Circular Perspective for Utilization of Industrial Wastewaters via Phytoremediation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Conditions

2.2. Plant Characterization

2.3. Substrates for Plant Cultivation

2.4. Wastewater for Plant Irrigation

2.5. The Scheme and Conditions of the Experiment

2.6. Analytical Procedures

2.7. Evaluation of Plant Physiological Activity

2.8. Quality Control

2.9. Calculations, Statistical Analysis of the Results, and Graphics

- Biomass dry matter yield (BY, g∙pot−1 D.M.);

- Yield tolerance index (TI, -) defined as the ratio of the yield of plants (i.e., biomass dry yield) grown on substrates watered with industrial wastewaters to the yield of plants from control objects (i.e., grown without watering with wastewaters) [48];

- Concentration of elements in collected biomass (C, mg∙kg−1 D.M.);

- Concentration index (Cin, -) of elements in biomass, calculated as the ratio of metal concentration in plants grown on substrates watered with industrial wastewaters to the concentration of metals in plants from control objects;

- Bioconcentration factor (BCF, -) defined as the ratio of the metal concentration in the plant to the metal concentration in the substrate on which the plant was grown [48];

- Metal uptake (U, mg∙pot−1), calculated as the product of biomass dry matter yield and metal concentration.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physico-Chemical Properties of Materials Used in Experiments

3.2. Giant Miscanthus Yield in the Pot Experiment

3.3. Yield Tolerance Index

3.4. Biomass Heat of Combustion

3.5. Concentrations of Elements in Substrates and Plants

3.6. Metal Uptake by Plants

3.7. Selected Physiological Parameters of Plants

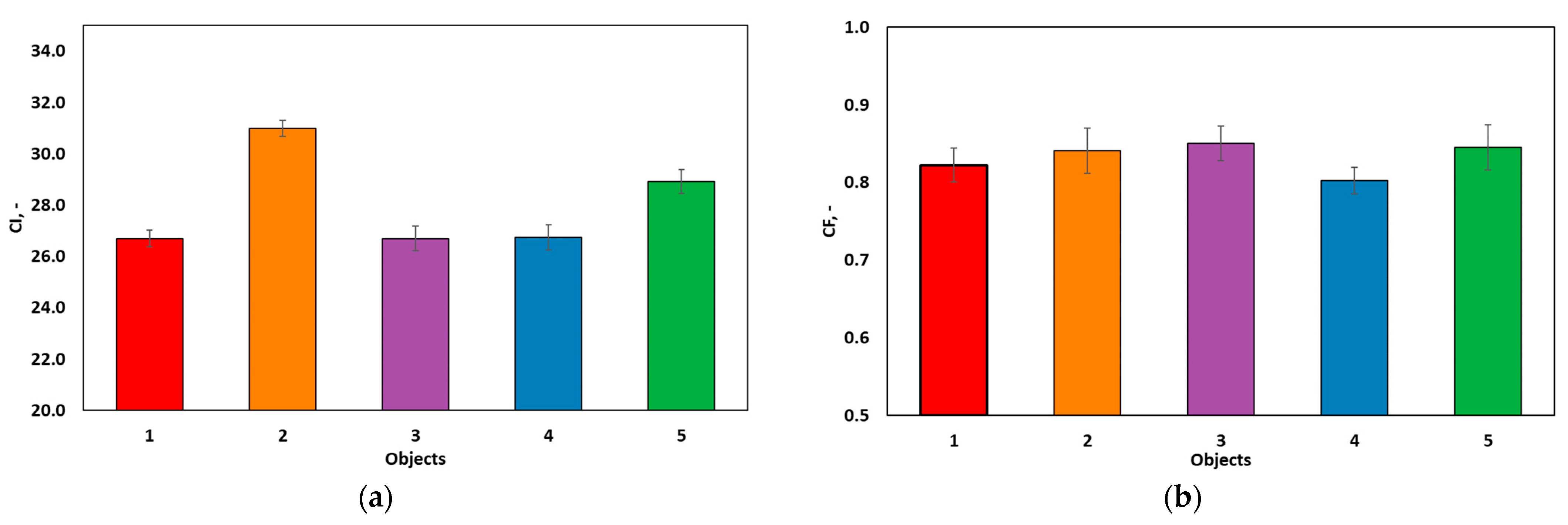

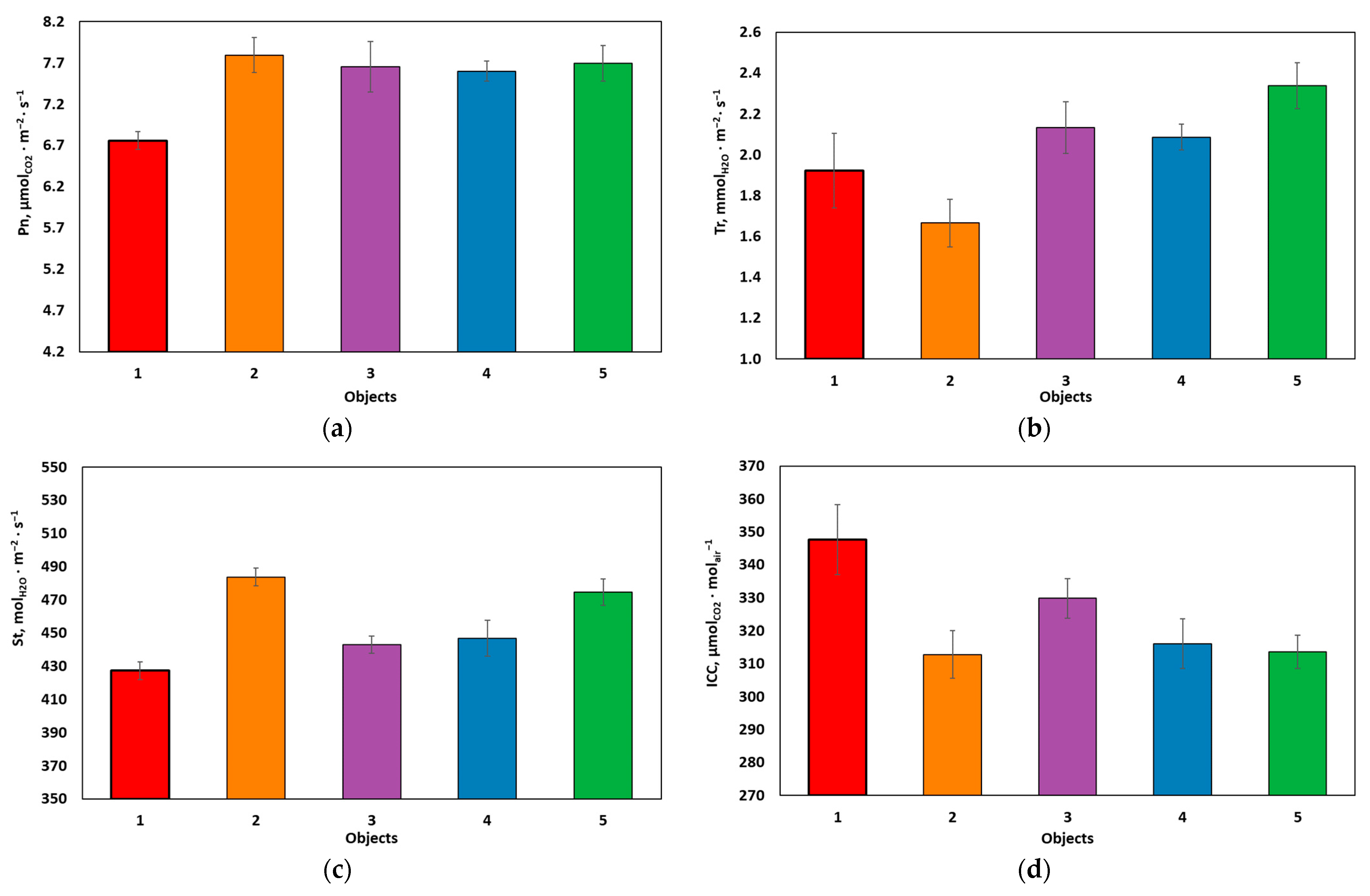

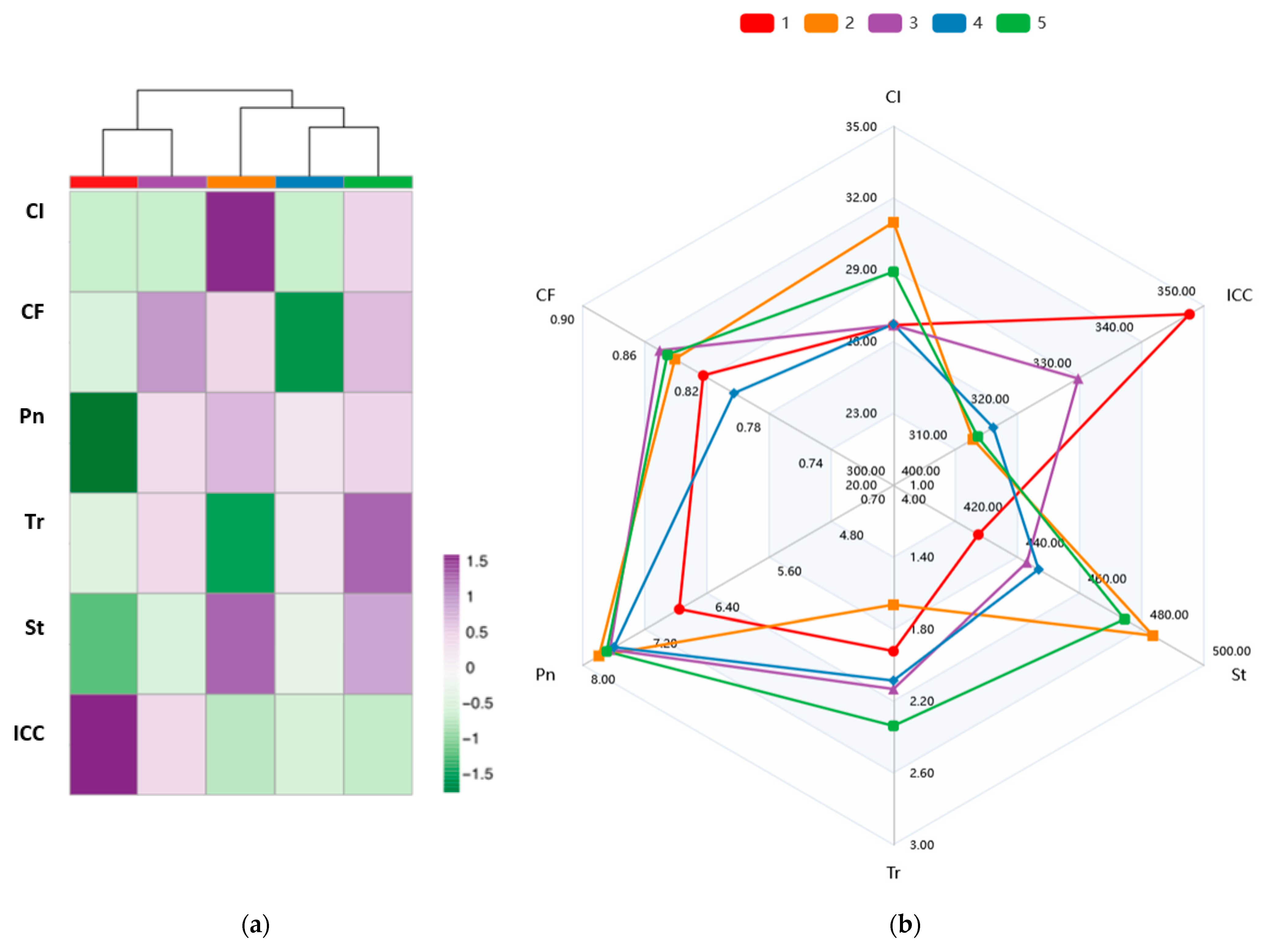

3.8. Principal Component Analysis

3.9. Limitations of the Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BCF | bioconcentration factor |

| BY | biomass yield |

| C | concentration of element in biomass |

| CF | chlorophyll fluorescence |

| CI | chlorophyll index |

| Cin | concentration index |

| D.M. | dry mass |

| HC | heat of combustion |

| ICC | intercellular CO2 concentration |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| Pn | net photosynthesis |

| S | sand |

| SK-9 | soil improver |

| St | stomatal conductance |

| TI | yield tolerance index |

| Tr | transpiration |

| U | metal uptake |

| W | wastewaters |

Appendix A

| Parameter | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 6.7 ± 0.2 | |

| Electrical conductivity | μS∙cm−1 | 38,000 ± 120 |

| Turbidity | NTU | 895 ± 10 |

| Odor | TON | >1000 ± 10 |

| Suspensions | mg∙L−1 | 1790 ± 36 |

| Dissolved substances | mg∙L−1 | 37,630 ± 40 |

| Dry residue | mg∙L−1 | 39,400 ± 80 |

| BOD5 | mg∙L−1 | 17,050 ± 40 |

| CODCr | mg∙L−1 | 34,800 ± 56 |

| Permanganate index | mg∙L−1 | 2360 ± 45 |

| Ammonium nitrogen | mg∙L−1 | 3120 ± 64 |

| Nitrate nitrogen | mg∙L−1 | 1.81 ± 0.10 |

| Total nitrogen | mg∙L−1 | 3355 ± 30 |

| Chlorides | mg∙L−1 | 8340 ± 105 |

| Sulfates | mg∙L−1 | 11,500 ± 235 |

| Fluorides | mg∙L−1 | 1630 ± 20 |

| Phosphates | mg∙L−1 | 329 ± 24 |

| Sulfides | mg∙L−1 | 34.6 ± 4.8 |

| Phenol index | mg∙L−1 | 3.35 ± 0.05 |

| Substance extractable with petroleum ether | mg∙L−1 | 290 ± 8 |

| Copper (Cu) | mg∙L−1 | 0.184 ± 0.02 |

| Zinc (Zn) | mg∙L−1 | 6.11 ±0.05 |

| Lead (Pb) | mg∙L−1 | <0.010 |

| Cadmium (Cd) | mg∙L−1 | <0.005 |

| Chromium (VI) | mg∙L−1 | <0.010 |

| Chromium—Total (Cr) | mg∙L−1 | 1.56 ± 0.05 |

| Nickel (Ni) | mg∙L−1 | 0.87 ± 0.04 |

| Iron–Total (Fe) | mg∙L−1 | 41.2 ± 0.4 |

| Manganese (Mn) | mg∙L−1 | 13.8 ± 1.1 |

| Mercury (Hg) | mg∙L−1 | <0.0005 |

| Potassium (K) | mg∙L−1 | 2960 ± 36 |

| Sodium (Na) | mg∙L−1 | 2654 ± 16 |

| Calcium (Ca) | mg∙L−1 | 1790 ± 24 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | mg∙L−1 | 357 ± 1 |

| General hardness | mmol∙L−1 | 65.4 ± 4.5 |

| PAHs | μg∙L−1 | 0.059 ± 0.005 |

| TOC | mg∙L−1 | 10,750 ± 50 |

| Parameter | Units | Value |

|---|---|---|

| pHH2O | - | 7.3 ± 0.2 |

| pHKCl | - | 7.2 ± 0.2 |

| Electrical conductivity, | μS∙cm−1 | 1740 ± 35 |

| Carbon (organic), | g∙kg−1 D.M. | 221.1 ± 6.0 |

| Nitrogen (N) | g∙kg−1 D.M. | 5.30 ± 0.50 |

| Phosphorus (P) | g∙kg−1 D.M. | 1.42 ± 0.35 |

| Potassium (K) | g∙kg−1 D.M. | 4.82 ± 0.24 |

| Calcium (Ca) | g∙kg−1 D.M. | 26.26 ± 1.50 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | g∙kg−1 D.M. | 1.81 ± 0.05 |

| Sodium (Na) | g∙kg−1 D.M. | 0.71 ± 0.05 |

| Aluminum (Al) | mg∙kg−1 D.M. | 3539 ± 607 |

| Iron (Fe) | mg∙kg−1 D.M. | 1458 ± 85 |

| Zinc (Zn) | mg∙kg−1 D.M. | 134 ± 14 |

| Cadmium (Cd) | mg∙kg−1 D.M. | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

| Chrome (Cr) | mg∙kg−1 D.M. | 54.2 ± 8.5 |

| Cobalt (Co) | mg∙kg−1 D.M. | 5.2 ± 1.1 |

| Copper (Cu) | mg∙kg−1 D.M. | 85.2 ± 7.0 |

| Lead (Pb) | mg∙kg−1 D.M. | 115.3 ± 8.7 |

| Manganese (Mn) | mg∙kg−1 D.M. | 58.4 ± 4.0 |

| Nickel (Ni) | mg∙kg−1 D.M. | 29.2 ± 3.0 |

References

- Regulation of the Minister of Environment on Landfill Site Dated 30 April 2013. Journal of Laws of Poland, Dz.U. 2013 poz. 523. 2013. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20130000523 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Waste Act Dated 14th December 2012. Journal of Laws of Poland, Dz.U. 2013 poz. 21. 2012. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20130000021 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Act on Fertilizers and Fertilization Dated 10th July 2007. Journal of Laws of Poland, Dz.U. 2007 nr 147 poz. 1033. 2007. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20071471033 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 Laying Down Rules on the Making Available on the Market of EU Fertilising Products and Amending Regulations (EC) No 1069/2009 and (EC) No 1107/2009 and repealing Regula. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1009/oj (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Liu, M.; Lv, J.; Qin, C.; Zhang, H.; Wu, L.; Guo, W.; Guo, C.; Xu, J. Chemical fingerprinting of organic micropollutants in different industrial treated wastewater effluents and their effluent-receiving river. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Qiu, Y.; Muhmood, A.; Zhang, L.; Wang, P.; Ren, L. Appraising co-composting efficiency of biodegradable plastic bags and food wastes: Assessment microplastics morphology, greenhouse gas emissions, and changes in microbial community. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 875, 162356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaverková, M.D.; Adamcová, D.; Winkler, J.; Koda, E.; Petrželová, L.; Maxianová, A. Alternative method of composting on a reclaimed municipal waste landfill in accordance with the circular economy: Benefits and risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 723, 137971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Maurya, V.K.; Bee, Z.; Singh, N.; Khare, S.; Singh, S.; Agarwal, N.; Rai, P.K. Green Solutions for a blue planet: Harnessing bioremediation for sustainable development and circular economies. In Biotechnologies for Wastewater Treatment and Resource Recovery: Current Trends and Future Scope; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 283–296. ISBN 9780443273766. [Google Scholar]

- Pauliuk, S. Critical appraisal of the circular economy standard BS 8001:2017 and a dashboard of quantitative system indicators for its implementation in organizations. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 129, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temmes, A.; Peck, P. Do forest biorefineries fit with working principles of a circular bioeconomy? A case of Finnish and Swedish initiatives. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 110, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parilament. The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and The Committee of The Regions, Closing the Loop-An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy. 2015; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52015DC0614 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Kiskira, K.; Papirio, S.; Pechaud, Y.; Matassa, S.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Esposito, G. Evaluation of Fe(II)-driven autotrophic denitrification in packed-bed reactors at different nitrate loading rates. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 142, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.A.; Bashir, O.; Ul Haq, S.A.; Amin, T.; Rafiq, A.; Ali, M.; Américo-Pinheiro, J.H.P.; Sher, F. Phytoremediation of heavy metals in soil and water: An eco-friendly, sustainable and multidisciplinary approach. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 134788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polińska, W.; Kotowska, U.; Kiejza, D.; Karpińska, J. Insights into the use of phytoremediation processes for the removal of organic micropollutants from water and wastewater; A review. Water 2021, 13, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataki, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Vairale, M.G.; Dwivedi, S.K.; Gupta, D.K. Constructed wetland, an eco-technology for wastewater treatment: A review on types of wastewater treated and components of the technology (macrophyte, biolfilm and substrate). J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 283, 111986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radziemska, M.; Bęś, A.; Gusiatin, Z.M.; Cerdà, A.; Jeznach, J.; Mazur, Z.; Brtnický, M. Assisted phytostabilization of soil from a former military area with mineral amendments. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 188, 109934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.H.A.; Kiyani, A.; Santiago-Herrera, M.; Ibáñez, J.; Yousaf, S.; Iqbal, M.; Martel-Martín, S.; Barros, R. Sustainability of phytoremediation: Post-harvest stratagems and economic opportunities for the produced metals contaminated biomass. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, H.M.; Hayder, G.; Mustapa, S.I. Circular Economy Framework for Energy Recovery in Phytoremediation of Domestic Wastewater. Energies 2022, 15, 3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justin, M.Z.; Pajk, N.; Zupanc, V.; Zupančič, M. Phytoremediation of landfill leachate and compost wastewater by irrigation of Populus and Salix: Biomass and growth response. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1032–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowczyk, A.; Szymańska-Pulikowska, A. Micro-and Macroelements Content of Plants Used for Landfill Leachate Treatment Based on Phragmites australis and Ceratophyllum demersum. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, A.; Ojha, C.S.P.; Pant, A.; Kumar, R. Interaction among Heavy Metals in Landfill Leachate and Their Effect on the Phytoremediation Process of Indian Marigold. J. Hazard. Toxic Radioact. Waste 2023, 27, 04022039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, J.; Kamala-Kannan, S.; Lee, K.J.; Cho, M.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Bae, J.H.; Kim, K.H.; Myung, H.; Oh, B.T. Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals in Contaminated Water and Soil Using Miscanthus sp. Goedae-Uksae 1. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2015, 17, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pidlisnyuk, V.; Mamirova, A.; Pranaw, K.; Stadnik, V.; Kuráň, P.; Trögl, J.; Shapoval, P. Miscanthus × giganteus Phytoremediation of Soil Contaminated with Trace Elements as Influenced by the Presence of Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria. Agronomy 2022, 12, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrić, S.; Knežević, G.; Maletić, S.; Rončević, S.; Kragulj Isakovski, M.; Zeremski, T.; Beljin, J. An Experimental Assessment of Miscanthus x giganteus for Landfill Leachate Treatment: A Case Study of the Grebača Landfill in Obrenovac. Processes 2025, 13, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, T.; Ghimire, M.; Shrestha, S.M. Impact evaluation with potential ecological risk of dumping sites on soil in Baglung Municipality, Nepal. Environ. Challenges 2022, 8, 100564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frirsche, U.; Brunori, G.; Chiaramonti, D.; Galanakis, C.; Matthews, R.; Panoutsou, C.; Avraamides, M.; Borzacchiello, M.; Sanchez Lopez, J. Future Transitions for the Bioeconomy Towards Sustainable Development and a Climate-Neutral Economy-Publications Office of the EU; Avraamides, M., Borzachciello, M., Sanchez Lopez, J., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; ISBN 978-92-76-28413-0. [Google Scholar]

- Grzegórska, A.; Czaplicka, N.; Antonkiewicz, J.; Rybarczyk, P.; Baran, A.; Dobrzyński, K.; Zabrocki, D.; Rogala, A. Remediation of soils on municipal rendering plant territories using Miscanthus × giganteus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 22305–22318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, S.; Le Pera, A.; Sellaro, M.; Lombardo, L.; Bruno, L. Separately Collected Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste Compost as a Sustainable Improver of Soil Characteristics in the Open Field and a Promising Selective Booster for Nursery Production. Agronomy 2025, 15, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabała, C.; Charzyński, P.; Chodorowski, J.; Drewnik, M.; Glina, B.; Greinert, A.; Hulisz, P.; Jaknowski, M.; Jonczak, J.; Łabaz, B.; et al. Polish Soil Classification; Publishing House of Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences: Wrocław, Poland, 2019; ISBN 978-83-7717-321-3. [Google Scholar]

- Soil Improver Certificate SK-9. Available online: https://zut.com.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/decyzja-G-1128_22.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Regulation of the Minister for Agriculture and Rural Development of 18 June 2008 on the Implementation of Certain Provisions of the Act on Fertilisers and Fertilisation, Dz. U. 2008, 119, poz. 765. 2008. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20081190765 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Regulation of the Minister of Agricultural and Rural Development Dated 21 December 2009 Amending Regulation Concerning the Implementation of Certain Provisions of the Act on Fertilizers and Fertilization, Dz. U. 2009, 224, poz. 1804. 2009. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20092241804 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Announcement of the Minister of Infrastructure and Construction of 28 September 2016 on the announcement of the consolidated text of the regulation of the Minister of Construction on the manner of fulfilling the obligations of industrial wastewater, Dz. U. 2016, poz. 1757. 2016. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20160001757 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Pidlisnyuk, V.; Herts, A.; Khomenchuk, V.; Mamirova, A.; Kononchuk, O.; Ust’ak, S. Dynamic of morphological and physiological parameters and variation of soil characteristics during miscanthus × giganteus cultivation in the diesel-contaminated land. Agronomy 2021, 11, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowska, A.; Gawliński, S.; Szczubiałka, Z. Methods of Analysis and Assessment of Soil and Plant Properties; A Catalogue; Institute of Environmental Protection–National Research Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 1991. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- PN-EN 12880:2004; Characterization of Sludges. Determination of Dry and Water Content. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2004.

- PN-ISO-10390-1997; Soil Quality-Determination Of pH. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 1997.

- PN ISO 11261:2002; Soil Quality-Determination of Total Nitrogen-Modified Kjeldahl Method. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2002.

- Jones, J.B.; Case, V.W. Sampling, Handling, and Analyzing Plant Tissue Samples. In Soil Testing and Plant Analysis; Westerman, R.L., Ed.; Soil Science Society of America, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1990; Volume 3, pp. 389–427. [Google Scholar]

- EN 13656:2020; Soil, Treated Biowaste, Sludge and Waste-Digestion with a Hydrochloric (HCl), Nitric (HNO3) and Tetrafluoroboric (HBF4) or Hydrofluoric (HF) Acid Mixture for Subsequent Determination of Elements. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/e747bff6-394f-44c3-806a-e8e1d39b5a83/en-13656-2020?srsltid=AfmBOorS6Uh8TE8XEnmyxIpqd6J6ruoG1xVJF6cCekTUY_0YUhg8KJzv (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- EN 16170:2016; Sludge, Treated Biowaste and Soil-Determination of Elements Using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/c359e442-fd27-4e82-830e-318685e45172/en-16170-2016?srsltid=AfmBOootJPj4vT-nPT9-ZnQbu5XLVygRCnbnuwZhKcvzn9MAeXI6H31X (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Szufa, S.; Piersa, P.; Adrian, Ł.; Sielski, J.; Grzesik, M.; Romanowska-Duda, Z.; Piotrowski, K.; Lewandowska, W. Acquisition of torrefied biomass from Jerusalem artichoke grown in a closed circular system using biogas plant waste. Molecules 2020, 25, 3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowska-Duda, Z.; Szufa, S.; Grzesik, M.; Piotrowski, K.; Janas, R. The promotive effect of cyanobacteria and chlorella sp. Foliar biofertilization on growth and metabolic activities of willow (salix viminalis L.) plants as feedstock production, solid biofuel and biochar as C carrier for fertilizers via torrefaction process. Energies 2021, 14, 5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowska-Duda, Z.; Piotrowski, K.; Szufa, S.; Sklodowska, M.; Naliwajski, M.; Emmanouil, C.; Kungolos, A.; Zorpas, A.A. Valorization of Spirodela polyrrhiza biomass for the production of biofuels for distributed energy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowska-Duda, Z.; Janas, R.; Grzesik, M.; van Duijn, B. Valorization of sorghum ash with digestate and biopreparations in the development biomass of plants in a closed production system of energy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowska-Duda, Z.; Grzesik, M.; Janas, R. Ash from Jerusalem artichoke and biopreparations enhance the growth and physiological activity of sorghum and limit environmental pollution by decreasing artificial fertilization needs. Int. Agrophys. 2020, 34, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsalu, T.; Vilo, J. ClustVis: A web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W566–W570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, A.; Taiz, L. A New Vertical Mesh Transfer Technique for Metal-Tolerance Studies in Arabidopsis (Ecotypic Variation and Copper-Sensitive Mutants). Plant Physiol. 1995, 108, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio 2024. Integrated Development Environment for R. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- R 2024: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Antonkiewicz, J.; Gworek, B. Remediation of Contaminated Soils and Lands; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zadroga, B.; Oleńczuk-Neyman, K. Protection and Reclamation of the Subsoil; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Gdańskiej: Gdańsk, Poland, 2001; ISBN 8388007955. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on Waste and Repealing Certain Directives. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02008L0098-20240218 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Krzyżak, J.; Rusinowski, S.; Sitko, K.; Szada-Borzyszkowska, A.; Stec, R.; Jensen, E.; Clifton-Brown, J.; Kiesel, A.; Lewin, E.; Janota, P.; et al. The Effect of Different Agrotechnical Treatments on the Establishment of Miscanthus Hybrids in Soil Contaminated with Trace Metals. Plants 2023, 12, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zhao, R.; Li, Q.; Ma, Y.; Chen, J.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, D.; An, S. Elemental composition and microbial community differences between wastewater treatment plant effluent and local natural surface water: A Zhengzhou city study. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audet, P.; Charest, C. Heavy metal phytoremediation from a meta-analytical perspective. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 147, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrella-González, M.J.; López-González, J.A.; Suárez-Estrella, F.; López, M.J.; Jurado, M.M.; Siles-Castellano, A.B.; Moreno, J. Evaluating the influence of raw materials on the behavior of nitrogen fractions in composting processes on an industrial scale. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 303, 122945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubis, B.; Jankowski, K.J.; Załuski, D.; Sokólski, M. The effect of sewage sludge fertilization on the biomass yield of giant miscanthus and the energy balance of the production process. Energy 2020, 206, 118189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Gehren, P.; Gansberger, M.; Pichler, W.; Weigl, M.; Feldmeier, S.; Wopienka, E.; Bochmann, G. A practical field trial to assess the potential of Sida hermaphrodita as a versatile, perennial bioenergy crop for Central Europe. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 122, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Santanen, A.; Jaakkola, S.; Ekholm, P.; Hartikainen, H.; Stoddard, F.L.; Mäkelä, P.S.A. Biomass yield and quality of bioenergy crops grown with synthetic and organic fertilizers. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 59, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.J.; Granollers Mesa, M.; Osatiashtiani, A.; Taylor, M.J.; Manayil, J.C.; Parlett, C.M.A.; Isaacs, M.A.; Kyriakou, G. The effect of metal precursor on copper phase dispersion and nanoparticle formation for the catalytic transformations of furfural. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 273, 119062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, J.; Jaafar, A.A.K.; Habib, H.; Bouguerra, S.; Nogueira, V.; Rodríguez-Seijo, A. The impact of olive mill wastewater on soil properties, nutrient and heavy metal availability–A study case from Syrian vertisols. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zayed, A.; Gowthaman, S.; Terry, N. Phytoaccumulation of Trace Elements by Wetland Plants: I. Duckweed. J. Environ. Qual. 1998, 27, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popek, R.; Mahawar, L.; Shekhawat, G.S.; Przybysz, A. Phyto-cleaning of particulate matter from polluted air by woody plant species in the near-desert city of Jodhpur (India) and the role of heme oxygenase in their response to PM stress conditions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 70228–70241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziej, B.; Antonkiewicz, J.; Bielińska, E.J.; Witkowicz, R.; Dubis, B. Recovery of microelements from municipal sewage sludge by reed canary grass and giant miscanthus. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2023, 25, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, H.; Cao, Y.; Weeda, S.; Ren, S.; Guo, Y.D. Roles of melatonin in abiotic stress resistance in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchie, E.H.; Lawson, T. Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis: A guide to good practice and understanding some new applications. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3983–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, W.Y.; Tsai, T.T.; Chen, W.H. The responses of photosynthetic gas exchange and chlorophyll a fluorescence to changes of irradiance and temperature in two species of Miscanthus. Photosynthetica 1997, 34, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaškin, J.; Tomaškinová, J.; Theuma, H. Chlorophyll fluorescence as a criterion for the diagnosis of abiotic environmental stress of miscanthus x giganteus hybrid. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30, 3269–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głowacka, K.; Jezowski, S.; Kaczmarek, Z. Gas exchange and yield in Miscanthus species for three years at two locations in Poland. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 93, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Object No. | Substrate * | Dose of Water/Wastewater, mL∙pot−1∙Week−1 | pHH2O (Substrate) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Control: Sa | 500 H2O | 7.8 ± 0.2 |

| 2 | Sa: SK-9 (1/1 v/v) | 500 H2O | 7.5 ± 0.2 |

| 3 | Sa: SK-9 (1/1 v/v) | 1 May—15: 500 H2O 16 May—30 September: 50 W + 450 H2O | 8.2 ± 0.2 |

| 4 | Sa: SK-9 (1/1 v/v) | 1 May—15: 500 H2O 16 May—30 September: 100 W + 400 H2O | 7.7 ± 0.2 |

| 5 | Sa: SK-9 (1/1 v/v) | 1 May—15: 500 H2O 16 May—30 September: 200 W + 300 H2O | 7.7 ± 0.2 |

| Object No. | Dose of Industrial Sewage, mL∙pot−1 | Biomass Yield g∙pot−1 D.M. | Tolerance Index | Heat of Combustion MJ∙kg−1 D.M. * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 249 ± 7 ** | - | 14.5 ± 0.4 |

| 2 | 0 | 276 ± 11 | 1.1 | 15.4 ± 0.2 S |

| 3 | 50 | 358 ± 11 S | 1.4 | 15.6 ± 0.2 S |

| 4 | 100 | 419 ± 12 S | 1.7 | 16.3 ± 0.2 S |

| 5 | 200 | 594 ± 13 S | 2.4 | 17.0 ± 0.3 S |

| CV % *** | 36 | 32.7 | 1.0 | |

| LSD α ≤ 0.01 **** | 29 | - | 0.2 | |

| Object No. * | Dose of Industrial Sewage, mL∙pot−1 | Al | Fe | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | Plant | BCF | Substrate | Plant | BCF | ||

| 1 | 0 | 2268 ± 37 | 24 ± 1 | 0.01 | 2835 ± 212 | 399 ± 22 | 0.14 |

| 2 | 0 | 2936 ± 106 S | 32 ± 5 | 0.01 | 3879 ± 211 S | 478 ± 31 S | 0.12 |

| 3 | 50 | 3062 ± 102 S | 44 ± 4 | 0.01 | 4078 ± 216 S | 529 ± 31 S | 0.13 |

| 4 | 100 | 3087 ± 46 S | 72 ± 10 S | 0.02 | 4734 ± 213 S | 551 ± 31 S | 0.12 |

| 5 | 200 | 3134 ± 94 S | 86 ± 10 S | 0.03 | 5118 ± 278 S | 725 ± 33 S | 0.14 |

| LSD α ≤ 0.01 | 213 | 18 | - | 589 | 78 | - | |

| Mn | Co | ||||||

| 1 | 0 | 81.0 ± 0.8 | 22.9 ± 0.0 | 0.28 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.88 |

| 2 | 0 | 88.8 ± 0.9 S | 27.8 ± 0.2 S | 0.31 | 2.18 ± 0.11 S | 0.18 ± 0.01 S | 0.08 |

| 3 | 50 | 89.2 ± 0.5 S | 29.1 ± 0.3 S | 0.33 | 2.21 ± 0.07 S | 0.18 ± 0.01 S | 0.08 |

| 4 | 100 | 91.1 ± 1.4 S | 32.8 ± 0.1 S | 0.36 | 2.21 ± 0.04 S | 0.18 ± 0.02 S | 0.08 |

| 5 | 200 | 103.1 ± 0.8 S | 35.5 ± 0.1 S | 0.34 | 2.22 ± 0.03 S | 0.19 ± 0.02 S | 0.08 |

| LSD α ≤ 0.01 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 0.16 | 0.03 | |||

| Ni | Zn | ||||||

| 1 | 0 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 0.60 | 78 ± 1 | 27.0 ± 0.3 | 0.34 |

| 2 | 0 | 12.0 ± 0.5 S | 4.8 ± 0.3 S | 0.40 | 111 ± 5 S | 30.7 ± 0.2 S | 0.28 |

| 3 | 50 | 12.2 ± 0.1 S | 5.2 ± 0.2 S | 0.43 | 116 ± 3 S | 32.6 ± 0.5 S | 0.28 |

| 4 | 100 | 13.0 ± 0.5 S | 6.1 ± 0.4 S | 0.47 | 120 ± 6 S | 36.7 ± 0.3 S | 0.31 |

| 5 | 200 | 13.4 ± 0.4 S | 6.5 ± 0.3 S | 0.49 | 121 ± 3 S | 41.3 ± 0.4 S | 0.34 |

| LSD α ≤ 0.01 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 10 | 1 | |||

| Cd | Pb | ||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0.01 ± 0.000 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.67 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.06 |

| 2 | 0 | 0.75 ± 0.09 S | 0.06 ± 0.02 S | 0.08 | 32.9 ± 2.5 S | 1.4 ± 0.0 S | 0.04 |

| 3 | 50 | 0.75 ± 0.03 S | 0.07 ± 0.01 S | 0.09 | 33.2 ± 0.6 S | 1.4 ± 0.0 S | 0.04 |

| 4 | 100 | 0.77 ± 0.01 S | 0.07 ± 0.01 S | 0.10 | 33.4 ± 0.1 S | 1.4 ± 0.1 S | 0.04 |

| 5 | 200 | 0.79 ± 0.02 S | 0.08 ± 0.01 S | 0.10 | 33.7 ± 0.5 S | 1.5 ± 0.1 S | 0.04 |

| LSD α ≤ 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 3.0 | 0.1 | |||

| Cr | Cu | ||||||

| 1 | 0 | 7.0 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.23 | 9.6 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 0.26 |

| 2 | 0 | 21.7 ± 0.1 S | 3.6 ± 0.2 S | 0.16 | 30.4 ± 0.9 S | 6.6 ± 0.5 S | 0.22 |

| 3 | 50 | 21.9 ± 0.1 S | 3.7 ± 0.1 S | 0.17 | 30.7 ± 0.6 S | 6.9 ± 0.2 S | 0.23 |

| 4 | 100 | 22.1 ± 0.8 S | 4.2 ± 0.9 S | 0.19 | 30.9 ± 0.5 S | 7.6 ± 0.2 S | 0.25 |

| 5 | 200 | 22.5 ± 0.9 S | 4.3 ± 0.7 S | 0.19 | 31.0 ± 0.3 S | 7.8 ± 0.3 S | 0.25 |

| LSD α ≤ 0.01 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.9 | |||

| Object No.* | Dose of Industrial Sewage, mL∙pot−1 | Al | Fe | Mn | Co | Ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 99.3 ± 8.1 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 0.017 ± 0.002 | 0.58 ± 0.08 |

| 2 | 0 | 7.1 ± 0.9 | 105.2 ± 7.6 | 6.1 ± 0.2 | 0.040 ± 0.003 S | 1.06 ± 0.09 S |

| 3 | 50 | 15.6 ± 0.8 S | 189.7 ± 16.3 S | 10.4 ± 0.4 S | 0.064 ± 0.003 S | 1.87 ± 0.06 S |

| 4 | 100 | 30.2 ± 3.5 S | 231.4 ± 19.7 S | 13.7 ± 0.5 S | 0.074 ± 0.008 S | 2.55 ± 0.25 S |

| 5 | 200 | 51.2 ± 5.2 S | 431.0 ± 29.4 S | 21.1 ± 0.5 S | 0.111 ± 0.007 S | 3.88 ± 0.12 S |

| LSD α ≤ 0.01 | 7.3 | 46.8 | 1.0 | 0.013 | 0.36 | |

| Zn | Cd | Pb | Cr | Cu | ||

| 1 | 0 | 6.7 ± 0.3 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 0.63 ± 0.10 |

| 2 | 0 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 0.014 ± 0.003 S | 0.30 ± 0.01 S | 0.78 ± 0.08 | 1.46 ± 0.07 S |

| 3 | 50 | 11.7 ± 0.3 S | 0.025 ± 0.004 S | 0.49 ± 0.01 S | 1.34 ± 0.03 S | 2.49 ± 0.02 S |

| 4 | 100 | 15.4 ± 0.4 S | 0.031 ± 0.002 S | 0.58 ± 0.04 S | 1.75 ± 0.41 S | 3.18 ± 0.10 S |

| 5 | 200 | 24.5 ± 0.8 S | 0.048 ± 0.007 S | 0.88 ± 0.07 S | 2.53 ± 0.42 S | 4.62 ± 0.07 S |

| LSD α ≤ 0.01 | 1.2 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.69 | 0.20 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rybarczyk, P.; Antonkiewicz, J.; Romanowska-Duda, Z.; Mec, S.; Rogala, A. Circular Perspective for Utilization of Industrial Wastewaters via Phytoremediation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310865

Rybarczyk P, Antonkiewicz J, Romanowska-Duda Z, Mec S, Rogala A. Circular Perspective for Utilization of Industrial Wastewaters via Phytoremediation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310865

Chicago/Turabian StyleRybarczyk, Piotr, Jacek Antonkiewicz, Zdzisława Romanowska-Duda, Stanisław Mec, and Andrzej Rogala. 2025. "Circular Perspective for Utilization of Industrial Wastewaters via Phytoremediation" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310865

APA StyleRybarczyk, P., Antonkiewicz, J., Romanowska-Duda, Z., Mec, S., & Rogala, A. (2025). Circular Perspective for Utilization of Industrial Wastewaters via Phytoremediation. Sustainability, 17(23), 10865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310865