Abstract

Urban environments have incorporated sustainable development into their planning by designing more green spaces. Access to urban green space is the key to the progress of urban sustainability, not only environmentally and ecologically but also socially. Research on social sustainability in parks can be achieved through the inclusive design of park settings that encourage diverse social activities. However, previous research rarely considers how park settings can foster social sustainability for young people. Within this context, this paper employs a qualitative research approach to explore young people’s preferences and engagement with parks through art-based and visual methods to understand how they interact with parks in the context of social sustainability. The visual survey, comprising 32 park scene photos, was administered to 192 youth (ages 9–17) in the Moreton Bay Region, Queensland, Australia. These photos captured four park features: play areas and playgrounds; informal and open areas; formal spaces and pathways; and sports spaces. The findings show that young people like park environments with a balance of physical activity, socialisation, and connection to natural areas. Playgrounds were selected for their active play areas, and open spaces were selected for their social and leisure possibilities. Formal pathways, particularly those connected to natural areas, were selected for their quiet and socialising potential, and sports areas, especially those with equipment, were less preferred due to their solitary nature. The findings highlight the importance of designing parks that promote social sustainability through fostering inclusivity and social cohesion. Such insights inform urban planning policies for making public spaces to meet diverse social needs and support social interactions.

1. Introduction

Previous research showed the positive effects of parks on well-being [1,2,3,4,5], as they play a key role in promoting ecological health, social well-being, and economic vitality within cities. Urban parks also foster social cohesion by serving as spaces for recreation, relaxation, and social interaction [6]. They encourage physical activity, improve mental health, and offer venues for cultural and community events. Thus, parks can meet individual needs in an urban or suburban context by providing contact with the aesthetic elements of nature and a place for social interaction where a sense of community identity can grow [7]. The social functions of parks include providing opportunities for gathering and socialising, encouraging people to use such spaces more frequently, and enabling them to feel more satisfied with their neighbourhoods [1,6,8].

Social sustainability in parks refers to the integration of environmental, social, and economic factors in the design, management, and use of green spaces to ensure their long-term viability and benefit to the community. Within this context, the design of park settings can influence behaviour, including increased social activities, gatherings, and informal socialising. This can lead to stronger community ties. For instance, park settings that contribute to the legibility of parks, such as clear pathways, visible entrances, and open sightlines, help people feel more connected to and comfortable within the space [9].

Most existing studies have examined adult park users [10], but research on how youth use urban green spaces is limited. Young people, as a distinct demographic group, exhibit unique interaction patterns within parks that distinguish them from adult users. The way young people use park settings can also be determined by their gender. In this respect, studies show that girls and boys experience outdoor environments differently and engage in activities within these spaces in different ways [11,12]. Although these previous studies emphasise thoughtful design for physical and emotional health benefits and social well-being through urban environments, there is still a lack of clear understanding of designing parks that align with the diverse preferences of young people. Yet, the role of park settings in fostering social sustainability based on young people’s preferences should be considered to create a balance in the ways that park visitors from different age groups engage in parks. Therefore, there is a need to examine young people’s preferences for different park settings to inform the creation of socially sustainable environments that support long-term well-being while strengthening social connections and community cohesion.

Within this context, the main objective of this paper is to understand preferred park settings and activities within those settings from young people’s perspectives to provide recommendations for policymakers and urban planners to design socially sustainable parks for diverse age groups of park visitors. The paper will respond to the research question of “How do young people’s preferences in park settings contribute to socially sustainable park design? To do so, this paper examines how different age groups prefer and use park settings, with a particular focus on young people. In addition, the paper explores park preferences by gender and age to improve park designs that support social sustainability through intergenerational park settings.

2. Background

2.1. Young People’s Preferences for Park Design and Use

Previous studies, e.g., Mani and Woolley (2024) ref. [11], determined that designed outdoor spaces such as parks that provide opportunities for both physical activities and social interaction play a crucial role in promoting young people’s emotional and social development. Studies also show that urban nature parks improve community health [13] and increase citizen well-being through participation [14,15], yet few investigations analyse how different age groups perceive these parks. Additionally, adult park users have been the focus of numerous studies, such as Veitch et al. (2020) [16], yet research on young people’s interactions in outdoor environments such as parks remains insufficient. Recognising different generational viewpoints stands as essential to developing intergenerational inclusion in urban green environments. Research also often fails to account for young people’s preferences and patterns of use that differ from adults.

There are different age ranges of park users who use parks for diverse activities—young people and adults. For instance, young people tend to visit parks with appealing attributes such as well-designed play equipment [17,18,19,20]. In addition, young people more often prefer structured playgrounds, green areas, and developed parks [21]. Adults prefer un-designated park features with vacant areas, corners, rest areas, and playfields and invisible parks such as undeveloped and vacant areas as settings for gatherings and sports and community facilities [22]. Therefore, park environments should be designed according to age appropriateness, with amenities for young people and adults.

Additional studies dispute the notion that outdoor play behaviours are strictly divided by gender. According to Waller’s study in 2010 [23] using gender theory as a framework, it became apparent that young people’s independent outdoor play activities were not restricted by traditional gender norms and did not include distinctions between activities ‘for boys’ or ‘for girls’, which reveals a more flexible gender concept in outdoor environments. Helleman et al. (2023) [12] demonstrated that boys showed different patterns of outdoor play compared to girls, who participated less frequently in such activities. The extent of gender-based differences in outdoor activity participation changed significantly between age groups, which shows that gender affects outdoor activity levels, but this effect can shift with time or varying environmental conditions. The research demonstrates that gender influences outdoor space utilisation through complex patterns, which general trends show, but they also depend on various factors like age and cultural context.

Well-designed parks can be inclusive spaces that meet the needs of diverse populations, supporting social equity and community well-being [24]. It has been argued that uninviting and uninteresting fixed structures (including purpose-built play equipment) can often limit the scope for young people to play imaginatively and creatively. For instance, KFC playground, which consists of three parts, Kit, Fence, and Carpet [18,20], does not offer different activities over an extended period and would be perceived as boring by young users after a short time. Therefore, parks should offer some level of managed risk and a different range of activities; otherwise, young people can perceive these structures as unchallenging and unexciting [17,18,19,20] and will be less likely to use them [17].

2.2. Social Sustainability in Park Design

A literature study of urban natural parks suggests that ecological management helps achieve environmental sustainability and that parks support social sustainability by providing intergenerational spaces and facilitating community participation [17]. Research into how different age groups perceive nature parks has not been fully developed despite the increasing understanding of these parks’ positive effects on community health through user participation and intergenerational design approaches [14,25]. The literature lacks insight into how different age groups perceive park design and usage, which is essential for developing inclusive intergenerational park designs that promote ecological and social sustainability.

Social sustainability in parks can be achieved through the inclusive design of park settings that encourage diverse social activities, such as gathering areas, playgrounds, and pathways that facilitate movement and connection. It also looks at how the park functions as a public space for people of all ages, backgrounds, and social groups, promoting social equity and reducing social isolation. Büyükağaçcı and Nurgül Arısoy (2024) [9] highlight that well-maintained, accessible parks play a crucial role in building a sense of community and belonging, contributing to the overall social sustainability of urban areas. Most park designs focus on where park users spend their time (e.g., [21,26]), rather than directly measuring their social relationships or engagement and how they spend their time. This highlights the gap in understanding how young people are socially engaged within parks and how park design can foster social sustainability.

2.3. Gender Differences in Park Usage

According to the literature review, multiple studies demonstrate how gender determines individual interactions with outdoor spaces such as parks and public areas and show notable differences between boys and girls in their perception of these areas [11,12,27,28,29]. Findings from research indicate that park proximity matters for everyone, but gender determines which park areas people visit and the activities they choose to participate in. The study by Loukaitou-Sideris et al. (2010) [30] showed that girls preferred playground equipment, while boys were more inclined to use sports fields (see article 13). The research by Timperio et al. (2008) [30,31] confirmed that boys participated in sports activities more often than girls. Gender influences how outdoor spaces are used because boys and girls show different activity preferences based on available options. Therefore, there is a need to better understand whether gender differences affect the way young people perceive park settings in the context of social sustainability.

3. Methods

Several related phenomena have propelled the arts into social research practice [32,33,34]. As new theoretical and epistemological perspectives are developed, there is an attendant need for methodological innovation. Qualitative research relates to a broad range of methodological approaches that examine the lives and situations of real people in real times and places [35]. Qualitative research is inductive in that it draws on the richness and complexity of human situations and meanings to generate descriptive generalisations and theories grounded in experience [33].

Within this context, previous research mainly employed conventional methods such as open-ended surveys and interviews along with observational methods to collect data about how people use parks and their preferences [36]. Yet, these studies fail to deliver enough empirical evidence for understanding user behaviour and engagement patterns. For instance, open-ended surveys typically collect personal opinions but fail to document direct interactions with the environment. Research using GIS, GPS, and online mapping systems produced essential findings about patterns of park usage, according to previous research [3,4,36]. Though these traditional methods yield important qualitative data, they fail to account for personal subjectivities and emotional bonds, which participatory or visual methods like photo elicitation and visual ethnography document more effectively. In addition to these methodological constraints, young people’s participation can take many forms and operate at different levels in the qualitative research process, from young people participating as research informants to young people participating as researchers. Key issues surrounding young people’s participation in research and the forms this may take in qualitative research practice are now considered [37,38]. A comprehensive qualitative methodology with a set of data collection techniques plus the interpretive techniques and theories used to create meaning out of the data should be given equal status to or at least status independent of any other methodology employed within a research project with young people.

The turn to the arts has been natural for some qualitative researchers because they view artistic inquiry as an extension of what they already do. As art-based and visual tool methods can be an excellent starting point for participatory processes in research related to social life and well-being among young people [39], it is important to remember that young people are the experts on what their creations mean. This artistic participatory method allows researchers to learn a great deal about participants’ feelings [34]. Therefore, this paper addresses this knowledge gap in previous research by using participatory visual surveys known as photo-elicitation methods. The survey can facilitate deeper participant engagement, especially among young users who can share their experiences and preferences more naturally and vividly. This qualitative approach enabled the author to gain a more comprehensive view of young people’s interactions within spaces and young people’s preferences within both natural areas and built settings of parks, which previous studies lacked due to their reliance on passive data collection techniques.

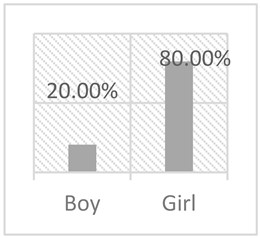

The visual survey was designed for this study using Key-Survey. The 32 photos were selected to be viewed as groups of four photos per screen on an iPad. The park scene photos consisted of features including playgrounds, pathways, natural elements such as trees or water, and sports fields (see Figure 1). The survey was self-administered and took the participants about 10 to 15 min to complete. The photos depicted park scenes without people to limit any influence of the perceived emotional state of people in a photo. The park scenes appeared similar to but did not include actual parks in the region to avoid potential bias due to familiarity or memories of those places.

Figure 1.

Park scene photos presented in groups of four on iPad.

The visual survey procedure included the following: First step—eight sets of photos with four photos each (at 72 px/in.) were presented on an iPad, and participants were asked to select photos based on their preferred elements. Second step—after selecting their preferred park scene, participants were asked questions to understand their choices and the activities they prefer to do at the scenes in the selected photo.

3.1. Study Area

The data collection took place in the Moreton Bay Region in South East Queensland, Australia. The Moreton Bay Region is home to 417,000 people (Moreton Bay Regional Council, 2016) with young people aged 9–17, numbering approximately 30,000 (13.4%) (Moreton Bay Regional Council, 2016 Census). This area has a diversity of natural features such as different wildlife species, beaches, hinterland hikes, and lookouts. In Moreton Bay, the wetlands are extremely varied, from perched freshwater lakes to sandflats and mangroves adjoining the bay’s islands and the mainland. This variety in habitats contributes to the bay’s biological diversity (reported by the Queensland government). The Moreton Bay Region includes diverse landscapes and over 1700 parks (approximately 3900 hectares), many of which are local and neighbourhood parks.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

The visual survey was conducted with ethics approval from QUT’s Human Ethics Research Committee (approval number 2000000474). The survey was first sent to different youth communities within the Moreton Bay Region to collect data, and they were asked to share the link on their Facebook pages (see Figure 2). The online survey potentially excluded young people who have restricted access to internet services or social media platforms as well as young people who participate less frequently in digital communities. Therefore, due to the difficulties in finding a diverse group of young people (aged 9–17) within online communities’ platforms (with a response rate of 2%), the visual survey was also conducted in person. To do so, the author went to eight different parks and two youth community centres within the Moreton Bay Region. A total of 192 participants aged 9–17 participated in this study. Prior to the main data collection, a pilot study was conducted to test the usability of the visual survey and the clarity of the questions related to each photo.

Figure 2.

The uploaded survey link on a youth community’s Facebook Page.

The decision to use in-person methods was to reach diverse demographics but also introduced potential sampling biases. Young people who typically visit parks and community centres may have been overrepresented in the in-person survey method, which could skew the sample towards more active or community-engaged individuals. The strategic survey distribution and site selection actively reduced methodological biases to enhance the reliability and validity of results.

The collected data were analysed through descriptive and inferential statistics using Microsoft Excel (2010). Content analyses were performed to categorise the responses. The thematic analysis process started by categorising the park scenes and preferred activities based on young people’s responses to the selected photos. The preferred activities and the reason for selecting each photo for the most selected scenes from each of the eight screens were categorised as activities and characteristics/features. This enabled additional insights for design recommendations (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Themes based on photos’ characteristics.

The sample consisted of 93 boys (49%) and 96 girls (51%), with three participants not reporting their gender. The median age was 12.17 years (SD = 2.72), with a higher proportion in the range of 10–14 years. A total of 21 youth (11%) did not have any siblings at the time of the survey (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Participant characteristics.

A chi-square test for independence was conducted to examine the relationship between gender, age, and whether participants were only children, to assess their association with categorical variables such as environmental and behavioural characteristics. The results, including χ2 values with (r-1) (c-1) degrees of freedom, indicated that the relationships between gender and age were statistically significant but lacked practical significance, likely due to a Type I error. To further confirm the findings, a bootstrap technique, typically applied to small- to medium-sized samples (<200), was used.

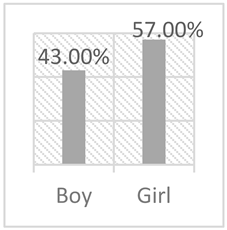

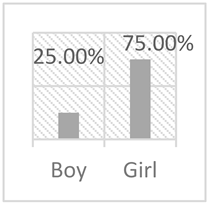

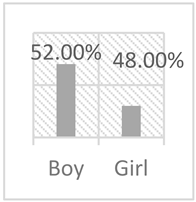

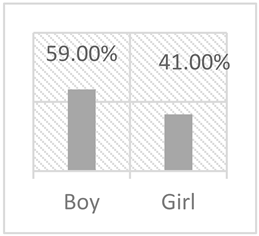

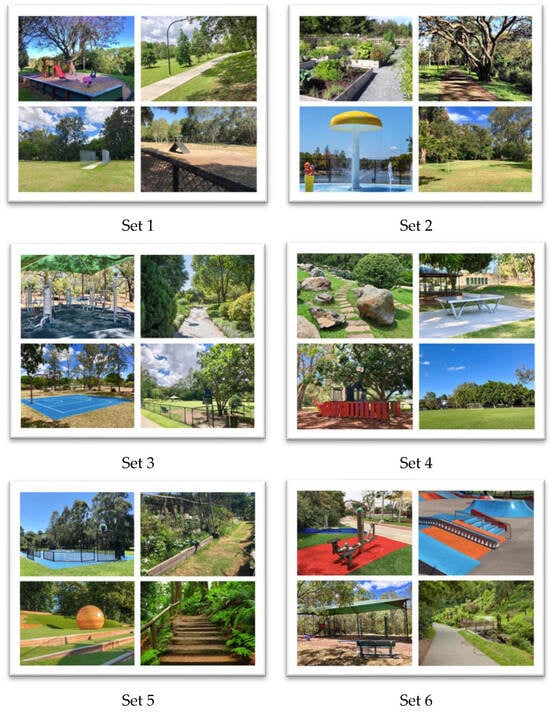

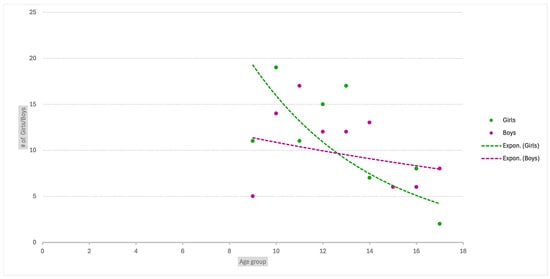

In terms of gender, the findings show that there is no clear difference between boys’ and girls’ preferences for social engagement in parks. The gender findings show that both girls and boys preferred mostly the same park settings, with only about a 10% difference in most selected photos. Figure 3 illustrates the number of girls and boys in relation to their age group.

Figure 3.

The scatterplot shows that there is no strong trend of increase or decrease for either gender.

4. Findings

To better interpret data, photos based on the predominant features in each photo were classified using four categories: play areas and playgrounds (areas designed for activities including those with games equipment and play), natural areas like informal and open spaces (a design with an emphasis on unstructured recreation and access to nature, such as woodlands), formal areas and pathways (organised structured path network), and sports areas (areas used for competitive and organised sports and exercise equipment areas) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Photos’ categorisation based on the predominant features in each photo.

The current categorisation (C1–C4) was designed to structure the data in a way that aligns with the study’s main aim of evaluating young people’s preferences in park settings while examining links to social sustainability. The categorisation was based on the following:

- -

- Play areas and playgrounds (C1): The play areas and playgrounds category targets spaces created for play activities, which are fundamental for young people. Playground areas usually feature equipment and structures that support both imaginative activities and physical exercises. Incorporating this category can help evaluate how young people appreciate recreational spaces meant for social engagement.

- -

- Natural areas like informal and open spaces (C2): The natural areas like informal and open spaces (C2) category contains spaces meant for unstructured recreation and nature access with features like woodlands and open grassy areas. The logic behind this category exists because natural areas create chances for spontaneous play and interaction with nature.

- -

- Formal areas and pathways (C3): These spaces allow young people to move easily while promoting social interaction and providing access to park settings.

- -

- Sports areas (C4): These spaces offer facilities for competitive sports and structured physical activities. This category can help to investigate young people’s preference for areas designed for sports and exercise activities, which support teamwork through structured games. This classification aids in separating spaces meant for individual informal use like natural areas from those which facilitate competitive group physical activities.

4.1. C1—Play Areas and Playgrounds

The top two photos selected by young people include a splash pad/water park (70%) and a skate park with ramps (64%). The young people’s preferences show that more water elements, such as a splash pad, and hardscapes, such as ramps, were the most preferred settings within the parks. The most preferred activities for the splash pad/water park depicted were ‘swim’ and ‘play and/or have fun’ (see Table 4).

Table 4.

The most preferred photos in relation to play areas.

In addition, the data related to photos with playgrounds illustrate that the activity differences can be related to the design of those facilities (see Table 5). There are various physical skills used: ‘swinging’, ‘climbing’, ‘balancing’, ‘jumping’, and ‘running’. This equipment maintains engagement and is perceived by young people as the main reason for staying longer within these facilities.

Table 5.

The most preferred photos in relation to playgrounds.

Therefore, the young people’s preferences indicate that the diversity of activities makes them want to stay longer in these spaces. Playgrounds need diverse equipment that encourages multiple physical activities to boost play experiences and keep young people engaged for longer periods. Implementing this design strategy generates active play spaces that support physical growth and foster social health for users.

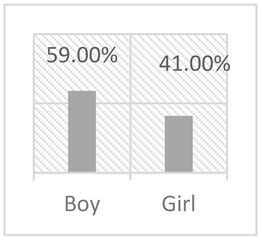

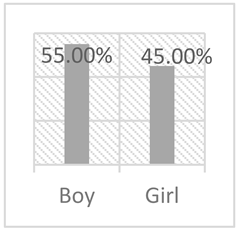

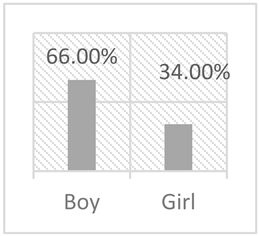

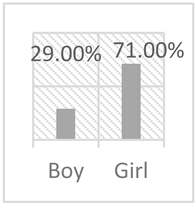

Playgrounds surrounded by grasses and trees (see photo #3 in Table 5) were mostly preferred by boys (66%) in comparison with girls (34%). The fact that boys show a greater preference for green and natural environments, such as grassy areas and trees, may be related to gender differences in outdoor activities and interaction with nature. Boys may be more inclined to exploratory and active play, which such spaces typically encourage, while girls may engage with their surroundings differently and may prefer other types of play settings that emphasise social interaction or creativity. This difference suggests that gender plays a role in young people’s perceptions and that these different preferences should be considered in the design of parks and playgrounds to create spaces that are responsive to all users.

4.2. C2—Informal and Open Spaces

These areas are preferred for three reasons: they are good for a specific type of activity (e.g., football); the area includes certain environmental features (e.g., open space); and the area offers the company of other young people and adults. Ball games are perceived by young people to help them get together and spend time with each other.

Photos that have more grass areas were selected more by young people for more physical activities such as ‘playing ball games’ and ‘running’. Additionally, optional activities such as ‘reading books’ and ‘relaxing’, ‘having picnics’, ‘hanging out’, and ‘spending time with their pet’ were mentioned frequently by them. Being with a group of peers or others was highlighted in photos with grass areas (see Table 6).

Table 6.

The most preferred photos in relation to informal and open spaces.

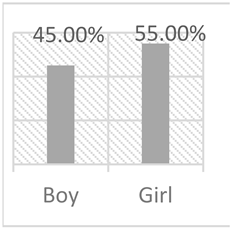

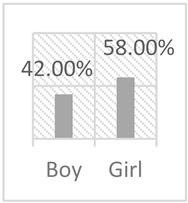

Many boys selected photos of informal and open spaces. Boys often exhibit more active and assertive behaviours, which may explain their preference for informal, open spaces. These spaces provide freedom for activities such as running, playing ball, and other forms of play that allow for more physical movement and independence. From a developmental perspective, boys may be more likely to seek out spaces that offer less structure and more opportunities for exploration, competition, and active play. Open spaces also allow for greater social interactions, often in the form of group activities or games, which are more common among boys.

Some of the descriptions from some young participants are as follows: ‘I would like to run around or play tag with my friends’ by P109, a girl aged 11; ‘Run around and hang out’ by P37, a boy aged 15; ‘Nice place to talk and catch up’ by P80, a boy aged 16; ‘Relax underneath the trees and read a book’ by P06, a girl aged 10; ‘Play a friendly game of footy or relax and have a picnic with a few friends’ by P187, a girl aged 15; and ‘Have a chill day. Run around the park’ by P 136, a girl aged 13. The expanded analysis reveals how various park environments affect emotional and psychological results. Physical activity zones in parks help reduce stress and enhance mood, whereas quiet reflection spaces or social areas build relaxation and strengthen community bonds.

4.3. C3—Formal Areas and Pathways

The activities most preferred by young people, which led them to select related photos, include activities such as ‘walking’, ‘hiking’, and ‘relaxing and enjoying nature’. From the young people’s perspectives, pathways with more natural areas were preferred more for relaxing and talking with others, for instance, ‘At this park, I would take photos and relax with my family and/or friends’ by P19, a girl aged 13; ‘Enjoy time with my parents’ by P73, a boy aged 12; ‘See the tropicalness and walk around on the bridge’ by P108, a girl aged 9; ‘At this park I would relax and enjoy the view with my family and friends’ by P17, a girl aged 13; ‘I would like to take a nice walk and watch the water flow and see the trees’ by P109, a girl aged 10; and ‘It makes you feel relaxed and calms you down’ by P122, a boy aged 11. The less dominant theme was ‘playing’ (defined as recreational activities—non-physical and social activities). A limited number of young people found photos with pathways related to the bushes suitable for playing hide and seek. For instance, one response was ‘Because I can play hide and seek and there would be better hiding spots’ by P77, a boy aged 10. They preferred to be with their friends and family (specifically their parents) when they used pathways connected to the natural areas (see Table 7).

Table 7.

The most preferred photos in relation to formal areas and pathways.

Furthermore, the relatively lower preference for pathways associated with physical activities or recreational activities suggests that many young people choose natural areas not for active play but because they provide peaceful settings for interaction and contemplation along with low-energy socialising opportunities. The choice to visit natural areas with family members, especially parents, demonstrates the emotional connections and social relationships formed in nature-based spaces. Natural pathways function as family-centred spaces that enable bonding and collective experiences.

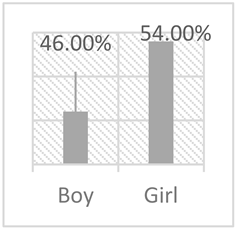

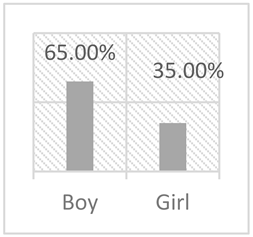

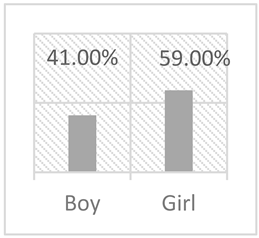

The analysis also shows that a significant proportion of girls prefer photos of formal areas and nature-related paths compared to boys. This translates to a 42% greater preference for these spaces among girls, indicating a gender difference in how outdoor spaces are perceived and used. This preference contrasts with the boys’ preference, suggesting that gender influences spatial choices in some park settings.

More opportunities for physical activities such as ‘running’ and ‘riding bikes or scooters’ were related to those photos with paved pathways. Young participants described their activities, with statements such as the following: ‘I would prefer if you could make the running/jogging/walking path wider so people can race with each other’ by P100, a boy aged 10; ‘Do running and jogs’ by P38, a boy aged 17; ‘I would like to walk and ride my skateboard on the pavement’ by P56, a boy aged 14; and ‘Walk around the area and look at the plants’ by P165, a boy aged 11 (see Table 8).

Table 8.

The most preferred photos in relation to more physical activities.

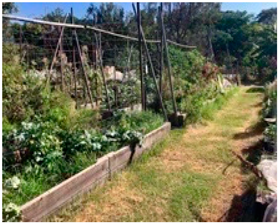

Pathways connected to the gardens were less preferred by young people for spending time there. The young participants found these photos less attractive and functional for their leisure time to be with their friends (see Table 9).

Table 9.

The least preferred photos in relation to pathways.

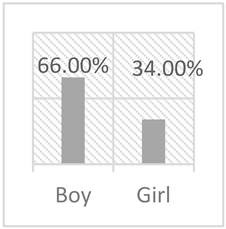

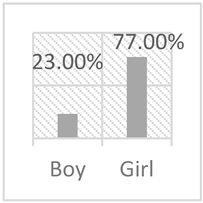

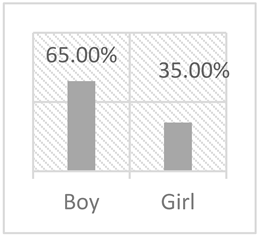

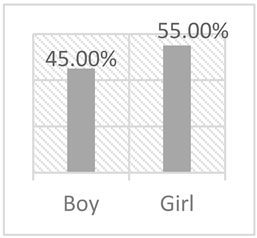

The data analysis also shows that a small proportion (only 3%) of young people selected photos of paths connecting gardens with gravel paths. However, within this small group, 80% were girls, indicating a distinct gender preference for this type of space. For instance, a girl aged 16 (P145) mentioned, ‘I think having a public garden would be great for insects and birds, as well for people to enjoy the herbs and plants growing there’. This suggests that girls may have a stronger preference for more structured, garden-like environments with defined paths, possibly valuing the aesthetics, order, or sense of connection to nature that such spaces offer. In contrast, boys did not show the same level of preference.

The predominant theme of the activities within parks identified by young people was ‘relaxing’. They identified activities such as ‘To take part in growing vegetables and fruits, and learn to source things locally’ by P28, a girl aged 15; ‘I would want to see what is growing on the plants and look at the animals nearby’ by P70, a girl aged 12; and ‘Just look at the plants and flowers and enjoy nature’ by P143, a girl aged 10.

4.4. C4—Sports Areas

When comparing the most preferred photos with those photos that were least interesting to young participants, the photos with exercise equipment were least preferred. One of the reasons for not selecting these photos is that young participants prefer to use park settings that are more challenging to them, where they can practice their skills with their friends. Most of the young participants were more interested in using the park settings with their friends and siblings than being alone or with other people such as grandparents, neighbours, aunts/uncles, or others who are not their close friends or family. The main reason for not selecting photo 3 in Table 10 was that exercising in a shaded area was the priority for young participants.

Table 10.

The most preferred photos in relation to sports areas.

The main factor behind this preference is that young participants look for park settings that offer challenging activities as well as skill development opportunities, especially when they are with their friends. Young people prefer dynamic environments with stimulating activities because such designs meet their developmental needs and interests better than static exercise equipment.

The social environment in which parks were utilised greatly affected user preferences. Young participants showed a clear preference for park activities when they were with their immediate friends and siblings as opposed to more distant family members or strangers. Young people find peer group interactions during park visits highly valuable, which implies that spaces designed for these social experiences would attract more young visitors.

‘Doing exercise’ and ‘using the equipment’ were the predominant sub-themes for describing the photos in Table 10. Young participants commented with the following: ‘Use the gym equipment’—P116, a boy aged 14; ‘Workout and exercise to play friends or a friend’ by P124, a boy aged 11; ‘My siblings and I love the workout parks so we would just figure out how to use it and take turns just using it until we get bored and switch’—P123, a girl aged 13; ‘Use the table tennis with friends, family, usually during the afternoon with a sibling or with a large gathering’—P92, a boy aged13; ‘This would be a great place to work out and become fit and healthy. Due to some gyms costing money, this idea will help kids and adults get fit. People could host events around here and there could even be groups’—P29, a girl aged 13; and ‘We can exercise and have fun and hang out with friends’—P33, a girl aged 13. The second sub-theme that was raised by young people was ‘hang out’, for instance, ‘Hang out with mates and have contests’—P136, a girl aged 13. ‘Relaxing’ was the next sub-theme identified, for instance, ‘Chill out’—P66, a girl aged 12. Exercise equipment provided more interactions among young people or non-social interaction for young people who preferred to be there alone.

5. Discussion

The findings from this research provide insights into how young people are socially engaged in parks. This unpacks the complex relationship between spatial design, social interaction, and overall well-being. Categorising photos based on their predominant features such as play areas and playgrounds, informal and open spaces, formal areas and pathways, and sports areas could give a better understating of how the design of these spaces contributes to fostering social sustainability. These findings, therefore, contribute to discussions about how public spaces such as parks can be designed to meet the needs of diverse social groups, particularly young people.

5.1. Social Sustainability Within Playgrounds: Enhancing Engagement Through Play

The preference for play areas and playgrounds, particularly those equipped with equipment for a variety of physical activities like swinging, climbing, and balancing, is central to fostering social sustainability in urban settings. These spaces support physical development and encourage young people to engage with their peers. The extended engagement in playgrounds can be attributed to their design, which facilitates both individual and group activities. This aligns with research that highlights the role of well-designed playgrounds in enhancing physical and social development among young people [40]. Based on the findings, young people prefer to stay longer in play areas with their peers and family members. This highlights the importance of including spaces that foster not only physical activity but also social interaction. Within the context of social sustainability, there is a need for urban planners to prioritise play areas that offer both challenging physical experiences and opportunities for social engagement.

Through these efforts, playgrounds become essential for social sustainability, while they provide safe spaces for community interaction and inclusivity for children, young people, and their families, along with caregivers. The areas function as essential social gathering points, which support young people in developing their social skills and establishing friendships while connecting with other community members.

5.2. Social Sustainability Within Informal and Open Spaces: Social Gathering and Informal Play

The most preferred photo related to informal and open spaces reveals the critical role that flexible, unstructured environments play in fostering social engagement. Young people highlighted activities such as playing ball games, running, relaxing, and spending time with peers or pets in these areas. This implies that open, green spaces are essential for fostering informal social interactions and community building. Such spaces are inclusive by supporting a variety of activities. In the context of social sustainability, the fact that these spaces can support the types of activity that young people prefer (physical or social) is a key ingredient for community. Moreover, the preference for grassy and open areas for games and gatherings aligns with studies emphasising the importance of nature in promoting mental health and social connectedness [41,42]. Creating accessible, flexible green spaces can therefore enhance the overall quality of life for young people, especially in densely populated urban environments.

Young people find these spaces essential for relaxation and personal reflection while building social connections rather than just recreational areas. Urban planners who want to improve social sustainability need to design green spaces that are easily accessible and adaptable for multiple uses. Planning these spaces requires designs that support both physical exercise and social interaction, since they become essential assets to build community connections while improving mental health and developing local identity.

5.3. Social Sustainability Within Formal Areas and Pathways: Relaxation and Connection to Nature

The findings regarding formal areas and pathways, particularly those connecting to natural environments, reflect the significance of structured yet relaxing spaces in promoting social sustainability. Young people in this research particularly preferred pathways that allowed for walking, hiking, and enjoying nature with family or friends. These areas seem to provide opportunities for relaxation and reconnection. The preference for pathways that offer visual access to natural features like trees, water, and gardens highlights the psychological benefits of nature, such as stress reduction and increased emotional well-being [43,44,45,46]. Social sustainability in this sense means designing places that not only foster social interaction but also provide opportunities for personal reflection and well-being. The fact that garden-linked pathways received fewer preferences does not diminish the importance of gardens themselves. This finding demonstrates that urban planners must find an equilibrium between design aesthetics and practical functionality. People engage longer and enjoy outdoor spaces more when pathways provide activities for exercise or social interaction along with visual appeal.

The design of formal areas and pathways must take into account aesthetic qualities and how these spaces enable social interaction alongside relaxation and physical activity to achieve social sustainability. Urban planners who develop spaces with social and personal advantages can support young people’s emotional and social health while improving their bonds with nature and their community.

5.4. Social Sustainability Within Sports Areas: Promoting Physical Health and Social Interaction

Sports areas and exercise equipment were less preferred by young people compared to more informal or nature-oriented spaces, yet they still represent important components of social sustainability. The relatively low preference for exercise equipment, particularly when compared to playgrounds or open spaces, suggests that while physical activity is valued, young people tend to prefer settings that offer a combination of challenge, social interaction, and enjoyment. This is in line with other studies that show that young people are more likely to go to spaces where they can develop social networks and competencies and have playtime with friends [44,45]. Interestingly, the preference for table tennis and skate parks indicates a desire for spaces that promote active social interaction, rather than isolated exercise. This highlights the importance of designing sports spaces that encourage group participation and fun, rather than just competitive activities.

Urban planners need to build spaces that support group activities and social interaction rather than just areas for competitive sports or solo workouts. By including inter-active sports equipment along with multipurpose courts and open spaces for informal play, these areas become active community centres that enhance physical fitness and social interaction. Promoting social sustainability in sports areas requires environments that merge physical activities with social interaction possibilities. These spaces promote individual fitness alongside social connections through group cohesion and belonging.

5.5. Gendered Preferences and Social Sustainability

The findings of this research suggest that gender-specific preferences for outdoor spaces require urban planners to understand the distinct ways boys and girls use these environments. Girls benefit from outdoor environments that combine natural elements with structured spaces and areas for social interaction that support emotional and social well-being, consistent with social sustainability goals. Boys tend to developmentally prefer spaces that provide challenging activities with opportunities for exploration and freedom for active play. Boys also show a strong preference for natural environments with grass and trees, suggesting that informal spaces should include access to nature. These areas allow for exploratory activities and offer the benefits of green space that promotes relaxation and regeneration. Open spaces serve the dual purpose of physical movement and relaxation, which helps create socially sustainable environments by allowing for a variety of activities, from energetic play to peaceful contemplation. In this context, providing opportunities for group activities and shared games in these spaces is likely to provide opportunities for social interaction that helps build team skills among girls and boys.

Through gender-sensitive design, public spaces can become inclusive areas that accommodate a variety of activities including active play as well as quiet reflection. The findings regarding gendered preferences indicate that park setting designs should be balanced to accommodate every user’s needs. The design of urban spaces needs to move beyond universal solutions because boys and girls are likely to have different patterns of engagement with park settings. Similar to the findings of Cohen et al., 2020 [47], boys favour active spaces that enable physical activity and social interaction, but girls prefer structured areas that connect to nature and allow time for relaxation and emotional bonding. Park settings that blend active play areas with quiet nature spaces create socially sustainable environments that support the emotional and social needs of all young people.

6. Implications for Social Sustainability in Urban Planning

In the broader context of social sustainability, these findings show the importance of designing public spaces in ways that are inclusive, mixed-age, functional, and accessible to a wide range of social groups. Young people’s preferences highlight a desire for spaces that balance physical activity, social interaction, and connection to nature. These spaces are primarily used by young people with their peers and family, highlighting the role of public spaces in fostering social bonds and community cohesion. Further, the study reveals areas for improvement, such as the need for better integration of challenging, skill-building play in sports spaces and considering other social needs when designing pathways and gardens.

For urban planners and policymakers, the findings suggest that designing public spaces with the following principles in mind will contribute to social sustainability:

Multi-functionality: Parks should support a wide range of activities, from physical play to social gatherings and personal relaxation.

Inclusivity and mixed ages: Parks need to be accessible to and inclusive of all ages and social groups so that different demographics can participate.

Connection to nature: Access to green spaces and natural features should be prioritised, as they contribute to both physical and mental well-being.

Social interaction: Parks should foster social cohesion by encouraging interaction among peers, family members, and community members.

Flexibility: Parks should be adaptable to various types of play, relaxation, and exercise, allowing for informal and structured activities.

7. Conclusions

This paper showed how park design is essential for creating socially sustainable urban settings for young people. When urban planners understand what young people prefer in parks, they can create spaces that promote both physical health and social interaction as well as overall well-being. In addition, this paper demonstrated that young people’s preference for park settings is linked to their need for physical and social engagement and connection to nature. Park settings that incorporate elements of play, relaxation, and community engagement are central to fostering social sustainability, providing environments to support well-being and social connection.

This paper highlights the importance of designing parks within cities so that they are socially sustainable through well-being, inclusion, and social connection. These insights contribute to urban planning strategies aimed at designing public spaces such as parks to meet diverse social needs, enhance quality of life, and foster social interactions. As young people from different socioeconomic backgrounds and cultures will prefer different park settings, there is a need to understand and compare how young people from diverse backgrounds prefer parks to provide more equity and inclusivity in designing socially sustainable parks. Therefore, future research should further explore the longer-term effects of different park designs on young people and their well-being and community dynamics, as well as how different cultures, socioeconomics, and environment can impact young people’s engagement.

This paper employed visual tools to increase the reliability of young people’s responses. Future research is required to compare both researchers’ and participants’ perspectives (i.e., asking young people to take photos in addition to the visual tool) to better understand their preference within parks. Additionally, future research could also examine the role of participatory design practices to co-create spaces that accommodate young people’s preferences and needs in diverse urban contexts. Investigating these research areas will help create urban parks that fulfil both the physical recreational requirements of young people and the development of socially sustainable communities.

Funding

This research was funded by the Queensland University of Technology, https://research.qut.edu.au/designlab/projects/preferences-of-youth-for-social-engagement-in-neighbourhood-parks/, accessed in 1 January 2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has been approved by Queensland University of Technology (QUT) with approval code 2000000474.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants in the study gave informed consent. Following ethics requirements, the data used in this paper are anonymous.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on the author’s PhD project at the Queensland University of Technology. The author would like to thanks all participants who participated in this research to make their future parks more socially sustainable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, S.; Christensen, K.M.; Li, S. A comparison of park access with park need for children: A case study in Cache County, Utah. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 187, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunton, G.F.; Almanza, E.; Jerrett, M.; Wolch, J.; Pentz, M.A. Neighborhood park use by children: Use of accelerometry and global positioning systems. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fjørtoft, I.; Jostein, S. The natural environment as a playground for children: Landscape description and analyses of a natural playscape. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2000, 48, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goličnik, B.; Ward Thompson, C. Emerging relationships between design and use of urban park spaces. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2010, 94, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, A.T.; Potwarka, L.R.; Saelens, B.E. Association of park size, distance, and features with physical activity in neighborhood parks. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, M. Just sustainability in urban parks. Local Environ. 2012, 17, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaesaeidi, P.; Cushing, D.F.; Washington, T.; Buys, L. Just to make new friends and play with other children: Understanding youth engagement within neighbourhood parks using a Photo-Choice tool. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 235, 104757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaesaeidi, P.; Cushing, D.F.; Washington, T.; Buys, L. How youth are socially engaged in parks: A participatory-approach for understanding youth perceptions and use patterns. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 588, 052058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyükağaçcı, S.B.; Arısoy, N. Social Sustainability in Urban Parks: Insights from Alaeddin Hill Park, Konya. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutz, A. Student and senior views on sustainable park design and intergenerational connection: A case study of an urban nature park. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 241, 104920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, M.; Woolley, H. Evaluating children’s preferences of the orphanages’ outdoor spaces: Integrated multi-method ‘Jourchin’approach. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 93, 102191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleman, G.; Nio, I.; de Vries, S.I. Playing outdoors: What do children do, where and with whom? J. Child. Educ. Soc. 2023, 4, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Liu, S. Mechanisms underlying the effects of landscape features of urban community parks on health-related feelings of users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutz, A.; Derr, V.; Chawla, L. Fluid or fixed? Processes that facilitate or constrain a sense of inclusion in participatory schoolyard and park design. Landsc. J. 2018, 37, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Azcárraga, C.; Diaz, D.; Zambrano, L. Characteristics of urban parks and their relation to user well-being. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Flowers, E.; Ball, K.; Deforche, B.; Timperio, A. Designing parks for older adults: A qualitative study using walk-along interviews. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 54, 126768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleśniewicz, P.; Pytel, S.; Markiewicz-Patkowska, J.; Szromek, A.R.; Jandová, S. A model of the sustainable management of the natural environment in national parks—A case study of national parks in Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, H. Watch this space! Designing for children’s play in public open spaces. Geogr. Compass 2008, 2, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, J. Signs of Neglect: Play in a Relict Landscape. Master’s Thesis, Lincoln University, Lincoln, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Malone, K. Children’s place encounters: Place-based participatory research to design a child-friendly and sustainable urban development. In Geographies of Global Issues: Change and Threat; Springer: London, UK, 2016; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, L.; Martin, K. What Makes a Good Play Area for Children. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zamani, Z. Young children’s preferences: What stimulates children’s cognitive play in outdoor preschools? J. Early Child. Res. 2017, 15, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.; Lee, J. Children’s neighborhood place as a psychological and behavioral domain. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, T. ‘Let’s throw that big stick in the river’: An exploration of gender in the construction of shared narratives around outdoor spaces. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 18, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, R.H.; Kaplan, R. People needs in the urban landscape: Analysis of landscape and urban planning contributions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, J.W.; Tynon, J.F. Small-scale urban nature parks: Why should we care? Leis. Sci. 2010, 32, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulay, A.; Norsidah, U.; Said, I. Legibility of neighborhood parks as a predicator for enhanced social interaction towards social sustainability. Cities 2017, 61, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, M.R. Geographies of outdoor play in Dhaka: An explorative study on children’s location preference, usage pattern, and accessibility range of play spaces. Child. Geogr. 2022, 20, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, Y.; Keshavarzi, G.; Aman, A.R. Does play-based experience provide for inclusiveness? A case study of multi-dimensional indicators. Child. Indic. Res. 2022, 6, 2197–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A.; Sideris, A. What Brings Children to the Park? Analysis and Measurement of the Variables Affecting Children’s Use of Parks. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timperio, A.; Giles-Corti, B.; Crawford, D.; Andrianopoulos, N.; Ball, K.; Salmon, J.; Hume, C. Features of public open spaces and physical activity among children: Findings from the CLAN study. Prev. Med. 2008, 47, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leedy, P.D.; Ormrod, J.E. Practical Research; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Leavy, P. Arts-based research as a pedagogical tool for teaching media literacy: Reflections from an undergraduate classroom. Learn. Landsc. 2009, 3, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.A.; DeForge, R.T. Qualitative inquiry and the debate between hermeneutics and critical theory. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 1567–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J. Generalising from qualitative research. In Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2003; Volume 2, pp. 347–362. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, M.; Sundevall, E.; Wales, M. The role of green spaces and their management in a child-friendly urban village. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 18, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowycz, K.; Jones, A.P.; Page, A.S.; Wheeler, B.W.; Cooper, A.R. What can global positioning systems tell us about the contribution of different types of urban greenspace to children’s physical activity? Health Place 2012, 18, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derr, V.; Louise, C.; Mintzer, M. Placemaking with Children and Youth: Participatory Practices for Planning Sustainable Communities; New Village Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wesson, M.; Salmon, K. Drawing and showing: Helping children to report emotionally laden events. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. Off. J. Soc. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2001, 15, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, H.; Lowe, A. Exploring the relationship between design approach and play value of outdoor play spaces. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refshauge, A.D.; Ulrika, K.S.; Petersen, L.S. Play and behavior characteristics in relation to the design of four Danish public playgrounds. Child. Youth Environ. 2013, 23, 22–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, S.; Button, B.; Coen, S.E.; Gilliland, J.A. ‘Nature makes people happy, that’s what it sort of means:’children’s definitions and perceptions of nature in rural Northwestern Ontario. Child. Geogr. 2019, 17, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, J.; Nesbitt, L.; Mavoa, S.; Meitner, M.J. Attributes and benefits of urban green space visits–Insights from the City of Vancouver. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 98, 128399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Springer: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Veitch, J.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D.; Abbott, G.R.; Salmon, J. Park improvements and park activity: A natural experiment. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 42, 616–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadavi, S.; Kaplan, R.; Hunter, M.R. How does perception of nearby nature affect multiple aspects of 413 neighbourhood satisfaction and use patterns? Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 360–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Han, B.; Williamson, S.; Nagel, C.; McKenzie, T.L.; Evenson, K.R.; Harnik, P. Playground features and physical activity in US neighborhood parks. Prev. Med. 2020, 131, 105945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).