Promoting Sustainable Life Through Global Citizenship-Oriented Educational Approaches: Comparison of Learn–Think–Act Approach-Based and Lecture-Based SDG Instructions on the Development of Students’ Sustainability Consciousness

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ 1: Does learn–think–act approach-based instruction on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) lead to a statistically significant change in middle school students’ sustainability consciousness?

- RQ 2: Does lecture-based instruction on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) lead to a statistically significant change in middle school students’ sustainability consciousness?

- RQ 3: Which instructional method better enhances students’ sustainability consciousness, learn–think–act approach-based instruction or lecture-based SDG instruction?

2. Research Framework

2.1. Education for Sustainable Life

2.2. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Instruction in Middle Schools

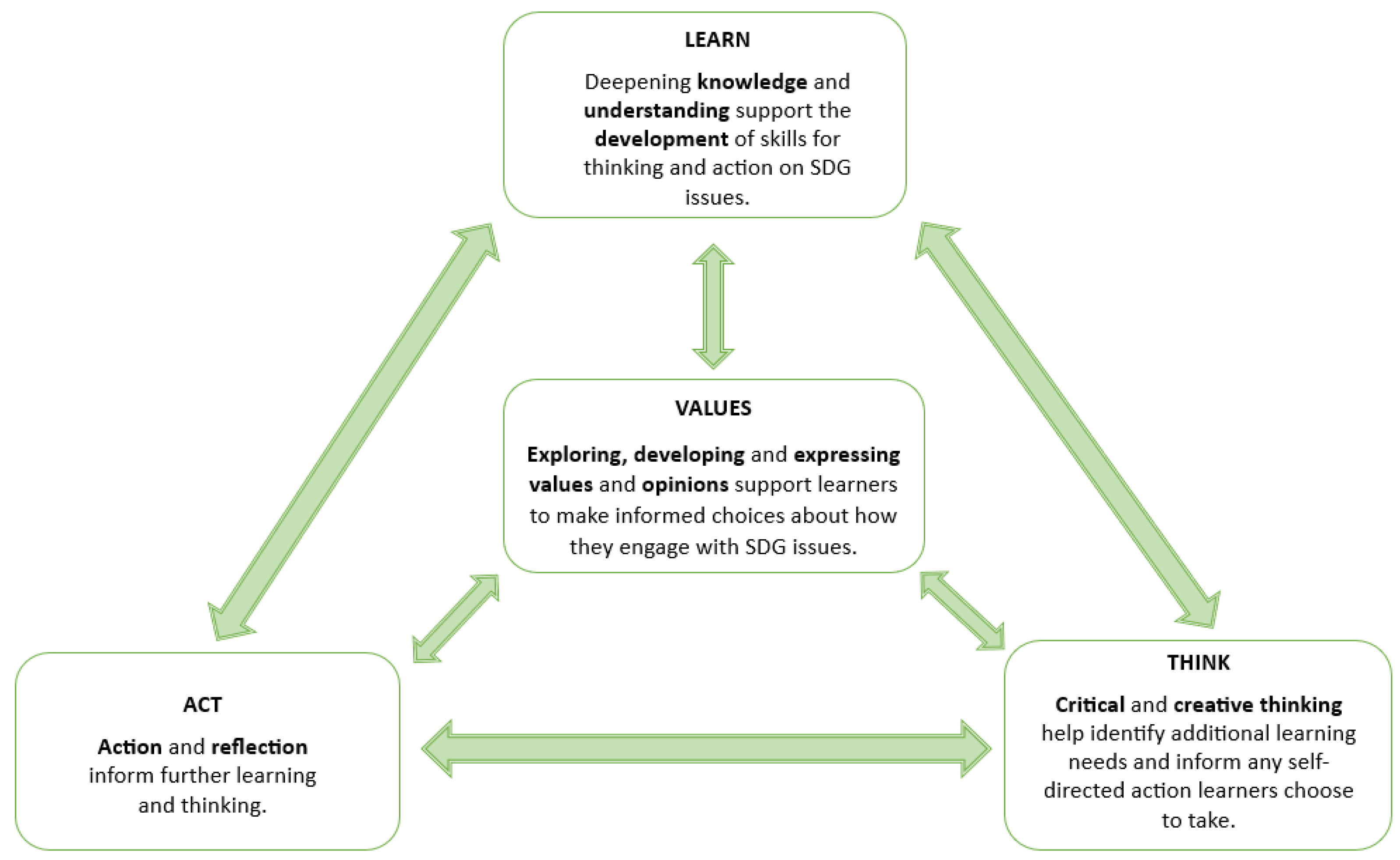

2.2.1. Learn–Think–Act Approach-Based SDG Instruction

2.2.2. Lecture-Based SDG Instruction

2.3. Sustainability Consciousness

3. Method

3.1. Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Implementation

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Data Analysis

3.6. Ethical Issues

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Effect of Learn–Think–Act-Approach-Based SDG Instruction on Students’ Sustainability Consciousness

4.2. Results of the Effect of Lecture-Based SDG Instruction on Students’ Sustainability Consciousness

4.3. Results of Comparison of the Effects of Learn–Think–Act-Approach-Based and Lecture-Based SDG Instructions on Students’ Sustainability Consciousness

4.3.1. Results About Knowingness Factor of Sustainability Consciousness

4.3.2. Results About Attitude Factor of Sustainability Consciousness

4.3.3. Results About Behavior Factor of Sustainability Consciousness

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| ESDG | Education for Sustainable Development Goals |

| SC | Sustainability Consciousness |

| SCQ | Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire |

| CI | Confidence Intervals |

| Env | Environmental |

| Eco | Economic |

| Soc | Social |

| K | Knowingness |

| A | Attitudes |

| B | Behavior |

| KAB | Knowingness Attitudes Behavior |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

Appendix A. Some Items of the Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire (SCQ)

| Factors of SCQ | Sub-Factors of SCQ | Items |

| Knowingness | Economic | 1. Economic development is necessary for sustainable development. |

| Social | 9. Respecting human rights is necessary for sustainable development. | |

| Environmental | 12. Preserving many different natural species is necessary for sustainable development. | |

| Attitude | Economic | 26. I think that companies in rich countries should give employees in poor nations the same conditions as in rich countries. |

| Social | 32.I think that women and men throughout the world must be given the same opportunities for education and employment. | |

| Environmental | 33. I think it is okay that each one of us uses as much water as we want. | |

| Behavior | Economic | 42. I often purchase second-hand goods over the internet or in a shop. |

| Social | 38. I often do things which are not good for my health. | |

| Environmental | 43. I always separate food waste before putting out the rubbish when I have the chance. |

References

- Kahn, R. From education for sustainable development to ecopedagogy: Sustaining capitalism or sustaining life? Green Theory Prax. J. Ecoped. 2008, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, C. The Psychology of Sustainable Behavior: Tips for Empowering People to Take Environmentally Positive Action; Minnesota Pollution Control Agency: Duluth, MN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). Sustainable Development Goals: 17 Goals to Transform Our World. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/exhibits/page/sdgs-17-goals-transform-world (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Uleanya, C.; Ilesanmi, K.D.; Yassim, K.; Omotosho, A.O.; Kimanzi, M. Sustainability consciousness of selected university students in South Africa. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacci, S.; Bertaccini, B.; Macrì, E.; Pettini, A. Measuring sustainability consciousness in Italy. Qual. Quant. 2024, 58, 4751–4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, H.; Ali, M.; Sopandi, W.; Wulan, A.R. The ESD-oriented RADEC model: To improve students sustainability consciousness in elementary schools. Pegem J. Educ. Instruc. 2022, 12, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Merino, J.M.; Corbacho-Cuello, I.; Hernández-Barco, M. Analysis of Sustainability Knowingness, Attitudes and Behavior of a Spanish Pre-Service Primary Teachers Sample. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odell, V.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Martin, S.; Sterling, S. Transformative education to address all sustainable development goals. In Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 905–916. ISBN 9783319699028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Sustainable Development Begins with Education, How Education Can Contribute to the Proposed Post-2015 Goals. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/2275sdbeginswitheducation.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Chen, C.; An, Q.; Zheng, L.; Guan, C. Sustainability Literacy: Assessment of Knowingness, Attitude and Behavior Regarding Sustainable Development among Students in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, L. Global Citizenship: Abstraction or framework for action. Educ. Rev. 2006, 58, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, T.; Gericke, N.; Pauw, J.B.D.; Olsson, D.; Chang, T.C. A Cross-Cultural Comparative Study of Sustainability Consciousness between Students in Taiwan and Sweden. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 6287–6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, B.P.Y. The United Nations decade of education for sustainable development (2005–2014): Learning to live together sustainably. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2005, 4, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, R.; Chaudhry, I.S.; Ali, S.; Faheem, M. Role of Quality Education for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS). People Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poto, M.P.; Murray, E. Achieving a Common Future for all Through Sustainability-Conscious Legal Education and Research Methods. Glob. Jurist 2024, 24, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, Y.; Eksili, N.; Koksal, K.; Celik, C.P.; Mir, M.S.; Soomro, A.B. Who Is Buying Green Products? The Roles of Sustainability Consciousness, Environmental Attitude, and Ecotourism Experience in Green Purchasing Intention at Tourism Destinations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, X.; Managi, S. The international role of education in sustainable lifestyles and economic development. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadotti, M. Education for sustainability: A critical contribution to the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. Green Theory Prax. J. Ecoped. 2008, 4, 15–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Albareda-Tiana, S.; Vidal-Raméntol, S.; Fernández-Morilla, M. Implementing the sustainable development goals at University level. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nuaimi, S.R.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice towards Sustainability Aspects among Higher Education Students in Qatar. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelar, A.B.A.; Da Silva-Oliveira, K.D.; Pereira, R.D.S. Education for advancing the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals: A systematic approach. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2019, 17, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraslan, M.; Kır, S.; Turan, M.B.; Iqbal, M. Sustainability Consciousness and Environmental Behaviors: Examining Demographic Differences Among Sports Science Students. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousheen, A.; Tabassum, F. Assessing Students’ Sustainability Consciousness in Relation to Their Perceived Teaching Styles: An Exploratory Study in Pakistani Context. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 1214–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Estévez, M.; Chalmeta, R. Integrating Sustainable Development Goals in educational institutions. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N. The adolescent dip in students’ sustainability consciousness. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 47, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N. The Effect of Gender on Students Sustainability Consciousness: A Nationwide Swedish Study. J. Environ. Educ. 2017, 48, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.J. The Earth’s Blanket: Traditional Teachings for Sustainable Living; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, J.; da Silva, S.; Carvalho, A.S.; de Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O. Education for Sustainable Development and Its Role in the Promotion of the Sustainable Development Goals. In Curricula for Sustainability in Higher Education; Davim, J.P., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-3-319-56505-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen, F.; Schnack, K. The Action Competence Approach and the ‘New’ Discourses of Education for Sustainable Development, Competence and Quality Criteria. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (DESD), 2005–2014: Review of Contexts and Structures for Education for Sustainable Development Learning for a Sustainable World; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. ESD—Building a Better, Fairer World for the 21st Century; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013; Available online: http://u4614432.fsdata.se/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/esd.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Barth, M.; Godemann, J.; Rieckmann, M.; Stoltenberg, U. Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biberhofer, P.; Rammel, C. Transdisciplinary learning and teaching as answers to urban sustainability challenges. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, B.A.; Miller, K.K.; Cooke, R.; White, J.G. Environmental sustainability in higher education: How do academics teach? Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottafava, D.; Cavaglià, G.; Corazza, L. Education of sustainable development goals through students’ active engagement: A transformative learning experience. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2019, 10, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlouhá, J.; Macháčková-Henderson, L.; Dlouhý, J. Learning networks with involvement of higher education institutions. J. Clean. Produc. 2013, 49, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Khare, A.; Sharma, R. Values, Sustainability Consciousness and Intentions for SDG Endorsement. Market. Intell. Plan. 2020, 38, 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. Education for sustainability: Fostering a more conscious society and transformation towards sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Polo, F.; Sánchez-Martín, J. Teaching for a Better World. Sustainability and Sustainable Development Goals in the Construction of a Change-Maker University. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, J.; Liddy, M. The Impact of Development Education and Education for Sustainable Development Interventions: A Synthesis of the Research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 1031–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscitelli, A.; D’Uggento, A.M. Do young people really engage in sustainable behaviors in their lifestyles? Soc. Indicat. Res. 2022, 163, 1467–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J. Learning Our Way to Sustainability. J. Educ. Sustain Dev. 2011, 5, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, C. Valuing interdependence of education, trade and the environment for the achievement of sustainable development. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 3340–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hopkins, C. Twenty Years of Education for Sustainable Development. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsager, M.; Scheie, E. Students and education for sustainable development—What matters? A case study on students’ sustainability consciousness derived from participating in an ESD project. Acta Didact. 2019, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppi, E. Training to education for sustainable development through e-learning. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 15, 3244–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McIntosh, M. Creating Global Citizens and Responsible Leadership: A Special Theme Issue of The Journal of Corporate Citizenship; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Saleem, A.; Dare, P.S. Unmasking the Action-Oriented ESD Approach to Acting Environmentally Friendly. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.R. The environmental education as a path for a global sustainability. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 106, 2769–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wals, A.E. Review of Contexts and Structures for Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- OXFAM. The Sustainable Development Goals: A Guide for Teachers; Oxfam GB: Oxford, UK, 2019; Available online: https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620842/edu-sustainable-development-guide-15072019-en.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y (accessed on 25 June 2025).[Green Version]

- Koçulu, A. Developing Secondary School Students’ Sustainable Living Awareness to Help Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putman, M.; Byker, E.J. Global Citizenship 1-2-3: Learn, Think, and Act. Kappa Delta Pi Rec. 2020, 56, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.A.; Smolen, L.A.; Oswald, R.A.; Milam, J.L. Preparing students for global citizenship in the twenty-first century: Integrating social justice through global literature. Soc. Stud. 2012, 103, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Peng, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.H. Interactive whiteboard-based instruction versus lecture-based instruction: A study on college students’ academic self-efficacy and academic press. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Blended Learning, Hong Kong, China, 23–27 March 2020; Cheung, S.K.S., Kwok, L.F., Ma, W.W.K., Lee, L.K., Yang, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Peng, C.; Yang, H.H.; Macleod, J. Examining IWB-based instruction on the academic self-efficacy, academic press and achievement of college students. Open Learn. 2018, 30, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarghouie, M.H.G.; Omid, A.; Ghadami, A. Effects of virtual and lecture-based instruction on learning, content retention, and satisfaction from these instruction methods among surgical technology students: A comparative study. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyne, J.; Moratis, L.; Vos, A. The Three Enablers of Sustainability Intelligence. J. Int. Educ. Bus. 2022, 15, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, Y.; Eksili, N.; Celik Caylak, P.; Mir, M.S. Sustainability Consciousness Research Trends: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovais, D. Students’ Sustainability Consciousness with the Three Dimensions of Sustainability: Does the Locus of Control Play a Role? Reg. Sustain. 2023, 4, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Morales, S.; Ferriz-Valero, A.; Campillo-Sánchez, J.; González-Víllora, S. Sustainability Awareness of In-Service Physical Education Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, T.; Gericke, N.; Rundgren, S.N.C. The Implementation of Education for Sustainable Development in Sweden: Investigating the Sustainability Consciousness among Upper Secondary Students. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2014, 32, 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsoom, Q.; Khanam, A.; Quraishi, U. Sustainability Consciousness of Pre-Service Teachers in Pakistan. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 1090–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legault, L.; Pelletier, L.G. Impact of an environmental education program on students’ and parents’ attitudes, motivation, and behaviours. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2000, 32, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogishima, H.; Ito, A.; Kajimura, S.; Toshiyukiİ, H. Validity and Reliability of the Japanese Version of the Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1130550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D. Student Sustainability Consciousness: Investigating Effects of Education for Sustainable Development in Sweden and Beyond. Ph.D. Thesis, Karlstad University, Karlstad, Sweden, December 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N.; Rundgren, S.N.C. The effect of implementation of education for sustainable development in Swedish compulsory schools—Assessing pupils’ sustainability consciousness. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 176–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N.; Pauw, J.B.; Berglund, T.; Chang, T. Green Schools in Taiwan—Effects on Student Sustainability Consciousness. Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 54, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauw, J.B.-d.; Gericke, N.; Olsson, D.; Berglund, T. The Effectiveness of Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15693–15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, Z.A.; Zhang, Q.; Ou, J.; Saqib, K.A.; Majeed, S.; Razzaq, A. Education for Sustainable Development in Pakistani Higher Education Institutions: An Exploratory Study of Students’ and Teachers’ Perceptions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1249–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Sustainability consciousness of pre-service English teachers. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbedahin, A.V. Sustainable Development, Education for Sustainable Development, and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Emergence, Efficacy, Eminence, and Future. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farliana, N.; Hardianto, H.; Rusdarti, R.; Sakitri, W. Sustainability consciousness in higher education: Construction of three-dimensional sustainability and role of locus of control. Sustinere J. Environ. Sustain. 2024, 8, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, F. Dissonance in Students’ Perceptions of Sustainable Development and Sustainability: Implications for Curriculum Change. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousheen, A.; Zai, S.A.Y.; Waseem, M.; Khan, S.A. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD): Effects of Sustainability Education on Pre-Service Teachers’ Attitude towards Sustainable Development (SD). J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naqbi, A.K.; Alshannag, Q. The Status of Education for Sustainable Development and Sustainability Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors of UAE University Students. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 566–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arantes, L.; Sousa, B.B. The Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire: Validation Among Portuguese Population. Sustainability 2025, 17, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Aslam, S.; Sang, G.; Dare, P.S.; Zhang, T. Education for Sustainable Development and Sustainability Consciousness: Evidence from Malaysian Universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 24, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçulu, A. Development and Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals Unit: Exploring Students’ Systems Thinking Skills and Ethical Reasoning. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Yıldız Technical University, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Koçulu, A.; Topçu, M.S. Development and Implementation of a Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Unit: Exploration of Middle School Students’ SDG Knowledge. Sustainability 2024, 16, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Raath, S.; Lazzarini, B.; Vargas, V.R.; de Souza, L.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Haddad, R.; Klavins, M.; Orlovic, V. The role of transformation in learning and education for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skouteris, H.; Edwards, S.; Rutherford, L.; Cutter-MacKenzie, A.; Huang, T.; O’Connor, A. Promoting healthy eating, active play and sustainability consciousness in early childhood curricula, addressing the Ben10™ problem: A randomised control trial. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uleanya, C. Sustainability consciousness in primary schools: Roles of leaders in the post/digital era. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 21783–21796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuniarti, Y.S.; Hasan, R.; Ali, M. Competencies of Education for Sustainable Development Related to Mathematics Education in Senior High School. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1179, 012075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüköztürk, Ş. Data Analysis Handbook for Social Sciences: Statistics, Research Design, SPSS Practices and Interpretation, 22nd ed.; Pegem Academy Publishing: Ankara, Türkiye, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 6th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel, J.R.; Wallen, N.E.; Hyun, H.H. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Michalos, A.C.; Creech, H.; Swayze, N.; Kahlke, M.; Buckler, C.; Rempel, K. Measuring knowledge, attitudes and behaviors concerningsustainable development among tenth grade students in Manitoba. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 106, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development 2005–2014; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gericke, N.; Pauw, J.B.; Berglund, T.; Olsson, D. The Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire: The theoretical development and empirical validation of an evaluation instrument for stakeholders working with sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, Y.; Yildiz, B. Adaptation of Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire. Erciyes J. Educ. (EJE) 2019, 3, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ariza, M.R.; Pauw, J.B.; Olsson, D.; Petegem, P.V.; Parra, G.; Gericke, N. Promoting Environmental Citizenship in Education: The Potential of the Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire to Measure Impact of Interventions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, X.; Yu, M.; Wu, D. Application of the Modified College Impact Model to Understand Chinese Engineering Undergraduates’ Sustainability Consciousness. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agu, A.G.; Etuk, S.G.; Madichie, N.O. Exploring the Role of Sustainability-Oriented Marketing Education in Promoting Consciousness for Sustainable Consumption. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.A.; Abdelall, H.A.; Ali, H.I. Enhancing nurses’ sustainability consciousness and its effect on green behavior intention and green advocacy: Quasi-experimental study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firda, R.; Kaniwati, I.; Sriyati, S. STEM Learning in Sustainability Issues to Improve Sustainability Consciousness of Junior High School Students. Paedagog. J. Penelit. Pendidik. 2021, 24, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsoom, Q.; Khanam, A. Inquiry into sustainability issues by preservice teachers: A pedagogy to enhance sustainability consciousness. J. Clean. Produc. 2017, 164, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousheen, A.; Kalsoom, Q. Education for sustainable development amidst COVID-19 pandemic: Role of sustainability pedagogies in developing students’ sustainability consciousness. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 1386–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratis, L.; Melissen, F. The three components of sustainability intelligence. Geoforum 2019, 107, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Week | Learn–Think–Act Approach-Based SDG Instruction | Lecture-Based SDG Instruction |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1 (2 lesson hours) | Data collection: ‘The Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire’ | |

| Learn: SD and 17 SDGs Background+Videos Think: Let’s achieve sustainable development and Sustainable Development Goals! Act: What can you do for the world we want to live in? | Theoretical Information about SD and 17 SDGs | |

| Week 2 (3 lesson hours) | Learn: SDG 1 Background+Videos Think: The world’s resources are not fairly or equally distributed! Act: What can you do to end poverty? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG1 |

| Learn: SDG 2 Background+Videos Think: What’s on our plate? Every plate tells people’s stories. Act: What can you do for zero hunger? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG2 | |

| Learn: SDG 3 Background+Videos Think: A healthy and prosperous life for everyone! Act: What can you do for good health and well-being? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG 3 | |

| Week 3 (3 lesson hours) | Learn: SDG 4 Background+Videos Think: Quality education can change and transform our world! Act: What can you do for quality education? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG4 |

| Learn: SDG 5 Background+Videos Think: Everybody wins if gender equality exists all around the world! Act: What can you do for gender equality? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG5 | |

| Learn: SDG 6 Background+Videos Think: Can you live with dirty water? Clean water for all! Act: What can you do for clean water and sanitation? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG6 | |

| Week 4 (3 lesson hours) | Learn: SDG 7 Background+Videos Think: Let’s use renewable energy! Act: What can you do for affordable and clean energy? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG7 |

| Learn: SDG 8 Background+Videos Think: Decent work and economic growth for a better world! Act: What can you do for decent work and economic growth? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG8 | |

| Learn: SDG 9 Background+Videos Think: The world’s future: industry, innovation, and infrastructure! Act: What can you do for industry, innovation, and infrastructure? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG9 | |

| Week 5 (3 lesson hours) | Learn: SDG 10 Background+Videos Think: We’re not so different each other—let’s stand as one! Act: What can you do for reducing inequalities? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG10 |

| Learn: SDG 11 Background+Videos Think: Build a dream city! Eco-friendly homes and sustainable living for everyone! Act: What can you do for sustainable cities and communities? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG11 | |

| Week 6 (2 lesson hours) | Learn: SDG 12 Background+Videos Think: Reduce, reuse, and recycle for a better life! Understanding the challenge of finite resources. Act: What can you do for responsible consumption and production? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG12 |

| Learn: SDG 13 Background+Videos Think: Climate action: Let’s calculate our carbon footprint! Act: What can you do for climate action? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG13 | |

| Week 7 (2 lesson hours) | Learn: SDG 14 Background+Videos Think: Marine litter— protect life below water! Act: What can you do for life below water? +Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG14 |

| Learn: SDG 15 Background+Videos Think: Earth: It’s everybody’s home! The impact of pollution on our planet and our lives. Act: What can you do to protect life on land? +Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG15 | |

| Week 8 (2 lesson hours) | Learn: SDG 16 Background+Videos Think: The power of peace, justice, and strong institutions. Act: What can you do for peace, justice, and strong institutions? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG16 |

| Learn: SDG 17 Background+Videos Think: Heroes for change: Global citizens—working together to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Act: What can you do in terms of partnerships for the goals? + Videos | Theoretical Information about SDG17 | |

| Data collection: ‘The Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire’ | ||

| SDG | Learn | Think | Act |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 13—Climate Action | Cognitive learning objective Students explain the concept of climate change | Socio-emotional learning objective Students argue their own role and responsibilities related to climate change | Behavioral learning objective Students propose solutions for climate change |

| Background Videos: Understand SDG 13: Climate Action https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6YqmEYlg4IY (accessed on 15 April 2025). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jhoa3OHivN8 (accessed on 15 April 2025). | Classroom activity: Climate action: Let’s calculate our carbon footprint! | Classroom activity: What can you do for climate action? Videos: Take Action on SDG 13: Climate Action https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b61FPARMsv8 (accessed on 15 April 2025). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ugWV-mx5h6o (accessed on 15 April 2025). |

| Factors of SCQ | Sub-Factors of SCQ | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Knowingness | Economic | 1, 11, 14, 15, 17 |

| Social | 2, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13, 18 | |

| Environmental | 3, 4, 6, 12, 16, 19 | |

| Attitude | Economic | 22, 25, 26, 31 |

| Social | 20, 21, 28, 29, 30, 32 | |

| Environmental | 23, 24, 27, 33 | |

| Behavior | Economic | 39, 42, 44, 49 |

| Social | 37, 38, 46, 47, 48, 50 | |

| Environmental | 34, 35, 36, 40, 41, 43, 45 |

| SCQ | Values by the Developer | Values for This Study |

|---|---|---|

| EnvEcoSoc KAB | 0.88 | 0.95 |

| Env KAB | 0.74 | 0.86 |

| Eco KAB | 0.67 | 0.81 |

| Soc KAB | 0.79 | 0.91 |

| K | 0.83 | 0.90 |

| A | 0.74 | 0.89 |

| B | 0.80 | 0.84 |

| Factors of SCQ | Subfactors of SCQ | Mean | N | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowingness | Economic | Pre-test | 19.28 | 40 | 4.31 |

| Post-test | 22.03 | 40 | 2.19 | ||

| Social | Pre-test | 30.83 | 40 | 7.02 | |

| Post-test | 35.05 | 40 | 3.74 | ||

| Environmental | Pre-test | 23.35 | 40 | 5.16 | |

| Post-test | 26.73 | 40 | 2.44 | ||

| Attitude | Economic | Pre-test | 16.75 | 40 | 3.40 |

| Post-test | 19.08 | 40 | 1.10 | ||

| Social | Pre-test | 22.83 | 40 | 5.45 | |

| Post-test | 27.20 | 40 | 2.56 | ||

| Environmental | Pre-test | 15.00 | 40 | 3.66 | |

| Post-test | 17.85 | 40 | 2.06 | ||

| Behavior | Economic | Pre-test | 12.53 | 40 | 2.59 |

| Post-test | 17.35 | 40 | 2.29 | ||

| Social | Pre-test | 21.43 | 40 | 5.28 | |

| Post-test | 25.68 | 40 | 3.13 | ||

| Environmental | Pre-test | 25.80 | 40 | 5.71 | |

| Post-test | 30.28 | 40 | 3.71 | ||

| Total | Pre-test | 187.78 | 40 | 35.50 | |

| Post-test | 218.68 | 40 | 16.57 |

| 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors of SCQ | Subfactors of SCQ | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | Lower | Upper | t | df | p | |

| Knowingness | Economic | Pre-test–Post-test | −2.75 | 4.22 | 0.67 | −4.10 | −1.40 | −4.125 | 39 | 0.000 |

| Social | Pre-test–Post-test | −4.23 | 6.93 | 1.10 | −6.44 | −2.01 | −3.86 | 39 | 0.000 | |

| Environmental | Pre-test–Post-test | −3.38 | 5.17 | 0.82 | −5.08 | −1.72 | −4.13 | 39 | 0.000 | |

| Attitude | Economic | Pre-test–Post-test | −2.33 | 3.71 | 0.59 | −3.51 | −1.14 | −3.96 | 39 | 0.000 |

| Social | Pre-test–Post-test | −4.38 | 5.22 | 0.83 | −6.04 | −2.71 | −5.30 | 39 | 0.000 | |

| Environmental | Pre-test–Post-test | −2.85 | 3.91 | 0.62 | −4.10 | −1.60 | −4.61 | 39 | 0.000 | |

| Behavior | Economic | Pre-test–Post-test | −4.83 | 3.40 | 0.54 | −5.91 | −3.74 | −8.97 | 39 | 0.000 |

| Social | Pre-test–Post-test | −4.25 | 5.35 | 0.85 | −5.96 | −2.54 | −5.03 | 39 | 0.000 | |

| Environmental | Pre-test–Post-test | −4.48 | 5.40 | 0.85 | −6.20 | −2.75 | −5.24 | 39 | 0.000 | |

| Total | Pre-test–Post-test | −30.90 | 33.55 | 5.30 | −41.63 | −20.17 | −5.83 | 39 | 0.000 | |

| Factors of SCQ | Subfactors of SCQ | Mean | N | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowingness | Economic | Pre-test | 20.33 | 40 | 2.29 |

| Post-test | 20.48 | 40 | 2.11 | ||

| Social | Pre-test | 32.78 | 40 | 4.07 | |

| Post-test | 32.40 | 40 | 2.77 | ||

| Environmental | Pre-test | 24.13 | 40 | 3.60 | |

| Post-test | 24.83 | 40 | 2.33 | ||

| Attitude | Economic | Pre-test | 16.23 | 40 | 2.50 |

| Post-test | 16.45 | 40 | 2.09 | ||

| Social | Pre-test | 23.23 | 40 | 2.84 | |

| Post-test | 23.73 | 40 | 3.19 | ||

| Environmental | Pre-test | 15.28 | 40 | 3.26 | |

| Post-test | 15.50 | 40 | 2.40 | ||

| Behavior | Economic | Pre-test | 11.68 | 40 | 2.30 |

| Post-test | 11.83 | 40 | 1.78 | ||

| Social | Pre-test | 21.45 | 40 | 4.52 | |

| Post-test | 21.85 | 40 | 4.07 | ||

| Environmental | Pre-test | 24.98 | 40 | 4.50 | |

| Post-test | 25.55 | 40 | 4.13 | ||

| Total | Pre-test | 191.68 | 40 | 18.28 | |

| Post-test | 192.05 | 40 | 16.31 |

| 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors of SCQ | Subfactors of SCQ | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | Lower | Upper | t | df | p | |

| Knowingness | Economic | Pre-test–Post-test | −0.15 | 2.71 | 0.43 | −1.02 | 0.72 | −0.35 | 39 | 0.728 |

| Social | Pre-test–Post-test | −0.38 | 5.05 | 0.80 | −1.24 | 1.99 | 0.470 | 39 | 0.641 | |

| Environmental | Pre-test–Post-test | −0.70 | 4.21 | 0.67 | −2.05 | 0.65 | −1.05 | 39 | 0.300 | |

| Attitude | Economic | Pre-test–Post-test | −0.23 | 3.25 | 0.51 | −1.27 | 0.82 | −0.44 | 39 | 0.664 |

| Social | Pre-test–Post-test | −0.50 | 3.43 | 0.54 | −1.60 | 0.60 | −92 | 39 | 0.363 | |

| Environmental | Pre-test–Post-test | −0.23 | 4.45 | 0.70 | −1.65 | 1.20 | −0.32 | 39 | 0.751 | |

| Behavior | Economic | Pre-test–Post-test | −0.15 | 3.16 | 0.50 | −1.16 | 0.86 | −0.30 | 39 | 0.766 |

| Social | Pre-test–Post-test | −0.40 | 5.67 | 0.90 | −2.21 | 1.41 | −0.447 | 39 | 0.658 | |

| Environmental | Pre-test–Post-test | −0.58 | 6.03 | 0.95 | −2.50 | 1.35 | −0.604 | 39 | 0.550 | |

| Total | Pre-test–Post-test | −0.3750 | 23.33 | 3.69 | −7.83 | 7.08 | −0.102 | 39 | 0.920 | |

| SCQ | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Pre-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 187.78 | 35.50 |

| Control Group | 40 | 191.68 | 18.28 | ||

| Post-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 218.68 | 16.57 | |

| Control Group | 40 | 192.05 | 16.31 |

| t-Test for Equality of Means | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCQ | F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | Lower | Upper | ||

| Total | Pre-test | Equal variances assumed | 8.46 | 0.005 | −0.618 | 78 | 0.539 | −3.90 | 6.31 | −16.47 | 8.67 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −0.618 | 58.315 | 0.539 | −3.90 | 6.31 | −16.54 | 8.74 | ||||

| Post-test | Equal variances assumed | 0.146 | 0.703 | 7.243 | 78 | 0.000 | 26.63 | 3.68 | 19.31 | 33.94 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 7.243 | 77.981 | 0.000 | 26.63 | 3.68 | 19.31 | 33.94 | ||||

| SCQ Subfactors | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Pre-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 19.28 | 4.31 |

| Control Group | 40 | 20.33 | 2.29 | ||

| Post-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 22.03 | 2.19 | |

| Control Group | 40 | 20.48 | 2.11 | ||

| Social | Pre-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 30.83 | 7.02 |

| Control Group | 40 | 32.78 | 4.07 | ||

| Post-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 35.05 | 3.74 | |

| Control Group | 40 | 32.40 | 2.77 | ||

| Environmental | Pre-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 23.35 | 5.16 |

| Control Group | 40 | 24.13 | 3.60 | ||

| Post-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 26.73 | 2.44 | |

| Control Group | 40 | 24.83 | 2.33 | ||

| Total Knowingness | Pre-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 73.45 | 14.90 |

| Control Group | 40 | 77.23 | 7.70 | ||

| Post-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 83.80 | 7.30 | |

| Control Group | 40 | 77.70 | 5.31 |

| t-Test for Equality of Means | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCQ Subfactors | F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | Lower | Upper | ||

| Economic | Pre-test | Equal variances assumed | 16.64 | 0.000 | −1.36 | 78 | 0.177 | −1.05 | 0.77 | −2.59 | 0.49 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −1.36 | 59.43 | 0.179 | −1.05 | 0.77 | −2.59 | 0.49 | ||||

| Post-test | Equal variances assumed | 0.079 | 0.779 | 3.22 | 78 | 0.002 | 1.55 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 2.51 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 3.22 | 77.90 | 0.002 | 1.55 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 2.51 | ||||

| Social | Pre-test | Equal variances assumed | 9.36 | 0.003 | −1.520 | 78 | 0.133 | −1.95 | 1.28 | −4.50 | 0.60 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −1.520 | 62.605 | 0.133 | −1.95 | 1.28 | −4.51 | 0.61 | ||||

| Post-test | Equal variances assumed | 6.482 | 0.013 | 3.600 | 78 | 0.001 | 2.65 | 0.74 | 1.18 | 4.12 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 3.600 | 71.90 | 0.001 | 2.65 | 0.74 | 1.18 | 4.12 | ||||

| Environmental | Pre-test | Equal variances assumed | 3.65 | 0.060 | −0.779 | 78 | 0.439 | −0.78 | 0.995 | −2.76 | 1.21 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −0.779 | 69.72 | 0.439 | −0.78 | 0.995 | −2.76 | 1.21 | ||||

| Post-test | Equal variances assumed | 0.515 | 0.475 | 3.562 | 78 | 0.001 | 1.90 | 0.53 | 0.84 | 2.96 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 3.562 | 77.84 | 0.001 | 1.90 | 0.53 | 0.84 | 2.96 | ||||

| Total Knowingness | Pre-test | Equal variances assumed | 11.102 | 0.001 | −1.424 | 78 | 0.159 | −3.78 | 2.65 | −9.05 | 1.50 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −1.424 | 58.431 | 0.160 | −3.78 | 2.65 | −9.08 | 1.53 | ||||

| Post-test | Equal variances assumed | 9.964 | 0.002 | 4.275 | 78 | 0.000 | 6.10 | 1.43 | 3.26 | 8.94 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 4.275 | 71.273 | 0.000 | 6.10 | 1.43 | 3.25 | 8.95 | ||||

| SCQ Subfactors | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Pre-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 16.75 | 3.40 |

| Control Group | 40 | 16.23 | 2.50 | ||

| Post-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 19.08 | 1.10 | |

| Control Group | 40 | 16.45 | 2.09 | ||

| Social | Pre-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 22.83 | 5.45 |

| Control Group | 40 | 23.23 | 2.84 | ||

| Post-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 27.20 | 2.56 | |

| Control Group | 40 | 23.73 | 3.19 | ||

| Environmental | Pre-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 15.00 | 3.66 |

| Control Group | 40 | 15.28 | 3.26 | ||

| Post-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 17.85 | 2.06 | |

| Control Group | 40 | 15.50 | 2.40 | ||

| Total attitude | Pre-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 54.58 | 11.39 |

| Control Group | 40 | 54.73 | 6.09 | ||

| Post-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 64.13 | 4.37 | |

| Control Group | 40 | 55.68 | 6.44 |

| t-Test for Equality of Means | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCQ Subfactors | F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | Lower | Upper | ||

| Economic | Pre-test | Equal variances assumed | 1.91 | 0.171 | 0.787 | 78 | 0.434 | 0.53 | 0.67 | −0.80 | 1.85 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 0.787 | 71.55 | 0.434 | 0.53 | 0.67 | −0.81 | 1.86 | ||||

| Post-test | Equal variances assumed | 16.55 | 0.000 | 7.043 | 78 | 0.000 | 2.63 | 0.37 | 1.88 | 3.37 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 7.043 | 58.96 | 0.000 | 2.63 | 0.37 | 1.88 | 3.37 | ||||

| Social | Pre-test | Equal variances assumed | 11.91 | 0.001 | −0.412 | 78 | 0.682 | −0.40 | 0.97 | −2.33 | 1.53 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −0.412 | 58.76 | 0.682 | −0.40 | 0.97 | −2.34 | 1.54 | ||||

| Post-test | Equal variances assumed | 2.38 | 0.127 | 5.37 | 78 | 0.000 | 3.48 | 0.65 | 2.19 | 4.76 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 5.37 | 74.59 | 0.000 | 3.48 | 0.65 | 2.19 | 4.76 | ||||

| Environmental | Pre-test | Equal variances assumed | 0.528 | 0.470 | −0.355 | 78 | 0.724 | −0.28 | 0.77 | −1.82 | 1.27 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −0.355 | 76.98 | 0.724 | −0.28 | 0.77 | −1.82 | 1.27 | ||||

| Post-test | Equal variances assumed | 0.738 | 0.393 | 4.71 | 78 | 0.000 | 2.35 | 0.50 | 1.36 | 3.34 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 4.71 | 76.25 | 0.000 | 2.35 | 0.50 | 1.36 | 3.34 | ||||

| Total attitude | Pre-test | Equal variances assumed | 9.238 | 0.003 | −0.073 | 78 | 0.942 | −0.1500 | 2.04 | −4.21 | 3.91 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −0.073 | 59.622 | 0.942 | −0.1500 | 2.04 | −4.23 | 3.93 | ||||

| Post-test | Equal variances assumed | 4.697 | 0.033 | 6.87 | 78 | 0.000 | 8.45 | 1.23 | 5.99 | 10.90 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 6.87 | 68.682 | 0.000 | 8.45 | 1.23 | 5.99 | 10.91 | ||||

| SCQ Subfactors | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Pre-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 12.53 | 2.59 |

| Control Group | 40 | 11.68 | 2.29 | ||

| Post-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 17.35 | 2.29 | |

| Control Group | 40 | 11.83 | 1.78 | ||

| Social | Pre-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 21.43 | 5.28 |

| Control Group | 40 | 21.45 | 4.52 | ||

| Post-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 25.68 | 3.13 | |

| Control Group | 40 | 21.85 | 4.07 | ||

| Environmental | Pre-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 25.80 | 5.71 |

| Control Group | 40 | 24.98 | 4.50 | ||

| Post-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 30.28 | 3.71 | |

| Control Group | 40 | 25.55 | 4.13 | ||

| Total behavior | Pre-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 59.75 | 11.90 |

| Control Group | 40 | 58.10 | 8.80 | ||

| Post-test | Experimental Group | 40 | 70.75 | 6.75 | |

| Control Group | 40 | 59.23 | 7.21 |

| t-Test for Equality of Means | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCQ Subfactors | F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | Lower | Upper | ||

| Economic | Pre-test | Equal variances assumed | 0.054 | 0.817 | 1.554 | 78 | 0.124 | 0.85 | 0.55 | −0.24 | 1.94 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 1.554 | 76.85 | 0.124 | 0.85 | 0.55 | −0.24 | 1.94 | ||||

| Post test | Equal variances assumed | 6.80 | 0.011 | 12.03 | 78 | 0.000 | 5.53 | 0.46 | 4.61 | 6.44 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 12.03 | 73.51 | 0.000 | 5.53 | 0.46 | 4.61 | 6.44 | ||||

| Social | Pre-test | Equal variances assumed | 0.964 | 0.329 | −0.023 | 78 | 0.982 | −0.03 | 1.10 | −2.21 | 2.16 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −0.023 | 76.22 | 0.982 | −0.03 | 1.10 | −2.21 | 2.16 | ||||

| Post-test | Equal variances assumed | 2.647 | 0.108 | 4.71 | 78 | 0.000 | 3.83 | 0.81 | 2.21 | 5.44 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 4.71 | 73.23 | 0.000 | 3.83 | 0.81 | 2.21 | 5.44 | ||||

| Environmental | Pre-test | Equal variances assumed | 1.46 | 0.231 | 0.718 | 78 | 0.475 | 0.83 | 1.15 | −1.46 | 3.11 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 0.718 | 73.93 | 0.475 | 0.83 | 1.15 | −1.47 | 3.12 | ||||

| Post-test | Equal variances assumed | 1.201 | 0.277 | 5.38 | 78 | 0.000 | 4.73 | 0.88 | 2.98 | 6.47 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 5.38 | 77.13 | 0.000 | 4.73 | 0.88 | 2.98 | 6.47 | ||||

| Total behavior | Pre-test | Equal variances assumed | 1.561 | 0.215 | 0.705 | 78 | 0.483 | 1.65 | 2.34 | −3.01 | 6.31 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 0.705 | 71.835 | 0.483 | 1.65 | 2.34 | −3.02 | 6.32 | ||||

| Post-test | Equal variances assumed | 0.002 | 0.965 | 7.380 | 78 | 0.000 | 11.53 | 1.56 | 8.42 | 14.63 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 7.380 | 77.677 | 0.000 | 11.53 | 1.56 | 8.42 | 14.63 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koçulu, A. Promoting Sustainable Life Through Global Citizenship-Oriented Educational Approaches: Comparison of Learn–Think–Act Approach-Based and Lecture-Based SDG Instructions on the Development of Students’ Sustainability Consciousness. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9026. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209026

Koçulu A. Promoting Sustainable Life Through Global Citizenship-Oriented Educational Approaches: Comparison of Learn–Think–Act Approach-Based and Lecture-Based SDG Instructions on the Development of Students’ Sustainability Consciousness. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9026. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209026

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoçulu, Aslı. 2025. "Promoting Sustainable Life Through Global Citizenship-Oriented Educational Approaches: Comparison of Learn–Think–Act Approach-Based and Lecture-Based SDG Instructions on the Development of Students’ Sustainability Consciousness" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9026. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209026

APA StyleKoçulu, A. (2025). Promoting Sustainable Life Through Global Citizenship-Oriented Educational Approaches: Comparison of Learn–Think–Act Approach-Based and Lecture-Based SDG Instructions on the Development of Students’ Sustainability Consciousness. Sustainability, 17(20), 9026. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209026