatives like R&D, essential for sustainable growth and firm value [59]. Companies engaged in corporate social responsibility (CSR) often exhibit more prominent forecast dispersion [60], providing investors with valuable signals regarding the companies’ ESG commitments and associated risks.

Analyst forecast bias can be a buffer, preventing investors from overreacting to ESG controversies, promoting rational decision-making and mitigating negative stock price impacts [61]. In this context, investors can access more information, and their emotions and decisions become more diversified. This alleviates market panic, stabilizes valuations during periods of controversy, and enables investors to flexibly adjust their expectations of the company’s value. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7.

Analyst forecast bias mitigates the negative impact of ESG controversies on firm value.

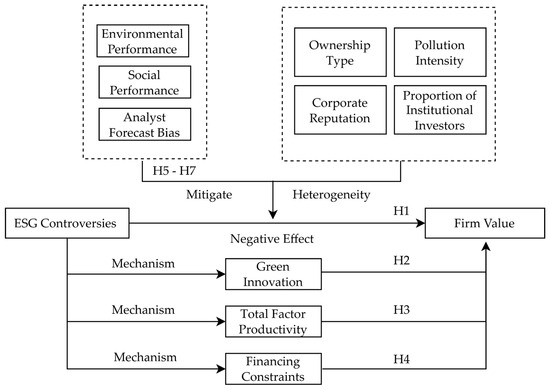

In summary, as shown in Figure 1, ESG controversies influence firm value, which is affected through multiple channels. Additionally, this study examines the moderating roles of social performance, environmental performance, and analyst forecast bias, incorporating firm heterogeneity to enhance the analysis.

Figure 1.

Research framework. Source: developed by the authors.

3. Data and Method

3.1. Sample and Data

This study examines the impact of ESG controversies on firm value using a sample of A-share listed companies in China from 2010 to 2022. To ensure the validity and robustness of the econometric analysis and mitigate the influence of irrelevant or extreme factors, the data were processed as follows: (1) Exclusion of financial firms due to their distinct financial structures and accounting standards; (2) Exclusion of ST, ST*, and PT companies, as they are often associated with financial distress and subject to bankruptcy accounting rather than standard accounting practices; (3) Removal of extreme outliers and missing values to enhance the reliability and stability of the dataset.

ESG controversies scores (ESGc) were obtained from LSEG Workspace (formerly Refinitiv), while other variables were sourced from CSMAR. Firms lacking ESG controversies data or other fundamental variables during the study period were excluded. The final dataset comprises 851 firms and 3273 firm-year observations. Stata 17.0 was used for data analysis, model estimation, and robustness checks.

3.2. Variable Definition

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

This study adopts the firm value measurement method proposed by Gull et al. (2022) [62] and selects firm value (FV) as the dependent variable. Tobin’s Q, calculated as the ratio of market value (A) to total assets, is used as the indicator to evaluate firm value. Tobin’s Q ratio effectively accounts for inter-industry differences, enabling more comparable cross-industry analyses. It reflects a firm’s current market performance and reveals its future growth potential and capital allocation efficiency, making it a more comprehensive metric than other indicators.

3.2.2. Independent Variable

The ESG controversy score evaluates the frequency of adverse events related to ESG issues that a company encounters within a specific year. LSEG Workspace provides data on ESG controversies, with the score based on 23 ESG controversy topics, where current controversies represent the most recent complete period [63]. The ESG controversy score is expressed as a percentile, reflecting the extent to which a company is involved in controversies during a fiscal year. It incorporates adverse media coverage, including lawsuits, fines, and other legal disputes. Additionally, recognizing that larger firms tend to attract more media attention than smaller ones, the score is adjusted for market capitalization to account for potential biases.

3.2.3. Mediating Variables

Digital transformation and green development are key drivers of technological and industrial change. Thus, we examine green innovation (Total) and total factor productivity (TFP) as mediators in the relationship between ESG controversies and firm value. Additionally, financing constraints (SA), which shape firms’ responses to controversies and impact market competitiveness, serve as another key mediating variable.

Innovation research primarily evaluates input and output [64]. Given green innovation’s uncertainty and long R&D cycles, relying solely on input indicators may overestimate actual innovation. R&D investment reflects financial allocation but not outcomes. Following Tan and Zhu (2022) [65], this study uses green patent applications as a proxy, applying a logarithmic transformation to control inter-firm differences.

Total Factor Productivity (TFP) is constructed using the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), following the approach proposed by Lu and Lian (2012) [66]. The GMM method addresses potential endogeneity issues within the model by incorporating instrumental variables, commonly selected as the lagged values of the dependent variable.

Financing constraints (SA) affect firms’ responses to controversies and shape market competitiveness. Based on firm size and age [67], the SA index remains unaffected by short-term financial fluctuations, reducing endogeneity concerns. The calculation formula for the SA index is as follows:

Here, Size refers to the natural logarithm of the company’s total asset size, and Age refers to the number of years the company has been in operation.

3.2.4. Moderator Variables

Previous studies have examined the moderating role of corporate governance (G) [68]. However, this study also considers social (S) and environmental (E) performance and analyst forecast bias, which provides additional information for rational investment decisions.

Environmental and social pillar scores from LSEG Workspace assess environmental and social performance, with higher scores indicating stronger governance. The environmental score reflects resource management, emissions, and sustainability, while the social score evaluates labor practices, community relations, and customer satisfaction.

Analyst forecast bias, the deviation in market expectations of firm performance, reduces market sensitivity to ESG controversies. Following Zhang et al. (2021) [69], this study excludes forecasts released after annual reports, retains only the latest forecast per analyst per year, and omits missing EPS data. The calculation formula is as follows:

where represents the analyst forecast earnings per share (EPS) for company i in the current year. is the average of the latest EPS forecasts from all analysts, refers to the actual EPS, and represents the stock price of company i in year t−1.

3.2.5. Control Variables

Based on previous studies [1,70], this study includes control variables that may influence firm value. These variables are firm size (Size), company risk (Risk), leverage (Lev), revenue growth rate (Growth), ownership concentration (Large), and capital expenditure (Cap).

The specific variable descriptions are as follows: Size is measured as the natural logarithm of a firm’s total assets, where a more significant total asset value indicates a larger firm size. Risk is assessed using the BETA value weighted by annual market capitalization, estimated based on the Capital Asset Pricing Model using data from the most recent year. Lev is calculated as the ratio of total debt to total assets. Growth is the difference between the current year’s operating revenue and the previous year’s operating revenue, divided by the previous year’s operating revenue. Large represents the shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder, expressed as a percentage. Cap is calculated as capital expenditure divided by the book value of assets. This study aims to more accurately analyze the impact of ESG controversies on firm value by controlling for these potential confounding factors. The detailed definitions and measurements of these variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of variables.

3.3. Model Construction

To test the impact of ESG controversies on firm value, i.e., Hypothesis 1, this study constructs model (3):

where i represents the firm and t represents the year. is the firm value measured by Tobin’s Q, is the ESG controversies score, and include a series of control variables. This study accounts for industry and time-fixed effects to mitigate endogeneity issues arising from omitted variables. If the coefficient in the model (3) is significantly negative, it indicates that ESG controversies negatively impact firm value.

To test Hypotheses H2–H4, a stepwise regression approach is employed, constructing a mediation effect model using Model (3), Model (4), and Model (5).

Within this framework, the mediating variables include green innovation, total factor productivity, and financing constraints.

To test Hypotheses H5–H7, the following moderation effect model is constructed:

The moderating variables include environmental performance, social performance, and analyst forecast bias, with representing the interaction term between ESG controversies and the moderating variables.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Table 2 presents the sample’s industry distribution, covering 17 industry categories and providing a comprehensive assessment of the overall landscape of Chinese listed companies. Notably, the manufacturing sector accounts for 60.22% of the sample. Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for this study. The table shows that the mean firm value (TobinQ) is 2.2981, with a significant difference between the maximum and minimum values, indicating substantial variation among the sample firms. The average of the ESG controversies score is 89.0792. The values of other control variables also fall within a reasonable range.

Table 2.

Frequency of observations per industry.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

3.5. Correlation Analysis

This study utilizes the Pearson correlation matrix as an initial diagnostic tool to evaluate the potential presence of multicollinearity among variables. Typically, correlation coefficients exceeding 0.8 are regarded as high, which may adversely affect the reliability of regression results. Table 4 presents the Pearson correlation matrix, demonstrating that none of the coefficients surpass 0.8, thus indicating the absence of multicollinearity.

Table 4.

Correlation analysis results.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Regression

Table 5 indicates a negative correlation between ESG controversies and firm value (Tobin’s Q). OLS and fixed-effects regression demonstrate statistical significance at the 5% level. This suggests that, in the short term, companies facing ESG controversies incur substantial costs that directly impact short-term financial performance, reducing firm value. Controversies may erode tangible and intangible resources, such as goodwill and social capital, negatively impacting asset efficiency. These findings support Hypothesis 1, posing that ESG controversies harm firm value. Furthermore, control variables such as firm size and growth potential exhibit the expected significant relationships with firm value.

Table 5.

Baseline regression results.

4.2. Endogeneity Test

4.2.1. 2SLS Test

In the 2SLS model, following Mao and Wang (2023) [71], we use ESG fund holdings (ESG_Fund) as an instrumental variable. ESG_Fund is significantly correlated with ESG controversies, satisfying the relevance requirement. The establishment and scale of ESG funds are primarily determined by fund companies based on market demand and investment strategies rather than the intrinsic value of listed companies, ensuring strong exogeneity.

Table 6 reports the 2SLS regression results. Column (1) presents the first-stage regression, where ESG_Fund is significantly negative at the 1% level. Statistical tests confirm the instrument’s validity. The first-stage F-value is 40.12, exceeding the conventional threshold of 10, ruling out weak instrument concerns. The Cragg–Donald Wald F-statistic (40.12) surpasses the 10% critical value of 19.93, rejecting the null hypothesis of zero endogenous variable coefficients. The Anderson LM statistic also rejects the null hypothesis of weak instrument identification at the 1% level. Column (2) presents the second-stage regression, showing that ESG controversies remain significantly negative. This confirms that after addressing endogeneity, ESG controversies harm firm value. These results further support Hypothesis 1.

Table 6.

The results of the 2SLS test, Heckman test, and heteroscedasticity test.

4.2.2. Heckman Test

This study employs the Heckman two-stage procedure to address the endogeneity issue caused by sample selection bias. First, the explanatory variable (ESGC) is converted into a binary variable (ESGc_D) based on the industry-year median. Next, the number of firms in each industry for each year is calculated, and the average ESG_D of other firms within the same industry and year is introduced as an exogenous variable (OtherESGc). In the second stage, the binary and exogenous variables are included in the regression model to calculate the inverse Mills ratio (IMR). Finally, the IMR is incorporated into Model (3) for adjustment in the regression analysis.

Table 6 presents the regression results. The Heckman two-stage results are consistent with those obtained using OLS and 2SLS regressions, confirming that sample selection bias is unlikely to affect the main findings.

4.2.3. Heteroscedasticity Test

The heteroscedasticity test can indicate potential endogeneity issues. First, we estimate the regression model and calculate the residuals. Then, we square the residuals and perform the Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test to interpret the results. This test examines whether the independent variables affect the squared residuals. A p-value smaller than 0.05 suggests the presence of potential endogeneity, necessitating the use of robust standard errors for correction. We employ the feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) method to correct for heteroskedasticity, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the estimation results. The regression results in Table 6 confirm the validity of this study’s hypotheses.

4.3. Robustness Test

4.3.1. Using Alternative Dependent Variables

To test the robustness of the baseline regression, we employ the market-to-book ratio (MB) and return on assets (ROA) as alternative dependent variables. The market-to-book ratio (MB) is calculated as the market value of equity divided by the book value of equity. At the same time, return on assets (ROA) is computed as net income divided by total assets. Table 7 presents the regression results using these alternative dependent variables. Columns (1), (2), and (3) report the results with MB as the dependent variable, while columns (4), (5), and (6) display the results using ROA. In both cases, the regression coefficients of ESG controversies remain negative, indicating that the negative impact of ESG controversies on firm value persists even when alternative dependent variables are used. This further supports Hypothesis 1.

Table 7.

Robustness: alternative dependent variables.

4.3.2. Using Alternative Independent Variables

This study uses the ESG controversies score (ESGc) from the Wind database as a proxy independent variable. According to the official, authoritative interpretation, ESGc has a total score of 3, and a point deduction system is used based on the three significant sources of news sentiment, regulatory penalties, and lawsuits. The results of the robustness test with the addition of this explanatory variable are shown in Table 8. The regression coefficient of Wind ESGc is −0.7297, which is significant at the 1% level, indicating that ESG controversies significantly negatively impact firm value. This result is consistent with the results of previous studies. Therefore, the regression results of this study are robust.

Table 8.

Robustness: alternative independent variables.

4.4. Mediation Effect Analysis

4.4.1. Green Innovation

Table 9 presents the regression results, showing the mediating effect of green innovation (Total) between ESG controversies and firm value. Column (2) indicates that ESG controversies negatively impact green innovation at the 1% significance level, suggesting that firms show lower levels of green innovation in response to ESG controversies. Column (3) shows a positive effect of green innovation on firm value, highlighting its significant contribution to performance.

Table 9.

Mediation analysis: green innovation.

These findings imply that firms often prioritize short-term measures, such as public relations or temporary adjustments, over long-term green innovation investments when addressing ESG controversies. This underinvestment may limit technological progress, resource efficiency, and market competitiveness, ultimately reducing firm value. These results support Hypothesis 2.

4.4.2. Total Factor Productivity

Table 10 presents the regression results, illustrating the mediating effect of total factor productivity (TFP) in the relationship between ESG controversies and firm value. Column (2) shows that ESG controversies significantly negatively impact TFP, indicating that firms exhibit lower levels of TFP when responding to ESG controversies. In column (3), the coefficient of TFP is significantly positive, suggesting that higher TFP contributes to increased firm value.

Table 10.

Mediation analysis: total factor productivity.

These results indicate that when firms focus primarily on addressing external ESG pressures, they may delay investments in new technologies, processes, and green innovation. This delay can slow down technological advancement, which in turn affects the improvement of TFP. These findings provide empirical support for Hypothesis 3.

4.4.3. Financing Constraints

Table 11 reports the regression results, confirming the mediating role of financing constraints between ESG controversies and firm value. Column (2) shows a significant negative correlation between ESG controversies (ESGc) and financing constraints (SA) at the 1% level. In column (3), the positive coefficient of financing constraints indicates that higher constraints are linked to more excellent firm value. Since financing constraints (SA) are measured by firm size and firm age, and firm size is also included as a control variable, this may introduce some degree of bias. To ensure robustness, we employed an alternative measure of financing constraints, the FC index, for regression analysis, and the results remained consistent with those obtained using SA.

Table 11.

Mediation analysis: financing constraints.

These results suggest that when firms respond to ESG controversies, lower financing constraints may lead to an over-reliance on external capital, neglecting the effective management of internal funds and directing resources toward short-term measures to address ESG issues. This bias towards short-term solutions may limit the firm’s market expansion and sustainable growth, ultimately affecting its long-term value creation capacity. These findings support Hypothesis 4.

4.5. Moderating Effects Analysis

4.5.1. Environmental Performance

Table 12, Column (1), highlights the moderating effect of environmental performance. While ESG controversies negatively impact firm value, environmental performance mitigates this effect. The interaction shows that strong environmental performance helps offset the costs and burdens of addressing ESG controversies through resource optimization, technological innovation, and stakeholder collaboration. Firms with robust environmental performance are more likely to attract environmentally conscious investors and enhance transparency through regular environmental reports, thereby reducing investor concerns and stabilizing market performance and firm value.

Table 12.

Moderating effects of social performance, environmental performance, and analyst forecast bias.

4.5.2. Social Performance

Column (2) of Table 12 presents the moderating effect of social performance. The results indicate that ESG controversies negatively impact firm value, with a 1% significance level consistent with previous studies. However, the interaction term suggests that strong social performance mitigates the adverse impact of ESG controversies on firm value. According to stakeholder theory, a robust social performance mechanism fosters stakeholder trust, stabilizes supply chain relationships, and enhances operational efficiency by reducing agency costs, alleviating the adverse effects of ESG controversies.

4.5.3. Analyst Forecast Bias

Column (3) of Table 12 presents the moderating effect of analyst forecast bias. The results indicate that ESG controversies significantly negatively impact firm value at the 1% level. However, the interaction term suggests that analyst forecast bias mitigates the adverse effects of ESG controversies. Specifically, analyst forecast bias achieves this by alleviating cost pressures and short-term negative impacts, reducing market sensitivity to isolated low ratings, enhancing strategic flexibility, improving stakeholder communication, and encouraging a multidimensional evaluation of firm value.

4.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.6.1. Ownership Type

This study classifies the sample firms into two categories based on state ownership: state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and non-state-owned enterprises (non-SOEs). The results of Table 13 indicate that ESG controversies hurt firm value for both SOEs and non-SOEs. However, the impact on non-SOEs is more affected overall. Non-state-owned enterprises face limited resources and support when addressing ESG controversies, making their brand reputation and governance mechanisms more susceptible to such issues. As a result, non-SOEs tend to experience a more significant negative impact on firm value when responding to ESG controversies.

Table 13.

Heterogeneity analysis: ownership type and pollution intensity.

4.6.2. Pollution Intensity

This study classifies heavily polluting industries based on the secondary industry classification outlined in the 2012 revised “Guidelines for the Industry Classification of Listed Companies” by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). Heavily polluting industries are defined into 15 categories. Based on this classification, the sample firms are divided into heavily and non-heavily polluting firms. The results of Table 13 indicate that ESG controversies hurt firm value for heavily and non-heavily polluting firms. However, the impact is more significant for heavily polluting firms. Due to high investment costs, stringent regulatory requirements, and reduced competitiveness, heavily polluting firms face more substantial adverse effects on firm value when addressing ESG controversies.

4.6.3. Corporate Reputation

Based on domestic and international corporate reputation rankings and the study by Guan and Zhang (2019) [72], this paper considers stakeholders’ evaluations of corporate reputation and selects 12 corporate reputation indicators. Factor analysis is used to calculate each company’s corporate reputation score. The firms are then divided into 10 groups based on their reputation scores, ranked from low to high, with values assigned from 1 to 10. Additionally, firms are categorized into two groups based on the industry annual median. The results of Table 14 indicate that ESG controversies negatively impact firm value for high-reputation and low-reputation companies, with the effect being more pronounced for low-reputation firms. For firms with lower reputations, addressing ESG controversies often require more financial and operational resources [73], which leads to a more pronounced negative impact on firm value.

Table 14.

Heterogeneity analysis: corporate reputation and institutional investor ownership.

4.6.4. Proportion of Institutional Investors

This study uses the proportion of institutional investors’ holdings as an indicator. A dummy variable is constructed based on whether the proportion of institutional investors’ holdings is above the industry’s annual median. The results of Table 14 indicate that ESG controversies negatively impact firm value in companies with high and low institutional ownership. However, this effect is more pronounced and significant in firms with higher levels of institutional ownership. The heightened sensitivity of institutional investors to short-term performance, their higher expectations regarding ESG standards, and the amplifying effect of their market behavior lead to a more significant negative impact on firm value for companies with higher institutional investor ownership when responding to ESG controversies.

5. Discussion

Based on our model design, this study examines the relationship between ESG controversies and firm value. The results indicate a significant negative correlation consistent with previous research [32]. This relationship remains robust after conducting endogeneity tests, including 2SLS, Heckman selection model, heteroscedasticity tests, and additional robustness checks. Specifically, ESG controversies may erode tangible and intangible resources, such as social capital and goodwill, negatively affecting asset efficiency.

Since most studies focus on the United States and Europe [74], expanding the analysis to China, the largest developing country, offers valuable insights. China’s rapid economic transformation and digitalization drive innovation and competitiveness, heightening the risk of ESG controversies. Its unique regulatory environment poses more significant ESG management challenges, making ESG controversies crucial for assessing corporate risk and response.

This study finds that ESG controversies lower firm value through three main channels in the mechanism analysis. Previous studies have mainly emphasized the role of ESG controversies in increasing corporate risk and lowering transparency, thereby raising audit costs [75]. This study, however, extends the analysis by incorporating green innovation, total factor productivity (TFP), and financing constraints as mediating variables, thus deepening the understanding of the mechanisms through which ESG controversies impact firm value. Specifically, when firms face ESG controversies, they may divert resources from long-term investments like green innovation to emergency measures, delaying technological investments, which leads to slower growth in green innovation and TFP. Under low financing constraints, firms may excessively rely on external capital and neglect the effective management of internal resources, thus affecting capital returns.

Moreover, this study analyzes the moderating role of social performance, environmental performance, and analyst forecast bias in this process. Previous research has mainly explored the moderating effects of corporate governance, ESG performance, and government effectiveness [12,31]. In contrast, this study reveals that effective social and environmental performance can enhance stakeholder communication, improve resource allocation, and reduce compliance costs, thus boosting competitiveness. Analyst forecast bias reduces the market’s sensitivity to low-rated firms, mitigating the negative impact of ESG controversies on firm value. These findings elucidate the mechanisms and pathways linking ESG controversies to firm value, further enhancing the understanding of how ESG controversies affect firm value.

The heterogeneity analysis shows that the negative impact of ESG controversies is particularly pronounced in non-state-owned enterprises, high-pollution industries, firms with low reputations, and firms with high institutional ownership. Previous studies have examined heterogeneity based on factors such as firm size, performance, financial knowledge of audit committee members, and media coverage [11,12]. This study, however, highlights the significant role of ownership structure and industry characteristics in responding to ESG controversies. These differences reveal the variation in how different types of firms handle ESG controversies, providing more nuanced empirical support for developing targeted ESG management strategies.

6. Conclusions and Policy Proposals

This study employs a two-way fixed-effects model to examine the impact of ESG controversies on firm value and its underlying mechanisms. It uses a sample of 851 non-financial A-share listed companies in China from 2010 to 2022, totaling 3273 observations. The findings indicate that ESG controversies negatively affect firm value directly and indirectly by influencing green innovation, total factor productivity, and financing constraints. Moreover, strong social performance, environmental performance, and analyst forecast bias can mitigate the impact of ESG controversies on firm value. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that the adverse effects of ESG controversies are more pronounced in non-state-owned enterprises, high-pollution industries, low-reputation firms, and companies with a high proportion of institutional investors.

Based on these above-mentioned findings, the study offers several policy recommendations.

Enterprises should optimize their governance structures, strengthen risk management and compliance mechanisms, and effectively identify, assess, and mitigate ESG risks. To ensure effective oversight and resolution of ESG-related controversies, companies should establish a dedicated sustainability committee at the board level, aligning corporate actions with long-term objectives and stakeholder expectations. Additionally, enterprises should regularly disclose information related to ESG controversies, including the nature of the issues, actions taken, and follow-up measures, to maintain transparency and accountability. Furthermore, integrating green innovation and technological advancements into long-term development strategies can enhance corporate competitiveness and mitigate the adverse effects of ESG controversies.

ESG data providers should adopt global best practices, such as those implemented by LSEG, while also developing adaptive ESG controversies assessment metrics tailored to the specific characteristics of domestic markets. Improving the accuracy and timeliness of ESG data is critical for practical risk assessment. Data providers should standardize cross-industry data collection methods to enhance comparability and reduce inconsistencies in evaluation outcomes. Moreover, they should monitor controversial events in real-time, providing better support for investors and stakeholders in assessing corporate ESG performance. ESG data providers should also promote an objective understanding of ESG controversies, ensuring that specific incidents are neither exaggerated nor underestimated in their impact on firms, thus maintaining fairness and comprehensiveness in ESG evaluations.

Policymakers should establish clear and consistent ESG disclosure standards and regulatory frameworks to eliminate misunderstandings caused by rating inconsistencies or a lack of transparency. Governments should require publicly listed companies to incorporate ESG controversies into their overall ESG disclosures and provide detailed reports on such incidents’ financial, reputational, and long-term value implications. To encourage corporate investment in green innovation and controversy prevention measures, policymakers can offer targeted financial incentives and develop industry-specific guidelines to address sectoral ESG challenges. Furthermore, governments should promote international cooperation and knowledge sharing, equipping enterprises with the necessary technological and informational resources to navigate global ESG challenges while strengthening mechanisms for resolving cross-border ESG disputes. These efforts will contribute to a fair and transparent global ESG governance framework.

This study has several limitations, offering directions for future research. First, the ESG controversies score relies on third-party data providers, with variations in rating standards, data collection, and scoring methods potentially affecting industry consistency. Future research should standardize these criteria and explore industry-specific ESG strategies. Second, the focus on Chinese A-share companies limits the generalizability of findings, highlighting the need for cross-country comparisons. Finally, due to data availability and space constraints, this study did not examine the impact of the individual pillar scores of the ESG controversies on firm value. Future studies could explore the impact of the three central pillars of ESG controversies on the economy, allowing for more detailed analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.; methodology, S.M.; software, S.M.; validation, T.M. and S.M.; formal analysis, S.M.; investigation, S.M.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, T.M.; supervision, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aouadi, A.; Marsat, S. Do ESG Controversies Matter for Firm Value? Evidence from International Data. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Select. ESG Risk Warning Platform for Publicly Listed Companies. Available online: https://csr.infzm.com/esg (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Xue, R.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Linnenluecke, M.K.; Jin, K.; Cai, C.W. The adverse impact of corporate ESG controversies on sustainable investment. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 427, 139237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Kim, H.; Ryu, D. ESG performance and firm value in the Chinese market. Invest. Anal. J. 2024, 53, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Lei, X. A Study on the Mechanism of ESG’s Impact on Corporate Value under the Concept of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, B.P.; McDonnell, S.; Moser, W.J. Do United States Tax Court judge attributes influence the resolution of corporate tax disputes? J. Account. Public Policy 2023, 42, 107156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Chen, X.; Pu, X.; Luo, H. Disputes over Corporate Control at Chinese Firms. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2020, 56, 894–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiemann, F.; Tietmeyer, R. ESG Controversies, ESG Disclosure and Analyst Forecast Accuracy. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 84, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, S.; Mazzu, S. ESG controversies and bank risk taking. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinette, S.; Sonmez, F.D.; Tournus, P.S. ESG Controversies and Firm Value: Moderating Role of Board Gender Diversity and Board Independence. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 4298–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiratta, A.; Singh, S.; Yadav, S.S.; Mahajan, A. When do ESG controversies reduce firm value in India? Glob. Financ. J. 2023, 55, 100809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamer, A.A.; Boulhaga, M. ESG controversies and corporate performance: The moderating effect of governance mechanisms and ESG practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 3312–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Kuehnen, M. Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soschinski, C.K.; Mazzioni, S.; Magro, C.B.D.; Leite, M. Corporate controversies and market-to-book: The moderating role of ESG practices. RBGN-Rev. Bras. Gestão Negócios 2024, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J.; Ruiz, L.; Castillo, A.; Llorens, J. How corporate social responsibility activities influence employer reputation: The role of social media capability. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 129, 113223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm: Fifteen Years After. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesmatzoglou, D.; Nikolaou, I.E.; Evangelinos, K.I.; Allan, S. Extractive multinationals and corporate social responsibility: A commitment towards achieving the goals of sustainable development or only a management strategy? J. Int. Dev. 2014, 26, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, D.; Wright, C. Corporate corruption of the environment: Sustainability as a process of compromise. Br. J. Sociol. 2013, 64, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, D.M.; Davis, R.; Bebbington, A.J.; Ali, S.H.; Kemp, D.; Scurrah, M. Conflict translates environmental and social risk into business costs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7576–7581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F. Agency Problems and the Theory of the Firm. J. Political Econ. 1980, 88, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberti, F.; de Haan, J.; de Groot, G.; Pontrandolfo, P. CSR codes and the principal-agent problem in supply chains: Four case studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, K.; De Masi, S.; Paci, A. Corporate Governance in Banks. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2016, 24, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ain, Q.U.; Yuan, X.; Javaid, H.M.; Usman, M.; Haris, M. Female directors and agency costs: Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2021, 16, 1604–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowie, N.E.; Dunfee, T.W. Confronting morality in markets. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 38, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schormair, M.J.L.; Gerlach, L.M. Corporate Remediation of Human Rights Violations: A Restorative Justice Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 167, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Value: The Role of Customer Awareness. Manag. Sci. 2013, 59, 1045–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.; Wright, M.; Ketchen, D.J. The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chava, S. Environmental Externalities and Cost of Capital. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2223–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiratta, A.; Singh, S.; Yadav, S.S.; Mahajan, A. ESG Controversies and Firm Performance in India: The Moderating Impact of Government Effectiveness. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnese, P.; Cerciello, M.; Oriani, R.; Taddeo, S. ESG controversies and profitability in the European banking sector. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 61, 105042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hao, X.; Chen, F. Green innovation and enterprise reputation value. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 1698–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, M.; Dong, T.; Zhang, Z. Do ESG ratings promote corporate green innovation? A quasi-natural experiment based on SynTao Green Finance’s ESG ratings. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 87, 102623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Willness, C.R.; Madey, S. Why are job seekers attracted by corporate social performance? Experimental and field tests of three signal-based mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.C.; Slotegraaf, R.J.; Chandukala, S.R. Green Claims and Message Frames: How Green New Products Change Brand Attitude. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Monfort, A.; Chen, F.; Xia, N.; Wu, B. Institutional investor ESG activism and corporate green innovation against climate change: Exploring differences between digital and non-digital firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Xie, T.; Wang, Z.; Ma, L. Digital economy: An innovation driver for total factor productivity. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, K. Capital utilization in Japan’s lost decade: A neoclassical interpretation. Jpn. World Econ. 2012, 24, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, D.; Tjosvold, D. Leader values for constructive controversy and team effectiveness in India. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zhang, X.; Yan, C.; Gozgor, G. Climate policy uncertainty and firm-level total factor productivity: Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2022, 113, 106209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanyan, R.; Zhao, T. The contradictory impact of ESG performance on corporate competitiveness: Empirical evidence from China’s Capital Market. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Fu, Y. The Dynamic Characteristics of Technological Innovation Affecting the High -Quality Development of Enterprises under the Constraints of Financing. China Soft Sci. 2019, 12, 108–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, D.W. Financial Regulatory Reforms in Korea Responding to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis: Are They Following the Global Trends? Asia Pac. Law Rev. 2014, 22, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Wu, W. Environment, social, and governance performance and corporate financing constraints. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yao, L. Can enterprise ESG practices ease their financing constraints? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Mendez, C.; Maquieira, C.P.; Arias, J.T. The Impact of ESG Performance on the Value of Family Firms: The Moderating Role of Financial Constraints and Agency Problems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.; Menon, A. Enviropreneurial marketing strategy: The emergence of corporate environmentalism as market strategy. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Hu, C.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, Y. Impact of regional environmental non-governmental organization density on green innovation and firm value. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.Q.A.; Lai, F.-W.; Shad, M.K.; Jan, A.A. Developing a Green Governance Framework for the Performance Enhancement of the Oil and Gas Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, B.W.; Singhal, V.R.; Subramanian, R. An empirical investigation of environmental performance and the market value of the firm. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate Social Responsibility and Shareholder Reaction: The Environmental Awareness of Investors. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Seligman, M.E.P. Beyond Money: Toward an Economy of Well-Being. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest J. Am. Psychol. Soc. 2004, 5, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, C. Corporate governance, social responsibility information disclosure, and enterprise value in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Gu, W. Research on the relationship between Internal Governance Mechanism, Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Value in Food Industry. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities, Guangzhou, China, 30–31 May 2016; pp. 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, C.; Kirkbride, J.; Bryde, D. From stakeholders to institutions: The changing face of social enterprise governance theory. Manag. Decis. 2007, 45, 284–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Steidlmeier, P. Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T. Rationality and Analysts’ Forecast Bias. J. Financ. 2001, 56, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Zhang, X. Analyst optimism bias and corporate R&D investment: An empirical study based on conflicts of interest and transparency of information. Sci. Res. Manag. 2022, 43, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, G.I.J.; Heo, K.; Jeon, S. A comparison of analysts’ and investors’ information efficiency of corporate social responsibility activities. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2024, 15, 547–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Q.; Wei, K.; Dai, P.-F. ESG rating disagreement and idiosyncratic return volatility: Evidence from China. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 70, 102368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, A.A.; Saeed, A.; Suleman, M.T.; Mushtaq, R. Revisiting the association between environmental performance and financial performance: Does the level of environmental orientation matter? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1647–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LSEG. Environmental, Social and Governance Scores from LSEG. Available online: https://www.lseg.com/en/data-analytics/products/datastream-macroeconomic-analysis (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Zhang, Y.; Meng, Z.; Song, Y. Digital transformation and metal enterprise value: Evidence from China. Resour. Policy 2023, 87, 104326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhu, Z. The effect of ESG rating events on corporate green innovation in China: The mediating role of financial constraints and managers’ environmental awareness. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Lian, Y. Estimation of Total Factor Productivity of Industrial Enterprises in China: 1999–2007. China Econ. Q. 2012, 11, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadlock, C.; Pierce, J. New Evidence on Measuring Financial Constraints: Moving Beyond the KZ Index. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 1909–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Lin, S.; Chen, T.; Luo, C.; Xu, H. Does effective corporate governance mitigate the negative effect of ESG controversies on firm value? Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 80, 1772–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.; He, K. Does Financialization Affect the Firm Information Environment? A Perspective of Analyst Forecast. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2021, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirino, N.; Santoro, G.; Miglietta, N.; Quaglia, R. Corporate controversies and company’s financial performance: Exploring the moderating role of ESG practices. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 162, 120341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Wang, Y. Employment Effects of ESG: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Econ. Res. J. 2023, 58, 86–103. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, K.; Zhang, R. Corporate Reputation and Earnings Management: Efficient Contract Theory or Rent-Seeking Theory. Account. Res. 2019, 375, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Haider, Z.A.; Jin, X.; Yuan, W. Corporate controversy, social responsibility and market performance: International evidence. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2019, 60, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M.H.; Tasnia, M.; Mostafiz, M.I. Board gender diversity and environmental, social and governance performance of US banks: Moderating role of environmental, social and corporate governance controversies. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 39, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.; Xia, H.; Liu, Z. ESG rating divergence and audit fees: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 67, 105749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).